Acute Stroke Management in the First 24 Hours: A Practical Guide for

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/acute-stroke-management-in-the-first-24-hours-a-pra ctical-guide-for-clinicians-maxim-mokin/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

LaTeX in 24 Hours A Practical Guide for Scientific Writing Dilip Datta

https://textbookfull.com/product/latex-in-24-hours-a-practicalguide-for-scientific-writing-dilip-datta/

Acute Stroke Care James Grotta

https://textbookfull.com/product/acute-stroke-care-james-grotta/

Treating Stalking: A Practical Guide for Clinicians 1st Edition Troy Mcewan

https://textbookfull.com/product/treating-stalking-a-practicalguide-for-clinicians-1st-edition-troy-mcewan/

The Code Stroke Handbook: Approach to the Acute Stroke Patient Andrew Micieli

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-code-stroke-handbookapproach-to-the-acute-stroke-patient-andrew-micieli/

Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in the Younger Active Patient An Evidence Based Practical Guide for Clinicians 1st Edition David A. Parker (Eds.)

https://textbookfull.com/product/management-of-kneeosteoarthritis-in-the-younger-active-patient-an-evidence-basedpractical-guide-for-clinicians-1st-edition-david-a-parker-eds/

Warlow's Stroke: Practical Management Fourth Edition

Caprio

https://textbookfull.com/product/warlows-stroke-practicalmanagement-fourth-edition-caprio/

Management of Anemia A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians 1st Edition Robert Provenzano

https://textbookfull.com/product/management-of-anemia-acomprehensive-guide-for-clinicians-1st-edition-robert-provenzano/

Acute Stroke Care 3rd Edition James Grotta

https://textbookfull.com/product/acute-stroke-care-3rd-editionjames-grotta/

Human Ring Chromosomes: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Families 2024th Edition Peining Li

https://textbookfull.com/product/human-ring-chromosomes-apractical-guide-for-clinicians-and-families-2024th-editionpeining-li/

APracticalGuideforClinicians

EDITEDBY MAXIMMOKIN,MD,PHD

ASSISTANTPROFESSOROFNEUROLOGYANDNEUROSURGERYUNIVERSITYOFSOUTH FLORIDAMEDICALDIRECTOROFNEUROINTERVENTIONALSERVICESTAMPAGENERAL HOSPITALTAMPA,FL

EDWARDC JAUCH,MD,MS

PROFESSOR,CHAIR,DEPARTMENTOFEMERGENCYMEDICINEPROFESSOR,DEPARTMENTOF NEUROLOGYMEDICALUNIVERSITYOFSOUTHCAROLINACHARLESTON,SCADJUNCT

PROFESSOR,DEPARTMENTOFBIOENGINEERINGCLEMSONUNIVERSITYCLEMSON,SC

ITALOLINFANTE,MD,FAHA

MEDICALDIRECTOROFINTERVENTIONALNEURORADIOLOGYANDENDOVASCULAR NEUROSURGERYMIAMICARDIACANDVASCULARINSTITUTEANDBAPTISTNEUROSCIENCE INSTITUTECLINICALPROFESSOROFRADIOLOGYANDNEUROSCIENCEHERBERTWERTHEIM COLLEGEOFMEDICINEFLORIDAINTERNATIONALUNIVERSITYMIAMI,FL ADNANSIDDIQUI,MD,PHD,FAHA

VICE-CHAIRMANANDPROFESSOROFNEUROSURGERYANDRADIOLOGYDIRECTOROF NEUROENDOVASCULARFELLOWSHIPPROGRAMJACOBSSCHOOLOFMEDICINEAND BIOMEDICALSCIENCESTHESTATEUNIVERSITYOFNEWYORKATBUFFALODIRECTOROF THENEUROSURGICALSTROKESERVICEKALEIDAHEALTHBUFFALO,NY ELADLEVY,MD,MBA,FACS,FAHA

CHAIRMANOFNEUROLOGICALSURGERYPROFESSOROFNEUROSURGERYANDRADIOLOGY JACOBSSCHOOLOFMEDICINEANDBIOMEDICALSCIENCESTHESTATEUNIVERSITYOFNEW YORKATBUFFALOMEDICALDIRECTOROFNEUROENDOVASCULARSERVICESGATES VASCULARINSTITUTEBUFFALO,NY

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide OxfordisaregisteredtrademarkofOxfordUniversityPressintheUKandcertainothercountries

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress

198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

©OxfordUniversityPress2018

Allrightsreserved Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans, withoutthepriorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermittedbylaw,bylicense,orundertermsagreedwiththe appropriatereproductionrightsorganization InquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeoftheaboveshouldbesenttotheRights Department,OxfordUniversityPress,attheaddressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherformandyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names:Mokin,Maxim,editor |Jauch,EdwardC,editor | Linfante,Italo,editor |Siddiqui,Adnan,editor |Levy,Elad,editor

Title:Acutestrokemanagementinthefirst24hours:apracticalguideforclinicians/ editedbyMaximMokin,EdwardC Jauch,ItaloLinfante,AdnanSiddiqui,EladLevy

Description:Oxford;NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress,[2018]| Includesbibliographicalreferences

Identifiers:LCCN2017054218|ISBN9780190856519(pbk:alk paper)|ISBN9780190856533(epub)

Subjects:|MESH:Stroke–diagnosis|Stroke–therapy|CriticalCare–methods| EmergencyTreatment–methods

Classification:LCCRC3885|NLMWL356|DDC6168/1–dc23 LCrecordavailableathttps://lccnlocgov/2017054218

Thismaterialisnotintendedtobe,andshouldnotbeconsidered,asubstituteformedicalorotherprofessionaladvice Treatmentforthe conditionsdescribedinthismaterialishighlydependentontheindividualcircumstances And,whilethismaterialisdesignedtoofferaccurate informationwithrespecttothesubjectmattercoveredandtobecurrentasofthetimeitwaswritten,researchandknowledgeaboutmedical andhealthissuesisconstantlyevolvinganddoseschedulesformedicationsarebeingrevisedcontinually,withnewsideeffectsrecognizedand accountedforregularly Readersmustthereforealwayschecktheproductinformationandclinicalprocedureswiththemostup-to-date publishedproductinformationanddatasheetsprovidedbythemanufacturersandthemostrecentcodesofconductandsafetyregulation The publisherandtheauthorsmakenorepresentationsorwarrantiestoreaders,expressorimplied,astotheaccuracyorcompletenessofthis material Withoutlimitingtheforegoing,thepublisherandtheauthorsmakenorepresentationsorwarrantiesastotheaccuracyorefficacyof thedrugdosagesmentionedinthematerial Theauthorsandthepublisherdonotaccept,andexpresslydisclaim,anyresponsibilityforany liability,lossorriskthatmaybeclaimedorincurredasaconsequenceoftheuseand/orapplicationofanyofthecontentsofthismaterial.

