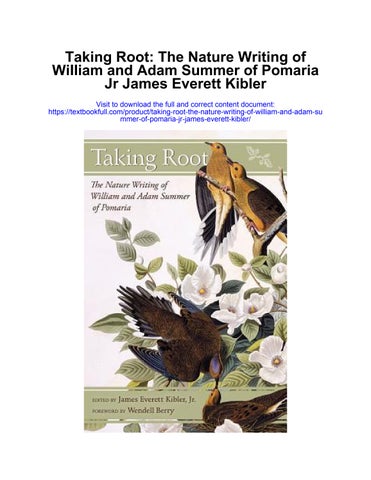

d Taking Root

The Nature Writing of William and Adam Summer of Pomaria

EditEd by

James Everett Kibler, Jr.

ForEword by

Wendell Berry

The University of South Carolina Press

© 2017 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press Columbia, South Carolina 29208 www.sc.edu/uscpress

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-774-9 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-775-6 (ebook)

Front cover image: Birds of America. Carolina Turtle Dove (Columba Carolinensis), 1838, John James Audubon (1785–1851). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Contents

Foreword c ix

Wendell Berry

Preface c xi

A Note on the Text c xix

Introduction c xxi

[A Winter Reverie] c 1

A Wish c 2

The Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus Tuberosus, Linn.) c 2

The Culture of the Sweet Potatoe c 4

The Season: Some Thoughts Grouped after Spending a Day in the Country c 9

Natural Angling, or Riding a Sturgeon c 12

The Season c 17

A Day on the Mohawk c 19

Farm Management; or Practical Hints to a Young Beginner c 24

The Vegetable Shirt-Tail; or, An Excuse for Backing Out c 32

Autumn c 35

Winter Green: A Tale of My School Master c 38

A Chapter on Live Fences c 43

Report on Wheat c 47

The Misletoe c 52

Address Delivered before the Southern Central Agricultural Society at Macon, Georgia, October 4 [20], 1852 c 53

The Character of the Pomologist c 70

The Flower Garden [I] c 72

Plants Adapted to Soiling in the South c 74

Plant a Tree c 78

A Plea for the Birds c 82

Southern Architecture—Location of Homes—Rural Adornment, &c c 83

Plant Peas c 87

The Forest Trees of the South.—No. 1 c 87

Forest Trees of the South. No. 2.—the Live Oak— (Quercus sempervirens) c 91

Forest Trees of the South. [No. 3.] the Willow Oak. Quercus Phellos c 93

One Hour at the New York Farmer’s Club c 95

Flowers c 98

Satisfactory Results from Systematic Farming—True Farmer-Planter c 99

The Crysanthemum c 101

Saving Seed c 102

Roger Sherman’s Plow c 103

“The Earth Is Wearing Out” c 105

A Rare Present.—Carolina Oranges c 106

Agricultural Humbugs and Fowl Fancies c 109

A Short Chapter on Milk Cows c 110

A Plea for Broomsedge c 112

A Visit from April c 113

We Cultivate Too Much Land c 116

The Proper Implements for Composting Manures: A Picture in Relief c 118

An Editorial Drive: What We Saw during One Morning c 119

What Should Be the Chief Crops of the South? c 123

Northern Horses in Southern Cities c 125

Scuppernong Wine c 126

A Good Native Hedge Plant for the South c 128

Soap Suds c 129

The Best Mode of Stopping Ditches and Washes c 130

Cherries c 131

Amelanchier: New Southern Fruit c 133

China Berries c 134

Barefooted Notes on Southern Agriculture. No I c 135

Chinese Sugar Cane c 138

Cows and Butter: A Delightful Theme c 140

Neglect of Family Cemeteries c 143

The Destruction of Forests and Its Influence upon Climate & Agriculture c 146

New and Rare Trees of Mexico c 147

The United States Patent Office Reports, and Government Impositions c 150

Barefooted Notes on Southern Agriculture. No III c 153

The Guardians of the Patent Office c 155

New and Rare Trees and Plants of Mexico. No 2 c 156

A Transplanted Pleasure c 158

China Roses and Other Hedge-Plants in the South c 159

Barefooted Notes on Southern Agriculture. No IV c 161

Farm Economies c 166

Hill-Side Ditching c 168

Landscape Gardening c 170

New and Cheap Food for Bees c 173

The Profession of Agriculture c 175

“Bell Ringing” c 177

“Spare the Birds” c 178

Essay on Reforesting the Country c 180

Spanish Chesnuts, Madeira Nuts, etc. c 187

The Grape: Culture and Pruning c 188

Advantages of Trees c 190

“How to Get Up Hill” c 191

Barefooted Notes on Southern Agriculture. No VI c 192

Sheep Husbandry c 195

Dogs vs. Sheep c 197

Fences c 199

Sweets for the People c 201

Barefooted Notes on Southern Agriculture. No VIII c 203

Peeps over the Fence [1] c 206

Beneficial Effects of Flower Culture c 207

Peeps over the Fence [2] c 209

Fortune’s Double Cape Jessamine: (Gardenia Fortunii) c 211

Wood Economy c 212

Peeps over the Fence [3] c 213

Home as a “Summer Resort” c 215

Frankincense a Humbug and Cure for Saddle Galls c 216

Who Are Our Benefactors? c 217

Peeps over the Fence [4] c 219

Mrs. Rion’s Southern Florist c 220

Dew and Frost c 221

The Flower Garden [II] c 222

Farmer Gripe and the Flowers c 227

Pea Vine Hay c 228

Our Resources c 229

Works Cited and Consulted c 233

Index c 243

Foreword

WEndEll BErry

Not so long ago, this book would have been seen by almost everybody as work of minor academic interest: peripherally historical and fringily literary. Now I believe it will find many readers who will recognize it for what it is: a collection of observations, judgments, and instructions permanently useful to anybody interested—and to anybody not yet interested—in the right ways of inhabiting, using, and conserving the natural, the given, world.

The authors—the two brothers, Adam and William Summer—were South Carolinians of the Nineteenth Century, but they are not, for that reason, eligible to be stereotyped and dismissed. They were literate and accomplished writers who wrote essays for agricultural journals. They were horticulturists: Pomaria Nurseries, founded by William, offered 1,200 varieties of fruit trees and vines. They were farmers and students of farming, of crops and livestock, their knowledge both scientific and familiar. They were sound critics of farming and of human landscapes, their standards taken properly from the natural world and from Nature, the common mother of all us creatures, the Great Dame herself. By those standards they were strenuously indignant in the presence of any abuse of the land, and they were clearly in love with the works of Nature and of good farmers. The work gathered here was written in the two decades immediately preceding the Civil War. It has a whole-heartedness and a tone of good cheer that seem to have been irrecoverable anywhere in our country since that war and the triumph of industrialism and finance that followed it.

Why should a book so much about farming be called “nature writing”? To most conservationists of our time, who seem to have read and thought no further than John Muir, the only conservation of interest is wilderness conservation. But of course farming and nature are inseparable. Thinking about one leads necessarily to thinking about the other, and this is obvious to anybody who undertakes to think fully and carefully about either one.

Farming takes place in the natural world. Where else? It depends absolutely upon the natural endowment of topsoil and soil fertility, which were being

And so the Summer brothers, as good naturalists, naturally worried about the health of the land. There was already then too much land abuse, too much rape of Nature. Too much land was in cultivation, as now. Too much was wasted, eroded, neglected, exhausted. And so Adam Summer wrote of the importance of trees, of woodlands. And so he wrote in praise of broomsedge, a “weed,” which he recognized as necessary to the renewal of fertility in exhausted land.

These essays display the exuberant, practical agrarianism that underpinned the democratic politics of Thomas Jefferson. They substantiate the often abstract or intellectual agrarianism of the authors of I’ll Take My Stand. The Summer brothers, I believe, inherited fully and authentically agrarianism’s ancient tradition. That tradition, which has outcropped discontinuously in the literary record, was enabled to do so by its persistence from earliest times until now in the work and the conversation of the best farmers.

