The Composition of

Life, Concise 6th Edition John Mauk

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/the-composition-of-everyday-life-concise-6th-edition-j ohn-mauk/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Biota

Grow 2C gather 2C cook Loucas

https://textbookfull.com/product/biota-grow-2c-gather-2c-cookloucas/

The Everyday Life of an Algorithm Daniel Neyland

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-everyday-life-of-analgorithm-daniel-neyland/

The Lean Book of Lean: A Concise Guide to Lean Management for Life and Business 1st Edition John Earley

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-lean-book-of-lean-a-conciseguide-to-lean-management-for-life-and-business-1st-edition-johnearley/

CEO society the corporate takeover of everyday life Bloom

https://textbookfull.com/product/ceo-society-the-corporatetakeover-of-everyday-life-bloom/

Social Psychology: The Science of Everyday Life 2nd Edition Jeff Greenberg

https://textbookfull.com/product/social-psychology-the-scienceof-everyday-life-2nd-edition-jeff-greenberg/

Foundational Economy The Infrastructure of Everyday Life The Foundational Economy Collective

https://textbookfull.com/product/foundational-economy-theinfrastructure-of-everyday-life-the-foundational-economycollective/

Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life (12th Edition) David M Newman

https://textbookfull.com/product/sociology-exploring-thearchitecture-of-everyday-life-12th-edition-david-m-newman/

The Palgrave Handbook of Everyday Digital Life 1st Edition Hopeton S. Dunn

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-palgrave-handbook-ofeveryday-digital-life-1st-edition-hopeton-s-dunn/

The Palgrave Handbook of Everyday Digital Life 3rd Edition Irving M. Shapiro

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-palgrave-handbook-ofeveryday-digital-life-3rd-edition-irving-m-shapiro/

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

different from th and t but still clearly allied, since it also is made by the tongue against the teeth. D is a stop like t, but the vocal cords vibrate while it is being pronounced, whereas in t the vocal cords are silent. D is “voiced” or “sonant,” t “unvoiced” or “surd.” Hence the formulation: Latin, surd stop; German, sonant stop; English, fricative. This triple equivalence can be substantiated in other words. For instance, ten-uis, dünn, thin; tu, du, thou.

If it is the English word that contains a surd stop, what will be the equivalent in Latin and German? Compare ten, Latin decem, German zehn. Again the three classes of sounds run parallel; but the place of their appearance in the three languages has shifted.

The third possible placing of the three sounds in the three languages is when English has the sonant stop, d. By exclusion it might be predicted that Latin should then show the fricative th and German the surd stop t. The word daughter confirms. The German is tochter. Latin in this case fails us, the original corresponding stem having gone out of use and been replaced by the word filia. But Greek, whose sounds align with those of Latin as opposed to English and German, provides the th as expected: thygater Compare death, tod, thanatos.

Let us bring together these results so that the eye may grasp them:

Latin, Greek surd stop sonant stop fricative

German sonant stop fricative surd stop

English fricative surd stop sonant stop

Latin, Greek tres duo thygater

German drei zwei tochter

English three two daughter

These relations apply not only to the dentals d, t, th (z), which have been chosen for illustration, but also to the labials, p, b, f, and to the palatals k, g, h (gh, ch).

It is evident that most of the sounds occur in all three groups of languages, but not in the same words. The sound t is common to English, Latin, and German, but when it appears in a particular word in one of these languages it is replaced by d and th in the two others. This replacing is known as a “sound shift.” The sound shifts just enumerated constitute the famous Grimm’s Law. This was the first discovered important phonetic law or system of sound substitutions. Yet it is only one of a number of shifts that have been worked out for the Indo-European group of languages to which English, German, and Latin belong. So far, only stopped and fricative consonants have been reviewed here, and no vowels have been considered. Other groups of languages also show shifts, but often different ones, as between l and n, or s and k, or p and k.

