Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/the-therapeutic-properties-of-electromagnetic-waves-f rom-pulsed-fields-to-rifing-marcello-allegretti/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Frequencies of Rifing From the first frequencies discovered by Royal Rife to today Guide to selection and use of Spooky2 frequencies Marcello Allegretti

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-frequencies-of-rifing-fromthe-first-frequencies-discovered-by-royal-rife-to-today-guide-toselection-and-use-of-spooky2-frequencies-marcello-allegretti/

Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields for Clinical Applications

1st Edition Marko Markov (Editor)

https://textbookfull.com/product/pulsed-electromagnetic-fieldsfor-clinical-applications-1st-edition-marko-markov-editor/

Shielding of Electromagnetic Waves: Theory and Practice

George M. Kunkel

https://textbookfull.com/product/shielding-of-electromagneticwaves-theory-and-practice-george-m-kunkel/

Biological and medical aspects of electromagnetic fields Fourth Edition Barnes

https://textbookfull.com/product/biological-and-medical-aspectsof-electromagnetic-fields-fourth-edition-barnes/

Principles of Electromagnetic Waves and Materials, Second Edition Dikshitulu K. Kalluri

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-electromagneticwaves-and-materials-second-edition-dikshitulu-k-kalluri/

Electromagnetic Waves and Antennas, Exercise Book 1st Edition Sophocles J. Orfanidis

https://textbookfull.com/product/electromagnetic-waves-andantennas-exercise-book-1st-edition-sophocles-j-orfanidis/

Transient

Electromagnetic-Thermal

Nondestructive

Testing. Pulsed Eddy Current and Transient Eddy Current Thermography Yunze He

https://textbookfull.com/product/transient-electromagneticthermal-nondestructive-testing-pulsed-eddy-current-and-transienteddy-current-thermography-yunze-he/

Planets And Electromagnetic waves First Edition G. Udhaya Sankar & C. Ganesa Moorthy

https://textbookfull.com/product/planets-and-electromagneticwaves-first-edition-g-udhaya-sankar-c-ganesa-moorthy/ Lycopene : nutritional, medicinal and therapeutic properties First Edition Preedy

https://textbookfull.com/product/lycopene-nutritional-medicinaland-therapeutic-properties-first-edition-preedy/

M. Allegretti

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

FromPulsedFieldsto Rifing

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

Copyright © 2018 Ing. Marcello Allegretti

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 9781719822237

ISBN-13: ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Therearemanyevents,stimuliandfriends,whichhaveledmeto writethis book.

Therefore,Iwishtothankthefollowingpeople: MyfriendNatalePetti,DirectoroftheAronSchools(Bari,Italy),for his teachings,hissupport,hissuggestionsandhisgenerosity, JohnWhite,agreatscientist,whoisrevolutionizingtheworldof Rifinganda

friendwhointriguedmeandcompelledmetoconquertheworldof frequenciesand myresearch",

LeonardoRighini,who,withhisexperienceandtechnicalpreparation, has helpedmedissolvedoubtsandprovidedinformationandhelpful ideasin

electrotherapyandmagnetotherapy,

DomenicoCantatore,forhisinvaluablecontributioninthescientific revision ofthetext,

StefanoMarcuzzo,forhiscontributioninthenotionsof neuroacoustics,

IreneGomulka,forherexperienceandfortherevisionoftheEnglish text,

Allthosewhosupportedmeandencouragedmeinmystudiesand research,

AlltheFriends,whowiththeirsuggestionsandindications,helped memake thisbookbetter ,

Andfinally…mysonMarco,whoinspiresandstimulatesmeevery dayinmy studiesandresearch. Legal Notice & Disclaimer

This book is a work to be considered as a notional aid for the knowledge of techniques and application methods of electronic devices, which use electromagnetic fields for various purposes. The information contained herein is not intended as, and should not be used for, therapeutic, diagnostic or prescriptive purposes, nor to prevent, treat or cure disease, but for education and responsible experimentation only.

The information this book contains can in no way replace the work of a medically trained professional. Please consult a licensed health practitioner for medical advice.

The author cannot guarantee the reliability of the information contained herein and there are no errors and/or omissions. The information and concepts within this guide must not be considered or construed in any way to be medical advice or treatment.

The author of this book cannot be held liable for any consequences, harmful or

Carlo Rubbia, an internationally renowned scientist, won the Nobel Prize with a formula that shows that we are able to observe only one billionth of the characteristics of an object.

