Introduction

Infrastructures make empires. The economic, social, and cultural systems of empires are guided by and given form and purpose through canals, bridges, tunnels, ports, and, perhaps most importantly, railways. It is no coincidence that infrastructures are often likened to the veins, nodes, and capillaries of organic bodies: they are the stu of life. The power that infrastructure had in the early globalizing world, during the Age of Empire, as Eric Hobsbawm famously described it, also signaled profound imbalances on the world stage, where multiple organisms competed for their share of physical presence.1 In the colonial world, infrastructure was grafted onto territory and often served as a form of exploitation, exhausting the body that hosted it. For every heroic accomplishment of modernity in, for example, France or Britain, there was also, across a sea or an ocean, a landscape of parasitic infrastructure. Yet infrastructure across empires also transcended the binary parasite-host relationship, and the vast gray zone between binary formations is the subject of this book. Symbiotic rather than parasitic, dynamic rather than statically hegemonic, many global infrastructures in the Imperial era were dened in the interstices between the cliché dialectics of metropole and colony, and sovereignty

and dependency. Empires that desired infrastructures they themselves could not build, owing to lack of technical expertise or nancial resources, or that had these resources but did not have the explicit mandate to impose them elsewhere, led to the transfusion of infrastructure across rather than within imperial borders.

This book looks at one such transfusion in depth and explores it for the many broader lessons it holds for the history of infrastructure as well as the history of globalization: the Ottoman railway, a massive physical network of railway lines, stations, monuments, and institutions, conceived by the Ottoman sultan and considered the pride of that empire’s modernizing impulses. It was, also, an infrastructure engineered predominantly by German rms, constructed with German materials such as Krupp steel, and nanced by German banks such as Deutsche Bank over the course of a half century, beginning in 1869. While the project employed local builders and craftsmen and advanced Ottoman goals of imperial consolidation and modernization, it also accelerated German inuence in the increasingly circumscribed yet still vast territory of the Ottoman empire, setting the stage for an ambiguous power dynamic that placed infrastructure at the center.

This book looks at the German-Ottoman relationship specically through the art-historical prism of objects: train stations, paintings, urban byways, maps, bridges, monuments, photographs, and archaeological artifacts, which I will often read against the prevailing grain. Through its examination of four discrete subsections of the Ottoman railways including the railways of European Turkey (1871–91), the Anatolian Railways (1873–99), the Baghdad Railway (1899–1918), and the Hejaz Railway and its Palestinian tributaries (1900–1908) this book frames the art of infrastructure as one that is multifaceted, born as it is of eight specic contexts through which objects tell stories: political, geographical, topographical, archaeological, constructional, architectural, monumental, and urbanistic. Not only did these contexts serve to shape this infrastructure; they were in turn forever changed by it.

I provide here a new way of looking at the production of cultural artifacts from small portable objects such as maps to massive public monuments in ambiguous contexts such as the German-Ottoman relationship, in which relations were not premised on the abdication of one party’s political sovereignty. One could draw a number of productive parallels with certain historical settings in China, Persia, Thailand, and Ethiopia, among many others. The ambiguously colonial German-Ottoman relationship helps us to understand the dynamic and artistically productive conditions that can coalesce in the gray zone between the sovereign and colonial states. This book also contextualizes the railways’ construction in a formative moment in the internationalization of the design professions, revealing the project’s wider importance to the history of multicultural design.

This book has two parts that develop its themes cumulatively as well as in scalar sequence. Chapters 1 to 4 describe the objects that come to life through the construction of knowledge, beginning with the macro scale of political knowledge and then proceeding downward in scale toward the earth, the building block of geographic, topographic, and archaeological knowledge. Then Chapters 5 to 8 describe the objects that come to life through a dierent construction the construction of form by moving upward in scale, beginning with the role of the individual worker and subsequently considering the building, the public monument, and the city.

In this book, I highlight the similarities as well as the dierences among the constituent lines of the Ottoman railway network and contextualize them within a span of

time that corresponds, on the one hand, to an era of German ascendancy on the global stage and, on the other, to the inversely proportional unraveling of the Ottoman empire. I bring to this study my own lens and inevitable subjectivity as an interpreter and an architectural historian. This study coalesces the existing, partitioned literature on the railways’ histories and builds on them through an expansive evaluation of previously unstudied objects and unpublished archival sources originating, in order of magnitude, from Germany, Turkey, Austria, the United Kingdom, Israel and the Palestinian territories, the United States, and France. This book also deliberately uses objects as original rather than representational evidence.

While the book is subdivided into topical categories, historiographical and conceptual concerns unify it. Although these concerns overlap and cross-pollinate, we can divide their subject matter into three main themes that punctuate my study of empire and infrastructure: geopolitics, multiculturalism, and expertise. I use the term “geopolitical” to describe historical discursive contexts synchronic with the railways’ construction and specic to the German and Ottoman statecraft that simultaneously produced geopolitics as a discipline in Germany and the Ottoman railway network as a site in the Ottoman empire. In the wake of the geographer Alexander von Humboldt’s pioneering work on the natural world in the nineteenth century, the discipline of geography expanded, giving rise to new disciplines that included cultural geography, social geography, and geopolitics. Although historians debate the intellectual origins of the term “geopolitics,” they generally agree that Friedrich Ratzel was its rst champion.2 Ratzel developed the widely inuential concept of “the state as organism.” This theory conceptualized the polity as a natural phenomenon and prompted the rethinking of borders as mutable xtures akin to the membranes of cells, not unlike the way in which infrastructure has been introduced in this book as a process of transfusion; it was at this point that our biological analogy for empire was transmuted from an abstract concept to a process with physicalform.3

The concept of the state as organism is relevant to this book on several levels. First, it establishes the leitmotif of connective networks, akin to circulatory, digestive, or nervous systems, and oers a conceptual backdrop to what has been described as the mobility turn in contemporary scholarship.4 Second, the concept provided the German state

with a way to strategize its power as land-based, predicated on its organic, contiguous sense of its own political body. After the Dual Alliance of 1879 with the neighboring Austro-Hungarian empire, a land-based superpower stretching from Hamburg to the Persian Gulf was realizable with Ottoman participation, and could constitute a land “wall” that blocked the powers of Western Europe on one side and the Russians on the other. This emphasis on land stood in contradistinction to the maritime xations of France and Britain and the colonial orbits that their seabased power realized and maintained.

Conceiving an entity such as the German-Ottoman railway network in artistic terms requires new expository methods of description and conceptual paradigms, and “multiculturalism,” a term whose currency has atrophied in recent decades, is worth reconsidering to this end. While the term has come to describe armative qualities of a diversity of ethnic, racial, and religious groups within a social and political unit, earlier uses of the term seemed more concerned with the inherent complexities of cultural multivalency, an interest that I share. Jürgen Habermas has considered the character of multicultural societies from this standpoint, eliding moral value in favor of analyses of operative dynamics.5 Elemental to this understanding of multiculturalism are the many historical contexts in which knowledge and emancipation developed in culturally pluralistic political bodies. In the cases of the newly unied German empire, forged from a constellation of duchies, diets, and microstates, and the Ottoman empire, with its long-standing and constituent multicultural organization, some unexpected synergy emerges.

It is important to note that the framework in which this synergy produces objects is dierent from the conventional power/knowledge relationship produced through Orientalism, the monolithic metric of Europe’s encounter with the Middle East at the time. It is also worth remembering that Edward Said, the father of Orientalist critique, thought of German Orientalism as a benign entity:

The German Orient was exclusively a scholarly, or at least a classical Orient: it was made the subject of lyrics, fantasies, and even novels, but it was never actual, the way Egypt and Syria were actual for Chateaubriand, Lane, Lamartine, Burton, Disraeli or Nerval. There is some signicance in the fact that the two most renowned German works on the Orient, Goethe’s Westöstlicher Diwan and Friedrich Schlegel’s Über die

Sprache und Weisheit der Indier, were based respectively on a Rhine journey and on hours spent in Paris libraries. What German Oriental scholarship did was to redene and elaborate techniques whose application was to texts, myths, ideas, and languages almost literally gathered from the Orient by imperial Britain and France.6

This book suggests that this “redenition” and “elaboration” of scholarly techniques is constitutive of what is known in modern terms as “expertise”: the application of scientic knowledge to a pragmatic or real-world end, as in the production of objects and images. In a letter to the editor of the New York Times in 1853, Karl Marx summed up how this functioned between Germany and its interlocutors in the Orient: “German philologists and critics have made us acquainted with its history and literature. . . . But the diplomatic wiseacres seem to scorn all this, and to cling as obstinately as possible to the traditions engendered by Eastern fairy-tales.”7 The German construction of the Ottoman railways broke through this obstinancy, engendering a new relationship between Orientalist knowledge and real-world practice that showcases “expertise” as the bridge between the German study of the Orient and its material engagement with it. Did Said dismiss the German Orient as irrelevant too soon?

