Inspired by the Neita victoriae butterfly, this image pays tribute to Rusinga Island on Lake Victoria, home to this rare and graceful species. To the island’s people, the butterfly is more than a symbol of beauty; it embodies harmony between nature and community. Its patterned wings inspire local art and beadwork, reflecting the quiet resilience of the islanders. Protecting the Neita victoriae means safeguarding both their environment and their heritage, a reminder that the island’s wellbeing and its people are one.

is a self-taught photographer whose journey into the world of visual storytelling began as a simple hobby. Over time, photography evolved into his primary artistic outlet—a powerful substitute for words—allowing him to express the richness of the environments he inhabits

and the diverse individuals he encounters. With a background in painting since childhood, Edwin brings a unique, painterly perspective to his photographic work. His art often blurs the lines between fashion, fine art, and cultural storytelling. By styling his subjects, crafting original sets, and capturing them through his lens, he explores African culture in fresh, visually arresting ways that challenge conventional narratives. Collaborating with other creatives across the industry fuels his passion and pushes his artistic boundaries. For Edwin, every image is more than just a photograph—it’s a vibrant dialogue between tradition, identity, and innovation.

The vibrant community living on Rusinga Island, nestled within the vast waters of Lake Victoria, has served as a profound source of inspiration for many of my most cherished creative works. This island is home to a people whose way of life is deeply intertwined with age-old traditions, passed down faithfully through generations.

Life on Rusinga Island revolves around a deep connection to the lake itself. Fishing is not just a way to make a living—it is a central pillar of their culture and identity. The waters of Lake Victoria sustain the community both economically and spiritually, with fishing, particularly for the small but highly valued Omena fish, being the primary livelihood for many families. These fishing expeditions often take place overnight, requiring skill, patience, and a deep understanding of the lake’s rhythms.

In addition to their rich fishing heritage, the people of Rusinga are known for their expressive artistry, especially seen in the vibrant, hand-painted boats that dot the shoreline. These boats are more than just vessels for work—they are living canvases that reflect the creativity, pride, and cultural expression of the islanders. The enduring ancestral traditions of Rusinga Island—visible in their customs, livelihoods, and artistic expression—continue to be a source of admiration and fascination. They represent a living legacy, one that honors the past while continuing to thrive in the present.

Underneath the Kobe Tree - Your New Home in the Mara.

Kobe Mara is a boutique, unfenced safari camp in the Maasai Mara, offering an exclusive and immersive wilderness experience with direct access to the national reserve.

Stay at Kobe House, a spacious four-bedroom bush villa with open living areas and sweeping savannah views - or at Kobe Camp, where four comfortable, eco-friendly tents bring you closer to nature without compromising on comfort.

Wake to birdsong, fall asleep under the stars. This is the bush, uninterrupted - and it feels like home.

This issue is a special one. Over the past few weeks, we’ve had the chance to reflect on the essence of this magazine, and to go back to where it all began in 2017. The design, the feel, the stories… much has changed, yet the spirit remains the same. Nomad has grown stronger, and with this issue, we’ve reimagined some of our original elements: the logo size on the cover, the layout of the contents page, and the way we give photographs the space they deserve.

That’s why this issue is about legacy: what we carry forward from everything we’ve built and experienced so far. We begin in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, where legacy isn’t just a concept but a way of life. After an inspiring Hot Shots, we dive into Jacky’s story from Kobe Mara: a powerful look at responsible leadership and how one person’s work can inspire many.

We’re also thrilled to share Greta Fiora’s reflections on legacy through the lens of ecology, a piece that’s sure to inspire. And of course, we journey to Lamu, the cradle of Swahili culture, where Ludo explores what the Lamunians leave behind, and what they carry into the future.

Before our 24 hours in Kisumu, Mia brings us back to the present, reminding us that legacy is something we shape every day. What will we, as a generation, leave behind? Travel, like legacy, is about knowing what to let go of and what to hold on to as we move forward. So go, explore, and shape the story you want to leave behind.

Charlotte Breuking,

On behalf of all of us at Nomad Africa

Discover the magic of Beneath the Baobabs Festival (formerly Kilifi New Year), held 30th December–1st January in Kilifi’s baobab forest above Takaungu Creek. Dance under the stars to Afro-House, Electronic, Hip Hop, and Drum & Bass, surrounded by art, nature, and kindred spirits.

Where music meets the wild — Beneath the Baobabs awaits. Tickets available now!

Get ready for a weekend of festive fun at our Christmas Market, where holiday cheer fills the air! Browse through unique handcrafted gifts, indulge in delicious festive treats, and soak up the magical atmosphere with live music and caroling. Bring your loved ones, and your shopping list, for delightful goodies and fun activities for all ages at Shamba, Loresho. It’s everything you need to make this a December to remember!

Footprints of the Past, Guardians of Today, and the Promise of Tomorrow

By Harriet James

On the rolling hills of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital hums with a quiet strength. Here, legacy is not just a word but it’s lived. It’s in the footsteps of those who came before, in the hands of today’s cultural and conservation guardians, and in the promise carefully being shaped for generations yet to come. Kigali is a city where memory of unimaginable loss coexists with vibrant cultural revivals and a forward-looking vision of sustainability and conservation.

