good enough

TheToleranceforMediocrityinNatureandSociety

DANIEL S. MILO

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England 2019

Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved

Cover image: Giraffe/Private Collection/Bridgeman Images Cover design: Jill Breitbarth

978-0-674-50462-2 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-24005-6 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24006-3 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24004-9 (PDF)

TheLibraryofCongresshascatalogedtheprintededitionasfollows:

Names: Milo, Daniel S. (Daniel Shabetaï), author.

Title: Good enough : the tolerance for mediocrity in nature and society / Daniel S. Milo.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018052620

Subjects: LCSH: Evolution (Biology) | Natural selection. | Social evolution. | Imperfection.

Classification: LCC QH366.2 .M555 2019 | DDC 576.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018052620

In memory of my beloved, Naomi Aviv Milo, who knew

Contents

Introduction

PART ONE Icons as Test Cases

1. The Giraffe: Science Begins in Wonder

2. The Domestication Analogy: Darwin’s Original Sin

3. The Galápagos and the Finch: Two Unrepresentative Icons

4. The Brain: Our Ancestors’ Worst Enemy

PART TWO The Theory of the Good Enough

5. Embracing Neutrality

6. Strange Ranges: The Bias toward Excess

7. Nature’s Safety Net

PART THREE Our Triumph and Its Side Effects

8. The Invention of Tomorrow

9. Humanity’s Safety Net

10. The Excellence Conspiracy: Critique of Evolutionary Ethics

Notes Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Index

The world of things living … has room, wide but not unbounded, for variety of living form and structure, as these tend towards their seemingly endless but yet strictly limited possibilities of permutation and degree: it has room for the great and for the small, room for the weak and for the strong … The ways of life may be changed, and many a refuge found, before the sentence of unfitness is pronounced and the penalty of extermination paid.

D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On GrowthandForm (1942)

Introduction

Sigmund Freud wrote of three successive scientific “outrages upon [humanity’s] naive self-love.” The first was inaugurated by Copernicus, who discovered “that our earth was not the center of the universe, but only a tiny speck in a world-system of a magnitude hardly conceivable.” The last was Freud’s own: the revelation “to the ego of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house.” Between them was an idea that arrived “upon the instigation of Charles Darwin, [Alfred Russel] Wallace, and their predecessors.” This was the evolution of species by means of natural selection, which “robbed man of his peculiar privilege of having been specially created, and relegated him to a descent from the animal world, implying an ineradicable animal nature in him.”1

The repercussions of two of those “outrages” were far-reaching. While the Copernican revolution resists popular appropriation— perhaps because we are not capable of experiencing the earth as other than flat and the sun as other than rising and setting— evolution and psychoanalysis mold our worldview. This despite the fact that few of us have opened The Interpretation of Dreams, and even professional biologists rarely read On the Origin of Species. Freud’s key concepts—subconscious; Oedipal complex; libido; reality and pleasure principles; defense mechanisms; sublimation; narcissism; id, ego, and superego—are embedded in daily life no less than in therapeutic practice.2 Darwinism is similarly inescapable. Natural selection, struggle for survival, Malthusian competition, humanity’s apish origin, and adaptation are all pervasive in thinking about nature and human communities.

In particular, Darwinism courses through the ethics of capitalism. The latter’s terms—maximization, optimization, competitiveness, innovation, efficiency, cost-benefit trade-offs, rationalization—draw on the authority of Darwinian views of nature. Social Darwinism may be passé, but natural capitalism is fully alive. In the pages that follow, I will argue that Darwinism and neo-Darwinism—the mating of natural selection and genetics established in the mid-twentieth century—have a lot in common with neoliberalism. Nature knows what she is doing; in the market we trust. Homo economicus and animal economicus pursue the same goals and obey the same rules.

If evolutionary thought all too easily naturalizes capitalism’s competitive zeal, it is because Darwin was only partly right. There is no doubt that all organisms evolved from a common ancestor. But Darwin strayed in attributing evolution overwhelmingly to natural selection. It is this view that inspired Herbert Spencer, the father of social Darwinism, to coin “survival of the fittest.” At Wallace’s suggestion, Darwin himself eventually adopted this concept, too.3 It remains the basis of popular understanding of evolution today: everyone knows that nature is harsh and only the strong survive. But they are only partly right: nature is harsh sometimes; the strong survive often, but the weak stand a chance, too.

Both experts and the public join Darwin in overemphasizing natural selection, thereby distorting our sense of its role in both nature and humanity. Natural selection does occur, but there are nonadaptive mechanisms of change as well, such as genetic drift, geographic isolation, and the founder effect. None of these paths to survival rewards the hardest struggler or the best specimen. Their rewards are governed not by merit but by chance.

Genetic drift, the most prominent of these mechanisms, is the random change in the relative frequency of a gene variant, or allele, within a population. Genetic drift results in the survival not of the fittest but of the luckiest. One example is the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris). This seal experienced what evolutionary biologists call a bottleneck: an abrupt and drastic reduction in

population size due to an environmental shock. By the late nineteenth century, the northern elephant seal had been harvested nearly to extinction for the oil derived from its blubber. Just a hundred or so specimens from Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, survived under the protection of the Mexican government. Those seals’ alleles persist in today’s population not because they were selected but because they got lucky.

Geographic isolation occurs when a population is cut off from the other members of its species. It can lead to speciation by means of inbreeding within a narrowed gene pool. The isolated population has only so many variants in it, and only these can be passed down and recombined in the next generation. The result is divergence from the original population, as each is now reproducing a different set of alleles. The origin of the new species is not natural selection but chance.

Likewise, the founder effect occurs when a few members of a population strike out from their habitat and start a new community. But though these founders may initiate an enduring lineage, they are not necessarily the fittest of their kind, nor do they necessarily adapt to their new environments through the fixation of advantageous mutations. A famous example is the small group of pigeons that landed on the island of Mauritius ages ago, lost their ability to fly, gained twenty kilograms, and evolved into Raphus cucullatus, also known as the dodo.4 The origin of this species was due to chance.

Specialists understand all this, so they avoid using “survival of the fittest.” And they know that natural selection does not cull every useless, exaggerated, and inefficient mutation, preserving only the best. Yet in 2007, Richard Dawkins defended the image of nature as “a miserly accountant, grudging the pennies, watching the clock, punishing the smallest extravagance. Unrelentingly and unceasingly.”5 Indeed, evolutionary scientists as a group have done little to disabuse the public of Darwinian conceptions. Though the list of phenomena known to pass under natural selection’s radar is long and getting longer, scientists behave as though natural selection

were natural law. They may not do so as openly as Dawkins, but their bias shows in their nearly exclusive focus on the discovery and confirmation of adaptations. Journalists, reflecting and reinforcing the public’s selection bias, trawl issues of Scienceand Naturefor the latest evidence of possible adaptations, not the more complicated story of how evolution really works.

In that story, the humble and the humbled survive and multiply. The inefficient and the wasteful are certainly not the fittest, but they are good enough to make do. Natural selection has fashioned beautiful works, but it also tolerates a great deal of mediocrity. Even Darwin and Wallace thought so, before the Origin’s publication in 1859. Three years earlier, Darwin described nature as “clumsy, wasteful, horridly blundering,” the opposite of the grudging efficiency monger.6 That same year, Wallace affirmed nature’s tolerance for inutility: “Do you mean to assert, then, some of my readers will indignantly ask, that this animal, or any animal, is provided with organs which are of no use to it? Yes, we reply, we do mean to assert that many animals are provided with organs and appendages which serve no material or physical purpose.”7 This book aims to restore attention to what Darwin and Wallace perceived before their co-discovery committed them to hardened selectionism.

In addition, I hope to correct what are commonly understood as the prescriptive ramifications of evolutionary theory. Despite official disgust with Spencer and eugenics, survival of the fittest continues to underwrite political principles. We see the notion of Darwinian competition at the foundation of a merciless meritocracy. The winner owes survival / success to excellence, and the loser owes extinction / failure to its absence. The former has only him- or herself to congratulate; the latter, only him- or herself to blame.

As I detail in Chapter 2, Darwin himself first made this leap from nature to society. “All organic beings are striving to seize on each place in theeconomy ofnature,” he wrote in the Origin.“If any one species does not become modified and improved in a corresponding degree with its competitors it will be exterminated.”8 In the years

since, biology has stamped its seal of approval on market fundamentalism. Survival of the fittest is gospel in the thinking of Milton Friedman, per Robert Frank’s The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good.9 The business press tells us that “economic cycles are Darwinian, picking off weak companies and leaving survivors stronger.”10 Investment firms preach the doctrine of “corporate Darwinism.”11

Whether we should, in the first place, look to nature for social models is an important and complex question but one I don’t address. Instead, I only wish to propose that nature cannot be called upon to endorse capitalist ethics because it prefers inertia and copypaste to change and originality. The replication machinery of the DNA aims at a 100 percent success rate, with each new generation a perfect likeness of the previous. Organisms migrate only under stress; they would much rather stay home. There is, in general, no better tactic than to imitate one’s progenitors, since they have already proved their talents in the arts of survival and reproduction. Just ask the coelacanth (Latimeriachalumnae).This lungfish, known as the “living fossil,” has barely changed during the last four hundred million years.

