The Illegal Wildlife Trade in China

Understanding The Distribution Networks

Rebecca W. Y. Wong

City University of Hong Kong

Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

Palgrave Studies in Green Criminology

ISBN 978-3-030-13665-9 ISBN 978-3-030-13666-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13666-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019934453

© Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2019

Tis work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

Te use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

Te publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Te publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations.

Cover credit: Getty146410101

Tis Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG

Te registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

Acknowledgements

Part of this book is based on my D.Phil. thesis, which was submitted to the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford in 2014. I am grateful for the guidance and support from my doctorate advisor Professor Federico Varese, who never fails to ofer unfailing support on my research. I am also thankful for Professor Lo Tit Wing for ofering me advice, guidance, and support since my days as a doctorate student, and to my colleagues on the Criminology and Sociology team at the City University of Hong Kong. I am indebted for the never-failing support from my mentors Professor Eric Chui and Professor Ray Yep. In particular, this book would not have been possible but for the support shown by Professor Rob White, and Miss Helen Steadman and Miss Amy McLean for their professional top-notch editing and proofreading services. I would also like to thank Miss Annie Wong On Ling and Miss Yu Hanting for their unfailing technical support. My former research assistant Miss Lee Chee Yan has gone beyond the call of duty to assist me with this book. Te Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences has ofered me generous support during my term as a Visiting Professor in the Netherlands, where I fnished my fnal revisions for the manuscript.

My family continues to be a constant source of inspiration and support. My mother has and will always continue to educate me in ways no lectures, seminars, or books can ever do. As an adult, I have come to understand it was not easy for her to raise two children after the death of my father. My elder brother, despite my immaturity and selfshness, never fails to encourage and love me unconditionally.

Tere are two people I hold closest to my heart who are no longer with me today but who have imprinted deeply in my memories. Despite their untimely deaths, our brief yet irreplaceable encounters will always have a special place in my heart. I am, in many ways, unworthy of their kindness.

My best friend since childhood, Timothy P. H. Chan, was defeated by brain cancer at the age of twenty-seven. Toughts of his courage to walk into yet another chemotherapy treatment have given me immense strength during some of my roughest encounters on my feldwork journey. Te unpleasantness was only a fraction of what he had to face during his lone battle with brain cancer. Many hopes for genuine, innocent, and solid friendship which Tim unconditionally gave me during his short-lived time.

I was fortunate to have had a loving father for eleven years of my life. I realize now as an adult that such beautiful times should not be taken for granted as there are many who have never met their own father. Tere is a part only a father can fll in a child’s heart and my gratitude to my late father, for having been part of my life, is beyond words. After many years of his passing, a part of me still weeps when I think of him. It will be my greatest achievement if I can be half the person he was.

Tis book is for them both, for they have made a diference in my life beyond measures.

Hong Kong 2018

Rebecca W. Y. Wong

List of Figures

Fig. 2.1 Map of China (All the maps in this book are recreated with Adobe Photoshop)

Fig. 2.2 Vietnam (Mong Cai) to China (Dongxing, Guangxi)

Fig. 2.3 Myanmar (Muse) to China (Ruili Kunming)

Fig. 2.4 Nepal (Rasuwagadhi) to Tibet (Kerung)

Fig. 2.5 Laos (Luang Prabang) to China (Jinghong)

14

22

23

24

25

List of Tables

Table 2.1 Protected wildlife smuggled into China from neighbouring countries

Table 2.2 Selected common smuggling routes used by criminal networks across the Chinese borders

Table 2.3 Wildlife Protection Law in China

Table 4.1 Profles of Group A interviewees

Table 4.2 Profles of Group B interviewees

Table 7.1 Tree selected types of protected wildlife traded illegally as food in China

1The Demand and Supply of Protected Wildlife Products in China

The Supply and Demand for Protected Wildlife Products in China

On 8 September 2017, two days before I began writing this chapter, a Class 2 State-protected whale shark (Rhincodon typus) was wheeled on an open lorry through the streets of Fujian province and publicly dismembered in board daylight. Te process was captured on video and shared on social media. Te parts of the whale shark were said to have been transported to a local hotel as food, which the staf quickly denied when asked by local reporters. Te perpetrators were shortly arrested. Te comments on the internet poured in from all over China and the rest of the world, condemning the perpetrators for their lack of empathy and cruelty. However, only a small number of these comments touch upon the legality of the trade in protected wildlife in China. Given the growing wealth and the opening of borders between China and neighbouring states, protected wildlife is increasingly sought after for human indulgence. Tis illustrated case is merely the tip of a fourishing underground illegal wildlife trade in mainland China and Hong Kong.

© Te Author(s) 2019

R. W. Y. Wong, Te Illegal Wildlife Trade in China, Palgrave Studies in Green Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13666-6_1

Before embarking on further discussion, some distinctions on terminology must be made. Protected wildlife and State-protected wildlife will be used throughout the remainder of the book. Protected wildlife refers to the wildlife protected under the Conventions on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), of which China is a signatory member, and State-protected wildlife refers to key wildlife protected under Article 10 of the Wildlife Protection Law 2016 in China. Te consumption of both State-protected and protected wildlife is unlawful in mainland China and Hong Kong (legal status and relevant laws will be discussed in Chapter 2).

Te general illegal wildlife trade can be broken down into four stages: (1) poaching, when the wildlife is illegally caught from its natural habitat; (2) transportation, smuggling of the poached wildlife (in either dead or alive form) from its source country to its consumer state; (3) processing of wildlife products into consumable goods (for example, raw ivory needs to be processed via polishing and refnement into worked ivory products)1; and (4) the distribution and consumption of illegal wildlife products.

Tis book focuses on the fnal stage of the illegal wildlife trade in China, that of the illegal distribution of wildlife products in the underworld. Analysis of the transaction of illegal wildlife products, operations of distributing networks, and how they establish and foster trust in their illegal exchange will also be presented. Te data analysed in the following chapters is a collection of my research conducted over a six-year period, from 2011 to 2017 across Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Generally, protected wildlife is sought after within the Chinese communities for four general purposes: (1) medicinal uses; (2) collector’s items; (3) local delicacies; and (4) as exotic captive pets. One of the biggest uses for protected wildlife in China is for medicinal purposes. To date, the legal industry of traditional Chinese medicines is estimated at a value of RMB 392 billion in 2015 (Chiu, 2016). Te practice of traditional Chinese medicines includes herbal medicines (Lao, Xu, & Xu, 2012; Lu, Jia, Xiao, & Lu, 2004; Zhang, Li, Han, Yu, & Qin, 2010), acupuncture (Lao, Hamilton, Fu, & Berman, 2003; Lao et al., 2012), massage (Lao et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010), qigong (a form of gentle movement focused on cultivating breathing and stretching of the body),

or taiji (a type of traditional Chinese martial arts training) (Covington, 2001; Lu et al., 2004), and dietary treatments (Ho, 1993; Lao et al., 2012).

Today, traditional Chinese medicine is still widely practised within Chinese communities across the world. Unfortunately, wildlife products form a small yet historical part of the practice of traditional Chinese medicine and the demand for these products has been devastating to the population of some endangered species. To illustrate, the population of Southern white rhino is declining (CITES, 2016) since they are heavily poached for their horns, which are believed to be an efective cure for food poisoning, headaches, and hallucination, and even to cast away “evil spirits” (Ellis, 2005; Save the Rhino, n.d.) in the teaching of traditional Chinese medicine. To many, consuming or applying rhino horn powder in the hope of curing illness is scientifcally ungrounded and lacks any scientifc logic, and non-governmental organizations (NGO) have also promoted that the ingredients in rhino horn are the same as those found in fngernails.

