Praise for Navigating Institutional Racism in British Universities

“In this groundbreaking and thought provoking book, Katy Sian explores and examines the persistence of racism in British universities. She carefully documents the realities of daily life for black and minority ethnic academics working in higher education. Ofering a set of important recommendations, this book is crucial for those interested in challenging discriminatory cultures. A timely and courageous intervention.”

—Richard Burgon MP, Member of Parliament for Leeds East, Shadow Secretary of State for Justice and Shadow Lord Chancellor, UK

“In the wake of student cries to decolonise and the scandal of endemic racism in higher education, there can be no better time for Katy Sian’s powerful forensic analysis to enter the stage, bringing clarity, wisdom and hope to the many people of colour who strive to survive in the heart of whiteness that is the British academy.”

—Heidi Safa Mirza, Professor of Race, Faith and Culture at Goldsmiths, University of London, UK. Co-editor Dismantling Race in Higher Education: Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy

x Praise for Navigating Institutional Racism in British Universities

“White supremacy fnds expression in multiple ways; sometimes it screams from the barrel of a gun, at other times it operates through the hidden business-as-usual routines of everyday life that constantly exclude, oppress, belittle and do violence to people of colour. Sian’s book fearlessly documents and challenges the racism that lies at the heart of British universities. Tis is a passionate, complex, and conceptually nuanced book that exposes the multiple ways in which racism defnes higher education and ofers practical steps in shaping the changes that must happen.”

—David Gillborn, Director of the Centre for Research in Race & Education, University of Birmingham, UK. Editor of ‘Race Ethnicity and Education’

“Tis is an outstanding book which resonates with my own survival in the academy. Katy Sian brilliantly excavates and exposes the hidden operations of racism through Critical Race Teory story-telling of racially marked academics and the epistemic violence they endure on a daily basis. Tis book is essential reading for White senior and middle leaders in British universities. Te question remains, will they read it and act to change practice within their own university?”

—Vini Lander, Professor of Race and Teacher Education, University of Roehampton, UK

1 Introduction

Debunking the ‘Liberal’ University

Tis book has been a long time coming. If we start the story from my PhD, I have been in the academy for around twelve years. Tis, I believe, is a sufcient amount of time to deliver a ‘longitudinal’ piece of ethnography that is refexive and most of all candid and critical. Let me begin with a few disclaimers. Tis is not a book that has been interfered with, or shaped by, a clinical, soulless, REF criterion.1 Te ‘originality,’ ‘signifcance,’ and ‘rigour’ of the text to follow, is not for a small group of white professors—sitting on a research committee—to deliberate or determine. Tese folks are likely to be ill-equipped to deal with the issues raised by this book, for it requires them to confront their own histories and current practices. In that sense, this piece of research is most defnitely not concerned with striving for a ‘high star rating’ that will go onto contribute to detached, neoliberal university league tables. Tis book isn’t written by an ‘angry’ woman of colour; it isn’t antiwhite, nor is it simply seeking to be ‘reactive’ or ‘polemical.’ As a female academic of colour who is perhaps able to ‘pass’ racial lines more easily than others (superfcially, rather than structurally), who isn’t deemed too

© Te Author(s) 2019

K. P. Sian, Navigating Institutional Racism in British Universities, Mapping Global Racisms, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14284-1_1

‘ethnic,’ and who holds a degree of job stability, I am writing this book because I realize that I am perhaps in a slightly better position to do so than some of my peers. It arises from years of observation, on-going conversations with academic friends from across the globe, and the development of a voice that hopes to be fearless and in keeping with the spirit of the invaluable mentoring I received, and continue to receive, from an academic of colour. Te book might be best read as a collectively driven piece of work. It seeks to centre the voices of my respondents and creatively engage with their journeys as well as my own, taking seriously the anger, the tears, the laughter and most of all the strategies adopted to challenge the white academy. It is a book for all those who want to actively, and profoundly think about how we might transform the university both structurally and conceptually. Tis is not an exhaustive rant, nor a story of victimhood. Tis is a narrative of survival and resistance in a space that continues to exclude, devalue and dismiss our being.

Racism is the dirty secret hiding behind a string of superfcial tag lines that have come to brand universities across the UK. Te following myths about the ‘liberal’ university can often be seen touted in marketing brochures, job announcements and website pages promoting the values and responsibilities of the institution:

Myth 1: Universities encourage inclusivity and diversity

Myth 2: Universities invest in racially marked academics

Myth 3: Universities are ‘post-racial’

Myth 4: Universities desire curriculum reform

Myth 5: Universities are committed to race equality

Beyond these false advertising scams, the real message is clear and simple: Racism in British universities is endemic. Tis is not ‘hot of the press.’ Academic research has pointed to this fact for well over 20 years.2 Alongside the research, there is also a catalogue of data that explicitly shows the bleak prospects for racially marked academics. To understand the longevity of institutional racism within British universities, one must interrogate its racial history, its white supremacist politics,

and its patterns of privilege. Whiteness is a system of violence. Te university is structured by whiteness. It follows then, that the university is both a transmitter and a maintainer of violence. By violence I mean that which is both systemic/structural and epistemic/symbolic. As the book exposes throughout, such articulations of violence interplay and intertwine to produce a series of long-term harms that are legitimized by racist power structures. Te failure of senior managers to accept or even acknowledge the existence of systematic racism operating in their universities, departments, faculties, and boardrooms is where the heart of the problem lies. Over decades the default option has been to ignore the issue, meaning that structurally nothing signifcant has changed. Racism isn’t necessarily worse for racially marked academics today; it is as hard now as it was back in the 1950s for racially marked academics to prosper in universities. Te climate however has undoubtedly changed creating new pressures and demands making the space more difcult to navigate for those who dare to enter this demanding career.

Aims and Objectives

Informed by a series of in-depth conversations and personal refections, this book sets out to critically examine the experiences of racism encountered by racially marked academics working within British universities. Te text seeks to investigate the various ways in which racism in the academy is performed, maintained and reproduced. Trough its rich insights and conceptual enquiry, this book explores both the structural and interpersonal nature of racism enacted in spaces of higher education. It unpacks a range of complex and challenging questions and engages with the way in which racial politics in the university can be seen to intersect with broader issues around gender. Te book presents a textured narrative around the key barriers facing racially marked academics, and aims to enhance understandings of institutional racism in British universities. It seeks to develop a series of practical recommendations to encourage and support the participation of racially marked academics in higher education. Tese issues are of increasing relevance for

all those in the sector, particularly in the wake of contemporary global issues such as internationalization, decolonizing the curriculum, and the ‘diversity’ agenda.

Te need for this book is clear. Statistics around Black and Minority Ethnic (BME)3 representation in universities continue to demonstrate that racially marked academics are marginalized from British universities. Data generated from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) in 2012/2013 revealed that out of 17,880 professors, only 85 were Black, 950 were Asian, 365 were ‘other’ (including mixed), while the majority 15,200 were White (Bhopal 2015: Runnymede Trust). In terms of black female professors there are just 17 in the entire British university system (Runnymede Trust: 2015), and in January 2017 the Guardian newspaper reported that for the third year in a row, HESA fgures recorded no black academics in the elite staf category of managers, directors and senior ofcials in 2015/2016 (Adams 2017: Guardian). Alongside the data there is also extensive literature documenting on-going practices of institutional racism in universities, including the gutting of race equality policy, limited access to career advancement, fewer opportunities for promotion, and daily experiences of discrimination (Sian 2017: 1–26). Te persistence of racism in British universities shows that at the top very little has been done to encourage progress and racial equality.

Book Outline

Chapter 2 will provide some refections on method. It will map out the broader conceptual approach, which is informed by critical race theory and black/postcolonial feminism. Such frameworks will enable readers to understand both the lived experiences and the structural dimensions of power operating within British universities. Tese tools allow for key insights into the ways in which university spaces are structured and patterned by racism. As a female academic of colour, I will also engage with auto-ethnography to allow my own refections to run throughout the text.

My conversations with racially marked academics unravelled the complex interplay between microaggressions and practices of institutional racism. All of my respondents opened their interviews by detailing a series of incidents related to their day-to-day experiences in their departments as a way to set the scene about the space that they inhabit. Chapter 3 will thus focus on the performance of these everyday exclusionary interactions and examine how they operate to reinforce structures of whiteness in the academy. Te chapter will draw upon issues concerning subtle forms of racism—or liberal racism, feelings of isolation, ‘otherness,’ and hyper-visibility and invisibility. In this chapter, the resemblance across the responses will be highlighted as a way to point to the widespread nature of institutional racism. It will uncover the ways in which covert, structural processes of racism—both implicitly and explicitly—maintain systems of whiteness at the expense of racialized bodies; who are positioned as outsiders.

Te classroom is often thought to represent a ‘safe space’ that promotes critical learning, the exchange of ideas, and pedagogical tools to generate future knowledge. However, the university classroom is not free from racial (and gendered) politics, therefore for many racially marked academics, the classroom is also the site in which students express feelings of white resentment, white guilt and white privilege. My data demonstrates the challenges that racially marked academics encounter when teaching including, having their authority undermined, feeling ridiculed, and often being fearful to teach the next class. Chapter 4 will as such draw upon the emotional and psychological strains of teaching within British universities, and explore how racially marked academics have attempted to navigate this complex space.

