Concepts Methods Connections Divakaran P.P.

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/x98-the-x9c-mathematics-of-india-concepts-methodsconnections-divakaran-p-p/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Mathematics for Physicists Introductory Concepts and Methods Alexander Altland

https://textbookfull.com/product/mathematics-for-physicistsintroductory-concepts-and-methods-alexander-altland/

Connections in Discrete Mathematics A Celebration of the Work of Ron Graham 1st Edition Steve Butler

https://textbookfull.com/product/connections-in-discretemathematics-a-celebration-of-the-work-of-ron-graham-1st-editionsteve-butler/

Forging Connections in Early Mathematics Teaching and Learning 1st Edition Virginia Kinnear

https://textbookfull.com/product/forging-connections-in-earlymathematics-teaching-and-learning-1st-edition-virginia-kinnear/

Introductory Concepts for Abstract Mathematics Kenneth E. Hummel

https://textbookfull.com/product/introductory-concepts-forabstract-mathematics-kenneth-e-hummel/

Forging Connections between Computational Mathematics and Computational Geometry Papers from the 3rd International Conference on Computational Mathematics and Computational Geometry 1st Edition Ke Chen

https://textbookfull.com/product/forging-connections-betweencomputational-mathematics-and-computational-geometry-papers-fromthe-3rd-international-conference-on-computational-mathematicsand-computational-geometry-1st-edition-ke-che/

Concepts of epidemiology : integrating the ideas, theories, principles, and methods of epidemiology 3rd Edition Bhopal

https://textbookfull.com/product/concepts-of-epidemiologyintegrating-the-ideas-theories-principles-and-methods-ofepidemiology-3rd-edition-bhopal/

Animal behavior: concepts, methods, and applications

Second Edition Nordell

https://textbookfull.com/product/animal-behavior-conceptsmethods-and-applications-second-edition-nordell/

Lost Connections Johann Hari

https://textbookfull.com/product/lost-connections-johann-hari/

The Capability Approach, Empowerment and Participation: Concepts, Methods and Applications David Alexander Clark

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-capability-approachempowerment-and-participation-concepts-methods-and-applicationsdavid-alexander-clark/

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences

P. P. Divakaran

The Mathematics of India

Concepts, Methods, Connections

SourcesandStudiesintheHistoryofMathematics andPhysicalSciences

ManagingEditor

JedZ.Buchwald

AssociateEditors

A. Jones

J.L ¨ utzen

J.Renn

AdvisoryBoard

C.Fraser

T.Sauer

A.Shapiro

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences was inaugurated as two series in 1975 with the publication in Studies of Otto Neugebauer’s seminal three-volume History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy, which remains the central history of the subject. This publication was followed the next year in Sources by Gerald Toomer’s transcription, translation (from the Arabic), and commentary of Diocles on Burning Mirrors. The two series were eventually amalgamated under a single editorial board led originally by Martin Klein (d. 2009) and Gerald Toomer, respectively two of the foremost historians of modern and ancient physical science. The goal of the joint series, as of its two predecessors, is to publish probing histories and thorough editions of technical developments in mathematics and physics, broadly construed. Its scope covers all relevant work from pre-classical antiquity through the last century, ranging from Babylonian mathematics to the scientific correspondence of H. A. Lorentz. Books in this series will interest scholars in the history of mathematics and physics, mathematicians, physicists, engineers, and anyone who seeks to understand the historical underpinnings of the modern physical sciences.

Moreinformationaboutthisseriesat http://www.springer.com/series/4142

P. P. Divakaran

The Mathematics of India

Concepts, Methods, Connections

P. P. Divakaran (emeritus) Kochi, Kerala, India

This work is a co-publication with Hindustan Book Agency, New Delhi, licensed for sale in all countries in electronic form, in print form only outside of India. Sold and distributed in print within India by Hindustan Book Agency, P-19 Green Park Extension, New Delhi 110016, India. ISBN: 978-93-86279-65-1 © Hindustan Book Agency 2018.

ISSN 2196-8810

ISSN 2196-8829(electronic)

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences

ISBN 978-981-13-1773-6 ISBN 978-981-13-1774-3(eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1774-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018949905

© Hindustan Book Agency 2018

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. The registered company address is: 152 Beach Road, #21-01/04 Gateway East, Singapore 189721, Singapore

Preface

sadasajj˜n¯asamudr¯atsamuddhr . tam . brahman . ah . pras¯adena

sajj˜n¯anottamaratnam may¯animgnam svamatin¯av¯ a

(Aryabhat . ıya,Golap¯ada 49)

Thereisagoodcasetobemadethatthestudyofthetraditionalmathematical cultureofIndiahasnowattainedalevelofmaturitythatallowsustobegin thinkingofgoingbeyondjustthedescriptionofitsmainachievements–theorems,constructions,algorithms,etc.–toattemptsatasyntheticaccountof thattradition.Ideally,thescopeofsuchaprojectshouldincludenotonlythe unifyingmathematicalideasandtechniquesholdingitalltogether,butalso theirplaceinthecontextofIndianhistoryandIndianintellectualconcerns. Itspracticalrealisationwillrequiremanydifferentskillsandtalentsandisobviouslyataskforothertimesandotherpeople.Themoremodestaimofthe presentbookistotryandputtogetherinapreliminarywaywhatwealready knowfromestablishedsources,inthehopeofdrawingafirstoutlineofitslocationwithintheuniverseofmathematicsaswellas,toalimitedextent,inthe Indianintellectualandculturalethos.

ThelongandcontinuoushistoryofthemathematicaltraditionofIndia wasbroughttoanabruptendinthe17thcentury.Itwasrediscovered–i.e., cametothenoticeofinterestedscholarsoutsidethenarrowcirclesofprofessionalIndianastronomers(andastrologers)andmathematicians–sometwo centurieslater.Manyhavecontributedsubsequentlytothebroadeningand deepeningofourknowledgeandunderstandingofit.Butareasofignoranceremained,ofwhichthemostseriousandsurprisingwastheastonishinglyoriginal andpowerfulmathematicscreatedbyMadhavaandhislonglineofintellectual heirsinasmallcornerofKerala,justbeforethearrivalofEuropeancolonial powersonitsshores.Recentworkhasbeguntofillseveralsuchgapsandpart oftheaimsofthisbook(asthefootnoteswilltestify)istogivedueweightto theresultsofthenewscholarship.Twoparticularthemesareworthyofspecialmentionhere.ThefirstreferstowhatIhavealreadyinvokedabove:itis withameasureofdisbeliefthatonerealisesthatMadhava’snamewaslargely unknowntomodernhistoriansofmathematicsaslateasthirtyorfortyyears ago(andthattheonlytranslationsofworksbyhisfollowers,threeintotalso far,arenotmorethanadecadeold).Soitisnatural,forbothhistoriographic

andpurelymathematicalreasons,thatIshouldpayparticularattentiontothe workoftheschoolMadhavafoundedandtheattendanthistoricalandsocial circumstances.

Theotherareaofdarkness–perhapsthemostresistanttoillumination –onwhichcurrentresearchisbeginningtothrownewlighttouchesonthe quotationattheheadofthispreface(anEnglishtranslationwillbefoundin Chapter6.4),namelythelong-heldnotionthatmathematiciansinIndiaarrivedattheirinsightsinmysteriouswaysthataredifferentfromhow‘everyone else’didit.Aryabhata,asanyonewhohasreadhimshouldhaveknown,had nodoubts:the“bestofgems”thatistrueknowledgecanbebroughtupfrom “theoceanoftrueandfalseknowledge”onlybytheexerciseofone’sintellect, bymeansof“theboatofmyownintelligence”.Othershavesaidthesamein lesspoeticlanguage.Thefirstvindicationsofthisringingendorsementofthe rationalmind,throughthereconstructionoftheactualproofsanddemonstrations,areanothergainfromthecurrentanalyticalstudies.Ihavethoughtit essentialthereforetoprovidecomplete–thoughnotalwayselaborate–proofs ofmostofthesignificantresultsinmodernnotationandterminology,either asdirecttranscriptionsorbyconnectingtogetherpartialinformationavailable indifferenttexts.Thehopeisthatwecanbegintochipaway,littlebylittle, attheencrustedlayersofthemythology–and,occasionally,ill-informedbias –thatstillhassomecurrency:thatIndianmathematicswas,insomestrange andexoticway,notquiteofthemainstream.Ifthisbookhasanoverriding message,itisthat,conceptuallyandtechnically,theindigenousmathematics ofIndiaisinessencethesameasofothermathematicallyadvancedcultures–howcanitbeotherwise?–andthatitsqualityistobeadjudgedbythesame criteria.

Innavigatingtheoceanoftrueandfalsehistoricalknowledge–anissue thathasaspecialrelevanceintoday’sIndia–Ihavehad(unlike,itgoes withoutsaying,Aryabhata)thegeneroushelpofmanymentors,colleagues andfriends.ButbeforeallofthemmustcomethelateK.V.Sarmawhose work,morethananyoneelse’s,helpedplaceMadhavaamongthemathematical greatsofalltime,andnotonlyofIndia:afortuitousmeetingwithhim whilehewastranslating Yuktibh¯as . a wasthesparkthatfirstlitmyinterest inthesubject.Amongthemanyotherswhosustaineditbysharingtheir expertiseorinotherwaysareRonojoyAdhikari,KamaleswarBhattacharya, ChandrashekharCowsik,NareshDadhich,S.G.Dani,Pierre-SylvainFilliozat, KavitaGangal,RanjeevMisra,VidyanandNanjundaiah,RoddamNarasimha, T.Padmanabhan,A.J.Parameswaran,Fran¸coisPatte,SitabhraSinha,N. K.Sundareswaran, .Aspecialwordofappreciationandgratitudeisdue toBhagyashreeBavare,mycollaboratorandconsultantinmattersSanskritic, aswellastoSamirBoseandN.G.(Desh)Deshpandewhoreadthebook indraftformandmademanyvaluablesuggestions.Aboveall,thisbook andIowemuchtofouroldfriends:S.M.(Kumar)Chitreforhisfaithand encouragementatatimewhentheywereneeded;DavidMumfordwithwhom Ihavehadmanystimulatingexchangesaboutthecontentandcontextofthe

mathematicsofIndia;M.S.Narasimhanwhoseinsightsintowhatonemay calltheuniversalmathematicalmind,freelysharedoveralongtimenow, havecontributedgreatlytomyunderstandingofitsIndianmanifestation; andthelateFritsStaalwhosebroadvisionofIndia’sintellectualheritagehas stronglyinfluencedmyownthinking.Institutionalsupportandhospitality atvarioustimesinthepreparationandwritingofthebookcamefromthe InstituteofMathematicalSciencesinChennai,theDAE/MUCentreof ExcellenceintheBasicSciencesinMumbai,theInter-UniversityCentrefor AstronomyandAstrophysicsinPuneandtheNationalCentreforBiologicalSciencesoftheTataInstituteofFundamentalResearchinBengaluru. Finally,IamhappytoacknowledgeheremygratitudetotheHomiBhabha FellowshipsCouncilforchoosingmeseveralyearsagoforaSeniorAward, whicheventwasthetriggerthatsetofftheideaofputtingitalldownonpaper.

