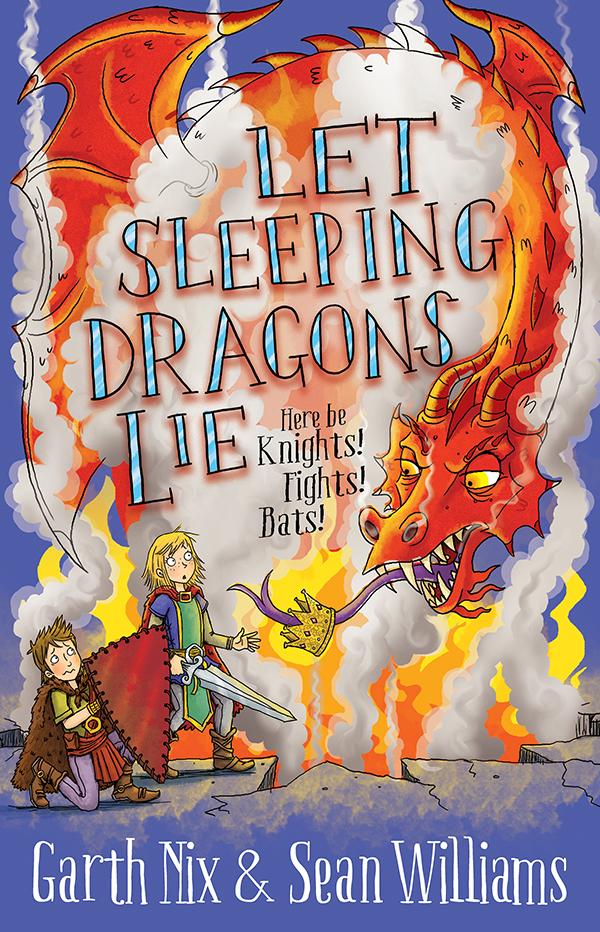

Travel 2 Williams Garth - Nix Sean

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/let-sleeping-dragons-lie-have-sword-will-travel-2-willia ms-garth-nix-sean/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Have dog will travel a poet s journey First Simon & Schuster Hardcover Edition Kuusisto

https://textbookfull.com/product/have-dog-will-travel-a-poet-sjourney-first-simon-schuster-hardcover-edition-kuusisto/

Williams Basic Nutrition Diet Therapy 15th Edition Staci Nix Mcintosh

https://textbookfull.com/product/williams-basic-nutrition-diettherapy-15th-edition-staci-nix-mcintosh/

Predictive Analytics The Power to Predict Who Will Click Buy Lie or Die 2 Revised and updated Edition Eric Siegel

https://textbookfull.com/product/predictive-analytics-the-powerto-predict-who-will-click-buy-lie-or-die-2-revised-and-updatededition-eric-siegel/

Let s Talk About Love Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste Carl Wilson

https://textbookfull.com/product/let-s-talk-about-love-why-otherpeople-have-such-bad-taste-carl-wilson/

Predictive analytics the power to predict who will click buy lie or die Siegel

https://textbookfull.com/product/predictive-analytics-the-powerto-predict-who-will-click-buy-lie-or-die-siegel/

High Stakes: An Urban Fantasy Adventure (Sword & Sassery Book 2) 1st Edition Phoebe Ravencraft [Ravencraft

https://textbookfull.com/product/high-stakes-an-urban-fantasyadventure-sword-sassery-book-2-1st-edition-phoebe-ravencraftravencraft/

Predictive Analytics The Power to Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie, or Die, Revised and Updated Siegel

https://textbookfull.com/product/predictive-analytics-the-powerto-predict-who-will-click-buy-lie-or-die-revised-and-updatedsiegel/

Have Mercy (Vengeance is Mine #2) 1st Edition Ashley Gee

https://textbookfull.com/product/have-mercy-vengeance-ismine-2-1st-edition-ashley-gee/

Europe Travel Guide 2017 2 edition Edition Averbuck

https://textbookfull.com/product/europe-travelguide-2017-2-edition-edition-averbuck/

First published by Allen & Unwin in 2018

Copyright © Garth Nix & Sean Williams 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 74343 993 7

eBook ISBN 978 1 76087 003 4

For teaching resources, explore www.allenandunwin.com/resources/for-teachers

Cover illustration copyright © 2018 by Cherie Zamazing

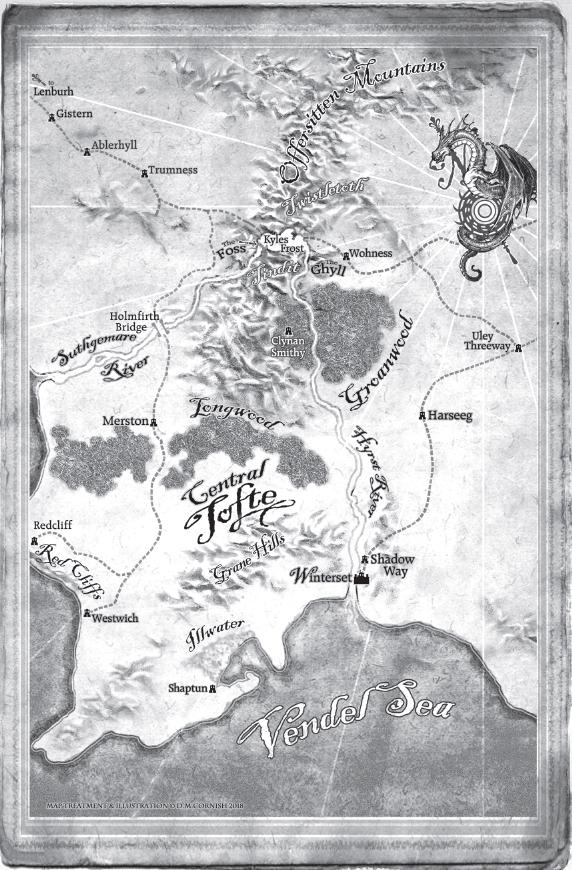

Map copyright © 2018 by D.M. Cornish

Cover design by Nick Stern

Text design by Ian Butterworth

ToAnna,Thomas,Edward,andallmyfamilyandfriends.

— GarthNix

To Amanda, andallour friends andfamily, with gratitude andlove.

— Sean Williams

MAP

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

EPILOGUE

ALSO BY THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

‘Bilewolves!’

‘Help us!’

‘Help me!’

‘Aarrgh, no, no—’

The shouts and screams grew louder as Sir Odo and Sir Eleanor raced towards the village green, their magical, self-willed swords, Biter and Runnel, almost lifting them from the ground in their own eagerness to join the combat. Well behind them came Addyson and Aaric, the baker’s twin boys, who had come in a panic to tell them the village was under attack.

Above all the human sounds of fear and fighting, a terrible howling came again, from more than one bestial throat.

‘Slower!’ panted Odo as they reached the back of the village inn, the Sign of the Silver Fleece, or the Grey Sheep, as it was nicknamed, since the sign had long since faded. ‘We must be clever. Stay shoulder to shoulder, advance with care.’

‘Nay, we must charge at once!’ roared Biter, even as his sister sword snapped, ‘I agree, Sir Odo.’

‘I do too,’ said Eleanor, slowing so her much larger and less fleetof-foot friend could catch up. When he was level with her, she moved closer so they were indeed shoulder to shoulder, their swords held in the guard position.

Together, and ready, they rounded the corner of the inn.

A terrible scene met their eyes. Some forty paces away, four enormous, shaggy, wolflike creatures, each the size of a small horse,

stood at bay opposite a man and a woman. The people were hunters or trappers, judging by their leather armour and well-travelled boots, although they were quite old to be in that trade. Both looked to be at least fifty.

The man had a cloth of shining gold tied around his eyes, which perhaps explained Addyson’s panicked description of ‘a blind king’ being attacked by the bilewolves. The cloth didgive the impression of a crown.

Blind or not, king or not, the man wielded his steel-shod staff with a brilliance that made Odo gasp. The weapon was a blur, leaping out to punch one bilewolf’s snout, then jab another’s forefoot. The woman was equally adept, though she wielded a curved sword, the blade moving swiftly and smoothly as she danced with it, the bilewolves slow and clumsy partners. Close to the inn on the edge of the green, three villagers lay dead or seriously wounded, their torn and jagged clothes still smoking from the bilewolves’ acid-spewing jaws. Eleanor’s father, the herbalist Symon, was bent over the closest victim, frantically trying to stem the flow of blood from a wound. He looked up for a second at his daughter, but did not speak, turning instantly back to his work.

