Ancient Ink THE ARCHAEOLOGY

OF TATTOOING

Edited by LARS KRUTAK and

AARON DETER-WOLF

McLellan Book

University of Washington Press

Seattle & London

A

Ancient Ink was made possible in part by a grant from Furthermore, a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

Additional support was provided by the McLellan Endowment, established through the generosity of Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams.

Copyright © 2017 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Katrina Noble

Layout by Jennifer Shontz, www.redshoedesign.com

21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

isbn (hardcover): 978-0-295-74282-3

isbn (paperback): 978-0-295-74283-0

isbn (ebook): 978-0-295-74284-7

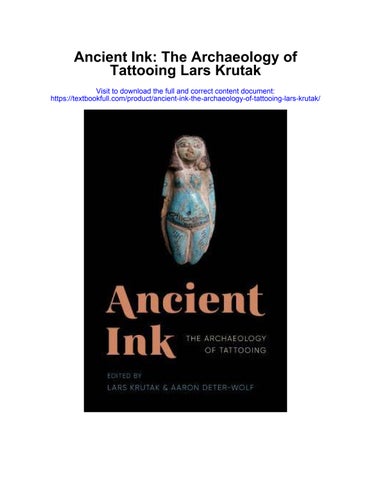

Front cover: Egyptian faience figurine with tattoos on truncated legs (ca. 1980−1800 bce); not to scale. Photograph by Renée Friedman. British Museum, London (EA52863)

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z 39.48–1984. ∞

To the memory of

Paul R. Krutak (1934−2016),

Daniel R. Deter (1948−2015), and Leonid T. Yablonsky (1950−2016)

I suppose . . . that the value of these artifacts lies in how one looks at them.

—Susie Silook, St. Lawrence Island Yupik artist (2009)

Acknowledgments

Aaron Deter-Wolf and Lars Krutak

Part 1: Skin

1 New Tattoos from Ancient Egypt: Defining Marks of Culture

Renée Friedman 11

2 Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines

Analyn Salvador-Amores

3 Reviving Tribal Tattoo Traditions of the Philippines

Lars Krutak

4 The Mummification Process among the “Fire Mummies” of Kabayan: A Paleohistological Note

Dario Piombino-Mascali, Ronald G. Beckett, Orlando V. Abinion, and Dong Hoon Shin

5 Identifications of Iron Age Tattoos from the Altai-Sayan Mountains in Russia

Svetlana Pankova 66

6 Neo-Pazyryk Tattoos: A Modern Revival

Colin Dale and Lars Krutak 99

7 Recovering the Nineteenth-Century European Tattoo: Collections, Contexts, and Techniques

Gemma Angel

8 After You Die: Preserving Tattooed Skin

Aaron Deter-Wolf and Lars Krutak

9 The Antiquity of Tattooing in Southeastern Europe Petar

Balkan Ink: Europe’s Oldest Living Tattoo Tradition

Archaeological Evidence for Tattooing in Polynesia and Micronesia

12 Reading Between Our Lines: Tattooing in Papua New Guinea Lars

Scratching the Surface: Mistaken Identifications of Tattoo Tools from Eastern North America Aaron Deter-Wolf, Benoît Robitaille, and Isaac Walters

14 Native North American Tattoo Revival Lars

15 The Discovery of a Sarmatian Tattoo Toolkit in Russia Leonid

Evaluation of Tattooing Use-Wear on Bone Tools

Aaron

What to Make of the Prehistory of Tattooing in Europe?

18 Sacrificing the Sacred: Tattooed Prehistoric Ivory Figures of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska

19 A Long Sleep: Reawakening Tattoo Traditions in Alaska

Color plates follow page 180.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This volume is intended as a modest contribution to the study of ancient tattooing practices and technology. The collection of essays is the outcome of many conversations over the years, including those held at international conferences: European Association of Archaeologists Annual Meetings (2010/2011, The Hague and Oslo); “Into the Skin: Identity, Symbols and History of Permanent Body Marks” conference (2011, Vatican City); 7th World Congress on Mummy Studies (2011, San Diego); and Musée du Quai Branly conference “Tattooed Images” (2015, Paris).

As a collaborative project, this book would not have been possible without the support of numerous individuals who provided guidance, contacts, imagery, stories, and tattoo knowledge, as well as humor when we needed it most. In this regard, we extend our appreciation to the St. Lawrence Island (Alaska) elders; Kalinga master tattooist Whang-Od; Elle Festin; Tina Astudillo-Ash; Mark of the Four Waves; Marjorie Tahbone; Qaiyaan and Jana Harcharek; Dave Mazierski; Alexander Yablonsky; Orlando Abinion; Art Tibaldo; Colin Dale of Skin & Bone Tattoo; Peter van der Helm; Tsvetan Chetashki; Ivan Vajsov; Svend Hansen; Cristina Georgescu; Zele of Zagreb Tattoo; Sasha Aleksandar of Orca Sun Tattoo; Carol Diaz-Granados; Jim Duncan; Johann Sawyer; Heidi Altman; Tanya Kanceljak; Tea Turalija Mihaljevic; Wal Ambrose; Julia Mage’au Gray, Nata Richards, and Ranu James (www.teptok.com); Ade Baroa; Vali Kolou; Taitá Koroka; Dion Kaszas of Vertigo Tattoo; Carla Wells-Listener; Alan White; Michael Galban; Kiano Zamani; Anna Felicity Friedman; Ethan Freeman; Matt Lodder; Sébastien Galliot; Francesco d’Errico; Gerhard Bosinski; Magda Lazarovici; Camilla Norman; Claire Alix; Owen Mason; Dave Hunt; Chris Dudar, and the two anonymous reviewers who offered critiques of the draft manuscript.

Documenting the antiquity, significance, and meaning of ancient tattooing would have been quite difficult without the assistance of the collectors, photographers, galleries, archives, museums, publishers, and institutional staff who provided permission to reproduce written documents, publications, objects of material culture, and photography. Our gratitude goes out to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London; the British Museum; Sudan National Museum; the Oriental Institute; Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford University; The State Hermitage Museum; Regional Historical Museum Veliko Turnovo; the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences; Auckland Museum; Orenburg Governor’s Museum of Local Lore and History; Editions Ophrys; Cotsen

Institute of Archaeology Press, UCLA; Institute for Prehistoric Archaeology, Free University Berlin; The American School of Classical Studies at Athens; Association Hellas et Roma; Donald Ellis Gallery; Angela Linn and Scott Shirar, of the University of Alaska Museum of the North; Dave Rosenthal and National Museum of Natural History; Sean Mooney, of the Rock Foundation Collection; National Museum of the American Indian; Daisy Njoku and the National Anthropological Archives; American Museum of Natural History Special Collections and Department of Anthropology; Bryan Just and Princeton University Art Museum; Bill and Carol Wolf Collection; Perry and Basha Lewis Collection; Anna Cannizzo and the Oshkosh Public Museum; Steve Davis and the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina; Neal Oshima and En Barong, Inc.; Joe Ash Photography; Kalynna Ashley Photography; Cora DeVos / Little Inuk Photography; and Charles Hamm and the National Association for the Preservation of Skin Art.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of a generous subvention grant and research grant from Flavia Robinson and the Daniele Agostino Derossi Foundation (Torino, Italy) for the senior editor’s travel to Papua New Guinea. We would also like to give special recognition to Lorri Hagman and her staff at the University of Washington Press for supporting the publication of this book, and to Ellen Wheat for copyediting the manuscript. Numerous others also assisted us during the course of writing and editing this book, and we thank you all for your invaluable support.