However, this does not reconcile with the views of users in reality. One of my informants revealed to me that he applied rhino horn power onto the rashes of his skin when he was a young boy and his rashes were completely healed from months of treatment. Another informant commented on using rhino horn power to cure his hair loss. I have visited several traditional Chinese medicine markets during my data collection in Kunming (Yunnan province) and in Guangzhou (Guangdong province) in 2012 and 2015/2016. All the wildlife products openly sold in these markets were lawful and frequently used in the treatments of traditional Chinese medicines. Selected examples include dried seahorses, dried caterpillars, velvets, and tails of deer (Baum & Vincent, 2005; Boesi & Cardi, 2009; Childs & Choedup, 2014; Corazza et al., 2014; Giles, Ky, Do Hoang, & Vincent, 2006; Hou, Wen, Peng, & Guo, 2018; Yen, 2015; Yeshi, Morisco, & Wangchuk, 2017). Similarly, the illegal trade in protected wildlife for medicinal purposes is growing in mainland China; clearly, such was not openly sold in the stalls of the wholesale markets, and the following case judgement provides a glimpse into this illegal industry:

In June 2014, a man was arrested for buying 1170 grams of Chinese pangolin scales from a supplier for approximately RMB 2000 RMB and charged under Article 341 of the Criminal Law of China. Te man was arrested at an army checkpoint in Yunnan province after driving away from the pickup point. He admitted that he purchased the pangolin scales to use as Chinese medicine. Te judge accepted that the defendant was sincere in his plea and that he was cooperative and remorseful during the investigation. He was sentenced to a suspended sentence for two years and received a penalty fne for RMB 5000.2

Te second demand for protected wildlife products is as collector’s items, which could be broadly categorized into two kinds: (1) personal or (2) as gifts. Te frst category can be illustrated with my experience gained from speaking to sellers and consumers of ivory products. Ivory is sought after as an investment, and interviewees speak of the potential profts they can make from selling ivory in the near future, when the population of elephants is even less than what it is today. Conservationists have predicted that elephants will be extinct within twelve to twenty years if poaching persists (Gandelman, 2013; Stampler, 2015). Interviewees were also stunned by how much the value of ivory products has gone up in the past decade, while some were saddened to hear of the threats posed by the ivory trade to remaining elephants. Te majority justifed their purchase on purely economic argument: when there is a demand, there will always be a supply. Aside from economic gain, another reason for purchasing ivory products is the cultural belief that ivory products can cast of evil spirits and brings inner peace.

Unfortunately, not only the tusks of elephants are heavily sought. Te recent growing demand for the skins of Asian elephants illustrates the infuences of culture over the fate of protected wildlife. Asian elephants are now being poached for their skins, which are cut and dried in order to produce bracelet beads. Aside from being an upcoming fashion icon, users believe that beads made from the skins of Asian elephants are efective in bringing inner harmony. For instance, traders claimed beads made from elephant skin could ward of ill-health (Newman, 2016). Wildlife products are also sought as gifts for bribery. Tis is most evident in my research on the illegal tiger parts trade, as the tiger skins and bones are given to senior members, business partners, or even

government ofcials as bribery. To them, gifts such as electronic gadgets or luxurious brands are incomparable to the perceived prestige of wildlife products, for the supply is limited and declining, whereas electronics and luxurious brand will always be accessible provided one has money.

Te third usage for wildlife products is as delicacy. Te use of the term delicacy is to place emphasis on the attached prestige with consuming protected wildlife as food in the Chinese culture. Troughout my journey, I have seen this frst-hand, and was informed about protected wildlife such as tigers, pangolins, protected species of chelonians, and deer, etc. being consumed as a delicacy in family gatherings and prestigious dinner banquets. My experience in conducting research in wet markets and localized restaurants that serve protected wildlife as food will be further elaborated in Chapter 7. My encounter with restaurants that serve protected wildlife as food is one of my most memorable feldwork experience to date. To many qualitative researchers conducting feldwork, arriving at a pool of data source is a moment of relief and satisfaction. It is an understatement to term my time spent in restaurants serving protected deer and pangolin as dinner dishes as unpleasant. Consuming protected wildlife in China is not an uncommon phenomenon. In December 2015, four men were sentenced to 4.5–5.3 years of imprisonment for the illegal poaching and killing of takin, a goat antelope (Budorcas taxicolor, CITES Appendix I) in a village called Liu Jia Cun San Cha Xia, located in Shaanxi. Te four men set up a wire trap near the village and caught the takin, and the animal was subsequently dismembered and consumed among themselves or sold for proft.3

Te fourth source of demand for protected wildlife in China is as exotic pets. Although there are frequent reports of animal cruelty in China (Hugo, 2016; Middlehurst, 2015; Zhang, 2016), it is a misconception to think that the Chinese are not fond of keeping pets and this is statistically supported by the growing number of pet owners and the value of the pet industry in China. China is the third largest country of pet ownership among the world and the pet market value was RMB 97.8 million in 2015 (Zheng, 2015). Nonetheless, exotic and protected wildlife are now increasingly common to be kept as household captive pets in the Chinese communities (Bale & Gallagher, 2017).

During my time in the feld, it was common to see advertisements of exotic pets across social media and websites widely accessible in mainland China and Hong Kong; one such example is the online sales of chelonians, keeping chelonians as pets is a welcome phenomenon in China and this could be explained by historical cultural beliefs since turtle is symbolized as health and longevity in the Chinese society (Yardley, 2007).

Te aforementioned selected examples used to illustrate the markets of illegal wildlife products in China points to one general observation: the demand for illegal wildlife products is growing in China, paving the way and opportunities for criminal organizations. Te underlying motivation for consumption is largely driven by cultural beliefs and lacks scientifc evidence.

This Book

Te aim of this book is not to single out China’s exploitation of protected wildlife, since the illegal wildlife trade and exploitation in wildlife happens on a global scale, even in some of the most developed countries in the world. Troughout my time in the feld, I have met countless compassionate individuals from mainland China and Hong Kong who are outraged and disgusted by the underground illegal wildlife trade that is taking place in their country. Te aim of this book is to ofer a theoretical analysis on the illegal distribution of wildlife products in China. Based on data collected in the feld, this book will provide insights into the illegal transaction of worked ivory products (Chapter 5), the operation and organization of criminal networks supplying tiger parts products (Chapter 6) and how suppliers of illegal wildlife foster trust and exchange with their consumers in the consumption of protected wildlife as delicacy (Chapter 7). All the names of the interviewees have been changed owing to the sensitivity of the issues discussed during our interviews.

Existing literature and scholarly studies on the Chinese illegal wildlife trade is limited (Jiang, 2015; Moyle, 2009; Wong, 2015). Terefore, this book draws on various sources. Te primary source relied upon is based on qualitative interviews I conducted during 2011–2017 across

mainland China and Hong Kong. Te diversity in the ethnic, economic, and social background of my interviewees gave me great insights into the world of illegal wildlife trade. My interviewees include members of the general population in my feldwork sites, people involved in the illegal wildlife trade (i.e. supplier of endangered wildlife products, traders employed by the supplier of such illegal networks, consumers of illegal wildlife products, family members of traders and consumers, law enforcement personnel and representative from NGO etc.). Te secondary sources relied upon in this book are reported data generated from newspaper and media reports in both Chinese and English, NGO reports, social media posts in Chinese, and court judgements from the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong judiciary. Discussion on my methodology will be further elaborated in Chapter 4.

Tis book endeavours to achieve three general aims. First, to contribute to the general development of green criminology and in specifc to the literature of the illegal transactions of protected wildlife at the distribution stage. Second, an understanding of how illegal transactions are carried out can help shed insights on policy changes and enforcement. Tird, theoretical frameworks (such as that of trust, networks and situational crime prevention) applied in the understanding of the distribution of illegal wildlife products can also make contributions to ongoing sociological and criminological discussions.

On a personal note, I believe that this book will inspire others to refect on the scale of harm we as human beings are capable of inficting to non-human species. I only hope that it will not be too late to rectify the damage we have done and that this work will paint the foundations and contextual background to generate interests in the study of illegal wildlife trade especially on the situation in Asia, which to date still lacks attention.

Organization of the Book

Tis book is constructed of two main parts.

Te frst part consists of Chapters 1, 2 and 3, which paint the contextual and theoretical background in understanding the illegal wildlife trade and relevant enforcement measures in China.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of China within the global illegal wildlife trade from two general perspectives. First, to examine the relationship between China’s geographical location and the smuggling of protected wildlife products. Tis chapter also demonstrates how criminal groups exploit China’s far-reaching borders to smuggle wildlife products into China. Second, this chapter gives an overview of China’s eforts in enforcing the illegal wildlife trade domestically and the developments in their legislations.

