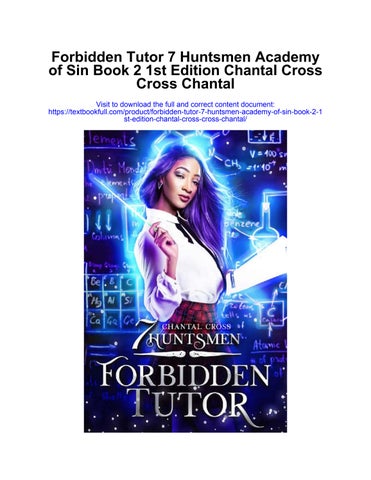

FORBIDDEN TUTOR: ACADEMY OF SIN

THE 7 HUNTSMEN - BOOK 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2019 by Chantal Cross

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Published in the United States

Cover design by Sekhmetrics

Chantal’s Website: https://chantalcross.com

CONTENTS

1. Rhiannon

2. Ebony

3. Leo

4. Ebony

5. Lucien

6. Ebony

7. Seth

8. Ebony

9. Kashton

10. Ebony

11. Ebony

12. Leo

13. Ebony

14. Wrath

15. Ebony

16. Ebony

17. Leo

18. Gabriel

19. Lucien

20. Seth

21. Ebony

22. Leo

23. Leo

24. Ebony

25. Ebony

26. Leo

27. Seth

28. Ebony

29. Ebony

30. Leo

31. Wrath

Chantal Cross

7 Huntsmen Series

RHIANNON

I AM as ancient as the water that flows far beneath this dank cavern. If I sit completely still, I can hear the water babble in a tongue only someone as ancient as I would know. All ancient things speak the same language. The stones around me are ancient too, but they do not speak as the water does. There is life in water. There is life in me. There is no life in the stone. There will never be life in the stone no matter how long it sits on this earth. If the stone is lucky, it might soak up a little magic but it will never be like the water. It’ll never be like me.

I run a hand along the stone wall. It’s so dark that I can’t see my own hand. That’s all right. Darkness has never bothered me. In fact, I thrive in darkness. I built my domain in darkness. My glorious kingdom dominated the shadows, the black depths of water, and the deepest pits of the earth. Now, my kingdom is no more. The darkness remains, because darkness, like the water and like me, is eternal.

There’s a noise above me. Someone’s arrived.

I stand and make my way through the darkness. It clings to my skin as I reach for the door. It doesn’t want me to go.

“Rest easy, pet. Your time will come again.” I stroke a loving hand through the darkness. I feel nothing but I know the darkness listens. All of my children that I’ve left behind in the darkness will rise again. I swear on the stone heart in my chest.

I push through the doorway and ascend the stone steps. Light bleeds in. It’s not natural light. No, I’m too far beneath the earth for sunlight. I’m somewhere under the magic academy where I was brought back into this realm. The school is heavily fortified. Magic doors, enchanted traps, and mythical beasts guard every turn. I’m corralled into a small section of rooms.

I still don’t know if these rooms were cleared for my return or if they were just forgotten. Either way, I have not the strength to go beyond these rooms. For the time being, I am contained. This does not bring anger. I have been contained before. I bided my time and rose again. This time shall be no different.

The stone steps twist in on themselves, looping back around and around until I’m on the next landing. The landing would still be considered dark by a mortal’s standards. Only a few bobbing orbs of celestial faelight hang in the air. It’s not enough to drive out the shadows. That’s how I prefer things.

My inner magic is weak after being suspended between realms for one thousand years. I was on a plane somewhere between existence and non-existence. I’ve never experienced anything like it before. My time in that place that was also not a place did strange things to my magic as well as my body. Were I to venture above ground right now, the sun would sear my skin and blind me.

As it turns out, I’m not done biding my time.

A figure stands in the center of the room. He’s tall and handsome. It is because of his loyalty that I have survived this long. It’s the Huntsman of Envy. Once sworn to protect Snow White, he’s sworn himself to me. What a darling creature he is. While the rest of the Hunstmen think he died in the funeral pyre, they didn’t see that I had snatched his beautiful body and trapped him in my Mirror.

“Dorian,” I purr. “Thank you for seeing me.”

“Of course, my Queen.” He drops to one knee like the good pet he is. He learns well. I stride over to him. I run my hand through his hair and stroke his cheek. I grip his chin, forcing him to look up at me. His stony expression doesn’t waver. There’s no fear in his eyes.

Excellent. Now isn’t the time for fear. I’ve never been this powerless. I don’t care for it.

“Any news?”

“The spells keeping you contained here are powerful. They are not designed to be undone by a single magician.”

“So, you have nothing.” I clench my jaw. It takes effort to keep my face serene. I don’t control my subjects through fear. I’ve learned that fear only goes so far. Fear doesn’t inspire loyalty. But love does.

“I’m sorry, my Queen.”

“It’s all right.” I run my thumb across his cheek. My nail leaves a whisper-thin mark on his cheek. If he feels it, he doesn’t react. “We need to change our strategy. I should’ve known you wouldn’t be strong enough to do it on your own.”

“Yes, my Queen.” He didn’t rise to the bait. That’s no fun.

“I have a proposition for you,” I say. “How would you like to be my personal spy?”

“It would be an honor, my Queen.” His eyes fill with adoration. If I asked him to kiss my feet, he’d agree. Weakling. “However, I’m supposed to be dead. The school hosted a funeral for me. They burned my body on the pyre.”

“Not your body. A body.” I say through my teeth. “You’re a clever little sprat, aren’t you? You’ll figure it out. Disguise yourself as a raven, a rabbit, or a snail. I don’t care.”

“And even beyond that, I can do very little as long as you keep me trapped in the mirror and only allow me to walk as a reflection in this realm.”

“Oh, you’ll never be free of my Mirror, pet,” I say with a smile. “But you should explore that Mirror. See if you’re able to utilize it’s secrets. It’s older than even me.”

“Yes, my Queen.”

“Once you find your mobility again, you will make the Mirror your home. But you will be my eyes and ears. You will report anything you see Snow White or her little companions do,” I instruct. “Regardless of how insignificant you think something to be, tell me. The littlest gesture could be the key to our release.”

“Yes, my Queen.”

“I also want you to focus on revealing Wrath’s location,” I say.

“Yes, my Queen.”

I try not to grimace. The constant groveling can be a bore.

Wrath, the seventh cursed prince. A Huntsman once sworn to protect Snow White. I can’t see him. Even with my limited magic, I should be able to sense his presence. I spend hours scrying in the darkness, yet I can never find him. He’s using a concealment spell.

Some of Snow White’s faithful Huntsmen have turned out to not be so faithful after all. Dorian is living proof of that, as is Leo the Headmaster of the school. I’ve twisted them into my web.

Wrath has made himself scarce since he helped seal me away all those years ago. Neither Dorian or Leo know anything about what he’s been doing all these years.

Wrath was always the most unpredictable of the Huntsman. I’ll have to be careful. Wrath contains enough power to be a threat to me in this state. I’m so weak.

I’m disgusted with myself.

I cannot rely on Wrath to be of service to me. While it’s possible that he could be easily swayed into my forces, it’s not a risk I can take now.

Fortunately, I have another play in progress.

The Huntsman of Pride, Leo has graciously offered to tutor sweet Snow White. She’s only just regained her powers. She’s undisciplined. Feasting on her magic now would do wonders for me in this despicable state, but I want more than that.

Leo will shape her, train her, and guide her so that her power will grow to its full potential. With a little bit of luck, she will vanquish Wrath before I have to deal with him. Then, once Leo’s earned her trust, he will bring her to me. I will feast on the most powerful heart in the land. My power will return to me. My kingdom will flourish once more. My children of the darkness will finally have a home. Nothing will stop me. I will never be sealed away again.

“My Queen?”

“What?” I snap.

Dorian clasps his hands in front of him and bows his head.

“Forgive me, my Queen. A look came over your face. I just wanted to know if you’re well.”

“Oh.” I wave a lily-white hand dismissively. “Of course, dearest one. I’m simply exhausted. With so little power, I feel that I will waste away at any moment. I’ll turn into dust or moon vaper and be scattered across these rooms.”

