Chapter 1 Muscles Move Us

When you train muscles, you also train the systems that support them.

© MR.BIG-PHOTOGRAPHY/iStock

Exercise physiology is the study of how the body responds to exercise and physical training, so what better place to start this book than with skeletal muscle, the engines that move the body? During exercise, the muscles take center stage. While you’re also aware that heart rate has increased and breathing becomes heavier, it’s natural that you’re most tuned in to your muscles. After all, it’s the muscles you’re trying to change with exercise training. You might want your muscles to be stronger, or bigger, or more defined, or more flexible,

or more agile, or faster, or you might want them to have more endurance. With proper training, any of those improvements are possible. But muscles cannot function in isolation, and as you train the muscles, you’re also training the nervous system, heart, lungs, blood vessels, liver, kidneys, and many other organs and tissues. Planning an effective training program requires keeping in mind that big picture—a picture that involves more than just muscles. But because muscle is the foundation for movement, a review of muscle physiology 101 is a great place to start.

How Do Muscles Work?

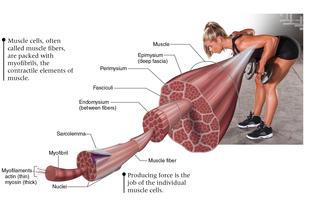

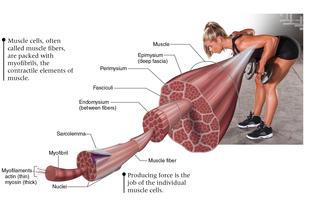

Take a quick look at figure 1.1. Similar figures appear in many textbooks because certain basic parts to skeletal muscle are important to recognize. When talking about muscle, you most likely think of skeletal muscles because those are the muscles that are involved in exercise and you can feel them working and tiring and aching. But cardiac muscle in the heart and smooth muscle in blood vessels and the gastrointestinal tract are also very much involved in supporting the body’s ability to exercise. Cardiac muscle and smooth muscle have different structures and functions. The focus here is on skeletal muscle, the muscles that move the body.

Figure 1.1 The structure of muscle. Even though skeletal muscles come in many shapes and sizes, they all share a common internal structure. Skeletal muscles are simply bundles of individual muscle cells (called fasciculi) arranged in groups controlled by individual nerves (alpha motor neurons; see figure 1.2) so that all the cells in the group contract in unison. Each

muscle cell is packed with contractile proteins (the myofibrils actin and myosin), enzymes (to help speed up reactions), nuclei (for protein production), mitochondria (for energy production), glycogen (the storage form of glucose used by the cell for energy), and sarcoplasmic reticulum (to aid contraction and relaxation; see figure 1.4). The structure of each cell is supported on the inside by a framework of proteins and on the outside by various types of connective tissues that support individual cells, bundles of cells, and the entire muscle. The terms endomysium, perimysium, and epimysiumrefer to these connective tissues.

Skeletal muscles are roughly 75% water. In other words, if you gain 10 pounds of muscle tissue, you actually gain 7.5 pounds of water and 2.5 pounds of contractile proteins and other cellular components. The basic job of muscle is to move bones around their joints. This requires that muscles contract with enough force to get that job done, whether that entails lifting a heavy weight once, sprinting a short distance, or cycling a long distance.

The Electrical Connection

Skeletal muscle fibers don’t contract on their own but usually require input from the brain (though some reflex movements involve spinal nerves and muscles). Figure 1.2 is a simple illustration of one nerve (a motor neuron) connected to three muscle cells. The motor neuron and its attached muscle cells are referred to as a motor unit. A single motor neuron may be connected to (innervate) dozens, or hundreds, or even thousands of individual muscle cells, depending on the size and function of the muscle. When the motor neuron fires, all of the muscle cells in that motor unit contract maximally. For movements that require little strength, such as picking up a fork, only a few motor units are activated. For movements that require maximal strength, a maximal number of available motor units are activated. When an untrained person begins strength training, most of the initial improvement in muscle strength over the first couple months is due to increased recruitment of motor units by the central nervous

system, a good example of how muscles operate in cooperation with other organ systems.

Motor units in the muscles controlling eye movements may contain as few as 10 muscle cells.

Figure 1.2 A motor unit, consisting of a motor neuron and the fibers it innervates.

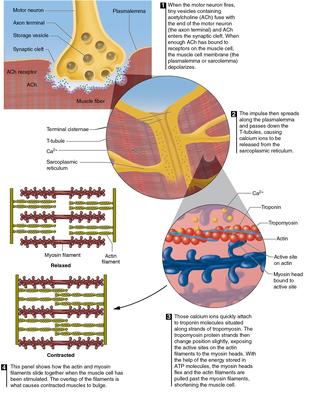

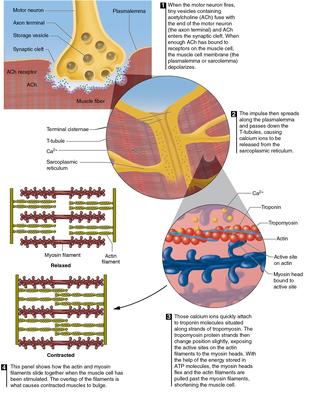

It’s important to understand how nerves cause muscles to contract because if that process is disrupted, strength is impaired, as detailed in chapter 4. Figure 1.3 is a simple overview of the various steps required for muscle to contract, which will give you a basic understanding (or review) of how skeletal muscle cells contract.

Figure 1.3 The series of events that cause muscle cells to contract. Here is the short version of how a muscle contracts: First, an impulse travels from the brain to the spine and from the spine down motor neurons to the muscle cells within those motor units. At the junction between the motor neuron and each muscle cell (called the neuromuscular junction), a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine is released into the space between the nerve and the muscle (that space is called the synapse or the synaptic cleft). The impulse is thereby transmitted from the motor neuron to all the muscle cells it innervates, causing those cells to contract in unison. Before the cells contract, the impulse has to first travel across the entire muscle cell membrane (the sarcolemma or plasmalemma), dipping instantaneously into the interior of each cell through T-tubules (transverse tubules). Each impulse causes calcium ions (molecules) to be released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum; this release of calcium ions causes muscle to contract (see figure 1.3 for more detail.) When the nerve impulse stops, the calcium ions are instantly taken back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the muscle cells relax.

Some alpha motor neurons can be more than 3 feet (about one meter) long.

Figure 1.4 makes it clear how the plasmalemma (sarcolemma) is connected to the T-tubules and how the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) surrounds the myofibrils within a single muscle cell. Jammed into the already-packed space inside muscle cells are a variety of enzymes needed for energy (ATP) production, glycogen molecules (the storage form of glucose), fat molecules, and other molecules and structures.