In nature, change is either an accident, as in mutations, or a last resort, as in migration. It is never an end in itself. In the human society modeled on supposed Darwinian truths, change may still be motivated by accident or necessity, but change for change’s sake is all around us. Stagnation is the antithesis of all that capitalism and its culture demand, the heresy banished from the temple of the God Growth. Rather than rest, we are programmed to need new products, new artworks, new research. Under the regime of planned obsolescence, innovation follows its own urges, not the failure of old models. Industry, academia, politics, fashion—all modern economic and cultural efforts create products with artificially limited life cycles.

As a result, most of what we produce and consume is excess. Our so-called needs usually have nothing to do with our survival. Humans can do with less, a lot less, of almost everything, from

surgical specialties and breeds of dog to varieties of breakfast cereal and synonyms for “wonderful.” And while we may at times struggle for existence, some of us more than others, most days are mostly peaceful, with little need of competition to prove our worth. We know this because, with all due respect to Friedman, there issuch a thing as a free lunch. As I discuss in Chapter 9, human communities do a great deal to care for their members at no charge. This book is an example of what can be obtained gratis; it would have been impossible without the help of numerous biologists who charged neither money nor credit for their counsel.

Human society is not ruthlessly competitive, and neither is nature. Both are tolerant of excess, inertia, error, mediocrity, and failed experiment. Where great successes occur in society and in nature, luck can be far more important than talent. Yet there are many who tell us that talent—sometimes rendered as fitness, sometimes as merit—is all that matters in nature and in human affairs, each following a deep Darwinian law of the universe. This is the dogma I seek to undermine.

