Eugene F. Brigham

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/intermediate-financial-management-eugene-f-brigha m/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Financial Management: Theory & Practice Eugene F. Brigham

https://textbookfull.com/product/financial-management-theorypractice-eugene-f-brigham/

Fundamentals of Financial Management Eugene F. Brigham

https://textbookfull.com/product/fundamentals-of-financialmanagement-eugene-f-brigham/

Fundamentals of Financial Management Concise Edition

Eugene F. Brigham

https://textbookfull.com/product/fundamentals-of-financialmanagement-concise-edition-eugene-f-brigham/

Fundamentals of Financial Management, Concise 10th Edition Eugene F. Brigham

https://textbookfull.com/product/fundamentals-of-financialmanagement-concise-10th-edition-eugene-f-brigham/

Financial Management Theory Practice 16th Edition

Brigham Eugene F Ehrhardt Michael C

https://textbookfull.com/product/financial-management-theorypractice-16th-edition-brigham-eugene-f-ehrhardt-michael-c/

Financial Management Theory and Practice 14th Edition

Eugene F Brigham Michael C Ehrhardt

https://textbookfull.com/product/financial-management-theory-andpractice-14th-edition-eugene-f-brigham-michael-c-ehrhardt/

Financial management theory and practice Third Canadian Edition Brigham

https://textbookfull.com/product/financial-management-theory-andpractice-third-canadian-edition-brigham/

About Financial Accounting - Volume 1 F. Doussy

https://textbookfull.com/product/about-financial-accountingvolume-1-f-doussy/

About Financial Accounting Volume 2 (8th Edition) F Doussy

https://textbookfull.com/product/about-financial-accountingvolume-2-8th-edition-f-doussy/

Intermediate Financial Management

Thir T een T h e di T ion

Eugene F. Brigham University of Florida

Phillip R. Daves University of Tennessee

This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions, some third party content may be suppressed. Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. The publisher reserves the right to remove content from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. For valuable information on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate formats, please visit www.cengage.com/highered to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for materials in your areas of interest.

Important Notice: Media content referenced within the product description or the product text may not be available in the eBook version.

Intermediate Financial Management, 13th Edition

Eugene F. Brigham and Phillip R. Daves

Senior Vice President, Higher Ed Product,

Content, and Market Development: Erin Joyner

VP, B&E, 4LTR and Support Program: Mike Schenk

Sr. Product Team Manager: Joe Sabatino

Content Developer: Brittany Waitt

Product Assistant: Renee Schnee

Sr. Marketing Manager: Nathan Anderson

Content Project Manager: Nadia Saloom

Digital Content Designer: Brandon C. Foltz

Digital Project Manager: Mark Hopkinson

Marketing Communications Manager: Sarah Greber

Production Service: MPS Limited

Sr. Art Director: Michelle Kunkler

Text Designer: cmillerdesign

Cover Designer: cmillerdesign

Cover Image: SFIO CRACHO/Shutterstock.com

Design Image: SFIO CRACHO/Shutterstock.com

Intellectual Property

Analyst: Reba A. Frederics

Project Manager: Erika A. Mugavin

© 2019, 2016 Cengage Learning, Inc.

Unless otherwise noted, all content is © Cengage

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706.

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions.

Further permissions questions can be emailed to permissionrequest@cengage.com.

Many of the figures and tables in this text were created jointly by Eugene F. Brigham, Phillip R. Daves, and Michael C. Ehrhardt for use in both Intermediate Financial Management and Financial Management: Theory and Practice.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017959754

ISBN: 978-1-337-39508-3

Cengage

20 Channel Center Street Boston, MA 02210

USA

Cengage is a leading provider of customized learning solutions with employees residing in nearly 40 different countries and sales in more than 125 countries around the world. Find your local representative at: www.cengage.com.

Cengage products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd.

To learn more about Cengage platforms and services, visit www.cengage.com.

To register or access your online learning solution or purchase materials for your course, visit www.cengagebrain.com.

Printed in the United States of America

Print Number: 01 Print Year: 2018

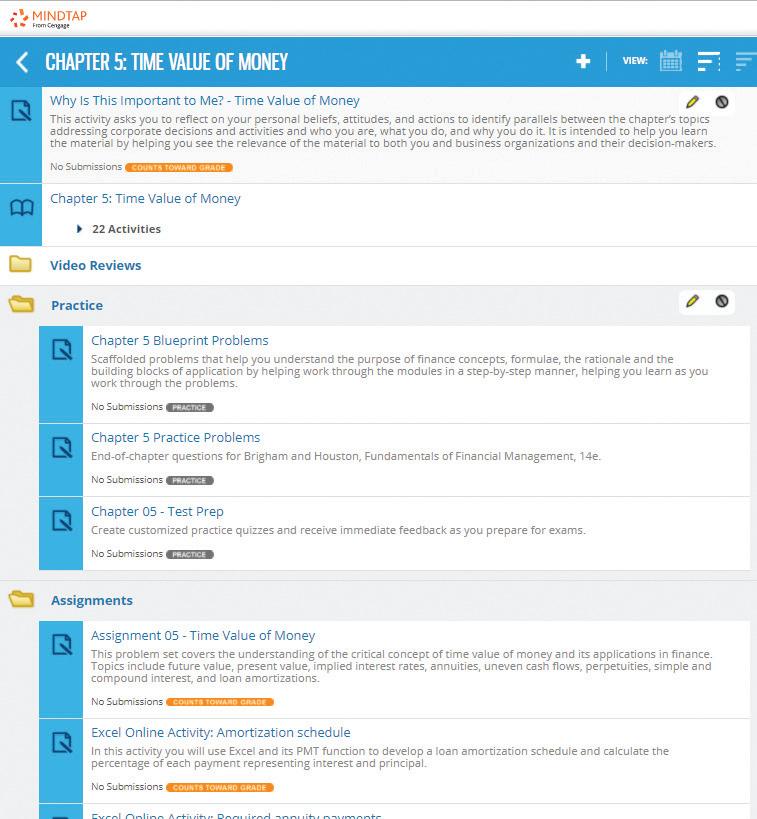

MindTap for Intermediate Financial Management

MindTap, featuring all-new Excel Online integration powered by Microsoft, is a complete digital solution for the corporate finance course. It has enhancements that take students from learning basic financial concepts to actively engaging in critical-thinking applications, while learning valuable Excel skills for their future careers.

Ev E rything you n EE d in on E plac E .

Cut prep time with MindTap preloaded, organized course materials. Teach more efficiently with interactive multimedia, assignments, quizzes, and more.

Empow E r your stud E nts to r E ach th E ir pot E ntial.

Built-in metrics provide insight into student engagement. Identify topics needing extra instruction. Instantly communicate with struggling students to speed progress.

your cours E . your cont E nt.

MindTap gives you complete control over your course. You can rearrange textbook chapters, add your own notes, and embed a variety of content—including Open Educational Resources (OER).

a d E dicat E d t E am, wh E n E v E r you n EE d it.

MindTap is backed by a personalized team eager to help you every step of the way. We’ll help set up your course, tailor it to your specific objectives, and stand by to provide support.

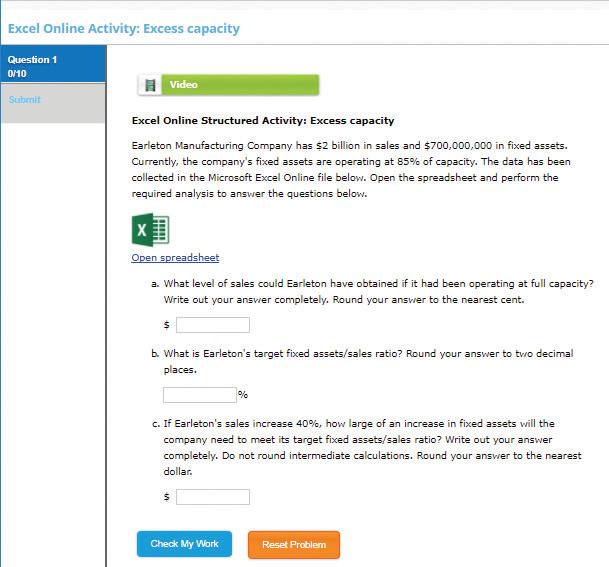

Elevate Critical Thinking through a variety of unique Assessment Tools

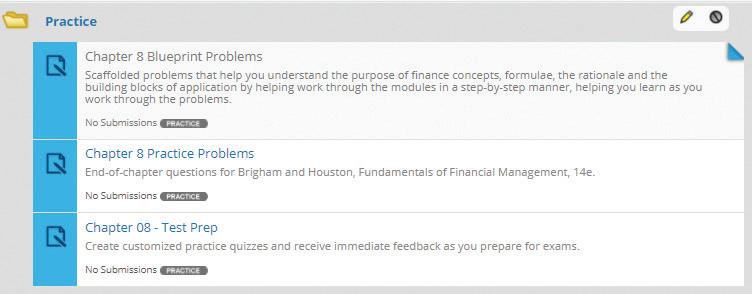

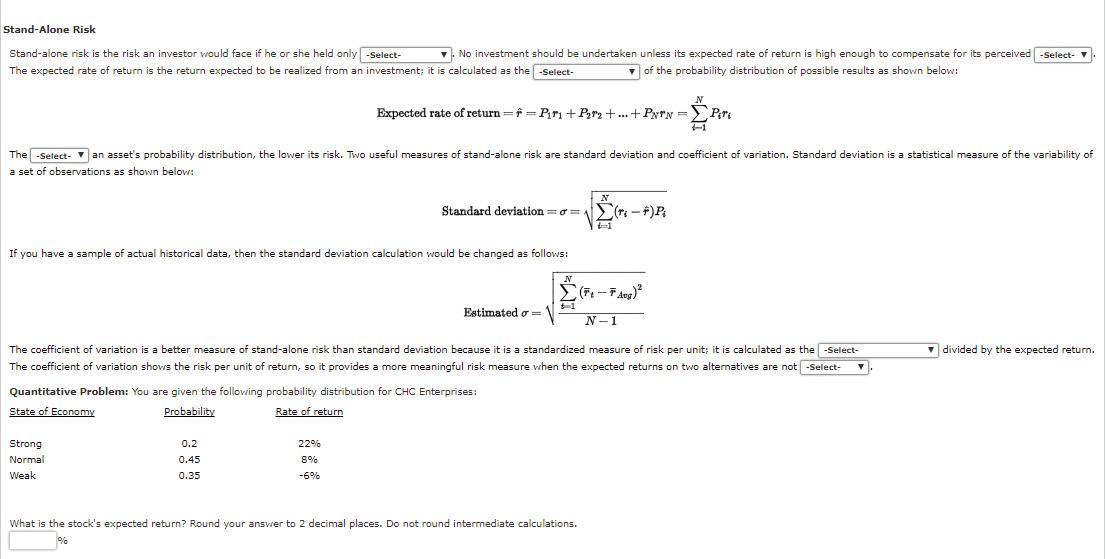

p ractic E p robl E ms

All of the end-of-chapter problems are available in algorithmic format for either student practice of applying content presented in the chapter or alternative graded assignment. MindTap is a highly customizable assessment delivery platform, so you can pick and choose from a large bank of algorithmic problem sets to assign to your students.

