A New Take on Clay: A Dialogue Between Iceland and Poland

Is a new, fresh take on clay—a building material utilised in architecture for centuries—still possible today? Can clay still inspire, surprise and take on new forms? Our project connects two seemingly distant worlds: north-western Iceland and the Polish Świętokrzyskie region. One is an austere, volcanic island, the other—one of the geologically oldest areas of Europe. Despite their differences, both countries share a deep connection with nature, landscapes, and a reliance on local resources.

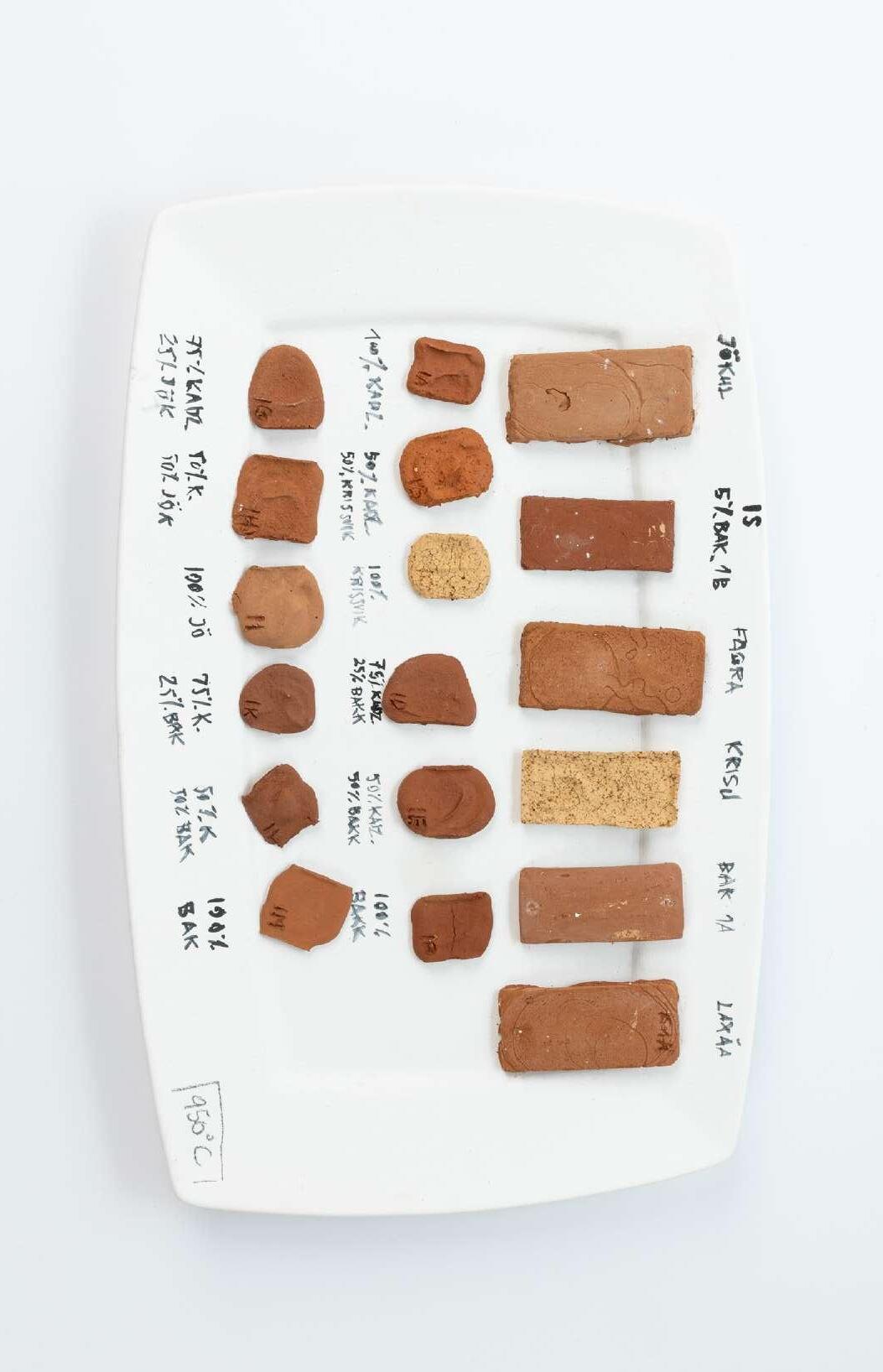

In Poland, clay was for centuries used in construction, particularly in the form of ceramic bricks—a widely available, durable and heat-retaining material. Today we want to look at it differently—see it not only as a material, but also a vessel for identity and stories of its origin. Icelandic clay is completely different from Polish—more runny, more difficult to process. However, during our exploration of Iceland we found out that there are also deposits of clay suitable for the production of ceramic tiles, cladding or smaller architectural elements. This discovery opened up possibilities for further experimentation.

