AChicago Wanderer: Family, Friends, and Associates

Charles Richard Crane was born in a boarding house on the Chicago West Side in August 1858. His life encompassed the rise of the United States from a weak and divided nation on the eve of the Civil War to a world power in all respects by the time of his death at his winter home and date/citrus “garden” near Palm Springs, California, in February 1939, on the eve of another great war. He was a symbol of that American transformation from his modest origins as a son of the owner of a small brass foundry to a world traveler, businessman, politician, diplomat, and philanthropist.

Much of his rise to prominence owed to the success of his father’s business, Crane Company, which grew to be the largest manufacturer of plumbing fittings, valves, fixtures, and pipe in the world. Though receiving only fragments of formal higher education, Charles Crane would be honored for his achievements in various fields with five honorary doctoral degrees from prestigious universities: University of Chicago, Harvard, University of Virginia, University of Wisconsin, and the College of William and Mary. He had become an advisor to presidents and a devoted student of Russian life and history, and was fascinated with the culture, intrigues, and the economic and cultural possibilities of both the Far East and the Near East. As with many of his contemporaries, family background shaped his future in his involvement in a major business, in summer pastimes, an interest in world affairs, and a serious effort to promote international studies in America.

Charles Crane is unusual and distinctive in his generation for his interests in a variety of pursuits: exploration, philosophy, medical and natural science research, international studies, the promotion of universities and colleges at home and abroad, women’s education, local and national politics, settlement houses and civic institutions, and the progressive movement. Though he cannot be compared to a Carnegie, Ford, Mellon, or Rockefeller in the extent of his philanthropy, he was nonetheless the son of a self-made millionaire, who followed his father’s wishes to use his position and inheritance for “good causes.” Above all, he dedicated his life and resources to the advancement of the United States in world affairs through his association with world leaders, political causes, and the encouragement of American knowledge about less-known areas Russia, the Near East, and the Far East

Many of his pursuits depended on financial resources that were born to him and on his childhood surroundings and upbringing. His father, Richard Teller Crane (1832–1912), came from Paterson, New Jersey, to Chicago in 1855, owing to a relative’s success in the lumber business in the rapidly developing Middle West. The uncle, Martin Ryerson, also from Paterson, went west to Michigan Detroit, Muskegon, Grand Rapids in the 1830s as an Indian trader in fur and timber and by 1850 had established in Chicago a lumber and construction business that soon extended into

ownership of prime real estate.[1] Charles Crane’s grandfather Timothy, after working as a carpenter in New York City, had settled in Paterson as a builder and promoter of recreational parks. His major achievement was the erection of a ninety-foot truss suspension bridge over Passaic Falls, where he established a resort, especially popular for families on summer holidays. He even made his own fireworks for Independence Day celebrations.[2]

In 1827 Timothy Botchford Crane (1773–1846) married a much younger Maria Ryerson (1803–1853), an older sister of Martin, and they had four children: Franklin (1828), Jane Abigail (1829), Richard Teller, and Charles Squire (1834). Richard Teller Crane carried the name of his father’s first wife, Sarah Teller, with whom he had nine children between 1801 and 1827, about whom little is known.[3] Those by Maria had little formal schooling but apparently learned much at home and on the job “RT,” as he was later generally known, began working, barely in his teens, in a local textile mill and then in a tobacco processing factory, peddling the product from store to store in Paterson.

After the death of his father when he was only fourteen, another aunt, Jane Ryerson, found a job for him in Brooklyn at a brass foundry, where he learned the basics of casting molten metals, proudly produced a large brass bell on his own, while earning $2.50 a week and living in a boarding house that claimed most of his wages.[4] From that time on he would be enamored of the process of casting bells, an interest inherited by his son Charles. By 1850 Richard T. Crane was working in lower Manhattan as a machinist for Hoe & Company, a maker of printing presses, for $2.00 a day, but the depression of 1854 left him unemployed. His mother having died in 1853, he journeyed to Chicago in early 1855 with his last savings to seek Uncle Martin Ryerson, who was no doubt aware of his nephew’s mechanical training that could add another dimension to his lumber and construction enterprises in the rapidly growing Lake Michigan port and railroad center.[5]

R. T. Crane Brass and Bell Foundry, Chicago, c. 1858 (from Autobiography of R. T. Crane, Newberry Library)

With a loan of $1,000 from Ryerson, a considerable amount at the time, the “Richard T. Crane Brass and Bell Foundry” was established in a corner of the Ryerson lumberyard, where Crane lived in an unheated loft above the small factory

and employed sporadically up to seven workers.[6] As business grew, he summoned his younger brother Charles from Paterson and they built a larger plant, “Crane Brothers,” at 102 Lake Street (now no. 55 East Lake), that soon expanded to the next lot and double in space, producing steam heating pipe and brass fixtures and specializing in valves and cocks (faucets).[7] The company survived the 1857 financial panic by taking surplus pipe in payments and by winning an important contract ($6,000) for the steam heating of the Cook County Court House in 1858 and another for the Illinois State Penitentiary.[8]

The beginning of the Civil War brought an increased demand for metal workings —bits and braces for horses and scabbards for swords. By 1865 the Crane firm was meeting this demand while expanding its original production in yet a larger, four-story plant at 10 North Jefferson Street with the number of employees increasing to 700.[9] Brother Charles, while retaining a founding interest, left the business in 1872 to be involved in a variety of other ventures, but the business would retain the title of “Crane Bros. Manufacturing Company” for a time, later becoming simply “Crane Company.” It grew with other Chicago enterprises McCormick, Field, Armour, Swift with the city’s emergence as a major industrial and commercial center, and R. T. Crane, concerned with the downtrodden who were often new immigrants, became known as a liberal contributor to various charitable organizations, especially Jane Addams’s Hull House and the Chicago Commons Association and its technical and civic training school for indigent boys.

Owing to meeting two visiting sisters named Prentice from Lockport, New York, Crane married the eldest, Mary Josephine, in 1857.[10] The younger sister, Eliza, known by the future children as “Aunt Ide,” joined her sister in the Crane household to assist with childbirth and parenting, and, after a number of years of loyal service, succeeded her sister, who died of cancer in 1885, as his second wife, basically continuing her role as manager of the household until her death in 1907. At that time, Charles, the eldest son, persuaded his father to memorialize the first wife (his mother) with the donation of a building and a substantial endowment of around $100,000 to be added to the Hull House complex as a nursery school for poor children, an interest of both Prentice sisters.[11] As the “Mary Crane Nursery School,” this early Crane philanthropic enterprise, continues to serve families at four locations in the Greater Chicago area, under the management of the Mary Crane League, a non-profit corporation.[12]

To add to this large family, Richard Crane’s sister Jane (“Aunt Jennie”) also moved in to share the chores of child rearing. And for a period the Prentice sisters’ brother Leon would also live with them to lend a hand.[13] The head of this large household, for several years occupying a fifteen-room duplex rented from Ryerson on West Washington Boulevard, concentrated many long days on his expanding business, leaving the women the task of shepherding the family. Eight more children followed Charles in regular succession: Herbert (“Herbie” or “Bert”) Prentice Crane (1861–1943), who would be a long-time officer in the company but was never

seriously considered as a successor to its leadership; George Hamilton Crane (1862–1864); Katherine (“Kate”) Elizabeth Crane (1865–1949); Mary (“May”) Ryerson Crane (1866–1954); Frances (“Fan” or “Fannie”) Williams Crane (1869–1958); Emily (“Emmy”) Rockwell Crane (1871–1964); Richard (“Dickie”) Teller Crane II (1873–1931); and Harold Leon Crane (1875–1876).

Herbert married Harriet Doolittle (“Aunt Net”), a daughter of a company officer, and Katherine wed Adolph Frederick Gartz (1862–1930), a New Yorker, who became associated with Crane Company in 1890 and served many years as its treasurer; Frances in 1895 became the wife of University of Chicago zoologist and marine biologist Frank Lillie;[14] Emily was married for a few years to Chicago attorney Thomas Chadbourne before a divorce in 1905;[15] and Mary wed Edmund Russell, who was also an officer in the company. Richard Teller Crane’s expanded family and business enterprise had become essentially the “Crane Family Company.” To be sure, the eldest son Charles was never lacking for company—when at home. Perhaps his early long-distance travels were an excuse to escape from the responsibilities—as eldest son from both family and business responsibilities.