Figure 1.4 A muscle cell is a very crowded space. Everything about the cell supports muscle contractions, from single, all-out, maximalstrength contractions to the repeated contractions needed for sustaining endurance activities.

One of those other molecules is the protein titin. In recent years, scientists have learned that titin not only aids in maintaining the overall structure of the muscle fiber, keeping the sliding filaments (actin and myosin) in line, but it is also important in muscle strength, particularly as muscle lengthens (eccentric contractions). It seems that calcium ions cause titin to stiffen, helping to explain why muscles are so much stronger during eccentric (lengthening) contractions than during concentric (shortening) contractions. It may be that muscle cells actually contain three contractile proteins: actin, myosin, and titin.

Titin is the largest known protein, consisting of 34,350 amino acids. As a result, the formal chemical name for titin contains 189,819 letters and takes more than 3 hours

to pronounce, making it the longest word in the English language.

What Happens When Muscles Stretch?

Why do muscles feel tight whenever they are stretched? For example, when you try to touch your toes while the knees are locked, the hamstring muscles stretch and you feel that tension. But what causes the tension? For many decades, the prevailing theory was that the passive tension produced when a muscle is stretched was due to an increased tension in the connective tissues surrounding the muscles. It turns out those connective tissues may not be responsible for the forces produced when a muscle is stretched. Eccentric muscle contractions stretch muscle cells, reducing the opportunity for actin and myosin to interact. Yet eccentric contractions are very powerful. Recent research has shown that the structural protein titin may play an important role in force production during eccentric contractions. Titin is an enormous protein that acts like a spring inside each skeletal muscle cell. Stretch the cell and the titin molecules are also stretched. Just as a rubber band increases its tension when stretched, so does titin, adding to the force produced by actin and myosin. In that regard, titin may be considered the third contractile protein in muscle cells.

Different Cell Types for Different Jobs

Not surprisingly, there are different types of muscle cells, a characteristic that enables humans to perform explosive movements of short duration as well as complete amazing feats of endurance exercise. The muscle fiber (cell) types are simply referred to as type I (slow twitch) and type II (fast twitch). Type I fibers are better suited for endurance exercise and type II fibers are better suited for sprints or other brief, powerful movements. Figure 1.5 shows a cross-section of muscle stained to show the different fiber types. Motor units contain only one fiber type. The motor neurons that innervate type I motor units are smaller in diameter than the neurons that supply type II motor units. In addition to that

difference, type I motor units contain fewer fibers than type II motor units. As a result, type II motor units develop more force when they are activated.

Figure 1.5 Muscle cells are called on to accomplish all sorts of tasks, so it should be no surprise that cells are specialized for distinct functions.

Micrograph reprinted from W.L. Kenney, J.H. Willmore, and D.L. Costill, 2015, Physiologyofsportandexercise,6th ed. (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 39. By permission of D.L. Costill. Most muscles are roughly 50% fast-twitch and 50% slow-twitch, but these proportions can vary widely, as shown in table 1.1. Some elite distance runners have leg muscles in which over 90% of the muscle cells are slow-twitch (type I) fibers, while some elite sprinters have the opposite mix. Although the ratio of fiber types is determined by genetics, proper training can improve the function of any muscle cell —the very basis for greater fitness and performance. Arms and legs contain a similar proportion of type I and type II muscle cells, although those proportions vary from person to person.

How Do Muscles Adapt to Training?

In the simplest terms, when muscles are stressed by exercise, they gradually increase their capacity to handle that stress. For instance, muscles adapt to strength training by increasing the number of motor units that are recruited during weightlifting and by producing more myofibrillar protein (actin, myosin, and other proteins involved in muscle contraction). Those changes result in increased strength

and often increased muscle size. With endurance training, muscles adapt by increasing the number and size of energy-producing mitochondria as well as the enzymes used to break down glycogen, glucose, and fatty acids for energy.

All of these adaptations occur because regular training results in changes in the many nuclei contained in each muscle cell. The DNA in the nucleus of every muscle cell contains genes that are the blueprints for every protein within a muscle cell, such as contractile proteins, structural proteins, regulatory proteins, mitochondrial proteins, and enzymes. With training, changes in gene expression in the cell lead to increased levels of functional proteins.

As depicted in figure 1.6, the adaptations that eventually result from the stimulus of exercise training require a variety of facilitators to maximize the response. For example, the response to training will be less than optimal if the client or athlete is chronically dehydrated, eats poorly, and doesn’t get enough rest. Optimal response to training is made possible by the nervous, immune, and hormonal (endocrine) systems, all of which are disrupted by poor hydration, nutrition, and rest. In other words, for optimal responses to occur, a great training program has to be complemented by proper hydration, nutrition, and rest.

Figure 1.6 Muscle cells adapt to the stress of training in ways that improve the muscle’s capacity for exercise.

Genetics also plays a large role in the adaptations that result from training. Everyone adapts uniquely to exercise training because everyone has a unique genetic makeup. Genes determine the speed and magnitude of the response to training. Even if every athlete or client began a training program with exactly the same strength and fitness characteristics, some would adapt to the training faster than others, making greater gains in strength, speed, and endurance. In other words, some people are high responders and some are low responders. Sex also plays a role in the capacity for adaptations to training. For example, men’s muscles typically experience more hypertrophy as a result of strength training because of the greater testosterone levels in men. We’ll learn more about these differences later in this book.

Genetics plays a large role in adaptation because genetic makeup determines the upper limits of strength, speed, and endurance. For example, research has shown that 25% to 50% of maximal oxygen uptake ( O2max) is determined by genetics. The painful truth is that no matter how hard some people train, the highest O2max they may be able to attain might be lower than that of an untrained individual who has the genetic predisposition for a high O2max. The same is true for strength, speed, agility, flexibility, and other athletic characteristics.

If genes determine only part of the ability to adapt to training, what determines the other part? That’s where work ethic, dedication, rest, nutrition, and hydration enter the picture. The adaptations that result from exercise training require months of consistent hard work. That regular overload on the muscle, combined with adequate rest, proper hydration, and ample nutrition, creates and supports the intracellular environment that optimizes the production of all the functional proteins that are needed for increased strength, speed, and stamina.

Contracting muscles also operate as a muscle pump that assists the return of blood to the heart through the veins.

Adaptations to Aerobic, Anaerobic, and Strength Training

Muscles are the engines that move the body, and like all engines, muscles have to be fueled and cooled, and waste products have to be removed. Those jobs fall to the lungs, heart, vasculature, liver, and kidneys with the help of endocrine glands (such as the pituitary, hypothalamus, thyroid, pancreas, and adrenal glands). As muscles adapt to training, so do the tissues and organs that support muscle function.

Following is a list of many of the adaptations that result from aerobic (endurance) training, all of which help support the continued contraction of skeletal muscle during endurance exercise. This long list of adaptations is evidence that exercise is powerful stuff when it comes to promoting changes that improve health and performance.