The story begins with remembrance. The Kigali Genocide Memorial at Gisozi is not simply a museum but a resting place for over 250,000 victims of the 1994 genocide and a place where history is held tenderly and honestly. Its walls, gardens, and exhibits bear witness to a national wound, reminding visitors and locals alike that forgetting would dishonor the lives lost and risk repeating the past. Memory here is a moral compass: a guide for reconciliation, unity, and a commitment to peace. For international tourists who visit the museum, it’s a lesson to safeguard their nation’s peace and not to take it for granted.

About 30 km from Kigali is Ntarama Genocide Memorial, a former Catholic church preserved. After the genocide, the church was left with victims’ clothing and personal effects still on display. Nyamata Genocide memorial is another church site where thousands sought refuge but were killed. It holds haunting reminders like clothing, identity cards and weapons used. At camp Kigali Memorial or Belgian peace keepers Memorial, 10 Belgian UN peace keepers killed in April 1994 at the start of genocide ae honored. Another memorial is Rebero Genocide memorial which honors politicians who opposed the genocide but were killed for standing against it.

Yet, as Kigali steps confidently toward tomorrow, the balancing act remains delicate. The city has managed to preserve memory without turning trauma into spectacle, grow tourism without eroding dignity, and expand conservation without displacing communities. Climate change, economic pressures, and land use conflicts are ongoing tests of that balance. From that painful history, Kigali has grown a fierce determination to celebrate culture and creativity. Across the city, traditional

drumming mingles with contemporary art installations. Spaces like the Rwanda Art Museum and Kandt House Museum chart the country’s artistic and natural heritage, offering platforms where the past meets modern expression. New initiatives such as the Kigali Cultural Village on Rebero Hill promise to become hubs for performance, craft, eco-tourism, and innovation-bridging tradition and opportunity. Festivals, fashion collectives, and craft cooperatives are weaving a tapestry that is distinctly Rwandan yet globally resonant.

This cultural resurgence is inseparable from Kigali’s environmental rebirth. The city has also emerged as a leader in urban sustainability, transforming its green spaces into symbols of resilience. Nyandungu Urban Eco-Tourism Park, once a degraded wetland, has been restored into a 121-hectare haven of biodiversity, medicinal gardens, and walking paths. Families picnic under young trees, cyclists glide along new lanes, and school groups learn about conservation among

birdsong and reeds. Meanwhile, Umusambi Village offers sanctuary to rescued grey crowned cranes, once trafficked as pets, now free to roam wetlands that double as a public education center on wildlife protection.

Such spaces show Kigali’s understanding that conservation is not only about protecting wildlife but also about nurturing the soul of a city. Environmental NGOs like RECO bring communities together through heritage walks, ecological gardening, and cultural events, proving that safeguarding biodiversity and sustaining cultural identity go hand in hand.

The city’s streets themselves speak of a sustainable future. The Imbuga City Walk, a pedestrian-friendly transformation of the former Car-Free Zone, offers treelined promenades, performance spaces, and bike paths. It is a small but powerful statement: the future Kigali envisions is people-centered, environmentally conscious, and culturally vibrant.

Mourad, also known as *Elmoundo Wild*, started photography when he moved to Kenya for work five years ago and instantly fell in love with wildlife. For him, photography is a poetic experience, where images speak without words. Through his lens, he tries to capture emotions and fleeting moments that reflect the raw beauty of nature. He loves the patience and the observation required to discover new angles and perspectives. That helps him share the wild in ways that inspire others to look closer and differently.

Dennis Munene is a Kenyan photographer and filmmaker whose work captures the quiet poetry of everyday life across East Africa. Rooted in documentary tradition and refined through a fine art lens, his photography explores themes of identity, resilience, and belonging.

A graduate of the Mohamed Amin Foundation in Film and TV Production and Photography, Dennis is best known for his evocative black-and-white imagery — intimate portraits and visual narratives that reveal the strength and vulnerability of his subjects. His work often focuses on underrepresented communities, using light, texture, and silence to tell stories that words cannot.

With a career spanning more than two decades, Mwarv Kirubi is an accomplished photographer and filmmaker recognised for his powerful visual storytelling. He has documented narratives around governance, health, education, development, sports and conservation in more than 15 countries across Africa. His work reflects a deep commitment to capturing moments that inspire, inform and connect people across diverse fields.

By Stratton Hatfield

The Maasai Mara needs no introduction. It’s one of the world’s premier wildlife destinations, where the Great Migration, charismatic big cats, and breathtaking scenery meet the vibrant, deeply rooted culture of the Maasai people. Yet, feeding off this irresistible mix of natural beauty and cultural allure, the tourism industry has often been accused of exploiting this wonder. For some, the Mara has even become a place to avoid. But should it be? Should one of nature’s greatest spectacles really be crossed off your travel list? Or should it be approached with greater care and intentionality? Is it still possible to visit ethically, to experience its magic while supporting the ecosystem and the community that protects it?