Interrupting hegemonic forms of knowledge in British universities requires a deep sense of structural transformation. Te social sciences curriculum in particular, is central in reproducing Eurocentric knowledge arising from the European colonial enterprise. Tis knowledge is problematic as it is based upon a narrow set of ideas, racial classifcations, and ‘universal truths’ to maintain a distinction between the ‘modern’ and ‘civilized’ West, and the ‘primitive’ ‘uncivilized’ Non-West. Calls to critically challenge the reproduction of these knowledges form the basis for the movement to decolonize the curriculum. Chapter 5 sets

out to examine the difculties that my respondents have faced in their attempts to unsettle conventional social science curricula. It will also demonstrate the importance of creating new epistemological spaces in enabling educators and students to engage with ‘other’ knowledges and situate global issues in nuanced frameworks.

British universities have ensured that a range of diversity and equality policies have been generated to promote positive action and inclusion. However, despite these strategies, my respondents consistently documented experiences of being unsupported, undervalued, and their contributions being dismissed. All my respondents expressed feelings of instability in the academy with very little guidance and reassurance from senior members of staf. Chapter 6 will address issues around lack of mentorship, insecurities around job stability, and barriers to career progression.

Chapter 7 will explore the various strategies of resistance that my respondents have developed as a way to navigate, resist, and survive racism in university spaces. It will provide a detailed exploration of the various mechanisms that they have adopted to deal with racism, and also discuss the importance of, and challenges around, developing wider networks to ensure support and solidarity. Te chapter will examine the diferent channels available for racially marked academics and the activity that has already taken place to successfully manage, and cope with, challenging environments that are structured by institutional racism.

Chapter 8 will set out a series of recommendations for policy and practice in British universities around how to challenge racism efectively. It will discuss the importance of providing clear access to paths for progression to ensure that racially marked academics can fully participate within the sector. It will propose that in order to understand the root causes of the persistent position of disadvantage experienced by racially marked academics, a conceptual and proactive dialogue is required around institutional racism, Eurocentric knowledge production, and the destabilizing of whiteness. Te book concludes by refecting upon how we might transform the structures of racism inherent within British universities, and indeed if such transformation is even possible.

Notes

1. REF refers to the ‘Research Excellence Framework.’ It is a system for ‘evaluating’ the quality of research across universities in the UK.

2. For example of such literature, see: Neal, S. (1998) Te Making of Equal Opportunities Policies in Universities, Buckingham: Open University Press; Modood, T., and Ackland, T. (1998) Race and Higher Education, London: Policy Studies Institute; Gillborn, D. (1995) Racism and Antiracism in Real Schools: Teory, Policy, Practice, Buckingham: Open University Press; Mirza, H. (1992) Young, Female and Black, London: Routledge; Bhopal, K. (1994) ‘Te Infuence of Feminism on Black Women in the Higher Education Curriculum,’ in Davies, S., Lubelska, C., and Quinn, J. (Eds.) Changing the Subject: Women in Higher Education, pp. 124–137, London: Taylor and Francis.

3. Te term ‘BME’ refers to a category that emerged in the UK to classify ethnically marked populations that were distinct from the idea of the white European national majority. Prior to the BME classifcation, ethnically marked populations were grouped as ‘coloured’ and then ‘black’ (Cumberbatch 2009: 160). Tere is a debate around how such collective terms exclude and include various population groups. BME, like BAME (Black And Minority Ethnic), BOEM (Black and Other Ethnic Minority), or BEM (Black and Ethnic Minority)—and other classifcations—are contested concepts and are likely to remain so in a racialized environment such as that of Britain. In this book, the use of the term BME is pragmatic rather than devotional.

References

Adams, R. (2017, January 19). British Universities Employ No Black Academics in Top Roles, Figures Show. London: Guardian. https://www. theguardian.com/education/2017/jan/19/british-universities-employ-noblack-academics-in-top-roles-fgures-show.

Bhopal, K. (2015, July 17). Te Experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic Academics. London: Runnymede Trust. https://www.runnymedetrust.org/ blog/the-experiences-of-black-and-minority-ethnic-academics.

Cumberbatch, M. (2009). Multiculturalism Is an Essential Part of the Antiracist Struggle. In A. Pilkington, S. Housee, & K. Hylton (Eds.), Race(ing)

Forward: Transitions in Teorising ‘Race’ in Education (pp. 149–166). Birmingham: Centre for Sociology, Anthropology and Politics (C-SAP), Higher Education Academy.

Runnymede Trust. (2015). Black Students Must Do Better Tan White Students to Get into University. London: Runnymede Trust. https://www.runnymedetrust.org/news/594/272/Black-Students-Must-do-Better-than-WhiteStudents-to-get-into-University.html.

Sian, K. (2017). Being Black in a White World: Understanding Racism in British Universities. International Journal on Collective Identity Research, 176(2), 1–26.

A Brief Refection on Methods and Conceptual Framings

Research Method

Tis book is a collection of diferent voices who have shared with me their pain, their strength, their challenges, their courage, and their resistance to racism in the academy. For years I have found myself engaged in the same conversation with academics of colour, from all over the globe, always prompted by the question, ‘so how is work?’ Te familiar response is that of an eye roll, followed by a sigh, and even a slight laugh, alerting the other to what we already know, what we already feel, and what we are already experiencing in our own university. And just like that we share; we share the all too recognizable stories, the frustrations, the relief that we are not alone, paranoid, or being unreasonable. We listen, we laugh, and we see in each other’s eyes that we are together in our struggle. We smile, because in that moment we feel stronger, and grateful that we have had the space be heard. I am thankful to my academic friends of colour who over the years have listened to me, allowed me to share, and provided me with the strength and support that I would have never had gotten elsewhere.

© Te Author(s) 2019

K. P. Sian, Navigating Institutional Racism in British Universities, Mapping Global Racisms, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14284-1_2

Tese conversations equipped me mentally, they prepared me practically, and in doing so they helped me to survive my workplace. As I continued in my academic career, I soon got to thinking what about all those who are unable to share, who haven’t had the luxury of having others to speak too, who have felt alone, excluded and isolated? And so the foundations of the book began, as I sought to speak with those who hadn’t had the opportunity to fully communicate the depth and complexity of their answer to the question, ‘so how is work?’ My interviews, or conversations as I prefer, were with academics of colour and of diference, all at various stages in their careers. Academics of diference refer to those who may be considered in their own nations as white, however, are unable to make this white privilege travel to a post-Brexit Britain. As a result, they begin to experience degrees of racialization that ethnically mark them as subaltern (Hesse and Sayyid 2006: 21–24). However, there is also recognition that although they may be subjected to particular forms of exclusion, academics of diference still maintain a much greater degree of privilege compared to academics of colour. Tat is, academics of diference are far more able to mobilize and call upon a set of cultural resources that remain unavailable to academics of colour.

Due to the variation of my respondents, we can see the way in which ‘diferential racialization’ both develops and unfolds (Chan et al. 2014: 4–5). Te book is therefore cognizant of the diverse racial histories that my respondents occupy, and makes no attempt to homogenize or generalize their experiences, but rather seeks to critically explore how they difer, overlap, and intersect with other categories of oppression against the landscape of the white academy. Te respondents will thus be referred to as racially marked academics, as a way to capture the diverse experiences through which practices of racial ‘othering’ take place. We will see the complex ways in which cultural, ethnic, religious, and phenotypical identifcations interconnect in the marking out, or racialization, of those considered ‘outside’ dominant forms of whiteness (Moore 2003: 273–274; Meer and Modood 2010: 77; Sian 2017: 40). Trough these varied patterns of racialization, we will also uncover the ways in which race-making processes inform, shape, and impact wider exclusionary social relations in the academy.

When our conversations opened, that same eye roll, that same sigh, and that same uncomfortable laugh, was to be seen and heard, signalling immediately that one familiar feeling, exhaustion. Whether in my ofce, in their ofce, or in a cofee shop the conversations fowed. For some, it was like they had needed the space to fnally get things of their chest, a therapy session, where they could speak about their experiences in the academy. As various encounters were shared, there were tears, sometimes from them, and at other times from me. Tere was laughter, there was anger, and there was pain. Undeniably, there was also a sense of defance, perseverance, and resistance. Some conversations were particularly emotional and harder than others. On some occasions, hours and even days after they had taken place, I found myself replaying their experiences in my head overcome with a deep feeling of sadness that our bodies had all been injured in someway or another by systemic, structural, and symbolic manifestations of racism in our universities.

As I write these words I receive a text message from a close friend, who is an academic of colour working outside the UK. Disturbed and angry she details an incident in which she had to call out her white colleague’s blatant racism, which left her feeling anxious. We dissect the encounter, I give her the space to unload and then ofer reassurance. As we exit the conversation she thanks me and writes, ‘I needed not to be alone with it.’ At this point it couldn’t be clearer to me that the act of sharing these all too frequent occurrences is signifcant both for our healing and our recovery. It also works as an important reminder that these conversations, both formal and informal, are disturbingly commonplace. It alerts me to all the energy and labour that we have to invest in order to manage and minimize the physical and psychological harm that these incidents so often provoke.