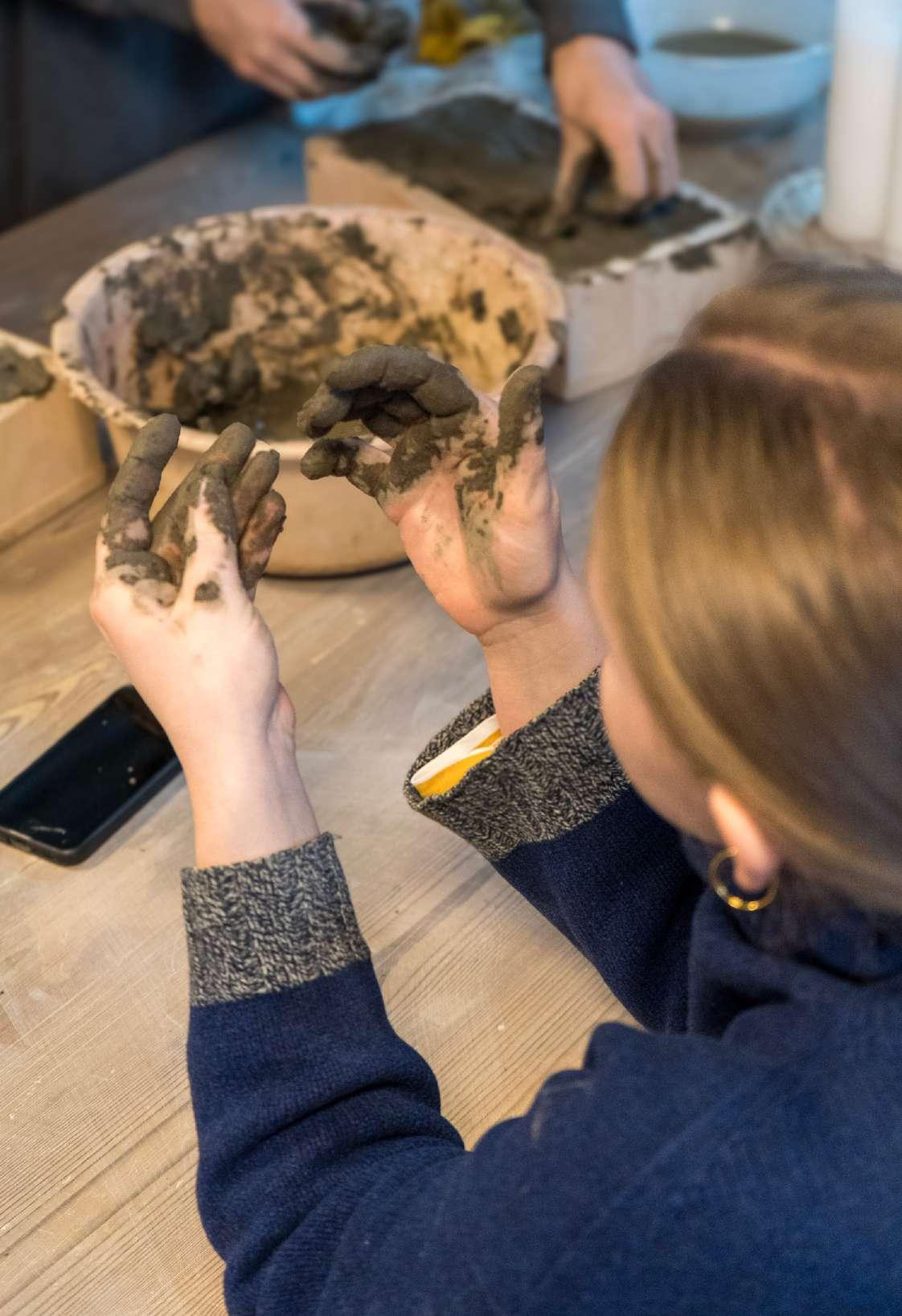

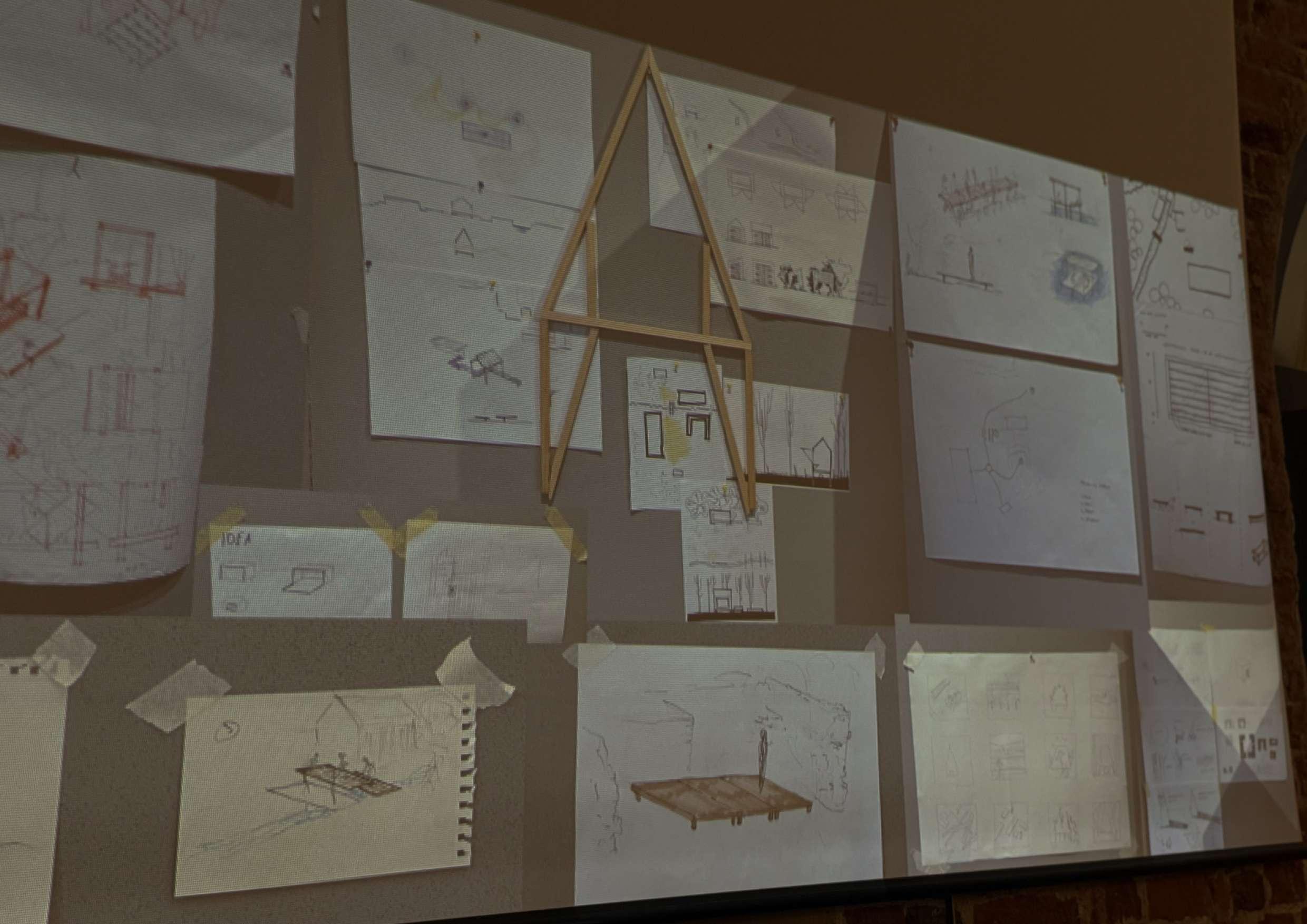

The first part of the project involved a week-long visit of the participating designers to Kielce and took place in late January 2025. The programme included workshops and study trips i.e. to the Kadzielnia nature reserve, where the first material samples were collected in a cave, and to the brickworks in Rytwiany, which has operated continuously since 1812. After the research and theoretical part of the study trip, it was time for hands-on work in studios and workshops. The participants created prototypes of their designs and documented their creative process. The results of their work are currently on display in the Institute of Design in Kielce; the exhibition is open until the end of May 2025.

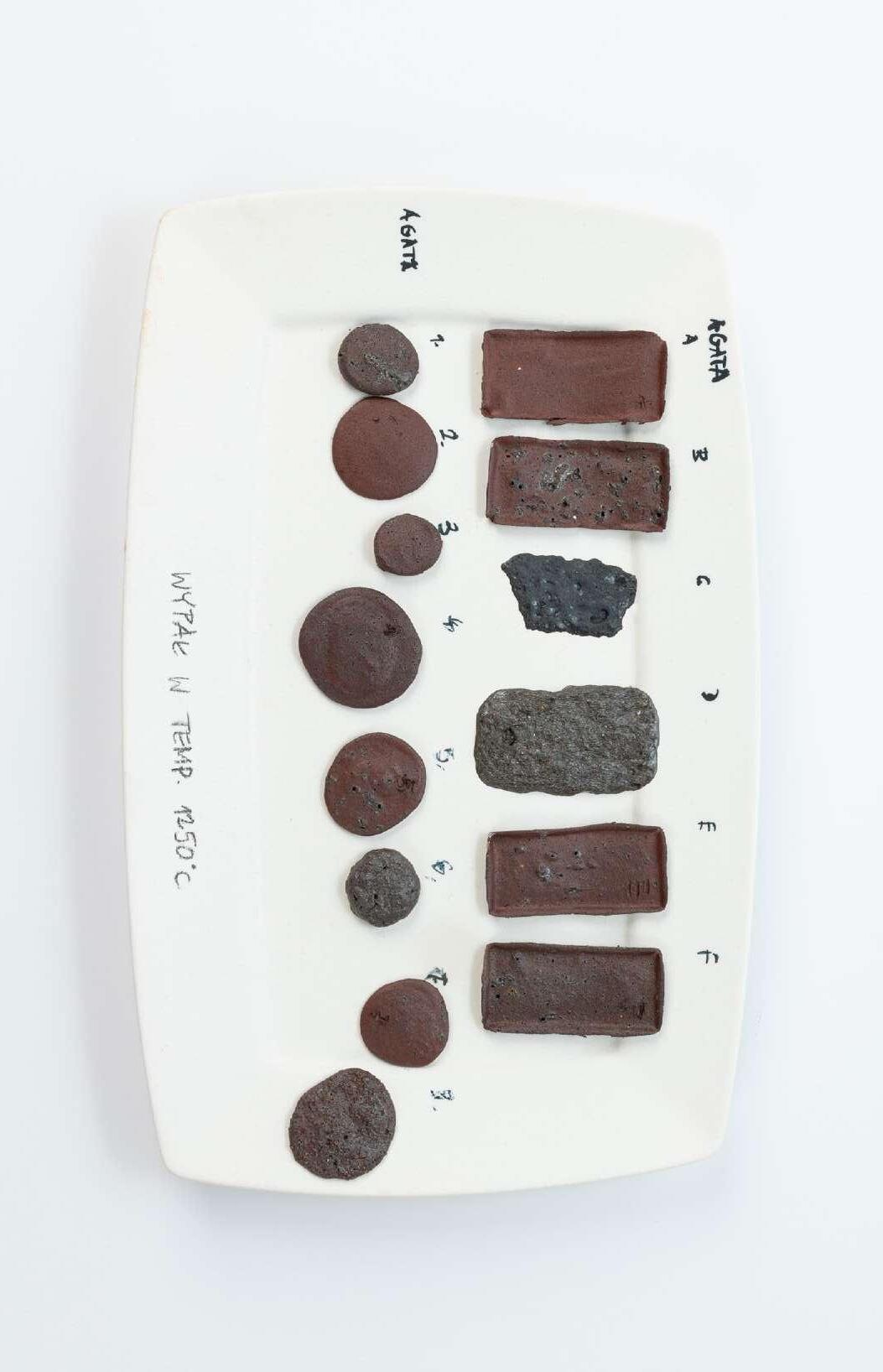

The final phase involved a study trip of the representatives from the Institute of Design and the National Institute for Architecture and Urban Planning to Iceland. Our stay there began with site visits to collect samples. During the workshops that followed—and again connected creatives from both countries—we began developing our concept for a new type of brick. The material we created combines the properties of Icelandic and Polish clay, as a symbolic and literal attempt at connecting the two places, histories, and technologies.

The ‘Out of Clay and Wood’ project proved that even a material as common as clay can become the basis for international cooperation, rediscovery of local identities and creation of entirely new forms of expression. It is also proof that working with a local material can lead to universal conclusions and real connections between people of different backgrounds.

D. Janicka, M. Dachnowska

The ‘Out of Clay and Wood’ project looks at clay—a material which has for centuries been used by humans to build homes, vessels, furnaces and stories. Even though clay is widely known and ubiquitous in almost any terrain, it still carries immense utilitarian, but also cultural, emotional, and symbolic potential. In the Świętokrzyskie region, its meaning is rooted especially deeply. It is here that the soil ‘speaks’—of geology, history and the hands that formed it.

The history of pottery in Chałupki

Chałupki—a small village known for the mastery of its potters—is one of the places with especially strong ties to the region’s clay traditions. It is a place where soil was not only a resource, but also part of life, spun in workshops, dried in the sunlight and burnt in the kilns.

The earliest traces of pottery in Chałupki date back to the Roman times, as evidenced by fragments of vessels and remains of furnaces discovered by archaeologists. Although the first written records of the village appeared in the 18th century, historians of the region suggest that the local pottery craft originated up to 200 years earlier. Deposits of karst clay, characterised by its superb plasticity and remarkable durability, played a key role in its development.

Throughout the 19th and until the turn of the 20th century, pottery was the foundation of economy in the region. Local craftsmen produced both household items—such as jugs, bowls, pots—and decorations. These products were sold at local fairs but also transported out of the region by merchants and traders. Important to note is that, contrary to municipal guilds, pottery in Chałupki developed independently, founded on collaboration between artisans, mutual aid, and shared experiences.

Among the most prominent local artisans were Józef Głuszek, who decorated his vessels with intricate patterns made by knurls and stamps, and Stefan Sowiński—author of figural ceramics, acclaimed both locally and outside the region. Other notable representatives are the Kozłowski and Armański families, for whom pottery was not only a craft, but also a family tradition.

The second half of the 20th century brought significant changes to the pottery traditions of Chałupki. Decorative forms started dominating over household ceramics production, and the number of operating workshops decreased significantly. Despite attempts to keep the tradition alive (e.g. through the support of the Chałupnik cooperative from Iłża), the craft slowly began to disappear. While there were 62 potters in Chałupki in 1953, the number of artisans dropped to only 15 in just 20 years. Stefan Sowiński’s passing in 1993 marked a symbolic end of the era.

Although today pottery manufacturing in Chałupki remains a distant memory, its traces still resonate in the local identity. We took this legacy as a point of reflection—on what contem-

D. Janicka, M. Dachnowska

porary design can derive from tradition, and how designers can translate it to the language of contemporary forms and ideas.

Brickmaking—a tale from Rytwiany

Pottery is not the only tradition founded on clay from the Świętokrzyskie region. No less important is the legacy of brickmaking—the utilitarian, tough and often overlooked craft that is key to what our cities and villages look like.

Clay used for brickmaking was easily accessible, high quality and deposited near the surface. Appropriate facilities—access to water and wood for firing and transportation—were all that was necessary for establishing brickworks. In the 19th and at the turn of the 20th century, almost every larger town in the region had its own factory and brick was considered the basic construction material.

The Rytwiany brickworks, operating continuously since 1812, stands out among other local manufacturers. The Rytwiany bricks have for decades been used to construct houses and other buildings both locally and outside the region. This remarkable place keeps the brickmaking traditions alive until the present day, producing bricks with methods such as hand-forming, air-drying and firing in a wood furnace.

During the ‘Out of Clay and Wood’ workshop, we could see this process up close—observe its physicality, but also notice a rhythmic quality, reminiscent of artistic practices. Despite its industrial origins, the Rytwiany brick is a vessel for stories of the place, time and human labour.

The brickwork still operates to this day, its presence a tangible proof that even in the age of mass manufacturing we can still preserve the quality, local character, and cultural continuity.

Geological structure of the Świętokrzyskie region: from Paleozoic seas to ceramic clays

Michał Poros

Holy Cross Mountains UNESCO Global Geopark michal.poros@geopark.pl

An outline of the geological structure of the Świętokrzyskie region

The geological history of the Świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains—the lowest mountain range and at the same time the most remarkable region in Poland, is the driving force behind the morphology, climate, biodiversity, and the development of settlement and economy of this area. The Holy Cross Mountains UNESCO Global Geopark, located in the western part of the mountain range and officially established on 21 April 2021, is characterized by a natural and cultural specificity that reflects the aforementioned key features.

From the geological point of view, the Świętokrzyskie Mountains are situated within the great disruption of the Earth’s crust, called the Trans-European Suture Zone. The Świętokrzyskie Mountains region is the only segment of this zone in which sedimentary rocks representing the sequence of all geological periods from the Cambrian to the Quaternary are outcropped. Therefore, the scientific studies of this region are of fundamental significance for the understanding and reconstruction of the geological history of the European continent.

