Introduction

Divorce is with us. In both popular literature and scholarly publications the consensus is that the divorce rate in the United States is between 40% and 50%, which means that 40–50% of the children born to families in the United States will have to cope with and adjust to divorce (www.apa.org/topics/divorce).

Also, that rate increases as people remarry, where the second marriage is even more likely to dissolve into divorce.

In my private practice, I began as a play therapist and then a marital counselor. I spent years in the schools and in my practice working with children who were from families that were breaking or broken. These children were often caught in the middle between parents who were having grave difficulty in their marriages. Work with the children was often frustrating because the children were so tuned in to their parents’ struggles, and I could not effect change without dealing with the whole family system. So, I began to work with couples, hoping to make a difference and provide some help indirectly for the children. My orientation in couples work is Emotion-Focused Couples Therapy (Greenburg and Johnson, 2010). I used attachment theory and concentrated upon renewing emotional bonds between parents and spouses. In this Emotion-Focused work, it became clear to me that attachment is essential to emotional health.

Four years ago, I had a revelation. The children that I was seeing and that my colleagues were seeing, who had experienced the divorce of their parents, seemed to have a pattern. No matter how long ago their parents’ divorce had taken place, the children of these families would present with challenges when their parents were litigating. The children whose parents were embroiled in custody battles seemed to be having great difficulty. They were presenting as being emotionally healthy or unhealthy in conjunction with the relative health of their biological parents’ relationship. In addition, often the parents would

attempt to use me and my colleagues to obtain custody. They asked for our testimony in court. This put us in an untenable situation, as we are not custody evaluators. We are counselors. These custody battles were some of the most challenging cases because seeing the child often did not help the parental relationship, and most divorced people did not want to visit with us together. It resulted in a “he said, she said” situation. All the while I became more and more concerned about the disrupted attachment experienced by the children of divorce.

Dr. Edward Farber, in his book Raising the Kid You Love With the Ex You Hate (2013), states that there is a direct correlation between a child’s adjustment to divorce and the civility with which the parents treat each other. I have found in my practice that this is true and that this is not as much dependent upon the “age” of the divorce, but on the relationship of the parents. In other words, even if a parent has been divorced for 15 years, if he or she has an acrimonious relationship with their ex, the child will be adversely affected and have difficulty adjusting. I have seen divorced couples that have been divorced for over 11 years who continued to fight over issues related to their children. The children were reacting to the disruption of their secure base (their parents’ relationship).

As a result of dealing with custody issues and post-marital conflict, I began to rethink how to approach divorced families. Historically, a child would be presented as the Identified Patient, and I would do play therapy and then include Mom and Dad separately in the therapy process. It was frustrating because the parents often parented their children very differently from each other. And this imbalance encouraged an unhealthy dynamic in the children, who seemed to be juggling two sets of emotions: Dads’ emotions and Mom’s emotions.

Divorce is an incredibly emotional experience. Two people who have been woven together are unraveling their lives. It is messy and it is painful, even if it is warranted. When the idea of parenting with the ex-spouse is introduced, the messiness multiplies. In my practice the children that I was seeing were the ones caught between two hurting people. These wounded people were being asked by the court to do the most difficult task of their lives, together with someone that they could not get along with, did not see eye to eye with, and often hated. This most difficult task is parenting. I began to explore the idea that parenting together after divorce must be nearly impossible without some help and guidance. I researched the written materials, and there are several very good books (see the Bibliography) on how to navigate divorce and co-parenting.

These are written for parents who want to do well parenting after divorce. I saw that there are group programs to educate divorced people. These group programs are the norm. But these did not seem completely effective, especially for those parents who have great difficulty parenting together. It seemed to me that people can hold their breath and play on their phones in a group class, with no personal investment or challenge. People in high-conflict divorces are generally stuck in such a negative interaction cycle that a group will not break through the pattern. My Emotion-Focused Therapy training taught me that de-escalation of the negative pattern is essential for relational health, so I began to wonder how I could assist these couples in de-escalation when there was no connection, and where it was not advisable to keep emotional connections.

Most divorced people who do well in parenting together are those who are motivated to read the books and attend the groups. But what about those parents who are so hurt and angry that they cannot?

These were the parents that I saw in my office often. And these were the parents who could not navigate parenting together. There was no program mandated in my state (Arkansas) that would help the couple face their negative patterns personally in a safe environment. The only alternative was personal reading of “how-to” books and attending group classes. So, I developed a program. Interestingly, as I have developed the program I have found that even the seemingly civil divorced people have trouble parenting together. Actually, married people have trouble parenting together. Why should it be any different for divorced people?

I approached the Benton County Arkansas Family Court judges with my idea. These judges seemed to be in a quandary when awarding joint custody, because often couples would litigate several times after the original divorce decree and custody settlement. This was understandably frustrating to the court. I offered a personal program to both educate and support divorced and divorcing couples, which would shift their focus off themselves and their own hurt onto their children who were being negatively affected by their conflict and litigious lifestyles. That was almost four years ago. These couples make up over 50% of my practice. I count it an honor to help these parents navigate what I would say is the most difficult challenge of their lives. I see it as family work and as protective work for the children.

My background is in play therapy. Play therapy, like EmotionFocused Couples Therapy, emphasizes attachment. Attachment is at the base of all safety and security. The work of John Bowlby et al. (1986)

bears this out. Attachment is what is directly threatened in a highconflict divorce situation. Children lose their secure base when Mom and Dad separate and the child is suddenly living in two worlds. Safety and security are the most essential elements of a child’s life and these are threatened when parents divorce. Safety and security are the essential elements that provide children an atmosphere in which to learn and grow.

Dr. Robert E. Emery (2016) has developed a hierarchy of needs for children of divorce. In this hierarchy, survival and safety are at the base. Divorce directly attacks a child’s sense of safety and security. When attachment is disrupted, children react. In the chaos that divorce often brings, sometimes children’s feelings are not at the forefront. I wanted to somehow reach parents where they attach to their children, where they are still loving someone, so that post-divorce they can transform their pain into concern for those whom they truly love and are committed to. This might be the key to renewing safety, security, and secure attachment.

This is a particular challenge because divorce is the dissolution of a very strong attachment. Divorce in itself needs an attachment to die. But in the face of this there are children who cannot bear the death of attachment. It is a dichotomy that has to be faced and navigated if children are to have normal childhoods. As Dr. Emery (2016) says, every child must be able to have a normal childhood. In their landmark study on divorce, Wallerstein, Lewis, and Blakeslee (2000, preface) state, that

Divorce often leads to a partial or complete collapse in an adult’s ability to parent for months and sometimes years after the breakup. Caught up in rebuilding their own lives, mothers and fathers are preoccupied with a thousand and one concerns, which can blind them to the needs of their children.

Such disruption in parents’ lives often results in parentification and isolation of children. This is precisely what must be derailed in and after the divorce process. So, after divorce, the task of parents is to allow one of the strongest attachment of their lives to die, and to enhance the secure attachment of their children at the same time. How difficult a task is this!

There is tremendous loss in a divorce. Perhaps the greatest loss is the loss of involvement in the children’s lives. This is often something not well thought out in a divorce. It is also something that often turns into

a competition for the children’s loyalties and affections. Unfortunately, parenting post-divorce is not a competition. But both parties in the divorce, because they have agreed to a divorce, have voluntarily agreed to forfeit some time with their children. (The exception would be in cases of child abuse and termination of parental rights.) Most divorced people do not have this at the forefront of their thinking. When faced with the fact that on Saturday they will not be at the breakfast table with their babies, they are not thinking that this is their choice. It is quite the opposite. Many are thinking about how they can get more time, or somehow change the circumstances so that they have more time, an arrangement that looks more like they have the children every day. This results in competition. Often in the volatile relationship between exes, parents withdraw their involvement to remove themselves from conflict (Emery, 2016) and to get away from the pain of the reality of their loss of time with their children. This has an adverse effect upon a child, who may interpret this withdrawal as rejection. So, we are left with interrupted attachment, and a sense of abandonment in the child. Or we are left with two parents fighting and competing for time, with multiple litigations and thousands of dollars spent.