Odo grasped the situation immediately. Only the two old warriors kept the bilewolves away from the wounded and the rest of the defenceless villagers. But the two were outnumbered and, despite their skill, overmatched by the sheer size and ferocity of the animals.

‘Forward!’ Odo shouted, and he and Eleanor marched together.

‘For Lenburh!’ shouted Eleanor.

Odo knew from the slightest tremor in Eleanor’s voice that she was afraid, though no one else would be able to tell. He was afraid as well. They were only twelve years old and had been knights for little over a month, but he knew the fear would not stop Eleanor, and it wouldn’t stop him either.

They did not expect their war cries to be answered, but off to the right came a shout: ‘Forward for Lenburh!’ A horse came galloping across the green, the ancient warhorse of Sir Halfdan, who, like the master who rode it, had not been in battle for twenty years or more. True to its training, the warhorse held straight for the bilewolves,

despite their terrible stench and formidable snarls. Sir Halfdan, despite age and infirmity, was rock-solid in the saddle, a lance couched under his arm. He had not had time to put on any armour save his helmet and a gauntlet. He still wore the nightgown that was his usual garb these days, and his one foot was still clad in a velvet slipper.

A bilewolf turned towards the galloping horse and charged, leaping at the last moment to avoid Sir Halfdan’s lowering lance. But the old knight knew that trick and flicked the point up, taking the beast in the shoulder, the steel point punching deep. Bilewolf shrieked, the lance snapped, and then horse, knight, and dying bilewolf collided and went flying.

At the same time, one of the three remaining bilewolves bounded up on the back of one of its fellows and leaped high over the head of the blind staff-wielder. The man jumped upon his companion’s shoulders and punched up at the bilewolf’s belly, but the beast had launched itself too well. The staff merely struck its wiry tail, severing it midway along as the bilewolf flew past them.

Odo and Eleanor rushed across the green, expecting the falling bilewolf to attack them and the unprotected villagers behind. But it ignored them, spinning about as it landed to strike at the two warriors once again, dark blood spraying from its injured tail. The blind man jumped down with the deftness of a travelling acrobat and stood back-to-back with the woman. Together they turned in a circle, staff and sword blurring to hold the bilewolves at bay.

Odo slowed and edged cautiously closer, wondering how the blindfolded man had struck so precisely with his staff. Meanwhile, Eleanor narrowed her eyes, seeking a way into the battle.

‘Take the one to my right!’ shouted the swordswoman to Odo and Eleanor, her voice strong and well used to command. ‘It is already lamed!’

‘Sixth and Fourth Stance!’ said Eleanor. ‘You high, me low.’

They moved in perfect synchrony, as they’d practised, Odo stepping left and out, Biter held above his head to strike in a slanting downwards blow, as Eleanor stretched out low with a lunge at the bilewolf ’s right front leg, which it already favoured.

The bilewolf bunched itself to leap up at Odo, choosing the bigger target. But Runnel’s sharp point cut through its leg even as it sprang. It fell sideways, yelping, and Biter came down to separate its massive head from its body, the sword twisting to avoid a spray of bile from the snapping jaws. Both young knights struck again to be sure it was dead, and then swung about to move to the next target.

But the remaining two bilewolves were already slain, one with a crushed skull and the other with a sliced-open throat. All four carcasses lay steaming, the grass beneath them turning black and smoking where the acidic drops fell from their jaws.

‘Sir Halfdan!’ cried Eleanor. The old knight lay motionless upon the ground, the haft of his broken lance still couched under his arm. His warhorse lay near him, unable to get up. It raised its head and whinnied, as if in answer to some trumpet no one else could hear, but the effort was too much. Its head fell heavily back and did not move again.

‘Wait!’ Odo called as Eleanor started towards the old knight. ‘Do you see any more bilewolves?’

The swordswoman answered him. She and the man still stood back-to-back, their weapons ready, as if they expected another attack at any moment.

Or they didn’t trust Odo and Eleanor.

‘There will be none,’ she said. ‘They hunt in fours and are jealous of their prey. You are knights of the realm?’

‘Uh, we’re knights, but not … exactly of the realm, I don’t think,’ said Odo. ‘I am Sir Odo.’

‘And I, Sir Eleanor.’ It gave her a small thrill to say that, although there were more pressing matters to consider. ‘If there are no more bilewolves, we must help Sir Halfdan while my father attends to the others—’

‘One moment, Sir Eleanor,’ snapped the woman. ‘How are you knights, but notexactlyoftherealm?’

‘It’s a long story,’ said Odo. ‘We were knighted by the dragon Quenwulf—’

‘Quenwulf?’ asked the woman. Her expression shifted to one minutely more relaxed. ‘Was it she who gifted you with the

enchanted swords you bear?’

‘No!’ said Biter. He was still not entirely convinced he shouldn’t be a dragonslaying sword.

‘Uh, no,’ said Odo. ‘We found them. Like I said, it is a long story—’

‘Best saved for later,’ said the blind man. His voice was even more used to command than the woman’s. ‘Take me to the fallen knight, Hundred. Sir Eleanor, did you say he was Sir Halfdan?’

‘Yes, Sir Halfdan holds the manor here,’ Eleanor told the man as she studied the woman more closely. Hundredwas a very strange name, but perhaps it was apt for a very strange person. In addition to the curved sword she still held at the ready, Eleanor noticed she had a series of small knives sheathed along each forearm, and unusual pouches on her belt. The backs of her dark-skinned hands were white with dozens of scars, like Eleanor’s mother’s hands – not wounds from claws or teeth, but weapon marks. A sign of many years of combat and practice.

‘Sir, we should go on at once,’ protested Hundred. ‘No,’ said the man. He turned to face where Sir Halfdan lay and began to walk towards him, using his staff to tap the ground. After a moment, Hundred went ahead of him, and the man stopped tapping and followed her footfalls.

‘He must have amazing hearing,’ whispered Eleanor to Odo.

‘I have well-trainedears,’ said the man without turning his head.

Odo and Eleanor exchanged glances, then hurried after the odd duo.

Sir Halfdan lay on his back, not moving. His helmet, too big for him, had tipped forward over his face. Hundred knelt by his side and gently removed it. The old knight’s eyes opened as she did so, surprising everyone, for he had seemed already dead.

‘Sir Halfdan,’ said the blind man, bending over him. Sir Halfdan blinked rheumily, and his jaw fell. ‘Sire,’ he whispered. ‘Can it be?’

The old knight tried to lift his head and arm, but could not do so. The blind man knelt by him and closed his own hand over Halfdan’s gauntlet.

‘I remember when you held the bridge at Holmfirth,’ said the blind man. ‘In the second year of my reign. None so brave as Sir Halfdan.

You remember the song Veran wrote? She will have to write another verse.’

‘That was long ago,’ whispered Halfdan.

‘Time has no dominion over the brave.’

‘I thought … we thought you dead, sire.’

Eleanor mouthed ‘sire’ at Odo and hitched one shoulder in question. He shrugged, unable to explain what was going on. But looking at the blind man in profile, there was something familiar about the shape of his face, that beaky nose, the set chin.

‘I gave up the throne,’ said the man. He touched his golden blindfold. ‘When I lost my sight, I thought I could no longer rule. I was wrong. Blindness makes a man a fool no more than a crown makes him king.’

At the word king, Odo suddenly remembered why the old man’s profile looked familiar.

It was on the old silver pennies he counted at the mill.

Eleanor had the same realisation. They both sank together to the earth, their hauberks jangling. Odo went down on his right knee and Eleanor on her left. They looked at each other worriedly and started to spring up again to change knees, before Hundred glared at them and made a sign to be still.

‘My time is done, sire,’ said Sir Halfdan. There was a rattle in his voice. He glanced over at his horse. ‘Old Thunderer has gone ahead, and I must follow …’

He paused for a moment, the effort of gathering his thoughts, of speaking, evident on his face.