Te experiences documented throughout this book sit alongside snippets of my own personal encounters, to form what might be described as a map for others to use to help them to navigate their own clashes with racism in the university. I hope to take away that sense of isolation and exclusion that we, as racially marked academics, so often feel, by demonstrating that we are in it together, and that we are not alone in the racism that we experience on a daily basis in our white institutions. I had 20 conversations in total. I spoke with a fairly equal mix

of male and female respondents, ranging from early career, mid-career, and advanced career academics, working either as lecturers or researchers, on permanent, part-time or fxed-term contracts. Tey come from a range of racial, ethnonational, and religious groups and are based at Russell Group and Post-1992 universities across Britain,1 broadly located within the social sciences and humanities disciplines. Te book is organized around key themes arising from the conversations, based upon microaggressions and day-to-day ofce politics; teaching and decolonizing the curriculum; promotions and career advancement; and resistance. Tis piece should therefore be read as a collective body of work, where our voices have come together to reveal our shared struggles in the white academy.

I don’t wish to get too distracted here by detached methodological concerns around sampling, objectivity, validity and so on. Te statistical data on under-representation already does a stellar job of ‘quantifying’ racism in the academy, my participants and their experiences therefore need not be subjected to classifcation or measurability, for this is a text of rich documentation in which the ‘evidence’ speaks lucidly for itself. Trough what is typically described as critical (auto)ethnography, the text to follow makes no attempt for claims of universality or scientifc ‘truths,’ but rather it seeks to present the persistent and widespread nature of racism in British universities, by demonstrating both its everydayness and structural nature. Tat is, I am primarily focused on understanding how experiences are signifed, constructed and represented within institutional cultures (Hall 1992: 290–292; Sayyid and Zac 1998: 249–268). My reluctance around detailing a grand methodological design is twofold. First it expects me to provide information that I am unwilling to share, in particular, regarding the specifcities of my sample. Te requirement to do so in order to prove ‘rigour’ is symptomatic of broader, problematic procedures inherent within the social sciences that are unable to understand or respect the real anxieties that people of colour encounter as a result of participating within such research. Tis leads to the second point which is that which refuses to reproduce, or worse, celebrate, a narrow, European, empirical framework that is assumed to be the only legitimate way to conduct meaningful research.

Such refusal might be loosely described as partaking within the project to decolonize methodologies, which would certainly be in keeping with the overall tone of the book. Tat is, this research actively steps out of essentializing, Eurocentric discourses. It takes the shared experiences, narratives and voices seriously by centring, rather than marginalizing, their textured accounts. As Hartej Gill, Kadi Purru, and Gloria Lin point out, adopting a decolonial research framework allows us to, ‘claim, reclaim, support and legitimize “other” epistemological positions in the academy’ (2012: 11). It is a serious attempt to dismantle the conventional research binary of insiders and outsiders, and uncovers instead, ‘a complicated, fuid and messy process rather than a clearly defned methodology’ (ibid.). A decolonial posturing, as Goodwin Y. Agboka describes, ‘is an invitation to deconstruct Western-infuenced research traditions and essentialist perspectives through collaborations between researchers and non researchers’ (2014: 303). Tis book thus situates itself within the spirit of a decolonial methodological approach, which arises from a close engagement with the data to develop an analytical critique of praxis associated with coloniality and racism.

Conceptual Tools

Te conceptual frameworks that this book aligns itself with are critical race theory (CRT) and black/postcolonial feminism. CRT and black/ postcolonial feminism enable rich insights into understanding the complex ways in which performance and practice are both enacted and conditioned by structures of race and gender (Chan et al. 2014: 4–7). Combined they allow me to examine the ways in which lived experiences interplay with wider structural dimensions of power operating within universities. Both are instruments that facilitate social justice for racially marked groups (ibid.). CRT emerged during the 1970s in the US as a response to the ‘rolling back’ of the advances made by the 1960s Civil Rights Movement (Delgado and Stefancic 1993: 461). It sought to critically address the multifaceted relationship between race, racism, and the law, by deploying new theories and ideas to capture this complexity (ibid.). CRT initially developed as a critique of law

(Chan et al. 2014: 4), as a means to uncover the ways in which legal discourse has been embedded and reproduced to legitimize, and support racist power structures (Crenshaw 1988: 1350). It has since expanded its scope, shifting from legal scholarship to encompass and address the historic, systemic, and routinized confgurations of racism. Tandeka Chapman and Jamel Donnor point to the way in which, as a conceptual lens CRT, ‘provides a legal, historicized framework for explicating and analyzing how policies and institutionalized practices reinforce inequities’ (2015: 138), that is, it links the historical production of race and racism to contemporary exercises of marginalization, oppression, and subordination in organized and everyday settings (ibid.). In doing so it enables us to both recognize and identify the intricate ways in which race has manifested itself within systems and structures to reenact discourses of white supremacy.

In this sense CRT refers to a framework that attempts to broadly, ‘critique social reality and the dynamics of power between race discourse and institutions, bodies, and subjectivity, specifcally to reveal that racism is ordinary and normalized’ (Chan et al. 2014: 4). Te normalization, the ordinariness, and the ‘everydayness’ of racism (Essed 1991), is of particular interest for those of us engaged with CRT, as it allows for an analysis which treats racism as ‘not aberrant’ (Delgado 1995: xiv), but rather as that which is sewn into the very tapestry of Western societies, in other words, CRT compels us to understand that racism is ‘enmeshed in the fabric of our social order, it appears both normal and natural to people in this culture’ (Ladson-Billings 1998: 11).

David Gillborn argues that CRT thus recognizes that racism is not only that which refers to overt forms of racial hatred, but also that which relates to hidden practices of power that disadvantage racially marked communities (2006: 22). CRT is therefore a project that directly challenges liberal conceptions of racism, which tend to mask its structural and systemic nature. Trough the centering of racism, CRT calls for a rich, scholarly analysis that is ‘engaged in the process of rejecting and deconstructing the current patterns of exclusion and oppression’ (ibid.: 27). Related to this, a key element of CRT is the notion of interest convergence, which alerts us to the way in which racism advances the privileges and benefts of the white establishment (Bell 1980),

racism thus becomes a tool that is mobilized by white elites to serve their own interests.

Interwoven with the decolonial methodological framework as outlined in the previous section, an important practical component of CRT is that which recognizes the strength of storytelling (LadsonBillings 1998: 8). Storytelling is an essential feature of CRT as it helps us, ‘to build a powerful challenge to “mainstream” assumptions’ (Gillborn 2006: 24). As Gillborn goes onto describe, such an approach allows us to understand and refect upon, ‘the importance of context and the detail of the lived experience of minoritized peoples as a defence against the colour-blind and sanitized analyses generated via universalistic discourses’ (ibid.: 23). It provides racially marked communities with a critical space to write our own narratives, open up new questions, and unsettle essentializing discourses. Storytelling in this sense becomes not only a creative art form, but also a valuable political tool that speaks back at, challenges, and resists oppressive structures of whiteness. CRT has clear signifcance and relevance for this book. Trough its analytical understandings and rich insights, CRT enables me to craft a refective yet elucidative account of racism in British universities, directly informed by my own experiences, as well as those of my participants. At the heart of this book is a story of racism, and CRT allows me to unapologetically develop this as the focal point, it does not force or compel me to bring in a series of other ‘social indicators’ that will detract from its centrality. Te story to follow is one that not only takes seriously the normalization of racism in universities, but also recognizes at the same time how its normalization is bound up and interconnected with the wider workings of (white) structural power. It challenges liberal notions of racism that are entrenched within the university setting, and critiques processes and practices that continue to privilege whiteness at the expense of racially marked bodies. Trough its complexities, its nuances, and its potential to disrupt, CRT has been the only home from which I desire to write and tell this story.

Te book also engages with broader elements of black/postcolonial feminist thought, which connects with CRT to furnish a language of resistance, solidarity, and liberation, as Heidi Mirza argues, ‘the contingent and critical project of black and postcolonial feminisms is to chart

the story of raced and gendered domination across diferent landscapes’ (2009: 2). Black/postcolonial feminism is drawn upon to unravel the patterning of gendered racism, as a way to understand the racial oppression and exclusion experienced by my respondents as that which is, ‘structured by racist and ethnicist perceptions of gender roles’ (Essed 1991: 31). In doing so, we are able to illuminate the practices by which both racially marked women and men are disciplined and marginalized through racist, essentialist discourses, that replay and reafrm earlier reductive, white supremacist, classifcations. Te book thus takes into account that while the racism manifests itself diferently upon female and male racially marked bodies, it nonetheless remains organized by racist constructions of gender roles (e.g. ‘passive brown woman’; ‘black male rapist,’ etc.) (ibid.). By carefully considering the diferent ways in which race and gender interplay and interact, we are able to identify how multiple oppressions are layered upon bodies of diference, to further restrict and prevent their participation and advancement in university spaces, that assume hegemonic forms of whiteness, maleness, heterosexuality, and ableism.

In taking the lived, embodied experience as politically relevant, black/postcolonial feminism allows us to understand the varied ways in which diference is inscribed upon the racially marked body, and identify how those etchings unfold through practices of exclusion (Ahmed 2004: 117–139). By situating my experiences alongside those of my respondents, I am, to quote Patricia Hill-Collins, ‘one voice in a dialogue among people who have been silenced’ (2002: ix). Tis has enabled for the development of a community of voices that are deeply involved within a collective critique of racism in British universities. We are therefore, ‘engaged in the process of quilting a genealogical narrative of “other ways of knowing”’ (Mirza 2009: 2). Tese ‘other ways of knowing’ become important sites of resistance, empowerment and intervention. By focusing on what Mirza describes as ‘embodied diference’ the book addresses the complex processes of ‘being and becoming a gendered and raced subject’ (ibid.). Documenting the experiences in such a way thus allows for agency and representation, whereby the interactions, interfaces, and intersubjectivities become a central, rather than a marginal, feature of the book.

Combined then, CRT and black/postcolonial feminism provide valuable, analytical tools for both imagining and reimagining the destabilization of racialized and gendered systems of oppression that currently exist in the British university. Te methodological and conceptual frameworks of this book can therefore be seen as those that situate themselves as an attempt to interlink a set of theoretical and practical questions. Te story to follow is concerned with understanding the structural and symbolic patternings of racism in higher education, as well as revealing the way in which racism is embodied, internalized and resisted in the performances of racially marked academics. Tat is, conceptually and methodologically, this account recognizes the agency of those of us involved in this dialogue, and with that agency, it opens up the prospect of imagining an anti-racist university.

Note

1. Te Russell Group represents 24 UK universities. Tese are often considered to be “elite” institutions that have a reputation for academic excellence and producing highly rated research. Post-1992 universities refer to previous tertiary education teaching institutions (polytechnics) that were granted university status under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.

References

Agboka, G. (2014). Decolonial Methodologies: Social Justice Perspectives in Intercultural Technical Communication Research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44(3), 297–327. Ahmed, S. (2004). Afective Economies. Social Text, 79, 22(2), 117–139. Bell, D. (1980). Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93(3), 518–533. Chan, A., Dhamoon, R., & Moy, L. (2014). Metaphoric Representations of Women of Colour in the Academy: Teaching Race, Disrupting Power. Borderlands, 13(2), 1–26.

Chapman, T., & Donnor, J. (2015). Critical Race Teory and the Proliferation of U.S. Charter Schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(1), 137–157.

Crenshaw, K. (1988). Race, Reform, Retrenchment: Transformation and Legitimation in Anti-discrimination Law. Harvard Law Review, 101(7), 1331–1387.

Delgado, R. (Ed.). (1995). Critical Race Teory: Te Cutting Edge. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (1993). Critical Race Teory: An Annotated Bibliography. Virginia Law Review, 79(2), 461–516.

Essed, P. (1991). Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Teory. Newbury Park: Sage.

Gill, H., Purru, K., & Lin, G. (2012). In the Midst of Participatory Action Research Practices: Moving Towards Decolonizing and Decolonial Praxis. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 3(1), 1–15.

Gillborn, D. (2006). Critical Race Teory and Education: Racism and Antiracism in Educational Teory and Praxis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 27(1), 11–32.

Hall, S. (1992). Te West and the Rest: Discourse and Power. In S. Hall & B. Gieben (Eds.), Formations of Modernity (pp. 275–332). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hesse, B., & Sayyid, S. (2006). Te Postcolonial Political and the Immigrant Imaginary. In N. Ali, V. Kalra, & S. Sayyid (Eds.), A Postcolonial People: South Asians in Britain (pp. 13–31). London: Hurst and Company.

Hill-Collins, P. (2002). Black Feminist Tought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just What Is Critical Race Teory and What’s It Doing in a Nice Field Like Education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7–24.

Meer, N., & Modood, T. (2010). Te Racialisation of Muslims. In S. Sayyid & A. Vakil (Eds.), Tinking Trough Islamophobia, Global Perspectives (pp. 69–83). London: Hurst.

Mirza, H. (2009). Plotting a History: Black and Postcolonial Feminisms in “New Times”. Race Ethnicity and Education, 12(1), 1–10.

Moore, R. (2003). Racialization. In G. Bolaf, R. Bracalenti, P. Braham, & S. Gindro (Eds.), Dictionary of Race, Ethnicity and Culture (pp. 273–274). London: Sage.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

usually there is a long slender beak; the legs are elongate, frequently hairy; the tarsi bear long pulvilli and a small empodium. The Empidae are an extensive family of flies, with predaceous habits, the rostrum being used by the female as an instrument for impaling and sucking other flies. They are occasionally very numerous in individuals, especially in wooded districts. There is great variety; there are nearly 200 species in Britain. The forms placed in the subfamily Hybotinae are curious slender little Insects, with very convex thorax and large hind legs. In Hemerodromia the front legs are raptorial, the femora being armed with spines on which the tibiae close so as to form a sort of trap. Many Empidae execute aërial dances, and some of the species of the genus Hilara are notorious for carrying veils or nets in the form of silken webs more or less densely woven. This subject is comparatively new, the fact having been discovered by Baron Osten Sacken in 1877,[414] and it is not at all clear what purpose these peculiar constructions serve; it appears probable that they are carried by means of the hind legs, and only by the males. Mik thinks that in H. sartor the veil acts as a sort of parachute, and is of use in carrying on the aërial performance, or enhancing its effect; while in the case of other species, H. maura and H. interstincta, the object appears to be the capture or retention of prey, after the manner of spiders. The source of the silk is not known, and in fact all the details are insufficiently ascertained. The larvae of Empidae are described as cylindrical maggots, with very small head, and imperfect ventral feet; the stigmata are amphipneustic, the thoracic pair being, however, excessively small; beneath the posterior pair there is nearly always a tooth- or spinelike prominence present.

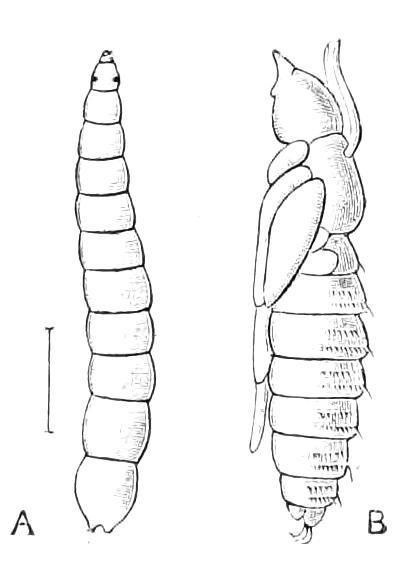

Fig. 235 A, Larva, B, pupa of Medeterus ambiguus. France. (After Perris.)

Fam. 27. Dolichopidae.—Graceful flies of metallic colours, of moderate or small size, and long legs; usually with bristles on the thorax and legs, the halteres exposed, squamae being quite absent; antennae of two short stout joints (of which the second is really two, its division being more or less distinct), with a thread-like or hair-like appendage. Proboscis short, fleshy. Claws, pulvilli, and empodium small; wings with a simple system of nervures, those on the posterior part of the wing are but few, there is no anterior basal cross-vein between the discal and second basal cells, which therefore form but one cell. This is also a very extensive family of flies, of which we have probably about 200 species in Britain. They are conspicuous on account of their golden, or golden-green colours, only a few being yellow or black. The males are remarkable for the curious special characters they possess on the feet, antennae, face, or wings. These characters are not alike in any two species; they are believed to be of the nature of ornaments, and according to Professor Aldrich and others are used as such in courtship.[415] This family of flies approaches very closely to some of the Acalyptrate Muscidae in its characters. It is united by Brauer with Empidae to form the tribe Orthogenya. Although the species are so numerous and abundant in Europe, little is known as to their metamorphoses. Some of the larvae frequent trees, living under the bark or in the overflowing sap, and are believed to be carnivorous; they are amphipneustic; a cocoon is formed, and the pupa is remarkable on account of the existence of two long horns, bearing the spiracles, on the back of the thorax; the seven pairs of abdominal spiracles being excessively minute.[416]

Fig 236 Wing of Trineura aterrima, one of the Phoridae Britain

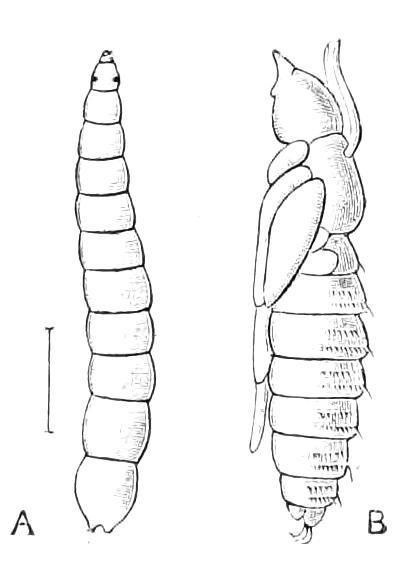

Series 3. Cyclorrhapha Aschiza

Fam. 28. Phoridae. Small flies, with very convex thorax, small head, very small two-jointed antennae, bearing a long seta; femora more or less broad; wings with two dark, thick, approximate veins, meeting on the front margin near its middle, and besides these, three or four very fine veins, that run to the margins in a sub-parallel manner without forming any cells or forks. This obscure family of flies is of small extent, but its members are extremely common in Europe and North America, where they often occur in numbers running on the windows of houses. It is one of the most isolated groups of Diptera, and great difference of opinion prevails as to its classification. The wing-nervuration is peculiar (but varies somewhat in the species), the total absence of any cross-veins even on the basal part of the wing being remarkable. There are bristles on the head and thorax, but they are not arranged in a regular manner. The larvae live in a great variety of animal and vegetable decaying matter, and attack living Insects, and even snails, though probably only when these are in a sickly or diseased condition. The metamorphoses of several species have been described.[417] The larvae are rather slender, but sub-conical in form, with eleven segments and a very small head, amphipneustic, the body behind terminated by some pointed processes. The pupa is remarkable; it is contained in a case formed by the contracted and hardened skin of the larva; though it differs much in form from the larva the segmentation is distinct, and from the fourth segment there project two slender processes. These are breathing organs, attached to the prothorax of the imprisoned pupa; in what manner they effect a passage through the hardened larval skin is by no means clear. Perris supposes that holes for them pre-exist in the larval skin, and that the newly-formed pupa by restless movements succeeds in bringing the processes into such a position that they can pass

through the holes. The dehiscence of the puparium seems to occur in a somewhat irregular manner, as in Microdon; it is never Cyclorrhaphous, and according to Perris is occasionally Orthorrhaphous; probably there is no ptilinum.