“Agrarianism” names the culture of farmed landscapes apparently all over the world. This is culture in the profoundest sense, neither “folklore” nor the urban romanticizing of rural life, but rather the complex knowledge and artistry of local adaptation. Or, to speak more truly, it is the culture of the effort of local adaptation, which has never been perfect and will never be finished. This culture, however confirmed it was by their wide reading, came fundamentally to the Summerses as a birthright. They could not have acquired it from the protoindustrial, and stereotypical, great plantations of the “Old South.” What they got of it that was most intimately their own, and they got plenty, they heard from their forebears and their neighbors.

Lanes Landing Farm, Port Royal, Kentucky

x plundered by bad farming in the Summers’ time, and are being plundered by bad farming still. If nature is to survive in our present world, it must survive in farming, just as in wilderness areas. The only health farming can have is natural health, and the only health we food-eaters can have must come from the health of farms.

Preface

This work had its beginnings in 1972 when I visited Marie Summer Huggins at Pomaria Plantation. Mrs. Huggins, granddaughter of Adam and William Summer’s brother Henry, was still teaching Latin in Newberry County. She was in her eighties and a faithful caretaker of the plantation. Pomaria was the home of Adam and William Summer in their youth, although I did not know it then. After her customary glass of old Madeira at the front door, Mrs. Huggins recollected my grandfather from the 1920s and 1930s as quite an impressive speaker of the “old school.” He had died before I was born, and this remembrance was very welcome. She then took me on a tour of the old house. She prided herself on keeping the original paint and faux graining from the 1820s. I recall her pointing out the large zigzag crack in the plaster of the north drawing room made by the Charleston earthquake of 1886. She refused to repair it out of homage to her forebears and for those who would come after her.

In the south drawing room she took me to William Summer’s drop-front plantation desk. It was open with a Pomaria Nursery ledger recording plant orders from the 1850s. Beside the ledger were William’s stylus pen, glasses, and brass candlestick, almost as if he had just left them when he stepped from the room. The chair at the desk had gone with William and Adam’s younger brother, Thomas Jefferson Summer, when he traveled to Giessen, Germany, in the 1840s to study plant and agricultural chemistry with Professor Justus von Liebig, the founder of the discipline and an early plant nutritionist. Over the desk hung George Cooke’s 1839 engraving of Charleston Harbor viewed from the Cooper River. On another wall was a tinted engraving of Raphael’s Madonna and Child with a sabre slash left by Judson Kilpatrick’s soldiers in February 1865. She pointed out a section of charred floorboards in this room, set on fire by those men and put out by the servants. During my visit, there was a cheerful fire in the large fireplace. It was Christmas, and the house was fragrant with cedar boughs brought from the near woods.

Mrs. Huggins said that from this south-facing parlor window William could look up from his desk in summer and see several acres of roses spreading down into the nursery’s rows. I later learned that the nursery in the 1850s sold over five hundred varieties of repeat-blooming roses chosen especially for the southern

climate by William and Adam and their Scots gardener, James Crammond. These would bloom into the fall. By 1861 the number of his roses offered for sale increased to six hundred varieties. During some rare years, I later found, Pomaria had roses blooming at Christmas time. As a lover of plants and a gardener myself, all this impressed me mightily. Who was this William Summer? What was he like? What led him to devote his life to gardening? Was growing plants, after all, worth a grown man’s time? He must have felt so. Why?

Equally impressive to me, as a lover of books, was Mrs. Huggins’s careful preservation of a very large collection bought by family members in antebellum times. Numbering in the many thousands, they lined from floor to ceiling both walls of the upstairs central hall that ran the length of the house. She noted that with the front double doors open to the upstairs portico, it was a breezy place where the books could breathe. It was an excellent place to sit and read. I recall her pointing out, “On this right wall are Mr. Henry’s books, and on the left are Mr. William’s.” I noticed in passing five or six volumes by Herman Melville, with their gilt titles shining on the spines of their bindings. There were Omoo, White Jacket, Redburn, Typee, and others. They were in mint condition and obviously had been lovingly cared for. I had just been teaching Typee in an American novel class, and that is probably why I remembered the Melville editions out of all the thousands. I also recalled that there were no new books from after 1865.

Nearly half a century later, I would learn that in the 1840s and 1850s, Henry and Adam Summer made annual visits to Charleston, Boston, and New York to purchase books. They were both bibliophiles of a high order. Even more pertinent, I found that Adam Summer was a part of the Young America Literary Movement in the 1840s and had met Evert Duyckinck, one of its founders and Melville’s best defender and promoter. The Melville volumes have since disappeared, their whereabouts unknown. If I had only opened them! Were they presentation copies? Manners, however, prevailed, and I did not ask to take them from the shelves.

Adam reviewed Melville’s books and other Young America writers such as Hawthorne, Poe, N. P. Willis, and W. G. Simms. He called Duyckinck his friend, met N. P. Willis, and was Simms’s friend, fellow editor, and fellow member of the South Carolina State Agricultural Society. Simms’s presentation copies of his Poems (1853) and Areytos (1860), signed to Henry and his sister, Catherine Parr Summer, were on these shelves and are extant today. The collection I saw on those walls in 1972 was the largest intact personal antebellum library I have seen then or since. I had never found so many books outside a college library. Mrs. Huggins deeply regretted the absence from the collection of the Elephant Folio of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, missing since the 1920s. This

Preface had been purchased by Adam, then transferred to Henry in antebellum times. Also missing were Audubon and John Bachman’s Viviparous Quadrupeds. I later learned that Bachman was a close family friend and often stayed at the plantation. He had browsed through some of these same books. Among them were volumes treating the dispute between the racial monogenists and polygenists (in which Bachman played a part as a monogenist) and a heavily annotated copy of Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of Creation, the book outlining evolution a decade before Charles Darwin.

Miss Marie made no mention of Adam’s volumes. Twenty years later, I found out why. They had gone to his own new plantation, Enterprise, at Summerfield near Ocala in Marion County, Florida in the late 1850s. The remnants of this collection came up for sale at Charlton Hall Galleries in Columbia, South Carolina, in February 1993. By that time I had been researching Adam, William, and the Pomaria Nursery in earnest for over a decade. A Columbia book dealer had salvaged the volumes that were in the best condition from the desolate scene of a library full of Adam’s books in a descendant’s old house in Savannah, Georgia. In 2013 I found out that, regrettably, in this salvaging process books considered unsalable at auction owing to their poor condition were left in the house to be hauled away.

Before the auction I spent a day cataloging the books and their inscriptions. At the sale itself on 13 February 1993, I was accompanied by Mrs. Huggins’s son, John Huggins, who then lived at Pomaria Plantation. His mother had died in 1974, two years after I had visited that Christmas. I bought as many of the significant titles (as I judged at the time) as I could afford. My friend Allen Stokes of the South Caroliniana Library was there as well and purchased Adam’s own copy of a bound volume of the South Carolinian, which he edited in the 1840s. We did not bid against one another, being only concerned that the books would not pass to those who did not appreciate the significance of their provenance. Luckily, I acquired Adam’s own copy of his and his brother William’s periodical, the Southern Agriculturist (1853–54), in which Adam identified some of his and William’s unsigned contributions and made a few corrections to some of his own. The book has contributed much to this edition.

By 1993 the two walls of books at Pomaria Plantation had been dispersed outside the house. Some had been sold, and others were in outbuildings. A large secretary in the house contained fewer than two hundred. In all locations I estimate there were less than half the number of the books I had seen in 1972. John Huggins allowed me to catalog these remaining books, many of them in the outbuildings, which included a large barn. Many were in a corn crib; others were upstairs in the barn’s hay loft and now sadly deteriorated. He told me to salvage

xiii

Preface

what I could, and over a period of several visits in vacations from teaching in a neighboring state, I did. I left nothing, not even rat-eaten shells.

Over the years, I have acquired other volumes bearing the Summer brothers’ signatures from various dealers and book stores. The volumes have informed this present book by providing a record of their owners’ interests. They have helped establish the valuable intellectual context—scientific, agrarian, and botanical— in which the essays were written. The extant literary works also provided an indication of their taste and literary influence.

It was Agrarian poet Allen Tate who wrote in his essay on Ezra Pound that “the task of the civilised intelligence is one of perpetual salvage.” This salvage is often a life’s work and the life’s work of many converging on a single task. Marie Huggins’s life’s work was one of these, and I thank her for her faithful stewardship and her hospitality in 1972, which inspired me to inquire further and seek to puzzle out the answers to questions that my visit raised. The memory of an intact, albeit battered, civilization was perhaps the greatest abiding encouragement in my scholar’s progress. Fine, ruined things from the past, as for the Romantic poets pondering transience and mutability, continued to be an irresistible draw for me. In the process of my research, I was to learn that I shared Adam Summer’s love for these poets and their understanding of the world.