One might argue that the type of intervention I propose is only necessary for toxic relationships. I would say that every divorce has the potential for toxicity because it is the dissolution of attachment, which is both grievous and potentially toxic. I have found in my work that even the most civil of dissolved marriages are fraught with hurt. This hurt is precisely what seems to motivate parents to fight over custody and to unwittingly create conflicts of loyalty and alignment in their children.

So, co-parenting is a necessary journey, which divorced parents must navigate together after divorce. What is co-parenting? The mid1990s marked the beginning of the co-parenting movement (McHale, Kuersten, & Lauretti, 1996). This was focused on two-parent families initiating two-house living and parenting. Co-parenting in the twenty-first century can be defined in a broader sense as parenting cooperatively with others. These “others” may be ex-spouses, grandparents, or significant people in a child’s life. In my practice I have worked with grandparents who have joint custody of children whose parents are deceased, and the issues are much the same as issues faced with the traditional two-parent divorced family. Elements of loss, competition, and insecure attachment are all present. McHale and Lindahl (2011, p. 4) state that “This basic notion—that children are part of a family relationship system in which they are simultaneously cared for

and socialized by multiple parenting figures—is at the core of modern co-parenting theory and research.” In other words, the family system as we have known it historically is changing. More people are involved in the care and raising of children, and co-parenting concepts often apply to all, rather than just to Mom and Dad. McHale and Lindahl state aptly (2011, p. 10):

Co-parenting alliances can function as resources in all manners of family systems for virtually every child—whether that child is raised by a married heterosexual mother and father or by any and all other honorable sets of individuals who step forward to assume and share the responsibility for the child’s care and upbringing.

In my practice I have found that the principles and practices I instill in parents are applicable to any family system struggling to come to a unity of purpose and effectiveness.

So, co-parenting can be defined as a “joint enterprise” (McHale and Lindahl, 2011, p. 16) between adults who have banded together to raise and care for common children. In essence it is a family system where two or more individuals have taken on the job of parenting children, outside of the traditional two-parent, married-couple model, or within the two-parent system, post-divorce. The distinguishing factor of a co-parent is his or her consistent emotional involvement with the child(ren). In this manual the idea of co-parenting is assumed to be post-divorce, and/or when there has been a disruption in the consistent care of children where there has been the loss of one parent, both parents, or a radical change in parenting structure which requires an emotional adjustment outside the norm for the children. This could also include non-marital parenting of children when the parents are not co-habiting.

Why is co-parenting education and training so important? First of all, children who have experienced divorce and radical change are often traumatized by the changes and loss they are experiencing. In The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce, Wallerstein, Lewis, and Blakeslee (2000) conclude that the effects of divorce are so far-reaching that the final effects are not even visible until children grow up and have intimate significant relationships as adults. And then, there can be devastating effects. Effective co-parenting can stave off many of the negative effects of divorce by developing a new secure base for the children after the divorce. Most negative effects that children experience are related to insecurity, not belonging anywhere after the divorce, and becoming

xv inappropriately triangulated into the litigious or negative relationship between their mother and father. Parent education which pinpoints the effects of negative behaviors in the parent relationship and which guides parents to develop new skills may well prevent some trauma that has been historically normal for children of divorce.

Some states require parent education after divorce. Oklahoma and Maine are two states that have programs which require divorcing couples to be educated in the effects of divorce on the children and in developing a co-parenting relationship. Maine uses a program called I-COPE, which is an “intensive 9 week course, which utilizes psycho-education and emphasizes changing behaviors” (www.kidsfirstcenter.org/forparents.html#coparenting). In Maine parents are court-ordered to attend these group sessions together and there have been positive outcomes. In Oklahoma parents who are divorcing are required to take a group class prior to or directly after divorcing (www.tulsaworld.com/homepagelatest/new-oklahoma-law-requires-class-before-many-divorces/ article_be443a5a-db28-5f84-81a4-86186ca20d7e.html). The parents may attend together or separately. California, Utah, Missouri, and many other states require and/or offer classes in co-parenting. Some of these classes are offered online. All of the face-to-face classes are offered as a group.

The program I have outlined is unique because the divorced parents are required to attend together without a group, in my therapy office. I operate from the premise that these people will be required to be “in the same room” for many events in their children’s lives after their divorce. I consider it to be practice for parents getting used to being together after divorce. The program is also designed to get the parents some necessary experience in communicating about their children after divorce. Many of the parents I see have not been in the same room communicating for weeks, months, and sometimes years. The program is designed to both educate and challenge the individual parents to develop communication skills and common decency with regard to each other.

Many divorced people come to therapy to work through their own grief and trauma post-divorce. This program is not a substitute for personal processing of loss. Instead it is an opportunity for the divorced couple to be educated about divorce and its effects upon them and their children, and to develop a new pattern of relationship which is de-escalated and which focuses on what is in the child’s best interest. It’s a transitional tool for parents to move out of grief into action in parenting. It also affords divorced parents a safe place where

their parenting concerns can not only be heard (as they would be in individual therapy), but also addressed in the presence of a trained professional. Another benefit is that an ongoing relationship can be developed between the couple and the therapist so that any future stalemates can be addressed with the therapist. This program is yet another support for the divorced and divorcing person. Given the fact that adjustment to divorce is an ongoing process (consensus says that it takes up to two years), another support specifically geared toward the parenting relationship is warranted.

1 This Is Not Post-Divorce Therapy

In the first session we set the stage for providing a safe place for the couple to work through their parenting differences and lay a foundation for the development of a workable parenting plan. There should be an emphasis on the fact that they will be parenting together until either they or their children die. In most cases this is over 30 years. In those 30 some years there will be countless family celebrations and gatherings where they will have to be side by side. There will be weddings, graduations, funerals, births, concerts, award ceremonies, and sporting events, not to mention funerals and regular holidays and birthdays. (Many couples opt to celebrate children’s birthdays together, at least in the early years after a divorce, if the children are younger.) I usually give the example of a young couple that is in a quandary because they are in love, ready to get married, and afraid to invite their parents for fear of a scene. The couple needs to get a vision for the fact that this co-parenting is a lifelong process and that divorce didn’t negate this responsibility. If anything, divorce makes the process of parenting more difficult. It is important that the therapist realize how challenging this situation may be for the couple. They may have had a contentious divorce, which may have been followed by years of litigation and contention regarding the children. (Often couples are court-ordered to come to me after they have been divorced for years, and litigated intermittently throughout those years.) Particularly in court-ordered situations, both parties may have a long history of negative interactions. These interactions may have been fraught with contention and bitterness. They may be embroiled in litigation presently, fighting for custody of the child/children. They may not have been in the same room since their divorce was finalized. Or they may be in the throes of divorce proceedings and there may be a world of hurt between them. In few cases there may be a history of emotional and/or physical abuse. (If these cases are not corroborated

by the court, this fact does not negate a person’s personal experience.) In short, this is a really hard thing for them to do. It takes a tremendous amount of courage to come into a therapist’s office with an ex-spouse, especially if it is court-ordered.

The first session is an opportunity for the therapist to allay fears and set ground rules so that the couple can actually get to work. It is also a session where the therapist begins to affirm both parents and commend them for the courageous act of coming to co-parenting. It is essential to remember that these clients are uncomfortable and frightened. If they are in litigation they may be very wary of you as a therapist, and they may wonder if what they say might be used against them. They may be frightened that abuse will happen in your therapy room, and that they will not be protected. So, there is a lot to be careful with and sensitive to as a therapist.

First, ground rules for the therapy must be set. The couple needs to be informed of the sequence of the sessions and what will be expected of them. They need to know that there are four psycho-educational sessions aimed at educating them about divorce and its effects upon them and their children. They need to know that they will not be expected to really interact in the first four sessions, and that you will be talking to them and discussion will be limited. This format gives the couple some time and experience to feel the safety of space that you have created. This four-session hiatus on discussion allows the couple to begin to get used to being in the same room without arguing or being threatened. Many couples will ask if they can see you individually first. I have a policy that I will not do this until the psycho-educational sessions are finished. The reason for this is that during the first four sessions they will be taught and challenged to change their stance toward each other, and if they meet with me individually sooner, they will only air their grievances and it will not necessarily be helpful. The first four sessions give a backdrop to their relationship with each other, and often soften parents’ attitudes toward one another. These first four sessions provide an example of what it is like to be safe with each other. Discussion is very limited and I maintain control of these sessions to assure emotional safety for all.