Katherine and Frances were clearly Charles Crane’s favorite siblings, perhaps because they were independent minded, developed liberal/radical political lifestyles, and were advocates of women’s rights, such as the right to vote. They were also bright, lively, entertaining, and vivacious a challenge to their favorite brother. Kate Crane Gartz was later known for her progressive activism in California where she dubbed herself “a parlor provocateur” and was a friend of the Upton Sinclairs.[16] Similarly, Frances Lillie created a stir in Chicago during the 1919 “red scare,” by publicly supporting a workers strike against Crane Company. And she was not afraid to be called a “radical”: “How did I become a radical? How did Tolstoy become a radical? By thinking, I suppose. Every thinking person must recognize the fact that there are inequalities and injustices in the present system of society.” She added that her emphasis was on the welfare of children and supported the strike for a shorter workday, so fathers could spend more time with their children.[17] The sisters certainly influenced their brother toward the American progressive political arena, though he had other motivations in that direction

Charles Crane’s youngest brother, Richard, graduated from Harvard (class of 1895) and married Florence Higinbotham, a daughter of Harlow Higinbotham, a prominent Chicago businessman, a partner of Marshall Field, and the president of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Although fifteen years younger than Charles, Richard Teller Crane II would succeed as director of the company in 1914 and enjoy the considerable profits owing to the continued success and expansion of the “plumbing fixture” company. He and his wife maintained a substantial residence in Chicago at 1550 Lake Shore Drive; a summer home, “The Castle,” on the North Atlantic shore of Massachusetts near Ipswich; and a winter refuge on Jekyll’s Island, Georgia.[18] They would have two children, Cornelius and Florence, who would both have interesting lives of their own.[19]

Sister Kate was involved in the company through her husband and son Adolph Frederick (“Bud”) Gartz Jr. (vice president) for her lifetime. Suffering the tragic loss of two young daughters in the Iroquois theater fire in 1903, she demonstrated the Crane trait of “soldiering on.” Moving in the 1920s to Altadena, California, when her husband retired, she promoted various social welfare causes through her substantial Crane Company shares after his death in 1930. The Gartz family continued the “Crane” presence at “Jerseyhurst” on Lake Geneva in Wisconsin through two more generations, and many of them are buried in the prominently marked Richard Teller Crane plot at Oak Hill cemetery in the town of Lake Geneva.[20]

According to the recollections of Frances Lillie, the first four Richard and Mary Crane children were mostly under the care of “Aunt Ide,” while the younger four were supervised by “Aunt Jennie,” in a calculated division of labor established by their father. Their mother was often ill, and there was little but homemade entertainment, one being a buggy pulled by a small horse that became a family pet.[21] She could not remember ever having a Christmas tree.[22] It seemed to have been a plain and simple but busy household that nurtured the upbringing of Charles Crane.

Though the Richard Teller Crane family was at first firmly Presbyterian from its New Jersey roots in Paterson and parishioners of the Third Presbyterian Church in Chicago, the restless head of the family steered it into the Congregational Church, before finally joining the “more fashionable” Trinity Episcopal Church. Descendants would follow this religious wanderlust, staying Episcopalian at St. Chrysostom’s, 1424 Dearborn,[23] converting to Roman Catholicism for example, Frances Lillie and Cornelia Smith Crane (Charles’s wife) or drifting toward agnosticism and/or mysticism with a consideration of other beliefs. The options thus presented may have influenced the eldest son’s openness toward Russian Orthodoxy, Hinduism, Buddhism, and, especially, the Muslim-Islamic world.

Still a “good willer” at heart, the elder Crane devoted his philanthropy close to home, especially to workers at his factory and management employees, no doubt a key to his business success. From the beginning of his Chicago enterprise, he provided five-cent lunches for his workers at the plant and by 1890 had a full-time physician at the factory to provide free primary care for employees and their families [24] Crane Company granted paid leave from work and expenses for all employees to attend the Chicago World’s Fair (Columbian Exposition) in 1893. He also sponsored regular summer outings for the workers and their families on the Fourth of July, as well as on other occasions, cultivating the image of a generous, yet paternalistic company.

Crane also prided himself on having an “open office” during workdays and for his special emphasis on good letter writing, a trait passed to his children. This is not to say that labor relations were always tranquil; during the Haymarket strife of 1886, Crane workers went on strike, as well as during other economic downturns, in protest of their wages being reduced. Nevertheless, his will provided a substantial endowment ($1,000,000) for worker pensions and stated that he wanted to have

done more for charity but bequeathed that obligation to his heirs, who, on the whole, carried it out.[25]

In the mid 1870s the family’s prosperity was recorded in a portrait by Theodore Pine, who lived with them for a few months in 1875 to sketch out the members. As the oldest son, Charles is depicted at the back and center, stern and adult (at age seventeen), towering over the others, a position his father no doubt expected of him with a Rocky Mountain scene in the background The painting was presented to Hull House, where it hung for many years until after the death of the senior Crane, when it was reclaimed by the Crane Company to honor its founder in the office of the company, with a copy replacing it at Hull House.[26]

As the oldest child, Charles Richard Crane is remembered warmly by a younger sister as studious, playful, athletic, but somewhat distant, and absent for long periods. He spent time with books and seemed destined for a scientific or medical career, acquiring a skeleton and a microscope and constantly dissecting insects and small creatures,[27] except for the fact that his father was grooming him in his own image as a skilled mechanic who would learn on the job and be his successor. Consequently, the young Crane spent many hours of his youth observing and participating in the actual processes of making things out of metal and assembling them into fixtures and machines. He also had time to engage in a young men’s club, along with his cousin and closest friend, Martin A. Ryerson, as charter members of the Everett Literary Society that was active from 1872 to 1880.[28]

The Richard Teller Crane Family (photograph of portrait by Theodore Pine, Chicago History Museum)

CRANE COMPANY

The plumbing fixture business benefitted considerably from the Great Fire of Chicago in 1871, having survived it intact while achieving public recognition by donating large engines to pump water from the Chicago River to fight the fire; it then fostered the rebuilding of the city, which happened to coincide with the large-scale introduction of indoor plumbing and steam heating, and the company boldly expanded into the associated manufacture of elevators for the taller buildings.[29] It was in this latter “sideline” that Charles Crane was officially inaugurated into the business, building an entire steam-powered elevator from scratch for a Detroit hotel, still in service in the 1930s. Much of his early education was on the job at the factory from age ten, working and observing ten hours a day for five years, according to his memoirs, probably an exaggeration.[30] He proudly informed his wife-to-be in 1877 that he was now in charge of the brass foundry, the foundation stone of the Crane enterprise.[31]

Clearly, Richard Teller Crane and his company, after very modest beginnings, were positioned on the cutting edge of major business growth from the rapid expansion of urban population and construction residences, business offices, and factories. Indoor plumbing, steam radiators, and elevators for multifloor buildings for passengers and freight after 1870 escalated its business, doubling the size of the “works” in a few years. And by diligence and care he made the most of new opportunities, and, with particular forethought, he discounted the sale of bulk facilities for public restrooms that were installed in many county courthouses across the Midwest, which also served as advertising. The business prospered even through major economic downturns to become the world’s largest manufacturer of valves, pipes, and fixtures associated with any kind of water movement involved in construction from homes and apartments to business and public facilities. In 1895, however, Richard Teller Crane decided to concentrate on fixtures and pipe and sold the elevator business to the Otis Company.[32] His son was disappointed by this decision, since he was proud of his early introduction into that part of the business.

The company’s success led to the purchase of the Bridgeport, Connecticut, factory of Eaton, Cole, and Burnham, expanded and embellished by exterior designs by Chicago architect Louis Sullivan in 1903, the whole negotiation supervised by Charles Crane.[33] This major expansion also resulted in another new factory in Birmingham, Alabama. To no surprise, additional Crane subsidiary plants would be established in Chicago. By that time Crane had become a name as closely associated with “the second city” as those of Field, Palmer, Swift, McCormick, Pullman, and Armour. Its success would naturally shape the career and future activities of the oldest son, who served a number of years as vice president (de facto executive vice president) and succeeded his father as president upon his death in 1912. Charles Crane’s exposure to the workplace, however, would be interrupted, and displaced, by other interests, especially travel.