© Christopher Futcher/iStock

Adaptations to Aerobic Training

In the Heart

Increased size of the heart (cardiac hypertrophy)

Increased thickness of the heart’s left ventricle

Reduced resting heart rate

Faster recovery of heart rate after exercise bouts

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Pooku and girded together the ti leaves as well as the ferns. Therefore I am now homeward bound to bury my bones on Kauai’s shore. If I should die it would be of no moment to him, but should it be he who shall pass away, my companion of many perils, I will weep for him alone at Kauai. Both of you go back.” When Kapaihiahilina finished what he had to say to the messengers, they went back, met the king and reported all that Kapaihiahilina had said.

In consequence of the statements made by the messengers Lonoikamakahiki became very much aggrieved. He immediately ordered his two canoe paddlers, Kapahi and Moanaikaiaiwa, also Kipunuiaiakamau and the adopted child of Kamahualele to prepare themselves for the voyage. Prior to Lonoikamakahiki’s sailing he commanded Kaikilani, Kealiiokalani, Kalanioumi and Keakealani thus: “I am about to go; stay on the land; let each of you care for each other and be

o ka hala o Pooku, a hume pu i ka malo laki, a me ka palai. A nolaila, ke hoi nei au a waiho aku na iwi ia Kauai. A ina he make no’u, aole hoi ana; aka ina he make nona no kuu hoa ukali ino, i Kauai no hoi au uwe mai. O u hoi olua.”

A pau ka Kapaihiahilina olelo ana i ua mau luna nei, alaila, hoi aku la laua, a halawai me ke alii (Lonoikamakahiki), a hai aku la i na mea a pau a Kapaihiahilina i olelo mai ai.

A ma keia mea a ua mau elele nei i olelo mai ai, he mea pono ole loa ia ia Lonoikamakahiki. A nolaila, hoolale ae la o Lonoikamakahiki i kana mau hoewaa elua, ia Kapahi a me Moanaikaiaiwa, o Kipunuiaiakamau ma, o ke keiki hookama o Kamahualele. A mamua o kona (Lonoikamakahiki) holo ana, kauoha ae la oia ia Kaikilani, Kealiiakalani, Kalanioumi, a me

Keakealani: “Eia wau ke hele nei, e noho oukou i ka aina, e nana kekahi o oukou i kekahi, mai kekeue oukou. Ina hoi i hele

not envious of one another. If I go and my companion harkens to me, then we will return; but should he listen not, then I will follow him, and by being persistent in my search he may relent, for anger only inflames and reaches the tips of the ears.”

Lonoikamakahiki having ceased his admonitions went aboard the canoes which awaited him and sailed away. In his search he met Kapaihiahilina at Anaehoomalu at the seashore at the dividing line of Kona and Kohala. Thus runs the tradition concerning Lonoikamakahiki’s search for his companion Kapaihiahilina:

When Lonoikamakahiki set sail on his search for his friend, Kapaihiahilina had already arrived at Anaehoomalu and soon afterwards was followed by Lonoikamakahiki and others.

Lonoikamakahiki saw Kapaihiahilina sitting on the sand beach when the canoes were being hauled ashore. Lonoikamakahiki immediately began to wail and also described

au a i maliu mai kuu hoa hele ia’u, alaila, hoi mai maua, aka hoi i maliu ole mai kela, alaila, ukali aku no au mamuli ona (Kapaihiahilina), a malia paha o maliu mai i ka ukali loihi ia aku. Oi-e, he makole ka huhu, o hele a ka lihi pepeiao.”

A pau ka Lonoikamakahiki olelo ana i keia mau olelo, kau aku la oia iluna o na waa a holo aku la. Ia imi ana a Lonoikamakahiki, halawai aku la oia me

Kapaihiahilina ma Anaehoomalu, ma ke kaha, ma ka palena o Kona a me Kohala. A penei no ka moolelo oia imi ana a Lonoikamakahiki.

I ka manawa i imi aku ai o ua o Lonoikamakahiki, ua pae mua aku o Kapaihiahilina i Anaehoomalu a mahope aku lakou nei (Lonoikamakahiki ma).

A i ka manawa i ike aku ai o Lonoikamakahiki ia

Kapaihiahilina e noho mai ana i kaha one, ma kahi e kau ana na waa o lakou (o Kapaihiahilina ma), alaila, uwe aku la o Lonoikamakahiki, ma ka uwe

their previous wanderings together. Kapaihiahilina recognizing the king also commenced wailing. When they came together and had ceased weeping and conversing, then Lonoikamakahiki made a covenant between them, that there would be no more strife, nor would he harken to the voice of slander which surrounds him, and in order that the understanding between them should be made binding, Lonoikamakahiki [362]built a temple of rocks as a place for the offering of their prayers and the making of oaths to Lonoikamakahiki’s god to fully seal the covenant.

helu ana, e like me ka laua hele ana. A ike mai la no hoi o Kapaihiahilina i ka uwe helu aku a ke alii, alaila uwe helu mai la no hoi oia.

A ia laua i halawai ai, a pau ka laua uwe ana a me ka laua kamailio ana, alaila kau iho la o Lonoikamakahiki i olelo hoohiki mawaena o laua, aole e loaa hou kekahi [363]kue, aole hoi e hoolohe i na olelo akiaki a kona mau aialo. Aka, i mea e paa io ai ka laua hoohiki, nolaila, kukulu iho la o Lonoikamakahiki i wahi ahu pohaku (heiau), i wahi no laua e pule ai me ka hoohiki imua o ke akua o Lonoikamakahiki, no ka hoopaa ana i ko laua hoohiki ana.

Kapaihiahilina observed that Lonoikamakahiki was sincere in his desires and at that moment gave his consent to return with Lonoikamakahiki. After their religious observance at this place they returned to Kona and resided at Kaawaloa, in South Kona.

A ike aku la o Kapaihiahilina ua hooiaio mai o Lonoikamakahiki i kana hoohiki ana, ia manawa ko Kapaihiahilina ae ana aku e hoi me Lonoikamakahiki. A pau ka laua kapu heiau ana malaila, hoi aku laua i Kona, a noho iho la ma Kaawaloa, ma Kona Hema.

(Tradition says because of the (Ua oleloia ma ka moolelo o ko

covenant entered into for the erection of the mound of rocks at Anaehoomalu, the boundary between Kohala and Kona was named Keahualono, and that place has been known ever since by that name signifying the erection of a mound of rocks by Lonoikamakahiki.)