More indispensable help came from Rosalyn Summer Sease of Wilmington, Delaware. She was Marie Huggins’s sister and thus also Adam and William’s grandniece. We corresponded from 1978 to 1979, and she provided me much information on her great uncles. She wrote that Adam, based on the stories the family told her, had always been her favorite ancestor. She had preserved valuable family material without which this edition would have been nearly impossible. At my suggestion, she donated a large portion of this personal family archive to the South Caroliniana Library. My thanks are due to E. L. Inabinett and Allen Stokes, former directors there, and to Henry Fulmer, current director, and to his staff, Michael Berry, Brian Cuthrell, Graham Duncan, Craig Keeney, and Lorrey Stewart for facilitating my use of these and the library’s general collections over a period of more than three decades. Mrs. Sease’s son, John, also helped me with information and documents in the 1980s and 1990s. These included a Pomaria Nursery ledger account book from 1879 to 1882, kept by William Summer’s nephew, John Adam Summer, when he inherited the nursery from his uncle in 1878.

As a result of Mrs. Sease’s donations, the South Caroliniana Library has the largest collection of Pomaria materials in existence. In 2003 Mrs. Sease’s granddaughter Catherine Sease edited an augmented version of much of the material

her grandmother provided me two decades before into a privately printed volume entitled Family Facts and Fantasies. This work has been of great value.

In 1979 Inabinett informed me that in the materials Mrs. Sease donated to the library, there was a manuscript novel written by O. B. Mayer. Mayer was William and Adam’s first cousin and close friend. It was at this time that I began to research in earnest the lives of all three in preparation to edit and publish the novel. Mayer’s work was set in 1846 at an “apricot repast” held around the well at Pomaria Plantation. The occasion of the gathering was to celebrate the harvest of Moorpark apricots, unusually fine that year, and to spin yarns. The group included both William and Adam Summer. William appeared in the novel as Billy. Adam appeared as the character Vesper Brackett, a pseudonym under which Adam wrote several of the pieces collected in the present volume. Mayer had Adam the “master of hospitalities” at the plantation at the time. The group of yarn spinners constituted an impromptu Dutch Fork school of writers and storytellers. My research culminated in the publication of Mayer’s John Punterick by Dr. James B. Meriwether’s Southern Studies Program at the University of South Carolina in 1981. This was followed in 1982 by my edition of Mayer’s history, The Dutch Fork, my own cultural history of the area of Adam and William’s birth, A Carolina Dutch Fork Calendar (1988), and my mother’s culinary history, Dutch Fork Cookery (1989).

Scholarship on Adam and William Summer and Pomaria Nursery is thus relatively recent. The first publication on the nursery was my article “On Reclaiming a Southern Antebellum Garden Heritage: An Introduction to Pomaria Nurseries” in the fall 1993 issue of Magnolia: Journal of the Southern Garden History Society. This appeared nearly a decade after William Howard’s groundbreaking 1984 master’s thesis at the University of South Carolina, “William Summer: 19th Century Horticulturist.” The Magnolia essay generated interest because no garden history of America had ever mentioned Pomaria or the nature writings of the Summer brothers, despite Pomaria’s larger, earlier influence than that of Fruitlands Nursery, an establishment well known to garden historians. Linda Askey Weathers’s article “Digging into Gardens Past” in Southern Accents (September 1992) reported on current Pomaria research. This was followed by an article on William and Adam’s natural history legacy, “Come, Friends of Beauty,” in South Carolina Wildlife in November 2002.

The first biographical profile, my article “William Summer: A Man for All Seasons,” appeared in the South Carolina Historical Society’s Carologue in Spring 2002. In February 2005, for the annual Johnstone Lecture at the Georgia Botanical Garden, I gave a talk titled “Pomaria: First Major Nursery in the Lower

Preface

This scholarship yielded results when James R. Cothran Jr.’s landmark Gardens and Historic Plants of the Antebellum South (2003) featured Pomaria as “the first major nursery in the lower and middle South.” Cothran, the premier garden historian of the antebellum period, attended the various lectures on Pomaria and championed the Summer brothers’ rediscovery until his death in 2012. He was using the evidence of Pomaria to choose plants in the restoration and design of historic Southern gardens. The University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum’s exhibit “Taking Root: The Summer Brothers and the History of Pomaria Nursery” was the first exhibit on Pomaria in South Carolina. It was held from June to September 2014. My gallery talk was on the subject of the brothers’ nature writing and thus was prelude to this book. Special thanks go to the museum director, Dr. Jane Przybysz, who made the exhibit possible, and for her continued support of the legacy of Pomaria. Also helping at this time was Mrs. Kajal Ghoshroy of the University of South Carolina, Sumter, Dr. John B. Nelson of the A. C. Moore Herbarium of the University of South Carolina, Mrs. Elizabeth Sudduth of the Thomas Cooper Library, the staff of the South Caroliniana Library, and Thomas McNally, dean of the libraries at the university.

As part of their “People You Should Know” winter lecture series at the South Carolina Historical Society in January 2015, I spoke on the Summer brothers’ nature writing. Helping me there were Dr. Faye Jensen, Karen Stokes, and Virginia Ellison.

Providing assistance at various times were Alex Moore of the University of South Carolina Press; William Cawthon; Beth and Tom Evers of Pomaria Plantation; Ann Hutchinson Waigand of Herndon, Virginia; Mrs. Suzanne Johnson; Mrs. Peggy Cornett, curator of historic plants, Monticello; Randy Ivey; Professor

xvi and Middle South.” The lecture highlighted excerpts from the Summers’s writings on horticulture. To accompany this lecture, the Georgia Botanical Garden mounted the first exhibit on Pomaria, on display from January to March 2005. Garden director Jefferson Lewis III and his staff were instrumental in these accomplishments. I presented the lecture “Pomaria and Upcountry Gardens” at the Southern Garden Heritage Conference in Athens, Georgia, on 17 February 2006, followed in March 2009 by the first lecture in South Carolina on Pomaria, “A Rich and Splendid Assortment: Pomaria’s Antebellum Patrons,” at Historic Columbia Foundation’s Annual Garden Symposium; this was followed by “Upcountry Garden Sophistication: The Evidence of Pomaria Nurseries” at the Southern Garden History Symposium in Camden, South Carolina, on 4 April 2009. Helping here were John Sherrer of the Historic Columbia Foundation and Davyd Foard Hood of the Southern Garden History Society.

David S. Shields; Scott White; Roy Rooks of Ballylee Nature Conservancy; and Nathan (“Nat”) Bradford. The Pomaria Society, formed in August 2014 as a result of the McKissick Museum’s Pomaria Exhibit, has the express mission of “the continuation of the work of Adam and William Summer.” It is they who will carry on the conservation ethic of sustainability and localism articulated in many of the essays in this collection. For moral support, I must also thank Wendell Berry, who has encouraged me in this and my various projects.

A Note on the Text

In his epigraph to “Fences” (Farmer and Planter 11, n.s. 2 [April 1860]: 102), Adam Summer defined “fence,” citing “Walker.” By “Walker” he meant John Walker’s A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary, and Expositor of the English Language, first published in London in 1791. Adam Summer’s fellow editor William Gilmore Simms (1806–1870) refused to use Noah Webster’s dictionary, which enforced a new American spelling that was actually a regional one centered in the North. He felt this to be a form of northern cultural imperialism symptomatic of the times. (See “Notes on the Text, or, the Devil and Noah Webster,” in Simms, William Gilmore Simms’s Selected Reviews on Literature and Civilization, ed. Kibler and Moltke-Hansen, xiii–xiv.) My favorite quotation on a Webster spelling, however, came from Charlestonian James Warley Miles. In 1880 at the newly structured University of South Carolina, student Eugene Dabbs recorded Miles as saying that today “[honour] is cut short enough without abbreviating the spelling, he spells it Honour” (Matalene 69).