Even after company leadership was transferred to the younger brother in 1914,

Charles Crane would continue to be associated with the company and especially in its Russian enterprise for a number of years. A 1921 company catalogue of almost 1,000 pages illustrates Crane Company’s scope and movement into the public restroom domain.[34] By that time the central plant in Chicago occupied 150 acres with 50 buildings and a secondary plant at Bridgeport of about half that size. It had about a hundred distribution centers in the United States and over forty sales offices in such cities as Fort Wayne, Indiana; Fresno, California; Madison, Wisconsin; Portland, Maine; and Topeka, Kansas.[35] The company remained under family control after the death of its founder until the 1950s, when the majority ownership of stock and bonds passed to new owners who continued the name and central manufacturing focus, though installing a bird (crane) as a symbol.[36] The original founder, Richard Teller Crane Sr , clearly ranks among the elite of successful entrepreneurs of the golden age of American enterprise, along with Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford, Deere, Westinghouse, Edison, McCormick, Chrysler, Wright, Singer, and others.

CHICAGO AND LAKE GENEVA RESIDENCES

By the late 1870s the growing Crane family would move to more substantial homes on Washington Boulevard,[37] before moving to a more impressive residence at 2541 South Michigan Avenue with the eldest son soon installed nearby (2559). These residences (none surviving) became centers of Chicago social life by the 1890s, especially during the Chicago World’s Fair.[38]

Lake Geneva in southern Wisconsin became a Crane summer living and social center, first by the enrollment of three daughters at the Lake Geneva (Ogontz) Seminary in 1878–1880.[39] After a preliminary visit during the summer of 1879, Richard Teller Crane erected a summer home on the north shore, which was in its early stages of becoming a popular destination for the Chicago elite [40] The Crane compound soon grew to four large summer houses at “Jerseyhurst,” the name derived from the family’s New Jersey origins: for the senior Crane (Jerseyhurst, 1880), Herbert (“El Nido,” 1887), Kate and Adolf Gartz (“Glen Mary,” 1887), and Charles and Cornelia (“Cloverbank,” 1889).[41] The houses were commodious Victorian style homes with wide verandas. The first and largest, Jerseyhurst, was designed by Chicago architect, Henry Lord Gay, who also had a home on the lake.

The Cranes were among the first of several prominent Chicago families to establish summer homes on this unusual crystalline glacier-made lake Others that followed included “cousin” Martin A. Ryerson (“Bonnie Brae,” 1881)[42] and Charles L. Hutchinson (“Wychwood,” 1901). More important, Lake Geneva is where Charles Crane learned to sail and to relish water recreation as well as summertime entertainments, such as golf.[43] Since the railroad depot for the Chicago & Northwestern trains in the town of Lake Geneva was several miles by road from Jerseyhurst, and the country club and golf course were on the other side of the lake, the Cranes soon had a steam boat on the lake, appropriately named The Passaic

honoring the connection with New Jersey to carry family and friends to and from their homes and for outings on the lake. The first Passaic was made of wood by the Napper Boat Shop and fitted by Herbert Crane with a steam engine from the Crane plant in Chicago; after its launch in 1880, it served the family for twenty-two years, then passed into other hands until broken up around 1925.[44]

A second, larger steamboat, also named Passaic, built by the Racine Boat Company, replaced it in 1902 Plated with quarter-inch steel and eighty-seven feet long, it competed with a number of other crafts on the lake, such as those of Ryerson and Wrigley, in durability and size. It provided transportation for family and company occasions, such as the seventy-fifth anniversary celebration of Crane Company at the lake in 1930. It remains in service after over a hundred years as a symbol of that time and place, though renamed Matriarch and converted from steam to gasoline engine power.[45]

The now wealthy Richard Teller Crane also indulged in wintertime escapes from Chicago, focusing mainly on Pasadena, California, though occasionally also to Miami, sometimes both during the same year.[46] These “extended vacations” were usually limited to hotel or boarding house arrangements and included various members of the larger family. In 1871 he went abroad for the first time to an exhibition in Paris with “Uncle” Ryerson. A self-made entrepreneur with no formal education, the senior Crane developed a critical view of colleges and universities, which he publicized in privately printed diatribes aimed especially against Ivy League schools, who in his estimation pampered, wined and dined, and spoiled the elite youth of America into an alcoholic stupor, and, even worse, produced men of limited practical knowledge and value for the new age of practical technology of which he was a leading example.[47] This perspective, however, may have been inspired by his son Herbert’s brief experience as a student at Harvard. It corresponds to widespread criticism of the operation of America’s so-called elite institutions, reflected especially by Woodrow Wilson’s failed attempts as president of Princeton University to curb the dominance of exclusive eating and drinking clubs on that campus and his effort to establish college quadrangles open to all students to foster a more productive educational environment. [48]

The Passaic, Lake Geneva, launched 1902 (photograph 2010 by Mary Ann Saul)

R. T. Crane also stood out as a controversial figure in the Chicago business community A contemporary, Lucy Mitchell, described its leaders: “Armour and hams; Pullman and sleeping cars; Marshall Field and the department store; Potter Palmer and the hotel; R. T. Crane and plumbing, valves and elevators; Fairbanks and scales.” And she added, “As for R. T. Crane, he had nothing in common with anyone else I ever knew. R. T. as he was called was literally a law unto himself. I well remember the agitation when he burned his wife’s will.”[49] According to this source, he had deeded the Michigan Avenue house to his second wife (Eliza Prentice) for tax reasons, and she then left it in a will to her brothers, who tried to claim ownership, with the upset widower responding: “She was penniless when I married her. She knew perfectly well that I gave her the house only to lessen my taxes. She had no right to make a will. Of course, I burned it!”[50]

Equally controversial was his third marriage to a much younger Chicago socialite, Emily Sprague Hutchinson, who would have little association with his children.[51] She created a local scandal, shortly after his death, by her remarriage to P T A Junkin, known widely as her lover, and by her resolute continued occupation of the home on Michigan Avenue.[52] Emily Junkin, fortunately, retained no role in the operation or ownership of the company. “R.T.” made sure of that.

The senior Crane’s “opposition” to higher education no doubt contributed to his eldest son’s lack of it, but this is probably an exaggeration because of the stir his written and vocal pronouncements created. After all, Herbert attended Harvard for a time and the youngest son, Richard, would graduate from that university.[53] And he supported his daughter Frances’s successful pursuit of a medical degree at the University of Chicago, certainly rare for a woman at that time and she would marry

a professor from that institution with her father’s blessings. Charles took a special interest in his sisters’ higher education, insisting that Frances spend a year in Germany to learn the language thoroughly in preparation for a scientific career that he had wanted. Another important factor was that his mothers, the Prentice sisters, were clearly advocates of the cultivation of talents. Eliza Crane was fluent in French, which she demonstrated in letters written in that language in 1901, encouraged foreign language study of the children, and her sister left knowledgeable observations in a diary of the 1877 family trip to Europe.[54] Charles Crane also promoted the study of foreign languages to his sisters and children while expressing regret for his minimal formal study of them, though he would pick up bits and pieces by sporadic exposure to French, German, Italian, Russian, Czech, Chinese, Turkish, and Arabic.

EARLY TRAVELS

Charles Crane’s first long-distance trip away from Chicago and Lake Geneva was with his family for the centennial celebration of the declaration of American independence in 1876, when they stayed with relatives in West Philadelphia. The main purpose of the visit involved business, an exhibit of a Crane engine pump at the exposition, but the visit was clouded by the death of the youngest of the Crane siblings, still under a year old. Charles Crane was clearly affected by this and would often mention it in subsequent family gatherings.

Little is known about any influences that may have resulted from the young Crane’s exposure to America’s first “world’s fair.” The following year, suffering from some persistent health problems that involved the nervous system and digestion, he embarked at age nineteen on his first overseas voyage, boarding the Emerald Isle in New York in June for the British Isles. He was allowed to lodge in the wheelhouse and took turns steering. On the ship he met William F. Libbey, a recent college graduate, who he credits with guiding him around England, Scotland, and Ireland. In London he stayed at the Castle and Falcon, near The Strand, where he would return several times in the future, until it was demolished in 1925. By late July 1877 he was in Coventry, recounting a visit to Stratford and expecting to go on to Chester.[55] Libbey also tutored the inquisitive Crane in the culture, literature, and philosophy of the British Isles. Clearly, Crane found travel exciting and fascinating, an education on the road.

