“It’s Medicine, Right?”

“It’s Medicine, Right?”

It is a privilege to welcome you to the third edition of PSAM Review. When we first began this publication, our vision was to create something that reflected the unique voices, perspectives, and experiences of physicians who work in the field of Addiction Medicine here in Pennsylvania. As I sit down to introduce this issue, I am struck again by how rewarding this project has become— not only because of what is published in these pages, but because of the people who help make it possible.

Working on PSAM Review is, for me, one of the most enjoyable aspects of being involved with the Pennsylvania Society of Addiction Medicine. The editorial board is made up of colleagues who bring curiosity, insight, and dedication to the process. Together, we read, discuss, and refine submissions with the shared goal of creating a publication that feels both relevant and personal. That spirit of collaboration makes the work lighter and, frankly, fun. In a field where our day-to-day practice can be heavy with responsibility, this kind of creative endeavor becomes a meaningful reminder of why we chose this profession in the first place.

I should also admit—part of the fun is the way we always seem to run right up against our deadlines. Inevitably, we find ourselves frantically pulling everything together in the final days. You would think that would be stressful, but somehow it brings out the best in us. There is a certain energy that comes with that final push, a camaraderie in knowing we are all racing to the finish line together. And despite our collective procrastination, we always seem to get it in on time. In a way, that rush has become part of the rhythm of the magazine—and part of what makes it so enjoyable.

And for full disclosure: this very Editor’s Note was submitted on the final day. I sometimes wonder if I do that on purpose—just to make sure no one has the chance to edit or critique it before it lands on the page! Perhaps procrastination is my own editorial strategy.

As an editor, one of the great privileges is watching how a simple idea evolves into a finished piece. Sometimes it begins as a personal reflection, sometimes as a clinical vignette, and sometimes as a broader commentary on the field. What makes each submission valuable is not only the expertise behind it, but also the authenticity of the writer’s voice. That authenticity is what connects us to one another, reminding us that we are more than the roles we fill or the titles we carry.

I want to emphasize something that I hope will encourage more of you to consider contributing: your submission does not need to be purely scientific. We always welcome articles that advance clinical knowledge or shed light on research, such as the article on exploring the relationship between narcolepsy and cannabis use. I

am sure everyone will be able to relate to Arielle Bivas’s story titled “Holding Discomfort” describing the overlap of palliative care and addiction medicine, reminding us that every patient has the right to make decisions even if those decisions don’t match our hopes. But PSAM Review is also a place where members can showcase the many other aspects of their lives. We are not just physicians—we are runners, gardeners, musicians, writers, parents, travelers, photographers, and dreamers. In this issue, you’ll find a few of Olapeju Simoyan’s beautiful wildlife photographs, which remind us how creativity and close observation of the natural world can enrich both our personal lives and our medical practice. The richness of our society lies in this diversity, and we want the magazine to reflect it. We understand how personal essays or reflections can resonate just as strongly as scholarly work. Every contribution helps paint a fuller picture of who we are as a community.

For those who may feel hesitant, I encourage you to think of writing not as an intimidating task, but as an opportunity to share something meaningful. Your story might encourage a colleague, spark an idea, or remind someone that they are not alone in their struggles or joys. Sometimes, the simplest observations—a memorable patient encounter, a lesson from running a marathon, or a reflection from your own life outside of medicine—can leave the greatest impression.

Beyond writing, there are many ways to become more involved. The editorial board always welcomes new voices and fresh perspectives. If you are curious about the process, I invite you to reach out and learn more about how we put each issue together. It is a wonderful way to engage with colleagues and to contribute to shaping the voice of our society. And of course, beyond the magazine, there are many opportunities to participate in the broader work of the Pennsylvania Society of Addiction Medicine—whether through advocacy, education, or committee involvement. Each effort helps strengthen our mission to improve the lives of individuals and families affected by addiction.

As we present this third edition, my hope is that you find something here that informs, inspires, or simply reminds you of the camaraderie that binds us together. Addiction Medicine is a field that demands much of us, but it also offers us the privilege of witnessing recovery, resilience, and growth. In the same way, PSAM Review offers us a chance to step back, reflect, and share those parts of ourselves that might otherwise remain unspoken.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this issue, and to those who support the magazine in ways big and small. I look forward to seeing what future editions will bring—and I sincerely hope that more of you will add your voice to this growing conversation.

Hello Friends!

It’s difficult to believe six months have already passed and we are into our next issue of the PSAM Review!

Past President Dr. Bill Santoro continues to lead this initiative, and its respective committee. If you are a PSAM member and want to submit content for consideration, please visit the website, click the “PSAM Review” tab, and submit via the link. While we welcome a mix of submissions from our members, please understand that all content is subject to review and approval by the PSAM Editorial Committee. We also continue to work on streamlining the committee process, so stay tuned for updates. For the time being, emailing psam@pamedsoc.org and letting us know if you’d prefer to join the Public Policy Committee, Education Committee, PSAM Review Committee, or APP Committee is still the most straight-forward way.

We will shortly begin planning for our annual symposium on March 7th, 2026. In addition to a new segment of updates from our APP colleagues, we will also be expanding our efforts to highlight Addiction Medicine and Addiction Psychiatry Fellows with a revamped slate

While we welcome a mix of submissions from our members, please understand that all content is subject to review and approval by the PSAM Editorial Committee.

specifically for these learners.

In terms of public policy, this session has been relatively quiet in terms of legislation which affects our field. An adult use cannabis legalization bill fizzled out, but some version will likely pass within the next five years. PSAM’s Public Policy Committee continues to

refine its position statement on adult use cannabis legalization so that if and when a bill passes, PSAM will be able to help guide legislation in the interest of public health. One of the big holdups presently is a disagreement in the legislature about who should oversee such a program. Based on input from colleagues in states where legalization has already happened, we believe that housing it under the Liquor Control Board makes sense. The PLCB already has infrastructure for distributing alcohol in safe, secure locations and, most importantly, it minimizes advertising which is an evidence-based way to decrease child and adolescent exposure to alcohol (and, by extension, theoretically to cannabis). Some members of the legislature prefer the Gaming Control Board, or other departments/agencies and we will continue to monitor the situation and explain our stance from a public health standpoint.

Speaking of public policy, myself, Immediate Past President Dr. Kristin Van Zant, President-Elect Dr. Bhavna Bali, and Vice President Sarita Metzger will be attending ASAM’s annual Addiction Medicine Advocacy Conference (AMAC) on September 15th-16th. We had initially planned to offer scholarships for a resident and a fellow to attend, but the slots filled up unexpectedly quickly this year (so quickly in fact that ASAM will be looking for a new and larger venue next year!). We will update you on what happens at AMAC, as well as our plans to fund some learners to attend in 2026.

Finally, the national climate in terms of medicine and health policy continues to be troubling and, frankly, depressing at times. It can be easy to feel hopeless, so I encourage you to join either a PSAM or ASAM committee to filter and recycle negative energy into an instrument for meaningful change. Any and all contributions are appreciated, and always remember that better things are possible.

NET’s compassionate care and commitment to community engagement helps individuals and families heal, recover, and rebuild their lives. We are nationally recognized as a leader in recovery transformation.

NET (NorthEast Treatment Centers)

7520 State Road, Philadelphia PA, 19136

NET Centers (NET) provides individualized treatment, specialized services, and ongoing support to sustain recovery that focuses on trauma informed care and evidence based programing. The recovery continuum in both traditional and medication assisted modalities includes:

• Medications for opioid use disorder (Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Naltrexone/Vivitrol)

• Outpatient and Intensive Outpatient (IOP)

• Prison-based treatment (opioid use disorders only)

• Residential treatment

We also offer a unique after-care resource called the NET Works Recovery Support Center, completely managed by people in recovery. We support innovative programming such as our CCBHC and the Integrated Care and Wellness Center, providing an integration of physical and mental health services along with substance use services in one location.

In addition to our recovery programs, NET is committed to offering support and help to individuals and families at times of great stress in their lives, including child welfare, juvenile justice, and mental health services.

LEARN MORE about our compassionate care

by

The knot in my stomach started forming the moment I opened the chart.