Adam’s essays usually followed Walker’s spellings, but their texts as printed by various typesetters are not always consistent. Perhaps Adam was not consistent himself. Spelling in his day was more fluid. This edition follows the texts as printed with no attempt to regularize or modernize spellings. Adam’s texts most frequently (but not always) use dont and cant without apostrophes, in English fashion, centre, fibre, lustre, and sombre; and mould, vapour, colour, honour, and endeavour, but seldom humour. He used pencilled, gravelled, revelled, revelling, vallies, villified, excells, and other double-el Walker spellings. Other of Adam’s usual spellings include eyry (for aerie), chrystal, exstacy, extatic, burthen, gass (for gas), camelia, perriwinkle, exhuberant, wholsome, vieing and out-vieing, economise, systematise, checquered, deposites, indited, gallopped, visiters, ricketty, develope, barreness, and lower case negro and negroes. Two of his favorite words, which are often good indicators of his authorship, are amongst and whilst. William’s essays never use these two words. Another of Adam’s favorite words was tasty to mean tasteful. Adam always used Mock bird for mockingbird. William did not. William used milch cows for milk cows, a spelling that Adam seldom used. William also used the spellings potatoe, misletoe, and crysanthemum.

All these usages have been followed in this edition, so that the texts appear as they were published in the nineteenth century. Inconsistencies have been honored. A few insertions of paragraph breaks in pages-long essays by Adam Summer where no paragraphing existed out of journalistic practice have been the only emendations of the text. Only a very few of these have been found necessary.

Introduction

William Summer was born in 1815 in Newberry District in central South Carolina. His brother Adam Geiselhardt Summer was born three years later in 1818. They were descended from the German and Swiss-German Sommer, Hausihl (Houseal), Meyer (Mayer), Süss (Sease), and Geiselhardt families who settled the Dutch (Deutsch) Fork area between the Broad and Saluda Rivers in the 1750s.

The Summer brothers were well aware of their families’ Revolutionary War past in upcountry South Carolina. Their grandfather Nicholas Summer, a major in the Continental Army, born in 1754, was killed in 1781 in a sortie at Fort Granby on the Congaree at the age of twenty-seven. His son, their father, Captain John Adam Summer III (b. 1779), was only two years old when Nicholas died. John grew up without a father, and of course William and Adam knew Nicholas only from family stories, of which there were many.

Their great grandfather, Captain Johannes (“Hans”) Adam Sommer I (1716–1784), the old pioneer, also served in the patriot cause as both soldier and supplier of meal, grits, and flour from his mill. All his six sons fought for American independence. The Sommer mill was the local gathering spot for the patriots, who reconnoitered there before and after skirmishes and battles. Here the German and Swiss-German settlers brought provisions from their farms, and Sommer had them transported to the soldiers, once across the Enoree and Tyger Rivers to supply General Thomas Sumter before the Battle of Blackstocks in neighboring Union County on 1 November 1780. Blackstocks was to be a turning point in the war, the first patriot victory over Banastre Tarleton, which led directly to the British defeat at Cowpens. The British captured the Sommer mill but could not hold it. It was fortified and garrisoned by the Fairfield Militia under Colonel Richard Winn of Winnsboro. On the distaff side William and Adam’s grandfather, Captain Wilhelm Frederick Hausihl (b. 1730), was a local legend as a fearless and effective patriot.

William and Adam, who had five other brothers and a sister, grew up on the Summer family plantation. Their father was like his fellow German immigrant neighbors in having an independent, self-sufficient farm, the kind that founding father Thomas Jefferson had advocated. It was only in Adam and William’s time

that the cotton boom began to change the face of agriculture in the Dutch Fork and the slave system became the norm, with the great wealth that could be made from the staple and the system. For the Summer family this cotton-growing era was the time of moving from pewter to silver and the building of a fine Palladian plantation house constructed when William had just entered his teens and Adam was about to do so.

There had been slaves in the Dutch Fork from the beginning but not in the large numbers of the lowcountry. The early Sommer and Hausihl families were among the early slave owners. Most of the settlers came on land grants to Protestants made possible by Lutheran King George II. Some were indentured servants themselves, but most paid their passage. Many could sign their names. For the most part they were fleeing the terrible wars between Protestants and Catholics in the old country and were in search of land to farm, with the independence and better opportunities that came with land ownership. Hans Adam Sommer had to work off his indenture; the well-to-do Hausihls did not.

The Hausihls were also farmers. They were well educated and had served in Germany as educators and ministers. The pioneer Hausihl’s father, Bernard Hausihl, D.D., was a pastor of the German Reformed Church and a professor of the Protestant Theological Seminary in Heilbronn, Württemberg, Germany. Later he moved with his family to London, where he was with the Lutheran chapel and was court preacher to Hanoverian King George II. Both Bernard Hausihl’s sons came to America. One went to the North and was a Tory. The other went to the South and was a patriot. William and Adam’s grandfather was the son who went south. Captain William Frederick Hausihl raised a patriot troop of horsemen at his own expense and became a well-known raider assisting Generals Francis Marion and Thomas Sumter. He was an excellent horseman, and his troop of cavalry served in the regiment of Philemon Waters.

Perhaps taking from their mother’s Hausihl side, John Adam Summer’s children were all lovers of books. Several of them, including Adam, were avid bibliophiles with large and eclectic libraries. As the remnants of their libraries show, Adam and William’s brother Henry Summer’s main interests were theology, history, philosophy, literature, and natural science. Adam collected literature and writing on natural science, history, travel, exploration, and agriculture. William’s interests ran to literature, natural science, botany, history, and philosophy. They all three collected books on agriculture and nature. Henry would go on to help found Newberry College. He was the first secretary of the trustees there in 1859. The president of the trustees was his close friend the Reverend John Bachman of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston. Bachman, a naturalist and John James Audubon’s patron and collaborator beginning in 1831, served as mentor to both

William and Adam. Adam donated some of his library to the fledgling institution in 1860.

Five of the six brothers attended college. Nicholas, John Adam IV, Henry, and Adam all went to South Carolina College. Thomas Jefferson Summer (b. 1826) went to West Point for one year before rejecting the military for what he called the noblest of professions—farming. He traveled to Heidelberg, where he studied German, and enrolled at Giessen University to study the new science of agricultural chemistry under the founder of the discipline, Professor Baron Justus von Liebig. Thomas was planning to devote his life to the restoration and rejuvenation of depleted soils in his native upcountry. His sad death in 1852 from the hemorrhage of ulcers ended a promising career at the age of twenty-five. The loss was nothing short of tragic for both Adam and William, who were particularly devoted to their younger brother. As his extant letters reveal, William suffered a long fit of depression. Their father, also still grieving, died three years later in 1855. In 1852 Adam took over Thomas’s life work. His essays on land restoration and proper treatment of the soil, a sampling of which are published here, no doubt were influenced by his brother’s commitment to the cause. One can sense the presence of Thomas in Adam’s “Address” (pp. 53–70, this volume), given six months after his brother’s death.

All the Summer lads learned early to study and respect nature. As Adam revealed in his “Winter Green, a Tale of My School Master” (pp. 38–43), they studied at the parochial school attached to the local St. Johannes Kirche (St. John’s Lutheran Church). Their gentle teacher took them on nature walks in the virgin oak-hickory forest surrounding the church. This forest was the church glebe granted to the congregation in 1754. It was there in the old woodland that Adam said he learned to love the natural world. His essays on “noble trees” collected in this volume stemmed from what he called his “near worship” of the trees around St. John’s, especially when the church became angrily divided over doctrinal issues. Although he had an affinity for all native trees, large and small, he particularly loved the oak family, or what he called the “oak tribe.” His three essays “The Forest Trees of the South” (pp. 87–95) are but a few of the many devoted to the subject. His notable comment “Of all the things in the landscape, I would deal most gently with trees” is a good indication of his abiding love for this majestic feature of nature.

While William and Adam were children, English replaced German in the pulpit of their church. The older members of the congregation resisted, but it was the young, perhaps William and Adam among them, who favored English and brought about the change. Adam would always emphasize English over German culture. Still, the oldest folks, according to the brothers’ cousin O. B. Mayer,

xxiii

luxuriated in the language when they got together. In so many ways, the brothers’ childhood was a time of great transition. Their father still had a thick German accent. A family friend, Edwin Scott, noted in his reminiscences of Columbia that John Adam Summer said that his son Adam “had spent a year or so in the Creek” (that is, studying Greek), thus demonstrating the father’s heavy German brogue (15). One of the local Pomaria companies in the war in 1861 was called “the Dutch” owing to their German accents.

