The High Line Tale

Nguyen Quy Phu

Fra UAS

July 2022

Nguyen Quy Phu

Fra UAS

July 2022

This seminar aims to present a brief history of Europe’s built environment through the lens of recurring renewal and redevelopment. It does so by exemplifying a limited number of concrete places and projects, mostly large scale architectural projects with wider urban impacts, whose common trait is that they all build upon existing conditions. Extensions, renovations, additions, and reconstructions, in short, changes that somehow alter existing building stock will be discussed and analysed within the context of the European city.

This course thus firstly outlines a few - necessarily selective - urban and architectural conditions that are exemplary for European space making. Without ambitions to present a complete picture, we will glance at urban developments during Roman and medieval times, the enlightenment, the modernist era, the post WWII-discourses, and finally rather contemporary notions of urban reinvention.

Secondly, we will portray a few so called masters and their handling of existing building stock. The record of transformations of built space in the work

of several modernists is thereby as telling as that of today’s heavyweights, both in the urban and in the architectural sense. We will discuss their approaches towards the built environment and their intentions for the city.

As a third point of reference we will turn towards the city of Frankfurt and its vicinities. Despite being a relatively small European city, it still offers a fairly comprehensive bricolage of urban situations, sporting highrises next to clear footprints of former city walls, the contested replacement of brutalist with reconstructive developments, and a high degree of suburbanisation, to name but a few.

Finally, every participants will chose one architectural-urban development themselves. We will analyse its respective strategies of spatial design, find appropriate graphic ways to draw its condition and, most importantly, trace its approaches towards context and the implicit question of how to renew and to redevelop the environment it finds itself in.

by Nguyen, Quy Phu

Oftentimes architects and urbanists are driven by an unnegotiable optimism. Following such an attitude, we have seen outcomes of a broad spectrum, from hope to despair. The High Line, interestingly, does not belong precisely to any of the aforementioned categories. It was not an architectural nor urbanist advocation, its neglected wild state was its original appeal. It was all confidence in the beginning. With its growth came the ups and downs, it was challenged and judged, it was the best as much as it was possibly the "worst". It was the symbol of progress as much as it was the villain avocating inequality. These turbulences, these different forces at play, and the multitude of consequences resulting in the original High Line "phenomenon" (2006 - 2014) are of interest to this writing.

The text tells the growing up story of the elevated structure, following its struggle, perseverance, fame, and maturity. Coincidently, guided by optimism still, the High Line tale would be revealed as a story of a happy ending.

I hope you have a good read.

The High Line's inception was implemented out of the turbulent years of New York, from the turn of the new millennium to 2009, from the shattering of the twin towers to the collapse of the housing market, from the flourishing economy of cheap gas and affordable suburban mansions to the rising of homelessness by the thousands, from the mindlessly-spending consumerism to the growing effort for sustainability and equality. Being the first of its kind in the US, seemingly a wholeheartedly community-driven undertaking, promising a generous haven in a car-crowded city, the High Line was the backbone reassuring positive development and change. Since its earliest imagination, this motorized railway turned public park was undoubtedly the sign of a welcoming recovery for West Chelsea. A glimpse of light amidst impending crisis, the High Line, from its incubation to its birth and maturity, could be told as a miraculous urban tale.

The title was given by DETAIL magazine in 2009 for the first opening celebration. "A wonderful place that seems to bring joy to stressed big-city inhabitants", the author reaffirmed. When it wasn't awakened, the High Line was first deadly. The street-level track was known as "Death Avenue" as fatal accidents heightened. Following the rise of New York as a manufacturing city, the today elevated railroad was constructed in 1933 to deliver meat into the district before its quick demise following the succession of trucking. It went full sleeping mode through the 1980s and 1990s, the once highly integrated urban bloodline then an uninvited object cutting through 22 building blocks. After decades of disuse and the subsequent southern amputation for an apartment building, the High Line was expiring. In spite of the demolition sentence in 1999, the execution was on hold as the removal of such a massive assembly was too costly.

