Women Who Fly: Goddesses, Witches, Mystics, and Other

Airborne Females Serinity Young

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/women-who-fly-goddesses-witches-mystics-and-other -airborne-females-serinity-young/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Biota Grow 2C gather 2C cook Loucas

https://textbookfull.com/product/biota-grow-2c-gather-2c-cookloucas/

Fly girls: the daring American women pilots who helped win WWII First Edition Pearson

https://textbookfull.com/product/fly-girls-the-daring-americanwomen-pilots-who-helped-win-wwii-first-edition-pearson/

Females in the Frame: Women, Art, and Crime Penelope Jackson

https://textbookfull.com/product/females-in-the-frame-women-artand-crime-penelope-jackson/

Women in the Kurdish Movement : Mothers, Comrades, Goddesses Handan Ça■layan

https://textbookfull.com/product/women-in-the-kurdish-movementmothers-comrades-goddesses-handan-caglayan/

Rad women worldwide artists and athletes pirates and punks and other revolutionaries who shaped history

First Edition Klein Stahl

https://textbookfull.com/product/rad-women-worldwide-artists-andathletes-pirates-and-punks-and-other-revolutionaries-who-shapedhistory-first-edition-klein-stahl/

A History of Women in Medicine Cunning Women Physicians Witches Sinead Spearing

https://textbookfull.com/product/a-history-of-women-in-medicinecunning-women-physicians-witches-sinead-spearing/

Witches The Transformative Power of Women Working Together Sam George-Allen

https://textbookfull.com/product/witches-the-transformativepower-of-women-working-together-sam-george-allen/

Navigating Life with Migraine and Other Headaches

William B Young

https://textbookfull.com/product/navigating-life-with-migraineand-other-headaches-william-b-young/

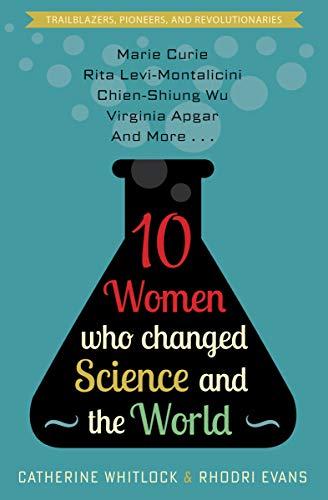

10 Women Who Changed Science and the World Catherine Whitlock

https://textbookfull.com/product/10-women-who-changed-scienceand-the-world-catherine-whitlock/

Women Who Fly

Women Who Fly

Goddesses, Witches, Mystics, and o ther a irborne Fe M ales

Serinity Young

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Young, Serinity, author.

Title: Women who fly : goddesses, witches, mystics, and other airborne females / Serenity Young.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017011532 (print) | LCCN 2017052609 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190659691 (updf) | ISBN 9780190659707 (epub) | ISBN 9780190659714 (oso) | ISBN 9780195307887 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Goddesses. | Wiccans. | Women mystics. | Women. | Supernatural.

Classification: LCC BL473.5 (ebook) | LCC BL473.5 .Y685 2018 (print) | DDC 200.82—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011532

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Flying is woman’s gesture—flying in language and making it fly.

Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa”

Contents

Acknowledgments xi

Introduction 1

Female Flight 2

Heroines, Freedom, and Captivity 4

Transcendence and Immanence 7

Shape- Shifting 8

1. Earth, Sky, Women, and Immortality 11

Earth, Sky, and Birds 11

Magical Flight, Ascension, and Assumption 15

Dreams, Women, and Flying 17

Humans, Divinities, and Birds 20

Apotheosis 20

Birds 22

Bird Goddesses 24

PART I | Supernatural Women

2. Winged Goddesses of Sexuality, Death, and Immortality 29

Isis 29

Women, Death, Sexuality, and Immortality 32

The Ancient Near East 36

Ancient Greece 41

Athena and the Monstrous-Feminine 42

Aphrodite 49

Nike 50

3. The Fall of the Valkyries 53

Brunhilde in the Volsungs Saga 54

Images and Meanings 59

Brunhilde in the Nibelungenlied 64

Wagner’s Brunhilde 68

4. Swan Maidens: Captivity and Sexuality 73

Urvaśī 73

Images and Meanings 75

Northern European Tales 79

Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake 81

Asian Swan Maidens 83

Feather Robes and Dance 85

Two Middle Eastern Tales 87

Hasan of Basra 87

Janshah 89

5. Angels and Fairies: Male Flight and Contrary Females 95

Angels and Demons 96

Fairies 104

Morgan le Fay 105

Fairy Brides 110

Asian Fairies 112

6. Apsarās: Enabling Male Immortality, Part 1 117

In Hinduism 118

Relations with Heroes 119

Seducing Ascetics 121

Kings, Devadāsīs, and Fertility 125

In Buddhism 127

Seductresses 128

The Saundarānanda 131

7. Yoginīs and Ḍākinīs: Enabling Male Immortality, Part 2 133

Tantra 133

Yoginīs 134

Yoginī Temples 135

Practices and Stories 138

Sexual Yoga 139

Taming 142

Ḍ

ākinīs 143

Subduing 144

Tibetan Practitioners 147

Part II | Human Women

8. Witches and Succubi: Male Sexual Fantasies 153

Medea 154

Ancient Witches and Sexuality 155

Circe 155

The Witch of Endor 157

Succubi and Incubi 158

Witches in Christian Europe 160

The Witches’ Sabbath 162

Women and the Demonic 162

Flying 166

9. Women Shamans: Fluctuations in Female Spiritual Power 172

The Nišan Shaman 173

Becoming a Shaman 178

Magical Flight, Ritual Dress, and Spirit Animals 179

Gender 182

Transvestism and Sex Change 184

Sexuality 186

10. Flying Mystics, or the Exceptional Woman, Part I 189

St. Christina the Astonishing 190

Flight and Sanctity 193

St. Irene of Chrysobalanton 194

St. Elisabeth of Schönau 196

Female and Male Mystics 201

Hadewijch of Brabant 205

11. Flying Mystics, or the Exceptional Woman, Part II 208

Islam 208

Rābi’ah al-‘Adawiyya 209

Other Aerial Sufī Women 211

Daoism 213

Sun Bu’er 214

Daoist Beliefs and Practices 216

Buddhism 222

Human Ḍākinīs 223

Machig Lapdron and Chod Practice 226

12. The Aviatrix: Nationalism, Women, and Heroism 228

Wonder Woman 228

Amelia Earhart 233

Death and the Heroine 235

Hanna Reitsch 237

Women, Heroism, and Militarism 243

Conclusion 249

The Exceptional Woman 251

Women and War 253

Notes 255

Works Consulted 313

Index 347

Acknowledgments

I initially explored some of the aerial women of this book, such as swan maidens and apsarās, through articles I wrote for An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, compiled at the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS). A few years later, I returned to ARAS to research images for this book, and I am very grateful to Ami Ronenberg for granting me access to this archive and for her assistance and insights.

