Introduction

SONG KING AS MEDIUM

S

TANDING with his back to the Yellow River and a crowd of eager eyes, ears, and cameras fanned out in front of him, he asked us offhandedly, “What shall I sing?” His audience included local officials intent on advertising the region through its cultural productions, scholars from other parts of China interested in documenting this regional culture, foreign scholars such as myself eager to experience and study “authentic” Chinese folk culture with video cameras and audio recorders in hand, a cameraman from a local TV station filming the scholars’ filming of the performance, and assorted locals who had come to see what all the excitement was about.1 After a moment of hesitation, the singer continued, “How about ‘Going beyond the Western Pass’?” He began to sing,

Dearsis—aihei—sister,ai, Don’tyoucryforme.

Ifyoucry,Ican’tenduretheacheinmyheart, Atsixesandsevens,allinabustle,myheart’sindeeptrouble.

Heavenhasmetwithdisaster , Thefivegrainsarewitheredandevengrassdoesn’tgrow.

Ifonedoesn’tgobeyondtheWesternPass, Thedaysofthepooraretrulynumbered.2

Full of emotion, the song is ostensibly about a poor farmer forced to leave his loved one and find work in Inner Mongolia, but it seems to straddle layers of meaning—personal, local, historical, and national. The singer—Wang Xiangrong 王 向 荣 (b. 1952)— would later tell me about various associations he had with this song at different points in his life. Under the cloak of the traditional, he was able to infuse the song with thoughts and feelings about people he had known in the past and even a TV drama he had seen in recent years.

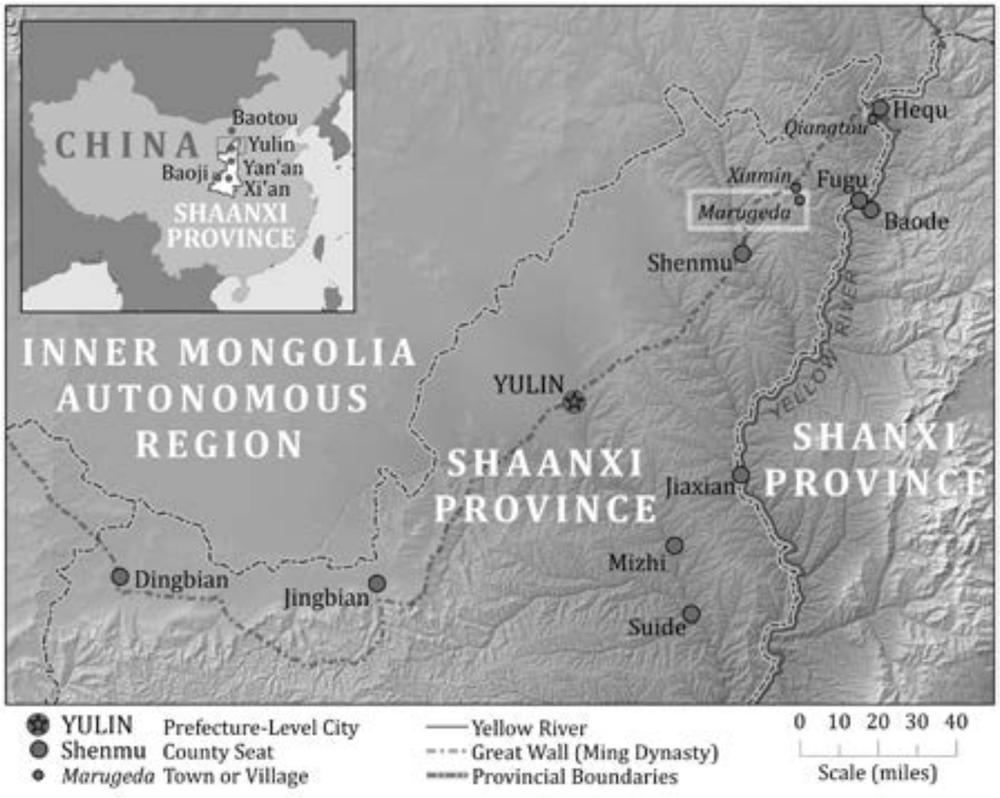

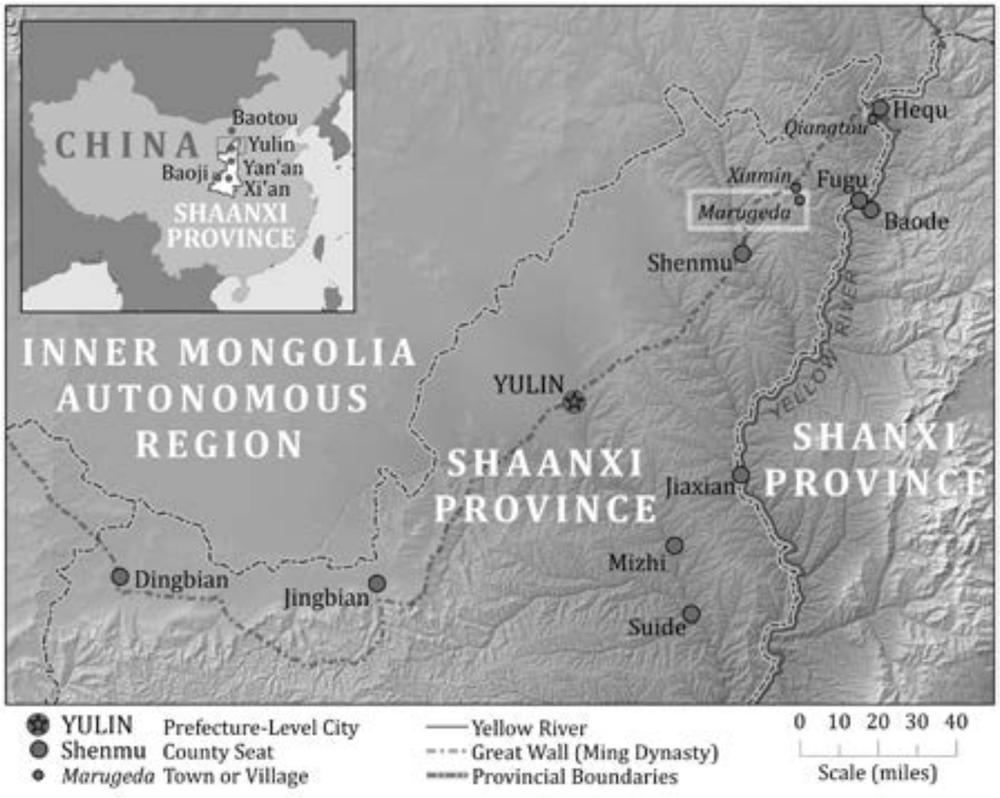

Wang spent his childhood in a small mountain village near the intersection of the Great Wall and the Yellow River. He has journeyed on to become, first, “Folk Song King of Northern Shaanxi Province,” and later, “Folk Song King of Western China.” During the course of his career, Wang’s life, songs, and performances have come to highlight various facets of social identity in contemporary China.3 After winning regional contests in the late 1970s and a national contest in Beijing in 1980 where he met Deng Xiaoping, Wang was hired by a regional song-and-dance troupe, traveling on regional, national, and international tours (Zhao Le 2010). He later relocated to the provincial capital of Xi’an, assumed positions of power in several associations, and was selected as a National-Level Representative Transmitter for the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Northern Shaanxi Folk Songs in 2009 (5).4