Key Scientific Concepts

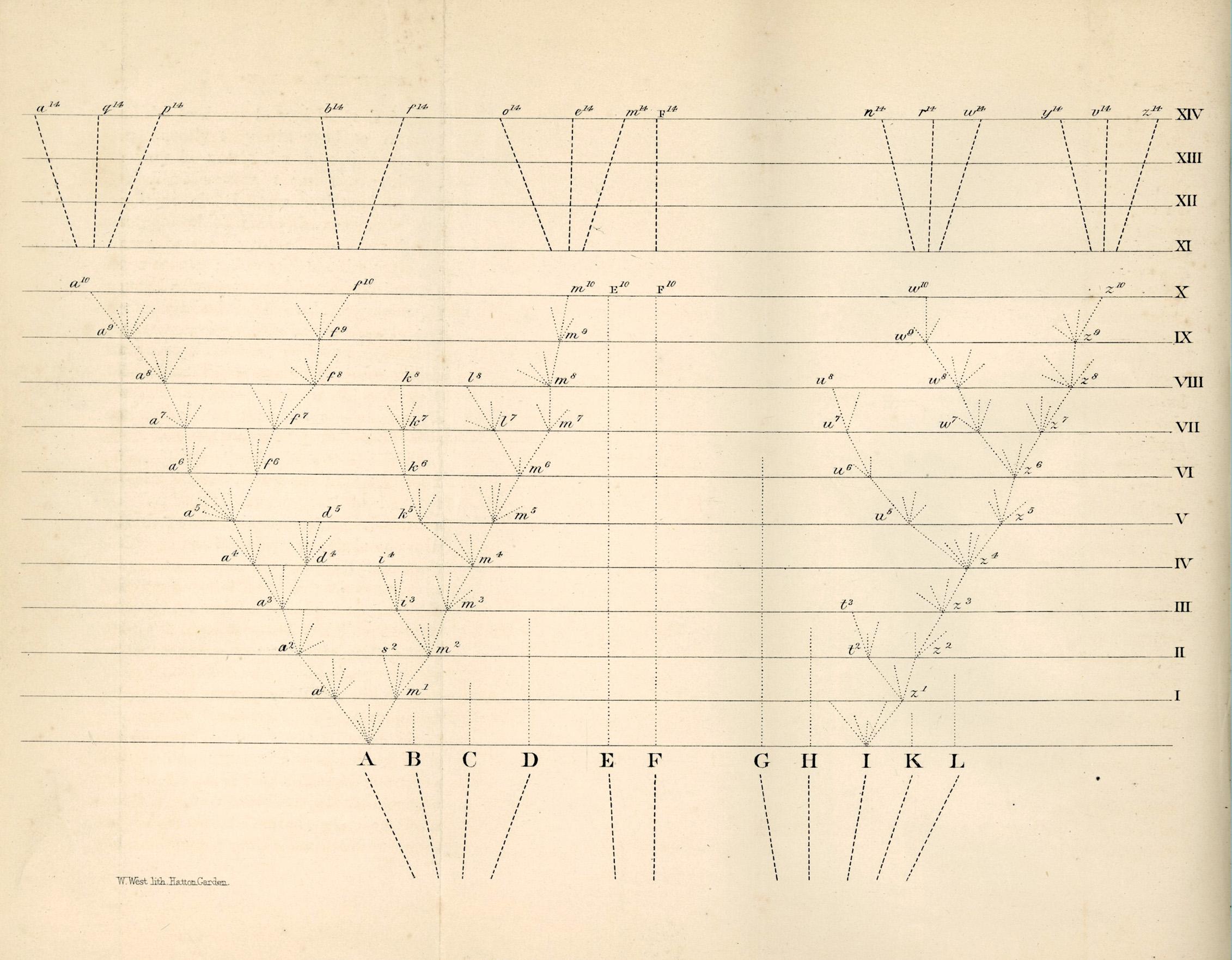

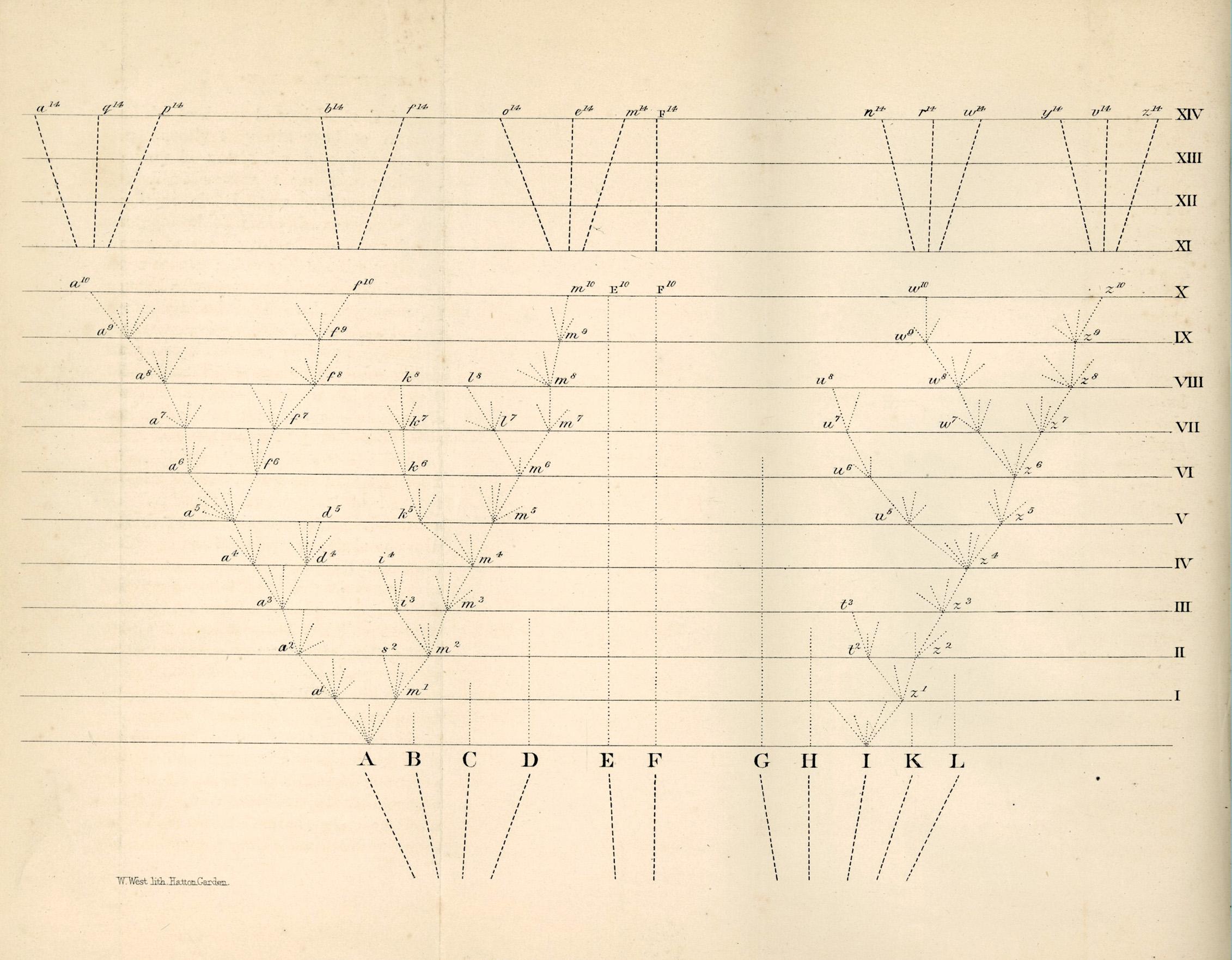

Before questioning Darwinism in greater detail, I have to specify what I mean by that term, because in fact two theories are found under its umbrella: descent with modification, sometimes referred to simply as “evolution,” and natural selection. According to the former, Darwin wrote in the Origin, “Probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed.”12 Darwin illustrated this prophetic speculation with a tree of life showing new species branching from predecessors, some continuing and others dying off (Figure I.1). Molecular biology proves Darwin right. The theory of natural selection holds that descent with modification is directed by a process “daily andhourlyscrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is

bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of eachorganic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.”13 This book argues that Darwin was sometimes right and often wrong.

Darwin viewed descent with modification and natural selection as inextricably linked, hence the full title of his On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favoured Races in theStruggle for Life. This pairing of two distinct theories became orthodoxy, though it faced skepticism in Darwin’s own time. The common ancestry of all extant organisms was received as such by many of Darwin’s contemporaries; it was natural selection that initially received pushback from fellow evolutionists. St. George Jackson Mivart, a nineteenth-century disciple, bought into descent with modification but rejected natural selection entirely.14 Darwin took Mivart seriously enough to dedicate a chapter of the Origin’s sixth and last edition, “Miscellaneous Objections to the Theory of Natural Selection,” to his rebuttal. Another acolyte, George Romanes, did not reject natural selection but questioned its sole authorship of evolution. “I have found it impossible to entertain a doubt, either upon Evolution as a fact, or upon Natural Selection as a method,” Romanes wrote. That is, natural selection is not a fact but one way to look at facts. Romanes pointed to other possible sources of evolution, such as speciation through geographical isolation, now called allopatric speciation.15 Throughout this book, I return to Romanes to emphasize his underappreciated yet visionary contributions.

Figure I.1. Darwin’s Tree of Life: The Origin of Species illustrates descent with modification, showing numerous lineages emerging, persisting, and dying out across fifteen generations. Every species is a product of descent with modification, but Darwin erred in asserting that natural selection is overwhelmingly the agent underlying this process.

Another contemporaneous objection came from Wallace. The codiscoverer of natural selection was its most ardent defender, yet even he granted special dispensation to Homo sapiens in a paper titled “ The Limits of Natural Selection as Applied to Man.”16 Wallace attributed human evolution to a “WILL of higher intelligences or of one Supreme Intelligence.” That Wallace erred in the direction of intelligent design avant la lettre speaks to the blurred boundary between that false idea and Darwin’s overzealous selectionism, as I discuss later in this introduction and in Chapter 10.

Much as there are two theories under the heading of evolution, we might also say that there are two evolutions. The first, celebrated

by the title OntheOriginofSpeciesby Means ofNaturalSelection, accounts for speciation or interspecific variability. This is evolution as Darwin and his successors understood it. The second evolution is concerned with the existence of a species between its origin and its extinction; its normalcy, if you wish. The average lifespan of a species is between one million and ten million years. From the standpoint of Darwinian evolution, this time is uninteresting because it is static. But, in fact, during this time, there is much change; species accumulate variability, both qualitative and quantitative, though it may have no adaptive impact. The theory of the “good enough” aims to account for this intraspecific diversification.

What I am suggesting is that during stasis, organisms have the freedom to vary unimpeded and unimproved by natural selection. During certain explosive moments in natural history, environmental events and forced migration have obliged organisms to adapt to new niches—new competitors and changed habitats—or die. This is the first evolution. Those that do adapt pass along traits that make their descendants more robust and therefore more impervious to factors producing extinction. These descendants spend most of their lives at relative peace, so they can accumulate neutral variants—that is, variants that confer no benefit. There are enough resources to go around, and the fundamentals of life are sufficiently strong that any variant—excellent or mediocre—can survive as long as it isn’t lethal.

Biologists do appreciate the concept of neutral mutation, which was introduced in the 1960s by the population geneticist Motoo Kimura. But this theory is limited to the genotype; it does not concern phenotypic expression or behavior. Phenotypic neutrality, which I propose, is a Darwinian oxymoron. A phenotype that is not beneficial to its bearer is detrimental by definition, since it costs energy but earns nothing in exchange. Therefore, when faced with apparently useless or deleterious traits, biologists assume either that the traits are beneficial but for reasons not yet discovered or that natural selection will eventually catch up with them.

Accepting tolerance for neutrality at the phenotypic level would be a paradigm shift. Darwin seemed to leave open the possibility, but with considerable reservation. In TheDescentofMan,he wrote, “I did not formerly consider sufficiently the existence of structures, which, so far as we can at present judge, are neither beneficial nor injurious; and this I believe to be one of the greatest oversights as yet detected in my work.”17 Much faith is invested in that “at present”—we may not yet know the benefits of a given trait, but someday we will. Regardless, Darwin’s followers never gave these musings much credence. Romanes, however, was an exception. “A very large proportion, if not the majority, of features which serve to distinguish species from species are features presenting no utilitarian significance,” he wrote.18 Yet his position all but disappeared from biology after the 1890s, overwhelmed by a view more in line with Wallace’s hardened selectionism: “None of the definite facts of organic nature, no special organ, no characteristic form or marking, no peculiarities of instinct or of habit, no relations between species or between groups of species, can exist but which must now be or once have been useful to the individuals or races which possess them.”19

Against the heavy weight of tradition, I follow Romanes and extend the principle of neutrality to all strata of life, from the molecular to the behavioral. Granted, proving uselessness is as impossible as proving that you don’t have a sister. Instead, I approach uselessness via a close cousin: excess. What is excess? When you can do the same, or better, with less. What is uselessness? When you can do without.

The orthodox position holds that quantitative excess will be culled because it imposes metabolic burden: having more of something than needed forces an organism to do the hard work of obtaining additional calories, which is an adaptive disadvantage under conditions of Malthusian competition. So, to the extent that excessive traits are present in nature, we should doubt the role of natural selection in fixing and propagating them. As it turns out,

having too much is almost as common in nature as it is in human society. For reasons I detail in Chapters 6 and 7, nature is strongly biased toward excess.

The distinction between qualitative and quantitative excess is critical. Even if we grant that all traits are or were once selected, the same is not necessarily true for their size and amount. For instance, giraffes cannot do without legs, but they would be better off with shorter ones in at least one respect: they give birth standing up, to newborns weighing seventy kilograms, who then fall head first.20 Or consider the avocado. The average avocado tree has a million flowers but yields just one hundred fruits.21 Somehow avocado trees have managed to survive despite their profligacy. And one would be hard-pressed to come up with a selective explanation for the genomic excess of Parisjaponica.This little flower has fifty times as many DNA base pairs as Homosapiens.

If the prevalence of quantitative excess in nature is not enough to convince us of natural selection’s limits, then wide phenotypic ranges should be. It is an obvious but little acknowledged fact that most traits are viable across a range of amounts and sizes. For instance, a study of human kidneys in five racial groups from three continents found that people may have as few as 210,332 nephrons per kidney and as many as 2,702,079, with the healthy minimum located near the bottom of the range.22 There is no way natural selection “chose” nearly 3 million nephrons when about 500,000 would suffice. Wide ranges and optimization are incommensurable. Such ranges, the subject of Chapter 6, are smoking-gun evidence for natural selection’s chronic fallibility.

Wide ranges speak to what I call ontological neutrality. It simply does not matter whether one has 500,000 nephrons per kidney or 2 million. But as I discuss in Chapter 5, neutrality is not just a reality; it is also a way of looking at reality. I call this methodological neutrality. In criminal law, for instance, methodological neutrality is inherent in the presumption of innocence: everyone is innocent by default, and the burden of proof weighs on the accuser. In science,

methodological neutrality is expressed by the null hypothesis, namely that every relationship between phenomena is, by default, the fruit of chance. The burden of refutation weighs on the researcher. You don’t have to prove innocence or justify chance.

