Principles of Economics : A Streamlined Approach Kate Antonovics

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-economics-a-streamlined-approach-kate -antonovics/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Principles of Chemistry A Molecular Approach Nivaldo J. Tro

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-chemistry-amolecular-approach-nivaldo-j-tro/

Principles of Economics 8th Edition N Gregory Mankiw

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-economics-8thedition-n-gregory-mankiw/

Principles of Economics 7th Edition N. Gregory Mankiw

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-economics-7thedition-n-gregory-mankiw/

Principles of Economics, 10th Edition (The Pearson Series in Economics) Karl E. Case

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-economics-10thedition-the-pearson-series-in-economics-karl-e-case/

A Guide To The Systems Of Provision Approach: Who Gets What, How And Why Kate Bayliss

https://textbookfull.com/product/a-guide-to-the-systems-ofprovision-approach-who-gets-what-how-and-why-kate-bayliss/

Real Estate Principles : A Value Approach David Ryan

https://textbookfull.com/product/real-estate-principles-a-valueapproach-david-ryan/

Managerial Economics: A Problem Solving Approach, 5e Brian T. Mccann

https://textbookfull.com/product/managerial-economics-a-problemsolving-approach-5e-brian-t-mccann/

Economics principles, applications, and tools Arthur O’Sullivan

https://textbookfull.com/product/economics-principlesapplications-and-tools-arthur-osullivan/

Principles of Digital Communication A Top Down Approach 1st Edition Bixio Rimoldi

https://textbookfull.com/product/principles-of-digitalcommunication-a-top-down-approach-1st-edition-bixio-rimoldi/

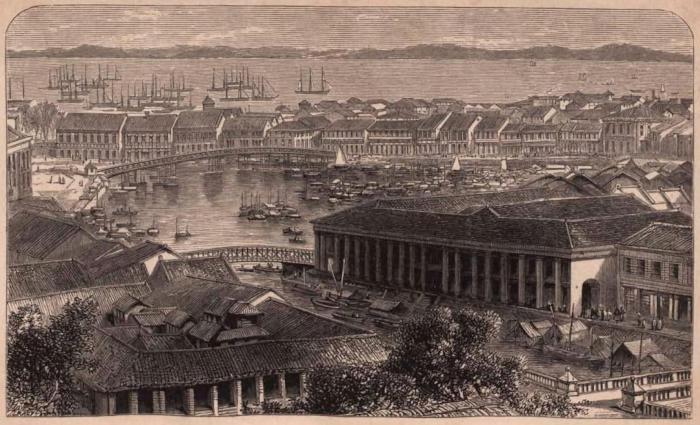

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

generous manner in which the Dutch officials treat those who come to them properly recommended by the higher authorities.

After crossing the Barizan chain, and coming down into this valley of the Musi, I have noticed that the natives are of a lighter color, taller, and more gracefully formed than those seen in the vicinity of Bencoolen. The men always carry a kris or a lance when they go from one kampong to another. The same laws and customs prevail here as in the vicinity of Bencoolen, except that the jugur, or price of a bride, is considerably higher. The anak gadis here also wear many rings of large silver wire on the forearm, and gold beads on the wrist, in token of their virginity. The Resident states to me that the native population does not appear to increase in this region, and that the high price of the brides is the chief reason. As the price is paid to the girl’s parents, and not to herself, she has less inducement to conduct herself in accordance with their wishes; and, to avoid the natural consequences of their habits, the anak gadis are accustomed to take very large doses of pepper, which is mixed with salt, in order to be swallowed more easily. Many are never married, and most of those who are, bear but two or three children, after they have subjected themselves to such severe treatment in their youth.