The significance of a shift lies in the fact that its regularity cannot be explained on any other ground than that the words in which the law is operative must originally have been the same. That is, Latin duo, German zwei, English two are all only variants of a word which meant “two” in the mother tongue from which these three languages are descended. This example alone is of course insufficient evidence for the existence of such a common mother tongue. But that each of the shifts discussed is substantiated by hundreds or thousands of words in which it holds true, puts the shift beyond the possibility of mere accident. The explanation of coincidence is ruled out. The resemblances therefore are both genuine and genetic. The conclusion becomes inevitable that the languages thus linked are later modifications of a former single speech.

It is in this way that linguistic relationship is determined. Where an ancient sound shift, a law of phonetic change, can be established by a sufficient number of cases, argument ceases. It is true that when most of a language has perished, or when an unwritten language has been but fragmentarily recorded or its analysis not carried far, a strong presumption of genetic unity may crowd in on the investigator who is not yet in a position to present the evidence of laws. The indications may be strong enough to warrant a tentative assumption of relationship. But the final test is always the establishment of laws of sound equivalence that hold good with predominating regularity.

50. T�� P�������� S�����

F�������

The number of linguistic families is not a matter of much theoretical import. From what has already been said it appears that the number can perhaps never be determined with absolute accuracy. As knowledge accumulates and dissection is carried to greater refinements, new phonetic laws will uncover and serve to unite what now seem to be separate stocks. Yet for the practical purpose of classification and tracing relationship the linguistic family will remain a valuable tool. A rapid survey of the principal families is therefore worth while.