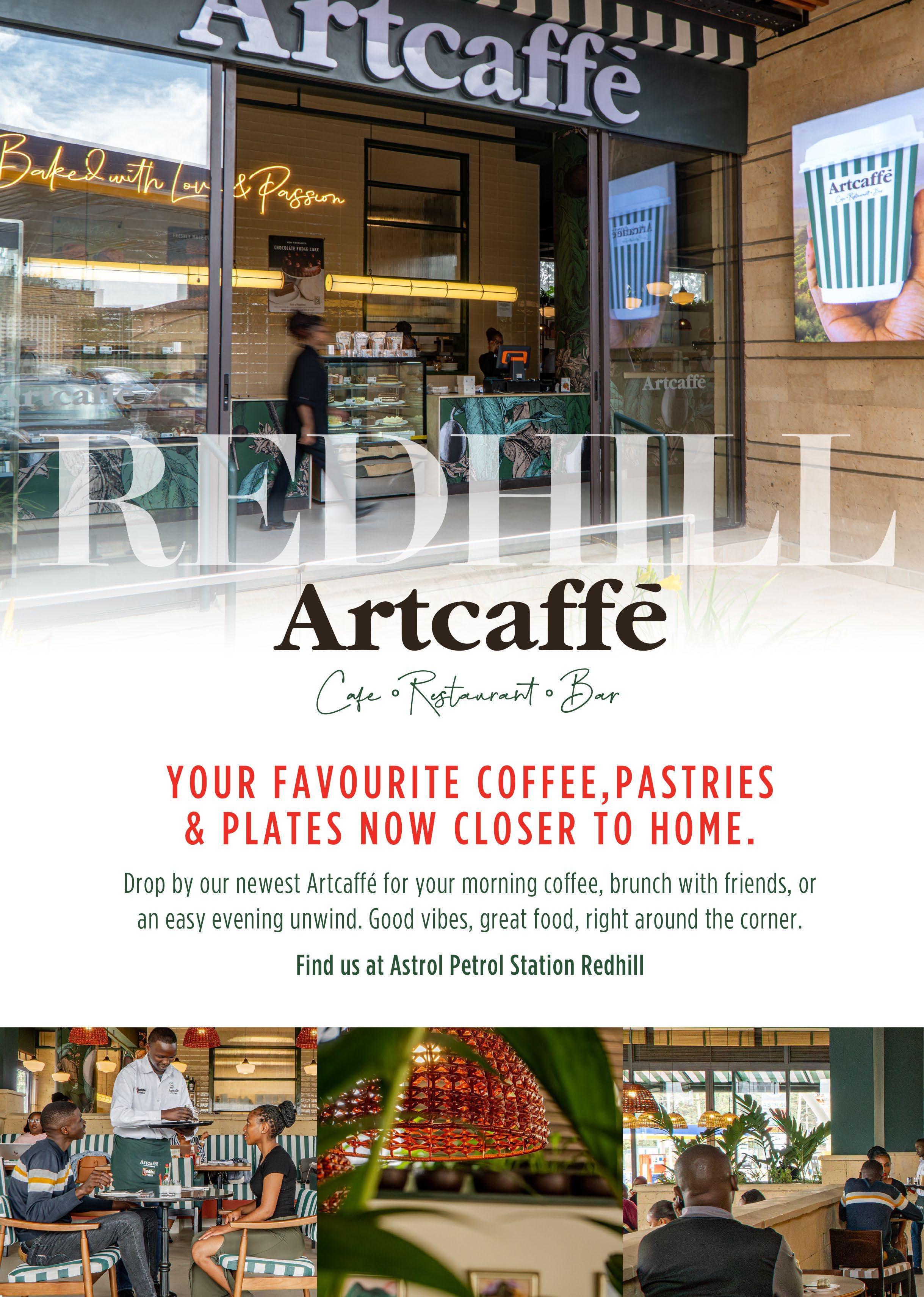

It is Jacky’s story that makes us hopeful, and wanting to visit the Mara tomorrow. Kobe Mara, founded nearly seven years ago by Jacky Sairowua and her family, husband Mike, daughter Fiona, and son Gian, Kobe (meaning “tortoise” in Swahili) is the realization of a Maasai woman’s dream to break into the tourism industry. Jacky is among few Maasai women to own

meaningful shares in a tourism enterprise, a rare achievement in a field where female Maasai ownership remains strikingly low. Her goal is not only to run a sustainable business but also to inspire the next generation of Maasai entrepreneurs.

Jacky’s journey began near the town of Talek, on the edge of the Maasai Mara National Reserve. As the second-oldest daughter in a large family, she was, at a young age, given to an elderly woman with no children, whom Jacky affectionately refers to as her grandmother, to be raised in her care. It’s a practice that builds community and is not uncommon in Maasai culture.

When her grandmother passed away during Jacky’s early teens, she returned to her family, who encouraged her to continue her education at Siana Boarding School, one of the most respected in the region. Yet her path was not without further challenges. Soon after, she faced an arranged marriage proposal, which she bravely resisted. The strength and resilience she showed as a young woman became the foundation on which she has built her life.

Like most Maasai children, Jacky grew up surrounded by wildlife, watching as visitors from around the world came to experience the Mara each year. For her, it was part of everyday life, familiar yet distant. In her early twenties, after meeting and falling in love with her husband Mike, she began to see the Maasai Mara from a new perspective, shaped in part by his experiences as a balloon pilot. It was no longer just her backyard, but an environment she came to value deeply, and one she felt inspired to build her life around.