‘I commend to you, sire … two most brave knights … Sir Eleanor and Sir Odo. They—’

Whatever he was going to say next was lost. At that moment old Sir Halfdan died. Egda the First – for the blind man was certainly the former king of Tofte, who had abdicated ten years ago – gripped Sir Halfdan’s shoulder in farewell and stood up, turning towards the kneeling Odo and Eleanor.

‘He was a great and noble knight,’ he said. ‘The Hero of Holmfirth Bridge, and even then he must have been over forty. To think of him slaying a bilewolf at the age of ninety!’

‘We didn’t know he was a hero,’ said Eleanor uncomfortably. She was thinking about some of the names she had called him because he was slow getting organised for their journey east, to be introduced to the royal court. And how some people in the village had mocked him behind his back for having only one foot, though they would never dare do so to his face. ‘He was just our knight. He’s been here so long … um … sorry, should I say “sire”, or is it “Your Highness”?’

‘I am not a king,’ said the blind man. ‘I have been simply Egda these last ten years.’

‘SirEgda,’ said Hundred sharply. ‘You may refer to his grace as “sir” or “sire”.’

‘Now, now, Hundred,’ said Egda. He smiled faintly, exposing two rows of white, even teeth. ‘Hundred was the captain of my guard and has certain ideas about maintaining my former station. I wish to hear how you were made knights by the dragon Quenwulf, but first there is work to be done. The bilewolves must be burned. Are the wounded villagers attended to? I hear pain, but also gentle soothing.’

Eleanor looked over to where the wounded were now being lifted to be carried inside the inn. Her father was assisted by several other villagers, including the midwife Rowena, who often worked with him.

‘They are being tended to by my father, who is a healer and herbalist, sir,’ she said.

‘I’ll gather wood to burn the bilewolves,’ said Odo. ‘Addyson and Aaric can help, if it please you, sir.’

‘I do not command here,’ said Egda mildly. ‘Who is Sir Halfdan’s heir? Has he a daughter or son to take up his lands and sword? Or, given his age, grandchildren, perhaps?’

‘There’s no one,’ said Eleanor, frowning. She looked across at where the wounded or dead were being taken into the inn. ‘Only his squire, Bordan, and I think he was one of the three other people the bilewolves—’

‘They sought to help us,’ said Egda. ‘Would that they were less brave.’

‘I warned them away,’ said Hundred harshly. ‘If they had kept back, they would have been in no danger.’

‘Only if the bilewolves were after you in particular,’ said Odo, made curious by her comment.

‘This is not a matter for you, boy,’ said Hundred. ‘Sire, we must be on our—’

‘No,’ interrupted the former king. He didn’t seem happy with the way Hundred was addressing Odo’s inquiries. ‘We will rest here tonight, not camp in the wilds. Sir Halfdan was my father’s knight before he served me. We must show proper respect, see him put to rest. Also, I want to hear the story of these two swords – who are strangely quiet now, though I heard them in the battle.’

‘I merely wait for my knight to introduce me, sir,’ said Biter. He sounded aggrieved. ‘He is new to his estate and I am still teaching him manners.’

‘Oh,’ said Odo. He held up Biter, hilt first. ‘This is Hildebrand Shining Foebiter. Often called Biter.’

‘And my sword is Reynfrida Sharp-point Flamecutter, or Runnel for short,’ said Eleanor.

‘Greetings, sir,’ said Runnel.

‘And welcome, sire,’ added Biter, not wanting to be left out.

Egda nodded. ‘Well then. Sir Odo, to the burning of the beasts. Sir Eleanor, if you would introduce me to your father and other notables in the village, we must order … that is, suggestthe arrangements to lay Sir Halfdan to rest. Hundred, cast about for any sign of other unfriendly beasts.’

‘Sire!’ protested Hundred. ‘I cannot leave you unprotected.’

‘Sir Eleanor, would you give me your arm?’ asked Egda. ‘Sir Odo, would you take care to listen and come should I call for aid?’

‘Yes, sir!’ said Odo and Eleanor together.

‘You see,’ said Egda to the frowning Hundred. ‘I have two knights to guard me. Come, let us be about our business!’

He strode off confidently towards the inn, tapping once more with his staff and hardly holding Eleanor’s crooked arm at all. Odo stared after him. When he looked back to see what Hundred was doing, he

was surprised to find himself alone. In just a few seconds, the elderly warrior had disappeared from the middle of the green!

‘Sire, the good villagers of Lenburh are assembled.’

Hundred’s soft voice broke the breath that Eleanor had been holding as she waited for Sir Halfdan’s burial rites to begin. The elderly knight’s body had rested all night in the manor house’s great hall, wrapped in his best cloak with his shield across his chest and his sword at his side. Eleanor had volunteered to sit with him, and Odo had joined her, relieving her at the old knight’s side when she grew tired. The two times she slept, she dreamed of her mother, who had once lain in that very spot. It seemed an age ago.

Now it was Sir Halfdan’s turn. Reeve Gorbold relinquished his position at the head of the funerary procession to Sir Egda and joined the others bearing the body. Even though he was already one of the strongest villagers in Lenburh, Odo suppressed a grunt of effort as they raised Sir Halfdan high. What the old knight had lacked in a complete set of legs he had more than made up for in girth. A lonely bell tolled as the solemn procession made down the hill to Sir Halfdan’s family crypt, past the small fenced-off area of the estate where Eleanor’s mother was buried.

Eleanor wondered if she would join her mother there one day. Someone would need to assume the mantle of Sir Halfdan’s estate, and Odo was the most likely to settle here when he attained his majority. Eleanor herself would prefer to be adventuring and seeing the world.

Deep in these thoughts, Eleanor walked into Hundred’s back as the procession came to a halt. The bodyguard clicked her tongue.

‘Brave in heart,’ said Sir Egda, tapping one end of his staff softly against the earth, ‘and noble in death, we farewell this good knight and remember his deeds.’

He stood aside to let Sir Halfdan’s bearers into the darkness of the crypt itself, to the stone plinth that had long ago been prepared by Borden, Sir Halfdan’s loyal squire, who had gone to his own grave earlier that day. Odo stooped to avoid banging his head, and tried to ignore the stories he’d heard about carnivorous barrow bats inhabiting such places. He had avoided asking Biter if they were real, in case it turned out that they were. When his hauberk snagged on the sculpted foot of a knight’s effigy protruding from another plinth, he freed himself with a quick tug and a reminder to concentrate on moving quickly but respectfully. Being a funeral bearer was a great responsibility.

Ahead of him, holding Sir Halfdan’s feet, Symon turned and bent forward. Odo followed, and together the bearers settled the fallen knight on his final resting place.

When that was done, Odo stepped back and bowed.

Outside, Runnel twitched. Eleanor drew her from her scabbard, raising the sword in sad salute. A grey light shimmered along the blade, reflections from the cloudy sky.

‘Be at peace, knight of Lenburh,’ said the blind old man. He turned and tapped the way to the village hall, following the sound of the bell. The villagers followed him, grim-faced. They had much to discuss.

‘Our lands cannot stand unprotected!’ cried Gladwine, whose sheep grazed the southeast meadows. ‘Without a steward, we are vulnerable to any passing thief or brigand!’

‘How will we find a new one?’ demanded Leof the woodworker.

‘Who will guard us?’ went up the cry from several people.

‘Not these children,’ scowled Elmer, Addyson and Aaric’s father. His sharp eyes took in Eleanor and Odo where they sat to either side of Egda and Hundred at the front of the hall.

‘We’d do a better job than a baker,’ muttered Eleanor, resenting the implication that they wouldn’t be good enough. They were knights. They had fought serious enemies and had stared down a real, live dragon – or at least they’d survived an encounter with one, which was more than most people could say, Elmer included.

‘I have sent word by pigeon to Winterset,’ said Symon across the restless crowd’s murmuring. ‘My colleagues in the capital will report to the regent, who will appoint the next steward.’

‘How long will that take?’ asked Swithe the leatherworker, who had wanted to skin the bilewolves before burning but found the hides too foul-smelling for any purpose. ‘What if more of those terrible creatures come?’

‘There will be no more,’ said Hundred in a clear and steady voice. ‘I traced the pack’s spoor to a hollow where a craft-fire recently burned. This fire was lit to summon the bilewolves and send them against my liege.’