In the 1980s I worked in the Oral History Department of Columbia University as a transcriber of oral histories, among which were those of the first women accepted into the United States Air Force Academy; there I later read the oral history of Hanna Reitsch. Clearly, life has presented me with opportunities, the full import of which I did not realize until this book began to take shape.

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), where I am a research associate, provided a stimulating environment, a formidable collection of artifacts, and access to experts in many of the world’s cultural areas. Most notably, Laurel Kendall, Stanley Freed, and Robert Carneiro always provided enthusiasm and very practical advice, while the librarians at AMNH were more than helpful. Barry Landau saw me through many a computer glitch. Additionally, Laurel Kendall allowed me to audit her class, “The Korean Shaman Lens: Anthropology, Medicine, Popular Religion, and Performance,” at Columbia University, which proved to be of inestimable help in sharpening my perspective on the vast geographical and

Acknowledgments

historical range of all matters shamanic. Jonathan White was an enthusiastic and creative intern on this project during the summer of 2008, while the indefatigable Amanda Audette helped to move this book forward as an intern in the summer of 2014. The inestimable Linden Kawamura provided much-needed assistance with the bibliography and permissions for images, as well as with line editing in the fall of 2016 and spring of 2017. Her commitment to this project has been a crucial support. With skill and humor she corrected errors and updated references.

I am grateful to the Asian Arts Council for a grant to seek out aspsarās, ḍākinīs, and yoginīs in their native habitats in South and Southeast Asia. In India, Mary Storm, as ever, offered extremely helpful insights about South Asian images and archaeological sites along with warm hospitality, while Arundhati Banerjee of the Archaeological Survey of India once again provided helpful contacts throughout India and was unsparingly generous in sharing her knowledge of sites and artifacts. I would also like to express my appreciation to the Schoff Fund at the University Seminars at Columbia University for their help with publication. The ideas presented here have benefited from discussions in the University Seminar on Studies in South Asia.

When I presented parts of chapters 5 and 10 to of the Friends of the Saints of New York City, the members provided stimulating discussions about flying, bilocation, transvection, ascension, assumption, and so on, as well as pertinent examples of saintly and not so saintly aerial women. Sections of chapters 6 and 7 were given as lectures at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, where I was a research scholar in the History of Science and in Archaeology, and at the Columbia University Seminar on Buddhist Studies. The many pertinent comments and suggestions I received on these occasions were most appreciated.

Christian Luczanits was generous in sharing ideas about and rare images of aerial women, while David Rosenberg, Tashi Chodron, and other staff members at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art were always welcoming and ready to discuss details of their exhibitions. Claudine Cohen provided excellent advice on images and walked me through prehistory, while Marian Kaplan was helpful in my initial work on Hanna Reitsch. June- Ann Greeley and Francis Tiso were particularly helpful with regard to flying mystics and discussions about the Holy Spirit as female. Claude Conyers adjusted my alignment on the topic of ballet and more generally, with his keen editorial eye, discerned the overall shape of the book at a time I was so weighted down with details that I forgot to keep looking up. James Waller provided essential editorial help that made this not only a more readable but a better book. My Oxford University Press editor Cynthia Read has the patience of a saint mixed with the requisite sense of humor that kept me on track and got me to finish.

Research librarians at both the main branch of the New York Public Library and its Performing Arts Library, as well as at Columbia University, continually amazed me with their helpfulness and erudition. Even in this age of the Internet, where would we scholars be without them? I must also thank the librarians at Queens College, the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Goethe Institute in New York City. Nonetheless, any errors are mine alone. The enthusiasm of my colleagues in the Department of Classical, Middle Eastern and Asian Languages and Cultures at Queens College was a great support, as was their willingness to discuss sections of the text. I am blessed with additional friends who have a deep interest in my work and offered support both material and spiritual. This book could not have been written without them: Tim Harwood, Ralph Martin, Tina Eisenbeis, Lozang Jamspal, Gopal Sukhu, Hanna Kim, Karen Pechilis, Joel Bordeaux, Carol Anderson, Christina Stern, Andrew Martin, Marya Ursin, and Dan Potter.

Women Who Fly

Introduction

Perhaps the world’s most famous image of a winged female is the statue of the Greek goddess of victory, Nike, also known as the Victory of Samothrace (Figure 0.1)—a centerpiece of the Louvre Museum, where it is magnificently displayed in all its glory at the top of Daru stairway, formerly the museum’s main entrance.1 It was sculpted around 220–185 bce to commemorate victory in an unknown sea battle, and Nike is depicted at the moment of landing on the deck, her body surging with power up and through her arched and extended wings. It is one of the finest pieces of the Hellenistic Period. (More will be said about her in chapter 1.)

My adult journey with winged women began with this statue when I first entered the Louvre through its earlier entrance. Standing over eighteen feet (5.57 m) high from its base to the tip of its wings and carved out of exquisite Parian and Rhodian marble, it froze me in place, stunned with awe. Day after day I returned to sit and stare—in the early spring of 1970 there were few other visitors to disturb my contemplations—having no idea what to make of its transcendental power and beauty. As John Berger has written: “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled . . . . [T]he knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight.”2 After I returned home to the United States, the experience slowly faded from my mind, until now, these many years later, when Nike is once again paramount in my thoughts— she and, as I now know, her many sisters from around the world.

Figure 0.1 Victory of Samothrace (Nike), second century bce. Marble. Photo: Michel Urtado/ Tony Querrec/Benoît Touchard. Musée du Louvre.

© Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Utrado, Querrec, Touchard/Art Resource, NY.

Women Who Fly: Goddesses, Witches, Mystics, and Other Airborne Females is a typology of sky-going females, an intriguing and unstudied area of the world’s myths, religions, and iconography. It is a broad topic. My goal has been not to restrict this theme (or its imagery) nor to force it into the confines of any one discipline or cultural perspective, but rather to celebrate its diversity while highlighting commonalities and delineating the religious and social contexts in which it developed. Paraphrasing Christopher Hill, the paradigm itself makes it worthwhile to compare such females in the light of differing national circumstances.3 Aerial women are surprisingly central to understanding similarities between various religious imaginations through which they carved trajectories over time.

