Aurora 7

The Mercury Space Flight of M. Scott Carpenter

Colin Burgess

Bangor, NSW, Australia

SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION

Springer Praxis Books

ISBN 978-3-319-20438-3 ISBN 978-3-319-20439-0 (eBook)

DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20439-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942683

Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

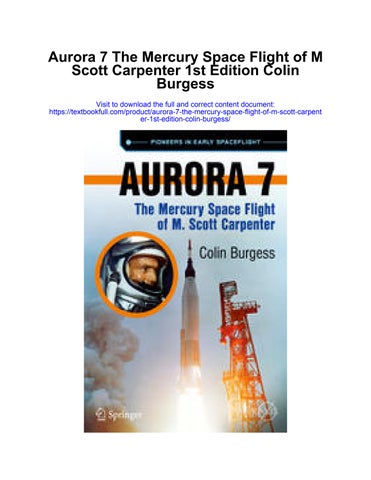

Front cover: Aurora 7 launched with Scott Carpenter aboard, 24 May 1962. (Photos: NASA)

Back cover: Left: MA-7 astronaut Scott Carpenter prepares for his mission. (Photo: NASA). Right: A recent photo of Scott Carpenter at the Kennedy Space Center. (Photo: collectSPACE.com/Robert Pearlman)

Cover design: Jim Wilkie

Project copy editor: David M. Harland

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com)

There is one spectacle grander than the sea, that is the sky; there is one spectacle grander than the sky, that is the interior of the soul.

– Victor Hugo (1802–1885)

This planet is not terra firma. It is a delicate flower and it must be cared for. It’s lonely. It’s small. It’s isolated, and there is no resupply. And we are mistreating it. Clearly, the highest loyalty we should have is not to our own country or our own religion or our hometown or even to ourselves. It should be to, number two, the family of man, and number one, the planet at large. This is our home, and this is all we’ve got.

– Scott Carpenter (1925–2013)

Foreword

In May 1959, a few weeks after NASA had announced the selection of the seven Mercury astronauts, a 23-year-old Air Force nurse began working at the Patrick Air Force Base hospital in Florida. Just six months later, before she’d really had a chance to settle in, the hospital commander, Colonel George Knauf, called her into his office and asked if she would like to consider working as a nurse for NASA’s astronauts at nearby Cape Canaveral. Much to her astonishment, 2nd Lt. Dee O’Hara would find herself at the very heart of perhaps the greatest scientific endeavor ever undertaken, and doing one of the most enviable jobs in the world. She had become the trusted nurse for America’s astronauts.

Although I wasn’t really sure what the job entailed, I accepted. I really didn’t know what to expect or what was ahead of me when I was sent to the Cape. I must also admit that I didn’t really know what an astronaut was, and the only thing I knew about Mercury was that it was a planet, and also the stuff in a thermometer. It turned out that I was to set up the Aeromed Lab, an examination area for the astronauts in a building simply called Hangar S, and be with them as their nurse. I always felt the Mercury program was launched from there because we were all crammed into this one little hangar.

I was 23 years old back when I started work at the Cape, and admittedly not very sophisticated, so my first introduction to the astronauts came as a bit of an unexpected shock. Nobody had been assigned to a flight at that point, it was so early in the program, and this probably would have been January 1960. I happened to go down the hall one day and when I opened the door to the conference room they were all sitting there, with John Glenn seated on the table. I had no idea they were in the room and felt terribly embarrassed and even a little frightened that I had barged in on them. They were, after all, very famous people by then. I stammered an apology and backed out, slamming the door behind me, and fled back red-faced to my office. Then John Glenn, bless his heart, walked up and asked me to come back “and meet the guys,” and said he would introduce me, which he did.

The premise behind me being there was that they wanted someone who would get to know the astronauts so well that she would work out whether they were really sick or not. The astronauts certainly were not going to tell the flight surgeon, Bill Douglas, because

they knew the doctor had the right or capability of grounding them – the last thing these guys wanted. They were really fearful of doctors for this reason. So I made a deal with them: I said I would never betray them unless, in my opinion, what they told me would jeopardize them or the mission. In that case, I would have to report it to Dr. Douglas.

Back then, everything seemed to exist in Hangar S. It was essentially a long string of rooms off a narrow hallway which overlooked the fl oor of the hangar. We had a lab area, an exam room area, my little offi ce, and then there was a large carpeted room where the space suits were kept. The suiting-up couch was in that room, where all of the suit check- outs were carried out. Then you went to the next room which was set up as a kind of a conference room for the astronauts. Past that was a little lounge area which was considered to be crew quarters, and in the next small room were bunk beds. If they were training late, or working in the capsule late, they could at least bunk there and sleep the night in privacy, and not have to drive the nineteen miles to a motel in Cocoa Beach, although they often used that distance to set hair-raising speed records in their powerful cars. Boys will be boys.

Initially, the astronauts were based at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. During the week, they would fly down to the Cape in Florida for their testing, suit fittings, chamber tests, and so on. Then they would go back to Langley for the weekend. When it was launch time they would come down to Cape Canaveral and I would help them with pre-flight physicals, including height, weight, temperature, blood pressure and other tests.

Over the next few years, I served as the astronauts’ nurse, tending to them and their families. I didn’t really get to know their families well until I transferred to Houston, although I had met most of the wives when they’d traveled down to the Cape on rare occasions. Most had very small children at the time, so they stayed pretty close to home.

Once I had set up the Flight Medicine Clinic in Houston, the families would come to the clinic for medical care, in addition to their astronaut husbands. I became very close with the wives and knew them all intimately – they invited me into their homes. I am still in touch with many of them today.

They were wonderful days, but I always had my heart in my mouth whenever one of them was launched into space. You could feel the tension on everyone’s part, because these men were entering the unknown and we didn’t know what the heck was going to happen. It was both exciting and terrifying at the same time. Early on, I don’t think any of us really thought about how historic these days would become. It was a job, and you just did your job.

I used to hear from people all over the world about how exciting they thought my job must be. I must admit I had the most ideal job in the world – I traveled, met movie stars, and got to associate with so many interesting people. I feel very fortunate to have been a part of a unique and exciting time in space history.

We all miss Scott Carpenter so much after he left us at the grand age of eighty-eight. The Scott I knew back in the Mercury days could see the beauty, the poetry or the emotion in so many things. He really was a poet, and a very sensitive, caring man.

Although it’s only a small example of who he was, I won’t forget the day he came into my office and said “Dee, the flint’s gone in my lighter – do you have any flints?” I said I’d try to find one and after he’d gone I searched around and found a couple, which I taped

Scott Carpenter with astronauts’ nurse Dee O’Hara. (Photo: NASA)

Scott Carpenter and Dee O’Hara raise a toast to Mercury astronaut Wally Schirra at his colleague’s funeral in 2007. (Photo: Francis French)

under a piece of Scotch tape on his lamp. When I came in the next morning there was the piece of tape on my lamp, and underneath it was a note, and it said, “A kiss is in here for you.” You see, that was Scott. It’s hard to explain him to people, but that’s a classic example of what he would say, and the gentleness and the sensitivity of the man. I’ve always had a very special spot for him.

I truly feel Scott did a wonderful job on his flight aboard Aurora 7. He got a lot of science done, a lot of the experiments that were thrust on him, and it’s a shame he doesn’t get enough credit for that. Yes, he missed his splashdown mark and scared everybody for a while. But the tragedy was when someone as powerful as Chris Kraft later came out and said, “I won’t work with him again.” That absolutely killed Scott’s career. It was just heartbreaking; it shouldn’t have happened. It was a very sad episode in an otherwise wonderful career, including his later exploits as a Sealab aquanaut. What an amazing person he was.

Over recent years, I caught up with Scott several times at different space events, and it was always a great pleasure to see him and to reminisce about old times and old friends. Scott especially loved talking to the children who came with their parents to the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation events. His eyes would light up as he asked them a number of questions about themselves and school. It was interesting to watch the children open up and talk to him without any shyness or hesitation.

We were all so sad when we heard the news of his passing, but like so many others I will always hold dear the precious memories of a man who gave so much to his nation, and yet retained the soul of a poet.

To paraphrase those unforgettable words to his great friend as John Glenn was about to be launched into orbit, “Godspeed, Scott Carpenter.”

Dee O’Hara Astronauts’ nurse

Author’s prologue

I first met Scott Carpenter in 1993 at the Association of Space Explorers’ Congress in Vienna, Austria. After I’d asked him to sign my copy of his novel The Steel Albatross –which he did quite happily – I happened to mention that I had at home a photo of him riding a horse while stationed in Muchea, Western Australia, for the MA-6 orbital Mercury flight of John Glenn back in 1962. Immediately his face lit up and he smiled as he said, “Ah, yes – Butch.” He remembered that horse well, and we fell into a conversation about the time he had spent in Muchea, and the people he’d met there. Some years later, Scott would recount by telephone the story of riding Butch in the Australian outback for a chapter in the book Into That Silent Sea, which I co-authored with Francis French. Scott and I met again several times over the years at different venues, and it was always a true pleasure to sit and chat with a man who was a boyhood hero of mine. So much so that our older son was named Scott after him – a tribute he gladly repaid by sending me a surprise personal greeting for my son and his bride Melissa which I had the pleasure of reading out on the occasion of their wedding.

Although my enthusiasm for human space flight had kicked into gear during the muchdelayed Mercury flight of John Glenn, the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) flight with Scott flying aboard Aurora 7 was the first space mission I followed right from its inception, even when it was meant to be flown by another astronaut, and with the spacecraft bearing a different name. Some years later, I was able to view Aurora 7 up close when it was on display at the Hong Kong Science Museum in Kowloon, never for one moment imaging that one day I’d not only get to meet Scott but befriend him and his daughter, Kris Stoever.

One truly unforgettable occasion came about on 26 January 2003 while I was visiting my long-time friend and co-author Francis French in California. We were delighted to have been invited to a private reception that afternoon at the Oakmont Country Club in Glendale by the Stoever family to mark the publication of Scott’s autobiography For Spacious Skies, written with his daughter. After they had signed everyone’s copies of their book, there was plenty of time to mingle with all the guests – many of them doyens of the space industry. Eventually it was time for Scott to make a short speech, thanking everyone

Scott Carpenter with the author at the Autographica show in Coventry, England, 2004.

(Photo: Rex Hall)

The author enjoys a fun-filled conversation with Scott Carpenter at Spacefest V in Tucson, Arizona, May 2013. It would prove to be the last time they met. (Photo courtesy of collectSPACE. com/Robert Pearlman)

for attending. Midway through his oration he paused and casually mentioned that he would also like to thank another old friend who had just turned up. I turned around and it was a real pinch-me moment. The late attendee was Gordon Cooper. It would prove to be the first and only time that I had the opportunity to meet and talk with this other legendary Mercury astronaut, who sadly passed away the following year.

The last time I enjoyed a conversation with Scott Carpenter was at Spacefest V in Tucson, Arizona, at the end of May 2013 – in fact, on the 51st anniversary of his Mercury flight – and once again I enjoyed the chance to sit and chat with him as he kindly gave me a few words to use in an earlier book in this Springer series about his Mercury colleague Gus Grissom. Just five months later, I was deeply saddened to learn of Scott’s death on 10 October, at the grand age of eighty-eight.

It was quite evident that Scott Carpenter (he told me he always disliked his given name of Malcolm) was cut from a very different cloth than that of his fellow Mercury astronauts. A dynamic pioneer of modern exploration, a superb athlete and test pilot, he was also a gentle and even poetic man; an experimentalist whose curiosity almost cost him his life on his only space flight and led to a well-documented falling out with certain influential members of the NASA hierarchy.

Nevertheless, his incredibly rich and diverse life certainly touched mine in so many ways, and I will be forever grateful to him and his family for allowing me to briefly touch on his own. Author’s

Acknowledgements

Bless their hearts, one and all, because a project such as this relies heavily on those who not only support the writing of the Mercury series of books, but are also willing and happy to contribute their memories and experiences.

While this particular book, out of necessity, relies heavily on numerous accounts previously written by, about, or recorded by Scott Carpenter – our amazing Dynamic Pioneer –it is the people who worked with him and knew him best that helped characterize this wonderful, adventurous man, who was blessed with the soul of a poet. I was fortunate enough to have met Scott many times over the years, and to have recorded a lengthy telephone interview with him back in 2002 – much of which was also mined for this book. He was certainly a much-loved man. Sadly, however, so many years have gone by since the unforgettable flight of Aurora 7 in May 1962 that we have not only lost Scott Carpenter, but so many people deeply involved in his one and only flight into space. It made me doubly appreciative of those that I manage to locate who willingly dipped into the past for me and offered their accounts of that day in history, or revealed different aspects of the life and accomplishments of a greatly missed Mercury astronaut.

Many sincere thanks therefore go to Matthew Appelbaum (Mayor of Boulder, Colorado); Leigh Bartlow; Mike Blair; Ed Buckbee; Bill Cotter; Kate Doolan; Zachary Epps; Al Hallonquist; Joseph Hiura; Alan Humphries; Russ Kaufmann; Renee Mailhiot (Public Relations Coordinator) and Sarah Rosenbloom (Think Tank Volunteer) at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry; Anne Mills (NASA Glenn Research Center); Bruce Moody; Michael Neufeld (Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum Space History Division); Robert Pearlman (collectSPACE.com); J. L. Pickering (retrospaceimages.com); Eddie Pugh; Alan, Alice and Tom Rochford; Scott Sacknoff (Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly); and Patrick von Keyserling (Boulder Director of Communications).

Special thanks go to a dear and long-time friend who lived through those amazing years as the astronauts’ nurse, Dee O’Hara, for agreeing to write such a wonderful Foreword to this book. Multiple thanks also to yet another friend and colleague of many years, Francis French, who ran his eagle eye over this manuscript – as he has done with so many previous

xix

works of mine – not only checking facts, making suggestions for improvement, and seizing upon typos for me, but also pointing out to an Aussie author where a certain word or phrase that I might have used would have had an American scratching his or her head in puzzlement.

My friendly “deputy” Tracy Kornfeld also read through the text and his input was greatly appreciated. The web site that he created with Scott Carpenter is chock-full of stories and biographical information by and about the man, and I encourage any reader to check out www.scottcarpenter.com.

Finally, I am truly and abundantly grateful to two extraordinary women who were not only close to the late Scott Carpenter, but offered to assist me in paying tribute to him through this book. I therefore humbly acknowledge the kind help and gracious encouragement of the Dynamic Pioneer’s widow and daughter – Patty Carpenter and Kris Stoever. And of course, I must thank the good folks who turned my manuscript into a book. Clive Horwood of Praxis Publishing in the United Kingdom; my superb copyeditor, fellow author and good mate David M. Harland; and Jim Wilkie, who produced the glorious cover art for this and all my Springer books. At Springer Books, New York, my effusive and ongoing thanks to the hard-working Maury Solomon, Senior Editor, Physics and Astronomy, and her incredibly helpful Assistant Editor Nora Rawn, who has worked miracles for me in so many ways.