This was news to Odo, who struggled to keep the shock from his face. Someone had deliberatelycalled the beasts that had killed four of his fellow villagers? As well as Sir Halfdan and Squire Bordan, Lenburh had lost Halthor, an apprentice smith, and Alia, who had moved from Enedham last year to look after her sick aunt.

A flame of sudden rage burned in his chest.

‘Can we track the person who lit the fire?’ he asked in a pinched voice. ‘They must be brought to justice.’

‘They will be long gone from here now,’ Hundred said with finality. ‘Our best hope of finding them is to wait until they try again.’

‘We’ll be ready when they do,’ said Eleanor, patting Runnel’s hilt. The swords stayed silent during the meeting, knowing that some in the village were still unnerved by their enchanted nature.

Elmer snorted. Egda’s beaked nose swivelled to point directly at him. The baker swallowed whatever further comments about the young knights’ competence he might have offered.

‘You will be ready,’ Egda said, ‘and Lenburh will be safe, for I am leaving at tomorrow’s dawn.’

A gasp rose up from all assembled. Only Hundred was unsurprised.

‘So soon, sire?’ asked Reeve Gorbold, who Odo had overheard making plans to profit from Egda’s presence by charging villagers in the area a halfpenny to see the former king in his new home.

‘Word of trouble in the capital reached me in my self-imposed exile,’ Egda said. ‘Winterset is my destination. Besides, I cannot remain here and put innocent lives at risk. Better to continue on my journey north and east and cut the source of our troubles from the kingdom once and for all.’ Eleanor felt a stirring of excitement in her gut. After a month of waiting for something to happen, an adventure had come right to her doorstep.

‘We must accompany you, sire,’ she said, leaping to her feet and drawing Runnel in one swift movement. ‘We will be your honour guard!’

‘If you would have us,’ said Odo, doing the same, but more cautiously. Biter clashed against his sister’s steel with a ringing chime over Egda’s head. ‘We do not wish to impose.’

A flicker passed across Hundred’s face. Was it a smile?

If so, was it of gratitude or amusement?

‘My liege needs no honour guard,’ she said. ‘He has me, and we travel fast and light into unknown danger—’

‘That’s why you need us,’ Eleanor insisted. ‘Because it’s unknown.’

‘Numbers are no substitute for experience, knightling.’

Eleanor ground her teeth. Were they always to come unstuck on this point? ‘But there’s only one way to gain experience, and if you won’t let us—’

‘Your place is in Lenburh,’ Egda pronounced. ‘I must return to Winterset and see what my great-nephew Kendryk has wrought.’

Odo frowned over this piece of information, wondering at its import. If the old king was displeased with his heir and tried to take back the throne, could that lead to unrest in the court, perhaps even civil war? Tofte had been peaceful for many generations, all the way back to King Mildred the Marvellous. The thought of villager fighting villager again was a terrible one.

That was reason enough to accompany Egda, to ensure no trouble came to the young Prince Kendryk. After all, Odo and Eleanor

ultimately owed their fealty to him, the heir to the throne, not to Egda or even to their home …

Before Eleanor, following the same reasoning, could find a diplomatic way to press for their inclusion in the party journeying to the nation’s capital, a horn sounded outside the guildhall, then a rapid patter of running feet came near. The doors burst open.

‘Strangers!’ cried a wide-eyed lad half Odo’s age. ‘Lots and lots and lots of them, on horses!’

‘Morestrangers?’ gasped Reeve Gorbold. ‘What are the odds of that?’

‘Very small, I hazard to say,’ said Symon with a thoughtful expression. ‘Lenburh has never seen such a flood.’

A babble of speculation rippled through the gathering, and Egda rapped the end of his staff against the floorboards for silence.

‘Reeve Gorbold, perhaps you should invite them in.’

‘But name no names,’ warned Hundred. ‘We are not here.’

‘Of course, sire, uh, madam, of course.’ The reeve bowed in confusion and hurried from the hall.

Odo and Eleanor exchanged a glance and followed as fast as their armour allowed, holding their swords at the ready.

‘What if it’s the people who sent the bilewolves?’ Odo whispered at Eleanor’s back.

‘I don’t hear any howling or snarling, do you?’ she cast over her shoulder.

‘We are a match for any beast!’ Biter declared.

‘Be wary, little brother,’ Runnel cautioned. ‘Someone with the skill to light a craft-fire is a worthy foe. Not to mention the person who commands them.’

Eleanor gripped her sword tightly and hurried out into the light, where she came face-to-bridle with a band of travellers on horseback, all sporting the royal seal on their breasts – a blue shield, quartered, with a silver sword, a black anvil, a red flame and a golden dragon in each segment. All the new arrivals were armed, although none had unsheathed a weapon. At their head rode a tall, thin man wearing an unfamiliar red uniform with silver piping,

topped by a wide-brimmed cloth hat, which he raised on seeing the reeve’s chain of office, and then again for the two young knights.

‘Well met, bereaved citizens of Lenburh,’ he said, holding the hat now at his chest, revealing a pate of fine white hair, brushed in a spiral descending from the top of his head. ‘Rest your troubled hearts, for I have come to give you ease.’

‘And you are?’ Reeve Gorbold asked.

‘Instrument Sceam,’ said the man with a brisk bow from his waist.

‘Your name is ‘Instrument’?’ Eleanor repeated in puzzlement.

‘Instrument is my title. I have been sent to assume the mantle of responsibility so recently vacated by Sir Halfdan.’

‘Sent by whom?’ bristled the reeve.

‘By the regent, of course,’ said Sceam with another bow.

‘So you’re to be our steward?’ Odo asked.

‘Not steward,’ the man said. ‘Instrument. Of the Crown.’

‘But we don’t know you,’ said Eleanor.

‘That hardly matters, does it?’

Reeve Gorbold straightened with a sniff. ‘Only people whose families have lived in Lenburh five generations can be stewards. That’s the rule.’

‘The rule has changed. May I come in and explain?’

‘You’d better come, I suppose. Your horses will be attended to.’

‘My thanks, Reeve Gorbold.’

‘You know my name?’

‘And those of your young companions also, Sir Odo and Sir Eleanor. I know everything about you.’

‘But … how? What are you doinghere?’

Instrument Sceam dropped lightly to the ground and produced a rolled-up parchment from one pocket. It was crumpled and stained brown at one end, as though by blood. ‘Why, I received your note.’

The message-carrying pigeon informing the capital of Sir Halfdan’s death had travelled only as far as Trumness, a town on the mountain road east of Ablerhyll. There it had caught the attention of one of

Instrument Sceam’s companions, a keen-eyed archer, and been immediately shot down.

‘You shot,’ Reeve Gorbold spluttered, ‘my pigeon?’

‘Of course,’ Sceam replied.

‘But … why?’

‘It was white.’

‘So?’

‘White pigeons are no longer authorised to carry messages to Winterset. Only the speckled variety. This is another of the many changes I have been sent to inform you about.’

‘What are these changes, exactly?’ asked Symon.

‘Well …’ Instrument Sceam placed his hands on his knees and scanned the crowd. He was seated in the place Egda had occupied a moment ago, alone on the raised dais. The former king was wearing a hood that covered the upper half of his face and standing well at the back. Eleanor recognised his nose and the stubborn jut of his jaw, but only because she was looking for it.

Of Hundred there was no sign at all.

‘The pigeons, for one.’ Sceam was happy to have their full attention and showed little sign of letting it go. ‘All communication with the capital is now limited to official channels, from Instruments such as myself to the Adjustors and the Regulators, who take the messages to the highest level. I have cages of the speckled breed in my baggage for that very purpose. They are not to be used without my express permission.’

‘Let me see if I understand this correctly,’ said Symon. ‘Instruments report to the Adjustors.’

‘Yes.’

‘And Adjustors report to the Regulators.’

‘Yes.’

‘To whom do Regulators report?’

‘To the regent.’

‘And the regent – Odelyn – reports to Prince Kendryk, the heir?’

‘Why, yes, of course. It is only proper that the regent keeps young Prince Kendryk informed for … ee … educational reasons at the least.’

Sceam’s smile was wide and seemingly sincere, although there was something in his eyes that made Eleanor’s hackles rise. Perhaps it was the familiar way he referred to the regent, the old king’s sister, and the dismissive tone he used for her grandson, the young heir who had not yet been crowned.