Female Flight

One of the earliest stories of female flight comes from ancient China. The legendary Emperor Yao had two daughters, Nü Ying and O Huang, both of whom knew

how to fly. At their father’s request, they instructed the future emperor Shun (traditionally 2258–2208 bce) in the art of flying, which he used not only to escape an immediate danger but also as an expression of his divine nature and therefore of his right to rule. His ability to fly seems to have been connected to wearing a bird suit, which is very suggestive of the feather suits that were worn by later Daoist mystics who were called “feather clothed” (see chapter 11 for further discussion of this) and the feather suits of swan maidens and some Asian fairies (chapters 4 and 5), as well as the bird suits worn by northeast Asian shamans (chapter 9). After many adventures, Shun married the sisters and became emperor.4 In this early story, flying women are sexual beings who bestow blessings, such as sovereignty and supernatural gifts, on male heroes—a theme that is repeated in many different times and places.

As with Nü Ying and O Huang, many of these airborne women marry mortal men, transforming them into something more than they had been, but they do not always live happily ever after. Aerial women often shape- shift between human and avian forms, as with swan maidens; while in human form, however, they are vulnerable to captivity. Once captured, they sometimes live with a man for years, and even bear his children, before finally escaping back into their bird form and fleeing. At other times an aerial woman willingly accepts a man but sets a condition or taboo—one that he inevitably breaks. She then flies away. This suggests the paradoxical nature of these creaturely and sexual beings; on the one hand, they are creatively involved with humans through their reproductive powers, while on the other they reject the terrestrial realm of human beings. They are essentially birdlike, briefly nesting on the earth, but most at home in the sky. Some can confer the blessings of fertility and immortality or snatch life away. One needs to be very careful in dealing with them.

Quite often aerial females are dancers (goddesses, swan maidens, fairies, apsarās, and ḍākinīs), while some women attempt to transform themselves through dance into birdlike creatures (chapters 4 and 9), bringing the aerial to the terrestrial while intimating the human capacity to bridge the two. Then there are dance rituals (of shamans, mystics, and witches) that lead to magical flight, 5 a term historians of religion have coined to indicate the use of magical or religious means to achieve flight during which the soul or spirit flies while the body mostly remains on the ground.

Flying females from a wide variety of cultures are linked to sexuality, death and rebirth, or immortality. In different places and historical periods there were remarkably similar discourses about the unpredictable powers of aerial women, who could be generous or withholding, empowering or destructive. Because of their uncertain nature, the question arose as to how they could be controlled: whether

by supplication or coercion. Over time, they flew through a universe of everincreasing constraint in which similar means were used to capture and domesticate them, to turn them into handmaidens of male desire and ambition.

Heroines, Freedom, and Captivity

Supernatural women who bridge the division of earth and sky or who simply soar through space present an intense image of freedom and transcendence.6 Yet while flight can be seen as untrammeled soaring, it can also represent fleeing from danger and/or captivity, as in tales about captured swan maidens and fairy wives. This is not to deny that several kinds of supernatural women—Valkyries, apsarās, yoginīs, and ḍākinīs, (chapters 3, 6, and 7)— were in the service of men, while witches were believed to fly in order to meet with and serve their horned god, or Satan (chapter 8). Even Wonder Woman is enraptured by her elusive lover and fellow aviator, Steve Trevor (chapter 12).

Sigmund Freud theorized that flying dreams express a subliminal desire for sexual power and that the feelings accompanying such an experience are repressed aspects of sexual arousal. Yet the stories in this volume tell us that, for many aerial females (such as swan maidens, fairies, and Brunhilde), having sex can mean the loss of flight, the loss of power, as sex is part of their captivity and domestication. In contradistinction, some aerial females (such as goddesses, ḍākinīs, some tantric practitioners, shamans, and Asian mystics) are sexual only as their desires dictate. Flying women raise important questions about what exactly constitutes the heroic female. Traditionally in myth, folklore, and literature, the heroine is a good girl, one who knows her place in the patriarchal scheme of things and does well in the traditional female roles of passive maiden, self- sacrificing mother, or obedient and dutiful wife. In the classical tradition of ancient Greece, the main expression of female heroism is her death7 and, to a lesser degree, giving birth. The heroine’s death is decidedly female; she often dies indoors and in secrecy, not publicly, without witnesses, and by her own hand. The preferred means is that she hang herself (like Phaedra), “an act that evokes at once the adornments around a woman’s neck (an erotic part of her body), the webs of deceit she traditionally weaves, and a yoke with which she is finally tamed in death.”8 Male models of heroism break free of conventional experience to enter strange realms and return with the prize of newfound knowledge, wealth, or the won princess (as evidenced by Gilgamesh, Ulysses, Aeneas, Dante, and the heroes of sleeping beauty tales, to give just a few examples). The hero returns home renewed and enriched.9 Contrarily, women who fly want to be somewhere else to stay there; they do not want to return to

conventional experience, which they view as captivity. They require us to rethink our ideas about female waywardness.

In her study of stories about the semi-legendary King Arthur, Maureen Fries has persuasively argued for a distinction between heroines, heroes, and the counter-hero:

A heroine is recognizable by her performance of a traditionally identified, female sex-role. But any woman who, by choice, by circumstance, or even by accident, escapes definition exclusively in terms of such a traditional role is capable of heroism, as opposed to heroinism. [An example of this is when women] assume the usual male role of exploring the unknown beyond their assigned place in society; and . . . reject to various degrees the usual female role of preserving order (principally by forgoing adventure to stay at home).

The[ir] adventurous paths . . . require the males who surround them to fill subordinate, non-protagonist roles in their stories. . . . [Then there is the] counter-hero [who] possesses the hero’s superior power of action without possessing his or her adherence to the dominant culture or capability of renewing its values. While the hero proper transcends and yet respects the norms of the patriarchy, the counter-hero violates them in some way. For the male Arthurian counter-hero, such violation usually entails wrongful force; for the female, usually powers of magic. . . . [S]he is preternaturally alluring or preternaturally repelling, or sometimes both, . . . but her putative beauty does not as a rule complete the hero’s valor, as does the heroine’s. Rather, it often threatens to destroy him, because of her refusal of the usual female role.10

The female counter-hero is indifferent to patriarchal values; she harkens back to an earlier, non-patriarchal time and to non-patriarchal sources of knowledge.11 For Fries, she is personified by Morgan le Fay (discussed in chapter 5)—a flying fairy sometimes said to be King Arthur’s half- sister.