Note after note with the same line in the plan, “advised to reduce alcohol”—stacked against a long problem list of injuries from falls, stroke, neuropathy, cirrhosis, and on and on. Another one of those referrals asking palliative care to do the impossible: fix a patient who was stressing the oncology team out.

I work in two worlds, outpatient oncology palliative care and opioid addiction treatment. Most days, those worlds stay separate. But this patient landed right in the overlap. Palliative care can be a dumping ground—not just for “difficult” patients, but for everyone else’s distress. I knew why he had been referred. The team wanted to treat his cancer, but the alcohol use disorder was in the way, and no one wanted to have that conversation. Perhaps they thought he needed opioids for pain but were uncomfortable prescribing them and hoped to find someone less risk-averse or less twitchy about saying no. Either way, the request was the same: help manage someone else’s unmanageable. I swallowed the dread and clicked Join Visit.

Mr. A, a man in his 70s with newly diagnosed metastatic cancer, came on screen. He was lying on his couch with his feet propped on the coffee table. Ice clinked in a highball glass in one hand while he flicked his cigarette into the ashtray with the other. Ah, the realism of a telehealth exam.

He anticipated my questions before I asked them, the habit of someone who had been counseled by decades of doctors. He already knew the risks and benefits of treatment. He understood that without chemotherapy, his cancer would progress. He knew the team wanted him to stop drinking and he was crystal clear that he did not plan to.

For the next hour, he detailed his life story, which was a variation on a theme of trauma we hear so often: fleeing a war-torn country as a toddler, smoking and drinking as a teenager, “self-anesthetizing” with more than a fifth of liquor a day after a string of losses in his 30s. He had little ambivalence about his drinking. It was a means of survival that he was not interested in parting with. Before I even opened my mouth to ask the scripted questions about serious illness trade-offs, he laid it out plainly. He would rather keep drinking, along with his prescribed benzodiazepines, even if it limited his treatment options. This was certainly not the answer the oncology team wished to hear. He wanted to try chemo, but if it made him too sick to function, he would stop. I barely said a word during the visit, but inside I was arguing loudly with myself.

I am no stranger to the “righting reflex,” a clinician’s automatic urge to fix, to rescue, to correct, when faced with a patient’s harmful behavior. I have become better at clocking my desire to shout “I can help you! Please stop drinking! There’s a solution!” Honestly, each day is like yoga practice. With Mr. A, I had to sit on my hands and box-breath to keep the words inside. I know I was not the first clinician to feel that pull with him. Forty years of finger-wagging had not helped one lick. I also understood my colleagues’ frustration. Their job is to treat cancer, and his choices stood squarely in the way. In palliative care, my role is different. I am there to listen, to clarify goals, and to witness someone’s truth, even when it collides with everyone else’s hopes.

This is not easy work. My first job, a rude awakening, was in a chronic pain clinic just as the pendulum began swinging away from liberal opioid prescribing. I went in

writing opioid doses that made me quake in my clogs and then found myself trying to convince my patients to taper off or transition to buprenorphine. Telling them that what they thought had worked for decades actually had to stop, made every visit feel like a battle. Eventually, I quit wrestling and started dancing, to use motivational interviewing verbiage. When we actually listen—digging into what made a person tick—we work alongside our patients instead of against them and can guide them as they improve their lives.

Those lessons followed me into addiction medicine, then into palliative care. Across both, I see the same truth. People will do what feels necessary to them, and trying to force anything else is an exercise in futility. My job isn’t to force change; it’s to respect human autonomy and walk with my patients where they are.

My job isn’t to force change; it’s to respect human autonomy and walk with my patients where they are.

After our visit, I documented Mr. A’s priorities clearly in the chart so the team could honor them and feel they could say they had tried their best. Of course, that was wishful thinking. This is where the stigma shows up: the assumption that a person who uses substances is reckless, manipulative, or less deserving of care. The infusion nurses still panicked when he asked how many hours he would have to sit before he could go home and drink again. I tried to explain that he was not being difficult. By hoping he could bring a bottle with him, he was just worried about his symptoms if he spent a full day in the cancer center and was trying to protect himself in the way he knew how. It is easier to label patients like Mr. A as noncompliant than to sit in the discomfort of their reality. It is easy to forget that compliance is to fit with our plan, not necessarily the patient’s.

I was later asked to see him again, this time to increase an opioid dose someone else had started. I declined. If his goal was to prolong life with cancer treatment, the risk of adding opioids to alcohol and benzodiazepines did not make sense to me. Soon after, he stopped treatment and shifted to comfort-focused care where hospice was able to manage his pain.

Before we hung up for the last time, I ordered a lift he requested when climbing steps became impossible. He thanked me profusely for listening, showering me with praise even though I had only sat relatively quietly for over an hour. I clicked End Video and sighed. It is still hard for me to accept that sometimes showing compassion for someone to live the life they choose is enough.

My work in palliative care and addiction is so much of the same. Holding everyone’s discomfort—the patient’s, my colleagues’, my own—and keeping space for choices that make sense to the person living the life, even when they do not make sense to the rest of us.

There was no happy ending waiting for Mr. A—not in the way we think of in medicine. His cancer would progress. His coping would not change. I do hope that he died knowing he had a voice in his care, with dignity and at peace.

As an addiction medicine physician working in a residential treatment center, I routinely encounter patients at pivotal, often devastating, moments. In these moments, the consequences of substance use reach crisis level. One such recent patient, a 45-year-old man facing his third residential admission, a DUI charge, and a collapsing marriage, sat across from me. During a previous visit, I told him about a promising treatment: a medication shown to reduce cravings for alcohol and, serendipitously, promote meaningful weight loss, which offered potential downstream benefits for his hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and cardiovascular disease. Now, however, I had to tell him that he, like so many others before him, would not receive this potential lifesaving treatment. His insurance denied coverage, and the out-of-pocket cost was over $1,400 a month. His face fell. Mine did, too.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, have revolutionized the treatment landscape for type 2 diabetes and obesity. As of 2024, an estimated 15 million people in the United States have been prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists1. These medications have demonstrated average weight reductions of 15–20% and significant improvements in glycemic control, including reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and decreased risk of diabetes-related complications2-4

More recently, accumulating evidence has suggested that these agents may hold considerable promise in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs), particularly alcohol use disorder (AUD). Preclinical and earlyphase clinical trials show that GLP-1RAs reduce alcohol intake, suppress drug-seeking behaviors, and may decrease relapse rates in both animal models and humans. Although GLP-1 receptor agonists are not yet FDA-approved for substance use disorders (SUDs), early clinical trials and preclinical studies have shown promising effects on reducing cravings and drug-seeking behavior in addictions including alcohol, nicotine, and stimulants. One pilot human study using exenatide for alcohol use disorder showed a significant reduction in heavy drinking days among individuals with higher BMI5. This was confirmed by a more recent study showing that patients on semaglutide had significantly less heavy drinking days than those receiving placebo. In fact 40% had no heavy drinking days in the last month of treatment compared to 20% of the placebo group.6 Preclinical studies have demonstrated that GLP-1RAs reduce cocaine, alcohol, and opioid self-administration and relapse-like behavior in rodents7-9. These

findings suggest that GLP-1RAs may modulate reward pathways through effects on the mesolimbic dopamine system, offering a novel pharmacologic approach to treating SUDs.

The proposed mechanism lies not only in their modulation of reward circuits via the mesolimbic dopamine system but also in their effects on hunger, craving, and satiety10 These psychobiological phenomena are closely intertwined with addictive behaviors11. GLP1RAs differ from traditional medications for AUD, such as naltrexone or acamprosate, by acting on both the metabolic and hedonic pathways that contribute to relapse.

Although GLP-1 receptor agonists are not yet FDAapproved for substance use disorders (SUDs), early clinical trials and preclinical studies have shown promising effects on reducing cravings and drug-seeking behavior in addictions including alcohol, nicotine, and stimulants.