Or perhaps it was something more immediate.

‘Where do knights fit in?’ Eleanor asked.

‘Ah. As traditional stewards of the estates of Tofte, these honoured individuals will of course be found a role in the new system.’

‘What kind of role?’

‘It’s not my place to say. Something ceremonial, I imagine, such as standing by doorways in the capital to make them look more regal. You will be told in due course.’

Odo felt Biter stirring in his scabbard in response to the word ceremonial. No sword wanted to end up on display, doing nothing but growing dull with time and dust. No knight either.

‘There must be some kind of mistake,’ Odo started to say, but was cut off by a frail-seeming but penetrating voice from the back of the room.

‘Forgive me, I am an old blind man, and hard of hearing to boot … This new system I believe I heard you speak of … is it the work of Prince Kendryk himself?’

‘Of course,’ Sceam said, not recognising his interlocutor. ‘The regent made the announcement on his behalf three months ago. Implementation throughout the kingdom is well under way, although outlying regions such as this one are naturally behind schedule. We will soon make that up, now that I am here!’

The Instrument clapped his hands in eagerness to get started.

‘My collectors will move among you over the coming week,’ he declared, ‘collecting this month’s tithe.’

‘But Sir Halfdan paid the Crown just lastweek!’ spluttered Reeve Gorbold.

‘I’m afraid there’s no record of that in the capital,’ Sceam said. ‘Also, from this month, tithes will increase by five silver pennies per household.’

‘What?!’ the reeve exclaimed, but he was far from the only person in the room to think it.

‘To cover the costs of instituting the new system. Prosperity has its price!’

‘This is preposterous—’

‘It is progress, Reeve Gorbold. Now, I am weary. I will retire to the manor house to rest. No need to show me. I know the way.’

With that, he stood and pressed through the dumbfounded crowd, flanked by two of his well-armed aides. Eleanor went to step into his path, unwilling to let the matter of this ‘new system’ go so readily. She hadn’t spent her whole life dreaming of being a knight only to end up standing around in a doorway holding a pike!

Before she could take half a step, however, a small but very strong hand gripped her elbow.

‘Discretion,’ whispered Hundred into Eleanor’s ear, ‘is our best stratagem at this time.’

Eleanor frowned at the old woman. How would saying nothing be of any use to anyone?

‘We will talk around the back,’ Hundred reassured her, nodding to where Odo was being led off by Symon, with Egda bringing up a close rear.

Under cover of Sceam’s departure, the five of them slipped from the guildhall by the tradesperson’s door.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

towards the whole free colored population of the United States. I understand that policy to comprehend: First, the complete suppression of all anti-slavery discussion; second, the expulsion of the entire free people of the United States; third, the nationalization of slavery; fourth, guarantees for the endless perpetuation of slavery and its extension over Mexico and Central America. Sir, these objects are forcibly presented to us in the stern logic of passing events, and in all the facts that have been before us during the last three years. The country has been and is dividing on these grand issues. Old party ties are broken. Like is finding its like on both sides of these issues, and the great battle is at hand. For the present the best representative of the slavery party is the Democratic party. Its great head for the present is President Pierce, whose boast it was before his election, that his whole life had been consistent with the interests of slavery—that he is above reproach on that score. In his inaugural address he reassures the South on this point, so there shall be no misapprehension. Well, the head of the slave power being in power it is natural that the pro-slavery elements should cluster around his administration, and that is rapidly being done. The stringent protectionist and the freetrader strike hands. The supporters of Fillmore are becoming the supporters of Pierce. Silver Gray Whigs shake-hands with Hunker Democrats, the former only differing from the latter in name. They are in fact of one heart and one mind, and the union is natural and perhaps inevitable. Pilate and Herod made friends. The key-stone to the arch of this grand union of forces of the slave party is the so-called Compromise of 1850. In that measure we have all the objects of our slaveholding policy specified. It is, sir, favorable to this view of the situation, that the whig party and the democratic party bent lower, sunk deeper, and strained harder in their conventions, preparatory to the late presidential election to meet the demands of slavery Never did parties come before the northern people with propositions of such undisguised contempt for the moral sentiment and religious ideas of that people. They dared to ask them to unite with them in a war upon free speech, upon conscience, and to drive the

Almighty presence from the councils of the nation. Resting their platforms upon the fugitive slave bill they have boldly asked this people for political power to execute its horrible and hell-black provisions. The history of that election reveals with great clearness, the extent to which slavery has “shot its leprous distillment” through the lifeblood of the nation. The party most thoroughly opposed to the cause of justice and humanity triumphed, while the party only suspected of a leaning toward those principles was overwhelmingly defeated, and some say annihilated. But here is a still more important fact, and still better discloses the designs of the slave power. It is a fact full of meaning, that no sooner did the democratic party come into power than a system of legislation was presented to all the legislatures of the Northern States designed to put those States in harmony with the fugitive slave law, and with the malignant spirit evinced by the national government towards the free colored inhabitants of the country. The whole movement on the part of the States bears unmistakable evidence of having one origin, of emanating from one head, and urged forward by one power. It was simultaneous, uniform, and general, and looked only to one end. It was intended to put thorns under feet already bleeding; to crush a people already bowed down; to enslave a people already but half free; in a word, it was intended and well calculated to discourage, dishearten, and if possible to drive the whole free colored people out of the country. In looking at the black law then recently enacted in the State of Illinois one is struck dumb by its enormity. It would seem that the men who passed that law, had not only successfully banished from their minds all sense of justice, but all sense of shame as well; these law codes propose to sell the bodies and souls of the blacks to provide the means of intelligence and refinement for the whites; to rob every black stranger who ventures among them to increase their educational fund.

“While this kind of legislation is going on in the States, a proslavery political board of health is being established at Washington. Senators Hale, Chase, and Sumner are robbed of their senatorial rights and dignity as representatives of sovereign

States, because they have refused to be inoculated with the proslavery virus of the times. Among the services which a senator is expected to perform, are many that can only be done efficiently as members of important committees, and the slave power in the Senate, in saying to these honorable senators, you shall not serve on the committees of this body, took the responsibility of insulting and robbing the States which has sent them there. It is an attempt at Washington to decide for the States who the States shall send to the Senate. Sir, it strikes me that this aggression on the part of the slave power did not meet at the hands of the proscribed and insulted senators the rebuke which we had a right to expect from them. It seems to me that a great opportunity was lost, that the great principle of senatorial equality was left undefended at a time when its vindication was sternly demanded. But it is not to the purpose of my present statement to criticize the conduct of friends. Much should be left to the discretion of anti-slavery men in Congress. Charges of recreancy should never be made but on the most sufficient grounds. For of all places in the world where an anti-slavery man needs the confidence and encouragement of his friends, I take Washington—the citadel of slavery—to be that place.

“Let attention now be called to the social influences operating and coöperating with the slave power of the time, designed to promote all its malign objects. We see here the black man attacked in his most vital interests: prejudice and hate are systematically excited against him. The wrath of other laborers is stirred up against him. The Irish, who, at home, readily sympathize with the oppressed everywhere, are instantly taught when they step upon our soil to hate and despise the negro. They are taught to believe that he eats the bread that belongs to them. The cruel lie is told them, that we deprive them of labor and receive the money which would otherwise make its way into their pockets. Sir, the Irish-American will find out his mistake one day. He will find that in assuming our avocation, he has also assumed our degradation. But for the present we are the sufferers. Our old employments by which we have been accustomed to gain a livelihood are gradually slipping from our