Fig. 237 Aenigmatias blattoides. × 27. Denmark. (After Meinert.)

The Insect recently described by Meinert as Aenigmatias blattoides, [418] is so anomalous, and so little is known about it, that it cannot at present be classified. It is completely apterous; the arrangement of the body-segments is unlike that of Diptera, but the antennae and mouth-parts are said to be like those of Phoridae. The Insect was found near Copenhagen under a stone in the runs of Formica fusca. Meinert thinks it possible that the discovery of the male may prove Aenigmatias to be really allied to Phoridae, and Mik suggests that it may be the same as Platyphora lubbocki, Verrall, known to be parasitic on ants. Dahl recently described a wingless Dipteron, found living as a parasite on land-snails in the Bismarck archipelago, under the name of Puliciphora lucifera, and Wandolleck has recently made for this and some allies the new family Stethopathidae. It seems doubtful whether these forms are more than wingless Phoridae.

Fam. 29. Platypezidae.—Small flies, with porrect three-jointed antennae, first two joints short, third longer, with a terminal seta; no bristles on the back; hind legs of male, or of both sexes, with peculiar, broad, flat tarsi; the middle tibiae bear spurs; there is no empodium. Platypezidae is a small family of flies, the classification of which has always been a matter of considerable difficulty, and is still uncertain. The larvae are broad and flat, fringed at the margin with twenty-six spines; they live between the lamellae of Agaric fungi. At pupation the form alters but little; the imago emerges by a horizontal

cleft occurring at the margins of segments two and four.[419] We have four genera (Opetia, Platycnema, Platypeza, Callomyia), and nearly a score of species of Platypezidae in our British list, but very little seems to be known about them. There is much difference in the eyes of the sexes, in some at any rate of the species, they being large and contiguous in the male, but widely separated in the female.

Fig 238 Head of Pipunculus sp A, Seen from in front; B, side view, showing an antenna magnified Pyrenees

Fam. 30. Pipunculidae.[420] Small flies, with very short antennae bearing a long seta that is not terminal; head almost globular, formed, except at the back, almost entirely by the large conjoined eyes; the head is only slightly smaller in the female, but in the male the eyes are more approximate at the top. This is another of the small families of flies, that seems distinct from any other, though possessing no very important characters. In many of the flies that have very large eyes, the head is either flattened (i.e. compressed from before backwards, as in Tabanidae, Asilidae), or forced beneath the humped thorax (as in Acroceridae), but neither of these conditions exists in Pipunculus; in them the head extends far forwards, so that the area of the eye compared with the size of the body is perhaps greater than in any other Diptera. The general form is somewhat that of Anthrax, but the venation on the hind part of the wing is much less complex. There is a remarkable difference between the facets on the front and the back of these great eyes. We have three genera and about a dozen species of Pipunculidae in Britain but apparently they are far from common Insects. What is known about the life-history is almost confined to an imperfect observation by Boheman, who found the larva of P. fuscipes living after the manner of a Hymenopterous parasite in the body of a small Homopterous Insect.[421] The pupa seems to be of the type of that of Syrphidae.

Fam. 31. Conopidae. Elegant flies of moderate size, of varied colours, with abdomen slender at the base, at the tip strongly incurved and thicker; antennae inserted close together on a prominence, three-jointed, first joint sometimes very short. The upper surface of the body without bristles or with but few. There is a slender, elongate proboscis, which is retractile and usually invisible. This rather small family of flies includes some of the most remarkable forms of Diptera; it includes two divisions, the Conopinae with long antennae terminated by a very minute pointed process, and Myopinae with shorter antennae bearing a hair that is not placed at the end of the third joint. The former are the more wasp-like and elegant; the Myopinae being much more like ordinary flies, though they frequently have curious, inflated heads, with a white face. The mode of life of the larva of Conops is peculiar, it being parasitic in the interior of Bombus, or other Hymenoptera. They have been found to attack Bombus, Chalicodoma, Osmia, Vespa, Pompilus, and other Aculeates. Williston says that Orthoptera are also attacked. Conops has been seen to follow Bumble-bees and alight on them, and Williston says this act is accompanied by oviposition, the larva that is hatched boring its way into the body of the bee. Others have supposed that the flies enter the bees' nests and place their eggs in the larvae or pupae; but this is uncertain, for Conops has never been reared from a bee-larva or pupa, though it has frequently been procured from the imago: cases indeed having been recorded in which Conops has emerged from the body of a Bombus several months after the latter had been killed and placed in an entomologist's collection. The larva is broad, and when full grown apparently occupies nearly all the space of the interior of the abdomen of the bee; it has very peculiar terminal stigmata. The pupa is formed in the larval skin, which is greatly shortened and indurated for the purpose; this instar bears, in addition to the posterior stigmata, a pair of slightly projecting, anterior stigmata. We have several species of Conopidae in Britain; those belonging to the division Conopinae are all rare Insects, but the Myopinae are not so scarce; these latter are believed to be of similar habits with the Conopinae, though remarkably little is known about them. This is another of the numerous families, the relations of which are still a

subject for elucidation. Brauer places the Conopidae in his section Schizophora away from Syrphidae, but we do not comprehend on what grounds; an inspection of the head shows that there is no frontal lunule as there is in Eumyiidae; both Myopa and Conops agreeing fairly well with Syrphus as to this. We therefore place the family in its old position near Syrphus till the relations with Acalypterate Muscidae shall be better established.

Fam. 32. Syrphidae (Hover-flies).—Of moderate or rather large size, frequently spotted or banded with yellow, with a thick fleshy proboscis capable of being withdrawn into a cleft on the under side of the head; antennae not placed in definite cavities, three-jointed (usually very short), and leaving a seta that is not terminal in position, and may be feathered. Squama variable, never entirely covering the halteres; the chief (third to fifth) longitudinal veins of the wings connected near their termination by cross-veins and usually thus forming a sort of short margin parallel with the hind edge of the wing; a more or less imperfect false nervure running between the third and fourth longitudinal nervures; no empodium and generally no distinct system of bristles on the back of the body. The Syrphidae (Fig. 212) form one of the largest and best known of all the families of flies; they abound in our gardens where, in sunny weather, some species may be nearly always seen hovering over flowers, or beneath trees in places where the rays of the sun penetrate amidst the shade. There are two or three thousand species known, so that of course much variety exists; some are densely covered with hair (certain Volucella and others), many are of elegant form, and some bear a considerable resemblance to Hymenoptera of various groups. The peculiar veining of the wings permits of their easy identification, the line of two nervules, approximately parallel with the margin of the distal part of the wing (Fig. 212, D), and followed by a deep bay, being eminently characteristic, though there are some exceptions; there are a few forms in which the antennae are exceptional in having a terminal pointed process. The proboscis, besides the membranous and fleshy lips, consists of a series of pointed slender lancets, the use of which it is difficult to comprehend, as the Insects are not known to pierce either animals or vegetables, their food

being chiefly pollen; honey is also doubtless taken by some species, but the lancet-like organs appear equally ill-adapted for dealing with it. The larvae are singularly diversified; first, there are the eaters of Aphidae, or green-fly; some of these may be generally found on our rose-bushes or on thistles, when they are much covered with Aphids; they are soft, maggot-like creatures with a great capacity for changing their shape and with much power of movement, especially of the anterior part of the body, which is stretched out and moved about to obtain and spear their prey: some of them are very transparent, so that the movements of the internal organs and their vivid colours can readily be seen: like so many other carnivorous Insects, their voracity appears to be insatiable. The larvae of many of the ordinary Hover-flies are of this kind. Eristalis and its allies are totally different, they live in water saturated with filth, or with decaying vegetable matter (the writer has found many hundreds of the larvae of Myiatropa florea in a pool of water standing in a hollow beech-tree). These rat-tailed maggots are of great interest, but as they have been described in almost every work on entomology, and as Professor Miall[422] has recently given an excellent account of their peculiarities, we need not now discuss them. Some of the flies of the genus Eristalis are very like honey-bees, and appear in old times to have been confounded with them; indeed, Osten Sacken thinks this resemblance gave rise to the "Bugonia myth," a fable of very ancient origin to the effect that Honey-bees could be procured from filth, or even putrefying carcases, by the aid of certain proceedings that savoured slightly of witchcraft, and may therefore have increased the belief of the operator in the possibility of a favourable result. It was certainly not bees that were produced from the carcases, but Osten Sacken suggests that Eristalis-flies may have been bred therein.