b lu E print p ractic E p robl E ms

Blueprint Practice Problems combine conceptual and applicationdriven problems with a tutorial emphasis. Students will know with certainty their level of competency for every chapter, which will improve course outcomes.

g rad E d h om E work

MindTap offers an assignable, algorithmic homework tool that is based on our proven and popular Aplia product for Finance. These homework problems include rich explanations and instant grading, with opportunities to try another algorithmic version of the problem to bolster confidence with problem solving.

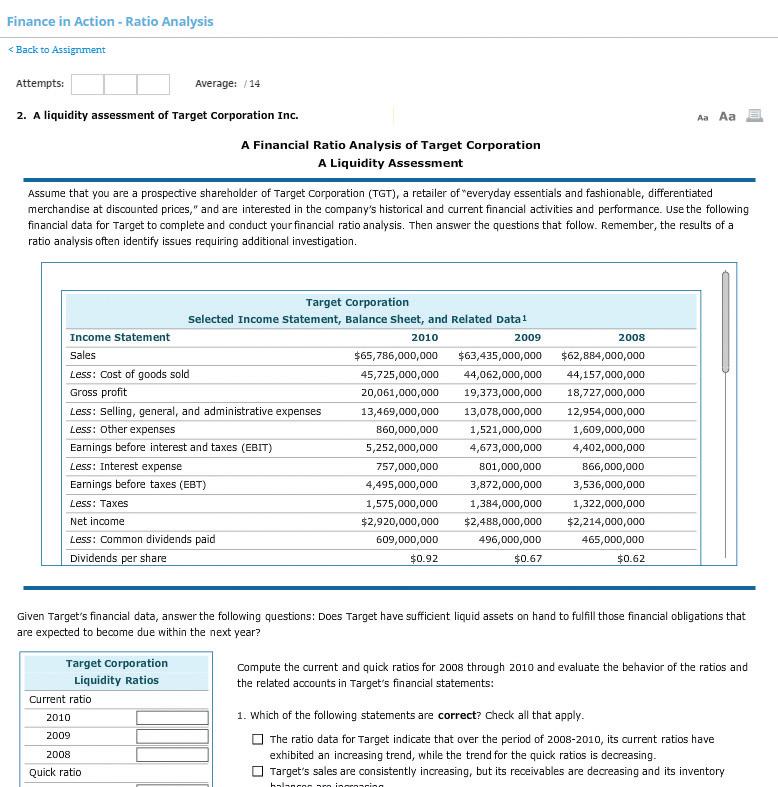

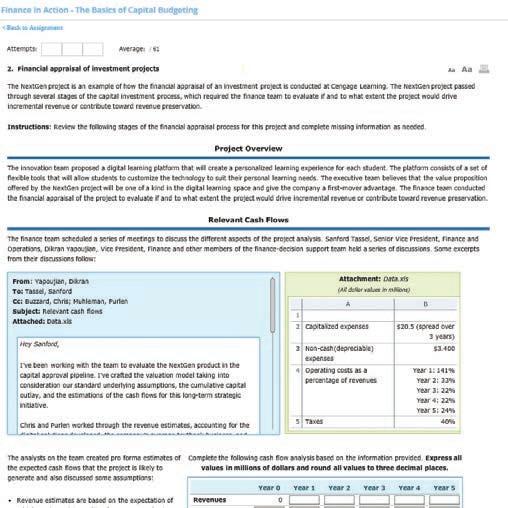

Financ E i n action c as E s

MindTap offers a series of Finance in Action analytical cases that assess students’ ability to perform higher-level problem solving and critical thinking/decision making.

tE sting

Mindtap offers the ability to modify existing assignments and to create new assignments by adding questions from the Test Bank.

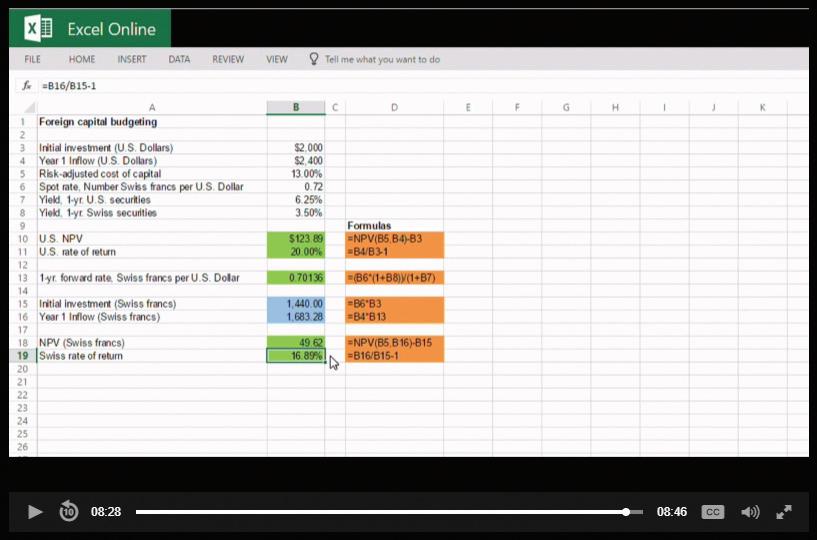

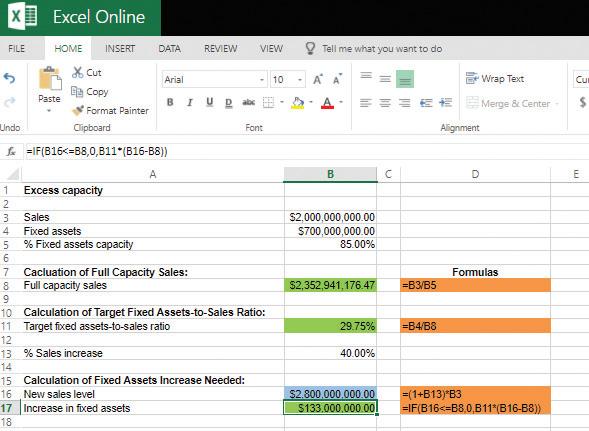

Building valuable Excel skills for future business careers while making

data-driven decisions

Cengage Learning and Microsoft have partnered in MindTap to provide students with a uniform, authentic Excel assignment experience. It provides instant feedback, built-in video tips, and easily accessible spreadsheet work. These features allow you to spend more time teaching finance applications and less time teaching and troubleshooting Excel.

These new algorithmic activities offer pre-populated data directly in Microsoft Excel Online, which runs seamlessly on all major platforms and browsers. Students each receive their own version of the problem data in order to use Excel Online to perform the necessary financial analysis calculations. Their work is constantly saved in Cengage cloud storage as part of homework assignments in MindTap. It’s easily retrievable so students can review their answers without cumbersome file management and numerous downloads/uploads.

Access to Excel Online as used in these activities is completely free for students as part of the MindTap course for Intermediate Financial Management, 13e. It is not in any way connected to personal Office 365 accounts/ local versions of Excel, nor are Microsoft accounts required to complete these activities in MindTap.

Microsoft Excel Online activities are aimed at meeting students where they are with unparalleled support and immediate feedback.

Microsoft Excel Online activities aimed at meeting students where they are with unparalleled support and immediate feedback

c alculation

s t E ps and Exc E l s olutions

Each activity offers configurable displays that include the correct answers, the manual calculation steps, and an Excel solution (with suggested formulas) that matches the exact version of the problem the student received. Students can check their work against the correct solution to identify improvement areas. Instructors always have access to review the student’s answers and Excel work from the MindTap progress app to better assist in error analysis and troubleshooting.

Exc E l v id E o t ips

Each activity includes a walkthrough video of a similar problem being worked in Excel Online to offer suggested formulas to use for solving the problem. It also offers tips and strategies, which assist in understanding the underlying financial concepts while working within Excel.