That fall he enrolled at the Stevens Institute, a leading institution for technical education in Hoboken, New Jersey, but his tenure was abbreviated. He withdrew with his father’s approval after only a week to join the family on another tour of Europe, sailing on 29 September on the Britannia (the largest steamship at the time) for Liverpool. Traveling with them in Great Britain, he was thrilled to be returning as a guide, and they continued on to the continent. He described his travels to his fiancée, Cornelia Smith, in New Jersey, from Madrid and Nice, and hinted to “Marty” that he might go on from Italy to Greece.[56] It is not clear whether he was with the family for one of its highlights, a dinner in Paris on 8 November 1877 with former president Ulysses S. Grant, who was on a world tour that would later include Russia.[57]

From the continent Charles Crane departed from Naples to the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, where he met Richard Burton, a “real Arabist,” returning through Palestine and Syria and reaching Smyrna in May.[58] He rejoined the family in Paris in June by way of Greece and Venice. He was clearly impressed by what he had seen and done in the Near East during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). Witnessing the oppressive Ottoman Empire close hand, he was decidedly on the Russian side. It can safely be said that Charles Crane, having just turned twenty, gained a priceless education during his ten months abroad. He had also become devoted to the pursuit of travel in general, and the “fever” of the Near East would stay with him for life.

In February 1879, after only a few months at home, he set off westward for Japan, going as far as San Francisco, where he was held up by unspecified medical problems and aborted the trip.[59] Back briefly in Chicago, he accepted an invitation from cousin “Marty,” then a student at Harvard, to attend the June Harvard-Yale boat race. On his way back to Chicago he stopped over in New York City. Wandering along the east side Manhattan docks, he happened upon the Venture, a small sailing vessel, about to embark for Java with a cargo of kerosene. The captain offered to take him along as company. After hastily assembling items for reading, such as the

The Young Charles Crane, c. age twenty (RMBL, Columbia University)

works of Herbert Spencer, eating, and drinking and obtaining his father’s permission Charles Crane departed New York on 26 June for a real travel adventure. He noted in his memoirs that after passing Montauk Point he did not see land for 110 days until reaching Christmas Island in the Pacific, where he celebrated his twenty-first birthday.[60]

This voyage was a rich experience, sharing duties with the captain, taking turns at the wheel, going aloft to set sail, directing the mixed nationality crew, and suffering through the heat and dead calm of the horse latitudes. The ship’s menu was limited to oatmeal, salt beef, baked beans, and canned corn. He credited the addition of a bottle of Guinness stout every night from the several cases he brought from New York with saving him from beri beri, which caused a few deaths among the crew. Arriving in Batavia (modern Jakarta) in mid-October, Crane wrote Marty: “Nowhere have I been so greatly impressed with the value of facts of even the most trivial observations as on the sea. It is wonderful, indeed, to see the enormous importance of these little things when colligated by a philosopher. Everything has its own significance. I can partially illustrate what I mean by taking up the color of water.” He added a long description of the voyage, citing the works of Matthew Fontaine Maury, original editions of his treatises on navigation happening to be on board.[61]

Besides Maury, the young Chicago seaman read the works of Spencer, to whose “Principles” he became a life-long adherent, the journals of Nathaniel Bowditch, and Wallace’s Malay Archipelago. Finally reaching the East Indies (Indonesia), Crane debarked from the Venture to spent a month in the nature gardens of the Buitenzorg Valley (Bogor), about forty miles south of Batavia; after three months on Java, he visited the famous volcano of Krakatoa, just four years before its famous eruption. He then toured India, visiting Calcutta and Agra, and went on to China, where he made the acquaintance of the American missionary family of John Malcolm Kerr in Shanghai before visiting Japan and finally sailing homeward in the late spring of 1880 across the Pacific, arriving in Chicago in March.[62]

Still not having enough of extended travels, Crane set forth from San Francisco in 1882 on the W. H. Dimond, a 350-ton brigantine that had delivered sugar to San Francisco from the Sandwich (Hawaiian) islands. He spent several weeks on the Big Island and Maui exploring volcanos and lava tunnels and formed an attachment to the Dimond, which remained in service on the same route until 1920.[63] For a young man from the Midwest, Charles Crane had already logged an impressive number of miles (and days) on the high seas. It is not clear why his father would allow these extended diversions and pay for them. Probably he believed that this was better than four years at Harvard, or perhaps he did not want him in his road in running the company? Later associate Walter Rogers may have summed it up correctly:

His father tolerated his gadding about because through his son he kept abreast of the world. The old man had little education and knew little outside his own line. His son’s wanderings were also tolerated because he had been sickly since youth. CRC never went to high school. All his knowledge was self-acquired. He

learned to speak good French, fair German, and quite a lot of Russian, which he picked up during his travels.[64]

In any event, his travels abroad would shape the rest of his life. He set a possible American passenger record in ocean crossings with an approximate count: Atlantic thirty-six, Pacific twelve, Indian four, not counting other bodies of water such as the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

Charles Crane’s travels also included the United States, and he was especially fond of the Rocky Mountains and the Southwest. He joined a group of Chicago businessmen on a tour sponsored by the Santa Fe Railroad in 1880 that went as far as Cimarron, New Mexico, and resulted in a recuperative delay of a couple of weeks, owing to an accidental shot from his own pistol that creased his skull, causing much bleeding and scars from powder burns.[65] But he was back on the rails again the next spring to Colorado, ascending Pike’s Peak on 26 May, returning again in July 1882, recording the climb to sister Fannie in raptured tones [66]

FRIENDS

Though he met many people on his travels, four American friends, apart from the immediate family, stand out for their inspiration and influence One was Martin Antoine Ryerson (1857–1932), the only son of Martin Ryerson, continuing the early RyersonCrane relationship through the second generation. Though the seniors Crane and Ryerson went their own ways after the successful expansion of Crane Company, their progeny continued to correspond and refer to each other as “cousins” in an endearing way.[67] Charles often noted that “Marty” was his best friend. The junior Ryerson, a few months older than Crane, was also an inveterate traveler, whose destinations included the Middle East and India but concentrated on Western Europe, where he would become one of the leading American collectors of European art, especially the works of prominent French impressionists (Claude Monet especially), but his interests also included a wide range that included Roman and Greek artifacts. Ryerson’s interests in art and culture shaped Crane’s own pursuits in those directions. They would also have a common concern with supporting higher educational institutions and museums. Another Ryerson influence on the young Crane may have been an ambiguity (or neutrality) in regard to established religion.[68]

The elder Martin Ryerson had left a legacy of service to the city he did much to construct Perhaps most remarkable is a tribute to the Native American forerunners of the region, with whom he had early close and friendly relations. As a tribute to the Ottawa tribe’s contributions to the Great Lakes region, he commissioned a bronze statue, The Alarm, by Philadelphia sculptor John Boyle, depicting a mature Indian chief, his squaw, a boy, and a dog, unveiled in Lincoln Park in May 1884.[69] He also left a considerable estate to his son, daughter, and widow valued at the time at over $3,000,000, as well as a number of valuable properties—and the son added in tribute to his father, a striking Egyptian style mausoleum, designed by Louis Sullivan, in

Graceland Cemetery.[70] Building on his inheritance and sound investments, Martin A. Ryerson, the son, would become arguably the most important single benefactor of the city of Chicago.[71]

Much of the junior Ryerson’s philanthropy was with the guidance of Charles L. Hutchinson, who was the founding president of the Art Institute of Chicago, and related to Ryerson’s wife.[72] Ryerson also contributed a substantial amount ($150,000), and was instrumental in gaining more, to match a million-dollar endowment from John D. Rockefeller, for the establishment of the University of Chicago in 1892 [73] He then served for over twenty years as the charter president of the university’s Board of Trustees, endowed the Ryerson Physical Laboratory, one of the initial buildings on the campus, and contributed to several endowed professorships.[74] In retrospect, the new university could have been named the “Rockefeller-Ryerson University.”