I’ll admit that was a touch melodramatic but I need him to think that I need him. If I were at my full strength, I wouldn’t need to dally with these mind games. Every inch of him would belong to me.

My control over the creatures near me isn’t absolute without my full power. I can make creatures adore me just by being near them. It’s how I grow my armies. But without that power, Dorian needs to genuinely feel something for me. I have to appeal to the hero within him.

Thus, my little performance.

“May I assist you, my Queen?” He asks.

Truth be told, my strength wanes. I will need to return to the darkness soon. I need to be closer to the ancient water.

“Please.” I extend a trembling hand. He takes it and drapes it over his shoulder. “Take me down as far as you can. I must rest.”

“Of course, my Queen.”

I lean on him for support. He believes every hesitant step and wobbly turn. His strong hands grip my narrow waist as we descend the stairs.

The darkness surges forward to engulf me. Dorian becomes less sure of his steps but presses on. How admirable.

“Where should I go from here, my Queen?” The darkness is absolute.

“You may leave me here. I know the way.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, dearest. You may go. Remember your mission. I expect news very soon.”

“Yes, my Queen.” He bows to me even though he cannot see me. I hear his footfalls retreating.

Surrounded by darkness, I walk forward.

“I’ll be free soon,” I say to the darkness. It caresses my cheek like a loving pet. I return to the ancient stone walls and sink to the

ground. In the silence, I listen to the ancient water and gather what little strength I have.

EBONY

I LIE AWAKE, staring at the patterns of moonlight on the ceiling. I haven’t been able to fall asleep even though I’ve been trying for hours. I lift my head to check the timepiece on the bedside table. It’s half past midnight. Too soon to get up.

For fun, I magically manipulate the moonlight into shapes an patters. A winged horse. A sword and shield. An apple with a bite taken out of it. I stare at the apple for some time then withdraw my magic. The moonlight returns to its natural form.

I can’t sit like this any longer. I have to move.

Sleep hasn’t come easy to me since I died. When Seth’s kiss brought me back to life, I felt more alive than I ever had before. The feeling soon faded. Sleep evades me. I jump at shadows. Whenever I walk into a room I expect to see Rhiannon the Demon Queen or Professor Glaw ready to snatch me away.

Knowing that I’m not prepared to face something like that was what brought me to Headmaster Leo. I didn’t trust him but that didn’t change the fact that I needed him. He serves the Demon Queen, I heard him admit as much. He’s also the most skilled magician for miles. He’s not headmaster of the school for nothing.

I was surprised when he agreed to train me. Once I shook his hand, I felt the pang of regret. I’m playing a dangerous game. The chance to pull myself out of it slowly slips away from me. Of course, I know there’s no true escape. Not while Rhiannon walks this earth.

I don’t believe Headmaster Leo knows that I know who I am. I’m a reincarnation of Snow White, the legendary warrior who brought Rhiannon to her doom one hundred years ago. My companions, four of the seven immortal Huntsman, spent the last few days telling me stories of who I once was and what I once did.

I don’t know how I’m supposed to become that person again. I certainly can’t do it without help.

That’s where Headmaster Leo comes in. He must know who I am. But I don’t know if he knows that I know who I am. This whole affair is incredibly confusing. Often times, I wish I could just be Ebony again. I knew how to be Ebony.

I’m still Ebony. I just have to learn how to be Snow White too.

It’s now a quarter to one. I’ll arrive at the Headmaster’s office for training early if I leave now, but not too early. He instructed me to arrive exactly at one, but I can’t sit in this room any longer. I’ll go mad.

I change out of my nightgown and pull on comfortable clothing I can move in. I’m not sure what Headmaster Leo will have me do tonight, but I want to be prepared. After all, there’s a chance he could decide to murder me.

I hesitate at my bedroom door. Maybe I should’ve told one of the Huntsman. Lucien, the Huntsman of Lust, probably would’ve agreed to keep it a secret. He likes to shake things up when he can. Seth, the Huntsman of Sloth, would’ve tried to talk me out of it the moment he knew. Gabriel, the Huntsman of Gluttony, might’ve gone as far as to lock me away to prevent me from seeking out Headmaster Leo’s tutelage. Kashton, the Huntsman of Greed, would’ve offered to teach me himself. He’s talented with magic and the smartest person I’ve ever met, but he doesn’t have the Headmaster’s power.

I take a deep breath and step into the dormitory hallway. All of the faelight torches have been extinguished. No one walks the halls at this hour. I pass the doors to other rooms. Through the floor crack of one of them, I can see the flicker of candlelight. A girl giggles inside.

I smirk to myself thinking there’s a good chance Lucien’s in there with her. Even I’m willing to admit that he’s the most handsome man I’ve ever seen. The moment I saw him sitting under the apple tree on the grounds, I was taking in by him.

I mistakenly assumed he only wanted one thing from me. Lucien surprised in more ways than one. Not only is he an amazing kisser (no surprise there) but he’s proven himself as a true ally. I understand why I, as Snow White, wanted him by my side through every battle.

He’s the opposite of Seth. It was Seth’s kiss that brought me back from the dead. If any of them has my heart, I’d say it belonged to Seth. We grew up together with Gabriel in the house of our foster mother, Cordelia. Cordelia did everything she could to keep us separated. She even took on a job here, at the school, as a cook. She was the one who fed me the poison that would’ve killed me if it weren’t for Seth.

Cordelia’s still trying to earn my forgiveness, but I’m having none of it.

Seth knows I have trouble sleeping. The first night back in my own bed, he slept beside me. It didn’t help. It only made me more afraid that Rhiannon would appear at the foot of my bed and slaughter him before me. I keep my windows and doors locked to all visitors now. I keep to myself during the day.

Rhiannon must be somewhere, watching and waiting. I don’t want her to know how much Seth, Lucien, Gabriel, and Kashton truly mean to me. It’s better if she doesn’t know how close I am with Ivora, a charming fairy with a knack for potions, either. The more I can keep them out of the mess I’m in, the safer they’ll be.

“We’ve got to do something about her.” I hear a voice in the adjacent hallway. It sounds like Lucien. What’s he doing walking around this late at night?

I slip into the shadows and conjure a weak concealment spell. It’s draining. I’m unskilled with my magic. I don’t know how to properly release my energy.

Lucien rounds the corner with Gabriel at his side. Those two have never pretended to be friends. Lucien doesn’t make friends easily.

He has more fun pissing people off or seducing them. Since he’s partial to women, that means Gabriel falls strictly into the pissing off category. Sometimes it’s fun.

Gabriel and I haven’t been close as of late. Now that I know my true identity, things might get better but I’m not going to hold my breath. If it keeps a target off his back, it’s worth the distance between us. Still, he’s the closet thing I’ll ever have to a brother.

“What do you expect me to do?” Gabriel sounds bored. He was probably sound asleep when Lucien burst into his room and yanked him out into the halls. Gabriel’s not even wearing shoes. Lucien’s fully dressed right down to his polished tall boots.

He looks handsome even in the middle of the night. My heart beats faster at the sight of him. I will it to calm down. I hope Seth is with them but it doesn’t look like he is.

“I don’t know. Care, maybe?” Lucien scoffs. “She’s not sleeping. She looks more exhausted by the day.”

“Seth is really the one you ought to talk to about this,” Gabriel grumbles.

“I’m talking to you.” Lucien glowers in the moonlight.

Lucien hasn’t told a soul that he and I shared a kiss. I sometimes feel guilty for keeping such a secret, but I’m grateful to him for not lording that moment over the others. The last thing I need is them tearing at each other’s throats.

Besides, I’m sure Seth is the one I’m meant to be with. I’m just sure of it. I feel safe with him. I feel many things with Lucien, but I’d never call him safe. And it was Seth’s kiss that saved me, after all. That means everything to me.

Sweat breaks out across my forehead. I can’t hold this spell much longer and I don’t trust darkness alone to keep me hidden from them.

Without meaning to, I loose a breath too quickly. Lucien’s head jerks up and swivels in my direction.

“Did you hear that?”

“No, I’m pretending I’m back in my bed instead of talking to a buffoon.”

“Don’t be an ass.” Lucien slowly walks closer to my hiding spot. I summon all of my strength to keep the spell stable.

