Introduction

TheQueerandthePunk

“We’rehere,we’requeer,we’regoingtofuckyourchildren!”Thesebrazenwords,shoutedabovejanglyguitars andapropulsivedrumbeat,begin(andend)“QueerDiscoAnthem”(“QDA”),anirreverentdemandforqueer power recorded by underground punk outfit God Is My Co-Pilot (GodCo) on their 1996 album, The Best of God Is My Co-Pilot 1 Formed in New York City in 1991 by openly bisexual wife and husband duo Sharon Topper, vocals, and Craig Flanagin, guitar, GodCo make noisy, energetic avant-garde punk with lyrics that rowdilyevokequeerpleasures,politicsandpractices.Abandonamission,punkmusicwithqueermeaningis GodCo’s weapon of choice against the sexism and homophobia of rock and society, as they explain in “We Signify,”theirsignaturesongandmanifesto:“We’reco-optingrock,thelanguageofsexism,toaddressgender identity on its own terms of complexity.” In songs like the coy “Butch Flip,” which promises a reversal of butch-femme bedroom expectations, and the bisexual call to arms “Behave,” which exclaims “[I’ll] love who I love and fuck who I want,” GodCo conjure a raucous queer punkdom of unruly gender and sexual expression onthefringe.

This raucous queer punkdom is not the domain of GodCo alone, however The band is part of a wider queersubculture:aconfigurationofartisticallymindedgender/sexualdissidentswhoannexpunkpracticesand aesthetics to challenge the oppressions of the mainstream and the lifeless sexual politics and assimilationist tendencies of dominant gay and lesbian society This subculture is known as “homocore” or, more recently, “ queercore, ” to indicate an alliance with antiestablishment radical queer politics as opposed to a liberal gay politics of social integration. “Queercore” invokes a movement that is by and for not only homosexuals, but genderqueers, transgender folks and all those whose gender and/or sexual identities fall outside restrictive male/female, heterosexual/homosexual binaries Initially instigated by misfit Torontonians G B Jones and Bruce LaBruce via the pages of their ideologically seditious fanzine J.D.s (1985–1991), queercore has since evolved into an international phenomenon, partially centered on music, that also encompasses fanzines (commonly known as “zines”), film, writing, performance and visual art Increasingly dispersed and only loosely affiliated, queercore entities nevertheless share a common goal: to articulate and circulate a set of oppositional identities, mediated meanings and social practices for queers to occupy and engage within subculturalspace

This book traces the thematic and aesthetic contours of queercore, emphasizing its first two decades (roughly 1985–2006) and some of its most productive artists and artifacts: Bruce LaBruce (No Skin Off My Ass), G B Jones (The Lollipop Generation), God Is My Co-Pilot, Pansy Division, Huggy Bear, Johnny NoxzemaandRexBoy(Bimbox),GreggAraki(TheLivingEnd),Tribe8,MargaritaAlcantara(BambooGirl), VaginalDavis(PME),BethDitto(theGossip)andNomyLamm(SinsInvalid).Thisbookisnotintendedto bea“who’swho”ofqueercore,however,noranappraisalofwhichqueercoreworksmattermost Eschewinga nearsighted account, this book instead situates these queercore artists and artifacts as dynamic nodal points aroundwhichamultiplicityofqueerpunkpeoples,politicsandpracticesflickerintoview.

Likewise, more than just a tightly bounded subcultural history, this book builds on the scholarship of such thinkers as Tavia Nyong’o, Jack Halberstam and José Esteban Muñoz to situate queercore within a larger dialogue on the homology between queer theory/practice and punk theory/practice.2 In mobilizing this ongoing narrative of queer-punk intersectionality, of which queercore stands as exemplar, Queercore seeks to disrupt overdetermined associations between punk and straight men, and between homosexuality and pop culture from disco, to divas, to folk 3 Far from adversatives, queers (including those of color) were part of punkfromthestart,andqueernesshasleftasubversivestainonthesubculturethatcanstillbeobservedtoday. While not quite synonymous, queer and punk are energies with affective echoes and a potent magnetism. Wheneverandwherevertheycollide,fusesignite

Such is the case with GodCo’s “QDA,” which draws upon queer politics and punk aesthetics for its

incendiary effect. Written in 1994 amidst the betrayal of the Bill Clinton administration’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, barring the military service of openly LGBTQ+4 individuals, the song appropriates a slogan popularized by rabblerousing organization Queer Nation during the same historical time period: “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” Formed in March of 1990 as a grassroots response to a decade’s rise in antiqueerviolenceandthegovernment’scallous“look-the-other-way”responsetoHIV/AIDS,QueerNationwas known for in-your-face, theatrical activism, enacted via such public demonstrations as “kiss-ins” at shopping malls and straight bars, in which mass same sex lip-locking served as cheeky protest against the heterocentrism of communal space. In adopting Queer Nation’s slogan “We’re here, we ’ re queer ” enunciated in the same angry howl of the street protester, GodCo signify their radical allegiances, situating theirsonginthecompanyofabroaderpoliticalmovement

Punk is evident from the musical qualities of “QDA”: pounding drums, Flanagin’s raw, improvisational guitar playing and Topper’s feisty half-sung, half-shouted vocalizations There is also something quintessentiallypunkaboutGodCo’smodificationoftheQueerNationslogan,whichturnsafierychantinto something downright inflammatory with the add-on, “ we ’ re going to fuck your children.” As Flanagin contends in the liner notes to The Best of God Is My Co-Pilot, this added phrase implies that there is no distinction to be made between “ us ” queers and “ your ” children: “We are your children, and we ’ re going to fuck each other.” However, sung by a queer adult, it also raises the taboo of pedophilia, a taboo that is especiallystridentinrelationtoman-boysex:“Likecommunistsandhomosexualsinthe1950s,boy-loversare so stigmatized that it is difficult to find defenders for their civil liberties, let alone for their erotic orientation … the police have feasted on them” (Rubin, 1984: 272–3). GodCo thus take Queer Nation’s searing catchphrase to a more agitating extreme, augmenting it with the startling shock-effect common to punk: the deliberate deployment of the outrageous and offensive to incite a visceral response and, in the best of circumstances, to jar audiences out of complacency and into awareness and action 5 In other words, a punk twist of the profane intensifies the queer politics of “QDA,” carving its edges into a bold sexual provocation thatisqueerinpoliticsandpunkinsensibility Thatis,decidedlyanddefiantlyqueercore Ibeginwiththisbriefassessmentof“QDA”tobringthesubstanceofqueercoreintosharperfocus,butalso toindicatethepedagogicalpossibilitiesofqueercoreanalysis.Thisexampledemonstratesthat,asasubculture set in opposition to the power of heteronormativity and gay and lesbian orthodoxy, queercore offers a productive opportunity to revise and expand commonly held assumptions concerning non-straight existences and experiences. With its distinctive union of queer and punk, queercore stands to teach some valuable lessons: about alternative queer histories and identities, which have elsewhere been marginalized and remain largely unknown; about radical political and aesthetic strategies, and their attendant potentials and pitfalls; andaboutwhathappenswhenabstractqueertheoriesareputintotangibleactionsandartworks.Inthepages thatfollow,Iclarifythedefining,synergetictermsofthistext,“queer”and“punk,”beforearrivingatageneral overviewofqueercore’shistories,theories,methodsandephemeralarchives

NotGayasinHappy,ButQueerasin“FuckYou!”

In the fall of 2014, I produced a six-episode web series, directed by PJ Raval, for OUTsider an oddball, queercore-inspired transmedia festival and conference in Austin of which I am the Founder and Artistic Director. Hosted by Reverie (Paul Soileau) and Randee (Raval), a pair of over-the-top wackadoos patterned on the gaudy stylings of televangelists Tammy Faye and Jan Crouch, this series combined the circus-like atmosphere of the Jerry Lewis Telethon with the campy “edutainment” of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, concocting a dizzying introduction to the type of off-the-wall queer creation promised by the festival itself. Episode three, What’sitMeantobeQueer?,perhapsthebestintheseries,soughttoexplainwhatexactlywasmeantbyaqueer transmedia festival: something beyond gay and lesbian, and more than just a trendy appellation for sexual and genderminorities(seeFigure01) 6

Figure01 “AmIQueer?”fromOUTsiderTelethon(PJRaval,2015) FeaturingReverie(PaulSoileau) Screencapture

At the beginning of the episode, against a backdrop of garish green, pink and blue, Reverie and Randee bobble into frame, accompanied by the retro Italian disco of Raffaella Carrà Suddenly, Reverie surges into frenzied song, dressed in mink and polyester, a gold scarf wrapped around her bewigged head a whitesuited, mustachioed Randee gesticulating wildly behind her. “What’s it mean to be queer?,” she repeatedly queries, each time answering her own question with a series of curious, yet telltale, suppositions: “Do you eat your cake on a Monday morning? Do you pet your cat on a Tuesday night? Do you play with Barbies when you ’ re a boy? Do you like your momma more than your daddy? Do you wear heels on a Sunday?” Later, green-screened into a plush velvet living room adorned with religious iconography, I attempt to provide a still-inquisitiveReveriewithamoreprecisedefinitionofqueer:

Queerisasensibility,it’s anaesthetic. It’sawayof beingintheworldthatis differentthangayandlesbian. Both are attached to this idea of sexuality, but queer is all about rocking the boat It’s about pushing the norms It’s about expressing yourself however you see fit not worrying what people think It’s about being daring It’saboutbeingbold It’saboutpushingtheenvelope

This explanation is followed by a series of artistic interludes that loosely illustrate these very points, culminating in a conceptual display by performance artists Kimberly Pollini and Michael Anthony García of theChicanocuratorialcollectiveLosOutsiders Polliniwandersaboutanear-barrenstage,pullingcottonballs from her vagina, dropping them on the ground while emitting haphazard vocalizations to a soundtrack of tribalbeatsandbreakingglass.Garcíascampersandsummersaultsbehindher,retrievingthediscardedcotton balls, stuffing them in his mouth, one-by-one, until his cheeks are fully engorged, before unceremoniously disappearingfromsight

In turns weird, earnest and impenetrable, these various answers to the video’s titular question, “What’s it mean to be queer?,” are perhaps the best elucidations of this notoriously nebulous concept: neat, singular, unambiguous explanations do an injustice to “ queer ” a term that makes an intentional enemy of easy classifications and absolutes. Queer relishes outlaw mischief and prides itself on resisting boundaries and sedimentation. Efforts to firmly pin it down miss the whole point. As Annamarie Jagose reminds us in her oft-citedQueerTheory(1996:1),

queer is very much a category in the process of formation … It is not simply that queer has yet to solidify andtakeonamoreconsistentprofile,butratherthatitsdefinitionalindeterminacy,itselasticity,isoneofits constituentcharacteristics

Rather than resting in place, queer is constantly on the move, summoning “‘ a zone of possibilities’ … always inflected by a sense of potentiality that it cannot quite yet articulate” (Jagose, 1996: 2) Significantly, this restlessnessspringsfromanantagonisticrelationtofixed,codeterminingnotionsofgenderandsexuality,such that queer “describes those gestures and analytical modes which dramatize incoherence in the allegedly stable relationsbetweenchromosomalsex,genderandsexualdesire”(ibid:3)

Inotherwords,queerisever-shiftingandslipperybydesign Tomakemattersmorecomplicated,theintent behind specific iterations of queer depends on exactly which queer we are talking about. A term originally denoting the “unconventional” or “strange,” by the early twentieth century, queer came to be used as a

derogatory slur for male homosexuals “Queer!” was and in some quarters still is an insult calculated to sting the gay man with accusations of the unmanly and the effeminate That is, a rift between male body and masculine behavior is considered “strange” within the normative confines of biological determinism: the ideologically-inflectedinsistenceonadirectcorrelationbetweenbiologicalsexandgender,commandingmale bodiestoactmasculine,femalebodiestoactfeminine,ortosuffertheconsequences

Startinginthe1980s,however,radicalactiviststookituponthemselvestoreclaim“queer”fromthenarrowmindedbigots,refashioningthispithyputdownastheidealmonikerforanewconfrontationalstyleofpolitics one that flaunted its fierce rejection of all normative cultural pressures, from the subtle to the pervasive Breaking from earlier, more conciliatory gay and lesbian dispositions, and associated with such militant organizations as the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP), the Lesbian Avengers and the previously mentioned Queer Nation, the anarchistic force at the center of this brash new politics is perhaps best expressedbyoneofthemovement’smostmemorablecatchphrases:“Notgayasinhappy,butqueerasinfuck you!” Profoundly disturbed by a hostile heterosexual mainstream one that was quick to stigmatize the HIV positive and to physically assault gender/sexual minorities these activists hollered outrage at the genocide perpetuated by the government’s HIV/AIDS inaction, picketed at public schools whose homophobic curriculum impeded the development of self-affirming queer youths, protested hate crimes with rallying shouts of “Queers Bash Back!” and outed hypocritical politicians who supported anti-gay legislation by the light of day, while indulging in same sex frolics in the dark If the community had once relinquished its voice to appease the heterosexual majority, this would never be the case again, proclaimed the newly minted “ queers ” Aggression and backtalk were the name of the game, as was made clear via unapologetic manifestos likethepiercingbroadside“IHateStraights”byAnonymousQueers(2004),distributedatNewYork’sannual GayPrideparadeinJuneof1990:

They’vetaughtusthatgoodqueersdon’tgetmad They’vetaughtussowellthatwenotonlyhideouranger from them, we hide it from each other. WE EVEN HIDE IT FROM OURSELVES. We hide it with substance abuse and suicide and overachieving in the hope of proving our worth. They bash us and stab us andbombusineverincreasingnumbersandstillwefreakoutwhenangryqueerscarrybannersorsignsthat say BASH BACK For the last decade they let us die in droves and still we thank President Bush [George Bush,Sr.]forplantingafuckingtree,applaudhimforlikeningPWA’s[PeopleWithAIDS]tocaraccident victims who refuse to wear seatbelts. LET YOURSELF BE ANGRY. Let yourself be angry that the price of our visibility is the constant threat of violence, anti-queer violence, anti-queer violence to which practically every segment of this society contributes Let yourself feel angry that THERE IS NO PLACE IN THIS COUNTRY WHERE WE ARE SAFE, no place where we are not targeted for hatred and attack,theself-hatred,thesuicide ofthecloset.

Such demands for rage in the face of substance abuse, suicide, attack, HIV/AIDS genocide and more exemplify the volatile rhetoric and high political stakes from which the queer-as-radical-objector is derived Thisexplosivesociopoliticalmaelstromalsoconcurredwiththegenesisofqueercore.

At the same time as the radical queer activist was revolting in the streets, the burgeoning field of queer theory was taking shape in the academy The activist and academic versions of queer coincide insofar as both share a staunch aversion to the stifling effects of hetero- and homonormativity. Heteronormativity, a term popularized by Michael Warner in Fear of a Queer Planet (1993), being the widely propagated belief that heterosexuality is the only natural, normal state of human existence, thus privileging those who conform and condemning those who do not. Homonormativity, explicated by Lisa Duggan in Twilight of Equality (2003), refers to the infiltration of traditional gender and sexual norms into gay and lesbian society, establishing an intra-community hierarchy with upwardly mobile, coupled, monogamous, cisgender7 gay white men on top, and transgender, genderqueer and intersex folks on the bottom, along with queers of color, the nonmonogamous and various subcultural practitioners, such as sadomasochists. With a keen understanding of their destructive reach, the queer activist and the queer academician have made hetero- and homonormativity primarytargetsoftheirantiestablishmentcritiques

Yet,althoughthereisaconstructiveoverlapbetweentheradicalqueerofactivismandacademe,manyqueer organizers have, in fact, never read any queer theory texts, the opacity of which has led some critics to question the usefulness of queer theory in building actual material forms of resistance Queer theory owes much of its inspiration to the activists and artists who practice its application, but this has not always been

acknowledgedorappreciated:asqueercoreinstigatorG.B.Jonessaidtomeduringapersonalinterview,“We invented queer theory We lived it But, we ’ re not academics, so we don’t get credited with it, because we didn’t write the book about it.” Some, including scholar David Halperin (1996: n.p.), even suggest that the designation “ queer theory” is suspect, given its propensity to blunt: “Once conjoined with ‘theory’ … ‘ queer ’ losesitsoffensive,vilifyingtonalityandsubsidesintoaharmlessgenericqualifier”

Moreover, while the queer of activism and academia align via their forceful rejection of social norms, they start to break apart in respect to the question of identity politics: whereas identity occupies the requisite unifyingcoreofqueerpoliticalactivism theveryreasonforcollectiveaction anti-identitarianismformsthe basis of queer theory’s non-normative stance Building upon previous scholarship in feminism and gay and lesbian studies, queer theory appeared in the early 1990s as part of a post-modern/post-structuralist turn toward questioning universal, absolute truths: whilst the earlier field of gay and lesbian studies is oriented around a politics of identity that seeks to recover non-straight “subjects, texts, experiences and histories as legitimateobjectsofinquiryinahomophobicsociety,”queertheory“deniestheexistenceofanyfixedorstable notion of identities” in an effort to destabilize the powerful regimes built upon them (Carlin and DiGrazia, 2003: 2) Queer theory thus presents a persistent challenge to the reification of foundational, bifurcated identities like man/woman, heterosexual/homosexual, eroding the ground on which their supposed superiority/inferiorityresides

For example, in Gender Trouble, one of queer theory’s most well-known texts, Judith Butler argues that gender identity is neither natural, innate nor, ultimately, real. Rather, it is performed reiteratively through an array of “acts, gestures and desires” that imply an essential gendered self: these “acts and gestures, articulated and enacted desires create the illusion of an interior and organizing gender core ” (Butler, 1990: 136, my emphasis). But, there’s no stable basis from which gender emerges, no organizing self, no “there there.” For Butler there is just a semblance of the self, which is constructed through the repetitious and strenuous performance of gender In Gender Trouble, Butler pulls back the curtain on masculinity and femininity, male and female, sounding their death knell and revealing a lacuna of possibilities in their wake. The reparative impulse behind this highly deconstructive argumentation is the same for queer theory on the whole: by exposing the lie of gender (and biological sex), Butler seeks to expose the primal regulatory fictions that sustainheteronormativity’styrannicalauthority.