P.P.Divakaran

February2018

4.4OtherRealisations........................108

4.5TheChoiceofaBase......................111

5NumbersintheVedicLiterature 113

5.1Origins..............................113

5.2NumberNamesinthe Rgveda .................117

5.3InfinityandZero .........................122

5.4EarlyArithmetic.........................130

5.5Combinatorics..........................135 IITheAryabhatanRevolution

6From500BCEto500CE 143

6.1OneThousandYearsofInvasions................143

6.2TheSiddhantasandtheInfluenceofGreekAstronomy...148

6.3 Aryabhatıya –AnOverview...................157

6.4WhowasAryabhata?......................160

6.5TheBakhshaliManuscript:WhereDoesitFitin?......167

7TheMathematicsofthe Ganitap¯ada 175

7.1GeneralSurvey..........................175

7.2TheLinearDiophantineEquation– kut . t . aka ..........184

7.3TheInventionofTrigonometry.................190

7.4TheMakingoftheSineTable:Aryabhata’sRule.......198

7.5Aryabhata’sLegacy.......................202

8FromBrahmaguptatoBhaskaraIItoNarayana 213

8.1MathematicsMovesSouth...................213

8.2TheQuadraticDiophantineProblem– bh¯avan¯ a ........221

8.3MethodsofSolution– cakrav¯ala ................226

8.4ADifferentCircleGeometry:CyclicQuadrilaterals......236

8.5TheThirdDiagonal;Proofs.. .................248

IIIMadhavaandtheInventionofCalculus 255

9TheNilaPhenomenon 257

9.1TheNilaSchoolRediscovered..................257

9.2MathematiciansintheirVillages–andintheirWords....263

9.3TheSanskritisationofKerala..................276

9.4WhowasMadhava?...andNarayana?............282

10NilaMathematics–GeneralSurvey 291

10.1ThePrimarySource: Yuktibh¯as¯a ................291 10.2GeometryandTrigonometry;AdditionTheorems.......297 10.3TheSineTable;Interpolation..................302 10.4 Sam . sk¯aram:GeneratingInfiniteSeries

11The π Series 313

11.1CalculusandtheGregory-LeibnizSeries............313 11.2TheGeometryofSmallAnglesandtheirTangents......316 11.3Integration:ThePowerSeries..................320 11.4IntegratingPowers;AsymptoticInduction ...........323 11.5TheArctangentSeries......................327

12TheSineandCosineSeries 331 12.1FromDifferencestoDifferentials................331 12.2SolvingtheDifference/DifferentialEquation ..........336 12.3TheSphere ............................342 12.4TheCalculusDebates......................348

13The π SeriesRevisited:AlgebrainAnalysis

14WhatisIndianabouttheMathematicsofIndia? 381 14.1TheGeographyofIndianMathematics............381 14.2TheWeightoftheOralTradition...............387 14.3GeometrywithIndianCharacteristics.............393

15WhatisIndian...?TheQuestionofProofs

15.1WhatisaProof?.........................399 15.2No ReductioadAbsurdum

15.3Recursion,DescentandInduction

16 Upasam . h¯ara

16.1TowardsModernity.......................413 16.2Cross-culturalCurrents?.....................416 16.3Journey’sEnd..........................419

Introduction

0.1ThreeKeyPeriods

Thisbookhasfourparts.Thefirstthreecorrespondtochronologicaldivisions ofthelonghistoryofmathematicalworkdoneinIndiawhilethelastpartisa bringingtogetheroftheunifyingideasandtechniquesthatrunthroughthat history.Twoofourthreehistoricalperiodsareobligatorychoices:theverybeginningofmathematicalthoughtintheVedicage(earlierthanca.500BCE) asfaraswecantellfromavailablerecords,andthelastphase(endingca.1600 CE)whichis,naturally,muchbetterdocumented.Itisaremarkablefactthat theenddidnotcomeasaslowfadingawaybut,onthecontrary,wasrelatively abruptfollowingaperiodofblazingglory;soitisdoublyworthyofadetailed study.Betweenthebeginningandtheendisamiddleorclassicalperiodspanningroughlythetwocenturiesstartingaround450CEwhich,asithappens, isalsoofpivotalimportance.ThisistheperiodofAryabhata(Aryabhat . a) andBrahmagupta,oneinwhichtheVedicmathematicallegacywasradically transformed.

Asinallancientmathematicalcultures,soinIndia:mathematicsbegan withlearninghowtoenumeratediscretesets(counting)andhowtocreatesimpleplanarfigures(drawing).Theformertooktheformofdecimalenumeration andledinduecoursetoarithmeticandthelattertoafairlyelaborategeometry,primarilyofthecircleandoffiguresassociatedwiththecircle.Historically, thesefirstawakeningsofthemathematicalspiritspantheVedicagebeginning, say,around1,200BCEifwegobytextualevidencealone.Thereare,however, intriguingglimpsesofanearlierfamiliaritywithsomeoftheVedicgeometry inthearchaeologicalremainsoftheIndusValley(orHarappan)civilisation, goingbacktothemiddleofthe3rdmillenniumBCEoralittleearlier.What iscertainisthatthebasicprinciplesofbothdecimalarithmeticandgeometry wereprettywellinplaceatleastbythetimeofthecompositionoftheearliestofthearchitecturalmanualscalledthe ´ Sulbas¯utra,ca.800BCE,possibly somewhatbeforethat.Wedonothavemuchinformationonthefurtherdevelopmentofgeometryforalongtimeafter,infactuntiltheclassicalperiod.But theconsequencesoftheideaofmeasuringanumber(Iuse‘number’without qualificationtomeanapositiveinteger),nomatterhowlarge,bymeansof thebase10,inotherwordsdecimalplace-valueenumeration,continuedtobe

vigorouslyexploreduntilthebeginningofthecommoneraandbeyond.Historiansareoftheviewthatduringthisperiod,theVedicpeoplewereinthe processofsettlingtheGangeticplain,settingoutfromtheupperIndusregion andworkingtheirwaygraduallytowardstheeast.

Theclassicalperiod,whichgotitschiefimpetusfromastronomicalinvestigations,ischaracterisedbyseveral‘firsts’.Tobeginwith,astronomyitself becameascience:themotionofheavenlybodiescametobestudiedasthe changeinthegeometrydefinedbythem,consideredaspointsinspace,with thepassageoftime.Therequiredgeometrywasseentoneedareformulation andrefinementofthatinheritedfromVedictimes.Simultaneously,thereconciliationoftimemeasurementsmadeusingthelunarandsolarperiodsled toproblemsrequiringthesolutionofalgebraicequationsinintegers(andof course,first,aproperalgebraicformulationofsuchequationsandtheirproperties).Circlegeometrybecamegreatlysophisticated,goingbeyondtheneedsof astronomy.Alsofromthisphasewehavethefirsttextsconcerningthemselves exclusivelywithmathematicsandastronomywhichare,moreover,attributable tohistoricallyidentifiableauthors:Aryabhatafirstandforemost,followedalittleoveracenturylaterbyBrahmaguptaandBhaskara(Bh¯askara)I.Forthose whoknowevenalittleaboutthestoryofmathematicsinIndia,thementionof thesenamesisenoughtoindicatethesignificanceofthisperiodforeverything thatcamelater.IndeeditisnotanexaggerationtosaythatallofthesubsequentworkinastronomyandrelatedmathematicsinIndiaisanelaborationof theconceptsandtechniquesfirstformulatedduringthistime.

Thegeographicallocusofmathematicalactivityduringthismiddlephase wasfairlywidelydistributedwithinnorthernIndia;Aryabhatadidhisworkin Magadha,partofmodernBihar,whileBrahmaguptaisthoughttohavelived inMalava(M¯alava),theregionaroundUjjain(Ujjayini).

Mythirdchronologicaldivisioncorrespondsalsotoageographicaldivision anditisdefinedentirelybytheachievementsofMadhava(M¯adhava).Madhava andalonglineofhisdiscipleslivedandworkedinthelowerbasinoftheriver Nila(Nil.a)incentralKeralaandtheyremainedproductivefortwocenturies,ca. 1,400-1,600CE.ItisbyfarthebestdocumentedphaseofIndianmathematical history.Despitethat,ithastakenalongtimeformodernscholarstogofrom relativeignorancetopuzzledadmirationtoaninformedappreciationofthe brillianceandoriginalityoftheachievementsofthislastphase.

ThecentralconcernoftheNilaschool1 wastheconceptualisationandexecutionofamethodofdealingexactlywithgeometricalrelationshipsinnonlinear problems,specificallyproblemsofrectificationandquadratureinvolvingcircles

1 Thenameismeanttoconveynotonlythethematiccoherenceofthemathematicsit producedbutalsoitslocalisationinaclusterofvillagesallwithineasywalkingdistanceof eachother.OtherdesignationssuchastheKeralaschoolandtheAryabhataschoolareusedby someauthors.Thefirstignoresthefactthattherewasashortlivedbutvibrantastronomical researchcentreelsewhereinKeralainthe9thcenturyCE.AsforinvokingAryabhata’sname todescribetheirwork,almostallofIndianmathematicsfromthe6thcenturyonwardscan withjusticebecalledtheAryabhataschool.

andspheres,byresortingtoaprocessof‘infinitesimalisation’throughdivision byunboundedlylargenumbers.Inotherwords,thefundamentalachievement ofMadhavaandtheNilaschoolwastheinventionofcalculusfortrigonometric functions(aswellas,alongtheway,forpolynomials,rationalfunctionsand powerseries).TherootsoftheNilaworkgodirectlybacktoAryabhata,skippingovermuchofwhathappenedinbetween,and,inaveryrealsense,it representsthecomingtogetherofthetwomainstrandsoftheearliertradition, geometry(ofthecircleandassociatedlinearfigures)andbased(decimal)numbers.Intheprocess,itsharpenedanddeepenedalgebraicmethodstraceable inaformalsensetoBrahmagupta,definedandmaderespectableentirelynew typesofmathematicalobjects(infiniteseries)andintroducedmethodsofproof (mathematicalinduction)unknowntillthen.

Onewouldexpectatimeofsucheffervescenceandcreativitytobefollowedbyaperiodofconsolidationandsteadyprogress.Butthatisnotwhat happened.TheNilaschoolmarksthefinalepisodeinthelongandessentially autonomousprogressionofmathematicalthoughtinIndia.Littleofanyvalue ornoveltyemergedafterthe16thcenturyinKeralaorindeedinIndiaasa whole.Quiteafewreasonshavebeenputforwardforthedecline–itisnot everycenturythatproducesaMadhava–butitcannotbedoubtedthatthe immediatetriggerwasthearrivalofPortuguesecolonialismontheshoresof Kerala.