Chapter 3 ofers a summary on the existing theoretical framework on the study of green criminology and its position within the broader study of criminology in the discipline of social sciences. Te chapter describes the nature of green criminology and its implications. Following on, the chapter dives into examining the frst three stages of the illegal wildlife trade, including that of poaching, smuggling, and processing of wildlife products.

Te second part of the book consists of four chapters outlining the preparation of conducting feldwork on research on the illegal wildlife trade and the analysis of my feldwork fndings by focusing on the transaction, the criminal networks and from the consumer.

Chapter 4 discusses the challenges in conducting feldwork studies in China against the context of the illegal wildlife trade. Te analysis is based on my feldwork collection for my doctorate thesis during 2011–2013 in Mainland China. A brief description of the feldwork sites is given before discussing the challenges and obstacles faced during the feldwork. In doing so, this chapter endeavours to inform readers of the reality in the feld and to inspire other like-minded social sciences researchers on debates and discussions on conducting criminological feldwork and to inform them of the demands of feld research.

Chapter 5 provides insights into the actual transaction of worked ivory products against the theoretical framework of situational crime prevention theory. Te global illegal trade in ivory can be broken down into four stages: (1) poaching of the elephant tusks—capturing an elephant in its natural habitat in order to remove its tusks, which results in the death of the animal; (2) smuggling poached tusks—which involves smuggling tusks out of the source country into the destination

countries; (3) processing raw ivory into worked ivory products; and (4) selling worked ivory items to buyers.

Chapter 6 explores the operation of seven distributing networks specializing in the illegal supply of tiger parts. Te focus of this chapter is on the network organizations of criminal networks and their mode of operation in supplying tiger parts products across three diferent cities in Mainland China and how they employ diferent mechanisms to avoid risk of enforcement.

Chapter 7 focuses on the consumer and on the specifc issue of how consumers resolve the issue of trust in their purchase of illegal commodities. Te context of this article is situated in light of the illegal transaction of protected wildlife in China for consumption as a delicacy. In Chapter 6, I explore how bonds of trust between criminals operating in the same illegal tiger parts trading network are formed, but when it comes to how trust is formed between the buyers and suppliers of protected wildlife, the issue remains unresolved in this specifc context. Te exploration of this under-studied area in Chapter 7 provides theoretical insights for criminologists on the study of green criminology and how trust is formed under illegal conditions.

Te fnal chapter ofers refection and concludes.

Notes

1. Note that stages (2) and (3) do not necessarily have to follow this order. Te wildlife can be processed before it is smuggled to its destination country.

2. Yunnan Sheng Shuang Jiang La Hu Zu Wa Zu Bu Lang Zu Dai Zu ZI Zhi Xian Renmin Fa Yuen Xing Shi Pan Jue Shu (2014), Shuang Xing Chu Zi 247 (Yunnan Province Lahu – Va – Blang – Dai Autonomous County of Shangjiang People’s Court Criminal Judgement (2014) No. 74).

3. Shanxi Sheng Tai Bai Xian Renmin Fa Yuan Xing Shi Pan Jue Shu (2016) Shan 0331 Xing Chu 28 (Shaanxi Province Taibai People’s Court Criminal Judgement [2016] 0331 No. 28).

References

Bale, R., & Gallagher, S. (2017, September 7). Young collectors, traders help fuel a boom in ultra-exotic pets. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/09/wildlife-watch-exoticpets-popular-china/.

Baum, J. K., & Vincent, A. C. J. (2005). Magnitude and inferred impacts of the seahorse trade in Latin America. Environmental Conservation, 32(4), 305. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892905002481.

Boesi, A., & Cardi, F. (2009). Cordyceps sinensis medicinal fungus: Traditional use among Tibetan people, harvesting techniques, and modern uses. Herbal Gram, 83, 52–61.

Childs, G., & Choedup, N. (2014). Indigenous management strategies and socioeconomic impacts of Yartsa Gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) harvesting in Nubri and Tsum, Nepal. HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 34(1), 7.

Chiu, Natalie. (2016). Traditional Chinese medicine industry: Modernization creating opportunities and driving growth. Retrieved from http://www. gfgroup.com.hk/docs/gfgroup/securities/Report/CorporateReport/ CorpReport_20161031__e.pdf.

CITES. (2016). A report from the IUCN Species Survival Commission (IUCN SSC) African and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and TRAFFIC to the CITES Secretariat pursuant to Resolution Conf. 9.14 (Rev. CoP15). Retrieved from https://cites.org/ sites/default/fles/eng/cop/17/WorkingDocs/E-CoP17-68-A5.pdf.

Corazza, O., Martinotti, G., Santacroce, R., Chillemi, E., Di Giannantonio, M., Schifano, F., & Cellek, S. (2014). Sexual enhancement products for sale online: Raising awareness of the psychoactive efects of yohimbine, maca, horny goat weed, and Ginkgo biloba. BioMed Research International, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/841798.

Covington, M. B. (2001). Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum, 14(3), 154–159. https://doi.org/10.2337/ diaspect.14.3.154.

Ellis, R. (2005). Poaching for traditional Chinese medicine. In R. Fulconis (Eds.), Save the Rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6 (pp. 89–93). Retrieved from Save the Rhino: http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_ fles/117/1175860939.pdf.

Gandelman, J. (2013, August 22). Will elephants be extinct by 2025? Te Week. Retrieved from http://theweek.com/articles/460823/elephants-extinct-by-2025.

Giles, B. G., Ky, T. S., Do Hoang, H., & Vincent, A. C. (2006). Te catch and trade of seahorses in Vietnam. In Human Exploitation and Biodiversity Conservation (pp. 157–173). Dordrecht: Springer.

Ho, Z. C. (1993). Principles of diet therapy in ancient Chinese medicine: ‘Huang Di Nei Jing’. Asia Pacifc Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2, 91–95.

Hou, F., Wen, L., Peng, C., & Guo, J. (2018). Identifcation of marine traditional Chinese medicine dried seahorses in the traditional Chinese medicine market using DNA barcoding. Mitochondrial DNA Part A, 29(1), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701394.2016.1248430.

Hugo, K. (2016, July 18). Exclusive: Investigation documents animal sufering at Chinese circuses. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/07/wildlife-china-circus-animal-abuse/.

Jiang, N. (2015). A crime pattern analysis of the illegal ivory trade in China. Retrieved from http://ir.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/fles/uploads/ 2016-09/tec_working_paper_1-2015.pdf.

Lao, L., Hamilton, G. R., Fu, J., & Berman, B. M. (2003). Is acupuncture safe? A systematic review of case reports. Alternative Terapies in Health and Medicine, 9(1), 72–83.

Lao, L., Xu, L., & Xu, S. (2012). Traditional Chinese Medicine. In A. Längler, P. J. Mansky, & G. Seifert (Eds.), Integrative Pediatric Oncology (pp. 125–135). Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-04201-0_9.

Lu, A. P., Jia, H. W., Xiao, C., & Lu, Q. P. (2004). Teory of traditional Chinese medicine and therapeutic method of diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 10(13), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10. i13.1854.

Middlehurst, C. (2015, June 21). Tousands of dogs and cats slaughtered at China festival despite government promises to crack down. Te Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/ 11689773/Thousands-of-dogs-and-cats-slaughtered-at-China-festivaldespite-government-promises-to-crack-down.html.

Moyle, B. (2009). Te black market in China for tiger products. Global Crime, 10(1–2), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570902783921.

Newman, N. (2016, September 24). Hideous sight of a butchered elephant exposes the sick trade in animals’ hides to feed soaring demand in China. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article3805873/The-scourge-skin-poachers-Hideous-sight-butchered-elephantexposes-sick-trade-animals-hides-feed-soaring-demand-China.html.

Save the Rhino. (n.d.) Poaching for rhino. Retrieved from https://www. savetherhino.org/rhino_info/threats_to_rhino/poaching_for_rhino_horn.

Shuang Xing Chu Zi 247 (Yunnan Province Lahu – Va – Blang – Dai Autonomous County of Shangjiang People’s Court Criminal Judgement (2014) No. 74).