The female counter-heroine is the bad girl: the dark-haired one, not the blonde; sexual, not virginal; multidimensional, slippery, and cunning. In the chapters that follow, the reader is invited to rethink the shopworn categories of good and bad girls who vie for the affections of the hero. Instead, the stories presented here highlight the female longing for freedom, and center on women trying to escape constraints, whether they be physical captivity or patriarchal definitions of womanhood. These tales will resonate with any woman who has ever felt restrained or held back, who has experienced lack of opportunity or just not had enough air to breathe. These tales, in symbolic as well as overt ways, variously articulate the

Women Who Fly

following things: the malaise of domesticated women that Betty Friedan famously defined as the “feminine mystique”; Carl Jung’s focus on the anima (men’s internal female guide); Freud’s famous question, “What do women want?”; and modern women’s suspicion that things have gone awry between women and men.

Supernatural flying women date from prehistoric times, when people postulated the radical separation of earth and sky (chapter 1). Among humankind’s first religious acts was to create myths and rituals to bridge this separation. Some evidence for this can be seen in ancient carvings of women with birdlike heads (Figure 0.2), which reveal a fascination with females and flying, as well as a hint of the notion of transcendence. These bird- women are the foremothers of the supernatural and human airborne women who followed.

The desire to get beyond the mundane and the terrestrial to reach new heights of spiritual experience has been expressed in myths and the visual arts throughout the world. Flight from the captivity of earth’s gravity and the mental constraints of time-bound desire are the backbone of myth-making. Women and goddesses have

figured prominently in such myths, both as independent actors and as guides for men. This can be seen in the rich mythology and abundant images of the Egyptian winged goddess Isis, who resurrected her dead husband, Osiris (chapter 2), as well as in tales of swan maidens—immortal women who help mortal men transcend their brutish, impoverished state (a theme also found in fairy-bride tales). The flying Valkyries of Norse religion, like the apsarās of ancient India, carry slain heroes to heaven—a theme that also calls to mind the flying yoginīs of Tantric Hinduism and the sky- walking ḍākinīs of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, who lead heroic male saints to liberation, as well as the winged goddess Nike (and her Roman counterpart, Victory), who confers success and thus immortal fame on heroes (chapter 2). Significantly, aerial women have in various cultures acted as guides to the Land of the Dead, a theme Dante utilized in his depiction of a flying St. Lucia12 and a winged Beatrice (chapter 1),13 because women were believed to know death in ways men could not (chapter 2).

Transcendence and Immanence

The human desire to be in touch with the sky and sky-beings can be understood as a longing for transcendence, a word and an experience with many meanings. To transcend is to go beyond, to rise above limits, to exceed or surpass others or what has been done before, to be superior, and above all to be free from constraint.14 Transcendence is understood to be the opposite of immanence, and in religious thinking, these opposing terms can be used to indicate that the divine is either beyond, above, and completely other or right here, among and within us.15 This study emphasizes the oneness of immanence and transcendence in the earthly appearances of aerial/celestial females and in their ability to confer earthly (supernatural) powers or transcendence by transforming men into trans-earthly beings (immortals or liberated beings).

In many cultures the female body is depicted as personifying the human condition of mortality, mutability through aging, sensuality, desire, and earthly confinement. Ironically, “[i]n their desire for absolute transcendence and totality, men make women the repository of all bodiliness and immanence and thus efface the other [woman] as a conscious being. Masculinity in its pure form is a kind of ‘bad faith of transcendence,’ in which immanence and the body are denied and projected onto women, who become consciousnessless beings on whom men can assert their freedom.”16 In their flaunting of the earth’s gravity and ability to shape- shift, flying females therefore challenge the masculine hold on the notion of transcendence.

Shape- Shifting

Shape- shifting, or the ability to change one’s bodily form, is part of the repertoire of women who fly. There are swan maidens who can be trapped in human form if a man steals their swan suit; witches and shamans who were believed to fly by various means, including the ability to change shape; Valkyries who can appear as birds; ḍākinīs who change shape at will; fairies (like Morgan le Fay) who can soar or change into rock; and even Wonder Woman, who changes from dowdy, bespectacled Diana Prince into a gorgeous superhero. Shape- shifters can change others, too; certain women (like Circe) were said to have the power to turn men into beasts—a clear allusion to the similarity of animal and human nature when it comes to sexuality. Cinderella’s fairy godmother could change both things (pumpkins into carriages) and beings (mice into horses, a rat and lizards into men).17 From the male perspective, women are shape- shifters par excellence, changing from desirable, young, acquiescent women into ruthless shrews.

Shape- shifting breaches fundamental boundaries, such as those between humans and animals and between the divine and mundane realms. Shape- shifters are unnerving because they cannot be contained within the primary categories of species, suggesting other, uncanny possibilities that subvert fundamental beliefs about what it is to be human. They are indifferent to differentiation, violating the established order, including the order of gender. By changing out of their human forms, shape- shifting women shatter gendered social conceptions as well as those of species. Traditionally, women are the preservers of orderliness: they keep the cave, hut, house, or apartment separated from the dirt (nature) that drifts in from outside. The witch who turns her broom into a source of freedom rather than domestic drudgery turns the patriarchal social system upside down. Stories about seemingly domesticated captured women who change into birds and fly away not only challenge the so- called benefits women derive from patriarchal marriage, they also reveal male insecurities—and perhaps female fantasies—about the relation of gender to power and bring into question which sex actually has the greater power.18 These stories are, after all, told primarily about women, not men, and they mostly arose in vigorously bi-gendered societies, even those that acknowledged a third sex (chapter 9).

Terrifying in their physical fluidity, shape- shifters are perversions of nature, belonging to the category of the monstrous- feminine, which goes beyond shapeshifters to include women with both animal and human features: the Gorgons, Sirens, Furies, and sphinxes of Greco-Roman mythology, demonesses of all times, and that most unnatural of females, Athena. Athena’s non- womb birth from the head of Zeus qualifies her for the monstrous- feminine; an armed and armored

woman, she maintains an acceptable place in the patriarchal order by helping men kill a rich assortment of female monsters (chapter 2). Also included in this category are the demanding, shape- shifting, and terrifying Indo-Tibetan ḍākinīs, who dance naked except for their ornaments of human skulls and bones, as well as the European witches who rejected Christianity and its ideas about womanhood and sexuality. Even sainted medieval women are perverted by their aerial feats (chapter 10).

The monstrous- feminine is never domestic; its members are paradigms of female inconstancy.19 As Barbara Creed points out, the very phrase “monstrousfeminine” “emphasizes the importance of gender in the construction of her monstrosity.”20 Their power to both arouse and terrify lies in their difference— that of gender and biology.