After Lonoikamakahiki and Kapaihiahilina had returned home he resumed the office of premier as formerly. After his reinstatement to his former position a conference was held between him and the king as to how to get rid of the slanderers of Kapaihiahilina from the royal presence. It is stated that Kapaihiahilina had refused to return to Kona with Lonoikamakahiki at the time they met at Anaehoomalu, the exact conversation running as follows: “I will not return with you again until those who slandered me be got rid of from your presence; then only will I return with you.” By reason of this the conference was held. Lonoikamakahiki sought the wishes of Kapaihiahilina as to what

laua hana ana i olelo hoohiki no ke kukulu ana i ke ahu pohaku ma Anaehoomalu, ua kapaia ka inoa o ia palena mawaena o Kohala a me Kona “O Keahualono”; o ka inoa mau ia oia wahi a hiki mai i keia manawa; oia hoi ke kukulu ana o Lonoikamakahiki i ahu pohaku).

A i ka hoi ana o Lonoikamakahiki me Kapaihiahilina, noho hou iho la o Kapaihiahilina ma kona noho kuhina nui e like me ka noho mua ana. A mahope mai o ko Kapaihiahilina noho kuhina hou ana, alaila, kukakuka ae la o Kapaihiahilina me

Lonoikamakahiki, i mea e kaawale aku ai ka poe nana i niania wale ia Kapaihiahilina mai ke alo alii aku. No ka mea, ua hoole aku ua o Kapaihiahilina ia Lonoikamakahiki i ko laua halawai ana ma Anaehoomalu. A penei ka olelo ana: “Aole au e hoi hou aku me oe, aia a kaawale aku ka poe nana i niania wale ia’u mai kou alo aku, alaila, hoi aku au me oe.” A no ia mea, i kukakuka ai o Lonoikamakahiki me

Kapaihiahilina. Aka, ua ninau

disposition should be made of his slanderers, whether they should be slain, and if that, it was agreeable to him also. Should Kapaihiahilina express the desire to banish them, Lonoikamakahiki would acquiesce to that also. Lonoikamakahiki was bent on satisfying Kapaihiahilina’s every wish.

aku o Lonoikamakahiki i ko

Kapaihiahilina manao no ka poe nana i niania wale oia, ina paha o ka make ko Kapaihiahilina makemake, oia no; alaila, o ko

Lonoikamakahiki makemake no ia. A ina o ke kipaku ko

Kapaihiahilina makemake, alaila pela no, o ko Lonoikamakahiki manao no ia. E like me ka

Kapaihiahilina mea e koi ai, malaila aku no o Lonoikamakahiki.

At the conference stated for the consideration of this matter

Kapaihiahilina decided to put to death those who had slandered him. In order to mitigate the horrible death which the slanderers would meet, by actual killing, it was decided that they should die in war. In this manner were the slanderers put out of existence. Kapaihiahilina ever after became firmly entrenched as a favorite, and he acted as premier even up to the time of his death.

A nolaila, ma kela kuka ana a laua ma keia mau mea, ua hooholo ko Kapaihiahilina manao, e pau i ka make ka poe nana i niania aku. Aka hoi, i mea e pau ai ko lakou make mainoino ana ma ka pepehi maoli aku, nolaila, ua waihoia ko lakou make maloko o ke kaua ana. A pau iho la ka poe nana i niania wale ia Kapaihiahilina i ka make. A mahope iho o ia manawa, kau pono iho la o Kapaihiahilina ma kona noho punahele ana, ma ka aoao kuhina nui a hiki i kona make ana.

Thereafter, and up to the time of Lonoikamakahiki’s death, there

Ma ia hope mai a hiki i ko Lonoikamakahiki make ana, aole

were no more wars, no rebellions; all was peaceful. After Lonoikamakahiki’s death it is said that the kingdom of Hawaii became the patrimony of Keakealani, and from his reign on to that of the successive kings until the time of Kamehameha, we are told by tradition that no great wars ever again took place. During the reign of Keoua, however, the several district chiefs rebelled. [257]

he mau kaua ana, aole no hoi he kipi, he maikai wale no. A hala o Lonoikamakahiki i ka make, ua oleloia, ua lilo ke Aupuni o Hawaii ia Keakealani. A mai ka manawa i lilo ai o Hawaii ia Keakealani a hiki i na ’lii aimoku mahope mai ona, a hiki ia

Kamehameha, aole i ikeia ma keia moolelo na kaua nui ia manawa. Aka, i ko Keoua manawa i noho ai ke kipi ana o na alii aiokana. [364]

Lonoikamahiki, frequently referred to as Lono, was a grandson of Umi by his wife Kapukine-a-Liloa ↑

Father of Lono. ↑

A famous game of the ancients, the slender spears for which were made from the hard, close-grained, heavier woods; a sort of javelin, some five or six feet in length, thicker at one end. ↑

This was a stone disk for rolling along, or down, regularly prepared courses; a very popular game of olden time. ↑

Another great gambling game. This favorite game of Hawaiians was, as here shown, a test of strength and skill in gliding or skipping the arrow along the ground the greatest distance While

the bow was known among the people, it had no use in these arrow contests ↑

The club was a war weapon which was much practiced with to attain proficiency in the various right-, or lefthand, or other “strokes” therewith, termed the hauna shortened from hau ana. There are marvelous tales told of the skill of famous warriors in its use, as also of the enormous size and magic power of many noted implements. The favorite club of a chief or warrior was named, and was thereafter identified with him ↑

Umu, or imu; a ground oven of heated stones ↑

This was the general war weapon of the aliis and their immediate attendants, their body guard, with which much practice was had to attain skill in its use as a weapon of offense and defense Spears were not the general army weapon. ↑

The account here given of the use of the sling was as a war weapon; it was also used for sports and betting contests. Slings were made of coconut fibre, usually with much care. ↑

An apparent recognized custom of a child’s seeking favor, or recognition, as in the case of Umi on his visit to Liloa. ↑

This alleged ignorance of idols in one at Lono’s age, so closely related to the head of the system, is difficult to understand, unless it was purposely designed by his kahus (guardians) until

he had reached the years of discretion, when he was to be made familiar with the idols and their supposed significance and powers It was not so in the case of Liholiho who assumed some of the temple services of his father, Kamehameha, at a very early age. ↑

Implying, you cannot be hidden from him. ↑

Hoopaapaa is to dispute; wrangle; contend stubbornly; debate; to have a mental contest of language and wit. Sometimes given as hoopapa. ↑

This is said to be the first instance of a chiefess ruling in Hawaii, although tradition shows Kauai to have been so governed much earlier. ↑

All articles seem to have special names, whether a clothes container, club, or famed kahili. ↑

A favorite pastime of the chiefs; a game very much resembling checkers. ↑

This is a covert phrase for identification; a play upon the name of her lover’s father, Kalaulipali. ↑

These casual remarks as a chant indicating a situation in the game, are quoted in konane contests to this day. ↑