The geological identifiers of the Świętokrzyskie region are primarily sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, which contain numerous and diverse fossils. Among these, the most significant in the geological structure of the region are Devonian, Jurassic, and Neogene limestones; Cambrian, Devonian, Triassic, and Jurassic sandstones; as well as Permian conglomerates. The most recognizable fossils include the remains of corals, sponges, brachiopods, and bivalves, fossilized ammonite shells, and vertebrate traces—especially Devonian tetrapods and Jurassic dinosaurs.

The most important geomorphological feature of the Świętokrzyskie area is its structural morphology which corresponds with the geological structure. The lithological diversity is reflected in the land relief. It also has a significant influence on the diversification of water relations and soils, and thus on the natural vegetation and human land use.

The documented history of man’s inhabitancy in the western part of the Świętokrzyskie region dates back about 60,000 years, to an epoch called the Pleistocene. Remains of Neanderthal camps were discovered in the Raj (Paradise) Cave—the most beautiful cave in Poland. Further events of human activity in the western part of the Świętokrzyskie region are recorded in more than 200 archaeological sites dating back to the Stone Age; the religious and secular architecture, as well as numerous remains of ore and rock mines dating back to the Middle Ages.

Occurrence of ceramic clays in the Świętokrzyskie region

Clays are the primary raw materials for ceramic production found among the sedimentary rocks of the Świętokrzyskie region. Karst

clays, found in karst sinkholes mainly within Devonian and Jurassic carbonate rocks, as well as Pleistocene tills are also used to a lesser extent. It is important to note the differences between clays and tills, as—from a geological perspective—they represent distinct types of sedimentary rocks.

For geologists, till is a sedimentary rock composed of smaller and larger fragments of other rocks, such as mudstone, silt, sand, and sometimes gravel. These rocks also contain iron compounds and calcium carbonate. Depending on its origin, the proportion of these components and the characteristics of the rock can vary. Till is formed from mixed rock material that was transported by an ice sheet or glacier and deposited on the Earth’s surface after the ice melted. Due to their high level of impurities, tills are rarely used in ceramic production.

Weathered clays, on the other hand, are formed as a result of the weathering of rocks. One such example is kaolin, composed mainly of the clay mineral kaolinite. When mixed with water in appropriate proportions, kaolin becomes a key material in the production of fine ceramics.

Another example is karst clay, which forms through the karst weathering of carbonate rocks (mainly limestone) under terrestrial conditions. These clays usually occur in irregular accumulations within depressions and karst fissures. This type of clay was the primary raw material for the development of pottery workshops in the village of Chałupki, located in the municipality of Morawica near Kielce.

Clays are sedimentary rocks composed almost entirely of fine clay minerals, with grain sizes not exceeding 0.01 mm in diameter. The term ‘ceramic clays’ is used when referring to clays used in ceramics. These rocks formed in the past—and continue to form today—as fine sediments accumulating on the bottoms of calm seas or in terrestrial environments such as lakes, wetlands, and river valleys.

In the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, the most recognizable examples include the red and cherry-colored clays from the Lower and Upper Triassic (Baranów, Pałęgi), as well as the dark clays from the Lower and Middle Jurassic (Sołtyków, Gnieździska, Fanisławice).

The origin of clays found in the Świętokrzyskie region

The clays found in the Świętokrzyskie region have diverse origins, depending on the climatic and environmental conditions in which they formed. In the areas of Chałupki and Łagów, where pottery workshops once operated, the most common are karst clays. These deposits mainly formed during the Neogene period (23–5.3 million years ago) in a landscape and climate similar to today’s Mediterranean zone (ill. 1). The clay-rich sediments, that eventually became clays, accumulated in natural traps—karst voids and depressions— created as a result of the dissolution of carbonate rocks (mainly Devonian and Jurassic limestones) by water.

The extraction of these rocks in open-pit mines has led to the exposure of quarry walls, revealing voids and karst sinkholes filled with clays and sands of various colors. The diverse coloration of karst clays is linked to the presence of either divalent or trivalent iron in the main component of the clay, which is the clay mineral known as illite. Environmental conditions and the surrounding rock types in which the clay deposits formed may also have influenced the variety of colors.

A typical example is the deposits of Neogene karst clays found in karst depressions and sinkholes formed within Upper Jurassic limestones in the area around the village of Chałupki. These deposits gave rise to one of the most important and oldest pottery centers in the Świętokrzyskie region.

When discussing Świętokrzyskie clay, it is necessary to mention the presence of glacial clays and clay-rubble weathering layers, which are remnants of the Ice Age during which the Świętokrzyskie Mountains were either covered by an ice sheet or located at its foreland. Due to numerous admixtures of sandy and gravelly material, these clays were not widely used in artistic ceramics.

Diversity of ceramic clays in the Świętokrzyskie region

Clays and mudstones, currently or historically used as raw materials for the production of artistic or building ceramics, can be found in many locations throughout the Świętokrzyskie region. These include both large mudstone deposits exploited in open-pit mines (e.g., Pałęgi) and small, localized occurrences of ceramic clays that were extracted until the 1990s from shallow pits or shafts (e.g., Chałupki).

It is also important to highlight the presence of numerous sites with multicolored karst clays in the region, exposed in karstified zones of Devonian limestone and dolomite deposits, as well as in Jurassic limestones and marls, all mined in open-pit quarries. In such cases, the clays are considered mining byproducts. Nevertheless, they have found use in individual experiments and artistic projects—such as the ‘Glina Świętokrzyska’ (Clay of the Świętokrzyskie Region) project and exhibition organised by the Institute of Design in Kielce.

Greiner

The Extruded Realities project explores the tension between locality and globalization by linking Icelandic and Polish food culture, asking: when is something truly local, and when is it just another node in a hyper-globalized system? Objects, much like food, are never neutral—they exist within networks of production, distribution, and cultural meaning.

The extruded clay hot dog holder makes this entanglement visible. Its form directly mirrors the mechanized production of sausages, yet its material—clay—ties it back to craft and place. It sits between the industrial and the handmade, questioning how objects mediate our relationship with food, tradition, and the infrastructures that sustain them.

By isolating a single element of an everyday meal, the project turns something familiar into a question: how do hidden systems shape what we think of as ‘local’?

Max Greiner is a 25-year-old designer from Germany with a Bachelor’s degree in Industrial Design. Having lived and studied in Halle, Gothenburg, Eindhoven, and now Reykjavik, Iceland, he has explored diverse design philosophies and approaches. His work focuses on material-based development and object design, delving into the inherent narratives and complexities of materials as starting points for projects. Collaborating with experts across disciplines, Max embraces a holistic methodology driven by interdisciplinary dialogue.

Max

Natalia Budnik

As a landscape architect, I was interested in exploring the origins and processes that shape the clay ground layer, which not only has a visual impact on the , vegetation and colour palette, but also affects how the landscape functions. During the workshop, I gained a deeper understanding of the geological processes that form clay over vast periods of time. I realized how the microscopic particles give clay its unique plasticity. This hands-on experience highlighted how early in the human history it was that we learned to harness these qualities for practical use in daily life, such as building with bricks or rammed earth.

The workshop inspired me to return to the traditional technique of pond clay lining and made me appreciate the connection between the material’s natural properties and its enduring role in craftsmanship and sustainability. A dew pond is a man-made water feature designed to collect and store water. It typically consists of a shallow, basin-like depression and is often lined with clay to prevent water from seeping through the ground. The clay lining helps retain moisture, allowing the pond to collect water from dew, rain, and runoff. Various regions used different methods to construct pond layers; some incorporated lime that reacts with the clay to create a more effective seal. The resulting bright, reflective surface also helps prevent drying and cracking.

Dew ponds are often used in areas with low rainfall, providing a water source for livestock or wildlife. The workshop inspired me to apply these insights to my work in landscape architecture, particularly when looking for alternative sealing materials in rainwater management.

Natalia Budnik is a landscape designer with a strong interest in the dynamic potential of vegetation and its role in shaping climate adapted landscapes. She works on long-term goal strategies and nature-based design solutions in modern urban spaces. She combines her design with research and hands-on experience. From 2014 to 2019, Natalia worked at SLA, a Copenhagen-based design office known for pioneering green urbanism. During her time there, she contributed to various projects that integrated ecological systems with urban development, helping reshape cities as climate-adaptive spaces. As a graduate of the University of Copenhagen, Natalia also taught the Design by Management course, combining creative design with practical green project management. She collaborates closely with artists, architects, urban planners, and cultural institutions to create landscapes that grow, change, and foster deeper connections with nature.

On the first day of the workshop, we visited a traditional brick factory. It was fascinating to observe a large machine that mills and extrudes clay. Later, the long extrusion was divided into multiple breeze blocks with a thin metal wire.

The research project aimed to replicate the manufacturing method in the workshop and produce a 1:1 mock-up of the tile facade. To make the task more challenging, I made it my objective to create a tile with a corrugated profile, rather than a simple flat one.

In the workshop, a smaller version of the industrial clay extruder was already set up, operating similarly to the one in the factory. Unfortunately, it could only produce profiles with a maximum width of 8 cm. Since the desired tile needed to be wider, I conducted a series of tests to develop a new method suitable for a larger scale.

The first attempt involved combining several thin profiles into one, but failed due to joints being too weak. The next approach was to work with a negative, comb-shaped wooden profile. While this method proved successful, it was slow and required many repetitions to shape the tile precisely. When I tried to speed the process up, the clay would break. However, when done correctly, this method resulted in a well-formed shape.

Ultimately, the idea of creating a plaster mould emerged as a quick and efficient way to produce identical tiles. The tile made in the previous step served as a model. While the plaster took a few hours to dry, the rest of the process was swift and straightforward.

Before the clay was fully dry, the standard corrugated rectangular tiles were cut into new, individual, rounded shapes. The tiles were then fired, arranged into a composition, and mounted on a wooden substructure as a mock-up. With a little more time and a few additional people to help, we could have even constructed a small pavilion.

Michał Kulesza is an architect and researcher interested in reusing buildings, with a focus on their social, ecological, and cultural values. He holds M.Sc. in Architecture from the Warsaw University of Technology (2019) and was awarded a scholarship for an interdisciplinary research program at Stanford University. He published in OASE and Practices in Research. Professionally, he collaborated on exhibition projects for the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2018) and was employed by the Swiss office Christ & Gantenbein (2019-2022). Presently, he is based in Brussels and works at noAarchitecten.

Matylda Wolska

I consider earth to be the most ‘democratic’ building material. Firstly, because its manufacturing is carried out locally, which reduces its environmental impact and simplifies production. Secondly, because building with clay requires neither complicated technologies, nor advanced skills. Rammed clay of the Świętokrzyskie region can produce a wide array of results, as evidenced by our two blocks. The first prototype is the result of a calculated erosion, which gave the element a grainy, corrugated texture. Its rough surface could become populated by non-human organisms.

One of the challenges in creating rammed earth blocks is their considerable mass which makes them difficult to move. Attempts at solving this issue are illustrated in the second prototype, in which finely chopped paper was added to the clay mix. Light cellulose fibres serve as filling of the block, allowing it to maintain similar properties as the block made of pure rammed earth, while at the same time minimising its weight.