Stampler, L. (2015, Marh 23). African elephants could be extinct within 20 years, esperts say. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/3754637/ african-elephants-could-be-extinct-within-20-years-experts-say/.

Wong, R. W. (2015). Te organization of the illegal tiger parts trade in China. British Journal of Criminology, 56(5), 995–1013. https://doi.org/10.1093/ bjc/azv080.

Wong, D. (2016). Te problematic rise of exotic pets in China. Retrieved from http://www.thatsmags.com/shanghai/post/15374/exotic-pets-china.

Yardley, J. (2007, December 5). China’s turtles, emblems of a crisis. Te New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/05/world/ asia/05turtle.html.

Yen, A. L. (2015). Conservation of Lepidoptera used as human food and medicine. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 12, 102–108. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.11.003.

Yeshi, K., Morisco, P., & Wangchuk, P. (2017). Animal-derived natural products of Sowa Rigpa medicine: Teir pharmacopoeial description, current utilization and zoological identifcation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 207, 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.06.009.

Yunnan Sheng Shuang Jiang La Hu Zu Wa Zu Bu Lang Zu Dai Zu ZI Zhi Xian Renmin Fa Yuen Xing Shi Pan Jue Shu. (2014).

Zhang, Y. (2016, August 4). Abused dog rescued by volunteers. Shenzhen Daily. Retrieved from http://www.szdaily.com/content/2016-08/04/content_13683971.htm.

Zhang, P., Li, J., Han, Y., Yu, X. W., & Qin, L. (2010). Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A general review. Rheumatology International, 30(6), 713–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00296-010-1370-0.

Zheng, C. (2015, October 16). China’s pet tally reaches 100 million, mostly cats and dogs. China Daily. Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/ china/2015-10/16/content_22203711.htm.

2

China and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

China’s Geographical Location and Its Relationship with the Illegal Wildlife Trade

To understand the reason for China’s growing infuence in the global illegal wildlife trade, we must frst recognize the geographical location of China and her neighbouring regions and how this contributes to the domestic illegal wildlife trade (Fig. 2.1).

Aside from theoretical studies highlighting the issue of enforcement along vast borders (Dunn, 2001; Gurette & Clarke, 2005; Shirk, 2011), investigations conducted by non-governmental organizations have also documented the illegal trade of protected wildlife along the Chinese borders to and from other neighbouring countries (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2015; TRAFFIC, 2013a; United Nations Ofce

It is important to point out that there are a number of translations of the Wildlife Protection Law. I refer to the Simplifed Chinese version accessible on the National People’s Congress website for utmost accuracy. See: National People’s Congress http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/ xinwen/2018-11/05/content_2065670.htm.

© Te Author(s) 2019

R. W. Y. Wong, Te Illegal Wildlife Trade in China, Palgrave Studies in Green Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13666-6_2

Fig. 2.1 Map of China (All the maps in this book are recreated with Adobe Photoshop)

on Drugs and Crime, 2013; World Wildlife Fund, n.d.-a). China borders upon major countries where many of the world’s protected wildlife resides, including but not limited to Vietnam, Laos, Russia Federation, Taiwan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tailand, Nepal, Kyrgyzstan, Bhutan, Myanmar, and India.

Table 2.1 provides a summary of selected protected wildlife native in China’s neighbouring countries, which are found to be smuggled into China:

Table 2.1 Protected wildlife smuggled into China from neighbouring countries

Evidence of illegal wildlife trade into China and relevant Chinese legislations

Status under CITES, IUCN Red List and law in source country

Between 2011 and 2013, an estimated number of 233,980 pangolins were killed for their scales. However, it is believed that this fgure represents only 10% of the actual number (World Wildlife Fund, n.d.-d) Further, CITES data shows that 3.09 million worth of pangolin and their body parts were seized during 2010—2014 ( Nijman, Zhang, & Shepherd, 2016 )

Under Chinese law, both native and non-native pangolin species are listed as Class II under the Wildlife Protection Law 2016

All species of the pangolins are upgraded to Appendix 1 of CITES since September 2016 The Sunda, Chinese pangolin are classifed as “Critically Endangered” under the IUCN Red List. The Indian pangolin is classifed as “Endangered” Under Myanmar law, pangolins are a protected species under Protection of Wildlife and Wild Plants and Conservation of Natural Areas Law ( 1994 ). The killing, poaching, possessing, selling, transporting, or transferring of a pangolin is punishable with imprisonment up to 7 years or a fne up to MMK 50,000 (approximately USD 8183)

(continued)

Country Native wildlife

Myanmar Pangolins 3 out of 4 species of the Asian pangolins are native to Myanmar, including: (1) Sunda pangolin; (2) Chinese pangolin; and (3) Indian pangolin Pangolins are demanded for their scales, which serves as a valuable ingredient in the practice of traditional Chinese medicine (Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association, 2009 ; Environmental Investigation Agency, 2017a ; International Fund for Animal Welfare, 2017 ; Soewu & Adekanola, 2011 )

Table 2.1 (continued)

Evidence of illegal wildlife trade into China and relevant Chinese legislations

Status under CITES, IUCN Red List and law in source country

In 2015, Chinese customs seized 970 kg of pangolin scales in Fangchenggang, a town in Guangxi autonomous region that shares a 696 km border with Vietnam (Huaxia, 2015 )

All species of the pangolins are upgraded to under Appendix 1 of CITES since September 2016 The Sunda, Chinese pangolin are classifed as “Critically Endangered” under the IUCN

Red List Decree 32/2006/ND-CP is Vietnam’s primary environmental protection law. Under this Decree, it is illegal to hunt, transport, keep, advertise, sell, and purchase protected wildlife (or their body parts). The same Decree has categorized protected wildlife into two groups: critically endangered species (IB) and threatened and rare species (IIB)

Decree 160/2013/ND—CP established a regulatory system to evaluate which species should be categorized as requiring protection Both the Chinese and Sunda pangolins are fully protected under the two decrees:

(continued)

Country Native wildlife

Pangolins

Vietnam

Two species of pangolins are native to Vietnam, (1) the Chinese pangolins and (2) Sunda pangolins

Like the situation outlined above in Myanmar, between 2011 and 2013, an estimated number of 233,980 were killed for their skins. However, it is believed that this fgure represents only 10% of the actual number (World Wildlife Fund, n.d.-d) Since 2005, Education for Nature (Vietnam) has recorded more than 69 tonnes of frozen pangolin scales in Hai Phong

Evidence of illegal wildlife trade into China and relevant Chinese legislations

Status under CITES, IUCN Red List and law in source country

Seizure of tiger parts (including tiger skin, paw, bone) are frequently made along the China—Russia border (Nowell & Xu, 2007 ; Verheij, Foley, & Engel, 2010 )

The most recent and biggest seizure was made in January 2018, when custom offcers seized two minibuses and an SUV that was traffcking skins and bones of four Siberian and Amur tigers and 870 brown bear paws. (Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 2018 )

The Amur Tiger is a Class 1 Protected Species under Chinese legislation and CITES. It is also “endangered” under IUCN In Russia, the killing of Amur tigers is punishable for a fne of up to RUB 1.1 million (approximately USD 35,000) (TRAFFIC, 2013b ; World Wildlife Fund Russia, 2013 )

In 2012, a Chinese national was found with two Amur tiger paws packed in plastic bags and taped to her body (World Wildlife Fund, 2012 )

The Kamchatka Brown Bear is classifed as “Least Concern” under the IUCN. It is listed under Appendix 2 of CITES and Class 2 protection under Chinese legislation (Bear Conservation, 2017 )

The paw of the bear is considered a delicacy in the Chinese society and served illegally in restaurants (Linzey, 2013 ; Servheen, Herrero & Peyton, 1999 )

In July 2016, Russian customs seized over 500 bears paws heading to Tongjiang city in the Heilongjiang province bordering from the Russian town, Khabarovsk (Russia Today, 2016 )

In 2011, TRAFFIC reported a seizure of over 100 bear paws made in Blagoveschensk, bordering China (TRAFFIC, 2011 )

Table 2.1 (continued) (continued)