It is essential to begin with “informed consent”. Confidentiality and neutrality must be discussed. I make a point of saying that I am not on either side, and that I am there for their children, to help them be the best parents they can be considering their situations. The focus of the therapy process is on developing a good and workable co-parenting

relationship, which can be sustained for years. It is important that you share any personal history of divorce and co-parenting or that you have working with children of divorce or divorced couples. In any case, it is important to use your own experience and “heart” to win the couple over to the therapeutic process. These people are not coming as “normal” clients do, to hopefully find someone they can trust and who will help them. Instead, they are coming with mistrust and a healthy cynicism about what may or may not happen. Whatever distrust they have for their ex-spouse will be projected in the therapy room. This is not something that needs to be dealt with face on. Rather, be aware and realize that it will hopefully dissipate as we process co-parenting. So, initially, the process should be outlined as a number of psychoeducational sessions (four), individual sessions (one each), and sessions where a practical co-parenting plan is authored by the parental dyad (one to four, depending on the couple), and a family session focused on reconciliation. I emphasize that the first four sessions are designed to include very limited discussion, if any. And I assure them that before we begin the co-parenting plan creation, they will have an individual session where they can share their concerns personally with me. You are giving the couple an overview of what this will look like. This will allay their fears to a certain extent.

The first proclamation in this process is that co-parenting therapy is NOT post-divorce therapy. Express that your expectations are not to make another marriage, but rather to help the couple learn to parent together. These people are being asked by the court, or by their own situations, to do the most difficult task imaginable, parenting, with someone that they have lost love and trust with. What a scary journey! Being in your office may be a definitive act of courage, which speaks volumes as to their love for their children. And this is your focal point: Their love for their children. The therapist focal point is “the benefit of the children”. This will be revisited over and over again.

Begin the first session with a genogram or timeline of their relationship. You want a bird’s-eye view of the situation in which these people are attempting to parent. This genogram also refers to the shared history of the couple, which will lend insight into the major issues of any brokenness in the co-parenting relationship. You also need to know the outside influences and challenges that will affect/ have affected the parenting process. This should include how many years they have been married, previous marriages, how they met, how many children (ages, grades, situations), other children from other

marriages, grandparent relationships and how involved they are with the children, any exposure to domestic violence and/or addictions, and who else is involved (relatives, step-parents, and significant others). You will want to know the present custody arrangement. If at all possible, having a copy of the court documents pertaining to divorce and custody will help you to understand the situation. You will also want to ask if they are presently litigating and what outcomes they hope for. Although this is a somewhat sensitive question if couples are in the midst of a current litigation, it is helpful to recognize the elephant in the room, and acknowledge it. At this point I also point out the difference between the role of a lawyer, which is to help them win their case, and my role, which is to help them to come to a conclusion together. I emphasize the importance of their lawyer’s protective role in a legal action, and I reiterate that I am not taking sides, and that they will do well to work together. I often point out that if they have litigated more than once, they have spent their child’s education. I also point out that litigation takes on a persona of its own, and often makes the animosity between co-parents worse. I warn them to be protected by their counsel without becoming more acrimonious. It is important to note that as a co-parenting therapist your stance must be neutral. You cannot take sides, although you may be sorely tempted at times. Both members of the parental dyad must feel safe with you. This is a difficult task because often co-parents come to your office because they have been court-ordered or because they want to use you in their particular agenda. It is often a minefield. Also, therapists, as in any type of therapy, have to face their own countertransference issues. Personalities and personal experiences can all contribute to our reactions. It is important to maintain an open stance toward each parent. In the first session I openly ask the couple how they communicate and how they are getting along. Often they tell me that they are not getting along, or that they only communicate by text or phone or e-mail. It should be noted that more often than not, in high-conflict divorce situations, one parent will accuse the other of being a narcissist. The only diagnosis that should be taken seriously and addressed is a diagnosis shared by a psychologist who has evaluated the individuals. Terms like bipolar and narcissist are common by-words used by non-professionals. Releases of information should be obtained to gain insight from the children’s therapists, ad litem attorneys, and psychologists and counselors who are familiar with your clients. These may be helpful to assist in developing a supportive perspective toward your clients.

After getting a thorough history, there are several essential points to communicate. These should be covered in the first session after obtaining a history and genogram. First you set the stage by being empathetic with their loss. Educate them that divorce is a great loss. Encourage them to grieve. One cannot parent effectively after divorce until the co-parent has allowed him/herself to grieve over his or her own losses resultant from the divorce. When divorce happens, even if it is a divorce that each parent agrees with and feels is necessary, there are great losses. Parents may lose property and things. They lose the dream that they would make a life with, and grow old with, the partner. They may lose friends who often scatter due to being uncomfortable. They may lose their home. They may lose a friend and lover. But the greatest loss, which is often not addressed, is the loss of their right to see and be with their child every day of their life. When they divorce they willingly give up time with their child, no matter what the custody arrangement is and no matter who has “primary custody”. This is the painful truth that they are confronted with in co-parenting therapy. This is where bitterness, anger, fear, and mistrust crop up. It is essential to express to the couple that unless they allow themselves to grieve through their losses, resentment and anger will leak into their parenting and this will be destructive to their children. Divorced people can carry anger and resentment and hurt even if they have moved on to new relationships. It is important to note this and to encourage each parent to seek their own counsel and comfort for these issues. Professional and non-professional help can be therapeutic, as long as the parent has allowed him/herself to grieve. I emphasize that grief is the doorway to moving on from the pain and hurt of divorce to developing a new life.

The second point which is made is that their child/children have only one mother and one father and that is them. I point out that the children may have wonderful role models in aunts and uncles and grandparents and step-parents, but they are the only biological parents that the children have. In cases of adoption I emphasize that they are the parents responsible for the child/children. Because of this, it is important they cultivate a healthy respect for each other in this position. I point out that they cannot parent the child/children alone. They are the most important people in their children’s lives, and they are essential to their growth and wellbeing. Their children need them both. And whether or not they like it, they will be parenting these children together for their whole lives. They simply cannot negate the fact that having children ties them inextricably together for the rest of their lives. So, it is essential that they develop the ability to

appreciate each other in the parenting role. Dad must respect Mom in all of her “Mom” wisdom. And Mom must respect Dad in all of his “Dad” wisdom. I point to Mom and state that she has Mom wisdom and understanding, and I point to Dad and state that he has Dad wisdom and understanding for the child/children. It is possible that either parent may actually be an insensitive or bad parent. But the fact is that they are a parent to the child/children and they do have some creative voice in the parenting process, no matter how they have failed in the past. I emphasize that this respect for the other is based on the person’s position in the child’s life, that of mother or father, not on good character or successful choices. In addition, the child needs to recognize this mutual respect for his or her own successful development. The fact is that when most couples seek this therapy they have no respect for each other in any area. It is likely that one or the other has had a track record of earning the opposite of respect from their ex-spouse. Co-parenting therapy will hopefully change this course and assist the parents in separating their own issues with each other from their parenting practices. In this session I introduce the concept of emotional neutrality. After the grieving process it is possible for these people to pull away emotionally and begin to develop mutual respect. That leads into the next point. Co-parents are charged with responsibility for the safety and security of their children. Divorce disrupts a very basic secure base, which the child has depended upon, perhaps foryears. When parents separate and divorce, changing the landscape of the child’s home and life, the once known secure base is altered immeasurably. The child’s “normal” changes completely. Even if the marriage of the parents was not ideal and the child was exposed to fighting or animosity, that was the child’s secure base, the only secure base that the child has known. Separation and divorce shift reality for the child, and for a time, that child is left hanging without a secure base, wondering where he/she belongs and where he/she can rest. Often the child will gravitate toward school, favorite coaches and teachers, friends and their families. All of this is an effort to re-invent security. Especially in an acrimonious divorce, the children are challenged to find security elsewhere. Here we introduce the idea that it is the co-parents’ responsibility to provide safety and security for their children and to define what this looks like for them. Figure 1.1 shows a series of three sets of circles. The first set depicts a safe and secure family. Two rings intertwine like a Venn diagram with parents and children depicted. This is what children perceive as safe and secure: Mom and Dad in the home and everyone emotionally attached. This is a picture of the child’s secure “normal”.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

By courtesy of the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Co.