Foreword

Preface

Contributors

1. BasicClinicalSyndromesandDefinitions

AparnaPendurthiandMaximMokin

2. StrokeSystemsofCare

CaseyFrey,LauraBishop,StaceyQ Wolfe,andKyleM Fargen

3. PrehospitalTriageofStroke:ClinicalEvaluation

VeraSharashidze,ClaraBarreira,DiogoHauseen,andRaulG Nogueira

4. PrehospitalAssessmentofStroke:MobileStrokeUnits

AndrewBlakeBuletko,JasonMathew,TapanThacker,LilaSheikhi,AndrewRussman,andM Shazam Hussain

5 EvaluationofStrokeintheEmergencyDepartment

RobertSawyerandEdwardC.Jauch

6 ImagingofAcuteStroke

MaximMokin

7. TelemedicineforEvaluationofStrokePatients

KaustubhLimayeandLawrenceR Wechsler

8. IntravenousThrombolysisinAcuteIschemicStroke

WaldoR Guerrero,EdgarA Samaniego,andSantiagoOrtega-Gutierrez

9. EndovascularTreatmentofStroke

MandyJ BinningandDanielR Felbaum

10. CareofStrokePatientsPostIntravenousAlteplaseandEndovascularThrombectomy

ViolizaInoaandLucasElijovich

11 In-HospitalStroke

NoellaJ CypressWestandMaximMokin

12 MedicalManagementofIschemicStroke

MaximMokinandJuanRamos-Canseco

13 MedicalManagementofHemorrhagicStroke

ShashankShekhar,ShreyasGangadhara,andRebeccaSugg

14 SurgicalTreatmentofHemorrhagicStroke

VladimirLjubimov,TravisDailey,andSivieroAgazzi

15. CerebralVenousThrombosis

JuanRamos-CansecoandMaximMokin

Index

TUDORG JOVIN■

Thedreamofbeingabletoreverseastrokebyopeningtheoccludedcerebralarteryfromwithinstartedinthe earlydaysofneuroendovasculartherapiespioneeredbytheneurologistEgazMonizandhasbecomerealityin the era of modern mechanical thrombectomy. After years of stagnation that followed publication of the landmarkNINDSivt-PAtrialin1995,whichledtotheimplementationofintravenoust-PAasthestandard and only proven treatment for acute ischemic stroke, the past years have witnessed disruptive changes in the delivery of acute stroke care. Remarkable technological advances, spearheaded by physicians and industry along with a maturation process on the part of stroke care providers with regards to patient selection, workflow, and peri- and intra-procedural care culminated in no less than eight completed and strongly positive randomized trials of thrombectomy for acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion. These studies, which together have enrolled over 2,000 patients, have not only demonstrated a treatment effect only a handfulofotherproceduralbasedtherapiescanclaiminmedicinebuthavealsowidenedthetherapeutictime windowtoapreviouslyunimaginable24hours.Highlyeffectiveastheseinterventionsare,favorableoutcomes are still observed in only about half of the patients treated Furthermore, a substantial proportion of patients potentially eligible for this procedure remain untreated Much work remains ahead to establish more effective approachesthatwillnotonlyleadtomorepatientstreatedbutalsoresultinhigherratesoffavorableoutcomes

Notunlikeischemicstrokepriortotherecentdevelopments,intracerebralhemorrhagehasbeenplaguedby decades of therapeutic nihilism And while this area of vascular neuroscience has not yet achieved a breakthrough similar to that observed with ischemic stroke, there are exciting new minimally invasive approachesthatholdgreatpromiseforthefuture

Consideringtheexquisitetime-sensitivebenefitofthrombectomy,dramaticparadigmshiftimplementation requiredatbothindividualandsystemlevelsforthecareofpatientswithacutestrokerepresentsaformidable challenge Amongthemanyinterventionsnecessaryforaneffectivechangeinthedeliveryofacutestrokecare, healthcareprovidereducationisofparamountimportance

From that standpoint, Acute Stroke Management in the First 24 Hours is a much needed and timely contribution that fills a real void in knowledge as it represents a comprehensive overview of most aspects related to the care of the acute ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke patient Furthermore, as a novel and refreshing approach, it follows the logical progression of care from evaluation and management in the prehospitalsettingtothein-hospitalhyperacuteintervention(whenindicated)andthroughtothecriticalstageof early post-admission care This practical yet well-grounded in science material represents the result of a collaborative work by a multispecialty group of widely acknowledged experts in the field of cerebrovascular diseases Given the complexity of acute stroke care and the fact that knowledge included and easily accessible in this book can be life (or brain) saving, every physician and healthcare provider involved in the care of patients with acute stroke could benefit from adding a copy of AcuteStrokeManagementintheFirst24Hours totheirlibrary

TudorG Jovin,MD

ProfessorofNeurologyandNeurosurgery Director,UniversityofPittsburghMedicalCenter(UPMC)StrokeInstitute Director,UPMCCenterforNeuroendovascularTherapy

Pittsburgh,PA

The last two decades have ushered a dramatic evolution in management of acute stroke patients through promising advances in medical, endovascular, and open surgical procedures Physicians who are at the vanguardoftreatingtheacutestrokepatientarefacedwitheverincreasingchallengesandraceagainsttimeto achievethebestpossibleclinicaloutcomes.Navigatingthecomplexitiesofthestrokesystemofcarestartswith time-sensitive identification of the acute stroke patient in the prehospital setting, followed by appropriate hospitaltriage,andcontinuesinhospitalwithselectionofasuitableandindividualizedtreatment

The treatment of acute ischemic stroke has become considerably more complex now that endovascular thrombectomyhasproveditshighsafetyandefficacyastreatmentoption Whilesomepatientsarecandidates for only one particular type of revascularization therapy (either intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy),othersmaybenefitfromboththerapiescombined;makingproperpatientselectionandtriage more challenging Randomized trials focusing on medical and surgical management of intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage have expanded our understanding of patients with cerebrovascular diseases Although promising, these results have further confounded clinical decision making for hemorrhagic stroke patients Furthermore, the evaluation and treatment protocols for acute stroke frequently exclude patients whoseclinicalpresentationdoesnotfallwithintheestablishedguidelines

Aware of these challenges, neurologists, neurosurgeons, interventionalists, and emergency medicine specialistswhotraditionallypracticewithinanarrowscopenowfindthemselvesassumingnewrolestoachieve optimal patient outcomes Clinician collaboration within a multidisciplinary team that includes first responders and hospital administration is vital to the establishment of stroke outreach programs and updated, progressive triage protocols Acute Stroke Management in the First 24 Hours is a practical, collaborative road map for a broad audience of health-care providers involved in the initial evaluation and management of acute strokepatients.Itbenefitsfromtheexperienceofitsauthorswhoexpertlyunderstandtheburgeoningneedof acooperativeapproachtoacutestroketreatment

SivieroAgazzi,MD,MBA,FCAS

Professor,CollegeofMedicineNeurosurgery Director,DivisionofCranialSurgery DepartmentofNeurosurgeryandBrainRepair UniversityofSouthFlorida Tampa,FL

ClaraBarreira,MD ClinicalResearchFellow DepartmentofNeurology EmoryUniversitySchoolofMedicine Atlanta,GA