Martin A. Ryerson is best known for his contributions to the Art Institute of Chicago, which compete with those of other major American art collectors, such as Guggenheim, Getty, Mellon, and Whitney. Donating his purchases beginning in 1892 on a regular basis, he also left art valued conservatively at $7,000,000 to the Institute upon his death.[75] The gifts ranged widely from ancient to modern and to an impressively designed art research library. Perhaps the most significant of his contributions are Claude Monet’s Poplars at Giverny, Sunrise; The Blind Musician by John Goossens; a small, exquisite Leonardo Di Vinci; and Winslow Homer’s The Herring Net. [76] And he also contributed to the Field Museum and other institutions. For example, the Walker Museum at the University of Chicago received a valuable collection of over 200 pieces of Native American pottery and textiles in 1895 from Ryerson. This “cousin” of Crane’s, a graduate of Harvard, and successful Chicago realtor, investor, and promoter, clearly influenced Charles Crane toward world travel, judicious art collecting, and philanthropy.

Martin A. Ryerson (Chicago History Museum)

Years later, Charles Crane wrote a special tribute to Marty in a letter to his son at the State Department, in recommending him for a position on the American delegation to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919:

I believe it would be hard to find in all the United States one who could be of so much value at Paris just now as Martin A. Ryerson of Chicago. His earlier years were spent in France and he speaks French as well as he speaks English. He has a profound sympathetic understanding of the French people with whom he has been in contact all his life, visiting France almost yearly. . . . No one is more entirely trusted in Chicago in large matters requiring character, judgement and experience. A call for him to go to Paris now would give a feeling of vast comfort to all the people of the middle west and probably the whole country.[77]

In accepting a gift of an illuminated Chinese manuscript, Crane, concerned about its safekeeping, offered either to return it, or to “send it, as I have sent a number of other rare works, to the Ryerson Library at the Art Institute of Chicago.” He added, “Mr. Ryerson was a cousin of mine and my closest friend so that in a way this is a family institution. He had much to do with the building up of the Art Institute, finally concentrating on the beautiful library, unquestionably the finest in the country ”[78] Though not approaching the degree of commitment to the world of art as his

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

adventure, in answering some inquiries of Clinton concerning the manner of driving logs to mill:—

“Six years ago,” said he, “I was logging upon the head waters of the Penobscot. “We cut eight thousand logs; and about the last of April we started them downstream. It took two or three days to roll them all in, and by that time, some of those we started first were perhaps more than fifty miles down stream, while others had lodged within a hundred rods of us. So we divided into three gangs, one to descend by boats, and the others by land each side of the stream. Each man was provided with a pole, having a stout hook in the end, and with these we pushed off the logs, where ever we found they had lodged on the banks or rocks. The first few days, we made pretty good progress, having little to do but to roll in the logs, and set them afloat merrily down the river.”

“Did you camp at nights, as you do here?” inquired Clinton.

“Yes, we camped out, but we had nothing but little huts made of spruce boughs, where we ate and slept;—as I was saying,—all went on pretty easy at first, and some days we got over fifteen or twenty miles of ground. But by-and-by we came to a jam. Do you know what a jam is?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, when the river gets choked up with logs which have met with some obstruction, we call it a jam. Sometimes, a thousand logs will accumulate in this way, forming a sort of dam across the river, and interrupting the flow of the water And, oftentimes, all this is occasioned by a single log catching upon a projecting rock; and if that single log could be started, the whole mass would go down stream with a tremendous rush.”

“I should think that would be fine sport,” said Clinton.

“It’s all very fine to look at,” continued the logger; “but you wouldn’t think there was much sport about it, if you had to go out upon this immense raft, and loosen the logs, at the risk of being ground to atoms by them when they start.”

“Are people ever killed in that way?” inquired Clinton.

“Not very often; for none but the most experienced drivers are allowed to undertake such a delicate job; and they are always very cautious how they proceed. But let me go on with my story: the jam I was telling you about, happened to be in a rapid, rocky place, where the river passed through a narrow gorge. On each side were steep cliffs, more than sixty feet high, which almost hung over the water. The only way to reach the jam was to descend by a rope from one of these cliffs. This was so hazardous an undertaking, that we concluded to wait a day or two, to see if the choked up mass wouldn’t clear itself, by its own pressure, and thus save us all trouble and danger. But after waiting nearly two days, there were no signs of the jam’s breaking. We can generally tell when this is going to happen, by the swaying of the logs; but the mass was as firm and compact as ever; and it was evident that we must do something to start it. There was an old and very expert driver in our gang, who offered to descend to the jam, and see what could be done. So we rigged a sort of crane, and lowered him down from the cliff by means of a rope fastened around his body, under his arms. After he had looked around a little, he sung out to us that he had discovered the cause of the trouble. A few strokes of the axe in a certain place, he said, would start the jam; and he cautioned us to pull him up, gently, as soon as he should cry, ‘Pull!’ and also to be careful, and not jerk him against the precipice. He then began to hew into the log which was the cause of the jam. After he had worked a few minutes, the mass began to heave and sway, and he cried out, ‘Pull!’ As the spot where he had been chopping was near the centre of the stream, he started instantly towards the cliff, so that his rope should be perpendicular. But before he could put himself in the right position for being drawn up, the huge mass of logs rose up in a body, and then, with a crash, rolled away in every direction from under his feet. The scene was awful. Some of the logs plunged headlong down the rapids, with tremendous force; others leaped entirely out of the water, turning complete somersets, end over end; others were hurled crosswise upon each other, or dashed madly together by hundreds, or were twisted and twirled about, in a most fearful manner. At the first movement of the jam, our man was plunged into the water. For a moment, we were horror-struck, but we pulled away at the rope,

expecting to draw up only a mangled and lifeless body And we should have done so, had we been half a second later; for we had just raised the man out of the water, when a mass of seventy-foot logs swept by, directly under him, with force enough to have broken every bone in his body, had he been in their way. He suffered no harm but his ducking and fright. But I don’t believe he will ever forget that day’s adventure. So, my boy, you see it isn’t all sport, driving logs,—though some think this is the pleasantest part of a logger’s life.”

“How do you stop the logs, when they have gone as far as you want them to go?” inquired Clinton.

“They are stopped by great booms, built of logs, and bolted and chained together very strong. These booms are rigged across the river, so that the floating logs cannot pass them. The great boom at Old Town, near Bangor, where our drive brought up, that year, had over a million of logs in it, when we got down there, seven weeks after we started from the forests. The logs lay upon one another about ten feet deep, and extended back for miles. They belonged to hundreds of different men and companies, but as each had its own mark, there was no difficulty in sorting them out. The boom is opened at set times, to let out a portion of the logs, and then the river below is all alive with men and boys, in small boats, who grapple the logs as they float down, and form them into rafts, or tow them to the various mills on the river. Very few of the logs escape, unless too many are let out from the boom at once, or the river is swollen by a freshet, in which case they sometimes float off to sea and are lost. But all hands seem to be going to bed, and I guess we had better follow their example.”

Upon this, the old logger stretched himself upon the bed of faded leaves; and Clinton, who for some time had been his only listener, was soon in the same position.

CHAPTER XVII.

A TALK IN THE WOODS.

EARLY the next morning, Mr. Davenport and Clinton decided to start for home, as there were indications of an approaching change in the weather, which might render the roads very uncomfortable, if it did not compel them to prolong their stay at the loggers’ camp longer than would be agreeable. After a breakfast of hot bread and molasses, fried pork, and tea, Fanny was harnessed, and bidding farewell to their forest friends, they jumped into the sleigh, and set their faces towards Brookdale. As they were riding along the solitary road, Mr. Davenport asked Clinton if he thought he should like to be a logger.

“I don’t know but I should,” he replied; “there are a good many things about the business I should like. It makes them strong and healthy, and I guess they have good times in the camps, and on the rivers. It is quite a romantic life, too, and they seem to meet with a good many curious adventures.”

“The novelty and romance of it soon wear off,” replied Mr. Davenport. “These gone, do you think you should like the business well enough to follow it up year after year?”

“Why, no, I suppose I should get tired of it, being away from home so much of the time,” said Clinton.

“The work is very hard, too,” suggested his father.

“Yes, sir.”

“And the pay is not very great, in proportion.”

“Isn’t it?”