The near-death experience turned out to be fateful, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for visionaries who saw a park in the dying industrial remnant. The vandalistic graffiti turned out to be inspiring and the sneaky wilderness was desirable. The thriving feral garden which was taking over the powerful steel and concrete had urged the establishment of "Friends of the High Line", a not-for-profit

conservancy rooted in the vicinity, they would fight for the revival of this derelict monument. In 2004, after numerous case studies and conceptual proposals from the most optimistic minds around the world, 720 ideas from 36 countries, suggesting from a mile-long swimming pool to an unimaginable roller coaster, the High Line had wielded enough life support, the conservancy had achieved its purpose, West Chelsea had won, and New York would have a new public park. The High Line, which used to divide and disturb would then connect and embrace, was excitedly rescued, "no demolition, only add, transform, and reuse".

A new zoning plan was promptly proposed and passed, the neighboring community would have the structure as an oasis. This was the "American dream" of a High Line. "Frog of a railroad to become prince of a park" as it was enthusiastically announced on the New York Times' that-morning front page. The "world" was excited, West Chelsea community was excited, the design of the soon-tobe-so-lively elevated greenway would be selected through a competition among the most famous architects and landscape designers.

James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio plus Renfro along with Piet Oudolf were appointed to perform the magic. The once vital urban infrastructure would revive gloriously in the form of an extraordinary park.

The operation took eight years to complete, from south to north, beginning in 2006 and concluding in 2014, bridging and patching neighborhoods as it grew, introducing more and more public amenities in each opening. Much hardship had gone by, the High Line's proven endurance, and its will to live were witnessed, its life story so far had touched everyone's heart. The community had received their long-waited parkland. The "world" found satisfaction in the unfolding of this infrastructural sensation, as remarked by the city council speaker, "a miracle of perseverance".

At last.

Tracks were made into promenades and the wilderness had grown into a lush paradise of more than 500 flourishing plant species. The once noisy path of motorized machinery was then occupied by happy slow relaxed people. The hurried New York suddenly seemed distant away.

Floating nine meters above the street, dawn to dust were experienced differently. Overlooking the 10th Avenue from the new amphitheater was unexpectedly thrilling. Manhattan appeared to be magical for mysterious reasons. A passionate reporter did even argue that only here one could find the best views of their city.

The High Line had become an oasis of life and leisure. This hanging garden running in parallel with the waterscape had become the Hudson's finest companion. On the revived park, water and plant came in harmony with the cityscape. New York was as beautiful as it could ever be.

If only the fairy tale could close with "meatpackingdistrict residents lived happily ever after", if only the storytelling suspended at the moment of the wonderful rebirth, the High Line would be the beloved child without controversy.

Anyhow, the magic has its repercussion.

As though the elevated park had championed a talent show for its eventful childhood, everyone wanted to be a part of it. Its radiance, the High Line's halo, was on the bucket list of every tourist. Subsequently in the following years, similar to a hastily-rose-to-fame celebrity, the High Line's character was promptly diverted and challenged.

In 2014, approximately 13 thousand people flocked the oasis daily. The number quickly escalated to 21 thousand per day a year later, among which merely six percent were from the proximity, the community felt being pressured out of their hardfought garden.

Ignited by the introduction of the iPhone and the booming digital age, the rail-to-trail park was only to please instant gratification. The modern landscape, to everyone's surprise, wasn't for serenity but internet photos and strutting fashion models.

The young star of infrastructure, the social equity-based project had turned into a "touristclogged catwalk", borrowing the expression from a local, "was this a park or a museum?", as the infrastructure's fundamental intention was brought into question.

In the city where wealthy-exclusive developments were advancing, in an area where everyone had less than 1m2 of tree canopy, this precious green public bridge was the community's desperate battlefront and they were losing it. The urban tale seemed undermined, the High Line was then an easily-crowded 2.3km "Disneyland on the Hudson".

With the maintenance expense of 125 thousand dollars per km2, fifty times higher than a comparable New-York-City park, the High Line had surpassed its intended friendly-neighborhood garden. The elevated structure had become a fancy development, a luxury commodity that seemed to welcome only corresponding affluent residents. By 2011, 29 new constructions and 2 billion dollars of investment had flowed into the district. The poor neighborhood had erupted with unprecedented financial recovery. As crowds invaded the generous promenade, views to the Hudson were also filled plot-to-plot by the most extravagant but clearly outof-town works of architecture. Thought to be an oasis where nature and the city came in harmony, the High Line was then a showroom of the shiniest fancy developments.

Once an area of drug-to-crime reputation and poor economic position, the updated zoning in 2005 together with the revived park had made the district into a well-off neighborhood. The economic windfall, however, was catering specifically to the new rich, with tech offices, high-class art galleries, million-dollar condos, and so on. The grassroots community was ignored and dumbfounded.