In principle, queer theory is capable of analyzing, and disassembling, all axes of identity and not just genderandsexuality AsDonaldE HallandAnnamarieJagose(2012:xvi)purport,

Queer studies’ commitment to non-normativity and anti-identitarianism, coupled with its refusal to define its proper field of operation in relation to any fixed content, means that, while prominently organized aroundsexuality,itispotentiallyattentivetoanysociallyconsequentialdifference

Thus, race, ethnicity, class, ability, generation and nationality are all potential sites of queer interrogation and deconstruction Even if young, white, able-bodied Americanness has frequently served as the unspoken default of queer theory so much so that scholars like Isling Mack-Nataf have stated that “When I hear the word queer, I think of white, gay men ” (qtd. in Smyth, 1992: 43). Yet, in spite of its exclusionary capacities, there exists a highly influential strand of queer scholarship, mostly penned by queer of color academics, that productivelyengagestheintersectionsofgender,sexualityandothermarkersofidentity Thisscholarshipwill playanactiveroleinthisbook,asaddressedinthe“QueercoreTheories”sectionofthischapter.

Finally, in addition to queer ’ s activist and academic use, in recent times, queer has also been deployed as an umbrella term for an ever-expanding range of gender and sexual minorities, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, genderqueer, intersex and pansexual Queer in this inclusive sense suggests a powerful coalition of the marginalized one from which a politics of queer community has been articulated. This is a fraught alliance, however, as these various identities often have little in common, same sex desire being the raison d’être of gay and lesbian life, and self-determination being the organizing principle of the gender variant Homonormative valuations that place interests of cisgender white gay men (e.g., the ability to transfer inheritance to partners via the legalization of gay marriage) above all others (eg, the ability of transfolk to accessneededpublicservices)furtherdiminishthestrengthofthisprecariousgrouping

As an umbrella term, “ queer ” functions most readily as a convenient label more than an indicator of inflammatory radicalism This watered-down use of “ queer ” has found expression in commercial culture,

starting in the early 2000s. Witness, for example, the popular television show Queer Eye for the Straight Guy (Bravo, 2003–07), a reality show about a team of gay men remaking a hapless straight male each week, teaching him the “virtues” of shopping, grooming and cultural connoisseurship. While this program had “ queer ” in its title, its investment in non-threatening images of success, beauty, wealth and, above all, consumer capitalism, arguably did little to upset hierarchies of sex, gender, sexuality, race and class, as the “ queer ”ofradicalactivismandtheorywouldhaveit

Against such co-optations of “ queer ” by the forces of capitalism and homonormativity, I use “ queer ” in this book as more than just a quick and simple shorthand I invoke the brazen anti-normative politics and positionalities of queer activism and academe Reluctant to allow “ queer ” to be fully subsumed by the mainstream, my analysis here seeks to restore queer ’ s radical signification. This reclamation feels especially importantatahistoricalmomentwhenthosewhostillbelieveinthegalvanizingthrustofqueermischiefmay need it most: a historical moment in which a newly legitimized gay and lesbian citizenry has been made safe and serviceable by state-sanctioned marriage and inclusion in the military. And, more recently, a historical momentinwhichracistandxenophobicfascismappearstohaveastrangleholdonAmericandemocracy,with anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment in sinister support 8 While queer is, at times, frustratingly abstruse, potentially alienating and has the potential to be exclusionary on the grounds of race and class, it best encapsulates the politics and practices pivotal to queercore and, thus, this book. Provocative, unflinching and motivated by a desire for social transformation, the radical incarnation of queer is the essence of queercore As the next section attests, the barbed exterior of queer outlined here melds seamlessly with the prickly edges of punk, bestowing upon the subculture its portmanteau: a combination of the “ queer ” of radical politics and theory andthe“core”ofhardcorepunk

NotPunkasinLoser,ButPunkasinTotallyPunkedUp

“I’mnotgoingtowriteaboutpunk,becausewheneveranybodytriesto,theycomeoffsoundingstupid…I’m notgoingtowriteaboutpunkbecausesometimestoexplainistoweaken,”scoffsqueercoreconspiratorBruce LaBruce in “The Wild, Wild World of Fanzines” (1995: 193), unintentionally conveying one of many affinitiesbetweenqueerandpunk.Thatis,likequeerness,themobile,proteannatureofpunkmakeseffortsto classify and calcify it dubious To experience punk is perhaps to know it best To describe it is a laden undertaking

The indeterminacy of punk is part and parcel of its generative versatility its arousal of multiple adjectives and imaginaries Punk is raw, indelicate, rude, outrageous and inciting It is also arty, affective, socially conscientious, anti-authoritarian, individualistic and profoundly participatory Punk is a mohawked Divine eating dog poop and vying for the title of “Filthiest Person Alive” in Pink Flamingos (Waters, 1972). It’s Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill teaching her young girl fans how to play guitar It’s the drawing of a fearless Asianwomanyankingtheheartfromaracistwhiteskinheadinthepagesofqueer,feministzineBambooGirl It’s workshops on interracial solidarity and gentrification at Smash It Dead festival in Boston, and handcraftingrecyclablematerialsatBayAreaLadyfest It’sL7singer,DonitaSparks,pullingabloodytampon from her body, and whipping it into the crowd, yelling “Eat my used tampon, fuckers!” It’s anarchist outfit Crass handing out pacifist literature in the mosh pit. It’s black, genderqueer artist Vaginal Davis caustically performing as a white supremacist in The White to Be Angry It’s self-titled “human pissoir” CHRISTEENE rimmingherhairy-assedbackupdancerscenterstage

Ifsuchcolorfulexamplesfailtosuffice,wemightturntosomecommondelineations:punkisasubculture a cultural assemblage whose adherents share specific marginal interests and practices, placing them on the outskirts of dominant culture The Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) a Birminghambased research center that included such renowned scholars as Stuart Hall, Dick Hebdige and Angela Robbie putSubculturalStudiesonthemapthroughtheanalysisofworking-classyouthformationslikemod,teddy andpunk Withinthesesubcultures,CCCSlocatedstrategiesofresistance,praisingthemforrepurposingthe detritus of consumer culture the discarded garbage bag refashioned as punk couture dress, for example thusenactingasenseofcollectivityandlodgingspectacularprotestagainstthebanalityofthemainstreamand the trappings of working-class life Building on their pioneering work, it can be said that subcultures (like punk) are out-of-the-ordinary, creatively industrious, troublemaking and locked in daring distinction to the innocuous majority. Subcultures are also more than a little queer: as Murray Healy (1996: 27) ruminates,

“There’s something queer about all subcultures just like dirty homosexuals, they’re dangerous, delinquent anddemonizedbythepress”

Punk as a subcultural phenomenon emerged in the mid-1970s, from the art school underground of New YorkandthegrittybackroombarsofLondon,asananti-virtuosicbacklashtotheoverblownperformanceand productionstylesofdiscoandprogressiverock “Punk”wasthenamechosenforthisrowdynewsubcultureof music, zines, film, performance and art due to its associations with the degraded and the debase including the queer. As John Robb explains, “punk” became the preferred label for this subculture in 1976 by way of a popular New York zine of the same name At this time, “punk” was a synonym for male prostitutes, passive homosexuals and young toughs, granting the term its special, subversive appeal: “The word ‘punk’ originally meantaprostitute,moldywoodorfungus.BythetimePunkmagazinetookitsname,ithadgoneontomean a person who takes it up the ass in prison, a loser or a form of Sixties garage rock’n’roll” (Robb, 2006: 150) Further reinforcing this etymological link between “punk” and sexual difference, Tavia Nyong’o (2008: 22–3) notesthat“punk”hasalonghistoryofusagewithinblackvernacularasavariantof“faggot”or“queer.”

In this manner, like the “ queer ” of queer activism/academe, which rescued an insult from the haters, symbolically stamping a new gender/sexual movement with its signature biting edge, a cadre of rebellious youths seized “punk” as the perfect encapsulation of their riotous enclave. While the queer connotations of “punk” were primarily intended to further the subculture’s affront to an uptight mainstream, this word choice reveals a slack, yet still ideologically charged, alliance between punk and queer from inception as elaborated inthechaptertocome.