Suzanne Marchand has suggested that Germanspeaking Central Europeans conjured a counterdistinctive “Orient” premised on a longing to understand the Near East as a basis for interpreting the New Testament, biblical lands, and the history of Christianity.8 This is certainly one way to consider an image of the kaiser’s visit to the Temple Mount in 1898 (g. 0.1). Marchand’s thesis is convincing, and it is also important to note that it would only be scholars, not professional experts such as railway engineers or architects, who would have this humanistic preoccupation. The delivery of German expertise in rail construction to the Ottoman empire was not an Orientalist endeavor per se, but it did draw upon earlier forms of Orientalist knowledge and provided a veritable cause for the acceleration of its production. Marchand contends that German Orientalism laid the foundations for multicultural thinking but was unable to develop it.9 This book suggests an expansion of this idea, revealing the impact of Orientalist knowledge on professionals who made things, not just those who studied them. The pragmatic professional forms of multicultural engagement evident across the range of knowledge produced in the German construction of the Ottoman railway

network shaped a modern, multicultural visual logic, a logic whose evolving contours have in turn shaped modernity and imaged the global context in which we live today.

Zeynep Çelik has masterfully read infrastructure in the late Ottoman empire as a topic for visual and cultural study, and has pioneered an integrative approach to the study of infrastructure and architectural history (two elds that were literally conated by the railways’ engineers); it is my hope in this book to further that agenda but also to take it in new directions. In two publications, The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century and Empire, Architecture, and the City: French-Ottoman Encounters, 1830–1914, Çelik touches upon a few of the monuments and places that I discuss in this book and considers them in a broader context that she describes as the Ottoman empire’s “idiosyncratic modernity.”10 One of the main sources for this idiosyncrasy, Çelik argues, is the ambiguously colonial nature of the Tanzimat reforms, a series of modernizing eorts internal to the Ottoman empire, and the role these reforms played in the attempts to coalesce the Arab fringes of the empire into an ordered, Ottoman image.11 Çelik’s supposition that there are colonial currents internal to late Ottoman culture is buttressed by her analysis of French colonial activity in neighboring North Africa and the “uneven” trac of the “two-way street” connecting these parallel empires.12 If the French-Ottoman comparison is one of parallel streets with byways facilitating dialogue and the

testing of models, then the German-Ottoman relationship may more aptly be described as a coaxial thoroughfare, an indivisible conduit with interests and information moving in either direction at all times. It is this intrinsic complexity that I nd so interesting, and it is this analogy that distinguishes my analysis from those before it, which have maintained that there are always two separable bodies forming a colonialcondition.

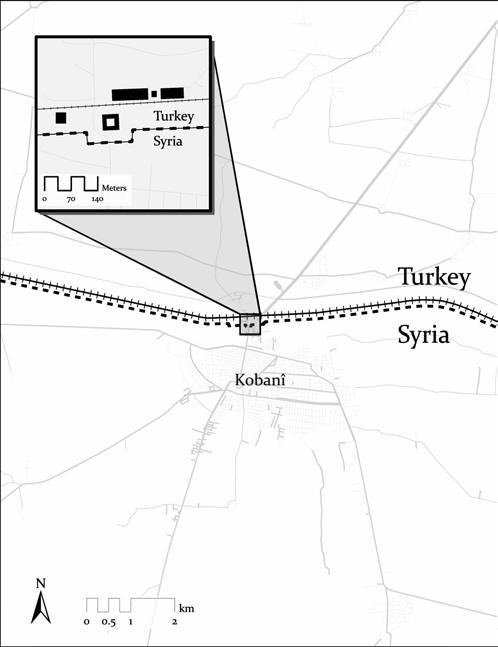

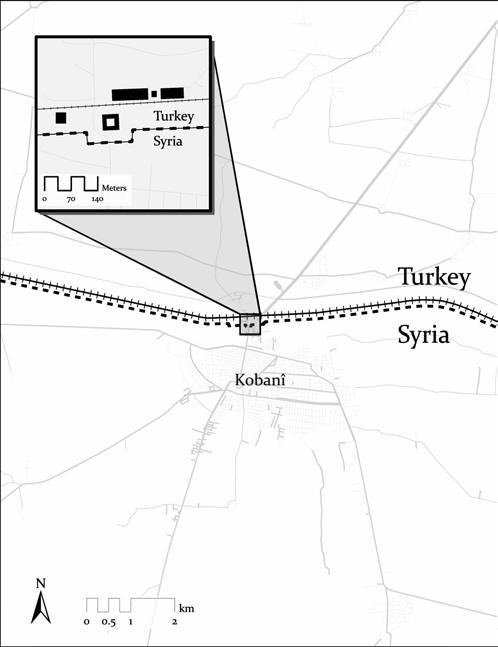

This book was researched and written against the backdrop of intense geopolitical change in the places it studies. Because I believe that the craft of art history has its own intrinsic value and relevance, and because there will certainly be continual change after this book is published, I have resisted the urge to cast its story of imperial infrastructure in teleological terms. Yet, as I have followed the news, I have been constantly reminded of the remarkable velocity of history and the symbolic endurance of these railways for the contemporary world. In the aftermath of World War I, the border between Turkey and Syria was drawn as a sinuous, articial line that was shaped by the southern edge of the railway bed. For example, the point at which the railway station for the city of Kobani (Çobanbey) was built creates a sudden rupture in the line, gerrymandering just a bit to the southern ank of the railway bed and creating the nodal point of a border crossing (g. 0.2). Infrastructure, like rivers and mountains, makes borders that have long-lasting impact.

FIG. 0.1 Kaiser Wilhelm visiting the Dome of the Rock, 1898. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The case of Kobani demonstrates the interdependency of the specic and the universal in history. We understand the importance of the historical specicity of how and why the German engineers and Ottoman builders shaped the city as well as how colonial and Orientalist legacies writ large continue to pregure and to haunt so many contested spaces across the globe that resemble this one. Yet the paradigms that postcolonial studies oer us have largely bypassed ambiguous contexts the international milieux where the dynamics of knowledge and power, famously described by Michel Foucault, were muddled by the absence of a formal abdication of sovereignty. The German construction of the Ottoman railway network is a seminal case in point. For one, the railway, the ultimate “metonym for modernity,” represented the Ottoman empire’s most signicant and self-propelled modernization eort in the nal half century of its existence.13 While the Tanzimat reforms, with their emphasis on naa (amelioration), recast society, the railway went one step further in radically renovating the built environment and the spatiotemporal relationships of its people. At the same time, the railway network also represented the empire’s most synthetic eort to transmute Western technology and naturalizemodernity.

In several regards, the exportation of railway technology and the development of railway infrastructure within the Ottoman empire mirrored developments elsewhere in the non-Western world, particularly in Russia, Japan, and Latin America. Impressed by the American engineer George Washington Whistler’s use of steep grades, sharp curves, and advanced machinery, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia installed Whistler as chief engineer for the earliest railroad in Russia, connecting Moscow and St. Petersburg.14

Second to building the actual line, Whistler’s largest accomplishment was the construction of a massive foundry employing over three thousand skilled workers, including many Americans who trained Russian employees in much the same way that German engineers would later advise the Ottomans in the construction of the Hejaz Railway. Whistler maintained that the foundry, alongside the railway itself, could also bring the Russian economy out of the doldrums, and developed it as a site of apprenticeship and technology transfer for a new generation of Russian engineers and skilled laborers.15 In many other ways, the outward-looking nature of Tanzimat culture mirrored that of Meiji-era Japan, which also sought to abolish cultural practices deemed “unmodern” by looking

to the West for inspiration.16 In terms of railway development, this meant an organic mix of Dutch, Russian, American, and British experts who exhibited, consulted, and implemented new railway technologies in Japan.17 The American model of interurban railway networks was particularly appropriate to and adopted in Meiji Japan; in contrast, the railways in less dense Latin America were a skeletal system for agricultural development and the move toward internal colonization, a process that had been mastered by the British in their own colonial holdings.18 In central Argentina, for example, immigrants from Europe, much like the German settlers who would settle in central Anatolia with the construction of the railway there, were brought in to populate new agricultural colonies.19