108. The Koenig Wilhelm, German Navy

The Baden, German Navy

112. H.M.S. Dreadnought

113. H.M.S. Lightning, torpedo-boat

114. H.M.S. Tartar, torpedo-boat

115. H.M.S. Lord Nelson

116. H.M.S. Invincible, armoured cruiser

The last nine from photographs by G West and Son

117. The Minas Geraes, Brazilian battleship

By special permission of the Brazilian Naval Commission, from a photograph kindly supplied by Messrs Armstrong, Whitworth and Co 118. The Kearsarge, U.S. Navy

By courtesy of Messrs. Osbourne Graham and Co.

123. The old Floating Dock at Rotherhithe, circa 1800

By courtesy of Messrs. Clark and Standfield

124. Model of the Bermuda Dock

From the original at South Kensington

125. Self-docking of the Bermuda Dock (well heeled)

126.

The last four by courtesy of Messrs. Clark and Standfield

129. The Baikal

By courtesy of the Magazine of Commerce

130. The Drottning Victoria To face 366

From a photograph by Frank and Sons, by courtesy of the Shipbuilder and Messrs. Swan, Hunter, and Wigham Richardson

131. The Ermack

face 370 By courtesy of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth and Co.

132. The Earl Grey

By courtesy of the Magazine of Commerce

133. The Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert

134 The Imperial Yacht Hohenzollern

PLANS

135. The Evolution of Floating Docks, 1800-1910 389

By courtesy of Messrs. Clark and Standfield

CHAPTER I

PRIMITIVE EXPERIMENTS IN PROPULSION SOME EARLY EXPERIMENTS WITH STEAM

pinions are divided as to whether the paddle-wheel is a development from the action of a man paddling a canoe, or the result of applying to a vessel an ordinary wheel, with blades to make it bite the water; or it may be stated thus: Did the paddle-blades grow out of the wheel, or the wheel out of a number of paddle-blades? There is no satisfactory evidence one way or the other; suffice it that the idea of revolving paddles was developed.

How the power which caused the revolution of the paddles was applied at first is as unknown as the identity of the man who first thought of making navigation easier by mechanical means. It was probably human power, as the first inventor can hardly have discovered how to utilise animals for the purpose, and from what we know of primitive expedients we may conjecture what the first contrivance used to urge a boat onwards without sails or oars was like. The craft would be a small one. Perhaps the proprietor was too poor to hire rowers. Perhaps, a subtle financier, he realised that if he could bring his goods to a certain place before rival shippers he would secure the market. Hence, stimulated by poverty or cupidity or both, he reflected, experimented, and finally invented the revolving paddle. But his apparatus was probably nothing more than a smooth, straight branch or tree log, which projected over either side of the boat and carried at each end paddles fixed radially. He probably used two or four paddles, as it would be easier to attach them to the axle in pairs. The radii of the paddles consisted of two poles tied at right angles about the middle and there fastened to the axle ends, rough-hewn boards or strips of bark being attached at the extremities of the poles to form the paddle-blades. The axle was doubtless kept

in place either by pins in the gunwales placed before and after it, or by bringing two of the ribs on either side above the gunwale line and disposing the axle between them. In many modern row-boats one or other of these plans is adopted for the accommodation of the oars or sculls. This much being accomplished, it only remained to apply the power. The inventor now passed a rope twice round the middle of the axle, and tied the ends together. By hauling on it he got all the power he was likely to require; to go astern he had merely to pull the rope the other way. If more power was required more men tugged at the rope.

When paddles were made larger to suit hulls of larger dimensions, it may fairly be assumed that a winch turned by several men was used, and that the power was transmitted to the axle of the paddle by means of an endless rope. But soon it occurred to the shipowners that animals might be used to produce the power instead of men. Horses or oxen were made to drive a turntable or capstan, to work in a cage after the fashion of white mice in their cylinders, or on a moving floor which imparted its motion to an axle connected by an endless rope with the axle of the paddle. Such boats, deriving their power from animals, were built by the Romans, were in use in the early centuries of the Christian era, and were not unknown in the nineteenth century in Britain and the United States.

P�������� P�����-�����.

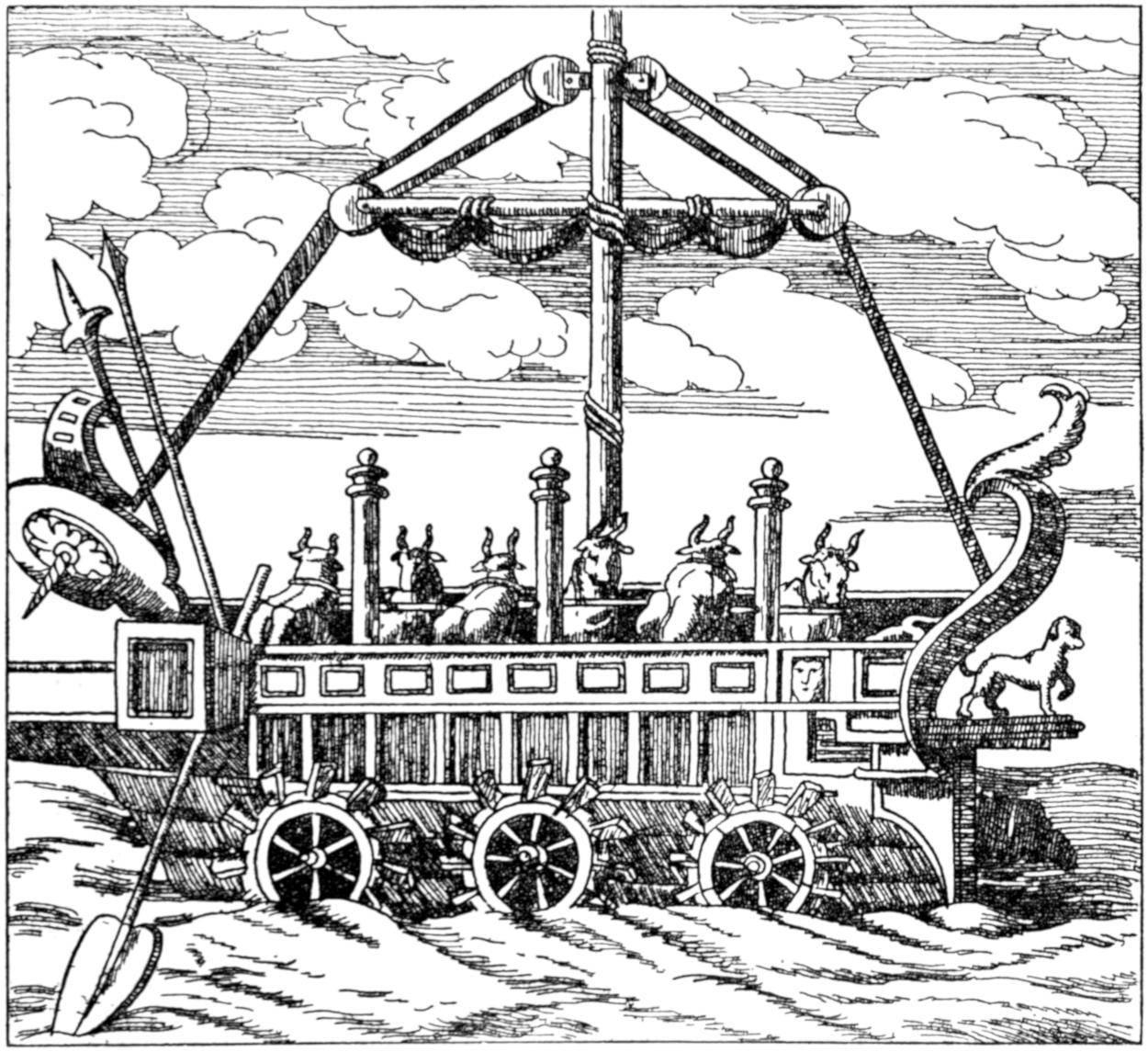

From Valturius’ “De Re Militari,” 1472.