“Punk” is more than just a name, however It carries with it a set of associated aesthetics and values Punk aesthetics emphasize the crude, the imperfect and the disorderly often produced via the reworking of everydayobjects.AsHebdigeclaimsinhisinfluentialtexton1970sworking-classpunkintheUK,Subculture: TheMeaningofStyle(1979),punk’sstylisticrebellionisconsistentlyderivedfromthepracticeofbricolage:the act of taking consumer goods and making them one ’ s own through revisions that instill new politicized meanings. According to Hebdige (1979: 107), by salvaging and repurposing the refuse of domestic workingclass life (the common safety pin, the grimy rubber stopper and chain from the bathroom sink, etc.), and combining these items with “vulgar designs” and “nasty colors,” the UK punks created a “revolting style” that projected “noise” and “chaos” and “offered self-conscious commentaries on the notions of modernity and taste.”Inthismanner,punkvisualsposeasymbolicthreattolawandorder,butonethatisalwaysindangerof incorporation, either through punk styles being transformed into mass-produced commodities (think Hot Topic)orthroughtheideologicalrecastingofpunkindividualsasharmlessandexoticbywayoftheir“strange looks”and“peculiarvisions.”Suchcommercialincorporationandideologicalrecastingproducestheinnocuous conditions necessary for such things as hackneyed Halloween costumes and uninspired avatars (think Guitar Hero)

The focus of Hebdige’s book is 1970s working-class UK punk, but the “revolting style” he outlines is discernibleacrossthepunklandscape,witheachpunkmediumrevealingitsownspecificaestheticattributesas well Punkmusic,forexample,ischaracterizedbydeliberateprimitivismandbasicmusicalstructures Typical punk rock instrumentation includes one or two electric guitars, an electric bass and a drum set, accompanied by vocals in which lyrics are shouted with minimal variety in terms of pitch, volume or intonation Guitar playingemphasizesdistortionandeschewscomplicatedarrangements Drumstendtobefast-pacedandoutof sync with the rhythms of the bass guitar, invoking a sense of disorder and rebelliousness, strengthened by the aggressive tempo and short duration of most punk songs Punk lyrics are often angry and confrontational, with topics ranging from nihilistic revolt (The Sex Pistol’s “Anarchy in the UK”), to feminist fury (X-Ray Spex’s “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!”), to workforce politics (the Clash’s “Career Opportunities”), to societal racism (BLXPLTN’s “Stop & Frisk”), to less common topics like romance (the Buzzcocks’ “Ever Fallen in Love?”) 9 Above all, punk music is rough and unpolished, conveying the “noise” and “chaos” described by Hebdigeandcontributingasensethatanyonecanplayit(Laing,1985:59–63)

Punk zines are usually handwritten and photocopied, with content including a combination of original and appropriated text and images The distinctive, haphazard visual style of punk zines is derived from such handmade production techniques as cut-and-paste letterforms, photocopied and collaged images and handscrawled and typewritten text. Zine texts often feature mistakes in grammar and spelling that are brazenly displayed or violently crossed-out and written over, demarcating a clear disregard for the dictates of

professional publication. This slapdash style underscores the urgency of the rants and reviews that comprise thebulkofzinecontent,recreatingtheloud,shambolicbuzzofpunkmusicinvisualform(Triggs,2006:69–73).

As observed by Hebdige, punk fashion revels in the vulgar and the nasty. Recognizable punk fashion elements include leather, denim, spikes, chains, combat boots, thrift shop clothes and the fetish gear associated with sadomasochism and pornography Brightly dyed hair, piercings, tattoos and “unconventional” hairstyles,suchasMohawksandspikedhair,arealsocommonplace.AccordingtoDaveLaing(1985:95),the “organizingprinciple”ofthe“punklook”isbindingandtearing,withrippedt-shirtsandtornjeanssignifying “poverty, the lack of concern for appearance or the involvement with violence of its wearer ” Such styles are off-puttingbydesignandserveaspunk’smostintrusiveelement punkfashion,asopposedtopunkmusicor zines,beingreadilyobservableoncitystreets(ibid:94–5)

Punk cinema adheres to the subculture’s aesthetic preoccupation with the disquieting and unconventional, and generally falls into one of two camps: (1) films like RunLolaRun (Tom Tykwer, 1999)and Requiemfora Dream (Darren Aronofsky, 2000) that feature fast-paced rapid-fire editing, jump cuts and non-linearity, signifyingpunkfragmentationanddisorder(Rombes,2005:2–3);and(2)filmslikeTheForeigner(AmosPoe, 1977) and Suburbia (Penelope Spheeris, 1984) that feature slow narrative pacing, little camera movement and infrequent edits, signifying a glib rejection of the standards of action and entertainment (Thompson, 2005: 23) These films, like Jon Moritsugu’s ModFuckExplosion (1994), also embrace the rough-edged amateurism of punk, with dark, grainy images, poorly framed shots, non-professional acting and an overall crude quality. Although seemingly opposite in approach, both of these cinematic camps defy conventional filmmaking practice,workingagainsteasyconsumption

Across these various media, punk’s “revolting style” serves to startle mainstream sensibilities. This “shock effect” is produced when audience members are confronted with unexpected material the abrasive sounds and arresting visuals of punk that disturb the discourses to which they have become accustomed According to philosopher Walter Benjamin (1968: 239), under the best conditions, the shock effect blocks traditional meaningsandforcesaudiencememberstoseetheworldanew,heraldingnewinsightandaction:althoughone reactiontoshock-effectisresistanceandrejection,thetraumatizedreceivertuningouttheoffendingmaterial, iftheshock-effectis“cushioned,parriedbyconsciousness,”itcanbeintegratedintothereceiver’sexperiences, leading to a heightened state of awareness. In this way, punk’s “revolting style” has an ambitious reach that stretches beyond just an empty gesture of rebellion In the best of circumstances, punk aims to be a wakeup calltoapublicotherwiseanesthetizedbythesuffocatingconformityofdailyexistence

Such a strategy of shock is not unique to punk alone, as punk aesthetics draw from earlier radical art movements, specifically Dada and Situationism, as explained by Greil Marcus in Lipstick Traces Dada emerged in France shortly after World War I as a creative protest against the cultural and intellectual conformity seen as root cause of the war. Believing that the mind-numbing “logics” of capitalism and colonialism, embedded in dominant art forms of the day, had led Europe and North America blindly into battle, the Dadaists advocated a turn away from logic in art toward a jarring, chaotic irrationality via such nonsensical and anti-art practices as: collage (scissor and glue “cut-ups”) and bricolage. The Situationist International, was a Paris-based art movement led by social revolutionaries in the 1950s and 1960s The primary target of the Situationists was advanced capitalism and the proliferation of social alienation and commodity fetishism into all aspects of life and culture. Essential to their critique was the concept of the “spectacle”: the expression and mediation of social relations through objects, and the deadening results As an antidote to the misery of the “spectacle,” the Situationists crafted “situations” moments of life designed to awaken alternative experiences and fulfill authentic desires, inciting adventure and liberating everyday life from its capitalist sedimentation One of the key Situationist practices was détournement which, like the bricolage of Dada and punk, appropriated and revised popular images, slogans, texts new contexts engendering new encounters. The pink triangle, used to mark internment camp prisoners as gay in Nazi Germany, turned into a resistant symbol of HIV/AIDS activism by ACT-UP in the 1980s, is an example of détournement

As this brief genealogical detour attests, punk aesthetics are never far afield from punk values. Punk values emphasize non-conformity and individual freedom, as well as opposition to authority, capitalism and mainstream success, with one of the biggest offenses in punk being to “sell out” to corporate interests By

deliberatelyfashioningproductsthataredifficultforthosewithamainstreamsensibilitytoconsume dueto, for example, their intentional incoherence or unsettling use of violence or sexual imagery punk limits its commercial viability. In this way, punk’s “revolting style” serves to undercut capitalist imperatives to make slick,profitableworkandtocompulsivelyconsumethesame.

In rejecting the dictates of capitalism/consumerism, punk affirms the principles of self-creation, participation and communal sharing, summed up by the defining punk ethic of DIY: Do-It-Yourself 10 D.I.Y.foregroundsthebenefitofindividualexpressionasanempoweringmeansoftakingculturalproduction outofthehandsofatechnocraticelite,transcendingtheinequitabledivisionbetweenactiveartistandpassive fan in the process DIY sends the message to one and all that, regardless of skill or resources, “You can do this too!” or, “Here’s a chord Here’s another and here’s a third Now go form a band!,” as classic punk zine Sideburnsmemorablyencourageditsreadersin1977.

Thisisaradicalmessage,accordingtoBenjamin,whoin“TheAuthorasProducer”(1999:298,emphasisin original) reasons that the important question to ask of radical culture is not “How does a literary work stand in relation to the relationships of production of a period,” but rather “How does it stand in them?” For Benjamin it is not the content of a work that matters most, but rather “the exemplary character of a production that enables it, first, to lead other producers to this production, and second to present them with an improved apparatus for their use. ” According to Benjamin, “this apparatus is better to the degree that it leads consumers to production, in short that it is capable of making co-workers out of readers or spectators” (ibid: 304) In other words, for Benjamin revolutionary art is that which does not just express radical ideas, butthatalsoactivatesitsreceivers,givingthemthetoolsandinspirationtobecome“co-workers.”

Punk does just this: the amateur rawness and simplicity of punk creates a low barrier for participation, paving a relatively smooth pathway from consumption to production Furthermore, many punk practices actively function to democratize relations between artists and audiences, blurring the distinction between the two Examplesincludepunkmusiciansperforminginthemoshpit,disregardingthesymbolichierarchyofthe stage, and punk guitarists teaching their audience members how to play, turning their fans into able cohorts Such D.I.Y. encouragement of grassroots production has been especially vital for women and minorities, who have regularly been denied voice in the mainstream marketplace: DIY is not just a creative practice but a sociopolitical lifeline for women, queers, people of color, and all those that dominant forces attempt to keep disenfranchised, unproductive and off-scene. In this regard, punk has always possessed an intrinsic potential tobeamediumforthequeermessage.