This revolt was an evidence of Kaikilani’s popularity, which revolt, however, she would not countenance ↑

All chiefs of note are supposed to possess name songs in their

honor. ↑

This reveals the method of memorizing name songs, etc., of olden time. ↑

In the spirit of rivalry existing between these kings this new name chant was an opportune test of their powers of memory and narration. ↑

Liu, generally accepted as mirage, and so here used, is probably a shortening of liu-a, to see indistinctly; otherwise the definitions of the word fail to apply ↑

Iliau (Wilkesia gymnoxiphium); a low plant, something of the silversword order, found on Kauai and elsewhere. ↑

Aliaomao, said to be the god of the year, of which there are doubts. Alia was the name of two sticks carried before the procession as emblems of the god; hence, perhaps, the idea that Omao was the god referred to Some versions of this chant give it as Aliaopea. ↑

Series of names of personages ↑

Falling this way and that; topsy-turvy conditions. ↑

Lonoikamakahiki, referring to himself. ↑

Another version gives this line as Noi aku Kamahu a ola; Kamahu asked for and obtained life, in place of Kamahuola asked, as in this case. ↑

A royal ancestor running back some ten generations ↑

The narrator here pauses in his boasting changes ↑

Over or above Alaeloa, in Kaanapali, Maui. ↑

The chanter here enters on a play of names. ↑

All west Maui lands ↑

The other version gives this as Hokea; likely an error. ↑

Paie intended probably for Paia, Maui. ↑

Probably intended for Kahoolawe, though its connection is not clear ↑

Hills likened to the palm-thatched houses of the temple ↑

Oopu, a small mud-fish, said to be so tame as to cling to one’s hand. ↑

Kala (Monoceros unicornis), a sacred fish. ↑

Loyal devotion and self-sacrifice, as Loli was one of the two guardians who reared Lono from early childhood. ↑

Ahi (Germo germo), albacore ↑

The reference made throughout this tradition to the “god of Keawenuiaumi” never once reveals its name It must have been the god Kaili which Liloa transmitted the charge of to Umi, and doubtless descended to Keawenuiaumi, thence to Lonoikamakahiki. ↑

Ulua (Carangus ignobilis), as also other varieties; credited as the

gamiest fish in Hawaiian waters. ↑

In the former version this is given as Honokea. ↑

A plea for recognition ↑

The kissing of olden time is well borne out in its native term, “honi ka ihu, ” touch or smell the nose ↑

Lono realizes the duplicity of these adherents of Kakuhihewa, seceders from Hawaii’s court ↑

Or, “I will flay you alive.” ↑

Showing the method of enshrouding and decorating the bones of the alii. ↑

This was probably one of high rank rather than a chief, in which case it refutes the idea that the wohi was a “royal title assumed only by the Oahu chiefs of the highest rank until comparatively modern times.” ↑

The important battle of Puumaneo here spoken of must have been a rebellion against Keawenuiaumi. The carrying about of the bones of the vanquished chiefs by a successor of the victor is shown in this case to have been for the purpose of evidence, and they are identified by one who participated in the conflict. ↑

This closing line of these several chants simply indicates it as sectional; a sort of “to be continued.” ↑

Some confusion prevails in the brother-cousin term of relationship used by the translator, which arises from the fact that the word kaikaina

applies equally to a younger brother or a cousin The same difficulty occurs in the term makuakane as father or uncle, and makuahine as mother or aunt ↑

The koolauwahine of the original was a peculiar wind of Kauai ↑

A more literal rendering would be, “We have seen the god weep.” ↑

A peculiar grass, of legendary fame, found on Kauai. Also the name of a choice lace-like kapa. ↑

Ohai, a flowering shrub (Sesbania grandifolia) which turns its leaves down at night. ↑

The erection of this historic temple of Puukohola is generally credited to Kamehameha I, in obedience to the instructions of Kapoukahi, Kauai’s renowned prophet, whereby he would obtain supremacy over Hawaii without more loss of life Pol Race, vol I, p 240 According to this tradition it is shown that Kamehameha’s work was simply one of reconstruction and reconsecration to his war god Kukailimoku, for victory over his opponents, and it is a coincidence that the same deity as Kaili, Lono’s war god, presided here, as also at the heiaus of Muleiula, in Kohala, and Makolea in Kahaluu, Kona, in their consecration by Lono as acknowledgment for his victories. Ib., p. 122. ↑

The war being directed by the priests instead of by tried warriors of the king shows their notion of being

directed by the deities in temple services ↑

A lively similitude of utter routing. ↑

By the force of wind in the swirl of the war club ↑

Elder son of Kaikilani by Kanaloakuaana; hence, likely, the assistant toward his escape ↑

Puholo: to cook by steaming. The food desired to be cooked is placed in a container, usually a calabash, together with the ingredients necessary to make it palatable; one or more hot stones are dropped into the container and it is covered up and left to steam till cooked. Food prepared in this way is more delicious than when kalua-ed (underground cooking) ↑

Three successive mouthfuls, or by the time required for its chewing. ↑

A proverb of ridicule. ↑

An insight this of Hawaiian strategy and method of warfare ↑

Koae, the bos’n bird (Phaëthon lepturus) ↑

Low in comparison. ↑

Popolo, a medicinal herb (Solanum nigrum, L ); an article of food, also, when cooked. ↑

Kamakahiwa, the black eye, from having had his eyes tatued ↑

Kanaloa refers to Kanaloakuaana. ↑

An epithet of same. ↑

Paweo, averted eye; used here to signify the sightless pearl-oyster of Ewa lagoon, famed as sensitive to sound, thereby enabling it to sense the presence of man. ↑

Olowalu, tumultuous noise; announcement of chief’s kapus, etc. ↑

Name of one of the sacred drums introduced by Laamaikahiki ↑

Realizing he has been entrapped, Kamalalawalu begins to sue for peace ↑

Keep on with the battle until one of us is on the altar, as an eminent authority puts it, the meaning of which is virtually, to fight on till death, when will be seen who is the bravest Nananuu, or lananuu, was the tall scaffold structure in the temple wherein the sacrifice was placed, and in front of which stood the idols and the lele, or altar. ↑

Paimalau, bait boxes; receptacles for live bait preferred in aku fishing. ↑

Hala kaao, unripe fruit of the pandanus. ↑

A mythical tree credited to Kauai ↑

An awa of especially satisfying quality. ↑

Awa lau hinano describes a fragrant awa resembling in perfume the hinano blossom of the pandanus. ↑

Continuous changing rains ↑

Kinau, a sand eel. ↑

[Contents]

H������ �� K�����.

CHAPTER I.

K�����’� C�������� ��� D�����.