He stands right in front of me. Should the spell waver, he’d find himself looking directly into my eyes. My body responds to his presence. I wonder if he can hear the frantic pitter-patter of my heart.

“There’s nothing there,” Gabriel whisper-shouts. “You’re just paranoid.”

“Now is the time to be paranoid. Snow needs us, even if she doesn’t realize it.”

I realize it. I long to tell him as much.

“We’re all in danger as long as Rhiannon walks the earth.”

“Tell me something I don’t know.”

“Go back to your room if you’re going to be this useless,” Lucien snaps. “I’ll find a way to help Snow without you.”

“You do that.” Gabriel waves over his shoulder, already halfway down the hall.

Lucien looks around for a moment more before leaving as well. As soon as he’s out of sight, I drop the spell.

They’ve made me late for my lesson. I hope the Headmaster will still see me.

As I navigate the darkened halls, I fear that Lucien will spring from the shadows. Though, out of all the things that could spring from the shadows, Lucien is the least harmful.

I reach the Headmaster’s office without further interruption. His door is open already.

Inside, he waits for me.

LEO

THE DAY HAS a special gleam to it as I contemplate my time with Snow.

Heading towards the basement where we planned to meet, I keep my composure but inside, I’m singing. As the principal I have to move through the school with detachment, I can’t show favoritism to her or let anyone get a hint of our plans.

But I can’t help the excitement from rising as I think about being close to her.

I nod and smile as I go, striding with my usual purpose. We have agreed to work in the basement to keep out of sight—of course, the principal offering a little private lesson occasionally is not something completely uncommon, but I don’t want to arouse any suspicions.

I want to arouse her.

I want to be alone with her and I want no distractions. We see each other around the school and as interesting as that has been, I want more. While working in school we are not alone together and this needs to change.

I want to be close to her… I want to touch her and feel the heat between us building. I’ve seen how she looks at me, even when she is hating me.

I know she’s fascinated. I can feel her being drawn to me, especially as she gets stronger. I plan on making her stronger still. The more connected she becomes to her old self the quicker my queen can take possession of her.

This thought is intensely sensual for me. The aching in my body for Snow herself increases to a painful pitch. The idea of my queen, free and wild, full of power in Snow’s body is an ache that throbs through my fingers, my chest, my guts. It’s visceral.

The added incentive of Snow abandoning her chaste ways for me almost makes me lose my head. Taking her can’t compare to the idea of her gifts being willingly given. I long for that moment of surrender, seeing her bend, body and soul as she yields up that kiss to me.

I pick up my pace through the halls, heading for the doors of the basement. No one pays much attention to me – I often have important business around the school. I don’t want it to be common knowledge I’m training Snow, even if it is easily explained after the amount of times she’s lost control of her powers.

I don’t want interference.

I don’t want to monitor or explain my actions.

I want to push her, physically and magically. I want to work in close quarters, bodies pressed up against each other as we sweat and shove.

I need those glances as she feels my hand brush her skin. The small, innocent expressions puzzling out how the power and physical contact make her feel.

I hurry down the stairs, my hard-soled boots making a hard tap against the cold stone. The basement is not too dark, thanks to scattered torches. You can always count on a magic school to have a few eternal flames around, especially in the darkest, spookiest spots.

I approach the third chamber on the right, where I asked Snow to meet me. She’s eager to explore her new powers and happy to be trained, even though she still has reservations about me.

I can hear faint thuds and a few sharp gasps. As I slide up to the door I peek around the corner.

She’s wearing black tights and a fitted grey T shirt. Her great cloud of black hair is caught at her neck but is struggling free to frame her face with weaving tendrils. Her red lips purse against each other, teeth gently nibbling the lower lip. She runs herself through a series of kicks, flowing across the floor, bouncing from foot to foot.

“Not bad.” I let my voice ring through the chamber as I step around the corner.

My instincts scream at me and I hurl myself towards the floor. A crackle of energy flies over my head. I stand up slowly, looking between Snow and the smoking crater in the wall behind me.

“I’m sorry.” She breathes hard as she lowers her hands. “You surprised me.”

I step forward slowly, cautious but not wanting to show it. She’s far more powerful than when I last saw her, and her powers are still wild and unpredictable.

I have to be careful.

“It’s good that your powers work on your instincts like that.” My voice comes out smooth and reasonable as I cross the room. “It will help to keep you safe. However, you don’t want to be firing energy bolts randomly, do you now?”

She grins as she gets her breath back. “No. We don’t want that.”

As I get closer her expression softens and her eyes seem to flicker deeper. She glances up at me from under her lashes and I feel my heart thump a little harder. It’s like her eyes have reached inside of me, awakening my urges.

I have to touch her.

I come up behind her, gently positioning her shoulders.

“Your line of kicks was excellent. You pivoted off each foot to change legs with ease. But if you had been facing an opponent, you would have failed. Do you know why?”

She tilts her head back slightly but doesn’t look at me. She seems to be trembling a little where I hold her shoulders. As her head moves towards me, I can smell the fresh scent of her clean hair. From beneath her clothes a deep, intoxicating aroma, something of perfume and lovely, clean skin mixed with just a little sweat hits me and for a moment I can’t think.

“No, I don’t know why. Can you tell me?”

I have to burrow through my thoughts a bit to remember the thread of my own conversation.

“Ah.” I grip her shoulders a little tighter, pulling one back a little and one forward. “Your core. The gymnastic ability and flexibility of

the kicks was impressive. You maintained your balance as you changed from foot to foot. You progressed through the kicks rapidly. But without your core engaged, the moment you actually connected with an opponent you would have been thrown off balance.”

As I pull one shoulder forward and back, I lean over her, taking in another hit of her wonderful smell. She leans into the pressure of my hands and it’s all I can do to stop myself pulling her against me, reaching across her body and holding her for a kiss.

I whisper in her ear.

“Feel your stomach tugging, as I move your shoulders?” I push the left forward, tugging the right back. Then I reverse the move.

“With your feet planted steady the way you have been taught, one slightly behind and one in front, as I move your shoulders, do you feel the muscles across your belly moving?”

“Yes, I do. It tugs back and forth in time with how my shoulders move.”

“Exactly. As you danced across the room kicking, you waved your arms for balance. It looked impressive. But without your stomach muscles held tight and the movement coming from within you, it was completely ineffective as an attack.”

She takes two steps away from me, half turning towards me. She runs her hands across her belly, fingers sliding on the tight shirt.

“Hmm.” She whispers, half closing her eyes. “So, you’re saying, the movement comes from here? I was focusing on my feet. I could feel the connection to my lower back and shoulders, but I didn’t think about my belly.”

“Common mistake. One that gets the self-taught killed when they run up against a disciplined warrior.”

She nods, opening her eyes. She focuses on the far wall, squaring her feet. I’m about to give advice when she starts her moves again, spinning off her left foot to kick with the right, then bring it down in one smooth motion to spin off it to raise the left.

This time her core stays tightly wound as a spring. The movement generates from her central strength and her legs move faster. Her feet become lethal weapons. She moves with surety and purpose.

She runs through a series of six spin kicks, finishing with a small cartwheel that brings her up facing me, one foot pointed like a dancer.

She grins at me and her red lips seem to draw my attention more than anything else.

“How was that?”

“Excellent. You are a fast learner. The movements need to be refined, but you have the idea now.”

“Okay.” She raises her fists. “How’s my guard?”

“Shocking.” I give her a withering glance. “Your right is up and in place to hit but your left is not even in front of your face. The left hand needs to be ready to move to block face, throat or belly. It seems you only care about your attacking hand, not your defensive move.”

She looks at both her hands, frowning.

“I don’t understand.”

I come in with a similar move to the one she was just practicing, crossing the distance with a few long strides. I fly in with kicks towards her face. Both arms come up to block, right in front of left as I push her back.

She manages to grab my boot on the third kick and push me back. I absorb the movement easily and rock on to my back foot, pushing back with both arms. She stumbles, barely keeping her feet.

“Okay.” She shakes her head, more stormy curls trailing around her face. “I get it. If I had blocked properly, I could have defended better—put the move back on you quicker and not stumbled when I did it.”

“Exactly.” My smile stretches across my face. “Again.”