Following the early data of GLP-1RAs for people with SUDs, we began prescribing them to patients who met criteria for FDA-approved indications: type 2 diabetes or obesity (BMI ≥ 27 with comorbidities). After initiating the medication, many anecdotally reported a reduction in cravings and substance use. In July of 2024, insurance approved 50–60% of our patients for these medications. Within the last few months, the approval rate hovers around 10–15%.

This shift is not due to a lack of efficacy or safety data, but rather an economic recalibration by insurers and pharmaceutical manufacturers. As demand surged, so did insurance company scrutiny, and denials followed. Compounding pharmacies began offering semaglutide and tirzepatide at a fraction of the price, circumventing cost barriers for many patients. Patients in our residential treatment setting began doing their own research on third party companies offering these medications at a fraction of the retail price.

In late 2023, the FDA declared that the production shortage of these agents had ended, thereby triggering restrictions on compounded versions under sections 503A and 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

This move has proven frustrating for providers and devastating for patients. It’s also a mistake. In our treatment center, we started patients on compounded versions during residential care to bridge them into early. Now, that option may be eliminated. Without this viable alternative, many patients will not be able

to afford these medications. They will discontinue them and not reap the benefits.

The FDA’s role is to protect public health by ensuring safety, efficacy, and reliable drug supply. We assert that the definition of “shortage” requires reconsideration. A production shortage—where supply is insufficient to meet demand—is only one aspect. An accessibility shortage, where supply exists but cannot reach patients due to cost, regulatory, systemic barriers, or other social determinants of health, is equally critical.

Access is the conduit between supply and demand. It is shaped by healthcare delivery systems, insurance policies, socioeconomic disparities, and pharmaceutical pricing strategies. When a medication is technically “available” but functionally unattainable, we must ask: have we truly emerged from the shortage?

Insurers and pharmaceutical companies operate on profit motives and shareholder interests. This asymmetry is amplified in addiction care, where time-sensitive interventions can determine life or death. Addiction medicine already contends with stigma, limited funding, and a fragmented care continuum. To restrict access to GLP-1s, one of the most promising pharmacologic tools we’ve

References:

1. Science IIfHD. The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2024: Usage and Spending Trends and Outlook to 2028 2024. https://www.iqvia. com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/ the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us-2024

2. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. Mar 18 2021;384(11):989–1002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

3. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. Jul 21 2022;387(3):205–216. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

4. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus oncedaily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. May 2017;5(5):355–366. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2

encountered in a generation, is short-sighted and unethical.

The access barriers facing GLP1receptor agonists are not unique to addiction medicine. Historically, other therapeutic areas have confronted, and overcome, similar challenges. For instance, the Ryan White CARE Act provided federal funding that dramatically expanded access to HIV treatment among underserved populations, transforming the course of the epidemic12. In the case of hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment, costeffectiveness modeling played a pivotal role in driving broader insurance coverage and public health investment in direct-acting antivirals (DAAs)13. The oncology field is experiencing the successful expansion of insurance coverage for high-cost chemotherapeutic agents, in part due to advocacy, outcomes research, and economic modeling demonstrating value14

These precedents suggest that multi-pronged approaches— including health economic analyses, policy advocacy, and pilot funding mechanisms—could help establish GLP-1RAs as standardof-care treatments in addiction medicine. By drawing on these models, stakeholders in addiction care can advance both the clinical and ethical imperative to improve access to these promising agents.

This crisis requires a multidisciplinary effort—from regulators, pharmaceutical manufacturers, insurers, and clinicians—to reassess how access and shortage is defined. The FDA should consider not only whether a medication exists in warehouses but also whether it reaches the people who need it. That includes patients in residential treatment for SUDs, many of whom suffer from obesity, metabolic dysfunction, and crippling cravings.

In an ideal world, insurance companies would cover these medications for patients meeting the FDA-approved indications as a first step. This would allow us to prescribe them to an overwhelming majority of patients with SUD. As the data continues to mount, the next step would be the approval of these medications for SUDs. In the meantime, the FDA should strongly reconsider its ruling and allow for the access to these medications regardless of insurance approval.

As we face the dual epidemics of obesity and addiction, GLP-1 receptor agonists represent a bridge between metabolic health and recovery. To deny patients this opportunity is to perpetuate a two-tiered system where only the affluent can afford innovation.

To our colleagues in addiction medicine, we urge you to

remain vocal. To insurers and pharmaceutical leaders: join us on the front lines. Help us ensure that access to evidence-based care is not dictated by income but rather driven by need.

Statement of Off-Label

Discussion: This manuscript discusses the off-label use of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), including semaglutide, tirzepatide, and exenatide, for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs). These medications are not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication. All off-label uses are clearly identified and contextualized within emerging clinical and preclinical evidence.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Noah Davis for editing and formatting services.

Dr. Steven Daniel Klein is a physician-scientist specializing in Addiction Medicine and Medical Genetics. He completed his Addiction Medicine fellowship at Caron Treatment Centers and Tower Health and now serves as a staff physician at Caron. His work focuses on innovative treatments such as GLP-1 receptor agonists for substance use disorders, and he is dedicated to advancing individualized, compassionate care for patients and families.

5. Klausen MK, Jensen ME, Moller M, et al. Exenatide once weekly for alcohol use disorder investigated in a randomized, placebocontrolled clinical trial. JCI Insight. Oct 10 2022;7(19)doi:10.1172/jci.insight.159863

6. Hendershot CS, Bremmer MP, Paladino MB, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. Apr 1 2025;82(4):395–405. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789

7. Egecioglu E, Steensland P, Fredriksson I, Feltmann K, Engel JA, Jerlhag E. The glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue Exendin-4 attenuates alcohol mediated behaviors in rodents. Psychoneuroendocrinology Aug 2013;38(8):1259–70. doi:10.1016/j. psyneuen.2012.11.009

8. Aranas C, Edvardsson CE, Shevchouk OT, et al. Semaglutide reduces alcohol intake and relapse-like drinking in male and female rats. EBioMedicine. Jul 2023;93:104642. doi:10.1016/j. ebiom.2023.104642

9. Zhang Y, Kahng MW, Elkind JA, et al. Activation of GLP-1 receptors attenuates oxycodone taking and seeking without compromising the antinociceptive effects of oxycodone in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology Feb 2020;45(3):451–461. doi:10.1038/ s41386-019-0531-4

10. Dickson SL, Shirazi RH, Hansson C, Bergquist F, Nissbrandt H, Skibicka KP. The glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, exendin-4, decreases the rewarding value of food: a new role for mesolimbic GLP-1 receptors. J Neurosci. Apr 4 2012;32(14):4812–20. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6326-11.2012

11. Shirazi RH, Dickson SL, Skibicka KP. Gut peptide GLP-1 and its analogue, Exendin-4, decrease alcohol intake and reward. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61965. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061965

12. Kates J, Dawson L, Horn TH, et al. Insurance coverage and financing landscape for HIV treatment and prevention in the USA. Lancet. Mar 20 2021;397(10279):1127–1138. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00397-4

13. Najafzadeh M, Andersson K, Shrank WH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of novel regimens for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med. Mar 17 2015;162(6):407–19. doi:10.7326/M14-1152

14. Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: A Conceptual Framework to Assess the Value of Cancer Treatment Options. J Clin Oncol. Aug 10 2015;33(23):2563–77. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706

By Kristin Van Zant, M.D., FASAM, DLFAPA; Immediate Past President PSAM and current Chair Education Committee

From beginning to end, AMAC 2025 hit the winning run in the World Series of Advocacy for addiction specialists from around the United States.

On September 15-15, 2025, the American Society of Addiction Medicine partnered with the American College of Medical Toxicology and the American College of Academic Addiction Medicine to sponsor the annual Addiction Medicine Advocacy Conference (AMAC) in Washington, D.C. The conference provided components of training and education to enable 100 AMAC participants from around the country to call on their Senators, Representatives, and associated staff in carefully planned 30-minute meetings on Capitol Hill to ask for support on key bills.