Current physics tells us that we know at most five percent of the reality that surrounds us, the rest is made of dark matter, that is invisible to our eyes and to the tools we have available to measure it and therefore unknown to us. The present medical science seems to have detached itself from the laws of physics and nature, denying the evident existence of the laws that regulate the basic functions of our body. Just talking about quantum physics and quantum medicine to our doctors is uncomfortable! However, the truth is that they cannot define their scientific discipline without accepting science in its entirety.

The human body consists of apparatuses, which are made up of organs, made of tissues, composed of cells, in turn made up of organelles, composed of

macromolecules, constructed from molecules, and at the base of all these, we have atoms. At the root of the human Biology, is Physics, because at the base of the human body there are the atoms.

Physics is the only true science, which exists as the only discipline that can be confirmed through the scientific method. To deny the effects of physics, which considers the atom as a basic unit on human health, is like not accepting that a house made of bricks, which is composed of earth or clay. We accept that the quality of the bricks as fundamental, but we do not consider that the clay that composes them is fundamental and some even deny the influence of the clay itself. It is absurd to believe that some are able to think that!

A curious and ethical scientist, faced with empirical and repeatable evidence that he cannot explain, wonders what he has not understood or what function unknown to him can allow this phenomenon. He does not say that the phenomenon

is not true, only because he cannot explain it. This is not scientific and leaves no room for growth to our science.

The body is a holistic system that must be analyzed, viewed and considered at many levels: Biological, Psychological and Informational, therefore Quantum, specifying that the quantum reading does not exclude the relative Einsteinian one. I mean that the laws of quantum physics and those of relative physics collaborate in giving us the most complete reading we could ever have to date.

7

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

It is obvious and proven that nutrition is a fundamental component for human health. Food can change the fate of our tissues and our cells, as it could also change, if we were exposed to radiation, chemicals, toxic substances, emotional stresses and traumas, substances or microorganisms. After what has been affirmed, it seems quite obvious that we must take care of our body.

The frequency, electromagnetic, informational and scalar approaches, allow the body to be treated in a non-invasive way and, if well used, can give truly impressive results. Of course, with applying the investigative systems and the various treatments, you will begin to experience a healthy change, which must be integrated with various other methods, as needed. This is the vision I have been proposing for years with the BioPsicoQuantistica, an integrated system that recognizes the various and very different skills according to need, a system which, by rejecting every fundamentalist approach, recognizes a probable aid in every discipline or instrument of treatment. In this vision, the use of electromagnetic waves is a valuable evaluation and treatment tool, in an integrated and holistic perspective.

I am, therefore, very happy to be able to comment on this work done by my

dear and esteemed friend Marcello Allegretti, a trained scientist, a man of great heart, culture and humility. For about 20 years, Marcello has been involved in

search of informational therapies. He has been able to describe very complicated topics in a concise and simple way, in which to make them understandable even to non-professionals. Nothing could be more natural for someone like him, who in his previous publications had me amazed at the completeness and precision of his works, which always appear to be meticulous and at the same time simple to comprehend. After reading this text, there was a sentence that came out of my mouth quite spontaneously and I exclaimed: "Finally a book in which someone spoke in a precise, simple, concise and scientific way about informational therapies!” This is a very useful book, which is necessary for operators in this sector and especially for those who are doing Treatments or Quantum Therapies, as if they were the latest discovery of modern magic. This book, which speaks of Science, will be able to teach many. To the readers of this book, remember, that in terms of health, the

multifactorial always applies to different levels and that utilizing only one approach always proves to be poor and limited. To the skeptics, I say that curiosity is at the base of the impulse, which has driven every scientist. So give it a try and maybe you can change your mind.

Dr.NatalePetti

ClinicalPsychologistandNaturopathBPQ

8

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

Preface byJohnWhite

In 1931, the world celebrated “The End of All Disease.” The answer to illnesses had been found; electromagnetic waves. Independent clinical trials confirmed that cancer had been conquered. Then the unbelievable happened.

Faced with a disastrous loss of drug income, authorities decided to censor the information. The genius who had discovered the answer to disease eventually died a broken man.

Large corporation decisions made are based on earnings, market share and growth. Ethics and morals play second-fiddle to profit. The casualty in the drive for prosperity is humanity. Yet, true wealth is health.