Mix I:

25% clay from Kadzielnia

25% fine-grained sand

50% gravel

Mix II:

25% clay from the brickworks

20% fine-grained sand

20% gritty sand

35% paper pulp

Matylda Wolska is a student at the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. She is a laureate of multiple national and international competitions, including the BB Green Award, Mies+ WAPW, Young Architect’s Challenge, and the Halina Krzemińska Grand Prize for her engineering project. Her diploma work has also been recognized in several categories, such as Pro-environment Diploma, Diploma with Archicad, and the OW SARP Award in Engineering Projects. Her academic and design interests lie at the intersection of architecture, behavioral neurobiology, sociology, and sustainable development. She is passionate about exploring how built environments influence human behaviour and well-being.

The first thing that caught my attention when I entered the Institute of Design in Kielce was a wooden architectural model made by Alexandra Wróbel. Up until this point, I had only made architectural models out of white bookbinding paper, which seemed to be the standard material for model making. Seeing how she used wood both as the base and mass of the model, combining simplicity with innovation, made me curious about experimenting with alternative materials like wood and clay and exploring their potential in different model-making processes.

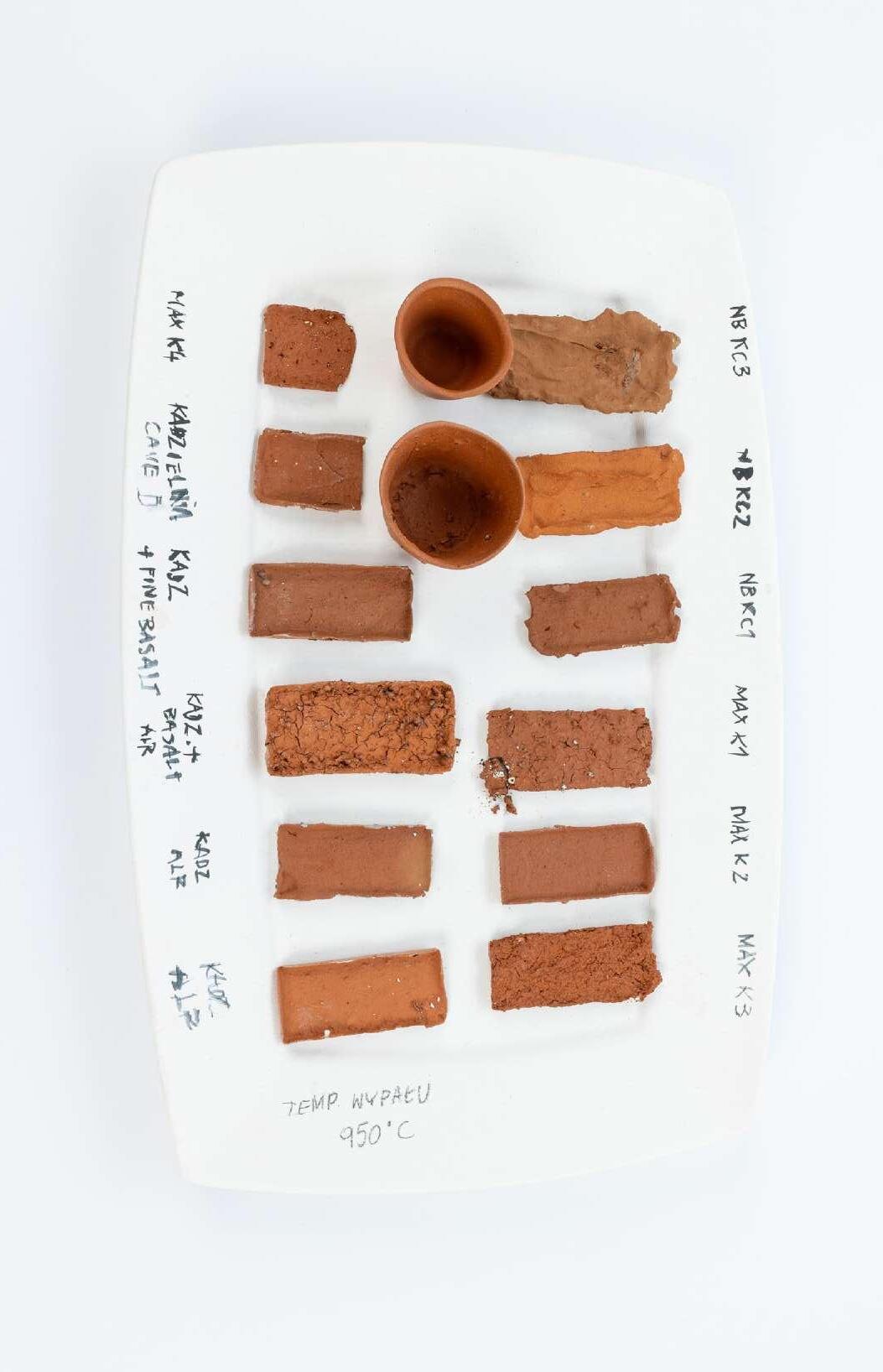

On the first day of the workshop, we visited a brick factory and brought some bricks back to the studio. By crushing them into dust and mixing the powder with water and sawdust or basalt, we created material test batches that were later fired in the kiln. Out of all the mixtures, the sample made of a combination of brick dust and sawdust had the most interesting texture and colour variation, in my opinion. The sawdust had burned away, leaving behind a lightweight structure. Next, we had the opportunity to cut shapes into a wooden board. I chose two trapezoidal forms that resembled building facades. We then placed the board into an extruder, which produced elongated, sausage-like pieces. I cut them into small cubes to resemble miniature house models. Similarly, I also attempted to form precise squares from red clay, but I found it difficult to shape them by hand. I painted some cubes with white clay that I crushed and mixed with water to achieve a paint-like texture. The cubes worked almost like puzzle pieces, inviting experimentation with various configurations and spatial arrangements.

For the base of my model, I used a clay rolling machine to create a thin, flat sheet of clay, out of which I next cut a square. By pressing pearls into the clay, I created a street-like pattern, which inspired me to arrange my small stair-house models on top, forming a miniature cityscape. Once I had finished painting and refining the models, I also experimented with decorating plates made of leftover samples from other processes with the same pattern using clay slip. I would have liked more time to develop my ideas further, but since everything was quite new to me, my focus remained on experimentation rather than a finalized outcome. From this workshop, I gained a lot of inspiration and a new perspective on material use in architecture, both in model making and in real life.

Áslaug Lára is a first-year architecture student at the Iceland University of the Arts. She previously studied at Skolen for Arkitektur in Copenhagen. Her journey in the arts began at the Art School of Kópavogur, where she has been a student since the age of six. Primarily focused on watercolor painting, she has also explored ceramics through various courses. Her strong background in fine arts significantly influences her approach to architecture and design, bringing a thoughtful, artistic perspective to spatial thinking and creative processes.

During the workshop week, I thought a lot about the forces of nature and how they shape and influence human design. Coming from a graphic design background, I didn’t have much experience with media other than paper and ink. Although to an outsider these materials might seem pretty basic, there are so many choices you can make with them. Those choices affect your design and may even have more influence on the outcome than the initial idea. As designers, we often like to think that we are in control of what we make but the materials we choose don’t always behave the way we want them to. Paper might crinkle or crumble, make strange sounds when touched, become see-through, fade in the sun or get brown with age. The same applies to any other material. This was very much the focus of my project. I ended up with a couple of different items that might look like they don’t make much sense together, either visually or functionally, but my aim was to tell a story. I started out using the extrusion machine to make a gutter. I chose to keep it the way it came out, and not fix any cracks or holes, as it reminded me of old and weathered gutters. Gutters are objects designed to control the way natural phenomena impact our buildings, to protect our infrastructure from the rain, but they too become affected by nature. Following that, I sculpted a tongue—a body part which we use for drinking. This element serves as a reference to the gutter, which—just as a tongue— is used for directing the flow of water, but also to tools, understood broadly as helpers for controlling nature. My final objects were a series of tiles painted with a mix of clay from the Kadzielnia cave and porcelain. The patterns I drew reference my earlier project on the domestication of nature, and illustrate exactly that—how we control nature but also how nature controls us and our design.

Didda is an Icelandic/Norwegian designer and illustrator. She graduated with a bachelor in graphic design from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam in 2022, and has since been working on projects of various media , such as illustration, animation, graphic design, writing and radio. Didda is interested in experimental narratives, exploring topics around the relations between the internet, body, identity, as well as ownership and domestication of wilderness and the home.

A particular value of the workshop was the opportunity to work experimentally with the material— without the pressure of achieving a final result or the need to create a finished project. A process full of trials, errors, and observations allowed me to get to know clay not only as a raw material but as a key element of the creative process. My activities—from pounding the clay to creating glazes—were based on testing the proportions, possibilities, and limitations of the material. For me, as a designer accustomed to working within clearly defined project frameworks, it was a valuable change. The diversity of the knowledge shared—both theoretical and practical—greatly enriched the experience. Meanwhile, the encounter between Polish and Icelandic perspectives showed that clay can become a universal point of reference, revealing surprising similarities between seemingly distant traditions.

Wood as a Building Material

Wood has been used as a building material since prehistorical times. Its accessibility and ubiquity in virtually every corner of the Earth make it universal across cultures. Regardless of their geographical location, various communities found in wood the very characteristics that were necessary to create structures able to withstand their local conditions. The properties of wood are versatile enough to allow for the construction of buildings of varying scale—from simple sheds and small houses, through mansions, to impressive temples and ships with complex geometry.

The versatility of wood is reflected in the variety of its applications as a building material—it is used to create structural elements such as beams, posts, purlins and rafters, flooring components such as planks and laths, wall cladding elements such as boards and shingles, and interior finishes such as wainscoting and coffers. The inherent plasticity of wood allows for its use in creating beautiful architectural details—wimpergs, consoles and traceries—which give wooden architecture a unique ambiance, difficult to replicate in other building techniques.

The lightness and durability of wood make it a material suitable for construction in almost any conditions, without the need for heavy equipment. Large span structures can be achieved through an appropriate composition of small and light elements, creating extraordinary sculptural forms.

An undisputed advantage of wood is its influence on the senses. Wood can be experienced through its colour, smell and tactile quality. The material exudes warmth that cannot be found in finishes such as hard stoneware, flat plaster or artificial composite. The inimitable colour and grain of natural wood—from the warm and bright spruce, through the brown shades of walnut and oak, to black wenge and red tropical cabreuva—have inspired designers for centuries.

Correctly sealed and maintained, a wooden building can survive hundreds of years, showcasing the beauty of the material refined by time. Wooden structures owe their longevity in part to the ease of repair through localised replacement of building components. As wood is an organic material, the replaced elements preserve their original features and parameters without impacting the reception of the building as a whole.

The artisanal or even artistic knowledge of the material allows for efficient interventions in existing structures, not limited to those made of timber. A reconstruction or expansion of a building may seem like a straightforward undertaking, but it is the ease of processing characteristic of wood that makes it possible. Another unique quality of timber buildings is the possibility to dismantle them into separate parts (structural and other) and later move and reassemble them elsewhere. The ability to transport old buildings into new locations makes it possible to safeguard the singular features of vernacular architecture even if there is no economic justification for their preservation in their place of origin.