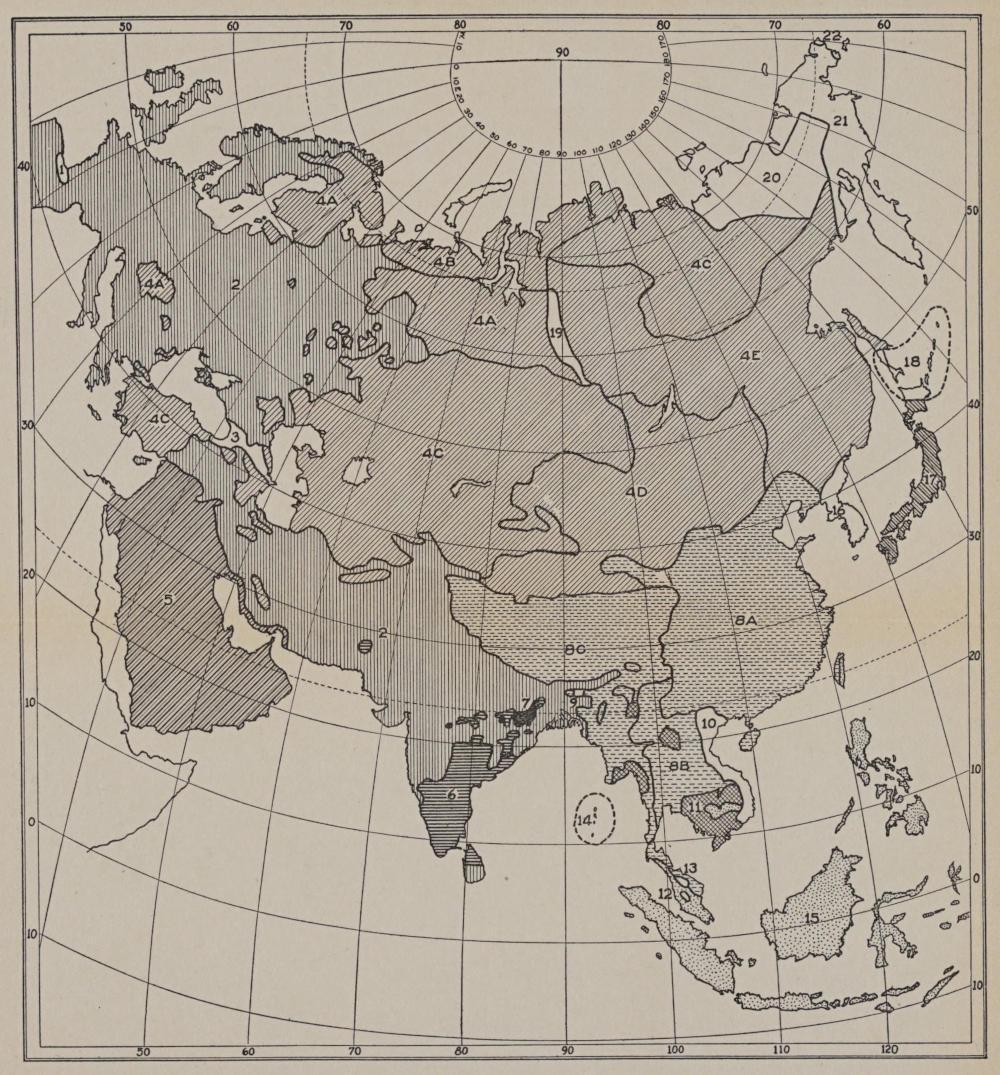

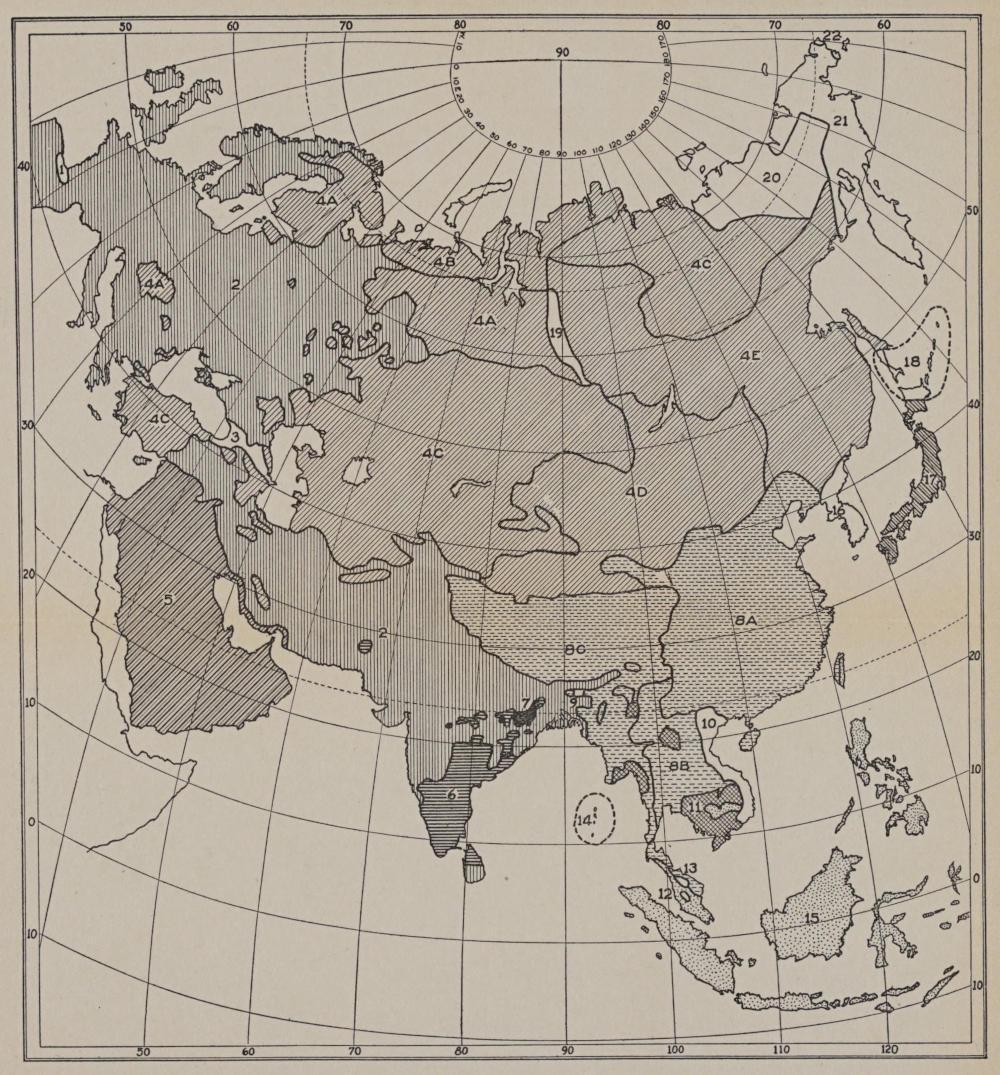

F��. 12. Linguistic Families of Asia and Europe. 1, Basque. 2, Indo-European. 3, Caucasian (perhaps two families). 4, Ural-Altaic (a, Finno-Ugric; b, Samoyed; c, Turkish; d, Mongol; e, Tungus-Manchu). 5, Semitic. 6, Dravidian. 7, Kolarian. 8, Sinitic (a, Chinese; b, Shan-Siamese; c, Tibeto-Burman). 9, Khasi. 10, Anamese. 11, Mon-Khmer. 12, Sakai. 13, Semang. 14, Andaman. 15, Malayo-Polynesian. 16, Korean. 17, Japanese. 18, Ainu. 19, Yeniseian. 20, Yukaghir. 21, Chukchi-Kamchadal. 22, Eskimo.

In Asia and Europe, which must be considered a unit in this connection, the number of stocks, according to conservative reckoning, does not exceed twenty-five. The most important of these, in point of number of speakers, is the Indo-European or IndoGermanic or Aryan family, whose territory for several thousand years has comprised southwestern Asia and the greater part, but by no means all, of Europe. The most populous branches of the IndoEuropean family are the Indic, Slavic, Germanic, and Romance or Latin. Others are Persian or Iranic, Armenian, Greek, Albanian, Baltic or Lithuanian, and Keltic. From Europe various Indo-European languages, such as English, Spanish, French, Russian, have in recent centuries been carried to other continents, until in some, such as the Americas and Australia, the greater area is now inhabited by peoples speaking Indo-European. As the accompanying maps are intended to depict the historic or native distribution of languages they do not show this diffusion. It will be noted that the distribution of Indo-European has the form of a long belt stretching from western Europe to northeastern India, with an interruption only in Asia Minor (Fig. 12). Turkish peoples displaced Indo-Europeans there about a thousand years ago, thus breaking the territorial continuity. It is probable that another link between the western and eastern IndoEuropeans once stretched around the north of the Caspian sea. Here also there are Turks now.

Almost equaling Indo-European in the number of its speakers is Sinitic, which is generally held to include Chinese proper with its dialects; the Tibeto-Burman branch; the T’ai or Shan-Siamese branch; and probably some minor divisions like Lolo.