The road from concept to law has many steps and can involve years of advocacy and planning. A particular bill may need to be introduced multiple times before it garners congressional support to be passed into law. Moving the needle forward can involve many painstaking steps of monitoring the progress of a bill through Congress. This patient and careful attention to the legislative process is evident with this year’s need to re-introduce two pieces of legislation. AMAC’s “asks” were:

1. The re-introduction and ask for cosponsorship of the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Act (MOTAA)

Outdated federal restrictions currently limit methadone dispensing to federally regulated opioid treatment programs. People in need have many barriers to accessing this life-saving care including financial, transportation, and geographic access. With OTP deserts in 80% of U.S. counties, this lifesaving treatment is inaccessible to many individuals in need. MOTAA would enable addiction specialist professionals to prescribe Methadone for OUD for people to pick up at community pharmacies.

2. The re-introduction and ask for cosponsorship of the Residential Recovery for Seniors Act (RRSA)

Currently there is a major treatment gap for older adults with Medicare who have substance use disorders. Of the 6 million Medicare beneficiaries with SUD, <25 % receive any treatment. The RRSA would create a Medicare Part A benefit for residential addiction treatment as ASAM Level 3.1 Clinically Managed Low-Intensity Residential Treatment; Level 3.5 Clinically Managed High-Intensity Residential Treatment; and Level 3.7 Medically Managed Residential Treatment. It would also establish a prospective payment system for these programs that would ensure reimbursement would be based on predetermined, fixed amounts.

PSAM members showed up in full force at AMAC with participants from multiple health systems, agencies, and counties across the Commonwealth. There was representation from Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, and Lancaster. There were Addiction Medicine/ Psychiatry fellows, newer attendings in Emergency Medicine and Internal Medicine, as well as CEOs of health systems/companies and Medical Directors of a start-up as well as CCBHCs.

PSAM member, and ASAM Legislative and Public Policy Committee Member, Dr. Mitchell Crawford voiced his support of the advocacy process. “AMAC is an incredible opportunity to advocate at the highest level for the change we know needs to occur in the communities we represent and love. I view advocacy a lot like leadership and voting: if you do not participate, you can’t complain about what happens, So, if you haven’t joined an advocacy effort yet, what are you waiting for?”

PSAM APP Committee Chair Arielle Bivas has participated in AMAC for several years. She enthusiastically said, “The highlight of AMAC for me was the opportunity to join clinicians from across the Commonwealth AND country in a shared mission. The sense of unity and collective purpose makes the experience incredibly energizing!” The opportunity to engage in meaningful work with colleagues from across Pennsylvania was meaningful to Penn State College of Medicine participant Dr. Amy Hoffman. Dr. Hoffman was a first-time attendee at AMAC along with being 3 months into a PGY4 Addiction Medicine fellowship. When asked for her impression of AMAC she said, “Addiction Medicine is an interdisciplinary field. We see directly how laws and policies affect our practice and patients. It is meaningful to engage in advocacy because we can help humanize and destigmatize our

patients and the care they need when we meet with legislators. The highlight for me was when the Pennsylvania team was able to speak directly with Senator McCormick about our key issues. It was incredibly powerful that Senator McCormick got to meet and speak directly with addiction medicine physicians.”

AMAC 2025 results will not be known for some time. We need to continue our Advocacy work with focus and determination. Please join your colleagues for the next AMAC in September 2026!

by Peter DeMaria, MD, DFASAM, DFAPA

Ifinished my evaluation and asked the patient, “Is there anything else that we didn’t discuss or that I should know?” The patient pauses, and then responds, “Oh, yes, I have a medical card.” There is another pause, and they add, “It’s medicine.” Of course, I have dutifully asked the patient about their medical history, current medications, and tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug usage. The patient did not mention their marijuana (MJ) use. Was I not thorough in my history? Was the patient trying to conceal their MJ use? Or is this a new era in which society is trying to understand the role of MJ and how to discuss it? Certainly, the days of the scare tactic public service announcements such as the film Reefer Madness and the Scared Straight program to educate juveniles about the perils of drug use are giving way to an era in which MJ is accepted as a medicine and recreational substance. What do physicians do when confronted with a patient who reports medical or recreational MJ use?

use MJ to achieve relief. Nevertheless, one must consider if MJ is treating the core problem or masking it.

Stress can lead to anxiety; however, anxiety can be both a problematic symptom and a catalyst for positive change. In my psychiatry training I had a supervisor who cautioned against the use of benzodiazepines to treat anxiety, indicating that if a patient is anxiety–free, they may not feel the need for change. Without change, they may not get better. Obviously, there is an indication

use in at–risk youth is associated with earlier development of schizophrenia and a worse prognosis for the disease with continued use. Finally, our understanding of the effects of MJ on the developing adolescent brain is emerging (Hoch, 2025).

Certainly,

the days of the scare tactic public service announcements such as the film Reefer Madness and the Scared Straight program to educate juveniles about the perils of drug use are giving way to an era in which MJ is

accepted as a medicine and recreational substance.

Despite MJ’s documented therapeutic potential, it is not a benign drug. When working with patients who are using MJ, talk with them about their reasons for using it and the positive and negative effects they notice. Look at the intersection of a patient’s coping mechanisms and the role MJ is playing in helping, delaying, or preventing them from addressing their issues. Ultimately, one of the physician’s key jobs is to help a patient attain and maintain a healthy life. This includes understanding their MJ use.

Just as society’s view of MJ is changing, so are the available products. The average percentage of THC, the most significant psychoactive component, tripled from 4% to 12% from 1995 to 2014 (ElSohly et al, 2016). Currently, plant product averages 20% THC, with concentrates available up to 80% (United States Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration, 2014). Cannabis botanists are using techniques to develop myriad strains of various potencies and combinations of cannabinoids. Therefore, when a patient acknowledges MJ use, ask them if they know what percentage THC they are using; one would be surprised how informed patients are about their product choice and reasons. Engage in the conversation.

Yes, there is medicinal value in MJ for specific disorders. Despite the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania allowing people to be certified to obtain a medical card for twenty–four serious medical conditions, MJ has only been shown to be therapeutically effective for some of those conditions, including chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, appetite stimulation in AIDS, neuropathic pain, spasticity, and two forms of pediatric epilepsy (Hill, 2019). MJ’s actions on the endocannabinoid system are still being understood. The system appears to be involved in the body’s stress management (Lutz, 2015) as well as other physiological functions, including immune, cardiovascular, and endocrine regulation (Lowe, 2021). Given that many patients present with symptoms related to stress and poor coping mechanisms, it seems logical for many to

for pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders. One needs to tailor treatment interventions to each patient’s needs. The question becomes whether MJ use is helping or impeding the patient by causing a sense of improvement without any meaningful change. Nineteenth–century French essayist and poet Charles Baudelaire noted in his 1860 treatise Les Paradis Artificiels how hashish, a MJ product, “gives with one hand what it takes away with the other—that is to say, it feeds the imagination, without allowing one to profit by the gain” (Baudelaire, 1996, p. 74). A century later, the controversial amotivational syndrome was described by David Smith (1968). A physician should have a discussion with their patient about their patient’s MJ use, its positive and negative effects, and the role it plays in their life to help the physician address motivation and stress management directly. Some patients are convinced of the merits of MJ use; they only recognize its negative effects once they stop using it.