April 27th.—Rode five or six paals up the Musi, and then crossed it at the foot of a rapid on a “racket,” or raft of bamboo, the usual mode of ferrying in this island. In the centre of the raft is a kind of platform, where the passenger sits. One native stands at the bow, and one at the stern, each having a long bamboo. The racket is then drawn up close to the foot of the rapids, and a man keeps her head to the stream, while the other pushes her over. As soon as she leaves the bank, away she shoots down the current, despite the shouts and exertions of both. We were carried down so swiftly, that I began to fear we should come into another rapid, where our frail raft would have been washed to pieces among the foaming rocks in a moment; but at last they succeeded in stopping her, and we gained the opposite bank. Thence my guide took me through a morass, which was covered with a dense jungle, an admirable place for crocodiles, and they do not fail to frequent it in large numbers; but the thousands of leeches formed a worse pest. In one place, about a foot square, in

the path, I think I saw as many as twenty, all stretching and twisting themselves in every direction in search of prey. They are small, being about an inch long, and a tenth of an inch in diameter, before they gorge themselves with the blood of some unfortunate animal that chances to pass. They tormented me in a most shocking manner. Every ten or fifteen minutes I had to stop and rid myself of perfect anklets of them.

I was in search of a coral-stone, which the natives of this region burn for lime. My attendants, as well as myself, were so tormented with the leeches, that we could not remain long in that region, but I saw it was nothing but a raised reef, chiefly composed of comminuted coral, in which were many large hemispherical meandrinas. The strata, where they could be distinguished, were seen to be nearly horizontal. Large blocks of coral are scattered about, just as on the present reefs, but the jungle was too thick to travel in far, and, as soon as we had gathered a few shells, we hurried to the Musi, and rode back seven miles in a heavy, drenching rain.

All the region we have been travelling in to-day abounds in rhinoceroses, elephants, and deer. If the leeches attack them as they did a dog that followed us, they must prove one of the most efficient means of destroying those large animals. It is at least fortunate for the elephant and rhinoceros that they are pachyderms. While passing through the places where the jungle is mostly composed of bamboos, we saw several large troops of small, slate-colored monkeys, and, among the taller trees, troops of another species of a light-yellow color, with long arms and long tails. On the morning that I left Tanjong Agong, as we passed a tall tree by the roadside, the natives cautioned me to keep quiet, for it was “full of monkeys,” and, when we were just under it, they all set up a loud shout, and at once a whole troop sprang out of its high branches like a flock of birds. Some came down twenty-five or thirty feet before they struck on the tops of the small trees beneath them, and yet each would recover, and go off through the jungle, with the speed of an arrow, in a moment.

While nearly all animals have a particular area which they frequent —as the low coast region, the plateaus of these tropical lands, or the higher parts of the mountains—the rhinoceros lives indifferently anywhere between the sea-shores and the tops of the highest peaks. This species has two “horns,” the first being the longer and more sharply pointed, but the Java species has only one. The natives here know nothing of the frequent combats between these animals and elephants, that are so frequently pictured in popular works on natural history. The Resident has, however, told me of a combat between two other rivals of these forests that is more remarkable. When he was controleur at a small post, a short distance north of this place, a native came to him one morning, and asked, if he should find a dead tiger and bring its head, whether he would receive the usual bounty given by the government. The Resident assured him that he would, and the native then explained that there had evidently been a battle between two tigers in the woods, near his kampong, for all had heard their howls and cries, and they were fighting so long that, he had no doubt, one was left dead on the spot. A party at once began a hunt for the expected prize, and soon they found the battle had not been between two tigers, as they had supposed, but between a tiger and a bear, and that both were dead. The bear was still hugging the tiger, and the tiger had reached round, and fastened his teeth in the side of the bear’s neck. The natives then gathered some rattan, wound it round them, just as they were, strung them to a long bamboo, and brought them to the office of the Resident, who gave a full account of this strange combat in his next official report.

These bears are popularly called “sun” bears, Helarctos Malayanus, from their habit of basking in the hot sunshine, while other bears slink away from the full light of day into some shady place. The Resident at Bencoolen had a young cub that was very tame. Its fur was short, fine, and glossy. It was entirely black, except a crescent-shaped spot of white on its breast, which characterizes the species.