In the genus Volucella we meet with a third kind of Syrphid larva. These larvae are pallid, broad and fleshy, surrounded by numerous angular, somewhat spinose, outgrowths of the body; and have behind a pair of combined stigmata, in the neighbourhood of which the outgrowths are somewhat larger; these larvae live in the nests of Bees and Wasps, in which they are abundant. Some of the

Volucella, like many other Syrphidae, bear a considerable resemblance to Bees or Wasps, and this has given rise to a modern fable about them that appears to have no more legitimate basis of fact than the ancient Bees-born-of-carcases myth. It was formerly assumed that the Volucella-larvae lived on the larvae of the Bees, and that the parent flies were providentially endowed with a bee-like appearance that they might obtain entrance into the Bees' nests without being detected, and then carry out their nefarious intention of laying eggs that would hatch into larvae and subsequently destroy the larvae of the Bees. Some hard-hearted critic remarked that it was easy to understand that providence should display so great a solicitude for the welfare of the Volucella, but that it was difficult to comprehend how it could be, at the same time, so totally indifferent to the welfare of the Bees. More recently the tale has been revived and cited as an instance of the value of deceptive resemblance resulting from the action of natural selection, without reference to providence. There are, however, no facts to support any theory on the subject. Very little indeed is actually known as to the habits of Volucella in either the larval or imaginal instars; but the little that is known tends to the view that the presence of the Volucella in the nests is advantageous to both Fly and Bee. Nicolas has seen Volucella zonaria enter the nest of a Wasp; it settled at a little distance and walked in without any fuss being made. Erné has watched the Volucella-larvae in the nests, and he thinks that they eat the waste or dejections of the larvae. The writer kept under observation Volucella-larvae and portions of the cells of Bombus, containing some larvae and pupae of the Bees and some honey, but the fly-larvae did not during some weeks touch any of the Bees or honey, and ultimately died, presumably of starvation. Subsequently, he experimented with Volucella-larvae and a portion of the comb of wasps containing pupae, and again found that the flies did not attack the Hymenoptera; but on breaking a pupa of the Wasp in two, the flylarvae attacked it immediately and eagerly; so that the evidence goes to show that the Volucella-larvae act as scavengers in the nests of the Hymenoptera. Künckel d'Herculais has published an elaborate work on the European Volucella; it is remarkable for the beauty of the plates illustrating the structure, anatomy and

development, but throws little direct light on the natural history of the Insects. V. bombylans, one of the most abundant of our British species, appears in two forms, each of which has a considerable resemblance to a Bombus, and it has been supposed that each of the two forms is specially connected with the Bee it resembles, but there is no evidence to support this idea; indeed, there is some little evidence to the contrary. The genus Merodon has larvae somewhat similar to those of Volucella, but they live in bulbs of Narcissus; M. equestris has been the cause of much loss to the growers of Dutch bulbs; this Fly is interesting on account of its great variation in colour; it has been described as a whole series of distinct species.

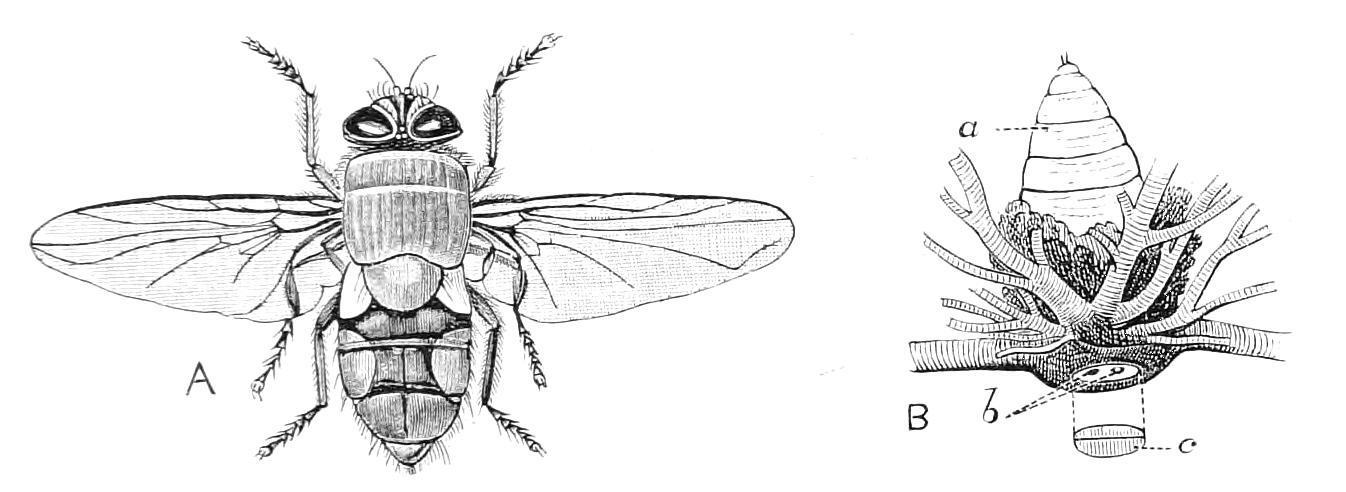

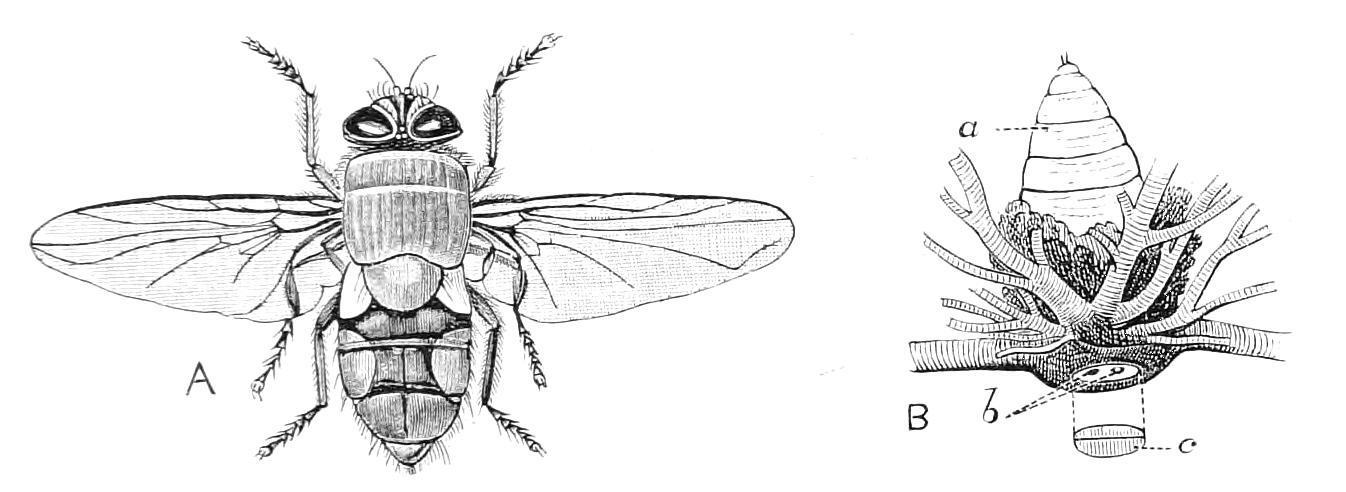

The most remarkable of the numerous forms of Syrphid larvae are those of the genus Microdon (Fig. 239), which live in ants' nests. They have no resemblance to Insect-larvae, and when first discovered were not only supposed to be little Molluscs, but were actually described as such under the generic names of Parmula and Scutelligera. There is no appearance of segmentation of the body; the upper surface is covered by a sort of network formed by curved setae, which help to retain a coating of dirt; there is no trace externally of any head, but on the under surface there is a minute fold in which such mouth-organs as may be present are probably concealed; the sides of the body project so as to form a complex fringing arrangement; the terminal stigmata are very distinct, the lateral processes connected with them (the "Knospen" of Dr. Meijere), are, however, very irregular and placed at some distance from the stigmatic scar. Pupation occurs by the induration of the external covering and the growth from it, or rather through it, of two short horns in front. Inside this skin there is formed a soft pupa, of the kind usual in Cyclorrhaphous flies; the dehiscence of the external covering is, however, of unusual nature, three little pieces being separated from the anterior part of the upper surface, while the lower face remains intact. The account of the pupation given by Elditt[423] is not complete: the two horns that project are, it would appear, not portions of the larval skin, but belong to the head of the pupa, and according to Elditt are used to effect the dehiscence of the case for the escape of the fly; there does not appear to be any head-vesicle.