Evolutionary biologists invert the principle: being selected is the default state, and a chance result is the outlier. There is a presumption of selection in nature, so a biologist is exempt from proving it. Instead, the burden of proof lies on whoever claims that a trait or a size was not selected. The time is ripe for biologists to embrace the ways of their fellow scientists and accept the null hypothesis: chance, which is to say, neutrality. Doing so does not imply rejection of natural selection, an indefensible stance. What it does imply is the rejection of natural selection as the default state in nature.

But while we cannot reject natural selection, we should recognize that, in the Darwinian mode, it is conceptually problematic. The trouble is that natural selection arises from a false analogy to artificial selection. As I discuss in Chapter 2, Darwin theorized natural selection in the image of a breeder who chooses one or another desirable trait from his specimens and promotes them in subsequent generations. We have this analogy to thank for the mistaken view that nature selects and that it selects only the best. This flaw in Darwinism was also known in the time of its creator. Wallace, though he became a devout selectionist, contested the domestication analogy as a major weakness in Darwin’s reasoning.

The domestication fallacy is to blame for the common misconception that nature is a subject that takes action. Nature doesn’t select, operate, cause, scrutinize, or purify. It doesn’t do anything. Rather, nature is a shifting set of conditions under which different traits make greater and lesser contributions to an organism’s probability of survival and reproduction. Very poorly adapted organisms will almost certainly be culled; their survival probability is virtually zero. Better-adapted organisms have a greater

probability of surviving and reproducing. Their traits need not make them excellent, as wide ranges and excess demonstrate. Whether or not a species or an organism is well adapted, nothing has selected its traits. All we know is that these species and organisms are good enough not to die off. For this reason, I suggest substituting for natural selection the language of natural elimination or, better still, natural probability. However, to maintain continuity with the field of evolutionary biology, I typically use the consensual term natural selection to denote the process scientists have in mind when they speak of it.

Although biologists everywhere bemoan the language of nature as subject, practically all of them, and the public in their wake, remain loyal to the view that a breeder-like, optimizing natural selection is the default state of nature. How does natural selection maintain its dominant place in evolutionary thought despite its low relative frequency? I argue that the culprit is the biased human brain. It has a pronounced preference for the exceptional, which natural selection surely is, in the senses of being both rare and awe inspiring. One cannot but be impressed by the workings of, for example, adaptive selection. The Galápagos finches are the famed case, discussed in Chapter 3. All evolved from one species that drifted away from South America three million years ago. The finches descended from a generalist species, but having landed on islands with sparse resources, they had to develop specialties to survive. Thus, the cactus finch (Geospiza scandens) possesses a long beak with a pointed bill used to dig nectar and pollen from cactus flowers. The vampire finch (Geospizaseptentrionalis)uses its sharp bill to cut wounds on sea birds and drink their blood. The large ground finch (Geospiza magnirostris) has an extremely deep and broad bill, which works like a pair of pliers to crack hard seeds. Another illustration of natural selection’s potency is Batesian mimicry. The spotted predatory katydid (Chlorobalius leucoviridis) is a bush cricket that imitates sexually receptive female cicadas to attract male cicadas on which to prey. This aggressive and intricate imitation is

accomplished acoustically with clicks and visually with synchronized body jerks.23 And for a final illustration, let’s look at the signaling principle. The springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), a species of southwest African antelope, has a unique behavior: pronking. Upon encountering predators, it performs a series of stiff-legged leaps, with its back bowed and the white flap on its rump lifted. In this way, the springbok signals that it is young, fit, and not worth chasing.

And yet spectacular as natural selection is in these cases, most birds are primarily generalists, most crickets are simpleminded, most antelopes are guileless, and springboks also pronk in the absence of predators. Species and organisms often survive not because they are special but because they don’t have to be. On this view, however, they possess no magnetism, no elegance. They tell no story and project no significance into the world. To say that most of what survives was not selected but is just not bad enough to be eliminated is to demote natural selection from its exalted place in the order of life. Natural selection is biology’s greatest intellectual contribution; of course it is prized. Natural law leaves us quaking in wonder, while chance interests only gamblers.

Because the Darwinian bias toward natural selection is now baked into popular understanding of evolution, it is not enough to tell the truth, nothing but the truth, but also to tell the wholetruth. Rather than presume and seek out a selectionist explanation for what are most likely neutral traits, biologists might presume the ubiquity of the latter even as they marvel at the exceptions. And they might talk about it in public. Doing so would make an immense difference. Differential algebra, organic chemistry, and optical physics have no impact on our worldview; the theory of evolution does. When specialists in these other fields realize that they have been operating on the basis of unsound presuppositions, the corrections tend to stay “in house.” Their fields are torn down and rebuilt, but the rest of us are unperturbed. By contrast, Darwinian and neo-Darwinian ideas such as survival of the fittest, optimization,

adaptation, and Malthusian competition reverberate in the way we experience reality, society, and ourselves. It follows that when these ideas misrepresent nature, they weigh heavily on our selfrepresentation.

Mooting Intelligent Design

Although biologists now largely understand that it is an error to ascribe to natural selection an evolutionary monopoly, they have not discarded their bias. One explanation for their stubbornness, I have suggested, is the allure of significance. But another may be fear of strengthening the wrong side in politically contentious debates with latter-day creationists promoting intelligent design. Indeed, the generous biologists who guided me, a philosopher, throughout my studies of evolution were always encouraging, but they also warned me that everything I say will be used against science. For instance, if I argue that most animals in the Galápagos Archipelago Islands don’t abide by the principles Darwin developed on his visit, as I do in Chapter 3, intelligent-design advocates will infer that evolution itself is a myth.

I therefore wish to be adamant about this important point: none of the arguments in this book can be reasonably construed as invidious to the theory of descent with modification, a firmly demonstrated law of nature. Nor do any of my arguments deny the reality of natural selection, only its prevalence. Nothing here necessitates a force beyond nature managing the creation and form of species.

Partisans of intelligent design argue in bad faith, so they might still claim my views on behalf of their mistaken ideas. In fact, my arguments vitiate theirs; there is a strong correlation between the ubiquity of neutrality and the falseness of intelligent design. That is because intelligent design is parasitic on selectionism. Intelligent design begins from the premise, supplied by selectionism, that species are optimized. Intelligent design takes Darwin’s analogy to

domestication as more than figurative, asking how the perfection of nature—or, in Wallace’s case, the human specifically—could possibly be achieved without the intervention and direction of an intelligent force, a great cosmic breeder or sculptor. In contrast to both selectionism and intelligent design, the theory of the good enough turns our attention to nature’s many imperfections. Because nature is not optimized, intelligent-design advocates are actually assigning waste and mediocrity to the handiwork of an omnipotent being of supernatural intelligence. Why venerate such a lazy and inept God? When we temper our selectionist expectations, the absurdity of intelligent design emerges in even sharper relief.

A Note on Method: A Place for Natural Philosophy

“Scientists apply themselves to what they believe to be the most important of the problems that seem tractable,” the Nobel Prize–winning biologist François Jacob wrote; “those that rightly or wrongly they think they will be able to solve.”24 Peter Medawar, another biology Nobelist, calls science “the art of the soluble.”25

From the pre-Socratics to Bacon to Darwin, natural philosophers have not been so constrained. Philosophy begins in wonder, Socrates and Aristotle said, and whatever fills us with wonder deserves to be explored. Or, to use Martin Heidegger’s terminology, philosophers need not be limited to questions that are answerable (fraglich)via a consensual protocol of proof and refutation. They can work on questions worth asking (fragwürdig) even in the absence of such a protocol.

It is regrettable that only answers to fraglich questions get published in scientific journals, because the fragwürdigquestions are the sort that set and reset paradigms. Democritus had no way to prove the atomic theory, and Darwin had no way to prove the common ancestry of all organisms. Democritus inferred his theory from the differential solidity of substances: since iron is more solid than water, the two must comprise different components. Darwin

relied on analogy, a fortiori arguments, deduction, common sense, and personal experience. Particularly important to him was a maxim learned from his mentor, the geologist Charles Lyell: The present holds the key to the past; the same processes now governing nature have always done so. Democritus’s inference could never grace an issue of Science.Nature, founded in 1869 by Darwin’s inner circle to promote the master’s ideas, would not publish his papers because they were based on random observations, secondhand information, and primitive experiments.26

Though Darwin’s work is proto-scientific according to contemporary standards, scientifically minded people consider his contribution the “single best idea anybody ever had.”27 What if science allotted natural philosophy a niche? This is the path I follow. I sit on Darwin’s shoulders but wear a different blindfold. His admits the light of selected traits while blocking the rest. Mine is tailored for natural selection’s leftovers. I also have the advantage of access to findings he could not have been aware of, especially in genetics and paleontology. Our obsessions differ, too. Darwin’s holy grail was “that mystery of mysteries, the replacement of extinct species by others,” as the English polymath John Herschel put it in a letter to Lyell quoted in the first lines of the Origin.28 My unholy grail is the origin of excess, neutrality, and mediocrity, features neglected by evolutionary biology and despised by evolutionary ethics. I have decided to invert Darwinism’s bias, to look at the pursuit of excellence as a problem and not as a self-evident drive. In doing so, I hope to render the familiar strange, which is the first step in any intellectual endeavor.