Country Native wildlife

Amur Tiger 95% of the world’s remaining Amur tigers live in Russia Far East Tiger body parts are a recognized ingredient in the practice of TCM (Bonello, 2007 ; Mainka & Mills, 1995 ; Prynn, 2004 ; Wong, 2015 ) Kamchatka brown bear World Wildlife Fund estimated that over 100,000 brown bears currently reside in Russia (WWF, n.d.-b)

Russia

Table 2.1 (continued)

Evidence of illegal wildlife trade into China and relevant Chinese legislations

Status under CITES, IUCN Red List and law in source country

The two main reasons for the demand in Asian elephants are for (1) display in zoo and circus and (2) for jewellery and decorative items (Maurer, Rashford, Chanthavong, Mulot, & Gimenez, 2017 ; Shepherd & Nijman, 2008 ; WildAid, 2014 )

The Decree of the Council of Ministers No 185/CCM— Concerning the Prohibition of Wildlife Trade ( 1986 ) prohibits the export of all protected wildlife The Decree of the Council of Ministers No 118/CCM—On the Management and Protection of Aquatic Animals and Wildlife from Hunting and Fishing ( 1989 ) also prohibits the hunting of all endangered wildlife

In 2005, red panda fur was seized at the Gola La Pass in Nepal. A local villager from Nepal was caught attempting to smuggle and sell the fur in Tibet (Glatston, 2010 ; Glatston, Wei, Than, & Sherpa, 2015 )

The red panda is protected under Appendix 1 of CITES and Class 1 protection under Chinese legislation Red panda is classifed as endangered under the IUCN Red List The National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973 (Nepal) prohibits the killing of CITES Appendix I wildlife. Under Section 10 of the Act, any individual who kills or attempts to kill a red panda is punishable for imprisonment of up to 10 years

(continued)

Country Native wildlife

Asian Elephants According to the IUCN’s SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group in 2008, there are around 1000 Asian elephants left in Laos. Their global population is around 52,000 (IUCN SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group, 2008 )

Laos

Red Panda In 2011, IUCN estimated that the global population of red panda to be around 10,000. There are an estimated of 300 red pandas in Nepal (Bista & Paudel, 2014 )

Nepal

Table 2.1 (continued)

Evidence of illegal wildlife trade into China and relevant Chinese legislations

Status under CITES, IUCN Red List and law in source country

Antelope are mainly used in the practice of TCM (Coghlan et al., 2012 ; Milner-Gulland et al., 2003 ). They are mixed or hidden with fruits and other items and smuggled into China from Russia via trucks and cars (van Uhm, 2016 , pp. 222–223)

The Ministerial Decree No. 1457 on the State Protection of Wildlife Species gives protection to endangered wildlife

Country Native wildlife

Kazakhstan Saiga Antelope An estimated population of 50,000 saiga antelopes left in the wild (World Wildlife Fund, n.d.-c)

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

CHAPTER XVI

CLASSES SCAPHOPODA AND PELECYPODA

CLASS SCAPHOPODA

Head rudimentary, mantle edges ventrally concrescent, forming a tube opening before and behind, and covered with a shell of the same shape; sexes separate.

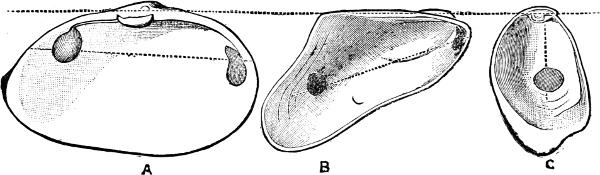

F�� 299 Anatomy of Dentalium: a, anterior aperture of mantle; f, foot; g, genital gland; k, kidney; l, liver (After Lacaze-Duthiers )

The Scaphopoda form a small but very distinct class, whose organisation is decidedly of a low type. The body is usually slightly curved, the concave side being the dorsal; muscles near the posterior end attach the body to the shell. The foot, which can be protruded from the anterior or wider aperture, is rather long, pointed, and has sometimes two lateral lobes (Dentalium), sometimes a

terminal retractile disc (Siphonodentalium), sometimes a retractile disc with a central tentacle (Pulsellum). The cephalic region, as in Pelecypoda, is covered by the mantle. The mouth is situated on a kind of projection of the pharynx; the buccal mass, containing the radula (p. 236), is at the base of the foot, and the intestine branches forward from the front part of the stomach. The liver (Fig. 299) is paired, and consists of a number of symmetrical, radiating coeca. There are no eyes, but on each side of the mouth are small bunches of exsertile filaments (captacula), which appear to act as tactile organs for the seizing of food. There is no special respiring apparatus, heart or arterial system, breathing being conducted by the walls of the mantle. The nervous system has already been described (p. 205).

Two kidneys open on either side of the anus. The genital gland is large, occupying nearly all the posterior part of the body, the sexual products being emitted through the right kidney. The veliger has already been figured (p. 131, Fig. 44). The embryonic shell is formed of two calcareous laminae, which subsequently unite to form the tube.

With regard to their general relationships, the Scaphopoda resemble the Gasteropoda in their univalve shell, and in the possession of a radula; while the pointed foot, the non-lobed velum in the veliger, the generative system, the bilateral symmetry of the organs generally, and the absence of any definite head, eyes, or tentacles, are points which approximate them to the Pelecypoda.

The Scaphopoda are known from Devonian strata to the present time. They are found at a depth of a few fathoms to very deep water. The only three genera are Dentalium, Siphonodentalium (subg. Cadulus), and Pulsellum, which differ in the structure of the foot, as described above.

CLASS PELECYPODA

Cephalic region rudimentary, mantle consisting of two symmetrical right and left lobes, covering the body and secreting a bivalve shell hinged at the dorsal margin; no radula, sexes usually separate.

Reference has already been made to the reproductive system (p. 145), breathing organs (p. 164 f.), mantle (p. 172), nervous system (p. 205), digestive system (p. 237 f.), and nomenclature of the various parts of the shell (p. 269 f.).

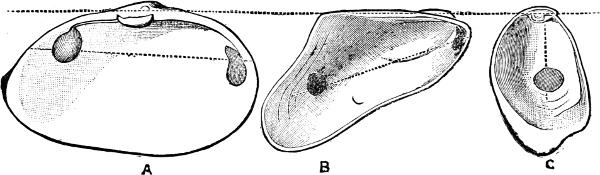

The shape of the shell, in many Pelecypoda, involving as it does the position, size, and number of the adductor muscles, is probably due to mechanical causes, depending on the habits and manner of life of the individual genus. Thus in a typical dimyarian or twomuscled bivalve, e.g. Mya (Fig. 300, A), the adductor muscles lie well towards each end of the long axis of the shell, with the hinge about midway between them. In this position they are best placed for effectually closing the valves, and since they are nearly equidistant from the axis of motion, i.e. from the hinge, they do an equal amount of work, and are about equal in size. But in a form like Modiola, where the growth of the shell is irregular in relation to the hinge-line, the anterior muscle is brought nearer and nearer to the umbones, where its power to do work, and therefore its size, becomes less and less. But the work to be done remains the same, and the posterior muscle has to do it nearly all; hence it moves farther and farther away from the hinge-line, and at the same time gains in size. In shells like Ostrea, Pecten, and Vulsella, the anterior muscle, having drawn into line with the hinge and the posterior muscle, becomes atrophied, while the posterior muscle, having double work to do, has doubled its size.[409]

F�� 300 Illustrating changes in the position and size of the adductor muscles according to the shape of the shell: A, Mya; B, Modiola; C, Vulsella The upper dotted line shows the hinge-line, the lower connects the two muscles

The development of the foot, again, largely depends upon habits of life. It is well developed in burrowing forms, while in sessile genera (Ostrea, Chama, Spondylus) it becomes unnecessary and aborts. Even in Pecten, which does not become sessile, but has ceased to use the foot as an organ of progression, a similar result follows. Forms which burrow deeply often “gape” widely, sometimes at one end only, sometimes at both. Venus, Donax, Tellina, Mactra, which are shallow burrowers, do not gape; Solen, Lutraria, and to a less degree Mya, burrow deeply and gape widely. In order to burrow deeply the foot must be highly developed, and the larger it becomes, the more will it tend to keep the valves apart at the place where it is habitually protruded. Burrowing species always remain in communication with the surface by means of their siphons, the constant extension of which tends to keep the valves apart at the end opposite to the foot. Burrowing species, again, tend to burrow in such a way as to descend most easily, and not be impeded by their own shells; in other words, they act as a wedge, and descend with their narrowest part foremost. But the burrowing organ, the foot, has to follow suit, and gradually draws round to the narrowest part of the shell, so that the habitual deep burrower, such as Lutraria, lies with its long axis exactly at right angles to the surface, its siphons protruding from, and keeping open, the uppermost or posterior margin of the shell, and the foot producing the same effect upon the lower or anterior margin. The deeper the burrower, the more elongated does the shell become, until, through forms like Pholas and Saxicava, we arrive at Solen, the most highly specialised burrower of all, in which the breadth of the shell is equal throughout, and no obstructive curve exists to impede its rapid ascent or descent.