Thechoiceofthethreeepochsthatwearegoingtoconcentrateonisthus notrandom.Historicallyandintermsofmathematicalimpact,theyrepresent thehighestofhighpointsinalongevolution.Whatofthegaps–each,coincidentally,ofaboutathousandyears,giveortakeacenturyortwo–thatseparate them?Byandlarge,theyservedasperiodsofsteadyifunspectacularadvances. Therewereofcourseverymanyfinemathematiciansandastronomers,especiallybetweenthemiddleandthefinalphases,whodonotfitintoouroverneat division,themostoutstandingbeingtheversatileandprolificBhaskaraII. Theircontributionswerehandsomelyacknowledgedbythosewhocamelater andwillfigureinouraccount–BhaskaraIIinparticularhadanenormous influenceandhis L¯ıl¯avat¯ ı isprobablythemostpopularmathematicaltextever writteninIndia.Thehopeisthatwhatemergesattheendisawell-rounded portraitofmathematicswithintheboundariesofculturalIndia–whichrarely coincidedwiththevariouspoliticalIndiasofkingsandempires–andoverits recordedhistory.Theinformedreaderwilljudgehowwellthehopeisrealised. IntheshortconcludingpartIhavetriedtofleshoutthesenseofcontinuity andunityinthemathematicalcultureofIndia,alreadyvisibletotheenquiring eyeinthefirstthreeparts,bygatheringtogethersomeofthecommonstrandsof thoughtandmethodthatrunthroughitall.Theyrelatetofoundationalissues aswellastothespecificmeansemployedtogetspecificresults-infactthetwo aspectsaresoinextricablyjoinedthattheyappeartobedifferentexpressionsof anall-pervasivecommonmodeofthought.Theprimeexampleofthisunvarying ‘mathematicalDNA’isfromgeometrywhichisalmostalwaysreduced,from the ´ Sulbas¯utra downtotheNilatexts,totheapplicationoftwoprinciples:the

Pythagoreanpropertyofgeneral(i.e.,notrestrictedtointegralorrational) righttrianglesandtheproportionalityofthesidesofsimilar(generally,right) triangles.Similarly,therecursiveprincipleunderpinningtheconstructionof decimalplace-valuenumbersandtheearlyrealisationthattheyareunbounded havebigrolestoplayinthetreatment,2,500yearslater,ofpowerseriesin theNilawork.Eventheinductiveproofswhichmaketheirfirstappearancein thislastphaseareintroducedfromarecursivestandpoint,asdistinctfromthe formal-logicalfoundationfavouredlaterinEurope.

Justasconspicuousasthesecommonalitiesistheabsenceofconcepts andmethodswhichthemodernmathematicallyliteratereaderacceptsunquestioningly.Forinstance,thoughtheoperationofdivisionandthenotionof divisibilityarepresentfromveryearlytimes–theplace-valueconstructionof numbersisbased,afterall,ontheiteratedapplicationofthedivisionalgorithm –thereappearstohavebeennospecialsignificanceattachedtoprimenumbers,anditisnotclearwhy.Lesspuzzlingistheavoidanceofthepowerfuland ubiquitousmethodofproofbasedontheruleoftheexcludedmiddle,proofby contradiction.Thelogicalbasisofreasoningbycontradictionwasconsidered byphilosophersfromaveryearlytime,pronouncedunsoundandrejectedasa meansforthevalidationofknowledge.Abeliefusedtobeprevalentinsome mathematical-historicalcircles(andisoccasionallystillexpressed)thatIndian mathematiciansdidnothaveproofsformanyoftheirassertionsor,worse,that aconceptionofalogicalproofitselfwasabsent.Itwillbeseenthatthisis amyth;only,thelogicissomewhatdifferentfromwhatisaxiomaticinthe Europeanapproach,thatofaprogressionfromaxiomtodefinitiontotheorem using,ateverystage,equallyaxiomaticrulesofreasoning.

0.2Sources

Theterm‘India’or,occasionally,‘culturalIndia’asusedinthisbookencompassesofcoursepoliticalIndiaatthetimeofindependencebutalsocovers whatiscalledtheIndiansubcontinent,extendingwellintoAfghanistaninthe northwest.Historicallyandculturallyitalsoincludedlargepartsofsoutheast Asiawhich,aswillbeseen,madeatleastonesignificantcontributiontothe reconstructionofthewholestory.

Therecordedevidenceonwhichthereconstructionmustbebasedcomprisesanysurvivingmaterial,concreteor(moreorless)abstract,fromwhich wecandrawreasonablysecureconclusionsaboutthosepreoccupationsofthe pastinhabitantsofIndiathathaveaclearmathematicalcontent.Thevastmajorityofsuchrecordsaretextsdealingwithmathematics,generallyinparallel withapplicationstosomepracticalsciencewhich,inlatertimes,wasalmost invariablyastronomy.Butthereareothersourcesofinformationaswellwhich supplementthetextsandmakeupfortheirshortfalls.Anextremeinstanceis theearliesthistoricalperiod,theIndusValleyperiod,whichhasleftbehind asplendidcollectionofruinsbutwhosewritinghasnotyetbeendeciphered.

Theonlyrecoursewehavethenistotryand‘read’civilisationalartefactsother thantexts,abstractionssuchastownscapesandstreetplans,floorplansand elevationsofbuildings,geometricdecorationsonseals,pottery,etc.,aswell asmaterialobjectslikeweightsandothermeasures.Whilelittlecanbesaid withabsolutecertainty,surprisinglygoodinformationofageneralmathematicalnaturecanbeplausiblyextractedfromIndusValleymaterialofvarious sorts.

Textualsourcescanbedividedintotwotypestobeginwith,thosewhose mathematicalcontentisscatteredandincidentalandthosedevotedwhollyto expositionsofmathematics(anditsapplications).Mostoftheearlytextsof eithertypewerecomposedorally,memorisedand,intheearlypartoftheir existence,transmittedorallybeforebeingtranscribedonperishablematerial. Butbeforeturningtothesetwotypes,Ishouldmentionadifferentkindof writtenevidence,inscribedpermanently(verypermanently)onstonemonuments,coins,copperplatesrecordinggrantsetc.,themostfamousbeingthe firstsymbolicrepresentationsofzeroasanapproximatecirclecarvedonstone (southeastAsiaandGwaliorinIndia).Theyarecomparativelylate,theearliest numericalinscriptions(outsidetheIndusValleyseals)beingfromthecenturies aroundtheturnofthecommonera,showingnumeralsintheBrahmi(Br¯ahm¯ı) script.Thelateoccurrenceofwrittennumeralsisconsistentwiththeprimacyof numbernamesratherthannumbersymbolsinIndia,atopicwhichwilloccupy uslater.Aftertheycameintocommonuse,Brahminumeralsseemtohavegone throughacomplicatedevolutionbeforesettlingdowntothecurrentlystandard ArabicnumeralsaswellasvariousminorvariantsinIndianlanguages.They arewelldocumentedinseveralstudies,notablyinthebookofDattaandSingh ([DS]).

ThetextsIhavecharacterisedasincidentallymathematicalareof paramountimportanceastheyare,withtheexceptionofthe ´ Sulbas¯utra,our onlyprimarysourceofknowledgeaboutmathematicsintheVedicperiod,in particularaboutthegenesisandrapiddevelopmentofdecimalplace-valueenumerationanditsuseinelementaryarithmetic.Theycomprise,first,theearliest Indianliteraryproductions,namelytwooftheoriginalVedic(sam . hit¯ a)texts, the R . gveda andthe Yajurveda,thelattermoreparticularlyintheearlierofits tworecensions,named Taittir¯ıyaSam . hit¯ a.Someusefulinformationalsocomes fromafewofthe Br¯ah . man . asand Upanis . adswhichare,byandlarge,exegetic elaborationsofVedicritualandphilosophy.Scholarsdatethegatheringtogetherofthe R . gveda intotenBooksor‘circles’toaround1200-1100BCE butalsothinkthattheindividualpoemsorhymnswerecomposedinthecenturiesleadingtothatperiodfromthetimeoftheappearaceoftheVedicpeople innorthwestIndia.The Taittir¯ıyaSamhit¯ a,whichismostlyatextdescribing detailsofritualpractices,isprobablyfromonlyalittlelaterandisfullofvariousregularsequencesofnumbers,includinglistsofnamesofpowersof10.It wouldseemfromthewaytheselistsarepresentedthatthefirstintimationsof theunboundednessofnumberswerealreadyintheair.Thefascinationwith thepotentialinfinitudeofnumberscontinuedforalongtime–perhapsnot

solongconsideringthatthequarrybeingchasedwasunattainable–leading tothenamingofsequentialpowersof10extendingtomind-bogglingmagnitudes.Evidenceforthiscomesfromreligioustexts(Vedic/Hinduaswellas JainaandBuddhist)andfromothersourceslikethegreatepics R¯am¯ayana and Mah¯abh¯arata,composedintheformweknowthemtodayprobablyjustbefore thecommonera.

Thevalueofliteraryandreligioustextsasrepositoriesofmathematical informationisgreatlyenhancedbythesurprising–forapeoplewhoturned everythingtheyknewintoliterarycompositions–absenceofanyworkthat laysouttheprinciplesgoverningdecimalenumerationanddecimalarithmetic. Thatisnotthecasewhenitcomestoearlygeometry.The ´ Sulbas¯utras are traditionallysaidtohaveexistedinanumberofversionsofwhichfourappear tohavesurvivedmoreorlessintact.Theyarethoughttobedifferentrecensions ofmaterialdrawnfromacommonstoreofknowledge,madeatdifferenttimes (andperhapsindifferentplacesintheGangeticbasin)rangingoverca.800-400 BCE.BeinghandbooksfortheconstructionofVedicritualaltars,theirpurpose isprimarilyarchitecturalbutthepreciseandquantitativetreatmentoffloor planshavingdifferentregularshapesturnsthemeffectivelyintoworkbooksof planegeometry.Inthisrespectthe ´ Sulbas¯utrasstandapartfromalltheother sourceswehaveformathematicsintheearlyperiod.

Themiddleorclassicalperiodbroughtaboutaradicalandpermanent changeinthenatureofmathematicalenquiryand,withit,inthecharacterof thetexts.Astronomybecamethedrivingforceofmathematics;infactthetwo sciencesbecameinseparablylinked.Goingbythetexts,allastronomerswere alsomathematiciansandmostmathematicianswereastronomers,atrendthat survivedrightuntilthelastphase.Itistemptingtosaythatmostofthemwould havethoughtofmathematicsastheprerequisitefordoingastronomyrather thanofastronomyasappliedmathematics.(Fromnowonitwillbeunderstood thattheword‘mathematician’asusedinthisbookwillrefergenerally,with oneortwoobviousexceptions,toanastronomer-mathematician.)

Asfortheirtexts,Ihavealreadynotedthattheclassicalperiodsawthe appearanceofwhatwemaycallmonographsforthefirsttime(the ´ Sulbas¯utras partiallyexcepted).Theirproductionbecameincreasinglyfrequentandonehas thesensethatthisperiodalsomarkstheemergenceofaprofessionalmathematicalcommunity.

Thetextsthemselvescanbedividedlooselyintotwobroadcategories: originalworkshavingsomenewmathematicstoexpoundandcommentaries (bh¯as . ya or vy¯akhy¯ a;therearealsootherlesscommonnames)onthem(andan occasionalcommentaryonacommentary).Thenumberofcommentariesthat aparticularworkgeneratedseemstohavebeenanincreasingfunctionbothof itssignificance(and,hence,oftheesteemandreverenceinwhichitsauthor washeld)andofitsbrevity(and,hence,ofitsdifficulty).Theprimeexample isofcourse Aryabhatıya,highlyesteemedandveryshort,withabouthalfa dozenknowncommentatorsextendingfromBhaskaraI(early7thcentury)to Nilakantha(N¯ılakantha)(early16thcentury)tryingtheirhandatmakingits

crypticversesmoreaccessible;indeed,itisonlyamildexaggerationtocharacterisemostoftheworkduringthistimeasconstitutingaworkingout–a multi-author mah¯abh¯asya sotosay–ofAryabhata.Otherinfluentialexamples are Br¯ahmasphutasiddh¯anta ofBrahmagupta,someofthewritingsofBhaskara IIand,fromthelatephase,Nilakantha’s Tantrasam . graha whichinspiredtwo veryimportantself-describedcommentariesonitinlessthan50years.Naturally,thecommentariesalsotendtobelonger;andtheyareofteninprose, morefrequentlythanthesourcetextstowhichtheyareanchored.