When itinerant singers from the countryside become iconic artists, worlds collide. The lives and performances of representative singers such as Wang become sites for conversations between the rural and urban, local and national, folk and elite, and traditional and modern.5 As border walkers who move from place to place, these singers straddle different groups, connecting to diverse audiences by shifting between amorphous, place-based, local, regional, and national identities, and becoming representative symbols in the process. These singers embody

connections between different “heres” and “theres,” offering audiences a range of viewpoints and desires to engage with— exchanges that allow audience members to resituate themselves in the larger scheme of things. This book examines the life and performances of Folk Song King of Western China Wang Xiangrong to look at how itinerant performers present audiences with traditional, modern, rural, and urban “selves” and “Others” among whom to continually redefine themselves in an evolving world. By looking at how one iconic singer has adapted and mediated between different audiences on a micro level in speech and song in specific events and connecting the insights gained to other singers in China and around the world, this book suggests that itinerant singers become iconic by modeling the socialization of self to diverse audiences.

The song Wang sang that day by the Yellow River in 2006 brought together personal and social meanings, doing so in unique ways for each audience member. The “traditional” songs Wang sings in performances act as vessels—held up for all to see —encompassing a mélange of public and private emotions. The song he performed that day also served as a marker distinguishing different groups (e.g., local, regional, national, human) against the backdrop of others. As we listened to Wang, the territory on the other side of the Yellow River (Shanxi Province) was distinct from the banks of Shaanxi Province on which we stood. Wang’s song about a local migrant traveling to neighboring lands embodies local and regional identities within northern Shaanxi Province on one hand, while also bridging the two provinces and a third on the river’s edge. Wang’s position facing us on “this” side of the bank, in this context, was emblematic of iconic Chinese folk singers— referred to as “song kings” (gewang 歌 王 ) and “song queens” (gehou 歌 后 ). Facing each group from the group’s edge, these singers enact exchanges between perspectives with the goal of redefining senses of self.

Places mentioned in the book.

In many ways, singing a traditional song with a symbolic backdrop behind and a diverse audience in front is a typical setup for Wang and other iconic singers. The singers project their powerful voices toward each audience, blending together with the visual and conceptual backdrops behind the singers and their songs, presenting a fusion of the personal and social, the individual and the collective to those seated before them. Through the lives, personas, and songs of these song kings and queens, they bring together what lies behind and what sits in front—they serve as mediums between worlds. Acting as cultural mediators (cf. Filene 2000; Harker 1985), folk songs and folk singers can express the unity and diversity of a nation and/or various ethnic groups (cf. Gorfinkel 2012; Meeker 2013). As singers such as

Wang Xiangrong move from place to place and adapt material from one context to another, they take on interstitial identities, making them well suited to become representatives of larger and larger constructed regions with fuzzy borders—from locality to region to nation. In areas of the world such as China with increasing divides between countryside and city, these singers offer a sense of contact between urban centers and rural peripheries.

If the story of the song king is about mediating between what is figuratively behind the singer and who is seated in front, my place throughout this book is hovering at Wang’s side, watching how it is done. During my fieldwork with Wang Xiangrong and other singers and scholars in Xi’an and various localities in northern Shaanxi Province in 2006, 2010, and especially 2011 to 2012, I documented Wang’s performances in Xi’an and northern Shaanxi to see how he presented his active repertoire to a variety of audiences in different ways, interviewed Wang extensively about his life and songs, and translated those songs line by line into English. Much of my fieldwork involved looking at how Wang spoke to different audiences before, during, and after his songs. Sometimes, the performance contexts to which I accompanied Wang surprised me—they included weddings, business openings, and even Christmas concerts, in addition to more “mainstream” performances in official Chinese New Year celebrations and school anniversaries. Throughout, I combined a singer-centered approach with historical research on northern Shaanxi folk songs and singers, attempting to see connections across time and space. That day by the Yellow River in the summer of 2006, behind Wang lay a symbolic river and an Other territory beyond, each providing a metaphorical framework for the song’s performance. The song’s origins lay in the past—how far back, we did not know and the song would continue to be sung for years to come, just as the river’s waters came from somewhere sight unseen, heading

onward toward an unseen destination. Between the horizons of origin and end stood the singer. His song, projected at us, was rooted in past performances and tradition—the river’s source— while simultaneously projecting desires for us to move toward if we so chose. Rivers suggest movement—the passage of time—but also a stillness within that movement, moments where we focus on the “now” connecting what has been and what will be, calling to mind where we come from and where we are going, offering us an opportunity to consider how our lives fit into a larger “stream” of events.6

Rivers, like songs, also bring to mind other places.7 Their waters originate in some other place and flow off to yet another place. Just as the river’s image encourages us to consider the past and future, it also asks us to think about our relationships with other places. Song kings and queens, as I go on to suggest, are like rivers—each singer originating in one place and meandering through many other places, carrying elements of their origins while adjusting those elements to each new surrounding. Iconic singers offer audiences opportunities to reflect on the past and the future, as well as the audience’s geographical and social location in the world. The songs of these kings and queens, like the river’s water flowing by us, are both physically “here,” arriving and adapting to our local banks and climate, and metaphorically “there,” coming from and reflecting other places and times.

The image of the Yellow River has served as a symbol during important moments in China’s history, a site for public conversations much like the songs Wang sings and aspects of his life as a song king. During my fieldwork in 2011 and 2012, Wang would often accompany his performances with video images of the gushing, rushing waters of the Yellow River projected on LCD screens at the back of each stage. Depending on the event and its organizers, other images were also present: Chinese flags waving in the wind; celebratory messages for Christmas, Chinese New

Year, or the opening of a new business; images of revolutionary martyrs; a large portrait of Mao Zedong; and the wedding photo of a new couple, to name a few. Similar to the Yellow River’s symbolic image framing Wang’s performance back in 2006, these other images contributed to the interpretive contexts for each of Wang’s performances. In addition, Wang’s appearance as an experienced, older singer called to mind the past, reinforcing the nostalgic qualities of his speeches, songs, and the river imagery itself.

Like the river, the Other territory behind Wang offered a similar combination of meanings. While Wang’s song meant different things to different people, it presented some aspect of otherness to each audience member in a relatable way. What was “behind” Wang’s song depended in part on the observer. It could be another place, another time, or both. What really sits “behind” a singer as he or she performs? Sometimes, the audience sees the singer’s elusive hometown—a place that may no longer exist except in the memory of song, such as the small mountain village where Wang was born near the intersection of the Great Wall and the Yellow River, Marugeda. At other times, the audience sees a larger region—a county, a prefecture, a province, perhaps even a nation. They might see the history of a place or people. They might also see the personal history of the singer as he or she moves through time and space. The audience may see themselves reflected back or an exotic Other—another place, people, or time presented for their consideration. Sometimes, what the audience sees is a mixture of all of the above.