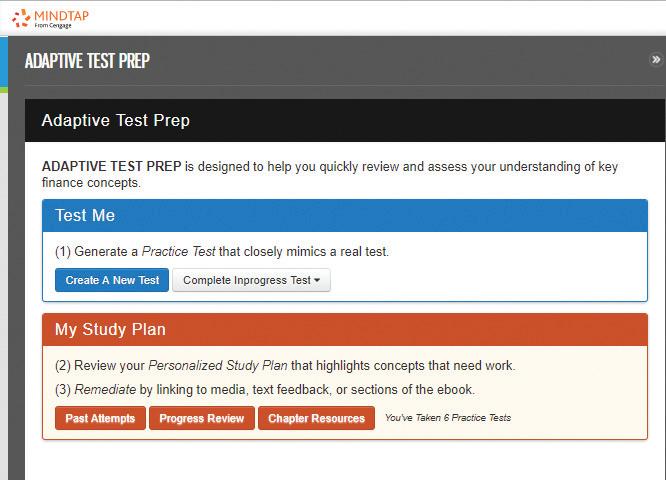

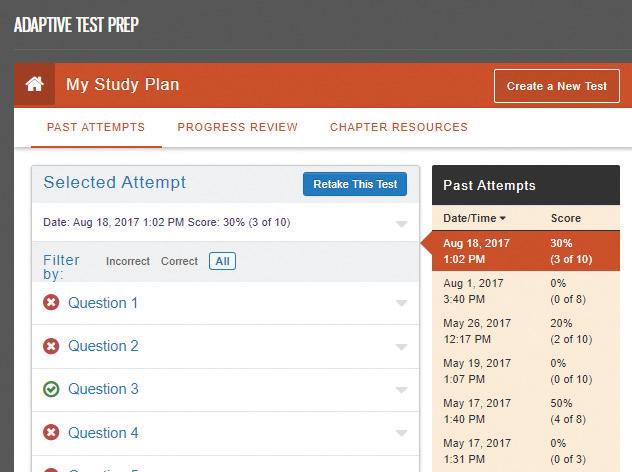

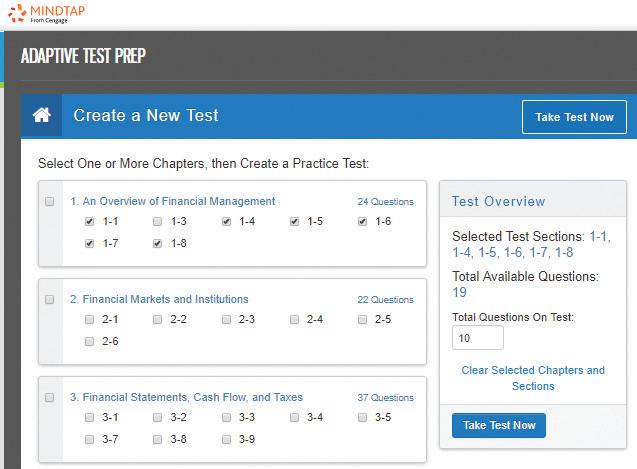

Help students prepare for exam success with Adaptive Test Prep, only available in MindTap

a daptiv E wh E r E it counts

The new Adaptive Test Prep App helps students prepare for test success by allowing them to generate multiple practice tests across chapters until they have confidence they have mastered the material.

The adaptive test program grades practice tests and indicates the areas that have or have not been mastered. Students are presented with an Adaptive Study Plan that takes them directly to the pertinent pages in the text where the practice question materials are referenced.

F EE dback is kE y

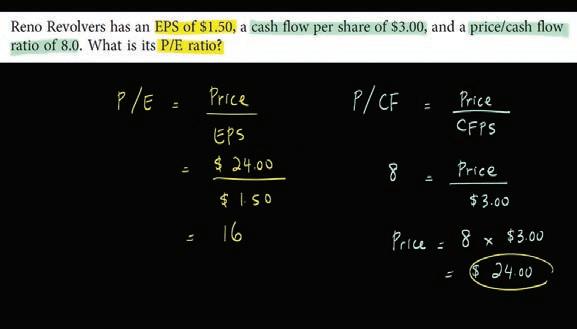

Students also receive robust explanations of the problems to assist in further understanding. Many of the quantitative test questions feature video feedback that offers students step-by-step instruction to reinforce their understanding and bolster their confidence.

Getting Down the Basics

is Important

In order for you to take students further into the applications of finance, it’s important that they have a firm handle on the basic concepts and methods used. In MindTap for Intermediate Financial Management, we provide students with just-in-time tools that—coupled with your guidance—ensure that they build a solid foundation.

p r E paring F or Financ E

Students are more confident and prepared when they have the opportunity to brush up on their knowledge of the prerequisite concepts required to be successful in finance. Tutorials/problems are available to review prerequisite concepts that students should know. Topics covered include Accounting, Economics, Mathematics, and Statistics, as well as coverage of various Financial Calculators and Excel.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT TO ME?

For many students, the idea of taking finance is intimidating. Beyond that, students report that they become more engaged with the course material when they see its relevance in business. The “Why is this important to me?” activity asks the student to complete a short selfassessment activity to demonstrate how they may already have personal knowledge about the important finance concepts they will learn in the chapter material. It is intended to help the student, especially the non-finance major, better understand the relevance in the financial concepts they will learn.

conc E pt c lips

Embedded throughout the new interactive MindTap Reader, Concept Clips present key finance topics to students in an entertaining and memorable way via short animated video clips. These video animations provide students with auditory and visual representation of the important terminology for the course.

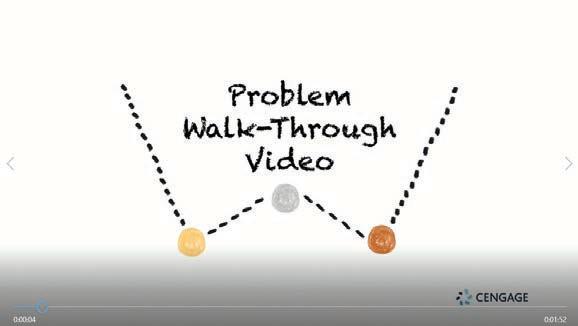

p robl E m walk- t hrough vid E os

Embedded in the interactive MindTap Reader and linked to select problems in MindTap, Problem Walk-Through Videos provide step-by-step instructions designed to walk students through solving a problem from start to finish. Students can play and replay the tutorials as they work through homework assignments or prepare for quizzes and tests—almost as though they had you by their side the whole time. Ideal for homework, study outside the classroom, or distance learning, Problem Walk-Through Videos extend your reach to give students extra instructional help whenever and wherever it’s most useful.

Customizable Course and Mobile On-the-Go study tools based on YOUR Needs

MindTap for Intermediate Financial Management, 13e offers features that allow you to customize your course based on the topics you cover.

lE arning path c ustomization

The learning path is structured by chapter so you can easily hide activities you wish to not cover, or change the order to better align with your course syllabus. RSS feeds and YouTube links can easily be added to the learning path or embedded directly within the MindTap Reader.

MindTap Mobile Empower students to learn on their terms—anytime, anywhere, on- or off-line.

m indtap e r E ad E r

Provides Convenience

Students can read their full course eBook on their smartphone. This means they can complete reading assignments anyplace, anytime. They can take notes, highlight important passages, and have their text read aloud, whether they are on- or off-line.

Flashcards and Quizzing

Cultivate Confidence and Elevate Outcomes

Students have instant access to readymade flashcards specific to their course. They can also create flashcards tailored to their own learning needs. Study games present a fun and engaging way to encourage recall of key concepts. Students can use pre-built quizzes or generate a self-quiz from any flashcard deck.

n oti F ications

Keep Students Connected

Students want their smartphones to help them remember important dates and milestones— for both the social and academic parts of their lives. The MindTap Mobile App pushes course notifications directly to them, making them more aware of what’s ahead with:

Due date reminders

Changes to activity due dates, score updates, and instructor comments

Messages from their instructor

Technical announcements about the platform

t h E g rad E book

Keep Students Motivated Students can instantly see their grades and how they are doing in the course. If they didn’t do well on an assignment, they can implement the flashcards and practice quizzes for that chapter.

LMS Integration

Cengage’s LMS Integration is designed to help you seamlessly integrate our digital resources within your institution’s Learning Management System (LMS).

LMS integration is available with the Learning Management Systems instructors use most. Our integrations work with any LMS that supports IMS Basic LTI Open Standards. Enhanced features, including grade synchronization, are the result of active collaborations with our LMS partners.

c r E at E a s E aml E ss us E r E xp E ri E nc E

With LMS Integration, your students are ready to learn on the first day of class. In just a few simple steps, both you and your students can access Cengage resources using a LMS login.

cont E nt customization with d EE p linking

Focus student attention on what matters most. Use our Content Selector to create a unique learning path that blends your content with links to learning activities, assignments, and more.

automatic grad E synchronization*

Need to have your course grades recorded in your LMS gradebook? No problem. Simply select the activities you want synched, and grades will automatically be recorded in your LMS gradebook.

* Grade synchronization is currently available with Blackboard, BrightSpace (powered by D2L), Canvas, and Angel 8.

WeB CHaPters & WeB extensions

students: Access the Web Chapters and Web Extensions by visiting www .cengagebrain.com, searching ISBN 9781285850030, and clicking “Access Now” under “Study Tools” to go to the student textbook companion site.

instructors: Access the Web Chapters, Web Extensions, and other instructor resources by going to www.cengage.com/login, logging in with your faculty account username and password, and using ISBN 9781285850030 to search for and to add resources to your account “Bookshelf.”