Ongoing use of MJ has been associated with negative life success. In a longitudinal study in Christchurch, New Zealand investigators followed individuals from birth to age twenty–five and found a strikingly positive correlation between higher MJ use and lower levels of degree attainment, lower income, higher welfare dependence, higher unemployment, lower relationship satisfaction, and lower levels of life satisfaction (Ferguson and Boden, 2008). With today’s higher potency products, other problems can emerge including worsened anxiety, toxic psychosis, hyperemesis syndrome, and problems with concentration and focus creating an ADHD–like syndrome. Moreover, patients with comorbid ADHD can experience worsening symptoms (Francisco, 2023). MJ

Dr. DeMaria is the Coordinator of Psychiatric Services at Tuttleman Counseling Services Temple University and a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

References:

1. Baudelaire, C. (1996). Artificial paradises (S. Diamond, Trans.). Carol Publishing Group. (1860).

2. ElSohly, M.A., Mehmedic, Z., Foster, S., Gon, C., Chandra, S., & Church, J.C. (2016). Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995–2014): Analysis of current data in the United States. Biological Psychiatry 79(7), 613–619. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.004

3. Francisco AP, Lethbridge G, Patterson B, Goldman Bergmann C, Van Ameringen M. (2023). Cannabis use in Attention - Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A scoping review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 157, 239-256. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.11.029

4. Hill, K.P. (2019). Medical use of cannabis in 2019. JAMA, 322(10), 974–975. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.11868

5. Hoch E, Volkow ND, Friemel CM, Lorenzetti V, Freeman TP, Hall W. (2025). Cannabis, cannabinoids and health: a review of evidence on risks and medical benefits. European Archive of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 275(2), 281-292. doi:10.1007/s00406-024-01880-2

6. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, Bryant J, Ngwa W. (2021). The Endocannabinoid System: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Various Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Science, 22(17), 9472. doi:10.3390/ijms22179472

7. Lutz B, Marsicano G, Maldonado R, Hillard CJ. (2015). The endocannabinoid system in guarding against fear, anxiety and stress. Nature Review: Neuroscience, 16(12), 705-718. doi:10.1038/nrn4036

8. Smith, D.E. (1968). Acute and chronic toxicity of marijuana. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 2(1), 37–48.

9. United States Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration. (2014). What you should know about marijuana concentrates also known as: THC Extractions. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/resource-center/ Publications/marijuana-concentrates.pdf

by William Santoro, MD, FASAM, DABAM

As cannabis policies evolve across Pennsylvania, the United States, and beyond, healthcare professionals are increasingly involved in discussions surrounding legalization. Understanding the nuanced differences between recreational and medical cannabis legalization is essential for clinicians tasked with patient guidance, public health advocacy, and policy input. What is needed is an objective, evidence-based discussion—free from emotion, stigma, and judgment—about the benefits and drawbacks of each approach. What follows, I hope, is a comparative analysis to inform medical professionals about the potential implications of each approach.

There are substantial benefits to the legalization of recreational cannabis, particularly in addressing long-standing inequities in the criminal justice system. One of the most impactful is the significant reduction in arrests for simple cannabis possession, which historically have disproportionately affected communities of color and those of lower socioeconomic status. According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), between 2010 and 2018, Black individuals were 3.64 times more likely than white individuals to be arrested for marijuana possession, despite similar usage rates across racial groups (ACLU, 2020). In some states, the disparity was even greater—up to 9 or 10 times higher.

sold in licensed dispensaries are routinely tested for THC and CBD potency, as well as for contaminants. Regulated testing significantly reduces the risks posed by illicit cannabis, which often lacks standardized dosing and may contain harmful adulterants (Paul, 2022). Legalization also enables data collection, which is critical for evidence-based policymaking and clinical guidance (CDC, 2025).

Despite regulation and the aforementioned benefits, recreational cannabis legalization carries significant drawbacks. Research indicates that even with age restrictions in place, states with legalized recreational use have experienced increased cannabis exposure among adolescents. While states have implemented age restrictions and public health campaigns, the effectiveness of these measures remains mixed, highlighting the need for continuous evaluation and improvement. This trend is concerning, given that early cannabis exposure has been linked to disruptions in brain maturation, particularly

Both recreational and medical cannabis legalization carry complex implications for individual and public health. As legalization efforts expand, physicians must play a proactive role in educating patients, shaping policy, and advocating for rigorous research and evidencebased regulation. The distinction between recreational and medical use is not always clear-cut, but the medical profession has a duty to support safe, informed, and compassionate use of cannabis when clinically appropriate. This needs to be done rationally, scientifically, and without emotion.

As legalization efforts expand, physicians must play a proactive role in educating patients, shaping policy, and advocating for rigorous research and evidence-based regulation.

in regions related to memory, attention, and executive function. Long-term neurocognitive consequences—especially when use begins during adolescence—remain an area of active study, but current evidence suggests a potential for lasting cognitive impairment (NIDA, 2020).

Moreover, these enforcement patterns reflect broader systemic issues. In lowerincome neighborhoods, heightened police presence, fewer legal resources, and implicit bias compound the effects of these laws. Arrests can have cascading consequences: loss of employment, housing instability, barriers to education, and family disruption. Legalization reduces the footprint of law enforcement in low-level cannabis offenses, thereby helping to address institutional disparities and promote equity. Several studies from states like Colorado and California have shown sharp declines in possession-related arrests following legalization, particularly among young Black and Hispanic men, suggesting that reform has tangible equity benefits (Sheehan et al., 2021).

States that have legalized recreational cannabis have seen substantial financial returns. For example, in 2022, legal cannabis sales generated over $3.7 billion in tax revenue across the U.S., with a significant portion allocated to public goods. In Colorado, more than $500 million has been directed toward education funding since legalization (MPP, 2023).

Legalization also allows for the implementation of standards to ensure product quality and consumer safety. Cannabis products

Cannabis use disorder (CUD), now a recognized diagnosis, affects approximately 9–10% of users, with higher rates among daily or high-potency users (Hasin et al., 2015). Moreover, frequent cannabis use has been linked to the onset or worsening of psychiatric conditions, including anxiety, depression, and psychosis—especially in individuals with underlying vulnerabilities or genetic predispositions. Clinicians should be aware of these associations when assessing mood and thought disorders in patients who report regular cannabis use (Hasin et al., 2015).

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, has welldocumented effects on reaction time, short-term memory, and motor coordination, all of which can compromise driving and occupational safety. However, THC can remain detectable in a person’s system for days to weeks depending on frequency of use, and unlike blood alcohol concentration (BAC), there is no accepted quantitative level that equates to impairment. This presents ongoing challenges for both law enforcement and workplace drug policies, as current testing methods cannot reliably differentiate between acute impairment and residual THC levels from prior use (Arkell et al., 2021).

Evidence supports the use of medicinal cannabis for specific conditions, including chronic neuropathic pain, chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting, and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. In these cases, cannabis may offer symptom relief where conventional treatments fall short. There is little doubt that patients would benefit from physician involvement in guidance on product selection, dosing, route of administration, and monitoring for adverse effects or misuse. However, high-quality clinical evidence remains limited. The current body of research includes few high-quality, randomized controlled trials, leaving clinicians to rely heavily on anecdotal reports and observational data (Whiting et al., 2015). The above notwithstanding, some observational studies suggest that medical cannabis access may correlate with reduced opioid prescribing and opioid-related harms, though causality remains unproven and contested. Nonetheless, it would be disingenuous to overlook the potential role of legal medical cannabis as a therapeutic option for patients who have exhausted conventional therapies or for whom limited alternatives exist.

Unfortunately, in some jurisdictions, medical cannabis programs have been exploited as a proxy for recreational use, particularly where eligibility criteria are loosely defined or poorly enforced. When Pennsylvania’s medical cannabis law—Act 16—was passed in April 2016, the law initially listed 17 qualifying medical conditions for eligibility (PA Dept. of Health, 2025). These included:

1. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

2. Autism

3. Cancer

4. Crohn’s disease

5. Damage to the nervous tissue of the spinal cord

6. Epilepsy

7. Glaucoma

continued on next page

8. HIV/AIDS

9. Huntington’s disease

10. Inflammatory bowel disease

11. Intractable seizures

12. Multiple sclerosis

13. Neuropathies

14. Parkinson’s disease

15. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

16. Severe chronic or intractable pain

17. Sickle cell anemia

Patients are left to bear the full financial burden of treatment—further underscoring the need for policy reform grounded in evidence and equity.

Since its inception, Pennsylvania’s list of qualifying medical conditions for cannabis use has steadily expanded—a trend mirrored in other states. Notably, in 2019, the Pennsylvania Department of Health added Tourette’s syndrome to the list of qualifying conditions. Later, in 2022, chronic hepatitis was also included. Additional conditions—such as opioid use disorder and anxiety—were added in later years by the state’s Medical Marijuana Advisory Board and the Pennsylvania Department of Health (PA Dept. of Health, 2025). As of 2025, the state recognizes 24 serious medical conditions that make patients eligible for medical marijuana treatment.