The first step toward this vision was building their family home on her land in the heart of the Mara. Their eldest daughter, Fiona, grew up watching lions, elephants, and giraffes from her bedroom window. As friends and family visited, it quickly became clear they had created something special, a home in a truly remarkable place. From this, Jacky was inspired to open their home to others, and the idea of Kobe Mara was born.

The early years of Kobe Mara were some of the happiest of Jacky’s life. Sharing her home, the Maasai Mara’s wildlife, and her culture with guests from around the world brought her immense joy. Just as things seemed to be moving in the right direction, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, delivering a devastating blow to her vision. But drawing on the resilience she had developed as a young woman, and with Mike’s support, Jacky sought new investors and rebuilt.

The Kobe Mara you see today reflects that journey. When asked about the future, Jacky’s vision is clear: to see Kobe thrive as a sustainable business that supports families, uplifts the community, protects the ecosystem, and amplifies the voices of emerging Maasai entrepreneurs shaping the future of tourism on their land.

So, if you’re hesitating about whether to visit the Mara, don’t. Come to Kobe Mara and be part of a Maasai woman’s inspiring journey as a tourism entrepreneur in one of the most remarkable landscapes on Earth.

For too long, safari travel in Kenya has been a challenge for travellers with mobility needs. Kiboko River Camp, set along the Galana River, is changing that narrative: thoughtfully, authentically, and impressively. This is not accessibility as an afterthought, but inclusion woven into every detail of the guest experience. The driving force behind this vision is Mr. Siro Brugnoli, the camp’s founder. Having contracted polio as a child, Mr. Brugnoli understood first-hand the barriers that often limit people with disabilities. His determination to create a fully accessible safari experience was the starting point for Kiboko River Camp: a place where no one is left on the sidelines of adventure.

Activities at Kiboko River Camp are tailored to offer both adventure and accessibility. Game drives through the Galana landscape deliver that classic sense of freedom and connection with nature. While fully accessible game vehicles would make bush breakfasts and sundowners even more inclusive, the current experiences are already a joy.

Back at camp, swimming in the pool or simply sitting in the open dining area watching the sunset over the river offers a sense of peace that’s hard to match.

For travellers with disabilities, and their friends or family, the difference is striking. “It was refreshing to see how much thought and effort has gone into creating an inclusive environment,” one guest reflected. “They care, and they deliver what they promise. You can travel to Kiboko River Camp with special needs without a worry in the world.”

One of the most remarkable features of the camp is its pool hoist, a rare find in Kenya and a true game changer. It allows mobility-impaired travellers to enjoy the pool safely and with dignity. On top of that, getting around camp is equally easy thanks to a dedicated buggy, which ferries guests between tents, even to the furthest corners of the property.

Inside the tents, thoughtful design continues. Think smart details such as a clever mosquito net frame, extended from the bedside to create extra space between the bed and the net. This simple but brilliant touch makes accessing the bed smooth and tangle-free, whether using a wheelchair, crutches, or walking aids.

Accessibility in Kenya’s tourism industry is evolving fast, driven by rising awareness, government regulations, and growing demand. Kiboko River Camp is setting the standard, proving that luxury, adventure, and inclusivity can exist side by side when a team works with understanding, training, and commitment. Thanks to Mr. Brugnoli’s vision and lived experience, the camp stands as a beacon of what is possible when accessibility is embraced from the very beginning.

By Greta Francesca Iori

“Legacy” is often imagined as something carved in stone—unchanging, solid, a mark of permanence left behind in the world. We are taught to seek eternalness through monuments, names inscribed on plaques, books written, traditions, rituals. But in truth, nothing in the living world survives by staying the same. Forests burn and regenerate. Rivers carve new paths after floods, changing the very course of their journey. Species evolve or vanish, making space for others. The Earth has always whispered a reminder, that legacy is not rigidity, legacy is transformation, legacy is conscious shapeshifting.

When I think of legacy through the lens of ecology, it becomes clear that its weight has been misunderstood. To pass on something of value is not to fossilise it, but to let it breathe, expand, and adapt to the context of the present, of the future. A seed does not replicate or and recreate its parent tree perfectly. It grows into its own form, shaped by unique soil, water, and sun, each of its branches growing and leaning differently, a testament to the magic of genetic diversity. In this way, every living thing teaches us that continuity does not come from conformity, but from embodying a pattern that can adjust and remain relevant in an ever-changing world. To acknowledge where we come from, but step fully into our own becoming daringly.

Our cultures have often been seduced by durability. Dynasties built pyramids, empires erected castles and statues, nations drew borders and inscribed laws. Yet history shows us that what is rigid eventually cracks. What is too heavy to bend, often breaks. Even the grandest monuments crumble, while the more subtle legacies—the songs, the values, the stories carried and adapted from one generation to the next—flow with the currents of time, often changed by the storyteller, reshaping themselves in each retelling.

In this moment of accelerating change—climate disruption, polarisation, artificial intelligence, wars, shifting geopolitical landscapes and power dynamics in every corner of the world, the question of legacy feels especially urgent.

The natural world has always reminded me that the most enduring legacies are rarely individual. They are always systemic. Mangroves teach us that the most enduring legacies are always interwoven. When the greatest storms come, it is never the strength of a single mangrove stalk that matters, but the resilience of the entanglement of the many roots and trees resisting collectively, creating a wall of strength against the unforgiving winds, waves, and tides. These interconnected beings — cradling nurseries of existence, sediment and shelters for the small and vulnerable guardians of the coast — prove time and a time again, that legacy, then, is not measured by the might of the individual, but by the thriving of the living tapestry it helps sustain.