My name is John White. I created the Spooky2 health system, write the Spooky2 software and develop the Spooky2 hardware. My goal is to empower people with knowledge and equipment, so they can take control over their own health.

Marcello and I are close friends. We first exchanged emails in 2016, when he kindly offered to translate the Spooky2 manual into Italian; his mother tongue. Since then, we have kept in contact to exchange ideas. Nevertheless, it came as a surprise when Marcello asked me to write a preface for his new book.

I was fortunate to meet Marcello in person during the Italian portion of the

2017 Spooky2 European tour. What struck me most about him was his astonishing enthusiasm and energy. His strive for perfection and eye for detail is only surpassed

by his love of his family, for he is blessed with a loving wife and two wonderful sons.

Marcello Allegretti is an exceptional electronics and medical expert who has an innate ability to transform complex concepts in a language we can all understand.

What others struggle with, Marcello takes in his stride. As you read each chapter, you will understand concepts which even experts may find difficult to comprehend.

This is the Marcello magic.

9

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

In a previous book titled: ThefrequenciesofRifing, Marcello listed the frequencies, which are best suited for different health conditions. In this book,

Marcello goes further, and explains how frequencies actually work.

Marcello begins by describing how electromagnetic fields affect body tissue, and why frequency is so important. Each frequency can affect the body in different ways.

The next chapter reveals the many ways electromagnetic fields can be applied.

Never shy of detail, Marcello covers the full spectrum, from light waves down to temperature.

Pulsed magnetic fields can markedly reduce recovery time. NASA used these fields for astronauts during missions. A self-treatment method was developed using PEMF (Pulsed Electromagnetic Field) devices. Marcello dedicates an entire chapter to this important subject.

The final chapters discuss Rifing. A term, which means applying precise frequencies to resonate and destroy pathogens. At the beginning of this preface, I

talked about the “The End of All Disease,” which was celebrated back in 1931. A

man had discovered the cure for cancer, tuberculosis, tetanus and much more. His

name was Royal Raymond Rife. The terms “Rife”treatmentsand “Rifing”are in memory of this great man.

Imagine a world without disease. Royal Rife found the answer over 80 years

ago. TheTherapeuticPropertiesofElectromagneticWavesensures this solution is not forgotten.

So read on, intrepid reader. Electromagnetic waves can indeed heal. And, you are about to discover how!

JohnWhite 10

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

Introduction

The growing interest and use of technologies that utilize electromagnetic waves for therapeutic purposes and the exponential increase of scientific publications on this subject, have pushed me to try to gather all the information possible, in order to clarify first of all to me, which methods can be used to achieve the most benefits and with the quickest solutions, as this is necessary when you are afflicted by a health problem.

Embracing and explaining, at least in a summary way, such a wide range of

applications with electromagnetic waves has not been easy, since the technologies used are from the beginning of the last century to date, and are many. These notions are therefore addressed to a very large audience, which includes researchers, doctors, holistic operators, electronic technicians or specialists in bioengineering, but also any person who has an interest in deepening or learning more about these topics and can then decide if and how to use them in the most targeted way. For this reason I have tried to use a language that everyone can understand and maybe I have elaborated on explanations that for some may seem completely superfluous or trivial.

Another of the fundamental purposes of this book is to try to offer all the most reliable scientific explanations concerning the mechanisms of interaction between electromagnetic fields and organic tissues. It is absolutely normal for every researcher to try to demonstrate and illustrate how a series of electrical, chemical

and biological reactions can take place and then produce certain results. Many have given plausible and satisfying explanations; several others have come to identical conclusions. All the articles that I had the opportunity to review have focused on describing the biological effects (e.g., increase in cell membrane potential), and almost never understanding or pointing out that the real effect of the electromagnetic waves, is that the electromagnetic waves lead to stimulation genetics. Fortunately, this goal has been achieved by NASA, which, thanks to the indepth studies, carried out in its well-equipped laboratories, has finally provided a precise and detailed scientific explanation. Probably only NASA could do it, since independent researchers do not have the necessary resources and pharmaceutical 11

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves companies have no interest in such technologies, which often oppose or discredit such research.

Finally, when all the possible interpretations offered by the scientific world are

still not enough, it remains only somethingimmaterial, which cannot be explained satisfactorily with traditional theories: it is the content of information that an electromagnetic signal can provide. In this case, only quantum physics can help us.