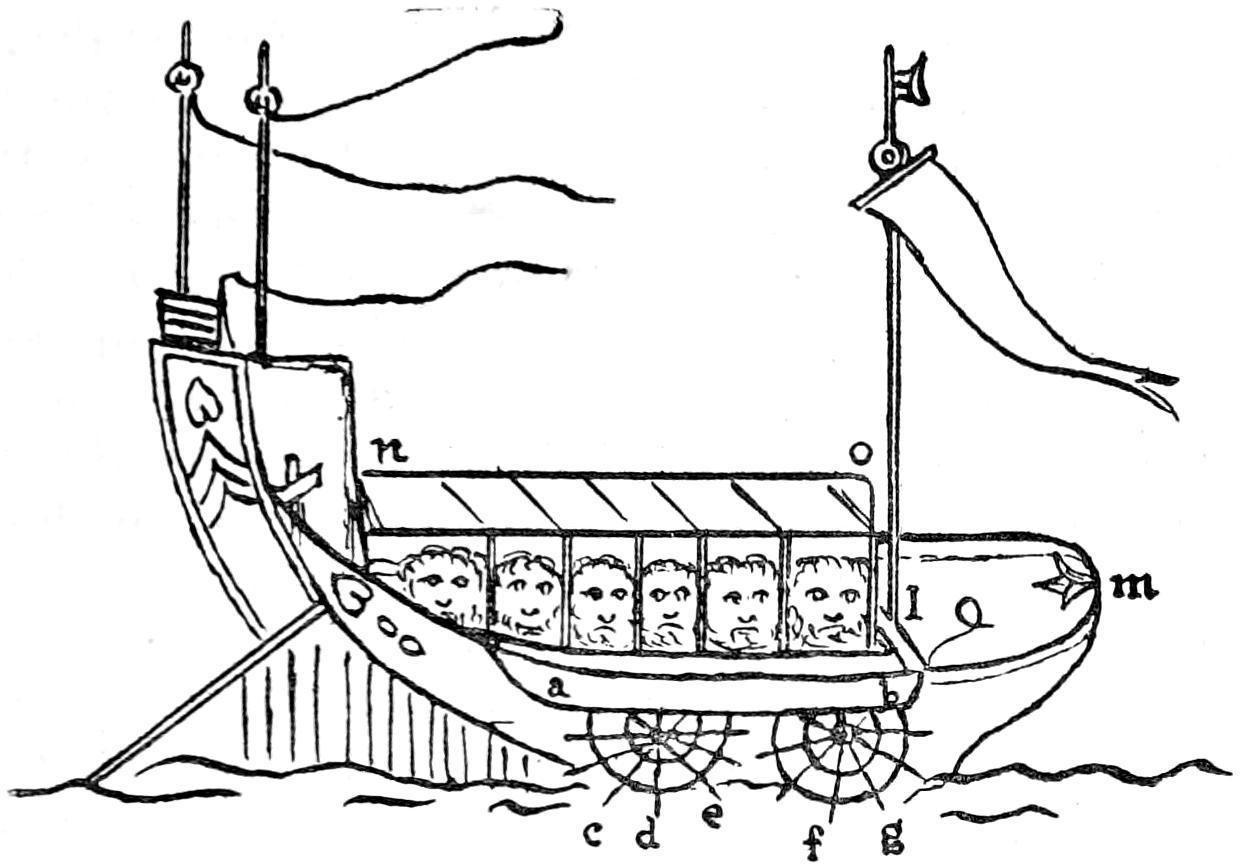

One of the earliest authentic records of a vessel fitted with paddlewheels is to be found in Robertus Valturius’ “De Re Militari,” published in 1472, wherein are pictures[2] of two boats, one of which has five pairs of paddle-wheels, and the other one pair. Modern engineers know by experience that if two wheels be placed one behind another—and in the early days of steam navigation several boats were equipped with two pairs of paddle-wheels—the hinder wheels, having to work in disturbed and moving water, are practically useless. But at the time of which Valturius writes the wheels were so small, the number of revolutions were so few, and the propelling power they exerted so slight, that no wheel was likely to have its efficiency much interfered with by any number of wheels in front of it. The wheels had four paddles each, and were revolved by cranks on their axles, the cranks of the ten-wheeled boat being connected by a rope to give uniform action.

[2] The designs have been attributed to Matteo de’ Pasti, who lived at the court of Malatesta (d. 1464).

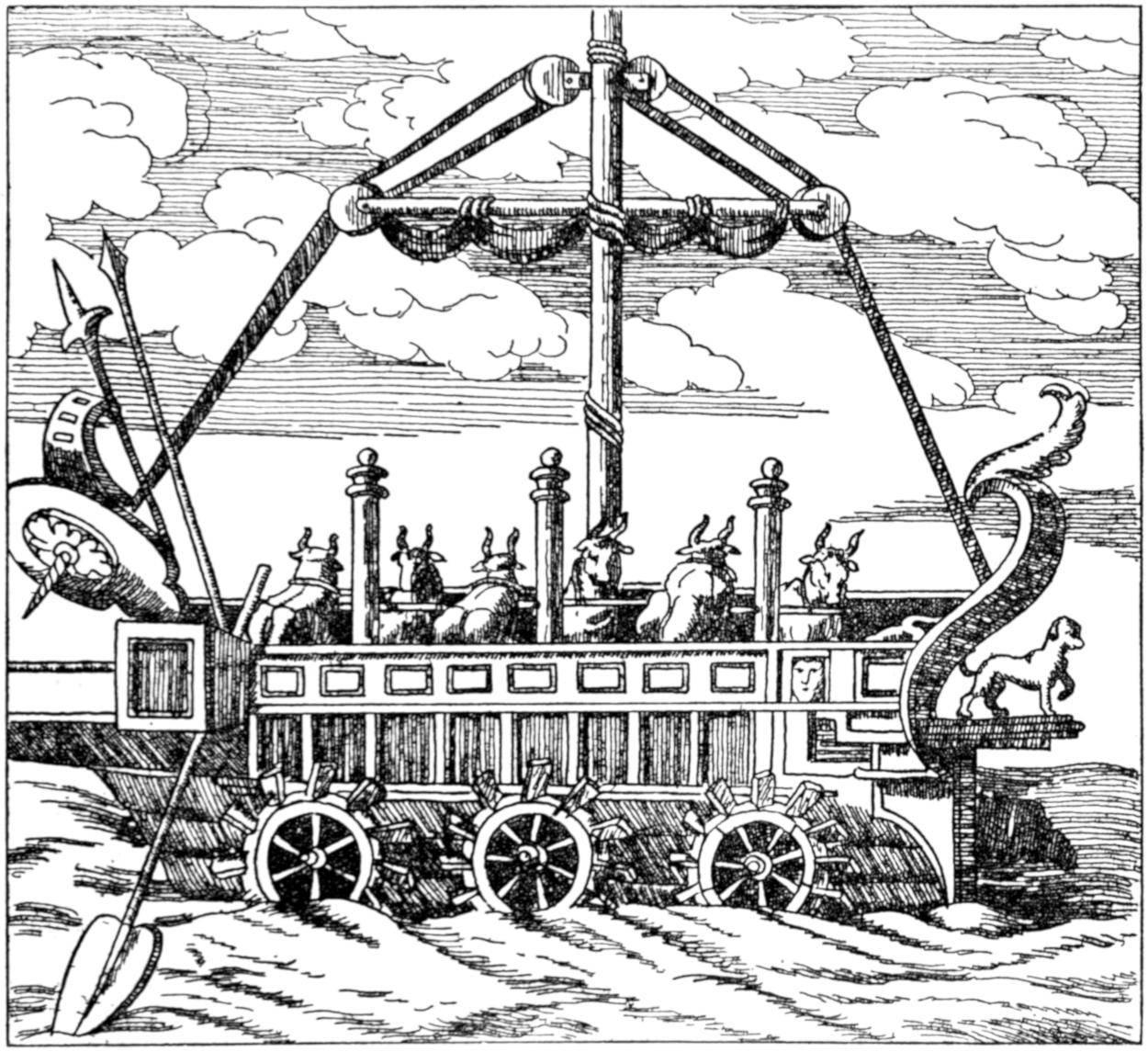

In the Far East also, wheel-boats were in use long before steamdriven paddle-wheels were invented. The Chinese certainly used them. In a paper read at the Society of Arts in April 1858, Mr. John McGregor, a barrister, who devoted considerable time to the study of early mechanical appliances, stated that an old work on China contains a sketch of a vessel moved by four paddle-wheels, and used perhaps in the seventh century. In certain “Memoires” of the Jesuit Fathers at Peking, published at Paris in 1782, there appears this quaint description of a “barque à roues”: “This vessel is 42 feet in length and 13 feet in width. The wheels are fixed in an empty space about a foot high situate underneath the strip between the stout planks a b. From the axle or centre of the wheels any number of spokes radiate which act like teeth for the wheels. They enter the water to the depth of a foot. A number of men make the wheels turn round. The length of the prow from l to m is 8 feet. The length of the body of the vessel from n to o is 27 feet, and the length of the poop 7 feet. Heads of tigers are represented on movable boards covered with leather, about 5 feet in height and 2 feet wide. These boards shelter from the enemy the soldiers who are behind them. They are removed when the crew decide on boarding the enemy’s vessel.” The good Fathers in their “Memoires” add a recommendation to experts in Paris to study the principle with a view to its adoption in French vessels, and they point out that even if the extra speed attained were ever so slight it might be sufficient to bring a vessel out of a dangerous situation. It may well be doubted, however, whether the shipping experts in Paris at that date profited by this humanitarian suggestion. Be this as it may, the passage proves that the propulsion of vessels by revolving wheels was not a western idea only.