EBONY

I CAN FEEL the sweat beginning to trickle down my face as Leo comes in with another series of kicks. I barely have time to think as he pushes me back. My muscles are aching, and I can barely block in time.

I try hard to land an offensive move, but his guard is perfect. He leaves me no openings. Maybe I’m just not fast enough.

I feel a flash of fear as he pushes me back again and my feet don’t obey me fast enough. My ankle twists and I fling my hands up instinctively.

There is a bright flash. I feel strength surging through my body. My feet find solid ground and I push against it, rippling the strength through my core, into my shoulders, down my arms which are crossed in front of my face.

I blink a few times. The light dies out quickly but leaves an imprint like a strobe. The first thing I see is Leo picking himself up off the ground.

“Oh, wow, what happened?” My question bursts out before I even have time to think it.

He shakes his head. “Another one of those power surges. I think we should focus on that for a while. It’s going to be a big problem for you.”

“Are you okay?”

He grins and somehow, I feel it tugging inside me. Deep. Beyond the core. Lower. My reservations about him are still there. I don’t

trust him, not after how much I’ve been through.

That just makes the strange heat rising in me even more complicated. Something about the sharp edges of his smile touch me from across the room. His eyes, though they are critically appraising me, feel like clean sheets drifting on my skin.

“I’m fine.” He grins wider, still somehow projecting it into my stomach where it births as a cluster of butterflies. “Just a little shock. What I’m going to do is fire a series of bolts at you. I’m deliberately going to trigger your survival instincts. Don’t think about it. Just let your body respond. After I finish firing, try to examine how you felt right before you reacted.”

I step back a little, feeling nervous. The crowd of butterflies in my stomach try to fly up my throat and fan my heart. It thumps wildly in response.

I’m not sure about this, not sure at all. It sounds dangerous in more ways than one. My instincts are screaming at me that something is not right.

But I set my feet, put my arms up and focus on Leo’s face. His grin has changed—there’s something self-satisfied about it. Something secretive.

I think I might be getting paranoid. Still, after the recent events in my life, I think I’m being smart withholding my trust.

Leo’s hands glow just a little as he energizes himself. His eyes go slightly blank and he fires small white darts from each hand. They come in fast.

I’m thinking too much. I raise my arms as the darts come in, deflecting them, but I’m doing it consciously—and poorly.

I see Leo frown. For a moment, his look is truly frightening. With a loud grunt he releases a flood of energy from both palms.

I put my arms up, turning my face away, cowering.

The light blinds me even with my eyes closed.

When I blink the room back into focus, I see Leo standing in a small, smoking trench. His arms are up before him, his head behind them.

“I’m sorry.” It’s the first thing that jumps from my lips—my damn apology reflex.

“No, No.” He shakes his head. “I asked you to push it. It was exactly what I wanted to happen. I just wasn’t expecting quite that much force.”

We come towards each other again, Leo making a few small stretches as we get close. I can see a little sweat at his hair line. I’m noticing his lips and his eyes but being near each other in this intimate, exposed way has me admiring his body, too. I had never really noticed him this much before.

His stomach is long and toned under the close-fitting shirt. His muscles bulge along his upper arms. The way he looks down on me from his great height, eyes intensely observing me, makes me warm and lightheaded.

My body is telling me something, and my mind doesn’t want to hear.

This is bad. I should not be feeling this way about anyone! —let alone Leo. It’s not his fine, fit body. It’s not his beautiful face. All of that helps, but the energy I’m caught on, that has finally made me notice him is far more attractive than his physical attributes.

He looks at me with respect. He doesn’t treat me like a little girl. Right now, we are equals, warriors, magic workers of the same ilk. I’ve never had anyone validate my power before. Leo is encouraging me, wanting to see what I can do.

Everything about him has shifted perspective for me. I feel like a woman, strong and confident, not a bumbling child everyone has to look after.

My smile as he draws near is a thing of genuine warmth. I let him see in my face how much I appreciate him. For a moment his gaze is far too intense—hungry, wanting—but before I can really see it the expression resolves into a slightly softer version of his usual principal mask.

We stand quite close, silence stretching out from us and seeming to echo back from the empty chambers beyond the basement.

“I’d like to do a bit more hand to hand, but we’ll try not to let it get too intense. I want to get those powers of yours under control— or at least get you to a place where yore aware you are about to use them. But for now, we’ll work on some hand to hand techniques. Try

to control your emotions as we go. Let me know if you feel anything so we can try and identify the moment it comes upon you.”

“Okay.” I nod firmly and get into position.

He takes two slow steps, bring a kick up to my left. I block easily with my left hand. He bounces on to his other foot, aiming a kick from the opposite direction. I block this one, too and sidestep, coming around beside him. I’m too close to lay a hit on his ribs and just spin across his back, coming up in fighting stance on the other side.

He grins. “Good. You didn’t land a hit, but you evaded perfectly. You can use a move like that to gain the upper hand again in any spar. Come in again.”

I step towards him, coming in with my hands instead of my feet. We engage briefly, hands flashing. I feel him grip my forearms, a sharp tug, then I’m flying through the air.

The ground rushes up against me, too hard. Leo lands on top of me and I’m squeezed between his body and the floor.

For a moment, there is nothing but our panting breath. All sound has fled.

Our eyes are locked together, lips only inches apart.

There is something almost crackling in the air. Its magnetism. Its palpable. It’s as if something is waiting, something huge. Like an explosion that will blow in my heart, flow through my body and change my whole world.

I feel like if one of us moves, the result will be irreversible.

Still. The heat from his lips. The power of his eyes on mine. That feeling in the air that is becoming so strong it’s almost a sound.

My body, acing, pounding, throbbing. His weight is crushing on top of me, yet it feels like electric fire.

I need him. I want him. I’m aching for him.

A smile flashes across his face. He knows, of course he knows. I’m frozen by my wakening passion, no idea what I want or even if I should want it. No idea how to act on these urges that are suddenly on fire under my skin.

But he does… He knows his body and he knows how to obey those urges. The idea makes me lightheaded, that he would guide

me, touch me gently, push me lightly… Just like we were minutes ago in combat. But instead of fighting we’d be naked, twisted, sliding on sweat, the tension just as high but being spent in a continuous loop between our bodies, our souls—

From somewhere in the floors above, there is a rattling crash. The walls tremble a little and some dust shakes free of the rafters.

“What the hell?” Leo looks up at the ceiling, pushing himself up but not getting off me.

“Yeah. That sounded big.” Suddenly I feel terribly awkward and I just wish he would get off me. My own feelings, my response to his heat, have confused me.

Perhaps, I am not good at controlling myself in more ways than one. My magic is erratic and based on my emotions. No wonder I find it difficult to curb when my own lust is riding me without any care to my will.

I shift a little, putting my hands up to press his shoulders. He gives me a surprised look—as if he forgot where he was for a second —then quickly gets up.

He eyes the ceiling with some annoyance.

“I had better go and check on that. We’ll take this up later.”

The look he shoots me is not a friendly one. It’s more like the old Leo. Frustrated and cross.

I just nod, hugging myself tightly, trying not to give in to my internal shakes. I think those butterflies in my stomach have gotten into my bones, because my whole body is trembling like it wants to fly away.

LUCIEN

WATCHING Snow in class the next day is torture.

I’ve been waiting since last night to see her. Gabriel and I had a pretty risky plan to sneak into the dorms, but we were getting desperate. The feeling that something was wrong wouldn’t let me rest.

Then Seth had to let out a very well-timed commotion that screwed our plans to hell. I know she wasn’t in bed; I know it. The feeling I had last night was strong enough, but looking at her now, I can be sure my fears had a foundation.

She glows. She’s always been beautiful—in any body, anywhere. Today, she seems gilded with magic. The air trembles around her and the light traces her hair making lines of sparkle around her face. Something has changed.

It’s something I can see as well as feel. Even from across the room as I watch her going through her books and glancing up at the teacher, I can see a quality that I’ve never noticed before. I must speak to her.

Last night, I was only suspicious. I could have dismissed my thoughts as paranoia, overthinking. I care for her so much, I can admit my own bias.

But now I see her, I know. She wasn’t in bed last night. I have to know where she was, try and figure out this change in her.