Nonetheless,thedivisionintothesetwocategoriesisnotwatertight. Firstly,everytextstartswithar´esum´eoftheknowledgealreadyacquired, whosepurposewastoserveastheplatformonwhichnewmathematicswill bebuilt–even Aryabhat . ıya,possiblytheshortestmathematicaltreatiseinhistory,beginswithanevocationofdecimalenumerationbyrecallingthenamesof powersof10aswellassomeelementarygeometry.Forthehistorianthisbrings intwoadvantages:filteringout(theveryinfrequent)patenterrorsfromearlier workwhileatthesametimegivingaglimpseofhowlatermathematiciansunderstood(or,occasionally,misunderstood)thematerialtheywerebuildingon. Weshallmeetinstancesofbothinthecourseofthisbook.

Conversely,manycommentaries–sodescribedintheirtitlesoropening passages–notonlyprovideclarificationsandinterpretationsoftheoriginal work,butalsoputforwardgenuinelynewideasandinsights.Averygood exampleisNilakantha’s Aryabhatıyabh¯asya whichsubjectsAryabhata’stext toasearchinganalysisandreinterpretationinthelightofthenewresultsof MadhavaandtheNilaschooland,intheprocess,turnssomeoftheimprecisely wordedaphorismsintheoriginalintoprecisemathematicalstatementswhich Aryabhatahimselfmayormaynothavehadinmind.

Thegenerallyacceptedexplanationformostofthesedifferencesofpresentationisthattheoriginaltextswereintendedtobememorisedasthecoreof aguru’steaching,tobesupplementedbyface-to-faceexplanationsanddemonstrations.Inanycase,nomodernreadingofanancientmathematicalclassic canbeconsideredcompletewithoutattentionbeingpaidtothemoreimportantcommentariesthatcamelater,evenintherarecaseswheretheymayhave beenmisled.

ThelanguageofIndianmathematicsis,overwhelmingly,Sanskrit.From Vedictimesuntiltheveryend,fromthenorthwesttotheextremesouthandat allplacesinbetween,allthemaintexts–withoneverysignificantexception–werecomposedandcommunicatedinthevariantofSanskritprevalentatthe particulartime,withoutmuchgeographicalvariation.Duringthefirstperiod whenVedicSanskritwasthenaturallanguageofliteratepeopleandthesecond periodwhenclassicalSanskritwasthelanguageoflearninginnorthIndia, thisistobeexpected.Asmainstreammathematicsspreadfurthersouthto regionswithastronglocalliteraryandlinguisticlifeoftheirown,thehabitof doingtraditionalsciences,the ´s¯astra,inSanskritsurvived.Anexplanationfor thisconservatismmaybethatBrahmins,whowerethepeopleoflearningand whobeganmigratingtosouthIndiainlargenumbersinthesecondhalfofthe

firstmillenniumCE,remainedprotectiveoftheirinheritanceforalongtime. Apartfromsomehistoricalevidencethatthiswasso,quitestronginthecaseof BrahminsinKerala,itisafactthatthestyleofformalSanskritmathematical presentationhardlychangedfromAryabhatatoNilakantha.

Thesignificantexceptionmentionedaboveistheremarkabletreatise Yuktibh¯as . a,writteninKeralaaround1525CEbya“venerabletwice-born”(Brahmin)namedJyesthadeva(Jyes . t . hadeva).Itisremarkableformanyreasonsas weshallsee–alargepartofPart3ofthepresentbookdependscriticallyon itsreading–butwhatistobenotedhereisthatitisnotinSanskritbutin Malayalam,thelanguageofKerala.Anditisnotasthoughitmarkedthebeginningofatrend;severalworkswerecomposedinKeraladuringthefollowing centuryinchasteclassicalSanskrit.WehavenoideawhyJyeshthadevadecided topopularise,ifthatwastheintention,asciencewhichuntilthenhadremained thepreserveofthosewhowereproficientinSanskrit.

Anotherthingwedonotknowiswhenthetextsbegantobewrittendown. ThereislittledoubtthatmaterialfromtheVedicagewascommunicatedorally foralongtime.Evenintheclassicalage,bywhichtimewritinginvarious scriptshadbecomefairlystandard,oralteachingandlearningstillretainedits preeminence.NeverthelessitisatacitassumptioninIndologicalstudies,very likelycorrect,thatmostmaterialgotwrittendownsoonerorlater.(Iwilluse termslike‘writings’and‘books’torefertoworkwhichmayhavebeguntheir lifeorally,asIhaveused‘literate’tomeanalsoorallyliteratebeyondtheneeds ofbasicfunctionalcommunication).Inanycase,whatwasactuallywritten downwasonperishablemateriallikepalmleavesandmanuscriptshadtobe copiedandrecopiedperiodicallyforsurvival.Consistentwiththehistoryofthe influxofBrahminsintopartsofsouthIndia,mostmathematicalmanuscripts originatinginnorthernIndia(oftheclassicalageandlater)wereunearthedin Kerala,thelastrefugeofthesciencesincolonialIndia,oftenfromtheprivate librariesofBrahminfamilies.Atthesametime,theimpactofSanskritonthe locallanguagegaverisetomodernMalayalam,writteninarapidlyevolving scriptofitsown.Atsomepointinthisprocessofsanskritisation,Sanskrit itselfcametobewritteninthelocalscript,withtheendresultthatthevast majorityofsurvivingSanskritmanuscriptsinKerala–i.e.,alargeproportionof all survivingmanuscripts–areinMalayalamscript.Itwillobviouslybeabsurd toconcludefromthis,assomewritersstilldo,thatAryabhataforexamplewas borninKerala.

Inthelightofallthis,itisnaturaltowonderwhetherwehaveinhandtodaytheessentialprimarysourcesnecessaryforthedelineationofasatisfactory pictureofthetotalityofIndianmathematicalculture,inotherwordswhether somecriticallyimportantmanuscriptmaynotstillbelyingunsuspectedinthe recessesofsomeoldfamilylibraryorlostpermanentlytotheravagesoftime. Wecannotofcoursebesurebut,hereagain,thepersistenceofknowledgeacquiredearlieracrossgenerationsoflaterwritingsprovidesaguarantee,Ithink, thatnothingtrulysignificanthasdisappearedforgood.Therewasatimein thefirsthalfofthe19thcenturywhenscholarshadaccesstoBrahmagupta’s

writingswiththeirnumerousandhostilecriticismsofAryabhatandoctrine, butnofirst-handknowledgeofthe Aryabhatıya itself.Theworldwassavedthe needtoguesswhatthe Aryabhatıya reallycontainedbyitspublicationin1874. Thenearesttofindingoneselfinasimilarpredicamentagainistheabsence ofanyknownmathematicaltext–afragmentaryastronomicalworkoflittle mathematicalinterestapart–attributabletoMadhava.Wecanalwayshope thatsuchamanuscriptwillonedaycomemiraculouslytolightbutthatis unlikelytochangeourunderstandingofhismathematcs;theextensivewritings ofthosewhofollowedhimintheNilaschoolalreadygiveusaverycoherent ideaofwhatitmightcontain.

Therearealsoissuesonwhichthemodernreaderwouldprefertoget alittlemorehelpthanisavailableinthetexts.Thefirstconcernsdiagrams. Perhapsbecausedrawingwithaheavyironstylusondriedpalmleafisnot easy,theyareabsentfrommanuscriptsexceptforanoccasionalrudimentary sketch.Thiscanbeahandicapwhentryingtofollowacomplexlineofgeometricreasoning(examplesareBrahmagupta’stheoremsoncyclicquadrilaterals andtheinfinitesimalgeometryoftheNilaschool).Whatthereisinsteadare descriptionsofthenecessaryfigures,whicharegenerallyadequate.Inface-tofaceinstruction,diagramswerepresumablydrawnonsandcoveringaboardor thefloor,apracticewhichwasprevalentinKeralauntilaslateasthemiddle ofthe20thcentury.

Theotherstrikingabsenceisthatofasymbolicnotationformathematical objectsandoperationsonthemevenwherelongandintricateandfundamentallyalgebraicreasoningisinvolved,asinBrahmagupta’streatmentofthe quadraticDiophantineequation(latercalledPell’sequationinEurope)orin thederivationoftrigonometricinfiniteseriesbytheNilaschool.Itispossible thatthisisalegacyoftheoraltradition,butitisafact,nevertheless,that abstractrepresentationsoflinguisticobjectsandsetsofsuchobjectswerealreadyemployedbyPanini(P¯anini)(ca.5thcenturyBCE)inhistreatiseon grammar.Inmathematics,theuseofsyllablestostandforunknownnumericalquantitieswasinitiatedbyBrahmaguptaandgivenmuchprominenceby BhaskaraIIinhismonographonalgebra(B¯ıjaganita).Butonewillsearchin vainforasymbolicallyexpressedequation.Inconsequence,aconsiderablepart oftheeffortofreadingatexthastogointoturningnarrativedescriptionsinto thepresentdaymathematicallanguageofsymbolsandsymbolicstatementsof relationsamongthem.Farmoreseriously,thedisdainforasymbolicpresentationmaybeareflectionofacertainmethodologicalpositionwhichinturn ledtoareluctancetoseemathematicaltruthinfullgeneralityandtoobvious pathsnottaken.WewillreturntothispointinsomewhatgreaterdetailinPart IV.

Ontheotherhand,theabsenceofdetailedproofsinmanyofthetexts, whetheroriginalsorcommentariesonthem,isnotaseriousmatter.Withvery fewexceptions,proofsofstatedresults,eithercompleteordetailedenoughfor aninformedreader,canbefoundinsometextortheother.Wehavecometo seerecentlythateveninaccountsinwhichthelogicaldevelopmenttowards

afinalstatement(‘theorem’)issupposednotgiven,aproperunderstanding ofthefinedistinctionsintheterminologyemployedmayinitselfbeagood guidetothereconstructionofthelogic.Moregenerally,thewayaproof–the commonlyusedwordis upapatti or,inlatertimes, yukti,‘reasonedjustification’ –isputtogetherandwhatitassumesasself-evidentrulesofreasoningarequite differentfromthemodernapproachtosuchquestions.Logiciansthroughout historyhavewrestledwiththeissueofwhatconstitutesagoodcriterionfor thevalidationofnewknowledge.InthisbookIusetheword‘proof’without furtherqualificationinthesenseacceptedbyIndianmathematicians–weshall encounternumerousexamplesbelow–eventhoughthatmaynotmeetwiththe approvalofaxiomatistsancientormodern;Indiansdidnotbelieveinaxioms.It wouldseemthatjustasIndianmathematicalauthorshavetheirownparticular styleofpresentingtheirknowledge,sodoesitrequireaparticularwayofreading toabsorbitinfullmeasureandtobeconvincedbyit.