QueerasPunk:QueercoreHistories

The brief overview of queer and punk just provided suggests some of the ways in which the aggressive, unwieldyaestheticsofpunkmeshwiththejaggedexteriorsofqueer,justastheideologiesatthecoreofqueer and punk similarly coincide Both queer and punk seek to upend established structures, whether these structures be related to sex/gender (queer), commercial culture (punk) or, ultimately, both (queercore). Queer and punk also align via DIY practice For, as remarked by Mary Celeste Kearney in “The Missing Links,” DIY is not just an enduring ethos of punk, but of (lesbian-)feminism Which is to note that in the 1960s/70s, alongside punk, D.I.Y. took on renewed force via the lesbian-feminist folk movement of artists like Holly Near, Cris Williamson and pioneering feminist record label Olivia Records which relied on principles of self-determination to forge an unprecedented space for feminist music making outside of “the patriarchalandmisogynistmainstreammusicindustries”(Kearney,1997:219).DrawinguponKearney’spush toward non-androcentric historical accuracy, it is thus possible to reiterate with clarity that D.I.Y. is as queer, oratleastaslesbian-feminist,asitispunk 11

Sucharetheenmeshedgive-and-takelegaciesofqueerandpunk Queerisaggressive,antiestablishmentand bent on radical transformation. So is punk. Queer is stylish, loud, innovative and visually vexing. So is punk. Punk inspires queer, and queer arouses punk. This is an entanglement that was already twisted so tightly in the1970s,thatbythe1980sonemightsayqueercorewasasubculturejustwaitingtounfurl

Considering the vast number of artists, participants and locales that comprise the subculture of queercore, tracing its historical origins is a serpentine, if not futile, endeavor. It is also a task inevitably marked by my own positionality and interests as a queer white man in the US who has experienced but a particular slice of

queercore through acts of my own queer punk curation and artistic exploration in galleries, movie houses, music venues and online archives In GenderandthePoliticsofHistory, Joan Wallach Scott (1988: 7–8) asserts that “ one must acknowledge and take responsibility for the exclusions involved in one ’ s own project,” observing that a self-critical approach productively undermines problematic claims of authority based on “totalizingexplanations,essentializedcategoriesofanalysis orsystematicnarrativesthatassumeaninherent unity of the past” Similarly, in QueerFictionsofthePast, Scott Bravmann (1997: 125) advocates a move away from overdetermined causalities and shallow progress narratives of queer history, which only serve to repress instructive exceptions, inconsistencies and experiences, especially those related to queers of color and the working class Taking these ideas seriously, I acknowledge that the history of queercore presented here, by influenceofspaceandsubjectivity,omitsothervaluablenarratives,experiencesandversionsofevents.WhileI have made efforts in this book to include a diversity of perspectives and voices including those of the queers of color and working class to which Bravmann alludes I do not pretend to offer the definitive take on queercore ’ s development. I offer a provisional queercore history that I encourage readers to engage as one possiblenarrative asa “performativesitewheremeaningsarebeinginvented” ratherthanastheirrefutable, finalword(ibid:97)

With this caveat in mind, it is widely agreed that the subculture of queercore was launched by Toronto artporn provocateurs G B Jones and Bruce LaBruce through their 1980s zine JDs It was in the pages of JDs thattheword“homocore”wasarticulated,andtheconceptofthisradicalnewmultimediamovementofqueer punks,subsequentlyknownas“queercore,”waselucidated.TheoriginsofJ.D.scanbetracedtoJustDesserts, anall-nightrestaurantandlocalhangoutforpunks,junkies,sexworkersandartists,whereJonesandLaBruce initially met Forming a bond over their mutual distaste for mainstream culture, alienation from gay and lesbian society and appreciation of punk, they soon found themselves creative partners in a rundown, cockroach-infested apartment building at Queen and Parliament, an industrial neighborhood on the far outskirts of Toronto’s official gay neighborhood, Church and Wellesley 12 Estranged from their gay and lesbian peers, and living off shoplifted groceries from the local Loblaw’s (a grocery chain in Canada), Jones and LaBruce invented queercore in this soon-to-be-condemned apartment as a Situationist-style spectacle with the explicit goal of putting “the gay back in punk and the punk back in gay ” (Jones and LaBruce, 1989: 30)

Atthepointoftheirmeeting,Joneswasthedrummer,guitaristandbackgroundvocalistforgerminalqueerfeminist punk band Fifth Column, as well as a former art student at the Ontario College of Art (now the Ontario College of Art and Design), known for her détourned Archie comics: manipulated, cut-and-paste versions of the classic American comic that made it appear as if Jughead Jones, the lazy and girl-averse best friend of Archie Andrews, was gay.13 LaBruce was a graduate student in film studies at York University, working on his master’s thesis under the tutelage of gay film studies pioneer Robin Wood: a shot-by-shot analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) LaBruce was also a writer for film journal CineAction (cofoundedbyWood),andasometimesperformerinproto-queercorebandZuzu’sPetals.

AlthoughJonesandLaBrucewereart/filmstudents,theyhadbecomedisenchantedwiththeestablishedart worldandthehighereducationsystem WhereasJoneshadcometoseeartcriticismassophistryandpreferred alternative art spaces to sanctioned galleries, LaBruce was discovering that academia is a space riddled with hypocrisy:

I had a lot of professors at university which is one of the reasons I got disillusioned with academia who were extremely radical in their politics They were anti-materialist and anti-patriarchy They were against monogamy. They were against marriage. And, yet, they were married. They were monogamous. They lived in nice houses They had tenure I didn’t think that they had any intention of living what they were theoreticallyespousing

(PersonalInterview)

Jones’s and LaBruce’s dissatisfaction with orthodox forms of art and academia helped fuel their commitment to punk, which embodied the rebellious, antiestablishment spirit and radical, anti-capitalist politics that their professors theorized but did not practice By the time of their initial encounter at Just Desserts, the pair had already begun to drift away from school and further into the Toronto punk scene To their disappointment, however, this scene was dominated by macho, straight men who were overwhelmingly unwelcoming to

women and queers. A fact that became apparent during a performance by LaBruce’s band Zuzu’s Petals in Toronto:

There was this punk club in Kensington Market. It was called Quoc Te. It was a Vietnamese restaurant by dayandthenatnightitwasapunk venue There was a show there and Zuzu’s Petals played This guy with a huge Mohawk came up and punched me in the nose He punched me! I think I had a nose bleed And, Leslie [Mah] and some of the Fifth Column girls formed a human shield around me and were protecting me from these guys. We already knew that this [homophobia] existed, but it drove it home. (Personal Interview)

Jones and LaBruce viewed such displays of homophobia as a betrayal of punk’s legacy, detailed in Chapter 1, as a haven for misfits, minorities and deviants of all stripes, and set about creating a fanzine to bring punk back to its (queer) outsider roots one that targeted an imagined audience of “disillusioned kids who didn’t feel comfortable in the gay community, who turned to punk, but then when they got into punk, they found hostility there” (LaBruce, Personal Interview). They titled the zine J.D.s, which officially stood for “Juvenile Delinquents”butwasalsoanodtoJustDessertsand,initsintentionalambiguity,asignifierfor:popularpostpunk band Joy Division; favorite beverage of hard-drinking punks, Jack Daniels; and J D Salinger, whose blunt,outcast,youthfulwritingstylewasdeliberatelyimitatedinthepagesofJ.D.s.

Although JDs is generally considered the first queer punk fanzine, an important precursor was made by Jones’s and LaBruce’s compadre Candy Parker: Dr Smith (1984–1988) Titled after a flamboyant, gay-coded character played by Jonathan Harris on the 1960s television show LostinSpace, a man who had a suspiciously close relationship with pre-pubescent boy Will Robinson, Dr Smith is notable for cultivating a discernable queer punk aesthetic through an intentional “queering” (queer reimagining) of straight punk culture Long beforetheconceptof“queering”waspopularizedintheacademy,14 Dr Smithsetitsmischievousqueereyeon thebandsandculturaleventsoftheday,interspersinganti-sexistandanti-homophobiccritiqueswithreprints ofsexscandalsfromnewspapers,interviewswiththelikesofFifthColumnandhardcorepunkfavoritesBlack Flag, and grainy photos of rough and tumble punks slyly styled so as to re-envision them as cute and lovable teenidols.