It’s like my anxiety has teeth, gnawing edges that tear at me. My frustration shoves at me with pointed claws. I can’t bear the

contented silence of the room as other students read through their books quietly, making occasional comments. I feel like my attention will burn a hole through reality, my eyes and will bent towards her with such force.

I breathe deeply, not allowing my feelings to manifest. For a moment I’m running through the halls again last night, fleeing from the sounds of Seth disturbing the peace of the entire dorm. At that time, I was stuck between getting caught and needing to see her safe. The memory is intense and powerful. My fear had risen like a dark, violent tide.

When I saw her in class, I was relieved, at first. I wanted to believe that she was okay so badly I didn’t look deeper. It’s only over the time we have sat in class that my feelings kindled again.

I realize with some irritation; I’ve been tapping my foot. I link my hands together and take another breath, spying at the clock. Not long to go now. Only a few minutes until class finishes, then I can speak to her.

She tosses her hair back, trying to tame it with one hand. The light that caught at her before slides across it, making her skin gleam and eyes shine.

Power. Power lurking beneath her hands. I can almost smell it. I’m caught between loving her and wanting her to be all she can be —and the knowledge that if she remembers everything and gains her birthright, she will be possessed by the evil I swore to fight to my death.

She starts to gather her books and I poise myself to move. I don’t want her to slip away in the crowd or become engaged with anyone else. I can’t talk to her properly if she is in a group.

The bell rings and people start to shuffle up. To my dismay Snow picks up her things and moves swiftly to the door. I get caught behind a few people, holding in my impatience with extreme difficulty. I can’t keep it together much longer and push past the last few students as I get near the door.

In the halls, people surge. I look around and tell myself what I’m feeling isn’t desperation. I’ve felt desperate before, on the edge of

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Before I could start an argument on this score, one of the able seamen, one who was thus discourteously commented on, observed, “I don’t know about that. Seems to me the mate of this here ship ain’t any too much shucks, or the captain either.”

The captain and I were a little dismayed by this. What to do with an able seaman who was too strong and too dull to take the whole thing in the proper spirit? It threatened smooth sailing! This particular person was old Stephen Bowers, the carpenter from the second floor who never to us seemed to have quite the right lightness of spirit to make a go of all this. He was too likely to turn rough but well-meant humor into a personal affront to himself.

“Well, Captain, there you are,” I said cautiously, with a desire to maintain order and yet peace. “Mutiny, you see.”

“It does look that way, don’t it?” big John replied, eyeing the newcomer with a quizzical expression, half humorous, half severe. “What’ll we do, mate, under such circumstances?”

“Lower a boat, Captain, and set him adrift,” I suggested, “or put him on bread and water, along with the foreman and the superintendent. They’re the two worst disturbers aboard the boat. We can’t have these insubordinates breaking up our discipline.”

This last, deftly calculated to flatter, was taken in good part, and bridged over the difficulty for the time being. Nothing was taken so much in good part or seemed to soothe the feelings of the rebellious as to include them with their superiors in an order of punishment which on the very first day of the cruise it had been decided was necessary to lay upon all the guiding officers of the plant. We could not hope to control them, so ostensibly we placed them in irons, or lowered them in boats, classifying them as mutineers and the foreman’s office as the lock-up. It went well.

“Oh no, oh no, I don’t want to be put in that class,” old Bowers replied, the flattering unction having smoothed his ruffled soul. “I’m not so bad as all that.”

“Very well, then,” I replied briskly. “What do you think, Captain?”

The latter looked at me and smiled.

“Do you think we kin let him go this wunst?” he inquired of me.

“Sure, sure,” I replied. “If he’s certain he doesn’t want to join the superintendent and the foreman.”

Old Bowers went away smiling, seemingly convinced that we were going to run the boat in ship-shape fashion, and before long most of the good-natured members of the crew consented to have themselves called able seamen.

For nearly a month thereafter, during all the finest summer weather, there existed the most charming life aboard this ideal vessel. We used the shop and all its details for the idlest purposes of our fancy. Hammers became belaying pins, the machines of the shop ship’s ballast, the logs in the yard floating debris. When the yard became too cluttered, as it did once, we pretended we were in Sargasso and had to cut our way out—a process that took quite a few days. We were about all day commenting on the weather in nautical phrases, sighting strange vessels, reporting disorders or mutiny on the part of the officers in irons, or the men, or announcing the various “bells,” lighthouses, etc.

In an evil hour, however, we lit upon the wretched habit of pitching upon little Ike, the butt of a thousand quips. Being incapable of grasping the true edge of our humor, he was the one soul who was yet genial enough to take it and not complain. We called upon him to shovel ashes, to split the wood, to run aft, that was, to the back gate, and see how the water stood. More than once he was threatened with those same “irons” previously mentioned, and on one occasion we actually dragged in a length, pretending to bind him with it and fasten him to the anvil (with the bos’n’s consent, of course), which resulted in a hearty struggle, almost a row. We told him we would put him in an old desk crate we had, a prison, no less, and once or twice, in a spirit of deviltry, John tried to carry out his threat, nailing him in, much against his will. Finally we went to the length of attempting to physically enforce our commands when he did not obey, which of course ended in disaster.

It was this way. Ike was in the habit of sweeping up his room—the smith’s shop—at three o’clock in the afternoon, which was really not

reasonable considering that there were three hours of work ahead of all of us, and that he was inclined to resent having his fine floor mussed up thereafter. On the other hand I had to carry shavings through there all this time, and it was a sore temptation to drop a few now and then just for the devil’s sake. After due consultation with the captain, I once requested him to order that the bos’n’s mate leave the floor untouched until half past four, at least, which was early enough. The bos’n’s mate replied with the very cheering news that the captain could “go to the devil.” He wasn’t going to kill himself for anybody, and besides, the foreman had once told him he might do this if he chose, heaven only knows why. What did the captain think that he (the bos’n’s mate) was, anyhow?

Here at last was a stiff problem. Mutiny! Mutiny! Mutiny! What was to be done? Plainly this was inconveniencing the mate and besides, it was mutiny. And in addition it so lacerated our sense of dignity and order that we decided it could not be. Only, how to arrange it. We had been putting so much upon the bos’n’s mate of late that he was becoming a little rebellious, and justly so, I think. He was always doing a dozen things he need not have done. Still, unless we could command him, the whole official management of this craft would go by the board, or so we thought. Finally we decided to act, but how? Direct orders, somehow, were somewhat difficult to enforce. After due meditation we took the bos’n, a most approving officer and one who loved to tease Ike (largely because he wanted to feel superior himself, I think), into our confidence and one late afternoon just after Ike had, figuratively speaking, swabbed up the deck, the latter sent him to some other part of the shop, or vessel, rather, while we strewed shavings over his newly cleaned floor with a shameless and lavish hand. It was intensely delicious, causing gales of laughter at the time—but—. Ike came back and cleaned this up—not without a growl, however. He did not take it in the cheerful spirit in which we hoped he would. In fact he was very morose about it, calling us names and threatening to go to the foreman [in the lock-up] if we did it again. However, in spite of all, and largely because of the humorous spectacle he in his rage presented we did it not once, but three or four times and that after he had most laboriously cleaned his

room. A last assault one afternoon, however, resulted in a dash on his part to the foreman’s office.

“I’m not goin’ to stand it,” he is declared to have said by one who was by at the time when he appeared in front of that official. “They’re strewin’ up my floor with shavin’s two an’ three times every day after I’ve cleaned it up for the day. I’ll quit first.”

The foreman, that raw, non-humorous person previously described, who evidently sympathized with Ike and who, in addition, from various sources, had long since learned what was going on, came down in a trice. He had decided to stop this nonsense.

“I want you fellows to cut that out now,” he declared vigorously on seeing us. “It’s all right, but it won’t do. Don’t rub it in. Let him alone. I’ve heard of this ship stuff. It’s all damn nonsense.”

The captain and mate gazed at each other in sad solemnity Could it be that Ike had turned traitor? This was anarchy. He had not only complained of us but of the ship!—the Idlewild! What snakiness of soul! We retired to a corner of our now storm-tossed vessel and consulted in whispers. What would we do? Would we let her sink or try to save her? Perhaps it was advisable for the present to cease pushing the joke too far in that quarter, anyhow. Ike might cause the whole ship to be destroyed.