“B����� � R����,” P�������� C������

P�����-����.

Panciroli, writing in the sixteenth century, describes an extraordinary boat of which he had seen a picture. His book is not illustrated; but we find a representation of a liburna, or galley, which exactly corresponds to Panciroli’s description,[3] in Morisotus’ (Claude Barthélemy Morisot) “Orbis Maritimi ... generalis Historia,” published in 1643.

[3] “Vidi etiam effigiem Navium quarundam, quas Liburnas dicunt; quæ ab utroque latere extrinsecus tres habebant rotas, aquam attingentes: quarum quælibet octo constabat radiis, manus palmo e rota prominentibus: intrinsecus vero sex boves machinam quandam circumagendo rotas illas incitabant: et radii aquam retrorsum pellentes, Liburnam tanto impetu ad cursum propellebant, ut nulla triremis ei posset resistere ” G���� P��������: Rerum memorabilium, libri ii Ambergæ, 1599

The vessel, an Illyrian galley, had six wheels propelled by as many oxen. The curious picture suggests an unwieldy, top-heavy concern

which could only be of use in still water, and would probably be safest in shallow water, so that if anything happened the oxen and men could walk ashore without trouble. The cattle apparently occupy most of the space, an immense bird’s head with a hooked nose juts out in front immediately above the water-line; this is of course the ram, above which is a platform upon which a dog stands as the vessel’s figure-head.

It is unnecessary to go in detail into all the schemes devised by inventors and visionaries for propelling vessels by mechanical means. Several of them from time to time suggested placing wheels on the outside of the boat, and “turning the wheeles by some provision so that the wheeles make the boat goe,” to quote William Bourne’s proposition of 1578, but the “some provision” constituted a problem which he and many others found too much for them. David Ramsay in 1618 took out a patent “to make boats for carriages running upon water as swift in calms and more safe in storms than boats full sailed in great winds,” and twelve years later another patent is recorded to his credit for making ships and barges go against the tide. The optimism of these and other mechanical pioneers was wonderful; indeed, had their inventive genius only equalled their imagination, some of the difficulties which until comparatively recently baffled naval engineers and marine architects would have been long since overcome.

“L������” �� G�����, ������ �� O���.

From Morisotus.

The webbed feet of water-birds suggested to many a form in which mechanical propulsion could be applied. This was only natural, as early shipbuilders took as their models the birds which they saw floating before them. In 1759 a Swiss pastor named Genevois published at Geneva a proposal to use an oar fitted with a foot which should expand when used for propelling a boat and contract when being moved forward through the water for another stroke. Genevois visited London in 1760 to lay his proposal before the Government. His propellers were to be worked by springs which in turn were to be

compressed by a kind of cannon with a piston. A pamphlet which he issued at the time of his application to the Government contains the interesting statement that he had been informed that a Scotchman had propounded a scheme thirty years earlier for propelling vessels forward by the recoil from the firing of cannon over the stern. The gunpowder of the period made up in smoke what it lacked in power; hence, although the vessels of his day were not large, the ingenious Scot “found, by the experiments made for that purpose, that thirty barrels of Gun-powder had scarce forwarded the ship the space of ten Miles”; and it is not surprising that this means of mechanical propulsion shared the fate of all of its predecessors.[4]

[4] “Some New Inquiries tending to the Improvement of Navigation,” by J. A. Genevois, 1760.

Many other extravagant schemes might be quoted. Edward Ford in 1646 was quite modest in his patent to “bring little ships, barges, and vessels in and out of any havens without or against any small wind or tide,” to which he cautiously added the qualification “if the seas be not rough.” With the exception, however, of a few sporting proposals of which the Scotch Gunpowder Plot is a type, no advance in solving the problem of producing the power for propulsion was made for centuries. The burden of physical exertion had been shifted from men to animals, but that was all; and yet in every age during the last two thousand years there seem to have been many people who were acquainted with the expansive power of steam, a fact which makes this slow development the more remarkable.

The first person to observe the properties of steam, or at any rate the first to record his observations, was Hero of Alexandria in 120 �.�., but though he advanced from theory to practice, his æolipile does not seem to have answered any useful purpose. This machine consisted of a hollow glass ball supplied with steam at its axis. The steam escaped by means of a series of hollow tubes, placed at right angles and projecting from the globe at a circle on its circumference equidistant from the two poles, the tubes being closed at the ends and provided with orifices at the sides near the ends. Nothing came of his invention, so far as is known, and the æolipile remained an interesting toy and nothing else—a toy, however, which has the

honour of being the first mechanical contrivance in which the expansive power of steam was used. After this, for many centuries, no attempt was made to use this great natural agency for the purpose of producing what Bacon called “fruits” for mankind. Unscrupulous priests worked “miracles” by this means for the edification of their flocks, and doubtless revived thereby many whose faith had become lukewarm. It never seems to have occurred to them that a far more direct means of moving mountains was already under their control.

At last in 1629 the use of steam as a means of producing power was suggested by Giovanni Branca of Loretto, who, apparently adopting a simplified form of Hero’s device, planned so that a jet of steam blew against a series of vanes arranged on the rim of a wheel.

In the seventeenth century also, that eccentric genius the second Marquis of Worcester published his “Century of Inventions.” In this he suggested a number of mechanical contrivances, some of which contained the fundamental ideas of later inventions, the most notable being that of a steam-engine with a piston and lever; but he does not seem to have designed any vessel which would justify the claim sometimes made on his behalf that he was the inventor of the steamboat.[5]

[5] Partington’s edition of the “Century of Inventions ”

About the same time, Sir S. Morland, another experimenter, estimated the expansive force of water at 2000 times, in which he was not far from the truth.

England, however, was not the only country to produce inventors. One Blasco de Garay, who flourished a hundred years before the Marquis of Worcester, is declared by his champions to have been the first to solve the problem of propelling a vessel by steam-power. But investigations as to the accuracy of the story tend to the belief that he did nothing of the kind, and that the beautifully circumstantial account of his experiment does greater credit to the imagination of the narrator than to his regard for accuracy.[6] De Garay’s experiment was made at Barcelona in the year 1543 in the presence of representatives of the Emperor Charles V. Ravago, the Treasurer, reported to the Emperor that the vessel would go two leagues in

three hours, but that the machine was complex and expensive, and that the cauldron in which the steam was generated might burst. This is exactly the report which a cautious financier, presumably not an expert in mechanics, might be expected to make. Other reports were more favourable to the project, the commissioners appointed for the purpose ascribing to the vessel a speed of a league an hour. What has been established beyond question, however, is that De Garay made the experiment with a boat fitted with paddle-wheels, but that the wheels were turned by men and not by steam.

[6] Mr. John McGregor reported to the Society of Arts that the claim that De Garay used a steam-engine is unfounded, human power being used.