Despite their overall good technical condition, some old wooden elements might not be up to standard (e.g. due to changes in fire safety regulations). However, owing to the universality of

Krystian Patyna

wood, every building and each of its parts can be treated as a material stock, possible to reuse in a different place and for a different purpose. Wooden ceilings that do not meet the present rigorous requirements for fire-resistance certification can be transformed into elements of interior decoration or street furniture. Thus, historical and contemporary wooden architecture fulfils the current objectives of the closed-circuit economy based on the reduction of construction waste, reuse of existing elements and materials, as well as repurposing of used building components.

Current technologies utilised in the timber industry increase the potential and applicability of wood. Contemporary wooden architecture offers both new reinterpretations of the traditional craft and state of the art building techniques which enhance durability and stability, and therefore the possible span and scale of timber structures. Technologies such as cross-laminated timber and glued-laminated timber enable us to build structures of unusual form or sizes rarely seen outside of bridge engineering. They are a testament to the beauty of wood while at the same time allowing for the manufacturing of highly demanding building components, such as beams, slabs or roof structures, offering a better alternative to materials such as concrete and steel.

The ability to successfully manufacture prefabricated building components or entire modules had a substantial influence on the development of the timber construction industry. In contrast to concrete and steel, processing wood does not require largescale technological and production facilities. In addition, the lightness of the material and the simplicity of assembly, reminiscent of traditional methods, facilitate the construction of wooden buildings in places that are difficult to reach (e.g. due to limitations in road freight).

Wood is a perfect material to be used in hybrid with other technologies, as proved in various projects by master architects. Mixing austere concrete and warm wood creates an interesting visual contrast; slender wooden elements can be beautifully integrated into large glass panes. When skilfully combined with steel, wood can improve its parameters, and pairing wood with concrete can reduce the required volume of the material.

The unique and natural characteristics of wood, its lightness and durability, warmth and ease of processing, as well as the exceptional atmosphere it creates in a space, render it a universally appealing, and therefore timeless material.

Natalia Skiepko

National Heritage Institute Center of Wooden Architecture in Zakopane

Historic wooden buildings serve as a testament to craftsmanship expertise perfected over centuries and passed down from generation to generation. Time-honored solutions—such as roof shape, slope angle, eave width, the orientation of the façade in relation to cardinal directions, and construction materials sourced from natural local resources—were all designed to ensure maximum adaptation to regional climatic and geographic conditions while also enhancing the daily lives of residents. These structures, rich in their simplicity, functional solutions, and use of natural, locally sourced materials, often feature remarkable architectural details. Today, they represent not only a valuable repository of ancient building practices but also an enduring source of inspiration for contemporary green and passive architecture—in terms of form, technology, and materials.

The borders of our country fluctuated over the centuries, which resulted in a diverse and rich heritage of vernacular wooden architecture. Today, depending on a region’s historical affiliation, we can identify the cultural identity of specific geographic areas based on typological classification. The diversity of function, construction, and style holds immense historical significance, enriching the landscape and showcasing the achievements of past generations, different nationalities, cultures, and religious traditions. It is easy to observe that the northern, western, and southwestern areas abound in timber-frame structures, distinguished by their choice of infill materials. These generally include post-and-beam structures with brick infill, as well as wattle and daub constructions, where spaces between the wooden framework are filled with clay mixed with chaff or wood shavings, cast onto a wooden lattice. The so-called Upper Lusatian houses, found particularly in Lower Silesia, are both monumental and refined, blending timber-frame and log construction—the latter of which dominated the southern and eastern regions.

Equally extraordinary are the arcaded houses—Olender homesteads located mainly in the Żuławy region in the north of the country. Meanwhile, central Poland is characterized by post-andplank and timber-frame structures, where the structural frame is concealed by wooden exterior cladding, often adorned with intricate wooden architectural details. The interiors, on the other hand, are typically finished with lime plaster applied over reeds, while the spaces between walls are insulated with sawdust or conifer needles. This construction style became particularly associated with health and summer resorts, which flourished in spa towns at the end of the 19th century.

And yet, even among such a wide variety of wooden construction techniques, there remains room for truly unique examples, such as timber-frame and wattle structures, where the spaces between posts are filled with woven wickerwork, as well as unconventional buildings constructed from stacked firewood logs. Wooden architecture within the territory of present-day Poland can also be categorized based on the function of individual structures, which—like their construction methods—exhibit remarkable diversity. In addition to the predominantly residential

function (whether rural, urban, or manor houses), there are also agricultural buildings, such as barns, stables, and sheds, as well as storage facilities, including granaries and cellars. Furthermore, wooden architecture includes social infrastructure, such as schools, boarding houses, and sanatoriums. Finally, wooden industrial structures, such as mills, windmills, oil mills, and breweries, also form a valuable architectural category. A separate group is formed by religious buildings. Owing to Poland’s complex history, the country is characterized by a wide variety of architectural forms, each adapted to accommodate the liturgical practices of different denominations. In the urban landscape, various religious structures can be observed, including Catholic, Orthodox, and Evangelical churches, as well as Jewish synagogues.

Despite the diversity and richness of wooden architecture, an accelerating process of degradation and disappearance of these structures from the landscape has become evident in recent years. A comprehensive study of this phenomenon was conducted through a nationwide field survey of wooden architecture, carried out by the National Heritage Institute in 2022. The results of this analysis—including summaries, conclusions, and guidelines—were compiled and submitted in the document titled Raport o stanie architektury drewnianej w Polsce (Report on the State of Wooden Architecture in Poland)1

According to the report and on-site visits, several factors contribute to the degradation of wooden architecture, with time being the common denominator. Wood is a biodegradable material, and without regular maintenance, proper insulation from moisture, and timely conservation efforts, it deteriorates rapidly. An abandoned wooden building can fall into disrepair within just a few years or, at best, a couple of decades. Changing tastes, shifting aesthetic preferences, and the evolving lifestyles of those who once inhabited the most distinguished wooden homes often lead to the perception that such buildings are outdated or impractical. This, in turn, fuels the desire to replace them with modern, comfortable, and typically brick-built structures, inspired by cosmopolitan architectural trends. The intensified construction boom of recent decades is one of the most alarming threats to historic wooden architecture and has accelerated its phasing out. It is worth noting that concerns about the disappearance of wooden architecture were already raised at the end of the 19th century. This growing threat sparked an increased interest in vernacular culture and a fascination with folklore. Moreover, the search for national identity and a reaction against industrialization led 19th-century researchers to turn to indigenous roots and traditional craftsmanship, including rural wooden structures. Materials, craftsmanship, construction techniques, and decorative elements— once characteristic of peasant homes—were gradually assimilated, creatively reinterpreted, and elevated to the status of architecture. A newfound awareness of the value of vernacular buildings laid the groundwork for early preservation initiatives. The first efforts were made to study and document folk structures, leading to the

creation of ethnographic collections and the emergence of initial concepts for their protection2

In Poland, the first legal act regulating the protection of monuments—including wooden architecture, elements of interior decoration, and folk handicrafts—was the Dekret Rady Regencyjnej o opiece nad zabytkami sztuki i kultury (Regency Council’s Decree on the Care of Monuments of Art and Culture), issued in 19183

The importance of protecting Polish wooden and vernacular architecture was the focus of extensive discussions during the Second National Congress of Conservators, held in Warsaw in 19274. The key priorities established during the congress included compiling an inventory of wooden architectural monuments, developing the concept of open-air museums in Poland, implementing educational and outreach initiatives to raise awareness of the cultural and historical value of these structures, and establishing a specialized archive that would also function as an independent research institute dedicated to Polish wooden architecture. A tangible outcome of these deliberations was the intensification of fieldwork related to documenting wooden architecture and the initiation of procedures to include valuable examples in the register of monuments. A notable example of such efforts was the topographic inventory conducted in 1938 in the Nowy Targ district, in southern Poland. Although wooden churches constituted the majority of protected structures, the inventory also included vernacular architecture, such as Anna Dorula’s 1843 cottage in the town of Szaflary5. Another example of a protected secular structure is the “Pod Jedlami” Villa in Zakopane, designed by Stanisław Witkiewicz in 1897 and designated as a monument as early as 1931. The development of wooden architecture in the Podhale region serves as a perfect example of the transformation of vernacular building traditions into a distinct architectural style—called the Zakopane style. This style is not only a defining feature of the region but also is continuously practiced and developed in the contemporary architecture of the Podhale region.

Currently, an important direction of action that not only helps secure historic wooden architecture but also paves the way for the development of modern wooden construction is the growing engagement of various entities in the dialogue on the future of this heritage. In particular, emphasis should be placed on the education of future engineers and architects, starting at the high school level and continuing through university. Raising awareness of the value of historic and vernacular architecture creates opportunities for creative regional design that blends harmoniously into the cultural landscape of local communities. An additional valuable approach is training in traditional carpentry techniques and the use of ecological materials for house construction. Beyond state institutions organizing such programs, private initiatives also play a key role, often gathering large audiences through contemporary social media platforms. When working with wooden architecture— whether historic or modern—it is essential to base all design and construction work on a deep understanding of past building techniques, particularly traditional craftsmanship. The construction

methods preserved in historic wooden buildings are the result of centuries of refinement: they are natural, biodegradable, virtually zero-emission, and above all, beneficial to human well-being and health. By cultivating these skills and traditions, we can continue to create both contemporary and regionally inspired wooden architecture that seamlessly integrates into the cultural landscape.

The work of pioneers in the preservation of wooden architecture has played a crucial role in ensuring its survival, allowing us today to continue engaging with traditional wooden structures and drawing inspiration from their historical formal, functional, technological, and material solutions. Historic wooden architecture, including vernacular buildings, is an irreplaceable resource. If we allow it to disappear today, it will be impossible to restore. Therefore, all efforts aimed at promoting traditional building practices and raising awareness of the value of wooden architecture—not only in the context of heritage conservation but also in terms of its positive impact on the environment and its role in mitigating modern climate change—are highly desirable.

It is important to recognize that renovating a historic building using traditional craftsmanship methods contributes to energy conservation, reduces environmental impact, and makes use of the existing carbon footprint rather than generating a new one. The potential of historic wooden architecture should be embraced—not only for its authentic atmosphere and unique character but also as a valuable cultural asset that enhances the identity of a place. Likewise, contemporary wooden architecture, when designed ecologically and rooted in traditional techniques, can become a source of pride for local communities and a significant landmark on the cultural map. The modern world promotes a healthy lifestyle oriented toward nature and tradition—values beautifully reflected in wooden architecture.

Polish wooden architecture is a rich and diverse tapestry of forms and styles. Alongside rustic shepherd’s huts and vernacular cottages, one can find elegant villas, spa architecture, striking modernist designs, exotic Far Eastern pavilions, and contemporary structures that fully embrace the legacy of past generations. A subjective guide to these wooden landmarks, precious not only for their emotional significance but also as a vivid testament to Poland’s diverse history, would reveal a collection of structures as colorful and varied as the country itself.