The Pelecypoda have been classified in various ways; by the completeness or sinuation of the pallial line, depending on the absence or presence of siphons, by the number of adductor muscles, by the character of the hinge-teeth, and by the number of the branchiae. For various reasons, none of these methods have proved entirely satisfactory That adopted here was suggested by Pelseneer, and depends upon the character of the branchiae

themselves, as suggesting successive stages of development (p. 166 f.).

Order I. Protobranchiata

Branchial filaments not reflected, the two rows inclined at a right angle (more or less), ventral surface of foot more or less flattened, byssogenous apparatus little developed, a single anterior aorta, kidneys distinct, sexes separate, each genital gland opening into the corresponding kidney.

F��. 1. Nuculidae.—Labial palps very large, rows of branchial filaments at right angles to one another, mantle edges open, siphons contracted, foot disc-shaped, elongated; shell equivalve, oval, or produced, interior generally nacreous, hinge with numerous saw-like teeth. Silurian ——. Principal genera: Nucula (heart dorsal to the rectum); Palaeoneilo (Devonian), (?) Sarepta, Leda, Yoldia, Malletia; Tyndaria (Upper Tertiary), Lyrodesma (Silurian), Actinodonta (Silurian), Babinka (Silurian).

F��. 2. Solenomyidae.—Labial palps united, one row of branchial filaments pointing dorsally, the other ventrally; mantle edges in great part united postero-ventrally, a single siphonal orifice with two very long tentacles, foot proboscidiform, with a round denticulate disc at the end; shell equivalve, resembling a Solen, with a strong corneous periostracum; no hinge-teeth, ligament internal. Single genus, Solenomya. (?) Cretaceous ——].

Order II. Filibranchiata

Rows of branchial filaments parallel, pointing ventrally, reflected, and provided with interfilamentary ciliated junctions, foot usually with a well-developed byssogenous apparatus.

Sub-order I. Anomiacea.—Heart dorsal to the rectum, a single aorta, foot small, anterior adductor very small; shell ostreiform, no hinge-teeth, fixed by a calcified byssus traversing the right valve (Fig. 173, p. 262).

F�� Anomiidae.—Jurassic ——. Genera: Anomia, Placunanomia; Carolia (Eocene), Placuna; Hypotrema (Jurassic), Placunopsis (Oolite).

Sub-order II. Arcacea.—Mantle edge open, both adductors well developed, heart with two aortae, branchiae free, without interlamellar junctions, no siphons; renal and generative apertures distinct.

F��. 1. Arcadae.—Mantle edge with composite eyes; shell round or trapezoidal, solid, often with stout bushy periostracum; ligament often external, on a special area; hinge with numerous lamelliform teeth. Ordovician ——. Principal genera: Arca (incl. Barbatia, Scaphula, and Cucullaea), heart dorsal to rectum; Pectunculus, Glomus, Limopsis; Trinacria and Nuculina (Tertiary).

F��. 2. Trigoniidae.—Foot large, hatchet-shaped, with ventral disc; no byssus, mantle edge with ocelli; shell sub-trigonal, hingeteeth few, strong; interior violet-nacreous. Devonian ——. Genera: Trigonia; Myophoria and Schizodus (Trias), Cyrtonotus (Devonian).

F��. 301. Trigonia pectinata Lam., Sydney, N.S.W.

Sub-order III. Mytilacea.—Mantle edges fused at one point, anal orifice distinct, anterior terminal adductor small, one aorta, branchiae with interfoliary junctions, genital glands penetrating the side of the mantle and opening by the side of the kidneys.

F�� Mytilidae.—Byssus well developed, shell more or less equivalve, oval, broad; hinge-teeth evanescent. Devonian——. Principal genera: Mytilus?, Myalina, Septifer, Modiola, Lithodomus, Crenella, Dacrydium, Myrina, Idas, Modiolaria, Modiolarca.

Order III. Pseudolamellibranchiata

Mantle edges entirely open, foot little developed, anterior adductor usually aborted, branchial filaments reflected, with interlamellar junctions, which are sometimes vascular; genital glands opening into the kidneys or close to the apertures of the kidneys.

F��. 1. Aviculidae.—Foot long, tongue-shaped, byssogenous apparatus well developed, branchiae concrescent with the mantle, adductor muscle sub-central, at times a small anterior adductor, siphons absent; shell usually inequivalve, dorsal margin straight, often very long, winged, lateral teeth much prolonged; structure of shell cellular, inside prismatic, outside nacreous. Palaeozoic ——.

Principal genera: Avicula, including Meleagrina, Malleus; Vulsella (no wings or hinge-teeth); Perna, including Crenatula, Inoceramus (ligaments in a number of fossettes); Aucella and Monotis (Palaeozoic and Secondary); Pterinaea and Ambonychia (Palaeozoic); Pinna; Aviculopinna (Carboniferous).

F��. 302. Avicula heteroptera Lam., Australia, showing the inequivalve shell and byssal sinus (bs).

F��. 2. Prasinidae.—Shell very small, umbones anterior, incurved, anterior side depressed, hinge-teeth replaced by dentiform

projections of the lunule fitting into corresponding grooves. Recent. Single genus, Prasina.

F�� 3. Ostreidae.—Heart generally ventral to the rectum, branchiae concrescent with the mantle, no byssus; shell inequivalve, fixed by the left valve, form irregular. Jurassic ——. Genera: Ostrea; Heligmus (Oolite), Naiadina (Cretaceous), Pernostrea (Jurassic).

F��. 4. Pectinidae.—Byssus usually absent, mantle edge open, duplicated, folded back, with pallial ocelli; branchiae not concrescent with the mantle; shell with unequal “ears” at the umbo, hinge-teeth lamelliform, often obscure. Silurian——. Principal genera: Pedum, Chlamys, Hinnites, Hemipecten, Amussium, Pecten; Aviculopecten (Palaeozoic), Crenipecten.

F��. 5. Limidae.—Mantle edge as in Pecten, tentaculate; shell sub-equivalve, eared, fixed by a byssus or free. Carboniferous——. Genera: Lima (Fig. 85, p. 179), Limea.

F��. 6. Spondylidae.—Foot with a peduncular appendage, no byssus, numerous pallial ocelli; shell fixed by right valve, surface often very spinose, two cardinal teeth in each valve. Jurassic——. Genera: Plicatula, Spondylus; Terquemia (Lias).

F��. 303. Pecten pallium L., East Indies.

F��. 304. Spondylus petroselinum Sowb., Mauritius; on a coral.

F��. 7. Dimyidae.—Shell ostreiform, fixed, hinge with or without symmetrical teeth, two muscular impressions. Single genus, Dimya (Tertiary).

Order IV. Eulamellibranchiata

Mantle edges united at one or more points, branchiae with interfilamentary junctions which are always vascular, genital glands not opening into the kidneys, usually two adductor muscles.

Sub-order I. Submytilacea.—Mantle edges more or less open, anal orifice distinct, usually no siphons, pallial line usually simple, cardinal and lateral teeth well marked.

F��. 1. Carditidae.—Foot with a byssus or groove, branchiae large, unequal; shell equivalve, solid, radiately grooved, one or two oblique cardinal teeth, one or two laterals. Silurian ——. Principal genera: Venericardia, Cardita, Carditella, Carditopsis, Milneria; Pleurophorus (Palaeozoic), Anodontopsis (Silurian).