Governor Raffles, while at Bencoolen, also had a tame one, which was very fond of mangostins, and only lost its good-nature when it

came to the table, and was not treated with champagne. When fully grown, it is only four and a half feet long. It is herbivorous, and particularly fond of the young leaves of the cocoa-nut palm, and is said to destroy many of those valuable trees to gratify its appetite.

April 30th.—At 6 �. �. commenced the last stage of my journey on horseback. My course now was from Tebing Tingi, on the Musi, in a southeasterly direction, to Lahat, the head of navigation on the Limatang. The distance between these two places is about forty paals, considerably farther than it would be from Tebing Tingi down the Musi to the head of navigation on that river; but I prefer to take this route, in order to learn something of the localities of coal on the Limatang and its branches, and of the unexplored Pasuma country. We crossed the Musi on a raft, and at once the road took us into a forest, which continued with little interruption all the way to Bunga Mas, a distance of twenty-four paals. Most of this forest rises out of a dense undergrowth, in which the creeping stems and prickly leaves of rattans were seen. These are various species of Calamus, a genus of palms that has small, reed-like, trailing stems, which are in strange contrast to the erect and rigid trunks of the cocoa-nut, the areca, the palmetto, and other palms. It seems paradoxical to call this a palm, and the high, rigid bamboo a species of grass. When they are growing, the stem is sheathed in the bases of so many leaves that it is half an inch in diameter. When these are stripped off, a smooth, reed-like stem of a straw-color is found within, which becomes yellow as it dries. The first half-mile of the road we travelled to-day was completely ploughed up by elephants which passed along two days ago during a heavy rain. The piles of their excrements were so numerous that it seems they use it as a stall. Every few moments we came upon their tracks. In one place they had completely brushed away the bridge over a small stream, where they went down to ford it; for, though they always try to avail themselves of the cleared road when they travel to and fro among these forests, they are too sagacious to trust themselves on the frail bridges.

In the afternoon, the small boughs which they had lately broken off became more numerous as we advanced, and their leaves were of a

livelier green. We were evidently near a herd, for leaves wilt in a short time under this tropical sun. Soon after, we came into a thicker part of the forest, where many tall trees threw out high, overarching branches, which effectually shielded us from the scorching sun, while the dry leaves they had shed quite covered the road.

Several natives had joined us, for they always travel in company through fear of the tigers. While we were passing through the dark wood, suddenly a heavy crashing began in the thick jungle about twenty paces from where I was riding. A native, who was walking beside my horse with my rifle capped and cocked, handed it to me in an instant, but the jungle was so thick that it was impossible to see any thing, and I did not propose to fire until I could see the forehead of my game. All set up a loud, prolonged yell, and the beast slowly retreated, and allowed us to proceed unmolested. The natives are not afraid of whole herds of elephants, but they dislike to come near a single one. The larger and stronger males sometimes drive off all their weaker rivals, which are apt to wreak their vengeance on any one they chance to meet. Beyond this was a more open country, and in the road were scattered many small trees that had been torn up by a herd, apparently this very morning.

Although they are so abundant here in Sumatra, there are none found in Java. They occur in large numbers on the Malay Peninsula, and there is good reason to suppose they exist in the wild state in the northern parts of Borneo. This is regarded as distinct from the Asiatic and African species, and has been named Elephas Sumatrensis.

Three paals before we came to Bunga Mas, a heavy rain set in and continued until we reached that place. Our road crossed a number of streams that had their sources on the flanks of the mountains on our right, and in a short time their torrents were so swollen that my horse could scarcely ford them. Bunga Mas is a dusun, or village, on a cliff by a small river which flows toward the north. Near the village is a stockade fort, where we arrived at halfpast six. The captain gave me comfortable quarters, and I was truly thankful to escape the storm and the tigers without, and to rest after more than twelve hours in the saddle.