Perhaps we need to free ourselves from the weight of legacy as personal immortality. Legacy is not about being remembered. It is about what is remembered through us. The knowledge and wisdom we carry is futile if not communal. It is less the statue, and more the soil—the way we enrich the ground for others to grow. Legacy is not a fixed inheritance but a dialogue between what has been and what is emerging. To honour a lineage is not to replicate it exactly, but to embody its essence while allowing it to evolve, to widen the circle of familiarity, perspectives and lived experiences.

Mother Earth lives by this truth. The mycelium beneath our feet, invisible but ever present, does not pass on instructions to fungi through tyranny. It offers a network of exchange, where nutrients and information endlessly flow, without judgement, accepting the many layers and truths in how it experiences itself.

Whether it’s reconnecting with loved ones, discovering a new corner of Kenya, or crossing into a neighbouring land, we craft journeys that stay with you long after you return.

Enquire today

Legacy should not be a burden, but the very portal for liberation. We do not need to carry the weight of ensuring we are immortalised. We are invited instead to contribute to a flow larger than ourselves; to marinate in the collective.

Can we loosen the grip on permanence, so we reimagine a future shaped by those who come after us?

To live with this awareness is to step lightly but meaningfully. Can our impact not be measured by what remains or endures unchanged, but by the unseen seeds we scatter, the unknown narratives we are willing to listen to, and engage with. A fertile ground from which futures we cannot yet imagine may take root.

And perhaps, that is the most radical legacy of all.

Remember when every injury was met with “rub some dirt on it,” or when someone shouted, “Get the blue gum leaves!” for just about anything? Simpler times, sure—but also riskier ones. Today, staying safe is about ditching the myths, embracing smart practices, and knowing when to call in the pros. Here’s how to handle life’s curveballs, East Africa style:

Movies lied to us—don’t suck the venom out. Seriously, don’t.

What to do instead: Stay calm, keep the bite area still and below heart level, and call for medical help immediately. If you’re unsure where to go, rescue.co’s dispatch team knows exactly which hospital stocks antivenom—and when.

East Africa’s sun is gorgeous but unforgiving. One moment you’re enjoying the view; the next, you’re wilting.

What to do: Get into the shade, sip water slowly (no guzzling), and splash cool—not icy—water on your skin. For persistent dizziness, nausea, or confusion, call for help before it escalates. Bonus tip: Wear a wide-

brimmed hat, and always overpack water for safaris or hikes.

Minor injuries don’t stay minor if you skip the basics. What to do: Rinse with clean water, apply antiseptic, and bandage up. If it’s deeper, head to a clinic. A compact first-aid kit can turn a small mishap into a nonissue, don’t leave home without one.

The most crucial advice? Recognize when it’s time to stop guessing and call for help. Rescue.co connects you to experts who can guide you to the right care or dispatch support when it matters most. rescue.co has the biggest and most extensive database of hospitalsknowing what machines, doctors and operating hours they have.

Emergencies are part of life’s adventure, but they don’t have to derail it. Stay cool, stay calm, and stay safe out there!

Yours in adventure, rescue.co

Legacy is an act of hope, and of love. At its heart lies the urge to make sense of one’s life by passing on what ultimately remains beyond our control and interpretation. We’ve explored what it means in the cradle of Swahili culture, through the lens of three Lamunians, by birth or adoption. We asked ourselves: what must we pass on, and what is worth leaving behind?