F��. 2. Astartidae.—A short anal siphon, labial palps large; shell triangular, thick, ligament external, hinge with two or three cardinals in each valve, laterals obscure.? Devonian ——. Principal genera:

Astarte; Pachytypus (Jurassic), Plesiastarte (Eocene), Parastarte, Woodia, Opis (Secondary strata), Prosocoelus (Devonian).

F�� 3. Crassatellidae.—Mantle with anal orifice or open; shell equivalve, thick, subtriangular, ligament in an internal fossette, hinge with two cardinals, laterals produced. Cretaceous——. Principal genus, Crassatella.

F��. 4. Cardiniidae.—Shell equivalve, oval or triangular, ligament external, cardinal teeth small, laterals fairly strong. Devonian—— Oolite. Principal genera: Cardinia, Anthracosia, Carbonicola, Anoplophora

F��. 5. Cyprinidae.—Anal and branchial orifices complete, papillose, foot thick; shell variable, equivalve, thick, umbones often spiral, hinge-teeth very variable, ligament external. Jurassic——.

Principal genera: Cyprina; Pygocardia (Crag), Veniella (Cretaceous), Venilicardia (Secondary strata), Anisocardia (Jurassic), Isocardia, Libitina, Coralliophaga; Basterotia (Eocene). The families Pachydomidae (Palaeozoic) and Megalodontidae (Palaeozoic— Secondary) are probably related to the Cyprinidae.

F��. 305. Isocardia vulgaris Reeve, China

F��. 6. Aetheriidae.—Anal orifice complete, foot absent, labial palps large; shell irregular, free or fixed, no hinge-teeth. Fluviatile, recent only. Genera: Aetheria, Mülleria, Bartlettia.

F�� 7. Unionidae.—Foot large and thick, no byssus, anal siphon short, branchial orifice complete or not, siphon present or absent, embryo of certain groups passing through a glochidium stage (p. 146); shell equivalve, sometimes very thick, nacreous within, hinge variable. Fluviatile. Jurassic——. Principal genera: Unio (subg. Arconaia), Monocondylaea, Pseudodon, Anodonta, Solenaia, Mycetopus, Mutela, Spatha, Hyria, Castalia, Leila.

F��. 8. Dreissensiidae.—Both siphons prominent, foot tongueshaped, byssiferous; shell mytiliform, with small internal septum. Genera: Dreissensia; Dreissensiomya (Tertiary). The common Dreissensia polymorpha Pall. was distributed over large parts of Europe in later Tertiary times. From unknown causes it died out, and has during the past two hundred years been regaining its position, migrating N. and W. from its original habitat, the Caspian, by the Volga and its Oka confluent.

F��. 9. Modiolopsidae.—Shell mytiliform, ligament exterior, hingeteeth small, rather numerous. Palaeozoic——. Principal genera: Modiolopsis, Cyrtodonta, Mytilops, Ptychodesma.

F��. 10. Lucinidae.—Anal orifice sometimes with a siphon, branchial orifice complete or not, sometimes a single branchia; foot very long, vermiform, no byssus, anterior adductor long; shell rounded, equivalve, blanched, hinge with two cardinals and two laterals in each valve, sometimes toothless, ligament more or less internal. Silurian——. Principal genera: Lucina, Corbis, Axinus, Diplodonta, Montacuta.

F��. 11. Ungulinidae.—Anal orifice complete, foot vermiform, no byssus, two branchiae; shell equivalve, subcircular, hinge-teeth variable, no laterals, adductor impressions long, continuing the pallial line. Tertiary——. Single genus, Ungulina.

F��. 12. Unicardiidae.—Shell equivalve, round or oval, cardinal shelf large, a single cardinal in each valve, ligament external. Carboniferous—Cretaceous. Genera: Unicardium, Scaldia, Pseudedmondia.

F�� 13. Kellyellidae.—Anal siphon prolonged, no marked branchial orifice; shell very small, oval or round, anterior lateral very strong, under the cardinal. Eocene——. Genera: Kellyella; Allopagus and Lutetia (Tertiary), Turtonia.

F��. 14. Erycinidae.—Mantle edges with three apertures, branchial orifice on the buccal margin, foot long, broadened, with a byssus, animal usually viviparous. Tertiary——. Genera: Erycina, Kellia, Pythina, Lasaea, Lepton.

F��. 15. Galeommidae.—Mantle edges more or less reflected over the shell, apertures and foot as in Erycinidae; shell thin, equilateral, hinge with few teeth or none. Tertiary——. Genera: Galeomma, Scintilla, Sportella, Chlamydoconcha, Hindsiella, Ephippodonta (Fig. 32, p. 81).

F��. 16. Cyrenidae.—Siphons short, foot large, no byssus; shell equivalve, subtriangular, with periostracum, hinge with two or three cardinals, laterals present; animal hermaphrodite, viviparous. Fresh or brackish water. Jurassic——. Genera: Cyrena, Corbicula (subg. Batissa, Velorita), Sphaerium (= Cyclas), Pisidium, Galatea, Fischeria.

The families Cyrenellidae (single genus, Cyrenella) and Rangiidae (single genus, Rangia) are probably to be placed here.

Sub-order II. Tellinacea.—Siphons long, separate, foot and labial palps very large, pallial sinus deep, two adductor muscles.

F��. 1. Tellinidae.—External branchial fold directed dorsally, foot with byssogenous slit, but no byssus, branchiae small; shell compressed, equivalve, ligament external, at least two cardinals in each valve, laterals variable. Cretaceous——. Principal genera: Tellina (with many sections), Gastrana.

F��. 2. Scrobiculariidae.—Animal as in Tellina; shell orbiculate or long oval, equivalve, hinge-teeth weak, ligament in an internal cavity. Tertiary——. Principal genera: Scrobicularia, Syndosmya, Theora, Cumingia, Semele.

F��. 3. Donacidae.—External branchial fold directed ventrally; shell equivalve, subtriangular, solid, smooth, two or three cardinals in

each valve, laterals variable, ligament external. Jurassic——. Genera: Donax, Iphigenia, Isodonta.

F�� 306 Tellina rastellum Hanl , East Indies >

F�� 4. Tancrediidae.—Shell donaciform, ligament external, cardinals usually two in each valve, posterior laterals strong. Trias ——. Genera: Tancredia (Secondary strata), Hemidonax.

F��. 5. Cardiliidae.—Shell heart-shaped, hinge as in Mactridae, posterior adductor resting on a myophore or shelf. Single genus, Cardilia. Tertiary——.

F��. 6. Mesodesmatidae.—Mantle edges largely united, with three orifices, foot byssiferous or not; shell regular or irregular, usually one cardinal and strong lateral teeth. Tertiary——. Genera: Mesodesma, Ervilia

F��. 7. Mactridae.—External branchial fold directed ventrally, siphons fused, foot tongue-shaped; shell equivalve, triangular-oval, hinge with ligament in an internal fossette, another portion external, a bifurcated cardinal tooth in the left valve, fitting into a branching tooth in the right valve, laterals present. Jurassic——. Genera: Nactra, Harvella, Raëta, Eastonia, Heterocardia, Vanganella.

Sub-order III. Veneracea.—Branchiae slightly folded, foot compressed, siphons generally short, pallial line variable, two adductor muscles.

F��. 1. Veneridae.—Siphons free or partly united, foot seldom byssiferous; shell solid, equivalve, hinge usually with three cardinal teeth, laterals variable. Jurassic——. Principal genera: Cytherea,

Circe; Grateloupia (Tertiary), Meroe, Dosinia (= Artemis), Cyprimeria, Cyclina, Venus, Clementia, Lucinopsis; Thetis (Cretaceous), Tapes, Venerupis.

F��. 2. Petricolidae.—Animal perforating rocks; shell oval, slightly gaping behind, two or three cardinals, no laterals, pallial sinus well marked. Recent——. Genera: Petricola, Naranio.

F�� 307 Cytherea dione Lam , Peru

F�� 3. Glaucomyidae.—Siphons long, united, foot small; shell produced, thin, hinge with three cardinals, no laterals, pallial sinus well marked. Recent——. Genus, Glaucomya (incl. Tanysiphon).