hands: every hour sees us elbowed out of some employment to make room for some newly arrived emigrant from the Emerald Isle, whose hunger and color entitle him to special favor. These white men are becoming house-servants, cooks, stewards, waiters, and flunkies. For aught I see they adjust themselves to their stations with all proper humility. If they cannot rise to the dignity of white men, they show that they can fall to the degradation of black men. But now, sir, look once more! While the colored people are thus elbowed out of employment; while a ceaseless enmity in the Irish is excited against us; while State after State enacts laws against us; while we are being hunted down like wild beasts; while we are oppressed with a sense of increasing insecurity, the American Colonization Society, with hypocrisy written on its brow, comes to the front, awakens to new life, and vigorously presses its scheme for our expatriation upon the attention of the American people. Papers have been started in the North and the South to promote this long cherished object—to get rid of the negro, who is presumed to be a standing menace to slavery. Each of these papers is adapted to the latitude in which it is published, but each and all are united in calling upon the government for appropriations to enable the Colonization Society to send us out of the country by steam. Evidently this society looks upon our extremity as their opportunity, and whenever the elements are stirred against us, they are stimulated to unusual activity. They do not deplore our misfortunes, but rather rejoice in them, since they prove that the two races cannot flourish on the same soil. But, sir, I must hasten. I have thus briefly given my view of one aspect of the present condition and future prospects of the colored people of the United States. And what I have said is far from encouraging to my afflicted people. I have seen the cloud gather upon the sable brows of some who hear me. I confess the case looks bad enough. Sir, I am not a hopeful man. I think I am apt to undercalculate the benefits of the future. Yet, sir, in this seemingly desperate case, I do not despair for my people. There is a bright side to almost every picture, and ours is no exception to the general rule. If the influences against us are strong, those

for us are also strong. To the inquiry, will our enemies prevail in the execution of their designs—in my God, and in my soul, I believe they will not. Let us look at the first object sought for by the slavery party of the country, viz., the suppression of the antislavery discussion. They desire to suppress discussion on this subject, with a view to the peace of the slaveholder and the security of slavery. Now, sir, neither the principle nor the subordinate objects, here declared, can be at all gained by the slave power, and for this reason: it involves the proposition to padlock the lips of the whites, in order to secure the fetters on the limbs of the blacks. The right of speech, precious and priceless, cannot—will not—be surrendered to slavery. Its suppression is asked for, as I have said, to give peace and security to slaveholders. Sir, that thing cannot be done. God has interposed an insuperable obstacle to any such result. “There can be no peace, saith my God, to the wicked.” Suppose it were possible to put down this discussion, what would it avail the guilty slaveholder, pillowed as he is upon the heaving bosoms of ruined souls? He could not have a peaceful spirit. If every antislavery tongue in the nation were silent—every anti-slavery organization dissolved—every anti-slavery periodical, paper, pamphlet, book, or what not, searched out, burned to ashes, and their ashes given to the four winds of heaven, still, still the slaveholder could have no peace. In every pulsation of his heart, in every throb of his life, in every glance of his eye, in the breeze that soothes, and in the thunder that startles, would be waked up an accuser, whose cause is, ‘thou art verily guilty concerning thy brother.’”

This is no fancy sketch of the times indicated. The situation during all the administration of President Pierce was only less threatening and stormy than that under the administration of James Buchanan. One sowed, the other reaped. One was the wind, the other was the whirlwind. Intoxicated by their success in repealing the Missouri compromise—in divesting the native-born colored man of American citizenship—in harnessing both the Whig and Democratic parties to the car of slavery, and in holding continued possession of

the national government, the propagandists of slavery threw off all disguises, abandoned all semblance of moderation, and very naturally and inevitably proceeded under Mr. Buchanan, to avail themselves of all the advantages of their victories. Having legislated out of existence the great national wall, erected in the better days of the republic, against the spread of slavery, and against the increase of its power—having blotted out all distinction, as they thought, between freedom and slavery in the law, theretofore, governing the Territories of the United States, and having left the whole question of the legislation or prohibition of slavery to be decided by the people of a Territory, the next thing in order was to fill up the Territory of Kansas—the one likely to be first organized—with a people friendly to slavery, and to keep out all such as were opposed to making that Territory a free State. Here was an open invitation to a fierce and bitter strife; and the history of the times shows how promptly that invitation was accepted by both classes to which it was given, and the scenes of lawless violence and blood that followed.

All advantages were at first on the side of those who were for making Kansas a slave State. The moral force of the repeal of the Missouri compromise was with them; the strength of the triumphant Democratic party was with them; the power and patronage of the federal government was with them; the various governors, sent out under the Territorial government, was with them; and, above all, the proximity of the Territory to the slave State of Missouri favored them and all their designs. Those who opposed the making Kansas a slave State, for the most part were far away from the battleground, residing chiefly in New England, more than a thousand miles from the eastern border of the Territory, and their direct way of entering it was through a country violently hostile to them. With such odds against them, and only an idea—though a grand one—to support them, it will ever be a wonder that they succeeded in making Kansas a free State. It is not my purpose to write particularly of this or of any other phase of the conflict with slavery, but simply to indicate the nature of the struggle, and the successive steps, leading to the final result. The important point to me, as one desiring to see the slave power crippled, slavery limited and abolished, was the effect of this Kansas battle upon the moral sentiment of the North: how it made

abolitionists before they themselves became aware of it, and how it rekindled the zeal, stimulated the activity, and strengthened the faith of our old anti-slavery forces. “Draw on me for $1,000 per month while the conflict lasts,” said the great-hearted Gerrit Smith. George L. Stearns poured out his thousands, and anti-slavery men of smaller means were proportionally liberal. H. W. Beecher shouted the right word at the head of a mighty column; Sumner in the Senate spoke as no man had ever spoken there before. Lewis Tappan representing one class of the old opponents of slavery, and William L. Garrison the other, lost sight of their former differences, and bent all their energies to the freedom of Kansas. But these and others were merely generators of anti-slavery force. The men who went to Kansas with the purpose of making it a free State, were the heroes and martyrs. One of the leaders in this holy crusade for freedom, with whom I was brought into near relations, was John Brown, whose person, house, and purposes I have already described. This brave old man and his sons were amongst the first to hear and heed the trumpet of freedom calling them to battle. What they did and suffered, what they sought and gained, and by what means, are matters of history, and need not be repeated here.

When it became evident, as it soon did, that the war for and against slavery in Kansas was not to be decided by the peaceful means of words and ballots, but that swords and bullets were to be employed on both sides, Captain John Brown felt that now, after long years of waiting, his hour had come, and never did man meet the perilous requirements of any occasion more cheerfully, courageously, and disinterestedly than he. I met him often during this struggle, and saw deeper into his soul than when I met him in Springfield seven or eight years before, and all I saw of him gave me a more favorable impression of the man, and inspired me with a higher respect for his character. In his repeated visits to the East to obtain necessary arms and supplies, he often did me the honor of spending hours and days with me at Rochester. On more than one occasion I got up meetings and solicited aid to be used by him for the cause, and I may say without boasting that my efforts in this respect were not entirely fruitless. Deeply interested as “Ossawatamie Brown” was in Kansas he never lost sight of what he

called his greater work—the liberation of all the slaves in the United States. But for the then present he saw his way to the great end through Kansas. It would be a grateful task to tell of his exploits in the border struggle, how he met persecution with persecution, war with war, strategy with strategy, assassination and house-burning with signal and terrible retaliation, till even the blood-thirsty propagandists of slavery were compelled to cry for quarter. The horrors wrought by his iron hand cannot be contemplated without a shudder, but it is the shudder which one feels at the execution of a murderer The amputation of a limb is a severe trial to feeling, but necessity is a full justification of it to reason. To call out a murderer at midnight, and without note or warning, judge or jury, run him through with a sword, was a terrible remedy for a terrible malady. The question was not merely which class should prevail in Kansas, but whether free-state men should live there at all. The border ruffians from Missouri had openly declared their purpose not only to make Kansas a slave state, but that they would make it impossible for freestate men to live there. They burned their towns, burned their farmhouses, and by assassination spread terror among them until many of the free-state settlers were compelled to escape for their lives. John Brown was therefore the logical result of slaveholding persecutions. Until the lives of tyrants and murderers shall become more precious in the sight of men than justice and liberty, John Brown will need no defender. In dealing with the ferocious enemies of the free-state cause in Kansas he not only showed boundless courage but eminent military skill. With men so few and odds against him so great, few captains ever surpassed him in achievements, some of which seem too disproportionate for belief, and yet no voice has yet called them in question. With only eight men he met, fought, whipped, and captured Henry Clay Pate with twenty-five well-armed and well-mounted men. In this battle he selected his ground so wisely, handled his men so skillfully, and attacked his enemies so vigorously, that they could neither run nor fight, and were therefore compelled to surrender to a force less than one-third their own. With just thirty men on another memorable occasion he met and vanquished 400 Missourians under the command of General Read. These men had come into the territory under an oath never to return