“It is, however, a very useful employment,” continued Mr. Davenport, “and there must be men to engage in it. It is an honorable employment, too, for all useful labor is honorable. But I

should not call it a very desirable employment. The logger not only has to labor very hard, but he must go far away from his home, and deprive himself of nearly every comfort of civilized life, and expose himself to many dangers. And for all this hardship and toil, he does not receive so much pay as many a mechanic earns in his shop, with half the effort.”

“Does not Mr. Preston make a great deal of money at logging?” inquired Clinton.

“I suppose he makes a fair business of it,” replied his father; “but he is a contractor, and employs a good many hands. I was speaking of the hired men, not of those who manage the business.”

“Is Mr. Jones a contractor?”

“No, he works by the month, and hard work he finds it, too, I fear.”

“Then why does he follow it?”

“Because he is obliged to. He has a family to support, and this is the only way by which he can provide for them. Should you like to know how it happened that he cannot make money by an easier and pleasanter method?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Clinton.

“When he and I were boys together,” continued Mr. Davenport, “his father was rich, but mine was poor. When I was nine years old, I was taken from school, and put out to work; but Henry Jones was not only kept at school, for many years after, but was not required to do any work, even in his leisure hours. He was well dressed, and had everything he wanted, and I can remember to this day how I used to envy him. I could not go to school even in winter, but had to work constantly, and earn my own living. When I was about fourteen years old, I engaged myself as an apprentice to a carpenter. I liked the work, and soon made pretty good progress. As I had the long winter evenings to myself, it occurred to me that I might make up for my lack of school privileges, by an improvement of those leisure hours. So I got some school books, and set myself to studying. Soon after I reached my sixteenth year, I offered myself as a candidate for schoolmaster in our town, and was accepted, for the winter term, my

master having agreed to release me for three months, as he usually had little business during that portion of the year. And I, the poor selftaught boy, was not only a school teacher, but Henry Jones, whose privileges I had so often envied, was one of my scholars! A very dull scholar he was, too, for he did not take the slightest interest in his studies. Before I had finished my term, he left school, against the wishes of his parents, having been fairly shamed out of it. He remained about home several months, doing nothing, until his father secured a situation for him in a merchant’s store in Portland; but when he made his appearance in the counting-room, the merchant found him so deficient in penmanship and arithmetic, that, after a week’s trial, he sent Henry back to his father, with the message that he would not answer. His failure discouraged him from attempting to do anything more. Instead of remedying the defects in his education, he refused to go to school any more, but spent his time principally in lounging about his father’s place of business, and in sauntering around the town. He was a perfect idler, and as his father continued to support and clothe him, he took no more thought for the morrow, than the pigs in our sty do, and I doubt whether he was half so valuable to the world as they are.

“But this state of things could not last for ever. His father had embarked very largely in the famous eastern land speculations, and when the crash came, he found himself ruined. And yet even then, Henry managed to hang upon him like a dead-weight for two or three years, sponging his living out of his father’s shattered fortunes. But after a while, his father died, and then Mr Jones had to shift for himself. But what was he fit for? It took him a great while to find out. He tried several lighter kinds of employment, but did not succeed. At length a man came along who was making up a gang of loggers, and despairing of any better employment, he engaged in that, and has continued at it ever since. He is with his family only four or five months in the year, and during that time he works hard, at farming, not for himself, but as a hired man.”

“I should think he would feel bad, when he thinks how he wasted his youth,” said Clinton.

“He does,” said Mr Davenport. “He is a worthy and industrious man now, but he cannot repair the errors of his boyhood. Had he worked half as hard when a youth as he has had to since, he would probably be under no necessity of laboring now. But then his parents were rich and indulgent, and he thought he should never be obliged to work. Whenever we meet, he always says, ‘O dear, what a fool I have been! If my father had only kicked me into the street when I was twelve years old, and left me to shirk for myself, I might have been something now.’ And I never see him, without thanking God that I was brought up to depend upon myself, from my boyhood.”

Fanny had now come to a long and steep hill, and Mr. Davenport and Clinton got out and walked up, to lighten her load. When they reached the top, the prospect was very extensive, and they stopped a few minutes, to enjoy the scene, and to rest the horse. While they were gazing around, Clinton discovered something moving on a distant hill, and cried out:—

“A deer! a deer! don’t you see it, father?—right over that great pine that stands all alone, there.”

Mr. Davenport soon discovered the object pointed out by Clinton, and said:—

“No, that can’t be a deer, Clinty,—it is too large. It is a moose, and a noble great one, too. I should like to have a shot at him, but he is too far off.”

“I didn’t know there were moose around in this part of the State,” said Clinton. “One of the loggers told me they hadn’t seen one this winter.”

“They are pretty scarce now in this section of the country,” said his father; “but now and then one is seen. That fellow has probably been pursued, and has strayed away from his yard.”

The moose continued in sight for several minutes. Its gait was a swift, regular trot, which no obstacle seemed to break. There was something noble in its bearing, and Clinton stood watching and admiring it, until it disappeared in the woods. He and his father then got into the sleigh, and drove on.

“The moose is a handsomer animal than I supposed,” said Clinton. “That one Mr. Preston brought home, two or three years ago, was a coarse, clumsy-looking fellow.”

“They always look so, seen at rest, and close to,” replied Mr. Davenport. “But when they are in motion, and at a distance, there is something quite majestic about them. They travel very fast, and they always go upon the trot. It makes no difference if they come to a fence or other obstruction five or six feet high,—they go right over it, without seeming to break their trot. I have been told that they will travel twenty miles an hour, which is almost as fast as our railroad trains average.”

“I have heard of their being harnessed into sleds—did you ever see it done?”

“No, but they are sometimes trained in this way, and they make very fleet teams. The reindeer, which are used to draw sleds in some parts of Europe, are not so strong or so fleet as our moose.”

“It is curious that their great antlers should come off every year,” said Clinton.

“Yes, and it is even more curious that such an enormous mass should grow out again in three or four months’ time. This is about the time of the year that their new antlers begin to sprout. I saw a pair, once, that weighed seventy pounds, and expanded over five feet to the outside of the tips. The moose must have a very strong neck, to carry this burden about upon his head. When the antlers are growing, they are quite soft and sensitive, and the moose is very careful not to injure them. This is one reason, I suppose, why they frequent the lakes and rivers in the summer and autumn, instead of roaming through the forests. At these seasons of the year, the hunter has only to conceal himself on the shore of some pond or lake, and he is pretty sure to fall in with them. But the best time to hunt them is in the winter or spring, when they are in their ‘yards,’ as they are called.”

“Did you ever see a moose-yard, father?”

“Yes, I saw one a good many years ago. A party of us went back into the forests on a hunting excursion, one spring, and as near as I can remember, it was in this very part of the country that we came across the yard. That was before the loggers came this way, and frightened away the moose. There were no roads, then, in this section, and we travelled on foot, on snow shoes, with our guns in our hands, and our provisions on our backs. Some hours before we discovered the yard, we knew we were near one, by the trees which had been barked by them in the fall. Having got upon the right track, we followed it up, as silently as possible, until we came to the yard. But the moose had heard or smelt us, and vacated their quarters before we reached them. The yard we found to be an open space of several acres, with paths running in every direction, all trodden hard; for the moose does not break fresh snow, when he can help it. Nearly all the trees in the vicinity were stripped of their bark, to the height of eight or ten feet, and the young and tender twigs were clipped off as smoothly as if it had been done by a knife. We could not tell how many moose had yarded here, but from the size and appearance of their quarters, we judged there must have been five or six. Sometimes they yard alone, but generally a male, female and two fawns are found together. But we did not stop many moments to examine their quarters. We soon found their track from the yard, but we could not tell from this how many there were, for they generally travel single file, the male going first, and the others stepping exactly into his tracks. We kept up the pursuit until night, without catching a sight of our game. We then built a camp of hemlock boughs, made up a good fire in front of it, ate our supper, and went to bed.