1

A replacement astronaut

1960 was a monumentally busy and incredibly productive year for America’s dynamic new civilian space agency, NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), which had been formally established just two years earlier. But the agency faced an uncertain future. With an election looming later that year, incumbent president Dwight D. Eisenhower had shown little regard for the nation’s space programs, taking the sword to NASA’s budget for the following year. He also wanted to cut the second stage of the Saturn rocket program, consigning the space agency to a future based solely on flights in low Earth orbit, without the necessary support or funding to continue through to actually landing astronauts on the Moon.

Under the Eisenhower administration, NASA faced the bleak prospect of having the civilian space program basically put out to pasture after Project Mercury. Even his potential replacement in the White House, Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon, had very little enthusiasm for a costly civilian space program. Foreshadowing a drastic curtailment of human space activities, President Eisenhower voiced his opinion that, “further tests and experiments will be necessary to establish if there are any valid scientific reasons for extending manned space flight beyond the Mercury program.”1

Despite this grim prognosis, midway through 1960 the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) of the Redstone Arsenal, Huntsville, Alabama, became a part of NASA and was renamed the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center. In August the space agency successfully orbited Echo 1, an inflatable, aluminized balloon communications satellite, while on 19 December, in preparation for the agency’s goal of a manned space flight, the first test flight of a Redstone rocket carrying a Mercury capsule was successfully completed.

In November 1960, America voted in a new president by the narrowest of margins. John Fitzgerald Kennedy became the youngest man ever elected to the office, and the first Catholic to occupy the White House. NASA still faced an uncertain future, knowing that during his campaign Kennedy had been disappointingly non-committal about the nation’s non-military space program. Beyond making vague statements whenever the subject was raised, he was not at all convinced that sending humans to the Moon should form a major element of his forward strategies and policies. He had even stated that developing huge rockets was a colossal waste of taxpayer money.

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 C. Burgess, Aurora 7, Springer Praxis Books, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20439-0_1

1

Before a session of Congress on 25 May 1961, President John F. Kennedy commits the United States to landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. (Photo: NASA)

President Eisenhower with (right) Dr. T. Keith Glennan, NASA’s first Administrator, and Deputy Administrator Dr. Hugh L. Dryden. (Photo: NASA)

First astronaut chosen 3

History records that within half a year of taking office, and leading a nation stunned by the Soviet achievement of launching cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into orbit, President Kennedy committed NASA and the United States to landing astronauts on the Moon’s surface by the end of the decade. Instead of instigating a decline in the nation’s space program, he used it to inspire the nation, and boldly set the country on what was arguably the greatest technological endeavor of all time.

FIRST ASTRONAUT CHOSEN

As 1960 rolled over into a whole new year filled with promise and excitement, albeit an uncertain future, NASA stood ready to decide who would become the nation’s (and hopefully the world’s) first space explorer – the man who would take America into space on a suborbital mission just a few months later.

The Mercury spacecraft for the historic suborbital shot was nearing completion at the McDonnell plant in St. Louis, Missouri, but NASA needed a pilot for the flight, and there were seven superbly qualified men to choose from. All were exemplary test pilots, and they had been undergoing intense space flight training since their selection back in April 1959. From the U.S. Air Force there were Capt. L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., Capt. Virgil I. Grissom and Capt. Donald (“Deke”) Slayton; from the U.S. Navy, Lt. M. Scott Carpenter, Lt. Cmdr. Walter M. Schirra, Jr., and Lt. Cmdr. Alan Shepard, Jr. The seventh man, and sole Marine Corps representative, was Maj. John H. Glenn, Jr.

NASA’s newly selected Mercury astronauts. From Left: Gus Grissom, Alan Shepard, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, Deke Slayton, John Glenn and Gordon Cooper. (Photo: NASA)

The final decision on who would fly first fell to just one person, Dr. Robert Rowe Gilruth, at that time the appointed Director of NASA’s Space Task Group. On 19 January 1961, just one day before the inauguration of the nation’s newly elected president, Gilruth called the seven Mercury astronauts together into his office for an urgent meeting. Without revealing the exact nature of the exercise – although all seven quickly deduced its purpose – he handed each man a slip of paper and asked them to write down, in descending order, which person – obviously excluding themselves – they thought was best qualified to be given the job of making the first American space flight. Once they were done he collected the papers and instructed them to reconvene in the afternoon for an important announcement that would affect them all.

Apart from poring over training reports and other indicators on the performance of the seven astronaut candidates, Gilruth was interested in assessing the men’s peer ratings in order to determine whether their opinions coincided with his own. He knew that in the public’s view the chief contender was undoubtedly the amiable red-headed Marine, John Glenn. And with very good reason – Glenn was a totally dedicated, rock-solid family man who spoke eloquently with pride and patriotism about the space program, and more than any of the other six candidates seemed to embody the ideals of a God-fearing, nationloving astronaut.

Unbeknown to the public, however, Glenn didn’t really stand a chance in a peer vote. In his eagerness to impress the NASA hierarchy and Mercury program officials with his abilities, and his famously pleasant countenance when dealing with the press, he had 4 A replacement astronaut

Dr. Robert Gilruth (far right) with the seven Mercury astronauts. (Photo: NASA)

First astronaut chosen 5

created a simmering resentment among his fellow candidates. Their major gripe came when he stepped over the line by angrily rebuking and lecturing them on their openly philandering ways with hordes of eager, willing women, which he insisted was not in keeping with the image they should portray to the public. The others resented being told by one of their own how to conduct their private lives, and this had a strong influence in their individual ratings. When it came to offering his own peer rating, Glenn unhesitatingly wrote Scott Carpenter’s name at the top of his list. They had become good friends during the astronaut selection process. For his part, Carpenter was one of those who looked at a person’s abilities and suitabilities, and this, combined with his friendship for the amiable Marine, meant that he placed Glenn at the top of his list.

This was no surprise, according to Ed Buckbee, NASA’s public affairs officer at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama from 1960 to 1970. “Scott was a kind, gentle and considerate man, never coming on as the cocky fighter pilot type. In my view, there always seemed to be a closeness between John Glenn and Scott. They jogged together when the other Mercury guys avoided running like the plague. They asked similar questions in briefings. They studied together and their families were close.”2

Later that day the seven astronauts were called back into Gilruth’s office, where he wasted little time in announcing that Alan Shepard would make the first suborbital flight. Next to fly he named as Grissom, followed by Glenn. Prior to their own missions, both men would serve as Shepard’s backup pilots.

“I did not say anything for about twenty seconds or so,” Shepard would recall. “I just looked at the floor. When I looked up, everyone in the room was staring at me. I was excited and happy, of course, but it was not a moment to crow.” The other six, despite their disappointment, managed to put smiles on their faces as they congratulated him.3

Gilruth then told the seven men that he would not be making the announcement official for some weeks, in order to take the pressure off the primary astronaut during critical mission training.

Privately, Glenn was shocked and then furious at not being selected for the first American space flight. Or even the second. At a subsequent press conference in San Diego, he momentarily lost his renowned cool when asked who of the seven would be the first to fly. “We would like to get away from the ‘first’ aspect,” he responded, a little testiness in his voice. “This is the beginning of many flights. Actually the second and third and fourth flights may accomplish far, far more scientifically than the first flight does. That first mission is going to be sort of an ‘Oh, gee whiz, look at me; here I am, Maw!’ type of deal, and you are probably going to get a limited amount of data back from it.”4

Never one to sit back and take defeat lightly, Glenn even decided to question Gilruth’s decision with the NASA administrators who were appointed following President Kennedy’s installation in the White House. However they refused to overturn the decision and a sullen Glenn temporarily withdrew completely from the public view, later confessing that it took a while for him to bounce back and once again involve himself in the important tasks at hand.

“Those were pretty rough days for me,” Glenn later admitted. “I guess I am a fairly dogged competitor, and getting left behind … was like always being a bridesmaid but never a bride.”5

Although sharing Glenn’s disappointment at the time, Scott Carpenter was far more philosophical about what he ultimately hoped to achieve in being an astronaut, as he explained to interviewer and space expert Ed Buckbee. “I think each of us had slightly different motivations. Some, I believe, wanted to be first. Some thought ahead to flying to the Moon and some thought of flying one day to Mars. My motivation was not much towards flying higher or faster or being first. I was motivated by curiosity to go to a place where man had never been and bring back understanding.”6

Despite the competition between them, the seven men also recognized that they were involved in a dangerous research program and would rely heavily on each other, as Scott Carpenter explained, “Everybody wanted to take the first flight, whatever it was. We were all in a heated competition with each other. But the Three Musketeers came to my mind –we were all for one, and one for all. Truly we were. Although we struggled sometimes with petty difficulties, we were all one team where the program was concerned.”

Scott Carpenter reporting for work outside the Mercury Control Center, Cape Canaveral. (Photo: NASA)

The peer review was an exercise often used as an evaluation tool in the military. When asked if he felt that Gilruth’s use of the review had been a determining factor in the selection process for the first flights, Carpenter said it might have been.

“Bob made the decision [and] he probably took the ratings into consideration – he never told us what his decision-making process was. But I remember saying, in my peer review, that John was my first choice as backup, and conversely that if I had to be anyone’s backup then I’d prefer being John’s. Of course, in the end, John got the flight. I have an idea he named me as his backup of choice. So John got two things he wanted, and I only got one of mine!”7

GO FOR ORBIT

On 5 May 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American to fly into space, strapped into a compact spacecraft he had named Freedom 7, on suborbital mission MR-3 (a designation meaning the third launch of the Mercury-Redstone combination). Much to his and the country’s chagrin, he had been beaten into space just three weeks earlier by Lieut. Yuri Gagarin of the Soviet Union, who had completed a single orbit of the Earth in a Vostok spacecraft.

Carpenter outside the Mercury Control Center again, this time clad in his Mercury pressure suit. (Photo: NASA)

During Shepard’s flight, Scott Carpenter said that he and Wally Schirra were assigned the duty of chase plane pilots, observing the launch from high over the Cape in F-102 jets.

“For Alan’s flight, Wally Schirra and I, in keeping with an old Air Force – Edwards [Air Force Base, California], as a matter of fact – practice of chasing every experimental flight with airplanes … Walt Williams from Edwards, highly placed in the administration in those days, thought we should chase Al Shepard’s flight just because it was always done. So Wally Schirra and I were given some Air Force airplanes to chase Al’s flight. We orbited and we couldn’t stay close to the pad, because there were a lot of unknowns and dangers in those days that we didn’t quite know how to cope with. But Wally and I were circling the pad, listening to the count, but at some distance, maybe 3 miles away. And Al took off, going straight up, and Wally and I never saw a thing! You can’t chase a Redstone going straight up in a 102, so all we did is fly circles. And we came down and sort of said to each other, ‘What happened?’”8

Gus Grissom followed Shepard two months later on the similar suborbital MR-4 mission. Both were successful ballistic flights, although Grissom’s spacecraft was lost when the hatch on Liberty Bell 7 blew prematurely and the capsule sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. John Glenn had acted as a backup pilot for both missions, and was next in line for his own suborbital shot. Then things changed.

6 August 1961 would prove a turning point for NASA, when a second Soviet cosmonaut was fired into space. This time the pilot was Gherman Titov, who successfully flew 17 orbits aboard the Vostok-2 spacecraft. Now that the United States was fully engaged in a full-on race to the Moon, announced that May by President Kennedy, Gilruth and his advisors saw little point in pressing ahead with further suborbital flights. The modified Atlas rocket was ready to launch astronauts into orbit, and for their part the astronauts were more than ready. It was time for another astronaut get-together in Gilruth’s office.

The meeting between the seven Mercury astronauts and Robert Gilruth, now Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, and his deputy, Walt Williams, took place on 4 October 1961, coincidentally the fourth anniversary of the launch by the Soviet Union of the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik

This time the news was far more welcome to a delighted John Glenn. He would fly the MA-6 (Mercury-Atlas 6) first orbital mission, then scheduled for December. Scott Carpenter was named as his backup pilot. The follow-on mission, MA-7, went to Deke Slayton, with Wally Schirra acting as his backup. Shepard and Grissom would have to wait for their second flights, while a deeply disappointed Gordon Cooper, the youngest member of the group, had yet to be given his first mission assignment.

Glenn’s appointment to the MA-6 flight was not universally applauded within NASA. In 2013, Gus Grissom’s brother Lowell put up for auction a letter Gus had sent to their mother in October 1961. In the letter he confided that he and his fellow Mercury astronauts resented Glenn being selected to become the first American to orbit the Earth. “The flight crew for the orbital mission has been picked and I’m not on it,” he wrote. “Of course I’ve been feeling pretty low for the past few days. All of us are mad because Glenn was picked. But we expressed our views prior to the selection so there isn’t much we can do about it but support the flight and the program.” There may have been a bubbling resentment, but what the public saw in Life magazine and elsewhere in the media of the day was a unified team of astronauts eagerly preparing Glenn for his flight.9

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

New Orleans, though; would rather live in New Orleans than any other place in the world.

After a silence of some minutes, he said, abruptly—

“If I was free, I would go to Virginia, and see my old mudder.” He had left her when he was thirteen years old. He reckoned he was now thirty-three. “I don’t well know, dough, exactly, how old I is; but, I rec’lect, de day I was taken away, my ole mudder she tell me I was tirteen year old.” He did not like to come away at all; he “felt dreadful bad;” but, now he was used to it, he liked living here. He came across the Blue Ridge, and he recollected that, when he first saw it, he thought it was a dark piece of sky, and he wondered what it would be like when they came close to it. He was brought, with a great many other negroes, in waggons, to Louisville; and then they were put on board a steamboat, and brought down here. He was sold, and put on this plantation, and had been on it ever since. He had been twice sold, along with it. Folks didn’t very often sell their servants away here, as they did in Virginia. They were selling their servants, in Virginia, all the time; but, here, they did not very often sell them, except they run away When a man would run away, and they could not do anything with him, they always sold him off. The people were almost all French. “Were there any French in New York?” he asked. I told him there were; but not as many as in Louisiana. “I s’pose dah is more of French people in Lusiana, dan dah is anywhar else in all de world—a’nt dah, massa?”

“Except in France.”

“Wa’s dat, sar?”

“France is the country where all the Frenchmen came from, in the first place.”

“Wa’s dat France, massa?”

“France is a country across the ocean, the big water, beyond Virginia, where all the Frenchmen first came from; just as the black people all came first from Africa, you know.”

“I’ve heered, massa, dat dey sell one anoder dah, in de fus place. Does you know, sar, was dat so?” This was said very gravely.

I explained the savage custom of making slaves of prisoners of war, and described the constant wars of the native Africans. I told him that they were better off here than they would be to be the slaves of cruel savages, in Africa. He turned, and looking me anxiously in the face, like a child, asked:

“Is de brack folks better off to be here, massa?”

I answered that I thought so; and described the heathenish barbarism of the people of Africa. I made exception of Liberia, knowing that his master thought of some time sending him there, and described it as a place that was settled by negroes who went back there from this country. He said he had heard of it, and that they had sent a great many free negroes from New Orleans there.

After a moment’s pause, he inquired—very gravely, again:

“Why is it, massa, when de brack people is free, dey wants to send ’em away out of dis country?”

The question took me aback. After bungling a little—for I did not like to tell him the white people were afraid to have them stay here—I said that it was thought to be a better place for them there. He replied, he should think, that, when they had got used to this country, it was much better that they should be allowed to stay here. He would not like to go out of this country. He wouldn’t like even to go to Virginia now, though Virginia was such a pleasant country; he had been here so long, seemed like this was the best place for him to live. To avoid discussion of the point, I asked what he would do, if he were free?

“If I was free, massa; if I was free (with great animation), I would—— well, sar, de fus thing I would do, if I was free, I would go to work for a year, and get some money for myself,—den—den—den, massa, dis is what I do—I buy me, fus place, a little house, and little lot land, and den—no; den—den—I would go to old Virginny, and see my old mudder. Yes, sar, I would like to do dat fus thing; den, when I com back, de fus thing I’d do, I’d get me a wife; den, I’d take her to my house, and I would live with her dar; and I would raise things in my

garden, and take ’em to New Orleans, and sell ’em dar, in de market. Dat’s de way I would live, if I was free.”

He said, in answer to further inquiries, that there were many free negroes all about this region. Some were very rich. He pointed out to me three plantations, within twenty miles, owned by coloured men. These bought black folks, he said, and had servants of their own. They were very bad masters, very hard and cruel—hadn’t any feeling. “You might think master, dat dey would be good to dar own nation; but dey is not. I will tell you de truth, massa; I know I’se got to answer; and it’s a fact, dey is very bad masters, sar. I’d rather be a servant to any man in de world, dan to a brack man. If I was sold to a brack man, I’d drown myself. I would dat—I’d drown myself! dough I shouldn’t like to do dat nudder; but I wouldn’t be sold to a coloured master for anyting.”

If he had got to be sold, he would like best to have an American master buy him. The French people did not clothe their servants well; though now they did much better than when he first came to Louisiana. The French masters were very severe, and “dey whip dar niggers most to deff—dey whip de flesh off of ’em.”

Nor did they feed them as well as the Americans. “Why, sometimes, massa, dey only gives ’em dry corn—don’t give out no meat at all.” I told him this could not be so, for the law required that every master should serve out meat to his negroes. “Oh, but some on ’em don’t mind Law, if he does say so, massa. Law never here; don’t know anything about him. Very often, dey only gives ’em dry corn—I knows dat; I sees de niggers. Didn’t you see de niggers on our plantation, sar? Well, you nebber see such a good-looking lot of niggers as ours on any of de French plantations, did you, massa? Why, dey all looks fat, and dey’s all got good clothes, and dey look as if dey all had plenty to eat, and hadn’t got no work to do, ha! ha! ha! Don’t dey? But dey does work, dough. Dey does a heap o’ work. But dey don’t work so hard as dey does on some ob de French plantations. Oh, dey does work too hard on dem, sometimes.”

“You work hard in the grinding season, don’t you?”

“O, yes; den we works hard; we has to work hard den: harder dan any oder time of year. But, I tell ‘ou, massa, I likes to hab de grinding season come; yes, I does—rader dan any oder time of year, dough we work so hard den. I wish it was grinding season all de year roun’—only Sundays.”

“Why?”

“Because—oh, because it’s merry and lively. All de brack people like it when we begin to grind.”

“You have to keep grinding Sundays?”

“Yes, can’t stop, when we begin to grind, till we get tru.”

“You don’t often work Sundays, except then?”

“No, massa! nebber works Sundays, except when der crap’s weedy, and we want to get tru ’fore rain comes; den, wen we work a Sunday, massa gives us some oder day for holiday—Monday, if we get tru.”

He said that, on the French plantations, they oftener work Sundays than on the American. They used to work almost always on Sundays, on the French plantations, when he was first brought to Louisiana; but they did not so much now.

We were passing a hamlet of cottages, occupied by Acadians, or what the planters call habitans, poor white French Creoles. The negroes had always been represented to me to despise the habitans, and to look upon them as their own inferiors; but William spoke of them respectfully; and, when I tempted him to sneer at their indolence and vagabond habits, refused to do so, but insisted very strenuously that they were “very good people,” orderly and industrious. He assured me that I was mistaken in supposing that the Creoles, who did not own slaves, did not live comfortably, or that they did not work as hard as they ought for their living. There were no better sort of people than they were, he thought.

He again recurred to the fortunate condition of the negroes on his master’s plantation. He thought it was the best plantation in the State, and he did not believe there was a better lot of negroes in the State; some few of them, whom his master had brought from his

former plantation, were old; but altogether, they were “as right good a lot of niggers” as could be found anywhere. They could do all the work that was necessary to be done on the plantation. On some old plantations they had not nearly as many negroes as they needed to make the crop, and they “drove ’em awful hard;” but it wasn’t so on his master’s: they could do all the work, and do it well, and it was the best worked plantation, and made the most sugar to the hand of any plantation he knew of. All the niggers had enough to eat, and were well clothed; their quarters were good, and they got a good many presents. He was going on enthusiastically, when I asked:

“Well, now, wouldn’t you rather live on such a plantation than to be free, William?”

“Oh! no, sir, I’d rather be free! Oh, yes, sir, I’d like it better to be free; I would dat, master.”

“Why would you?”

“Why, you see, master, if I was free—if I was free, I’d have all my time to myself. I’d rather work for myself. Yes. I’d like dat better.”

“But then, you know, you’d have to take care of yourself, and you’d get poor.”

“No, sir, I would not get poor, I would get rich; for you see, master, then I’d work all the time for myself.”

“Suppose all the black people on your plantation, or all the black people in the country were made free at once, what do you think would become of them?—what would they do, do you think? You don’t suppose there would be much sugar raised, do you?”

“Why, yes, master, I do. Why not, sir? What would de brack people do? Wouldn’t dey hab to work for dar libben? and de wite people own all de land—war dey goin’ to work? Dey hire demself right out again, and work all de same as before. And den, wen dey work for demself, dey work harder dan dey do now to get more wages—a heap harder. I tink so, sir. I would do so, sir. I would work for hire. I don’t own any land; I hab to work right away again for massa, to get some money.”

Perceiving from the readiness of these answers that the subject had been a familiar one with him, I immediately asked: “The black people talk among themselves about this, do they; and they think so generally?”

“Oh! yes, sir; dey talk so; dat’s wat dey tink.”

“Then they talk about being free a good deal, do they?”

“Yes, sir Dey—dat is, dey say dey wish it was so; dat’s all dey talk, master—dat’s all, sir.”

His caution was evidently excited, and I inquired no further. We were passing a large old plantation, the cabins of the negroes upon which were wretched hovels—small, without windows, and dilapidated. A large gang of negroes were at work by the road-side, planting cane. Two white men were sitting on horseback, looking at them, and a negro-driver was walking among them, with a whip in his hand.

William said that this was an old Creole plantation, and the negroes on it were worked very hard. There was three times as much land in it as in his master’s, and only about the same number of negroes to work it. I observed, however, that a good deal of land had been left uncultivated the previous year. The slaves appeared to be working hard; they were shabbily clothed, and had a cowed expression, looking on the ground, not even glancing at us, as we passed, and were perfectly silent.

“Dem’s all Creole niggers,” said William: “ain’t no Virginny niggers dah. I reckon you didn’t see no such looking niggers as dem on our plantation, did you, master?”

After answering some inquiries about the levee, close inside of which the road continually ran, he asked me about the levee at New York; and when informed that we had not any levee, asked me with a good deal of surprise, how we kept the water out? I explained to him that the land was higher than the water, and was not liable, as it was in Louisiana, to be overflowed. I could not make him understand this. He seemed never to have considered that it was not the natural order of things that land should be lower than water, or that men

should be able to live on land, except by excluding water artificially At length, he said:—

“I s’pose dis heah State is de lowest State dar is in de world. Dar ain’t no odder State dat is low so as dis is. I s’pose it is five thousand five hundred feet lower dan any odder State.”

“What?”

“I spose, master, dat dis heah State is five thousand five hundred feet lower down dan any odder, ain’t it, sir?”

“I don’t understand you.”

“I say dis heah is de lowest ob de States, master. I s’pose it’s five thousand five hundred feet lower dan any odder; lower down, ain’t it, master?”

“Yes, it’s very low.”

This is a good illustration of the child-like quality common in the negroes, and which in him was particularly noticeable, notwithstanding the shrewdness of some of his observations. Such an apparent mingling of simplicity and cunning, ingenuousness and slyness, detracted much from the weight of his opinions and purposes in regard to freedom. I could not but have a strong doubt if he would keep to his word, if the opportunity were allowed him to try his ability to take care of himself.

CHAPTER IX. FROM LOUISIANA THROUGH TEXAS.

The largest part of the cotton crop of the United States is now produced in the Mississippi valley, including the lands contiguous to its great Southern tributary streams, the Red River and others. The proportion of the whole crop which is produced in this region is constantly and very rapidly increasing. This increase is chiefly gained by the forming of new plantations and the transfer of slavelabour westward. The common planter of this region lives very differently to those whose plantations I have hitherto described. What a very different person he is, and what a very different thing his plantation is from the class usually visited by travellers in the South, I learned by an extended experience. I presume myself to have been ordinarily well-informed when I started from home, but up to this point in my first journey had no correct idea of the condition and character of the common cotton-planters. I use the word common in reference to the whole region: there are some small districts in which the common planter is a rich man—really rich. But over the whole district there are comparatively few of these, and in this chapter I wish to show what the many are—as I found them. I shall draw for this purpose upon a record of experience extending through nearly twelve months, but obtained in different journeys and in two different years.

My first observation of the common cotton-planters was had on the steamboat, between Montgomery and Mobile, and has already been described. My second experience among them was on a steamboat bound up Red River.

On a certain Saturday morning, when I had determined upon the trip, I found that two boats, the Swamp Fox and the St. Charles, were advertised to leave the same evening, for the Red River. I went to the levee, and, finding the Saint Charles to be the better of the two, I

asked her clerk if I could engage a state-room. There was just one state-room berth left unengaged; I was requested to place my name against its number on the passenger-book; and did so, understanding that it was thus secured for me.

Having taken leave of my friends, I had my luggage brought down, and went on board at half-past three—the boat being advertised to sail at four. Four o’clock passed, and freight was still being taken on —a fire had been made in the furnace, and the boat’s big bell was rung. I noticed that the Swamp Fox was also firing up, and that her bell rang whenever ours did—though she was not advertised to sail till five. At length, when five o’clock came, the clerk told me he thought, perhaps, they would not be able to get off at all that night— there was so much freight still to come on board. Six o’clock arrived, and he felt certain that, if they did get off that night, it would not be till very late. At half-past six, he said the captain had not come on board yet, and he was quite sure they would not be able to get off that night. I prepared to return to the hotel, and asked if they would leave in the morning. He thought not. He was confident they would not. He was positive they could not leave now, before Monday—Monday noon. Monday at twelve o’clock—I might rely upon it.

Monday morning, The Picayune stated, editorially, that the floating palace, the St. Charles, would leave for Shreveport, at five o’clock, and if anybody wanted to make a quick and luxurious trip up Red River, with a jolly good soul, Captain Lickup was in command. It also stated, in another paragraph, that, if any of its friends had any business up Red River, Captain Pitchup was a whole-souled veteran in that trade, and was going up with that remarkably low draftfavourite, the Swamp Fox, to leave at four o’clock that evening. Both boats were also announced, in the advertising columns, to leave at four o’clock.

As the clerk had said noon, however, I thought there might have been a misprint in the newspaper announcements, and so went on board the St. Charles again before twelve. The clerk informed me that the newspaper was right—they had finally concluded not to sail till four o’clock. Before four, I returned again, and the boat again fired up, and rang her bell. So did the Swamp Fox. Neither, however, was

quite ready to leave at four o’clock. Not quite ready at five. Even at six—not yet quite ready. At seven, the fires having burned out in the furnace, and the stevedores having gone away, leaving a quantity of freight yet on the dock, without advising this time with the clerk, I had my baggage re-transferred to the hotel.

A similar performance was repeated on Tuesday.

On Wednesday, I found the berth I had engaged occupied by a very strong man, who was not very polite, when I informed him that I believed there was some mistake—that the berth he was using had been engaged to me. I went to the clerk, who said that he was sorry, but that, as I had not stayed on board at night, and had not paid for the berth, he had not been sure that I should go, and he had, therefore, given it to the gentleman who now had it in possession, and whom, he thought, it would not be best to try to reason out of it. He was very busy, he observed, because the boat was going to start at four o’clock; if I would now pay him the price of passage, he would do the best he could for me. When he had time to examine, he could probably put me in some other state-room, perhaps quite as good a one as that I had lost. Meanwhile he kindly offered me the temporary use of his private state-room. I inquired if it was quite certain that the boat would get off at four; for I had been asked to dine with a friend, at three o’clock. There was not the smallest doubt of it—at four they would leave. They were all ready, at that moment, and only waited till four, because the agent had advertised that they would—merely a technical point of honour.

But, by some error of calculation, I suppose, she didn’t go at four. Nor at five. Nor at six.

At seven o’clock, the Swamp Fox and the St. Charles were both discharging dense smoke from their chimneys, blowing steam, and ringing bells. It was obvious that each was making every exertion to get off before the other. The captains of both boats stood at the break of the hurricane deck, apparently waiting in great impatience for the mails to come on board.

The St. Charles was crowded with passengers, and her decks were piled high with freight. Bumboatmen, about the bows, were offering

shells, and oranges, and bananas; and newsboys, and peddlers, and tract distributors, were squeezing about with their wares among the passengers. I had confidence in their instinct; there had been no such numbers of them the previous evenings, and I made up my mind, although past seven o’clock, that the St. Charles would not let her fires go down again.

Among the peddlers there were two of “cheap literature,” and among their yellow covers, each had two or three copies of the cheap edition (pamphlet) of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” They did not cry it out as they did the other books they had, but held it forth among others, so its title could be seen. One of them told me he carried it because gentlemen often inquired for it, and he sold a good many; at least three copies were sold to passengers on the boat. Another young man, who looked like a beneficiary of the Education Society, endeavouring to pass a college vacation in a useful and profitable manner, was peddling a Bible Defence of Slavery, which he made eloquent appeals, in the manner of a pastoral visit, to us, each personally, to purchase. He said it was prepared by a clergyman of Kentucky, and every slaveholder ought to possess it. When he came to me, I told him that I owned no slaves, and therefore had no occasion for it. He answered that the world was before me, and I perhaps yet might own many of them. I replied so decidedly that I should not, that he appeared to be satisfied that my conscience would not need the book, and turned back again to a man sitting beside me, who had before refused to look at it. He now urged again that he should do so, and forced it into his hands, open at the titlepage, on which was a vignette, representing a circle of coloured gentlemen and ladies, sitting around a fire-place with a white person standing behind them, like a servant, reading from a book. “Here we see the African race as it is in America, under the blessed——”

“Now you go to hell! I’ve told you three times I didn’t want your book. If you bring it here again I’ll throw it overboard. I own niggers; and I calculate to own more of ’em, if I can get ’em, but I don’t want any damn’d preachin’ about it.”

That was the last I saw of the book-peddler.

It was twenty minutes after seven when the captain observed— scanning the levee in every direction, to see if there was another cart or carriage coming towards us—“No use waiting any longer, I reckon: throw off, Mr. Heady.” (The Swamp Fox did not leave, I afterwards heard, till the following Saturday.)

We backed out, winded round head up, and as we began to breast the current a dozen of the negro boat-hands, standing on the freight, piled up on the low forecastle, began to sing, waving hats and handkerchiefs, and shirts lashed to poles, towards the people who stood on the sterns of the steamboats at the levee. After losing a few lines, I copied literally into my note-book:

“Ye see dem boat way dah ahead.

Chorus.—Oahoiohieu.

De San Charles is arter ’em, dey mus go behine.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu,

So stir up dah, my livelies, stir her up; (pointing to the furnaces).

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Dey’s burnin’ not’n but fat and rosum.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Oh, we is gwine up de Red River, oh!

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Oh, we mus part from you dah asho’.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Give my lub to Dinah, oh!

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

For we is gwine up de Red River.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Yes, we is gwine up de Red River.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.

Oh, we must part from you dah, oh.

Cho.—Oahoiohieu.”

The wit introduced into these songs has, I suspect, been rather over estimated.

As soon as the song was ended, I went into the cabin to remind the clerk to obtain a berth for me. I found two brilliant supper-tables reaching the whole length of the long cabin, and a file of men

standing on each side of both of them, ready to take seats as soon as the signal was given.

The clerk was in his room, with two other men, and appeared to be more occupied than ever. His manner was, I thought, now rather cool, not to say rude; and he very distinctly informed me that every berth was occupied, and he didn’t know where I was to sleep. He judged I was able to take care of myself; and if I was not, he was quite sure that he had too much to do to give all his time to my surveillance. I then went to the commander, and told him that I thought myself entitled to a berth. I had paid for one, and should not have taken passage in the boat, if it had not been promised me. I was not disposed to fight for it, particularly as the gentleman occupying the berth engaged to me was a deal bigger fellow than I, and also carried a bigger knife; but I thought the clerk was accountable to me for a berth, and I begged that he would inform him so. He replied that the clerk probably knew his business; he had nothing to do with it; and walked away from me. I then addressed myself to a second clerk, or sub-officer of some denomination, who more good-naturedly informed me that half the company were in the same condition as myself, and I needn’t be alarmed, cots would be provided for us.

As I saw that the supper-table was likely to be crowded, I asked if there would be a second table. “Yes, they’ll keep on eatin’ till they all get through.” I walked the deck till I saw those who had been first seated at the table coming out; then going in, I found the table still crowded, while many stood waiting to take seats as fast as any were vacated. I obtained one for myself at length, and had no sooner occupied it than two half-intoxicated and garrulous men took the adjoining stools.

It was near nine o’clock before the tables were cleared away, and immediately afterwards the waiters began to rig a framework for sleeping-cots in their place. These cots were simply canvas shelves, five feet and a half long, two wide, and less than two feet apart, perpendicularly. A waiter, whose good will I had purchased at the supper-table, gave me a hint to secure one of them for myself, as soon as they were erected, by putting my hat in it. I did so, and saw

that others did the same. I chose a cot as near as possible to the midship doors of the cabin, perceiving that there was not likely to be the best possible air, after all the passengers were laid up for the night, in this compact manner.

Nearly as fast as the cots were ready they were occupied. To make sure that mine was not stolen from me, I also, without much undressing, laid myself away. A single blanket was the only bedclothing provided. I had not lain long, before I was driven, by an exceedingly offensive smell, to search for a cleaner neighbourhood; but I found all the cots, fore and aft were either occupied or engaged. I immediately returned, and that I might have a dernier ressort, left my shawl in that I had first obtained.

In the forward part of the cabin there was a bar, a stove, a table, and a placard of rules, forbidding smoking, gambling, and swearing in the cabin, and a close company of drinkers, smokers, card-players, and constant swearers. I went out, and stepped down to the boiler-deck. The boat had been provided with very poor wood, and the firemen were crowding it into the furnaces whenever they could find room for it, driving smaller sticks between the larger ones at the top, by a battering-ram method.

Most of the firemen were Irish born; one with whom I conversed was English. He said they were divided into three watches, each working four hours at a time, and all hands liable to be called, when wooding, or landing, or taking on freight, to assist the deck hands. They were paid now but thirty dollars a month—ordinarily forty, and sometimes sixty—and board. He was a sailor bred. This boat-life was harder than seafaring, but the pay was better, and the trips were short. The regular thing was to make two trips, and then lay up for a spree. It would be too hard upon a man, he thought, to pursue it regularly; two trips “on end” was as much as a man could stand. He must then take a “refreshment.” Working this way for three weeks, and then refreshing for about one, he did not think it was unhealthy, no more so than ordinary seafaring. He concluded, by informing me that the most striking peculiarity of the business was, that it kept a man, notwithstanding wholesale periodical refreshment, very dry. He was of opinion that after the information I had obtained, if I gave him at

least the price of a single drink, and some tobacco, it would be characteristic of a gentleman.

Going round behind the furnace, I found a large quantity of freight: hogsheads, barrels, cases, bales, boxes, nail-rods, rolls of leather, ploughs, cotton, bale-rope, and fire-wood, all thrown together in the most confused manner, with hot steam-pipes, and parts of the engine crossing through it. As I explored further aft, I found negroes lying asleep, in all postures, upon the freight. A single group only, of five or six, appeared to be awake, and as I drew near they commenced to sing a Methodist hymn, not loudly, as negroes generally do, but, as it seemed to me, with a good deal of tenderness and feeling; a few white people—men, women, and children—were lying here and there, among the negroes. Altogether, I learned we had two hundred of these deck passengers, black and white. A stove, by which they could fry bacon, was the only furniture provided for them by the boat. They carried with them their provisions for the voyage, and had their choice of the freight for beds.

As I came to the bows again, and was about to ascend to the cabin, two men came down, one of whom I recognized to have been my cot neighbour. “Where’s a bucket?” said he. “By thunder! this fellow was so strong I could not sleep by him, so I stumped him to come down and wash his feet.” “I am much obliged to you,” said I; and I was, very much; the man had been lying in the cot beneath mine, to which I now returned and soon fell asleep.

I awoke about midnight. There was an unusual jar in the boat, and an evident excitement among people whom I could hear talking on deck. I rolled out of my cot, and stepped out on the gallery. The steamboat Kimball was running head-and-head with us, and so close that one might have jumped easily from our paddle-box on to her guards. A few other passengers had turned out beside myself, and most of the waiters were leaning on the rail of the gallery. Occasionally a few words of banter passed between them and the waiters of the Kimball; below, the firemen were shouting as they crowded the furnaces, and some one could be heard cheering them: “Shove her up, boys! Shove her up! Give her hell!” “She’s got to hold

a conversation with us before she gets by, anyhow,” said one of the negroes. “Ye har that ar’ whistlin’?” said a white man; “tell ye thar an’t any too much water in her bilers when ye har that.” I laughed silently, but was not without a slight expectant sensation, which Burke would perhaps have called sublime. At length the Kimball slowly drew ahead, crossed our bow, and the contest was given up. “De ole lady too heavy,” said a waiter; “if I could pitch a few ton of dat ar freight off her bow, I’d bet de Kimball would be askin’ her to show de way mighty quick.”

At half-past four o’clock a hand-bell was rung in the cabin, and soon afterwards I was informed that I must get up, that the servants might remove the cot arrangement, and clear the cabin for the breakfasttable.

Breakfast was not ready till half-past seven. The passengers, one set after another, and then the pilots, clerks, mates, and engineers, and then the free coloured people, and then the waiters, chambermaids, and passengers’ body servants, having breakfasted, the tables were cleared, and the cabin swept. The tables were then again laid for dinner Thus the greater part of the cabin was constantly occupied, and the passengers who had no state-rooms were driven to herd in the vicinity of the card-tables and the bar, the lobby (Social Hall, I believe it is called), in which most of the passengers’ baggage was deposited, or to go outside. Every part of the boat, except the bleak hurricane deck, was crowded; and so large a number of equally uncomfortable and disagreeable people I think I never saw elsewhere together. We made very slow progress, landing, it seems to me, after we entered Red River, at every “bend,” “bottom,” “bayou,” “point,” and “plantation” that came in sight; often for no other object than to roll out a barrel of flour, or a keg of nails; sometimes merely to furnish newspapers to a wealthy planter, who had much cotton to send to market, and whom it was therefore desirable to please.

I was sitting one day on the forward gallery, watching a pair of ducks, that were alternately floating on the river, and flying further ahead as the steamer approached them. A man standing near me drew a long barrelled and very finely-finished pistol from his coat pocket, and,

resting it against a stanchion, took aim at them. They were, I judged, full the boat’s own length—not less than two hundred feet—from us, and were just raising their wings to fly, when he fired. One of them only rose; the other flapped round and round, and when within ten yards of the boat, dived. The bullet had broken its wing. So remarkable a shot excited, of course, not a little admiration and conversation. Half a dozen other men standing near at once drew pistols or revolvers from under their clothing, and several were fired at floating chips, or objects on the shore. I saw no more remarkable shooting, however; and that the duck should have been hit at such a distance, was generally considered a piece of luck. A man who had been “in the Rangers” said that all his company could put a ball into a tree, the size of a mans body, at sixty paces, at every shot, with Colt’s army revolver, not taking steady aim, but firing at the jerk of the arm.

This pistol episode was almost the only entertainment in which the passengers engaged themselves, except eating, drinking, smoking, conversation, and card-playing. Gambling was constantly going on, day and night. I don’t think there was an interruption to it of fifteen minutes in three days. The conversation was almost exclusively confined to the topics of steamboats, liquors, cards, black-land, redland, bottom-land, timber-land, warrants, and locations, sugar, cotton, corn, and negroes.

After the first night, I preferred to sleep on the trunks in the social hall, rather than among the cots in the crowded cabin, and several others did the same. There were, in fact, not cots enough for all the passengers excluded from the state-rooms. I found that some, and I presume most of the passengers, by making the clerk believe that they would otherwise take the Swamp Fox, had obtained their passage at considerably less price than I had paid.

On the third day, just after the dinner-bell had rung, and most of the passengers had gone into the cabin, I was sitting alone on the gallery, reading a pamphlet, when a well-dressed middle-aged man accosted me.

“Is that the book they call Uncle Tom’s Cabin, you are reading, sir?”

“No, sir.”

“I did not know but it was; I see that there are two or three gentlemen on board that have got it. I suppose I might have got it in New Orleans: I wish I had. Have you ever seen it, sir?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m told it shows up Slavery in very high colours.”

“Yes, sir, it shows the evils of Slavery very strongly.”

He took a chair near me, and said that, if it represented extreme cases as if they were general, it was not fair.

Perceiving that he was disposed to discuss the matter, I said that I was a Northern man, and perhaps not well able to judge; but that I thought that a certain degree of cruelty was necessary to make slave-labour generally profitable, and that not many were disposed to be more severe than they thought necessary. I believed there was little wanton cruelty. He answered, that Northern men were much mistaken in supposing that slaves were generally ill-treated. He was a merchant, but he owned a plantation, and he just wished I could see his negroes. “Why, sir,” he continued, “my niggers’ children all go regularly to a Sunday-school, just the same as my own, and learn verses, and catechism, and hymns. Every one of my grown-up niggers are pious, every one of them, and members of the church.

I’ve got an old man that can pray——well, sir, I only wish I had as good a gift at praying! I wish you could just hear him pray. There are cases in which niggers are badly used; but they are not common. There are brutes everywhere. You have men, at the North, who whip their wives—and they kill them sometimes.”

“Certainly, we have, sir; there are plenty of brutes at the North; but our law, you must remember, does not compel women to submit themselves to their power. A wife, cruelly treated, can escape from her husband, and can compel him to give her subsistence, and to cease from doing her harm. A woman could defend herself against her husband’s cruelty, and the law would sustain her.”

“It would not be safe to receive negroes’ testimony against white people; they would be always plotting against their masters, if you

did.”

“Wives are not always plotting against their husbands.”

“Husband and wife is a very different thing from master and slave.”

“Your remark, that a bad man might whip his wife, suggested an analogy, sir.”

“If the law was to forbid whipping altogether, the authority of the master would be at an end.”

“And if you allow bad men to own slaves, and allow them to whip them, and deny the slave the privilege of resisting cruelty, do you not show that you think it is necessary to permit cruelty, in order to sustain the authority of masters, in general, over their slaves? That is, you establish cruelty as a necessity of Slavery—do you not?”

“No more than of marriage, because men may whip their wives cruelly.”

“Excuse me, sir; the law does all it can, to prevent such cruelty between husband and wife; between master and slave it does not, because it cannot, without weakening the necessary authority of the master—that is, without destroying Slavery. It is, therefore, a fair argument against Slavery, to show how cruelly this necessity, of sustaining the authority of cruel and passionate men over their slaves, sometimes operates.”

He asked what it was Uncle Tom “tried to make out.”

I narrated the Red River episode, and asked if such things could not possibly occur.

“Yes,” replied he, “but very rarely. I don’t know a man, in my parish, that could do such a thing. There are two men, though, in——, bad enough to do it, I believe; but it isn’t a likely story, at all. In the first place, no coloured woman would be likely to offer any resistance, if a white man should want to seduce her.”

After further conversation, he said, that a planter had been tried for injuring one of his negroes, at the court in his parish, the preceding summer. He had had a favourite, among his girls, and suspecting