Nothing is known as to the details of the life of these anomalous larvae. M. Poujade has described two species found in France in the nests of the ant Lasius niger. [424] The larva we figure was found by Colonel Yerbury in nests of an Atta in Portugal, and an almost identical larva was recently found by Mr. Budgett in Paraguay. The flies themselves are scarce, Microdon mutabilis (formerly called M. apiformis) being one of the rarest of British flies. They have the antennae longer than is usual in Syrphidae, and the cross-veins at the outside of the wing are irregularly placed, so that the contour is very irregular: the resemblance to bees is very marked, and in some of the South American forms the hind legs are flattened and hairy like those of bees. The oviposition of Microdon has been observed by Verhoeff;[425] he noticed that the fly was frequently driven away by the ants—in this case, Formica sanguinea—but returned undiscouraged to its task.

Fig. 239 Larva of Microdon sp. Portugal. A, Dorsal view of the larva, × 4; 1, the stigmatic structure; B, posterior view of stigmatic structure; C, a portion of the marginal fringe of the body.

A brief résumé of the diverse modes of life of Syrphid larvae has been given by Perris,[426] and he also gives some information as to the curious horns of the pupae, but this latter point much wants elucidation. Whether the Syrphidae, or some of them, possess a ptilinum that helps them to emerge from the pupa is more than doubtful, though its existence has been affirmed by several authors of good repute.[427]

Fig. 240. Diopsis apicalis. Natal. A, The fly; B, extremity of cephalic protuberance, more magnified. a, The eye; b, the antenna; C, middle of head, front view; c, ocelli.

Series 4. Cyclorrhapha Schizophora

Fam. 33. Muscidae acalyptratae.—This group of flies has been the least studied of all the Diptera; it is generally treated as composed of twenty or thirty different families distinguished by very slight characters. It is, however, generally admitted by systematists that these assemblages have not the value of the families of the other divisions of Diptera, and some even go so far as to say that they are altogether only equivalent to a single family. We do not therefore think it necessary to define each one seriatim; we shall merely mention their names, and allude to certain points of interest connected with them. Taken collectively they may be defined as very small flies, with three-jointed antennae (frequently looking as if only two-jointed), bearing a bristle that is not terminally placed; frequently either destitute of squamae or having these imperfectly developed so as not to cover the halteres; and possessing a comparatively simple system of nervuration, the chief nervures being nearly straight, so that consequently few cells are formed. These characters will distinguish the group from all the other Diptera except from forms of Aschiza, and from certain Anthomyiidae, with both of which the Acalyptratae are really intimately connected. Considerable difference of opinion prevails as to the number of these divisions, but the families usually recognised are:—

1. Doryceridae.

2. Tetanoceridae.

3. Sciomyzidae.

4. Diopsidae.

5. Celyphidae.

6. Sepsidae incl. Piophilidae.

7. Chloropidae (= Oscinidae).

8. Ulidiidae.

9. Platystomidae.

10. Ephydridae.

11. Helomyzidae.

12. Dryomyzidae.

13. Borboridae.

14. Phycodromidae.

15. Thyreophoridae.

16. Scatophagidae. (= Scatomyzidae).

17. Geomyzidae incl. Opomyzidae.

18. Drosophilidae; incl. Asteidae.

19. Psilidae.

20. Tanypezidae (= Micropezidae).

21. Trypetidae.

22. Sapromyzidae incl. Lonchaeidae.

23. Rhopalomeridae.

24. Ortalidae.

25. Agromyzidae incl. Phytomyzidae.

26. Milichiidae.

27. Octhiphilidae.

28. Heteroneuridae.

29. Cordyluridae.

Brauer associates Conopidae with Acalyptrate Muscids, and calls the Group Holometopa; applying the term Schizometopa to the Calyptrate Muscidae.

No generalisation can yet be made as to the larvae of these divisions, neither can any characters be pointed out by which they can be distinguished from the larvae of the following families. In their

habits they have nothing specially distinctive, and may be said to resemble the Anthomyiidae, vegetable matter being more used as food than animal; many of them mine in the leaves or stems of plants; in the genus Dorycera the larva is aquatic, mining in the leaves of water-plants, and in Ephydridae several kinds of aquatic larvae are found, some of which are said to resemble the rat-tailed larvae of Syrphidae; certain of these larvae occur in prodigious quantities in lakes, and the Insects in some of their early stages serve the Mexicans as food, the eggs being called Ahuatle, the larvae Pusci, the pupae Koo-chah-bee. Some of the larvae of the Sciomyzidae are also aquatic: that of Tetanocera ferruginea is said by Dufour to consist only of eight segments, and to be metapneustic; Brauer considers the Acalyptrate larvae to be, however, in general, amphipneustic, like those of Calyptratae. The Chloropidae are a very important family owing to their occasional excessive multiplication, and to their living on cereals and other grasses, various parts of which they attack, sometimes causing great losses to the agriculturist. The species of the genus Chlorops are famous for the curious habit of entering human habitations in great swarms: frequently many millions being found in a single apartment. Instances of this habit have been recorded both in France and England, Cambridge being perhaps the place where the phenomenon is most persistently exhibited. In the year 1831 an enormous swarm of C. lineata was found in the Provost's Lodge at King's College and was recorded by Leonard Jenyns; in 1870 another swarm occurred in the same house if not in the same room. [428] Of late years such swarms have occurred in certain apartments in the Museums (which are not far from King's College), and always in the same apartments. No clue whatever can be obtained as to their origin; and the manner in which these flies are guided to a small area in numbers that must be seen to be believed, is most mysterious. These swarms always occur in the autumn, and it has been suggested that the individuals are seeking winter quarters.

Fig. 241 Celyphus (Paracelyphus) sp. West Africa. A, The fly seen from above; a, scutellum; b, base of wing: B, profile, with tip of abdomen bent downwards; a, scutellum; b, b, wing; c, part of abdomen.

Several members of the Acalyptratae have small wings or are wingless, as in some of our species of Borborus. The Diopsidae— none of which are European—have the sides of the head produced into long horns, at the extremity of which are placed the eyes and antennae; these curiosities (Fig. 240) are apparently common in both Hindostan and Africa. In the horned flies of the genus Elaphomyia, parts of the head are prolonged into horns of very diverse forms according to the species, but bearing on the whole a great resemblance to miniature stag-horns. A genus (Giraffomyia) with a long neck, and with partially segmented appendages, instead of horns on the head, has been recently discovered by Dr. Arthur Willey in New Britain. Equally remarkable are the species of Celyphus; they do not look like flies at all, owing to the scutellum being inflated and enlarged so as to cover all the posterior parts of the body as in the Scutellerid Hemiptera: the wings are entirely concealed, and the abdomen is reduced to a plate, with its orifice beneath, not terminal; the surface of the body is highly polished and destitute of bristles. Whether this is a mimetic form, occurring in association with similarlooking Bugs is not known. The North American genus Toxotrypana is furnished with a long ovipositor; and in this and in the shape of the body resembles the parasitic Hymenoptera. This genus was placed by Gerstaecker in Ortalidae, but is considered by later writers to be a member of the Trypetidae. This latter family is of considerable extent, and is remarkable amongst the Diptera for the way in which

the wings of many of its members are ornamented by an elaborate system of spots or marks, varying according to the species.

Fam. 34. Anthomyiidae. Flies similar in appearance to the Housefly; the main vein posterior to the middle of the wing (4th longitudinal) continued straight to the margin, not turned upwards. Eyes of the male frequently large and contiguous, bristle of antenna either feathery or bare. This very large family of flies is one of the most difficult and unattractive of the Order. Many of its members come close to the Acalyptrate Muscidae from which they are distinguished by the fact that a well-developed squama covers the halteres; others come quite as close to the Tachinidae, Muscidae and Sarcophagidae, but may readily be separated by the simple, not angulate, main vein of the wing. The larval habits are varied. Many attack vegetables, produce disintegration in them, thus facilitating decomposition. Anthomyia brassicae is renowned amongst market gardeners on account of its destructive habits. A. cana, on the contrary, is beneficial by destroying the migratory Locust Schistocerca peregrina; and in North America, A. angustifrons performs a similar office with Caloptenus spretus. One or two species have been found living in birds; in one case on the head of a species of Spermophila, in another case on a tumour of the wing of a Woodpecker. Hylemyia strigosa, a dung-frequenting species, has the peculiar habit of producing living larvae, one at a time; these larvae are so large that it would be supposed they are full grown, but this is not the case, they are really only in the first stage, an unusual amount of growth being accomplished in this stadium. Spilogaster angelicae, on the other hand, according to Portschinsky, lays a small number of very large eggs, and the resulting larvae pass from the first to the third stage of development, omitting the second stage that is usual in Eumyiid Muscidae.[429]

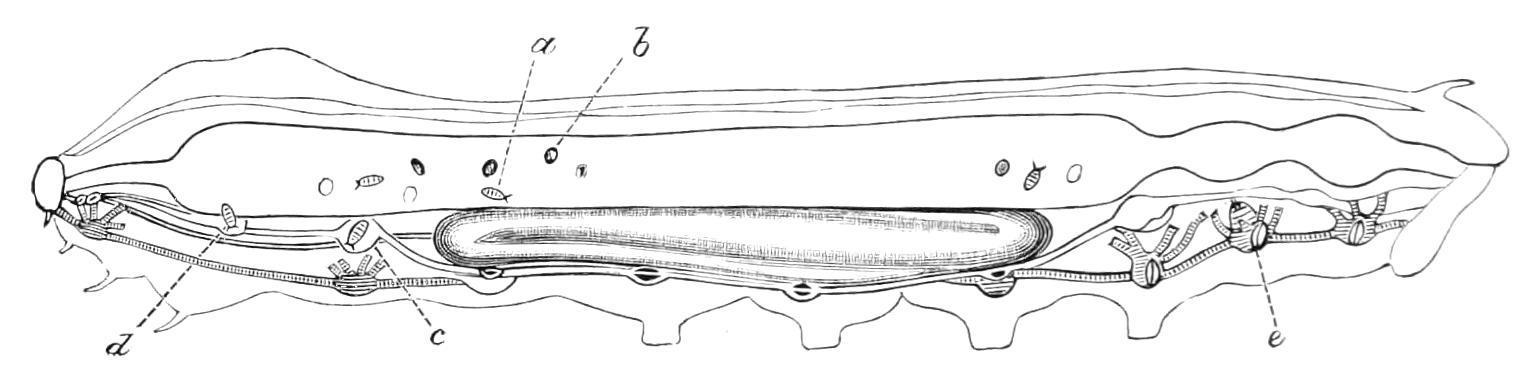

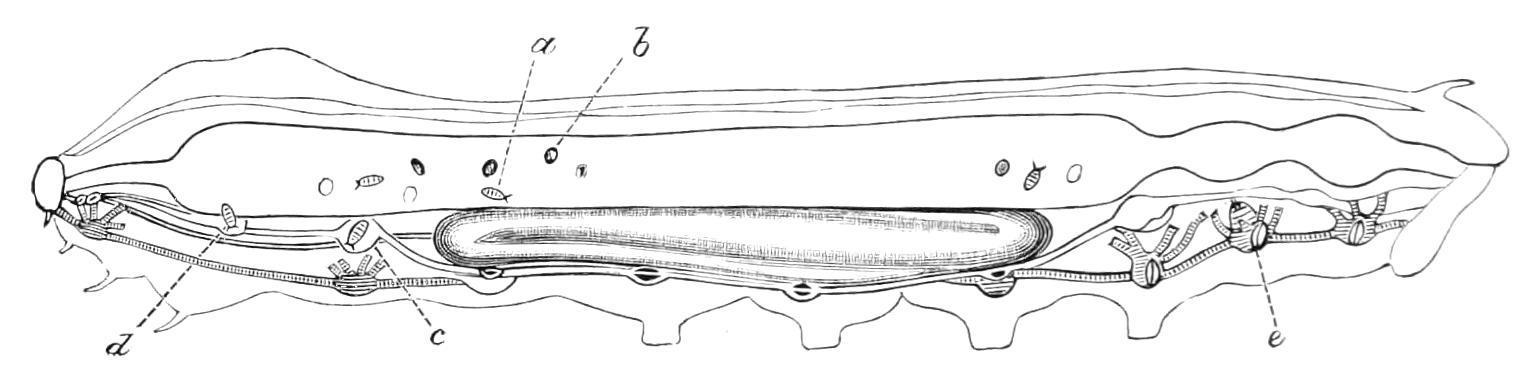

Fig. 242 Ugimyia sericariae. A, The perfect fly, × 3⁄2; B, tracheal chamber of a silkworm, with body of a larva of Ugimyia projecting; a, front part of the maggot; b, stigmatic orifice of the maggot; c, stigma of the silkworm (After Sasaki )

Fam. 35. Tachinidae. First posterior cell of wing nearly or quite closed. Squamae large, covering the halteres: antennal arista bare: upper surface of body usually bristly. This is an enormous family of flies, the larvae of which live parasitically in other living Insects, Lepidopterous larvae being especially haunted. Many have been reared from the Insects in which they live, but beyond this little is known of the life-histories, and still less of the structure of the larvae of the Tachinidae, although these Insects are of the very first importance in the economy of Nature. The eggs are usually deposited by the parent-flies near or on the head of the victim; Riley supposed that the fly buzzes about the victim and deposits an egg with rapidity, but a circumstantial account given by Weeks[430] discloses a very different process: the fly he watched sat on a leaf quietly facing a caterpillar of Datana engaged in feeding at a distance of rather less than a quarter of an inch. "Seizing a moment when the head of the larva was likely to remain stationary, the fly stealthily and rapidly bent her abdomen downward and extended from the last segment what proved to be an ovipositor. This passed forward beneath her body and between the legs until it projected beyond and nearly on a level with the head of the fly and came in contact with the eye of the larva upon which an egg was deposited," making an addition to five already there. Ugimyia sericariae does great harm in Japan by attacking the silkworm, and in the case of this fly the eggs are believed to be introduced into the victim by being laid on mulberry leaves and swallowed with the food; several observers agree as to the eggs being laid on the leaves, but the fact that they are swallowed by the silkworm is not so certain. Sasaki has given an extremely interesting account of the development of this larva.[431] According to him, the young larva, after hatching in the alimentary canal, bores through it, and enters a nerve-ganglion, feeding there for about a week, after which the necessity for air becoming greater, as usual with larvae, the maggot leaves the

nervous system and enters the tracheal system, boring into a tube near a stigmatic orifice of the silkworm, where it forms a chamber for itself by biting portions of the tissues and fastening them together with saliva. In this it completes its growth, feeding on the interior of the silkworm with its anterior part, and breathing through the stigmatic orifice of its host; after this it makes its exit and buries itself deeply in the ground, where it pupates. The work of rupturing the puparium by the use of the ptilinum is fully described by Sasaki, and also the fact that the fly mounts to the surface of the earth by the aid of this same peculiar air-bladder, which is alternately contracted and distended. Five, or more, of the Ugimyia-maggots may be found in one caterpillar, but only one of them reaches maturity, and emerges from the body. The Tachinid flies appear to waste a large proportion of their eggs by injudicious oviposition; but they make up for this by the wide circle of their victims, for a single species has been known to infest Insects of two or three different Orders.

Fig. 243 Diagrammatic section of silkworm to show the habits of Ugimyia. a, Young larva; b, egg of Ugimyia in stomach of the silkworm; c, larva in a nerve-ganglion; d, larva entering a ganglion; e, larva embedded in tracheal chamber, as shown in Fig. 242, B. (After Sasaki.)

The species of Miltogramma—of which there are many in Europe and two in England—live at the expense of Fossorial Hymenoptera by a curious sort of indirect parasitism. They are obscure little flies, somewhat resembling the common House-fly, but they are adepts on the wing and have the art of ovipositing with extreme rapidity; they follow a Hymenopteron as it is carrying the prey to the nest for its young. When the wasp alights on the ground at the entrance to the nest, the Miltogramma swoops down and rapidly deposits one or more eggs on the prey the wasp designs as food for its own young. Afterwards the larvae of the fly eat up the food, and in consequence of the greater rapidity of their growth, the young of the

Hymenopteron perishes. Some of them are said to deposit living larvae, not eggs. Fabre has drawn a very interesting picture of the relations that exist between a species of Miltogramma and a Fossorial Wasp of the genus Bembex[432] . We may remind the reader that this Hymenopteron has not the art of stinging its victims so as to keep them alive, and that it accordingly feeds its young by returning to the nest at proper intervals with a fresh supply of food, instead of provisioning the nest once and for all and then closing it. This Hymenopteron has a habit of catching the largest and most active flies—especially Tabanidae—for the benefit of its young, and it would therefore be supposed that it would be safe from the parasitism of a small and feeble fly. On the contrary, the Miltogramma adapts its tactics to the special case, and is in fact aided in doing so by the wasp itself. As if knowing that the wasp will return to the carefully-closed nest, the Miltogramma waits near it, and quietly selects the favourable moment, when the wasp is turning round to enter the nest backwards, and deposits eggs on the prey. It appears from Fabre's account that the Bembex is well aware of the presence of the fly, and would seem to entertain a great dread of it, as if conscious that it is a formidable enemy; nevertheless the wasp never attacks the little fly, but allows it sooner or later to accomplish its purpose, and will, it appears, even continue to feed the fly-larvae, though they are the certain destroyers of its own young, thus repeating the relations between cuckoo and sparrow. Most of us think the wasp stupid, and find its relations to the fly incredible or contemptible. Fabre takes a contrary view, and looks on it as a superior Uncle Toby. We sympathise with the charming French naturalist, without forming an opinion.

Doubtless there are many other interesting features to be found in the life-histories of Tachinidae, for in numbers they are legion. It is probable that we may have 200 species in Britain, and in other parts of the world they are even more abundant, about 1000 species being known in North America.[433] The family Actiidae is at present somewhat doubtful. According to Karsch,[434] it is a sub-family of Tachinidae; but the fourth longitudinal vein, it appears, is straight.

Fam. 36. Dexiidae. These Insects are distinguished from Tachinidae by the bristle of the antennae being pubescent, and the legs usually longer. The larvae, so far as known, are found in various Insects, especially in Coleoptera, and have also been found in snails. There are eleven British genera, and about a score of species.