Although I use Darwin’s tool kit, scientists will likely find my methods incautious. They are not wrong. Science and philosophy have different styles. Scientists suggest and then qualify their suggestions. Philosophers assert and then radicalize their assertions. In this book, I engage in much speculation, in particular about how we can account for the resurrection and flourishing of Homosapiens, a species that was on the brink of extinction only 60,000–70,000

years ago—a tick of the second hand on the geological clock. I do not deny the speculative character of some of my arguments, although it is worth pointing out that selectionist explanations are themselves frequently speculative. I don’t expect that all my speculations will eventually be verified by experiment; some cannot be. I only hope to convince readers that the theory of the good enough deserves to be tolerated in biology.

From Culture to Nature

Although not a biologist, I do possess long-standing expertise in the subjects at hand. While I cannot splice genes in a lab, my career has been devoted to the philosophical investigation of excess, excellence, merit, and innovation, often through Darwinian eyes. In 1979, as a graduate student at the University of Tel Aviv, I gave a lecture titled “A Theory of Stagnation,” in which I questioned change and novelty as necessary conditions for the production of celebrated cultural products. This led to my 1986 doctoral dissertation, “Aspects of Cultural Survival,” in which I theorized cultural selection by analogy to Darwinism. The pantheon of cultural greatness is Malthusian. The number of seats in the pantheon grows arithmetically, while the number of aspirants grows exponentially. The struggle for survival in the collective memory is arbitrated by posterity, the cultural equivalent of natural selection.29 Posterity tends to make its choices with the help of two heuristics. One is incumbency bias: the earlier one enters the pantheon, the harder he or she is to expel, no matter the quality of the work celebrated. The other is laziness bias: posterity tends to select those who were already recognized by their own contemporaries; a lifetime of success is an important, if not strictly necessary, condition for posthumous lionization.30 Rare exceptions such as Gregory Mendel will console only inveterate optimists.

In this book, after more than a decade of evolutionary study, I return to the iconic source of my study of cultural icons: Darwinism.

Again, I question the roles of novelty and merit in the selection process. But though I come to this subject from my same philosophical perspective, I might add that there are serious and even trailblazing biologists on my side. True, none of them has offered a comprehensive complementary theory to explain what Darwin and his followers leave out. Even so, I take heart from the words of Sydney Brenner, who won the Nobel Prize for his efforts in discovering messenger RNA (mRNA). “Whereas,” Brenner explains, “mathematics is the art of the perfect and physics the art of the optimal, biology, because of evolution, is only the art of the satisfactory.”31 Species need not be perfect or optimal, only satisfactory. François Jacob opposes in his autobiography Jacques Monod’s Cartesian idea of nature to his: “I saw nature as a rather good girl. Generous, but a little dirty. A little messy. Working in a piecemeal way. Doing what she could with what she found.”32 Let us give clear thought to what that implies for our ideas about nature and about society.

I am also not the first to wonder about what the partiality of Darwinism means for politics. Lynn Margulis, the pioneer of the theory of symbiosis in evolution,33 defined herself as an adherent of descent with modification and an adversary of natural selection as its principal agent. She rejected the “capitalistic, competitive, costbenefit” interpretation of Darwin.34

Margulis expressed nothing outlandish when she told an interviewer that “natural selection eliminates and maybe maintains, but it doesn’t create.”35 I detail throughout this book a more controversial claim: that natural selection’s maintenance is, most of the time, in abeyance. Natural selection is not a natural law; it is a relative frequency. Facing little pressure to adapt, the mediocre survive and thrive. It is a jungle out there, but, unlike deserts, jungles are not very competitive places. They are full of resources and opportunities and thus are hotbeds of life. It is true that every species in the jungle—and everywhere else—has traits that are products of selection, but each also possesses traits that are merely

tolerated. In the end, the most we can say for any living organism is that it is good enough not to die.

Structure of the Book

This book is divided among three broad themes. In the first part, I discuss problems with established theories. I cannot possibly critique every case of selection bias, so instead I focus on a few Darwinian icons and judge how the theory of natural selection fares when asked to account for its own exemplars. Approaching a paradigm via its icons presents many advantages. Icons achieve their status precisely because they are taken to be representative, so they serve as shortcuts to the heart of the matter. Icons are also discussed in abundant literatures, leaving us much to interrogate. Throughout my career, I have turned to icons in order to investigate suspicious consensuses. Through studies of iconic personae, works, monuments, and myths—the Eiffel Tower, the terrors of the year 1000, Hamlet, Adam and Eve, Dr . Jekyll and Mr . Hyde, Pandora’s box, Van Gogh, Narcissus—I have sought to show that theories often fail to live up to their theses.36 Either icons are not accurately explained by the theory they are taken to exemplify, or they are singular rather than representative members of their classes. In essence, I ask here: If natural selection cannot make sense of its icons, how much else must escape its explanatory power?

I begin in Chapter 1 by surveying the history of the fascination with the giraffe, particularly its neck. The giraffe has long been a shining star in the Darwinian firmament. Understanding why evolutionists chose this example helps make sense of how they went astray. Humanity’s wonder at this unusual, seemingly unnatural creature long predates Darwin, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and their contemporaries, suggesting that the giraffe was chosen as an evolutionary icon not because it is a particularly good example of natural selection at work but because it crystallized the struggle to understand nature using a scientific framework. For centuries,

giraffes were thought of in many cultures as avatars of the supernatural; thus, they made fetching quarry for evolutionists. Shooting down the supernatural required prosaic explanation for the seemingly impossible. If such an extravagant organ as the giraffe’s neck is selected, then, a fortiori, so is everything else in nature.

Chapter 2 focuses on Darwin’s analogy between natural and artificial selection. This was his original sin and one that has not been expunged from thinking and teaching about evolution. As noted, it is thanks to this analogy that so many still view nature as an actor that selects the best of organisms rather than a set of conditions under which variants provide greater or lesser survival and reproductive benefits. In Chapter 3, I turn to the Galápagos. There, Darwin found the finch, a powerful confirmation of natural selection, but he also found numerous examples of species that did not fit the selection paradigm. These he ignored. The Galápagos archipelago is another icon that must be scrutinized if we are to give selection its due—but not more than that.

Chapter 4 takes on what may be natural selection’s brightest beacon: the human brain. It is a truism that humanity’s evolutionary triumph is a product of our brains. Without our intellect, we would never have become the dominant species on earth. But if the brain is natural selection’s greatest work, then too much is said on behalf of natural selection. The brain is an enormously costly and compromising organ that has almost certainly been the source of death on a massive scale. Tools, fire, and rudimentary language could not counterbalance the toll taken by this most voracious of all organs. All other members of the Homogenus, possessors of brains much bigger than those of the primates, died off. Their extinction is incompatible with the selection of their brains and ours.

In the second part of the book, I elaborate the theory of the good enough, explaining why we should not be surprised that neutrality, excess, and mediocrity persist in nature. In Chapter 5, I begin with a philosophical investigation of neutrality, in hopes that readers will join me in recognizing its constitutive role in nature.

Chapters 6 and 7 present the scientific centerpieces of the theory of the good enough. Chapter 6 offers the strongest evidence against the theory of natural selection: wide phenotypic ranges. In it, I also argue that these ranges, and the excess they reflect, will continue to grow. And I explain more thoroughly the idea of the two evolutions. The first, concerning qualitative variation, is the province of Darwinism and adaptation. The second, concerning quantitative variation, is the province of the good enough and neutrality. Again, natural selection is real; adaptation is real. But much that distinguishes organisms from one another, particularly differences in size, is not adaptive. These variations are not selected; they are tolerated.

Chapter 7 draws on the theory of facilitated variation, developed by Marc Kirschner and John Gerhart, to explain the mechanisms underlying this tolerance. This theory holds that for three billion years, a process of natural selection furnished the biological foundations of all extant creatures. Secured by this sturdy infrastructure, which I call nature’s safety net, organisms have spent the last four hundred million years getting away with much waste and inefficiency. They can afford their waste thanks to highly optimized selected traits, but the waste itself is not selected.