Preface xxvi Part I Fundamental ConCepts oF

1

1 An Overview of Financial Management and the Financial Environment 2

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 3

i ntroduction 3

How to u se this text 4

the Corporate l ife Cycle 4

Governing a Corporation 10

Box: Be Nice with a B-Corp 12

Box: Taxes and Whistleblowing 14

a n o verview of Financial m arkets 14

Claims on Future Cash Flows: types of Financial s ecurities 16

Claims on Future Cash Flows: the r equired r ate of r eturn (the Cost of m oney) 21

Financial m arkets 26

o verview of the u. s. s tock m arkets 29

trading in the m odern s tock m arkets 31

Finance and the Great r ecession of 2007 40

Box: Anatomy of a Toxic Asset 47

the Big p icture 51

e-Resources 52

Summary 52

2 Risk and Return: Part I 56

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 56

i nvestment r eturns and r isk 57

Box: Intrinsic Value, Risk, and Return 58

m easuring r isk for d iscrete d istributions 59

r isk in a Continuous d istribution 63

Box: What Does Risk Really Mean? 65

u sing Historical d ata to e stimate r isk 65

Box: The Historic Trade-Off Between Risk and Return 68

r isk in a portfolio Context 69

the r elevant r isk of a s tock: the Capital a sset p ricing m odel (C apm ) 73

Box: The Benefits of Diversifying Overseas 80

the r elationship between r isk and r eturn in the Capital a sset p ricing m odel 81

the e fficient m arkets Hypothesis 89

Box: Another Kind of Risk: The Bernie Madoff Story 90

the Fama-French three-Factor m odel 94

Behavioral Finance 99

the C apm and m arket e fficiency: i mplications for Corporate m anagers and i nvestors 102

Summary 103

3 Risk and Return: Part II 112

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 112

Box: Intrinsic Value, Risk, and Return 113

e fficient portfolios 114

Choosing the o ptimal portfolio 118

the Basic a ssumptions of the Capital a sset p ricing m odel 122

the Capital m arket l ine and the s ecurity m arket l ine 123

Box: Skill or Luck? 128

Calculating Beta Coefficients 128

e mpirical tests of the C apm 137

a rbitrage p ricing theory 140

Summary 143 4 Bond Valuation 149

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 149

Box: Intrinsic Value and the Cost of Debt 150

Who i ssues Bonds? 150

Box: Betting With or Against the U.S. Government: The Case of Treasury Bond

Credit Default Swaps 152

Key Characteristics of Bonds 152

Bond Valuation 157

Changes in Bond Values o ver time 162

Box: Chocolate Bonds 165

Bonds with s emiannual Coupons 165

Bond Yields 166

the p re- tax Cost of d ebt: d eterminants of m arket

i nterest r ates 170

the r isk-Free i nterest r ate: n ominal (r rF) and r eal (r*) 171

the i nflation p remium ( ip ) 172

the m aturity r isk p remium ( mrp ) 175

the d efault r isk p remium ( drp ) 178

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 180

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 182

Box: The Few, the Proud, the . . . AAARated Companies! 184

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 185

the l iquidity p remium ( lp ) 185

the term s tructure of i nterest r ates 186

Financing with Junk Bonds 188

Bankruptcy and r eorganization 188

Summary 190

5 Financial Options 199

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 199

Box: The Intrinsic Value of Stock Options 200

o verview of Financial o ptions 200

Box: Financial Reporting for Employee Stock Options 204

the s ingle- period Binomial o ption p ricing a pproach 204

the s ingle- period Binomial o ption p ricing

Formula 210

the multi-period Binomial option pricing model 213

the Black-scholes option pricing model ( opm ) 215

Box: Taxes and Stock Options 221

the Valuation of p ut o ptions 222

a pplications of o ption p ricing in Corporate Finance 224

Summary 227

6 Accounting for Financial

Management 231

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 231

Box: Intrinsic Value, Free Cash Flow, and Financial Statements 232

Financial s tatements and r eports 233 the Balance s heet 233

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 237

the i ncome s tatement 237

s tatement of s tockholders’ e quity 240

Box: Financial Analysis on the Web 241

s tatement of Cash Flows 241

Box: Filling in the GAAP 245

n et Cash Flow 245

Free Cash Flow: the Cash Flow a vailable for d istribution to i nvestors 246

Box: Sarbanes-Oxley and Financial Fraud 252

performance e valuation 255

the Federal i ncome tax s ystem 261

Box: When It Comes to Taxes, History Repeats and Repeals Itself! 263

Summary 267

7 Analysis of Financial Statements 279

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 279

Box: Intrinsic Value and Analysis of Financial Statements 280

Financial a nalysis 281 l iquidity r atios 282

a sset m anagement r atios 285

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 288

d ebt m anagement r atios 289

p rofitability r atios 293

Box: The World Might Be Flat, but Global Accounting Is Bumpy! The Case of IFRS versus FASB 294

m arket Value r atios 296

trend a nalysis, Common s ize a nalysis, and percentage Change a nalysis 300

tying the r atios together: the d u pont e quation 303

Comparative r atios and Benchmarking 304

u ses and l imitations of ratio analysis 306

Box: Ratio Analysis on the Web 307

l ooking beyond the n umbers 307

Summary 308

Part ii

Corporate Valuation

321

8 Basic Stock Valuation 322

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 322

Box: Corporate Valuation and Stock Prices 323

l egal r ights and p rivileges of Common

s tockholders 324

types of Common s tock 325

s tock m arket r eporting 326

Valuing Common s tocks— i ntroducing the Free Cash Flow (FCF) Valuation m odel 327

the Constant Growth m odel: Valuation When

e xpected Free Cash Flow Grows at a Constant r ate 332

the m ultistage m odel: Valuation when

e xpected s hort- term Free Cash Flow Grows at a n onconstant r ate 335

a pplication of the FCF Valuation m odel to m icro d rive 339

d o s tock Values r eflect l ong- term or s hort- term

Cash Flows? 347

Value-Based m anagement: u sing the Free Cash Flow Valuation m odel to i dentify Value d rivers 348

Why a re s tock p rices s o Volatile? 351

Valuing Common s tocks with the d ividend Growth m odel 352

the m arket m ultiple m ethod 359

Comparing the FCF Valuation m odel, the d ividend Growth m odel, and the m arket m ultiple m ethod 360

p referred s tock 362

Summary 363

9 Corporate Valuation and Financial

Planning 375

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 375

Box: Corporate Valuation and Financial Planning 376

o verview of Financial p lanning 377

Financial p lanning at m icro d rive i nc. 378

Forecasting o perations 379

e valuating m icro d rive’s s trategic i nitiatives 385

p rojecting m icro d rive’s Financial s tatements 387 a nalysis and s election of a s trategic p lan 392 the CF o ’s m odel 395

a dditional Funds n eeded ( a F n ) e quation m ethod 396

Forecasting When the r atios Change 400 Summary 404

10 Corporate Governance 416

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 416

Box: Corporate Governance and Corporate Valuation 417

a gency Conflicts 417

Corporate Governance 421

Box: Would the U.S. Government Be an Effective Board Director? 425

Box: The Dodd-Frank Act and “Say on Pay” 428

Box: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and Corporate Governance 429

Box: International Corporate Governance 432

e mployee s tock o wnership p lans ( esop s) 434

Summary 437

11 Determining the Cost of Capital 440

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 440

Box: Corporate Valuation and the Cost of Capital 441

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital 442

Choosing Weights for the Weighted Average Cost of Capital 443

After-Tax Cost of Debt: r d(1 T) and r std(1 T) 445

Box: How Effective Is the Effective Corporate Tax Rate? 448

Cost of Preferred Stock, r ps 451

Cost of Common Stock: The Market Risk Premium, RP M 452

Using the CAPM to Estimate the Cost of Common Stock, r s 456

Using the Dividend Growth Approach to Estimate the Cost of Common Stock 459

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) 461

Box: Global Variations in the Cost of Capital 463

Adjusting the Cost of Equity for Flotation Costs 464

Privately Owned Firms and Small Businesses 466

The Divisional Cost of Capital 468

Estimating the Cost of Capital for Individual Projects 470

Managerial Issues and the Cost of Capital 471 Summary 473

Part III

PROjECT VAlUATIOn 485

12 Capital Budgeting: Decision Criteria 486

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 486

Box: Corporate Valuation and Capital Budgeting 487

An Overview of Capital Budgeting 487

The First Step in Project Analysis 489

n et Present Value ( n PV) 490

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) 493

Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) 500

Profitability Index (PI) 503

Payback Period 504

How to Use the Different Capital Budgeting Methods 506

Other Issues in Capital Budgeting 509 Summary 516

13 Capital Budgeting: Estimating Cash Flows and Analyzing Risk 527

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 527

Box: Project Valuation, Cash Flows, and Risk Analysis 528

Identifying Relevant Cash Flows 528

Analysis of an Expansion Project 533

Box: Mistakes in Cash Flow Estimation

Can Kill Innovation 541

Risk Analysis in Capital Budgeting 542

Measuring Stand-Alone Risk 543

Sensitivity Analysis 544

Scenario Analysis 547

Monte Carlo Simulation 551

Project Risk Conclusions 554

Replacement Analysis 555

Real Options 557

Phased Decisions and Decision Trees 559

Summary 563

Appendix 13A Tax Depreciation 576

14 Real Options 579

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 580

Valuing Real Options 580

The Investment Timing Option: An Illustration 581

The Growth Option: An Illustration 592

Concluding Thoughts on Real Options 598 Summary 599

15 Distributions to Shareholders: Dividends and Repurchases 606

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 606

An Overview of Cash Distributions 607

Box: Uses of Free Cash Flow: Distributions to Shareholders 608

p rocedures for Cash d istributions 610

Cash d istributions and Firm Value 614

Clientele e ffect 617

s ignaling Hypothesis 619

i mplications for d ividend s tability 620

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 621

s etting the target d istribution l evel: the r esidual d istribution m odel 622

the r esidual d istribution m odel in p ractice 624

a tale of two Cash d istributions: d ividends versus s tock r epurchases 625

the pros and Cons of dividends and repurchases 635

Box: Dividend Yields around the World 636

o ther Factors i nfluencing d istributions 637

s ummarizing the d istribution policy d ecision 638

s tock s plits and s tock d ividends 640

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 641

d ividend r einvestment p lans 643

Summary 644

16 Capital Structure Decisions 652

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 652

Box: Corporate Valuation and Capital Structure 653

a n o verview of Capital s tructure 654

Business r isk and Financial r isk 655

Capital s tructure theory: the m odigliani and m iller

m odels 660

Box: Yogi Berra on the MM Proposition 663

Capital s tructure theory: Beyond the m odigliani and m iller m odels 665

Capital s tructure e vidence and i mplications 670

e stimating the o ptimal Capital s tructure 675

a natomy of a r ecapitalization 682

Box: The Great Recession of 2007 686

r isky d ebt and e quity as an o ption 687

m anaging the m aturity s tructure of d ebt 690

Summary 693

17 Dynamic Capital Structures and Corporate Valuation 701

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 701

Box: Corporate Valuation and Capital Structure Decisions 702

the a djusted p resent Value ( ap V)

a pproach 703

the m odigliani and m iller m odels 706

the Compressed a djusted p resent Value (C ap V)

m odel 707

the Free Cash Flow to e quity (FCF e )