This evening the captain has shown me the skin of a large tiger, which, a short time since, killed three natives in four nights at this place. The village is surrounded by a stockade to keep out these ravenous beasts, and the gate is guarded at night by a native armed with a musket. One evening this tiger stole up behind the guard, sprang upon him, and, as a native said who chanced to see it, killed him instantly with a blow of her paw on the back of his neck. She then caught him up and ran away with him. The next day the body was found partly eaten, and was buried very deeply to keep it out of her reach. The second evening she seized and carried off a native who was bathing in the stream at the foot of the cliff. The captain now found he must try to destroy her, and therefore loaded a musket with a very heavy charge of powder and two bullets. The gun was then lashed firmly to a tree, and a large piece of fresh meat was fastened to the muzzle, so that when she attempted to take it away she would discharge the piece, and receive both bullets. The next morning they found a piece of her tongue on the ground near the muzzle of the gun, and the same trap was set again; but the next night she came back and took away a second man on guard at the gate of the dusun. The captain now started with a corporal and eight men, determined to hunt her down. They tracked her to a place filled with tall grass, and closing round that, slowly advanced, until two or three of them heard a growl, when they all fired and killed her instantly. It proved to be a female, and she had evidently been so daring for the purpose of procuring food for her young.

May 1st.—The rain continued through the night, and only cleared away at daylight. In two hours I started, though I found myself ill from such continued exertion and exposure to a burning sun and drenching rains, and, more than all, from drinking so many different kinds of water in a single day. I was accompanied by a soldier who was one of the eight who went out to hunt the tiger that killed so many natives in such a short time. He repeated to me all the details of the whole matter, and assured me that a piece of the brute’s tongue was found on the ground just as the captain said, and that, when they had secured her, they found that a part of her tongue was gone.

We had not travelled more than half a mile before we came upon the tracks of two tigers, a large one and a small one, probably a female and her young, which had passed along the road in the same way we were going. The perfect impressions left by their feet showed they had walked along that road since the rain had ceased, and therefore not more than two hours before us, and possibly not more than ten minutes. We expected to see them at almost every turn in the road, and we all kept together and proceeded with the greatest caution till the sun was high and it was again scorching hot. At such times these dangerous beasts always retreat into the cool jungle.

For eight paals from Bunga Mas the road was more hilly than it was yesterday. In many places the sides of the little valley between the ridges were so steep that steps were made in the slippery clay for the natives, who always travel on foot. Seven paals out, we had a fine view of the Pasuma country. It is a plateau which spreads out to the southeast and east from the feet of the great Dempo, the highest and most magnificent mountain in all this region. The lower part of this volcano appeared in all its details, but thick clouds unfortunately concealed its summit. Considerable quantities of opaque gases are said to have poured out of its crater, but it does not appear to have undergone any great eruption since the Dutch established themselves in this region. It is the most southern and eastern of the many active volcanoes on this island. Like the Mérapi in the Padang plateau, the Dempo does not rise in the Barizan chain nor in one parallel to it, but in a transverse range. Here there is no high chain parallel to the Barizan, as there is at Kopaiyong, where the Musi takes its rise, and also north of Mount Ulu Musi continuously through the Korinchi country all the way to the Batta Lands. Another and a longer transverse elevation appears in the chain which forms the boundary between this residency of Palembang and that of Lampong, and which is the water-shed, extending in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ranau to the Java Sea. The height of Mount Dempo has been variously estimated at from ten thousand to twelve thousand feet, but I judge that it is not higher than the Mérapi, and that its summit therefore is not more than nine thousand five hundred feet above the level of the sea.