Nevertheless, even yet there were ways and ways of keeping her afloat and punishing an insubordinate even when no official authority existed. Ike had loved the engine-room, or rather, the captain’s office, above all other parts of the vessel because it was so comfortable. Here between tedious moments of pounding iron for the smith or blowing the bellows or polishing various tools that had been sharpened, he could retire on occasion, when the boss was not about and the work not pressing (it was the very next room to his) and gaze from the captain’s door or window out on the blue waters of the Hudson where lay the yachts, and up the same stream where stood the majestic palisades. At noon or a little before he could bring his cold coffee, sealed in a tin can, to the captain’s engine and warm it. Again, the captain’s comfortable locker held his coat and hat, the captain’s wash bowl—a large wooden tub to one side of the engine

into which comforting warm water could be drawn—served as an ideal means of washing up. Since the bos’n’s mate had become friendly with the captain, he too had all these privileges. But now, in view of his insubordination, all this was changed. Why should a rebellious bos’n’s mate be allowed to obtain favors of the captain? More in jest than in earnest one day it was announced that unless the bos’n’s mate would forego his angry opposition to a less early scrubbed deck——

“Well, mate,” the captain observed to the latter in the presence of the bos’n’s mate, with a lusty wink and a leer, “you know how it goes with these here insubordinates, don’t you? No more hot coffee at noon time, unless there’s more order here. No more cleanin’ up in the captain’s tub. No more settin’ in the captain’s window takin’ in the cool mornin’ breeze, as well as them yachts. What say? Eh? We know what to do with these here now insubordinates, don’t we, mate, eh?” This last with a very huge wink.

“You’re right, Captain. Very right,” the mate replied. “You’re on the right track now. No more favors—unless—— Order must be maintained, you know.”

“Oh, all right,” replied little Ike now, fully in earnest and thinking we were. “If I can’t, I can’t. Jist the same I don’t pick up no shavin’s after four,” and off he strolled.

Think of it, final and complete mutiny, and there was nothing more really to be done.

All we could do now was to watch him as he idled by himself at odd free moments down by the waterside in an odd corner of the point, a lonely figure, his trousers and coat too large, his hands and feet too big, his yellow teeth protruding. No one of the other workingmen ever seemed to be very enthusiastic over Ike, he was so small, so queer; no one, really, but the captain and the mate, and now they had deserted him.

It was tough.

Yet still another ill descended on us before we came to the final loss, let us say, of the good craft Idlewild In another evil hour the

captain and the mate themselves fell upon the question of priority, a matter which, so long as they had had Ike to trifle with, had never troubled them. Now as mate and the originator of this sea-going enterprise, I began to question the authority of the captain himself occasionally, and to insist on sharing as my undeniable privilege all the dignities and emoluments of the office—to wit: the best seat in the window where the wind blew, the morning paper when the boss was not about, the right to stand in the doorway, use the locker, etc. The captain objected, solely on the ground of priority, mind you, and still we fell a-quarreling. The mate in a stormy, unhappy hour was reduced by the captain to the position of mere scullion, and ordered, upon pain of personal assault, to vacate the captain’s cabin. The mate reduced the captain to the position of stoker and stood in the doorway in great glee while the latter, perforce, owing to the exigencies of his position, was compelled to stoke whether he wanted to or no. It could not be avoided. The engine had to be kept going. In addition, the mate had brought many morning papers, an occasional cigar for the captain, etc. There was much rancor and discord and finally the whole affair, ship, captain, mate and all, was declared by the mate to be a creation of his brain, a phantom, no less, and that by his mere act of ignoring it the whole ship—officers, men, masts, boats, sails—could be extinguished, scuttled, sent down without a ripple to that limbo of seafaring men, the redoubtable Davy Jones’s locker.

The captain was not inclined to believe this at first. On the contrary, like a good skipper, he attempted to sail the craft alone. Only, unlike the mate, he lacked the curious faculty of turning jest and fancy into seeming fact. There was a something missing which made the whole thing seem unreal. Like two rival generals, we now called upon a single army to follow us individually, but the crew, seeing that there was war in the cabin, stood off in doubt and, I fancy, indifference. It was not important enough in their hardworking lives to go to the length of risking the personal ill-will of either of us, and so for want of agreement, the ship finally disappeared.

Yes, she went down. The Idlewild was gone, and with her, all her fine seas, winds, distant cities, fogs, storms.

For a time indeed, we went charily by each other

Still it behooved us, seeing how, in spite of ourselves, we had to work in the same room and there was no way of getting rid of each other’s obnoxious presence, to find a common ground on which we could work and talk. There had never been any real bitterness between us—just jest, you know, but serious jest, a kind of silent sorrow for many fine things gone. Yet still that had been enough to keep everything out of order. Now from time to time each of us thought of restoring the old life in some form, however weak it might be. Without some form of humor the shop was a bore to the mate and the captain, anyhow. Finally the captain sobering to his old state, and the routine work becoming dreadfully monotonous, both mate and captain began to think of some way in which they, at least, could agree.

“Remember the Idlewild, Henry?” asked the ex-captain one day genially, long after time and fair weather had glossed over the wretched memory of previous quarrels and dissensions.

“That I do, John,” I replied pleasantly.

“Great old boat she was, wasn’t she, Henry?”

“She was, John.”

“An’ the bos’n’s mate, he wasn’t such a bad old scout, was he, Henry, even if he wouldn’t quit sweepin’ up the shavin’s?”

“He certainly wasn’t, John. He was a fine little fellow. Remember the chains, John?”

“Haw! Haw!” echoed that worthy, and then, “Do you think the old Idlewild could ever be found where she’s lyin’ down there on the bottom, mate?”

“Well, she might, Captain, only she’d hardly be the same old boat that she was now that she’s been down there so long, would she— all these dissensions and so on? Wouldn’t it be easier to build a new one—don’t you think?”

“I don’t know but what you’re right, mate. What’d we call her if we did?”

“Well, how about the Harmony, Captain? That sounds rather appropriate, doesn’t it?”

“The Harmony, mate? You’re right—the Harmony Shall we? Put ’er there!”

“Put her there,” replied the mate with a will. “We’ll organize a new crew right away, Captain—eh, don’t you think?”

“Right! Wait, we’ll call the bos’n an’ see what he says.”

Just then the bos’n appeared, smiling goodnaturedly.

“Well, what’s up?” he inquired, noting our unusually cheerful faces, I presume. “You ain’t made it up, have you, you two?” he exclaimed.

“That’s what we have, bos’n, an’ what’s more, we’re thinkin’ of raisin’ the old Idlewild an’ re-namin’ her the Harmony, or, rather, buildin’ a new one. What say?” It was the captain talking.

“Well, I’m mighty glad to hear it, only I don’t think you can have your old bos’n’s mate any longer, boys. He’s gonna quit.”

“Gonna quit!” we both exclaimed at once, and sadly, and John added seriously and looking really distressed, “What’s the trouble there? Who’s been doin’ anything to him now?” We both felt guilty because of our part in his pains.

“Well, Ike kind o’ feels that the shop’s been rubbin’ it into him of late for some reason,” observed the bos’n heavily. “I don’t know why. He thinks you two have been tryin’ to freeze him out, I guess. Says he can’t do anything any more, that everybody makes fun of him and shuts him out.”

We stared at each other in wise illumination, the new captain and the new mate. After all, we were plainly the cause of poor little Ike’s depression, and we were the ones who could restore him to favor if we chose. It was the captain’s cabin he sighed for—his old pleasant prerogatives.

“Oh, we can’t lose Ike, Captain,” I said. “What good would the Harmony be without him? We surely can’t let anything like that happen, can we? Not now, anyhow.”

“You’re right, mate,” he replied. “There never was a better bos’n’s mate, never. The Harmony’s got to have ’im. Let’s talk reason to him, if we can.”

In company then we three went to him, this time not to torment or chastise, but to coax and plead with him not to forsake the shop, or the ship, now that everything was going to be as before—only better —and——

Well, we did.