m odel 709

m ultistage Valuation When the Capital s tructure is s table 710

i llustration of the three Valuation a pproaches for a Constant Capital s tructure 714

a nalysis of a d ynamic Capital s tructure 720

Summary 722

Part V taC tiC al FinanCinG deCisions 727

18 Initial Public Offerings, Investment Banking, and Capital Formation 728

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 728

the Financial l ife Cycle of a s tart- u p Company 729

the d ecision to Go p ublic 730

the p rocess of Going p ublic: a n i nitial p ublic o ffering 732

e quity Carve- o uts: a s pecial type of ipo 744

o ther Ways to r aise Funds in the Capital m arkets 745

Box: Where There’s Smoke, There’s Fire 750

i nvestment Banking a ctivities 753

Box: What Was the Role of Investment Banks? 755

the d ecision to Go p rivate 756

Summary 758

19 Lease Financing 765

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 765

Types of Leases 766

Tax Effects 769

Financial Statement Effects 770

Evaluation by the Lessee 773

Evaluation by the Lessor 778

Other Issues in Lease Analysis 781

Box: What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You! 782

Box: Lease Securitization 784

Other Reasons for Leasing 785 Summary 787

20 Hybrid Financing: Preferred Stock, Warrants, and Convertibles 794

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 794

Preferred Stock 795

Box: The Romance Had No Chemistry, but It Had a Lot of Preferred Stock! 797

Box: Hybrids Aren’t Only for Corporations 799

Warrants 801

Convertible Securities 807

A Final Comparison of Warrants and Convertibles 815

Reporting Earnings When Warrants or Convertibles Are Outstanding 816 Summary 817

21 Supply Chains and Working Capital Management 826

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 826

Box: Corporate Valuation and Working Capital Management 827

Overview of Supply Chain Management 828

Using and Financing Operating Current Assets 830

The Cash Conversion Cycle 834

Box: Some Firms Operate with Negative Working Capital! 840

Inventory Management 840

Receivables Management 842

Box: Supply Chain Finance 844

Accruals and Accounts Payable (Trade Credit) 846

Box: A Wag of the Finger or Tip of the Hat? The Colbert Report and Small Business Payment Terms 847

The Cash Budget 850

Cash Management and the Target Cash Balance 854

Box: Use It or Lose Part of It: Cash Can Be Costly! 855

Cash Management Techniques 856

Box: Your Check Isn’t in the Mail 859

Managing Short-Term Investments 860

Short-Term Bank Loans 861

Commercial Paper 865

Use of Security in Short-Term Financing 866 Summary 867

22 Providing and Obtaining Credit 880

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 880

Credit Policy 881

Monitoring Receivables with the Uncollected Balances Schedule 884

Analyzing Proposed Changes in Credit Policy 888

Analyzing Proposed Changes in Credit Policy: Incremental Analysis 891

The Cost of Bank Loans 898

Choosing a Bank 902 Summary 904

23 Other Topics in Working Capital Management 915

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 915

The Concept of Zero Working Capital 916

Setting the Target Cash Balance 917

Inventory Control Systems 923

Accounting for Inventory 924

the e conomic o rdering Quantity ( eo Q)

m odel 927

eo Q m odel e xtensions 934

Summary 940

Part V ii

speCial topiCs 945

24 Enterprise Risk Management 946

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 946

Box: Corporate Valuation and Risk Management 947

r easons to m anage r isk 948

a n o verview of e nterprise r isk

m anagement 950

a Framework for e nterprise r isk

m anagement 953

Categories of r isk e vents 956

Foreign e xchange (FX) r isk 958

Commodity p rice r isk 959

i nterest r ate r isk 964

Box: The Game of Truth or LIBOR 970

p roject s election r isks 973

m anaging Credit r isks 976

r isk and Human s afety 979

Summary 980

25 Bankruptcy, Reorganization, and Liquidation 985

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 985

Financial d istress and i ts Consequences 986

i ssues Facing a Firm in Financial d istress 988

s ettlements without Going through Formal Bankruptcy 989

Federal Bankruptcy l aw 991

r eorganization in Bankruptcy (Chapter 11 of Bankruptcy Code) 992

l iquidation in Bankruptcy 1003

Box: A Nation of Defaulters? 1007

a natomy of a Bankruptcy: transforming the G m Corporation into the G m Company 1008

o ther m otivations for Bankruptcy 1010

s ome Criticisms of Bankruptcy l aws 1010

Summary 1011

26 Mergers and Corporate Control

1020

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 1020

r ationale for m ergers 1021

types of m ergers 1024

l evel of m erger a ctivity 1025

Hostile versus Friendly takeovers 1026

m erger r egulation 1027

o verview of m erger a nalysis 1029

e stimating a target’s Value 1030

s etting the Bid p rice 1034

Who Wins: the e mpirical e vidence 1036

the r ole of i nvestment Bankers 1038

o ther Business Combinations 1039

d ivestitures 1041

tax treatment of m ergers 1042

Financial r eporting for m ergers 1046

Box: Tempest in a Teapot? 1048

Summary 1049

27 Multinational Financial Management 1056

Beginning-of-Chapter Questions 1056

Box: Corporate Valuation in a Global Context 1057

m ultinational, or Global, Corporations 1058

m ultinational versus d omestic Financial

m anagement 1059

Box: Meet Me at the Car Wash 1060

e xchange r ates 1061

the Fixed e xchange r ate s ystem 1067

Floating e xchange r ates 1067

Government i ntervention in Foreign e xchange

m arkets 1073

o ther e xchange r ate s ystems: n o l ocal Currency, pegged r ates, and m anaged Floating r ates 1074

trading in Foreign e xchange: s pot r ates and Forward r ates 1078

Interest Rate Parity 1079

Purchasing Power Parity 1082

Box: Hungry for a Big Mac? Go to Ukraine! 1083

Inflation, Interest Rates, and Exchange Rates 1083

International Money and Capital Markets 1084

Box: Stock Market Indices around the World 1087

Multinational Capital Budgeting 1090

Box: Death and Taxes 1091

International Capital Structures 1095

Multinational Working Capital Management 1097

Summary 1100

APPEndIxES

Appendix A Values of the Areas under the Standard Normal Distribution Function 1109

Appendix B Answers to End-of-Chapter Problems 1111

Appendix C Selected Equations 1121

GloSSA ry 1139

NAmE INDE x 1187

SuBjEC t INDE x 1191

WEB CHAPtErS & WEB E xtENSIoNS

Students: Access the Web Chapters and Web Extensions by visiting www.cengagebrain.com, searching ISBn 9781337395083, and clicking “Access now” under “Study Tools” to go to the student textbook companion site.

Instructors: Access the Web Chapters, Web Extensions, and other instructor resources by going to www .cengage.com/login , logging in with your faculty account username and password, and using ISB n 9781337395083 to search for and to add resources to your account “Bookshelf.”

Web Chapters

28 Time Value of Money

29 Basic Financial Tools: A Review

30 Pension Plan Management

31 Financial Management in n ot-for-Profit Businesses

Web Extensions

Web Extension 1A An Overview of d erivatives

Web Extension 1B An Overview of Financial Institutions

Web Extension 2A Continuous Probability d istributions

Web Extension 2B Estimating Beta with a Financial Calculator

Web Extension 4A A Closer Look at Zero Coupon, Other OI d Bonds, and Premium Bonds

Web Extension 4B A Closer Look at TIPS: Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities

Web Extension 4C A Closer Look at Bond Risk: d uration

Web Extension 4 d The Pure Expectations Theory and Estimation of Forward Rates

Web Extension 6A The Federal Income Tax System for Individuals

Web Extension 8A d erivation of Valuation Equations

Web Extension 11A The Cost of Equity in the nonconstant dividend Growth Model with Repurchases

Web Extension 12A The Accounting Rate of Return (ARR)

Web Extension 13A Certainty Equivalents and Risk-Adjusted d iscount Rates

Web Extension 14A The Abandonment Real Option

Web Extension 14B Risk- n eutral Valuation

Web Extension 16A d egree of Leverage

Web Extension 16B Capital Structure Theory: Arbitrage Proofs of the Modigliani-Miller Theorems

Web Extension 17A Projecting Consistent d ebt and Interest Expenses

Web Extension 17B Bond Refunding

Web Extension 18A Rights Offerings

Web Extension 19A Percentage Cost Analysis

Web Extension 19B Leasing Feedback

Web Extension 19C Leveraged Leases

Web Extension 19D Accounting for Leases

Web Extension 20A Calling Convertible Issues

Web Extension 21A Secured Short-Term Financing

Web Extension 21B Supply Chain Finance

Web Extension 25A Multiple Discriminant Analysis

Web Extension 28A The Tabular Approach

Web Extension 28B Derivation of Annuity Formulas

Web Extension 28C Continuous Compounding

Preface

web

students: Access the Intermediate Financial Management 13e companion site and online student resources by visiting www.cengagebrain .com, searching ISBN 9781285850030 and clicking “Access Now” under “Study Tools” to go to the student textbook companion site.

instructors: Access the Intermediate Financial Management 13e companion site and instructor resources by going to www.cengage .com, logging in with your faculty account username and password, and using ISBN 9781285850030 to reach the site through your account “Bookshelf.”

Much has happened in finance recently. Years ago, when the body of knowledge was smaller, the fundamental principles could be covered in a one-term lecture course and then reinforced in a subsequent case course. This approach is no longer feasible. There is simply too much material to cover in one lecture course.

As the body of knowledge expanded, we and other instructors experienced increasing difficulties. Eventually, we reached these conclusions:

The introductory course should be designed for all business students, not just for finance majors, and it should provide a broad overview of finance. Therefore, a text designed for the first course should cover key concepts but avoid confusing students by going beyond basic principles.

Finance majors need a second course that provides not only greater depth on the core issues of valuation, capital budgeting, capital structure, cost of capital, and working capital management but also covers such special topics as mergers, multinational finance, leasing, risk management, and bankruptcy.