In extent of territory occupied the Altaic stock rivals the IndoEuropean. Its three main divisions, Turkish, Mongolian, and TungusManchu, cover most of northern and central Asia and some tracts in Europe. The Turks, as just noted, are the only stock that within the period of history has gained appreciable territory at Indo-European expense. The Uralic or Finno-Ugric family has eastern Europe and northwestern Asia as its home, with the Finns and Hungarian Magyars as its most civilized and best known representatives. This is

a scattered stock. Most scholars unite the three Altaic divisions, Finno-Ugric, and Samoyed into a vast Ural-Altaic family.

Of the Semitic family, Arabic is the chief living representative, with Abyssinian in Africa as a little known half-sister. Arabic is one of the most widely diffused of all languages, and as the orthodox vehicle of Mohammedanism has served an important function as a culture carrier. Several great nations of ancient times also spoke Semitic tongues: the Babylonians, Assyrians, Phœnicians, Carthaginians, and Hebrews.

Southern India is Dravidian. While people of this family enter little into our customary thoughts, they number over fifty millions. Japanese and Korean also merit mention as important stock tongues. Anamese, by some regarded as an offshoot from Chinese, may constitute a separate stock. Several minor families will be found on the Asiatic map, most of them consisting of uncivilized peoples or limited in their territory or the number of their speakers. Yet, so far as can be judged from present knowledge, they form units of the same order of independence as the great Indo-European, Semitic, and Ural-Altaic stocks.

Language distributions in Africa are in the main simple (Fig. 13). The whole of northern Africa beyond latitude 10°, and parts of east Africa almost to the equator, were at one time Hamitic. This is the family to which the language of ancient Egypt belonged. Hamitic and Semitic, named after sons of Noah, probably derive from a common source, although the separation of the common mother tongue into the African Hamitic and the Asiatic Semitic divisions must have occurred very anciently. In the past thousand years Hamitic has yielded ground before Semitic, due to the spread of Arabic in Mohammedan Africa.