In the legends and traditions the names of a large number of chiefs are spoken of that do not appear in the genealogical records from Opuukahonua to Liloa, and even from then on to Kamehameha. The name of Kualii is omitted in the genealogical records of the chiefs, but his history and doings have often been spoken of.1 It is told that Kualii was once king of these islands, and in one of his characters2 he was known to have possessed certain knowledge from a god, and at times even assumed the real attributes of a supernatural being.

Kualii was a celebrated chief and noted for his strength and bravery; he was known to have won all the battles fought by him, defeating his enemies every time. He was also known for his great desire for war. It is said of Kualii that he began fighting battles in his childhood and so continued until he reached manhood. The following story exhibits some of the extraordinary traits in the character of this man.

When he was well advanced in life and unable to walk, he ordered his servants to make him a network of strings (koko).3 And in accordance with the wish of Kualii his servants proceeded to carry it out. In the engagement of Kualii here on Oahu, against the chiefs from Koolauloa, sometime after the reign of Kakuhihewa over Oahu, or possibly at a time prior to the reign of Kakuhihewa (the exact time not being very clearly ascertained), which engagement was to be upon the plains of Keahumoa at Honouliuli, Ewa, he was carried by his men in a network of strings. No actual fighting occurred, however, as the

M������ � K���

MOKUNA I. K� K����� A�� � �� K��

Ma na kaao a me na moolelo, ua nui na alii i papa hoonohonoho mookuauhau mai a Opu Liloa, a ma ia hope mai a hiki ia Kamehameh ikeia ma ka papa hoonohonoho mookuauhau kamailio mau ia nae kona moolelo no kona a Ua oleloia o Kualii he alii no Hawaii nei, a o k akua ka mea nona mai kona ike, a he akua m kekahi ano i kekahi manawa.

He alii kaulana o Kualii, no ka ikaika a me ke oia iloko o na hoouka kaua maluna o kona p oia no kona puni kaua. Ua oleloia o Kualii, ua mai ka manawa kamalii mai a hiki i kona hoo mea kupanaha no Kualii; i ka manawa i elem ke hele, alaila, kauoha ae la oia i kona mau k like me ka makemake o Kualii, a pela i hana kanaka.

A i ka hoouka kaua ana o Kualii ia Oahu nei mai, i ka manawa mahope mai o ko Kakuhih Oahu nei, a i ole ia, i ka manawa paha mam Kakuhihewa noho alii ana, (aole nae i maopo hoouka kaua ana i ke kula o Keahumoa ma koko kona laweia ana, i auamoia e na kanak kaua ana, ua hoomoe wale ke kaua, a hui na wale.

O ka nui o na kanaka o Kualii ma ia hoouka like me umikumamalua tausani, a o ka nui o

two armies upon coming together entered into a declaration of peace.4 The number of men under Kualii in this contest was three mano,5 which is equal to twelve thousand, and the number of men comprising the other army was three lau, which is equal to twelve hundred; and the reason why the battle was not fought is told in the following story.

Kapaahulani the elder and his younger brother Kamakaaulani were men who were in search of a new master6 or lord, so they composed a mele, or chant, and after it was completed placed it to Kualii as his name. Shortly after the two men had completed [366]the mele they held a conference as to the proper course for them to follow in order that they might both reap equal benefit. Following is how they decided which course to pursue while all by themselves and before the mele was made public:

“Since we have composed and completed this mele, you (Kamakaaulani) must therefore go and give its name to Kualii, and I (Kapaahulani) will go to the other chief and urge him to make war upon Kualii. And when we become acquainted of the place where the battle is to be fought7 then you are to take Kualii to the place and there conceal yourselves in the bushes.You are to leave a mark on the road, however, so that I may be informed of your being there. I will then stand and chant this mele that we have just composed.”

After completing their arrangement, Kamakaaulani gave out the mele which was known as the name of Kualii. Some considerable time after this, these two brothers again got together and decided upon the time when they should bring about what they had agreed upon. The following is what they said at this last meeting while by themselves:

Kamakaaulani: “You go to the chief of Koolauloa8 and bring him to the plains of Keahumoa9 where we will conceal ourselves. When you see a knotted ti leaf and the tail of a small fish (aholehole)10 on a pile of sugar-cane peelings, then remember that it is the sign that we are there and you can stand on that spot and chant the mele. This must, however, be on the eve of Kane.11 You will find us on the plains of Keahumoa.” As soon as this was agreed upon, Kapaahulani proceeded on his way to meet the chief of Koolauloa. When Kapaahulani reached Waialua where the chief of Koolauloa had come and was residing for the time being, soon after his arrival there he

kaua ekolu lau, ua like me hookahi tausani e moolelo no ia hoouka kaua ana i hoopau wa

O Kapaahulani ka mua, a o kona kaikaina o kanaka imi haku laua, a na laua i haku i mele inoa no Kualii. I ka manawa nae i haku ai ua ke mele, alaila, kuka ae la laua i mea e pono mea e loaa like ai ia laua like ka pomaikai. [3

A penei ka laua olelo ana, oiai o laua wale m o ka puka ana o ua mele nei ma ke akea: “H nei kaua i keia mele a holo, alaila, e hele oe hooili aku i ka inoa no Kualii, a owau hoi (Ka kela alii, e lawe mai e kaua ia Kualii. Aia a m hoouka ai ke kaua, alaila, malaila oe e lawe pee oukou ma ka nahelehele, e hoailona oe waiho ai ma ke alanui, i maopopo ai ia’u aia ku no wau a kahea aku i ke mele a kaua e ha olelo, alaila hooili aku la o Kamakaaulani i ke a lilo iho la ia he inoa no Kualii.

He mau manawa he loihi ma ia hope mai, ala laua i ka manawa e hookoia ai ka laua mea i ka laua olelo kuka hope, oiai o laua wale.

Kamakaaulani: “E hele oe a ke alii o Koolaul ke kula o Keahumoa, malaila makou e pee a oukou, a i ike oe i ka lai i nipuu ia, a me ka h ana maluna o ka puu ainako, alaila, e manao e ku ae no oe a kahea ae i ua mele la. Aia na Kane a ao ae, e loaa no makou ma ke kula o laua olelo, alaila, hele aku la o Kapaahulani e Koolauloa.

I kekahi manawa o Kapaahulani ma Waialua o Koolauloa malaila ia manawa, hoolauna ak alii, me ke koi aku e kii e kaua ia Kualii.

introduced himself to the chief, and thereupon urged him to go and make war on Kualii.

On a certain evening while the priests and the chief were watching the heavens in order to discover if they could defeat Kualii, the astrologers, after a careful study, were certain that their army would not be able to overcome the army of Kualii. When Kapaahulani heard the decision arrived at by the priests of the chief of Koolauloa, he remarked to one of the chief’s attendants: “You go to the chief and tell him for me that his priests are mistaken in their interpretations.” Upon hearing this remark made by Kapaahulani, the man went and said to the chief: “O Chief, that man (Kapaahulani) has just said that your priests are mistaken in their interpretations.” The chief replied: “You go and bring that man to me. Let him come and say what he has told you.”