Finally, in Part Three, I apply the theory of the good enough to Homosapiensand consider what it might mean for human societies. Chapters 8 and 9 extend the safety net idea to humanity in order to understand how we might indulge in excess and uselessness and yet be the overwhelming champions in the evolutionary arena. In Chapter 8, I argue that the source of humanity’s magnificence is our uniquely powerful and flexible capacity to project ourselves into the future and to share projects with our fellow humans. No other animals possess this capacity. The future is our safety net. It has saved us from the extinction our brains would have caused, and it continues to save us from the follies our brains never cease to cause.

Chapter 9 considers ways in which this human safety net is also responsible for our species’s unparalleled flourishing and staggering wastefulness. I argue that the future powers a division of labor so thorough that it obliterates all challenge to humanity’s survival, leaving us with a world of free lunches, ease, and boredom. We face no species-level threats except perhaps those ecological ones that are products of unavoidable excess. This excess is unavoidable because we have little to do from a survival standpoint. Humans have the ultimate luxury of wasting time and resources in order to divert ourselves. The skills our ancestors cultivated for the purpose of survival no longer serve that purpose, yet the skills remain. We have the means to achieve ends we no longer need to worry about, so the means become ends in themselves. Our excess bubbles and blooms not because it is selected through a process of struggle but because there is no struggle.

In Chapter 10, I conclude with an exploration of what humanity’s safety net means for ethics, resolving that competition within society is a fool’s game. We need far less excellence than we cultivate. We do it anyway because the best of our neurons, those that rescued us from extinction, are underemployed and overqualified—not because doing so is necessary or even, in many cases, useful. More often, it is crushing. Being excellence-driven myself, I am well placed to know the futility and the masochism of this pursuit. Though our capitalist institutions tell us that we must constantly strive, that nature ordains competition to be the best and reap the rewards, nature in fact offers no rewards beyond survival and reproduction. Both are assured by a safety net that allows us to be just fine even though we are so much less than optimal. Why should we struggle and strain when we are all good enough?

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

accomplish the business he intends, for these reasons. 1. Because there is not the common notion of a spiritual and immaterial being in all or any Man, neither is it (to use his own words) true at first sight to all men in their wits upon a clear perception of the terms, without any further discourse or reasoning, but is only a bare supposition without any proof or evidence at all. 2. The being of an immaterial and spiritual substance can no way incurr into the senses nor affect them, because it is manifest (as Des Cartes hath sufficiently proved) that all sensation is procured by corporeal contact, and not otherwise. And though we deny not that there have been, are and may be apparitions, that cannot be rationally supposed to be the ordinary Phænomena of corporeal matter, yet affecting the senses, there must be something in them that performeth that effect, that is corporeal, or else the senses could not be wrought upon, for immateriale non agit in materiale, nisi eminenter ut Deus. 3. No right deductions can possibly be drawn from the highest power of ratiocination, where the understanding hath no cognoscibility of the things that reason would draw its conclusions from, for as the same Doctor frameth his Axiome which is this: Whatsoever things are in themselves, they are nothing to us, but so far forth as they become known to our faculties or cognitive powers. But we assert (which we shall make good anon) that our faculties or cognitive powers (how far soever some would vainly magnifie and extol them) have not the power of understanding beings that are simply and absolutely immaterial and incorporeal. 4. There is nothing that is more undoubtedly true than what the Lord Verulam hath told us in these words: Causa vero & radix ferè omnium malorum in scientiis ea una est: quod dum mentis humanæ vires falso miramur & extollimus, vera ejus auxilia non quæramus. And again: Subtilitas naturæ subtilitatem sensûs & intellectûs multis partibus superat, the which may be proved from many undeniable instances, which need not here be mentioned, only we shall add what the aforesaid learned Lord speaks to the same purpose which is this: “The fault of sense is twofold: For it either forsaketh or deceiveth us. For first there are many things that escape the sense, though rightly disposed, and no way impeded either by the subtilty of the whole body or by the minuteness of the parts, or by the distance of place, or tardity and velocity of motion, or by the familiarity of the object, or by reason of other causes. Neither again, where the sense doth

apprehend the thing, are those apprehensions sufficiently firm. For the testimony and information of sense is always from the Analogie of Man, not from the Analogie of the Universe.” And it is altogether asserted with great error, that sense is the measure of things. Neither can these notions the Doctor would make so clear, be had or gathered, without some intimation from some of the senses.

Immortal. p. 21.

An Antidot. &c. p. 12.

2. Further the Doctor tells us that the Idea of a Spirit is as easie a notion, as of any other substance whatsoever. And he also saith: “Nevertheless I shall not at all stick to affirm, that his Idea or notion (speaking of God) is as easy as any notion else whatsoever, and that we may know as much of him as of any thing else in the World.” This later he speaketh concerning God. But that these assertions are unsound, these following reasons will sufficiently evince.

Reas. 1.

1. He doth define a Spirit thus: A Spirit is a substance penetrable and indiscerpible. Now if it be true that he affirms before, that, “the subject, or naked essence, or substance of a thing is utterly unconceiveable to any of our faculties, and that if we take away aptitudes, operations, properties and modifications from a subject, that then the conception vanisheth into nothing, but into the Idea of a meer undiversificated substance, so that one substance is not then distinguishable from another, but only from accidents or modes, to which properly belongs no subsistence.” So then if we take away penetrability and indiscerpibility, which are but the modes and properties of a Spirit, whose genus he maketh substance to be, then it vanisheth into an indistinguishable notion, and so his definition comes to nothing.

Reas. 2.

2. For if substances be known by their properties and modifications, as we grant they are, the modifications and properties must of necessity be some ways known unto us: but there are no ways either by common notions, evidence of the senses, or sound deductions of reason that can certainly inform us of these properties or modifications of penetrability and indiscerpibility, and the Doctor yet never proved either; but is only a bare supposition, and a melancholy figment.

The Immort. p. 68.

Reas. 3.

De Inject. p. 598. De Natur. Subst. Energ. p. 406.

3. He tells us that all substance has dimensions, that is, length, breadth and depth, but all has not impenetrability, and boldly saith: It is not the Characteristical of a body to have dimensions, but to be impenetrable; to which we answer. It is strongly asserted by learned Helmont, that by the ultimate strength of nature, bodies do sometimes penetrate themselves and one another, and to that purpose he giveth convincing examples, and concludeth thus from them. Invenio equidem, naturæ contiguam dimensionum penetrationem, licet non ordinariam. And after saith thus: Quibus constat corpora solida, satis magna, penetrasse stomachum, intestina, uterum, omentum, abdomen, pleuram, vesicam, membranas inquam, tanti vulneris impatientes. Id est, absq; vulnere cultros per istas membranas transmissos. Quod æquivalet penetrationi dimensionum, factæ in natura, absq; ope Diaboli. And to the same purpose that most acute person, Dr. Glisson, handling this very point saith: Verum enimverò, si sola quantitas actualis sit causa impenetrabilitatis corporum (ut ex supra dictis liquet,) eaq; sit naturaliter mutabilis; quid impedit ne substantia materialis aliam substantiam, mutatâ quantitate, novâq; simul assumptâ utrisq; communi, penetret? And therefore we may as confidently deny his assumption, that Impenetrability is the Characteristical of body, as he affirm it without proof, and must with all the whole company of the learned, assign Extension to be the true and Genuine Character of Body. And further he granting that substance hath length, breadth, and depth, we must of necessity conclude, that whatsoever hath those properties must needs be material and corporeal, and so that which he would make to be Spirit is meerly Body.

Reas. 4. Nov. organ. p. 18.

4. Whereas he saith that the notion of Spirit is as easy a notion, as any other whatsoever, it is granted, but is not at all to the purpose: for our inquiry need not be of the facility of a notion, but of the verity of it, that is, of the congruity and adequation of the notion and the thing from whence it is taken; otherwise though the notion be easy, yet without an adequate congruity to the thing it is meerly false. As for instance, when a melancholy person doth verily imagine himself to be changed into a Wolf or Dog, it is not only an easy notion, but also it is truly a

notion, and yet a false notion, because there is no true congruity betwixt it and the thing from whence it is taken, the Body of the person so conceiving, being not at all changed into Wolf or Dog, but still retaining its humane shape and figure. And therefore the Lord Verulam doth to this point speak truly and clearly in these words: Itaq; si notiones ipsæ mentis (quæ verborum quasi anima sunt, & totius hujusmodi structuræ ac fabricæ basis) malè ac temere à rebus abstractæ, & vagæ, nec satis definitæ & circumscriptæ, deniq; multis modis vitiosæ fuerint, omnia ruunt. And therefore the Doctor might very well have considered, whether these his new notions had been fitly and rightly drawn from the things, to which he doth so confidently affix them, before he had so boldly asserted them, which though they be truly his notions, that is, that he did think, conceive, and frame them, yet they are not truly abstracted from the things: And so he may be rather judged to be led by speculative and Philosophick Enthusiasm, than by the clear light of a sound understanding.