Africa south of the equator is the home of the great Bantu family, except in the extreme southwest of the continent. There a tract of considerable area, though of small populational density, was in the possession of the backward Bushmen and Hottentots, distinctive in their physical type as well as languages.

F��. 13. Linguistic Families of Africa. 1, Hamitic. 2, Semitic (a, old; b, intrusive in former Hamitic territory since Mohammed). 3, Bantu. 4, Hottentot. 5, Bushman. 6, Malayo-Polynesian. X, the Sudan, not consistently classified.

Between the equator and latitude ten north, in the belt known as the Sudan, there is much greater speech diversity than elsewhere in Africa. The languages of the Sudan fall into several families, perhaps

into a fairly large number Opinion conflicts or is unsettled as to their classification. They are, at least in the main, non-Hamitic and nonBantu; but this negative fact does not preclude their having had either a single or a dozen origins. It has usually been easier to throw them all into a vague group designated as non-Hamitic and nonBantu than to compare them in detail.

In Oceania conditions are similar to those of Africa, in that there are a few great, widely branching stocks and one rather small area, New Guinea, of astounding speech diversity. Indeed, superficially this variety is the outstanding linguistic feature of New Guinea. The hundreds of Papuan dialects of the island look as if they might require twenty or more families to accommodate them. However, it is inconceivable that so small a population should time and again have evolved totally new forms of speech. It is much more likely that something in the mode of life or habits of mind of the Papuans has favored the breaking up of their speech into local dialects and an unusually rapid modification of these into markedly differentiated languages. What the circumstances were that favored this tendency to segregation and change can be only conjectured. At any rate, New Guinea ranks with the Sudan, western North America, and the Amazonian region of South America, as one of the areas of greatest linguistic multiplicity.

All the remainder of Oceania is either Australian or MalayoPolynesian in speech. The Australian idioms have been imperfectly recorded. They were numerous and locally much varied, but seem to derive from a single mother tongue.

All the East Indies, including part of the Malay Peninsula, and all of the island world of the Pacific—Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia—always excepting interior New Guinea—are the habitat of the closely-knit Malayo-Polynesian family, whose unity was quickly recognized by philologists. From Madagascar to Easter Island this speech stretches more than half-way around our planet. Some authorities believe that the Mon-Khmer languages of southern IndoChina and the Kolarian or Munda-Kol tongues of India are related in origin to Malayo-Polynesian, and denominate the larger whole, the Austronesian family.

F��. 14. Some important linguistic families of North America: 1, Eskimo; 2, Athabascan; 3, Algonkin; 4, Iroquoian; 5, Siouan; 6, Muskogean; 7, UtoAztecan; 8, Mayan. SA1, Arawak, No. 1 on South American map (Fig. 15). SA8, Chibcha, No. 8 on South American map. The white areas are occupied by nearly seventy smaller families, according to the classification usually accepted.

North and South America, according to the usual reckoning, contain more native language families than all the remainder of the world. The orthodox classification allots about seventy-five families to North America (some fifty of them represented within the borders of the United States) and another seventy-five to South America. They varied greatly in size at the time of discovery, some being confined to a few hundred souls, whereas others stretched through tribe after tribe over enormous areas. Their distribution is so irregular and their areas so disproportionate as to be impossible of vivid representation except on a large-scale map in colors. The most important in extent of territory, number of speakers, or the cultural importance of the nations adhering to them, are, in North America, Eskimo, Athabascan, Algonkin, Iroquoian, Muskogean, Siouan, UtoAztecan, Maya; and in South America, Chibcha, Quechua, Aymara, Araucanian, Arawak, Carib, Tupi, Tapuya. It will be seen on the maps (Figs. 14, 15) that these sixteen groups held the greater part of the area of the double continent, the remaining smaller areas being crowded with about ten times as many stocks. Obviously, as in New Guinea, there cannot well have been such an original multiplicity; in fact, recent studies are tending to consolidate the hundred and fifty New World families into considerably fewer groups. But the evidence for such reductions is necessarily difficult to bring and much of it is still incomplete. The stocks mentioned above have been long determined and generally accepted.