Women Who Fly is a history of religious and social ideas about aerial females as expressed in legends, myths, rituals, sacred narratives, and artistic productions. It is also about symbolic uses of women in mythology, religion, and society that have shaped, and continue to shape, our social and psychological reality. It focuses on three clusters of religious traditions and folk beliefs that have the most vivid airborne females: the ancient Near Eastern and European cluster (chapters 2 to 5); the Asian cluster (chapters 6, 7, and 11); and the Shamanic cluster (chapter 9), which is rich in rituals that propel the shamaness to the heavens through drumming, songs, and costumes with winglike arms, feathers, and celestial imagery. A fourth cluster, that of the Judeo- Christian-Islamic traditions, is relevant because of the ways in which these traditions problematized both flying and women, a theme embodied in depictions of angels and fairies (chapter 5), male suspicions about the somatic experiences of female Christian mystics (chapter 10), and the persecution of witches who were believed to fly to witches’ sabbaths (chapter 8). Where relevant, other religious traditions are referred to as well. The last chapter compares the lives of two great aviators, the American Amelia Earhart and the German Hanna Reitsch. Close in age but quite different in character, both were used as propagandistic tools of the state that foreshadowed and then prevailed during World War II. These two women and other female aviators, as well as the popular comic book character Wonder Woman, who was created during World War II, are the last of the aerial women hovering over male warriors. In the spirit of friendly redundancy, dates are repeated and there are many crossreferences for readers who may want to read the chapters in a different order.

One question lingered in my mind as I researched this book: why is a “flighty” woman a bad thing, connoting superficiality, instability, unreliability, and silliness?

Flighty also means swift, quick, whimsical, and humorous. So why does the phrase not conjure imaginative, free, creative women who think and live outside the box, especially the box of patriarchy? To “let fly” at someone is to attack, as did aerial warrior women such as the Valkyries and the winged goddesses of war and love. Thus, a flighty woman might just as well be an enraged, courageous woman. But, as will be shown, neither “enraged” nor “courageous” was an approved adjective for women unless they were under the control of patriarchal forces.

Earth, Sky, Women, and Immortality

From time immemorial people all over the world have perceived the universe as divided into distinct but integrated realms. One of the most common depictions has been a threefold division of underworld, earth, and heaven.1 Earth is the everyday world of nature and human beings; the underworld that of the dead and spirits; and heaven the realm of the gods and ancestors. Among the first religious acts of our earliest earthbound forebears was the creation of rituals they believed would connect them to the sky realm, and they placed great esteem on those individuals—priest-kings, shamans, oracles, and the like— who could seemingly contact the heavens through such rituals.2 This was not a one- way transmission; they also envisioned supernatural sky beings who could visit the earth: goddesses, magical beasts, demons, and so on. There is evidence that women were perceived as intermediary beings who could move between realms;3 women, so to speak, had one foot in the mundane world and the other in heavenly and underworld realms that brought new life, death, and regeneration.

Earth, Sky, and Birds

A middle space both separates and connects earth and heaven. Birds, with their ability to travel freely through this space, were often seen as messengers of the

divine. Humans attempted to utilize this space through the rising smoke of cremation fires, as well as through burnt offerings made to ancestors and celestial beings.4 One dramatic example that combines birds and sacred smoke comes from ancient India, where brick fire altars in the shape of birds were constructed.5 In commenting on why the fire altar has this shape, Frits Staal reminds us that in Indian belief “fire, as well as Soma,” two vital components for communion with the divine, “were fetched from heaven by a bird,”6 referring to Rig Veda IV.26 and 27. Soma is an elixir prepared for and consumed at Vedic rituals that may have had hallucinogenic properties to aid participants in accessing the gods. Fire, of course, is essential for the burnt sacrifices that carry offerings to the gods. As early as 1,000 bce, such an altar (Figure 1.1) was prepared with the help of both human and supernatural women for one of the most elaborate Indian rituals, the Agnicayana (“laying of the fire[-altar]”), which took more than a year to construct and required more than one thousand bricks.7 The ritual itself lasted for fourteen days. The time and effort put into this ritual speaks for its importance to those performing it. According to the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (c. eighth century bce), its correct performance leads to immortality:

“What is done here in (the building of) the altar, whereby the Sacrificer conquers recurring death?” Well, he who builds an altar becomes the deity Agni; and Agni (the fire), indeed, is the immortal (element).8

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

woman could have worn the helmet and shot the arrow, could have led troops to attack, ruled with indomitable justice barbarian hordes and lain under a shield noseless in a church, or made a green grass mound on some primeval hillside, that woman was Millicent Bruton. Debarred by her sex and some truancy, too, of the logical faculty (she found it impossible to write a letter to the Times), she had the thought of Empire always at hand, and had acquired from her association with that armoured goddess her ramrod bearing, her robustness of demeanour, so that one could not figure her even in death parted from the earth or roaming territories over which, in some spiritual shape, the Union Jack had ceased to fly. To be not English even among the dead—no, no! Impossible!

But was it Lady Bruton (whom she used to know)? Was it Peter Walsh grown grey? Lady Rosseter asked herself (who had been Sally Seton). It was old Miss Parry certainly—the old aunt who used to be so cross when she stayed at Bourton. Never should she forget running along the passage naked, and being sent for by Miss Parry! And Clarissa! oh Clarissa! Sally caught her by the arm. Clarissa stopped beside them.

“But I can’t stay,” she said. “I shall come later. Wait,” she said, looking at Peter and Sally They must wait, she meant, until all these people had gone.

“I shall come back,” she said, looking at her old friends, Sally and Peter, who were shaking hands, and Sally, remembering the past no doubt, was laughing.

But her voice was wrung of its old ravishing richness; her eyes not aglow as they used to be, when she smoked cigars, when she ran down the passage to fetch her sponge bag, without a stitch of clothing on her, and Ellen Atkins asked, What if the gentlemen had met her? But everybody forgave her. She stole a chicken from the larder because she was hungry in the night; she smoked cigars in her bedroom; she left a priceless book in the punt. But everybody adored her (except perhaps Papa). It was her warmth; her vitality— she would paint, she would write. Old women in the village never to this day forgot to ask after “your friend in the red cloak who seemed

so bright.” She accused Hugh Whitbread, of all people (and there he was, her old friend Hugh, talking to the Portuguese Ambassador), of kissing her in the smoking-room to punish her for saying that women should have votes. Vulgar men did, she said. And Clarissa remembered having to persuade her not to denounce him at family prayers—which she was capable of doing with her daring, her recklessness, her melodramatic love of being the centre of everything and creating scenes, and it was bound, Clarissa used to think, to end in some awful tragedy; her death; her martyrdom; instead of which she had married, quite unexpectedly, a bald man with a large buttonhole who owned, it was said, cotton mills at Manchester. And she had five boys!