Understanding a phenomenon that can be explained with such theories can be quite complicated, so, we can all at least verify its practical effects, the empirical results.

These topics will be dealt with in the second to the last chapter of this book.

Lastly, I think it is important to point out that some of the topics discussed, in particular those concerning Rifing and pathogens, can be considered by most of the scientific community as having no solid foundation and clinical trials to prove its effectiveness. Many of the theories encountered, have been and still are opposed by the medical and scientific community, despite the surprising results obtained.

However, since these technologies are officially used in many countries, I thought it

useful to provide all the latest concepts for your review. It will take some time and evolution to establish its truthfulness and effectiveness.

Eachdoctrinepassesthroughthreephases: Itisattackedanddeclaredabsurd.

Thenitisadmittedthatitistrueandevident,butirrelevant.

Intheend,itsrealimportanceisrecognized andhisdetractorsclaimthehonorofhavingdiscoveredit.

WilliamJones 12

The Therapeutic Properties of Electromagnetic Waves

The reactions of cells and tissues exposed to electromagnetic fields

Many people are currently thinking that a satisfactory explanation for using electromagnetic fields on the cells of living organisms with different frequencies and waveforms is still lacking. This depends first of all on the incomplete knowledge of the phenomena at the genetic level, of the cellular membrane, of the organelles contained within it, of the extracellular matrix and in general of the structural complexity of the biological tissues and their inhomogeneity. Nevertheless, we will

try to expose the most accredited hypotheses, which the research carried out in this sector offers us.

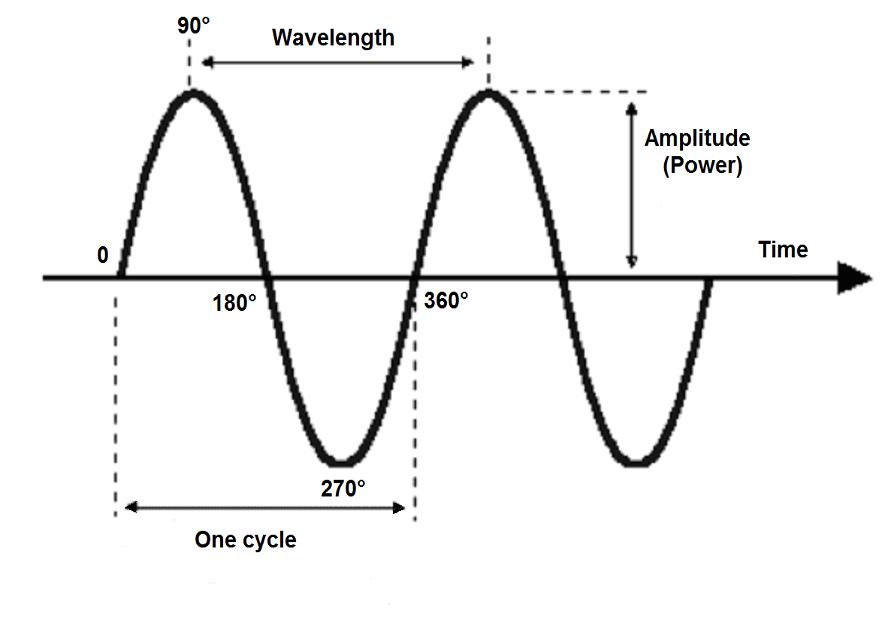

To understand how normal and then pulsed electromagnetic waves can act on an organism and in particular on cells and tissues, it is first necessary to recall some simple concepts of physics.

Sinusoidal Wave: the entire waveform has the great importance. It is actually a very simple and natural curve, which underlies many physical phenomena. The sound is made of sinusoidal waves and so are the light, the voltage and the electric current supply to our homes. Sinusoids are the fundamental "bricks" with which any other waveform can be constructed. In practice, by adding different sine waves with different frequencies and amplitudes, any signal can be created with any waveform.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

phrase means no more than “men ” [522]

62. Regarding Gunnar’s harp-playing, and his death, cf. Oddrunargratr, 27–30 and notes, and Atlakvitha, 34. Toes (literally “sole-twigs”): the Volsungasaga explains that Gunnar’s hands were bound. Rafters: thus literally, and probably correctly; Gering has an ingenious but unlikely theory that the word means “harp.”