These expansions are often driven by patient advocacy, political lobbying, and evolving public opinion. In some jurisdictions, eligibility criteria have become so broad that nearly anyone can qualify, raising legitimate questions about the purpose of maintaining a qualification system at all. Yet, cannabis remains classified as a Schedule I substance under federal law, a designation that restricts scientific research, complicates interstate commerce and prevents insurance coverage. As a result, patients are left to bear the full financial burden of treatment—further underscoring the need for policy reform grounded in evidence and equity. If medicinal cannabis is to be a viable process, this Schedule I classification must be reevaluated to enable broader clinical research and patient access.

As legalization efforts evolve, physicians are uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between public policy and patient care. We must champion rigorous research, advocate for sensible regulation, and ensure that patients receive accurate, compassionate, and clinically appropriate guidance. While the boundaries between medical and recreational use continue to blur, our responsibility is to promote better health and minimize harm through informed,

evidence-based practice. History offers a useful reminder: alcohol is legal despite its welldocumented harms, and the failure of Prohibition teaches us that blanket bans can yield unintended consequences. Even today, science continues to uncover the adverse health effects of alcohol— proof that legality does not equate to safety, and that ongoing scrutiny is essential.

In shaping policy and public understanding, we would do well to remember Aristotle’s enduring insight: “The law is reason, free from passion.” Let our contributions be guided not by ideology or emotion, but by clarity, integrity, and the unwavering pursuit of scientific truth.

People with OUD in the criminal justice setting (eg, drug court, jail, prison) go untreated while incarcerated. Incarceration can cause barriers to treatment access, specifically medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).6

This article was originally published in the Summer 2025 issue of Berks County Medical Record.

Treatment at home or via telehealth may be more accessible, especially for patients who lack transportation or have competing priorities, like work and childcare.4

References:

18. Marijuana Policy Project. (2023, May 1). States surpass $15 billion in tax revenue from legal, adult use cannabis sales. Retrieved from https://www.mpp.org/news/press/states-surpass-%2415billion-in-tax-revenue-from-legal-adult-use-cannabis-sales/

The office or clinic setting allows for direct patient-provider interaction. This may benefit patients worried about withdrawal or other issues.2

19. Paul, S. (2022). A clinical framework for evaluating cannabis product quality and safety. PMCID PMC10249738. https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10249738/

20. National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Marijuana research report: What are marijuana’s long-term effects on the brain? National Institutes of Health. https:// nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/ what-are-marijuanas-long-term-effects-brain

21. Whiting, P. F., Wolff, R. F., Deshpande, S., Di Nisio, M., Duffy, S., Hernandez, A. V., … Westwood, M. (2015). Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 313(24), 2456–2473. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.6358

22. Arkell, T. R., Spindle, T. R., Kevin, R. C., Vandrey, R., & McGregor, I. S. (2021). The failings of per se limits to detect cannabis induced driving impairment: Results from a simulated driving study. Traffic Injury Prevention, 22(2), 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2020.1851685

23. Association of Racial Disparity of Cannabis Possession Arrests Among Adults and Youths With Statewide Cannabis Decriminalization and Legalization. Brynn E. Sheehan, PhD; Richard A. Grucza, PhD; Andrew D. Plunk, PhD. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(10):e213435. https://doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3435

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Accessed March 6, 2025). Cannabis: Facts and stats. https:// www.cdc.gov/cannabis/facts-stats/index.html

25. American Civil Liberties Union. A tale of two countries: Racially targeted arrests in the era of marijuana reform. Published April 2020. Accessed [today’s date]. https://www.aclu.org/report/ tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform

26. Pennsylvania Department of Health. (2025). Medical Marijuana Program. Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://www.pa.gov/ agencies/health/programs/medical-marijuana.html

27. Hasin, D. S., Saha, T. D., Kerridge, B. T., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Zhang, H., ... & Grant, B. F. (2015). Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858

How are you making sure patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) are getting the appropriate continuous and quality care they need?

Hospital Inpatient

The inpatient setting is a wake-up call for many patients, but challenges exist for continued care after discharge. Look out for barriers such as unstable housing or co-occurring pain.1

Office/Clinic

The office or clinic setting allows for direct patient-provider interaction. This may benefit patients worried about withdrawal or other issues.2

Emergency Department

Emergency department visits offer access to lifesaving treatment for individuals with OUD.3

Treatment at home or via telehealth may be more accessible, especially for patients who lack transportation or have competing priorities, like work and childcare.4

Residential Treatment Centers

Managing patients who have OUD requires attentive care from physicians and other providers due to the complexity of their disorders. Longer-term care settings can provide this.5

Criminal Justice System

People with OUD in the criminal justice setting (eg, drug court, jail, prison) may go untreated while incarcerated. Incarceration can cause barriers to treatment access, specifically medications for OUD (MOUD).6

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), patients experiencing OUD should “have access to mental health services as needed, medical care, and addiction counseling, as well as recovery support services, to supplement treatment with medication.”7

References:

F Meet to discuss complex cases

F Practice “warm handoffs” by directly introducing the patient to new providers

F Diversify the care team with healthcare professionals from different specialties and sites of care

F Aim to start patients on MOUD during the first visit

F Guarantee patients a follow-up appointment within 72 hours

F If a patient cannot be seen right away, offer “front of line” access for the next day

F Offer a number of locations and options for OUD-related appointments, including mobile clinics, if available

F Suggest telehealth or home medication delivery to individuals lacking access to transportation

F Form contacts with local behavioral health, housing, and employment organizations

F Assess if mental health, housing, or employment services are needed

F Provide referrals or offer to set up appointments for those seeking such services

F Utilize peer support specialists (persons in recovery with lived experience) to enhance shared understanding, respect, and mutual empowerment9

F Have peer support specialists check in with individuals with OUD regularly, especially in the early stages of treatment

F Consider broad dosing schedules rather than requiring appointments

F Provide treatment on demand, as appropriate

1. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s Been an Experience, a Life Learning Experience”: A Qualitative Study of Hospitalized Patients With Substance Use Disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;32(3):296–303. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Practical Tools for Prescribing and Promoting Buprenorphine in Primary Care Settings. 2021. Accessed May 9, 2025. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-06-01-002.pdf

3. SAMHSA. Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment in Emergency Departments. 2021. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/use-medication-assisted-treatment-emergency-departments

4. SAMHSA. Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. 2021. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/telehealth-treatment-serious-mental-illness-substance-use-disorders

5. Massachusetts Dept of Public Health. The Care of Residents With Opioid & Stimulant Use Disorders in Long-Term Care Settings Toolkit. Mass.gov. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://mass.gov/info-details/the-care-of-residents-with-opioid-stimulant-use-disorders-in-long-term-care-settings-toolkit

6. SAMHSA. Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings. 2019. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/use-medication-assisted-treatment-opioid-use-disorder-criminal-justice-settings

7. SAMHSA. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Updated 2021. Accessed July 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-02-01-002.pdf

8. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Models for Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder, Retention, and Continuity of Care. July 2020. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_ files//195116/MATOUDModels.pdf

9. SAMHSA. Peer Support Workers for Those in Recovery. Updated November 5, 2024. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/technical-assistance/brss-tacs/peer-support-workers

Narcolepsy and Sleep Regulation

The human sleep cycle consists of four stages: three NREM phases and one REM phase, regulated by neuromodulators primarily acting on the lateral hypothalamus. Disruptions to this cycle can result in sleep disorders, with narcolepsy being one of the most profound examples [1]. Narcolepsy presents as excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and abnormal REM regulation. It is classified into Type 1, characterized by cataplexy and hypocretin deficiency, and Type 2, which lacks these features [2]

Cannabis and Sleep Modulation

Cannabis, widely used for its psychoactive properties, particularly THC, can alter sleep architecture. THC has sedative effects, while CBD appears to promote wakefulness [3]. These properties suggest that cannabis use could influence symptoms and diagnostic assessments for narcolepsy, potentially confounding clinical evaluations.