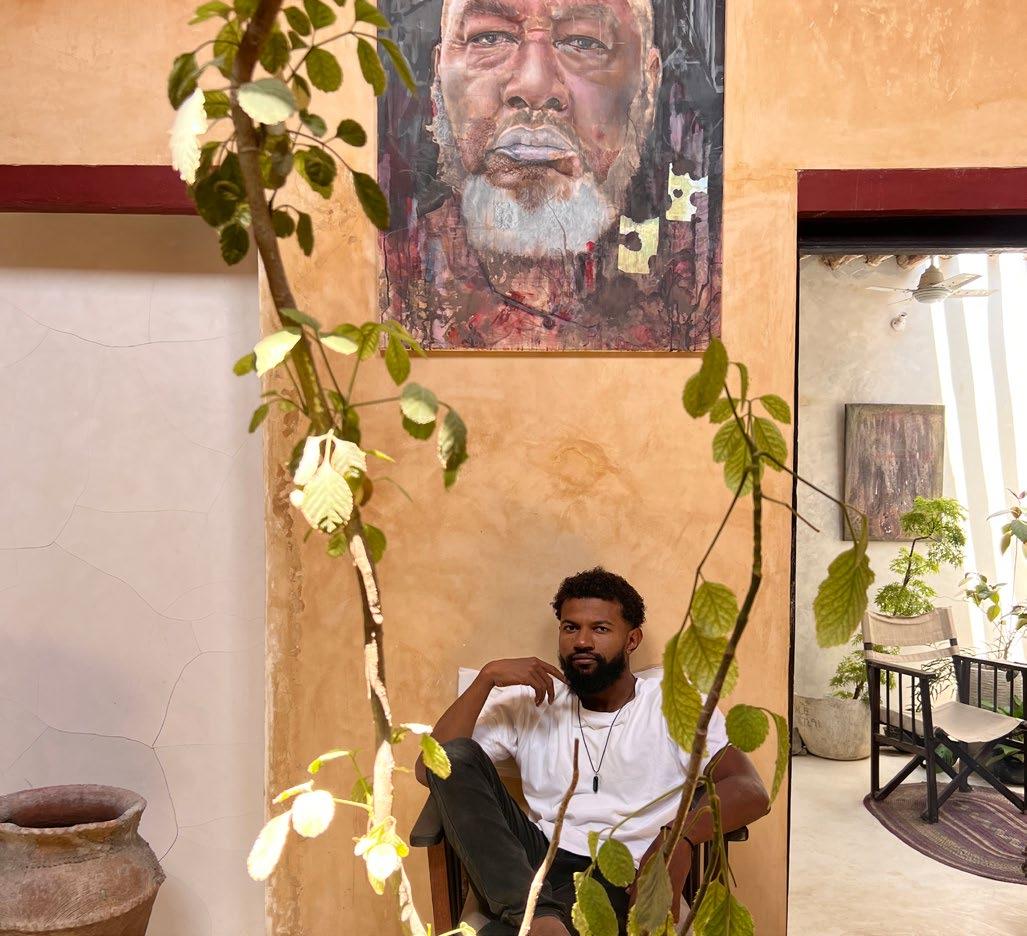

Soudy, a young architect and mixed-media artist, recently renovated a four-room apartment in the Old Town, a reflection on legacy itself. The Swahili sequential room plan remains intact, but new light filters through the ceiling and upper walls. The space also serves as a small gallery, where his and others’ works hang sparsely among simple chairs and cushions. A close-up portrait of his father stands out amid abstract art and street scenes.

“Legacy to me is combining uniqueness and revolution.

I painted my father during a time when valued family deeply. Before I knew the greats who shaped my art and architecture, he was the first to validate my work… always there at my drawing table, silently following my brushstrokes.”

Christina first arrived in Lamu in 1974 as a young Swedish woman and quickly developed a lifelong fascination with Swahili culture and poetry. In 1990, she and her husband Paul returned and, on a whim, bought a historic Omani house behind Lamu Fort, once the governor’s residence under the Sultan of Zanzibar.

They named it Subira House, which means patience in Swahili. Known as Mama Subira, Christina turned it into a beloved eco-rated guesthouse. “Legacy is about joining tradition and innovation. We’ve honoured it through restoring traditional buildings, first in Sweden, then here. We never compromised: caring for the environment, healthy living, and beauty guided us. Everything should please the eye. And we’ve learned from local values; let things come together in their own time, never push, let them unfold naturally.”

The Flipflopi Project, founded in Lamu in 2018, shows legacy as reinvention. It built a dhow, a Swahili sailing boat, entirely from recycled plastic, turning waste into a symbol of environmental responsibility. Building on this, engineer Hassan Shariff now helps design recycled plastic furniture inspired by Lamu’s iconic forms. “The Flipflopi legacy extends far beyond the world’s first recycled dhow. It lives through the recycling centre in Lamu, linking plastic collection, boat building, furniture making, and community education. I support this legacy by creating new innovations to tackle plastic pollution through research on recyclability.”

If legacy is given to us at birth, we learn to shape its meaning over time. It may simply be the art of questioning and finding our own answers. Always, it remains a movement: a living dialogue between history and possibility.

As demand for world-class, flexible work environments accelerates across the globe, KOFISI Africa, the continent’s leading provider of premium workspaces, is expanding its footprint once again.

The company has broken ground on KOFISI Innovation City — a landmark Centre within Kigali Innovation City, Rwanda’s flagship smart business and research ecosystem. Set on a 61-hectare development designed to host global universities, technology firms and research institutions, the new Centre will bring KOFISI’s distinctive blend of five-star hospitality, sophisticated design and enterprise functionality to one of Africa’s most visionary business hubs.

The Kigali project follows KOFISI’s recent $10.5 million investment from London-based Falco Group, part of a $35 million Series B raise fueling the company’s expansion into key African markets. The capital will finance the next phase of KOFISI’s growth as it advances toward one million square feet of premium workspace across the continent.

For KOFISI, the move represents more than just expansion — it signals a shift toward patient, operator-

led investment that delivers both economic and societal impact. “Africa is the market of the future,” says Michael Aldridge, Founder and CEO of KOFISI. “To win here, you need patience, partnership and a willingness to bet on transformation. KOFISI Innovation City embodies that belief — it’s designed to catalyse collaboration, empower local talent and create lasting value.”

With an economy growing at nearly 9% annually and a government committed to innovation, Rwanda has emerged as one of Africa’s most attractive destinations

for business and investment. The Kigali Innovation City development is central to this vision. It is a purpose-built ecosystem where academia, technology and enterprise converge to power Africa’s digital future.

Kigali’s MICE sector, ranked #2 in Africa for international association meetings (ICCA 2024), its thriving start-up culture, and its growing base of multinationals and global organisations. This forward momentum aligns naturally with KOFISI’s mission to create hospitality-led, human-centred workplaces that help businesses scale sustainably and connect meaningfully across borders. Across its 11 Centres in six countries, KOFISI now manages nearly 500,000 square feet of workspace, serving clients such as Google, Amazon Web Services and Bolt.