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

ANCIENT INK

Introduction

Aaron Deter-Wolf and Lars Krutak

The desire to alter, decorate, and adorn the human body is a cultural universal. While specific forms of body decoration and the underlying motivations vary according to region, culture, and era, human societies from the past and present have engaged in practices designed to enhance their natural appearance. Tattooing—the process of inserting pigment into the skin to create permanent designs and patterns—as a form of body decoration has been practiced by cultures around the globe and throughout human history. Preserved tattoos on mummified human remains demonstrate that the practice extends back to at least the fourth millennium BCE (Deter-Wolf et al. 2016). However, the exact antiquity and archaeological footprint of tattooing remain poorly understood, and it was not until recently that the various pieces of archaeological evidence for tattooing have been seriously or systematically evaluated by qualified scholars.

Over the past two decades there has been a surge in interest among both academics and the general public in learning more about ancient and historic tattooing. Researchers studying past societies have begun to recognize the importance of tattooing in both social and ritual contexts. Professional tattoo artists are increasingly interested in learning more about the history of their profession, about authentic ancient and historical motifs, and about the techniques involved in applying tattoos in the preelectric era. The ever-growing population of tattooed individuals (as well as those aspiring to become tattooed) are similarly intrigued by traditional tattoo methods, and by the designs and meanings of ancient and historic body art. Members of Indigenous cultures worldwide are actively seeking out information regarding the tattoo tools,

symbols, and significance associated with their unique cultural traditions, which were historically suppressed by colonial, missionary, and other acculturative agents.

Despite this growing interest, there are few solidly researched volumes examining ancient tattoo traditions. Those works are generally region specific (e.g., Deter-Wolf and Diaz-Granados 2013; Krutak 2014a), contain dated or suspect scholarship (e.g., Hambly 1925; van Dinter 2005), are generalist texts that do not contain in-depth or specific archaeological information, or are overly academic and unapproachable for the general public. In the absence of definitive source material, scholars, tattoo artists, and the interested public rely instead on questionable sources, including the fountain of readily accessible but often inaccurate information on the internet, to learn about the history and archaeology of tattooing. As a result, myths and misunderstandings are being perpetuated regarding the historical scope of tattooing, the historic and Indigenous tools, methods, and meanings, and the available archaeological evidence.

Ancient Ink is the first book dedicated to the archaeological study of tattooing. In the volume, we present essays by international researchers working to understand our shared human past through examination of the principal lines of archaeological evidence used to examine ancient and historic tattooing: preserved human skin, tattoo tools, and the artistic record. These studies contribute to our understanding of the antiquity, durability, and significance of tattooing and human body decoration by illuminating how different societies of the past have employed their skin in the construction of their identities. Moreover, they illustrate how ancient body art traditions connect to our modern culture through Indigenous tattoo revitalization efforts and the recontextualization of tattoo meanings and praxis through the work of contemporary artists. To this end, chapters alternate analyses of the archaeological record with descriptions of contemporary work by tattoo artists who employ historic and traditional techniques and/or imagery, thereby demonstrating the persistence of traditions discussed in the preceding chapter. When possible, the chapter authors draw parallels between modern and historic or Indigenous traditions.

Part 1: Skin

The first part of this volume addresses topics related to naturally and deliberately preserved tattooed human remains, which constitute the most spectacular and direct form of archaeological evidence of tattooing in ancient and historic societies. Hundreds of human mummies with tattooed skin have been recovered from archaeological settings around the globe, including in Europe, South America, Central America, North Africa, Western Asia, Siberia, the Philippines, and the Arctic (Deter-Wolf et al. 2016: table 1). Most of these finds were historically regarded as curiosities for collection and exhibition, but prior to the past decade—with the notable exception of the Tyrolean mummy known as Ötzi—only a few have undergone substantive documentation or analysis. In some cases, natural darkening of preserved skin as a result of age and weathering

obscured tattoos, and only with the application of new imaging technologies have these marks been discovered (e.g., Samadelli et al. 2015). Today, recognition of the cultural importance of tattooing combined with advances in imaging and detection technology facilitate new examinations and identifications of preserved tattooed remains both in the archaeological record and in museum collections. The authors in the first part describe new finds of preserved, tattooed skin, as well as new discoveries and analysis of previously recorded examples.

In chapter 1, Renée Freidman discusses recent identifications of preserved tattoos on Egyptian and Nubian C-Group mummies from the sites of Gebelein and Hierakonpolis. Freidman also marshals comparative evidence to identify a possible tattoo toolkit from Hierakonpolis Cemetery HK43, and reassesses the tattooed mummies discovered at Deir el Bahari in 1891. Altogether, these various lines of evidence engage tattoo traditions spanning the Predynastic period (ca. 3900−3100 BCE) through the New Kingdom (1550−1069 BCE), demonstrate the presence of separate and distinctive tattoo traditions in Egypt and Nubia, and entirely reframe our understanding of tattooing in the region. In addition, radiocarbon analysis reveals that the Gebelein mummies are the oldest tattooed remains yet discovered in Africa.

On the island of Luzon, Philippines, the burik (tattoo) tradition of the Indigenous Ibaloy people increasingly constitutes a significant aspect of historical and contemporary identity. In chapter 2, Analyn Salvador-Amores describes these burik practices as they appear in historical records, on the bodies of the Kabayan mummies, and as they are manifested in contemporary culture. In chapter 3, Lars Krutak describes the revival of Ibaloy and Filipino tattoo traditions through the work of the Kalinga tattooist Whang-Od and the Mark of the Four Waves Tribe. Finally, Dario Piombino-Mascali, Ronald G. Beckett, Orlando V. Albinion, and Dong Hoon Shin provide a formal histiological analysis of a Kabayan mummy in chapter 4. This study results in new insights concerning the substances and techniques used in local Filipino mummification practices.

The elaborate animal tattoos on the mummies of the Iron Age Pazyryk culture of Siberia regularly make their way through the news cycle and various social media feeds. However, reliable information on these finds has not—until now—been widely available to English-speaking audiences. In chapter 5, Svetlana Pankova describes preserved tattoos from both the Pazyryk and Tashtyk cultures of the Altai-Sayan region, spanning the period between approximately 300 BCE and 400 CE. Following this discussion, Colin Dale and Krutak explore the resurrection of Pazyryk tattoo motifs by Danish archaeologist Søren Nancke-Krogh, Canadian tattooist Steve Gilbert, and Canadian artist Dave Mazierksi.

In chapter 7, Gemma Angel turns our focus away from ancient mummies to examine early twentieth century specimens of tattooed human skin from the Wellcome Collection in London. This collection was originally purchased in 1929 for inclusion in a medical museum, and contains little contextual information regarding the individuals from whom the specimens were obtained. Angel provides a wealth of information

about historic European tattooing, including data on the methods and tools used, the iconography, and where tattooing and tattooed bodies fit into the early twentieth century European cultural milieu.

The preservation of tattooed human flesh has historically occurred mainly as a byproduct of either unintentional or deliberate mummification, or as a result of anatomical and medical studies. Today, tattooed individuals have the agency to intentionally preserve their own tattoos, with the assistance of several foundations. As described by Deter-Wolf and Krutak in chapter 8, the Foundation for the Art and Science of Tattooing and Save My Ink Forever will work with individuals to posthumously collect and protect their tattoos for posterity.

Part 2: Tools

Although tattooing has been practiced for millennia by cultures around the world, there have until recently been relatively few archaeological identifications of tattoo tools outside of Oceania (Deter-Wolf 2013a). This lack of identification is due to various factors, including the rapid historic abandonment of Indigenous tools in favor of European metal needles, the suppression of Indigenous tattoo traditions under colonial rule, and misunderstandings of tattoo techniques and technologies. Contributors to this part of the volume focus on the archaeological identification of tattoo implements, how these tools may be distinguished from other visually similar artifacts, and what they reveal about cultural development, change, and migration within past societies. In their efforts to identify and understand these artifacts, the authors employ a variety of lines of evidence, including human figural art, historic and ethnographic accounts, and both cross-cultural and use-wear analysis.

In chapter 9, Petar Zidarov uses art historical, historical, and archaeological evidence to suggest that tattooing in southeastern Europe existed as early as the sixth millennium BCE. Toward this end, he discusses the archaeological identification of bone tools from the Copper Age site of Pietrele, Romania, which may have functioned as tattoo implements. In a subsequent discussion in chapter 10, Krutak describes contemporary efforts to document historic tattoo traditions of the Balkans through the ethnographic work of Bosnian researcher Tea Mihaljevic and Croatian artists Zele and Sasha Aleksandar who incorporate traditional imagery into their modern tattoo work.

To the east in Polynesia, Louise Furey examines the distribution of Indigenous tattooing across Oceania in chapter 11. Her presentation of an island-by-island overview of archaeological materials demonstrates that while tattooing practices in the region share a common ancestry, the technology used to mark the body was quite diversified and functions as an important indicator of the settlement history of Oceania. In chapter 12, Krutak writes about the revival of Indigenous tattooing practices in coastal Papua New Guinea through the journey of four women of Papuan and Australian descent who traveled across Polynesia to resurrect them.

Turning to North America, in chapter 13 Aaron Deter-Wolf, Benoît Robitaille, and Isaac Walters examine issues surrounding the archaeological identification of ancient Native American tattoo tools from the Eastern Woodlands. The authors use a combination of archaeological, ethnographic, and historical data, including identification of rare surviving toolkits, to reiterate the ritual and technological differences between Native American tattooing, scarification, and scratching practices, and to address mistaken archaeological identifications of tattoo tools from the region.

Just as tattoos were closely linked to identity in ancient North America, today they testify to the resilience of Indigenous cultures and peoples. In chapter 14, Krutak probes the meanings of tattooing for contemporary Native tattoo bearers in Canada and the eastern United States, underscoring the role that tattoo revival efforts have had on the process of decolonization.

In chapter 15, Leonid Yablonsky expands our knowledge of the nomadic, early Iron Age Sarmatian people of Eurasia through recent discoveries of their tattooing material culture, the oldest evidence from this region. This long-awaited, but sadly posthumous, study of tattooing tools and related objects has an important role to play in reconstructing the tattoo history of these ancient nomadic people and their neighbors.

Deter-Wolf and Tara Nicole Clark address the task of developing use-wear analysis as a tool to identify tattoo tools in archaeological and museum collections in chapter 16. After creating a set of bone tools using prehistoric techniques, they then use those implements to tattoo both pig skin and human skin. Deter-Wolf and Clark then examine the microwear patterns created during the tattooing process in an attempt to both refine our understanding of the use-wear signature of tattooing, and assess the suitability of pig skin as a surrogate for human skin in future experimental studies.

Part 3: Art

Possible representations of human body decoration appear on anthropomorphic figurines and art dating back to at least 35,000 years ago. Although the artists who created these images intended to show alteration of the human skin, it is challenging for modern scholars to establish the specific type and permanence of the body decoration(s) in question. Some examples may represent clothing, while others may indicate tattooing, body paint, scarification, or something else altogether. Identifying the symbolic significance and ideological roles of these ancient objects can also be difficult. To address these problems, the final part of the book examines the artistic, ethnographic, and archaeological record of ancient and historic cultures from Europe and the Arctic in order to assess how members of those societies projected their decorated bodies onto their material culture.

In chapter 17, Luc Renaut turns a skeptical eye toward artistic depictions of possible ancient European tattooing. His examination spans the Upper Paleolithic through the Bronze Age, and describes anthropomorphic art recovered from numerous sites across

the continent in an effort to differentiate likely depictions of tattooing from works depicting other forms of body decoration.

The final chapters focus on the American Arctic, as Lars Krutak examines the prehistoric and historic use of decorated anthropomorphic dolls from Bering Strait. These religious objects, usually carved of walrus ivory, were employed in various rituals for more than two millennia, but the question of their tattoos has always remained a mystery. This study serves as a companion piece to Krutak’s subsequent brief survey of contemporary Indigenous tattooing in Alaska. Motivated by ancestral traditions, spiritual beliefs, and contemporary cultural values, a new generation of tattoo bearers has reawakened tattooing customs that were once in danger of disappearing forever.

The studies presented here are pioneering efforts in the analysis, recognition, and interpretation of tattooing instruments and practices worldwide. Indeed, tattooing is an almost universal human tradition that embodies an astonishing range of cultural meanings articulated through performance and permanent symbols. For millennia, tattooing has been more than mere ornamentation. Instead, the practice has been integral to the social fabric of community and religious life, and has anchored societal values on the skin for most everyone to see. Seen in this light, tattooing was, and continues to be, a system of knowledge transmission, a visual language of the skin whereby culture is inscribed, experienced, and preserved in myriad specific ways.

New Tattoos from Ancient Egypt

DEFINING MARKS OF CULTURE

Renée Friedman

Interpretations of the artistic record and certain tool sets suggest that body modification, and especially tattooing, was practiced by diverse cultures reaching back into remote antiquity (Deter-Wolf 2013a). Not surprisingly, given the nature of the medium—human skin—examples of actual tattoos are hard to come by in the archaeological record. Until recent discoveries in Europe and South America (see Deter-Wolf et al. 2016: table 1), Egypt’s Nile Valley provided the earliest actual evidence of the practice. The tattoos visible on three well-preserved individuals buried at Deir el Bahari in Thebes during the early Middle Kingdom (ca. 2004 BCE1) (map 1.1), and the more fragmentary remains from Kubban in Nubia, have long been known and widely reviewed.2 However, new observations using infrared imaging now extend the temporal range of known examples in Egypt from within the Predynastic (ca. 3900−3100 BCE) into the New Kingdom (1550−1069 BCE) (see table 1.1, which augments and updates Deter-Wolf et al. 2016: table 1). These recent discoveries not only allow ancient Egypt to regain its position among the earliest entries in the chronological table, but also, and more importantly, provide further information with which to reconsider the use of tattoos in the ancient Nile Valley by the various cultures living there and to identify artifacts related to the practice.

Five tattooed individuals from ancient Egypt discussed here were observed by the author in 2014−2016 using a Panasonic Lumix DMC ZS19 camera, preconverted by the sellers, Kolari Vision, to 720 nm infrared.3 While all were found on (and in) Egyptian soil, three can be identified as ethnically Nubian. These remains range in date from the

latter part of the Predynastic period to the Middle Kingdom, and the new evidence they preserve can now help us to distinguish more clearly enduring tattooing traditions both in Egypt and Nubia that were culturally specific with regard to both motifs and techniques.

Predynastic Tattoos

Infrared examination of the six naturally preserved Predynastic mummies obtained by the British Museum in 1899 from Gebelein in Upper Egypt (see map 1.1) revealed the presence of tattoos on the body of one female (BM EA32752) and one male (BM

Map 1.1. Ancient Egypt and Nubia, showing sites discussed in this chapter.

Table 1.1. Summary of tattooed mummies from Egypt and Nubia.

Date

3349−3093

BCE Predynastic Gebelein, Egypt BM EA32752

3340−3018

BCE Predynastic Gebelein, Egypt BM EA32751

2055−2004

BCE Dynasty XI (Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II)

2055−2004 BCE Dynasty XI (Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II)

1985−1955 BCE Dynasty XII (Amenemhet I?)

Deir el Bahari, Thebes, Egypt. Amunet

Deir el Bahari, Thebes, Egypt. Pits 23 and 26

Asasif, Thebes, Egypt.

1985−1855 BCE C-Group Nubia (first half of Dynasty XII) Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Cemetery HK27C.

F Discussed herein.

M Discussed herein.

F Fouquet 1898; Keimer 1948.

F 2 individuals Keimer 1948; Winlock 1923.

Asasif 1008 F Morris 2011: fig. 5.

Tombs 9, 10, 36

F 3 individuals Friedman 2004; Pieri and Antoine 2014; discussed herein.

1750−1500 BCE C-Group, Nubia Phase III Kubban, Nubia Cemetery 110. Grave 271 F Firth 1927.

ca. 1750 BCE Pan Grave Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Cemetery HK47. Burial 12 M Friedman 2016; discussed herein.

1295−1069 BCE New Kingdom, Egypt (Ramesside) Deir el Medina, Thebes, Egypt.

F 3 individuals Anne Austin, pers. comm.*; Watson 2016.

ca. 1000 BCE Late Period? Egypt Private collection, Perth, Australia. Poon 2008.

332 BCE−395 CE Graeco-Roman Period Akhmim, Egypt. F Unconfirmed** Strouhal 1992.

100 BCE−150 CE Meroitic Period, Nubia. Semna South, Sudan. N-247

100 BCE−150 CE Meroitic Period, Nubia. Aksha, Sudan. AM 4,12,32,36,43, 45,62,65,77,81.

F? Possibly 2 individuals Alvrus et al. 2001.

7F; 1M; 2U 10 tattooed individuals Vila 1967.

350−550 CE X Group, Nubia M Armelagos 1969.

700 CE Christian Period, Nubia. et-Tereif, Sudan Site 3-J-23. Grave 50 F Vandenbeusch and Antoine 2015.

*Personal communication, January 27, 2016. **Indirect identification, based on marks from mummy masks.

EA32751; Antoine and Ambers 2014: 26−28; Dawson and Gray 1968).4 On the female, these tattoos appear as very faint green marks under natural lighting conditions, but can be clearly distinguished in infrared. A mark present on the upper right arm is a linear motif bending nearly 90 degrees toward the front of the body (fig. 1.1a). On the right shoulder there is a series of four S-shaped motifs running vertically over the joint of the humerus and the shoulder (fig. 1.1b). At both ends of each S-motif the line appears to widen and terminate with a short perpendicular stroke. An irregular line was also detected running horizontally across the lower abdomen at approximately the level of the navel (see fig. 1.1c, marked by arrow), but the nature and origin of this particular mark remains unclear since the tight contraction of the legs hinders full view.5 Corresponding tattoos were not found on the left side, and no other markings were detected elsewhere on the body.

Fig. 1.1. Infrared image of the Predynastic female mummy from Gebelein (3349−3018 cal BCE) and details of the tattoos observed on the (a) right shoulder and (b) upper right arm. The tattoos on this individual appear as faint green marks under natural lighting conditions, but can be clearly distinguished in infrared (c). Photographs by Renée Friedman. British Museum, London (EA32752).

The male body (Gebelein Man A) is the best preserved natural mummy known from Predynastic Egypt, and also bears tattoos on his upper right arm (fig. 1.2a). The marks appear as dark smudges in natural light (figs 1.2b, 1.2c), but under infrared can be identified as two horned animals facing toward the front of the body. One is placed below and in front of the other, which it slightly overlaps. No marks are present on the shoulder and no further indications of tattooing could be detected on the portions of the body currently visible in the museum display.

Fig. 1.2. (a) Infrared image of the Predynastic male mummy from Gebelein (3349−3018 cal BCE) and details of the tattoos observed on the (b) upper right arm under infrared lighting and (c) natural lighting. These marks appear as dark smudges in natural light, but under infrared they resolve into two horned animals facing toward the front of the body. Photographs by Renée Friedman. British Museum, London (EA32751).

Recent accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon testing has dated both of these bodies from Gebelein to 3349−3018 cal BCE (with 95.4 percent confidence).6 Stylistic comparison of the tattoos with elements of material culture place them within the late and terminal phases of the Predynastic period7 and point to the earlier part of the broad dating range.8 Roughly contemporary with the Alpine mummy known as Ötzi (see Deter-Wolf et al. 2016), the Gebelein mummies have the oldest preserved tattoos in Africa, and are the second and third oldest tattooed mummies in the world.

Fig. 1.3. Detail of Predynastic pottery (ca. 3500 BCE) exhibiting S-motifs similar to the tattoos on the right shoulder of the female mummy from Gebelein. The specific meaning of this design is not known.

Photograph by Renée Friedman. British Museum, London (EA49570).

The female mummy is the earlier of the two examples from Gebelein. Both of her figural tattoos have parallels specifically in the material culture of the late Predynastic period (ca. 3450−3300 BCE). The S-motif is well known in pottery decoration of this period, where it occurs in multiples (fig. 1.3), like in the tattoo. To date we have no satisfactory explanation for the meaning of this motif, which has been identified as schematic birds in flight, and most recently as an indicator of emphasis or connection with other elements in a composition (Graff 2009:78, motif NI 35), a reading that is perhaps not out of place given the tattoo’s position on the shoulder.

The linear motif on the woman’s arm may be compared with the crooked staves carried as symbols of power and status, or the batons and/or clappers seen in the hands of mainly male figures in scenes depicting ceremonial activity and ritual dance, especially on pottery (Graff 2009:71 motif BT1-3). Such objects, as either symbols of status or implements of ritual performance, were no doubt redolent with power; however, neither they nor the S-motifs is ever the main focus of the compositions of scenes on pottery. Instead, their ancillary use on painted ceramics suggests that these tattoos are not directly related to the restricted vocabulary of pottery design, which was mainly

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

[Contents]

VII. J����� L���.

The first paragraph of the Shulchan-aruch runs thus: “ ‘I have set the Lord always before me’ is one of the most important principles of our holy Religion;” and, indeed, the more the actions of the Jew conform to this principle, the nearer does he approach the ideal of a true servant of God, who is faithful in the service of his Master, and whose life is the expression of genuine recognition of God’s sovereignty (םימש תוכלמ לוע תלבק) with unconditional obedience to His Will (תוצמ לוע תלבק). Neither attendance at Public Service, nor the regular recitation of prayers, nor the study of the Law, nor the performance of certain religious acts, constitute by themselves Jewish Life, but the supreme influence which the Word of God—the Torah—is constantly made to exercise over man’s doings. Every movement of his is regulated by the Law, and wherever he turns he is met by a Divine precept that elevates his heart towards Him who gave us the Law. The very garments he wears, though not different from those of his fellow-men,144 except by the [468]absence of shaatnez (combination of wool and linen), include the arba kanfoth, “the four-cornered garment,” with tsitsith; his house, the same in every other respect as those of his neighbours, is distinguished by the mezuzah on the doorposts. These distinctive characteristics, however, are not intended to attract the attention of others; they only concern the man himself; they serve him as reminders of God and His Will. Within the house the furniture and the whole arrangement are in accordance with the custom and fashion of the place;145 there

is simplicity or luxury, taste or want of taste, according to the individual character of the occupier. Only the kitchen and the table have a distinctly Jewish aspect; these must be adapted to the requirements of the Dietary Laws. The most striking feature is the double set of kitchen utensils and of vessels for the table, the one set for meat, the other for butter and milk.

In the choice of his occupation, trade, or profession, the Jew, like all his fellow-men, is influenced by his [469]inclination, capabilities, and opportunities; but, in addition to these, there is another important factor that must ultimately determine the choice—his religion; and such occupation as would be likely to compel him to abandon any of the Divine precepts, cannot be chosen. No manner of labour or trade is in itself derogatory; on the contrary, all labour is honourable, unless man degrades it by his conduct, and by the object he aims at achieving by means of it. Thrift, economy, and temperance are essential conditions of success. But success, however desirable, and however sweet when obtained, leads only to the material wellbeing of man. As to his spiritual well-being, the Jew, though busy with urgent work, will try to find some spare moments in which to turn his attention to “the three things upon which the world is based: Study of the Torah, Divine Service, and Charity” (Aboth i. 2).

Before the work of the day commences, and when it is finished, attention is paid to torah and abhodah. The Service, especially the Morning Service, contains various sections which are not prayers, but rather lessons for study. In addition to these, the Jew, according to his capacity or opportunity, should read the Bible, the Mishnah, and the Talmud. For those who have no opportunity at home, the Beth ha-midrash is open with its library. Synagogue and Beth hamidrash are the places of spiritual recreation where the Jew refreshes his mind, elevates his heart, and gathers new strength, courage, and hope for the battle of life.

Charity in its various branches, tsedakah and gemiluth chasadim, is a virtue practised by the wealthy and the poor alike. Any heart or house from which this [470]virtue is absent does not deserve to be called Jewish. Some Jews have charity-boxes in their houses, and whenever any member of the family has something to spare or is moved by a special impulse of charity, these boxes receive an addition to their contents. Others imitate the law of maaser (“tithe”), and set aside a tenth part of their earnings and profits for charitable purposes. Hospitality (םיחרוא תסנכה) is another method of charity, and it forms one of the ornaments of a true Jewish house. Although societies and public institutions do at present what was formerly considered to be the duty of the members of the community, individual hospitality has by no means become superfluous, and there is ample opportunity for its practice. Hospitality graces especially the lady of the house; it is her duty to provide for the comfort of the guests, and to act according to the rule, “Let the poor be the children of thy house” (Aboth i. 5).

This is one of the privileges possessed by women. According to the principle of division of labour, woman rules supreme in the house: “The King’s daughter is all glorious within” (Ps. xlv. 14); whilst man is more in contact with the outer world, devotes himself to labour, trade, or profession in order to provide the necessities of life for those who are dependent upon him. There are, however, many exceptions to the rule, and there is scarcely any trade or profession in which women have not been engaged. Women were not excluded even from the highest honours. The Jews had their prophetesses, and women were entrusted with judgeship and even with sovereignty There are instances of women distinguished by learning, experience, [471]wit, and especially by piety. Women of piety (תוינקדצ םישנ) were never wanting in Israel; and many a scholar owes the success he has attained in the field of learning to the piety of his wife, who willingly undertook her husband’s burdens and cares in trade and

business in order to facilitate his devotion to study. No sacrifice is too great for a true Jewish mother to have her children instructed in the Word of God, and nothing adds more to the happiness and pride of the mother than the progress her son has made in the knowledge of the Torah. “What is the great merit of women? They have the merit of making their children attend the school, and of encouraging their husbands to study the Talmud” (Babyl. Talm., Berachoth 17a).

The moral and the intellectual as well as the physical training of the children is in its earliest stages almost exclusively in the hands of the mother. If we add to this the responsibility for having the food prepared according to the requirements of the Dietary Laws, we easily understand the reason why Jewish women are exempt from various religious duties incumbent on the other sex. The rule is this: “Women are exempt from the fulfilment of all precepts which are restricted to a certain time” (Mishnah, Kiddushin i. 7), in order to prevent any collision between these and her principal and most important duties in the house. Thus it happens that there are Jewish women who faithfully cling to the inherited religion, and yet are rare visitors of the Synagogue. On week-days the Synagogue is only in exceptional cases attended by women. [472]

From this reason women are disqualified for forming the quorum (minyan) required for public worship (tefillah batsibbur). This and similar disqualifications are based on the principle of regard for women and their home-duties, and by no means on a belief in their inferiority. Passages in the Talmudical and Midrashic Literature which ascribe to women vanity, levity, and other shortcomings are outweighed by sayings which evidence a sense of high regard for the virtues and accomplishments of women. The following sentences are a few examples; “Woman has been endowed by the Creator with greater intelligence than man” (Babyl. Talm., Niddah 45b). “Who is rich? He who possesses a wife fair in her doings” (ibid., Shabbath

25b). “It was through the merit of pious women that the Israelites were redeemed from Egypt” (ibid., Sotah 11b).146 Modesty and reservedness (תועינצ) are the distinguishing virtues of Jewish women. The principle, “The daughter of the King is all glorious within,” was applied literally. In the fulfilment of her home-duties the daughter of Israel seeks her [473]happiness and her pride. It used to be opposed to the sense of propriety of Jewish ladies to speak, sing, or act in public.147 This תועינצ was the main cause of the preservation of the sanctity of the Jewish home and the purity of Jewish family life, a treasure and a blessing which ought to be well guarded.

The working days of the week are divided between labour and devotion. Three Services are attended daily either in the Synagogue or at home, and every meal is preceded and followed by prayer. Jewish women have, in addition to the Prayer-book, a small volume of supplications (תונחת) in the vernacular for every day, every season, and every occasion.

Mondays and Thursdays, on which days a Lesson from the Law is read during the Morning Service, are considered as special days for earnest devotion. There have been pious Jews who fasted the whole or part of these days.—Tuesday is looked upon as a favoured day, because it is distinguished in the account of the Creation (Gen. i. 10, 12) by a repetition of the phrase, “And God saw that it was good.” It is therefore called “the day with double ki-tobh (that it was good).” This circumstance may be the cause of the belief that it is not advisable to begin a new undertaking on Monday or Wednesday;148 preference should be [474]given to Tuesday. But this belief, although seemingly founded on a Biblical phrase, is contrary to Jewish principles, and is included in the prohibition, “Ye shall not observe times” (Lev. xix. 26), to declare a particular day as lucky or unlucky.

Friday is an important and busy day in a Jewish house. It is not only the circumstance that food is being prepared for two days149 that causes greater activity, but also the anticipated pleasure at the approach of a beloved guest. The same is the case when a Festival is near. Each Festival has its own particular wants and pleasures. In some houses the activity in preparing for Passover may be noticed a whole month before, although the actual clearing of the chamets is done in a very short time. Before Succoth all hands are busy with preparing and ornamenting the Tabernacle, and selecting esrog and lulabh. It is genuine religious enthusiasm150 in the fulfilment of Divine duties that inspires this kind of activity, and gives to the house a peculiarly Jewish tone and Jewish atmosphere. We feel in it “the season of our joy” before and during the Three Festivals, and “the season of solemnity and earnest reflection” during the penitential days; grief when the 9th of Ab approaches, [475]and hilarity when Purim is near. Twice a year we are invited by law and custom to give ourselves up to gladness and merriment: on Simchath-torah and on Purim. Although even a certain excess of mirth is considered lawful on the latter occasion, there are but very few that indulge in this license.

All the seasons of rejoicing are also occasions for mitsvoth—charity, and for strengthening the bond of love between husband and wife, between parents and children, and the bond of friendship between man and man. Every erebh shabbath and erebh yom-tobh afford the opportunity of giving challah, 151 kindling Sabbath or Festival lights,152 and inviting strangers153 (םיחרוא תסנכה) to our meals. On Sabbaths and Festivals children, even when grown up, come to their parents and ask for their blessing.154 Before Kiddush the husband chants the section of Prov. xxxi. beginning ליח תשא, in praise of a good wife. The Shabbath shalom or Good shabbath, Shabhua tobh or Good woch, Good yom tobh, and similar salutations, remind us that we ought to have only good wishes for each other. Sabbath and

Festivals afford suitable occasions for home-devotion, in which all the members of the family, males and females, should take part. The meals are preceded and followed by the usual berachoth, but it [476]is customary to add extra psalms and hymns (zemiroth) in honour of the day, and those who are gifted should add to these, or even substitute for them, compositions of their own in any language they like in gloriam Dei. A second kind of home-devotion which ought not to be neglected, but should rather be revived where it is neglected, is the reading of the Scriptures. On Friday evening the pious Jew reads the Sidra twice in the original and once in the Targum; but all should at least read Sidra and Haphtarah in the vernacular.

The moon by its gradual increase in light from its minimum to fullmoon, and the subsequent decrease from full-moon to its minimum, has in Agadic and Midrashic Literature frequently served as a symbol of the history of Israel, of his rise and his fall. The last day of the decline, the eve of New-moon, is kept by some as a special day of prayer and fasting,155 while the first day of the rise, New-moon, is distinguished by Hallel and Musaph. If people, as a symbol of happiness (בוט ןמיס), prefer the middle of the month for marriage, their choice is harmless; but if they hold that season as more lucky than the rest of the month, they are guilty of superstition. As at the sight of other natural phenomena, so also has a benediction been fixed on observing the reappearance of the moon in the beginning of the month. For the above-mentioned reason, importance is attached to this berachah, and prayers are added for the redemption of Israel. The berachah, which is generally recited in the open air, is the chief element in the ceremony; the additional prayers and reflections are non-essential. [477]

In the foregoing, Jewish Life has been described as it appears at the various seasons of the year; in the following, it will be given as it appears at the various periods of man’s existence.

The first important moment is, of course, the moment of birth. The father, friends, and relatives are filled with anxiety for the life of both mother and child. Prayers are daily offered up for the safety and recovery of the patient and the well-being of the child. The Twentieth Psalm is sometimes written on a tablet placed in the room where the confinement takes place, probably as a reminder or an invitation for visitors to pray to the Almighty; in this sense the custom is to be commended; but if the tablet is filled with meaningless signs, letters, and words, and is used merely as a charm, the custom should be discontinued, being a superstitious practice. In some parts it has been the custom that during the week preceding the Berith-milah friends visited the house to pray there for the well-being of the child, and boys recited there Biblical passages containing blessings, such as Gen. xlviii. 16.156 The night before the berith was spent in reading Bible and Talmud, so that the child might from the beginning breathe, as it were, the atmosphere of torah. 157 [478]

On the eighth day the male child is initiated into the covenant of Abraham (Lev. xii. 3). Circumcision is one of “those mitsvoth which the Israelites in times of religious persecution carried out notwithstanding imminent danger to life.” The performance of this Divine precept is therefore made the occasion of much rejoicing. In some congregations the operation, as a sacred act, takes place in the Synagogue after the Morning Service; in others the privacy of the home is preferred. In ancient days mothers circumcised their sons, but now the operation is only entrusted to a person who has been duly trained, and has received from competent judges a certificate of his qualification for the functions of a mohel 158 Although, according to the Law, any person, otherwise capable of doing it, may do the mitsvah, preference is given, and ought to be given, to a person of genuine piety and of true enthusiasm for our holy Religion, who performs the act in gloriam Dei. Not only the mohel, but all who assist in the act do a mitsvah, and the meal which is prepared for the

occasion is a הוצמ תדועס (a meal involving a religious act).159 Immediately after the operation a name is given to the child.160 [479]

The next important moment in a boy’s life is the “Redemption” (ןוידפ ןבה) in case of the first-born male child (Exod. xiii. 13, 15), which act is likewise made the occasion of a הוצמ תדועס. A cohen (descendant of Aaron) receives the redemption-money to the amount of five shekels (or 15s.), according to Num. xviii. 16.161

In the case of a female child the naming generally takes place in the Synagogue on a Sabbath, when the father is called up to the Law. In many congregations this takes place when the mother has sufficiently recovered to attend again for the first time the Service in the Synagogue on Sabbath. Those who live at a great distance from the Synagogue pay the first visit to the place of worship on a weekday. A special Service has been arranged for the occasion.162

Great care is now taken by the parents for the physical well-being of the child, without entirely ignoring its moral and intellectual development. “At five years the child is fit to be taught Mikra, i.e., reading the Bible” (Aboth v. 21), so the Mishnah teaches. But long before this the child is taught to pray, and to repeat short Biblical passages or prayers in Hebrew. It must, of course, be borne in mind that children are not all alike, and that each child must be taught according to its own capacities and [480]strength. The knowledge must be imparted in such a manner that the child should seek it as a source of pleasure and happiness.

As to the subjects which are to be taught, there is no branch of general knowledge from which Jewish children are debarred by their Religion, nor is there any branch of knowledge that is more Jewish than the rest. Jewish children must learn like other children, as far as possible, that which is considered necessary and useful, as well as that which is conducive to the comfort and happiness of life. But

Religion, Scripture, and Hebrew must never be absent from the curriculum of studies of a Jewish child. The instruction in Religion need not occupy much time, for the best teaching of Religion is the good example set by the parents at home and the teacher in the school. The religious training of a child should begin early; the surroundings and associations must teach the child to act nobly, to speak purely, to think charitably, and to love our Religion. “Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old, he will not depart from it” (Prov. xxii. 6). Early practical training (ךונח) is also of great importance with regard to the observance of religious precepts. Children should be accustomed to regard with reverence that which is holy, to honour Sabbath and Festivals, and to rejoice in doing what the Almighty has commanded. Twice a year we have special occasion for the fulfilment of this duty, viz., on Simchath-torah and on the Seder-evening.

In teaching our children Hebrew our aim must be to make them understand the holy language, to enable them to read the Word of God in the original, and to [481]pray to the Almighty in the language in which the Prophets and the Psalmists gave utterance to their inspirations, and in which our forefathers addressed the Supreme Being in the Temple.

A special ceremony used to introduce the child into the study of the Bible in the original.163 Teacher and pupil went to the Synagogue, took a sepher from the Hechal, and the pupil was made to read the first lesson from the sepher. This and similar ceremonies were intended as a means of impressing on the pupil the great importance of studying the Word of God in the original language. After having acquired a sound knowledge of the Bible, the study of other branches of Hebrew literature, of Talmudical and Rabbinical works, is approached.

As a rule, boys devote more time to Hebrew studies than girls, only because girls are considered physically more delicate and not capable of doing so much work as boys. Girls are by no means excluded from acquiring a sound Hebrew knowledge; on the contrary, every encouragement should be given to them, if they are inclined to study Hebrew beyond the first elements.164

The boy when thirteen years old is bar-mitsvah (lit., “a son of the commandment”), bound to obey the Law, and responsible for his deeds. On the Sabbath following [482]his thirteenth birthday the boy is called up to the Law; he reads the whole of the Sidra or a section of it, and declares in the blessings which precede and follow the lesson his belief in the Divine origin of the Torah, and his gratitude to God for having given us the Law.165

The school-years come gradually to a close, and the practical preparation for life begins. A vocation has to be determined upon. From a moral and religious point of view all kinds of trade, business, and profession are equal. They are honourable or base according as they are carried on in an honourable manner or not. Whatever course is chosen, the moral and religious training must continue with unabated energy. When the school-years are over, when the youth is no longer under the control of the master, and is sometimes left even without the control of the parents, he is exposed to various kinds of temptation, especially through the influence of bad society. The vices against which the youth must guard himself most at this period of life are sensuality, excessive desire for pleasure, gambling, and dishonesty, which bring about his moral, social, and physical ruin. Self-control, acquired through continued religious training, is the best safeguard against these dangers. It is therefore advisable that those who have left the school should continue attending some religious class, or otherwise devote part of their free time to Talmud-torah, to the study of the Torah, and of works relating to it.

“At the age of eighteen years one is fit for marriage” (Aboth, ibid.) is an ancient dictum, but which [483]could never have been meant as an absolute law. For there are other qualifications equally important, and even more essential than age. Maimonides (Mishneh-torah, Hil. Deoth v. 11) says: “Man should first secure a living, then prepare a residence, and after that seek a wife. But fools act otherwise: they marry first, then look out for a house, and at last think of the means of obtaining a livelihood.” (Comp. Deut. xx. 5–7 and xxviii. 30.)

Marriage is called in the Bible “a divine covenant” (Prov. ii. 17), or “the covenant of God.” God is, as it were, made witness of the covenant; in His presence the assurances of mutual love and the promises of mutual fidelity are given by husband and wife (Mal. ii. 14). To break this covenant is therefore not only an offence of the one against the other, but an offence against God.—In addition to this religious basis of marriage, conditions of a more material nature were agreed upon. The maiden has been long of use in the house of her parents, and he who sought the privilege of taking her to his house and making her his wife had to give to the parents “dowry and gift” (ןתמו רהמ, Gen. xxxiv. 12). Later on, in the time of the Mishnah, all that the husband promised to his wife was made the subject of a written document (הבותכ), signed by two witnesses. In this document he guarantees to her 200 zus (or half the sum if she is a widow), the value of her outfit and dowry (in Hebrew אינודנ), and a certain amount added to the afore-mentioned obligatory sum (הבותכ תפסות). He further promises to honour her, work for her, maintain her, and honestly provide her with everything necessary for her comfort. [484]

The marriage was preceded by the betrothal (ןיסוריא or ןישודיק), the solemn promise on his part to take her after a fixed time to his house as his wife, and on her part to consider herself as his wife and to prepare herself for the marriage. Legally she was already his wife, and infidelity was visited with capital punishment. The interval

between the betrothal and marriage used to be twelve months; at present the two events are united in the marriage ceremony, and are only separated from each other by an address or by the reading of the kethubhah. That which is now called betrothal or engagement is merely a preliminary settlement of the conditions of the marriage (םיאנת “conditions”). The conditions used to be written down, including a fine (סנק) for breach of promise; the agreement used to be followed by the breaking of a glass166 and by a feast.

The actual betrothal takes place on the wedding-day, and consists mainly of the following significant words addressed by the bridegroom to his bride: לארשיו

“Behold, thou art consecrated (betrothed) to me by this ring according to the Law of Moses and of Israel.” While saying this he places a gold ring167 on the second finger of the [485]right hand. This act is preceded by a berachah over wine, read by the celebrant while holding a cup of wine in his hand, and the birchath erusin (“blessing of betrothal”), in which God is praised for the institution of Marriage. Bride and bridegroom, who during the ceremony stand under a canopy (הפוח), taste of the wine.

The canopy or chuppah168 represents symbolically the future home of the married couple, which they have to guard as a sanctuary, and to render inaccessible to evil deeds, words, and thoughts that would pollute it. The top of the canopy, which is formed of a curtain (תכרפ) of the Hechal, or of a talith, expresses the idea of sanctity.

After the birchath erusin the bridegroom makes the solemn declaration169 mentioned above: “Behold, thou art consecrated (betrothed) unto me by this ring according to the Law of Moses and of Israel,”170 whereupon the kethubhah is read in Aramaic171 or in English, [486]and an address is sometimes given. Then follow the ןיאושנ תוכרב (“Blessings of Marriage”), called also after their number

תוכרב עבש “Seven Blessings.”172 The ceremony concludes with the breaking of a glass and the mutual congratulations of friends and relatives, expressed in the words Mazzal-tobh (בוט לזמ “Good luck”).173

A banquet (ןיאושינ תדועס) follows, which is a הוצמ תדועס. It is introduced by the usual berachah (איצומה), and followed by Grace and the “Seven Blessings.”

The following are a few of the various customs connected with a Jewish marriage without being essential elements of the marriage ceremony:—

(1.) On the Sabbath previous to the wedding-day the bridegroom, his father, and the father of the bride are called up to the Law, and offerings are made (mi shebberach) in honour of the bride and the bridegroom. In some congregations Gen. xxiv. is read after the Service, on the morning of the wedding-day.

(2.) Bride and bridegroom enter upon a new life; the wedding-day is to them a day of rejoicing, but also a day of great solemnity. It is kept as a day of earnest reflections, of prayer and fasting, till after [487]the ceremony, when the fast is broken and the rejoicing begins. The bridegroom adds in the Minchah amidah the Confession (יודו) of the Day of Atonement.

(3.) The good wishes of friends and relatives are variously expressed. Rice, wheat, or similar things are thrown over the bride and the bridegroom as a symbol of abundance and fruitfulness.

(4.) The feast is accompanied by speeches in praise of the bride and bridegroom; it was considered a special merit to speak on such an occasion (ילימ אלולהד ארגא, Babyl. Talm., Berachoth 6b). The bridegroom used to give a discourse (השרד) on some Talmudical

theme, if he was able to do so. He received presents for it (derashah-presents).

(5.) In the time of the Bible and the Talmud the feasting lasted seven days.—The first day after the wedding used to be distinguished by a fish dinner (םיגד תדועס), in allusion to Gen. xlviii. 16.

In spite of all blessings and good wishes the marriage sometimes proves a failure, husband and wife being a source of trouble and misery the one to the other, instead of being the cause of each other’s happiness. In such a case a divorce may take place, and man and wife separate from each other. Divorce is permitted (Deut. xxiv. 1–4), but not encouraged; it is an evil, but the lesser of two evils. A written document was required (תותירכ רפס, טג), and later legislation made the writing and the delivery of the document difficult and protracted, in order to facilitate attempts at reconciliation; the fulfilment of the conditions agreed upon in the kethubhah also tended to [488]render divorce a rare event. The number of cases of divorce among the Jews is therefore comparatively smaller than among other denominations, but still unfortunately far too large, owing to want of foresight and reflection in the choice of a companion for life.

There is a kind of obligatory marriage (םובי) and or obligatory divorce (הצילח), viz., with regard to the widow of a deceased brother who has died without issue (Deut. xxv. 5–10). Since the abolition of polygamy174 by Rabbenu Gershom (eleventh century) the obligatory marriage has almost disappeared, and the obligatory divorce (הצילח) must take place before the widow can marry again.175

We acknowledge the principle laid down in the Talmud, “The law of the country is binding upon us” (אניד אתוכלמד אניד), but only in so far as our civil relations are concerned. With regard to religious questions our own religious code must be obeyed. Marriage laws

include two elements—civil relations and religious duties. As regards the former, we abide by the decisions of the civil courts of the country. We must, therefore, not solemnise a marriage which the law of the country would not recognise; we must not religiously dissolve a marriage by טג, unless the civil courts of law have already decreed the divorce. On the other hand, we must not content ourselves [489]with civil marriage or civil divorce; religiously, neither civil marriage nor civil divorce can be recognised unless supplemented by marriage or divorce according to religious forms. Furthermore, marriages allowed by the civil law, but prohibited by our religious law

e.g., mixed marriages; that is, marriages between Jews and nonJews—cannot be recognised before the tribunal of our Religion; such alliances are sinful, and the issue of such alliances must be treated as illegitimate. Those who love their Religion and have the well-being of Judaism at heart will do their utmost to prevent the increase of mixed marriages.

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die” (Eccles. iii. 1, 2).

Life is a precious gift the Creator has given us; while there is breath in our nostrils we thank Him for it, we pray to Him for its prolongation, do everything in our power to preserve it, and consider its wilful destruction a criminal act. But notwithstanding all this “there is a time to die.” Life and death are equally mysteries to us; we trust in the mercy of Him who has ordained life and death, that both are for our good. Death is, therefore, not to be regarded with dread and horror; it is the transition to another state of life, the real nature of which is unknown to us. But it is our belief that the future life (אבה םלועה) is infinitely superior to the present life (הזה םלועה); hence the saying in the Midrash that the words “exceedingly good” (Gen. i. 31) applied to death. The only fear of death that can reasonably be justified is the fear of departing from this life before we have completed our task, before we have sufficiently [490]strengthened “the breaches of the

house” caused by our own dereliction of duty. Our Sages advise, “Return one day before thy death” (Aboth ii. 15); that is, every day, the day of death being concealed from our knowledge. In this manner we constantly prepare ourselves for death without curtailing our enjoyment of life. “Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth; and let thy heart cheer thee in the days of thy youth, and walk in the ways of thine heart, and in the sight of thine eyes: but know thou, that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment. Therefore remove sorrow from thy heart, and put away evil from thy flesh: for childhood and youth are vanity” (Eccles. xi. 9, 10). When passion overcomes us and evil inclinations invite us to sin, we are told by our Sages to remember the day of death, which may suddenly surprise us before we have been able by repentance to purify ourselves from our transgressions (Babyl. Talm., Berachoth 5a).

When death approaches, and announces itself through man’s illness, we do everything that human knowledge and skill can suggest to preserve and prolong the earthly life with which God has endowed us; in addition, the patient himself and his friends invoke the mercy of God for his recovery 176 Even when death appears invincible, when “the edge of the sword touches already man’s neck, we do not relinquish our hope in God’s mercy, and continue to pray to the All-merciful.” The patient is asked to [491]prepare himself for the solemn moment, although it may in reality be as yet far off.177 The preparation consists of prayer, meditation, confession of sin, repentance, and of the profession of our Creed, especially of the Unity of God, in the words, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.”178 To visit the sick, to comfort them by kind words and deeds, to pray with and for the patient, are acts included in the duty of “visiting the sick” (םילוה רוקב).179 In the moment of death those present testify their faith in God by proclaiming the Dominion, the Omnipotence, and the Unity of God in the same way in which we make this declaration at the conclusion of the Day of Atonement.

Although Prayer-books contain certain forms of prayer for this purpose, the patient and those present should rather follow the impulse of their heart, and commune with the Almighty in any form their heart suggests.

When life has come to an end friends and relatives give free expression to their grief;180 to check it by comforting words at this moment is useless (Aboth iv. 18). The mourners,181 father, mother, son, daughter, brother, and sister, have now to direct all their attention [492]to the deceased relative, in order that nothing be neglected in the last honours shown to him; they are therefore free from all other religious obligations till after the burial. In Palestine and neighbouring countries, where, in consequence of the higher temperature, decomposition of the body begins soon after death, the burial takes place on the same day.182 In colder climates two or three days elapse between death and burial. The mourners abstain during the interval from wine and meat.

Every act of piety in honour of the deceased is a meritorious religious act, a mitsvah, an act of kindness and truth (תמאו דסח), and in every congregation there exists a society, called אשירק ארבח “holy society,” whose members devote themselves to the fulfilment of these pious duties.

According to the principle that death equalises all, that “the small and great are there” (Job iii. 19), the greatest simplicity and equality is observed in all matters connected with the obsequies183 of the dead. Friends and relatives follow to the burial-ground; the תמה תיולה, or attending the dead to their last resting-place,184 [493]is one of those mitsvoth “the fruits of which a man enjoys in this world, while the stock remains for him for the world to come.”

Burying the dead is a very old custom, to which the Jews adhered firmly at all ages. The custom of the Greeks, who burnt their dead,

found no advocates among the Jews. In the Written and the Oral Law only the burying of the dead is mentioned. To leave a human body unburied and unattended was considered by Jews, as by other nations, an insult to the deceased person, and whoever found such a body was bound to take charge of it and to effect its burial.185

In the Burial Service we acknowledge the justice of God, and resign ourselves to the Will of the Almighty (ןידה קודצ). When the burial is over our attention is directed to the living; words of comfort are addressed to the mourners186 who return home and keep העבש “seven days of mourning.” A certain degree of mourning is then continued till the end of [494]the year by the children of the deceased, and till the end of the month (םישלש “thirty days”) by other relatives.187

Our regard for the deceased (יבכשד ארקי) and our sympathies with the mourners (ייחד ארקי) are expressed in different ways.

The funeral oration (דפסה) occasionally spoken at the grave, or in the house of mourning, or in the Synagogue, generally combines both elements; it contains a eulogy upon the deceased and words of sympathy and exhortation for the living.

The special prayers offered up on such occasions likewise include these two elements: petitions for the well-being of the soul of the deceased, that it may find Divine mercy when appearing before the Supreme Judge, and petitions for the comfort and relief of the mourners. The Kaddish of the Mourners, however, does not contain such prayers, but merely expresses their resignation to the Will of the Almighty, their conviction that He is the only Being that is to be worshipped, and that He alone will be worshipped by all mankind in the days of Messiah, and their wish that the arrival of those days may be hastened.

There are, besides, the following customs, the object [495]of which is to express our regard for the memory of the deceased: (1.) A tombstone (הבצמ) is set up in front of or over the grave with the name of the deceased, the date of his death, and such words of praise as are dictated by the love and the esteem in which the deceased was held by the mourners. (2.) A lamp is kept burning188 during the week, or the month, or the year of mourning, and on the anniversary of the day of death (Jahrzeit). (3.) By observing the anniversary of the death as a day devoted to earnest reflection, and to meditation on the merits and virtues of the deceased; we keep away from amusements, and say Kaddish in the course of the Services of the day. Some observe the anniversary as a fast-day. (4.) By doing some mitsvah189 in commemoration of the deceased. (5.) By regarding with respect and piety the wishes of the departed relative or friend, especially those uttered when death was approaching. Our Sages teach: “It is our duty to fulfil the wishes of the departed.”190 The absence of this inner respect and piety makes all the outward signs of mourning, however conscientiously observed, valueless and illusory. [496]