MARRIED

I� connection with their social adjustment, one to the other, during the few months they had been together, there had occurred a number of things which made clearer to Duer and Marjorie the problematic relationship which existed between them, though it must be confessed it was clearer chiefly to him. The one thing which had been troubling Duer was not whether he would fit agreeably into her social dreams—he knew he would, so great was her love for him— but whether she would fit herself into his. Of all his former friends, he could think of only a few who would be interested in Marjorie, or she in them. She cared nothing for the studio life, except as it concerned him, and he knew no other

Because of his volatile, enthusiastic temperament, it was easy to see, now that she was with him constantly, that he could easily be led into one relationship and another which concerned her not at all. He was for running here, there, and everywhere, just as he had before marriage, and it was very hard for him to see that Marjorie should always be with him. As a matter of fact, it occurred to him as strange that she should want to be. She would not be interested in all the people he knew, he thought. Now that he was living with her and observing her more closely, he was quite sure that most of the people he had known in the past, even in an indifferent way, would not appeal to her at all.

Take Cassandra Draper, for instance, or Neva Badger, or Edna Bainbridge, with her budding theatrical talent, or Cornelia Skiff, or Volida Blackstone—any of these women of the musical art-studio world with their radical ideas, their indifference to appearances, their semisecret immorality. And yet any of these women would be glad to see him socially, unaccompanied by his wife, and he would be glad to see them. He liked them. Most of them had not seen Marjorie, but, if they had, he fancied that they would feel about her much as he did —that is, that she did not like them, really did not fit with their world.

She could not understand their point of view, he saw that. She was for one life, one love. All this excitement about entertainment, their gathering in this studio and that, this meeting of radicals and models and budding theatrical stars which she had heard him and others talking about—she suspected of it no good results. It was too feverish, too far removed from the commonplace of living to which she had been accustomed. She had been raised on a farm where, if she was not actually a farmer’s daughter, she had witnessed what a real struggle for existence meant.

Out in Iowa, in the neighborhood of Avondale, there were no artists, no models, no budding actresses, no incipient playwrights, such as Marjorie found here about her. There, people worked, and worked hard. Her father was engaged at this minute in breaking the soil of his fields for the spring planting—an old man with a white beard, an honest, kindly eye, a broad, kindly charity, a sense of duty. Her mother was bending daily over a cook-stove, preparing meals, washing dishes, sewing clothes, mending socks, doing the thousand and one chores which fall to the lot of every good housewife and mother. Her sister Cecily, for all her gaiety and beauty, was helping her mother, teaching school, going to church, and taking the commonplace facts of mid-Western life in a simple, good-natured unambitious way. And there was none of that toplofty sense of superiority which marked the manner of these Eastern upstarts.

Duer had suggested that they give a tea, and decided that they should invite Charlotte Russell and Mildred Ayres, who were both still conventionally moral in their liberalism; Francis Hatton, a young sculptor, and Miss Ollie Stearns, the latter because she had a charming contralto voice and could help them entertain. Marjorie was willing to invite both Miss Russell and Miss Ayres, not because she really wanted to know either of them but because she did not wish to appear arbitrary and especially contrary. In her estimation, Duer liked these people too much. They were friends of too long standing. She reluctantly wrote them to come, and because they liked Duer and because they wished to see the kind of wife he had, they came.

There was no real friendship to be established between Marjorie and Miss Ayres, however, for their outlook on life was radically

different, though Miss Ayres was as conservative as Marjorie in her attitude, and as set in her convictions. But the latter had decided, partly because Duer had neglected her, partly because Marjorie was the victor in this contest, that he had made a mistake; she was convinced that Marjorie had not sufficient artistic apprehension, sufficient breadth of outlook, to make a good wife for him. She was charming enough to look at, of course, she had discovered that in her first visit; but there was really not enough in her socially, she was not sufficiently trained in the ways of the world, not sufficiently wise and interesting to make him an ideal companion. In addition she insisted on thinking this vigorously and, smile as she might and be as gracious as she might, it showed in her manner. Marjorie noticed it. Duer did, too. He did not dare intimate to either what he thought, but he felt that there would be no peace. It worried him, for he liked Mildred very much; but, alas! Marjorie had no good to say of her.

As for Charlotte Russell, he was grateful to her for the pleasant manner in which she steered between Scylla and Charybdis. She saw at once what Marjorie’s trouble was, and did her best to allay suspicions by treating Duer formally in her presence. It was “Mr. Wilde” here and “Mr. Wilde” there, with most of her remarks addressed to Marjorie; but she did not find it easy sailing, after all. Marjorie was suspicious. There was none of the old freedom any more which had existed between Charlotte and Duer. He saw, by Marjorie’s manner, the moment he became the least exuberant and free that it would not do. That evening he said, forgetting himself:

“Hey, Charlotte, you skate! Come over here. I want to show you something.”

He forgot all about it afterward, but Marjorie reminded him.

“Honey,” she began, when she was in his arms before the fire, and he was least expecting it, “what makes you be so free with people when they call here? You’re not the kind of man that can really afford to be free with any one. Don’t you know you can’t? You’re too big; you’re too great. You just belittle yourself when you do it, and it makes them think that they are your equal when they are not.”

“Who has been acting free now?” he asked sourly, on the instant, and yet with a certain make-believe of manner, dreading the storm of feeling, the atmosphere of censure and control which this remark forboded.

“Why, you have!” she persisted correctively, and yet apparently mildly and innocently. “You always do. You don’t exercise enough dignity, dearie. It isn’t that you haven’t it naturally—you just don’t exercise it. I know how it is; you forget.”

Duer stirred with opposition at this, for she was striking him on his tenderest spot—his pride. It was true that he did lack dignity at times. He knew it. Because of his affection for the beautiful or interesting things—women, men, dramatic situations, songs, anything—he sometimes became very gay and free, talking loudly, using slang expressions, laughing boisterously. It was a failing with him, he knew. He carried it to excess at times. His friends, his most intimate ones in the musical profession had noted it before this. In his own heart he regretted these things afterward, but he couldn’t help them, apparently. He liked excitement, freedom, gaiety—naturalness, as he called it—it helped him in his musical work, but it hurt him tremendously if he thought that any one else noticed it as out of the ordinary. He was exceedingly sensitive, and this developing line of criticism of Marjorie’s was something new to him. He had never noticed anything of that in her before marriage.

Up to the time of the ceremony, and for a little while afterward, it had appeared to him as if he were lord and master. She had always seemed so dependent on him, so anxious that he should take her. Why, her very life had been in his hands, as it were, or so he had thought! And now—he tried to think back over the evening and see what it was he had done or said, but he couldn’t remember anything. Everything seemed innocent enough. He couldn’t recall a single thing, and yet——

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he replied sourly, withdrawing into himself. “I haven’t noticed that I lack dignity so much. I have a right to be cheerful, haven’t I? You seem to be finding a lot that’s wrong with me.”

“Now please don’t get angry, Duer,” she persisted, anxious to apply the corrective measure of her criticism, but willing, at the same time, to use the quickness of his sympathy for her obvious weakness and apparent helplessness to shield herself from him. “I can’t ever tell you anything if you’re going to be angry. You don’t lack dignity generally, honey-bun! You only forget at times. Don’t you know how it is?”

She was cuddling up to him, her voice quavering, her hand stroking his cheek, in a curious effort to combine affection and punishment at the same time. Duer felt nothing but wrath, resentment, discouragement, failure.

“No, I don’t,” he replied crossly. “What did I do? I don’t recall doing anything that was so very much out of the way.”

“It wasn’t that it was so very much, honey; it was just the way you did it. You forget, I know. But it doesn’t look right. It belittles you.”

“What did I do?” he insisted impatiently.

“Why, it wasn’t anything so very much. It was just when you had the pictures of those new sculptures which Mr. Hatton lent you, and you were showing them to Miss Russell. Don’t you remember what you said—how you called her over to you?”

“No,” he answered, having by now completely forgotten. He was thinking that accidentally he might have slipped his arm about Charlotte, or that he might have said something out of the way jestingly about the pictures; but Marjorie could not have heard. He was so careful these days, anyway.