This second course should also utilize cases that show how finance theory is used in practice to help make better financial decisions.

When we began teaching under the two-course structure, we tried two types of existing books, but neither worked well. First, there were books that emphasized theory, but they were unsatisfactory because students had difficulty seeing the usefulness of the theory and consequently were not motivated to learn it. Moreover, these books were of limited value in helping students deal with cases. Second, there were books designed primarily for the introductory MBA course that contained the required material, but they also contained too much introductory material. We eventually concluded that a new text was needed, one designed specifically for the second financial management course, and that led to the creation of Intermediate Financial Management, or IFM for short.

The Next Level: Intermediate Financial Management

In your introductory finance course, you learned basic terms and concepts. However, an intro course cannot make you “operational” in the sense of actually “doing” financial management. For one thing, introductory courses necessarily focus on individual chapters and even sections of chapters, and first-course exams generally consist of relatively simple problems plus short-answer questions. As a result, it is hard to get a good sense of how the various parts of financial management interact with one another. Second, there is not enough time in the intro course to allow students to set up and work out realistic problems, nor is there time to delve into actual cases that illustrate how finance theory is applied in practice.

Now it is time to move on. In Intermediate Financial Management, we first review materials that were covered in the introductory course, then take up new

material. The review is absolutely essential because no one can remember everything that was covered in the first course, yet all of the introductory material is essential for a good understanding of the more advanced material. Accordingly, we revisit topics such as the net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) methods, but now we delve into them more deeply, considering how to streamline and automate the calculations, how to obtain the necessary data, and how errors in the data might affect the outcome. We also relate the topics covered in different chapters to one another, showing, for example, how cost of capital, capital structure, dividend policy, and capital budgeting combine forces to affect the firm’s value.

Also, because spreadsheets such as Excel, not financial calculators, are used for most real-world calculations, students need to be proficient with spreadsheets so that they will be more marketable after graduation. Therefore, we explain how to do various types of financial analysis with Excel. Working with Excel has, in fact, two important benefits: (1) a knowledge of Excel is important in the workplace and the job market, and (2) setting up spreadsheet models and analyzing the results also provide useful insights into the implications of financial decisions.

Corporate Valuation as a Unifying Theme

Management’s goal is to maximize firm value. Job candidates who understand the theoretical underpinning for value maximization and have the practical skills to analyze business decisions within this context make better, more valuable employees. Our goal is to provide you with both this theoretical underpinning and a practical skill set. To this end we have developed several integrating features that will help you to keep the big picture of value maximization in mind while you are honing your analytical skills:

Every chapter starts off with a series of integrating Beginning of Chapter Questions that will help you place the material in the broader context of financial management.

Most chapters have a valuation graphic and description that show exactly how the material relates to corporate valuation.

Each chapter has a Mini Case that provides a business context for the material. Each chapter has an Excel spreadsheet Tool Kit that steps through all the calculations in the chapter.

Each chapter has a spreadsheet Build-a-Model that steps you through constructing an Excel model to work problems. We’ve designed these features and tools so that you’ll finish your course with the skills to analyze business decisions and the understanding of how these decisions impact corporate value.

Design of the Book

Based on more than 30 years working on Intermediate Financial Management and teaching the advanced undergraduate financial management course, we have concluded that the book should include the following features: Completeness. Because IFM is designed for finance majors, it should be selfcontained and suitable for reference purposes. Therefore, we specifically and

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Sayre places so much confidence in the power of this elastic tension to overcome contractions that he rarely resorts to tenotomy in the treatment of paralytic talipes. Hueter, however,180 considers tenotomy much the speediest, and therefore the most desirable, way of removing contractions.181

180 Loc. cit.

181 Loc. cit.

Seeligmüller quotes with approval Böttger's method for the treatment of deformities, where the weight of the body is utilized to stretch the retracted tendons. Thus, for talipes equino-varus an over-reduction is effected under ether, and the foot forced into a position of moderate calcaneo-valgus. In this position it is retained by the immediate application of a plaster or silica bandage. After this has hardened the child should be encouraged to walk in the mould, with the addition of felt shoes having a slanting sole that is thickened like a wedge at the inner side of the foot and strapped on like a skate. Then, during the act of walking the body tends to constantly force down the heel and thus stretch the retracted tendo Achillis, while the bandage and felt sole (acting like a splint) prevent the inner side of the foot from slipping up.

For talipes valgus the method is analogous, but the foot is forced into an equino-varus position, so that the tendo Achillis is artificially shortened, and ultimately becomes a rigid band, capable, in spite of the sural paralysis, of sustaining the heel.

A cause of relapse in talipes not unfrequently overlooked is the presence of even slight contractions of the hip- and knee-joints. These by shortening the limb tend to the production of equinus, since the foot points itself in order to reach the ground. These contractions, whose rigidity is far inferior to that induced by chronic arthritis, may be overcome by forced extension under ether or gradually by manipulations, or by the weight-and-pulley apparatus, applied in the recumbent position, as in morbus coxarius. The obvious objection to the latter method is the confinement in bed which it necessitates in a child enjoying at the time perhaps robust general health.

The contraction once overcome, the limb must be placed in apparatus which shall both maintain suitable extension and assist in supporting the trunk during station and locomotion. The latter purpose is effected, as in apparatus for chronic joint diseases, by transferring the weight of the body to steel splints running up each side of the limb, the outer one as far as a girdle which encircles the hips; the inner to a band surrounding the upper part of the thigh. Thus is extended the support which in paralysis limited to the leg-muscles is given by the steel splints inserted in the side of the club-foot shoes.

In the simplest form of apparatus locomotion is expected to be accomplished by the action of muscles inserted above the seat of the paralysis. Thus, when the muscles passing over the ankle-joint are paralyzed, the foot is moved as a dead weight by means of the quadriceps extensor, popliteus, and hamstring muscles inserted at the upper extremity of the leg. If the quadriceps cruris is paralyzed, the rotators of the thigh, ilio-psoas, sartorius, and adductor muscles, passing from the pelvis to the thigh, and which are so frequently intact in atrophic paralysis, are enabled to move the limb if the weight of the body is borne by steel splints, if these be light and properly jointed at the hip, knees, and ankle.182

182 Or the joint of the knee may be kept locked while the patient walks, when extension of the limb is mainly required, during both the active and passive movements of locomotion, the necessary flexion being supplied at the hip and ankle. By means of a key the knee-joint can be flexed during the sitting positions.

But an important aid to locomotion may be obtained from the artificial muscles, whose elastic tension is of such value in overcoming contractions. The quadriceps extensor, the most frequently paralyzed, may be supplemented by an India-rubber band and chain passing down the front of the thigh from a point on the pelvic girdle corresponding to the anterior iliac spine to a point on a leg-band, imitating the tibial insertion of the quadriceps tendon. Analogous bands stretched on the posterior aspect of the thigh simulate the hamstring muscles. When the external rotators are paralyzed, the artificial muscle must stretch from the pelvic girdle to a band encircling the upper part of the thigh.

The action of these muscles, apart from their elastic tension of repose, is thus explained by Duchenne: When any effort is made to move a

paralyzed limb, the intact antagonists to the paralyzed muscles contract; thus, the flexors of the leg. But this contraction, being constantly opposed by the elastic tension of the artificial quadriceps, is restrained and gradual, instead of being brusque, jerking, and excessive, as it otherwise would be. This is the first result obtained. In the second place, contraction of the antagonist having ceased, the artificial muscle which has been stretched returns upon itself in virtue of its elasticity, and restores the limb to the position of normal equilibrium.

For the act of walking, however, the artificial quadriceps would require to be made tense enough to resist flexion, and thus keep the limb in extension. An artificial anterior tibial muscle, however, would require to yield to the intact gastrocnemius while the heel was being raised from the floor; then its elastic force should be sufficient to retract the point of the foot in dorsal flexion during the pendulum movement which passively swings the leg forward. The tension of the artificial muscle should therefore be so adjusted that it can only be overcome by the active contraction of the gastrocnemius, and at the moment of greatest tension, immediately after stretching, it should be able to quite overcome the gastrocnemius, then relatively183 relaxed.

183 We say relatively, believing that the simultaneous contraction of antagonist muscles has been well established as a constant normal phenomenon.

The anterior tibial, gastrocnemius, and many other of the artificial muscles devised by Duchenne are still in use in the modified form given to them by Barwell. On the other hand, the action of the long peroneus in pronating the foot, and which Duchenne imitated by an elaborate artificial tendon following the exact course of the natural one, is to-day generally supplemented by the jointed shoe and laced bandage.

In paralysis of all the muscles surrounding a joint, when the limb is placid and no retractions by adapted atrophy have taken place, the artificial muscles can only serve to oppose the malpositions which are threatened from mechanical influences.

In the upper extremities prothetic apparatus has been principally used for progressive muscular atrophy. Paralysis of the wrist extensors is perhaps the only case in which the artificial muscle is required in anterior

poliomyelitis. A string may be necessary to support the arm in paralysis of the deltoid, to avert luxation of the humerus.

Duchenne's ingenuity did not shrink from the difficult task of supplementing the muscles of the trunk. This he did by inserting the elastic spirals in corsets in a direction following that of the muscles paralyzed. Thus, a unilateral paralysis of the sacro-lumbalis may be met by a spiral splint running up one side of the spine; below, to the lateral posterior portion of a pelvic girdle. In bilateral paralysis two springs are used to antagonize the action of the abdominal muscles.

In Barwell's apparatus for the trunk184 India-rubber bands are again substituted for spiral springs. No attempt is made to imitate the direction of muscles, but the force is applied in any direction required to antagonize the pressure producing the deformity.185

184 Especially designed for habitual scoliosis, but applicable also to the paralytic deformity

185 Volkmann (loc. cit., p. 778) thinks that the force of Barwell's India-rubber straps, whether for scoliosis or club-foot apparatus, is inadequate, and much inferior to metallic springs.

It is always important to remember the rarity of scoliosis caused by spinal paralysis of the trunk-muscles, and the much greater frequency with which this deformity occurs as a consequence of the paralytic shortening of a leg. A high shoe, equalizing the length of the lower extremities, is then the simple and efficient remedy.