63. There is some doubt as to the exact meaning of line 2. After this line two lines may have been lost; Grundtvig adds: “Few braver shall ever | be found on the earth, / Or loftier men | in the world ever live.”

64. Wise one: Guthrun. The manuscript marks line 3 as beginning a new stanza. [523]

65. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker.

66. The manuscript does not name the speaker. The negative in the first half of line 1 is uncertain, and most editions make the clause read “Of this guilt I can free myself.” The fairest, etc.: i.e., I have often failed to do the wise thing.

67. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker. Requital, etc.: it is not clear just to what Guthrun refers; perhaps she is thinking of Sigurth’s death, or possibly the poet had in mind his reference to the slaying of her mother in stanza 53. [524]

68. Line 5 is very probably a later addition, though some editors question line 3 instead.

69. Guthrun suddenly changes her tone in order to make Atli believe that she is submissive to his will, and thus to gain time for her vengeance. Line 2 in the original is thoroughly obscure; it runs literally: “On the knee goes the fist | if the twigs are taken off.” Perhaps the word meaning “fist” may also have meant “tree-top,” as

Gering suggests, or perhaps the line is an illogical blending of the ideas contained in lines 1 and 3.

70. The manuscript indicates line 3 as the beginning of a new stanza. Two shields, etc.: i.e., Guthrun concealed her hostility (symbolized by a red shield, cf. Helgakvitha Hundingsbana I, 34) by a show of friendliness (a white shield). [525]

71. Many editions make a separate stanza of lines 1–2, some of them suggesting the loss of two lines, and combine lines 3–4 with lines 1–2 of stanza 72. The manuscript marks both lines 1 and 3 as beginning stanzas.

72. The manuscript marks line 3 as beginning a new stanza; some editions make a separate stanza of lines 3–5, while others combine them with lines 1–2 of stanza 73. Line 2 in the original is clearly defective, the verb being omitted. The meaning of line 3 is uncertain; the Volsungasaga paraphrase has: “At evening she took the sons of King Atli (Erp and Eitil) where they were playing with a block of wood.” Probably the text of the line as we have it is faulty. Lines 4–5 may possibly have been expanded out of a single line, or line 5 may be spurious [526]

73. The manuscript does not name the speakers. It indicates line 3 as beginning a new stanza, in which it is followed by many editions. The Volsungasaga paraphrases line 4 thus: “But it is shameful for thee to do this.” Either the text of the line has been changed or the Volsungasaga compilers misunderstood it. The angry one: Atli.

74. The manuscript indicates line 3 as beginning a new stanza.

75. The manuscript does not name the speaker. [527]

76. Morning: Guthrun refers to Atli’s taunt in stanza 64.

77. The manuscript indicates no gap (lines 1–2), and most editions make a single line, despite the defective meter: “Thy sons hast thou

lost | as thou never shouldst lose them ” The second part of line 2 is in the original identical with the second half of line 3 of stanza 80, and may perhaps have been inserted here by mistake. Skulls: it is possible that line 3 was borrowed from a poem belonging to the Völund tradition (cf. Völundarkvitha, 25 and 37), and the idea doubtless came from some such source, but probably the poet inserted it in a line of his own composition to give an added touch of horror. The Volsungasaga follows the Atlamol in including this incident. [528]

78. Some editions add lines 3–4 to stanza 79; Finnur Jonsson marks them as probably spurious.

79. Perhaps these two lines should form part of stanza 78, or perhaps they, rather than lines 3–4 of stanza 78, are a later addition. A gap of two lines after line 1 has also been conjectured.

80. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker

81. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker. Lines 1–2 may be the remains of a separate stanza; Grundtvig adds: “Thou wast foolish, Atli, | when wise thou didst feel, / Ever the whole | of thy race did I hate.” The Volsungasaga paraphrase, however, indicates no gap. Many editions make a separate stanza of lines 3–6, which, in the Volsungasaga, are paraphrased as a speech of Atli’s. Lines 5–6 may be spurious. [529]

82. The manuscript does not indicate the speakers. Many editions make two separate stanzas of the four lines. Another light: a fairly clear indication of the influence of Christianity; cf. Introductory Note.