Review

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, yielding 13 articles related to cannabis use and narcolepsy. Of these, only one study evaluated adult cannabis use, hypersomnia, urine toxicology, and sleep study results together [4] An additional pediatric study was identified via Google Scholar.

Inclusion of Related Studies

Further literature that discussed excessive daytime sleepiness, the hypocretin and endocannabinoid pathways, and cannabis use effects was included to broaden the scope of the analysis [5-8]

Results

Endocannabinoid System and Sleep Regulation

Endogenous cannabinoids, acting through CB1 and CB2 receptors, inhibit hypocretin-secreting neurons, thereby reducing arousal and promoting sedation [9]. Regular cannabis use is associated with sleep disturbances and variations in sleep architecture [10]

Evidence of Cannabis and Narcolepsy

Retrospective studies found that both adult and pediatric patients who tested positive for THC demonstrated sleep study results consistent with narcolepsy [4,5]

Chronic cannabis use complicates interpretation of multiple sleep latency tests (MSLT), often leading to findings suggestive of narcolepsy, such as decreased mean sleep onset latency and increased sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMs) [5,6] .

Impact of Cannabis Use Patterns

Severity and frequency of cannabis use were found to influence the extent of sleep disruption. Heavy cannabis use can decrease total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and alter REM and NREM sleep, particularly during withdrawal periods [10,11]. CBD, in contrast to THC, was noted to have wake-promoting effects, demonstrating the complexity of cannabis’ impact on sleep patterns [3,8]

Discussion

THC and CBD’s Contrasting Effects

THC generally promotes sedation through CB1 receptor interaction, whereas CBD can enhance wakefulness and potentially counteract THC’s sedative effects [3,8]

Chronic THC use affects the sleepwake cycle through its actions on the endocannabinoid system and the hypocretinergic system, crucial in maintaining wakefulness [9]

Diagnostic Challenges and Urine Toxicology

Urine toxicology has emerged as an important tool to distinguish between true narcolepsy and cannabis-induced hypersomnia [4,5]

Patients with positive THC screens exhibited narcoleptic features on sleep studies without classic cataplexy, suggesting that cannabis use can mimic or exacerbate narcolepsy symptoms [5,6]

Cannabinoid Interaction with Hypocretin System

Cannabinoids’ modulation of the orexinergic (hypocretin) system, which regulates the sleep-wake cycle, further supports the biological plausibility of these findings [9] Abrupt cannabis withdrawal can

result in REM rebound and unusual dreams, complicating sleep disorder diagnoses [10]

Implications for Clinical Practice

Given the rising prevalence of cannabis use, particularly among adolescents and young adults, clinicians must carefully consider substance use history when interpreting sleep study results. Abrupt withdrawal from marijuana may result in strange dreams and rebound REM [5]. Although preliminary evidence suggests that cannabinoids like CBD might eventually be utilized therapeutically in sleep disorders, there is currently insufficient clinical evidence to recommend cannabinoids for treating central disorders of hypersomnolence like narcolepsy [12]

Conclusions

Cannabis use significantly impacts the sleep cycle and neuronal pathways regulating sleep and wakefulness. THC’s sedative properties and its modulation of the hypocretin system can confound the diagnosis and presentation of narcolepsy. Therefore, cannabis use assessment should be an integral part of the diagnostic evaluation for sleep disorders to ensure accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment planning.

Future research should focus on randomized controlled trials to better delineate cannabinoids’ role in sleep disorders and explore their potential therapeutic applications while considering the risks associated with their use.

Dr. Parul Chhatpar is a PGY-3 preventive medicine resident at UMass Chan Medical School with a strong interest in addiction medicine. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Vanderbilt University and her medical degree from William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine. Her professional interests include addiction medicine, health disparities, mental health, and public policy; with a particular interest in evidence-based strategies to improve access to care for underserved and marginalized populations.

Dr. Chhatpar is an active member of the American College of Preventive Medicine, contributing to the conference planning and education committees. She is also

a peer reviewer for the Journal of Addiction Medicine and serves on the American Public Health Association Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Committee and the Integrative Behavioral Health Committee. Additionally, she is a member of the American Osteopathic Association Bureau of Emerging Leaders Collaborative Cohort and contributes to the AOA Data Subgroup.

In her free time, she enjoys knitting and reading. Joining the Worcester Medicine editorial board brings Dr. Chhatpar full circle to her undergraduate love of English literature. Her favorite authors are Isabel Allende and Jane Austen; a recent favorite novel is Trust by Hernan Diaz.

References:

1. Patel AK, Reddy V, Shumway KR, et al.: Physiology, Sleep Stages. StatPearls Publishing, 2024.

2. Krahn LE, Zee PC, Thorpy MJ. Current Understanding of Narcolepsy 1 and its Comorbidities: Adv Ther. 2022. https://pmc. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8799537/.

3. Babson KA, Sottile J, Morabito D: Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Sleep: a Review of the Literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017. https:// www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/assets/user-content/ documents/s11920-017-0775-9.pdf.

4. Dzodzomenyo S, Stolfi A, Splaingard D, et al.: Urine Toxicology Screen in Multiple Sleep Latency Test: Correlation of Positive THC and Narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015.

5. Cruz JM, Estrellado-Cruz WLC: Recreational Marijuana Use Presenting as Narcolepsy. AJRCCM Conf. 2020.

6. Gorantla S, Grigg-Damberger M: Sleep Disorders: A Case a Week from the Cleveland Clinic. Oxford Academic. 2019.

7. Maddison KJ, Kosky C, Walsh JH: Is There a Place for Medicinal Cannabis in Treating Patients with Sleep Disorders? Nat Sci Sleep. 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ articles/PMC9124464/#:~:text=The%20 THC%2Dinduced%20attenuation%20 in,sleep%20wake%20hallu....

8. Low ZXB, Lee XR, Soga T, et al.: Cannabinoids: Emerging Sleep Modulator. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023. https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S0753332223008934.

9. Flores A, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Cannabinoid-hypocretin Cross-talk in the CNS: Front Neurosci. 2013. https://pmc. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3868890/.

10. Kesner AJ, Lovinger DM: Cannabinoids, Endocannabinoids and Sleep. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020. https://pmc.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7388834/.

11. D’Angelo M, Steardo L Jr: Cannabinoids and Sleep: Exploring Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/articles/PMC11011314/.

12. Maddison KJ, Kosky C, Walsh JH: Is There a Place for Medicinal Cannabis in Treating Sleep Disorders? Nat Sci Sleep. 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ articles/PMC9124464/#:~:text=The%20 THC%2Dinduced%20attenuation%20 in,sleep%20wake%20hallucinations%20 and%20cataplexy

by Timothy K. Burke, DO, and Scott Constantini

Problem Statement

Integrating addiction treatment with primary health services can greatly benefit individuals in recovery, particularly when primary health service includes behavioral health, oral health, and infectious disease care.1,2

Unfortunately, access to robust, integrated primary health and addiction medicine services remains challenged, and many primary care physicians have limited training in treating patients with addiction, which affects their ability to offer MAT.3 The Wright Centers for Community Health (TWCCH) and Graduate Medical Education (TWCGME) together form a Graduate Medical Education Safety-Net consortium (GME SNC) that utilized opportunities to

serve communities and educate future physicians to increase access to primary health integrated recovery services.

Pennsylvania had the nation’s third-highest mortality rate of drug overdose in 2017.4 Then Governor Tom Wolf appointed TWCCH, an FQHC Look-Alike (offering primary health, mental/behavioral health, and oral health), a Center of Excellence (COE) for opioid use disorder treatment, and TWCGME integrated addiction medicine in its primary care GME programs. Trainees work with physicians, certified recovery specialists, and case managers to receive first-hand experience in medically-assisted treatment (MAT), and treatment strategies and best practices for SUD and opiate use disorder (OUD). Residents also engage in an 8-hour session on OUD treatment and prevention during orientation, and attend community based recovery support groups. Didactic sessions on addiction and stigma are done throughout the academic year, with encouragement to produce scholarly work on the topics.