Sub-order IV. Cardiacea.—Branchiae much folded back, mantle edges with three apertures, foot cylindroidal, more or less produced, siphons present or absent, one or two adductor muscles, pallial line variable.

F��. 1. Cardiidae.—Siphons rather long, foot long, no byssus; shell equivalve, more or less radiately ribbed, hinge with one or two cardinals in each valve, laterals variable, ligament external, two adductors. Brackish water or marine. Devonian——. Genera: Byssocardium and Lithocardium (Tertiary), Conocardium (Palaeozoic), Cardium (with many sections, including Hemicardium), Limnocardium (subg. Didacna, Monodacna, Adacna).

F��. 308. Cardium (Hemicardium) cardissa L., East Indies

F��. 2. Lunulicardiidae.—Shell equivalve, very inequilateral subtriangular, anterior margin short or truncated, with a deep lunule. Single genus, Lunulicardium (Palaeozoic).

F��. 3. Tridacnidae.—Mantle orifices widely separated, foot short, byssiferous, no anterior adductor; shell equivalve, large, thick, usually gaping in front, one cardinal tooth and one or two posterior laterals in each valve, no pallial sinus. Miocene——. Genera: Tridacna, Hippopus. The muscular power of the great Tridacna is immense. Once caught between their gaping valves, a man’s hand or foot can scarcely be withdrawn. Two valves of T. gigas in the British Museum weigh respectively 154 and 156 lbs.

F��. 4. Chamidae.—Mantle orifices widely separated, foot short, no byssus, both adductors present, ovary invading the mantle lobes; shell fixed, irregularly inequivalve, umbones spiral, ligament external, cardinal teeth often a mere ridge, anterior lateral strong, nearly central, no pallial sinus. Jurassic——. Genera: Chama; Diceras (Jurassic), attached by one umbo, umbones very prominent, teeth strong; Heterodiceras (Jurassic), Requienia (Cretaceous), left valve widely spiral, attached by the umbo, right valve small, fitting on the other as an operculum, teeth obsolete; Toucasia, Apricardia, Matheronia (all Secondary strata).

F��. 309. A, Requienia ammonea Goldf., Neocomian, × ½; B, Hippurites cornu-vaccinum Goldf., Cretaceous, × ¼. a, right valve; f, point of fixture. (From Zittel.)

The four succeeding families require special study in a work on Palaeontology.

F��. 5. Monopleuridae.—Shell very inequivalve, left valve operculiform, right conical or spiral, fixed at the apex, ligament prolonged in external grooves. Cretaceous——. Genera: Monopleura, Valletia.

F��. 6. Caprinidae.—Shell very inequivalve, thick, free or fixed by apex of right valve, which is spiral or conical, left valve spiral or not, often perforated by radial canals from the umbo to the free margin. Neocomian and Cretaceous——. Principal genera: Plagioptychus, Caprina, Ichthyosarcolites, Caprotina, Polyconites.

F��. 7. Hippuritidae (= Rudistae).—Shell very inequivalve, externally as in Caprinidae, umbo central in left valve, no ligament proper, left valve with strong hinge-teeth and grooves, two adductor impressions on prominent myophores, shell structure of the two valves differing. Cretaceous only. Single genus, Hippurites (Fig. 309, B).

F�� 8. Radiolitidae.—Shell inversely conical, biconical, or cylindrical, general aspect of Hippurites, umbo of left valve central or lateral, right valve with a thick outer layer, often foliaceous, umbonal cavity partitioned off by laminae. Cretaceous only. Genera: Radiolites, Biradiolites.

Sub-order V. Myacea.—Branchiae much folded back, mantle edges usually with three openings, foot compressed, siphons large, united or not, two adductor muscles, pallial line variable.

F��. 1. Psammobiidae.—Siphons long, not united, foot large, not byssiferous; shell equivalve, long, oval, slightly gaping at the ends, ligament external, prominent, two cardinal teeth in each valve, no laterals, a deep pallial sinus. Jurassic——. Genera: Psammobia, Solenotellina, Sanguinolaria, Asaphis, Elizia, Quenstedtia (Jurassic).

F��. 2. Myidae.—Pedal orifice small, siphons long, united in great part; shell inequivalve, gaping at one or both ends, periostracum more or less extensive, ligament internal, resting on a prominent shelf; hinge-teeth variable. Cretaceous——. Genera: Mya, Tugonia, Sphenia, Corbula, Lutraria (for which latter some propose a separate family).

F��. 3. Solenidae.—Foot long, powerful, more or less cylindrical, no byssus, siphons usually short, united or not, branchiae narrow; shell equivalve, long and narrow, gaping at both ends, with periostracum, umbones flattened, ligament external, hinge-teeth variable.? Devonian——. Genera: Solecurtus, Pharella, Pharus, Cultellus, Siliqua, Ensis, Solen, Orthonota (?), Palaeosolen (?).

F��. 4. Glycimeridae.—Pedal orifice very narrow, siphons long, united in great part, often covered with periostracum; shell more or less equivalve, gaping at both ends, hinge toothless or with two weak cardinals, ligament external; animal free or perforating. Cretaceous——. Genera: Glycimeris, Saxicava, Cyrtodaria.

F��. 5. Gastrochaenidae.—Foot small, cylindrical, no byssus, branchiae narrow, siphons long; shell perforating or cemented to a shelly tube, gaping widely on the anterior and ventral sides, no hinge-teeth, a deep pallial sinus. Cretaceous——. Genera:

Gastrochaena, Fistulana (tube with a median diaphragm, perforated by the siphons).

Sub-order VI. Pholadacea.—Mantle edges largely closed, siphons long, united, foot short, truncated, disc-shaped, ligament absent, two adductor muscles; animal perforating.

F��. 1. Pholadidae.—Organs contained within the valves, ctenidia prolonged into the branchial siphon, shell more or less gaping, thin, dorsal margin in part reflected over the umbones, one or more dorsal accessory pieces, no hinge-teeth, an interior apophysis proceeding from the umbonal cavity Jurassic——. Genera: Pholas, Talona, Pholadidea (posterior extremity of the valves prolonged by a corneous appendage, a passage to the long tube of Teredo), Jouannetia, Xylophaga, Martesia; Teredina (Eocene).

F�� 310 Teredo navalis L : V, valves of shell; T, tube; P, pallets; SS, siphons (After Möbius )

F�� 2. Teredinidae.—Animal vermiform, ctenidia mainly within the branchial siphon, siphons very long, with two calcareous appendages (“pallets”) near the anterior end, shell very small, continued into a long calcareous tube, valves deeply notched, internal apophysis as in Pholadidae. Lias——. Single genus, Teredo (Fig. 310).

Sub-order VII. Anatinacea.—External branchial fold directed dorsally, not reflected, sexes united, ovaries and testes with separate orifices, mantle edges largely united, byssus usually absent, two adductor muscles, pallial line variable, shell usually nacreous within.

F�� 1. Pandoridae.—Siphons short, largely united, foot tongueshaped; shell free or fixed, inequivalve, semi-lunar, or subtriangular, ligament often with calcareous ossicle, pallial line complete or with slight sinus. Cretaceous——. Genera: Pandora, Myodora, Myochama.

F��. 2. Chamostreidae.—Shell fixed, Chama-like, thick, umbones spiral, ligament with ossicle. Single genus, Chamostrea.

F��. 3. Verticordiidae.—Siphons not prolonged; shell heartshaped, umbones prominent, spiral, ligament with an ossicle, pallial line complete. Miocene——. Genera: Verticordia, Mytilimeria, Lyonsiella.

F��. 4. Lyonsiidae.—Foot short, byssiferous, siphons short, separate, shell inequivalve, hinge-teeth usually absent, ligament and ossicle in an internal groove. Eocene——. Single genus, Lyonsia.

F�� 311 Myochama

Stutchburyi A Ad , attached to Circe undatina Lam , Moreton Bay

F��. 5. Ceromyidae.—Shell inequivalve, large, heart- or wedgeshaped, hinge toothless, ligament internal in one valve, external in the other. Secondary strata——. Genera: Ceromya, Gresslya.

F��. 6. Arcomyidae.—Shell equivalve, thin, surface finely granulated, hinge toothless, cardinal edge dentiform, ligament