Kapaahulani was then sent for and he was brought in the presence of the chief, who asked him: “Is it true that you have said that my priests are mistaken in their interpretations?” Kapaahulani replied to the chief: “Yes, it is true your priests are [368]mistaken in their interpretations; because according to what I have seen, being also a great priest, and in accordance with the knowledge gathered by my ancestors and handed to me by them, your priests have indeed made a mistake in their interpretations to you, O Chief.” Upon hearing this the chief asked Kapaahulani: “What are your interpretations then? It is proper that you relate them.” Kapaahulani then replied to the chief: “My interpretations are these: If we go and make war upon Kualii, we will be victorious in that battle. I believe that if we could go and make war upon Kualii tomorrow, and it should happen that we meet him in the early morning, that by noon the battle would not be fought;12 but if we happen to meet his army at noon time we would defeat him early in the evening.”

Because of these remarks, the chief thereupon ordered his men, amounting to three lau (twelve hundred) to get ready to go to war. That night they went to the upper part of Lihue, and from there on down to Honouliuli, till they arrived on the plains of Keahumoa, just as the sun was coming up. At this same time Kapaahulani saw the mark agreed upon by him and his brother. He then rushed to the front of the army to the chief warriors and spoke to the people in the chief’s immediate circle as follows:

“Say, Nuunewa (the chief warrior), we are surrounded by the enemy. I had thought that we would be the victors if

I kekahi ahiahi, i na kahuna a ke alii e nana a mea e maopopo ai ko lakou lanakila ana ma nana ana a na kahuna kilokilo lani, ua maopo ko lakou puali maluna o Kualii. A lohe aku la olelo a na kahuna a ke alii o Koolau, alaila o kamaaina e pili ana i ke alii: “E hele oe a ke a olelo ua lalau ka ike a na kahuna a ke alii.”

A no keia olelo a Kapaahulani, alaila, laweia olelo imua o ke alii, a hai ia aku la me ka i ak olelo mai nei kela kanaka (Kapaahulani) ua l kahuna au.” I mai la ke alii: “E kii oe i ua kan olelo i kana mea i kamailio mai nei ia oe.”

Alaila, kiiia aku la o Kapaahulani, a laweia m ninau aku la: “He oiaio anei, ua olelo mai nei kuu mau kahuna?” I aku la o Kapaahulani i k lalau ka ike a ko mau kahuna; aka, ma ko’u i nui, e like me ka mea i aoia ia’u mai ko’u ma ia’u, he lalau io no ka ike a ua mau kahuna n

A no keia mea, olelo aku la ke alii ia Kapaah ike? E pono ke olelo mai.”

Olelo aku la o Kapaahulani i ke alii: “O ka’u i kaua ia Kualii, alaila, e lanakila no kakou ma manao nei wau, ina e kii kakou i ka la apopo kakou me ke kaua i ka ehu kakahiaka, hoom awakea. A ina hoi i halawai kakou me ke kau hee ia kakou i ka ehu ahiahi.”

A no keia mea, hoolale ae la ke alii i na pual kumamalua haneri), ka nui o na koa, e hoom ke kaua. Ma ia po, hele ae la lakou a uka o L iho i Honouliuli, a hiki lakou i ke kula o Keahu ana mai a ka la e puka. Aia hoi ike aku la o K hoailona a laua i a’oa’o ai; ia manawa, lele m mamua o ka pu kaua o ke alii, a olelo aku la alii: “E Nuunewa (ka pukaua), ua puni kakou nei hoi na kakou ke kaua e hiki mua ianei, ei kakou i ke kaua. Nolaila, e kuu ae wau i kuu pule i keia kakahiaka, pakele kakou, aka, i ku ino kuu pule i keia la, pau kakou i ka make.”

we arrived here first, but I see that we are surrounded. Therefore I will chant my prayer, and if it should be acceptable this morning, we will be saved; but if I chant my prayer and it should end badly this day, then we will all be killed.”

Because of these remarks spoken by Kapaahulani, the chief’s priests spoke up saying: “It does seem strange. You told us that we would not be surrounded by the enemy, and that we would be victorious if we were to reach this place first; but it now turns out that we are surrounded by the enemy.”

The chief then spoke up: “Stop your remarks. We have staked the life and death of the army in his keeping, therefore we must abide by what he says. If what he says is true, that we are indeed surrounded by the enemy, then it will redound to his own good, and he shall be rewarded. But in case he lies and is deceiving us, then my firm command as to his treatment is this: he shall die, and all his relations also, and death shall gather up even those who befriend him.”

Kapaahulani then stood up in the presence of the army and prayed by chanting the mele composed by him and his brother [370]

A no keia olelo a Kapaahulani, olelo ko’a ma me ka i mai: “He mea kupanaha! Olelo mai n kakou e puni ana i ke kaua, na kakou ke kau wahi; eia ka hoi, ua puni iho nei kakou i ke ka

I mai ke alii: “Ua oki ka oukou olelo, ua kuu a me ka make o ka puali ia ia nei. Nolaila e po hoolohe i ka ia nei olelo. A ina he oiaio ka ia ka kakou i ke kaua, alaila o kona pono no ho aka, he wahahee na ia nei, alaila, eia kuu ole e make ia nei, a make mai me kona hanauna make a hiki i kona poe hoaikane mai.”

Ia manawa, ku ae la o Kapaahulani imua o k ma ke mele a laua i haku ai me kona kaikain

CHAPTER II.

THE CHANT13 AS REPEATED BY KAPAAHULANI.

A messenger14 sent by Maui15 , Sent to bring Kane16 and Kanaloa, Kauakahi17 and Maliu.

While great silence prevails as prayers are being uttered; While the oracles of Hapuu18 are being consulted, O Chief. 5

The great fish-hook of Maui, Manaiakalani19 was its fish-line, The earth was the knot.20 Kauiki21 like the winking stars towering high. Hanaiakamalama22 [lived there]. 10

The bait was the alae23 of Hina Let down to Hawaii,

KA PULE ANA A KAPAA

He elele kii na Maui, Kii aku ia Kane ma, laua o Kanalo

Ia Kauakahi, laua o Maliu. Hano mai a hai a hai i ka pule, Hai a holona ka Hapuu e Kalani.

Ka makau nui a Maui, O Manaiakalani kona aha, Hilo honua ke kaa.

Hauhia amoamo Kauiki; Hanaiakamalama. 10

Ka maunu ka alae a Hina.

Kuua ilalo i Hawaii, Kahihi kapu make haoa,

MOKUNA II.