The Pasuma plateau is undoubtedly the most densely-peopled area in this part of the island. Its soil is described to me, by those who have seen it, as exceedingly fertile, and quite like that of the Musi valley at Kopaiyong, but the natives of that country were extremely poor, while the Pasumas raise an abundance of rice and keep many fowls. During the past few years they have raised potatoes and many sorts of European vegetables, which they sold to the Dutch before the war began. The cause of the present difficulty was a demand made by the Dutch Government that the Pasuma chiefs should acknowledge its supremacy, which they have all refused to do. The villages or fortified places of the Pasumas are located on the tops of hills, and they fight with so much determination that they have already repulsed the Dutch once from one of their forts with a very considerable loss. No one, however, entertains a doubt of the final result of this campaign, for their fortifications are poor defences against the mortars and other ordnance of the Dutch.

Soon after the tracks of the two tigers disappeared, we came to a kind of rude stockade fort, where a guard of native militia are stationed. The paling, however, is more for a protection against the tigers than the neighboring Pasumas. A number of the guard told me that they hear the tigers howl here every night, and that frequently they come up on the hill and walk round the paling, looking for a chance to enter; and I have no doubt their assertions were entirely true, for when we had come to the foot of the hill the whole road was covered with tracks. The natives, who, from long experience, have remarkable skill in tracing these beasts, said that three different ones had been there since the rain ceased; but one who has not been accustomed to examine such tracks would have judged that half a dozen tigers had passed that way. There are but a few native houses here at a distance from the villages in the ladangs, and those are all perched on posts twelve or fifteen feet high, and reached by a ladder or notched stick, in order that those dwelling in them may be safer from the tigers.

At noon we came down into a fertile valley surrounded with mountains in the distance, and at 2 �. �. arrived at Lahat, a pretty

native village on the banks of the Limatang. The controleur stationed here received me politely, and engaged a boat to take me down the Limatang to Palembang. The Limatang takes its rise up in the Pasuma country, and Lahat, being at the head of navigation on this river, is an important point. A strong fort has been built here, and is constantly garrisoned with one or two companies of soldiers. One night while I was there, there was a general alarm that a strong body of Pasumas had been discovered reconnoitring the village, and immediately every possible preparation was made to receive them. The cause of the alarm proved to be, that one of the Javanese soldiers stationed outside the fort stated that he saw two natives skulking in the shrubbery near him, and that he heard them consulting whether it was best to attack him, because, as was true, his gun was not loaded. The mode of attack that the Pasumas adopt is to send forward a few of their braves to set fire to a village, while the main body remains near by to make attack as soon as the confusion caused by the fire begins. This is undoubtedly the safest and most effectual mode of attacking a kampong, as the houses of the natives are mostly of bamboo, and if there is a fresh breeze and one or two huts can be fired to windward, the whole village will soon be in a blaze. Though this seems to us a dastardly mode of warfare, the Pasumas are justly famed for their high sense of honor, their bitterest enemy being safe when he comes and intrusts himself entirely to their protection. When the Dutch troops arrived here, an official, who had frequently been up into their country, volunteered to visit the various kampongs and try to induce them to submit, and in every place he was well received and all his wants cared for, though none of the chiefs would, for a moment, entertain his proposals.

My journey on horseback was finished. The distance by the route taken from Bencoolen is about one hundred and twenty paals, or one hundred and twelve miles, but I had travelled considerably farther to particular localities that were off the direct route. I had chanced to make the journey at just the right time of year. The road is good enough for padatis and to transport light artillery. For most of the time a tall, rank grass fills the whole road except a narrow footpath, but the government obliges the natives living near this highway to cut off the grass and repair the bridges once a year, and I

chanced to begin my journey just as most of this work was finished. The bridges are generally made of bamboo, and can therefore be used for only a short time after they are repaired. Indeed, in many places, they are frequently swept away altogether, and are not rebuilt until the next year. From what I have already recorded, those who glory in hunting dangerous game may conclude that they cannot do better than to visit this part of Sumatra. To reach it they should come from Singapore to Muntok on the island of Banca, and thence over to Palembang, where the Resident of all this region resides, and obtain from him letters to his sub-officers in this vicinity From Palembang they should come up the Musi and Limatang to Lahat, when they will find themselves in a most magnificent and healthy country, and one literally abounding in game.