REFERENCES

“II-gi Ogólnopolski Zjazd Konserwatorów w Warszawie w 1927r. (Uchwały i rezultaty)”, Ochrona zabytków sztuki, vol. 2, no. 1-4, ed. by J. Remer, Warsaw 1930-1931. M. Bogdanowska, N. Skiepko, ‘Najdawniejsza, najpierwotniejsza i najpiękniejsza’ – sztuka ciesielska – misja i działalność Centrum Architektury Drewnianej Narodowego Instytutu Dziedzictwa, ANTIKON 2023. Architektura ryglowa – wspólne dziedzictwo, ed. by B. Marszalik, A. Szarlik, Warsaw 2024. J. Czajkowski, Dom drewniany w Polsce. Tysiąc lat historii, Krakow 2011. Dekret Rady Regencyjnej o opiece nad zabytkami sztuki i kultury, Journal of Laws, 1918 no. 16, item 36, available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/ DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19180160036 (accessed: 18 February 2025). R. Dethlefsen, Bauernhäuser und Holzkirchen in Ostpreußen, Berlin: 1911. Z. Gloger, Budownictwo drzewne i wyroby z drzewa w dawnej Polsce, Warsaw 1907.

F. Kopkowicz, Ciesielstwo Polskie, Warsaw 1958.

L. de Puget-Puszet, Studya nad polskiem budownictwem drewnianem, Cz. 1: Chata, Krakow 1903.

W. Matlakowski, Budownictwo ludowe na Podhalu, Krakow 1892. K. Mokłowski, Sztuka ludowa w Polsce, Lviv 1903. Raport o stanie architektury drewnianej w Polsce, ed. by M. Bogdanowska, K. Zalasińska, Warsaw 2023.

Remont i utrzymanie domu drewnianego – najkrótsza instrukcja obsługi, ed. by M. Wierzchoś, Warsaw 2023.

G. Ruszczyk, Drewno i architektura. Dzieje budownictwa drewnianego w Polsce, Warsaw 2014.

B. Schmid, Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler des Kreises Marienburg, Danzig 1911. N. Skiepko, Budownictwo ludowe, [in:] „Kultura ludowa górali podhalańskich”, ed. by K. Ceklarz, M. Kwiecińska, Krakow 2024, vol. I pp. 283-354. J. Tajchman, “W sprawie konieczności ustanowienia standardów wykonywania projektów dotyczących prac planowanych w zabytkach architektury”, Wiadomości konserwatorskie, 24/2008, pp. 17-47.

I. Tłoczek, Polskie budownictwo drewniane, Wrocław 1980.

Zabytki sztuki w Polsce: inwentarz topograficzny, Cz. III: województwo krakowskie. T. I, zeszyt 1: powiat nowotarski, ed. T. Szydłowski, Warsaw 1938. J.S. Zubrzycki, Cieślictwo Polskie, Lviv 1930.

Fot. Jakub Certowicz

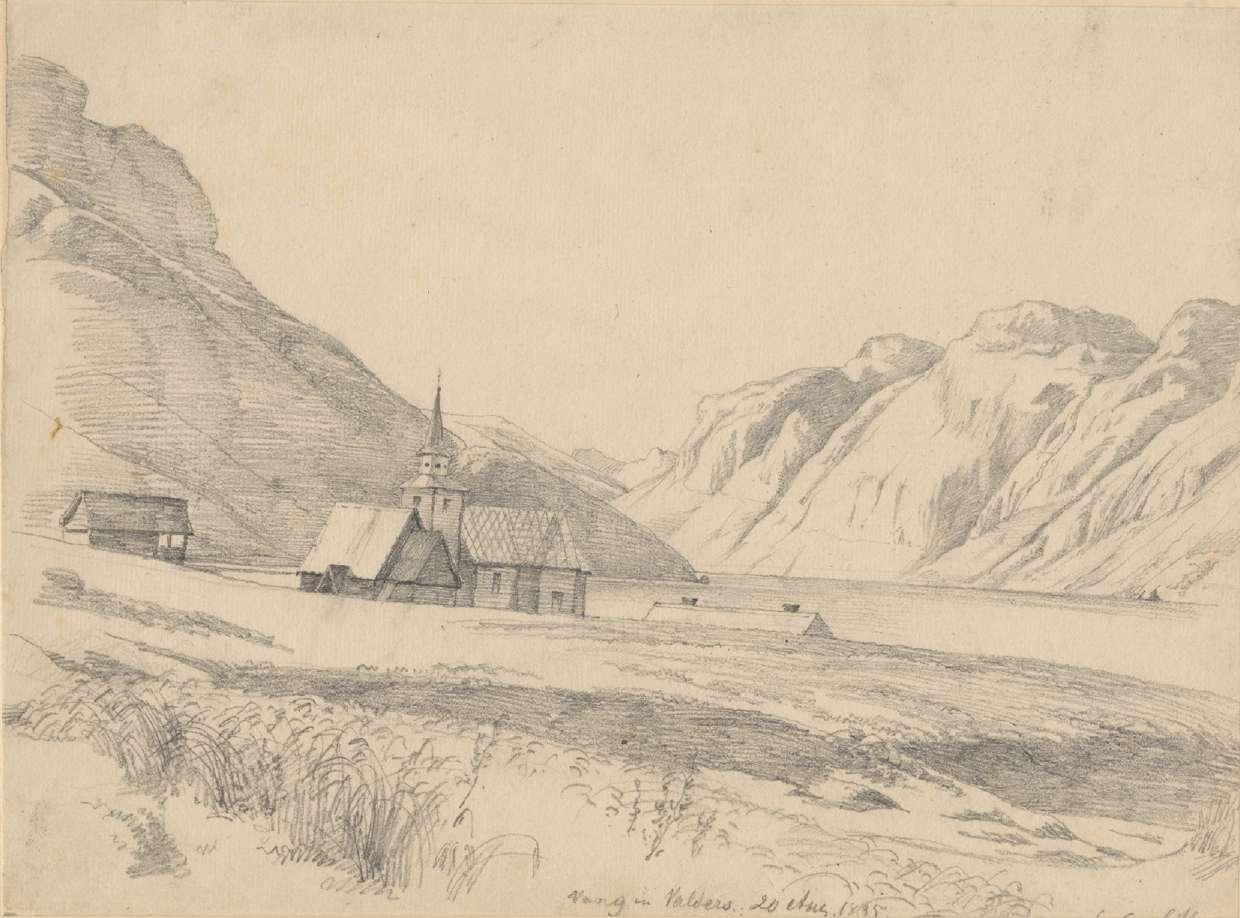

In a mountain village in Poland, there is a medieval church that originates from the Valdres highlands in Norway.6 Through the nearly two centuries since it was sold and exported, this church has haunted Norwegian history in different ways, often as a tale of woeful ignorant ancestors. In the 19th century, Norway went through what can be considered a stave church massacre. These traditional churches were often deemed too small, too impractical, too primitive, too heathen; certainly not a heritage to be cherished. It is believed that more than 1000 such churches were built during the Middle Ages in Norway. Today only 28 remain. And then there is one in Poland. Out of all the lost stave churches, the one that was saved because it left the country may be the one whose loss hurt the most.

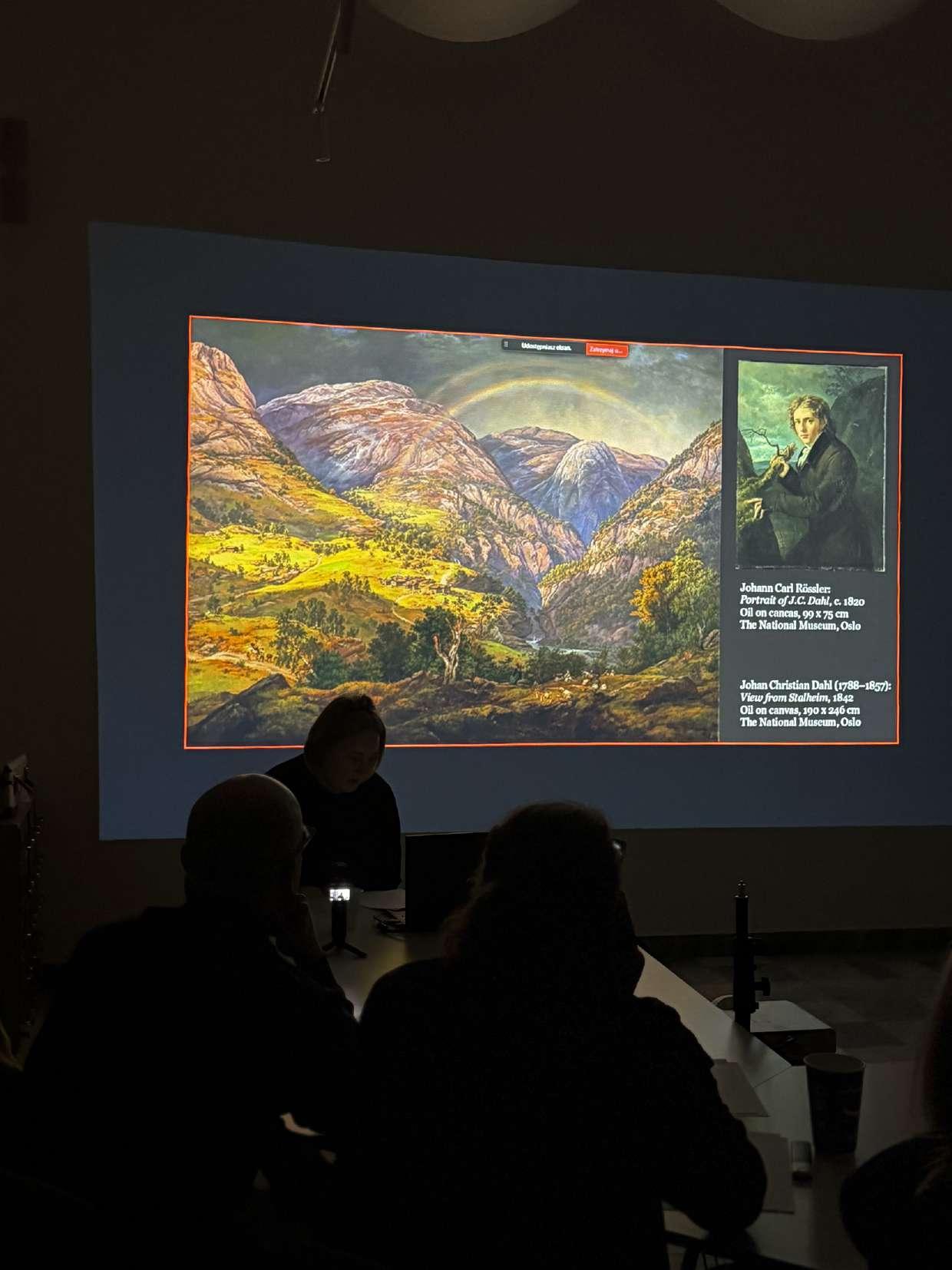

The main instigator for raising the status of the stave churches was the artist and scholar Johan Christian Dahl (1778–1857). Dahl was a Norwegian-born professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden. During his travels in Norway, Dahl realised that stave churches were torn down left and right and decided to intervene. In 1837 he published the illustrated book titled Denkmale einer sehr ausgebildeten Holzbaukunst aus den frühesten Jahrhunderten in den innern Landschaften Norwegens [Monuments of a highly developed wooden architecture from the earliest centuries in the inner landscapes of Norway]. The plates were based on surveys conducted by Dahl’s former student, architect and painter Franz Wilhelm Schiertz (1813–1887).