Thisshortgeneralsurveyofthesourceswillbeincompletewithoutalook atonewrittenworktowhichmuchofthegeneraldiscusionaboveapplieswith ahighdegreeofreservation.TheBakhshalimanuscriptasitisknownwas unearthed(literally)in1882inwhatisnowPakistan,withinorclosetothe bordersofancientGandhara.Itiswrittenonbirchbark,apopularmediumof writingfromatleastthebeginningofthecommoneraintheregionsofnorth IndiawheretheHimalayanbirchgrows.Thefraction–howsmallafraction remainsunknown–ofthecompletetextthathassurvivedisinsuchafragile conditionastoprecludescientificmethodsofdating(inthejudgementofits keepers).Whetheritisacopyorarecopyofapreexistingworkortheoriginal isalsonotknown.Inthelattercase,thelackofascientificallydetermineddate isespeciallyunfortunatebecauseitscontentsareinmanyrespectssingularly novel.Asitis,basedonitsmathematics,itslanguage(alocalversionordialect ofSanskrit)andscript(alsoalocalvariantoftheBrahmi/Devanagarifamily), nottomentionpersonalpreferences,peoplehavedateditanywherefromthe 2ndcenturyBCEtothe13thcenturyCE.Evenifwediscounttheextremesof thisquiteimpossiblywiderangeanddateitssubstancebetween,say,the4th andthe8thcenturiesCE,thehistoricalconclusionswecandrawfromitwill dependdramaticallyonpreciselywhenitwascomposedsincethesecenturies encompassthetransitiontotheclassicalageandaveryrapidevolutionwithin thatperiod.Inparticular,anearly,saypre-Aryabhatan,date–Iwillinfact arguelaterforjustsuchaposition–willforcearadicalrevisionofourpresent understandingoftheevolutionofarithmeticalandalgebraicideasinthegap betweenourfirsttwoperiods.

AquicklookatthecontentsofBakhshalishowsushowandwhy.Itis almostuniqueamongthestandardtextsinutilising,atseverallevels,afairly evolvedsymbolicnotation.First,numbersarewritteninsymbols(asdistinct fromtheirnames)indecimalplace-valuenotationusingavariantofBrahmi numbers.(TheearliestBrahminumbersoninscriptionsetc.thatImentioned earlierdidnotfollowastrictplace-valuenotation).Then,arithmeticaloperationswerealsorepresentedabstractly(ofteninadditiontoanarrativedescrip-

tion)andthatencompassedbothnegativenumbersandfractionsaswellas schemataforequations.Ascannotbeavoidedinawrittensymbolicnotation, thereisasymbol(adot)forzero.Andfinally,therearealgebraicequations withasymbolrepresentingtheunknown.Thesefeaturessignallinganevolved arithmeticalculturewouldindicatearelativelylatedateforBakhshaliifwe insistondated,independentcorroboration,e.g.,onBrahmaguptaforthealgebraofpositivesandnegativesorfortheuseofsyllablesforunknowns.Butif Bakhshaliitselfcouldbereliablydatedtobeearlywithinitsplausiblerangeof dates,thatwouldpushbackthetimeofthefirstsignalsofanalgebraicmodeof thinkingbyafewcenturiesandtherebygiveusameasureoftheprogressmade intheinterregnumbetweentheendoftheVedicphaseandthebeginningofthe classicalphase.Suchachronologyisnotoutofthequestion;the ´ Sulbas¯utras docontainsomearithmeticwithfractionsandsubtractions(negatives?).NotationaldeviceslikethoseinBakhshaliresurfaceinoneortwolatertexts–the greatclassicalworksavoidthem–lendingsupporttotheviewthattheywere incontinualusebehindthescenes,intraditionalteaching,intheclassroomas itwere.

ThedeclineincreativemathematicalactivityinKerala(andIndiaasa whole)thatfollowedthearrivalofthePortuguesecausedacorrespondingdecreaseinthenumberofnewtextsaswell.Itistruethatthe16thcenturysaw theproductionofsomemasterpieces, Yuktibh¯asa amongthem,but,withoneor twoexceptions,therewasnotagreatdealthatwasoriginal,evenintermsofinterpretation,inthefewseriousbooksthatwerewrittenafterthe16thcentury. Whatdidhappeninstead,beginninginthelate18thcentury,wasaslowrediscoveryoftraditionalIndianlearning,includingmathematicsandastronomy. Naturally,thepioneersinthisendeavourwereBritishSanskritists,following inthefootstepsofthefirstandthefinestofthem,WilliamJonesofCalcutta. Towardstheendofthe18thcenturyandinthefirstfewdecadesofthe19th camethefirsttranslations,notices,commentariesandlectures(thetranslation ofapartof S¯uryasiddh¯anta bySamuelDavisandJohnPlayfair’sessaysbased onit,ColebrookeonBrahmaguptaandBhaskaraII,WhishonsomeNilatexts, andseveralothers).Thesecondhalfofthe19thcenturysawagradualaccelerationofthisactivityinanumberofEuropeancountriesandeveninAmerica, bringingseveralkeytextstothenoticeofscholars, ´ Sulbas¯utra and Aryabhat . ıya amongothers.Thuscameabouttheslowandhesitantprocessbywhichthe worldcametorecognisetheexistenceofanIndiancultureofmathematical enquirythatwasinlargemeasureself-motivatedandself-sufficient.

Whilearesidualknowledgeoftraditionaltextsandtheirutilisationin preparingalmanacssurvivedthroughcolonialtimes,thereawakeningofacriticalandinformedinterestintheirowntruemathematicalheritageamongIndian scholarscameonlytowardstheendofthe19thcentury.Ithasgrownvigorously since.Givenalsothecontinuingactivityinotherpartsoftheworldinbringing outtheserichesthatlonglayhidden,thisseemsapropitioustimetoattempt anaccountofmathematicsinIndia–themathematicsofIndia–thatnotonly explainsitshighachievementsbutalsopaysattentiontoitsownspecialchar-

acteristics,itsIndianidentityasitwere.Itgoeswithoutsayingthatanysuch attemptmustrelyontheworkofthefinelineofscholars,extendingovermore thantwocenturiesnow,whohavebroughttheirlinguisticandmathematical skillstotheelucidationofwhat,formanyofthem,isanalienwayofdoingand presentingmathematics.Theinformedreaderwillfindmanyinstancesinthis bookofmyindebtednesstotheinsightsofthesesecondarysources.Itisastonishingtorealise,nevertheless,thattherehaveonlybeenthreebookseverthat havetakenonthetaskofpresentingawide-rangingandmathematicallyorientedaccountofthesubject.Ofthese,theotherwiseencyclopaedictwo-volume bookofDattaandSingh([DS])publishedinthe1930somitsgeometry(the promisedthirdvolumenevercameoutexcept,muchlater,asaposthumous journalarticle),butSarasvatiAmma’scomprehensiveandmagisterialbook ([SA])–faithfulandlucidatthesametime–morethancompensatesforthe omission.TheveryrecentbookofKimPlofker([Pl])coversmostofthegeographyandhistoryofIndianmathematicsandhasanextensivebibliographyof currentresearch.Allthreebooksareessentialreading.

0.3Methodology

Thepresentbookdiffersfromthosereferredtoaboveinseveralrespects.Firstly, itisnotascomprehensive;instead,thepremisehereisthatbyconcentrating onthethreekeyperiods,supplementedbyabroaderaccountoftherelevant materialfromtheperiodsinbetween,wecanarriveatafaithfulportraitof Indianmathematicsasitbecamedeeperandbroaderwithtime.Withinthis generalframework,certainthemesrelatingtotheposingandsolvingofimportantproblemsand/ordeparturesalongnewdirectionscanbeidentified.These milestones,togetherwithanindicationofhowearlierworkfedintothem,are shownintheschematicdiagramalongside.Consistentwiththisthematicpartition,theapproachfollowedinthebookislargelychronological.Butthereare placeswhereIhavehadtodeviatefromstrictchronologicalprogression,partly inordertoaccommodateproofswhichareoftenfoundinlatercommentaries, evenwhenwehavereasontobelievethattheywereknownearlier.Moregenerally,ithelpstohighlightthecontinuingrelevanceofcertainthemesacross verylongtimespans,forexampletheinfluenceoftheprinciplesofdecimal enumerationonseveralaspectsoftheworkoftheNilaschool(seetheflow diagram).Also,occasionally,Ihavefounditmoreilluminatingtolookatthe initialstepsinthestudyofaparticulartopicfromthevantagepointofhow itdevelopedlater.Anexample,outofmany,oftheadvantageofinvertingthe chronologicalorderisthelightVedicgeometrythrowsonitspossibleIndus Valleyantecedents.

Itisnotpossibleinabookofreasonablesizetotreateveryadvancein alltheseareaswithequalthoroughness.Choiceshavehadtobemade–there wasalotofmathematicsinancientIndia,andmanymathematicaltexts.Asa rule,Ihavetriedtopickfordetailedtreatmentthosetopicswhicharecentral

Figure1:Themainthemes.Timerunsfromtoptobottom,thoughnotto scale.Ovalcompartmentsarefortopicsnotdiscussedindetail.‘Infinity’is shorthandfortheunboundednessofnumbersand‘circlegeometry’standsfor thegeometryofcyclicfigures,especiallyquadrilaterals.Combinatoricsismissingfromthediagram;itderivedfromprosodyandhadlittledirectimpacton latermathematics.Theattentivereaderwillprobablyaddafewextraarrows tothediagram. totheoveralldevelopmentdepictedintheflowdiagram,the‘bigthemes’:decimalenumerationintheearlyVedictexts,Aryabhatantrigonometry,andthe inventionofcalculusbyMadhava,tomentiononlythemostprominent.Ihave alsopaidspecialattentiontorecentworkeitheraddressingquestionswhichhad notbeenstudiedearlierorclarifyingissuesleftambiguousorunresolvedinpreviouswork.Typicalexampleswouldbetheuseofthegeometryofintersecting circlesinmakingsquaresandgeneratingspace-fillingperiodicpatterns(Indus Valley),thelogicbehindBrahmagupta’stheoremsoncyclicquadrilateralsand thefirstglimpsesofanabstractalgebraicmodeofthinkingintheintroduction ofgeneralpolynomialsandrationalfunctionsinonevariableintheNilawork. Giventheinterdependenceofthesethemes,itgoeswithoutsayingthatthere willbeafairdegreeofoverlap,muchto-ingandfro-ing,intheirtreatment.For thesamereason–ordueperhapstotheinfluenceoftheadmirablepedagogic techniquesof Yuktibh¯as . a?–therewillalsobeacertainamountofrepetitionof someofthekeypointsandthemes.

Secondly,asfarasthehistoricalaspectsareconcerned,theapproach adoptedhereissomewhatdifferentfromtheusual.Duetotheeffortsofmany scholars,weknowalittlemorethanweusedto,notsolongago,aboutthe livesandworkofquiteafewofthemathematiciansbelongingtohistorical times–basicbiographicaldata,approximatedatesandplacesofcomposition ofkeytextsandsoon–thoughmuchremainstobediscoveredinfuturework.

Sincethesefactswill(withafewveryimportantexceptions)onlygetapassing mention,itmaybeusefultothenon-specialistreadertoseesummarisedin oneplacewhatisknownofthechronologyofthemajorlandmarksandtheir authors,togetherwiththekeytexts.Asfarastheearlyphaseisconcerned, thatiseasilydone:wehaveonlytorememberthatthe R . gveda wascompiledin theforminwhichweknowitaroundthe12thcenturyBCEfrommaterialcomposedearlierbyanonymouspoets(evenifnamescansometimesbeattachedto particularpoems),theearliest ´ Sulbas¯utras(ofBaudhayanaandApastamba)in the8thcenturyBCEandthe Taittir¯ıyasam . hit¯ a roughlyhalfwaybetweenthe two.Furtherdowntheline,itseemssafetoplacePaniniinthe5thcentury BCEandPingalaacenturyortwoafterwards.Allthesedates,basedmostly onindirectlinguisticevidence,reflecttheconsensusofmodernscholarship.

FromAryabhataonwards,weareonmuchfirmerground.Thefollowing list,confinedtothosewhohadthegreatestimpact,eitherontheirfollowersor onthejudgementofmodernhistorians,isonlymeantasafirstorientation.(I haveomittedBakhshalisinceweknowneitherthedatenortheauthorship).