About a third of humanity to-day speaks some form of IndoEuropean. A quarter talks some dialect of Sinitic stock. Semitic, Dravidian, Ural-Altaic, Japanese, Malayo-Polynesian, Bantu have each from about fifty to a hundred million speakers. The languages included in these eight families form the speech of approximately ninety per cent of living human beings.

51. C������������� �� L�������� �� T����

A classification is widely prevalent which puts languages according to their structure into three types: inflective, agglutinating, and isolating. To this some add a fourth type, the polysynthetic or

incorporating. While the classification is largely misrepresentative, it enters so abundantly into current thought about human speech that it is worth presenting, analyzing, and, so far as it is invalid, refuting.

F��. 15. Some important linguistic families of South America: 1, Arawak; 2, Carib; 3, Tapuya; 4, Tupi; 5, Araucanian; 6, Aymara; 7, Quechua (Inca); 8, Chibcha.

The white areas are occupied by about seventy smaller families, according to the usually accepted classification. (Based on Chamberlain.)

An inflecting language expresses relations or grammatical form by adding prefixes or suffixes which cannot stand alone, or if they stood alone would mean nothing; or that operates by internal modifications of the stem, which also can have no independent existence. The -ing of killing is such an inflection; so are the vowel changes and the ending -en in the conjugation write, wrote, written.

An isolating language expresses such relations or forms by separate words or isolated particles. English heart of man is isolating, where the Latin equivalent cor hominis is inflective, the per se meaningless suffix -is rendering the genitive or possessive force of the English word of.

An agglutinative language glues together into solid words elements for which a definite meaning of their own can be traced. English does not use this mechanism for purposes that are ordinarily reckoned as strictly grammatical, but does employ it for closely related purposes. Under-take, rest-less, are examples; and in a form like light-ly, which goes back to light-like, the force of the suffix which converts the adjective into the adverb is of a kind that in descriptions of most languages would be considered grammatical or formal.

Polysynthetic languages are agglutinative ones carried to a high pitch, or those that can compound words into equivalents of fair sized sentences. Steam-boat-propeller-blade might be called a polysynthetic form if we spoke or wrote it in one word as modern German and ancient Greek would.

Incorporating languages embody the object noun, or the pronoun representing it, into the word that contains the verb stem. This construction is totally foreign to English.[7]

Each of these classes evidently defines one or more distinctive linguistic processes. There are different mechanisms at work in killing, of man, light-ly. The distinction is therefore both valid and valuable. Its abuse lies in trying to slap the label of one type on a whole language. The instances given show that English employs

most of the several distinct processes. Obviously it would be arbitrary to classify English as outright of one type. This is also the situation for most other languages. There are a few languages that tend prevailingly in one direction or the other: Sanskrit and Latin and Hebrew toward the inflective structure, Turkish toward the agglutinative, Chinese toward the isolating. But they form a small minority, and most of them contain certain processes of types other than their predominating ones. Sanskrit, for instance, has polysynthetic traits, Hebrew incorporating ones. Therefore, so long as these concepts are used to picture a language in detail, with balanced recognition of the different processes employed by it, they are valuable tools to philological description. When on the other hand the concepts are degraded into catchwords designating three or four compartments into one of which every language is somehow to be stuffed, they grossly misrepresent most of the facts. The concepts, in short, apply usefully to types of linguistic processes, inadequately to types of languages.

Why then has the classification of human languages into inflecting, agglutinating, isolating, and polysynthetic or incorporating ones been repeated so often? First of all, because languages vary almost infinitely, and a true or natural classification, other than the genetic one into families, is intricate. The mind craves simplicity and the three or four supposedly all-embracing types are a temptation.

A second reason lies deeper. As philology grew up into a systematic body of knowledge, it centered its first interests on Latin and Greek, then on Sanskrit and the other older Indo-European languages. These happened to have inflective processes unusually well developed. They also happened to be the languages from which the native speech of the philologists was derived. What is our own seems good to us; consequently Indo-European was elevated into the highest or inflective class of languages. As a sort of afterthought, Semitic, which includes Hebrew, the language of part of our Scriptures, was included. Then Chinese, which follows an unusually simple plan of structure that is the opposite in many ways of the complex structure of old Indo-European, and which was the speech of a civilized people, was set apart as a class of the second rank.

This left the majority of human languages to be dumped into a third class, or a third and fourth class, with the pleasing implication that they were less capable of abstraction, more materialistic, cruder, and generally inferior. Philologists are customarily regarded as extreme examples of passionless, dry, objective human beings. The history of this philological classification indicates that they too are influenced by emotional and self-complacent impulses.

52. P��������� �� L������� ��� R���

It is sometimes thought because a new language is readily learned, especially in youth, that language is a relatively unstable factor in human history, less permanent than race. It is necessary to guard against two fallacies in this connection. The first is to argue from individuals to societies; the second, that because change is possible, it takes place.

As a matter of fact, languages often preserve their existence, and even their territory, with surprising tenacity in the face of conquest, new religions and culture, and the economic disadvantages of unintelligibility. To-day, Breton, a Keltic dialect, maintains itself in France as the every-day language of the people in the isolated province of Brittany—a sort of philological fossil. It has withstood the influence of two thousand years of contact, first with Latin, then with Frankish German, at last with French. Its Welsh sister-tongue flourishes in spite of the Anglo-Saxon speech of the remainder of Great Britain. The original inhabitants of Spain were mostly of nonAryan stock. Keltic, Roman, and Gothic invasions have successively swept over them and finally left the language of the country Romance, but the original speech also survives the vicissitudes of thousands of years and is still spoken in the western Pyrenees as Basque. Ancient Egypt was conquered by the Hyksos, the Assyrian, the Persian, the Macedonian, and the Roman, but whatever the official speech of the ruling class, the people continued to speak Egyptian. Finally, the Arab came and brought with him a new religion, which entailed use of the Arabic language. Egypt has at last become Arabic-speaking, but until a century or two ago the Coptic

language, the daughter of the ancient Egyptian tongue of five thousand years ago, was kept alive by the native Christians along the Nile, and even to-day it survives in ritual. The boundary between French on the one side and German, Dutch, and Flemish on the other, has been accurately known for over six hundred years. With all the wars and conquests back and forth across the speech line, endless political changes and cultural influences, this line has scarcely anywhere shifted more than a few dozen miles, and in places has not moved by a comfortable afternoon’s stroll.

While populations can learn and unlearn languages, they tend to do so with reluctance and infinite slowness, especially while they remain in their inherited territories. Speech tends to be one of the most persistent ethnic characters.

In general, where two populations mingle, the speech of the more numerous prevails, even if it be the subject nationality. A wide gap in culture may overcome the influence of the majority, yet the speech of a culturally more active and advanced population ordinarily wrests permanent territory to itself slowly except where there is an actual crowding out or numerical swamping of the natives. This explains the numerous survivals and “islands” of speech: Keltic, Albanian, Basque, Caucasian, in Europe; Dravidian and Kolarian in India; Nahuatl and Maya and many others in modern Mexico; Quechua in Peru; Aymara in Bolivia; Tupi in Brazil. There are cases to the contrary, like the rapid spread of Latin in most of Gaul after Cæsar’s conquest, but they seem exceptional.

As to the relative permanence of race and speech, everything depends on the side from which the question is approached. From the point of view of hereditary strains, race must be the more conservative, because it can change rapidly only through admixture with another race, whereas a language may be completely exchanged in a short time. From the point of view of history, however, which regards human actions within given territories, speech is often more stable. Wars or trade or migration may bring one racial element after another into an area until the type has become altered or diluted, and yet the original language, or one directly descended from it, remains. The introduction of the negro

from Africa to America illustrates this distinction. From the point of view of biology, the negro has at least partially preserved his type, although he has taken on a wholly new language. As a matter of history, the reverse is true: English continues to be the speech of the southern United States, whereas the population now consists of two races instead of one, and the negro element has been altered by the infusion of white blood. It is a fallacy to think, because one can learn French or become a Christian and yet is powerless to change his eye color or head shape, that language and culture are altogether less stable than race. Speech and culture have an existence of their own, whose integrity does not depend on hereditary integrity. The two may move together or separately.