Originally a down-to-earth area of blue-collar immigrants, longtime locals were either priced out of their apartments or struggling to cope with the skyrocketing living cost. Old age businesses were dying out paving the way for capital-craving global chains, as "Western Beef supermarket turned into Apple store", and "the pizza place into an eyebrow salon". The irresistible inflow of money had led to the decay of the old district. The elevated park had indirectly made West Chelsea another downtown of New York, overpriced and unauthentic.

Some feared displacement, some were angered and felt betrayed. The High Line, behind its delightful appearance, was alienated, stranded from its own community. The revived park, instead of the promised hopes and dreams, was indicating the typical superimposing project of systemic inequality.

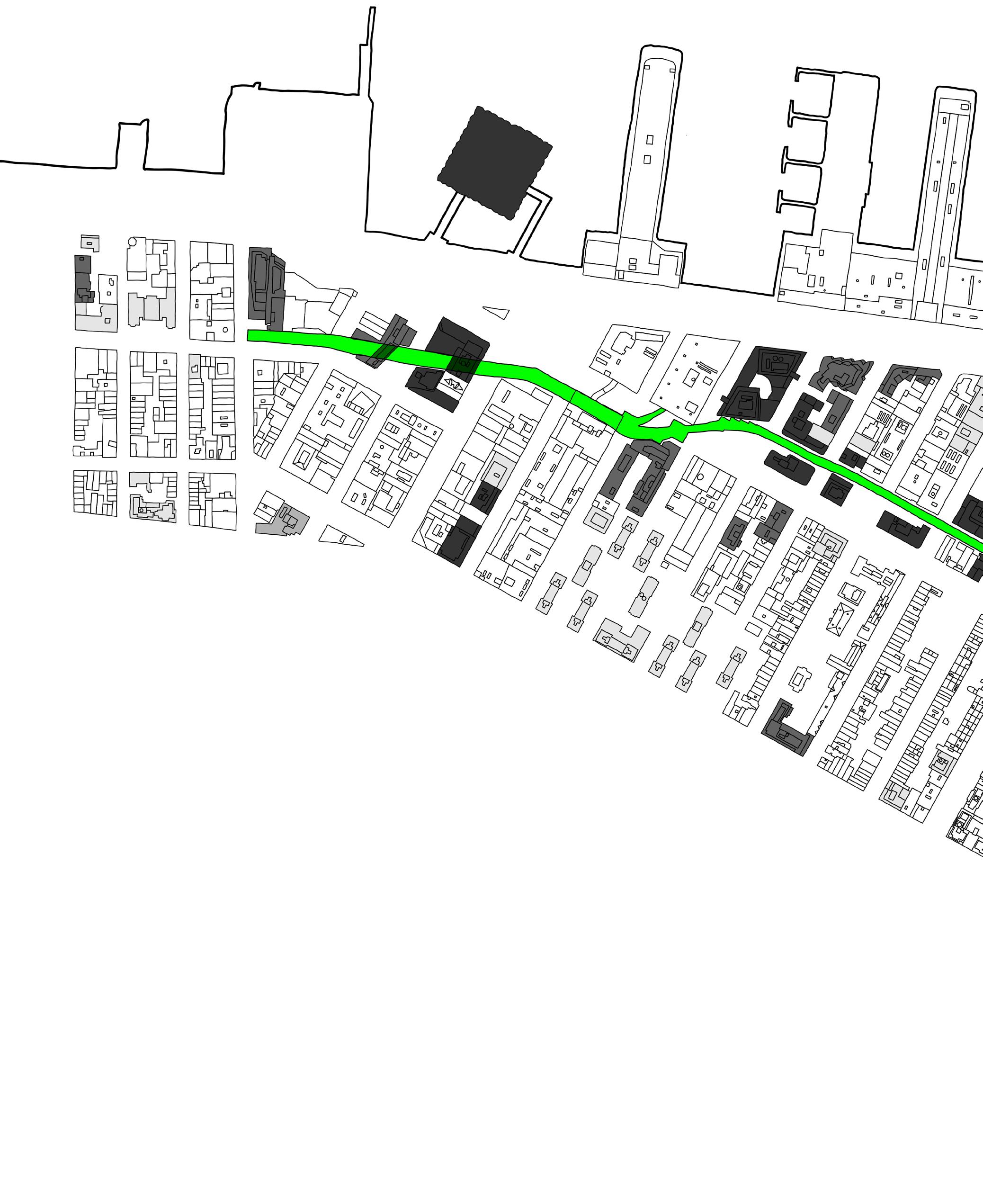

Urban bloodline / Before 1950

Decline to decay / 1951 - 1999

Incubation / 2000 - 2005

Rebirth and Youth / 2006 - 2014

Maturity / 2015 - 2022

200m

The High Line was seemingly devoured by its own success, its positive vibe had only damaging ripples, its enchanting qualities were harder to appreciate, and the rallying effort was after all counterproductive. Local residents found themselves in a worse spot before the magical revival. Out-of-towners invaded their centrallylocated open space, alien investments eroded their "belonging" atmosphere, and the neighborhood was growing apart.

However, the High Line's popularity also brought more attention to its dilemma. The heated problems rooted not only in the vicinity but in the whole US were made better aware, from inflation to gentrification, from inequality to urban inaccessibility.

A blessing in disguise, the High Line conflict as well as its extensive implications were then in broader daylight.

For the two visionaries who first envisioned a park in the dying urban relic, it was troubling experiencing the full outcome of their success. "Ultimately, we failed", they regretfully admitted. In their defense, it would be too bold to foresee that an outdated rail bridge could be the most attractive destination in the famous New York. It would be too wild to imagine that the meatpacking district could be among the fastest in recent city history hotspot of gentrification. As impossible as it sounds, the High Line "phenomenon" had happened. The urban oasis had become so much more than its founders' wildest dream.

Because of the undeliberate success, the High Line can't be the lone offender of the lateral social damage. Considering the quantitative rise of exclusive developments in the whole city, one could better blame the new mayor for his "over" pro-progress attitude. But that wouldn't be fair either since his policy was needed in the 2010s, as "New York's future was not guaranteed" and people were afraid that Wall Street would leave town. The quick remedy was then found in the small but consistent effort toward the grassroots community. Reserved time slots were introduced, and localtailored activities were better advocated.