MandyJ Binning,MD AssistantProfessor StrokeDirector DepartmentofNeurosurgery DrexelUniversity Philadelphia,PA

LauraBishop,MD AssistantProfessor,Neurology DepartmentofNeurology WakeForestUniversity Winston-Salem,NC

AndrewBlakeBuletko,MD VascularNeurologyFellow CerebrovascularCenter,NeurologicalInstitute ClevelandClinic Cleveland,OH

NoellaJ CypressWest,ARNP VascularNeurologyNursePractitioner TampaGeneralHospital Tampa,FL

TravisDailey,MD PGY-3Resident

CONTRIBUTORS

DepartmentofNeurosurgeryandBrainRepair UniversityofSouthFlorida

Tampa,FL

LucasElijovich,MD,FAHA AssociateProfessor

DepartmentsofNeurologyandNeurosurgery Semmes-MurpheyNeurologicInstitute UniversityofTennesseeHealthSciencesCenter Memphis,TN

KyleM.Fargen,MD,MPH AssistantProfessor,Neurosurgery DepartmentofNeurologicalSurgery

WakeForestUniversity Winston-Salem,NC

DanielR.Felbaum,MD DepartmentofNeurosurgery DrexelUniversity Philadelphia,PA

CaseyFrey,MS DepartmentofNeurologicalSurgery

WakeForestUniversity Winston-Salem,NC

ShreyasGangadhara,MD DepartmentofNeurology UniversityofMississippiMedicalCenter Jackson,MS

WaldoR Guerrero,MD NeuroendovascularSurgeryFellowAssociate DepartmentofNeurology,StrokeDivision UniversityofIowaCarverCollegeofMedicine

IowaCity,IA

DiogoHauseen,MD AssistantProfessor

GradyMemorialHospital EmoryUniversitySchoolofMedicine Atlanta,GA

M.ShazamHussain,MD

AssociateProfessor,ClevelandClinicLernerCollegeofMedicine

Director,CerebrovascularCenterNeurologicalInstitute

ClevelandClinic

Cleveland,OH

ViolizaInoa,MD

AssistantProfessor

DepartmentsofNeurologyandNeurosurgery

Semmes-MurpheyNeurologicInstitute

UniversityofTennesseeHealthSciencesCenter

Memphis,TN

KaustubhLimaye,MD

ClinicalAssistantProfessorofNeurology,CerebrovascularDiseases DepartmentofNeurology UniversityofIowaCarverCollegeofMedicine

IowaCity,IA

VladimirLjubimov,MD

PGY-2Resident

DepartmentofNeurosurgeryandBrainRepair UniversityofSouthFlorida

Tampa,FL

JasonMathew,DO

VascularNeurologyFellow

CerebrovascularCenter,NeurologicalInstitute

ClevelandClinic

Cleveland,OH

RaulG Nogueira,MD

Director,NeuroendovascularDivision

MarcusStroke&NeuroscienceCenter

GradyMemorialHospital

EmoryUniversitySchoolofMedicine

Atlanta,GA

SantiagoOrtega-Gutierrez,MD,MSC

ClinicalAssistantProfessor

DirectoroftheNeurointerventionalSurgeryinNeurology

AssociateProgramDirectoroftheNeuroendovascularSurgeryFellowshipProgram DepartmentofNeurology,StrokeDivision

UniversityofIowaCarverCollegeofMedicine

IowaCity,IA

AparnaPendurthi,MD Instructor

DepartmentofNeurology

UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter KansasCity,KS

JuanRamos-Canseco,MD

VascularNeurology

PalmBeachNeuroscienceInstitute WestPalmBeach,FL

AndrewRussman,DO

Head,ClevelandClinicStrokeProgram CerebrovascularCenter

NeurologicalInstitute ClevelandClinic Cleveland,OH

EdgarA Samaniego,MD

ClinicalAssistantProfessor

DepartmentofNeurologyStrokeDivision

UniversityofIowaCarverCollegeofMedicine

IowaCity,IA

RobertSawyer,MD AssociateProfessor

DepartmentofNeurology UniversityatBuffalo,theStateUniversityofNewYork NewYork,NY

VeraSharashidze,MD Resident

DepartmentofNeurology

EmoryUniversitySchoolofMedicine Atlanta,GA

LilaSheikhi,MD

VascularNeurologyFellow

CerebrovascularCenter

NeurologicalInstitute

ClevelandClinic Cleveland,OH

ShashankShekhar,MD,MSc

VascularNeurologyFellow DepartmentofNeurology

UniversityofMississippiMedicalCenter Jackson,MS

RebeccaSugg,MD,FAHA

AssociateProfessor,ViceChair,andDirector DepartmentofNeurology UniversityofMississippiMedicalCenter Jackson,MS

TapanThacker,MD

VascularNeurologyFellow

CerebrovascularCenter

NeurologicalInstitute

ClevelandClinic Cleveland,OH

LawrenceR.Wechsler,MD

HenryB.HigmanProfessorandChair DepartmentofNeurology

VicePresidentofTelemedicineServices PhysicianServicesDivision UniversityofPittsburghSchoolsoftheHealthSciences Pittsburgh,PA

StaceyQ.Wolfe,MD

ProgramDirectorandAssociateProfessor DepartmentofNeurologicalSurgery

WakeForestUniversity Winston-Salem,NC

BasicClinicalSyndromesandDefinitions

CONTENTS

Introduction

Classification

Transientischemicattack

Stroke

Ischemicstroke

Lacunarstrokesyndromes

Puremotorhemiparesis

Puresensorystroke

Sensorimotorstroke

Ataxichemiparesis

Dysarthria-clumsyhandsyndrome

Largevesselstrokesyndromes

Anteriorcirculationstrokes

Middlecerebralarterystroke

Anteriorcerebralarterystroke

Posteriorcirculationstrokes

Basilararterystroke

Posteriorcerebralarterystroke

Strokesyndromes mediumsizevessels

Anteriorchoroidalarterystroke

Superiorcerebellararterystroke

Anteriorinferiorcerebellararterystroke

Posteriorinferiorcerebellararterystroke

Anteriorspinalarterystroke

Embolicstroke

Hemorrhagicstroke

Clinicalcases

Case1.1 Transientischemicattack

Case12 MCAstroke

Case13 Topofthebasilararterystroke

References

1INTRODUCTION

Stroke remains the single leading cause of long-term care disability in the United States and the fifth leading cause of death, killing nearly 133,000 people a year 1 The goal for neurological evaluation in the Emergency Department (ED) is to appropriately route potential acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke patients toward medical intervention in the most expedient manner possible. Emergency medical services are the primary access point for stroke evaluations, with providers performing the initial diagnostic workup and care Patients aged 75 and over had the highest rate of emergency room visits from 2001 to 2011 for stroke and transient ischemicattacks(TIAs),withnearlya10%increaseinadmissions/transferfromEDsinthattime.2

Evenbeforeradiographicscans,quickandthoroughneurologicalevaluationscanestablishthelikelihoodof acute stroke syndromes and mobilize providers toward appropriate therapies This chapter focuses on familiarizing the reader with stroke subtypes and clinical manifestations associated with specific syndromes. Thisinformationcanassistinrapididentificationofcommonstrokepresentations

