The Rome We Have Lost John Pemble

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/the-rome-we-have-lost-john-pemble/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The knowledge we have lost in information : the history of information in modern economics 1st Edition Philip Mirowski

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-knowledge-we-have-lost-ininformation-the-history-of-information-in-modern-economics-1stedition-philip-mirowski/

The Complexity Paradox The More Answers We Find the More Questions We Have 1st Edition Kenneth Mossman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-complexity-paradox-the-moreanswers-we-find-the-more-questions-we-have-1st-edition-kennethmossman/

Everything We Might Have Been 1st Edition Megan Walker

https://textbookfull.com/product/everything-we-might-havebeen-1st-edition-megan-walker/

The Last Natural Man: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? 1st Edition Robert A. Norman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-last-natural-man-where-havewe-been-and-where-are-we-going-1st-edition-robert-a-norman/

The Lost Family How DNA Testing is Upending Who We Are

Copeland

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-lost-family-how-dna-testingis-upending-who-we-are-copeland/

Vitruvian Man: Rome Under Construction John Oksanish

https://textbookfull.com/product/vitruvian-man-rome-underconstruction-john-oksanish/

Weird Dinosaurs The Strange New Fossils Challenging Everything We Thought We Knew John Pickrell

https://textbookfull.com/product/weird-dinosaurs-the-strange-newfossils-challenging-everything-we-thought-we-knew-john-pickrell/

We Have Root Even More Advice from Schneier on Security 1st Edition Schneier

https://textbookfull.com/product/we-have-root-even-more-advicefrom-schneier-on-security-1st-edition-schneier/

The allure of battle: a history of how wars have been won and lost 1st Edition Cathal

J.

Nolan

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-allure-of-battle-a-historyof-how-wars-have-been-won-and-lost-1st-edition-cathal-j-nolan/

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

but not always connected with, right motor paralysis we have the inability to use words in speaking, known as aphasia, aphemia, alalia, and others. The first of these names is the one most frequently used. Agraphia is the inability to use words in writing.

On the receptive side we have the inability to understand language as presented to the eye (word- or psychic blindness) or to the ear (word- or psychic deafness). A case of the former condition has already been spoken of. One still more singular was reported by Mdlle. Skwortzoff,37 where the patient, not being blind, could not understand letters presented to the eye, but could read with the fingers and understand raised letters like those used by the blind. In a case of the latter kind a man whose ears were normal, and who could distinguish different sounds, answered questions, but entirely at random, though he could read and understand what was written. All these defects are manifestly connected with a peculiar loss of memory, and hence the word amnesia is used sometimes to cover part of the group, and amnesic as an adjective to qualify aphasia.

37 Comptes Rendus de la Société de Biologie, 1883, p. 319.

It should, of course, be understood that the muscles are not paralyzed, so that glottis, lips, tongue, and fingers are capable of making the necessary movements to produce words, and, on the other hand, that the senses of sight and hearing are intact. Aphasia was confounded by some of the older writers with paralysis of these organs, and the whole grouped together under the name of alalia. Even now the distinction is not always clearly observed.

The act of speaking, according to Kussmaul,38 consists in three stages or processes: the preparation in the intelligence and feelings of the matter to be uttered; the diction, or the formation of the words internally, together with their syntax; the articulation, or formation of words outwardly, irrespective of their connection with one another in the matter spoken. Defects in the first condition have already been spoken of. In the entire absence of mind, as in the deepest apoplexy, aphasia can hardly be said to exist, and it is only later that it becomes manifest. If the second stage is defective, amnesic aphasia

exists, and if the third, ataxic. In the great majority of cases of aphasia the loss of memory is the most important factor; and as this exists whatever be the mode in which it is desired to express the idea, amnesic aphasia is accompanied by agraphia. In those cases, however, in which the patient retains a few words, they are not always the same for speech and writing. Occasionally an instance is found where a person can write perfectly well and possesses complete intelligence, but is unable to speak a word. This is pure ataxic aphasia, and is certainly rare. An ataxic agraphia is less easy to detect, since the aphasic patient is likely to be paralyzed upon the right side, and thus unable to write, even if he remembers the words, until educated upon the left side.

38 Ziemssen's Cyclopædia.

There are many degrees and kinds of amnesic aphasia, and, in fact, every case is a study by itself. The slightest might be called physiological; at any rate, it is sufficiently common among people supposed to be well, and consists in the failure to recollect in time for use the name, most frequently of a person, but sometimes of a thing, which is really well known, is recognized at once if suggested, and perhaps returns spontaneously at a later period. Another person may forget only some words which are not recalled at any time, or parts of words. A man appeared among the out-patients at St. Bartholomew's Hospital who had his name written on a piece of paper, because he could not say it, but could carry on a long conversation. There were a few other words he could not say. The more complete cases have no vocabulary at all, or only a few words or syllables applied to all purposes, and perhaps an exclamation or two. In these cases the patient may know perfectly well that he is not expressing his ideas, and he may recognize perfectly well the word when it is told to him or reject a wrong one. If he be, as happens in nearly all cases, unable to pronounce the word after he has recognized it as the one he wished for, there is a combination of ataxic and amnesic aphasia. Incorrect or deficient words may be corrected or supplemented by gestures or intonation. “Yes” may do duty without confusion for “yes” or “no,” according to the tone.

Oaths may be retained, and sometimes an exclamation may be uttered with perfect propriety of application which cannot be repeated deliberately a moment afterward. This emotional use of words may be considered akin to the movement executed by paralyzed limbs under the stimulus of a movement taking place elsewhere, and may lead to an erroneous prognosis of recovery. This curious fact, that more or less automatic expressions are possible when deliberately-willed pronunciation is not, is a probable explanation for the observation which has occasionally been made that an aphasic patient is able to sing words which he cannot speak.

Paraphasia is the use of the wrong words, or of phrases which carry an entirely different meaning from that intended, as when Trousseau's patient receives a guest with politeness and invites her to be seated with the words “cochon, animal, fichue bête,” or an old paralytic, when a lady declines to drive with him, answers with great suavity, “It don't make any damnation to me whether you go or not.”

Word-blindness is more common than word-deafness, and is a frequent accompaniment of aphasia. Rostan, the well-known author of the work on softening of the brain, experienced an attack of aphasia lasting a few hours. The symptom which first attracted his attention was the inability to understand the book, by no means abstruse, which he was reading. He was, however, able carefully to observe his own symptoms, and made signs to be bled, which operation was followed by relief.

Gouty aphasia has been described in a man aged thirty-seven who on several occasions became aphasic, with recovery in a short time. This condition was connected with localized paralysis, and once with entire right hemiplegia. Afterward it was accompanied by convulsions. In the intervals the patient was in fair health.39 It is difficult to imagine the lesion in this case. The reporter speaks of “sudden blocking by a gouty thrombus,” but nothing is known of any thrombus which can disappear so rapidly Ball40 describes twelve attacks of aphasia occurring within nine months, and accompanied by slight paresis and convulsive movements in the right hand. The

patient suffered habitually from migraine. He supposes the cause to have been a temporary anæmia.

39 Brit. Med. Journ., Aug. 28, 1880.

40 L'Encephale, 1883, 2.

Aphasia may be entirely unconnected with motor paralysis, and is then likely to be of shorter duration, though just as complete. Most of these cases probably do not depend upon a lesion of the same kind as when aphasia is only one of several severe symptoms. It shows how delicate a function of the brain memory for words may be, and is possibly the result of a temporary malnutrition or a change in the vascular supply. It has been observed in various conditions of debility and after acute disease. Rostan was diabetic. It has been seen after chloroform narcosis, after santonin (5 cgr.), after fright, and is said to be one of the ordinary symptoms after the bite of venomous serpents. Aphasia and paraphasia may be met with in thorough bromization, and, naturally enough, may be part of the symptomatology of general paralysis. In other cases, even when it is the principal symptom, it depends upon an organic lesion, and is not infrequently the precursor of a more fully-developed attack. The diagnosis is of great importance, and other traces of paralysis should be carefully sought for. This symptom is far more common with occlusion of the vessels than with hemorrhage, though not unknown with the latter 41

41 Lancet, Oct. 11, 1884, p. 655.

By far the most common situation of the softening or hemorrhage which gives rise to aphasia is in the third left frontal convolution (convolution of Broca) or the white substance immediately underlying it. The island of Reil may be involved in some cases where but little damage is done to the third frontal.

In a respectable minority of cases aphasia may be associated with left hemiplegia. A case where a tumor in the third right frontal convolution was found in a case of aphasia is reported by

Habershon.42 It is not stated whether the patient was left-handed. Some of these cases constitute those exceptions which prove the rule, inasmuch as the patient is left-handed, and Hughlings-Jackson has shown that the relationship of aphasia to the side which is congenitally pre-eminent, and which is in the vast majority of human beings the right side, is not destroyed by a partial education of the other side to such acts as writing or using a knife.

42 Med. Times and Gaz., 1881, i.

A lesion in the pons may give rise to aphasia or something closely resembling it, but it is probable that a careful distinction of true aphasia, both amnesic and aphasic, from paralysis or inco-ordination of the muscles of speech, would reduce the number of these cases, and bring the symptom into closer relations with the usual cortical lesions.

A case of congenital aphasia with right hemiplegia has been described.43 When six years old the boy was well developed, though less so on the paralyzed side; intelligent; heard well, but could say only a few words, and those badly. Whatever the lesion, which is thought by the author to have been in the speech-centre, but which may not improbably have been in the pons, it is interesting, as showing that the development of the speech-centre is certainly not accomplished by education.

43 Centralblatt f. d. Med. Wiss., 1873, p. 299.

Post-paralytic chorea is an affection the nature of which is indicated by its name. As the hemiplegia disappears, irregular movements are developed in the paralyzed limbs, sometimes closely resembling ordinary chorea, and at others consisting of irregular movements, as closing and spreading of the fingers, with curious and bizarre stiffenings, extensions, and contractions, sometimes known as athetosis, or in others still a tremor resembling paralysis agitans. These usually cease during sleep. It is very apt to be associated with hemianæsthesia more or less complete, though this may be represented by only a certain amount of numbness. A hemiathetosis

has been observed to be gradually developed from a posthemiplegic hemichorea of the more ordinary form.44

44 Archiv für Psychiatrie, xii. 516.

This affection is not a common one, and Weir Mitchell states that it is common in inverse proportion to the age. He thinks it possible that some of the congenital choreas may be the result of, or at least closely connected with, intra-uterine cerebral paralysis. It remains for years or for life. In the absence of history such a case might present difficulties of diagnosis from the more usual hemichorea, which is not infrequently accompanied by considerable weakness of the affected side.

The temperature in the early days of both hemorrhage and embolism has been described. At a later period of the hemiplegia it remains in the neighborhood of normal. The temperature of the affected side is often higher than that of the sound one for an indefinite period, but in many cases sinks below if atrophy takes place. The time at which the change occurs is extremely variable. Out of ten cases reported by Folet,45 in two of them for three years and one year after the attack the paralyzed side was eight-tenths and six-tenths of a degree respectively the warmer. In three others, of twenty months, four and six years, it was the same on both sides, and in the remaining five the paralyzed limb was a little the cooler. In the last eight there was more or less atrophy

45 Gaz. hébd., 1867.

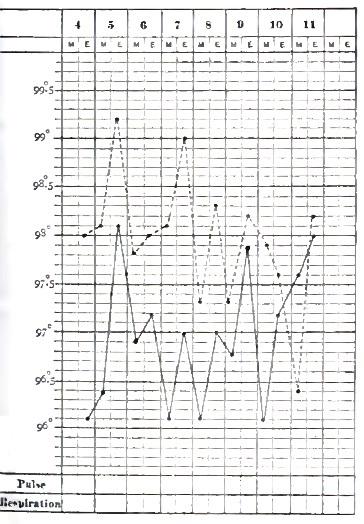

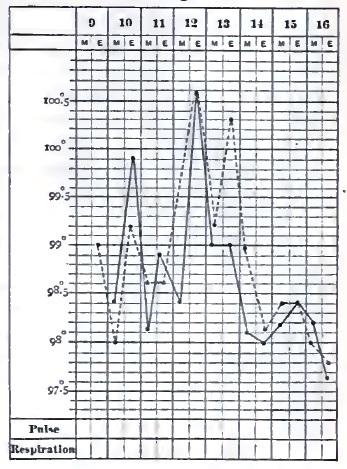

The coincidence of rise of temperature with vascular relaxation has already been noted under the head of Cerebral Hemorrhage. It is not difficult to explain why a vascular paralysis in a comparatively wellnourished limb, especially when the heart is vigorous, may, by allowing a larger amount of warm blood to circulate, raise the temperature, when the same paralysis with atrophied muscles, weak heart, and impaired general health, merely furnishes a larger reservoir in which the slowly-moving blood may be cooled. The accompanying charts represent the difference of temperature

between the two sides in two cases of hemiplegia, the first, O. G. T (Fig. 41), from embolism, and the second, J. B. (Fig. 42), from hemorrhage, the observation being made within two or three weeks of the attack. The dotted line is from the paralyzed side. A subjective feeling of coldness is not uncommon in paralyzed limbs.

The modifications undergone by the urine in a case of cerebral hemorrhage are increase of quantity amounting to polyuria, the urine becoming limpid and afterward returning to the usual color; a diminution in the quantity of urea coinciding with the fall of temperature, and afterward a return to the normal or even above it. When this augmentation is considerable, it constitutes at the same time with a marked elevation of temperature an unfavorable prognostic sign.46 In a case under the observation of the writer, probably of thrombosis, the acid urine has been remarkable for the amount of mucus contained in it, so that it pours from one vessel to another like white of egg. There is a small amount of pus, but no vesical irritation whatever

46 Ollivier, Archives de Physiol., 1876.

Since the trophic centres for the muscles are situated in the spinal cord, cerebral hemiplegia, which does not cut off their connection, does not produce the rapid wasting seen in some cases of spinal paralysis, unless descending degeneration involves the anterior gray columns. The limbs preserve their fulness for a time, although the muscular masses become flabby and slowly atrophy for want of use. This atrophy, however, seldom becomes extreme. The skin of the hands becomes dry, the folds at the knuckles disappear, and the hand loses its expression, looking more like a stuffed glove. The change, however, is not much greater than may be seen in a hand kept for a long time in a bandage. The growth of the nails is retarded, as may be seen by staining them with nitric acid.

If there is any tendency to œdema, as when nephritis is complicated with hemiplegia, the swelling is likely to be much greater upon the paralyzed side. In the adult, of course, there can be no question of the growth of limbs, but when a child becomes hemiplegic from cerebral disease, the limbs grow more slowly and remain smaller, as in a case of ordinary infantile palsy or anterior poliomyelitis.

Much importance has been attached to the fact that large sloughs form with great rapidity upon the nates of the paralyzed side, and Charcot says that this tendency is greater than can be accounted for in any mechanical way. He therefore thinks that a direct trophic influence of the brain upon nutrition is shown. At the very most, however, that can only be a contributory cause, and the freedom of other portions from a similar condition—and that, too, in regions farther removed from the centres of circulation—makes it highly improbable that anything more is necessary to account for it than the less sensitiveness of that side to irritation from urine, roughnesses in the bed, or pressure, and hence neglect. The writer, among a very considerable number of hemiplegias, fatal and otherwise, does not remember to have seen a well-marked case of the kind. Scrupulous cleanliness and changing the position sufficiently often make the preference for the paralyzed side a very slight one.

Arthropathies, consisting in a vegetating, and sometimes an exudative, synovitis, and accompanied by swelling, redness, and pain, are sometimes observed, especially in the upper extremity. They do not appear until fifteen days or a month after the attack.

The most significant change which occurs in the course of a hemiplegia is the development of increased reflexes and rigidity and contracture. After some weeks or months, during which the aspect of the case has not essentially changed, the limbs remaining in the same condition, it will be found on examination that the patellar reflex has become quite energetic, and ankle clonus developed upon the paralyzed side; the arm reflexes from the triceps, biceps, and supinator longus are much exaggerated. This has the same meaning as when similar phenomena are found with spinal disease, and signifies descending degeneration of the postero-lateral columns of the spinal cord, the crossed peduncular tracts. This degeneration may sometimes be traced completely down from the situation of the lesion in the cortical motor centres through the basal ganglia, crura, decussation, and cord. The fuller development of this condition is the contracture or rigidity, which was at one time referred to secondary changes taking place in the neighborhood of the original lesion, as well as to a purely reflex action having no relation to the degeneration of the cord.

The arms are usually flexed at the elbow, the wrists on the arm, and the fingers in the hand. Sometimes, however, the arm is straight. The leg, which is not always affected to the same extent, is generally in extension, though the toes are likely to be flexed. Attempts to move the limbs are resisted strongly, and in such a way as to show the reflex nature of the phenomenon. If an attempt be made to open the fingers of a contractured hand slowly and carefully, it can be often accomplished and the hand held open with but little pressure, but if it is twitched the fingers resist like a spring. The violent attempt to overcome rigidity is often painful.

In some rare cases rapid atrophy of the muscles of one limb may take place. This has been found to coincide with extension of

degenerative changes in the cord to the anterior gray columns.

Late rigidity is an unfortunately clear symptom. There is little if any hope of complete recovery of the use of the limb after it has made its appearance, though it does not prevent walking. After long-continued contracture the activity of the muscles diminishes, but the increase of connective tissue and changes in the joints hold the limb in its fixed position, and the contracture is a more passive one. The electrical reactions of the muscles and their nerves in cerebral hemiplegia are not materially altered, but the neuro-muscular irritability may be somewhat increased for a time by the irritating influence of the cerebral lesion.

In most cases of flaccid cerebral hemiplegia the electrical irritability is somewhat decreased, though retaining the normal character with both currents. Since the muscles and their nerves retain their connection with the spinal nuclei which are their trophic centres, and these nuclei are uninjured, their nutrition does not undergo the changes which affect electric excitability.

When descending degeneration takes place there may be found, coinciding with increased reflex activity and contracture, increased sensitiveness to the electric currents. If the degeneration extend to the anterior columns, as happens in rare cases, the muscles waste rapidly and exhibit the reactions of anterior poliomyelitis—i.e. degenerative.

What has just been said applies to the muscles paralyzed by a central lesion. If, however, with or without a complete hemiplegia, a limited lesion, as in the pons, affects the nucleus of a nerve, the peripheral distribution of that nerve is cut off from its nutritive centre, and it undergoes the usual changes which lead to the reaction of degeneration, so that, in some unusual forms of paralysis, the two kinds of reaction, normal and degenerative, may be present in different sets of muscles.

DIAGNOSIS.—The apoplectiform attack due to hemorrhage or occlusion of the cerebral arteries is to be distinguished from narcotic

poisoning, specially by opium or alcohol, or by coal gas; epilepsy with its succeeding coma; uræmia (so called) or cerebral symptoms connected with renal disease; comatose form of pernicious intermittent; diabetic coma; sunstroke; hysteria, and various other forms of intracranial disease, especially meningitis; concussion and compression of the brain, which often involve hemorrhage; the apoplectiform attacks of intracranial syphilis and of general paralysis, as well as the congestive attacks (coup de sang, rush of blood to the head).

The first of these distinctions is, in a practical point of view, among the most important and often the most difficult, so that distinguished authorities insist not only on the difficulty, but impossibility, of making a positive diagnosis in every case. The physician who is most familiar with all the different conditions which may cause coma is least likely to jump at a conclusion.

Persons are constantly being picked up in the street partially or wholly unconscious, or found alone in a room without history and away from friends. The physician must then form his opinion from the present condition, which without a history may be very obscure, though with one it might present no difficulty. An empty laudanum- or whiskey-bottle may be of assistance, the former of much, but the latter of less. The smell of the breath may give a hint, but even if the smell of alcohol be detected, considering the widespread belief in its virtues as a panacea, it may be as well the result of amateur therapeutic attempts as an indication of the cause of the attack. Neither does it follow that because a man has been or is drunk he has no organic disease in his brain. Alcohol should simply make us more careful to examine for possible injuries. In regard to both these poisons—and in fact in the diagnosis of these conditions generally— the first thing to be sought for, after assuring one's self that the patient can breathe and is likely to do so for a few minutes, is some evidence of hemiplegia. This is not so easy as it might appear at first sight, since the general muscular relaxation may be so complete as to cover up local manifestations. The face, however, may show inequality in its lines or one cheek flap more loosely than the other.

The patient is not likely to undertake voluntary movements at the request of the physician, but he may make semi-voluntary ones if annoyed by the examination. The flaccidity of the arms may vary. Irregularity of the pupils is a piece of evidence to be received with some caution, as it may be habitual or the result of disease in the eye. Conjugate deviation of the eyes and head is a form of paralysis, or sometimes of unilateral spasm, which when present is of great significance. In opium-poisoning—and to a less extent in alcoholic coma—the pupils are much contracted, while they are not always so in apoplexy Respiration is usually much more rapid in apoplexy than in opium-poisoning, and this, in the absence of distinct signs of hemiplegia, would be one of the most important means of distinction. The pulse is more nearly normal in frequency, while that of opium is either slow and hard or more often frequent and feeble.

After the time for the initial depression has passed, rapidly-rising temperature is very strong evidence in favor of apoplexy. If the patient be only partially unconscious and able to protest against being handled, to make some short answers, or even be inclined to be combative, this is not to be taken as evidence of alcohol. Hemiplegia may then be noticed. This condition of excitement may be observed in the early stage of an apoplectic attack before it deepens into coma. Unfortunately, when the lesion is situated in certain portions of the brain, as in the extremities of either the frontal or occipital lobes, there may be no paralysis, but then also there is less likelihood of the extreme symptoms we are supposing to be present. In the cerebellum, however, the symptoms may be very severe without hemiplegia, and the diagnosis correspondingly difficult. Vomiting, not caused by the presence of large quantities of food or liquor, and persisting after the stomach is once emptied, would be of some value in this case, but it would often be necessary to wait for a diagnosis. Cerebellar hemorrhage is, however, a very rare accident, and cerebellar embolism sufficiently large to cause apoplectiform symptoms still more so. A limited lesion in the pons may cause gradually-increasing stupor without distinct paralysis.

Chloroform, especially if swallowed, and chloral might possibly give rise to difficulties in the way of diagnosis, and would have to be distinguished on the same general principles as alcohol and opium.

The poisonous gases arising from burning coal, consisting chiefly of carbonic oxide and dioxide, or illuminating gas, consisting of carburetted hydrogen with a little carbonic oxide, cause unconsciousness, coma, and sometimes convulsions and vomiting. In case of a person found unconscious in bed the possibility of poisoning by one of these should not be lost sight of, nor, on the contrary, assumed to be a cause without investigation. A case has been reported where, after acute poisoning by coal gas, there occurred, presumably as the result of local anæmia, alternate paralysis, convulsions, and aphasia.47 The new water-gas process is said to furnish a product considerably richer in the poisonous carbonic oxide than that now most in use.

47 Boston Med. and Surg. Journal, Nov. 26, 1885.

The stupor succeeding an epileptic convulsion resembles apoplexy, and the fact that cerebral hemorrhage may be accompanied by some convulsions increases the possible similarity, but it requires only a short time for epilepsy to make itself manifest, either by a renewal of the convulsions or a rapid recovery without paralysis. According to Trousseau, however, many attacks of so-called congestion of the brain are really epilepsy Puerperal eclampsia comes under the same head, but when convulsions are violent they may give rise to actual hemorrhage. Unilateral epileptiform convulsions are likely to be dependent on organic disease of the brain, usually not of the kind at present under consideration, but more frequently of a tumor.

Among the cerebral symptoms connected with renal disease, and not involving organic change in the brain, may be found unconsciousness, deep coma, and convulsions. It is obvious that the presence of a few hyaline casts and a little albumen will not decide the matter, since these may be present from many causes, and especially the changes in the circulation accompanying apoplexy.

Neither will the most indubitable evidence of Bright's disease, such as dropsy, hypertrophy of the heart, rigid arteries, with fatty and waxy casts in the urine, do so, for, as we have already seen, not only is there nothing in the presence of nephritis to exclude apoplexy, but the very form, the interstitial, which, from the supervention of coma not preceded by other very severe symptoms, most nearly counterfeits apoplexy, is also the most likely to give rise to actual cerebral hemorrhage. The extreme and frequent cephalalgia which is so distressing a symptom in cases where there is no cerebral lesion may also be the precursors of hemorrhage.

If we have a history, the gradual onset of the symptoms, deepening unconsciousness without any paralytic or unilateral symptoms, especially if accompanied by a diminution in the amount of urine or contained urea or a marked change in the character of the casts, renders it probable that we are dealing with so-called uræmia alone. In the absence of history hemiplegia must be the chief dependence, but it would not be difficult to imagine a case of embolism of the basilar artery with softening of the pons which would defy a positive diagnosis.

Pernicious intermittent fever appears in a so-called comatose form, which, if it were to be accompanied, as in a case related by Bemiss in the second volume of this work, by paralysis of one arm, might present difficulties of diagnosis. If it were known that the attack had been only of short duration, the elevation of temperature would, as in the case of sunstroke, decide in favor of the fever, but if it had lasted some hours, this symptom would be of no value, as the temperature may rise to an equal height in apoplexy.

Diabetic coma is a much less common affection than apoplexy. The peculiar odor (aceton) of the breath, if present—which is not always the case—might be diagnostic. The peculiar long and deep respirations would awaken suspicion which would be confirmed by an examination of the urine.

Sunstroke, with its sudden onset, complete unconsciousness, and rapidly rising temperature, may present a very close resemblance for

a while to apoplexy, and in fact has been known as heat apoplexy Age, temperature, and surroundings would give strong probabilities one way or the other, and if the temperature of the patient were at first below the normal and did not rise for an hour or two, it would certainly not be sunstroke and would be apoplexy, while if the temperature were very high a few minutes after the patient had been observed to cease work or become unconscious, the evidence in favor of sunstroke would be equally strong.

It might appear that hysteria need hardly enter into our consideration, and could hardly be mistaken for apoplexy, but most experienced physicians could relate instances where serious organic disease has been made light of under the name of hysteria, and many inexperienced ones could tell of the opposite and safer mistake. An occasional case of deep coma presents itself where, although the age and sex of the patient awaken strong suspicion, we cannot at once be sure that no organic lesion is present; and if, in addition, the patient should be affected with hemiplegia—a combination which, although rare, is by no means beyond the limits attainable by this perplexing disease—an immediate positive diagnosis would be difficult. Absence of facial paralysis, which might be made manifest by some irritation like pinching or an attempt to raise the eyelids, would be of much value under these circumstances. The hysterical physiognomy might be well enough marked to be almost conclusive by itself. The urine and feces are not likely to be passed involuntarily in hysteria, as they are in apoplexy.

Injuries to the head should be carefully looked for in any case with unknown history. Actual fracture, which perhaps leads to no depression of bone, may give rise to hemorrhage, probably meningeal, which will cause the usual symptoms, and a shock which is not accompanied by fracture may cause considerable laceration of the brain with consequent hemorrhage. In the latter case, however, unless the brain be already predisposed by arterial disease, the laceration and hemorrhage will not be extreme and the symptoms will be those of concussion. The diagnosis can hardly be said to be between hemorrhage and concussion, but whether the hemorrhage

be the result of concussion—a question which can hardly be answered without the history and observation of the further progress. Cuts and bruises may result from a fall caused by the shock, and pericranial ecchymoses may result from cerebral hemorrhage through the vaso-motor system without the intervention of accident.

Rapid meningitis of the vertex, with predominance of the effusion upon one side, may closely simulate compression from hemorrhage. At the base, by the time it has become severe enough to cause unconsciousness, it is likely to have affected the ocular muscles, and perhaps given rise to other paralyses less regular in their distribution than the ordinary hemiplegia. Ophthalmoscopic examination would be of value in these cases if—which is not very likely to happen— there is no history. The temperature in meningitis is more likely to be irregular and less rapidly and uniformly rising than in a severe hemorrhage or occlusion. In many cases emaciation, dry tongue, and constipation with sunken abdomen will testify to a previous illness, while after a few hours' observation the progress of the case will make the diagnosis more clear.

In differentiating cerebral hemorrhage or ordinary embolism from the apoplectiform attacks met with in syphilitic intracranial disease, it is rather a question of etiology than of diagnosis in the narrower sense, since unconsciousness and hemiplegia coming on with syphilis are often dependent upon a condition of the vessels closely resembling that which gives rise to the ordinary forms; that is, we are dealing in either case with an endarteritis which has furnished the basis for the deposit of a thrombus, and the question is, Of what nature is the endarteritis? It is obvious that this is only to be answered by a knowledge of the history, not necessarily of a primary or secondary lesion, but of previous disease. The syphilitic taint may often be suspected from the irregularity of the paralysis, the cranial nerves, for instance—especially the ocular—being much more frequently affected in syphilitic than in ordinary hemiplegia. After partial recovery or amendment the characteristics of irregularity and changeableness will be more strongly marked.

The pathology of hemiplegia and apoplectiform attacks, often transitory, in the course of general paralysis is not certain, but it is probable that they are due to sudden congestions of regions of some extent already in a condition of chronic periencephalitis or to cerebral œdema. The question of the existence of the previous disease can only be settled after the return of the patient to consciousness. Usually, these attacks are not of the severest kind, and are not necessarily attended with loss of consciousness, which, when it occurs, is usually not of long duration. An apoplectiform attack occurring in a young or middle-aged person who has neither cardiac nor renal disease, rapidly recovered from or changing its character, should awaken strong suspicions of either general paralysis or syphilis, or both.

The characteristic of the so-called congestion of the brain, or coup de sang, is a close resemblance to ordinary apoplexy, but without hemiplegia and usually with a rapid and complete recovery. A diagnosis from apoplexy cannot be made at once, except so far as hemiplegia can be shown to be either distinctly present or absent.

As has already been stated, the doctrine of the dependence of real apoplectiform attacks upon cerebral congestion alone has been vigorously combated by distinguished clinicians; and certainly the diagnosis of congestive (and the same may be stated even more strongly of so-called serous) apoplexy should never be made until after the rigorous exclusion of every other possibility.

After the severer apoplectic symptoms have passed off, and in cases where they have never been present, the diagnosis, so far as most of the conditions mentioned above is concerned, is divested of many of its difficulties when we are dealing with cases of well-marked hemiplegia. The chief points left are the distinctions from the apoplectiform attacks of general paralysis, cerebral syphilis, and cerebral tumor, which are to be made as already pointed out.

Slighter and more localized paralyses, such as may occur with limited lesion of the pons or where a hemorrhage having a large focus in the substance has escaped under the membranes and

presses on some cranial nerve, would present more difficulties. Paralyses which are very limited, and at the same time complete, are not likely to arise from hemorrhage or embolism, though it is possible that they may do so, but the diagnosis is to be considered rather under the head of local palsies than of cerebral disease. General rules cannot be laid down for slighter cases, and each case must be diagnosticated for itself. In many of them the electrical diagnosis would be of great value and often decisive.

Hysteria remains, as always, ready to counterfeit anything, but the following case shows that the error is not always on that side: F S

——, a young woman, was brought to the hospital, apparently conscious and understanding what was going on, but unable or unwilling to speak or to protrude her tongue. There was no history except that she had probably been in the same condition for thirty-six hours. There was paralysis of the right side, including the face, and marked anæsthesia of the same side, quite distinctly limited at the median line; temperature 97.8°, pulse 60, respiration 20. The next day she seemed perfectly conscious, but did not speak. The faradic brush to her face caused loud outcries, and the facial paralysis was diminished. This condition remained nearly the same, the patient appearing half conscious, but passing urine in bed. Four days later there was marked diminution of sensation and motion on the left (previously sound) side, as well as the right. The note two days later was, “Shuts and opens her eyes when told, and moves eyeballs in every direction, but there is apparently no voluntary motion except slight of the head. Incontinence of urine and feces.” A week later the temperature rose to 100.4°, pulse 140, and she died. The autopsy showed red adherent thrombus in the left carotid, extending into the cerebrals, with extensive anæmic necrosis of the cortex and a part of the corpus striatum. On the right there was a grayish thrombus and softening of the cortex, while the great ganglia were not affected.

A woman of thirty-two had repeated attacks of loss of consciousness and somnolence lasting several hours, but leaving her apparently well. The case was considered hysteria, but the patient died in a

similar attack. Degeneration of the cerebral arteries and hemorrhage were found.48

48 Christian, Centralblatt f. d. Med. Wiss., 1873, 864.

Post-paralytic chorea might present difficulties of diagnosis from hysteria or malingering, though the difficulty is quite as likely to be on the other side.

The diagnosis, however, is not complete until the lesion is located with some precision and its nature determined, although it must be confessed that when we have got as far as this the diagnosis in most cases is of more interest to the physician than to anybody else, except to a slight extent for prognosis, so that the event may be anticipated by a few hours. As to the localization of the lesion, recent experiments and observations, involving not only lesions of the kind we are here discussing, but tumors and injuries as well, permit this to be done with a reasonable degree of certainty. The general article on Cerebral Localization may be referred to by the reader for the minuter points, but certain groups of symptoms may be indicated here which are available to some extent before the complete return of the patient to consciousness.

In the vast majority of cases the lesion is situated upon the side of the brain opposite to the paralysis, except in some instances of cerebellar lesion, while in the peculiar form known as alternate paralysis due to lesion of the pons it is on the opposite side to the paralysis of the limbs and on the same side with the facial. It should be distinctly stated, however, that there are exceptions which are inexplicable on the present basis of cerebral anatomy. It is well known that only a part of the motor tracts cross to the other side of the cord at the decussation, and also that the proportion between the fibres which do and those which do not cross is a variable one. It has been suggested, in some cases of the kind mentioned, that all the motor fibres, instead of only a minority, as is usual, pass down on the same side of the cord as their origin. This has not been demonstrated. The number of such cases are so small that it need not be taken into account in diagnosis, and if the practitioner should