Salomon de Caus, a native of Normandy, is sometimes claimed by French writers to have first thought of using steam as a motive power in 1615, but his invention does not seem to have fructified. Half a century later the unlucky Doctor Denis Papin, a native of Blois, entered the field of invention. He came to this country from France in 1675, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1681, and in 1690 described a steam cylinder fitted with a piston which descended by atmospheric pressure when the steam below it was condensed. He suggested that one of the uses to which his engine might be put was the revolution of paddle-wheels fitted to a ship, several cylinders being applied which worked alternately with the rackwork he designed. He may have been led to this by witnessing in 1681 the experiments on the Thames with a boat designed by Rupert, the Prince Palatine, with revolving fans, which easily left behind a boat manned by a number of oarsmen. It has been claimed for Papin that he was the inventor of the safety-valve, but this is disputed.[7] Prior, however, to his atmospheric engine he brought out in 1685 a machine for raising or pumping water, but the Royal Society treated it with contempt and referred to it as a “mere trick.” Neither of his machines received the recognition which historians have since decided was their due, and he went back disheartened to France, whence he was driven by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes to Marburg. He reappeared in England in 1707 and announced a project for moving ships by means of wheels and

steam. Unfortunately for him, Thomas Savery, born in 1658, had already been at work on the problem, and had brought out his fireengine, which among other things he thought might be used to propel ships. His machine lacked power, and was replaced by one made after the design of his partner Newcomen. Papin was also associated with Newcomen and Savery at one time. Savery says of his own machine that he would refer the question of its suitability for shipping to those more competent than himself to judge. Papin appealed to the Naval Department to consider his invention, but the Government of the day, after the manner of Governments when face to face with a new project, thought it useless, and made severe remarks on his presumption in continuing to invent for them. He exhibited his invention on the Thames, but no one took any interest in it. Thoroughly disheartened by the failures which attended all his efforts, Papin went to Germany, and is stated to have there built a steamer which was actually tried on the Fulda or the Weser, but the local watermen, fearing the rivalry of the new machine, smashed it, and that is the last which history has to record of Papin as a pioneer of steamboats. It is asserted that this boat was built for him by Newcomen and Savery in this country. As an experimenter he did valuable work, for he seems to have been the first to have grasped the importance of the vacuum under the piston.[8]

[7] Hy Frith’s “Triumphs of Steam ”

[8] Lindsay’s “History of Merchant Shipping.”

In 1730 another remarkable proposition was made for marine propulsion. Doctor John Allen thought it possible to move a boat by pumping in water at the bows and pumping it out again at the stern, this scheme being probably the earliest attempt to secure motion by what has since become known as the jet-propeller system. Like almost all other inventions of his period it was crude in its details and does not seem to have been put to any practical use.

The next inventor who turned his attention to the question was Jonathan Hulls, for whom it has been claimed, with some show of justification, that he was the actual inventor of the steamboat. That he did invent a steamboat is beyond question, but whether his vessel was ever built, and if so whether it attained any measure of success,

are points upon which historical evidence is not conclusive. But if it was constructed, and there is strong circumstantial evidence in support of this contention, then to the West of England, which has contributed so largely to the maritime glory of Britain, must be ascribed also the honour of being the birthplace of one of the two inventions which have done more than anything else to aid in the spread of civilisation and commerce. Hulls was born at Aston Magna in 1699. By occupation he was a clock repairer, a precarious trade at best. The difficulties he had to encounter through lack of means were very great, but he persevered, and a patron at last appeared in the person of a Mr. Freeman, of Batsford Park, near Chipping Campden, who supplied him with about £160 to develop and patent his invention. This enabled Hulls to proceed to London, and he petitioned Queen Caroline, as Guardian of the Realm in the absence of her Consort George II. at Hanover, for Letters Patent for the invention, which was accordingly granted to him December 21, 1736, provided he enrolled in Chancery within the following three months a specification describing his invention.[9] The patent read as follows:

“Whereas our Trusty and Well Beloved Jonathan Hulls hath by his petition humbly represented unto Our most dearly beloved Consort the Queen.... That he hath with much Labour and Study, and at Great Expense Invented and Formed a machine for carrying Ships and Vessels out of or into any Harbour, &c., which the Petitioner apprehends may be of great service to our Royal Navy and Merchant Ships, and to Boats and other Vessels, of which Machine the Petitioner hath made oath that he is the sole inventor, as by affidavit to his said petition annexed.

“Know ye therefore that we of our special grace, have given and granted to the said Jonathan Hulls our special license, full power, sole privilege and authority during the term of fourteen years, and he shall lawfully make use of the same for carrying ships and other vessels out to sea, or into any harbour or river.

“In witness whereof we have caused these our letters to be made patent.

“(Witness) C�������, “Queen of Great Britain.

“Given by right of Privy Seal at Westminster this 21st day of December 1736.”[10]

[9] Mr J H Hulls’ lecture at the Institute of Marine Engineers on “The Introduction of Steam Navigation,” February 26, 1906 [10] From copy of patent in possession of Mr. J. H. Hulls.

Mr. P. C. Rushen, in referring to the experiment, writes:

“About this time it may be presumed that Jonathan set about constructing a vessel in accordance with his plans, and for this purpose he had the help of the Eagle Foundry at Birmingham, to which he forwarded rough model plans and sketches to aid in founding and forging the various parts. Until quite recent years these relics were existent, but on the sale and demolition of the foundry they seem to have been destroyed.

“The new vessel was tried on the Avon, but tradition says it was a failure, by reason of the inventor not providing the proper means to communicate the power to the paddle. That the experiment was a failure seems evident from the fact that nothing more was heard of the boat, but for the given reason is very improbable, because the very ingenious means the inventor describes, although perhaps not quite practical on a large scale, are not palpably unworkable for a small experimental boat. Even if these means were a failure, it would be ridiculous to suppose that a clever mechanic such as Hulls shows himself to be in his pamphlet would be at a loss for some expedient.

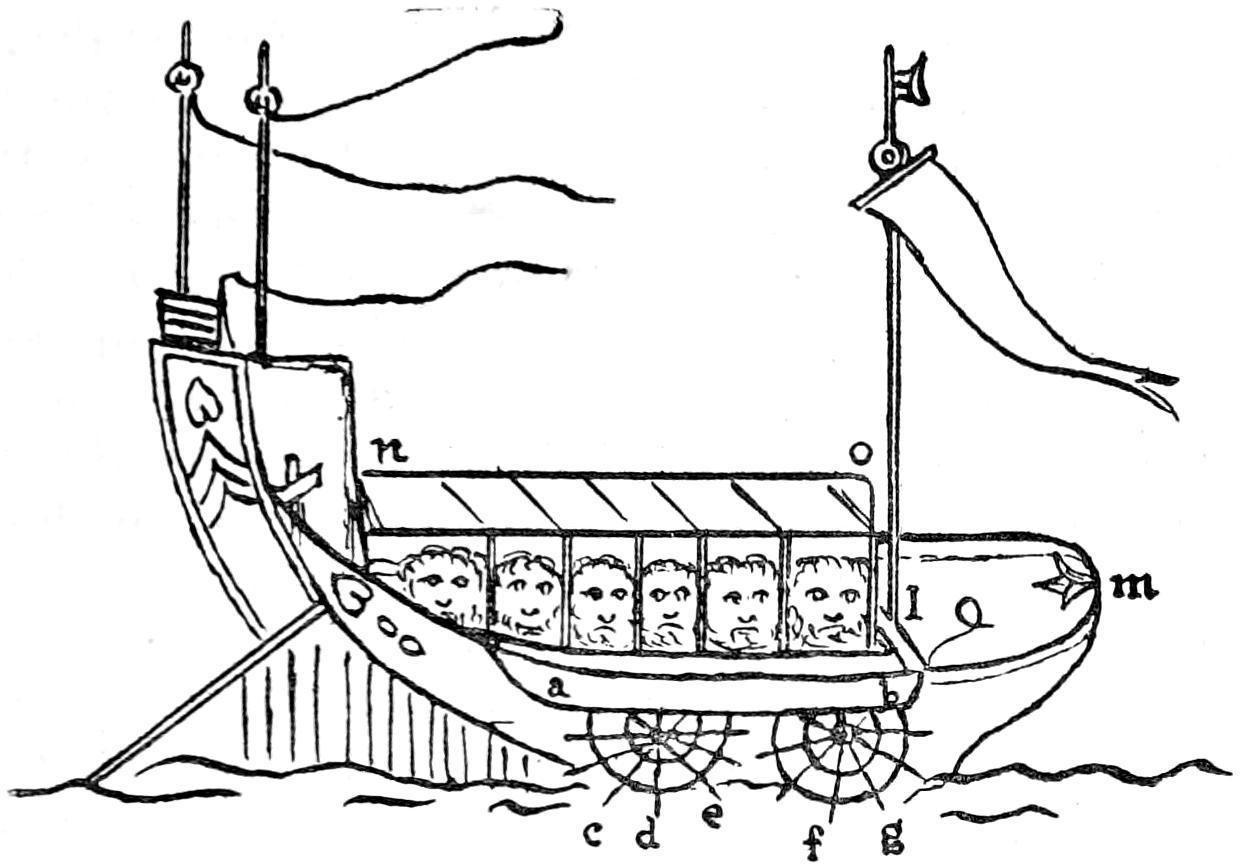

J������� H����’ P����� S������, 1737.