Denkmale increased awareness of the stave churches throughout Europe, although not only as examples of Norwegian architecture. In later scholarly writing, these churches were seen as a purely Norwegian architectural phenomenon, but Dahl emphasised that various elements of the stave churches were linked to different international historical styles.7 Rather than being seen as an expression of a distinctive national style, the churches were viewed as part of global cultural history. In Dahl’s eyes, this was what made them significant.8

Denkmale was reviewed in prominent journals of the time, and stave churches quickly gained appreciation across Europe. The book made an impact, but on the continent its message resonated more quickly than in Norway. As early as 1842, Franz Kugler’s pioneering art history survey described stave churches as unique artifacts, recently recognized thanks to Denkmale. 9 A mere year before Kugler’s work established stave churches as part of the architectural canon, the old church in Vang was auctioned off. Dahl had been aware of the church being in peril for many years. When travelling through the village of Vang in 1839, he observed that a ridge turret and ambulatory that he had seen on previous journeys, were already dismantled; however, the evocative and enigmatic carvings on the portals and vivid paintings in the choir remained. He made several unsuccessful attempts to preserve what was left of the stave church. His most crushing defeat, perhaps, was the failed effort to relocate the church to the Palace Park in the capital. Dahl believed this location would have

Bente Aass Solbakken

been ideal, particularly as the church could have become a point of reference for contemporary architects.

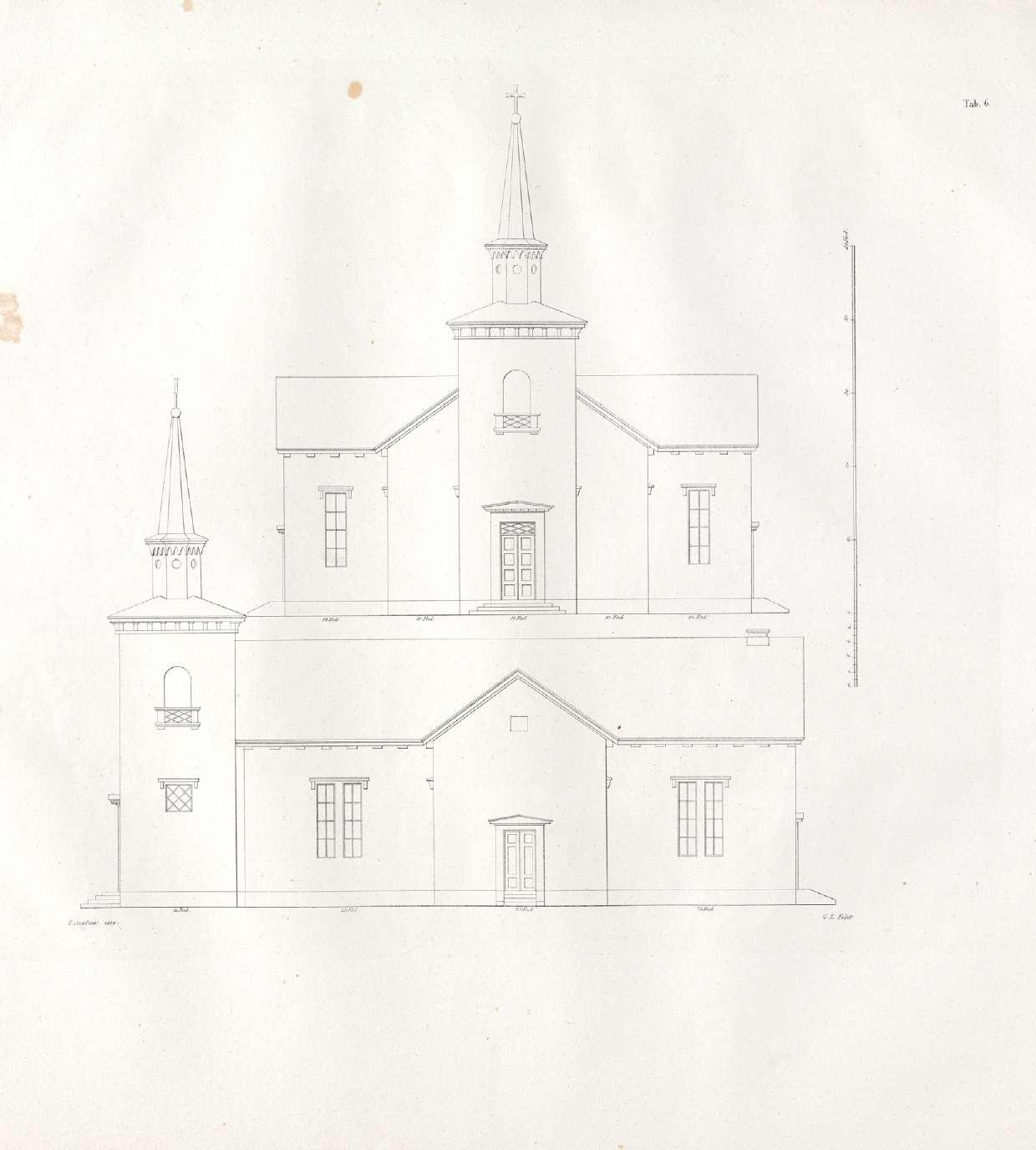

The ramshackle church was stripped of its earlier grand appearance. A new, larger church was constructed; its tower loomed ominously right behind (FIG. 1). Dahl found the new structure and the demolition of the old church equally horrifying. The replacement was built according to a standardised neoclassical design by Hans Ditlef Linstow (1787–1851) (FIG. 2–3). Dahl sneered at these designs, which he referred to as Linstow’s ‘sheds’, and complained that the classicist influence of art academies had corrupted an entire generation of architects and made them indifferent to everything not Greek.10 Linstow was also the architect of the Royal Palace and responsible for the failed relocation of the stave church to the Palace Park.

The disagreement between Linstow and Dahl reflects an ongoing intellectual paradigm shift, driven by the historicist philosophy which argued that culture was the product of a given time and place. Consequently, medieval heritage across Northern Europe gained new significance as a form of national expression, while Greek and Roman antiquity lost its pre-eminent status as universal. Linstow himself acknowledged this trend. He observed that the medieval and romantic had overtaken ‘the ancient style,’ and explained that while fascination with the medieval was recent, his own devotion to Winckelmann kept him from surrendering to romanticism.11 Linstow’s classicist orientation explains why he was resolutely opposed to Dahl’s suggestion of the Vang Stave Church as a chapel in the Palace Park. For his part, Dahl believed that the church would have enhanced the city and served as both a memorial and, not least, a model for new churches and contemporary architecture.12

The architectural nationalism of the 19th century would soon overlay Dahl’s understanding of the stave churches as global heritage and supplement it with a reading of stave churches as unique expressions of national genius. However, in 1841 the perception of the stave churches as primitive, heathen, and impractical still prevailed in Norway. As already mentioned, Dahl fought to save the Vang church by having it relocated within Norway but ultimately failed. The stave church was auctioned in January 1841, with a strict deadline for removal by the end of the year. Dahl (with the priest as his agent) made the winning bid, but he did not buy it on his own behalf. Some months before the auction started, Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia (1795–1861) was briefed on the situation and decided to purchase the church and relocate it to Prussia.13 The king took great interest in architecture and most likely knew of stave churches through Denkmale. What the congregation in Vang sold, and what Friedrich Wilhelm IV bought were really two different things. The auctioned church was something impractical and outdated, while the purchase was a piece of the world’s cultural history.

Before the church could be shipped to its new home country, it had to be documented, dismantled, and packed. Schiertz was sent to Norway for the second time, acting on Dahl’s in-

FIG. 1 Louis Gurlitt (1812–1867): Vang in Valdres, 1835. Pencil. The Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

FIG. 2 G.L. Fehr (1800–1855) after drawing by Hans D.F. Linstow (1787–1851): Design for a Countryside Church, 1829. Lithography, 528 × 592 mm. The National Museum. Plate 6 in Udkast til Kirkebygninger paa Landet i Norge, Veiledning for de Kirke-Eiere, som uden Architects Hjelp ville opføre Kirker hensigtsmæssigen og med Oeconomie [Designs for Countryside Church Buildings in Norway, Guidance for building Churches appropriately and economically without the aid of an Architect].

FIG. 3 Marthinius Skøyen (1849–1916): Vang Church in Valdres, 1898. Collotype, 224 × 281 mm. The National Museum.

structions. He was tasked with producing survey drawings and overseeing the dismantling and packing process. Transporting the church to continental Europe was taxing. The parts were hauled by wagons and packhorses over the mountain to Lærdal, at the head of the long Sognefjord. In a letter dated 31. August 1841 Schiertz wrote to Dahl that the church was loaded onto a galleon that would take it away, and claimed that its total weight amounted to 450 tons.14 After barely sailing south of Stavanger, the galleon had to seek shelter from stormy headwinds. A local newspaper noted, matter-of-factly, that one of the vessels weathering the storm was the Hope, ‘destined for Stettin with a dismantled old wooden church from Valders.’15 The bad weather continued, and they also suffered a grounding before finally reaching Stettin (today’s Szczecin). There, the church was once more reloaded, this time onto a riverboat, and shipped to Berlin.

When national newspapers reported on the royal purchase, the tone was deferential. The double authority of Professor Dahl and the Prussian King made for a sudden acknowledgement of the Vang Church’s value. Regret was already forming, mixed with a certain pride, as some claimed the church would be erected in Pfaueninsel, while others suggested Sanssouci in Potsdam.16 It would have been a promotion of Norwegian spirit in the heart of Europe:

These old logs, what stories they could tell the refined Berliner, if they could speak; tales both light and dark, from Haakon the Good’s period, through the degrading autocracy to Norway’s new age of freedom! What lessons they could offer the deserving descendant of old Fritz! At least, amidst the speckled crowd of the civilised world, they would remind the countless art-loving strangers that will flock to this ancient, doubly sacred building, of our Norway; and show the dumbfounded Parisian that old Thule wasn’t only ever inhabited by bears and wolves.17

In April 1842 the church had finally reached Berlin. A Bergen newspaper expressed grief: ‘Though it may cause one great sorrow to witness this significant monument of our forefathers’ architectural skill … be forever removed from us, it is nonetheless a satisfaction to know that it has fallen into good hands and has garnered the admiration abroad that it has, for many years, lacked at home.’ Dahl is supposed to have said about letting the church be sold out of the country, that he was tired of peddling it like stale beer.18 The beer was no longer stale though, thanks to the church’s royal acquisition and European scholarly praise.19

A Norwegian newspaper maintained its coverage of the church’s journey. In February 1842, it was reported that the King expressed great delight at the church’s arrival in Berlin. So much, that he rewarded the captain of the galleon Hope with 50 taler and gifted the same amount to Schierzt for ‘the excellent execution of his drawings of the admirable carvings’.20 Less cheering news was to follow though. Just a few months later it was reported that the church was now destined for Silesia. While this was a snub, the

newspaper sought to comfort its readers by asserting that the old church would ‘find a more dignified setting among the spruces of the Giant Mountains than within the modern arrangements of its former prospective site, situated amidst menageries, palm houses, and Chinese towers.’21

While the church was stored in Berlin—supposedly in the courtyard of the Altes Museum – the King had somehow lost interest. It is not known why he had a change of heart, but the church was sailed further down the Oder to the Giant Mountains where it was dragged and pulled upwards to the mountain village of Brückenberg (then in Prussia, later Germany, today Karpacz in Poland). Lower Silesia was the summer playground of the King and nobility, the countryside peppered with mansions and castles. The King himself held court at Fischbach Castle (today Karpniki) while Countess Friederike von Reden (1774–1854) owned the neighbouring Buchwald estate. She was a philanthropist and is credited with having persuaded the King to place the Vang Church in Brückenberg (about 20 kilometres from their estates) where a small local Protestant congregation had to travel a great distance to their church at the time. Despite all Reden’s good work, she is not remembered much today, save for a memorial that sits beside the Vang church. Designed in a strict classicist style, it stands out among all other monuments, tombstones and signage around the church, whose surroundings were seemingly influenced by the distinct, contagious style of the architecture and its ornaments.