“We started again early the next morning, and had not gone much more than half a mile, before we found the place where the moose had spent the night. Some how or other, they can tell when their pursuers stop, and if tired, they improve the opportunity to rest. Having gone a little farther, the track divided into two, and our party concluded to do the same. After several hours’ pursuit, the gang with which I went came in sight of a moose. He was evidently pretty stiff, and we gained on him fast, as the thick crust on the snow, while it aided us, was a great inconvenience to him. Finding at last that he could not get away from us, he suddenly turned about, and stood

prepared to meet us. But we had no disposition to form a very close acquaintance with him. One blow with his fore feet, or one kick with his hind legs, would have killed the first man that approached him. But he would not leave his place to attack us, and so we had nothing to do but to lodge a bullet or two in his head, which quickly decided the contest. We took his hide, and as much of the meat as we could carry, and went back to meet our companions, who, we found, had followed up their trail all day without getting sight of any game. At night they gave up the chase, and returned to the place at which they had separated from us. That was my first and last moose hunt. On the whole, we were as successful as most hunting parties are, for the moose is a very shy animal, and it is difficult to approach within sight of it, without its taking alarm.”

Mr. Davenport had scarcely finished his moose story when Uncle Tim’s clearing appeared in sight. As a storm seemed to be gathering, which might last several days, he concluded to stop here only long enough for dinner, and then to push his way homeward. Uncle Tim and his wife and boys were glad to see him and Clinton, and they seemed quite disappointed when they found their guests were not going to stop over night. After an hour’s visit, the travellers resumed their journey, and arrived home early in the evening, without any remarkable adventure. The storm which Mr. Davenport anticipated, set in about dark, in the form of rain and sleet, and continued for two or three days. This kept Clinton in the house, much of the time, and gave him an opportunity to relate to his mother and Annie the various incidents of his excursion, which he did with great minuteness and fidelity.

CHAPTER XVIII.

WORK AND PLAY.

THE days were now perceptibly longer, and the sun had begun to make quite an impression on the huge snow-banks in which Brookdale had been nearly buried up all winter. “Bare ground,” that looks so pleasant to the boy in a northern climate, after a long winter, began to appear in little brown patches, in particularly sunny and sheltered spots. The ice upon the pond was still quite thick, but it was too soft and rough for skating. The sled runners cut in so deeply, that there was little fun in sliding down hill. Besides, skating and coasting had got to be old stories, and the boys were heartily tired of all their winter sports. The sleighing was about spoiled, the roads were sloppy, the fields and meadows impassable, and the woods uncomfortable. In fact, while all the outdoor amusements of winter were at an end, it was too early for the various summer games and sports that supply their places. This brief season, which usually attends the breaking up of winter in northern latitudes, is generally the dullest of all the year to boys in the country, unless they are so fortunate as to be able to amuse themselves indoors, a part of the time at least.

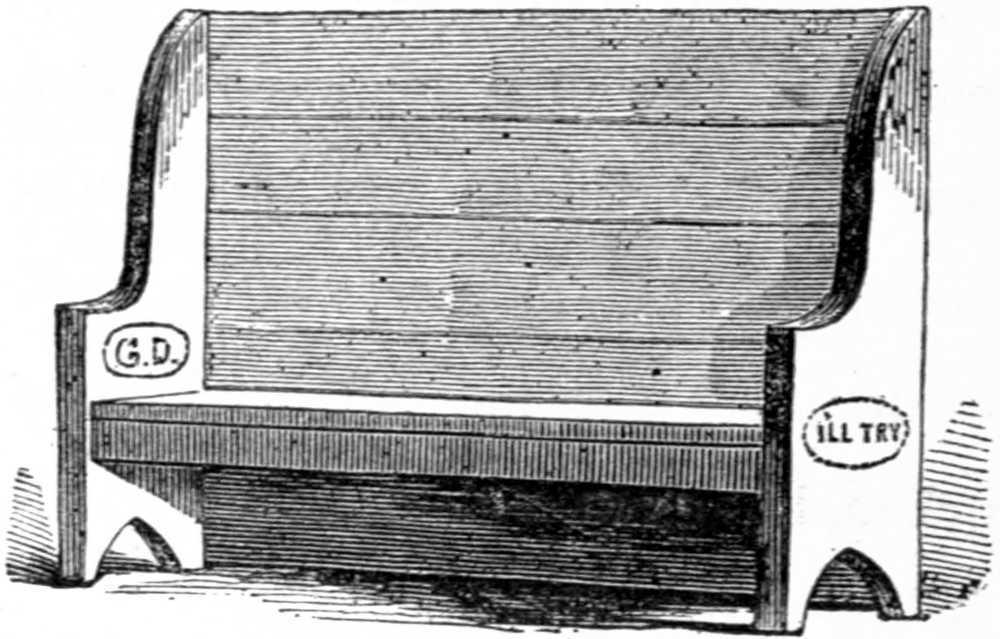

Clinton’s favorite place of resort, at such seasons, was the shop in the rear of the house. Here, surrounded with tools, and patterns, and plans, and specimens of his own work, and perhaps absorbed by some object upon which he was engaged, he was never at a loss for amusement. A day or two after his return from the logging camp, he went to work on the “settle,” which he had determined to make, in imitation of the one he had seen at Uncle Tim’s. This was a job that would require some little thinking and planning, as well as skill at handling tools,—for his mother had promised to give it a place in the kitchen, if it was well made,—and he felt anxious to do his best on this occasion. He first sawed out from a plank the two end pieces, rounding off one corner of each, in a sort of long scroll pattern.

Having planed these smooth, he next made the seat, which was also of stiff plank, and fastened it firmly in its place. Nothing remained to be done but to make the back, which was of boards, planed and matched, and screwed into the end pieces. In the course of a week the settle was finished; and it was not only neat and well-finished, but really substantial. It looked as though it might do service full as long as Uncle Tim’s. Clinton was quite satisfied with his success, and his mother was so well pleased with the settle, that she not only decided to place it in the kitchen, but promised to make a handsome cushion for it.

As Clinton was looking admiringly upon his piece of work, soon after it was finished, and thinking whether he could improve it in any respect, the conversation at Uncle Tim’s recurred to his mind, and a happy thought suggested itself, by which he might associate his settle with that interview, and thus have constantly before him a memorial of his trip to the loggers. The next time he had occasion to go to the store, he bought a small package of brass-headed tacks, and with these he carried out his new design, which was to inscribe his initials “C. D.” upon one end of the settle, and the motto, “I’�� T��,” upon the other. He had seen nails arranged in the form of letters upon trunks, and he found no difficulty in making his inscriptions look very well. He surrounded each of them by a single line of tacks, placed in the form of an oval, which gave the whole quite a finished look. This improvement elicited from his parents many additional compliments for the new article of furniture.

The snow was rapidly disappearing, and the sunny sides of the hills were quite bare. The welcome song of the robin was heard around the house, proclaiming the arrival of spring. The brook which flowed through Mr. Davenport’s land was swelled to a miniature torrent, and Clinton’s ducks,

—whose water privileges had been restricted through the winter to a small space kept clear of ice by an axe,—now sailed about in all their glory. The frost soon left the ground,—for it penetrates but slightly, when the earth is covered with snow all winter,—the moisture rapidly dried up, and the fields were ready for the plough. For a few weeks Clinton was employed, much of the time, in the various labors of the farm. He usually drove the ploughing team, but he sometimes turned the furrow, by way of change, while his father guided the oxen. Then came harrowing, manuring, planting, setting out trees, making beds in the kitchen-garden, and the various other farm operations of spring, in all of which Clinton assisted his father. He also attended to his own patch of ground, of which he had the sole care every year. As they were at work in the kitchen-garden one day, Mr. Davenport asked Clinton how he should like to take the whole charge of it for the season.

“Why, I should think I might take care of it, just as well as you, after it’s all planted,” replied Clinton.

“And should you be willing to assume all the trouble and responsibility?” inquired his father

“Yes, sir, I’ll take it and do the best I can,—only, I may want your advice sometimes.”

“Well, Clinty,” resumed his father, “I’ll make you an offer, and you may accept it or not, just as you please. After the garden is planted, I will surrender it entirely into your hands, and you shall do the best you can with it. You shall keep account of everything that is raised in it, and at the end of the season we will calculate the value of the various crops, and I will give you one-fourth of the whole sum, as your share of the profits. For instance, if the vegetables you raise come to twenty-five dollars, you shall have six dollars and a quarter for your services. If, by your good management and the aid of a favorable season, you raise forty dollars’ worth, you will receive ten dollars,—and so on in proportion.”