We nd ourselves in a time that demands a global outlook if not also a global ethic, and these global comparisons alert us to the reverberations of a new international society in the long nineteenth century. But the GermanOttoman context is also valuable for its historical specicity and the monographic lessons it teaches vis-àvis the objects that it made. The coaxial, as opposed to

FIG. 0.2 Map showing the railway and border between Turkey and Syria at Kobani. James Barbero, Blair Tinker. University of Rochester, River Campus Libraries.

networked, kinship that the Ottoman empire was able to foster with Germany was far less lopsided and certainly more dynamic than any other relationship it had with a European power. Imprecise and vague in its ambitions, the German-Ottoman partnership laid the groundwork for a truly spectacular renovation of the built environment from Banja Luka to Baghdad and from Medgidia to Medina, and the objects of this renovation emerge as the evidence of its power. The imperative for global history and the comparative study of empires is premised largely on the ethical idea that no one culture or nation exists in a vacuum. I could not agree more. Yet, as we zoom too far out, this imperative may also lead us toward a texture of writing history that is overly generic and that essentializes the mechanics of discrete historical conditions and personalities. This too, like nationalism, can lead to a form of epistemic violence. Through this monographic study, I attempt to zoom in and out between the forest and the tree to locate myself at a register that essentializes neither a cultural group nor a historical event.

The bipartite structure of this book underscores how objects and artistic representations tether the construction of knowledge and the construction of form. This structure reveals the book’s indebtedness to a particular strain of recent architectural historiography, one that, rather than focusing on issues of architectural style or identity, is more concerned with the social processes through which architecture is constituted.20 But this book also diverges from that strain in its underlying contention that the power/ knowledge dyad formulated by Foucault and later by Said cannot be as monolithic and unambiguous a model for architectural history as it has been. Such a formation betrays the many conditions that exist in the vast, ambiguous margins between sovereignty and colony. In terms of its content, this book’s ambitions are also twofold, seeking, on the one hand, to oer valuable new information on the specic German-Ottoman geopolitical relationship, while also furnishing a transposable conceptual paradigm of intercultural engagement that can permeate, and I hope enhance, the so-called global turn in history.

What is this paradigm? In light of the paucity of language for considering the ambiguous context of the German-Ottoman relationship, this book turns its attention to the problem of ambiguity itself, shedding light on unied (as opposed to diuse), synthetic (as opposed to found), and plastic (as opposed to xed) creations of art and infrastructure. The book’s eort to deploy lexical

terminology anew can be seen as part of a broader eort within postcolonial thinking. Ambiguity, along with its material exponents, functions both descriptively and as code for an abstract process. This renewal and synthesis of our lexicon is what Swati Chattopadhyay has done for the term “infrastructure,” and what Esra Akcan has done for the term and process of “translation,” and my motivations for this project are indebted to eorts such as these.21

For the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, the ambiguity between humans’ inherent “nothingness” (i.e., their immaterial, cognitive world) and their “facticity” (i.e., their physical presence in the world) is precisely what constitutes their presumptive freedom. Ambiguity, as such, represents an inviolable truth as well as an opportunity, when recognized, for emancipation. “To attain truth,” de Beauvoir notes, “man must not attempt to dispel the ambiguity of his being but, on the contrary, accept the task of realizing it.”22 I subscribe to de Beauvoir’s contention that ambiguity is something that is constituted rather than something that merely exists.

Speaking from the eld of literary criticism, William Empson describes ambiguity as the ultimate venue for personal experience. When one says, for example, “He is like a dog,” it may be a metaphor or it may be an epithet.23 In both cases, ambiguity is a process that opens up opportunities, rather than foreclosing them. Discerning the inherently productive nature of ambiguity as a condition is part of my broader interest in this study of discerning and developing ways to understand things created in ambiguous contexts, outside of conventional imperial or colonial conditions where someone’s sovereignty is abdicated or through the exponents of technology transfer. The foregrounding of ambiguity allows me to downplay the characteristic primacy that architectural history places on heroic forms of authorship and that political history places on nationhood; it also avoids the rigid rubrics of style that continue to trap us in a postcolonial and historical lexicon that relies on dualistic terms such as “hybrid” and “import.” In this sense, my study gives ambiguity the opportunity to be anything but what many have assumed it to be: a dead end. This book considers the ambiguous nature of the German-Ottoman railway partnership and the process in which conditions are made ambiguous (“ambiguation”) as the dening characteristic of the railway network and a precondition for the unique qualities of its physical forms.

Additionally, this book oers a new and critical provocation to the established German and Ottoman archi-

tectural- and urban-historical canons. Histories of the late Ottoman empire tend to emphasize two themes. One theme is cosmopolitanism, which stresses the empire’s pluralist society as the inspiration for a move toward a more diverse architectural profession and set of aesthetic idioms. The vogue of cosmopolitanism across cultural studies stems from an ethical position advocating a kinship of humanity and a refutation of patriotism and nationalism. However, cosmopolitanism has had a far more convincing currency in the humanistic elds other than history philosophy, law, politics that emphasize the present and lived condition. The description of historical communities such as the multiethnic Ottomans as cosmopolitan often carries an air of projection or utopian re-narration. It would seem more apt to talk of processes or events, rather than people, as cosmopolitan. The second theme that is commonly emphasized in histories of the late Ottoman empire is modernity. These narratives stress the physical transformations enacted by Tanzimat reforms and the active roles of technology and industry, often with revisionary undertones asserting that “modernization” was not the heroic project of Mustafa Kemal, founder of modern Turkey, and secularism alone, but a project with Ottoman origins and some consonance with Islam.

However, both the cosmopolitan and the modernistic emphases fail to provide a complete portrait. Neither the internal nor the international aspects of the construction of railway infrastructure point to a system of unequivocal mutualism between individuals, as the concept of cosmopolitanism would suggest. While cosmopolitanism may serve as a leitmotif or utopian ambition, it seems rarely to function on a subpolitical level. Relations were far more complex, problem-ridden, and contingent on deeply imbalanced systems. Moreover, narratives that stress autonomous production or contracts coming out of modernity fail to recognize the inherent contradictions, trauma, and duress posed by modernization. To seek deeper origins for Ottoman “modernization,” and even to contend that Ottoman modernization represented a highly deliberate and conceptual orchestration to subsume Western technology and somehow make it a priori Ottoman, is to ignore the cultural transformations wrought by pressure, brute force, unconscious thinking, and awe.

On the German side, the historiographical territory remains even less charted. The German empire did not coalesce until 1871, which gave it a low, uneven international prole at the time. This has created a vacuum for

understanding Germany’s important, if relatively small, forays abroad. This gap in knowledge has been reduced by recent critical considerations of German architecture and city planning in its African and Pacic colonies.24 However, historians have not yet fully examined the German empire’s engagement with the so-called Orient in the last decades of the nineteenth century, despite ample evidence of its importance to numerous internal discourses.25

The scope of my thinking on empire and infrastructure is largely inspired by Marshall Hodgson’s exegesis on the Generation of 1789, which dened the ways in which transformations in the Occident literally fractured the AfroEurasian ecumenical world and subsequently paved the way for European hegemony in the nineteenth century.26 Hodgson rejects the hierarchical accounts of early modern– and Enlightenment-era transformation by placing a unique European metamorphosis into a global historical framework, focusing on processes rather than product and mechanics rather than progress. Islamic culture, having supposedly manifested its orescence prior to Europe’s, had established prescient institutions of “independent calculation” and “personal initiative,” and acclimated its followers to certain tactical and canny ways of being that were not at odds with religion, as they were in the Enlightenment. Infrastructure, as such, was less a transformation of life than of what Hodgson terms European “technicalism,” broadly dened as the primacy of specialized technical considerations over spiritual ones.27 It was this transformation that facilitated the ascendancy and hegemony portended by the state as a technocentric organism.28

So it was that technicalism trumped the boundaries and challenges posed by articial limits such as state borders, language barriers, and “hard to exploit markets,” because that was its modus operandi.29 Western technology in both Islamic and Ottoman culture also stood in internal conict with agrarian social organization, causing a signicant amount of moral and psychological anxiety. Indeed, European technology such as the railways was greeted with immense suspicion at many junctures. As one skeptic put it, “God, who is exalted, has created this kind of thing through the hands of the unbelievers [i.e., the Europeans], in order to lead astray, and deceive, the sinners and the shameless.”30 By the time of the GermanOttoman partnership, technology transfer, particularly in the sphere of railways, had major precedents in Russia and Japan where, as Arnold Pacey has argued, the railway in the non-Western landscape “encouraged a vision of a new

world order somewhat more benign than the imperialist dreams of the Europeans.”31 Matter became mind, and infrastructure became faith.