In cases of long standing, even when the scoliosis is due to this cause, certain muscles on the concave side of the curve may become so retracted and rigid as to require tenotomy Before this operation it is necessary to put the rigid muscles on the stretch as much as possible; and this may be done, if necessary, by means of Sayre's hanging apparatus. After this operation the spine may be straightened out with ease—an important distinction from advanced habitual scoliosis, where the alteration in the shape of the vertebræ defeats all attempts at rectification. The position may be maintained by elastic straps or corsets and by removing the condition which has led to the deformity.

Seeligmüller criticises too unfavorably the entire system of elastic tension in the prophylaxis and treatment of paralytic deformities. He quotes Duchenne's admission, that in certain cases traction upon rigidly-retracted

tissues becomes insupportably painful, and must be abandoned. It is in these cases that tenotomy becomes an indispensable preliminary to the use of apparatus. Sayre insists that the necessity for tenotomy is indicated when pressure on the rigid muscle is followed by instantaneous spasmodic contraction in the affected or neighboring muscles. He declares that such contractions indicate reflex irritations, show that the muscle has undergone structural change, and that any attempt to stretch or lengthen it would be followed by an excess of irritation and pain.

This explanation can hardly be accepted, since muscles, whether imperfectly or not at all paralyzed, which from position and adapted atrophy have become retracted, have necessarily undergone structural changes. The greater these changes, the greater the diminution of reflex excitability; and in any muscle completely paralyzed and degenerated this is entirely lost. If, however, the afferent nerves retain enough vitality, if the muscle be slightly paralyzed or altogether intact, then irritation of its tendon by stretching may serve to excite contractions in the belly of the muscle. The possibility of such spinal reflexes is demonstrated by the now familiar phenomenon of the tendon reflex in various spinal diseases.186 The contractions must be painful from the impediments offered to the progress of the contracting nerve, and from the exaggeratedly vicious position into which they tend to force the limb. Under these circumstances prothetic apparatus must be deferred until section of the tendons has been made.

186 “Passive muscular tension excites tonic contraction in a muscle, and this action may, in abnormal conditions, be excessive, as in the myelitic contractions (so-called tendon reflexes).... The afferent nerves commence in the fibrous tissues of the muscle, and seem to be especially stimulated by extension” (Gowers, On Epilepsy, 1881, p. 97).

DISEASE OF ONE LATERAL HALF OF THE SPINAL CORD.

BY H. D. SCHMIDT, M.D.

SYNONYMS.—Unilateral lesion of the spinal cord; Spinal hemiplegia and hemiparaplegia; Unilateral spinal paralysis.

INTRODUCTION.—This disease remained unnoticed until twenty years ago, when Brown-Séquard, observing that certain lesions of the spinal cord were accompanied by symptoms resembling those which he witnessed in animals after section of one lateral half of the cord, recognized it as a special affection. Although some of the accompanying phenomena of such a section had likewise been observed by Stilling, Budge, Eigenbrodt, Tuerk, Schiff, Von Bezold, and Van Kempen,1 nevertheless this whole group of symptoms, as belonging to the same disease, was first clearly recognized and anatomically demonstrated by Brown-Séquard.2 According to this physiologist, a section or a destruction of a small portion of a lateral half of the spinal cord in its cervical region gives rise to the following phenomena: namely, on the injured side is observed a paralysis of voluntary motion, of the muscular sense, and of the blood-vessels; the latter, manifesting itself by a greater supply of blood and a higher temperature of the parts, may continue to exist for some years. There is, furthermore, an increased sensibility of the trunk and extremity to touch, prick, heat, cold, electricity, etc., owing to vasomotor paralysis, though in some cases a slight anæsthesia may exist in a limited zone above the hyperæsthetic part, and also in certain parts of the arm, breast, and neck. Besides these symptoms, vasomotor paralysis of the corresponding side of the face and of the eye, manifested by an elevated temperature and sensibility, partial closure of the eyelid, contracted pupil, slight contraction of some of the muscles of the face, etc., may also be present. On the opposite side of the injury an anæsthesia of all kinds of sensation, excepting the muscular sense, is observed in both extremities; there is also an

absence of motor paralysis. The anæsthesia on this side is owing to the decussation of the sensory nerves in the spinal cord.

1 Eckhard, “Physiologie des Nervensystems,” in Handbuch der Physiologie, edited by L. Hermann, 2d part of vol. ii. p. 165.

2 “On Spinal Hemiplegia,” Lancet, Nov 7, 21, and Dec. 12, 26, 1868, reported in Virchow and Hirsch's Jahresbericht for the year 1868, vol. ii. p. 37.

If the hemisection of the cord is made in the dorsal region, the functional disturbances are limited to that part of the body below the point of division, and a hemiparaplegia, or paralysis of the corresponding lower extremity, will be the result.

From these facts it will be readily understood that a lesion occurring in any portion of one lateral half of the spinal cord of man must be followed by some or all of the above-mentioned symptoms, and that the phenomena produced by physiological experiments on animals constitute, in reality, the pathological basis of unilateral spinal paralysis in man. They will be more clearly understood by calling to mind the course of the musculo-motor, vaso-motor, and sensitive tracts in the spinal cord. Thus, the musculo-motor tracts, after having descended to the crura cerebri, cross one another in the pyramids of the medulla oblongata and adjoining upper portion of the spinal cord, forming the so-called decussation of the pyramids; they then descend through the spinal cord to supply the muscles of the same side of the body.3 A section of one lateral half of the cord therefore causes motor paralysis on the same side. The vaso-motor tracts remain uncrossed, and pass, each, through one lateral half of the cord to supply the vessels on the same side; some regions of the body are stated to make an exception to this rule. According to Brown-Séquard, the sensitive tracts conducting the different kinds of sensation, with the exception of the muscular sense, on the contrary, cross over to the opposite half of the spinal cord soon after their entrance into it, and thence pursue their further course to the brain. A section of one lateral half of the cord, therefore, will be followed by a loss of sensation of touch, pain, heat, tickling, etc. on the other side of the body.

3

Though, in the majority of cases, a complete decussation of the motor tracts probably takes place in the pyramids, the researches of Flechsig have shown (Die Leitungsbahnen im Gehirn und Rückenmark des Menschen, p. 273) that there are a number of others in which the decussation is not complete, but where a part of these tracts passes to the spinal marrow uncrossed on the inner surface of the anterior white columns.

The symptoms above mentioned must of course vary according to the extent, the intensity, and the particular nature of the lesion, as well as the height at which it is located in the spinal cord.

DEFINITION.—The chief characters of unilateral spinal disease are motor paralysis, hemiplegia, or hemiparaplegia, paralysis of the muscular sense and of the blood-vessels on the side of the lesion, and paralysis of sensation with preservation of the muscular sense on the other side of the body These symptoms may vary, and be accompanied by other phenomena according to the particular seat, extent, and depth of the lesion.

SYMPTOMS.—According to the nature of the lesion, the symptoms of unilateral disease of the spinal cord may be developed suddenly, as, for instance, when caused by traumatic injuries; or in a gradual and slow manner, when they may be preceded by premonitory symptoms, such as vertigo, pain on the side of the lesion, etc. The most prominent clinical phenomena, as before mentioned, are motor paralysis on the side of the lesion, and anæsthesia on the opposite side of the body. The motor paralysis on the side of the lesion may, according to the seat of the latter, manifest itself in either the form of a hemiplegia or hemiparaplegia, and even extend in a light form to the opposite side of the body. In typical cases, however, in which the injury or disease is strictly confined to one lateral half of the cord, the motor power on the other side of the body remains entirely undisturbed. At the same time, the muscular sense on the injured side is paralyzed or considerably diminished, and in some cases (Fieber, Lanzoni, Allessandrini) the electro-muscular excitability also has been found lowered, while in others it has remained normal. There is furthermore observed, on the side of the lesion, a vaso-

motor paralysis, manifesting itself by a greater supply of blood to, and a higher temperature of, the paralyzed trunk and limbs, giving rise to an increase of sensibility (hyperæsthesia) of touch, prick, heat, cold, electricity, etc. in these parts. If the seat of the lesion is sufficiently high up in the cord, this paralysis extends, moreover, to the corresponding side of the face and eye, where it also causes an elevation of temperature, increase of sensibility, partial closure of the eyelid, contracted pupil, slight contraction of some of the muscles of the face, etc. In a number of cases at the boundary of the hyperæsthetic region a narrow anæsthetic zone is observed to exist on the breast, neck, or arm. This anæsthesia is owing to the division, at the level of the section, of some nerves of sensation on their way to the other half of the spinal cord. An increase of the reflex irritability of the tendons has in some cases (Erb, Schulz, Revillons) been observed, while in one case (Glaeser) the reflex was found to be absent. Swelling and œdema of the paralyzed limbs have also been met with (Glaeser), and in one case (Allessandrini) even swelling and pain in all the joints of the injured side were observed before death, while masses of coagulated blood in these joints, particularly in the knee, were revealed by the autopsy. The inflammatory affection of the knee-joint of the paralyzed leg has, moreover, been observed by Viguès, Joffroy, and Solomon.4 Frequently, atrophy of the paralyzed muscles takes place, especially in chronic cases. In one case (Fieber) even atrophy of the upper extremity of the uninjured side of the body was observed.

4 Erb, “Diseases of the Spinal Cord, etc.,” Cyclopædia of the Practice of Medicine, edited by H. v. Ziemssen, Amer. ed.

The most prominent symptoms observed on the side of the body opposite to the seat of the lesion are anæsthesia of every kind of sensation, preservation of the muscular sense, and absence of motor paralysis. Reflex action and electro-muscular contractility generally remain normal, though in one case (Fieber) the latter was found increased. Although the anæsthesia of the skin generally comprises every kind of sensation, three cases were observed (Fieber) in which the sensation of heat remained unimpaired, while

the electro-cutaneous sensibility appeared to be lost. As a general rule, there is no vaso-motor paralysis on the uninjured side, though in some cases (Erb, Allessandrini) an elevation of temperature has been observed.