Classes were held in the thriving garden for nearby children's plant-to-insect exploration. Teenagers from the proximity were invited to paid-training

programs securing their participation in the district's future. Small businesses were receiving the necessary attention and a new wave of customers. Investors were also fervently encouraged to have 20% of their buildings for affordable housing.

As surprising as its success, the High Line's redemption was partly found in the recent global pandemic.

Since tourism was disrupted, the structure finally had its time to mature and became the friendlyneighborhood garden that it had long promised. After a short closure in 2020, locals once again found peace in the idyllic park. Even though they were much rarer, panoramas to the Hudson could still move the beholders.

But beauty was never its problem anyways. Learning from the social mistakes, "The High Line network" was also established. Aiming to bring green space and potential investment to forgotten towns. Apart from the nuts-and-bolts topics, the network would push for the discussion of equity, inclusivity, and accessibility. By the time this story is written, the High Line had changed substantially from the first imagined oasis. Its 2015 problems are dwarfed in the sight of "Trump presidency", the struggle of humans and nature globally, and more recently the threat of an all-out nuclear war. As it seems to signify, perhaps the structure can't be the singular savior of its extended complex situation. Perhaps every problem is interconnected and the solution to the High Line's local challenge is not in its proximity but should be found in the global context, meaning only by promoting a better world, West Chelsea would eventually become a better place.

Starting with a singular derelict structure, this tale is now ending with more than 60 planned and initiated urban-greenification projects across the globe. The High Line phenomenon has resulted in the High Line Network. As the elevated park has positively influenced the mission for sustainability and urban livability globally, the story feels that it should end here without a definite conclusion. The beautiful world tomorrow, which is certainly inspired by this amazing park, would be the true outcome of the High Line story, and that is the happy ending of this miraculous urban tale.

The end.

'High Line' 2022. Wikipedia, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Line>.

Friends of the High Line 2022, 'High Line'. High Line, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://www. thehighline.org/>.

Pickhardt, Stephen 2022, 'High Line Map and Visitor Guide'. Free Tours By Foot, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://freetoursbyfoot.com/high-linemap/>.

Madlener, Thomas 2009, 'Awakened Infrastructure: The High Line in New York'. Detail, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://www.detail.de/ en/de_en/awakened-infrastructure-the-high-linein-new-york-13738>.