As the German-Ottoman engagement was patently contractual and deed virtually all other models of the day, the extent to which these dreams were indeed “benign” is precisely what distinguishes it from the axiomatic metanarrative of technology transfer. The creation of this transimperial infrastructure operated beneath rather than above the political, economic, and professional activities of its stakeholders. To understand how varied the eects of this ambiguous relationship could be, one need only look at the multiple roles played by one of the many actors we will meet on this journey: the engineer Heinrich August Meißner, who functioned as a colonist in Mesopotamia and a source of technical expertise in the Hejaz.

In this sense, ambiguity does not connote vagueness or meaninglessness. Rather, it evokes an artistic and morphological duality where two sides are locked in a partnership in which the level of reciprocity of their relationship is continually in ux. Throughout, this book underscores the

contention that ambiguity manifests in both knowledge and form, and demonstrates the mechanics of how it does so. While the process creates numerous objects, its intrinsic juxtapositions model the process of their dialectical constitution. These objects maps, archaeological artifacts, documentary photo albums, bridges and tunnels, train stations, monuments, and city quarters are vast, and they tell fascinating stories. The lessons that the objects of the GermanOttoman case teach us are also transposable to wider circumstances where a sovereign state is penetrated by imperial capital, trade, and inuence while juridical independence is maintained.

In a time of imperatives to think globally, the specicity of place matters more than ever. The focus of this book on the German-Ottoman context is meant to demonstrate the importance of in-depth, “vertical” history within and for the cause of multilateral histories that build on the themes at the center of this book. The terms that accompany this book’s main title “art,” “empire,” “infrastructure” remind us that history becomes form when space is stitched together.

Part One

1 Politics

Tout le monde içi demande une concession, l’un demande une banque, l’autre une route.

Çe nira mal-banque et route-banqueroute.

—attributed to Mehmed Fuad Pasha, grand vizier of the Ottoman empire, 1866

AffNITIES AND ANALOGIES

Many historians have cast the failed second Ottoman siege of Vienna (1682–83) as a paradigmatic global power shift predicated on European technological superiority, ensuring Europe’s command of the world stage from the eighteenth century onward. Yet the history of the railway, poised somewhere between the histories of the Industrial Revolution and of Western imperialism, provides historiographic angles from which to gauge and recalibrate this East/West and progress/decline supranarrative. The German empire’s relationship with its Ottoman neighbors was, in fact, characterized much more by an ambiguity and dynamism than it was by antagonism.

A key moment in the union of German and Ottoman interests was Mahmud II’s invitation of a Prussian delegation, headed by Helmuth von Moltke, to Istanbul in 1835 to “Prussianize” the Turkish military.1 Prussian military advisors acquired the Turkish language, while Turkish soldiers acquired Prussian guns, cannons, and other military technology. Despite Ottoman success in the Crimean War (1853–56), military modernization could not keep pace with Ottoman territorial and economic erosion. While a staunch military alliance had been forged, the Ottoman

empire which acquired the popular pseudonym “the sick man of Europe” in international circles seemed to have been diminished to the point of no return.2

The Ottoman Tanzimat reforms further proved the point that a modern military did not constitute a modern empire. Mahmud II’s Tanzimât Fermânı, an imperial statute issued on November 3, 1830, outlined the holistic development of a modern state with qualities mirroring many of those revered in post-Enlightenment Europe.3

As Europe and the Ottoman empire grew closer through both transportation and communications, with the principles of modernization undergirding them, the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman central government) needed to pacify ethnic and religious minorities who might use modern technology such as telegrams and publishing to rally irredentist sentiment. In this light, it is not possible to understand Ottoman “modernization” as only an enlightened, European-inspired project; one must also see it as necessary for protecting the empire from European spheres of inuence by becoming “Western despite the West.”4

The German economist Friedrich List’s support for the expansion of European railway networks provided a paradigm of rail as a totally modern project commensurate with

Tanzimat ideas. In his 1841 publication Das nationale System der politische Ökonomie, List states six ways in which the rail binds nations and cultivates progress:

1. As a means of national defense . . .

2. As a means to the improvement of the culture of the nation . . .

3. As a security against dearth and famine . . .

4. As a promoter of health and hygiene . . .

5. As a promoter of social intercourse . . .

6. As a promoter of the spirit of the nation.5

List’s design for the First Great German Railway Network of 1833 bears an unapologetic, pan-German tenor, with the railway as its nervous system, connecting Prussia with the patchwork of Germanic states to its south and west (g. 1.1). The lines follow the locations of important cities and the anticipation of important trade routes. The nationalist “organic” ambition of the network is as geopolitically polemical in its pan-Germanism as it is in its delineation of denite borders separating it from its immediate non-German neighbors.

Geopolitical and technological strategies like List’s were not lost on the Porte, and such strategies were feasible. But Sultan Abdülmecid I, and Sultan Abdülaziz after him, had to contend with a state that lacked the capital and technical expertise to execute a railway network on its own. In the beginning, the experts were mostly British, particularly outside of inner Anatolia and Rumelia. Abbas I, vali of Egypt and Sudan, was the rst to establish a railway in the empire, contracting the English civil engineer Robert Stephenson.6 The rst part of the line, which spanned from Alexandria to Kafr el-Zayat along the Rosetta branch of the Nile, opened for operation in 1854 and was followed two years later by the completion of the line to Cairo; in 1858, Stephenson extended the line to Suez, making it the rst means of modern transport to connect the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean.

With the Crimean War over in 1856 and the Ottoman establishment of the Darülfünun (House of Science) in 1863, railway development emerged as a goal of scientic progress. In Rumelia, British engineers surveyed the sixty-six-kilometer route between Constanţa (Köstence) and Cernavoda (Boğazköy) and formed the Black Sea Railway and Free Port of Küstendijie Company.7 In Anatolia, the rst track connected Izmir and Aydın in 1866, with the goal of tapping the resources of the rich Aydınplain.

Amid the signicant developments in the eyalets (administrative provinces) of Egypt, Silistra, and Aydın, Francis Rawdon Chesney became the most important foreign gure in the conceptualization of a pan-regional rail network. In 1856, Chesney a British general, explorer, and canal builder conducted a momentous survey of the Euphrates. The following year, he published the Report on the Euphrates Valley Railway, a concise seven-page study analyzing the construction of a national railway under four categories: 1) the advantages that would accrue to England, 2) the existing commerce and its extension, 3) the diculties expected from the Arabs, and 4) the means of laying down the proposed railway.8 Charting the approximately 1,600-kilometer overland route from the Mediterranean port of Iskenderun (Alexandretta) to the Persian Gulf port of Basra, the study is a template for the knowledge European powers considered foundational for building a railway abroad. It expands upon the commercial, technological, and nationalistic aims articulated by List, with another category of cultural concerns relating to challenges posed by the Arabs as a people, their culture supposedly predisposed to be skeptical of modernization. Chesney dispelled that hypothesis, though, noting that “trade has always existed in these countries” and “it is obvious that if they were to endeavour to stop trade altogether . . . they would do themselves an irreparable injury, and they are perfectly alive to their own interests on this matter.”9 He concluded: “I think, if judiciously managed by those who know something of their peculiarities, we have nothing to fear from the Arabs.”10

The Arab gured ambiguously in the railway scheme: loath to modernize but mutable enough to be convinced of modernity’s values. More important to Chesney, however, was how a sultan, unambiguously centralizing his power, could dominate his territories and pashas and facilitate a smooth and secure construction process: “Bearing in mind that the Sultan’s power is unquestioned at Mosul, at Baghdad, at Basra, and at other places, we have only to fear the predatory movements of the Nomad tribes who intervene.”11

It is not clear why the Porte did not adopt Chesney’s project, but infrastructural upgrades appear to have been thought to be more important to the Rumelian and Western Anatolian provinces. Some have viewed this as the result of the Ottoman desire to rally an image of modernization on its European frontiers.12 Others have considered it in the wider context of protectionist desires to curb the

fanning of Balkan nationalisms by St. Petersburg.13 The emphasis on the European frontiers seemed to work toward Ottoman aims, as they were welcomed into the socalled Concert of Europe.14 In exchange for the purported benets associated with the increased diplomatic connections, the Porte promised to accelerate Tanzimat reforms even further, particularly as they related to the treatment of the Christians within the empire.

The accession of Abdülaziz to the throne in June 1861 marked the acceleration of modernizing reforms, due in no small part to the sultan’s love of Western material progress. In September 1861, just weeks after the accession of Abdülaziz, the British secured the 224-kilometer Ruse–Varna concession and advanced their presence on the Black Sea.15 The line, completed in 1866, was the rst to link the Ottoman empire directly to another political unit: the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (subsequently known as the Kingdom of Romania). In turn, this linked the Austro-Hungarian rail network with the rest of Europe via Bucharest and onward through Transylvania.

The benets of connectivity were not unalloyed: Abdülaziz came to understand the particular threats posed by such a unilateral relationship. The British navy already played a disproportionately large role in the naval aairs of the Mediterranean, Black, and Red seas as well as the Persian Gulf. The British extended their marine power to key economic ports on all four maritime borders, mounting the appearance of a colonial encroachment.16 Drawing on the Ottoman empire’s role as a part of geopolitical Europe, Abdülaziz and his advisors began a concerted eort in the 1860s to diversify foreign speculations, investments, and expertise in rail construction among a broader range of powers, including Belgian, French, Swiss, Austrian, Ottoman, and, most notably, German parties.

The American-educated German railway engineer Charles Franz Zimpel had his gaze on the Holy Land.17 Although Zimpel honed his railway construction skills while studying in the United States, his heart remained squarely with the project of pan-Germanism promoted by List. An 1865 treatise by Zimpel makes the unusual case that railway development in the Levant would create an ecumenical symbiosis between Ottoman technoeconomic modernization and the region’s signicance for the major monotheistic religions. The development of Jerusalem as a quasi-utopian Weltstadt for Christians, Jews, and Muslims was an ambition best served by a modern

maritime-railway connection at Eilat or Aqaba and a major land terminus at Damascus.18

To describe the evolution of the railways as a series of discrete events initiated by foreigners would be to betray the realities of intense Ottoman initiatives. In 1868, the Porte instigated the bidding for a conglomeration of lines in the Rumelian provinces, known in international material as the Chemins de fer Orientaux and in national material as the İstanbul–Viyana Demiryolu (the Istanbul–Vienna Railway). Unlike the British-operated railways of the empire, the ambitious scheme in Rumelia stood to benet political needs more than it did economic ones. The support, nancing, and technical expertise for such a large project in as diverse and volatile a geopolitical fold as the Balkans represented an undertaking ideally suited to a multinational entity. Ocials organized a conglomeration of French, Belgian, Swiss, and Austrian investors, each with a 25 percent stake in concessions for all ve of its sections.19 In less than a year, the nancial structure of the project grew shaky, and Abdülaziz transferred the concession to the wealthy Bavarian-born nancier and philanthropist Maurice de Hirsch. Hirsch established the Imperial Turkish Railway Company in Paris, where he lived, and he hired Wilhelm von Pressel, an engineer from Stuttgart.20 “Türkenhirsch,” as the German press aectionately called him, had developed an extracurricular interest in railway construction through the inuential writings of the Saint-Simonians in the visionary 1832 publication Système de la Méditerranée, which described a railway connecting the English Channel to the Persian Gulf.21

With sustainable nancial arrangements, completed surveys, land acquisitions, and a workforce in place, subsequent construction on the Rumelian lines began in 1870. The same year, Sultan Abdülaziz turned his attention to the Anatolian hinterland and the empire’s connection to all points east by way of Baghdad.22 His plan entailed an autonomously Ottoman-operated railway that would grow eastward as resources became available. The immediate goal was to connect the densely populated and newly industrial areas of the northern Marmara littoral with a standard gauge railway ending at Kadıköy, a suburb of Istanbul on the Asian side of the Bosphorus.23

While foreign dominance through railways became a reality by the end of the nineteenth century as in Russia, Japan, and Latin America this line would also remain the most geostrategic and ostensibly autonomous vision of the Ottoman empire’s infrastructure for the next fty

Friedrich List’s design for the First Great German Railway Network, 1833.

From Robert Krause, Friedrich List und die erste große Eisenbahn Deutschlands: Ein Beitrag zur Eisenbahngeschichte (Leipzig: E. Strauch, 1887). University of Rochester, River Campus Libraries.

FIG. 1.1

years. The grand vizier and executor of the railways, Midhat Pasha, held a faith in infrastructure so liberal that it could irritate the sultan himself.24 Midhat had maintained an interest in Chesney’s proposal and ultimately announced a renewed intention for the line in 1871.25 Midhat extended Pressel’s service to the Porte by commissioning him with a detailed study of the span of the empire extending from the Gulf of Alexandretta to the PersianGulf.26

The Porte always knew that it wanted an overland route to Baghdad, and the beginnings of this are manifest in the Haydarpaşa–Izmit line. Yet Abdülaziz and Midhat Pasha remained conicted about the extent to which they wished to involve the British in the project. Their choice of partner ultimately swayed toward the newly unied German empire. For his part, First Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, famous for his Realpolitik, made the no-nonsense observation that a tighter union with the bankrupt Ottoman empire might be practical. “Turkey could never become dangerous for us,” he noted in 1876, “but her enemies could possibly become our enemies.”27

Germany’s eventual dominance in the construction of the Ottoman rail network is commonly considered a major factor that led to World War I, antagonizing as it did Germany’s relationship with Britain and, to a lesser degree, France. However, in an unpublished letter written to Bismarck four days after Abdülaziz’s deposition on May 30, 1876, the British consulate in Berlin actually encouraged Germany to become involved, perhaps even promoting colonization. The letter makes the following case: “Germany has no such misfortune to rectify the economic plight of the Ottoman empire; but this prospect it seems to my humble prognosis would prove immensely to her advantage. Germany would send the most and best colonists, the railway construction with the Austrian frontier is complete, and the colonies would thus be in rail communication with their mother country.”28 This is precisely the course Germany would take.

GERMAN INFILTRATION

Following the ninety-three-day reign of his brother Murad V, Abdülhamid II became sultan and caliph and would remain so for thirty-two years, until his deposition at the hands of the Young Turks.29 No gure played a more sustained and impactful role in the development of the Ottoman rail network. Abdülhamid entered his reign with an empire already at war to suppress the nationalist

uprisings in Serbia and Montenegro, and these would escalate into a full-blown war with Russia. The RussoTurkish War ended less than a year later with the Treaty of San Stefano, which maimed the empire’s—and Abdülhamid’s—sense of sovereignty and physical safety. The principality of Bulgaria was, with additional provisions from the Treaty of Berlin of 1878, reestablished as a sovereign state; Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro gained independence; and Cyprus was leased to Britain. The inroads made in rail development in the southern Balkans proved to be too little, too late.

With the Ottoman state wounded and bankrupt, and with so much of its railway infrastructure now ceded, signicant railway development remained at a virtual standstill between 1875 and 1888, the year Wilhelm II became emperor. Rather than focusing on high-prole projects and reforms, Abdülhamid concentrated his eorts during his rst full decade on his role as the sole adjudicator of Ottoman aairs, making pragmatic moves to shore up imperial security and reassure the world of Ottoman competency. In 1880, the sultan, who was famously paranoid of attacks on his life, relocated his ocial residence from Dolmabahçe Palace to a new palace at the top of a hill on the grounds of an imperial estate at Yıldız.30 Amidst a parade of defeating events, Abdülhamid appealed to Wilhelm I in 1880 for guidance in reordering the military. Over the course of twelve years, German generals managed to shape a generation of “fumbling” Turkish ghters into modern military men, while simultaneously preventing the modernization from meaning a break of allegiance to the sultan.31

While Abdülhamid secured his internal power, Wilhelm I and Bismarck began to reverse their policies of isolationism in extra-European aairs and entered the colonial stage. By 1885, three major colonial conglomerations had been established: German East Africa (Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Ruanda-Urundi, Wituland, and the Kionga Triangle), German Southwest Africa (Namibia and a part of Botswana), and German West Africa (Cameroon and Togoland). Colonists simultaneously arrived in archipelagoes across the Pacic.32