Besides the above symptoms, some others, less characteristic in nature, are now and then observed in individual cases. They are painful sensations on one or the other side, or even simultaneously on both sides of the body, and also a feeling of constriction at the level of the lesion (Erb). Disturbances of the functions of the bowels or bladder are also met with, though in other cases they are absent.

P

ATHOLOGICAL

ANATOMY

.—The pathological changes taking place in the spinal cord of patients affected with unilateral spinal paralysis must vary in different cases according to the particular nature of the lesion giving rise to the characteristic symptoms. In those cases reported to have terminated by a gradual disappearance of the symptoms with or without therapeutic interference it is very probable that the exciting cause was a hyperæmia or a myelitis of a small portion of one lateral half of the spinal cord, sufficiently high in degree to impair the conducting power of the nerve-fibres passing through it. In some cases the myelitis may lead to a degeneration of the nerve-fibres, or even extend to the other half of the cord, and by calling forth additional symptoms render the case more complicated. In syphilitic cases the disease depends upon syphilitic deposits or neoplasms in the affected portion of the spinal cord; these cases, however, generally yield to treatment. In the same manner may circumscribed sclerosis give rise to the disease. Another cause may be found in the compression of the cord caused by meningeal tumors or by the fractured portions of some of the vertebræ. Chronic disease of the vertebral bones themselves (Pott's disease) may also, by encroaching upon the spinal cord, become an exciting cause.

The most typical cases, however, are those depending upon traumatic injuries, by which one lateral half of the spinal cord is forcibly divided. These lesions resemble in nature the division of the cord in the physiological experiments on animals, and are most

frequently caused by a stab from a knife penetrating to the cord through the intervertebral spaces.

DIAGNOSIS.—In those cases in which the symptoms of unilateral spinal paralysis appear soon after an external injury to the spine, it becomes obvious that the latter is the exciting cause. In cases of a more chronic character, in which the symptoms appear gradually, the nature of the exciting cause can only be correctly determined by the observation of certain collateral symptoms characteristic of such causes as might give rise to the symptoms of the disease in question. As regards the diagnostic symptoms of unilateral spinal paralysis themselves, they are sufficiently characteristic to be easily distinguished from those of other forms of hemiplegia or hemiparaplegia. Thus, cerebral hemiplegia may be distinguished from the disease under discussion by the sensory disturbances being either absent or on the same side as the paralysis; furthermore, by the one-sided paralysis of the face and of the tongue and by the affection of various cranial nerves. The hemiplegic form of spasmodic spinal paralysis is distinguished by the absence of sensory disturbance, etc. Lastly, hemiplegia depending upon lesion of one side of the cauda equina is distinguished from unilateral spinal disease by the paralysis and anæsthesia being confined to the same side, and by generally affecting certain nervous districts of the lower extremities.

PROGNOSIS.—In unilateral spinal lesions the prognosis depends obviously on the particular nature and intensity of the exciting cause. On the whole, there are quite a number of cases reported, even of traumatic origin, which have terminated favorably.

TREATMENT.—The treatment of unilateral spinal paralysis depends, like the prognosis, upon the nature of the exciting cause. The principles upon which it is to be pursued of course are the same as those upon which the treatment of the various lesions causing the disease—such as hyperæmia, myelitis, sclerosis, wound of the spinal cord, etc.—is based.

PROGRESSIVE LABIO-GLOSSO-LARYNGEAL PARALYSIS.

BY H. D. SCHMIDT, M.D.

SYNONYMS.—Chronic progressive bulbar paralysis; Progressive muscular paralysis of the tongue, soft palate, and lips.

HISTORY.—Although the particular group of symptoms constituting this disease must have been met with and known to the older medical observers, they were nevertheless first recognized as a special variety of paralysis in 1841 by Trousseau,1 who named the affection labio-glosso-laryngeal paralysis. But as the memorandum prepared by this distinguished physician at the time when, in consultation with a medical colleague, he had observed the particular symptoms of this affection, unfortunately remained unpublished, twenty years more elapsed before the first accurate and detailed description of the symptoms and progressive nature of this disease under the name of progressive muscular paralysis of the tongue, soft palate, and lips was rendered by Duchenne. The writings of this author directed at once the attention of other medical men to this disease, and since that time a large number of cases have been reported and discussed,2 while the microscopical examination accompanying the autopsies of many of them finally

revealed that the seat of the lesion giving rise to the phenomena of this disease was to be sought in the nervous nuclei of the medulla oblongata. Hence at the present time the pathology of this disease is thoroughly understood.

1 Clinique médicale de l'Hôtel Dieu de Paris, vol. ii. p. 334.

2 A very considerable number of cases of this disease, and discussions thereon, will be found reported in Virchow and Hirsch's Jahresbericht über die Leistungen und Fortschritte der Gesammten Medizin, for the years 1866-80, vol. ii., section “Krankheiten des Nervensystems.”

DEFINITION.—That form of labio-glosso-laryngeal paralysis to be treated in the following pages is characterized by a progressive paralysis and atrophy of the muscles of the tongue, lips, palate, pharynx, and larynx, interfering in a greater or lesser degree with the articulation of words and sounds and with the functions of mastication and deglutition—affecting, furthermore, in the later stages of the disease, the voice and the function of respiration. The paralysis is caused by a progressive degeneration and atrophy of the ganglion-cells of those nerve-centres in the medulla oblongata from which the muscles of the above-named organs receive their supply of nervous energy, though in most cases the pathological process extends to, or even beyond, the roots of those nerves which originate in these centres and terminate in the respective muscles. In many cases the pathological process extends to the spinal marrow, and there causes paralysis and atrophy of the muscles of the trunk, and, generally, of the upper extremities. Almost in every case the disease, as its name indicates, slowly progresses until it terminates in death.

There are, however, a number of cases observed which, though exhibiting the same or similar symptoms, do not, in reality, depend upon a progressive degeneration and atrophy of the centres and nerve-roots of the medulla, but, on the contrary, owe their symptoms to other causes; as, for instance, to tumors, hemorrhages, syphilitic neoplasms, etc., which, either by pressing upon the medulla from without, or, if situated within, by deranging in various manners the

individual nervous elements of that part, may give rise to some or even all of the symptoms of true labio-glosso-laryngeal paralysis. These symptoms, however, according to the character of the lesion, may, after remaining stationary for some time, retrograde, and even disappear, as has been observed in syphilitic cases; or they may progress, and finally end in death. In order to distinguish these cases from the chronic or progressive bulbar paralysis some authors have attached the term retrogressive to this form of the disease.

SYMPTOMS.—As the degeneration of the nerve-centres in the medulla oblongata, upon which the disease depends, does not proceed in a regular fixed order, the order in which the clinical symptoms successively appear also varies in different cases. In the majority of cases, however, the symptoms appear gradually, manifesting themselves generally in the form of a greater or lesser impediment in the articulation of certain sounds or letters depending upon the movements of the tongue, such as e, i, k, l, s, and c, while at the same time a difficulty of mastication and deglutition may be experienced by the patient, due to the progressive development of the paralysis, which deprives the tongue of its lateral and forward movements. To this cause also, at this period, the apparently increased secretion of saliva, running from the corners of the mouth, must be attributed. With intelligent patients these symptoms are rendered less prominent by the special effort which they make to pronounce slowly for the purpose of hiding the deficiency in their speech. But as the disease advances the difficulty of articulation increases on account of the paralysis extending to the orbicularis oris, thus affecting the mobility of the lips and interfering with the pronunciation of the labial sounds p, b, f, m, and w With the loss of power of articulation the patient's speech becomes gradually reduced to monosyllables, or even, finally, to incomprehensible and inarticulated grunts, by which he expresses his wants to his friends. In consequence of the paralysis of the lips the patient becomes unable to whistle or blow or to perform any movement depending upon these organs, while at the same time, through the disturbance created in the co-ordination of the facial muscles by the paralysis of the orbicularis oris, the mouth becomes transversely elongated and

drawn downward by the action of the remaining unparalyzed muscles upon its angles. With the mouth partially open and the lower lip hanging down, the face of the patient has a peculiar sad and painful expression, while the voice assumes a nasal sound on account of the paralysis of the palate.

After a while the difficulty of deglutition, caused by the inability of the tongue to properly assist in the formation of the bolus of food and its propulsion into the pharynx, increases on account of the paralysis extending to the muscles of the pharynx. The failure of these muscles in the performance of their special function of grasping the food and carrying it to the œsophagus obliges the patient to push it down the pharynx with his fingers. In some cases the difficulty of swallowing rests with solids, in others with fluids. The defective deglutition furthermore gives rise to spells of coughing and suffocation by portions of food getting between the epiglottis and larynx, while the paralyzed muscles of the palate allow the fluids to pass through the nose and enter the posterior nares.

As the case slowly proceeds the symptoms grow worse. The paralysis of the orbicularis oris reaches a point when this muscle is no more able to close the oral cavity; the mouth of the patient therefore remains open. The tongue, having now entirely lost its lateral, forward, or upward movements, rests motionless upon the floor of the mouth, evincing no other signs of life but occasional slight muscular twitchings. In some cases a diminution of the sense of taste, and also of that of touch in the tongue, pharynx, and larynx, has been observed. Atrophy of the tongue and lips now sets in, and the function of speech is almost entirely lost. The only letter which the patient is still able to pronounce is a (broad); all other sounds are indistinct and can hardly be understood. The paralysis of the tongue and other muscles of deglutition gives rise, furthermore, to an accumulation of the now excessively secreted saliva, which, being retained in the oral cavity, assumes the form of a viscid mucous liquid dripping from the mouth, extending, in the form of strings or ribbons, between the surfaces of the lips. Finally, when, through the progressive paralysis of the orbicularis oris, the patient can no more

close the lips, the flow of saliva from the mouth becomes continuous; he is then seen engaged in the constant use of his handkerchief for removing the secretion.