Aryabhata(born476CE):Hisonlyknownwork, Aryabhat . ıya,isinternally dated499CE.

BhaskaraI(late6th-early7thcentury):ThefirstprophetofAryabhata, authorofthreeexpositoryworks,amongthem Aryabhat . ıyabh¯as . ya.Allofthem hadgreatinfluenceonthespreadoftheAryabhatandoctrine.

Brahmagupta(firsthalfofthe7thcentury):Authorof Br¯ahmasphut . asiddh¯anta (628CE),stronglyanti-Aryabhataondetailsofdoctrine,andof Khan . d . akh¯adyaka (about650CE),inwhichhereconcileshisastronomicalmodel withthatof“master”(ac¯arya)Aryabhata.

´

Sa˙nkaran¯ar¯ayan . aandhisteacherGovindasv¯ami(9thcentury):Thefirst astronomer-mathematiciansauthenticallyestablishedtohaveworkedinKerala,devotedfollowersofAryabhataandBhaskaraI,andprecursorsoftheNila school. Laghubh¯askar¯ıyavivarana oftheformerisdated869CE.

Mah¯av¯ıra(9thcentury):Hisbook Gan . itas¯arasam . graha hasnoastronomybut isstronginarithmeticandmensuration.TheonlyhistoricallyidentifiableJaina mathematicianandtheleastAryabhatanofall.

BhaskaraIIorBh¯askar¯ac¯arya(born1114):Masteroftheastronomyandmathematicsofhistime,agreatteacherandconsolidator.His Siddh¯anta´siromani (mid-12thcentury)incorporates L¯ıl¯avat¯ ı and B¯ıjaganita

Narayana(N¯ar¯ayanaPandita,14thcentury):Accomplishedinallaspectsof mathematics.His Ganitakaumud¯ ı (1356)hasmanystrikinglyoriginalresults, especiallyincombinatoricsandcyclicgeometry.MayhavebeenfromKarnataka (or,remotelypossibly,fromKerala)whichwill,perhaps,linkhimto

Madhava(approximately1350-1420?):Astonishinglylittleisknownaboutthe inventorofcalculus.Oneshorttextattributedtohim,onthemoon’smotion and,maybe,oneortwootherfragments.

Nilakantha(1444-1525-1530):Theconscience-keeperoftheNilalineage. Wrotemanybooksofwhich Tantrasam . graha hadgreatinfluence.Themasterful Aryabhat . ıyabh¯as . ya,whichhehimselfcalls Mah¯abh¯as . ya,theGreatCommentary (likePatanjali’scommentaryonPanini’s As . t . adhy¯ay¯ ı),writtenlateinhislife, is the keytoAryabhata’smind.

Jyeshthadeva(secondhalfof15th-firsthalfof16thcentury):Hardlyanything knownabouthislife.DiscipleofNilakanthaandauthorof Yuktibh¯as . a,byfar themostimportantbookabouttheworkofMadhavaandtheNilaschool(and, inmyview,oneoftheclassicsofalltime).

Theoverallpicturethatemergesisofacoherentmathematcalculture,nomatterwhocontributedtowhatpartsofit,orwhen,orwhere.Iwillreturntothe themeofthesenseofunityallofthemtogetherconveyattheend(Chapter 14)ofthisbook.

Athirdissuewhichisreallysubsidiarytothemainconcernofthisbookbut whichcannotbeavoidedisthatofpossiblemathematicalcontactsbetween Indiaandotherculturesatvarioustimes.Itcannotbeavoidedbecausethere hasbeenatrendamonghistoriansintheEuropeantradition,fromColebrooke onwardsandstillquitealive,tohypothesiseexternalinfluences–Babylonian, Greek,Chinese,etc.–inthegenesisofseveralIndianmathematicaldevelopments.Thisisadifficultissuetobecategoricalabout.Documentaryorother unimpeachableevidenceinsupportof(oragainst)suchtransmissionsdoesnot existasarule.Historicalplausibilitybasedonculturalcontactsattheappropriatetimecansometimesbesuggestedbut,often,cannotbebuiltupon.Inthese circumstancesitwouldseemreasonablethatthecasefororagainsttransmissionisbestmadebylookingattheparallelevolutionofamathematicaltheme orarelatedsetofthemesasawhole,aswellasatideasandtechniquesthat are not heldincommon,ratherthanattheoddsharedfactoid,inotherwords bypayingattentiontothetotalityoftheinternalevidence.Ontheoccasions whenthisissuedoescomeup(mostly,butnotonly,inrelationtogeometry),I havetriedtodothat.AgoodcasestudyistheclearandstrongAlexandrian, specificallyPtolemaic,influenceonAryabhata’ssystemofastronomy.Theinternalevidenceforacorrespondinginflowofpurelymathematicalideasisweak andimpossibletoidentifyobjectively,despitesomeconfidentclaimsmadeto thecontrary.Itisperhapsinevitablethat,inthereversedirection,thereis currentlyatendencyamongafewwriterstoseeEuropeancalculusofthe17th centuryasderivingitsinitialimpetusfromtheearlierworkoftheNilaschool. Hereagain,thereissofarnoevidenceinsupportofthehypothesis.Thistoo isaquestionIwilldiscussasitcomesupandattheend(Chapter16.2).

IfevidenceofaflowofmathematicalideasintoIndiaisweak,thecasefor anorganicevolutionwithinIndia,datingbackasfaraswecango,iscorrespondinglystrong;thedelineationofthatcontinuityisoneoftheaimsofthisbook. Aspartofthataim,IhavetriedtoframeIndianmathematicswithinthegeneralcontextofIndianhistoryandculture,ofthemovementofpeopleandideas, linkageswithotherdisciplines,inshorttheintellectualclimateofthetimes.The historicalinterludesthatareoccasionallysandwichedamongthedescriptions ofthemathematicsaremeanttoservethatpurpose.Apartfromprovidingthe generalcontext,itisafact,atleastinIndia,thatabroaderculturalviewoftenthrowsadirectlightonthesubstanceandstyleofthemathematicsitself, thoughitisunderstoodthatcultureandhistoryaloneneverproducedagenius. Likeallhistoricalreconstructions,suchanendeavourcannotbeanythinglike thelastword;newfactsandfreshinsightswillcontinuetoemergeandbring withthemtheneedtoreevaluatesomeoftheconnectionstentativelysuggested here.

Thathavingbeensaid,itbearsrepetitionthatthisbookisreallyand fundamentallyaboutthemathematics.Inparticular,evenastronomy perse, whichwastheoriginalmotivatingforcefortheAryabhatanrevolution,willonly getpassingmentions.

Inthemannerofpresentingthemathematicalcontent,thehistorianis facedwiththeeternaldilemmaofallhistoryofscience:findingtherightbalancebetweenliteralfaithfulnesstothesourcesandthewishtoseewhatwas doneinthedistantpastfromtheperspectiveofwhatweconsiderinteresting andimportanttoday.Absolutefidelitytotheoriginaltextsriskslosingthe presentdayreader,usedasheorsheistothehabitsofthoughtanddiscourse ofascience,mathematicsinthepresentcase,thathasgrownunrecognisablyin depth,generalityandsophisticationinthelastfewcenturies.Itisofcourseaxiomaticthataliteralreadingoftextsmustremainthefoundationofwhatever conclusionsonemaydrawfromthemandgoodtranslationshavepreciselythat function,leavingthereadertomaketheadjustmentsnecessarytofittheseinto themathematicaluniversethatweinhabitnow.ForEuropeanmathematics, thishasbeenrelativelyeasytomanageasthemodernstyleofmathematical writingisinadirectlineofdescentfromtheMediterranean-Greek.Thereare infactsuccessfulbookswhichrelyonthatapproach.Suchtotalliteralnessis lesslikelytosucceedwithIndianmaterial,whichhasitsownstyleofcommunication–asalreadynotedinthesectiononsources–indeeditsownway ofthinkingofanddoingmathematics.MostscholarsoftheIndiantradition, fromColebrookedown,haveunderstoodthis,atleastimplicitly.Severalrecent studieshaveinfacttakentherouteofaccompanyingatranslationofthework concerned,alsogivenalongsideintheoriginallanguage,withdetailednotes inthemodernstyleandinmodernterminologyandnotation:Sarma(Yuktibh¯as . a),Patte(commentarieson L¯ıl¯avat¯ ı and B¯ıjagan . ita),Ramasubramanian andSriram(Tantrasam . graha),tociteonlythemostrecent.

Inageneralbooksuchasthis,aimedmainlyatinterestedbutnotspecialistreaders,thisscholarlyidealisdifficulttosustainevenforselectedextracts

andperhapsnotdesirable.Initsplace,Ihaveadoptedalessdemandingapproach,limitingdirectcitationsfromthetextstotranslationsofafew(very few)essentialorinsightfulpassagesandfreelyusingsymbols,equations,diagramsandterminologythatarethecurrencyofmodernmathematicalcommunicationatalllevels,whiletryingatthesametimetoremainfaithfultothe originalcontent;veryoccasionallyandmainlyascontext,therewillevenbe evocationsofmoremodernconcepts.Suchanapproachalsohelpstocounter thetemptationoflookingatIndianmathematicswithitsnon-Greekpedigree assomethingexoticandalien,donebypeoplewithstrangewaysofthinking, tobeunderstoodafterstrenuouslymasteringstrangeanddifficultlanguages. ThehopeisthatthereaderwillseeattheendthatthemathematicsofIndia isthesamemathematicsthatheorsheisusedto–andthatappliesalsotoIndianreaders.Itgoeswithoutsayingthatsomeofthemathematicssoconveyed willbeelementary,schoolandcollegemathematicsofpresenttimes.Butthere willalsobetopicswhich,inherentlyandintheirtreatment,wewillconsider todaytohavebeensophisticatedandmoderninspirit.Exampleswouldinclude Aryabhata’sintroductionoffunctionaldifferences,Brahmagupta’smethodof generatingnewsolutionsofthequadraticDiophantineequationfromknown ones,thequasi-axiomatictreatmentin Yuktibh¯asa ofthesetofpositiveintegers,possiblyaspreparationforinductiveproofs,andmanyothers–modernity isnotnecessarilyanincreasingfunctionoftime.Anabstractnotationandthe mindsetthatgoeswithitareanadvantageinassigningsuchadvancestheir properplaceintheevolutionarychainofmathematicsasawhole.Atthesame time,andequallyusefully,thedetachmentthatresultsfromadegreeofabstractionwillletusseemoreclearlythedifficultyaverballyexpressedmathematical culturefacesinextendingandgeneralisingknowledgeacquiredinaparticular context.

Buttranslatingmathematicalverseandproseintoanabstract-symbolic languagealsohasitsrisks.Itisalltooeasytoreadmoreintoapieceoftextthan wasactuallythere,e.g.,toseeintheequationrepresentingaverbalpassage allthatthatequationconveystothepreparedmindoftoday.Thereisalsothe oppositerisk,thatofdevaluingtheoriginalityandpowerofanideaormethod becauseeverythingthatamodernmathematicalsensibilityexpectstoreadinto itssymbolicexpressionisnottobefoundinitsfirstformulation.Examplesof bothkindsofmisreadingareeasytocomebyintheliterature,asweshall haveoccasiontonote.Aconsciousefforttokeepoutthebiasesofmodernityis neverthelessworthmaking,evenifdestinedtobenotwhollysuccessful.