The most thorough investigation of the Vang church, its journey, and reconstruction was conducted by antiquarian Arno Berg. He recounts a story of how Schiertz discovered a mummified woman’s body below the altar while dismantling the church in Norway. Dahl was informed of the event and speculated that the body could be Gyda Eiriksdotter (around 900).22 According to legend, Gyda told her suitor Harald Fairhair that she would accept him only if he united Norway into one kingdom, which spurred him to do so. Intriguingly though, in 1842 it was claimed that this body was found in Brükenberg: ‘When the church was reassembled, reports from the site indicated that a well-preserved, mummified body of a woman was found in the altar’.23 If this is true, it means the church was holding the body through a staggering and demanding journey across northern Europe. Another mystery is the interior paintings in the choir. Schiertz’s drawings of the panels have convinced scholars that they represented some of the finest examples of medieval painting in Norway (FIG. 4). However, they have since disappeared. The paintings were, naturally, very Catholic; in 1807, during a (Protestant) bishop’s visitation, they were described as reeking of superstition and indecency.24 They were probably not deemed fit for a Protestant congregation in 1841 either, so they remained in Berlin. For a long time, there was a rumour that they had been left in the Altes Museum, but no-one has ever been able to find them either there or elsewhere.

Throughout history, wild tales have been told of this church and how it came to leave its home country. It was once claimed that the stave church stands 2500 meters above sea level,

FIG. 4 Franz Wilhelm Schiertz (1813–1887): From the choir in Vang Church, 1841. Copy by Johan Meyer, 1893. The Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

FIG. 5 Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857): The Church in Vang, 1843. Brush and wash, 64 × 95 mm.

Photo: Kode Bergen / Dag Fosse.

just below the Schneekoppe (Śnieżka).25 However, the mountain is only 1603 meters high. The fate of the church has been described as tragic and heartbreaking, as a source of grief for the entire Norwegian people. In the summer of 1929, a memorial stone was erected in Vang to commemorate a local resident who strove in vain to retain the church within the village. He suggested moving the church to the eastern side of the Vangsmjøse lake, even offering land free of charge for this purpose.26 After the end of the Nazi occupation during the Second World War, the repatriation of the church was high on the national agenda. That this treasure had been abducted was one thing to handle, but that it was currently standing on German soil was unbearable. Norwegian antiquarians did not support claims to demand the church back though and reminded people that the building had been sold, not taken.27 ‘Unfathomable to the people of our age,’ a newspaper quipped, ‘but such were the times—poor in both material and spiritual sense.’28

Today, the Vang church is experiencing great success as a literary sensation. The epic trilogy The Sister Bells by Lars Mytting features an old church in the fictional village of Butangen. When a German architect suddenly appears in the village to facilitate the relocation of the church to Dresden, a chain of improbable events is set in motion. The books have reawakened the stories of Vang, and the church is now more famous than ever. In its literary version, the church burns down, but its model remains in Karpacz, albeit with an appearance that is somewhat uncanny for a Norwegian.

The new church in Vang is no longer new, and its status is rather that of an inadequate replacement. A disturbing tombstone-like memorial by the graveyard is inscribed: ‘Vang Stave Church stood here ca. 1180–1841.’ The new classicist structure harbours the ghost of its predecessor through a substantial model of the Vang church as it appears in Karpacz.

It seems Dahl had the church on his mind, on his retina for a long, long time. He made several depictions and fantasies on paper and canvas. A small, haunting sketch of the Vang church at its lakeside site in Valdres depicts the church as a ghostly mirage (FIG. 5). When Dahl made this drawing in 1843, the church had long since been dismantled and schlepped through northern Europe. The drawing shows how the church continues to linger by the lake even though it is gone.

REFERENCES

1 Raport o stanie architektury drewnianej w Polsce, ed. by M. Bogdanowska, K. Zalasinska, Warsaw: National Heritage Institute, 2023.

2 For example: W. Matlakowski, Budownictwo ludowe na Podhalu, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1892; L. de Puget-Puszet, Studya nad polskiem budownictwem drewnianem, Cz. 1: Chata, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1903; K. Mokłowski, Sztuka ludowa w Polsce, Lviv: nakł. Księgarni H. Altenberga, 1903; Z. Gloger, Budownictwo drzewne i wyroby z drzew w dawnej Polsce, Warsaw: [s.n.], 1907; R. Dethlefsen, Bauernhäuser und Holzkirchen in Ostpreußen, Berlin: Verlegt bei Ernst Wasmuth, 1911; B. Schmid, Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler des Kreises Marienburg, Danzig: Kommissions-Verlag von A. W. Kafemann, 1911. 3 Dekret Rady Regencyjnej o opiece nad zabytkami sztuki i kultury, Journal of Laws, 1918, no. 16, item 36, available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap. nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19180160036 (accessed: 18 Februrary 2025).

4 “II-gi Ogólnopolski Zjazd Konserwatorów w Warszawie w 1927r. (Uchwały i rezultaty)” [Second National Congress of Conservators in Warsaw in 1927. (Resolutions and Results)], Ochrona zabytków sztuki, vol. 2, no. 1-4, ed. by J. Remer, Warsaw 1930-1931. 5 Zabytki sztuki w Polsce: inwentarz topograficzny. Cz. III: województwo krakowskie. T. I, zeszyt. 1: powiat nowotarski, ed. by T. Szydłowski, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Wyznań Religijnych i Oświecenia Publicznego, 1938, pp. 16-17.

6 Limited sections of this text are loosely derived from ‘A True Norwegian Style,’ in: Dragons and Logs, ed. by B. Aass Solbakken, (Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet, 2024).

7 See for example: L. Dietrichson, H. Munthe, Die Holzbaukunst Norwegens in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Berlin: Schuster & Bufleb, 1893.

8 S. Halkjelsvik Bjordal, ‘The Circulating Stave Churches of J.C. Dahl,‘ in: Dragons and Logs, ed. by B. Aass Solbakken, Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet, 2024.

9 F. Kugler, Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte, Stuttgart: Ebner & Saubert, 1842, p. 479; Bjordal, ‘The Circulating Stave Churches of J.C. Dahl,’ p. 146.

10 Quoted in A. Aubert, Professor Dahl: et stykke av aarhundredets kunst- og kulturhistorie, Kristiania: H. Aschehoug & Co., 1893, p. 324.

11 H. D.F. Linstow, ‘Om Kongeboligen ved Christiania (Efter Meddelelse af Architecten),’ Christiania-Posten, 24 April 1849.

12 Aubert, Professor Dahl, p. 324.

13 Aubert, Professor Dahl, pp. 323–24; J. Klein, ‘Vang stavkirke reiser til Berlin,’ in: Tyskland og Skandinavia 1800–1914: Impulser og brytninger, ed. by B. Henningsen et al., Berlin: Jovis Verlagsbüro, 1997.

14 Klein, ‘Vang stavkirke reiser til Berlin,’ p. 83.

15 Tiden, 7 October, 1841.

16 Tiden, 21 May, 1841; Den Norske Rigstidende, 25 May, 1841.

17 ‘En norsk Bondekirkes romantiske Skjebne,’ Tilskueren, 29 May, 1841.

18 Aubert, Professor Dahl, p. 327.

19 For example: ‘Vangs kirke i Valders,’ Bergens Stiftstidende, 10 February, 1842.

20 ‘Vangs kirke i Valders’.

21 Bergens Stiftstidende, 21 April, 1842.

22 A. Berg, ‘Stavkyrkja frå Vang og hennar lange ferd,’ Fortidsminneforeningens årbok 134 (1980): 111; note 11.

23 Christiania Adresse-Tidende, 15 September, 1842.

24 Sigurd Christie, Ola Storsletten and Anne Marta Hoff, ‘Vang kirke,‘ in Norges kirker, https://norgeskirker.no/wiki/Vang_kirke.

25 ‘Den norske stavkirke i Tyskland,’ A-magasinet, 8 December, 1927.

26 ‘En bauta,’ Nationen, 27 June 1929.

27 ‘Stavkirke i utlendighet,’ Nationen, 7 November 1945; ‘Vang krever stavkirken tilbake fra Tyskland,’ Samhold-Velgeren, 6 February, 1947.

28 ‘En 100 års jubilant,’ Nationen, 15 December, 1945.

Organiser:

Narodowy Instytut Architektury i Urbanistyki Partners: Institute of Design in Kielce, Museum of Architecture in Wrocław, Iceland University of the Arts, Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo

Coordination: Kacper Kępiński, Dominika Janicka, Misia Siennicka

Communication:

Iga Bałchowska, Paula Dulnik, Dominik Witaszczyk, Aleksandra Zaszewska Visual identity: Katarzyna Nestorowicz

Translations: Natalia Raczkowska

Photographs:

Iga Bałchanowska, Jakub Certowicz, Paula Dulnik, Mateusz Jaskot, Dominik Witaszczyk, Aleksandra Zaszewska Workshop and event programme: Marta Dachnowska, Michał Duda, Dominika Janicka, Kacper Kępiński, Misia Siennicka Clay module – workshop participants: Wood module – experts:

Natalia Skiepko, Bente Solbakken, Joar Nango, Zofia Jaworowska, Marta Rowińska, Lech Rowiński, Michał Sikorski, Marina Bauer, Espen Folgerø, Krystian Patyna, Jan Dowgiałło, Anna Kraczkowska, Marcin Rębarz, Przemysław Błaszczak, Szymon Ciupiński Wood module – workshop participants: Zofia Gancarcyk, Omotara Adebayo, Tomasz Maśka, Aleksander Stachowski, Kasper Svendsen, Hsi-Chao Chen

‘Out of Clay and Wood. Natural Materials for Future Architecture’ is a project financed by the by the Bilateral Cooperation Fund of the EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism.

National Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning Foksal 4, 00-366 Warsaw, Poland

niaiu.pl