In the log schoolhouse at St. John’s, the two brothers were also taught the classics and a love for literature that remained with them throughout their lives. Shakespeare’s plays (an abiding love with Adam) were performed on the school porch with quilts borrowed from the neighborhood to serve as backdrops in their productions. Adam singled out the particular influence of Virgil’s Georgics (which he loved better than his Æneid ), Horace (the Odes and Ars Poetica), Sallust, Plutarch, and Juvenal. Juvenal’s satires would perhaps influence Adam’s own satirical bent, seen in many essays collected in this volume. Juvenal and Virgil would remain Adam’s primary early literary influences throughout his writing career. Adam would have liked particularly Juvenal’s answer to someone who asked why he didn’t go to Rome—because, as he declared, he didn’t relish treachery, trickery, and lying. As his essays reveal, Adam’s dislike for urbanization kept pace with the growth of cities, particularly in the North.

After St. John’s, Adam went with his cousin O. B. Mayer to the village of Lexington, where they studied at the Lexington Classical Academy for several years. There the lads again had a close regimen in Latin and Greek in a school that was sponsored by Lutherans as preparatory to the Lutheran Seminary, which had moved there from the Pomaria vicinity around 1831. The Lexington institution was open to males over ten, which meant that Adam would not have matriculated until 1832 or later. There he had good teachers, one of whom was Ernest Lewis Hazelius (1777–1853). Hazelius, born a Moravian in Silesia, Prussia, was persuaded to come to Lexington from Gettysburg Lutheran Seminary by the Reverend John Bachman. Both Hazelius and Bachman emphasized the common beliefs of Lutherans with other Christian denominations, a tradition of tolerance that influenced both Adam and Henry in their spiritual lives. At the time Lexington village was described as one continuous pine forest containing the courthouse, a boarding house, a few dwellings, and “three regular grogshops and two licensed taverns—all well attended” (McArver and Hendrix 6). Hazelius was especially diligent in building a good seminary library, which he “patiently catalogued” (McArver and Hendrix 5).

The oldest brother, Nicholas, born in 1804, graduated with first honors at South Carolina College in 1828. He then practiced law before being killed in

the Seminole War near Tampa, Florida, at the age of thirty-two in 1836. The second son, Henry, born in 1809, graduated from South Carolina College in 1831 and became a lawyer in Newberry. John Adam IV, born in 1812, graduated from South Carolina College in 1834. He followed Nicholas to Florida and died of fever a few days after Nicholas at the age of twenty-four. The deaths of their brothers shadowed the early lives of both Adam and William, who were eighteen and twenty-one years old at the time. Catherine Parr Summer, their only sister (1823–1906), went to a female academy in Greenville, South Carolina. She was also a lover of books, as the extant presentation copies to her from Adam and Henry attest. Adam’s gift of Emma Embury’s American Wild Flowers in Their Native Haunts (New York: Appleton, 1845) has twenty hand-colored engravings and demonstrates their shared love of what was to become Adam’s special horticultural interest in native plants. It was William and Catherine who were to be the keepers of the flower and vegetable gardens at the plantation in the 1840s and 1850s. Adam, William, and Catherine also shared a love for poetry.

William contracted polio as a child and had to walk with crutches all his life. He said that this prevented him from attending college like his brothers. He detailed the pain he suffered in “The Character of a Pomologist” (pp. 70–72), recording how, despite his affliction, he still wanted to be useful and thus learned the art of grafting and growing trees. He found he was good at it. He was mentored by a few elderly men of the neighborhood, who had been born in Germany, and then later by Bachman and Joel R. Poinsett. Though not a college student, he was extremely well-read in such subjects as history and literature. He was thus largely self-educated but had the benefit of closeness to both Henry and Adam. Extant in his library are presentation copies signed to him by his brothers.

Adam was at South Carolina College when Thomas Cooper was leaving the presidency. Cooper’s influence on him, as for other students, was great. There Adam also studied modern literature and the classics. The students at the college received a broad classical education designed to produce a gentleman who could excel in all walks of life. The object of education was to help a man do many things well so that he would be proficient in his planted fields, his library, and his drawing room. Entering freshmen at the college were required to have a good knowledge of Latin and Greek grammar, to have already read the whole of Virgil’s Æneid, Cicero’s Orations, Caesar’s Commentaries, Sallust, Xenophanes’s Cyropædia, the Gospel According to St. John in Greek, and at least one book of Homer. Sophomore studies included Horace and Homer’s Iliad. Adam may have learned chemistry from William H. Ellet, newly come from Columbia College in New York. Isaac Stuart likely taught him Greek and Roman Literature. Other possible teachers were Henry Junius Nott (belles lettres, language, and logic),

Introduction

Thomas Twiss (mathematics and natural philosophy), Francis Lieber (history and political economy), Robert Henry (political economy), and William Capers and Stephen Elliott Jr. (sacred literature).

Classmate William McIver in January 1836 described the college routine: “Monday and Tuesday recitations before breakfast. Every Wednesday and Thursday, we recite in Cicero and the other days of the week in Homer. These are heard at 4 p.m. by Mister Stuart. . . . Every Friday is devoted to hearing lectures on History from Dr. Lieber” (Matalene 6).

Nott’s Novellettes of a Traveller; or, Odds and Ends from the Knapsack of Thomas Singularity was published by Harper in 1834 and may have been an influence on Adam. Nott (1797–1837) graduated from South Carolina College in the class with Hugh Swinton Legaré. He abandoned law for literature. He was a world traveler and studied in France and England from 1821 to 1824. He had written on travel literature in articles in the Southern Review. Adam would also learn to love travel. Nott purchased books for the college library on two trips to Europe. Growing up, Adam was thus surrounded by people who loved and valued books. Nott’s novel was very popular with the students. Adam was probably one of them. William Gilmore Simms praised its humor in pieces in the Southern Review (Letters 1: 198). He tried to get Nott’s unfinished novel published in Magnolia in the 1840s. Above all, the college was a center of study of the natural sciences and had been from its early days. Naturalists had been dominant there since the founding by John Drayton in 1801. Drayton was no mean botanist and naturalist himself, as his edition of Thomas Walter’s Flora Caroliniana proves. Nicholas Herbemont’s four-acre garden a few blocks from the campus at Bull and Lady Streets was a showplace of horticultural excellence. Herbemont (1771–1839) was an early mentor of both William and Adam. A college trustee and honorary member of the Euphradian Society, he sometimes taught French (his native language) at the college. As William recorded, Herbemont sent grapes to William at Pomaria Nursery before William had named and officially opened it. Mr. and Mrs. Herbemont shared their love of grapes and roses with the brothers. Herbemont also called for soil rejuvenation and conservation in the 1820s (Shields, Southern Provisions 6). The college tradition of pursuing the study of nature thus reinforced Adam’s early years in the forest at St. John’s and prepared him to inquire into things, with one of the significant results being the nature writing he composed throughout his life.

As Adam entered his twenties, Virgil, Juvenal, Horace, and Homer were still his literary companions, but he had added Chaucer, Swift, Pope, Dryden, Milton, and Ben Jonson, and was developing a love for Romantic literature, especially poetry. When he left South Carolina College, the school was undergoing

Introduction

great turmoil, caught in the political battle between Nullifiers and Unionists being waged two blocks away at the South Carolina State House. There was also feuding between the Presbyterians and Free-Thinkers like President Cooper, Nott, and other faculty, a liberal tradition that had begun with its first president, Jonathan Maxcy, whom Adam revered (see “A Day on the Mohawk,” pp. 19–23). After two years at college, Summer had enough of the classics and felt he could better spend his time in the great classroom of the world (Sease 152). In true Romantic fashion his desire was to see nature untouched by the hand of man. Nott drowned in 1837 trying to rescue his wife from a shipwreck, and this may have been another reason for Adam’s departure.

As several of the essays collected here relate, Adam went to what he called the “Far West” after leaving college. In his teens, he was on the Red and Canada Rivers in Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Just how far west he went is unknown. He also mentioned Minnesota and going into Canada. He noted seeing the Comanches and other native tribes in their villages—especially the Comanches, a very risky business. This would have been in the Red and Canada River vicinities.

His exploring may have been facilitated by or have come as a direct result of his acquaintance with Joel Roberts Poinsett, another indefatigable traveler (in South America and Asia). Poinsett had left his duties as minister to Mexico and was now secretary of war, with the duty of surveying and setting up forts in the West. As he was with William, Poinsett was to be an early mentor of Adam. As a botanist, horticulturist, plant collector, explorer, planter, gardener, and devotee of the fine arts, Poinsett’s broad interests were inspirations to both brothers. Adam’s essays show a strong interest in fine art.

Adam’s going west may have also been connected to the death of James Butler Bonham at the Alamo in March 1836. Bonham (1807–1836) had been expelled from South Carolina College in 1827 and had known Adam’s brothers Nicholas and Henry there. Bonham and the stirring times of the Texas Revolution may have made college seem dull to Adam. American military dealings with the Comanches, pursued in hopes of an alliance against Mexico, may have explained Adam’s access to the tribes.

Although Adam never gave many details about the frontier violence he witnessed and perhaps was involved in, his western experience was traumatic. So disillusioned was he that he vowed he could turn his back on the shams of all humans and leave the “man-world” forever. His attitude to the westering “progress” of settlement was not the popularly accepted one of the day. He questioned the wisdom of “Manifest Destiny” for a number of reasons, as his essays reveal. He did not share the boosterism of American nationalism. For him, emphatically, bigger was not better. In Adam’s theory of localism and his crusade against

bigger is better, the words “empire” and “ruin” were to become synonymous. He felt that Americans moving westward actually prevented the stability required for “planting arts and learning” and was not only a detriment to the progress of civilization but also a means of despoiling nature. Adam’s nature writing would question the bases of American plans for the settlement and taming of the continent by the impress of the template of eastern establishment ideas upon western lands. His essays would often be shaped not by buoyant optimism but by a deep-seated melancholy. In this he was not unlike the Romantic writers he admired. By the 1840s he had entered the poetic worlds of Keats, Shelley, Byron, Goldsmith, Thomas Gray, Coleridge, Charles Lamb, and the lesser Romantics in both England and America.

William, meanwhile, stayed at home. While Henry was practicing law, his older brothers Nicholas and John Adam were buried in Florida, and Adam, younger by three years, was about to take off for the “Far West.” Left with his eleven-year-old sister, Catherine, and his eight-year old brother, Thomas Jefferson, William started propagating and selling grapes and apple trees. The earliest evidence of this work was 1834, when he was nineteen years old. Still living at home with his father and mother in 1840, he officially opened his Pomaria Nursery on the family lands surrounding the plantation house. He was twentyfive years old at the official founding. Today, in the words of James R. Cothran, premier landscape historian of the antebellum South, Pomaria was to become the first major nursery of the middle and lower South (142). On 12 February 1840, in the same year he founded the nursery, William jotted on the cover of an issue of Knickerbocker Magazine his first known essay, “A Winter Reverie,” the initial work in this collection (p. 1). It, like Adam’s pieces, shows William to be a man with the sensibilities of his Romantic era. The extemporaneous jotting was the histrionic work of a young man. He never published it, and it survives only in manuscript.

It was William who gave the nursery its name, Latin for orchards (plural of pomarium), and also with the suggestion of Pomona, Roman goddess of the orchard. William, like Adam, had also been reading his Georgics. The town of Pomaria that grew up around the new depot on the Greenville and Columbia Rail Road in the early 1850s took its name from the nursery. The village had originally been called Countsville, from the German family Counts (Kuntz) who had settled there. From the new Pomaria Depot in 1851, Pomaria Nursery shipped its plants around the South. Before 1861 Pomaria plants had gone as far as Mississippi and Louisiana and across the Atlantic to Van Houtte in Belgium. Pomaria Plantation and Nursery were on the old state road that ran from Charleston to Spartanburg and on to Buncombe County, North Carolina. Hence, it got much

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

the territory with a close network, which has been evidenced in a recent trial, and have been so bold as to defy the Church dignitaries not accepting their vassalage. In pointing to the peril of increasing mortmain threatening the principle of the free circulation of property, it is sufficient to say that we are influenced by no vain alarms, that the value of the real property occupied or owned by the communities was in 1880 as much as 700,000,000f., and that it now exceeds a milliard. Starting from this figure, what may be the value of mortmain personalty? Yet the real peril does not arise from the extension of mortmain. In this country, whose moral unity has for centuries constituted its strength and greatness, two youths are growing up ignorant of each other until the day when they meet, so unlike as to risk not comprehending one another. Such a fact is explained only by the existence of a power which is no longer even occult and by the constitution in the State of a rival power. All efforts will be fruitless as long as a rational, effective legislation has not superseded a legislation at once illogical, arbitrary, and inoperative. If we attach so much importance to a Law on Association it is also because it involves the solution of at least a portion of the education question. This Bill is the indispensable guarantee of the most necessary prerogatives of modern society."

{237}

This pre-announcement of the intentions of the government gave rise, as it must have been intended to do, to a warm discussion of the project in advance, and showed something of the strength of the antagonists with whom its supporters must make their fight. At length, late in December a few days before the opening of debate on the bill in the Chambers the attitude of the Church upon it was fully declared by the Pope, in a lengthy interview which M. Henri des Houx, one of the members of the staff of the "Matin," was permitted to publish in that Paris journal. "After M. Waldeck-Rousseau's Toulouse

speech, and in presence of the Associations Bill," said the Pope, "I can no longer keep silent. It is my Apostolic duty to speak out. French Catholics will know that their father does not abandon them, that he suffers with them in their trials, and that he encourages their generous efforts for right and liberty. They are well aware that the Pope has unceasingly laboured in their behalf and for the Church, adapting the means to the utility of the ends. The pilot is the judge of the manœuvre at the bar. At one moment he seems to be tacking before the tempest; at another he is bound to sail full against it. But his one aim ever is to make the port. Now, the Pope cannot consent to allow the French Government to twist the Concordat from its real intent and transform an instrument of peace and justice into one of war and oppression. The Concordat [see, in volume 2, FRANCE:

A. D. 1801-1804]

established and regulated in France the exercise of Catholic worship and defined, between the Church and the French State, mutual rights and duties. The religious communities form an integral part of the Apostolic Church as much as the secular clergy. They exercise a special and a different mission, but one not less sacred than that of the pastors recognized by the State. To try to destroy them is to deal a blow at the Church, to mutilate it, and to restrain its benefits. Such was not the intent of the Concordat. It would be a misconstruction of this treaty to declare illegal and to interdict whatever it was not able to settle or foresee. The Concordat is silent as to religious communities. This means that the regular clergy has no share in the special rights and relative privileges granted by the Concordat to the members of the secular ecclesiastical hierarchy. It does not mean that religious orders are to be excluded from the common law and put outside the pale of the State. … There was no need of mentioning the religious communities in the Concordat because these pious bodies were permitted to live under the shelter of the equal rights accorded to men and citizens by the fundamental clauses of your Constitution. But if an exception is to be made to these solemn declarations in the case of certain citizens it is an

iniquity towards the Church, an infraction of the intentions of the negotiators of 1801. Look at the countries with which the Holy See has signed no Concordat, and even at Protestant countries like England, the United States, and many another. Are religious communities there excluded from the liberties recognized as belonging to other citizens? Do they not live there without being harassed? And thither, perhaps, these communities would take refuge, as in the evil days of the Terror, from the iniquity of Catholic France! But since then France has become bound by the Concordat, and she seems to forget it. …

"Why does France figure to-day by the side of the great nations in the concert of the Powers settling the Chinese question? Whence have your Ministry for Foreign Affairs and your representative in Peking the authority which gives weight to their opinion in the assembly of plenipotentiaries? What interest have you in the north of China? Are you at the head there in trade and industry? Have you many traders there to protect? No. But you are there the noblest champions of Christian civilization, the protectors of the Catholic missions. Your foreign rivals are envious of this privileged situation. They are seeking to dispute your rights laid down in treaties that assign to you the rôle of defenders of native missions and Christian settlements. … Hitherto your Governments had had a better notion of the importance of their rights. It is in the name of treaties guaranteeing them that they protested to me when the Chinese Emperor asked me to arrange diplomatic relations directly with the Holy See. Upon the insistence of M. de Freycinet, the then Minister, I refused, so fearful was I that France might believe, even wrongfully, that I wished in any way to diminish her prestige, her influence, and her power. In the Levant, at Constantinople, in Syria, in the Lebanon, what will remain of the eminent position held by your Ambassador and Consuls if France intends to renounce representing there the rights of Christianity? …

"M. Waldeck-Rousseau, in his Toulouse speech, spoke of the moral unity of France. Who has laboured more than I for it? Have I not energetically counselled Catholics to cease all conflict against the institutions which your country has freely chosen and to which it remains attached? Have I not urged Catholics to serve the Republic instead of combating it? I have encountered warm resistance among them, but I believe that their present weakness arises from their very lack of union and their imperfect deference to my advice. The Republican Government at least knows in what degree my authority has been effective towards bringing about that public peace and moral unity which is proclaimed at the very moment when it is seriously menaced. It has more than once thanked me. If the Pontifical authority has not been able entirely to accomplish the union so much desired I at least have spared no effort for it. Is there now a desire to reconstitute the union of Catholics against the Republic? How could I prevent this if, instead of the Republic liberal, equitable, open to all, to which I have invited Catholics to rally, there was substituted a narrow, sectarian Republic, governed by an inflamed faction governed by laws of exception and spoliation, repugnant to all honest and upright consciences, and to the traditional generosity of France? Is it thought that such a Republic can obtain the respect of a single Catholic and the benediction of the Supreme Pontiff? I still hope that France will spare herself such crises, and that her Government will not renounce the services which I have been able to render and can still render it. {238}

On several occasions, for instance, and quite recently, I have been asked by the head of a powerful State to allow disregard of the rights of France in the East and Far East. Although compensations were offered to the Church and the Holy See, I resolved that the right of France should remain intact, because it is an unquestionable right, which France has not allowed to become obsolete. But if in your country the

religious orders, without which no Catholic expansion is possible, are ruined and suppressed, what shall I answer whenever such requests are renewed to me? Will the Pope be alone in defending privileges the possessors of which prize them so little?"

Of the seriousness of the conflict thus opening between the French Republicans and the Roman Catholic Church there could be no doubt.

The threatened bill was brought forward by the government and debate upon it opened on the 15th of January, 1901. The most stringent clauses of the measure were translated and communicated to the "London Times" by its Paris correspondent, as follows:

"II. Any association founded on a cause, or for an illicit end, contrary to the laws, to public order, to good manners, to the national unity, and to the form of the Government of the Republic, is null and void.

"III. Any member of an association which has not been formed for a determined time may withdraw at any term after payment of all dues belonging to the current year, in spite of any clauses to the contrary.

"IV. The founders of any association are bound to publish the covenants of the association. This declaration must be made at the prefecture of the Department or at the sub-prefecture of the district which is the seat of the association. This declaration must reveal the title and object of the association, the place of meeting and the names, professions, and domiciles of the members or of those who are in any way connected with its administration. … The founders, directors, or administrators of an association maintained or reconstituted illegally after the verdict of dissolution will be punished with a fine of from 500f. to 5,000f. and

imprisonment ranging from six days to a year. And the same penalty will apply to all persons who shall have favoured the assemblage of the members of the dissolved association by the offer of a meeting place. …

"X. Associations recognized as of public utility may exercise all the rights of civil life not forbidden in their statutes, but they cannot possess or acquire other real estate than that necessary for the object which they have in view. All personal property belonging to an association should be invested in bonds bearing the name of the owner. Such associations can receive gifts and bequests on the conditions defined by Clause 910 of the Civil Code. Real estate included in an act of donation or in testamentary dispositions, which is not necessary for the working of the association, is alienated within the period and after the forms prescribed by the decree authorizing acceptance of the gift, the amount thereby represented becoming a part of the association's funds. Such associations cannot accept a donation of real estate or personal property under the reserve of usufruct for the benefit of the donor.

"XI. Associations between Frenchmen and foreigners cannot be formed without previous authorization by a decree of the Conseil d'Etta. A special law authorizing their formation and determining the conditions of their working is necessary in the case, first of associations between Frenchmen, the seat or management of which is fixed or emanates from beyond the frontiers or is in the hands of foreigners; secondly, in the case of associations whose members live in common. …

"XIV. Associations existing at the moment of the promulgation of the present law and not having previously been authorized or recognized must, within six months, be able to show that they have done all in their power to conform to these regulations."

Discussion of the Bill in the Chamber of Deputies was carried

on at intervals during ten weeks, the government defeating nearly every amendment proposed by its opponents, and carrying the measure to its final passage on the 29th of March, by a vote of 303 to 220. Of the passage of the bill by the Senate there seems to be no doubt. After disposing of the Bill on Associations, on the 27th of March, the Chamber adjourned to May 14.

----------FRANCE: End--------

FRANCHISE LAW, The Boer.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL): A. D. 1899 (MAY-JUNE); and (JULY-SEPTEMBER).

FRANCHISES, Taxation of public,

See (in this volume)

NEW YORK STATE: A. D. 1899 (MAY).

FRANKLIN, The Canadian district of.

See (in this volume) CANADA: A. D. 1895.

FRANZ JOSEF LAND: Exploration of.

See (in this volume) POLAR EXPLORATION, 1896; 1897; 1898-1899; 1900-; and 1901.

FREE SILVER QUESTION, The.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1896 (JUNE-NOVEMBER);

and 1900 (MAY-NOVEMBER).

FREE SPEECH:

Restrictions on, in Germany.

See (in this volume)

GERMANY: A. D. 1898; and 1900 (OCTOBER 9).

FREE TRADE.

See (in this volume) TARIFF LEGISLATION.

FREE ZONE, The Mexican.

See (in this volume) MEXICAN FREE ZONE.

FRENCH SHORE QUESTION, The Newfoundland.

See (in this volume)

NEWFOUNDLAND: A. D. 1899-1901.

FRENCH WEST AFRICA.

See (in this volume)

AFRICA: A. D. 1895; and NIGERIA: A. D. 1882-1899.

FRIARS, Spanish, in the Philippines.

See (in this volume) PHILIPPINE ISLANDS: A. D. 1900 (NOVEMBER).

{239}

G.

GALABAT, Battle of.

See (in this volume)

EGYPT: A. D. 1885-1896.

GALVESTON: A. D. 1900.

The city overwhelmed by wind and waves.

"The southern coast of the United States was visited by a tropical hurricane on September 6-9, the fury of which reached its climax at and near Galveston, Texas, 1:45 A. M., on Sunday, the 9th. Galveston is built upon the east end of a beautiful but low-lying island some thirty miles long and six or seven miles wide at the point of greatest extent, though only a mile or two wide where the city is built. The pressure of the wind upon the waters of the Gulf was so powerful and so continuous that it lifted the waves on the north coast many feet above the ordinary high-tide level, and for a short time the entire city was submerged. … The combined attack of hurricane and tidal-wave produced indescribable horrors the destruction of property sinking into insignificance when compared with the appalling loss of life. The new census taken in June accredited Galveston with a population of 37,789. The calamity of a few hours seems to have reduced that number by 20 per cent. The loss of life in villages and at isolated points along the coast-line will probably bring the sum total of deaths caused by this fatal storm up to 10,000. The condition of the survivors for two or three days beggars description. The water had quickly receded, and all means of communication had been destroyed, including steamships, railroads, telephone and telegraph lines, and public highways. Practically all food supplies had been destroyed, and the drinking-water supply had been cut off by the breaking of the aqueduct pipes. The tropical climate required the most summary measures for the disposition of the bodies of the dead. Military

administration was made necessary, and many ghoulish looters and plunderers were summarily shot, either in the act of robbing the dead or upon evidence of guilt. …

"Relief agencies everywhere set to work promptly to forward food, clothing, and money to the impoverished survivors. Great corporations like the Southern Pacific Railroad made haste to restore their Galveston facilities, and ingenious engineers brought forward suggestions for protection of the city against future inundations. These suggestions embraced such improvements as additional break-waters, jetties, dikes, and the filling in of a portion of the bay, between Galveston and the mainland. The United States Government in recent years has spent $8,000,000 or $10,000,000 in engineering works to deepen the approach to Galveston harbor. The channel, which was formerly only 20 or 21 feet deep across the bar, is now 27 feet deep, and the action of wind and tide between the jetties cuts the passage a little deeper every year. The foreign trade of Galveston, particularly in cotton, has been growing by leaps and bounds."