Thisisnotmeanttobeascholarlybook.Itbeganlifeasthenotesfora coursegiventouniversitystudentsofscienceanditsprimarygoalistoinform andinstructthosewho,likemystudents,wishtoacquireageneralpictureof themathematicalcultureofIndiathatdoesnotsacrificeessentialpedagogic details;allmathematicalstatementsmadeareprovedandtheproofsarethose inthetexts,occasionallystreamlined,withnoticegiven,tosatisfythemodern normsofmathematicalwriting.Myaimofkeepingitreasonablyself-contained isalsoreflectedinthewayIhaveselectedandorganisedthebibliographic

material.Itisbynomeansexhaustive.Therearelistsattheendofthebook oftheindispensableoriginaltexts(includingtranslationsintoEnglishwhen available)andofsecondarysourcesthatIhavefoundmostuseful.References thatrelatetospecificpointsarerelegatedto(infrequent)runningfootnotes.

0.4SanskritanditsSyllabary

Though,intheinterestsofageneralreadership,Ihaveavoidedquotations intheoriginalSanskrit,itisdifficulttokeepoutSanskritwordsandphrases altogether,andformorethanonereason.Thereisfirsttheneedtoconvince thattranslationsareverifiablyaccurate.Whenmorethanonewayofrendering aparticulartermsuggestsitself,orhasbeensuggestedintheliterature,Ihave feltitusefultoaccompanymychosenreadingbytheoriginalexpression.That isasmallpricetopayforkeepingawayfromineleganciessuchastheliteral ‘seedcalculation’(b¯ıjaganita)foralgebraor‘debtamount’(rnasamkhy¯ a)fora negativenumber.StudentsofSanskritknowthatitisapreciselanguageand thatpossibleambiguitiescanoftenberesolvedbyarigorousreadingoftheexact terminologyemployed.Indeed,problemsofgreatmathematicalandhistorical interestwhichrevolvearoundthephraseologyused,andcanberesolvedby attendingtotherulesleadingtothatphraseology,arenotunknown.

Atthesametime,therearealsoplaceswheredifferentwordsareusedto connotethesameconceptor,converselyandmoreproblematically,oneword maystandfordistinctthoughrelatedconcepts.Suchdeviationsfromaone-one correspondencebetweenmathematicalobjectsandoperationsontheonehand andterminologyontheotheristobeexpectedinwritingthatisentirelyinnarrativeforminanaturallanguage.Butitcanbeconfusing.Theproblemafflicts Aryabhata–who’s s¯utra formathaslittleroomforpreciselyconstructednames andtheirexplanations–asmuchasitdoestheworkoftheNilaschoolwhere terminologicalinventivenesshasahardtimekeepingupwiththeproliferation ofinnovativeideasandmethods.

Relatedtotheseistherecoursetocertainformulaicwordcombinations whicharedesignedtoconveymuchmorethantheirliteralmeaning.Thesense tobeattributedtothemisdecidedeitherbyconventionorthemathematical contextinwhichtheyoccur.Perhapsthemostcommonis trair¯a´sikam (‘ofthree numbers’)generallytranslatedasthe‘ruleofthree’,therulewhichdetermines anynumberoutoffour,whichareinequalproportionpairwise,fromtheother three.EvenmorerichincontentistheNilaschool’s j¯ıveparasparany¯ayam,‘the principleofadjacentchords’,whichstandsfortheadditionformulaforthesine function and Madhava’sderivationofit.Inneitherofthesecasesisthefull meaningoftheformulaindoubtbutthatisnotalwaystrue.

Theseareallgoodreasonsforthedistractingpresenceoftheoccasional Sanskritphrase.Mainlytheyserveasguidepoststohelpusstayonthestraight andnarrowpathoffidelitytothetexts,especiallyinabooksuchasthisthat istwiceremovedfromtheoriginalmaterial,translationintoEnglishfollowed

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

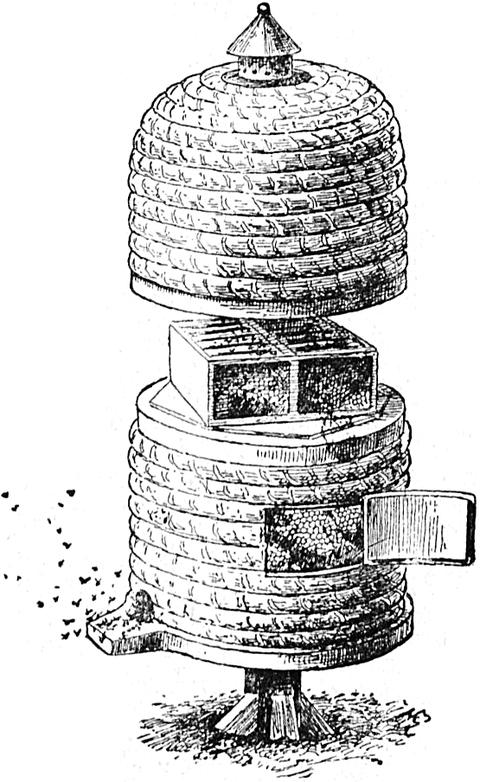

Bienenstock mit einem Aufsatz aus Holzrähmchen auf dem oberen Teile und einem Glasfenster in der Seite.

Wollt ihr nun Bienen züchten, so müßt ihr einige einfache Regeln beobachten. Ihr müßt immer sehr sanft und ruhig mit ihnen umgehen. Sie werden euch bald kennen lernen und merken, daß ihr euch nicht vor ihnen fürchtet.

Ein Bienenstock aus Stroh sollte ungefähr 45 cm breit und 25 cm hoch sein; oben ist er flach und muß eine Öffnung (s. S. 53) haben, in der ein Pflock steckt. Man setzt diesen Bienenstock an eine warme geschützte Stelle des Gartens auf eine hölzerne Bank ungefähr einen halben Meter über dem Boden. Im Mai kauft man dann einen Bienenschwarm, der gerade aus dem Stock eines Nachbars gekommen ist. Man kann den eigenen Bienenstock im Innern mit Zucker bestreichen und hält ihn unter den Zweig, an welchem der Schwarm hängt. Man schüttelt nun sanft am Zweige, bis die Bienen in den Korb fallen, den man dann umdreht und am

Abend vorsichtig an die Stelle trägt, wo er bleiben soll. Am nächsten Morgen werden die Bienen fleißig bei der Arbeit sein. Die großen schwerfälligen Drohnen kriechen faul umher, aber die kleineren Arbeiter werden ausfliegen und Honig sammeln oder sich im Stock aufhängen, bis sie Wachs in ihren Drüsen haben (siehe S. 50) und anfangen können, die Honigwabe zu bauen.

Wenn der Schwarm, den ihr eingebracht habt, der erste war, der den Stock verließ, so wird die alte Königin, die sich in seiner Mitte befand, bald beginnen, Eier in die Zellen zu legen: sie legt täglich ungefähr 200. Aber ein zweiter Schwarm wird von einer jungen Königin geführt, und diese wird mit den Drohnen ausfliegen, ehe sie im Stocke Eier legt.

Tafel VII

Fliegen.

1 Blaue Schmeißfliege, a) Eier, b) Larven, c) Puppen. 2. Rinderbiesfliege (Dasselfliege). 3. Magenbremse des Pferdes. 4. Bremse. 5. Kohlschnake.

Nun müssen die Arbeiterinnen sehr geschäftig sein. In zwei oder drei Tagen kommen die ersten Eier aus und eine Anzahl der Arbeiterinnen füttern die Larven mit Honig und Blütenstaub, den die anderen Bienen einbringen. In ungefähr fünf oder sechs Tagen schließen sie die Öffnungen der Zellen und die Bienenlarve spinnt ihren seidenen Kokon, in dem sie sich in zehn weiteren Tagen zu

einer Biene entwickelt. Dann kriecht sie aus und arbeitet mit den übrigen.

Die leere Zelle wird bald mit Honig gefüllt sein; aber er ist braun, nicht weiß und rein wie der Jungfernhonig, mit dem die Zellen gefüllt werden, in denen noch keine Brut herangezogen wurde. Nach ungefähr sechs Wochen legt die Königin einige Eier in größere Zellen, aus denen männliche Bienen oder Drohnen auskriechen.

Dann legt sie ungefähr alle drei Tage ein Ei in eine fingerhutförmige Zelle am Rande der Wabe. Die Larve darin wird mit besonders guter Nahrung gefüttert, und wird eine Königin.

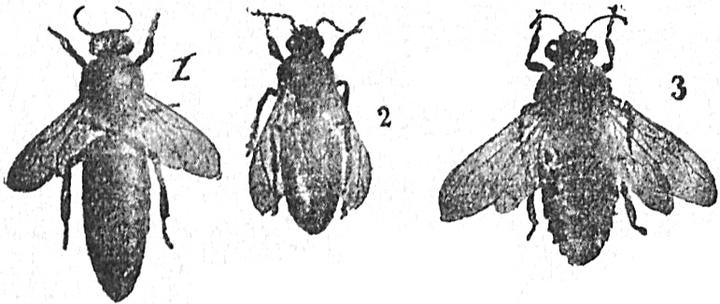

Bienen

1 Königin 2 Arbeiterin 3 Drohne

Wenn ihr keinen Bienenstock mit einem Glasfenster habt, könnt ihr alles dies nicht beobachten. Aber man kann annehmen, daß gegen Anfang Juni der Stock voll von Bienen und Honigwaben ist. Dann ist es Zeit den Pflock am oberen Ende herauszunehmen und einen Aufsatzkasten, der mit Rähmchen versehen ist (siehe S. 51), oben aufzusetzen. In diese werden die Bienen Waben bauen, die man fortnehmen kann. Man muß ein kleines Stückchen Wabe hineintun, um die Bienen zum Bauen zu veranlassen, und dann muß man das Ganze mit einem Strohkorb oder alten Tüchern bedecken, um es warm, trocken und dunkel zu halten.

In ungefähr einem Monat wird man den Aufsatzkasten voll von Honigwaben finden und kann ihn abnehmen. Der Honig in den Zellen dieser Waben ist rein und klar, und man kann ihn fortnehmen, ohne eine einzige Biene zu töten.

Im Juli bekommt man dann einen oder mehrere neue Schwärme, und wenn dann der September naht, muß man den Aufsatz

fortnehmen und die Öffnung des Bienenstockes für den Winter verschließen. Aber man muß bedenken, daß man einen großen Teil des Futtervorrats der Bienen fortgenommen hat, und muß sie während der kalten Jahreszeit mit Honig und Zucker füttern.

Untersuche drei Bienen, Männchen, Weibchen und Arbeiterin. Untersuche Rüssel und Hinterschienen der Arbeiterinnen. Nimm ein Stück brauner Honigwabe mit Überresten von Bienenbrot und jungen Bienen und vergleiche es mit einer reinen Wabe. Beobachte eine Biene unter den Blumen. Suche eine Honigwabe mit fingerhutähnlichen Zellen am Rande.

L e k t i o n 1 0 . Zweiflügler.

Es gibt eine Menge von kleinen fliegenden Insekten, die zu derselben Familie gehören wie Bienen und Wespen, wie z. B. die Blattwespe, die unsere Pflanzen zerstört, oder die Gallwespe, die so merkwürdige Gallen erzeugt, die wir an den Eichen und anderen Bäumen finden. Man faßt sie zusammen unter der Ordnung der Hautflügler, und sie sind gekennzeichnet durch vier gleichartige mit ästig verzweigten Adern durchzogene Flügel. Die in diesem Kapitel zu besprechenden Insekten dagegen haben alle nur zwei Flügel und werden daher Zweiflügler genannt.