“The more probable reason of Hulls’ failure was the want of financial support, that previously accorded him being perhaps withdrawn on the first hitch in the experiments, or for some other reason, this so disheartening him that he relinquished the idea. While Hulls had been at work on his project, he had worn a brown paper cap, as usual with mechanics at that time, and this fact was taken advantage of in a scathing doggerel, which was circulated upon his failure, and which ran:

“Jonathan Hull With his paper skull; Tried to make a Machine

To go against wind and tide, But he, like an ass, Couldn’t bring it to pass So at last was ashamed to be seen.”[11]

[11] P. C. Rushen’s “History and Antiquities of Chipping Campden in the County of Gloucester,” 1899.

The engine which Hulls used was an adaptation of Newcomen’s. He published a lengthy description of his boat, in which he states that, in his opinion, it would not be practicable to place his machine on anything but a tow-boat, as it would take up too much room to allow of other goods being carried on the same vessel, and it could

“not be used in a storm, or when the waves are very raging.” Hulls died in London destitute, and the world inherited his ideas. Steam tow-boats are now found all over the world, and the despised sternwheeler of his day was the forerunner of the great stern-wheelers of the Mississippi.

Another person who took up the subject seriously was a Frenchman, Jouffroy d’Abbans, better known perhaps as Claude François Dorothée, Marquis de Jouffroy. His invention was known as the Pyroscaphe. It was claimed for him by the Marquis de BaussetRoquefort that “he was the first who carried out in practice a scheme for navigation by steam, his successful experiments on the Saône at Lyons in 1783 being attested by official documents, and by the evidence of thousands of spectators. The glory of the invention of the means of using steam-power in navigation belongs therefore to France, as is clearly shown by the archives of the town of Lyons.”

The Marquis de Jouffroy was born at Roche-sur-Rognon in 1751. A duel fought while he was page to the Dauphin caused his exile to Provence, where he studied the methods by which the ancient rowing galleys were propelled. He returned to Paris in 1775 and conceived the idea of inventing some form of steamboat while looking at the Chaillot fire-pump which Périer[12] had erected a short time previously. He communicated his project to Périer, who made some fruitless experiments and declared the idea impossible. Jouffroy, however, persevered, and in 1776 had constructed a machine which he adapted for use on a boat. “His first pyroscaphe was 13 m. long, and 1 m. 95 c. wide. The ‘swimming’ apparatus consisted of rods 2 m. 66 c. in length suspended on either side well forward and carrying at their extremity frames fitted with hinged flaps with a dip of 50 c. The frames were capable of describing an arc of 2 m. 66 c. (8 feet) radius and of 1 m. (3 feet) in length, and were drawn forward at the end of the stroke by a counterweight. A single-acting engine by Watt, installed in the middle of the boat, set in action these hinged flaps. The construction of this apparatus in a locality where it was impossible to obtain a cast and bored cylinder was a work of genius, courage, and patience. Despite its imperfections it was superior to anything attempted up to that time in navigation. The boat worked on the Doubs at Baume-les-Dames between Montbéliard

and Besançon during the months of June and July.” This system, since called the “Palmipède,” imitated the movements of aquatic birds, and was the only one that could be applied to the steamengine as then known. It was, however, useless for moving large masses or for working against the current. “Jouffroy saw the defects caused by the fact that the rapidity of the boat’s motion prevented the hinged flaps from reopening after the forward stroke, especially when the pyroscaphe was moving upstream or against the tide. Hence the engine only acted at intervals instead of keeping up a sustained movement. But Jouffroy substituted paddle-wheels for the hinged flaps (volets à charnière) and devised a new machine in which the action of the steam was made continuous by means of two bronze cylinders, the top placed lengthwise with the run of the ship, making with the horizon an angle of about 50 degrees. The bottoms of the cylinders were encased in a metal box containing a sliding tile which opened and shut, alternately giving a passage to the steam and the intake of water in each cylinder.

[12] The name is spelt “Perrier” by some writers

T�� M������ �� J�������’� S��������. 1783.

“By July 1, 1783, Jouffroy had constructed a second boat which was launched at Lyons. Its dimensions were considerable, the length attaining 46 m. and the breadth 4 m. 50 c. The wheels were 4 m.

diameter, the paddles 1 m. 95 c., dipping 65 c. The draught of water of the vessel was 95 c. The total weight was 327 milliers, of which 27 were for the vessel and 300 for the freight. This enormous vessel voyaged against the tide of the Saône from Lyons to L’île Barbe in the presence of the Commission de Savants and thousands of spectators, as officially recorded in the archives of the Municipality of Lyons.” Arago says this vessel continued to navigate the Saône for sixteen months.[13]

[13] Paper read by the Marquis de Bausset-Roquefort before the Lyons Literary Society in 1864, and preserved at the Mazarin Library (Academy of Sciences), Paris

Jouffroy now thought of starting a company to run boats on the new system, and applied to the Government for the necessary permission. The question was submitted to the Academy of Sciences, who appointed a Commission to inquire into the matter, but among the members of the Commission was the unsuccessful Périer, whose opposition resulted in the Academy concluding that the experiments at Lyons were not decisive. The Marquis had not the means to continue building steamboats and, profoundly discouraged, he abandoned the rôle of inventor He had already been subjected to much ridicule, and it was generally agreed that he must be mad to think of “making fire and water agree”; he was even nicknamed “Pump Jouffroy.” He witnessed the experiments of Fulton in France, but did not think of claiming the merit of his discovery until 1816, when he issued a publication entitled “Steamboats.” The same year he took out a patent, formed a company, and on August 20 launched a steamboat at Bercy, but the venture did not come up to the expectations of the shareholders, and this was his last effort. Jouffroy died of cholera at the Hôpital des Invalides in 1832. Arago, the historian, says that his claims to be the first inventor of the steamboat have been established, and, according to Larousse’s “Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle,” Fulton himself openly acknowledged them in the United States law courts.

CHAPTER II

AMERICAN PIONEERS IN STEAM NAVIGATION

owards the end of the eighteenth century American inventors turned their attention to the problem of navigation by steam, and to one of them, Robert Fulton, the credit of having invented the steamboat has usually been given. Livingston’s “Historical Account of the Application of Steam for the Propelling of Boats” has been accepted as an authority on the subject, but as he was Fulton’s friend and backer, and Fulton married into the Livingston family, there is reason to question the absolute accuracy of the circumstantial story told by this most eloquent special pleader, though there is some excuse for his partiality. A little investigation makes it apparent that Fulton was not the first American to design a successful steamboat, nor even the first to make the running of steamboats a satisfactory speculation.

In 1909 a Mr. John Moray of West Virginia presented a petition to Congress in which he asked for the official recognition of James Rumsay as the inventor of the steamboat, and the perpetuation of his memory by the placing of an appropriate bust in the Statuary Hall at the Capitol. According to the petition “The deed-books of Berkeley County, Va., for the year 1782 record the fact that James Rumsay, a native of Maryland, who was a millwright and Revolutionary soldier, purchased a farm, and soon after a pond, for experimental purposes in the line of his calling. On that pond, as the results of many experiments in steam and hydrostatics by James Rumsay, the wonderful discovery of the principle of steam navigation took place. Thoroughly satisfied by continuous experiments that the newly discovered principle would become of immense value in the world, Rumsay contracted with his brother-in-law, Joseph Barnes, for the building of a boat for steam purposes at St. John’s Run, on the Potomac River. The resulting steamboat was publicly exhibited at