Job 11. 12.

Reas. 5.

1 Kings 8. 27.

5. And concerning his Tenent that the Idea or Notion of God is as easy as the notion of any thing else whatsoever, that the notion may be easy we grant; but whether it be true and adequate, there lies the question. For those old Hereticks that held that God had Eyes, Ears, Head, Hands and Feet and the like, had an easie notion of it, conceiving him to have humane members, but I hope the Doctor will not say that this notion of theirs was a notion truly drawn from the nature and being of God, because there is no corporeity in him at all. And it is and hath been the Tenent of all Orthodox Divines, Ancient, Middle and Modern, that God in his own nature and being is infinite and incomprehensible, and therefore there can no true and adequate notion of him, as being so, be duly and rightly gathered in the understanding of creatures; and so the Doctors position or notion must needs be Phantastry and imaginary Enthusiasm. For as there are many things in nature that in themselves are finite and comprehensible, that as he grants of naked essence or substance are utterly unconceivable to any of our faculties; much more must the being of God that is infinite and incomprehensible, which are attributes that are incommunicable, be utterly unconceivable to any of our faculties. And it is but the vain pride of Mans Head and Heart,

thereby to magnifie his own abilities, whereas the Text doth pronounce this of him, For vain man would be wise; though he be born like a wild ass colt; that lifts him up to conceit that he can fathom and comprehend the Infinite and Almighty, whom the Heaven of Heavens cannot contain, and therefore cannot frame a true notion of him, whom perfectly he doth not understand nor comprehend, and the attributes of God are matters of Faith and not the weak deductions of humane reason.

Origin. sacr. l. 2. c. 8. p. 233, 234.

3. Those that seem to idolize humane abilities and carnal reason, have not only applied those so much magnified Engines to the discovery of created things, wherein they have effected so little, that sufficiently proclaims the invalidity of the instruments or the inauspicious application of them, or both, all the several sorts of Natural Philosophy hitherto found out, or used, being examined, coming far short of solving the Phænomena of nature, when even the least animal or vegetable affords matter enough to puzzle and nonplus the greatest Philosopher, so that we may justly complain with Seneca, that the greatest part of those things we know are the least part of those things we know not; These engines (I say) though proving ineffectual to find out the true notions and knowledge of natural things, have also (like the fiction of the Gyants) notwithstanding invaded Heaven, and taken upon them to discover and determine of Celestials, wherein it is in a manner totally blind, or sees but with an Owl-like vision. For indeed the deciding of this point must be taken from the Divine authority of the Scriptures, and the clear deductions that may be drawn from thence; for this is that clear light, that we ought to follow, and not the Dark-lanthorn of Mans blind, frail and weak reason, for it is a sure word of Prophecie whereunto it is good to take heed, and not to vain Philosophy, old Wives Fables, or opposition of Sciences falsly so called. And therefore we shall conclude this point here concerning the corporeity or incorporeity of Angels with that Christian and learned position of Dr. Stillingfleet in these words: “But although Christianity be a Religion which comes in the highest way of credibility to the minds of Men, although we are not bound to believe any thing but what we have sufficient reason to make it appear that it is revealed by God, yet that any thing should be questioned whether it be of Divine revelation, meerly because our

reason is to seek, as to the full and adequate conception of it, is a most absurd and unreasonable pretence.”

Gen. 2. 7. Eccles. 3. 21.

4. In handling this point of the corporeity or incorporeity of Angels, we do here once for all exclude and except forth of our discourse and arguments the humane and rational Soul as not at all to be comprised in these limits, and that especially for these reasons. 1. Because the humane Soul had a peculiar kind of Creation differing from the Creation of other things, as appeareth in the words of the Text. And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul. Upon which the note of Tremellius and Junius is, anima verò hominis spiritale quiddam est, & divinum. 2. Because I find Solomon the wisest of Men making this question: who knoweth the spirit of man, that goeth upward: and the spirit of the beast, that goeth downward to the earth? 3. Because it is safer to believe the nature of the Soul to be according to the Analogy of Faith, and the concurrent opinion of the learned, than to sift such a deep question by our weak understanding and reason. So having premised these things, and left this as a general exception and caution, we shall proceed to the matter intended in this order.

2 Cor. 3. 17.

John 4. 24.

1. We lay it down for a most certain and granted truth, that God simply and absolutely is only a most simple spirit, in whom there is no corporeity or composition at all, and what other things soever that are called or accounted spirits are but so in a relative and respective consideration, and not in a simple and absolute acceptation. And this is the unanimous Tenent of the Fathers, Schoolmen and all other Orthodox Divines, agreeing with the plain and clear words of the Scripture, as, God is a spirit, and they that worship him, must worship him in spirit and in truth. And again: Now the Lord is that spirit, and where the spirit of the Lord is there is liberty. Therefore we shall lay down this following proposition.

2. That Angels being created substances, are not simply and absolutely incorporeal, but if they be by any called or accounted spirits, it can but be in a relative and respective sense, but that really and truly they are corporeal. And this we shall labour to make good

not only by shewing the absurdities of that opinion of their being simply spiritual, but in laying open the unintelligibility of that opinion, and by answering the most material objections.

Argum. 1. Argum. 2.

1. And first to begin at the lowest step, Body is a thing that affecteth the senses most plainly and feelingly; for though many bodies are so pure, as the air, æther, steams of the Loadstone, and many other steams of bodies, that they escape the sight of our eyes, yet are they either manifest to our feeling, or otherwise made manifest by some sensible effect, operation, or the like; yet for all this, the intrinsick nature of body as such is utterly unknown unto us, for when we speak of the extension of body, as its Characteristical property, we do but conceive of its superficial dimensions, its internal nature quatenus Corpus, being utterly unknown unto us; it being a certain truth, that Quidditates rerum, non sunt cognoscibiles; and as Dr Moore granteth, the naked essence or substance of a thing is utterly unconceiveable to any of our faculties. From whence we argue, à minori ad majus, that if the substance of a body, whose affections and modifications do fully incur into, and work upon our senses, be utterly unconceiveable to any of our senses, much more of necessity must the substance of a Created spirit, conceived as immaterial and incorporeal, be utterly unconceiveable to any of our faculties, because it hath no effects, operations, or modifications that can or do operate upon our senses.

2. And as we know not the intrinsick nature of body, so also we are ignorant of the highest degree of the purity and spiritualness of bodies, nor do we know where they end, and therefore cannot tell where to fix the beginning of a meer spiritual and immaterial being. For there are of Created bodies in the Universe, so great a diversity, and of so many sorts and degrees of purity and fineness, one exceeding another, that we cannot assign which of them cometh nearest to incorporeity, or the nature of spirit. And many of these being compared with other more gross and palpable bodies, may be and are called and accounted spirits, though notwithstanding they be all Corporeal, and but under a gradual difference. So the vital part in the bodies of men are by Physicians called Spirits in relation to the bones, ligaments, musculous flesh and the like; nay even in respect of the blood,

lymphatick humor, lacteal juyce, or the succus nutritius nervosus, and yet still are contained within the limits of body, and are as really Corporeal as any of the rest, and so are the air and æther. And those visible species of other bodies that are carried in the air and represented unto our Eyes, by which we distinguish the shape, colour, site and similitude of one body from another, though by the Schools passed over with that sleight title of qualities, as though they were either simply nothing, or incorporeal things, are notwithstanding really Corporeal, else they could not incur into, nor affect the visive sensories: And these do in the air intersect and pass through one another (as may be optically demonstrated) without Confusion, Commixion, or discerpsion, and may comparatively be accounted spirital and incorporeal, though really they be not so. But what shall we say to that wonderful body, Image or Idolum of our selves, and other things that we behold in a mirrour or looking-glass? must this be a meer nothing, or an absolute incorporeal thing? surely not. For it is as really a body as any in the Universe, though of the greatest purity and fineness of any that we know; and how near it approaches to the nature of spirit, is very difficult (if not impossible) to determine; for if it did exist when the body or subject from whence it floweth were removed, it might rationally be taken for a Spirit, and with far more probable ground than many things else that have been vainly supposed to be Spirits. And that these visible shapes of things, and this Image in the glass, are not meerly imaginary nothings, but Corporeal Figures and steams, is most manifest, because they vanish when the body or subject is removed, because that nullius entis nulla est operatio, & Incorporeum non incurrit in sensus, and because they would pass through the glass, but only for the foil or Bractea laid on the otherside, by which the Image is reflected. So that if we have bodies of so great purity, and near approach unto the nature of spirit, we cannot tell where spirit must begin, because we know not where the purest bodies end.