She and Peter had settled down together. They were talking: it seemed so familiar—that they should be talking. They would discuss the past. With the two of them (more even than with Richard) she shared her past; the garden; the trees; old Joseph Breitkopf singing Brahms without any voice; the drawing-room wall-paper; the smell of the mats. A part of this Sally must always be; Peter must always be. But she must leave them. There were the Bradshaws, whom she disliked. She must go up to Lady Bradshaw (in grey and silver, balancing like a sea-lion at the edge of its tank, barking for invitations, Duchesses, the typical successful man’s wife), she must go up to Lady Bradshaw and say....

But Lady Bradshaw anticipated her.

“We are shockingly late, dear Mrs. Dalloway, we hardly dared to come in,” she said.

And Sir William, who looked very distinguished, with his grey hair and blue eyes, said yes; they had not been able to resist the temptation. He was talking to Richard about that Bill probably, which they wanted to get through the Commons. Why did the sight of him, talking to Richard, curl her up? He looked what he was, a great doctor A man absolutely at the head of his profession, very powerful, rather worn. For think what cases came before him— people in the uttermost depths of misery; people on the verge of insanity; husbands and wives. He had to decide questions of

appalling difficulty Yet—what she felt was, one wouldn’t like Sir William to see one unhappy. No; not that man.

“How is your son at Eton?” she asked Lady Bradshaw He had just missed his eleven, said Lady Bradshaw, because of the mumps. His father minded even more than he did, she thought “being,” she said, “nothing but a great boy himself.”

Clarissa looked at Sir William, talking to Richard. He did not look like a boy—not in the least like a boy. She had once gone with some one to ask his advice. He had been perfectly right; extremely sensible. But Heavens—what a relief to get out to the street again! There was some poor wretch sobbing, she remembered, in the waiting-room. But she did not know what it was—about Sir William; what exactly she disliked. Only Richard agreed with her, “didn’t like his taste, didn’t like his smell.” But he was extraordinarily able. They were talking about this Bill. Some case, Sir William was mentioning, lowering his voice. It had its bearing upon what he was saying about the deferred effects of shell shock. There must be some provision in the Bill.

Sinking her voice, drawing Mrs. Dalloway into the shelter of a common femininity, a common pride in the illustrious qualities of husbands and their sad tendency to overwork, Lady Bradshaw (poor goose—one didn’t dislike her) murmured how, “just as we were starting, my husband was called up on the telephone, a very sad case. A young man (that is what Sir William is telling Mr. Dalloway) had killed himself. He had been in the army.” Oh! thought Clarissa, in the middle of my party, here’s death, she thought.

She went on, into the little room where the Prime Minister had gone with Lady Bruton. Perhaps there was somebody there. But there was nobody. The chairs still kept the impress of the Prime Minister and Lady Bruton, she turned deferentially, he sitting four-square, authoritatively. They had been talking about India. There was nobody. The party’s splendour fell to the floor, so strange it was to come in alone in her finery.

What business had the Bradshaws to talk of death at her party? A young man had killed himself. And they talked of it at her party—the Bradshaws talked of death. He had killed himself—but how? Always her body went through it first, when she was told, suddenly, of an accident; her dress flamed, her body burnt. He had thrown himself from a window. Up had flashed the ground; through him, blundering, bruising, went the rusty spikes. There he lay with a thud, thud, thud in his brain, and then a suffocation of blackness. So she saw it. But why had he done it? And the Bradshaws talked of it at her party!

She had once thrown a shilling into the Serpentine, never anything more. But he had flung it away. They went on living (she would have to go back; the rooms were still crowded; people kept on coming). They (all day she had been thinking of Bourton, of Peter, of Sally), they would grow old. A thing there was that mattered; a thing, wreathed about with chatter, defaced, obscured in her own life, let drop every day in corruption, lies, chatter. This he had preserved. Death was defiance. Death was an attempt to communicate; people feeling the impossibility of reaching the centre which, mystically, evaded them; closeness drew apart; rapture faded, one was alone. There was an embrace in death.

But this young man who had killed himself—had he plunged holding his treasure? “If it were now to die, ’twere now to be most happy,” she had said to herself once, coming down in white.

Or there were the poets and thinkers. Suppose he had had that passion, and had gone to Sir William Bradshaw, a great doctor yet to her obscurely evil, without sex or lust, extremely polite to women, but capable of some indescribable outrage—forcing your soul, that was it—if this young man had gone to him, and Sir William had impressed him, like that, with his power, might he not then have said (indeed she felt it now), Life is made intolerable; they make life intolerable, men like that?

Then (she had felt it only this morning) there was the terror; the overwhelming incapacity, one’s parents giving it into one’s hands, this life, to be lived to the end, to be walked with serenely; there was in the depths of her heart an awful fear. Even now, quite often if

Richard had not been there reading the Times, so that she could crouch like a bird and gradually revive, send roaring up that immeasurable delight, rubbing stick to stick, one thing with another, she must have perished. But that young man had killed himself. Somehow it was her disaster—her disgrace. It was her punishment to see sink and disappear here a man, there a woman, in this profound darkness, and she forced to stand here in her evening dress. She had schemed; she had pilfered. She was never wholly admirable. She had wanted success. Lady Bexborough and the rest of it. And once she had walked on the terrace at Bourton.

It was due to Richard; she had never been so happy. Nothing could be slow enough; nothing last too long. No pleasure could equal, she thought, straightening the chairs, pushing in one book on the shelf, this having done with the triumphs of youth, lost herself in the process of living, to find it, with a shock of delight, as the sun rose, as the day sank. Many a time had she gone, at Bourton when they were all talking, to look at the sky; or seen it between people’s shoulders at dinner; seen it in London when she could not sleep. She walked to the window

It held, foolish as the idea was, something of her own in it, this country sky, this sky above Westminster She parted the curtains; she looked. Oh, but how surprising!—in the room opposite the old lady stared straight at her! She was going to bed. And the sky. It will be a solemn sky, she had thought, it will be a dusky sky, turning away its cheek in beauty. But there it was—ashen pale, raced over quickly by tapering vast clouds. It was new to her. The wind must have risen. She was going to bed, in the room opposite. It was fascinating to watch her, moving about, that old lady, crossing the room, coming to the window. Could she see her? It was fascinating, with people still laughing and shouting in the drawing-room, to watch that old woman, quite quietly, going to bed. She pulled the blind now. The clock began striking. The young man had killed himself; but she did not pity him; with the clock striking the hour, one, two, three, she did not pity him, with all this going on. There! the old lady had put out her light! the whole house was dark now with this going on, she repeated, and the words came to her, Fear no more the heat of the

sun. She must go back to them. But what an extraordinary night! She felt somehow very like him—the young man who had killed himself. She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. He made her feel the beauty; made her feel the fun. But she must go back. She must assemble. She must find Sally and Peter. And she came in from the little room.