Meanwhile, because of the Russo-Turkish War and the transition of power at the Porte in 1876, Pressel and Hirsch’s proposal for an Anatolian railway remained on the shelf. Pressel attempted to revive interest in the project by appealing to Abdülhamid in 1883, proposing a multinational nancial structure for an inner Anatolian

railway to Baghdad. Abdülhamid rejected the proposal twice, fearing that the ambiguous nature of the nancial structure would too broadly diuse the economic inuence of European powers on the empire.33 European nanciers were also skeptical whether the Ottomans would be able to sustain the construction of such a signicant railway, a concern Pressel sought to mollify when he wrote that “the Anatolian is no less hard-working than the Italian.”34

When the sultan rejected Pressel’s second multinational nancial structure in 1887, Pressel turned to the banker Alfred von Kaulla.35 Kaulla returned to Germany and pitched the project to the banker Georg von Siemens in March of 1888.36 Siemens was personally enthusiastic, but had reservations that stockholders would not be interested in the project because elite and conservative German circles still advocated isolationism. Writing to Kaulla a few weeks later, the Ottoman ambassador to Berlin indicated that an imperial irade had, in principle, sanctioned a Kaulla-Siemens–backed corporation, and the two would be invited to Istanbul when all parties were ready to begin negotiations.37 Siemens, unlike Kaulla, did not think highly of Pressel, who struck him as a naïve and emotional Turcophile.38 Siemens epitomized the liberal capitalist ideology of the Deutsche Freisinnige Partei (dfp) and rejected Pressel’s benevolent contention that the railway in Anatolia was for the singular benet of the Ottoman people. Rather, he emphasized to Kaulla that any support he might oer would be contingent on the rail being an enterprise that “employed German workers, used German materials, and beneted German investors.”39

Distancing themselves ever further from Pressel, Kaulla and Siemens appealed to the German Foreign Oce for support just a few weeks after Wilhelm II’s accession in June 1888, but they received a resolute rejection from Bismarck.40 Undeterred, Siemens signed up for the project several weeks later and indicated to the Foreign Oce that he, Kaulla, and a new entity to be known as the Chemin de Fer d’Anatolie would apply for the concession that the Porte had all but guaranteed them.41 Bismarck, comforted by the knowledge that a name like Siemens would formally back the endeavor, pivoted his position in favor of the project, and an application for the concession was submitted to the Porte.42 A month later, the concession was signed, and in March 1889 the Chemin de Fer Ottoman d’Anatolie established its headquarters in Istanbul.

All involved parties understood that the railway would need to connect to Istanbul but were uncertain how, given the challenges posed by the Taurus and Amanus mountain ranges dividing the empire’s northern Turkish and southern Arab provinces. Pressel did not regard the town of Eskişehir (ca. 20,000 residents in 1890) as a key juncture of the 486-kilometer railway as it stretched onward from Istanbul and Izmit, and he did not recommend out-of-theway Ankara (Angora) as a terminus. In fact, Abdülhamid conceived this route and the Anatolian Railways syndicate surveyed it; they arrived at the argument that the eort to penetrate the mountain ranges of southern Anatolia would at once bring the protable trade of grain, wool, and carpets closer to the metropolitan fold, while also creating a stronger link between the empire’s Turkish core and Arab fringes.

Abdülhamid also reenergized railway development in the Balkan powder keg, issuing concessions for a 219-kilometer line connecting Thessaloniki and Monastir to a German syndicate in 1890, and a 508-kilometer line connecting Dedeağac and Thessaloniki to a French syndicate in 1892. The successful realization of the Jaa–Jerusalem line farther south resulted from an intense three-year lobby of the Porte by entrepreneurs and engineers fromJerusalem.43

Engineers broke ground on the line connecting Jaa to Jerusalem in March 1890. A skilled labor pool of engineers came from Switzerland, Poland, Italy, and AustriaHungary, while workers from Sudan, Algeria, and Palestinian and Egyptian Arab populations provided unskilled labor.44 On the Izmit–Ankara line, German engineers supervised the unskilled labor of local Turks, while Armenians, Italians, and Greeks were hired for semiskilled labor such as stonemasonry and woodworking.45 With tens of thousands of various nationals working on the rails by the fall of 1889, there was no better time to host Kaiser Wilhelm and Empress Auguste Viktoria for a diplomaticvisit.

As the kaiser’s royal yacht sailed through the Bosphorus, a welcome involving 101 rounds of ammunition and a booming rendition of the German imperial anthem echoed across the waterway. The Turkish press downplayed the strategic nature of the visit, preferring to depict it as a touristic experience: “The principal feature in the moral aspects of the Emperor William’s visit is its distinctly pleasurable character. His Majesty comes to satisfy a perfectly intelligible desire to see this picturesque city,

and to experience the charm of its beauty, of its Oriental character, and all of the historical associations which attach to it.”46 The four-day schedule was, in actuality, a serious political itinerary covering everything from military aairs and German economic growth in Istanbul to Zionist and Christian settlement interests.

With a healthy dose of skepticism, some reacted to the sultan’s desire to be popular with the Hohenzollern: “The people, and the government [of Turkey] have to strive for an Islamic culture-state that no longer sees its reason for existence as new conquests or in the obstinate holdings of older territorial gains, but rather in the prosperity of the earth where the Ottomans have the undisputed predominance and right of possession.”47

The natural prosperity of the earth of even a shrunken Ottoman empire was beyond question, and a number of auspicious events in the following years supported the notion of a land resuscitating itself. Expressing this in the terms of Realpolitik, German newspapers described the immense fecundity of Ottoman Palestine, in particular,

and instructed their readers on the complicated steps of land acquisition in the Ottoman empire, a highly regulated process governed by the Ottoman land code and usufruct.48 To this end, interested parties established the Deutsche Palästina- und Orient-Gesellschaft GmbH in 1896 and the Deutsche Palästina Bank in 1897.49

Yet another concession for a railway connection from Haifa to inner Palestine was granted in 1891, this time to a British-Lebanese partnership.50 In 1892, the Jaa–Jerusalem and Izmit–Eskişehir lines were both completed. The progressive journal Servet-i Fünun, established in 1891, took particular interest in the modernizing landscape of the railways, celebrating the inauguration of the Izmit–Eskişehir line in several sequential accounts (g. 1.2).

Shortly thereafter, the Porte extended another concession to the Germans for an additional 445-kilometer line to the city of Konya via Afyonkarahisar. Amidst widespread devastation wrought by a massive earthquake on the fault line running through northwest Anatolia in July 1894, there was an armation of faith in German expertise, as the railway and its bridges, tunnels, and stations survived unscathed.51

Progress along the railways’ tracks gave way to larger ambitions. The German team, which included two Frankfurt powerhouses, Deutsche Bank and the construction rm Philipp Holzmann GmbH, received the concession for the construction of a railway in German East Africa; Holzmann’s archives reveal the many ways that the lines in Africa and in Turkey were conceived as parallel projects.52 In the spring of 1897, the railways mobilized the Ottoman military for the rst time, bringing troops to Izmir and on to Crete to suppress a Greek rebellion.53 Yet the intellectual and secular elites of Ottoman society began to view the sultan’s xation with rail as an emblem of his increasingly autocratic and oppressive regime. Damad Ferid Pasha, a progressive Serbian-Ottoman statesman, wrote a captious open letter to Abdülhamid in January 1900, after being falsely accused of treasonous plots against the sultan’s life. The letter exclaims: “You indulge in unreasonable actions and wasteful expenditure, such as the creations of grades and decorations unseen in any other state. . . . Our country is rich, capable of prosperity and of supporting in comfort twenty times its present population. But, alas! a gang of robbers has seized it and has barred the road to wealth and treasure.”54

The railway, however, posed a unique quandary for the growing Young Turk movement, of which Damad Ferid

FIG. 1.2 Announcement of the completion of the Eskişehir–Ankara line on the cover of Servet-i Fünun (1890.) Milli Kütüphane Başkanlığı, Ankara.

Pasha was a part. Many did not consider it a “wasteful” expenditure in the same way that “gratications” to local governors, lavish festivals, and ostentatious monuments were. Indeed, the vast majority of the Turkish public saw the railway as a means to opening up prosperity. Still, the colonial benets it proered German capitalists (the “bandits”) were also worrisome and accelerated a factious political climate based on ideology, not nationality one that allied the kaiser with the sultan as much as it did the urban intellectual with the overworked and underpaid railwaylaborer.