Taking aesthetic and thematic cues from Dr Smith, Jones and LaBruce (with some help from Parker and others)publishedthefirstissueofJDsin1985 Referringtothemselvesandtheircomradesasthe“TheNew LavenderPanthers” “Lavender”beingatime-honoredeuphemismforhomosexuality15 and“Panthers”being an homage to militant Black Power collective, The Black Panthers Jones and LaBruce erected J.D.s as a (sub)cultural platform from which to stage their attack on the sexism and homophobia in punk, while also speaking against the creeping conservatism of an assimilationist gay and lesbian mainstream This twopronged assault against punk and gay/lesbian is perhaps most emphatically expressed in a 1989 manifesto published in MaximumRocknRoll (MRR) entitled “Don’t Be Gay or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Fuck Punk in the Ass” “Don’t Be Gay” was an invective lobbed against hardcore punk’s misogyny and heteronormativepresumption:

Let’s face it Going to most punk shows today is a lot like going to the average fag bar (MIGHTY SPHINCTER notwithstanding): all you see is big macho “dudes” in leather jackets and jeans parading around the dance floor/pit, manhandling each other’s sweaty bodies in proud display The only difference is that at the fag bar, females have been almost completely banished, while at the punk club, they’ve just been relegated to the periphery, but allowed a pretense of participation (ie girlfriend, groupie, go-fer, or postshow pussy). In this highly masculinized world, the focus is doubly male, the boys on stage controlling the “meaning” of the event (the style of music, political message, etc) and the boys in the pit determining the extentoftheexchangebetweenaudienceandperformer Andwheredoesthisleavetherest?

(JonesandLaBruce,1989:27)

“Don’t Be Gay” was also a critique of the gay and lesbian movement and the evils of sexism, gender segregationandmasculineprivilegethathadbecomeanincreasingpartofit:

Thegay“movement”asitexistsnowisabigfarce,andwehavenothingnicetosayaboutit,sowewon'tsay anythingatall,exceptthat,ironically,itfailsmostmiserablywhereitshouldbethemostprogressive inits sexual politics. Specifically there is a segregation of the sexes where unity should exist, a veiled misogyny which privileges fag culture over dyke, and a fear of the expression of femininity which has led to the

gruesomephenomenonofthe“straight-acting”gaymale.

(Ibid.:27)

These linked sentiments on the corrosive effects of mainstream punk and gay/lesbian two previously subversive cultures that had effectively sold their souls were at the irritated core of JDs’ critical cultural intervention: in a symbolic incarnation of the rebellious child, the oppositionality of queercore begins with an antagonisticrelationtothese“parentcultures”

Advocating the ideals of gender and sexual non-conformity within a punk milieu, in eight issues over a sixyear period, and with ample contributions from friends, Jones and LaBruce created this “softcore zine for hardcore kids,” which combined: original prose (early issues, for example, contain an ongoing story by LaBruce recounting, in confessional style, his sexual escapades with “Butch,” a sexy and laconic stud); photos (generally of friends, one of whom would be granted the title “Prince of the Homosexuals” each issue, or of straight punk performers, captured in various states of undress); artwork (most notably Jones’s drawings of eroticized, hyper-aggressive rebel women, done in a parodic Tom of Finland style); and appropriated images of punks, gay porn performers and Hollywood stars culled from other publications This was all executed in the seemingly haphazard cut-and-paste-and-then-photocopied style of early punk fanzines and added up to whatMarkFenster(1993:86)referstoasJDs’“confrontationalcamp/porn”aesthetic

But, more than just a zine, JDs aimed to be a multimedia experience From the start, JDs was known for its “J.D.s’ homocore Top 10” lists: lists of punk/post-punk songs that contained homoerotic content (e.g., “The Anal Staircase” by Coil and “They Only Loved at Night” by the Raincoats) A corresponding mixtape was also distributed that included twenty-one songs by bands that were mostly straight, but that nevertheless typified J.D.s’ irreverent approach to sexuality with lyrics like, “I wanna go where the boys have class. They suckeachother’scocksandtakeituptheass”fromMightySphincter’s“FagBar”In1990,JDsalsosolicited songs from readers, collected eleven, and released the first and intentionally mis-numbered queercore compilation,J.D.sTopTenHomocoreHitParadeTape. This cassette featured what would belatedly be known as the initial crop of queercore music groups: the Apostles, Academy 23 and No Brain Cells from the UK; FifthColumn,Zuzu’sPetalsandToiletSlavesfromCanada;Bomb,BigMan,RobtOmlitandNikkiParasite fromtheUS;andGorsefromNewZealand.

Alsoin1990,shortlyafterthereleaseofJDsTopTenHomocoreHitParadeTape, the editors of JDsbegan hosting film nights These nights consisted largely of films made by Jones and LaBruce themselves, like Unionville (Jones, 1985), an experimental meditation on the murder trial of a cult leader in Jones’s hometown andIKnowWhatIt’sLiketoBeDead (LaBruce, 1987), LaBruce’s melancholy response to AIDS in which he drags a zombified self through Toronto’s transit system and various urban landscapes 16 Through the dissemination of these artistic productions, Jones and LaBruce brought the concept of queercore into public view,sparkingarebelliousenthusiasmamonglike-mindedalienatedyouths.Theyalsoformedtheimpression ofafull-blownscene Eventhough,atfirst,queercorewasmoremyththanreality:asLaBrucemuses,initially queercore was a “WizardofOz style” illusion that, despite being comprised of only “two dykes and one lonely fag,” ended up fostering an underground buzz (Personal Interview) 17 Over time, however, this underground buzz became the cacophony of community, as Jones and LaBruce captured the collective imagination of their audience,callingintobeingtheveryqueerpunkscenethattheyhadsocunninglyenvisioned Soon, Jones and LaBruce were not alone In Toronto other queercore zines seared onto the scene, like JohnnyNoxzema’sandRexBoy’sinflammatoryBimbox(early1990s)andJenaVonBrücker’sfervidlyfeminist JaneGetsaDivorce (1993). Like Jones and LaBruce before them, these new queercore recruits were in search of compatible souls that were not to be found in the disappointingly lifeless gay and lesbian scene of 1980s Toronto.AsVonBrückerexplains:

I never felt that I fit into gay culture I remember going to the stupid bars and we would practically get into fights with everybody. Practically thrown out. In fact, thrown out of all kinds of places. Because everyone wassofuckinghumorless Theyweresohumorlessitwasridiculous They[myfriends]woulddecidethat they were going to do the jitterbug in the middle of the dance floor at The Rose [a popular lesbian bar in Toronto], and, oh my god, people would be outraged They’d be so upset They’d be complaining They’d be getting us thrown out … It was like there was no spirit or anything. They were just so boring. They just wantedtogointheirstupidjeans,andtheirstupidtuckedinshirtanddancetothesamestupidmusicevery

week.Andweweren’tlikethat,wewerealittlemorelively.So,wedidn’treallyfitin.(PersonalInterview)

Against this backdrop of depleted gay and lesbian existence, queercore was a space for the queer misfits and malcontentstoparticipateandbelong.Queercorezines,oftencollectivelymadeandexchangedfromhand-tohandforfreeorafewcoins,inparticular,operatedasDIY zonesofalternativequeercommunity-makingin Torontoand,eventually,elsewhere

Outside of Toronto, queercore scenes arose in cities like San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and Portland Homocore (1988–1991, San Francisco), an influential zine and “meeting place” for queer punks produced by Tom Jennings and Deke Nihilson,18 brought the subculture to the US West Coast Other rabblerousing zines took hold in their own locales, like FertileLaToyahJackson by Vaginal Davis (1982–1991, Los Angeles), Holy Titclamps by Larry-bob Roberts (1989–2003, Minneapolis and San Francisco), My Comrade/SisterbyLinda/LesSimpson(1987–2006,NewYork),RudeGirlbyEulalieFenster-GlasandAlison Wonderland (early 1990s, San Antonio), Slant/Slander and Evolution of a Race Riot by Mimi Thi Nguyen (1990s, Berkeley), i’m so fucking beautiful by Nomy Lamm (1990s, Olympia) and Bamboo Girl by Margarita Alcantara (1995–2005, New York) Handmade, photocopied, advertised by word-of-mouth and distributed through the mail, these zines relied on DIY practice to inform receptive parties of queercore ’ s arrival Fosteringanundergroundnetworkofdisenfranchisedqueerpunks,thesezinesalsocarvedoutacornerforthe queercore generation to tell their stories outside of, and in contradistinction to, the corrupt, homophobic, sexistandracistmassmarketplace

Several zines also functioned as independent music labels most notably Matt Wobensmith’s Outpunk (1992–1997)/Outpunk Records (1992–late 1990s) in San Francisco and Donna Dresch’s Chainsaw (later 1980s–1991)/Chainsaw Records in Olympia, Washington and Portland, Oregon.19 In 1992, Outpunk releasedThere’saFaggotinthePit and There’saDykeinthePit, two pathblazing 7” compilations that featured queer/queer-ally bands like Glee Club, Good Grief, Tribe 8, Bikini Kill and 7 Year Bitch. In 1995 the LP/CD Outpunk Dance Party introduced an eager and growing fan base to an impressive cross-section of queercorebands,includingPansyDivision,Sta-Prest,SisterGeorgeandMukilteoFairies TheOutpunklabel went on to produce and distribute albums by the likes of Cypher in the Snow, the Need, Behead the Prophet and the previously mentioned queercore mainstays Tribe 8, Pansy Division and God Is My Co-Pilot. Through these Outpunk releases, Wobensmith helped actualize the queercore music scene that Jones and LaBrucehadforeseen AsWobensmithproudlystated:

I respected the homocore movement immensely, but I had my own need to put my own stamp on it and to take it a step further from zines that are highly theoretical. To me embodying it in a record and bands that can play live and tour and speak, actually gave it a third dimension JDs is a zine of fantasy, really They tried to make it look like there was an army of people behind it They tried to make it look like it was a scene…YoucancreditJDsforhavingablueprintforascene,butIultimatelyfeltlikeweweremakingthe scenehappenforreal.(PersonalInterview)

Although Wobensmith withdrew from the music business in the early 2000s, he still plays an active role in sustaining queercore Currently, he runs a vintage zine store in San Francisco called Goteblüd that functions asanongoingarchiveforqueercoreandbeyond.