“But where is Clarissa?” said Peter. He was sitting on the sofa with Sally. (After all these years he really could not call her “Lady Rosseter.”) “Where’s the woman gone to?” he asked. “Where’s Clarissa?”

Sally supposed, and so did Peter for the matter of that, that there were people of importance, politicians, whom neither of them knew unless by sight in the picture papers, whom Clarissa had to be nice to, had to talk to. She was with them. Yet there was Richard Dalloway not in the Cabinet. He hadn’t been a success, Sally supposed? For herself, she scarcely ever read the papers. She sometimes saw his name mentioned. But then—well, she lived a very solitary life, in the wilds, Clarissa would say, among great merchants, great manufacturers, men, after all, who did things. She had done things too!

“I have five sons!” she told him.

Lord, Lord, what a change had come over her! the softness of motherhood; its egotism too. Last time they met, Peter remembered, had been among the cauliflowers in the moonlight, the leaves “like rough bronze” she had said, with her literary turn; and she had picked a rose. She had marched him up and down that awful night, after the scene by the fountain; he was to catch the midnight train. Heavens, he had wept!

That was his old trick, opening a pocket-knife, thought Sally, always opening and shutting a knife when he got excited. They had been very, very intimate, she and Peter Walsh, when he was in love with Clarissa, and there was that dreadful, ridiculous scene over Richard Dalloway at lunch. She had called Richard “Wickham.” Why not call Richard “Wickham”? Clarissa had flared up! and indeed they had

never seen each other since, she and Clarissa, not more than half a dozen times perhaps in the last ten years. And Peter Walsh had gone off to India, and she had heard vaguely that he had made an unhappy marriage, and she didn’t know whether he had any children, and she couldn’t ask him, for he had changed. He was rather shrivelled-looking, but kinder, she felt, and she had a real affection for him, for he was connected with her youth, and she still had a little Emily Brontë he had given her, and he was to write, surely? In those days he was to write.

“Have you written?” she asked him, spreading her hand, her firm and shapely hand, on her knee in a way he recalled.

“Not a word!” said Peter Walsh, and she laughed.

She was still attractive, still a personage, Sally Seton. But who was this Rosseter? He wore two camellias on his wedding day—that was all Peter knew of him. “They have myriads of servants, miles of conservatories,” Clarissa wrote; something like that. Sally owned it with a shout of laughter.

“Yes, I have ten thousand a year”—whether before the tax was paid or after, she couldn’t remember, for her husband, “whom you must meet,” she said, “whom you would like,” she said, did all that for her.

And Sally used to be in rags and tatters. She had pawned her grandmother’s ring which Marie Antoinette had given her greatgrandfather to come to Bourton.

Oh yes, Sally remembered; she had it still, a ruby ring which Marie Antoinette had given her great-grandfather. She never had a penny to her name in those days, and going to Bourton always meant some frightful pinch. But going to Bourton had meant so much to her—had kept her sane, she believed, so unhappy had she been at home. But that was all a thing of the past—all over now, she said. And Mr. Parry was dead; and Miss Parry was still alive. Never had he had such a shock in his life! said Peter. He had been quite certain she was dead. And the marriage had been, Sally supposed, a success? And that very handsome, very self-possessed young woman was Elizabeth, over there, by the curtains, in red.

(She was like a poplar, she was like a river, she was like a hyacinth, Willie Titcomb was thinking. Oh how much nicer to be in the country and do what she liked! She could hear her poor dog howling, Elizabeth was certain.) She was not a bit like Clarissa, Peter Walsh said.

“Oh, Clarissa!” said Sally.

What Sally felt was simply this. She had owed Clarissa an enormous amount. They had been friends, not acquaintances, friends, and she still saw Clarissa all in white going about the house with her hands full of flowers—to this day tobacco plants made her think of Bourton. But—did Peter understand?—she lacked something. Lacked what was it? She had charm; she had extraordinary charm. But to be frank (and she felt that Peter was an old friend, a real friend—did absence matter? did distance matter? She had often wanted to write to him, but torn it up, yet felt he understood, for people understand without things being said, as one realises growing old, and old she was, had been that afternoon to see her sons at Eton, where they had the mumps), to be quite frank then, how could Clarissa have done it?— married Richard Dalloway? a sportsman, a man who cared only for dogs. Literally, when he came into the room he smelt of the stables. And then all this? She waved her hand.

Hugh Whitbread it was, strolling past in his white waistcoat, dim, fat, blind, past everything he looked, except self-esteem and comfort.

“He’s not going to recognise us,” said Sally, and really she hadn’t the courage—so that was Hugh! the admirable Hugh!

“And what does he do?” she asked Peter.

He blacked the King’s boots or counted bottles at Windsor, Peter told her. Peter kept his sharp tongue still! But Sally must be frank, Peter said. That kiss now, Hugh’s.

On the lips, she assured him, in the smoking-room one evening. She went straight to Clarissa in a rage. Hugh didn’t do such things! Clarissa said, the admirable Hugh! Hugh’s socks were without exception the most beautiful she had ever seen—and now his evening dress. Perfect! And had he children?

“Everybody in the room has six sons at Eton,” Peter told her, except himself. He, thank God, had none. No sons, no daughters, no wife. Well, he didn’t seem to mind, said Sally. He looked younger, she thought, than any of them. But it had been a silly thing to do, in many ways, Peter said, to marry like that; “a perfect goose she was,” he said, but, he said, “we had a splendid time of it,” but how could that be? Sally wondered; what did he mean? and how odd it was to know him and yet not know a single thing that had happened to him. And did he say it out of pride? Very likely, for after all it must be galling for him (though he was an oddity, a sort of sprite, not at all an ordinary man), it must be lonely at his age to have no home, nowhere to go to. But he must stay with them for weeks and weeks. Of course he would; he would love to stay with them, and that was how it came out. All these years the Dalloways had never been once. Time after time they had asked them. Clarissa (for it was Clarissa of course) would not come. For, said Sally, Clarissa was at heart a snob—one had to admit it, a snob. And it was that that was between them, she was convinced. Clarissa thought she had married beneath her, her husband being—she was proud of it—a miner’s son. Every penny they had he had earned. As a little boy (her voice trembled) he had carried great sacks.