Michelle Poh Ern Ling 2013, 'High Line Architecture'. Off-Shore Studio Adaptive Reuse NYC Architecture, accessed 17 May 2022, <http://cargocollective.com/Uofanycstudioarch/ HIGH-LINE-ARCHITECTURE>.

Friends of the High Line 2009, 'High Line Map/ Info'. 1046.pdf, accessed 17 May 2022, <https:// www.solaripedia.com/files/1046.pdf>.

Arquitectura Viva 2022, 'High Line City Walk, New York'. Arquitecturaviva, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/paseourbano-high-line-nueva-york-4>.

Area 2016, 'High Line'. Area, accessed 17 May 2022, <https://www.area-arch.it/en/high-line-2/>.

Quintana, Mariela 2016, 'Changing grid: Exploring the Impact of the High Line'. Street Easy Reads, accessed 19 May 2022 <https://streeteasy.com/ blog/changing-grid-high-line/>.

Barbanel, Josh 2016, 'The High Line's ‚Halo Effect on Property'. Mansion Global, accessed 19 May 2022 <https://www.mansionglobal.com/articles/ the-high-line-s-halo-effect-on-property-36023>

Boodan, Ien 2016, 'The High Line: A Case Study'. Issuu, accessed 23 May, 2022 < https://issuu. com/ienboodan/docs/case_study>

American Society of Landscape Architects 2022, 'Honor Award - The High Line, Section 1'. 2010

Asla Professional Awards, accessed 24 May 2022, <https://www.asla.org/2010awards/173.html>.

Moss, Jeremiah 2012, 'Disney World on the Hudson'. The New York Times - Opinion, accessed 27 May 2022 < https://www.nytimes. com/2012/08/22/opinion/in-the-shadows-of-thehigh-line.html>

Pogrebin, Robin 2009, 'Renovated High Line Now Open for Strolling'. The New York Times, accessed 27 May 2022 <https://www.nytimes. com/2009/06/09/arts/design/09highline-RO.html>

Mc Phearson, Timon 2020, 'Urban green space area (m2) per NYC inhabitant'. ResearchGate, accessed 09 June 2022 <https://www. researchgate.net/figure/Urban-green-space-aream2-per-NYC-inhabitant_fig1_343928429>

Nashed, Mirna 2018, 'The Gentrification of West Chelsea'. NYCropolis, accessed 14 June 2022 <https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/vellon18/ gentrification/mirnanashed/the-gentrification-ofwest-chelsea/>

Great Museums 2014, 'Great Museums: Elevated Thinking: The High Line in New York City'. Youtube video, accessed 14 June 2022 <https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=7CgTlg_L_Sw>

Bliss, Laura 2017, 'The High Line's Next Balancing Act'. Bloomberg, accessed 17 June 2022 <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2017-02-07/the-high-line-and-equity-inadaptive-reuse>

Higgins, Adrian 2020, 'The High Line has been sidelined. When it reopens, New Yorkers may get the park they always wanted'. Washington Post, accessed 20 June 2022 <https:// www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/home/ the-high-line-has-been-sidelined-when-itreopens-new-yorkers-may-get-the-park-theyalways-wanted/2020/06/23/5e2a59e0-acd1-11ea94d2-d7bc43b26bf9_story.html>

NYC Open Data 2022, 'Building Footprints'. NYC Open Data, accessed 30 June 2022 <https:// data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/ Building-Footprints/nqwf-w8eh#revert>

The New York Times 2013, 'Before and After Bloomberg'. the New York Times, accessed 14 June 2022 <https://archive.nytimes.com/www. nytimes.com/interactive/2013/08/18/nyregion/ before-and-after-bloomberg.html>

River LA 2022, 'The High Line Network Member'. River LA, accessed 30 June 2022 <https://www. riverla.org/high_line_network_member>

Routhier, Giselle 2019, 'State of Homeless 2019'. Coalition for the homeless, accessed 08 June 2022 <https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/ state-of-the-homeless-2019/>

The City of New York 2022, 'Trees Count! 2015-2016 Street Tree Census'. New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, accessed 09 June 2022 <https://www.nycgovparks.org/trees/ treescount>

NBC New York 2020, 'NYC Jobs Recovery Could Take 4 Years, Budget Office Says'. NBC New York, accessed 01 July 2022 <https://www. nbcnewyork.com/news/local/nyc-jobs-recoverycould-take-4-years-budget-office-says/2423483/>

Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences

2022