Donna Dresch, guitarist of queercore band Team Dresch, founded Chainsaw Records, in effect, when she distributedamusiccompilationcassetteinconjunctionwiththelastissueofherChainsaw zine in 1991 Over the subsequent years, Chainsaw Records released albums by feminist and queer punk bands like SleaterKinney, Frumpies, Third Sex, the Need, Kaia Wilson, the Fakes, Tracy and the Plastics and her own band Team Dresch before the label disappeared in the mid-2000s Queer-owned and operated, like Outpunk, Chainsawfashionedacommunity-centeredrefugeforqueersinthemusicindustry.Withpersonalinvestment inthemusicandthepoliticsbehindit,theselabelsactivelynurturedtheirqueerpunkartists,allowingthemto expressthemselveswithoutfearofcensorshiporpressuretoconformtoprefabricatedimaginaries something that was, and still is, uncommon in the predominately straight, and often homophobic, commercial music industry AsmusicologistJodieTaylorcontendsinachapteronqueercorefromthebookPlayingitQueer,the successofqueercoreispartiallypredicatedonitsoperationoutsideofthemajorrecordlabels:

This do-it-yourself approach affords queercore artists the freedom to speak directly to their audience about

issues that they feel are relevant to the lives and identities of queers. Furthermore, it is considered by some members of the queercore community to be the only way queers can maintain creative control over their product and avoid compromising their subject matter in order to broaden their appeal or appease heteronormativesensibilities (Taylor,2012:125)

Queercore bands like those mentioned above and others like Le Tigre, Black Fag, ¡Cholita!, PME, Limp Wrist, the Butchies, Extra Fancy, Excuse 17, Fagbash, Skinjobs, Gay for Johnny Depp, Gravy Train!!!!, Younger Lovers, the Shondes, the Gossip, Girl in a Coma, ASSACRE, She Devils and Kumbia Queers were/are far from compromising. Their remorselessly brash stylings and antagonistic queer politics expanded themisfitlegacyofpunkandusheredinaneweraofunapologetically“out”queermusicthathasenticednew fansintoqueercore’sfold

Queercore zines and bands helped develop the queercore subculture. However, it was not until 1991 that many of those involved artists and fans alike got a chance to finally meet in person. The first large-scale, face-to-face queercore gathering was the Spew convention, which cheekily promised “NO boring panels NO pointless workshops SHITLOADS of noisy dykes and fags” Held on May 25, 1991 in Chicago and organized by Steve LaFreniere, editor of The Gentlewomen of California (1987–1993, Chicago), Spew was a lively multimedia affair featuring: the editors of such zines as JDs, Bimbox, Homoture, Cunt, Sister Nobody, FistInYourFace,PissElegant, and Chainsaw; films and music videos by Jones, LaBruce, the Afro Sisters, the YeastieGirlz,GlenMeadmoreandothers;performancesbyVaginalDavis,FifthColumn,JoanJetBlakkand more; and a reading by controversial underground author Dennis Cooper (Spew poster, author unknown) Sadly,SpewwasalsothesiteofaviolenthomophobicattackagainstorganizerLaFreniere Asheexplains:

I was standing outside with Vaginal [Davis], right after she came offstage. Some guy drove by and yelled, “Faggots!” Having just seen one of the most momentous performances of my life by this incredible creature fromanotherworld,Iranupthestreet,and,whenthecargottothelight,Igotmyheadinthewindowand started screaming at the guy He got out of the car and stabbed me in the back The next thing I remember isbeingliftedintotheambulance.Hemissedanykindofinternalorgansthatwouldhavemeantmydemise. Theyneverdidcatchtheguy.

(qtd inRathe,2012:np)

InthemidstofSpew’sunwieldyandcelebratoryatmosphere,thishomophobicattackremindedparticipantsof just what they were fighting against Rather than completely muffling the festivities, the incident further bonded the now-acquainted community Which is to say that queercore had officially evolved from a wildeyedvisionofJonesandLaBrucetoaburgeoningsubcultureofzines,music,filmsandperformancesmadeby aconnected albeitgeographicallydispersed communitywho,literally,hadeachother’sbacks

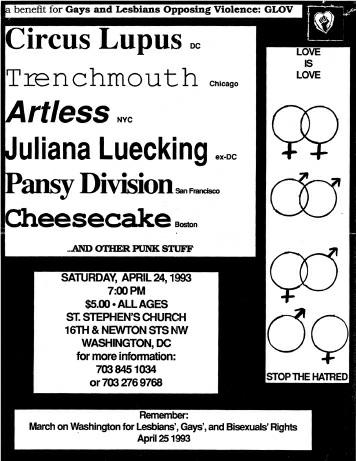

Spew was followed by several other similar events: Spew II, billed as “the carnivallike convention of queer misfits” took place in Los Angeles in 1992, and Spew III brought things back home to Toronto in 1993 (see Figure 02) In 1992, Mark Freitas and Joanna Brown began hosting “Homocore Chicago,” a monthly event in Chicago that featured queercore bands, offering a stable arena in the Midwest through which the scene could proliferate Homocore Minneapolis, QTIP (Queers Together in Punkness) and Klubstitute (both in San Francisco), Vazleen (Toronto), Scutterfest (Los Angeles), and the Bent Festival (Seattle) followed, building vital and vibrant platforms for queercore music, art and performance in their respective locales Queeruption, which started in London in 1998 and continued until 2010 in various cities across the globe (Berlin, Amsterdam, Sydney, Barcelona, Tel-Aviv, Vancouver, etc.), developed queercore kinship across national borders, and in the early 2000s, Homo-A-Go-Go, organized by Ed Varga, produced a bi-yearly multiarts festival in Olympia, Washington and, later, San Francisco Today, festivals in the queercore mold include FedUp Fest, a queer and transgender hardcore fest in Chicago, and my own OUTsider festival in Austin, Texas, which, in the transmedia vein of festivals like Spew and Homo-A-Go-Go, features a broad spectrumofmarginalqueerartinfilm,music,dance,theater,performanceandvisualart

Flyer for April 25, 1993 queercore

Washington,DC

Thevaluesthatwere/areondisplayatthesevariousqueercoreeventsareimportanttonote Inkeepingwith the subculture’s aversion to the mainstream, they were/are often held in community venues outside of the banal and commercialized “ gay ghetto.” Spew I, for example, took place at the Randolph Street Gallery, an alternative exhibition space in Chicago that specialized in showcasing artists who created work that was unsupported, or perceived to be unsupportable, by commercial or institutional funders. Spew II took place at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), a non-profit artist-run space based upon principles of grassrootscommunityorganizingandsocialchangeandcommittedtopresentingexperimentalworksofartin allmedia

Additionally, adhering to the principles of D.I.Y., and deeply invested in intersectional forms of queer politics, these gatherings often wore their radicalism on their torn sleeves Take, for example, this announcementfromthe2003QueeruptioninBerlin:

Queeruption is non-commercial! Queeruption is Do-it-Yourself! We draw no line between organisers and participants. We seek to provide a framework (space, co-ordination) which you can fill with your ideas. It willincludeworkshops,music,demonstrations,film,art,performances,(sex)parties,picnics,gamesandany other activities your feel like trying! What is queeruption? What is queer culture? For expression and exploration of identity. Climbing over the artificial boundaries of sexuality, gender, nation, class! Against racism,capitalism,patriarchyandbinarygenderrepression.