Tangled with the bait24 into a bitter death,25

Lifting up the very base26 of the island

To float on the surface of the sea.27 15

Hidden by Hina28 were the wings of the alae.

Broken was the table29 of Laka.

Carried far down to Kea,30

The fish seized the bait, the fat, large ulua.31

Luaehu,32 offspring of Pimoe, O thou great chief!33 20

Hulihonua the husband, Keakahulilani the wife;34

Laka the husband, Kapapaiakele the wife; Kamooalewa the husband, Nanawahine his wife; 25 Maluakapo the husband, Lawekeao the wife; Kinilauaemano the husband, Upalu his wife;

Halo the husband, Koniewalu the wife; 30 Kamanonokalani the husband, Kalanianoho the wife; Kamakaoholani the husband, Kahuaokalani the wife; Keohokalani the husband, 35 Kaamookalani the wife; Kaleiokalani the husband, Kaopuahihi the wife; Kalalii the husband, Keaomele the wife; 40

Haule the husband, Loaa the wife; Nanea the husband, Walea the wife; Nananuu the husband, 45 Lalohana the wife; [372] Lalokona the husband, Lalohoaniani the wife; Hanuapoiluna the husband, Hanuapoilalo the wife; 50 Pokinikini the husband, Polehulehu the wife; Pomanomano the husband, Pohakoikoi the wife; Kupukupunuu the husband, 55 Kupukupulani the wife; Kamoleokahonua the husband, Keaaokahonua the wife; Ohemoku the husband, Pinainai the wife; Mahulu the husband, 60 Hiona the wife;

Kaina Nonononuiakea

E malana i luna i ka ili kai. 15

Huna e Hina i ka eheu o ka alae, Wahia ka papa ia Laka, A haina i lalo ia Wakea.

Ai mai ka ia, o ka ulua makele, O Luaehu, kama a Pimoe, e Kala

O Hulihonua ke kane, O Keakahulilani ka wahine; O Laka ke kane, o Kapapaiakele

O Kamooalewa ke kane, O Nanawahine kana wahine; 25

O Maluakapo ke kane, O Lawekeao ka wahine; O Kinilauaemano ke kane, O Upalu ka wahine; O Halo ke kane, o Koniewalu ka w O Kamanonokalani ke kane, O Kalanianoho ka wahine; O Kamakaoholani ke kane, O Kahuaokalani ka wahine; O Keohokalani ke kane, 35 O Kaamookalani ka wahine; O Kaleiokalani ke kane, O Kaopuahihi la ka wahine; O Kalalii la ke kane, O Keaomele la ka wahine; 40 O Haule ke kane, O Loaa ka wahine; O Nanea ke kane, O Walea ka wahine; O Nananuu ke kane, 45 O Lalohana ka wahine; [373] O Lalokona ke kane, O Lalohoaniani ka wahine; O Hanuapoiluna ke kane, O Hanuapoilalo ka wahine; 50 O Pokinikini la ke kane, O Polehulehu la ka wahine; O Pomanomano la ke kane, O Pohakoikoi la ka wahine; O Kupukupunuu la ke kane, 55 O Kupukupulani ka wahine; O Kamoleokahonua ke kane, O Keaaokahonua ka wahine; O Ohemoku ke kane, O Pinainai O Mahulu ke kane, 60 O Hiona ka wahine; O Milipomea ke kane,

Milipomea the husband, Hanahanaiau the wife; Haokumukapo the husband, Hoao was the wife; 65 Lukahakona the husband, Niau the wife; Kahiko the husband, Kapulanakehau the wife; Wakea the husband, 70 Papa the wife.

A chief was conceived and born, a great red fowl.

A chief was Pineaikalani, thy grandfather, A chief who begot a chief, Bearing innumerable offspring.35 75

Mixed are the seed of the noble chief, Clamoring to be recognized

As being of thy stock, O dread chief.

A chief ascending, urging on, opening upwards

Until the heaven is reached,36 where the king is held fast.

80

This, O Ku, Kualii is thy name.37

Dost thou not already stand at its height?38

O Ku, thou axe of chiefly edge!39

The train of clouds40 along the horizon doth march

For Ku, the edge of the sea is drawn41 down by Ku. 85

The sea of Makalii, the sea of Kaelo,

The rising sea in Kaulua.

The month of Makalii42 in which the food bears leaf, The worm that eats as it crawls, even to the rib.

The sea-crab43 that ate the bone of Alakapoki 90 Who was the parent of Niele of Lauineniele,44

The people of the water 45

Ku, the king of Kauai.

Kauai with its high46 mountains.

Spread down low is Keolewa,47 95

Niihau and the others48 are drinking the sea.

Ah, it is Kiki and his company that are at Keolewa, Kamakauwahi and his company that are above, O Hawaii.

Hawaii of high mountains; 100

Towering unto heaven is Kauiki.49

Down at the base50 of the islands, Where the sea holds it fast.

Kauiki, Kauiki the mountain, 105 [374]

Like the sea-gull flapping its wings when about to fall.51 Kauai, Great Kauai inherited from ancestors.52

O Hanahanaiau ka wahine; O Haokumukapo ke kane, O Hoao no ka wahine; 65

O Lukahakona ke kane,

O Niau ka wahine;

O Kahiko ke kane, O Kupulanakehau ka wahine; O Wakea la ke kane, 70

O Papa ka wahine.

Hanau ko ia ka lani he ulahiwa nu

He alii o Pineaikalani, ko kupunak

Hanau ka lani he alii;

Hua mai nei a lehulehu; 75 Kowili ka hua na ka lani;

Lele wale mai nei maluna.

Ka leina a ka lani weliweli.

He alii pii aku, koi aku, wehe aku,

A loaa i ka lani paa ke alii. 80

E Ku e (Kualii), he inoa.

Ina no oe, i ona?

O Ku o ke koi makalani!

Kakai ka aha maueleka,

Na Ku! kohia kailaomi e Ku! 85

Kai Makalii, kai Kaelo,

Kai ae Kaulua.

Ka malama hoolau ai a Makalii

O ke poko ai hele, ai iwi na.

Ka pokipoki nana i ai ka iwi o Alak

O ka makua ia o Niele o Lauineni

O kanaka o ka wai.

O Ku, ke alii o Kauai.

O Kauai mauna hoahoa, Hohola i lalo o Keolewa. 95

Inu mai ana Niihau ma i ke kai-e.

O Kiki ma ka kai Keolewa.

O Kamakauwahi ma ka kai luna e O Hawaii.

O Hawaii, mauna kiekie. 100

Hoho i ka lani Kauiki; Ilalo ka hono o na moku,

I ke kai e hopu ana O Kauiki.

O Kauiki i ka mauna 105 [375]

I ke opaipai, e kalaina e hopu ana

O Kauai.

O Kauai nui kuapapa,