KOFISI Innovation City will feature a curated mix of bespoke and private offices, flexible work zones, meeting suites, training and event spaces, wellness areas and signature food and beverage concepts. Each element is crafted to foster productivity, well-being and creativity — integrating the service excellence of a luxury hotel with the agility and functionality today’s enterprises demand.

Beyond infrastructure, KOFISI’s model extends to skillbuilding, community and cultural experiences. The company operates Africa’s largest private collection of contemporary art within its Centres and runs a hospitality academy to train staff for the region’s expanding service economy — initiatives that deepen its commitment to local development and cultural exchange.

Welcome to the future of work — coming soon to Kigali.

For inquiries, please contact sales@kofisi.africa

By Mia Ruffo

These unprecedented times should force us to confront the idea of legacy. It is often in the darkest moments, we can most clearly see: the imprint we leave on this planet and future generations is lasting. Just as an individual leaves a legacy, so too does a generation through the societal structures, environmental conditions, and values it passes down. Yet the systems we have inherited were never designed for long-term resilience, only for shortterm gain. And as the world spirals into ecological breakdown, mass atrocities, and social unrest, it is clear how far we have strayed from a collective future.

In East Africa, where the scars of exploitation run deep, the question feels especially urgent: what kind of future are we shaping when the systems sustaining it are failing?

Tourism in the region has walked a thin line between preservation and depletion. Safaris, while vital to conservation funding, have left behind inequalities and ecological strain. The Maasai Mara embodies this paradox in conservation, where protection and exploitation compete.

Over the past two decades, an unchecked boom in luxury lodges, camps, and roads has carved through wildlife corridors and fragmented habitats with little regulation. During the Migration especially, hundreds of vehicles crowd river crossings, eroding banks and distressing wildlife already fighting for survival, sometimes forcing herds to change routes. Vital water sources, like the Mara River, are compromised by pollution, upstream deforestation and overuse. Meanwhile, much of the wealth generated flows upwards, leaving Maasai and neighbouring communities with a fraction of the rewards and shrinking access to land and resources.

undermining ecosystems and the people it depends on. But a new generation of small, independent camps is reimagining what it means to belong to a landscape, rather than simply operate within it, championing alternatives based on balance, partnership, and authenticity.

Among them is Tor’s Camp, nestled in the riverine forest along the Olare Orok River. Founded in 2022 by brothers Cameron and Sean Grant and their cousin Hamish Hughes, Tor’s was born out of a love of the bush rather than a hotelier concept. “We wanted to preserve that spirit of wild camping while adding the comforts that really matter.” explains Sean.

Having grown up connected to Speke’s Camp, the trio had experience in the wilderness but little in hospitality. That inexperience proved to be an asset: without preset formulas, they created something grounded. Tor’s is deliberately stripped back: raised tents with open-air bathrooms allowing the forest to reach in, while gullies form natural borders giving each tent a secluded pocket of wilderness. It is a purposefully wild experience reminding guests they are visitors within a living ecosystem- though one that can still be enjoyed from the comfort of a soft bed or chesterfield sofa beneath the trees.

From the start, their relationship with the community was central. They leaned on local knowledge and networks to source materials, hire their team, and navigate community matters. Their lease reflects this ethos of partnership, as the land is co-owned by community members alongside Narok County, with Tor’s paying both rent and a share of every booking.

It is a model of tourism that sustains itself while

More than 80 percent of the team comes from neighbouring villages, and they work exclusively

with self-employed local guides- something rarely done, as it limits control and reduces profit per safari. These guides represent a growing group of entrepreneurs who have invested in their own vehicles, licensing, and training, seeking professional freedom rather than relying on salaried employment. One guide, Ben, explains how this can also help reduce human-wildlife conflict. “Many people have to sell their livestock to purchase a vehicle.. it reduces the amount of people relying on cows”.

Tor’s champions an alternative model that values shared growth over centralised control and supports a more diverse local economy. “What we’re hoping to leave behind is a camp that has played a part in building the agency of local entrepreneurs, and changed the system- however much we can.” says Cameron.

Tor’s reflects a wider shift across the industry. The conversation is no longer just about being “sustainable”; it is about reimagining the systems themselves and challenging extractive, exploitative practices to position tourism as a force that can regenerate and strengthen bonds between people and the environment.

What we pass on is never neutral. It is the sum of our choices: what we value, protect, exploit or neglect. For too long, dominant models across all industries have prioritised profit and power over humanity and nature. Perhaps the most meaningful legacy is a conscious one that recognises our shared responsibility and cultivates systems of equity and longevity within the spaces we inhabit and the industries we shape. Because every decision contributes to the collective future we will leave behind.

By Sam Bailyn

When it expanded to a nationwide scale earlier this year, The Greatest Wildlife Photographer of the Year – Kenya took a bold step forward. What began as a celebration of the Maasai Mara’s iconic landscapes and wildlife evolved into a platform that now embraces the country’s extraordinary ecological diversity, from the savannahs of Tsavo to the forests of Mount Kenya and the coastal mangroves of Lamu.

This shift wasn’t just geographical; it was a deepening of purpose. By opening the competition to all corners of Kenya, the organisers sought to highlight the country’s

lesser-known conservation stories, communities, and species that rarely make the spotlight.

To turn this vision into impact, the competition partnered with six conservation initiatives across different regions, each benefiting from funds raised through entry fees. Since its inception, it has generated more than one hundred and fifty thousand dollars in support of wildlife and habitat protection, with this year already on track to be its most successful yet.

The competition closed at the end of October. Stay tuned and follow their page to discover the winners

Uniting safari, photography, and conservation, the organisation has pledged that 100 % of entry fees will go directly to its six Conservation Partners , who represent a diverse range of conservation efforts.

Elephant Project (MEP) protects elephants and their habitats across the Greater Mara Ecosystem. Its goal is a stable elephant population coexisting peacefully with people. Through patrols, conflict mitigation, and research, MEP safeguards elephants and supports local communities.

The Elephant Queen Trust runs a nationwide education programme inspired by the film The Elephant Queen. Using film, theatre, music, and puppetry, it promotes humanwildlife coexistence in schools and communities affected by conflict.

The Pangolin Project (TPP) protects pangolins and their habitats by securing land in biodiversity-rich areas and partnering with local communities. Its team connects people, pangolins, and the planet through research, habitat protection, and engagement.

The Kenya Bird of Prey Trust (KBPT) secures healthy raptor populations by protecting habitats, restoring species, and educating communities. Through research, rehabilitation, and outreach, KBPT conserves Kenya’s birds of prey.

Founded in 2007, the Grevy’s Zebra Trust (GZT) protects the endangered Grevy’s zebra— fewer than 3,000 remain in the wild. Working mainly in northern Kenya, GZT combines community engagement, research, and innovation to secure the species’ future.

Ewaso Lions protects lions and other large carnivores while promoting coexistence with communities in northern Kenya. By engaging warriors, women, elders, and children through research and education, it reduces conflict and builds local stewardship of wildlife.

By Harriet James

Kisumu is more than just Kenya’s third-largest city, it’s a vibrant tourism destination brimming with culture, wildlife, and breathtaking scenery. Whether you’re savoring fresh fish at a lakeside shack, listening to folklore at Kit Mikayi, or cruising across Lake Victoria, Kisumu invites you to slow down and experience Kenya from a new perspective. In a country celebrated for its safari parks and coastal resorts, Kisumu is a reminder that some of Kenya’s richest experiences happen off the beaten path.

Start with breakfast at either a local café or the hotel where you spent the night and apart from the usual English tea with bread, bacon and sausage, try out their nyuka or porridge a common Luo breakfast made from millet or sorghum.

For lunch, apart from fish try out aliya which is sundried fried bird eaten with brown ugali. Make sure you try out

their traditional veggies like osuga, or akeyo prepared simply with oil, onions and tomatoes.

For wildlife lovers, the Kisumu Impala sanctuary, which is just a few minutes from the city center, is the haven to spot impalas, zebras, giraffes, cheetahs, and a rich array of birdlife. The sanctuary’s walking trails and picnic areas provide an easy way to enjoy nature without leaving the city. About 3 to 4 hours’ drive from Kisumu is Ruma National Park too where one can enjoy a game drive in a less crowded setting.

For adventurous, hiking Kit Mikayi, a towering rock formation is steeped in Luo folklore is something you shouldn’t miss. Climbing through the massive boulders is the only way to enjoy the sweeping views of the surrounding countryside, the shimmering expanse of Lake Victoria, and the rolling hills of Nyanza. Ndere Island National Park is another destination for adventure lovers as the island offers a peaceful escape

filled with wildlife, culture, and breathtaking views. The journey across Lake Victoria typically takes 30–45 minutes, depending on your departure point and weather conditions. Once you get there, visitors can hike gentle trails through rolling grasslands for panoramic vistas of the lake, Homa Hills, and distant Mageta Island, or enjoy quiet game viewing of impalas, zebras, waterbucks, monitor lizards, and a dazzling variety of birds like fish eagles and herons.

For art lovers, the Art House (on Oginga Odinga Street) is an engaging stop. It showcases works by local artists and has everything from paintings, sculptures, to modern craft, giving insight into contemporary culture in Kisumu.

For history and culture lovers, the Kisumu Museum offers insight into Western Kenya’s heritage. From archaeological exhibits to reconstructed Luo homesteads, it’s an educational stop that deepens your appreciation of the region. There is also the Jaramogi Odinga Mausoleum which is around 2 hours from Kisumu town, a historical site dedicated to Kenya’s first Vice president and his family Jaramogi Odinga. The site also has political history exhibits.

For the market experience, Kibuye Market, one of Kenya’s largest open-air markets, is an explosion of color, sound, and local life. Browse crafts, sample street food, and watch Kisumu’s bustling commerce unfold. For the night life, the city boasts an emerging nightlife scene, with waterfront restaurants and bars offering live music and local cuisine. Dunga Hill camp or Hippos point is the place to be for a lively gathering of locals and visitors alike where you can either take a boat ride or catch live music as the sun sets.

Depending on your budget or preference, Kisumu has a wide range of accommodations, from high end hotels like Sarova Imperial, Acacia Premium, Ciala Resort to guest houses like Mona Lisa Guest house and Airbnb.

Sign up for our newsletter and be the first to receive travel inspiration, deals and more!