(qtd inPoldervaart,2004,np)

Such principled non-corporate D.I.Y. statements are commonplace within the literatures of queercore, which take the (political) manifesto and the (punk) rant as impassioned inspiration More than just meaningless statements, however, queercore events have done their best to bring their money (or lack thereof) to their proverbial mouths. For example, in a move of uncommon artist support, all of the money raised at the Homocore Chicago shows were paid directly to the bands Likewise, events like Homo-A-Go-Go deliberately kept their ticket prices low to allow for greater accessibility across lines of class and generation charging ten dollars for festival passes for youths and twenty dollars for day passes for those twenty-one and up

Significantly, queercore gatherings have generally been all-ages, indicating a concern for vulnerable queer youthswhohavefewothersafeplacestogo.Sometimesthisconcernhasevenexceededall-agesentrypolicies:

Figure02

show hosted by Gays and Lesbians Opposing Violence (Glov) Held at St Stephen’s Church in

forexample,eachyeartheprofitsofScutterfestwent towardascholarshipforanemergingqueeryouthartist, and Homocore Minneapolis, organized by Varga, hosted its shows at District 202, a queer youth center As Varga explains, this location not only allowed the scene ’ s youths to participate, but facilitated community control,providingamorefavorableexperiencethanfoundwithinthetypicalgayandlesbianbarscene:

The shows were all ages and it was important not to have them at a bar There were no bar options where you could have an 18 and up show, where you have wristbands for people who are over 21 So, none of the shows served alcohol and none of the shows were in a bar. And, yes, it was definitely a different environmentandthatwasonpurposeandimportanttome.There’salotofthingsthatmadeitdifferentand good IliketohavecompletecontrolwhenIdoanevent Whenyou’rerentingavenue,you’redependingon the bar to do security, they are making money on you from drinks or whatever I feel like in terms of being able to create an experience as opposed to just your average rock show at a club is to be able to control all those elements, of who runs the door and not having a surly bar staff but actually having people who are volunteers or friends running the box office and stuff like that So you are creating more of an experience thanjustanothernightatabar

(PersonalInterview)

This rejection of the bar scene was not only good for underage queer youths and the community-controlled natureofHomo-A-Go-Go,butalsobenefitedthoseinthesubculturewhoareaversetoalcohol,eitherdueto previous problems with addiction or personal preference. Given that the gay and lesbian community has been a major profit center for the alcohol industry, and has suffered from high rates of alcoholism,20 hosting an eventoutsideofthegaybarsisagesturepunctuatedwithmultiplelayersofsignificance:onethathailsyouths, thecommunity-driven,theanti-corporateandtherecoveringaddictalike

Despite socially conscious and inclusive policies like those just mentioned, however, it must be acknowledged that queercore was, at least initially, white-centered Queercore instigators Jones and LaBruce were both Caucasian and although JDs regularly expressed a politics of anti-racism, it also, as will be remarked in Chapter 2, played with skinhead iconography in a way that sometimes muddled the message, temperingitsradicalambitions Despiteitsblanchedbeginnings,queersofcoloreventuallymadeinroadsinto the subculture, leaving a (b)lasting impact 21 Aforementioned artists such as Vaginal Davis, Margarita AlcantaraandMimiThiNguyen,aswellasIrayaRoblesofSta-Prest,TaeWonYuofKickingGiant,Martin Sorrondeguy of Limp Wrist (formerly Los Crudos), and Tantrum and Leslie Mah of Tribe 8, singed new ideological passageways, adding needed anti-racist and anti-colonial perspectives to queercore ’ s political mix Similarly, transgender participants, like Lynnee Breedlove and Silas Howard of Tribe 8, and disabled folks like musician and zinester Nomy Lamm (i’m sofucking beautiful) and the Sins Invalid collective, have pushed against queercore ’ s omissions, forcing the subculture to expand beyond its white, cisgender, able-bodied bubble Exclusionscontinuetoexist,butminorityparticipantshavenotletthemgounchallenged Sexismisalsoanissuewithinqueercore,despitethefactthatwomenshapedthesubculturefromthestart 22 Also an issue within punk more broadly, sexism spurred a feminist punk movement in the 1990s that developedalongsidequeercore:riotgrrrl.23 ComingoutofOlympia,WashingtonandWashington,D.C.,riot grrrl was a global affiliation of young feminist women collectively producing zines (eg, Girl Germs and I Heart Amy Carter), performing in bands (eg, Bikini Kill and Bratmobile), holding activist meetings and addressing pertinent issues facing young women, such as sexual assault and eating disorders. Similar to queercore, riot grrrl was a reaction against the sexism of male-dominated punk It also functioned as a corrective to a second wave feminist movement that had long ignored the interests of girls and young women whetherbornoutoftoadesiretodistancethemselvesfromthepatriarchaltrivializationofwomenas“girls” oroutofpureageism

There is a great deal of overlap between queercore and riot grrrl, with many adherents, like Fifth Column and Team Dresch, identifying as both. But, there are also some distinctions to be made between queercore and riot grrrl Most obviously, while queerness is the central theme of queercore, feminism is the central theme of riot grrrl even if these topics are not confined to their respective subcultures Likewise, whereas riotgrrrlisafemale-identifiedsubculture,queercoreisdecidedlymulti-gendered.Indeed,creatingaspacenot limited to just gay men or lesbians like the traditional gay and lesbian bar scene was a central impetus behindqueercore AsTorontozinesterJenaVonBrückerexplains:

A women ’ s bar was a women ’ s bar, and a men ’ s bar was a men ’ s bar. And a guy couldn’t get into The Rose [alesbianbar]unless hewaswith women,andeventhenmaybenot. They’dsay,“no,”they’dturnyouaway atthedoor Itwasjustridiculous (Personalinterview)

VonBrückerclarifiestheunderlyingsexismandignoranceofthisgenderedsegregation:

It was like gay men hated women There was this undertone of hostility Not even an undertone, it was an overtone It was like, “Eww, what are they doing here?” It was just gross It’s almost like, sometimes you canfeelthehatebetweenheterosexuals.Youcanfeelthehatebetweenthemenandthewomen,exceptthat they need each other. They have to find some way to get along on some level, even though they don’t really want to It’s sort of like that, but they [gays and lesbians] don’t need each other for anything So, they were justcompletelypolarizedandtherewasalotofanimosity (PersonalInterview)

In this regard, while riot grrrl’s separatist tendencies were part and parcel of its radical efforts to foster safe spaces for women and girls beyond the reach of abusive patriarchy, the all-gender inclusivity of queercore was anactofdefianceagainstmaliciousformsofgendersegregationwithinthegayandlesbianmainstream.

Despitethepivotalcross-gendereffortsofqueercore,however,genderedantagonismshavenotbeenentirely absent within the subculture Indeed, Jones and LaBruce had a notorious falling out, apparently after LaBruce’s film No Skin Off My Ass (1991) became popular on the LGBTQ+ festival circuit: it has been suggestedthatJonesfeltthathercontributionstothefilm namelythewritingofherowndialogue hadnot been properly credited, and a cultural battle of sorts ensued between the two, with each taking barbed shots against the other in subsequent films and zines. The men in queercore have also benefited from greater attention from the press and art worlds on the whole All of this has made riot grrrl an even more necessary refuge not only from the sexism of punk and society at large, but from the male entitlement that has seeped intoqueercore 24

Such problems and contentious splits have not put an official end to queercore. Yet, there is a question of whether queercore continues to exist New queer punk bands like GLOSS, FEA, bottoms, Against Me! and Hunx & His Punx are alive and well, as are contemporary queercore artworks like the recent film Desire WillSetYouFree(YonyLeyser,2015).But,thesubcultureismoredispersedthanever,itsbordersharderthan ever to trace, with “ queercore ” now being used as a general descriptor for gay music in iTunes blurbs and online forums without much understanding of the term’s history or import With fewer and fewer events to bringthecommunitytogetherasanykindofunifiedconglomerate,queercoremaybeathingofthepast.

But, if there is indeed a period to be put on the end of queercore, perhaps the honor goes to co-founder LaBruce, whose 2008 zombie film, Otto; Or Up with Dead People can be read as a symbolic funeral for the queer punk. Produced within a climate of uncertain queer punk possibilities, Otto presents the “authentic” queer punk as a figure who, while not quite dead, is, literally, a zombie. Otto, our zombie hero, aimlessly wanders the streets of Berlin, auditions for a film, and finds himself the subject of a documentary by Medea Yarns (an anagram for renowned avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren) who is shooting a film about a gay zombie revolt against consumerist society. Otto attempts to connect with the actors in Medea’s zombie film and the other “fake zombies” that populate Berlin in Otto, in a sly nod to (queer) punk appropriation, the zombie is a fashion adopted by conformist homosexuals as a kind of S/M club wear But, these faux zombies are all style and no substance, leaving Otto continually alienated and alone, as Medea observes, “conducting his own one-man revolution against reality” Otto’s zombie authenticity his irreconcilable difference, within a hetero- and homonormative world sets him apart from straights and fake zombies alike, and his efforts to integrate and connect are fruitless. The film thus ends as it also begins, with Otto lumbering alone down a roadindesperatesearchof“moreofmykindupNorth.”25

QueercoreTheories

As indicated earlier, queercore appeared at the historical moment when “ queer ” was undergoing its radical reclamationviaactivismandacademia G B Jonesallegedthatalthoughqueercoreisresponsibleforthelived realities behind the lofty ideas in the ever-multiplying library of queer thought, queercore ’ s adherents “didn’t writethebookaboutit”and,therefore,“don’tgetcreditedwithit.”Whetherornotthisistrue,queercorehas functioned as a brilliant prism through which queer theories have circulated and refracted: a space where

abstract ideas have taken edifying material form and where queer scholars have turned to proffer their proof. Assuch,theliteratureonqueercorechartstheongoingtrajectoryofqueertheory Inthe1990s,queertheory’s emphasis on gender/sexual subversion found expression in an initial crop of academic essays on queercore. More recently, queer theory’s turn toward the anti-social has placed queer punk at the center of additional analyses Scholarly efforts to expand queer theory beyond its tacit whiteness have also aligned instructively withqueercore’seffortstodothesame