American Review of Reviews, October, 1900, page 398.

GARCIA, General:

Commanding Cuban forces at Santiago.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1898 (JUNE-JULY).

GENEVA CONVENTION:

Adaptation to maritime warfare.

See (in this volume) PEACE CONFERENCE.

GEORGE, Henry:

Candidacy for Mayor of Greater New York, and death.

See (in this volume) NEW YORK CITY: A. D. 1897 (SEPTEMBER-NOVEMBER).

GERMAN ORIENT SOCIETY: Exploration of the ruins of Babylon.

See (in this volume) ARCHÆOLOGICAL RESEARCH: BABYLONIA: GERMAN EXPLORATION.

GERMAN PARTIES, in Austria.

See (in this volume) AUSTRIA-HUNGARY.

----------GERMANY: Start--------

GERMANY: A. D. 1891-1899. Recent commercial treaties. Preparations for forthcoming treaties.

"The new customs tariff of July 15, 1879 [see, in volume 4, TARIFF LEGISLATION (GERMANY): A. D. 1853-1892] exhibited the following characteristics: An increase of the existing duties and the introduction of new protective duties in the interests of industrial and agricultural products. The grain and wood duties, abolished in 1864, were reintroduced, and a new petroleum duty was adopted. Those on coffee, wine, rice, tea, tobacco, cattle, and textiles were raised. Those on iron were restored; and others were placed on many new articles formerly admitted free. In 1885 the tariff was again revised, especially in the direction of trebling the grain and of doubling the wood duties. Those on cattle, brandy, etc., were raised at the same time. The year 1887 saw another general

rise of duties. But, on the other hand, some reductions in the tariff for most-favored nations came about in 1883 and in 1889 in consequence of the tariff treaties made with Switzerland and Spain. Other reductions were made by the four tariff treaties of 1891 with Belgium, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland, and again in 1892 and 1893, when like treaties were respectively made with Servia and Roumania. Increases in some duties took place in 1894 and 1895, such as those on cotton seeds, perfumes, ether, and honey. … In consequence of the higher price, rendered possible at home from the protective duty, the German manufacturer can afford to sell abroad the surplus of his output at a lower price than he could otherwise do. His average profit on his whole output is made up of two parts: Firstly, of a rather high profit on the sales in Germany; and, secondly, of a rather low profit on the sales abroad. The net average profit is, however, only an ordinary one; but the larger total quantity sold (which he could not dispose of without the foreign market, combined with the extra low price of sale abroad) enables him to produce the commodity in the larger quantities at a lower cost of production than he otherwise could if he had only the German market to manufacture for. He thereby obtains abroad, when selling against an Englishman, an indirect advantage from his home protection, which stands him in good stead and is equivalent to a small indirect benefit (which the Englishman has not) on his foreign sales, which is, however, paid for by the German consumer through the higher sale price at home.

{240}

"The customs tariff now in force provides one general or 'autonomous' rate of duty for all countries, from which deviations only exist for such nations as have tariff treaties or treaties containing the most-favored-nation clause. Such deviations are 'treaty' or 'conventional' duties. At the present moment treaties of one kind or another exist with most European powers (excepting Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal)

and with the majority of extra-European countries. So that, with few exceptions, the German Empire may now be said to trade with the world on the basis of the lower 'conventional' or 'treaty' tariff. Most of the tariff treaties existing in Europe expired early in 1892, whereupon many countries prepared higher customs tariffs in order to be prepared to grant certain concessions reciprocally when negotiating for the new treaties. Germany, therefore, under the auspices of General Caprivi, set to work to make a series of special tariff treaties with Belgium, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland, which were all dated December 6, 1891. Later additions of the same class were those with Servia in 1892, with Roumania in 1893, and with Russia in 1894.

"Perhaps almost the greatest benefit conferred upon the country by these seven tariff treaties was the fact of their all being made for a long period of years and not terminable in any event before December 31, 1903. This secured for the mercantile classes the inestimable benefit of a fixed tariff for most of the important commodities of commerce over a long period of time a very valuable factor in trade, which has in this case greatly assisted the development of commerce. The reductions in Germany granted by these treaties were not great except on imported grains, and those in the various foreign countries were not very considerable either. … The preparations for the negotiation of the new commercial treaties which are to replace those which expire on January 1, 1904, were begun in Germany as early as 1897. Immense trouble has been and is being taken by the Government to obtain thoroughly reliable data on which to work, as they were by no means content merely to elaborate a new tariff on the wide experience already gained from the working of the seven commercial treaties of 1891 to 1893."

Diplomatic and Consular Reports of the British Government, January, 1899 (quoted in Monthly Summary of Commerce and Finance

of the United States, January, 1899).

GERMANY: A. D. 1894-1895.

The Emperor and the Social Democrats. His violent and autocratic speeches. Failure of the Anti-Revolutionary Bill. Socialist message to France.

At the opening of the winter session of the Reichstag, in December, 1894, the Emperor, speaking in person, declared it to be "necessary to oppose more effectually than hitherto the pernicious conduct of those who attempt to disturb the executive power in the fulfilment of its duty," and announced that a bill to that end, enlarging the penal provisions of law, would be introduced without delay. This was well understood to be aimed at the Social Democrats, against whom the Emperor had been making savagely violent speeches of late. At Potsdam, in addressing some recruits of the Foot Guards, he had gone so far as to say: "You have, my children, sworn allegiance to me. That means that you have given yourselves to me body and soul. You have only one enemy, and that is my enemy. With the present Socialist agitation I may order you, which God forbid! to shoot down your brothers, and even your parents, and then you must obey me without a murmur." In view of these fierce threatenings of the Emperor, and the intended legislative attack upon their freedom of political expression and action, six members of the Social Democratic party, instead of quitting the House, as others did, before the customary cheers for his Imperial Majesty were called for, remained silently sitting in their seats. For that behaviour they were not only rebuked by the president of the Reichstag, but a demand for proceedings against them was made by the public prosecutor, at the request of the Imperial Chancellor. The Reichstag valued its own rights too highly to thus gratify the Emperor, and the demand was refused, by a vote of three to one. His Imperial Majesty failed likewise to carry the bill the Anti-Revolutionary Bill, as it was called on which

he had set his heart, for silencing critical tongues and pens. The measure was opposed so stoutly, in the Reichstag and throughout the Empire, that defeat appeared certain, and in May (1895) it was dropped. The Emperor did not take his defeat quietly. Celebrating the anniversary of the battle of Sedan by a state dinner at the palace, he found the opportunity for a speech in which the Socialists were denounced in the following terms: "A rabble unworthy to bear the name of Germans has dared to revile the German people, has dared to drag into the dust the person of the universally honoured Emperor, which is to us sacred. May the whole people find in themselves the strength to repel these monstrous attacks; if not, I call upon you to resist the treasonable band, to wage a war which will free us from such elements." The Social Democrats replied by despatching the following telegram to the Socialists in Paris: "On the anniversary of the battle of Sedan we send, as a protest against war and chauvinism, our greeting and a clasp of the hand to our French comrades. Hurrah for international solidarity!" Prosecutions followed. The editor of "Vorwärts" got a month's imprisonment for saying the police provoked brawls to make a pretext for interference; Liebknecht, four, for a caustic allusion to the Emperor's declarations against Socialism, and for predicting the collapse of the Empire; and Dr. Forster, three, for lèse-majesté.

GERMANY: A. D. 1894-1899.

The Emperor's claim to "Kingship by Divine Right,"

A great sensation was produced in Germany by a speech addressed on September 6, 1894, by the German Emperor to the chief dignitaries and nobles of East Prussia in the Royal Palace at Königsberg. The following are the principal passages of this speech:

"Agriculture has been in a seriously depressed state during the last four years, and it appears to me as though, under this influence, doubts have arisen with regard to the

fulfilment of my promises. Nay, it has even been brought home to me, to my profound regret, that my best intentions have been misunderstood and in part disputed by members of the nobility with whom I am in close personal relation. Even the word 'opposition' has reached my ears.

{241}