“Why, you said: ‘Hey, Charlotte, you skate! Come over here.’ Now, what a thing to say to a girl! Don’t you see how ugly it sounds, how vulgar? She can’t enjoy that sort of remark, particularly in my presence, do you think? She must know that I can’t like it, that I’d rather you wouldn’t talk that way, particularly here. And if she were the right sort of girl she wouldn’t want you to talk to her at all that way. Don’t you know she wouldn’t? She couldn’t. Now, really, no good woman would, would she?”

Duer flushed angrily Good heaven! Were such innocent, simple things as this to be made the subject of comment and criticism! Was his life, because of his sudden, infatuated marriage, to be pulled down to a level he had never previously even contemplated? Why— why—This catechising, so new to his life, so different to anything he had ever endured in his youth or since, was certain to irritate him greatly, to be a constant thorn in his flesh. It cut him to the core. He got up, putting Marjorie away from him, for they were sitting in a big chair before the fire, and walked to the window.

“I don’t see that at all,” he said stubbornly. “I don’t see anything in that remark to raise a row about. Why, for goodness’ sake! I have known Charlotte Russell—for years and years, it seems, although it has only been a little while at that. She’s like a sister to me. I like her. She doesn’t mind what I say. I’d stake my life she never thought anything about it. No one would who likes me as well as she does. Why do you pitch on that to make a fuss about, for heaven’s sake?”

“Please don’t swear, Duer,” exclaimed Marjorie anxiously, using this expression for criticising him further. “It isn’t nice in you, and it doesn’t sound right toward me. I’m your wife. It doesn’t make any difference how long you’ve known her; I don’t think it’s nice to talk to her in that way, particularly in my presence. You say you’ve known her so well and you like her so much. Very well. But don’t you think you ought to consider me a little, now that I’m your wife? Don’t you think that you oughtn’t to want to do anything like that any more, even if you have known her so well—don’t you think? You’re married now, and it doesn’t look right to others, whatever you think of me. It can’t look right to her, if she’s as nice as you say she is.”

Duer listened to this semipleading, semichastising harangue with disturbed, opposed, and irritated ears. Certainly, there was some truth in what she said; but wasn’t it an awfully small thing to raise a row about? Why should she quarrel with him for that? Couldn’t he ever be lightsome in his form of address any more? It was true that it did sound a little rough, now that he thought of it. Perhaps it wasn’t exactly the thing to say in her presence, but Charlotte didn’t mind. They had known each other much too long. She hadn’t noticed it one way or the other; and here was Marjorie charging him with being

vulgar and inconsiderate, and Charlotte with being not the right sort of girl, and practically vulgar, also, on account of it. It was too much. It was too narrow, too conventional. He wasn’t going to tolerate anything like that permanently.

He was about to say something mean in reply, make some cutting commentary, when Marjorie came over to him. She saw that she had lashed him and Charlotte and his generally easy attitude pretty thoroughly, and that he was becoming angry. Perhaps, because of his sensitiveness, he would avoid this sort of thing in the future. Anyhow, now that she had lived with him four months, she was beginning to understand him better, to see the quality of his moods, the strength of his passions, the nature of his weaknesses, how quickly he responded to the blandishments of pretended sorrow, joy, affection, or distress. She thought she could reform him at her leisure. She saw that he looked upon her in his superior way as a little girl—largely because of the size of her body. He seemed to think that, because she was little, she must be weak, whereas she knew that she had the use and the advantage of a wisdom, a tactfulness and a subtlety of which he did not even dream. Compared to her, he was not nearly as wise as he thought, at least in matters relating to the affections. Hence, any appeal to his sympathies, his strength, almost invariably produced a reaction from any antagonistic mood in which she might have placed him. She saw him now as a mother might see a great, overgrown, sulking boy, needing only to be coaxed to be brought out of a very unsatisfactory condition, and she decided to bring him out of it. For a short period in her life she had taught children in school, and knew the incipient moods of the race very well.

“Now, Duer,” she coaxed, “you’re not really going to be angry with me, are you? You’re not going to be ‘mad to me’?” (imitating childish language).

“Oh, don’t bother, Marjorie,” he replied distantly. “It’s all right. No; I’m not angry. Only let’s not talk about it any more.”

“You are angry, though, Duer,” she wheedled, slipping her arm around him. “Please don’t be mad to me. I’m sorry now. I talk too

much. I get mad. I know I oughtn’t. Please don’t be mad at me, honey-bun. I’ll get over this after a while. I’ll do better. Please, I will. Please don’t be mad, will you?”

He could not stand this coaxing very long. Just as she thought, he did look upon her as a child, and this pathetic baby-talk was irresistible. He smiled grimly after a while. She was so little. He ought to endure her idiosyncrasies of temperament. Besides, he had never treated her right. He had not been faithful to his engagement-vows. If she only knew how bad he really was!

Marjorie slipped her arm through his and stood leaning against him. She loved this tall, slender distinguished-looking youth, and she wanted to take care of him. She thought that she was doing this now, when she called attention to his faults. Some day, by her persistent efforts maybe, he would overcome these silly, disagreeable, offensive traits. He would overcome being undignified; he would see that he needed to show her more consideration than he now seemed to think he did. He would learn that he was married. He would become a quiet, reserved, forceful man, weary of the silly women who were buzzing round him solely because he was a musician and talented and good-looking, and then he would be truly great. She knew what they wanted, these nasty women—they would like to have him for themselves. Well, they wouldn’t get him. And they needn’t think they would. She had him. He had married her. And she was going to keep him. They could just buzz all they pleased, but they wouldn’t get him. So there!

There had been other spats following this—one relating to Duer not having told his friends of his marriage for some little time afterward, an oversight which in his easy going bohemian brain augured no deep planted seed of disloyalty, but just a careless, indifferent way of doing things, whereas in hers it flowered as one of the most unpardonable things imaginable! Imagine any one in the Middle West doing anything like that—any one with a sound, sane conception of the responsibilities and duties of marriage, its inviolable character! For Marjorie, having come to this estate by means of a hardly won victory, was anxious lest any germ of inattentiveness, lack of consideration, alien interest, or affection

flourish and become a raging disease which would imperil or destroy the conditions on which her happiness was based. After every encounter with Miss Ayres, for instance, whom she suspected of being one of his former flames, a girl who might have become his wife, there were fresh charges to be made. She didn’t invite Marjorie to sit down sufficiently quickly when she called at her studio, was one complaint; she didn’t offer her a cup of tea at the hour she called another afternoon, though it was quite time for it. She didn’t invite her to sing or play on another occasion, though there were others there who were invited.

“I gave her one good shot, though,” said Marjorie, one day, to Duer, in narrating her troubles. “She’s always talking about her artistic friends. I as good as asked her why she didn’t marry, if she is so much sought after.”

Duer did not understand the mental sword-thrusts involved in these feminine bickerings. He was likely to be deceived by the airy geniality which sometimes accompanied the bitterest feeling. He could stand by listening to a conversation between Marjorie and Miss Ayres, or Marjorie and any one else whom she did not like, and miss all the subtle stabs and cutting insinuations which were exchanged, and of which Marjorie was so thoroughly capable. He did not blame her for fighting for herself if she thought she was being injured, but he did object to her creating fresh occasions, and this, he saw, she was quite capable of doing. She was constantly looking for new opportunities to fight with Mildred Ayres and Miss Russell or any one else whom she thought he truly liked, whereas with those in whom he could not possibly be interested she was genial (and even affectionate) enough. But Duer also thought that Mildred might be better engaged than in creating fresh difficulties. Truly, he had thought better of her. It seemed a sad commentary on the nature of friendship between men and women, and he was sorry.

But, nevertheless, Marjorie found a few people whom she felt to be of her own kind. M. Bland, who had sponsored Duer’s first piano recital a few months before, invited Duer and Marjorie to a—for them —quite sumptuous dinner at the Plaza, where they met Sydney Borg, the musical critic of an evening paper; Melville Ogden Morris,

curator of the Museum of Fine Arts, and his wife; Joseph Newcorn, one of the wealthy sponsors of the opera and its geniuses, and Mrs. Newcorn. Neither Duer nor Marjorie had ever seen a private diningroom set in so scintillating a manner. It fairly glittered with Sèvres and Venetian tinted glass. The wine-goblets were seven in number, set in an ascending row. The order of food was complete from Russian caviare to dessert, black coffee, nuts, liqueurs, and cigars.