Educating trainees in a COE initiative prepares future physicians to, during a PCP visit, support patients who may not have reached out for recovery services otherwise. Embedding this education with primary care allows us to reach wider populations and have a unique impact on stigma as a physical health COE. Through this integration, we educate medical residents, staff, and other learners to treat addiction no differently than any other chronic disease; normalizing addiction as a condition to eliminate stigma.

Since the integration, we have successfully trained 356 residents. By the time residents graduate, TWCGME provides three years of hands-on experience in the treatment of SUD; some graduates go on to become addiction fellowship trained. Over 40 multidisciplinary clinicians at TWCCH received an X-Waiver, before the waiver requirements were discontinued in 2023. Since 2017, TWCCH has performed intakes on 2,903 individuals with

OUD, have a retention rate of 27%, and are actively treating 781. Additional services have grown to include bidirectional referrals with TWCCH’s Infectious Disease clinic such that addiction patients who test positive for HIV and/or HVC are referred to ID, and ID patients needing addiction services are referred to primary health.

Through addiction medicine integration, with the education done in TWCGME, clinicians are given essential tools to meet and overcome the challenges posed by SUD stigma. The project team is expanding this work to educate and integrate new clinical staff as part of the National Academy of Medicine’s pilot program on addiction medicine core competencies.

Timothy Burke, D.O., FACOI, is board-certified in internal medicine and addiction medicine. Dr. Burke earned his medical degree from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed his residency at The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education where he is also an Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program and Program Director of the Addiction Medicine Fellowship.

References:

1. Weisner, C. M., Chi, F. W., Lu, Y., Ross, T. B., Wood, S. B., Hinman, A., . . . Sterling, S. A. (2016). Examination of the Effects of an Intervention Aiming to Link Patients Receiving Addiction Treatment With Health Care: The LINKAGE Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0970

2. Hostetter M, Klein S. Expanding access to addiction treatment through primary care. Commonwealth Fund. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/ publications/2017/sep/focus-expanding-accessaddiction-treatment-through-primary-care[2] (https://www.commonwealthfund.org/ publications/2017/sep/focus-expanding-accessaddiction-treatment-through-primary-care).

3. Increasing Primary Care Utilization of Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Opioid Use Disorder. Stacey L. GardnerBuckshaw, Adam T. Perzynski, Russell Spieth, Poojajeet Khaira, Chris Delos Reyes, Laura Novak, Denise Kropp, Aleece Caron, John M. Boltri. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine Mar 2023, jabfm.2022.220281R2; DOI: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220281R2

4. https://www.pa.gov/en/agencies/dhs/ resources/mental-health-substanceuse-disorder/substance-use-disorder/ centers-of-excellence.html

Educating trainees in a COE initiative prepares future physicians to, during a PCP visit, support patients who may not have reached out for recovery services otherwise.

With an advertisement in the PSAM Review!

Reach over 15,000 readers directly connected to the addictions treatment, prevention, recovery and education continuum. From frontline specialists and affiliated healthcare practitioners and providers to individuals and families affected by addictions, PSAM Review offers helpful news, trends, insights, and educational editorial in the field of addiction medicine.

Contact sales@hoffpubs.com, or 610-685-0914 x 715, for more information.

by Rebecca Arden Harris, MD, MSc, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

The rapid rise in cocaine and methamphetamine (stimulant) use is a major public health problem in the U.S. In 2023, an estimated 6.9 million Americans used stimulants, with approximately 2.6 million meeting DSM-5 criteria for stimulant use disorder (StimUD). Pennsylvania has been hard hit, with about 267,000 individuals using stimulants in 2023 and 100,000 living with StimUD.1

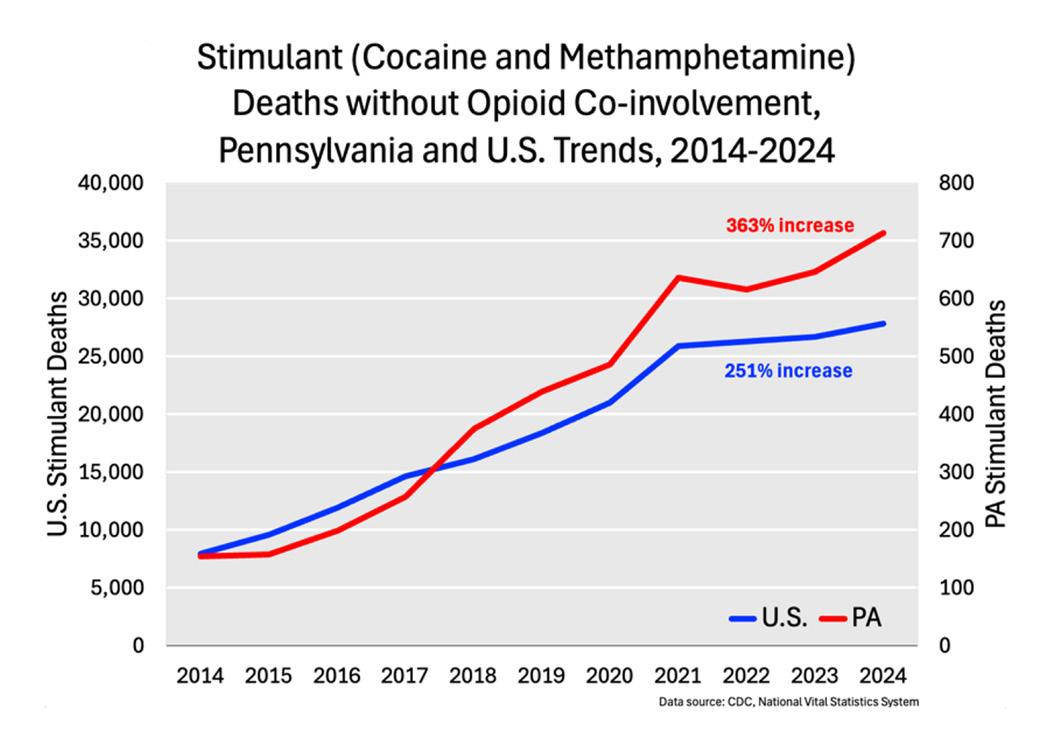

A particularly alarming trend is the sharp increase in stimulantinvolved mortality. Between 2014 and 2023, deaths from stimulant use not involving opioids rose by 251% nationally, and by 363% in Pennsylvania (see Figure). 2 The rising death counts add to an already grim overdose toll, while stimulants’ severe cardiotoxicity drives additional deaths from heart disease.3

There are currently no FDAapproved medications for the treatment of StimUD. In their absence, contingency management (CM) is the first-line treatment and the only behavioral intervention consistently shown to effectively reduce stimulant use. It is recommended by HHS, SAMHSA, NIDA, ASAM/ AAAP, and the VA. Grounded in principles of operant conditioning and behavioral economics, CM uses immediate, tangible rewards to compete with the reinforcing effects of drug use. Programs typically use an escalating reward schedule in which incentives start at a modest amount (for example, $10) and increase incrementally with consecutive drug-negative samples. A missed or positive test resets the incentive to the starting amount, although participants can return to their prior level after a set number of negative samples. This structure reinforces early success, encourages continued reduction or stopping of use, and provides immediate consequences for lapses while maintaining a clear path back to progress. Over time, these incentives are intended to reinforce abstinence and promote stability.

Most treatment programs use a 12-week protocol based on funding constraints and perceived norms rather than evidence about the optimal duration needed to maximize and sustain CM’s effects. Duration matters because CM can produce a “cliff” effect, where the rate of drug-negative urine tests generally increases during treatment but then declines abruptly once incentives end. Extending CM to 24 weeks or more may help maintain momentum and create a “softer landing” when incentives end, although longer programs could risk intervention fatigue and are more expensive. Research is needed to determine whether extended CM improves post-treatment outcomes, for how long, and by how much.

Despite these uncertainties, policymakers are moving forward with longer protocols. In 2023, California launched the country’s first statewide Medicaid CM benefit using a 24-week protocol.4 Delaware, Hawaii, and Washington are exploring similar 24-week programs.5

As states and providers consider CM protocols, several other design choices affect CM’s real-world effectiveness and feasibility: