The Loyalist Conscience

Principled Opposition to the American Revolution

C HAIM M. ROSENBERG

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina

ISBN (print) 978-1-4766-7245-8

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4766-3248-3

Library of Congress cataloguing data are available

British Library cataloguing data are available

© 2018 Chaim M. Rosenberg. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: “A Tory and a patriot wrestle for a pine tree banner while a Native watches, 1776” (Library of Congress)

Manufactured in the United States of America

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Dawn

This page intentionally left blank

8.

Table of Contents

This page intentionally left blank

Preface

To sign, or not to sign? That is the question. Whether t’were better to be an honest man To sign, and so be safe; or to resolve, And, by retreating, shun them. To fly—I know Not where, and by that flight, t’escape Feather and tar, and thousand other ills

That loyalty is heir to.

—Frank Moore, 18601

All and every person [who does not take the American oath of allegiance will be] deemed adherents to the King of Great Britain, and treated as common enemies of the American states.—Proclamation of General George Washington, January 25, 1777

A Tory is a thing whose head is in England, its body in America, and its neck ought to be stretched.—Mark Lee Luther, 18992

“Your enemies talk much about your Tory connections,” John Jay warned Gouverneur Morris in 1776. “Take care, do not unnecessarily expose yourself to calumny, or perhaps indignity.” Gouverneur Morris’s brother Lewis was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but another brother, Staats, was a member of the British Parliament. Gouveneur’s mother was a devoted loyalist and his sister Isabella was married to the loyalist Isaac Wilkins. “I leave America and every endearing connection,” wrote Wilkins, “because I will not raise my hand against my sovereign, nor will I draw my sword against my country.” Despite his great contribution to the Revolution, Gouverneur Morris felt he was “censored, reproached, slandered, goaded by abuse, blackened by calumny and oppressed by public opinion.” Sir Egerton Leigh, the exiled attorney general of South Carolina, lamented that the Revolution respected “no law, no friendships, no alliance, no ties of blood.” Benjamin Franklin, the supreme patriot, separated from his son William, a committed loyalist. The Revolution, wrote John Adams, “seduced from my bosom three of the most intimate friends I ever had in my life.” President George Washington and members of his first cabinet, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox and Edmund Randolph all had strong connections with loyalists before the Revolutionary War.

The question became which side to support—the king or the American cause? William Smith of New York was known as the weathercock—keeping his choice to himself and hardly indicating which way he would turn. He spoke glowingly of America’s future

as an integral part of Britain’s empire. He advocated setting up an American government of all thirteen colonies, with the power to tax its people, under the control of the British king. His friends included prominent loyalists and patriots alike. Born in 1728, William was the son of the chief justice of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York. He was educated at Yale College and served on the Executive Council of New York. In 1757 he published the History of the Province of New York. In 1778 the patriots of New York declared him a traitor and placed his name on the list of the banished. On July 10, 1778, Smith wrote to his friend General Philip Schuyler:

I am banished for refusing an oath inconsistent with my conscience and my honor, and my views for the best interests of my countrymen. The penalties I am to endure had therefore no influence on my decision for I am determined not to disgrace those who have once honored me with their esteem by copying the example of Sir Toby Butlers, who held the profligate principle that he would rather trust God with his soul than the government with his estate.

I carry my innocence with me and leave my character with your protection. Ever, ever have I sought the felicity of my country. No abuse shall prompt me to injure her…. I am sorry that in the professed struggle for liberty the right of private judgment, its most sacred article, is invalid.

—William Smith

William Smith, Jr., was born in New York in 1728. The author of History of the Province of New York, he was declared a traitor. In 1783 he departed for England and three years later took up the position of chief justice of Lower Canada (Emmet Collection of New York Public Library, print number 419828. Image from the book by Maturin L. Deerfield, William Smith, Judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York, 1881).

Smith moved to New York City, where the British administration appointed him chief justice. In 1783 he went into exile in England. Three years later he moved to Quebec as chief justice of Lower Canada, a position he held until his death in 1793.3

“Loyalty to the crown was the normal condition of the American colonies before 1775.”4 The American colonists were linked to the mother country by laws, language, heritage, religion, education and even mode of dress. Borrowing the names of the opposing parties in the British Parliament, the Whigs (also called rebels or patriots) became the majority and the Tories (loyalists) the minority. After the Boston Tea Party and the Battles of Lexington and Concord, public sentiment against the king and the mother country rose dramatically. The patriots believed “that they were faced with a deliberate conspiracy” by the British government and their loyalist allies “to eliminate their freedom” and reduce them to slaves. 5 Once beloved as family, friends and neighbors, the loyalists were now shunned and vilified by the Rebels as coconspirators of the British and as enemies of American

liberty. The patriots justified their oppression because the loyalists refused to share “in the hazardous task of defending the liberties of our nation against the mighty power of Great Britain.” The loyalists strongly denied accusations of treachery. “You make the air resound with the cry of liberty but subject those who differ from you to the humble condition of slaves, not permitting us to act, or even think according to the dictates of conscience.”6 Beverley Robinson and Sir John Johnson were among the wealthiest and bestconnected men in colonial America. These ancestors of Thomas Hutchinson, Edward Winslow, Nathaniel Saltonstall and Ward Chipman arrived in the New World on the Mayflower or as passengers on John Winthrop’s fleet. Oliver De Lancey and Benjamin Faneuil were descendants of Huguenots who found sanctuary in America. Peter Van Schaack and Johannes Casparus Rubel were descended from the early Dutch colonists of New Amsterdam. For remaining loyal to the British king they lost their homes and property and their status in society and went into exile.

Over the past two centuries much has been written about the American loyalists— the great losers in the American Revolution. Major works include the British government’s 1783 account of the Claims of American Citizens. In 1847 Lorenzo Sabine published The American Loyalists. In 1890 Egerton Ryerson wrote The Loyalists of America and Their Times. In 1902 Charles H. Van Tyne issued The Loyalists of the American Revolution. In 1911 Wilbur Henry Siebert described the plight of loyalists in the American South and the West Indies. In 1912 James Henry Stark published an account titled The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution . In 1964 Paul H. Smith issued Loyalists and Redcoats. In 1973 Catherine S. Crary compiled her valuable The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era. In 1982 Phyllis R. Blakeley edited Eleven Exiles: Account of Loyalists of the American Revolution . In 2011 Maya Jasanoff issued her excellent account under the title Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. In 2015 Valerie H. McKito described the ordeal of a New York loyalist family in From Loyalists to Loyal Citizens. And in 2017 Holger Hoock’s Scars of Independence vividly described America’s violent beginnings.

The present study holds that loyalists, with some notable exceptions, were not enemies of the American people. Indeed, they were as devoted to America as the patriots, but held the differing opinion that Great Britain did not seek to enslave its American colonies but sought to protect and nurture them. By 1775 the Whigs (rebels) and the Tories (loyalists) were no longer two political parties vying for public support. The conflict had passed from tolerance and conciliation to the oppression of opponents. “There could not be loyalists until there were rebels.”7 A revolution needs enemies, both domestic and foreign. Unable to bridge the contradictory ideas of liberty and the equality of all men on the one hand with the slave trade and slavery on the other, the leaders of the Revolution assuaged their guilt over slavery by directing their hostility onto the loyalists. The label of loyalist became a mark of Cain, driving Tories out of the American family to seek sanctuary on the British side. The loyalist clergyman Samuel Seabury vowed not to yield to the rebel demands that he forsake his king: “If I must be enslaved, let it be by a king at least, and not by a parcel of lawless committee men.”

Declaring loyalty to the king caused great and lasting anguish, dividing families and friends. Loyalists who refused to recant were branded as enemies of the American cause— ostracized, harassed, subjected to double or triple taxes, kicked out of their jobs, thrown out of their homes, arrested, impoverished and banished from the country. The patriots deprived the loyalists and their families of their basic rights and liberties—the fundamental

tenets that drove the Revolution forward. To avoid persecution, most loyalists hid their allegiance to the crown and kept out of the battle to live quietly but in daily fear of being identified. Until the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781 loyalists still hoped for a British victory. After Yorktown, the “silent” majority of loyalists remained as humble citizens of the United States of America. By the close of the war 60,000 to 80,000 of them, including those who joined the loyalist militia, were expelled from their homeland.

The collective punishment of loyalists as “enemies of the people” was an overreaction born in the heat of battle and motivated by fear and hostility. The conflict ended with a clear victory for the patriots and defeat for the loyalist cause. The triumphant patriots gradually softened their urge to punish loyalists. The First and Fifth amendments to the Constitution recognized the excesses of arbitrary punishment of the loyalists during the Revolutionary era, and all citizens, including dissidents, were assured due process of the law and allowed to take their place in the affairs of the new republic.

Bernard Bailyn wrote, “A multitude of individual circumstances shaped the decisions that were made to remain loyal to England.”8 The lives of the loyalists and patriots were intertwined. All persons had their personal reasons for choosing one side of the conflict or the other. This work examines, at a personal level, how individuals swore allegiance either to the American cause or to the king of Great Britain. Their private letters and publications reveal the “individual circumstances” of high principle, conviction, determination, idealism, obstinacy, fear, recklessn ess, pride, self- interest or, occasionally, treachery. In this work I study the diaries, letters, writings and literature concerning George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, William Hooper, John Jay, Peter Van Schaack, Samuel Curwen, Joseph and Grace Galloway, and John Singleton Copley, among many others—the famous and the forgotten—to learn how each chose to be patriot or loyalist, and how that decision affected their lives, loves, friendships and place in history.

Introduction

For nearly a century and a half after their arrival in 1620 the colonists remained loyal British subjects. From the early days of settlement in North America, the British army and the British colonists fought wars together against Native American tribes, Holland, Spain and France. New Englanders developed a high level of literacy combined with a system of town government, selecting their own representatives. By 1760 the colonies largely governed themselves, albeit under the watchful eyes of the British-appointed colonial governors. The British colonies in America were tightly bound to the motherland by heritage, language, law, commerce and education. The colonists read British books and followed British fashions. The sons of the elite were sent to England to be educated. British educators taught in American colleges, and British clergymen preached in American churches. Tobacco, lumber, dried fish and other goods were sold to London trading companies that advanced credit.

In November 1747, admiral Charles Knowles of the Royal Navy docked his ship HMS Cornwall in Boston Harbor. After many of his men deserted, Knowles impressed dozens of Boston men as sailors, leading to a riot that lasted three days. The Seven Years’ War, fought from 1754 to 1763, spanned five continents (Winston Churchill called it the First World War).1 At the Battle of Plassey in 1757 Robert Clive conquered Bengal, permitting the rise of the British East India Company. Two years later, in Canada, the British Army with the help of American colonists, vanquished the French in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Britain won Canada, with 80,000 French-speaking Catholics and a vast territory extending from the Atlantic to the east bank of the Mississippi River. Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, addressed a long memorandum to King George III, laying out plans to extend British sovereignty into the interior of the American continent. “The great object of colonizing upon the continent of North America,” he wrote, “has been to improve and extend the commerce, navigation and manufactures of this kingdom, upon which its strength and security depend.” He proposed stationing British troops in the interior to lay “the foundation of lasting security to your Majesty’s empire in North America.”2 Benjamin Franklin claimed that before 1765 the colonist view of Great Britain was “the best in the world. [They] submitted willingly to the government of the crown [and showed] obedience to the acts of Parliament.” 3

The bonds to the mother country began to weaken after the French and Indian War and Britain’s attempts to tax the colonists. “No Taxation Without Representation” became their battle cry. The Stamp Act broke the trust between colonies and motherland: “No social or political phenomenon in the history of nations has been more remarkable than

the sudden transition of the great body of American colonists from a reverence and love of the monarchical institutions and of England … to a renunciation of these institutions and a hatred of England.”4 In reaction to the Stamp Act, mobs calling themselves Sons of Liberty “began to rob and pillage private homes.” Later these groups “took upon themselves full credit for having forced the British government to yield.” 5 As a result of the tensions of the Stamp Act of 1765, British America divided into two competing identities. The Tories (loyalists) remained conservative, hierarchical, and law-abiding, with a continued and deep allegiance to the king and his parliament and the conviction that safety lay under the umbrella of the motherland. The second identity (called Whigs, rebels or patriots) was the rejection of the status quo and resembled a rambunctious adolescent: argumentative, rebellious, and demanding independence. The Stamp Act still allowed diverse opinions, but the shedding of blood at the Battles of Lexington and Concord ended any chance for a peaceful resolution. By 1775 each and every colonist had to choose: either support American liberty or keep the colonies connected to the umbilical cord of Great Britain. The middle ground of fence sitting, equivocation or timidity no longer existed. The larger and more passionate patriotic forces gained the upper hand to impose their will and repress the speech and the values of the loyalists. The presence of loyalists in every village, town and city gave the rebels a ready target for their anxieties and anger. Those loyal to the king and motherland helped define the principles of the Revolution

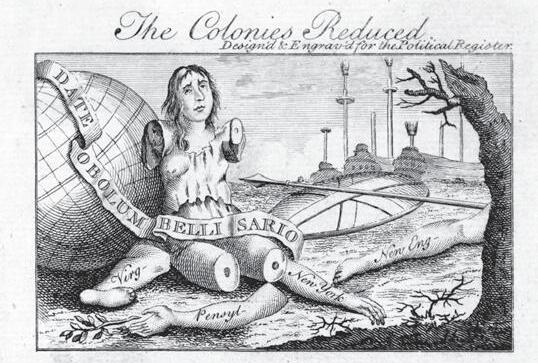

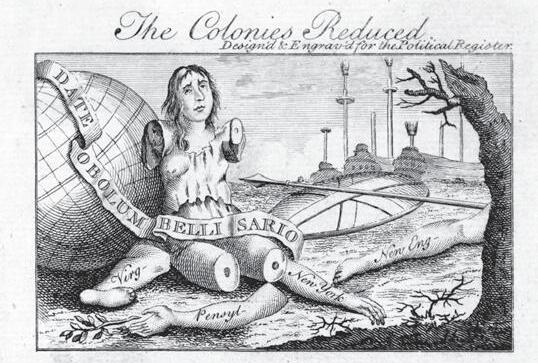

British cartoon dated 1767 shows the poverty of America after the Stamp Tax. Britannia lies dismembered, with arms and legs signifying Pennsylvania, New York, and New England scattered about. The phrase “Date Obolum Bellisario” on the banner can be translated “Give a penny to Belisarius” (one ell), a reference to Roman general Flavius Belisarius, conqueror of Africa, who was reduced to begging after he was accused of treason (Library of Congress, print LC-DIG-ppmsca-31019).

of liberty and independence. By even whispering an alternate view for America the loyalists were branded as enemies of people, singled out, ostracized, humiliated, deprived of their liberty, separated from their family and friends, and their property confiscated. Many of them were banished into exile. The rebellion stripped the loyalists of the freedom of thought and speech, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and the sanctity of private property the patriots were demanding for themselves.

Andrew Oliver was appointed Stamp Tax collector for Massachusetts. On August 14, 1765 a mob attacked his home and threatened his life. A few months later, at the Liberty Tree, Oliver resigned his appointment to the delight of the crowd (Emmet Collection, New York Public Library, 419872).

Liberty Tree. On August 14, 1765, a mob protesting the Stamp Act gathered under a large elm tree at the corner of Essex and Orange streets in Boston. They dubbed themselves the Sons of Liberty, and the tree became famous as the Liberty Tree. So began the rebellion against British rule. Events are depicted in an 1875 etching by Frederick A. Chapman, Raising of the Liberty Pole (Library of Congress, print LC-DIG-pga-02159).

Causes of Revolutions and Wars

Revolutions begin with rising discontent, wrote Gustave Le Bon in 1913: “As soon as discontent is generalized a party is formed … to struggle against the government. The great revolutions usually commenced from the top, not from the bottom; but once the people are unchained it is to the people that revolution owes its might…. A revolution is ripe when the people are persuaded that the government is the sole cause of all the trouble and that the new system [will be better].”Conflicts arise from deep-seated differences that prevent the combatants from understanding “the motives of one another’s conduct.” Each combatant believes that right is on his side but fears that the winner will become the sole arbiter of justice and will reduce the loser to perpetual slavery.Each side tries to win the neutrals to its cause. 6

Peter Oliver, William Gordon, David Ramsay and Charles Stedman wrote the earliest books about the American Revolution. Peter Oliver proudly traced his lineage to the earliest days of British settlement in the New World. Oliver owned extensive properties and a grand house replete with library, gardens and an orchard. His iron foundry provided a steady flow of wealth. Oliver socialized with the Belcher, Hutchinson, Bradstreet and Stoddard families—the Massachusetts aristocracy. Appointed in 1771 as chief justice of the Superior Court of Massachusetts Bay, Oliver loyally and devotedly served Massachusetts Bay Colony and the British Crown and was highly admired for his scholarship and skill. After 1765, observed Oliver, the mood of the province changed. The legislature of Massachusetts Bay, led by Samuel Adams, “hitherfore conservative, was now most radical in its opposition to everything that seemed to be encroaching on the part of the Crown upon the liberties of the people.” The legislature changed the salary and conditions of the justices. Oliver objected to these changes as “an insult to his dignity.” In response the legislature accused him of the “perversion of the law and justice,” claiming he was an enemy and had “detached himself from his connection with the people … and rendered himself totally disqualified any longer to hold the office of justice of the superior court.” Peter Oliver, once revered, was now insulted and hung in effigy. In 1774, because of his royalist ties, he was impeached and forced from his judgeship. No one came to his defense. On January 11, 1776, Peter Oliver published in the Massachusetts Gazette “An Address to the Soldiers of Massachusetts Bay who are now in Arms against the Laws of their Country,” warning that they were acting illegally and were in rebellion against the Crown by attempting to “throw off your allegiance to the most humane sovereign that ever swayed a scepter,” Great Britain being “the mildest government upon earth.” Oliver laid blame for the rebellion on Samuel Adams, John Hancock and John Adams, citing “the ambitious and desperate schemes [that] have plunged themselves into the bowels of the most wanton and unnatural rebellion that ever existed.” It is futile, Oliver warned, “to carry on a war [against] the power of Great Britain…. The vast expense of this civil war will be a burden too heavy for the shoulders of you or your posterity to bear. [These taxes] will press you down, never to raise more.” Oliver warned that the southern colonies would not support Massachusetts against Great Britain. “Return to your families and farms, do not follow your officers: beware of them, before it was too late.” For these opinions, Oliver’s house was burnt to the ground and he had to hide to avoid bodily attack. On Evacuation Day, March 17, 1776, the 63-year-old justice Peter Oliver sailed for Halifax and then for exile in England. His remaining assets in America were confiscated.7

In 1781, the year Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered his British army at Yorktown,

Left: Samuel Adams (1722–1803) helped establish committees of correspondence across the thirteen colonies to oppose British taxes and British rule. He saw loyalists as enemies who did “their utmost to discredit our alliance and hurt our cause.” Samuel Adams served (1794–1797) as fourth governor of Massachusetts (Library of Congress, print LC-USZ62-102271). Right: John Hancock (1737–1793) was one of Boston’s leading merchants. In 1768 the British seized his ship, Liberty, and accused him of smuggling. Hancock joined with Samuel Adams to lead the resistance against British rule. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress, his bold signature the first to grace the Declaration of Independence. Hancock served as the first and the third governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (Library of Congress, print LC-USZ62-55905).

Peter Oliver published his Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion , written from his perspective as an embittered loyalist-in-exile. By 1770, wrote Oliver in his book, “the fundamentals of government were subverted and every loyalist was obliged to submit or be swept away by the torrent. Protection was not afforded to them: this rendered their situation very disagreeable. [They were] at the mercy of the mob.” Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Hancock and their clique, in a grab for power, stirred up the populace against the Stamp Tax. The repeal by the British Parliament of the tax “gave the leaders proof of their power.” By vilifying the governor and the judges and by the malicious use of the press, Samuel Adams and Hancock, in order to destroy allegiance to the king and respect for and observance of the law, had unbridled the fury of the mob to tar and feather officials and threaten judges. The denial of a government appointment touched John Adams’s “pride and from that time, resentment drove him into every measure subversive of the law and of government.” Samuel Adams, wrote Oliver, “was a thorough Machiavellian [who] understood human nature in low life, so well, that he could turn the minds of the great vulgar, as well as the small, into any course that he might choose.” The state of anarchy created by these men allowed merchants to smuggle in goods and avoid paying taxes and unscrupulous politicians to gain power. Oliver mocked the patriots “for thinking they did God good service in persecuting and destroying all those who dared to be of a different opinion from them.” Congress had “duped the people” and had issued “charges of slavery so often in their ears that they are now reconciled to it.”8

Samuel Adams gave as good as he got.From the start of his agitation for American separation from Great Britain, he showed hostility toward the American loyalists: “The Tories will try their utmost to discredit our alliance and hurt our cause…. There are everywhere artful Tories enough to distract the minds of the people.” Adams warned against the “dangerous power of the Tories backed by wealth and position” and spread the idea that Tories were traitors and enemies of the American cause. Even after the Peace of Paris, he distrusted the Tories and voted against their return to America: “He still regarded them as enemies of his country, whose treachery and avarice had prolonged the war and aided the cause of the foreign invader.” 9

Born in Hitchin, England, in 1728, William Gordon was a clergyman who occupied a number of pulpits in England before coming to America in 1772. He settled in Boston as the pastor of the Third Congregational Church of Roxbury. During the Revolutionary War he wrote to General George Washington, asking for access to his official documents. At the end of the war, Gordon spent several weeks at Mount Vernon perusing Washington’s papers with the aim to write a history of the American War of Independence. A cantankerous man, Gordon fell out with his congregants and in 1786 returned to England, where he completed and published his six-volume The History of the Rise, Progress and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America.“The British ministry,” wrote Gordon, “have been greatly mistaken in supposing it is the same in America as in their own country.” The British are regimented according to class, status and money, while Americans are “individuals who are so independent of each other, that although there may be an inequality in rank and fortune, every one can act according to his own judgment.” The British Parliament had no right to impose taxes on the colonists without their consent. Americans were emboldened to seek independence following the defeat of the French. “The idea of a dangerous enemy upon the American continent was at an end.”10

David Ramsay wrote his two-volume The History of the American Revolution from the perspective of an American patriot. He was born in 1749 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. After he graduated from Princeton College in 1765, he attended the University of Pennsylvania to train as a physician, and in 1773 he moved to South Carolina to establish a medical practice in Charleston. Dr. Ramsay served, beginning in 1776, in the South Carolina legislature. With the surrender of the Continental Army and the British capture of Charleston in May 1780, Ramsay became a prisoner. Upon his release he determined he would write a history of the war, which was published in 1789. The grievances of the Americans began in 1750 with the realization that the policy of Great Britain was to exploit its colonies as sources of the raw materials (coffee, sugar, tobacco, indigo, timber, fish, cotton and grains) that were sent to Britain to be processed into manufactured goods. “The colonists,” wrote Ramsay, “were forbidden from transporting hats and home manufactured woolens, from one province to another.” These restrictions implied “that the colonists had not sense enough to discover their own interests” and served to “crush their native talents and keep them in a constant state of inferiority, without any hope of arriving at the advantages, which, by the native richness of their country, they were prompted to aspire.” Britain treated its colonies like dependent children, not permitting “the approach of the colonies to manhood.”

Entrepreneurial Americans built ships and recruited sailors to trade with the Caribbean islands and beyond. “The rulers of Great Britain were jealous of the adventurous commercial spirit” of the Americans, saw them as commercial rivals, and sought to

restrict their activities. These restrictions on trade forced the colonists to circumvent British rules by smuggling goods, trading directly with the French and Spanish, acquiring gold and silver, and by sailing to foreign ports. By 1764, wrote David Ramsay, the “colonies in the new world had advanced nearly to the magnitude of a nation.” The colonists “delighted in personal independence [and] a spirit of liberty.” Great Britain insisted “that her parliament was the supreme power.” The colonists, in turn claimed that “taxation and representation were inseparable, and that they could neither be free nor happy, if their prosperity could be taken from them without their consent.” Taxation without representation was an affront to the dignity of the Americans, who vented their anger on British- appointed governors, judges and customs officers. “There were in no part of America more determined Whigs than the opulent slaveholders in Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia,” wrote Ramsay. “The active and spirited parts of the community, who feel themselves possessed of talents that would raise them to eminence in a free government, longed for the establishment of an independent constitution.… The young, the ardent, the ambitious and the enterprising were mostly Whigs; but the phlegmatic, the timid, the interested, and those who wanted decision, in general, favoured Great Britain, or, at most, only lukewarm, inactive friends of independence.”11

The fourth of the early chroniclers of the American Revolution was Charles Stedman, born in 1753 in Philadelphia. Stedman was educated at the College of William and Mary. Like his father, he sided with the British and served under Lord Charles Cornwallis. During he war, he faced death as a rebel but escaped. At the end of the war he went into exile in England, where he wrote his two-volume History of the Origin, Progress and Termination of the American War , published in 1794.Despite his allegiance to the British king, Stedman understood the forces driving Americans to independence. “So natural is the love of liberty,” wrote Charles Stedman in 1794, “that it seems to be in the very nature of colonies … to seize every favourable opportunity of asserting their independence.” Before the Revolutionary War, Americans “were a people, not exceeding two millions of souls, widely scattered [and engaged in] the peaceful occupations of fishing, agriculture and commerce: divided into many distinct governments, differing from each other in manners, religion and interests; not entirely united in political sentiments; this people with very little money … was yet able to affect a final separation from Great Britain … the most formidable nation in the world.”

Before the Revolution most Americans were farmers or fishermen living in small communities. Merchants and professionals (lawyers, physicians, clergymen) comprised perhaps 15 percent of the population. Colonial America had eight colleges—Harvard, Yale, Brown, Dartmouth, King’s (Columbia), Queen’s (Rutgers), William and Mary, and the College of New Jersey (Princeton). Great Britain ordered its colonists to “share in the expense … necessary for their future protection.” By 1765 “the enterprising spirit of the inhabitants of the Northern colonies” of British America put them in competition with their British counterparts in trade. The Americans chaffed against the restrictions imposed on them by the British Parliament with “many of their principle merchants engaged in clandestine trade.” New England merchants broke the law by trading with Spanish and French Caribbean islands. Each new tax or seizure of an American ship and cargo increased “their chagrin, vexation and disappointment [and became] a fresh cause of discontent…. The displeasure and resentment of the people [against these restrictions] was directed against the officer who had done his duty, and not against the party who had offended against the law.” The mounting resentment led to “open revolt,” with custom

officials and civil servants harassed, stoned and humiliated by being tarred and feathered and paraded through the streets. The colonists were no longer “in a fit temper of mind to submit quietly to any further imposition on their commerce.” Instead “republican principles” were emerging as the colonists “looked upon themselves as the most competent judges of their own necessities, and considered the interference of the British parliament … as an unnecessary and wanton exertion of power.” 12 In his England in the Age of the American Revolution, written in 1930, the eminent historian Lewis Bernstein Namier portrayed Britain as a great trading country using its vast navy to import from its colonies raw cotton, sugar, tobacco, salt, saltpeter, timber, molasses and rice and exporting finished products at a profit.13 For the British, the colonies were a destination for slaves and convicts and a source of raw goods.

“Americans were not born free and democratic in any modern sense,” wrote Gordon S. Wood in his 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, “they became so—and largely as a consequence of the American Revolution.” In the epic struggle for self-determination and “to find new attachments befitting a republican people [based on] the commonplace behavior of ordinary people,” the Americans ended their allegiance to the mother country, the monarchy and the aristocracy. The Revolution “made the interests and prosperity of ordinary people—their pursuits of happiness—the goal of society and government…. One class did not overthrow another; the poor did not supplant the rich. But social relations—the way people were connected one to another—were changed and decisively so.”14 “The outbreak of the revolution was not the result of social discontent, or of economic disturbances within the colonies, or of rising misery.… The rebellion took place in a basically prosperous … economy,” wrote Bernard Bailyn. The revolution “grew out of inflamed sensibilities—exaggerated distrust and fear…. Only concerted resistance—violent resistance if necessary—could effectively oppose” the threat to American liberty. In this battle the loyalists were “outplayed, overtaken, bypassed.”15

Modern analysis stresses the economic factors that separated the American colonies from Great Britain. The American colonies were moving beyond mere sources of raw materials to developing their own banking and insurance systems, shipbuilding, and trade with Europe and the Caribbean. Merchants met the increasing demand for consumer goods. Molasses imported from the sugar islands was made into rum. The enterprise of New England merchants and manufacturers made New England a rival of the mother country and “put the region on a collision course with imperial interests.”16 “Without tens of thousands of ordinary people willing to set aside their work, homes and families to take up arms in expectation of killing and possibly being killed,” wrote T.H. Breen in 2010, “a handful of elite gentlemen arguing about political theory make a debating society, not a revolution.” The Revolution came from below, not from above. The writings of John Adams, Samuel Adams, John Hancock and others did not make the Revolution, Breen argues. Rather, the energy for the Revolution came from the ordinary people who “launched an insurgency that drove events toward a successful revolution. In the process American insurgents became American patriots.” Despite the “extraordinary popular rage,” the ordinary people and their committees “seldom sanctioned the use of physical violence as a political tool [but] struggled to observe rough forms of due process and judicial procedure.” Their anger was focused on loyalists, “whose principles and conduct [were judged] inimical to the liberties of this country.” 17

The twenty-four-year old diarist Nicholas Cresswell left England in 1774 for America

in search of adventure and opportunity. He kept a diary from the time he arrived in America until he left three years later. In Virginia, he wrote, “nothing but war is talked of, raising men and making every military preparation.” Great Britain sent its army across the Atlantic, but, wrote Cresswell, “this cannot be redressing grievances, it is open rebellion and I am convinced if Great Britain does not send more men here … they will declare independence.” The committee of safety had decreed that only those loyal to the American cause could be gainfully employed: “I am now in a disagreeable situation, if I enter any sort of business, I must be obliged to enter into the service of these rascals, and fight against my king and country, which my conscience abhors.”18 Short of money, Cresswell tried desperately to find loyalists who would protect him, give him food, lodging and work while he attempted to make his way to the British side. “I am suspected of being what they call a Tory (that is a friend of my country) and threatened with tar and feathers and imprisonment … curse the scoundrels.”19 Discussing the resolutions of the Continental Congress, Cresswell “was obliged to act the hypocrite and extol those proceedings as the wisest production of any assembly on earth, but in my heart, I despise them and look upon them with contempt…. It is very hard, I cannot write my real sentiments.”20

The patriots printed their own currency. The one-dollar bills carried the motto Dispressa resurgit (Though Oppressed It Rises). “I am a prisoner at large…. If I attempt to depart and don’t succeed, a prison must be my lot.” 21 Cresswell believed he was watched by spies.22 Congress “declared the thirteen united colonies free and independent states…. This cursed independence has given me great uneasiness.”23 Determined to escape to the British lines, Cresswell passed through Newark, New Jersey, to see the “ragged, dirty, sickly and ill-disciplined” American army. “If my countrymen are beaten by these ragamuffins I shall be much surprised.” 24 People were rude to him: “If you do not tactily submit to every insult … they immediately call you a Tory and think … they have the right to knock your brains out.”25 In 1777 Cresswell escaped to New York City and returned to England.26

“The most important and characteristic writing of the American Revolution” appeared in the form of pamphlets. 27 The writers appealed to the hearts and minds of Americans to take sides in the great debate: dependence or independence, slavery or liberty, the status quo or change. Up to the year 1776 some four hundred such pamphlets were written, and many more appeared while the war raged. Best known of the proindependence pamphlets are James Otis’s Rights of the British Colonies, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. The most prominent loyalist pamphlets were Samuel Seabury’s The Congress Canvassed, Myles Cooper’s A Friendly Address to All Reasonable Americans, Joseph Galloway’s A Plan of a Proposed Union Between Great Britain and the Colonies, and Daniel Leonard’s Massachusettensis. Entering the debate from England was Samuel Johnson, distinguished author of A Dictionary of the English Language and reigning colossus of English literature. In his 1775 Taxation No Tyranny Johnson poured scorn on America’s refusal to pay taxes and its quest for independence: “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” The American colonies “constitute[d] parts of the British Empire,” he said, and they were defended by Great Britain: “It is their duty to pay the cost of their own safety.”

After the Boston Tea Party and the fighting at Lexington and Concord, “the die was cast; the roll was called. Every American had to choose between remaining a British subject and being considered a traitor to America; or declaring himself a citizen of the

new-born nation…. There was no middle ground and no possible compromise. Many of those who tried to follow a neutral course were treated as enemies and harried out of the land [even though] they were Americans and proud of it.”28 A state of war existed between the conservative and the increasingly powerful radical factions: “The freedom of speech was suppressed and the liberty of the press destroyed.” Mob action and intimidation replaced discussion and compromise.29 In this incendiary atmosphere, Seabury, Cooper, Galloway, Leonard, and other loyalist pamphleteers were driven into exile, which stripped the dissent movement of its leaders. The enfeebled loyalists were reduced to complaining that patriots were “denying individuals the liberty of expression which did not coincide with their own views, and punishing dissenters.” 30

The core values of the American Revolution came largely from the English philosopher John Locke (born in 1632), which were presented in his 1680 book Second Treatise Concerning Civil Government. John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson read the book. Jefferson included Locke with Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton as being “the greatest men that ever lived, without any exceptions.” John Locke furnished Americans “with an arsenal of arguments against the arbitrary rule of both King and Parliament.”31 It is the nature of man, wrote Locke, “to preserve his property, that is, his life, liberty and estate,” against the efforts of others or the government to take them from him. Liberty permits each person to dispose of his “possessions and whole property [and] not be subject to the arbitrary will of another, but freely follow his own.” The role of government is to care for the common good of the people and to ensure their liberty and property are safe. “Whenever legislators endeavour to take away, or destroy the property of the people, or to reduce them to slavery under arbitrary power, they put themselves in a state of war with the people.”

Patriots were furious that the king and his parliament imposed taxes on the colonies without their representation or their consent. “The ministry could not have devised a more effective measure to unite the colonies,” observed Samuel Adams after learning of the passage of the Tea Act on May 10, 1773.32 Patriots accused the “mercenary and tyrannical” British Parliament of sending its troops to “destroy the liberties of America,” enslave the colonists, block their trade and progress, and impose military rule over them. The patriots believed they faced determined enemies, both the homespun loyalists and the troops sent by Great Britain. In the struggle, the colonies boycotted British imported goods, pushed aside British rule, established self-governance, and formed militia groups to defend themselves. Under the catchword of Liberty, the patriots swore an oath of allegiance to establish a free and independent United States of America and to defend these states against their enemies. In the words of Thomas Hutchinson, the rebel leaders planned to “irritate and inflame the mass of the people and dispose them to revolt.” 33 Patriots renounced any loyalty to George III or his government and declared war against loyalists, branding them traitors and “enemies of American liberty.” The time had come for the American colonies to fight for independence and freedom, establish their own laws, develop the economy, expand to the west, defend the borders and become the equal of Britain, Spain and France. They should establish their own literature, history, currency, heroes and villains—no longer dependent colonies but self-governing and strong and proud.

The British saw the rebellion differently. The first Continental Congress of 1774 appealed to George III and the British Parliament for “the right of the people to participate in their Legislative Council” and to ensure the right to “life, liberty and property.” In his

October 27, 1775, address to Parliament King George castigated Congress as a “desperate conspiracy [in which the colonists made] the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, whilst they were preparing for a general revolt.” A small group of agitators had “successfully laboured to inflame my people in America by gross misrepresentations, and to infuse into their minds a system of opinions repugnant to the true constitution of the colonies, and to their subordinate relation to Great Britain, now openly avow their revolt, hostility and rebellion.” The rebellion was “manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire.” Britain refused “to give up so many colonies which she had planned with great industry, nursed with great tenderness, encouraged with many commercial advantages, and protected and defended at much expense of blood and treasure.” The time had come to put down the rebellion and for “the re-establishment of order and tranquility.” 34

Ambrose Serle (1742–1812) served as private secretary to General William Howe, the commander in chief of British forces in the early years of the Revolutionary War. In his 1775 pamphlet Americans Against Liberty, Serle contrasts the orderly British administration with the “violent and republican spirit … of the furious and ungovernable multitude” determined to “shut up the courts of law … demolish the government,” and set up “an independent, arbitrary, democratic government of their own.” American patriots “have forced husbands from their wives [and] sons from their parents” to establish an army to fight the mother country. Showing “ingratitude to a parent,” Americans were destroying “all British constitutional liberties” to set up a tyrannical regime ruled by “audacious committees or an impudent mob” that would enslave rather than liberate the people.35

Liberty and Slavery

In 1752 the Pennsylvania provincial assembly received from London a large bell to “proclaim liberty throughout all the land.” The bell cracked soon after its arrival in Philadelphia. Dubbed the Liberty Bell, it was rung on July 8, 1776, at the public reading of the Declaration of Independence.

The first African slaves were brought to America in 1619. By 1776 every fifth person in British America was a slave. The percentage of slaves in the population was lowest in New England, 40 percent in Virginia, and 60 percent in South Carolina. In the French and Indian War, the colonists were grateful to Great Britain for protecting them against “Indian savages and French Papists, infamous the world over for treachery and tyranny.” Less than twenty years later the colonists felt they “were again in peril. The mother country, having saved them from the French, now herself threatened to reduce them to slavery through the devious method of parliamentary taxations.” 36 Freedom and slavery are “irreconcilable opposites,” yet they drove the Revolution forward. Edmund S. Morgan wrote, “The rise of liberty and equality in America had been accompanied by the rise in slavery…. Virginia plantation owners sought freedom from British rule partly to maintain the economic benefits of slavery.” The American colonists feared that Great Britain would snatch away their liberty and enslave them. The rebels and the loyalists differed widely in their perception of how Great Britain treated them. The rebels believed that the British were imposing taxes as a means to take their liberty and enslave them. The loyalists believed that Great Britain protected them and allowed them to prosper. Wealthy planters

and slave merchants of Virginia and the Carolinas were among the leaders of the American cause, claiming that British taxes would lead to the enslavement of the white colonists. Rebels and loyalists differed not a jot in how they exploited others. Both groups largely supported and benefited from the slave trade and slavery.

Opposition to slavery began before the Revolutionary War. John Woolman, born in 1720 into a New Jersey Quaker family, was an early exception and among the first to express his horror over slavery: “All nations are of one blood.” In 1746 he wrote Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes, first published eight years later. He stirred the consciences of colonists to end the slave trade and to free their slaves. Once free, the former slaves should be taught to read and write and to earn their own wages. Woolman’s anguished pleas were first directed at the Society of Friends then spread throughout the colonies. As early as 1760 Joseph Galloway warned the colonists against oppressive British policies: “You will become slaves indeed, in no respect different from the sooty Africans, whose persons and property are subject to the disposal of their tyrannical masters.” Writing in 1766, Anthony Benezet of Philadelphia noted, “The general rights and liberties of mankind, and the preservation of these valuable privileges … are become so much the subjects of universal consideration.” How can, he asked, “the advocates of liberty remain insensible and inattentive to the treatment of thousands and tens of thousands of our fellow- men, who, from motives of avarice … are at this very time kept in the most deplorable state of slavery? … It is impossible for the human heart to reflect upon the servitude of these dregs of mankind without some measure of feeling for their misery, which ends but with their death.”37

The Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, pastor of the West Church in Boston, came out as a bitter opponent of the Stamp Act. It was a “grievous oppression and scarcely better than outright tyranny.” British taxes “were an infraction of our civil rights and tending to reduce us to slavery.” The colonists were threatened with “perpetual bondage and slavery [and] obliged to labor and toil only for the benefit of others…. The fruit of [their] labor and industry may be lawfully taken from them without their consent, and they punished if they refuse to surrender it on demand.” Forced “by a distant legislature” to pay taxes and “not enjoy the fruits of their labor” placed the colonists in a state of slavery.38 Jonathan Mayhew’s participation in the rebellion was cut short by his death in July 1766 at age 48.

In December 1770 Thomas Cushing, speaker of the Massachusetts House of Assembly, shared his concerns with Benjamin Franklin. Cushing hoped that Great Britain would treat Americans as “fellow subjects” but feared their aim was “making us their vassals and slaves.”39 Edmund Pendleton, a wealthy planter was, with George Washington and Patrick Henry, a Virginia representative at the First Continental Congress. He questioned whether “the crisis in our fate in the present and unhappy contest [may soon] determine whether we shall be slaves [or have] freedom.”40 WilliamLivingston, appointed governor of New Jersey after the arrest of William Franklin, saw clearly the fallacy of espousing liberty while expanding slavery: “As early as July 1778, he flatly pronounced that to maintain negro slavery was inconsistent with Christianity, and particularly odious and disgusting in Americans, who professed to idolize liberty.”41

The American Revolution did not redistribute wealth or set free the slaves, let alone enfranchise men without property or any women, rich or poor. Leading patriots such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Edmund Pendleton and Henry Laurens were some of the wealthiest of the colonists and owners of many slaves. The rebellion was

driven forward by the colonists’ desire for liberty and their great fear of facing the same dismal fate as their own slaves. During the Revolutionary era “the white population worried that slaves would take advantage of political instability to revolt.” 42 Writing in his diary on September 15, 1775, John Adams feared that in Georgia and South Carolina “if a British commander landed one thousand regular troops [and] would proclaim freedom to all the negroes who would join his camp, twenty thousand would join in a fortnight.” A slave revolt could tilt the balance of the coming battle. “They say,” continued John Adams, “that all the king’s friends, and tools of government [in the South], have large plantations, and property in negroes; so that the slaves of the Tories would be lost, as well as those of the Whigs.”43 Adams esteemed liberty: “The hopes of liberty … conquers all discouragements, dangers and trials.” He denigrated slavery: “Consenting to slavery is a sacrilegious breach of trust, as offensive in the sight of God, as it is derogatory from our own honor or interest or happiness.”

On November 7, 1775, Lord Dunmore, colonial governor of Virginia, to boost the British forces issued his Emancipation Proclamation offering “all indentured servants, negroes and others free, that they are able and willing to bear arms, they joining his Majesty’s troops … for more speedily reducing this colony to a proper sense of duty to his Majesty’s crown and dignity.” This offer went only to the slaves of rebels but not to the slaves of loyalists. Virginia patriots responded to the proclamation by warning those “who desert their masters’ service … and conspire to rebellion or make insurrection, shall suffer death.” Despite this threat, many African slaves chose the offer of freedom by fleeing to the British side. “The threat of slaves attacking their masters had always been one of the darkest nightmares haunting the colonial imagination.” Newspapers in the South were full of news of the risk of arming slaves, “calculated to excite the fears of the people—massacres and instigated insurrections.”44 Dunmore’s proclamation to free the slaves convinced many Southern slave owners to back the patriot side in the battle. The fear that their slaves would run away and join the British “opened the way for the white ruling classes to use army enlistment [into the Continental Army] as an alternative means of control.” John Laurens, the son of Henry Laurens, South Carolina’s leading slave trader, believed that Americans “cannot contend with the good grace for liberty until we shall have enfranchised our slaves.” As George Washington’s aide-de-camp, John Laurens saw the war as the means to liberate the slaves. John asked his father, then president of the Continental Congress, to “cede me a number of your able bodied men slaves” to join the Continental Army. But the legislatures of Georgia and South Carolina refused to arm blacks, “using them instead as labor” for the army.45

With white manpower in short supply, recruiters on both sides took blacks—free or enslaved—as troops. “Approximately twenty thousand black slaves joined the British during the revolution.”46 Former slaves mainly did laboring but some formed militia regiments such as the Ethiopian Regiment and Black Pioneers to support the British during the Revolutionary War. In South Carolina, men who signed up to fight the British were promised payment in “slave labor and land out of property seized from loyalists.” These incentives encouraged “ordinary white men to fight not so much for independence, but for the continuation and expansion of slavery and for the chance to become slave owners themselves…. The vaunted American war of liberty was, in the South, a war to perpetuate slavery.”47 George Washington believed the British government intended “to fix the shackles of slavery upon us [and] reduce us to the most abject state of slavery that ever was designed for mankind.” 48 “I shall not undertake to say where the line between Great

Britain and the colonies should be drawn,” wrote George Washington to Bryan Fairfax on August 24, 1774, “but I am clearly of the opinion that one ought to be drawn, and our rights clearly ascertained…. But the crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition, that can be heaped upon us, till custom and use will make us tame and abject slaves, like the blacks we rule over with such an arbitrary sway.” 49 Soonafter writing these letters, George Washington left Virginia to attend the First Continental Congress.As Richard Brookhiser wrote, “Washington used the rhetoric of resistance to slavery regularly.”50

The first Continental Congress opposed the “ruinous system of policy administration” of the British parliament “evidently calculated for enslaving these colonies.” Following the 1774 Congress, committees of safety were set up in towns throughout the thirteen colonies to undermine colonial leaders and laws, and punish those who declared allegiance to the British king and parliament. North Carolina formed a supreme executive committee, overseeing six districts and 21 county councils of safety, to dismantle the colonial government and carry out the resolves of Congress. Since most Americans lived in small communities, these committees assumed the power to rule over their friends and neighbors. Offering £100 for the capture of Isaac Wilkins, the committee of safety vilified the meek clergyman as a “traitor … a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” and the agent of a British plan to make the colonists “abject slaves to the mercenary and tyrannical parliament of Great Britain.” Addressing the Virginia House of Burgesses on March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry, a major slave owner, uttered these famous words: “Give me liberty or give me death.” “Death is better than slavery,” wrote John Adams.51

The EnglishmanThomas Paine was 37 years old when he arrived in Philadelphia in 1774. He was so caught up in the fever of the rebellion that he wrote Common Sense: The chief task of an autocratic British king is to make wars that impoverish the nation; Britain keeps its American colonies dependent as part of its imperialistic scheme to dominate; with independence America would flourish “much more” and would form friendly ties with France and Spain, “against whom we have neither anger or complaint.” Paine fixed his anger on the loyalists. “These are times that try men’s souls,” he declared. “And what is a Tory? Good God. What is he? I should not be afraid to go to war with a hundred Whigs against a thousand Tories…. Every Tory is a coward, for a servile, slavish, selfinterested fear is the foundation of Toryism.” When a Tory “endeavors to bring his Toryism into practice, he becomes a traitor…. Either they or we must change our sentiments, or one or both must fail.”52 Thomas Paine’s pamphlet in favor of fighting for America’s independence was a great hit, selling a half-million copies.

Number and Characteristics of Loyalists

Loyalists did not believe Great Britain was intent on taking their liberty, let alone reducing them to slavery. Joined to the mother country by history, language, religion, customs, culture and values, loyalists trusted Great Britain. Loyalists were conservative and wished to keep, or gradually modify, the old system but remain loyal to the benevolent king and mother country. The colonies were too weak and too divided to govern or defend themselves. The colonies should remain subservient to the king who had the divine right to rule his subjects. The king and his Parliament knew what was best for the American colonies. Without the protection of Great Britain, the American colonies would

Patrick Henry (1736–1797) owned large tobacco plantations worked by many slaves. Speaking in the House of Burgesses, he was an opponent of the Stamp Act, declaring, “Give me liberty, or give me death.” A leader of the American Revolution, he served as the first and the sixth governor of Virginia (the image, from the collection of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-01711, is based on the 1851 painting by Peter F. Rothemel).

be financially and politically weak and vulnerable to attack by Indians, Spain or France. Loyalists saw themselves as subjects of the British Empire and supported the governors, judges, attorneys general and tax collectors chosen by London to rule over them.

Bernard Bailyn wrote in 2001 there “are no obvious external characteristics of the loyalist group” other than their allegiance to the Crown and they came from all walks of life: rich and poor, professionals and trades people. Patriotic chroniclers viewed “loyalists as the worst of the enemies, betrayers of their own people and homeland. [They were] the parasites of the worst corruptors of the ancien regime.” From the British perspective, loyalists were the “sensible embodiments of law and order … against which a deluded and hysterical mass, led by demagogues, threw themselves in a frenzy.”53 “At a fundamental level, loyalists and patriots alike thought of themselves as Americans.” Even the most outspoken against the Revolutionary cause—men such as Thomas Hutchinson and Peter Oliver—“felt themselves to be Americans and were proud of their American roots.” The difference was that loyalists preferred “to remain a part of the British Empire rather than become a separate country.”54

The ardor of the loyalists ranged from tepid to boiling. The British general William Howe suggested, “Some are loyal from principle; many from self-interest; also there are others who wish success to Great Britain from a recollection of the happiness they enjoyed under her goodwill.” Through “the workings of human nature,” rising nationalism demanded “the public humiliation of loyalists.” The beleaguered loyalists “trembled at the thought of being left to the rage of their countrymen.”55 In Massachusetts the patriot party “under determined and aggressive leadership … drove every Tory from office or compelled him to resign,” leaving only ardent “king worshippers” or those “so intimidated that they dare not express their Tory opinions … compelling them to remain silent or to espouse the popular side.”56 In an October 28, 1776, letter Christina Tice assured her Tory husband, “No rebel shall ever have the pleasure of knowing from my outward behavior my inward concerns.”57 Patriots went after the loyalists with a vengeance. During September 1775, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the rebel authorities “disarmed all those persons in the town called Tories, who would not declare their readiness to use their arms in the present contest in favor of the united colonies.” On May 1, 1776, the patriot Massachusetts General Court voted the Test Act, requiring all males aged sixteen and older to pledge to fight for freedom. Those who refused were denied the right to hold office or to practice their profession. Each person in the thirteen colonies faced the stark choice to openly support king and Parliament or to support the Revolution. “May it be the fate of every Tory scoundrel that now infests this once happy land,” one observer noted, “to make his exit out of America by the end of the month.” 58

How many loyalists were there at the start of the Revolution? The venerable John Adams suggested “one third of the whole population and more than one third of the principal people of America were thoroughly opposed to the Revolution.” Writing in 1813, Adams suggested that before 1775, in New York, Pennsylvania and the southern states, loyalists and patriots “were nearly equally divided.” In Virginia and New England— the most akin to Britain in heritage—patriots dominated and kept the other colonies “in awe.”59 New York, with large concentrations of people of Dutch and Huguenot ancestry, was largely loyalist.Christopher Hilbert estimated “perhaps a fifth, possibly a quarter of the population remained loyalist in sentiment.”60 Gordon S. Wood placed the loyalists at 20 percent of the white population. “The loyalists may have numbered close to half a million,” he wrote.61 Robert Calhoonestimated that “the proportion of adult white male

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

throng of money-getters, buyers, sellers, producers, contractors, speculators, and other zealots of utility, and thus elevate thee to the height of practical glory, thus make thee still more wondrous!

Such men thou wilt have, such men thy system must make; but to quote more eloquent words and thoughts than our own, “If we read history with any degree of thoughtfulness, we shall find that the checks and balances of profit and loss have never been the grand agents with men; that they have never been roused into deep, thorough, all-pervading efforts by any commutable prospect of profit and loss, for any visible finite object, but always for some invisible and infinite one.”

Ages, in which self-interest has been the one pervading principle, this world has seen before: such an age was that of Louis XV., only that then pleasure, not profit, was the prevailing object; lust, not mammon, the presiding deity. Such an era is being now enacted across the Atlantic. There self-interest, in the shape of mammon, is running its race boldly and fiercely, unstayed by old traditions, old memories, or old institutions, and is exhibiting to the world, in all its glory and success, the reign of the practical, the triumph of utility. Let thy admirers, followers, pupils, study these well, ere they rush on their onward career.

We, personally, stand aghast at thy offspring. They terrify us by their unripe shrewdness and “Smallweed” wisdom. Though verging on the period of the sere and yellow leaf, we ever loved the companionship of boys, and were considered rather a good fellow by them. We could discuss the shape of a bat, the colour of a fly, the merits of a pony, or the distinction of prison bar and prison base, pretty well, and at a push could even talk respectably of the stories of old Virgil, the marches of Xenophon, or the facetiæ of Horace. This was all well. But one does not now dare to touch one of these young prodigies without a fear that he will forthwith shoot an arrow from his quiver of facts and dates, by deliberately asking, how far Saturn is from the Earth, or at what rate sound travels, or what is the population of China, or the date of the Council of Nice.

Our flesh quakes even now, and a cold perspiration comes over us, at the thought of the intellectual contests we shall have to undergo with our firstborn. That child-man haunts us like a phantom. The vision sits upon us like a nightmare. We believe him to be our

lawfully-begotten offspring, but he will be thy child, O Age; child of thy nurture, of thy circumstances, thy influences. Thou wilt be the she-wolf who will suckle him! We see him grown formal, knowing, and conceited, battering us with questions from his catechisms, ’ologies, tables, and measures. We are not yet resolved how to meet this coming contest; whether to read up covertly for the emergency, or to follow an expedient once successfully adopted by a patriarch of our experience—that of affecting to despise and pooh-pooh all elementary knowledge as beneath and unworthy of him. Yes; we see this our offspring, and we know him chiefly by negatives, chiefly by contrast with boys of our own youth. We know that he will be more proper, discreet, and decorous than ourselves or our contemporaries. We know that he will not be misled by impulse or sympathy; that his mind will never be led from Euclid or Greek grammar, by the ringing of some old rhyme in his brain, or the memory of some old joke, or the thought of the green fields and green woods on which the sun is shining without; that his pulse will not beat quick at reading of the heroic three hundred at Thermopylæ; that he will perhaps vote the Horatii and Camillus humbugs; pronounce the Lay of the Last Minstrel an idle tale, and the Arabian Nights a collection of fooleries; that he will never believe in ghosts, and will smile scornfully at the mention of fairies and pixies; that he will never risk a flogging for the sake of Robinson Crusoe or Roderick Random; that Childe Harold and Don Juan, so sedulously kept from us, may safely be left within his reach; that he will never secrete the family tinderbox, or tear leaves from his father’s logbook to make bonfires on the 5th of November; that he will never give, except a quid pro quo; or play, except with a calculation of gain or loss. Will he ever know a boy’s love? Yes, perhaps, but he will pursue it calmly and discreetly, like a man and a gentleman; will approach his inamorata without diffidence, and talk to her without hesitation. Not such was our boy’s love; not thus did we go through that ordeal of beating pulse and rushing thought. To our recollection, we never spoke six words to the object of our adoration, and never entered her presence without blushing or stammering; but the sight of her flaxen curls and blue eyes at the window would set our brain in a whirl, and a smile or bob of the curls would cause such a beating of the heart that we forthwith set off at topmost speed, and were only stopped by loss of breath or wind. After all such interviews, the said curls and eyes, and certain

frilled trousers with which our deity was generally invested, would come dancing in on every mote and sunbeam, drawing off eye and thought from slate or book; and the memory of the many occasions on which we ate cane on account of such distractions, still causes a tingling in the regions devoted to flagellation.

Will he be a sportsman? Probably, but scientifically and unenthusiastically. We think not that he will ever mingle with his sport that love of wood and fell, stream and river, rock and waterfall, cloud and sunshine, leaf and spray, without which rod and gun would be to us as vain and idle implements. We know that he will never sleep in barn or outhouse to be early by the side of the stream or cover; that he will never invest pocket-money in flies, until their fitness for the season or stream has been well tested; that he will never, in anticipation of a raid on hare or rabbit, collect and lock up all the curs and mongrels in the neighbourhood, thereby delighting his parents by a midnight serenade. Will he delight in feasts and revelry? Yes; but staidly and soberly, dressed in fitting costume, conducting himself decorously, and talking on most proper topics. He will never, methinks, taste the luxury of banqueting on potatoes and sausages roasted in the cinders of a bonfire, or rejoice in the irregular joviality of harvest-home, village feast, or dancing in a barn. Wretch that we are! the shadows of such things cling lovingly to the skirts of our memory. One occasion we remember especially. It was the custom of our locale, that every village should have a day appointed for a feast, and on this all doors were opened, all friends welcomed from far and near. On such a day we crossed accidentally the threshold of a yeoman friend, and were dragged forthwith to a board literally groaning under the weight of a piece of beef of nameless form, a kid-pie made in a milk-pan, a plum-pudding ditto, with other delicacies of the like light kind. After trying our digestion, and working our wicked will on them, we adjourned to the barn, and there, claimed as a partner by a cherry-cheeked daughter of our host, we had to confront the struggle of a country-dance or jig, which or what we know not now, and knew not then. It was a fair trial to dance each other down. A bumpkin at our elbow looked on us with invidious rivalry, and commenced at once most outrageous operations with heel and toe. Our partner rushed recklessly on her fate. We felt misgivings as to our own powers. The limbs grew weak, the breath faint. We looked at the Cherry-cheeks; a few oily drops

were trickling down them. We felt encouraged. Presently the steps of our bumpkin fell more fitfully and irregularly. Again we looked at the Cherry-cheeks; the moisture was streaming down now in copious rivulets. Bumpkin at last went off in a convulsive fling, and Cherrycheeks, with a groan and a sigh, confessed herself beaten. We stood conqueror on the field. It was our first and last saltatory triumph. We have never before or since gained éclat in the mazy. Blush not for thy parent, child of our love, but throw thy mantle decently over his delinquencies! No such escapades will ever disturb the regular mechanism of the life which thou and thy comrades will lead!

Thus we trace him onwards by negatives from a youth without enthusiasm to a manhood without generosity or nobleness—a perfect machine, with the parts well adjusted and balanced, regulated to a certain power, fitted to work for certain ends by certain means—the end profit, the means the quickest and cheapest which can be found. As such a man, he will be a richer and shrewder one than his forefathers, and gain more distinction—perhaps become a railway director, have pieces of plate presented to him at public dinners, die a millionaire or a beggar, and be regarded hereafter, according to success, as a great man or a swindler. Such, O Age! is the distinction, and the reverse, which thou offerest to thy children!

Yes; so bigoted are we, that we would not exchange the memory of days spent on green banks, with the water rippling by and the bright sky above us—of nights passed with an old friend—of hours of loving commune with the gifted thoughts and gifted tongues of other days— the memory of the wild impulses, fervid thoughts, high hopes, bounding sympathies, and genial joys of our past—a past which we hope to carry on as an evergreen crown for our old age—even to play for such a high stake, and win.

We cannot test thee so well by old age, for the old men now standing in this generation are not wholly of thy begetting; but, judging by the law of consequences, we can foretell that material youth and material manhood must lead to a material old age; that souls long steeped in reekings from the presses of Profit, and bound for years in the chains of Utilitarianism, cannot readily escape from their pollution and bondage; and we can see also, even now, the dark shadow of the present passing over the spirits of men who began their career in a past. Old age is not, as of yore, a privileged period.

Men no longer recognise and value it as a distinction, nor aspire to it as to an order having certain dignities, privileges, and immunities, like the old men at Rome, who were granted exemption from the heavy burden of state duty, and served her by their home patriotism and counsel. Men love not now to be considered or to become old; they fight against this stage of life by devices and subterfuges, and strive to stave off or disguise its approaches. Nor are they so much to blame. The relations of age are changed; it holds not the same consideration or position as in former days, receives not reverence and deference as its due homage, nor is accorded by common consent an exemption from attack, a freedom of warning and counsel. The practical workers of to-day would as soon think of bowing to the hoary head or wise heart of a man past his labours, as to the remains of a decayed steam-engine or broken-down spinningjenny. The diseased faculties of old age are to them as the disjecta membra of worn-out mechanism. It is this non-estimation, this nonappreciation, which drives men to ignore and repudiate the signs and masks of a period which brings only disability and disqualification, and makes them cling by every falsehood, outward and inward, to the semblance of youth—very martyrs to sham and pretence.

It was not always thus. Within our own experience, men at a certain time of life assumed a change of dress, habits, and bearing— not relinquishing their vocations and amusements, but withdrawing quietly from the mêleé, and becoming quiet actors or spectators; thus signifying that they were no longer challengers or combatants, but rather judges and umpires in the great tussle of life. We remember with what respect we used to regard these as men set apart—a sort of lay priesthood—an everyday social house of peers—a higher court of council and appeal. How deeply we felt their rebukes and praises; with what reverence we received their oracles, whether as old sportsmen, old soldiers, old scholars, or old pastors. These men are becoming few, for such feeling in regard to them is dying out or extinct. Your young utilitarian would show no more mercy to a greyhaired veteran, than the barbarians did to the senatorial band of Rome, but would indifferently hurl Cocker at his head, or joust at him with his statics.

How many classes of these old men, familiar to this generation, are disappearing! We will not touch on the old gentleman, the old

yeoman, and others; their portraits have been drawn most truly already, and are impressed on most of our memories; but we must mourn over them with a filial sorrow, believing, O Age! that the high honour, dignity, worth, courage, and integrity by which they tempered society, were of more use to it than the artificial refinement, multiplied conveniences, rabid production, and forced knowledge which thou callest civilisation—that the moral virtues which they represented were more precious to a people, and more glorious to a nation, than the products and wonders of thy mechanism! If thou has bereft us of these, it will be hard to strike the balance!