to their homes in Missouri till they had stamped out the last vestige of the free-state spirit in Kansas. But a brush with old Brown instantly took this high conceit out of them, and they were glad to get home upon any terms, without stopping to stipulate. With less than 100 men to defend the town of Lawrence, he offered to lead them and give battle to 1,400 men on the banks of the Waukerusia river, and was much vexed when his offer was refused by General Jim Lane and others, to whom the defense of the place was committed. Before leaving Kansas he went into the border of Missouri and liberated a dozen slaves in a single night, and despite of slave laws and marshals, he brought these people through a half dozen States and landed them safe in Canada. The successful efforts of the North in making Kansas a free State, despite all the sophistical doctrines, and the sanguinary measures of the South to make it a slave State, exercised a potent influence upon subsequent political forces and events in the then near future. It is interesting to note the facility with which the statesmanship of a section of the country adapted its convictions to changed conditions. When it was found that the doctrine of popular sovereignty (first I think invented by General Cass, and afterwards adopted by Stephen A. Douglas) failed to make Kansas a slave State, and could not be safely trusted in other emergencies, southern statesmen promptly abandoned and reprobated that doctrine, and took what they considered firmer ground. They lost faith in the rights, powers, and wisdom of the people and took refuge in the Constitution. Henceforth the favorite doctrine of the South was that the people of a territory had no voice in the matter of slavery whatever; that the Constitution of the United States, of its own force and effect, carried slavery safely into any territory of the United States and protected the system there until it ceased to be a territory and became a State. The practical operation of this doctrine would be to make all the future new States slaveholding States, for slavery once planted and nursed for years in a territory would easily strengthen itself against the evil day and defy eradication. This doctrine was in some sense supported by Chief Justice Taney, in the infamous Dred Scott decision. This new ground, however, was destined to bring misfortune to its inventors, for it divided for a time the democratic party, one faction of it going with

John C. Breckenridge and the other espousing the cause of Stephen A. Douglas; the one held firmly to the doctrine that the United States Constitution, without any legislation, territorial, national, or otherwise, by its own force and effect, carried slavery into all the territories of the United States; the other held that the people of a territory had the right to admit slavery or reject slavery, as in their judgment they might deem best. Now, while this war of words—this conflict of doctrines—was in progress, the portentous shadow of a stupendous civil war became more and more visible. Bitter complaints were raised by the slaveholders that they were about to be despoiled of their proper share in territory won by a common valor, or bought by a common treasure. The North, on the other hand, or rather a large and growing party at the North, insisted that the complaint was unreasonable and groundless; that nothing properly considered as property was excluded or meant to be excluded from the territories; that southern men could settle in any territory of the United States with some kinds of property, and on the same footing and with the same protection as citizens of the North; that men and women are not property in the same sense as houses, lands, horses, sheep, and swine are property, and that the fathers of the Republic neither intended the extension nor the perpetuity of slavery; that liberty is national, and slavery is sectional. From 1856 to 1860 the whole land rocked with this great controversy. When the explosive force of this controversy had already weakened the bolts of the American Union; when the agitation of the public mind was at its topmost height; when the two sections were at their extreme points of difference; when comprehending the perilous situation, such statesmen of the North as William H. Seward sought to allay the rising storm by soft, persuasive speech, and when all hope of compromise had nearly vanished, as if to banish even the last glimmer of hope for peace between the sections, John Brown came upon the scene. On the night of the 16th of October, 1859, there appeared near the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, a party of 19 men—14 white and 5 colored. They were not only armed themselves, but they brought with them a large supply of arms for such persons as might join them. These men invaded the town of Harper’s Ferry, disarmed the watchman, took possession of the

arsenal, rifle factory, armory, and other government property at that place, arrested and made prisoners of nearly all the prominent citizens in the neighborhood, collected about 50 slaves, put bayonets into the hands of such as were able and willing to fight for their liberty, killed 3 men, proclaimed general emancipation, held the ground more than thirty hours, were subsequently overpowered and nearly all killed, wounded, or captured by a body of United States troops under command of Col. Robert E. Lee, since famous as the rebel General Lee. Three out of the nineteen invaders were captured while fighting, and one of them was Capt. John Brown—the man who originated, planned, and commanded the expedition. At the time of his capture Capt. Brown was supposed to be mortally wounded, as he had several ugly gashes and bayonet wounds on his head and body, and apprehending that he might speedily die, or that he might be rescued by his friends, and thus the opportunity to make him a signal example of slaveholding vengeance, would be lost, his captors hurried him to Charlestown, 10 miles further within the border of Virginia, placed him in prison strongly guarded by troops, and before his wounds were healed he was brought into court, subjected to a nominal trial, convicted of high-treason and inciting slaves to insurrection, and was executed.

His corpse was given up to his woe-stricken widow, and she, assisted by anti-slavery friends, caused it to be borne to North Elba, Essex county, N. Y., and there his dust now reposes amid the silent, solemn, and snowy grandeurs of the Adirondacks. This raid upon Harper’s Ferry was as the last straw to the camel’s back. What in the tone of southern sentiment had been fierce before became furious and uncontrollable now. A scream for vengeance came up from all sections of the slave States and from great multitudes in the North. All who were supposed to have been any way connected with John Brown were to be hunted down and surrendered to the tender mercies of slaveholding and panic-stricken Virginia, and there to be tried after the fashion of John Brown’s trial, and of course to be summarily executed.

On the evening when the news came that John Brown had taken and was then holding the town of Harper’s Ferry, it so happened that

I was speaking to a large audience in National Hall, Philadelphia. The announcement came upon us with the startling effect of an earthquake. It was something to make the boldest hold his breath. I saw at once that my old friend had attempted what he had long ago resolved to do, and I felt certain that the result must be his capture and destruction. As I expected, the next day brought the news that with two or three men he had fortified and was holding a small engine house, but that he was surrounded by a body of Virginia militia, who thus far had not ventured to capture the insurgents, but that escape was impossible. A few hours later and word came that Colonel Robert E. Lee with a company of United States troops had made a breach in Capt. Brown’s fort, and had captured him alive though mortally wounded. His carpet bag had been secured by Governor Wise, and that it was found to contain numerous letters and documents which directly implicated Gerritt Smith, Joshua R. Giddings, Samuel G. Howe, Frank P. Sanborn, and myself. This intelligence was soon followed by a telegram saying that we were all to be arrested. Knowing that I was then in Philadelphia, stopping with my friend, Thomas J. Dorsey, Mr. John Hern, the telegraph operator, came to me and with others urged me to leave the city by the first train, as it was known through the newspapers that I was then in Philadelphia, and officers might even then be on my track. To me there was nothing improbable in all this. My friends for the most part were appalled at the thought of my being arrested then or there, or while on my way across the ferry from Walnut street wharf to Camden, for there was where I felt sure the arrest would be made, and asked some of them to go so far as this with me merely to see what might occur, but upon one ground or another they all thought it best not to be found in my company at such a time, except dear old Franklin Turner—a true man. The truth is, that in the excitement which prevailed my friends had reason to fear that the very fact that they were with me would be a sufficient reason for their arrest with me. The delay in the departure of the steamer seemed unusually long to me, for I confess I was seized with a desire to reach a more northern latitude. My friend Frank did not leave my side till “all ashore” was ordered and the paddles began to move. I reached New York at night, still under the apprehension of arrest at any moment,

but no signs of such event being made, I went at once to the Barclay street ferry, took the boat across the river and went direct to Washington street, Hoboken, the home of Mrs. Marks, where I spent the night, and I may add without undue profession of timidity, an anxious night. The morning papers brought no relief, for they announced that the government would spare no pains in ferretting out and bringing to punishment all who were connected with the Harper’s Ferry outrage, and that papers as well as persons would be searched for. I was now somewhat uneasy from the fact that sundry letters and a constitution written by John Brown were locked up in my desk in Rochester. In order to prevent these papers from falling into the hands of the government of Virginia, I got my friend Miss Ottilia Assing to write at my dictation the following telegram to B. F. Blackall, the telegraph operator in Rochester, a friend and frequent visitor at my house, who would readily understand the meaning of the dispatch:

“B. F. B�������, Esq.,

“Tell Lewis (my oldest son) to secure all the important papers in my high desk.”