(And so she would go on, Peter felt, hour after hour; the miner’s son; people thought she had married beneath her; her five sons; and what was the other thing—plants, hydrangeas, syringas, very, very rare hibiscus lilies that never grow north of the Suez Canal, but she, with one gardener in a suburb near Manchester, had beds of them, positively beds! Now all that Clarissa had escaped, unmaternal as she was.)

A snob was she? Yes, in many ways. Where was she, all this time? It was getting late.

“Yet,” said Sally, “when I heard Clarissa was giving a party, I felt I couldn’t not come—must see her again (and I’m staying in Victoria Street, practically next door). So I just came without an invitation. But,” she whispered, “tell me, do. Who is this?”

It was Mrs. Hilbery, looking for the door For how late it was getting! And, she murmured, as the night grew later, as people went, one found old friends; quiet nooks and corners; and the loveliest views. Did they know, she asked, that they were surrounded by an enchanted garden? Lights and trees and wonderful gleaming lakes and the sky. Just a few fairy lamps, Clarissa Dalloway had said, in the back garden! But she was a magician! It was a park.... And she didn’t know their names, but friends she knew they were, friends without names, songs without words, always the best. But there were so many doors, such unexpected places, she could not find her way.

“Old Mrs. Hilbery,” said Peter; but who was that? that lady standing by the curtain all the evening, without speaking? He knew her face; connected her with Bourton. Surely she used to cut up underclothes at the large table in the window? Davidson, was that her name?

“Oh, that is Ellie Henderson,” said Sally. Clarissa was really very hard on her. She was a cousin, very poor. Clarissa was hard on people.

She was rather, said Peter. Yet, said Sally, in her emotional way, with a rush of that enthusiasm which Peter used to love her for, yet dreaded a little now, so effusive she might become—how generous to her friends Clarissa was! and what a rare quality one found it, and how sometimes at night or on Christmas Day, when she counted up her blessings, she put that friendship first. They were young; that was it. Clarissa was pure-hearted; that was it. Peter would think her sentimental. So she was. For she had come to feel that it was the only thing worth saying—what one felt. Cleverness was silly. One must say simply what one felt.

“But I do not know,” said Peter Walsh, “what I feel.”

Poor Peter, thought Sally. Why did not Clarissa come and talk to them? That was what he was longing for. She knew it. All the time he was thinking only of Clarissa, and was fidgeting with his knife.

He had not found life simple, Peter said. His relations with Clarissa had not been simple. It had spoilt his life, he said. (They had been so

intimate—he and Sally Seton, it was absurd not to say it.) One could not be in love twice, he said. And what could she say? Still, it is better to have loved (but he would think her sentimental—he used to be so sharp). He must come and stay with them in Manchester. That is all very true, he said. All very true. He would love to come and stay with them, directly he had done what he had to do in London. And Clarissa had cared for him more than she had ever cared for Richard. Sally was positive of that.

“No, no, no!” said Peter (Sally should not have said that—she went too far). That good fellow—there he was at the end of the room, holding forth, the same as ever, dear old Richard. Who was he talking to? Sally asked, that very distinguished-looking man? Living in the wilds as she did, she had an insatiable curiosity to know who people were. But Peter did not know. He did not like his looks, he said, probably a Cabinet Minister. Of them all, Richard seemed to him the best, he said—the most disinterested.

“But what has he done?” Sally asked. Public work, she supposed. And were they happy together? Sally asked (she herself was extremely happy); for, she admitted, she knew nothing about them, only jumped to conclusions, as one does, for what can one know even of the people one lives with every day? she asked. Are we not all prisoners? She had read a wonderful play about a man who scratched on the wall of his cell, and she had felt that was true of life —one scratched on the wall. Despairing of human relationships (people were so difficult), she often went into her garden and got from her flowers a peace which men and women never gave her. But no; he did not like cabbages; he preferred human beings, Peter said. Indeed, the young are beautiful, Sally said, watching Elizabeth cross the room. How unlike Clarissa at her age! Could he make anything of her? She would not open her lips. Not much, not yet, Peter admitted. She was like a lily, Sally said, a lily by the side of a pool. But Peter did not agree that we know nothing. We know everything, he said; at least he did.

But these two, Sally whispered, these two coming now (and really she must go, if Clarissa did not come soon), this distinguishedlooking man and his rather common-looking wife who had been talking to Richard—what could one know about people like that?

“That they’re damnable humbugs,” said Peter, looking at them casually. He made Sally laugh.

But Sir William Bradshaw stopped at the door to look at a picture. He looked in the corner for the engraver’s name. His wife looked too. Sir William Bradshaw was so interested in art.

When one was young, said Peter, one was too much excited to know people. Now that one was old, fifty-two to be precise (Sally was fiftyfive, in body, she said, but her heart was like a girl’s of twenty); now that one was mature then, said Peter, one could watch, one could understand, and one did not lose the power of feeling, he said. No, that is true, said Sally. She felt more deeply, more passionately, every year. It increased, he said, alas, perhaps, but one should be glad of it—it went on increasing in his experience. There was some one in India. He would like to tell Sally about her. He would like Sally to know her. She was married, he said. She had two small children. They must all come to Manchester, said Sally—he must promise before they left.

There’s Elizabeth, he said, she feels not half what we feel, not yet. But, said Sally, watching Elizabeth go to her father, one can see they are devoted to each other. She could feel it by the way Elizabeth went to her father

For her father had been looking at her, as he stood talking to the Bradshaws, and he had thought to himself, Who is that lovely girl? And suddenly he realised that it was his Elizabeth, and he had not recognised her, she looked so lovely in her pink frock! Elizabeth had felt him looking at her as she talked to Willie Titcomb. So she went to him and they stood together, now that the party was almost over, looking at the people going, and the rooms getting emptier and emptier, with things scattered on the floor. Even Ellie Henderson was going, nearly last of all, though no one had spoken to her, but she

had wanted to see everything, to tell Edith. And Richard and Elizabeth were rather glad it was over, but Richard was proud of his daughter. And he had not meant to tell her, but he could not help telling her. He had looked at her, he said, and he had wondered, Who is that lovely girl? and it was his daughter! That did make her happy. But her poor dog was howling.

“Richard has improved. You are right,” said Sally. “I shall go and talk to him. I shall say good-night. What does the brain matter,” said Lady Rosseter, getting up, “compared with the heart?”

“I will come,” said Peter, but he sat on for a moment. What is this terror? what is this ecstasy? he thought to himself. What is it that fills me with extraordinary excitement?

It is Clarissa, he said.

For there she was.