53. T��

P������� �� ��� R������� �� L������� ���

C������

This association of language and civilization, or let us say the linguistic and non-linguistic constituents of culture, brings up the problem whether it would be possible for one to exist without the other. Actually, of course, no such case is known. Speculatively, different conclusions might be reached. It is difficult to imagine any generalized thinking taking place without words or symbols derived from words. Religious beliefs and certain phases of social organization also seem dependent on speech: caste ranking, marriage regulations, kinship recognition, law, and the like. On the other hand, it is conceivable that a considerable series of inventions might be made, and the applied arts might be developed in a fair measure by imitation, among a speechless people. Finally there seems no reason why certain elements of culture, such as music, should not flourish as successfully in a society without as with language.

For the converse, a cultureless species of animal might conceivably develop and use a form of true speech. Such communications as “The river is rising,” “Bite it off,” “What do you find inside?” would be within the range of thought of such a species. Why then have even the most intelligent of the brutes failed to

develop a language? Possibly because such a language would lack a definite survival value for the species, in the absence of accompanying culture.

On the whole, however, it would seem that language and culture rest, in a way which is not yet fully understood, on the same set of faculties, and that these, for some reason that is still more obscure, developed in the ancestors of man, while remaining in abeyance in other species. Even the anthropoid apes seem virtually devoid of the impulse to communicate, in spite of freely expressing their affective states of mind by voice, facial gesture, and bodily movement. The most responsive to man of all species, the dog, learns to accept a considerable stock of culture in the sense of fitting himself to it: he develops conscience and manners, for example. Yet, however highly bred, he does not hand on his accomplishments to his progeny, who again depend on their human masters for what they acquire. A group of the best reared dogs left to themselves for a few years would lose all their politeness and revert to the predomestic habits of their species. In short, the culture impulse is lacking in the dog except so far as it is instilled by man; and in most animals it can notoriously be instilled only to a very limited degree. In the same way, the impulse toward communication can be said to be wanting. A dog may understand a hundred words of command and express in his behavior fifty shades of emotion; only rarely does he seem to try to communicate information of objective fact. Very likely we are attributing to him even in these rare cases the impulse which we should feel. In the event of a member of the family being injured or lost, it is certain that a good dog expresses his agitation, uneasiness, disturbed attachment; but much less certain is it that he intends to summon help, as we spontaneously incline to believe because such summoning would be our own reaction to the situation.

The history and causes of the development in incipient man of the group of traits that may be called the faculties for speech and civilization remain one of the darkest areas in the field of knowledge. It is plain that these faculties lie essentially in the sphere of what is ordinarily called the mind, rather than in the body, since men and the apes are far more similar in their general physiques than they are in

the degree of their ability to use their physiques for non-physiological purposes. Or, if this antithesis of physical and mental seem unfortunate, it might be said that the growth of the faculties for speech and culture was connected more with special developments of the central nervous system than with those of the remainder of the body.

55. P����� �� ��� O����� �� L�������

Is, then, human language as old as culture? It is difficult to be positive, because words perish like beliefs and institutions, whereas stone tools endure as direct evidence. On the whole, however, it would appear that the first rudiments of what deserves to be called language are about as ancient as the first culture manifestations, not only because of the theoretically close association of the two phases, but in the light of circumstantial testimony, namely the skull interiors of fossil men. In Piltdown as well as Neandertal man, those brain cortex areas in which the nervous activities connected with auditory and motor speech are most centralized in modern man, are fairly well developed, as shown by casts of the skull interiors, which conform closely to the brain surface. The general frontal region, the largest area of the cortex believed to be devoted to associative functions—in loose parlance, to thought—is also greater than in any known ape. More than one authority has therefore felt justified in attributing speech to the ancestors of man that lived well back in the Pleistocene. The lower jaws of Piltdown and in a measure of Heidelberg man, it is true, are narrow and chinless, thus leaving somewhat less free play to the tongue than living human races enjoy. But this factor is probably of less importance than the one of mental facultative development. The parrot is lipless and yet can reproduce the sounds of human speech. What he lacks is language faculty; and this, it seems, fossil man already had in some measure.

56. C������, S�����, ��� N����������