I did not sign my name, and the result showed that I had rightly judged that Mr. Blackall would understand and promptly attend to the request. The mark of the chisel with which the desk was opened is still on the drawer, and is one of the traces of the John Brown raid. Having taken measures to secure my papers the trouble was to know just what to do with myself. To stay in Hoboken was out of the question, and to go to Rochester was to all appearance to go into the hands of the hunters, for they would naturally seek me at my home if they sought me at all. I, however, resolved to go home and risk my safety there. I felt sure that once in the city I could not be easily taken from there without a preliminary hearing upon the requisition, and not then if the people could be made aware of what was in progress. But how to get to Rochester became a serious question. It would not do to go to New York city and take the train, for that city was not less incensed against the John Brown conspirators than

many parts of the South. The course hit upon by my friends, Mr Johnston and Miss Assing, was to take me at night in a private conveyance from Hoboken to Paterson, where I could take the Erie railroad for home. This plan was carried out and I reached home in safety, but had been there but a few moments when I was called upon by Samuel D. Porter, Esq., and my neighbor, LieutenantGovernor Selden, who informed me that the governor of the State would certainly surrender me on a proper requisition from the governor of Virginia, and that while the people of Rochester would not permit me to be taken South, yet in order to avoid collision with the government and consequent bloodshed, they advised me to quit the country, which I did—going to Canada. Governor Wise in the meantime, being advised that I had left Rochester for the State of Michigan, made requisition on the governor of that State for my surrender to Virginia.

The following letter from Governor Wise to President James Buchanan (which since the war was sent me by B. J. Lossing, the historian,) will show by what means the governor of Virginia meant to get me in his power, and that my apprehensions of arrest were not altogether groundless:

[Confidential.]

R�������, V�., Nov. 13, 1859.

To His Excellency, James Buchanan, President of the United States, and to the Honorable Postmaster-General of the United States:

G��������—I have information such as has caused me, upon proper affidavits, to make requisition upon the Executive of Michigan for the delivery up of the person of Frederick Douglass, a negro man, supposed now to be in Michigan, charged with murder, robbery, and inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia. My agents for the arrest and reclamation of the person so charged are Benjamin M. Morris and William N. Kelly. The latter has the requisition, and will wait on you to the end of obtaining nominal authority as post-office agents. They need be very secretive in this matter, and some pretext for traveling

through the dangerous section for the execution of the laws in this behalf, and some protection against obtrusive, unruly, or lawless violence. If it be proper so to do, will the postmastergeneral be pleased to give to Mr. Kelly, for each of these men, a permit and authority to act as detectives for the post-office department, without pay, but to pass and repass without question, delay or hindrance?

Respectfully submitted by your obedient servant, H���� A. W���.

There is no reason to doubt that James Buchanan afforded Governor Wise all the aid and coöperation for which he was asked. I have been informed that several United States marshals were in Rochester in search of me within six hours after my departure. I do not know that I can do better at this stage of my story than to insert the following letter, written by me to the Rochester Democrat and American:

C����� W���, Oct 31st, 1859.

M�. E�����:

I notice that the telegraph makes Mr. Cook (one of the unfortunate insurgents at Harper’s Ferry, and now a prisoner in the hands of the thing calling itself the Government of Virginia, but which in fact is but an organized conspiracy by one part of the people against another and weaker) denounce me as a coward, and assert that I promised to be present in person at the Harper’s Ferry insurrection. This is certainly a very grave impeachment whether viewed in its bearings upon friends or upon foes, and you will not think it strange that I should take a somewhat serious notice of it. Having no acquaintance whatever with Mr. Cook, and never having exchanged a word with him about Harper’s Ferry insurrection, I am disposed to doubt if he could have used the language concerning me, which the wires attribute to him. The lightning when speaking for itself, is among the most direct, reliable, and truthful of things; but when

speaking of the terror-stricken slaveholders at Harper’s Ferry, it has been made the swiftest of liars. Under its nimble and trembling fingers it magnifies 17 men into 700 and has since filled the columns of the New York Herald for days with its interminable contradictions. But assuming that it has told only the simple truth as to the sayings of Mr. Cook in this instance, I have this answer to make to my accuser: Mr. Cook may be perfectly right in denouncing me as a coward; I have not one word to say in defense or vindication of my character for courage; I have always been more distinguished for running than fighting, and tried by the Harper’s-Ferry-insurrection-test, I am most miserably deficient in courage, even more so than Cook when he deserted his brave old captain and fled to the mountains. To this extent Mr. Cook is entirely right, and will meet no contradiction from me, or from anybody else. But wholly, grievously and most unaccountably wrong is Mr. Cook when he asserts that I promised to be present in person at the Harper’s Ferry insurrection. Of whatever other imprudence and indiscretion I may have been guilty, I have never made a promise so rash and wild as this. The taking of Harper’s Ferry was a measure never encouraged by my word or by my vote. At any time or place, my wisdom or my cowardice, has not only kept me from Harper’s Ferry, but has equally kept me from making any promise to go there. I desire to be quite emphatic here, for of all guilty men, he is the guiltiest who lures his fellowmen to an undertaking of this sort, under promise of assistance which he afterwards fails to render. I therefore declare that there is no man living, and no man dead, who if living, could truthfully say that I ever promised him, or anybody else, either conditionally, or otherwise, that I would be present in person at the Harper’s Ferry insurrection. My field of labor for the abolition of slavery has not extended to an attack upon the United States arsenal. In the teeth of the documents already published and of those which may hereafter be published, I affirm that no man connected with that insurrection, from its noble and heroic leader down, can connect my name with a single broken promise of any sort whatever. So much I deem it

proper to say negatively The time for a full statement of what I know and of ��� I know of this desperate but sublimely disinterested effort to emancipate the slaves of Maryland and Virginia from their cruel taskmasters, has not yet come, and may never come. In the denial which I have now made, my motive is more a respectful consideration for the opinions of the slave’s friends than from my fear of being made an accomplice in the general conspiracy against slavery, when there is a reasonable hope for success. Men who live by robbing their fellowmen of their labor and liberty have forfeited their right to know anything of the thoughts, feelings, or purposes of those whom they rob and plunder. They have by the single act of slaveholding, voluntarily placed themselves beyond the laws of justice and honor, and have become only fitted for companionship with thieves and pirates—the common enemies of God and of all mankind. While it shall be considered right to protect oneself against thieves, burglars, robbery, and assassins, and to slay a wild beast in the act of devouring his human prey, it can never be wrong for the imbruted and whip-scarred slaves, or their friends, to hunt, harass, and even strike down the traffickers in human flesh. If any body is disposed to think less of me on account of this sentiment, or because I may have had a knowledge of what was about to occur, and did not assume the base and detestable character of an informer, he is a man whose good or bad opinion of me may be equally repugnant and despicable.

Entertaining these sentiments, I may be asked why I did not join John Brown—the noble old hero whose one right hand has shaken the foundation of the American Union, and whose ghost will haunt the bed-chambers of all the born and unborn slaveholders of Virginia through all their generations, filling them with alarm and consternation. My answer to this has already been given; at least impliedly given—“The tools to those who can use them!” Let every man work for the abolition of slavery in his own way I would help all and hinder none. My position in regard to the Harper’s Ferry insurrection may be easily inferred from these remarks, and I shall be glad if those papers which

have spoken of me in connection with it, would find room for this brief statement. I have no apology for keeping out of the way of those gentlemanly United States marshals, who are said to have paid Rochester a somewhat protracted visit lately, with a view to an interview with me. A government recognizing the validity of the Dred Scott decision at such a time as this, is not likely to have any very charitable feelings towards me, and if I am to meet its representatives I prefer to do so at least upon equal terms. If I have committed any offense against society I have done so on the soil of the State of New York, and I should be perfectly willing to be arraigned there before an impartial jury; but I have quite insuperable objections to being caught by the hounds of Mr. Buchanan, and “bagged” by Gov. Wise. For this appears to be the arangement. Buchanan does the fighting and hunting, and Wise “bags” the game. Some reflections may be made upon my leaving on a tour to England just at this time. I have only to say that my going to that country has been rather delayed than hastened by the insurrection at Harper’s Ferry. All know that I had intended to leave here in the first week of November.

F�������� D�������.”