The diverse audiences that sit before iconic singers have different needs and expectations. Wang and other song kings and queens, similar to legendary singer-heroes of the past, offer local audiences a symbol of place-based identity and a means of selfexpression. These singers’ itinerant experience means that the sense of local authenticity they bring has traveled through space

and time and returned home, validated by people in other areas of China, foreigners, and the news media. Regional audiences look to these singers as embodiments of the region performing songs that unite disparate localities into a common whole, while connecting the local to the nation. National audiences see these singers as incarnations of Chineseness who also provide evidence of the nation’s diversity—bridging regions, the common people, and the elite. For foreigners and some foreign scholars, song kings and queens offer an “authentic” Chineseness rooted in a particular place—both culturally unique and resonating with a sense of our common humanity.

In the singers’ performances, each of these audiences finds a combination of the familiar and the exotic against which to form a sense of identity, socializing the personal, relating the individual to the collective, and delineating communities—identifying who “they” are as individuals and groups and who “they” are not. The worlds that singers create in song with diverse imagery and sung personae serve as vessels of desires, emotions, and points of view with which audience members can choose to align themselves or distinguish themselves from, moving freely between subjectivities as they explore how that movement feels. In the stories of the singers’ lives and their performances of region-representing and nation-representing songs, song kings and queens embody fuzzy personae providing sites for audiences to merge individual and collective desires.8 The personae in those songs—both voices heard and entities addressed—offer models of individuals who embody collective experiences. A peasant singer praises Mao Zedong and China. A rural lover describes how difficult it is to get together a message that applies as much to sweethearts as to urban residents in the throes of modernity.

Moving between places, song kings and queens bridge social groups. When I interviewed Wang Xiangrong later in 2010, he suggested that two target demographics for his 2006 CD were

“common people” (laobaixing) and “high-level” intellectuals, the latter of which included music scholars.9 His performance by the Yellow River included both groups. These two demographics—folk and elite—suggest a range of people who individually find their own meanings in his songs. Wang’s singing, then, attempts to bridge the popular and elite, insider and outsider, here and there, and familiar and exotic. While we might imagine a spectrum of performance contexts from local village performances to national and international extravaganzas, the events “in between” shed light on some of the most interesting aspects of performance. Just as audiences evaluate performances, deciding what is successful and what is not, performers “read” their audiences, determining what each audience might appreciate and sometimes playing with their audiences’ assumptions. Performers strive to craft performances appreciated by the diverse audiences who sit before them—country people and city people, those from this part of the province and that part of the province, those from this province and other parts of China, as well as Chinese and foreigners. Ideal performances push and pull each audience, bending without breaking them, playing with their expectations in order to make them sit up and take stock of who they are and where they stand.

In doing so, song kings and queens place various realms in relation to one another, providing an order to the universe like Chinese kings of old (D. Howard Smith 1957, 183). Social order within and across groups is based on networks of relationships. Kings provided a focal point for the interaction of socially relevant groups of the time—heaven, earth, other kingdoms, other peoples —and in doing so gave individuals and groups a means of interacting with and defining themselves in relation to others. Chapter 1 notes that legendary singer-heroes of the past known as “song gods” and “song goddesses” acted as intermediaries between the mundane and the divine, an idea that continues with rural spirit mediums in the twentieth century, one of whom was a

childhood role model of Wang Xiangrong, discussed in chapter 2.10

Standing between the earthly and godly, these legendary singers had dual identities allowing them to mediate between realms, participating in each without fully belonging to any. People referred to these singer-intermediaries as “demigods” (banxian 半 仙 , literally “half-immortals”) and “almost emperors,” suggesting their ability to bridge social groups (Schimmelpenninck 1997, 103–104, 107). Wang Xiangrong and other iconic folk singers seem to share a similar dual identity. Wang has said that he continued to be “half a peasant” (bangenongmin 半个农民) after becoming an urban-based song king.11 Over the course of this book, I argue that song kings and queens serve as intermediaries providing a sense of continuity amidst change (Van Gennep 1960).

Singers as Mediums

The lives, personas, and songs of iconic singers mediate between what lies “behind” the singers and their audiences in front. As with the case of Wang Xiangrong, the life stories of song kings and queens form powerful iterations of symbolic archetypes (cf. Bantly 1996; Pearson 1984). The dual identities of these singers—they are both folk and elite—authorize them to represent groups and connect those groups through performance, highlighting social tensions of the day and overcoming those tensions through song. The movement of itinerant singers is crucial to their ability to set up conversations between groups. The singers’ movement between worlds—Wang’s move from Marugeda to Yulin City highlights differences and similarities between the countryside and the city, as well as traditional and modern life. In a constantly evolving world, this ability to facilitate dialogues places iconic singers at the center of “a crucial part of the processes of change” (Attinasi and Friedrich 1995, 47). Song kings and queens

negotiate different points of view and serve as intermediaries offering audiences smooth transitions through social tensions and changes.

The life stories of these singers provide models for incorporating the personal into the social. The symbolic power of stories about song kings and queens often stems from the ways in which particular anecdotes and themes resonate with earlier stories about other powerful singers. In stories about Wang’s life, we see elements resonating with the life narratives of other contemporary singers as well as precedents set in the tales of legendary singer-heroes (Gibbs 2011). This resonance in the stories brings together two levels of meaning. These narratives are the experiences of an individual, but they are also “more than” the experience of an individual (Shuman 2005, 4).12 As Amy Shuman notes, “for a story to be understood at all, it must be recognizable as a shared experience” (27). Wang’s ability to bridge the personal and social is further accentuated in his performances. As we will see, through speech and song Wang brings together parallel narratives about overcoming obstacles—personal, regional, national, lyrical—socializing the individual and encouraging audiences to do the same.

The stories of song kings and queens, then, like the songs they sing, form sites of public discourse about social issues of the day— a position both of power and precariousness. As singers cross borders during their careers, they encounter different ways of thinking about issues that matter, and the stories of the singers’ lives embody choices about the best ways forward. Similar to narratives about other song kings and queens and mythological singer-heroes of the past, the aspects of Wang’s life drawing particular attention in articles, books, and documentaries highlight social tensions relevant to a wide range of audiences. These tensions often point to contradicting public mores between folk and elite—differing opinions about how one should act in society.

The stories of iconic singers place personal actions in conversation with the expectations of different groups. Obstacles encountered by legendary singer-heroes in earlier tales often revolved around tensions between folkways and Confucian morality. Many of the obstacles faced by both ancient and contemporary singer-heroes have to do with ideas about love, sex, and marriage, perhaps due to a long-standing connection between singing and courtship. We also see conflicts of class and, more recently, the rural-urban divide reflected in issues of language, gesture, and singing style. While the focus of criticism is on performance, the underlying tensions connect to broader social issues.

Many of the anecdotes in life stories about iconic singers present singing as a means of representing and negotiating between different viewpoints. The singers’ stories show the singers using song to overcome obstacles, gain respect, and negotiate between groups. The singers’ dual identities allow them to connect to and maintain a distance from their audiences. As both “common people” and elite cultural figures, song kings and queens bridge class, space, and time. They stand on the border of groups, positioning themselves as both insiders and outsiders and using that stance to authorize their construction of song worlds where different viewpoints are exchanged. In addition to performing songs representing particular groups, we see stories of iconic singers modeling how to sing as they teach people songs. During the journeys of these iconic singers, as they learn to adapt their senses of self after encountering Others, they come to share what they have discovered with audiences through representative performances and instructive models. As these singers present audiences with a range of familiar and exotic “selves” and “Others,” they offer audiences the opportunity to redefine themselves through interactions with each persona, providing individual and group dialogues with difference.

At the same time, some audiences may disapprove of the models that song kings and queens provide for the meeting and merging of subjectivities. Each iconic singer stands with one foot inside and one foot outside of different groups, and that precarious, interstitial position often leads the singer’s representative authority to be questioned. As groups are heterogeneous and borders often ambiguous, for everyone who might crown a singer “king” or “queen,” there are others who decry the singer as a fraud. If a singer becomes too engaged in presenting a local tradition to others, people from their home region may find them too cosmopolitan and argue that they have lost their local essence and no longer merit representing the group. If, on the other hand, the singer is too local, outsiders may consider him or her parochial, and he or she will fail to mediate between groups. As identities evolve in tandem with changing relations between places, singers’ designations as song kings and queens are forever contestable and always in flux.

Whether one designates a singer “song king” or “song queen” or denounces them as “interlopers” or “sellouts” is tied to individual audience members’ sense of identity and whether the singer’s representation aligns with that sense (Malone 2011, 2; cf. Titon 2012; Graeme Turner 2004). Objections to a singer’s representativeness revolve around aspects of the singer’s persona and performances that the critics feel diminish the “authenticity” of the songs, people, and places the singer is said to represent. The objection may be because, for example, the singer comes from a different place than the songs she purports to represent; because he grew up in the city, yet chooses to sing songs from the countryside; or because she uses a vocal style the critic feels unfairly represents the broader tradition. Critics who contest a singer’s status as “song king” or “song queen” are in effect positioning themselves in relation to larger groups—identifying with certain groups while distancing themselves from others. By

judging the representativeness of these singers, we declare who we are and who we are not, as well as who I am and who I am not. While no singer is beyond reproach, successful singers must learn to pivot between audiences, glossing over heterogeneity to construct tangible, symbolic personae that diverse audiences can relate to.

Songs as Public Conversations

The song Wang sang by the Yellow River that day presented the audience with a tapestry of meanings connected to the contexts of previous performances, situating the performed present within a historical continuum. The performances of iconic songs constitute continuous public conversations about important issues of the day —issues that change over time as society changes—forming a site for public memory (cf. Nora 1989) and the socialization of personal experience (DuBois 2006; Porter and Gower 1995). The desire for dialogue inherent to lyric song involves what Thomas DuBois calls “the communicative nature of lyric” (97). This desire seems to be rooted in a yearning for conversations with Others that in turn constitute the self. Our eagerness to travel and explore new places, peoples, and cuisines, to read novels and watch films about other places and times, to talk with people from different backgrounds, and to attend performances of dance and music—all of these lead us to notice what is familiar and different, and adjust our position accordingly. Similarly, when songs are presented from one place to another, they offer the possibility for diverse parties to meet on common ground and discuss different ways of seeing things.

The goal of such exchanges is to merge different subjectivities and find a new point of view representing a socialized self. This pattern of merging subjectivities is repeated over and over in

many of Wang’s songs, stories, and performances I discuss throughout this book. We see banquet attendees coming together to “strengthen their feelings,” villagers communing with local gods in conversations about health and propriety, and couples exploring new terrains, sharing perspectives as a new relationship—and point of view—emerges. At the same time, we see examples of how failing to reach out to others is criticized. Songs about men and women who do not call out to others and set up mutually validating exchanges lament the failure of those individuals to secure their continued existence. If part of one’s existence stems from being recognized by and forming a sense of self in conversation with others, individuals who fail to engage with others soon cease to exist.

The power of song kings and queens such as Wang is that they can create entire song worlds filled with conversing desires, ephemeral yet iterable realms populated by voiced and unvoiced personae. As those personae move through and respond to each song world, their performed desires form public conversations that audiences can join in on. At the same time, the song’s personae, inflected by the singer’s persona, test the audience’s fluid notions of self and Other.13 Each sung persona allows the performer to play different roles and express different types of sentiments (Fong 1990), presenting a mixture of the familiar and exotic experienced differently by each audience member. These personae provide crucial contexts that allow singers to sing what they otherwise could not and audiences to hear those lyrics in an appropriate manner. The persona of a boatman, muleteer, or revolutionary peasant singer can say things that other personae cannot. Furthermore, a persona’s specificity or ambiguity can either directly address social tensions when desired or gloss over them when necessary to bridge divergent views and groups in order to bring those groups together into a larger whole.

Wang’s broader repertoire of songs contains various sung personae—a muleteer, a migrant farmworker, a cowherd, a woman returning to her natal home during festival time, an audacious playboy, a pair of tender peasant lovers, a guest at a drinking party, a Mongol man and his female Han lover, a spirit medium (shenhan 神汉) and the spirit to whom the medium gives voice.14 In some of Wang’s more recent creations—such as his a cappella version of “The East Is Red” discussed in chapter 3 or his iconic “The Infinite Bends of the Yellow River” discussed in chapter 7—a song’s persona may travel through different historical periods, offering audiences a sense of history and their place in it. By comparing the personae of Wang’s childhood songs with those of the songs he performed later during his career as a representative singer, we are able to get a glimpse of how sung personae are connected to places large and small and how more specific, local personae can be developed into larger, more ambiguous, regionand nation-representing personae. During this process, the meaning embodied by the lyric “I” grows. In Wang’s childhood songs that I examine in chapter 2, the “I’s” of each song evoke the roles of individuals who are recognizable in the village, such as banquet hosts and guests, spirit mediums, and young people. As Wang’s repertoire expanded to include the region-representing songs discussed in chapter 3, the “I’s” in songs such as “Pulling Ferries throughout the Year” and “The East Is Red” become representative individuals singing on behalf of the People. By the time we reach Wang’s iconic “The Infinite Bends of the Yellow River” in chapter 7, one of the many layered meanings of the song’s “I” becomes that of the audience and the singer joined together through song into a collective “we.”

In all of Wang’s songs, the sung personae offer listeners different Others with whom to interact and gauge their senses of self. When an audience member hears a migrant farmworker sing about traveling to Inner Mongolia to find work, he or she may

reflect upon what it means to stay behind and what it would be like to leave. Hearing the voice of a local spirit sung through a medium, the listener feels the spirit’s presence and hears its instructions on how to cure an illness, perhaps leading the listener to consider the relationships between people and gods. When one hears a love duet sung between male and female personae, one may choose to identify with the man, the woman, both, or neither. In each case, the listener positions him-or herself in relation to the others.

In addition to these voiced sung personae, there are also other, voiceless personae—the silent, looming addressees to whom the singer calls out. In Wang’s a cappella version of “The East Is Red,” he calls out to the East and the sun, addressing each as “you.” In another song about a tragic story from China’s pre-1949 past, Wang calls out to a woman who committed suicide. The act of calling out to an Other, of singing to an addressee who is physically absent yet tangibly present in the constructed world of song, has the effect of internalizing the external—another time, place, idea, or person—summoning that intangible Other into the present “time of discourse” for the singer and listeners (Culler 2015, 225). In doing so, the singer’s act of calling out pulls both singer and listeners toward a desire connected to the song’s addressee. For example, calling out to a deceased female relative can express the desire to indict the tradition of arranged marriage. Calling out to the East or the sun can represent a desire for the warmth of national community.

As singers address these Others, they set up mutually defining conversations. On the one hand, the singer constructs the Other through the singer’s address (Althusser 2001). A peasant singer praising the greatness of Chairman Mao constructs Chairman Mao’s greatness as the singer calls out to him. A male sung persona constructs the tragedy of a deceased woman as he calls out to her. At the same time, the singer’s persona is also

constructed through the act of calling out to an Other (Frith 1996b, 183). By calling out to the dead woman in the example above, the male sung persona shows that persona’s concern and despair. By calling out to Chairman Mao, the peasant singer persona in the earlier example constructs himself as a representative of the People. Though these exchanges are seemingly one sided—only the singer is physically present and heard—the act of address suggests a conversation that audiences can observe and join in on, identifying with the sung persona or the addressee, or choosing to stand on the sidelines (cf. Fiske 2011).

What makes these conversations unique is that they take place in front of an audience. The singer “addresses both his [or her] audience and the interlocutor of the story” via a “double directionality” (Frankel 1974, 262; Gilman 1968). Jonathan Culler (2015, 8) calls this “triangulated address,” where audience members are free to position themselves at varying distances from the various personae on display (cf. Fiske 2011).15 Just as the singer is both within and outside of the sung personae he or she embodies, the audience can also choose to identify with or objectify those personae—what John Fiske calls “implicating” and “explicating” (2011, 174–175). Allowing us to be both inside and outside of those personae with the freedom to shift between the two positions, lyric song offers us the experience of subject positions from within and without, without fully committing —“being of two minds” (Brown 2004, 133; cf. Samei 2004, 7). We as the audience have the freedom to choose, as well as the freedom not to choose—floating in between, saying while not saying, agreeing yet not agreeing.

In Wang’s performances and those of other iconic itinerant singers, the singers adapt the in-betweenness of their lives, personas, and songs to each audience as they model the meeting and merging of self and Other. Mediating between the rural and

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

1795. No. 1. Same type as the Eagle; size, 16.

1795. No. 2. Obverse: Same.

Reverse: An eagle, wings extended upwards, with the United States shield upon its breast, a bundle of thirteen arrows in the right talon, and an olive branch in the left. In its beak, a scroll inscribed “� �������� ����.” Around the head are sixteen stars, and above is a curved line of clouds extending from wing to wing. “������ ������ �� �������.”

1796. Same as No. 1 of 1795; fifteen stars on obverse.

1797. No. 1. Same as No. 1 of 1795.

1797. No. 2. Same, with sixteen stars on obverse.

1797. No. 3. Obverse: Same, with fifteen stars.

Reverse: Same as No. 2 of 1795, sixteen stars around the eagle.

1798. No. 1. Same as No. 1 of 1795, with thirteen stars.

1798. No. 2. Obverse: Same.

Reverse: Same as No. 2 of 1795, thirteen stars.

1799 and 1800. Same as No. 2 of 1795, with thirteen stars on the obverse.

1801. None issued.

1802 to 1806, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1795, with thirteen stars on the obverse.

1807. No. 1. Obverse: Same as No. 1, 1795, with thirteen stars.

Reverse: Same as No. 2, 1795.

1807. No. 2. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left; bust, draped, wearing a kind of turban with a band in front inscribed “�������,” thirteen stars, and date.

Reverse: An eagle, with the United States shield upon its breast, an olive branch and three arrows in the talons. Above, a scroll, inscribed “� �������� ����.” United States of America “5. D.”

1808 to 1812 inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1807.

1813 to 1815, inclusive. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left, wearing a kind of turban, a band in front inscribed “�������.” Thirteen stars and date. No shoulders.

Reverse: Same as No. 2 of 1807.

1816 and 1817, inclusive. None issued. 1818 to 1828, inclusive. Same as 1813.

1829. No. 1. Same as 1813; size, 16.

1829. No. 2. Same, but smaller; size, 15.

1830 to 1833, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1829.

1834. No. 1. Same as No. 2 of 1829.

1834. No. 2. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left, hair confined by a band inscribed “�������.”

Reverse: Same as No. 2 of 1807, without the motto “� �������� ����” omitted; size, 14.

1835 to 1838, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1834.

1839 to 1865, inclusive. Same type as the Eagle of 1838. 1866. Same type as Eagle of same date.

Three-Dollar Piece.

Authorized to be coined, Act of February 21, 1853. Weight, 77.4 grains; fineness, 900.

1854. Obverse: An Indian head, wearing a crown of eagle feathers, on band of which is inscribed “�������”—“������ ������ �� �������.”

Reverse: “3 dollars 1854” within a wreath of corn, wheat, cotton, and tobacco. Size, 13.

Quarter-Eagle.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 67.5 grains; fineness, 916⅔. Weight changed, Act of June 28, 1834, to 64.5 grains. Fineness changed, Act of June 28, 1834, to 899.225. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900.

1796. No. 1. Obverse: Liberty head, facing right, above “�������”—sixteen stars.

Reverse: Same type as No. 2 half-eagle of 1795, size 13.

No. 2. Same, with no stars on obverse.

1797-1798. Same as No. 1 of 1796, with thirteen stars.

1799-1801, inclusive. None issued.

1802. Same as 1798.

1803. None issued.

1804 to 1807, inclusive. Same as 1798.

1808. Same type as No. 2 half-eagle of 1807, with “2½ D.”

1809 to 1820, inclusive. None issued.

1821. Obverse: Same type as the half-eagle of 1813, size 12.

Reverse: Same type as No. 2 half-eagle of 1807.

1822 and 1823. None issued.

1824-1827, inclusive. Same as 1821. 1828. None issued.

1829 to 1833, inclusive. Same as 1821.

1834. No. 1. Same as 1821. No. 2. Same type as No. 2 half-eagle of 1834, size 11.

1835 to 1839, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1834. 1840 to 1865. Same type as the eagle of 1834. 1866. Same type as eagle of 1866.

Dollar.

Authorized to be coined, Act of March 3, 1849. Weight, 25.8 grains; fineness, 900.

1849 to 1853, inclusive. Obverse: Same type as the eagle, without date.

Reverse: “1 ������ 1849” within a laurel wreath, “������ ������ �� �������.” Size 8.

1854. No. 1, Same. No. 2. Same type as the three-dollar piece, size 9.

S�����.

Dollar.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 416 grains; fineness, 892.4. Weight changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 412½ grains. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 12, 1873. Coinage reauthorized, Act of February 28, 1878.

1794. Obverse: Liberty head, facing right, flowing hair, fifteen stars; above, “�������;” beneath, “1794.”

Reverse: An eagle with raised wings, encircled by branches of laurel crossed; “������ ������ �� �������.” On the edge, “������� �����, ��� ������ �� ����.” Size, 24.

1795. No. 1. Same.

1795. No. 2. Bust of Liberty, facing right, hair bound by a ribbon, shoulders draped, fifteen stars.

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings, standing upon clouds, within a wreath of palm and laurel, which is crossed and tied. “������ ������ �� �������.”

1796. Same as No. 2, of 1795.

1797. No. 1. Same as No. 2 of 1795, with sixteen stars, six of which are facing.

1797. No. 2. Same, with seven stars facing.

1798. No. 1. Same as No. 2 of 1795, with fifteen stars.

1798. No. 2. Same, with thirteen stars.

1798. No. 3. Obverse: Same, with thirteen stars.

Reverse: An eagle with raised wings, bearing the United States shield upon its breast, in beak, a scroll inscribed “� �������� ����.” A bundle of thirteen arrows in the right talon, and an olive branch in the left. Above, are clouds, and thirteen stars. “������ ������ �� �������.” Size, 25.

1799 to 1804, inclusive. Same as No. 3, of 1798.

1805 to 1839, inclusive. None issued.

1840 to 1865, inclusive. Obverse: Liberty seated upon a rock, supporting with her right hand the United States shield, across which floats a scroll inscribed “�������,” and with her left the staff and liberty cap; beneath, the date.

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings, bearing the United States shield upon its breast, and an olive branch and three arrows in its talons. “������ ������ �� �������.” “��� ���� ” Reeded edge; size, 24.

1866 to 1873, inclusive. Same, with a scroll above the eagle, inscribed, “�� ��� �� �����.”

1874 to 1877, inclusive. None issued.

1878. Obverse: Liberty head facing left, upon which is a cap, a wheat and cotton wreath, and a band inscribed “�������;” above, “� �������� ����;” beneath, the date. Thirteen stars.

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings pointing upwards; in right talon an olive branch with nine leaves; in the left, three arrows. In the field above, “�� ��� �� �����;” beneath, a semi-wreath, tied and crossed, reaching upwards to the wings; “������ ������ �� �������.” Some pieces of the above date (1878) were coined with eight feathers in the tail during the year, but seven have been adopted.

Trade Dollar.

Authorized to be coined, Act of February 12, 1873. Weight, 420 grains; fineness, 900.

1873. Obverse: Liberty seated upon a cotton bale, facing left; in her extended right hand an olive branch; in her left a scroll inscribed “�������;” behind her a sheaf of wheat; beneath, a scroll inscribed “�� ��� �� �����;” thirteen stars; “1873.”

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings; in talons three arrows and an olive branch; above, a scroll inscribed “� �������� ����;” beneath, on field, “420 grains;” “900 fine.” “������ ������ �� �������.” Size, 24.

Half Dollar.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 208 grains; fineness, 892.4. Weight changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 206¼ grains. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900. Weight changed, Act of February 21, 1853, to 192 grains. Weight changed, Act of February 12, 1873, to 12½ grammes, or 192.9 grains.

1794 and 1795. Same type as the dollar of 1794. On the edge, “F���� ����� �� ���� � ������.” Size, 21.

1796. No. 1. Same type as No. 2, dollar of 1795, with the denomination, “½,” inscribed on the base of the reverse. No. 2. Same, with sixteen stars on the obverse.

1797. Same as No. 2, of 1796.

1798 to 1800, inclusive. None issued.

1801 to 1803, inclusive. Same type as No. 3, dollar of 1798.

1804. None issued.

1805 and 1806. Same as No. 3, dollar of 1798.

1807. No. 1. Same.

No. 2. Obverse: Liberty head facing left, wearing a kind of turban, with “�������” inscribed upon the band. Thirteen stars and date.

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings pointing downwards, bearing upon its breast, the U. S. Shield, an olive branch and three arrows in its talons; above, in the field, a scroll inscribed “� �������� ����;” beneath 50 �. “������ ������ �� �������.”

1808 to 1835 inclusive, same as No. 2 of 1807.

1836. No. 1. Same as No. 2 of 1807.

No. 2. Obverse: Same.

Reverse: An eagle with expanded wings pointing downwards, the U. S. shield upon its breast, an olive branch and three arrows in its talons, “������ ������ �� �������,” reeded edge.

1837. Same as No. 2 of 1836.

1838. Obverse: Same as No. 2 of 1836.

Reverse: Same; “���� ���.” for “50 �.”

1839. No. 1. Same as 1838.

No. 2. Same type as dollar of 1840.

1840 to 1852 inclusive, same.

1853. Obverse: Same with an arrow head on each side of the date.

Reverse: Same, with a halo of rays around the edge.

1854. Same, without the rays.

1855. Same.

1856 to 1865 inclusive, same, without the arrow heads.

1866 to 1872 inclusive, same, with scroll above the eagle inscribed “�� ��� �� �����.” (Some have been occasionally met with, which have been issued by the San Francisco Mint, without this legend in 1866.)

1873. No. 1. Same.

No. 2. Same, with arrow heads on each side of the date.

1874. Same.

1875. Same, without the arrow heads.

Quarter Dollar.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 104 grains; fineness, 892.4. Weight changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 103½ grains. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900. Weight changed, Act of February 21, 1853, to 96 grains. Weight changed, Act of February 12, 1873, to 6¼ grammes, or 96.45 grains.

1796. Same type as No. 2 dollar of 1795, with reeded edge; size, 18; fifteen stars.

1797 to 1803. None issued.

1804 to 1807, inclusive. Same type as No. 3 dollar of 1798, beneath, “25c.”

1808 to 1814, inclusive. None issued.

1815. Same type as No. 2 half dollar of 1807.

1816 and 1817. None issued.

1818 to 1825, inclusive. Same type as No. 2 half dollar of 1807, size 17.

1826. None issued.

1827 and 1828. Same type as No. 2 half dollar of 1807.

1829 and 1830. None issued.

1831 to 1837, inclusive. Same type as half dollar of 1807, with the diameter reduced from size 17 to size 15, and a corresponding increase in thickness and decrease of the size of devices, and the omission of the scroll, inscribed “� �������� ����.”

1838. No. 1. Same as 1837. No. 2. Same type as the dollar of 1840, with “����. ���.” for “��� ����.”

1839 to 1852, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1838.

1853. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with arrow heads on each side of date, and a halo of rays around the edge.

1854 and 1855. Same, without the rays.

1856 to 1865. Same, without the arrow heads.

1866 to 1872, inclusive. Same, with the scroll above the eagle, inscribed “�� ��� �� �����.”

1873. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with an arrow head on each side of the date.

1874. Same.

1875. Same, without the arrow head.

Twenty-Cent Piece.

Authorized to be coined, Act of March 3, 1875. Weight, 5 grammes, or 77.16 grains; fineness, 900. Coinage discontinued, Act of May 2, 1878.

1875 to 1878, inclusive. Obverse: Same type as the dollar of 1840.

Reverse: An eagle with displayed wings, three arrows, and an olive branch, two of the leaves of which nearest the stem, together with those drooping from the centre, overlap; the terminating leaves on the end of the branch, however, do not. On each side a star. Plain edge. “������ ������ �� ������� ” “������ ����� ” Size, 14.

Dime.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 41.6 grains; fineness, 892.4. Weight changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 41¼ grains. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900. Weight changed, Act of February 21, 1853, to 38.4 grains. Weight changed, Act of February 12, 1873, to 2½ grammes, or 38.58 grains.

1796. Same type as the No. 2 dollar of 1795; size 13; fifteen stars.

1797. No. 1. Same, with sixteen stars on the obverse. No. 2. Same, with thirteen stars on the obverse.

1798. No. 1. Same type as No. 3 dollar of 1798, with sixteen stars. No. 2. With thirteen stars on the obverse.

1799. None issued.

1800 to 1805, inclusive. Same as No. 3 of 1798.

1806. None issued.

1807. Same as No. 2 of 1798.

1808. None issued.

1809. Same type as No. 2 half-dollar of 1807; size, 12.

1810. None issued.

1811. Same as 1809.

1812 to 1813, inclusive. None issued.

1814. Same as 1809.

1815 to 1819, inclusive. None issued.

1820 to 1825, inclusive. Same as 1809.

1826. None issued.

1827 to 1836, inclusive. Same as 1809.

1837. No. 1. Same as 1809. No. 2. Obverse: Liberty seated. No stars.

Reverse: “��� ����” within a wreath of laurel. “������ ������ �� �������.” Size, 11.

1838. No. 1. Same as No. 2 of 1837. No. 2. Same, with thirteen stars.

1839 to 1852, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1838.

1853. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with an arrow head on each side of the date.

1854 and 1855. Same as No. 2 of 1853.

1856 to 1859, inclusive. Same, without arrow heads.

1860 to 1872, inclusive. Obverse: Same, with “������ ������ �� �������” instead of stars.

Reverse: “��� ����” within a wreath of corn, wheat, cotton, and tobacco.

1873. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with an arrow head on each side of the date.

1874. Same as No. 2 of 1873.

1875. Same, without arrow heads.

Half Dime.

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 20.8 grains; fineness, 892.4. Weight changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 20⅝ grains. Fineness changed, Act of January 18, 1837, to 900. Weight changed, Act of February 21, 1853, to 19.2 grains. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 12, 1873.

1794 and 1795. Same type as the half dollar; size, 10.

1796. Same type as No. 2 dollar of 1795; fifteen stars.

1797. No. 1. Same, with fifteen stars. No. 2. Same, with sixteen stars. No. 3. Same, with thirteen stars.

1798 and 1799. None issued.

1800 to 1803, inclusive. Same type as No. 3 dollar of 1798.

1804. None issued.

1805. Same as 1800.

1806 to 1828, inclusive. None issued.

1829 to 1873. See dime.

Three Cent Piece.

Authorized to be coined, Act of March 3, 1851. Weight, 12⅜ grains; fineness, 750. Weight changed, Act of March 3, 1853, to 11.52 grains. Fineness changed, Act of March 3, 1853, to 900. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 12, 1873.

1851 to 1853, inclusive. Obverse: A star bearing the United States shield. “������ ������ �� �������.”

Reverse: An ornamented “�,” within which is the denomination “���,” around the border, thirteen stars; size, 9.

1854 to 1858. Obverse: Same, with two lines around the star.

Reverse: An olive branch above the “���,” and three arrows below, all within the “�.”

1858 to 1873, inclusive. Same, with one line around the star.

M���� C����.

Five cent piece. (Nickle.)

Authorized to be coined, Act of May 16, 1866. Weight, 77.16 grains; composed of 75 per cent. copper, and 25 per cent. nickle.

1866. Obverse: A United States shield surmounted by a cross, an olive branch pendent at each side, back of the base of the shield are two arrows, the heads and feathers are only visible; beneath, “1866;” above, in the field, “�� ��� �� �����.”

Reverse: “5” within a circle of thirteen stars, and rays, “������ ������ �� �������.” Size, 13.

1867. Same. No. 2. Same, without the rays.

1868. Same as No. 2 of 1867.

1869 to 1882. Same as No. 2 of 1867.

1883. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Obverse: Liberty head wearing a coronet which is inscribed “�������,” thirteen stars, and date, “1883.”

Reverse: A “V” within a wreath of corn and cotton. Legend, “������ ������ �� �������.” Exergue, “� �������� ����.” No. 3, Obverse: Same as No. 2.

Reverse: Same, with “�����” as the exergue, and “� �������� ����” above the wreath.

1884. Same as No. 3 of the preceding.

Three cent piece. (Nickle.)

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 3, 1865. Weight, 30 grains; composed of 75 per cent. copper, and 25 per cent. nickle.

1865. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left, hair bound by a ribbon, on the forehead a coronet inscribed “�������;” beneath, the date, “������ ������ �� �������.”

Reverse: “���” within a laurel wreath.

Two Cent Piece (bronze).

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 22, 1864. Weight, 96 grains, composed of ninety-five per cent. copper and five per cent of tin and zinc. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 12, 1873.

1864 to 1873, inclusive. Obverse: The United States shield, behind which are two arrows, crossed, on each side a branch of laurel; above, a scroll inscribed “�� ��� �� �����”; beneath, the date.

Reverse: “2 �����” within a wreath of wheat. “������ ������ �� �������.” Size, 14.

Cent (copper).

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 22, 1792. Weight, 264 grains. Weight changed, Act of January 14, 1793, to 208 grains. Weight changed by proclamation of the President, January 26, 1796, in

conformity with an Act of March 3, 1795, to 168 grains. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 21, 1857.

1793. No. 1. Obverse: Liberty head, facing right, flowing hair Above, “�������”: beneath, “1793.”

Reverse: A chain of fifteen links, within which is inscribed “��� ����” and the fraction “⅟₁₀₀.” United States of America; reeded edge; size, 17.

No. 2. Same, with the abbreviation “�����.” in the Legend.

No. 3. Obverse: Same as No. 1, with a sprig beneath.

Reverse: “��� ����” within a wreath of laurel. “������ ������ �� �������.” Reeded edge.

No. 4. Obverse: A bust of Liberty, facing right, with pole and liberty cap. Above, “�������”; beneath, “1793.”

Reverse: Same as No. 3; on the edge, “��� ������� ��� � ������.” Size, 18.

1794 and 1795. Same as No. 4 of 1793.

1796. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with hair bound by a ribbon, and without pole and liberty cap on the obverse. Plain edge. 1797 to 1807 inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1796.

1808 to 1814, inclusive. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left, hair confined by a band, inscribed “�������.” Thirteen stars and date.

Reverse: “��� ����,” within a laurel wreath. “������ ������ �� �������.” The fraction “⅟₁₀₀” is omitted.

1815. None issued.

1816. Obverse: Liberty head, facing left, the hair is confined by a roll, and tied by a cord, while the forehead is bedecked with a tiara, inscribed “�������.”

Reverse: Same as 1808.

1817. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with fifteen stars. 1818 to 1836. Same as No. 1 of 1817.

1837. No. 1. Same. No. 2. Same, with the hair tied by a string of beads instead of a cord.

1838 to 1857, inclusive. Same as No. 2 of 1837.

Cent (Nickle).

Authorized to be coined, Act of February 21, 1857. Weight 72 grains; composed of 88 per cent. copper and 12 per cent. nickle. Coinage discontinued, Act of April 22, 1864.

1857 and 1858, Obverse: An eagle flying to the left. “������ ������ �� �������.”

Reverse: “��� ����,” within a wreath of corn, wheat, cotton, and tobacco. Size, 11.

1859. Obverse: An Indian-head, facing left, bedecked with eagle plumes, confined. “������ ������ �� �������.” Beneath, the date.

Reverse: “��� ����.” within a wreath of laurel.

1860 to 1864, inclusive. Obverse: Same.

Reverse: “��� ����,” within an oak wreath and shield.

Cent (Bronze).

Coinage authorized, Act of April 22, 1857. Weight, 48 grains; composed of 95 per cent. copper and 5 per cent. of tin and zinc.

1864. Same type as nickle cent of 1860. Size, 12.

Half Cent (Copper).

Authorized to be coined, Act of April 2, 1792. Weight, 132 grains. Weight changed, Act of January 14, 1793, to 104 grains. Weight changed by proclamation of the President, January 26, 1796, in conformity with Act of March 3, 1795, to 84 grains. Coinage discontinued, Act of February 21, 1857.

1793. Same type as cent No. 4, 1793, with head facing left. On the edge, “��� ������� ��� � ������.” Size, 14.

1794. Same type as the cent of 1794.

1795 to 1797, inclusive. Same, with plain edge.

1798 and 1799. None issued.

1800. Same type as No. 2 cent of 1796, with the fraction “⅟₂₀₀” on the base of the reverse.

1801. None issued.

1802 to 1808, inclusive. Same as 1800. From 1808, the fraction “⅟₂₀₀” omitted.

1809 to 1811, inclusive. Same type as cent of 1808.

1812 to 1824, inclusive. None issued.

1825 and 1826. Same type as cent of 1808.

1827. None issued.

1828. No. 1. Same type as cent 1808, with thirteen stars. No. 2. Same, with twelve stars.

1829. Same, with thirteen stars.

1830. None issued.

1831 to 1836, inclusive. Same type as cent of 1808. 1837 to 1839, inclusive. None issued.

1840 to 1857, inclusive. Same type as No. 2 cent of 1837; size, 14.

THOMAS JEFFERSON,

an eminent American Statesman, and third President of the United States, was born April 2, 1743, at Shadwell, Virginia, near the spot which afterwards became his residence, with the name of Monticello. He was the oldest son in a family of eight children. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a man of great force of character and of extraordinary physical strength. His mother, Jane Randolph, of Goochland, was descended from an English family of great note and respectability. Young Jefferson began his classical studies at the age of nine, and at seventeen he entered an advance class at William and Mary College; on his way thither, he formed the acquaintance of Patrick Henry, who was then a bankrupt merchant, but who afterwards became the great orator of the Revolution. At college, Jefferson was distinguished by his close application, and devoted, it is said, from twelve to fifteen hours per day to study, and we are told became well versed in Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and Spanish, at the same time proficient in his mathematical studies. After a few years course of law under Judge Wythe, he was admitted to the bar in 1767. His success in the legal profession was remarkable; his fees during the first year amounted to nearly three thousand dollars. In 1769, Jefferson commenced his public career as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, in which he had while a student of law, listened to Patrick Henry’s great speech on the Stamp Act. In 1773 he united with Patrick Henry and other revolutionary patriots in devising the celebrated committee of correspondence for disseminating intelligence between the Colonies, of which Jefferson was one of the most active and influential members. He was elected in 1774 to a convention to choose delegates to the first Continental Congress at Philadelphia, and introduced at that convention his famous “Summary view of the rights of British America.” On the 21st of June, 1775, Jefferson took his seat in the Continental Congress. His reputation as a Statesman and accomplished writer at once placed

him among the leaders of that renowned body He served on the most important committees, and among other papers drew up the reply of Congress to the proposal of Lord North, and assisted in preparing in behalf of the Colonies, a declaration of the cause of taking up arms against the Mother Country. The rejection of a final petition to King George, destroyed all hope of an honorable reconciliation with England. Congress, early in 1776, appointed a committee to draw up a Declaration of Independence, of which Jefferson was made Chairman; in this capacity he drafted, at the request of the other members of the committee, (Franklin, Adams, Sherman, and Livingston), and reported to Congress, June 28, the great Charter of Freedom, known as the “Declaration of American Independence,” which, on July 4, was unanimously adopted, and signed by every member present, with a single exception. “The Declaration of Independence,” says Edward Everett, “is equal to anything ever borne on parchment, or expressed in the visible signs of thought.” “The heart of Jefferson in writing it,” adds Bancroft, “and of Congress in adopting it, beat for all humanity.” After resigning his seat in Congress, Jefferson revised the laws of Virginia; among other reforms, he procured the repeal of the laws of entail, the abolition of primogeniture, and the restoration of the rights of conscience, a reform which he believed would abolish “every fibre of ancient or future aristocracy;” he also originated a complete system of elementary and collegiate education for Virginia. In 1779, Jefferson succeeded Patrick Henry as Governor of Virginia, and held the office during the most gloomy period of the Revolution, and declined a reelection in 1781. In 1783, he returned to Congress, and reported the treaty of peace, concluded at Paris, September 3, 1783, acknowledging the independence of the United States. He also proposed and carried through Congress a bill establishing the present Federal system of coinage, which took the place of the English pounds, shillings, pence, etc., and also introduced measures for establishing a Mint in Philadelphia, (the first public building built by the general Government, still standing on Seventh street, east side, near Filbert). In 1785, he succeeded Dr. Franklin as resident Minister at Paris. In organizing the Government after the adoption of the Constitution, he accepted the position of Secretary of State,

tendered him by President Washington during his first term. Jefferson was Vice-President of the United States from 1797 to 1801, and President for the two consecutive terms following. After participating in the inauguration of his friend and successor, James Madison, Jefferson returned to Monticello, where he passed the remainder of his life in directing the educational and industrial institutions of his native State and entertaining his many visitors and friends. His death occurred on the same day with that of John Adams, July 4, 1826.