3. Dr Moore maketh substance to be the genus, and spirit and body to be the two species, so that body and spirit are of one generical Identity, and so there must of necessity

Argum. 3. The Immortal. of the Soul. Axiom. 2. p. 6.

De natura substant. Energetic. c. 27. p. 379.

some certain specific difference betwixt them be assigned and proved, or else the division is vitious, and the property of spirit not proved, and so their opinion of spirit falls totally to the ground. For we affirm (and shall prove) that though a difference be imagined and supposed, yet it was never yet sufficiently proved, for omnia supposita, non sunt vera, otherwise all the impossible figments and vain Chimæras of melancholy and doting persons might pass for true Oracles: but it is one thing truly to understand, and another thing to imagine and fancy what indeed is not, nor ever was. And though the supposition seem never so probable and like, yet it will but at the best infer the possibility of such an imagined difference, but not prove it really to be so, and therefore here we shall retort the Doctors Axiom against him, which is this: “Whatsoever is unknown to us, or is known but as meerly possible, is not to move us or determine us any way, or make us undetermined; but we are to rest in the present light and plain determination of our own faculties.” Now that a spirit is penetrable and indiscerpible, may be imagined as possible to the fancies of some, but cannot be clearly intelligible to any sober mind; for to imagine, and to understand, are faculties that are very different, and however if such a difference be conceived as possible (which cannot enter the narrow gate of my Intellect) yet the difference of being penetrable and indiscerpible, is not to move us to determine that a spirit hath those distinct properties from bodies, because they are but known to us as meerly possible. And therefore that these two differences of penetrability and indiscerpibility assigned by Dr Moore, are not sufficiently proved to be so, we shall give these reasons. 1. If bodies in the ultimate act of nature can penetrate themselves and one another, as Helmont and Dr Glisson do strongly labour to prove, then penetrability is not the proper difference of spirit from body, because then common to them both. 2. But if it be taken for a truth (and the one of necessity must be true) that bodies do not, or can possibly penetrate themselves or one another, as the common tenent holdeth, and seemeth most agreeable to verity, for it is simply unintelligible and impossible to conceive, that two Cubes (suppose of Marble or Metal) should penetrate one another, and yet but to have the dimensions of one, and to possess no greater space than the one did formerly fill: And if this be impossible and unintelligible in respect of bodies, whose properties, aptitudes, affections and modifications are apparent to our senses,

then must it be more impossible and unintelligible in substances supposed to be meerly incorporeal, because they must needs be more pure and perfect, and therefore less subject to such unconceiveable affections; and however, it can be no wayes known to our faculties or cognitive powers, that they have any such specifical property or affection. 3. As it is not any way manifest to any of our senses, nor can be proved by any sound deductions of reason, so it cannot be manifested to be any innate notion shining from the Intellect it self, and we ought not to take adventitious ones instead of those that are innate, nor fictitious ones for either, but to make a due distinction of each of them one from another. 4. Neither is indiscerpibility a proper difference of a spiritual substance from a corporeal one, because the visible species of things do in the air intersect one another, and suffer not discerpibility: and that these are bodies is manifest, because they affect the senses; and therefore that which is a property of some bodies cannot be the proper difference to distinguish a spirit from a body. 5. This is only an arbitrary and feigned supposition, and cannot be proved either by the testimony of any of the senses, by sound reason, or innate notions; and what is or cannot be proved by some of these (according to his own position) ought to be rejected. And therefore as indiscerpibility is no proper difference of a spirit from a body, no more is penetrability, which can no more be in a spiritual substance, than either in discreet quantity one can be two, or two one, or in continuate quantity one inch can be two, or two can become one. Dr Glisson from his much admired Suarius the great Weaver of fruitless Cobwebs, hath devised another difference of spirit from body which he thus layeth down, as we give it in this English. “I assign (he saith) a twofold difference betwixt the substance of matter and that of spirits. The first is taken from the substantial (à substantiali materiæ mole) heap or weight of the matter. For I (he saith) besides the actual and accidental extension, do attribute to the matter this substantial heap or weight which is denied to spirits. But the sign of this heap or weight is, that if the matter in the same space be duplicated, triplicated, or centuplicated, that it will be made more dense twofold, threefold, or an hundred fold. And concludeth thus: I answer (he saith) that matter and spirit in this do agree betwixt themselves, that they both are finite, and from thence that they have this common, that neither of them can reduce themselves into a littleness that is infinite, or into an infinite

magnitude. Therefore the difference betwixt them doth not consist in this; but in this, that a spirit whether it be contracted or dilated, is not made more dense or rare; but on the contrary, matter, whether it be contracted or expanded, is made more dense, or more rare.” To which we return this responsion. 1. It is usual with men, when by their wills and fancies they would maintain an opinion that is weak and groundless, finding they cannot clearly perform it, to bring in some strange, obscure or equivocal word, thereby to make a flourish, though they prove nothing: So here this learned person to make a shew to prove the difference of spirit doth assign moles substantialis as peculiar to body, but not to spirit; but what is to be understood by moles, he might know his own meaning, but I am sure there are few others that do or can understand it, and therefore is but a devised subterfuge to stumble and blind mens intellects, and not to prove the thing intended. 2. If by the word moles he intend weight or gravity (and what else it can signifie is not intelligible) then it will not be a difference betwixt body and spirit, because gravity and levity are differences of bodies in respect of one another, and therefore can be none as he assignes it. 3. To assert that a spirit when contracted or dilated is not made more dense or more rare, but that matter whether it be contracted or expanded, is made more dense or more rare, is easily spoken, but not so easily proved: and rude assertions without sound proof, are of no validity, and may with as good reason be denied and rejected, as affirmed or received. 4. We have no density in bodies but in respect of the paucity and parvity of the pores, so that less of another body is contained in them, and that is accounted rare that hath many or greater, and so containeth more of another body in them, and are qualities or modifications that only belong unto bodies, and not at all unto spirits, and is but precariously taken up by the Doctor without any proof or demonstration at all. 5. If spirits cannot expand themselves into an infinite space, nor contract themselves into an infinite littleness, then where are bounds and limits of this contraction and expansion, or how is it proved that they can do either? seeing they are properties and affections of bodies and matter, and never were proved to be peculiar to spirits.

Argum. 4.

4. Those that are much affected to and zealous for experimental Philosophie, do often run into that extream, as utterly to condemn and throw away

all the ancient Scholastick Learning, as though there were nothing in it of verity or worth: But this is too severe and dissonant from truth, as might be made manifest in many of their Maximes; but we shall only instance in one as pertinent to our present purpose, which is this: Imaginatio non transcendit Continuum. And this if we perpend it seriously, is a most certain and transcendant truth; for when we come to cogitate and conceive of a thing, we cannot apprehend it otherwise than as continuate and corporeal; for what other notions soever we make of things, they are but adventitious, arbitrary, and fictitious, for even non entia ad modum entium concipiuntur. And therefore those that pretend that Angels are meerly incorporeal, must needs err, and put force upon their own faculties, which cannot conceive a thing that is not continuate and corporeal: But if they will trust their own Cogitations and faculties rightly disposed, and not vitiated, then they must believe that Angels are Corporeal, and not meerly and simply spirits, for absolutely nothing is so but God only.

Argum. 5. Vid. Rob. Fludd. utri. Cosm. Hist. Tract. 1. l. 4. c. 2. p. 110.

5. If the Angelical nature were simply and absolutely spiritual and incorporeal, then they would be of the same essential Identity with God, which is simply impossible. For the Angels were not Created forth of any part of Gods Essence, for then he should be divisible, which he is not, nor can be, his Essence being simplicity, unity, and Identity it self, and therefore the Angels must of necessity be of an essence of Alterity, and different from the essence of God. Now God being a simple, pure, and absolute spirit in the Identity of his essence, if the Angels were simply and absolutely spiritual and incorporeal, then they must be of the same essence with him, which is absurd and impossible; and therefore they have Alterity in them, and so of necessity must be Corporeal, and not simply and meerly spiritual. And that as much as we contend for here is granted by Dr Moore in these words: “For (he saith) I look upon Angels to be as truly a compound Being consisting of soul and body, as that of men and brutes.” Whereby he plainly asserteth their Composition, and so their Alterity, and therefore that they must needs have an Internum and externum, as the learned and Christian Philosopher Dr Fludd doth affirm in these words: Certum est igitur inesse ipsis (scilicet

Angelis) aliud, quod agit, aliud autem, quod patitur; nec verò illud secundùm quod agunt, aliud quam actus esse poterit, qui forma dicitur; neq; etiam illud secundum quod patiuntur, est quicquam præter potentiam, hæc autem materia appellatur.

Argum. 6. Serm. 6 sup. Cantic. p. 505.

Lib. 5.