GERMAN EXPANSION AND OTTOMAN AUTONOMY

By the time of the kaiser’s second visit in 1898, the international press was depicting the German-Turkish venture as unambiguously colonial. In an article entitled “German Anatolia: Conquest by Railway,” the Pall Mall Gazette characterized the meeting as an inevitable and “practical” geopoliticalmarriage:

If only a beginning has been made, it is quite recently that Anatolia has become penetrable, and into the newly opened region the Germans are now the rst to press their way as pioneers of Western commerce. Will these pioneers ultimately become an invasion of colonists? The line of conquest is plain—the railroad, the trader, the settler. Already the railroad is a German strong point. There are now nearly 1,000 miles of railroad in Asia Minor, the easternmost terminus at Ankara fairly in the heart of the country. The railroad represents direct German inuence. For the Mahomedan Turk, a railway is a practically unmanageable invention. Initial diculties attend the working of a railroad by ocials who must attend to their devotions when the muezzin announces the hour of prayer from a minaret; but this is of little importance as the sti formalities of El Islam are falling considerably into abeyance in many provinces of the Empire. It is not, however, so easy to get over the fact that the ordinary Turk is a rough bungling fellow whose heart is better than his head, by no means to be trusted with the management of a locomotive, or able to understand either punctuality or the necessity of giving his attention to routine duties.55

German-Turkish railway activity ourished in the wake of the kaiser’s visit, which both the Porte and Berlin saw as an immense success. In January 1899, German

consular records began to tout the railway as a formulator of Turkish “moral connectivity,” stressing the consuls’ personal belief that the project was not colonial.56

But the crown jewel of the strengthened alliance was the concession for a new railway line to extend from Konya to Baghdad. Of course, a terminus in Baghdad was the main ambition for the Anatolian Railways from the outset, but now the fruit of more than three decades of speculation would emerge from the realm of fantasy into the realm of cold hard steel.57 Abdülhamid himself noted: “The Baghdad railroad will revive the old trade route between Europe and India. If this line is extended so that communication is established with Syria and Beirut, and Alexandria and Haifa, a new trade route will emerge. This route not only will bring great economic benet to our empire but also will be very important from the point of view of the military, as it will consolidate our power.”58

As momentous as the introduction of the kara vapur (black ferry) had been to European Turkey, Palestine, and Anatolia, the penetration of the Cilician plain, Syria, and Mesopotamia gripped both the Turkish and the German psyche as something more: a teleological necessity. This concession united the topographical and geographical knowledge produced by centuries of European explorers and the ambitions of a twentieth-century sultan. Here the Atlantic would meet the Indian Ocean, and the cradle of civilization would meet the modern age. For their part, the Ottoman signatories stipulated an annex to the agreement in which the German parties promised that no part of the line would be “colonized.”59

Within the Ottoman empire, however, and certainly within the Islamic world, the excitement of a train reaching Baghdad was soon eclipsed by the excitement of a train reaching an even more symbolic destination: Mecca. Invigorated by the successes of the foreign-led railways, Abdülhamid gave his blessing in 1900 to the plans for the so-called Hejaz Railway, which would facilitate a connection to the holy site in distant Arabia. For all of his perceived shortcomings, Abdülhamid took his role as caliph seriously when it came to the Hejaz Railway, wasting little time to place the best technological resources at the empire’s disposal for the cause of a modernized method of pilgrimage for the world’s Muslims. The sultan’s publicly stated aims for the project, which would weave “the motherland from four corners with nets of iron,” were

threefold: 1) to facilitate the pilgrimage, 2) to maintain the sovereignty of the Ottoman state, and 3) to foster panIslamic unity and education.60

In May 1900, Abdülhamid issued an imperial irade asking the empire’s Muslims for contributions to the railway, advertising the request through dailies such as Malûmat and Sabah.61 By the summer of 1903, with money growing ever tighter, the sultan issued an amplied request with “suggested donations” from every Muslim in the empire.62 Successful overtures were also made to international Muslims, as well as the Christians, Jews, and Druze peoples who stood to benet economically from the railway’s construction in Syria and Transjordan.63 The Hejaz administration organized labor in a binary fashion. A central oce in Istanbul managed donations, the purchase of supplies from abroad, and general scal management, while a central oce in Damascus managed everything else, including design, engineering, construction, and labormanagement.64

The results of the initial work executed by Ottoman engineers were, by all accounts, disastrous. Feeling intense pressure from the Porte to make things happen eciently, the Hejaz Railway administration reluctantly sought the help of a foreigner who would report to authorities in Istanbul but manage all of the operations from Damascus. The Porte chose Heinrich August Meißner, who had established strong credentials through his accomplished service on the Izmit–Ankara (1888–92), Thessaloniki–Monastir (1892–94), and French-managed Thessaloniki–Dedeağac (1894–96) lines.65 Meißner who promptly red the vast majority of engineers in place championed the project’s pious integrity, noting that the Hejaz Railway was “the most honestly managed fund in the country.”66 Soon thereafter, the Damascus oce enlisted the American-German engineer and architect Gottlieb Schumacher, a colonial leader in Haifa, to oversee the branch from Haifa to Daraa and onward to Damascus. Schumacher disagreed with Meißner about the outlook of the project and confessed he never believed the line would reach Mecca. He maintained that its construction was actually geostrategic, not pious.67 The Azeri journal Molla Nәsrәddin, reecting these sentiments, regularly commented on the geopolitical jockeying of the railway project and poked fun at its numerous travails (gs. 1.3, 1.4).68

In Berlin, meanwhile, Siemens, in ill health, was preparing to pass German leadership of the Baghdad Railway on to his successor at Deutsche Bank. Siemens met with a

Molla Nәsrәddin/Молла Насреддин (Azerbaijan) 1, no. 12 (1907), cover with a satirical view of railway construction. The Ottoman government busily feeds Germany (left) and Austria (right) at a table while others (left to right: Italy, Bulgaria, Serbia) must wait. The train set refers to the Baghdad Railway. The caption reads “Osmanlı: Hәlә sәbr edin, sizә dә verәcayem” (Turks: Be patient, we’ll serve you too). University of Rochester, River Campus Libraries.

group of men, several of whom had recently returned from a study expedition (known as the Stemrich Expedition) from Konya to Basra, to determine the anticipated costs for the railway’s construction. The sum Siemens anticipated was considerable approximately 700,000 Turkish pounds per year of operation.69 The agreement between the railway company and the Porte was, in principle, based on a system of kilometric guarantees: 11,000 francs per kilometer in full operation, and 4,500 francs per kilometer under construction.70 These were to be delivered from “excess” revenues raised by the normal taxes of the vilayets, which meant that the citizens who most benetted from the railway were the ones paying for it.

Just months before his death, Siemens traveled across Europe to raise the necessary capital, and this eventually produced an eective if convoluted nancial structure

FIG. 1.3

FIG. 1.4 Unknown artist, Molla Nәsrәddin/Молла Насреддин (Azerbaijan) 3, no. 2 (1909), cover with a satirical view of railway construction. The gure on the left represents “old traditions,” while the gure on the right represents “old sciences.” The train is labeled as “progress,” while “regression” is written on the back of the cleric’s head. The caption reads “Qoymarıq qabağa gedәәsәәn” (We won’t let you move forward). University of Rochester, River Campus Libraries.

consisting of an initial base of 15 million francs divided among thirty thousand shares at 500 francs each.71 The Ottoman government and the Anatolian Railways Company each purchased 10 percent of the shares outright. Siemens further brought together a nancial conglomerate of German, French, Austrian, Swiss, Italian, and Ottoman banks that acquired the remaining 80 percent.72 In March 1903, the syndicate and the Porte signed the concession for the Baghdad Railway (g. 1.5).

Fear of an incursion in or around the British protectorate of Kuwait also frightened its newly semi-independent sheikhs, who sought British help to strengthen port operations. The British swiftly agreed, building a number of wharves and other facilities for the Kuwaitis in 1906 and 1907.73 However, to most high-level ocials in Britain, the railway was insignicant apart from its role in the

Persian Gulf. A British writer and specialist on Ottoman debt reported: “There is no doubt compensation from the increase of land area under cultivation, which has produced a consequent increase of the tithe revenue and the railways have naturally produced a certain amount of prosperity; but as long as commerce is obstructed and industrial liberty is interfered with by puerile police measures, and as long as the construction of roads, bridges, tramways, irrigation and harbor works is neglected, the railways cannot pay their way for a long time to come.”74

The British consul to Germany ventured a comprehensive psychopolitical picture of the railway and its events in March 1907, noting how the German press downplayed the “colonization” eort, strategically diminishing the railway’s geopolitical signicance so as not to raise international suspicion.75 However, Wilhelm’s characteristic nicety, “my friend the Sultan,” belied his ambiguous motives. “There is no doubt,” the British consul wrote, “that in the eyes of many Germans . . . Asia Minor is considered more thoroughly German than some of the German colonies.”76 The colonization was promulgated by what another traveler identied as a facilitative role played by religious Turks, from the bureaucracy down to the peasants, and perhaps more generally by Islam as a religion. After a secretive trip to many of the rail sites in 1908, this same traveler determined that the problem was “the indolence of the peasant, who has no ambition beyond the immediate needs of his belly. To work hard today that he may have some money for to-morrow is unnecessary on the part of an individual who believes that his future lies entirely in the hands of God.”77 What this

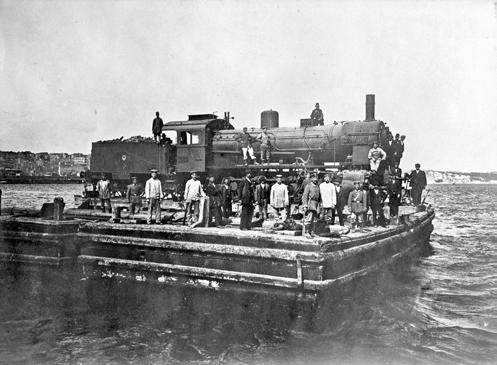

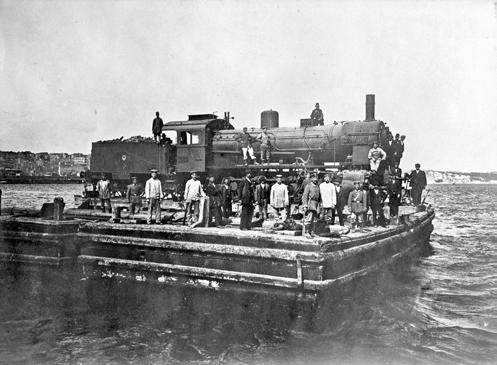

FIG. 1.5 View of a German locomotive being transported across the Bosphorus, 1904. Bayerisches Kriegsarchiv, Munich.

traveler did not consider, however, was the number of Turks who did not believe that their fate lay in God’s hands or the sultan’s, a group who would mobilize a radical shift in the empire’s state of aairs as well as that of the railways in the coming years.

RAILWAYS AND REVOLUTION

Systematically aggrieved by the sultan’s cherry-picking of modern democratic principles, a formalized union of Ottoman military ocers known as the Committee for Union and Progress (cup) realized the sultan’s worst nightmare: an organized coup against him in 1908.78 The future of German interests and activities, which had been so deeply associated with Abdülhamid, remained to be seen.

Construction of the Hejaz Railway and its branches had proceeded extraordinarily well, and in September 1908, just ve weeks after the reinstallation of the constitution, the line opened to Medina with great fanfare. The political situation, however, gave credence to the view that a railway should not penetrate Mecca itself, eliciting the ambiguous relationship that railways and religion should have. The nal 338 kilometers of the pilgrimage to Mecca would continue, as it had for centuries, by land.79 The Hejaz Railway was ready for operation to Medina at the time of the January 1909 pilgrimage, and although this came with a great deal of fanfare, records also indicate that the authorities had begun to fear the German speculation of coal in the area and what that might mean for Ottoman sovereignty in the region around the Hejaz.80

In contrast, construction in the Anatolian hinterland had made no kilometric progress since October 1904. This was partly because of nancial struggles and partly because of the challenges of penetrating the Taurus and Amanus ranges, which required an unprecedented eort in boring tunnels, building bridges, and negotiating labor and supplies across dicult terrain.

A workers’ strike in September of 1908 exemplied the sense of personal empowerment rippling across the empire in the wake of the so-called Second Constitutional Era. Approximately seven hundred members of the Union des Employés du Chemin de Fer d’Anatolie had met with their lawyer and cup leaders at Haydarpaşa station in August and mounted a list of concerns, stressing that an imminent strike would, in fact, not be an action tied to the revolutionary events of the day.81 The workers’ statement included the following armations: “We strongly protest against the false idea that we seek to spread revolution. Be

sure dear comrades, our word would be more revolutionarily pronounced if we were. If there are judges in Berlin there also must be in Scutari. Nobody has the right to slander us while the law protects you.”82

The strikers emphasized Islam as well as Ottomanism to assure the railway administrators that they should not fear a political revolution, despite the political undercurrents of the day. The workers invoked the Qur’an to underscore their unambiguous openness to foreigners, but also to stipulate their right to take issue with particular administrators or other parties if they deemed them abusive or otherwise unt: “It [Deutsche Bank] has also wanted to intimidate you by claiming that your association is illegal because among you there are a few of foreign nationality. It makes me laugh, for we Ottomans have never distinguished between our compatriots and friends overseas. The Qur’an and Muslim laws require us to consider all men without distinction of race, nationality and religion as our brothers and to treat them as God teaches. . . . We do not say we do not want any foreign collaborators, but we reserve the right to say at any time that we do not want this or that person, because he simply does not belong.”83

The workers’ dissatisfaction caught the Baghdad Railway administrators completely o guard, and, interpreting the problem as scal rather than cultural, they sought Deutsche Bank’s help in nding a solution. Administrators oered slight pay raises, but Deutsche Bank did not oer suggestions about the cultural issues, leaving that up to the administrators, who, as a group primarily consisting of engineers and architects, were largely untrained in the art of multicultural diplomacy.

By the early twentieth century, the ascendancy of the German steel industry had made Germany the most powerful economy in Europe, surpassing Britain sometime around 1902.84 Personal prosperity skyrocketed, and it became increasingly dicult to attract skilled people to a conict-ridden Ottoman empire to build railways. Expansive marketing eorts to do so began in 1909, most prominently through the circulation of several thousand pamphlets to young engineering graduates. The pamphlets laid bare the atavistic aspects of railway construction for Germans, attempting to tap into a heady mix of populist, Orientalist, and colonial elements and convince colonist workers to come to Mesopotamia. A sampling of the lofty rhetoric includes: “Realize your interests in the Orient! She is worth millions and is in danger of being lost. Help strengthen the Germans in the East and

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

The officials became so alarmed that just before the death of Philip II. he was requested to prohibit any further enumeration of the Moriscoes, because it acquainted them with their power and must eventually prove prejudicial to the interests of the monarchy. Besides their menacing increase, which no supervision, however effective, could prevent, they possessed qualities that made them highly obnoxious to their masters. Their frugality and thrift, their shrewdness and enterprise, rendered competition with them impossible. There was no profitable occupation in which they did not excel. In agriculture they had no rivals. They monopolized every industrial employment; all of the most useful trades were under their control. They undersold the Castilian peasantry in their own markets. Even the most opulent, instructed by previous experience, sedulously avoided every exhibition of luxury; but the Moorish artisan had not lost the taste and dexterity of his ancestors, and the splendid products of the loom and the armory still commanded high prices in the metropolitan cities of Europe. It was known that the Moriscoes were wealthy, and popular opinion, as is invariably the case, delighted in exaggerating the value of their possessions. While they sold much, they consumed comparatively little and purchased even less. Although the offence of heresy could no longer be consistently imputed to them, specious considerations of public policy, as well as deference to ineradicable national prejudice, demanded their suppression. Their prosperity, secured at the expense of their neighbors, and a standing reproach to the idleness and incapacity of the latter, was the measure of Spanish decay. In the existing state of the public mind, and under the direction of the statesmen who controlled the actions of the King, a pretext could readily be found for the perpetration of any injustice. The Moriscoes of Valencia, the most numerous, wealthy, and influential body of their race, protected by the nobles, had always shown less alacrity in the observance of the duties of the Church than their brethren, and had thus rendered themselves liable to the suspicion of apostasy It was declared that after a generation of espionage, prayer, and religious instruction they were still secret Mussulmans. This opinion, perhaps in some instances not without foundation, amounted to absolute certainty in the narrow mind of Don Juan de Ribera, Archbishop of Valencia, a