Versuche so viele Zweiflügler wie möglich zu finden. Da ist die gewöhnliche Stubenfliege, die Schmeißfliege oder Brummer, Mücken, Schnaken, Bremsen und viele andere.

Die Stubenfliege und der Brummer sind an der richtigen Stelle sehr nützlich, denn sie verzehren faulende Substanzen und tote Tiere. Aber sie tun großen Schaden, wenn wir zulassen, daß sie sich an der falschen Stelle stark vermehren.

Wenn ihr sehr viele Fliegen im Hause habt, so könnt ihr sicher sein, daß sich irgendwo Schmutz befindet; denn die Stubenfliege legt ihre Eier in Misthaufen und faulige Stoffe oder in irgend welchen Schmutz, den sie finden kann, z. B. hinter eine Tür, einen Fensterladen oder in eine ungefegte Ecke.

Sie legt ungefähr 150 Eier zu gleicher Zeit, und in ein oder zwei Tagen kriechen die kleinen, beinlosen Larven aus und nähren sich von den sie umgebenden Stoffen. In vier oder fünf Tagen hören sie

auf zu fressen und ruhen in ihrer Larvenhaut, die hart und braun wird. Im Sommer kommen sie dann nach ungefähr einer Woche als erwachsene Fliegen aus. Aber im Winter liegt die harte Puppe oft Monate lang, und Leute, die im Herbst ihr Haus nicht gründlich reinigen, werden wahrscheinlich im nächsten Jahre eine Fliegenplage haben.

Die Schmeißfliege, auch Brummer (vergl. bunte Tafel VII. 1) genannt, legt ihre Eier (a) auf Fleisch jeder Art oder auf Körper toter Tiere. Wenn ihre Larven ausgekrochen sind, nützen sie uns dadurch, daß sie uns von schlecht riechenden Stoffen befreien, denn sie geben eine Art Flüssigkeit von sich, die das Verderben des Fleisches beschleunigt, so daß sie es fressen können.

Wohl jedermann kennt die Maden der Schmeißfliege (b), die zum Angeln gebraucht werden. Wenn diese mit Fressen fertig sind, ziehen sie sich zu einer eiförmigen Puppe zusammen. Diese gibt eine Flüssigkeit von sich, die ihre Haut zu einem glänzend rötlichbraunen Gehäuse verhärtet. Im Inneren desselben bildet sich die Schmeißfliege, die nach Erlangung der Reife ihren Kopf so stark hervorschiebt, daß der obere Teil der Puppenhülle wie ein Deckel zurückklappt.

Kopf der Schmeißfliege mit den großen, zusammengesetzten Augen.

Fängt man einen Brummer und setzt ihn mit einen Körnchen Zucker unter eine Glasglocke, so kann man beobachten, wie er

seinen Rüssel ausstreckt und frißt. Man wird sehen, daß er den Zucker dreht und wendet, als ob er damit spiele. Aber er benetzt ihn dabei fortwährend mit einer Flüssigkeit, die er durch den Rüssel ausfließen läßt, um das harte Zuckerstückchen zu einer Art Syrup umzuwandeln, den er aufsaugen kann. Wenn man die Brust der Schmeißfliege sanft zwischen Finger und Daumen drückt, so wird sie ihren Rüssel ausstrecken, und man kann die dicken Lippen am Ende desselben mit der dazwischen liegenden Saugvorrichtung (A) sehen. Aber man braucht ein Vergrößerungsglas oder Mikroskop, um einen kleinen Stachel (l) zu erkennen, der im Innern des Rüssels sitzt, und den sie gebraucht, um die Schale von Früchten, deren Saft sie aufsaugen will, zu durchbohren.

Es gibt aber zwei Arten von Fliegen, die viel schädlicher sind als die Stuben- und die Schmeißfliege. Dies sind die Bremsen und die Dasselfliegen.

Ihr kennt eine der kleinen Bremsfliegen ganz gut, denn sie läßt sich auf unsere Hände oder unseren Hals nieder, wenn wir im Freien sitzen. Ihr Dasein zeigt sie uns dadurch an, daß sie uns einen scharfen Stich versetzt, um uns das Blut auszusaugen. Wir nennen sie Pferdebremse, weil sie die Pferde im Sommer so sehr quält.

Viele andere derselben Gattung sind uns nicht so gut bekannt. Die größte deutsche Bremsfliege (vergl. bunte Tafel VII. 4) ist ungefähr 2–3 cm lang.

Rüssel der Schmeißfliege mit verdickten Lippen: A. Saugende. l. Spitze zum Bohren.

Die Dasselfliegen sind gefährlicher, da ihre Larven Rinder, sowie auch Hirsche und Rehe schwer schädigen können. Die Dasselfliege legt ihre Eier an und in die Haare der Tiere. Lecken diese nun jene Stellen, so gelangen die Eier oder die ausgeschlüpften Larven auf die Zunge und von da in den Anfangsteil des Magens. Die Larven durchbohren die Magenwand und wandern in den Körpern ihrer Wirte, wo sie nach etwa sechs Monaten unter der Rückenhaut anlangen. Dort bleiben sie längere Zeit und erzeugen eiternde Geschwüre, die sogenannten „Dasselbeulen“. Haben sie dort ihre Entwicklung vollendet, so durchbrechen sie die Haut nach außen, lassen sich zur Erde fallen und verpuppen sich in dieser, um nach einiger Zeit als fertiges Insekt zu erscheinen. Eine der gewöhnlichsten ist die Rinder-Dasselfliege oder Rinderbiesfliege (vergl. bunte Tafel VII. 2), die einer Hummel sehr ähnlich sieht; sie hat aber zwei Flügel, während die Hummel vier hat.

Die Pferdemagenbremse (vergl. bunte Tafel VII. 3) klebt ihre Eier den Pferden mit etwas Schleim an die Haare der Brust und des

übrigen Vorderkörpers. Ist das Ei nun reif, so bringt die warme Zunge des Pferdes, wenn es sich beleckt, dasselbe zum Platzen. Die Made bleibt daran kleben und gleitet in den Magen des Tieres hinunter. Hier oder im Darme befestigt sie sich mit ihrem Mundhaken, verpuppt sich dann, und die Puppe gelangt mit dem Kote ins Freie.

Das beste Mittel gegen diese Made ist, die Haut des Pferdes rein und das Haar kurz zu halten. Diese Magenbremse ist etwas größer als die Stubenfliege, sieht meistens bräunlichgelb aus und hat einen stark behaarten Körper.

Eine andere Familie der Zweiflügler sind die Mücken. Sie haben einen dünnen, schlanken Körper und fadenförmige Fühler. Wir haben über die gemeine Stechmücke im zweiten Buche gelesen, aber ihr solltet noch eine andere Art kennen lernen, die Weizen und anderes Getreide angreift.

Die zitronengelbe Weizengallmücke ist ein kleines Insekt, das ungefähr die Größe einer sehr kleinen Stechmücke hat. In der Frühe eines Junimorgens, wenn die Weizenblüte sich entwickelt, kann man diese Mücken von den Halmen schütteln und sie dicht über dem Boden umherfliegen sehen. Die Weibchen haben eine scharfe, haarfeine Röhre, mit der sie ihre Eier in die Blüten der Weizen- und seltener der Roggenähre legen. Dort kommen aus ihnen kleine gelbe Maden aus, die sich von dem Fruchtknoten nähren und dadurch die Körnerbildung verhindern. Sie vernichten auf diese Weise oft einen großen Teil der Ernte.

Ihr solltet auch die Larve der Bachmücke oder Kohlschnake kennen, die in Gärten und Kohlfeldern Schaden anrichten kann. Wenn ihr eine Schnake an einem Grashalm hängen seht, so ist sie höchst wahrscheinlich gerade dabei, mit ihrer Legeröhre Eier in den Boden zu legen.

Aus diesen kommen beinlose braune Maden aus mit starken Kiefern und einem Paar kurzer Hörner. Man kann sie beim Umpflügen eines feuchten Feldes finden. Man findet auch wohl die harte Puppe, die wie eine Schnake mit zusammengefalteten Flügeln geformt ist; die Beine sind zusammengezogen, und die beiden

Hörner sitzen schon auf dem Kopfe. Sie hat Dornen an ihrem Hinterleib, mit denen sie sich an die Erdoberfläche hinaufzieht, wenn sie sich verwandeln will.

Man wird die schädlichen Larven am besten los, wenn man den Boden tief umpflügt und die Eier oder Maden vergräbt, so daß sie sterben oder nicht an die Oberfläche gelangen können; man kann auch eine Lösung von Gaskalk oder einer anderen für die Insekten tödlichen Flüssigkeit auf das Land spritzen. Stare erweisen sich gegen diese Schädlinge sehr nützlich, da sie die Maden aus dem Boden ziehen und vernichten.

Suche Made und Puppe der Schmeißfliege. Untersuche Beine, Körper und Rüssel einer Schmeißfliege. Versuche Eier der Stubenfliege zu finden. Suche eine Pferdebremse sowie die Rinderdasselfliege und Pferdemagenbremse. Suche eine zitronengelbe Weizengallmücke und ihre Made; ferner die Made und Puppe der Bachmücke.

L e k t i o n 11 .

Heimchen und Heuschrecken.

Bei allen Insekten, von denen wir bis jetzt gehört haben, sind die Larven von dem voll entwickelten Insekte ganz verschieden. Aber junge Heimchen und Heuschrecken sehen, wenn sie aus dem Ei kommen, fast ebenso aus wie das ausgebildete Insekt, abgesehen davon, daß sie kleiner sind und keine Flügel haben. Sie springen, fressen und benehmen sich genau so wie die Alten. Sie häuten sich vier- oder fünfmal. Nach der letzten Häutung kann man die Flügeldecken unter der Haut sehen, und sobald diese zerreißt, breiten sie die Flügel aus und fliegen.

Wenn man sich einen Käfig aus Drahtgaze macht, einige junge Heimchen hineinsetzt und sie mit Küchenabfällen füttert, so kann man diese Verwandlungen beobachten. Aber man darf es nicht mit einer Bedeckung von Musselin versuchen wie einer meiner Freunde, denn die Heimchen haben starke Kiefer und fressen sich bald hindurch.

Tafel VIII

1. Grüne Heuschrecke Weibchen mit Legeröhre.

2. Kleine Heuschrecke. 3. Feldgrille. 4. Langflügelige Heuschrecke. 5. Flügellose weibliche Heuschrecke.

Die kleinen grünen Heuschrecken sind leicht auf den Feldern in großer Anzahl zu finden, aber das große grüne Heupferd (vergl. bunte Tafel VIII. 1) ist nicht so häufig. Wenn ihr aber wißt, wo ihr suchen müßt, wird es euch nicht schwer werden, eins zu fangen. Es ist sehr lehrreich, dieses Insekt zu untersuchen. Der Kopf ist von der Brust scharf getrennt. Es hat zwei lange Fühler, die nach hinten über dem Körper liegen. Seine Kiefer sind sehr stark, und wenn man ihm ein Blatt unter einem Glase zu fressen gibt, so kann man sehen, wie sie sich seitwärts bewegen, um die Nahrung zu zerkleinern; man

kann auch die Ober- und Unterlippe erkennen, durch die die Nahrung zu den kauenden Kiefern im Innern hindurchgeht.

Wenn ihr ein Weibchen gefangen habt, so werdet ihr sehen, daß es eine lange Legeröhre hat, die es in den Boden bohrt, um seine Eier zu legen. Hieran könnt ihr beobachten, wie die kleineren Insekten es machen.