“I’ll do it, I’ll do it,”—said Clinton, eagerly.

“Wait a moment,” continued Mr Davenport,—“there are one or two conditions that must be plainly understood, before we close the bargain; one is, that you are not to neglect my work, for the sake of your own. I shall call on you, when I want your assistance in the field, just as I did last year, and you mustn’t think that what you do in your garden is to exempt you from all further labor. And you must understand, too, that if I find you are neglecting the garden at any time, I shall take it back into my own hands, and you will receive nothing for your labor. Do you agree to this?”

“Yes, sir; but you’ll allow me time enough to take care of the garden, wont you?”

“Certainly, you shall have time enough for that, besides some hours every day, to devote to study and play.”

“Well,” said Clinton, “I’ll agree to all that, and if the garden doesn’t do well, it shan’t be my fault.”

In a few days the garden was all planted. It was nearly an acre in extent, and was thickly sowed with vegetables, such as peas, beans, lettuce, radishes, turnips, cabbages, onions, early potatoes, sweet corn, cucumbers, squashes, melons, etc. Having done all that he was to do with it, Mr. Davenport now surrendered it into the keeping of Clinton. For a few weeks the garden required little care; but byand-by the weeds began to spring up, and the various insect tribes commenced their operations among the tender plants. Clinton now found plenty to do. He was wise enough, however, not let his work get behind hand; for had he suffered the bugs and weeds to get a few days’ start of him, I doubt whether he would have overtaken them. This was one secret of his success; another was, his perseverance,—for he generally carried through whatever he undertook, simply because he was determined to do so. Mr. Davenport was very well satisfied with the way he managed the garden; and to encourage him, he was careful not to call him away to other parts of the farm any more than was necessary

Clinton generally rode over to the post-office, at the Cross-Roads, every Saturday afternoon, to get the weekly newspapers to which his father was a subscriber. One pleasant afternoon, in May, he drove

over as usual, and as the mail had not arrived, he hitched Fanny to a post, and went away, a short distance, to where a group of small boys of his acquaintance were collected. They were earnestly and loudly discussing some point, and when they saw Clinton, one of them said:—

“There’s Clinton Davenport coming, let’s leave it to him.”

“Yes,” cried one and another,—and the proposition appeared to be unanimously accepted.

“Well, what is the trouble?” inquired Clinton.

Half a dozen different voices began to answer at once, when Clinton cut them all short, and told Frank, one of the oldest boys, to explain the difficulty.

“Why,” said Frank, “you know when we play ‘I spy,’ we tell off the boy, that’s to lead in the game, in this way:—

‘One-ary, youery, ickery C, Hackaback, crackaback, titobolee, Hon-pon, muscadon, Twiddledum, twaddledum, twenty-one.’”

“‘Tweedledum, twaddledum!’ you goose!” exclaimed one of the boys; “who ever heard such lingo as that? This is the right way, isn’t it, Clinton?

‘One-ary, youery, ickery, Ann, Phillacy, follacy, ticular John; Queeby, quaby, Irish Mary, Stinklam, stanklam, buck.’

There, now, isn’t that right?”

“That’s the way we have it here,” replied Clinton,—“but I suppose they say it different where Frank came from. When Oscar Preston

was here, he used to rattle it off different from both of these; I believe this is the way he said he learned it:—

‘One-ary, youery, ickery and, Phillacy, follacy, Nicholas Jones; Queeby, quaby, Irish Mary, Huldee, guldee, loo.’”

“Ho! I never heard of that way before,” said one of the boys; “I guess that’s the latest Boston edition.”

“If you can’t agree on any of these,” said Clinton, “I’ll tell you what you can do,—you can ‘tell off’ with:—

‘One-zall, zu-zall, zicker-all zan, Bobtail, vinegar, titter-all, tan, Harum, scarum, back-out.’

Or, if that doesn’t suit, then take:—

‘Eeny, meeny, mony mite; Peskalana, bona, strike; Parago, walk.’”

“Pooh!” said Frank; “that aint right, nor anywhere near it. This is the way I learned that one:—

‘Eeny, meeny, mony, my; Pistolanee, bony, sly; Argy, dargy, walk.’”

The other boys all objected to this version of the saying, but Frank insisted that if it was not the right one, it was certainly the best.

“I wonder who first made up all these poetries,” said one of the smaller boys.

“‘These poetries!’ what grammar do you study, Ned?” said Frank, with a laugh.

“Well, you know what I mean,” replied Ned; “I knew ’t wasn’t right, —I only said it just in fun.”

“I don’t know when these rhymes were made,” said Clinton, “but my father says they used to have them when he was young, and I suppose the boys have always had something of the kind. Shouldn’t you like to see all the different kinds printed in a book, Ned?”

“I guess I should,” replied Ned; “what a funny book it would make!”

The mail-stage had now arrived, and Clinton went over to the postoffice. In addition to the usual newspapers, the post-master handed him two letters. One of them was for Mrs. Preston, for Clinton often took her letters and papers from the post-office, and delivered them on his way home. The other letter was addressed to himself. It was stamped at Boston, and was in the hand-writing of his uncle. The letter for Mrs. Preston had two or three different post-marks upon it, and was somewhat dingy, as though it had travelled a great distance. This, together with the fact that the address was written in a cramped and awkward hand, led Clinton to suspect, or at least hope, it was from Jerry. He hurried back as fast as possible, and when he reached Mrs. Preston’s, his curiosity was so much excited that he determined to stop and hear who the letter was from. He watched Mrs. Preston as she first glanced at the address, and then hastily broke the seal, and before she had read half its contents, he felt so certain that he had guessed right, that he inquired:—

“Isn’t it from Jerry, Mrs. Preston?”

But Mrs. Preston was too eagerly engaged, to heed his question, and she continued reading until she had finished the letter, when she replied:—

“Yes, it is from Jerry, and I’m very much obliged to you for bringing it. Poor boy! he’s having a hard time of it, but it’s a great satisfaction to know where he is.”

“Where is he?” inquired Clinton, whose curiosity was now thoroughly awakened.

“You may read the letter, if you wish,” said Mrs. Preston, handing it to Clinton. “Read it aloud, if you please, so that Emily and Harriet may hear.”

Clinton complied with her request. Correcting the grammar, spelling, and punctuation, the letter read as follows:—

“R�� J������, M���� 30.

“D��� M�����,

I write these few lines to let you know I am alive and well, and I hope this will find you so. You will see from the date I am a good ways from home. I came here in the brig Susan, which sailed from Boston in February. We have had a very rough time. Last week we encountered a terrible gale, and I thought it was a gone case with us. We had to put in here to repair damages, and as there is a chance to send letters home I thought I would write. We are bound for Valparaiso, and have got to go round Cape Horn. It is a long voyage, and I guess I shall go to California before I come home. I don’t like going to sea so well as I expected, and I don’t mean to go another voyage. It’s a hard life, I can tell you. I am sorry I took that money, but I had to have some. I didn’t spend but little of it, but somebody has stolen the rest—some of the sailors, I suppose, but I don’t know who. I mean to pay you back again, out of my wages. I suppose father hasn’t got through logging yet. I should like to see you all, but I must wait a spell. Tell Mary I am going to fetch her home a pretty present, and I shall bring something for the others, too. I can’t see to write any longer, so good-bye to you all.

J������� P������.”

“Mother,” said Harriet, as soon as Clinton had finished reading the letter, “what does Jerry mean about taking money?”

“Don’t ask me any questions now,” replied Mrs. Preston, in a tone that cut off all further inquiries. Jerry’s theft had been a secret in her

own breast, until now; but as he had alluded to it in his letter, and as his letter must be read by all the family, she knew it could no longer be concealed. Still, she was provoked that Harriet should be so thoughtless as to allude to the subject in the presence of Clinton.

“Emily,” continued Mrs. Preston, “you run and get your atlas, and let Clinton show us where Jerry is, before he goes.”

The atlas was soon produced, and Clinton, turning to the map of South America, pointed out to the family the location of Rio Janeiro, in Brazil, on the Atlantic coast, and Valparaiso, the chief sea-port of Chili, on the Pacific side of the continent. Then, remembering his own unopened letter, he bade them good-night, and started for home.

BITTER FRUITS.