83. The manuscript marks line 3 as the beginning of a new stanza. Hniflung: the Volsungasaga says that “Hogni had a son who was called Hniflung,” but the name appears to be nothing more than the familiar “Niflung” applied in general to the sons of Gjuki and their people. On the spelling cf. note on stanza 44. [530]This son of Hogni appears in later versions of the story. In the Thithrekssaga he is

called Aldrian, and is begotten by Hogni the night before his death Aldrian grows up and finally shuts Attila in a cave where he starves to death. The poet here has incorporated the idea, which finds no parallel in the Atlakvitha, without troubling himself to straighten out the chronology.

84. Line 4 may be in Fornyrthislag, and from another poem.

85. The manuscript marks line 3 as beginning a new stanza. The Volsungasaga makes line 2 part of Atli’s speech

86. The manuscript does not name the speakers. It marks line 4 as the beginning of a new stanza, and many editions follow this arrangement, in most cases making a stanza of lines 4–5 and line 1 of stanza 87. However, line 1 may well have been interpolated here from stanza 75. Grundtvig adds after line 3: “His father he avenged, | and his kinsmen fully.” Some editors assume the loss of one or two lines after line 5 [531]

87. The manuscript marks line 2 as beginning a new stanza, and some editions make a stanza out of lines 2–4 and line 1 of stanza 88.

88. The manuscript marks line 2 as the beginning of a stanza, and many editions make a stanza out of lines 2–4, or combine them with stanza 89. Some question the genuineness of line 4.

89. Many editions assume a gap of one line after line 3; [532]Grundtvig adds: “Bit-champing horses | and wheel-wagons bright.” Line 4 may be spurious. Greater: i.e., the silver which Atli gave Guthrun was of greater value even than the honor of receiving such royal gifts.

90. Some editions mark line 3 as spurious or defective. The manuscript marks line 4 as the beginning of a new stanza. The land, etc : there is much obscurity as to the significance of this line Some editors omit or question “me,” in which case Atli is apparently

reproaching Guthrun for having incited him to fight with his brothers to win for himself the whole of Buthli’s land. In stanza 91 Guthrun denies that she was to blame for Atli’s quarrels with his brothers. The Volsungasaga reading supports this interpretation. The historical Attila did actually have his brother, Bleda, killed in order to have the sole rule. The treasure: Sigurth’s hoard, which Atli claimed as the brother of Brynhild and husband of Guthrun, Sigurth’s widow, but which Gunnar and Hogni kept for themselves, with, as Atli here charges, Guthrun’s connivance. My mother: the only other reference to Atli’s mother is in Oddrunargratr, 30, wherein she appears as the adder who stings Gunnar to death, and in the prose passages based on that stanza [533]

91. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker. It marks both lines 4 and 5 as beginning new stanzas, but line 5 is presumably an interpolation. The text of the second half of line 2 is obscure, and many emendations have been suggested. Ye brothers: cf. note on stanza 90. Half: i.e., two of Atli’s brothers were killed, the other two dying in the battle with Gunnar and Hogni; cf. stanza 51.

92. From the land: this maritime expedition of Guthrun and her two brothers, Gunnar and Hogni (the poet seems to know nothing of her half-brother, Gotthorm), with Sigurth seems to have been a pure invention of the poet’s, inserted for the benefit of his Greenland hearers. Nothing further is reported concerning it.

93. The forest: i.e., men who were outlawed in the conquered land were restored to their rights—another purely Norse touch. [534]

94. Hun-king: Sigurth, though most illogically so called; cf Sigurtharkvitha en skamma, 4 and note. The Volsungasaga paraphrase of line 2 is so remote as to be puzzling: “It was little to bear the name of widow.” Perhaps, however, the word “not” fell out between “was” and “little.”

95. Thing, etc : here the poet makes Atli into a typical Norse landowner, going to the “Thing,” or general law council, to settle his disputes. Even the compilers of the Volsungasaga could not accept this, and in their paraphrase changed “Thing” to “battle.” The text of the second half of line 2 is uncertain. The manuscript leaves a blank to indicate the gap in line 4; Grundtvig adds: “as beseems not a king.” [535]

97. The manuscript does not indicate the speaker Many editors assume a gap either before or after line 1. A ship: the burial of Norse chiefs in ships was of frequent occurrence, but the Greenland poet’s application of the custom to Atli is somewhat grotesque.

98. Heirs, etc.: merely a stock phrase, here quite meaningless, as Atli’s heirs had all been killed. Long: cf. Guthrunarhvot, introductory prose. [536]

[Contents]