2CLASSIFICATION

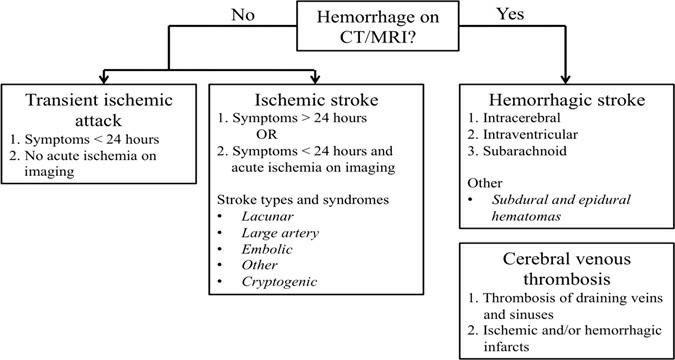

Acute neurologic episodes being evaluated in the emergent setting for stroke workup can be divided into broad categories based on duration of symptoms and findings from basic imaging. Box 1.1 and Figure 1.1 describethecommontypesofcerebralinfrarctionsthatarefreqeuntlyencounteredinanacutesetting

Box1.1

TYPESOFCEREBRALINFARCTIONSBASEDONCLINICALANDRADIOGRAPHICCHARACTERISTICS

Ischemicstroke

• Imagingorpathologicalevidenceofcerebral,retinal,orspinalcordfocalischemicinjuryinadefined vasculardistribution

• ORfocalischemicinjurybasedonsymptomslasting≥24hours

Silentinfarction

• Imaging(suchasMRIorCT)orpathologicalevidenceofCNSinfarctionwithoutacorresponding clinicaldeficit

TIA

• Transientepisodeofneurologicaldysfunction

• ANDnoacuteinfarctiononbrain,retinal,orspinalcordimaging

ICH

• Afocalcollectionofbloodwithinthebrainparenchyma

Intraventricularhemorrhage

• Atypeofintarcerebralhemorrhagewithbloodpresentintheventricularsystem

Subarachnoidhemorrhage

• Focalordiffusecollectionofbloodwithinthesubarachnoidspace

Subduralandepiduralhematomas

• Bleedingexternaltothebrainandsubarachnoidspace Mostlyasaresultoftraumabutcanbe spontaneous.

• Arenotconsideredstrokesbythe2013AmericanHeartAssociationstatement,giventhedifferences inmechanismsandpathology

Cerebralvenousthrombosis

• Ischemicinfarctionand/orhemorrhagecausedbythrombosisofdrainingveinsandvenoussinuses

Adaptedfromthe2013StatementforHealthcareProfessionalsfromtheAmericanHeartAssociation4

Figure11Typesofcerebralinfarctionsbasedonclinicalandradiographiccharacteristics

SOURCE:Adaptedfromthe2013StatementforHealthcareProfessionalsfromtheAmericanHeartAssociation

Question 1.1: How often does magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detect acute stroke in patients with transientepisodesofneurologicdysfunction?

Answer: It is critical that all patients with suspected TIAs receive a brain MRI Research shows that between 9% and 67% of patients fitting the clinical definition of TIAs have evidence of acute stroke on MRI

21Transientischemicattack

TIAs are episodes of focal neurologic dysfunction caused by disruption in cerebral blood flow without complete obstruction TIAs present with the same symptoms associated with stroke, such as acute onset hemibody weakness or numbness, aphasia (inability to speak), dysarthria (slurred speech), and visual deficits that correspond to specific vascular regions However, these events do not lead to permanent neuronal cell damageseenonradiographicimagingandtypicallylastlessthanonehour 3

In the past, before the widespread use of MRI, TIAs used to be defined as neurologic events lasting less than 24 hours The 24-hour mark was chosen arbitrarily, and studies subsequently proved that many of these

patientswouldhaveevidenceofacuteischemiadetectedwithMRIimaging ThemoderndefinitionofaTIA therefore includes both clinical and radiographic criteria A TIA is a transient episode of neurological dysfunctioncausedbyfocalbrain,spinalcord,orretinalischemia,withoutacuteinfarction(Case1.1).4,5

TIAs secondary to periods of interrupted blood flow do not cause persistent clinical impairment but are considered to be events that increase long-term stroke risk and, as such, require thorough evaluation These episodes contribute to between 200,000 and 500,000 neurologic evaluations in the United States yearly in the ED and outpatient setting.6 There are various potential underlying causes for transient flow reductions, includingatherosclerosisofintra-orextra-cranialarteries,cardioembolicsources,inflammationofthearteries, sympathomimeticdrugs,orhypercoaguableconditions.

As TIA symptoms often resolve prior to physician evaluation, the goals of assessment are to uncover any subtle,persistentneurologicaldeficitsandriskstratifyforfutureischemicevents Adequatehistoryandreview of previous medical records is vital, as alternate diagnoses, including focal seizures, arrythmia, or migraine headaches, can often be mistaken for TIAs. Initial diagnostic evaluation can be achieved by obtaining basic vitalsigns,includingbloodpressure,heartrateandrhythmevaluation,laboratoryworkup,andimaginginthe ED. Hypoglycemia, blood pressure abnormalities, electrolyte derangements, and cardiac and vestibular etiologies are all non-neurologic sources of transient mentation changes that can quickly be elucidated by providers

Once the likelihood of transient ischemia has been determined, further assessment can assist with estimationofshort-termstrokerisk.TheABCD2 score,firstintroducedin2007,hasaidedmedicalproviders with a numerical scale to assess benefits of hosptialization and further diagnostic workup Originally developed for outpatient evaluation of TIA, it has since been shown that as the ABCD2 score increases, the risk of subsequent stroke also increases across multiple settings.7,8 The score is based on various stroke risk factors including age, blood pressure values, clinical featues, duration, and pre-existing diabetes It is used to gaugetheriskofstrokewithin2,7,30,and90daysafteraTIAandhasbecomeamainstayofEDevaluations (Box1.2).9

Box1.2

ABCD2SCORETOPREDICTSTROKERISKAFTERATRANSIENTISCHEMICATTACKEPISODEANDITS RECOMMENDEDINTERPRETATIONBYTHEAMERICANHEARTASSOCIATION

ABCD2 scorecalculation(0–7points)

• Age≥60years=1point

• Bloodpressure≥140/90mmHgonfirstevaluation=1point

• Symptomsoffocalweaknessorspeechimpairmentlasting≥60minutes=2pointsOR

• Symptomsoffocalweaknessorspeechimpairmentlasting10–59minutes=1point

• Diabetesmellitus=1point

The2-dayriskofstroke

• 0%forscoreof0or1

• 13%forscore2or3,

• 4.1%forscore4or5

• 81%forscore6or7

Patientswitharecent(within72hoursofsymptomsoccurrence)TIAshouldbehospitalizedwhen

• Totalscore≥3

• ORtotalscoreis0–2butunabletocompetediagnosticworkupwithin2days

Adaptedfromthe2009StatementforHealthcareProfessionalsfromtheAmericanHeartAssociationonevaluationofTIAs5

For patients deemed low risk via the ABCD2 criteria (score 0–3), an outpatient workup including further vascular imaging, antithrombotic therapy, cardiac event monitoring, and statin therapy may be most appropriate; the details of such further management are discussed in subsequent chapters. For patients consideredhighrisk(ABCD2 score>3),hospitaladmissionmaybeadvisabletoexpeditesuchinterventions

22Stroke

Stroke, in comparison to TIAs, is an acute, persistent neurological deficit with associated central nervous system (CNS) injury from interrupted blood supply Brain injury associated with vascular deficiencies is often focalandlocalizestospecificcerebralregions,producingcharacteristicclinicaldeficits.SimilartoTIAs,acute strokecanpresentwithacuteweakness,numbness,andverbalorvisualdeficits;however,theimpairmentdoes not resolve and is usually present at the time of assessment by medical providers Physiologically, neuronal tissue undergoes irreversible damage and death in the absence of oxygen, with the average patient losing approximately120millionneuronseachhour(equivalentto3.6yearsofnormalaging).10

Nearly 800,000 people in the United States suffer strokes yearly, with three-fourths of these events being first-time occurrences. The majority of these represent ischemic strokes, which occur in the absence of blood flowtothecerebraltissue,andaccountfor85%ofallstrokes.Hemorrhagicstrokes,causedbyarterialleakage intobrainparenchyma,comprisetheremaining15%

Further clinical differentiation can be made into cortical versus subcortical infarcts, which broadly specify the location of the infarcted territory. As their name implies, cortical strokes affect regions of the cerebral cortexsuchasthefrontal,parietal,temporal,andoccipitallobes Corticalstrokesmaydisrupthighercognitive functioning, producing symptoms like aphasia (the inability to produce or express language), alexia (inability toread),agraphia(inabilitytowrite),andhemibodyneglect.Subcorticalstrokes,bycomparison,affectregions below the cortex, such as the internal capsule, thalamus, basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum Subcortical strokes do not classically affect higher cognitive functioning. While all subtypes of acute stroke are associated with permanent neuronal damage, the etiology and management vary significantly with respect to thrombolytic use, supportive parameters, medication recommendations, and need for neurosurgical evaluations.

3ISCHEMICSTROKE

Ischemicstrokeresultsfromobstructionwithinabloodvessel,prohibitingflowtoaportionoftheCNS This originates from atherosclerotic plaque buildup within the arteries, blood clot (thrombus) formed at the site of occlusion, or an embolism that travels from another portion of the circulatory system to distally occlude

cerebral vasculature Small vessel, or lacunarstrokes, are the most common type of ischemic stroke; they can occur from closing off small arteries that supply deep brain structures including the internal capsule, basal ganglia,thalamus,andparamedianregionsofthebrain.11 Theseareoftenconsideredtheend-organeffectsof systemic hypertension and atheromatous disease. Artery-to-arteryembolism refers to infarcts that arise from atherosclerotic lesions in proximal arteries that fragment and travel to distal vessels, occluding them Large artery thrombosis often occurs as atherosclerotic plaque builds up to create progressive stenosis, with final artery occlusion resulting from thrombosis of the narrowed lumen. Embolic material can originate from a variety of sources, including mural thrombi/platelet aggregates from extracranial vasculature, cardiac thrombus, or less frequently, calcific plaques and fat embolism.12,13 Determining the source of embolic materialoftenrequiresmultiplevascularimagingmodalities;however,despiteextensiveevaluationandtheuse of various techniques (discussed in future chapters), the sources of 17% of all presumed embolic strokes have notbeenidentified.14

Question12:Arelacunarstrokescommon?

Answer: Lacunar infarcts are common, accounting for 25–40% of all ischemic strokes Some studies indicatethatlacunarstrokeisthemostcommontypeofischemicstrokeingeneralpopulation

3.1Lacunarstrokesyndromes

Lacunar strokes are considered small (≤15 mm in diameter) subcortical strokes associated with the occlusion of a penetrating branch of one artery.11 These strokes are thought to occur from small vessel disease, likely related to end-organ effects of systemic hypertension, lipohylanosis, or microatheromas 15 Uncontrolled stroke-associated risk factors, such as aging, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, are considered the most significant factors for the development of lacunar infarcts. They are estimated to represent 15–25% of all ischemic strokes in the United States Ischemic stroke outcomes are variable depending on size, co-morbidities, and interventions available Lacunar stroke outcomes are better than for other stroke subtypes, with 96% having a 30-day survival rate and 70–80% of patients having functional independence at one year 16 Over 20 lacunar syndromes have been described, including the classic 5 lacunar syndromes first established by Dr Charles Miller Fisher in the 1960s, which continue to be used today Detailed in the following discussion, they have been validated for predictive value between physical examinationfindingsandradiographicstrokecorrelation 17

311PUREMOTORHEMIPARESIS

Pure motor stroke is the most common lacunar syndrome, comprising 45–57% of lacunar syndromes 18 This syndrome primarily affects the posterior limb of the internal capsule, which carries descending corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts, thus interrupting descending motor relay signals. Lesions can also be seen in the pons Clinically, the patient presents with hemiparesis (weakness) or hemiplegia (paralysis) of the face, arm, andlegcontralateraltotheinfarctedregion;itisnottypicallyassociatedwithsensory,vocal,orvisualdeficits

312PURESENSORYSTROKE

Pure sensory stroke is estimated to encompass 7–18% of lacunar strokes19 and most consistently localizes to

theventralposterolateralnucleusofthethalamus.Thisstrokepresentsasacontralateralnumbnessoftheface, arm, and leg and in the absence of motor, verbal, or visual deficits The sensory loss associated with this syndromeisusuallynotedtoceaseatthemidline,whichischaracteristicoflesionstothethalamus.

3.1.3SENSORIMOTORSTROKE

This lacunar syndrome is an infarct that affects both thalamus and the adjacent portion of the internal capsule’s posterior limb, effectively causing both sensory and motor symptoms Patients with this pattern describecontralateralhemibodyweaknessandsensoryimpairmentoftheface,arm,andleg

314ATAXICHEMIPARESIS

Ataxichemiparesis,thesecondmostfrequentlacunarstroke,hasbeenshowntohavea95%positivepredictive value for corresponding radiologic lesions 16 This syndrome results from damage to the corticospinal and cerebellar pathways by infarction of the pons or internal capsule Ataxic hemiparesis features both cerebellar and motor symptoms, including weakness and clumsiness on the ipsilateral side of the body, with the lower extremities typically more involved than the upper extremities A combination of pyramidal signs (hemiparesis,hyperreflexia,Babinskisign)andcerebellarataxiamaybepresentontheaffectedside

315DYSARTHRIA-CLUMSYHANDSYNDROME

Dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome is the least common of all lacunar syndromes, accounting for 2–6% of lacunar strokes in a case series review 17 It is sometimes considered a variant of ataxic hemiparesis, as it also involves infarction of the pons or internal capsule However, this syndrome differs in its characteristic dysarthriaandcontralateralhandweakness,whichisoftenbestprovokedbytestingthepatient’shandwriting. Withapontinelesion,facial,andtongueweaknessmayalsobeseen

Question1.3:Whatisthemostcommonocclusionsiteinlargevesselocclusionstrokes?

Answer:Proximal(M1segment)middlecerebralartery(MCA)

32Largevesselstrokesyndromes

In contrast to small lacunar infarctions, thrombosis of higher diameter vessels can produce infarct in large arteries supplying significant neuronal tissue. As previously described, thrombotic ischemic events are associated with elevated blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use, and age Progressive atherosclerosis acts to impede blood flow to cerebral vascular territories, with thrombosis ultimately terminating blood supply to distal cerebral structures. Large vessel thrombotic disease can encompass extracranial (common carotid and internal carotid arteries), posterior cerebral circulation (vertebral arteries), and intracranial artery (Circle of Willis and its more proximal divisions) territories Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the normal cranial and cervical anatomy of major arteries supplying the brain. As stenosis impedes blood flow, fragments from these obstructed arteries can break off as emboli to travel distally; like embolic strokes from elsewhere in the circulatory system, stroke occurs as the emboli reach arteries too small to transverse.Whileatherosclerosisisthemostcommoncauseofthromboticischemicstrokes,otherpathologies affectingthesevessels,includingdissection,arteritis,fibromusculardysplasia,andvasculopathies,cansimilarly produceinfarction 19

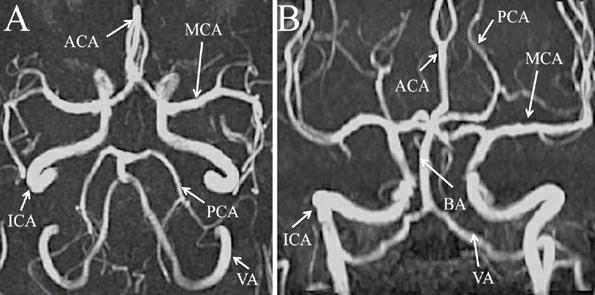

Figure12Intracranialarterialcirculation

(A)Axialand(B)coronalviewsoftheMRangiographyoftheheadshowingnormalvascularanatomy

ABBREVIATIONS:ACA,anteriorcerebralartery;BA,basilarartery,ICA,internalcarotidartery;MCA,middlecerebralartery;PCA,posterior cerebralartery;VA,vertebralartery

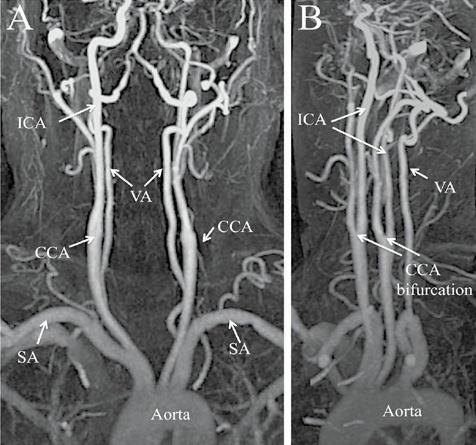

Figure13Cervicalarterialcirculation

(A)Coronaland(B)obliquelateralviewsofthemagneticresonanceangiographyoftheneckshowingnormalvascularanatomy

ABBREVIATIONS:CCA,commoncarotidartery;ICA,internalcarotidartery;SA,subclavianartery;VA,vertebralartery.

Acuteischemicstrokesaffectinglargearteriesproducecharacteristicneurologicdeficitsbasedontheareaof neuronal tissue impacted. Once familiarized with the clinical characteristics of large vessel occlusion syndromes, a clinical provider can easily and reliably localize the likely area of at risk neuronal tissue prior to radiographic findings In scenarios when imaging availability is limited or delayed, such knowledge can assist inrapidlymobilizingmedicalandsurgicalinterventions.

321ANTERIORCIRCULATIONSTROKES

The blood supply comprising the anterior portion of the cerebral hemispheres is derived from the common carotid arteries, which further divides into internal and external division at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra. The internal carotid divisions travel into the cranium to supply the brain, while the external carotid branches travel superficially to supply the neck and face. Within the skull, the left and right internal carotid arteries further divide into corresponding cerebral branches, comprised of left and right anterior cerebral and middle cerebral arteries. These arteries supply large areas of eloquent tissue over the frontal, parietal, and temporallobes.

3.2.1.1Middlecerebralarterystroke

Acute occlusion of the internal carotid and left MCA produces characteristic clinical deficits, with the MCA being the artery most often occluded in stroke.20 The MCAs are the primary blood supply for the motor and sensory cortices involving the head, neck, trunk, and arm; the basal ganglia; and the anterior portion of the internal capsule In over 90% of the population, the left cerebral hemisphere is also the dominant hemisphere conferringlanguagecomprehensionandfluency.21

The MCA then further bifurcates into two main branches: the superior and inferior divisions Often, the MCA is classified into four segments based on nearby anatomic landmarks 22 The sphenoidal segment (M1) is the origin of the MCA to the bifurcation. The second M2 segment, also known as the insular segment, encompasses the bifurcation to the insula The more distal M3 segment (opercular branches) lay within the Sylvian fissure, and the M4 region describes the branches over the outer convexity of the brain Infarction to anybranchoftheMCAcanproduceclinicallyevidentstrokesyndromes.

A large stroke affecting the main trunk of the MCA prior to its bifurcation will produce contralateral hemiplegia, deviation of the head and eyes toward the side of the infarct, contralateral sensory loss, and hemianopia(partialvisuallosssecondarytovisualradiationtractinvolvement)(Case1.2).23 Inaddition,ifthe stroke is located in the dominant hemisphere, global aphasia will also occur as speech and language centers becomeimpaired Inthenon-dominanthemisphere,neglectandimpairedawarenessofthestrokeisexpected When the infarct is large with significant brain tissue involvement, there is risk for decline and herniation secondary to development of cytotoxic edema in the region, known as malignant infarction 24 Malignant infarctions usually require an escalation in acute management, either with medical or neurosurgical management.

MCA strokes distal to the superior/inferior branch bifurcation will produce symptoms similar to those of a complete artery occlusion, though likely less severe A superior division MCA occlusion in the dominant hemisphere will produce weakness and sensory deficits to the contralateral hemibody and is likely to produce expressive(Broca’s)aphasia. 25,26 Thistypeofaphasia,whichoccurswithdamagetotheinferiorfrontalgyrus, affects the ability to speak fluently but spares comprehension In a non-dominant stroke to the superior division, weakness and sensory loss may be present with some degree of visual/spatial neglect; language is not usuallyimpaired.27

An inferior division MCA stroke often spares the motor and sensory regions but does involve verbal and visualareas.InaleftdominanthemispherestrokeoftheinferiorMCA,theprimaryexaminationfindingsmay be contralateral homonymous hemianopia (visual field loss on the right side of the vertical midline) and receptive(Wernicke’s)aphasia 23,24

3.2.1.2Anteriorcerebralarterystroke

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) occlusion represents between 06% and 3% of all ischemic strokes 28,29

The ACA extends upwards from the internal carotid artery and supplies the frontal lobes, the parts of the brain that control personality, logical thought, and lower extremity movement. Stroke within the ACA territoryproducesischemiawithintheparacentrallobule,usuallyresultinginsensorylossandweaknessinthe contralateralleg Weaknessisusuallygreaterinthedistallowerextremitythanproximally Lesionswithinthe ACA can also produce symptoms of anomia (the inability to recall the names of everyday objects), agraphia (theinabilitytowrite),andabulia(lackofwillorinitiative),aswellasemotionalandpersonalitychanges

322POSTERIORCIRCULATIONSTROKES

The vertebral arteries originate from the subclavian arteries and travel upward Inside the skull, the two vertebral arteries join at the junction between the medulla oblongata and pons to form the basilar artery. The basilararterycontributestothemainbloodsupplyforthebrainstem.Severalaccompanyingarteriesbranchoff the basilar artery, including the posterior cerebral arteries, superior cerebellar arteries, and anterior inferior cerebellar arteries, as well as multiple minor paramedian perforating arteries. Strokes involving the posterior circulationaccountforapproximately20%ofallischemicstrokes.30

3.2.2.1Basilararterystroke

Acuteocclusionofthebasilararteryhasdramaticeffects oncirculationtothebrainstem Theyaccountfor1–4% of all ischemic strokes but are associated with a mortality rate of greater than 85% without intervention.31 The most common presenting symptoms association with this stroke type is often imprecise on initial evaluation Prodromalsymptomsincludenausea,vomiting,headache,andneckpain Ifocclusionislocatedin themid-basilarregion,patientsmayprogresstolocked-insyndrome, where bilateral ventral pontine ischemia produces full body paralysis, lateral gaze weakness, and aphasia; however, these individuals remain cognitively intact and vertical eye and blink movements are preserved Occlusion of the distal tip of the basilar artery results in topofthebasilarsyndrome, causing ischemia of the midbrain, thalami, inferior temporal lobes, and occipital lobes (Case 13) This can result in decreased alertness, loss of voluntary vertical eye movements, upper eyelid retraction, delayed or absent pupillary reaction to light, or visual hallucinations In contrast to other syndromes, sensory and motor abnormalities are often absent. Most occlusions of the rostral brainstem are associated with embolic phenomenon and require urgent neurological and neurosurgical evaluation and treatment,giventhepoorprognosisassociatedwithinfarctsinthisregion

3.2.2.2Posteriorcerebralarterystroke

Common symptoms of a posterior cerebral artery stroke include dizziness, imbalance, visual deficits (contralateral hemianopia with macular sparing), nausea, and sensory loss affecting the contralateral face and limb Weakness may be variably present, as the posterior aspect of the internal capsule receives some blood supplyfromtheproximalportionsoftheposteriorcerebralartery.

3.3Strokesyndromes mediumsizevessels

3.3.1ANTERIORCHOROIDALARTERYSTROKE

The anterior choroidal artery originates from the internal carotid artery and travels intracranially to supply portions of the optic tract, thalamus, midbrain, and internal capsule This rather small-size vessel can neverthelessresultinanumberofneurologicaldeficits.Infarctionoftheanteriorchoroidalarterycanproduce hemiplegia, sensory deficits of the contralateral body, and homonymous heminanopsia as a result of internal capsule, thalamus, and optic tract impairment Symptoms are often variable given the presence of adjacent bloodsupplyfromlenticulostriatearteriesoftheMCA.32

3.3.2SUPERIORCEREBELLARARTERYSTROKE

Thesuperiorcerebellarartery,derivedasabranchofthebasilarartery,travelsposteriorlyaroundthecerebellar peduncle to the surface of the cerebellum, thereby supplying part of the midbrain, cerebellar vermis, and the superior half of the cerebellum While stroke affecting the cerebellum accounts for less than 2% of all acute ischemic infarcts, nearly half of them involve the superior cerebellar artery.33 Symptoms associated with cerebellar infarcts are often vague, presenting as poorly defined headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting Signs localizing to the midbrain such as dysarthria, nystagmus, and Horner’s syndrome or to the cerebellum (ipsilateralataxia,intentiontremor)maybeofdiagnosticassistance.

333ANTERIORINFERIORCEREBELLARARTERYSTROKE

The anterior inferior cerebellar arteries travel from their origins in the basilar artery posteriorly to the cerebellum, where it supplies the anterior inferior surface of the cerebellum, the middle cerebellar peduncle, and lateral pons. Stroke in this region is somewhat uncommon given anastomoses among the superior cerebellararteriesandposteriorinferiorcerebellararteries 34 Whenitdoesoccur,multiplenucleiandtractsare affected, producing lateral pontine syndrome (Marie-Foix Syndrome) Symptoms associated with this includes contralateral loss of pain and temperature from the trunk and extremities from spinothalamic tract involvement, contralateral weakness of the upper and lower extremities from corticospinal tract involvement, ipsilateral paralysis of the face secondary to facial nucleus and nerve involvement, and ipsilateral cerebellar ataxia from affected cerebellar peduncles. Descending sympathetic tracts may also be subject to ischemia and resultinipsilateralHorner’ssyndrome

334POSTERIORINFERIORCEREBELLARARTERYSTROKE

Theposteriorinferiorcerebellararteryisthelargestbranchofeachvertebralarterypriortotheirconfluenceto form the basilar artery. This artery travels past the medulla oblongata, over the cerebellar peduncle to the inferior surface of the cerebellum Occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery results in a well described syndrome known as Wallenbergsyndrome(lateralmedullarysyndrome) This syndrome classically produces crossed sensory findings of loss of pain and temperature sensation on the contralateral side of the body and ipsilateral side of the face Multiple cranial nuclei reside in this region and contribute to the other symptomatic findings of this infarction, including gait dysphasia, nystagmus, vertigo, ataxia, and ipsilateral Horner’ssyndrome(ptosis,miosis,andanihdrosis).

3.3.5ANTERIORSPINALARTERYSTROKE

Infarction of the anterior spinal artery, which branches from each vertebral artery and joins at the level of the

medulla oblongata, can result in Dejerine syndrome (medial medullary syndrome) Though extremely infrequent,lessthan1%ofallvertebrobasilarstrokes,itiseasilyidentifiedwithclassicalclinicalcharacteristics The presentation usually consists of deviation of the tongue toward the side of the lesion secondary to hypoglossalnerveinvolvement,contralateralhemiparesisorhemiplegia,andcontralateralsensoryloss.

34Embolicstroke

Acute ischemia from embolic sources can cause any of the previously mentioned stroke syndromes or a combinationofneurologicalsymptomsifembolitraveltomultiplevascularterritories Ofembolitothebrain, approximately 80% involve the anterior circulation, with the remaining 20% involving the posterior cerebral bloodsupply.

Cardiogenicembolismaccountsforapproximately20%ofischemicstrokesintheUnitedStates,andnearly 50% of those are related to non-valvular atrial fibrillation.35,36 Other cardiac sources of emboli include ventricular thrombus, prosthetic valves, acute myocardial infarction, rheumatic heart disease, cardiac tumors, and paradoxical emboli via atrial septal defects such as patent foramen ovale Atrial fibrillation is present in approximately 1% of the US population and increases in prevalence with age. This arrhythmia is associated with a fivefold increased risk of stroke and often requires extended cardiac workup and electrocardiogram monitoringtouncover

4HEMORRHAGICSTROKE

Herewefocusourdescriptionmainlyonintracerebralhemorrhage(ICH),whichresultsfromvascularrupture and bleeding directly into brain parenchyma, with possible extension into the ventricles (known as intraventricular extension) Subarachnoid hemorrhage is discussed in the chapters on medical and surgical management of hemorrhagic stroke. Cerebral venous thrombosis shares some features of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke However, given its unique mechanisms and course, cerebral venous thrombosis is a separatecategoryandisreviewedinaseparatechapter

While less frequent than ischemic stroke, ICH encompasses between 10–15%41 of all strokes, comprising approximately 40,000 to 67,000 cases each year in the United States The extent of appreciable neurological dysfunction is dependent on several factors, including size and location of the bleed, degree of edema in the surroundingtissue,andcompressionofsurroundingintracranialstructures.

ThemostimportantriskfactorforthedevelopmentofICHishypertension.AfricanAmericans,whohave a higher frequency of hypertension, have in tandem been noted to have a higher frequency of ICH 37 Incidence has also been noted to be higher in Asian and Hispanic populations.38,39 Other risk factors that have been correlated, in varying degrees, with ICH include increasing age, sympathomimetic drug use (cocaine, amphetamines), and high alcohol use While hypertensive vasculopathy persists as a principal cause of non-traumatic hemorrhages, other etiologies include cerebral amyloid angiopathy, vascular malformations such as arteriovenous malformations and aneurysms, venous sinus thrombosis, vasculitis, coagulopathy, use of anticoagulationmedications,andcerebraltumors

Clinical presentation of ICH is variable but often occurs as an acutely progressive alteration in consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and headache; seizures occur in approximately 6–7% of presenting scenarios.

Hemorrhage into a specific cerebral region will likely cause dysfunction of that eloquent tissue and may present as aphasia, hemiplegia, vertigo, diplopia (double vision), or sensory deficits Hypertension-related ICH occurs predominately in the basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum, whereas hemorrhage associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy or cerebral arteriovenous malformations typically appears in a lobar distribution Large intracranial bleeds may be evident with patients who are comatose at initial presentation, along with markedly high blood pressures >220/170 mm Hg. Rapid computerized tomography (CT) scan and vascular imaging aides significantly in the detection and treatment of these patients, with radiographicvariationsdiscussedinthechapteronimagingofacutestroke

Mortality associated with ICH is significant, with a review from 30 centers reporting a 34% mortality rate at 3 months.40 Other reviews reported mortality rates of 31% at 7 days, 59% at 1 year, 82% at 10 years, and morethan90%at16years 41,42 Toaideinprognosticassessment,anICHscorecalculationwasdevelopedby JC Hemphill et al. in 2001; it is still an efficient computational tool for all providers. The components of the ICH score are derived from the patient’s age, presenting Glasgow Coma Scale, the degree of ICH volume, the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage, and the location of the hemorrhage (infratentorial vs supratentorial).ThecorrespondingICHscoreforthesevalues(between0–6points)providesmortalityriskat 30days.

Early assessment and management of intracranial hemorrhage focuses on maintaining hemodynamic stability, airway protection, and correction of any underlying coagulopathy These patients invariably require intensive care monitoring and often neurosurgical evaluation in the acute phase, given the risk of progression of bleeding, swelling, or herniation syndromes that could necessitate urgent surgical intervention Diligent correction of fever, hyperglycemia, treatment of seizures with antiepileptic medications, maintenance of systolicbloodpressure<18043 and frequent neurological examinations are vital to the management of ICH in thefirstfewdays

5CLINICALCASES

CASE11Transientischemicattack

CASEDESCRIPTION

Apatientinher70swithpastmedicalhistorysignificantforcoronaryarterydiseaseanddiabetespresentedto theEDwithatransientepisodeofword-findingdifficultyearlyintheday,whichresolvedspontaneouslyafter 30 minutes. The patient’s family witnessed the episode and stated that the patient could only answer simple questions with “ yes ” or “ no ” answers, but was able to understand most commands Blood pressure in the ED was 172/95 mm Hg The patient’s neurologic exam, upon evaluation by the emergency room physician, was unremarkable.MRIbrainshowednoevidenceofacuteinfarction(Figure1.4).

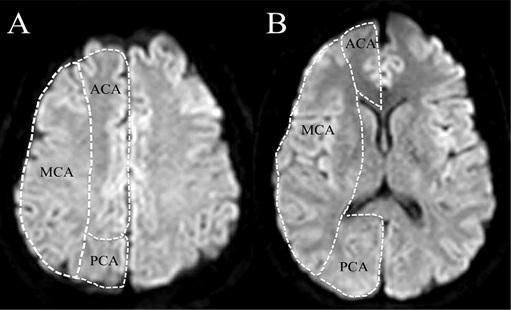

Figure 1.4 Case of a transient ischemic attack Magnetic resonance

acute

on the diffusion weighted image sequence,supportingthediagnosisoftransientischemicattack (A) Cortical and (B) subcortical regions are shown The anterior cerebral artery (ACA), middle cerebral artery (MCA), and posterior cerebral artery(PCA)territoriesareseparatedbythedottedwhitelines

PRACTICALPOINTS

• Thispatient’shistoryandpresentationarehighlysuspiciousforanepisodeofTIA Thedeficitisbest characterizedasexpressiveorBroca’saphasia Alternativediagnosis,suchascomplexmigraineorafocal seizure,islesslikely.

• “Negative”MRIbrainimaginghelpsconfirmthediagnosisofaTIA,andtheABCD2 scorecanguide theemergencyroomphysicianaboutwhetheraninpatientadmissionisindicated Somehospitalshave designatedTIAobservationunitswheretheminimumrequireddiagnosticTIAworkup(suchas telemetry,carotidultrasound,andcardiacechocardiogram)canallbecompletedwithin24to48hours

CASE12MCAstroke

CASEDESCRIPTION

A patient was brought to the hospital by the paramedics after a 911 call made by a bystander who witnessed the patient collapsing at the mall. The patient was noted to have deviation of the head and eyes to the right, left-sidedhemiplegia(paralysis),andsensoryloss Bloodpressureonarrivalwas221/112mmHg

PRACTICALPOINTS

• Emergentimagingisrequiredtodifferentiatebetweenischemicversushemorrhagicstroke This patient’sexamfitsthedescriptionoftherighthemisphericsyndrome.Ifintracranialhemorrhageisruled out,additionalimagingisneededtodetermineiflargevesselocclusionisresponsibleforthispatient’s neurologicdeficits(suchasoftheproximalrightMCA;Figure15)

Another random document with no related content on Scribd: