FormySheriff

Copyright © 2019 by

Kylie Marcus

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For information contact: authorkyliemarcus@gmail.com

Book and Cover design by Free To Be Creative Co.

ISBN: 978-1-988662-16-9

First Edition: November 2019

1. Chapter One

2. Chapter Two

3. Chapter Three

4. Chapter Four

5. Chapter Five

6. Chapter Six

7. Chapter Seven

8. Chapter Eight

9. Chapter Nine

10. Chapter Ten

11. Chapter Eleven

12. Chapter Twelve

13. Chapter Thirteen

14. Chapter Fourteen

15. Chapter Fifteen

16. Chapter Sixteen

17. Chapter Seventeen

18. Chapter Eighteen

19. Chapter Nineteen

20. Chapter Twenty

Afterword

About the Author

Also by Kylie

Marcus

CONTENTS

C H A P T E R O N E

The mattress creaked as I rolled over, and suddenly my entire body filled with tension as I froze, holding my breath and waiting. Another soft sigh escaped from beside me, followed by a loud intake resulting in a snore, and I exhaled again. Moving more carefully this time, I shifted my legs off the bed and rose, squeezing my eyes shut and hoping that the floor didn’t groan under my weight.

When I was sure no other unexpected or unwelcome noises would announce themselves, I risked moving my other foot and slowly crept toward the door. I was too scared to even look back over my shoulder at the mass in the bed beside me.

I would look back when I was free.

At the door, I grimaced and reached out, pressing down the lock on the door and easing it open with a painful slowness that would have driven me mad in any other situation. But it was worth it. The door opened without trouble, and I slipped through, glancing back now to make sure he was still sleeping.

With a sigh, I closed the door just as carefully and then stood there for a second, relishing my freedom.

I had been here, at Bluebeard’s manor, for a week now. Sleeping beside him, under his watchful gaze during the day, and when he did occasionally leave, he left his housekeeper on constant vigilance. I knew that old creep was reporting back my every movement to him when he returned.

So, I kept to myself and played along. Most days, I sat in the aviary, making friends with the others trapped here like myself. But the birds didn’t talk back to me, as much as I wished they did.

It turned out that at least one theory the boys and I had come up with about my magic was right. Either I was weakened because I had none of the books or because I was the main character now in Bluebeard’s tale. Whatever the reason, I was useless. There wasn’t a lick of magic in me, and trust me, I had tried.

But at night, when Bluebeard and his housekeeper slept, I took the time to explore and plot. I knew I needed a plan if I was going to escape, but I also couldn’t risk him knowing about what I was up to. So, I waited until he was deep in sleep and snuck out. Every night I explored more of the manor, looking for something, anything, that might help me get out of here and get back to the Academy.

This place was creepy enough in the daytime, but at night, when shadows descended, and the light was scarce, it was even creepier. My paranoia seemed to peak during this time, every noise had me turning around to look over my shoulder. I could swear I heard something following me, but every time I looked, there was nothing.

“Pull it together, Serina,” I whispered to myself as I continued down the vast staircase toward the basement. After a week of midnight creepings, this was the last place I hadn’t explored. I could only hope there was a secret exit down here that he used to come and go. Perhaps an old tunnel that came out in the woods, far from this place, and giving me a small head start.

I had to admit that the last week had only helped my imagination as I tried to consider every possibility hoping one of my imaginings was real.

So far, I found nothing.

I gripped the stone railing as I descended the last set of stairs, the floor damp underfoot, making the descent more treacherous than expected. At the bottom, there seemed to be a void of light as I squinted, desperately hoping my eyes would adjust. As I moved further in with cautious steps, a sconce to my right lit suddenly in a small explosion of light. I gasped, jumping in fright away from it.

My heart was pounding in my chest as I stared and hoped that whatever magic had sensed me, turning the light on hadn’t also alerted Bluebeard to the fact I was down here sneaking around. I stood there, tense, and waiting for any sign that my captor was coming. After what felt like an eternity, I was sure that the lights were just that - lights and not a complex, magical security system. With renewed confidence, I made my way further down the hall. I found that every step further into the darkness triggered the candles in the scones, slowly lighting my way.

Buttowhat?

I slowed at the first door I found, carefully opening it, not knowing what to expect. A cold cellar, however, wasn’t on my mind. I looked over at the preserves lining the walls before my eyes jumped to a carcass hanging at the back. It was shrouded in a white sheet. I couldn’t tell what kind of animal it was, but for the last week our diet mostly consisted of chicken and venison. It had to be a deer; I decided.

Backing out, I closed the door again and continued down the hallway further until I reached another door. Thelastdoor .

The hallway abruptly ended with nothing more than this door ahead of me as an option. My heart sped up slightly, maybe my hope of a secret tunnel was about to come true. I reached for the handle, my hands damp with anxiety and shaking in fear? Excitement? I didn’t know.

But it was all for nothing as I grabbed the latch, pushed it down, and found the door locked. I tried again, and then as desperation set in, I tried harder, shaking the door foolishly to dislodge the lock. Even though I knew it was useless.

“What are you doing down here?”

I screamed, releasing the door as I turned around and plastered myself against the door, finding the housekeeper standing there with that signature scowl on his face.

“I was…” I scrambled, searching my mind for a believable excuse that would keep me out of trouble. “I was sleepwalking… I mean, I think I was. How did I get here?” I looked around vaguely, acting

like I had no idea where I was or how I got there. I didn’t know if he believed me, his facial expressions gave nothing away.

“You’re not supposed to be down here.” He grabbed my wrist and roughly pulled me away from the door, dragging me back down the hall. Like someone was flipping the switch, the lights in the scones went out as we passed them again, and darkness descended on the mysterious door behind me. A door they didn’t want me to go through.

Hope soared through me; that had to be my way out. I was sure of it.

“I’m sorry,” I muttered, hoping my patheticness was believable. I wanted them to think I was weak. I couldn’t afford to have them on guard around me.

The housekeeper dragged me all the way back up to the bedroom, knocked on the door, and woke Bluebeard. I cringed as I listened to the noises behind the door. My captor inevitably realizing I wasn’t in bed next to him, that someone was at the door and that, likely, it had something to do with my disappearance.

The door opened slowly, and the towering figure of the older man appeared, his intimidating stature making me shrink instinctively.

“I found her in the basement. She claims she was sleepwalking.”

“I was,” I blurted, glancing over at the housekeeper. “I didn’t even know where I was until he woke me. You know, you’re not supposed to wake a sleepwalker. You can do a lot of damage.”

He snorted like he didn’t believe me before turning back to his master. “Should I punish her?”

“No, Lamont, that’s fine. I can take it from here. Thank you.” He took me by the hand and gently pulled me toward him, closing the door in Lamont’s face without another word.

Now that we were alone, he didn’t move. He only stared down at me like he was trying to decide if I was telling the truth or not. Bluebeard didn’t say much to me, we lived in a strange silence that spoke louder than any words he had yet to say to me. He didn’t present himself as an angry man, but there was something in the way he moved and spoke that hinted at a violence that lingered

under the surface. It was waiting to boil over, like a volcano, when the time came that I pushed him too far. That scared me more than anything. Angry, I could handle. I could also maneuver around controlling. But unpredictable? That was scary. That was just like my mother.

Of course, she would send me to someone like her. She probably thought this was how she could control me. But she also didn’t know that the Storybook Realm had changed me. I was different now. Even Geni had said so. I wasn’t the small, scared little girl I used to be. My magic and my boys had helped me change. I was a fighter because I was a believer.

He finally let go of my hand, running his hand down the side of my head before he gently tucked my hair behind my ear. I shivered, remembering when one of the boys did it, but this time, the gesture wasn’t endearing. Instead, there was a soft threat in the motion. He was petting me, but he could be hurting me if he wanted to.

“You must not go down to the basement, my love.” He said with a sigh, “I have given you freedom in my household that is unprecedented, and my only wish is that you keep to the main floors. There is no need for you to go down there, so you will not. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, sir.” My eyes jumped to the floor, playing the role of the docile young woman. That’s what he wanted, after all.

“Yes, what?”

I cringed, looking back up at him and trying to smile sweetly, although I was sure it came off like more of a grimace. “Yes, my husband.”

“Good, now, let’s go back to bed.” He waited for me to take the lead, and I finally made my way to the door, slipping back into bed. I shivered, not because I was cold, but as the anxiety in my stomach flooded the rest of my stomach. So far, we only shared a bed because I was sure he wanted to keep an eye on me at all times. But I knew as that wedding date he had chosen loomed closer, that would change one night.

And I needed to get the hell out of here before that happened.

C H A P T E R T W O

We didn’t speak the next morning as we got dressed. No words were exchanged as we took our breakfast across from each other at the massive dining table. Even as he kissed the top of my head before excusing himself to go and do whatever it was he did during the day, there was silence.

Lamont watched me as I finished the last of my eggs and set my fork down. He didn’t trust me, he probably didn’t believe me either. I might fool Bluebeard, but it would be much harder to convince his housekeeper I was harmless.

Pushing my chair out, I rose and walked past him, heading for the aviary. As I went past, my eyes jumped to his waist, where a ring of keys hung. I would bet my life that, on that keyring, he had something to open that basement door. I just needed to get that key off him. It was my only chance since Bluebeard wore his skeleton key on a necklace that he never took off.

The aviary was warm. He kept tropical birds from what I could tell, and I liked it in here because of that. The rest of the manor was drafty and cold. Even at night, under several layers of furs, I couldn’t thoroughly shake the dampness from my body. But here, amongst these other hostages, I warmed up.

Settling on the bench I had claimed as my own, I pulled my book up from behind the bench and flipped it open to where I last left off. It was a horticulture book suggested to me by Bluebeard. He caught on quickly enough that I liked it in here. So he had recommended I

familiarize myself with the varieties of birds and plants and even offered to get me anything I might wish to add to the room.

I couldn’t tell if it was a gesture of goodwill or something sinister since I found most of the plants he kept in here had some kind of poisonous property. I figured this was probably his sly way of telling me to watch myself, he could quickly get rid of me, and I’d never know. But then, knowing what I did now, I could say the same to him too.

“I wouldn’t go down there again.” I tensed on the bench, my fingers tightening around the book in my hands as I worked up the courage to look up. I didn’t know that voice, but I was sure there was no one else here in the manor with us.

And a quick glance around confirmed that for me. There was no one in the aviary with me.

“Who are you? Show yourself.”

Nothing happened, no one appeared, and I stood up, brandishing the book like a weapon.

“When they go down there, they never come back.”

“What?” I turned around, trying to follow the sound of the voice. “Who?”

“The other brides.”

The words echoed around me, and it felt like someone had dropped a bucket of ice-cold water over me. A bird flew overhead, and I jumped instinctively, looking up.

“I’ve never seen one come back. And I’ve been here a while.” The voice came from directly behind me, and that icy cold feeling seemed to double. My entire body resisted the act of turning around, but my curiosity was stronger. As I glanced over my shoulder, I stared in surprise at a bird sitting on the back of the bench, just staring at me. Like a human would.

“You’re talking,” I said stupidly, and then I remembered the squirrels, and my toad professor, Mother Goose, the list went on. Was I really that surprised that Bluebeard had a talking bird?

“I am,” he said in a bored tone, lifting a massive claw off the bench and scratching himself.

“There were other brides?”

“There have been many brides.” He drawled, looking over me. “You’re younger than usual, but not unusual.”

“When you said the other brides don’t come back, what do you mean?”

“They go to the basement too, and they don’t come back.”

“Like, they escape?” I asked, trying not to sound too hopeful. And I shouldn’t have because the bird shook its head.

“No, they go down there, and they go nowhere ever again.”

“They die?” He nodded his head again, and I sat down, avoiding his body as I leaned back on the bench. Now everything made sense. A black widow fairy tale character, but in reverse. My mother sent me here to get rid of me. She expected that I wouldn’t survive whatever bloodlust Bluebeard might have.

“I wouldn’t eat the meat either.”

“What?” I said in alarm, not wanting a reply because I could put together the pieces, and I immediately felt sick. “Oh God,” I cringed, holding my stomach as it turned over and over inside of me. “How long has this been going on?”

“As long as I’ve been here,” the bird said mildly.

“And how long is that?”

“I am three hundred and forty-seven years old.”

I was not expecting that. I turned back to the bird, staring him over and trying to figure out what species he was. I couldn’t recall any bird in the books who lived that long.

“I am a Phoenix.” He said as if he read my mind.

“You regenerate.” It nodded its head as he snapped his beak suddenly, catching one of the small songbirds that flew by in it and crunched down in boredom. I looked away, still feeling sick at the idea I may have been eating human all this time.

“This aviary isn’t because he likes birds, it’s for you.”

“This is my prison.” He agreed, looking back over at me as he swallowed the rest of his snack.

“Why though?”

“How else does a human live to be three hundred and seventyfour?”

“He’s using you to regenerate?”

“It can be done.” The bird agreed again, lifting his claw to its beak and digging at it for a moment. It chomped again and resettled on the bench.

“And the brides, what are they for?”

“The spell, otherwise he would regenerate at his current appearance.”

“So, he kills young girls and uses their blood to turn back the clocks on his own aging?”

“Yes,” the bird said as he cracked his neck. I still felt horrified by all this new information. Yet, as I processed it, I began to realize something that perhaps my mother had overlooked in sending me here. It could be as simple as she didn’t know that Bluebeard had a talking phoenix. Or maybe she was so blinded by her power and pursuit of it she hadn’t even considered the possibility. Either way, whatever the reason, there was hope. And with hope, magic could happen.

“I don’t suppose, in your three hundred years of watching Bluebeard abuse your magic and murder his brides you’ve noticed a… pattern. Perhaps the same girls began to appear every hundred years or so?”

The bird turned slowly and looked at me, its eyes narrowing as he tried to figure out what I was up to.

“I guess, what I’m asking, is if your memory is spotty?”

“Absolutely not, I am as sharp as I was the day I was first created as a hatchling.”

“Perhaps then, you remember the war.” The bird lifted its head a bit more like I intrigued it, and I took this as a clue to continue. “You remember when The Avarists and The Keepers battled, and it diluted the bloodlines, some even destroyed.”

“I remember, but it would seem no one else does. Except you.” He cocked his head to the side. “Why is that?”

I grinned brightly, hope flooding every vein. When they erased the memories, the magic must have targeted the humans only. Perhaps the characters of stories that were the main characters, but creatures who filled in the gaps and just existed, there would be no reason to erase their memories. An oversight by my mother, maybe

even my grandfather, but it might just be an oversight that would save my life.

“I am a descendant of a Keeper. I am a Keeper of the Stories.” I licked my lips, whispering the words in case Lamont was lingering nearby. “An Avarist trapped me and sent me here, perhaps to make me a victim of Bluebeard. But maybe you can help me. I don’t know this story. If you could tell it to me, maybe I could finish it and get my magic back. Then, once I’ve restored my powers, we can leave. Both of us.”

The bird eyed me suspiciously, and honestly, I couldn’t blame him. Three hundred years trapped with a villain, of course, he wouldn’t trust humans.

“It always happens at a party.”

“What happens at a party?”

“Bluebeard’s death. But he regenerates, because of me.”

“Okay, how does he ensure his regeneration?”

“He has a potion, made from my blood and the blood of his wives. He drinks it every night to ensure if something were to happen to him, he would come back.” Every night after dinner, Bluebeard drank a wine. Or at least, I had assumed it was a wine. It’s dark red color seemed like it was a full-bodied merlot, but maybe this was the potion.

“Okay, I think I know what that is. I can switch it. I think.” I couldn’t use my blood though, I still had Wulf’s werewolf gene in me. If he had my blood, he would transform, and then he would be able to more than just regenerate. He could heal himself too. No, I needed to get into that room where the other brides disappeared. Hopefully, that’s where he kept the supplies to make his potion. Then I could concoct something new to give him without him realizing I had removed the Phoenix’s blood from the recipe. “How does he die?”

“Alright, well, his death comes at the hands of the bride’s brother.”

“I don’t have a brother,” I frowned, looking away. I didn’t have anyone anymore. By now, all this time, I had wasted trying to escape this place, had given my mother and sister more than

enough time to unwrite my boys. No one was coming from me. But maybe there was someone else, a different hero, I could call for.

“How does the brother come to be here?”

“The night of the wedding, they have a party, and the bride’s family comes to celebrate. At this point, she has discovered his red room, and he plans on making her a permanent addition to it. But when he attacks her, her brother comes to her rescue and kills him.”

“I have to marry him.”

“That’s how the story goes.”

I sighed, looking away as I considered all this. I had changed other stories. Why couldn’t I change this one? There was nothing to say that I couldn’t rewrite a few minor aspects of the story. Like, say, this wedding ordeal. Perhaps an engagement party would work.

“Okay, I think I have an idea. But it means going down to that red room. Could you help me with that?”

“You have a death wish?” The bird asked sarcastically. I rolled my eyes. “No, but it’s the only way I will change the potion. It’s the only way to stop him from being able to regenerate.”

“I could get the keys, yes, but I really must advise against this.”

“I know, but we have no better option.” The bird nodded its head and then looked away.

“Come to me tonight. I’ll have the key.” He spread his wings out and stretched himself before rising and flying away. I had to hope that he wasn’t loyal to his master, that Bluebeard was holding him hostage. I needed to hope that by telling him everything I hadn’t just given myself away to a spy sent in to figure out what I was up to.

I closed the book in my lap and tucked it away again before rising to go. I needed to find Bluebeard and set everything in motion for the engagement party. This might be my only chance to get out of here. It would help if the bird knew the whole story by heart, but the basics would be enough to end the story and get my magic back.

It was simple; I had to kill my captor, or I would be magicless until the time came that he killed me instead.

C H A P T E R T H R E E

Iwalked by Lamont as I made my way through the manor toward the office I knew Bluebeard worked in throughout the day. His beady eyes followed me as I went by him, and something about the seedy little man made my skin crawl. The Phoenix had mentioned nothing about what to do with Lamont, which could be problematic.

I would have to ask him tonight if the housekeeper had any role in what was about to happen. And if he didn’t, I had to find out what happened to him too. I couldn’t risk any loose ends that might mean the story was incomplete, and my magic never returned.

I stopped outside of the office, pausing only for a moment before I finally found the nerve to knock. I was sure that my presence was surprising; this was the first time since arriving that I had come here.

“Come in.” His deep baritone echoed under the door, and I took a second to prepare myself before I grabbed the handle and pushed it open. He looked up from his desk, unable to school the expression of surprise as he saw me instead of Lamont. “My bride.” He rose from his desk, coming around it at the same time that I walked further into the room, and the door thudded shut behind me with an ominous clunk. “Please, sit.” He indicated toward two armchairs by the window, and I moved over, letting my eyes linger on the grounds of the manor and the dense fog that seemed to hang permanently over it.

He stepped closer to me, slipping down into his own chair and casually crossed one leg over the other as he leaned back in the chair with a sly grin. “To what do I owe this pleasure?”

“I’ve been thinking about our wedding,” I intoned, tearing my eyes away from the grounds to look at him. “I think I would feel more excited about it if we could celebrate our betrothal. Perhaps with a party? We could invite our nearest and dearest to celebrate our upcoming nuptials. It would also give me a chance to meet your friends before our wedding, too.”

He leaned further back in his chair thoughtfully, stroking his chin and everything, as he considered my offer.

“Is a wedding not celebration enough for a party?”

“Of course, but it is…” I paused, trying to come up with something that sounded believable, “it is a custom in my land to have a celebration of the couple’s betrothal before the ceremony itself. It’s an opportunity for the two families to come together, you see.”

“Ah, well, I guess I understand that.” He smiled at me in a way that I guessed he thought was kind and comforting, but all I could think about was dead girls, being eaten for dinner, and a potion made of blood. “If it would make you happy, my dear, then I see no reason we couldn’t host a party.”

I tried to look delighted in the way a vapid, young girl would and nodded my head in excitement. “Oh yes, it would. I love planning parties.”

The rouse seemed to work since he looked amused by my simplicity, and he nodded in agreement, “alright then, well, you are free to play your party. Just leave me a list of guests you wish to invite, and I’ll see that we invite them.”

I knew in all likelihood Philip, Aladdin, Adam, Erik, and Hans were gone. Still, I figured there couldn’t be any harm in asking for their presence on the off chance that with me out of the way, my mother and sister had taken their time in unwriting them. After all, compared to destroying the realm and amassing as much power for themselves as possible, how important was unwriting my boyfriends?

At least, I hoped that’s how they saw it.

“I will also send you a list of my wishes for the party; food and drinks, and such.”

“Sounds good, my dear.” He rose and walked back to his desk, silently dismissing me. Which was perfectly fine with me, the less time I had to spend with him better. Now I just needed to fill in the rest of my day and get to tonight as fast as possible. I felt more hopeful the more this plan began to shape up. It just might work. Although I still needed to figure out how I planned to have Bluebeard killed. Without a brother or any male companions, the role of the killer might just have to fall to me again.

I left his office and wandered back down the hall toward the stairs. I needed to come up with a believable list of people to ask him to invite. A group of characters that wouldn’t look suspicious at first glance and that he wouldn’t question. I would not ask my family, chances were if they came they would spoil my story. I knew the reason I was here had everything to do with the fact my mother and sister knew the story of Bluebeard and not because it was just a chance opportunity for them.

So, I spent the rest of the afternoon concocting my list of party requests and invitees. I hoped they were believable as I slid the inventory across the table to him at dinner time. He looked over them slowly, nodded his head approvingly, and then returned to his meal.

“When do you wish to have this party?”

The question caught me off guard as I cut into the meat on my plate, trying to figure out a way to hide it away and make it look like I was still eating.

“Oh, um,” I looked up at him, trying to make a quick decision of how much time I needed to prepare and what would be a believable time frame. “Perhaps in two days? Our wedding is at the end of the week, so we want a reasonable gap of time between them, don’t we, my husband?”

He nodded approvingly, bringing a mouthful of mysterious meat to his mouth, and my stomach turned as I watched him. I tried not

to react visually as I looked back down at my plate, sweeping the piece I had cut off into my lap and into the waiting napkin.

“Two days then. I’ll make the arrangements tomorrow.”

“Perfect.” Although I had chosen the time frame, it felt now like I had a ticking clock hanging over my head. Two days to get into the red room undetected and make a potion I did not understand how to brew, while also switching out the supply he had hidden somewhere. The next two days would put my detective skills to the test. At least that wasn’t much of a change from all the other time I had spent in the Storybook Realm.

We didn’t speak again as we finished the rest of our meal in silence, Bluebeard enjoying his Coq au Femme, while I scattered pieces into my lap to flush later. After dinner, he enjoyed his wine per usual, and we both read in silence in the library until he declared it was bedtime.

Like every other night, it followed in this ritual as we dressed for bed and laid down beside each other. The fear tonight he might break the abstinence he had established hung heavy over me, and every night, he fell into a snoring sleep eventually, my fears unfounded once more.

When I was sure he was sleeping, I began my process of getting out of bed and carefully made my way to the door. In the hallway, I hastened my steps and hurried for the basement. As I reached the steps that would take me down into the dark subfloor, a noise alerted me, and I turned to find Lamont creeping up behind me.

I gasped in surprise, my mind racing to come up with an excuse when the phoenix appeared out of nowhere. He landed on Lamont’s head and twisted it so quickly I barely had time to register what he had done.

“You killed him!” I didn’t mean to shout, but my surprise outweighed my carefulness.

“Don’t worry. I fed him some of my blood earlier. He will wake in the morning and forget this ever happened.”

“And what if he doesn’t?!”

“Do you think if Bluebeard remembered dying at his party every time he would continue to host them?”

The bird had a point, but I couldn’t help but think how problematic it would be if Bluebeard were to get up and see the body. Then again, if Bluebeard got up, I would have an entirely different set of issues.

“Fine, but at least help me move the body.”

“I am not your servant,” the bird declared indignantly.

“No, you’re my co-conspirator, so you need to help.” If birds could sigh, the phoenix did before it rose in the air again as I grabbed the feet. It swung itself around and settled on Lamont’s shoulders before gripping him tightly to lift.

We moved awkwardly down the hall, toward the housekeeper’s small room behind the kitchen. It took more time than I liked to get him in bed, where the bird insisted he would wake in the morning and would not remember. But something in my gut told me this was wrong, I just didn’t know what.

Once he was tucked away, we made our way back to the hallway. Paranoia tickled the back of my neck as I glanced over my shoulder to look up the stairs. Bluebeard was a deep sleeper, I knew this from experience. But I couldn’t help but worry more now that I knew I was dealing with a serial killer.

“Come along, Keeper,” the bird hung in the air outside of the entrance to the basement. I hurried over, slipping past my feathered companion and descending into the darkness.

“Did you get the key to the red room?” The bird had one job. I just hoped he hadn’t messed this all up for us already.

“Well, you could have done it, but as I am your co-conspirator, I covered your back.” The bird was sarcastic in tone as he flew beside me, and I glanced over to see him offering me Lamont’s set of keys in his claws. Right, I could have done that. But I was too busy worrying about getting a creepy old guy into his bed.

“Thanks,” I muttered as I grabbed the keys from him, and we made our way down the hallway, following the trail of light that illuminated our steps. “Any words of wisdom as to what I might find when we open this door?” I asked, glancing over at the phoenix one more time.

“Nothing nice.” He declared as I nodded my head. I knew that. My imagination had been running rampant since dinner time. I probably imagined every scenario we were about to encounter, and none of them were nice, as the phoenix suggested.

“Alright, well, no turning back now,” I said as I fumbled with Lamont’s keys and tried to find the one that would fit the lock. I finally slid the large iron key into the hole, and the lock clicked as I turned it. Tucking the key into my pocket, I nudged the door open. It swung slightly and then got stuck, forcing me to press it open. The bottom dragged across the floor, making a sticky, wet noise as it did.

Unlike the hallway, the red room didn’t have any magical lights turning themselves on. It left me squinting in the already dim lighting trying to make out what I might be looking at.

It was futile, though, even after my eyes adjusted, I could hardly see inside. The phoenix landed on one sconce, sitting there watching me next to a candle. I wandered over, lifting it from its placement and thanked the bird with a nod before turning back to the room.

The candlelight wasn’t much, but it was enough. It was enough to see into the room and illuminate the bodies of the other dead girls hanging on the wall. He drained of their blood, which was the source of the sticky wetness on the floor. Pools of blood coated the ground and wall, dripping from the edges of a worktable in the middle of the room.

Sickness rose up the back of my throat as I closed my eyes, pushing the images out of my mind. It was horrific, how could this be a part of fairy tales which were meant to be happy and loving? There was nothing about this that matched those ideals.

Then again, I remembered a series of fairy tales from a few centuries ago when the stories were a little more gruesome. They included missing toes, dead mermaids, and lots of death. Perhaps this was just one story that never got updated in time.

“Now I know why you call it the red room.” I looked back over my shoulder at the phoenix before turning to the room once more. If the potion would be anywhere, it had to be here. I paused before

entering, bending down to take my slippers off. As I did, the keys slipped out of my hand and landed in the pool of blood.

“Shoot.” I picked them up, wiping them off on my house robe, but the blood wouldn’t come off. “What the heck?”

“That’s how he catches them. The blood can’t be wiped off.” I looked over at the bird in horror.

“How am I supposed to go in there and find the potion if I will get blood all over me? He’ll know where I’ve been, then he’ll catch me.”

“That’s the point, he’s supposed to catch you. He catches all the others, and they still win.”

“I don’t know.” I looked back at the room nervously. “I’ve got enough stacked against me without adding that into the mix.”

“No one said this would be easy. You just asked what happened all the other times. This happened all the other times, Keeper.”

I sighed and stood up, tucking the keys back into my pocket before dropping my slippers in a safe zone.

It felt like entering that room and being caught doing so would turn this into a race against the clock. My two-day timeline would suddenly be much shorter because I knew he wouldn’t throw the party knowing that I knew his dirty little secret.

But if I didn’t go in there, and I didn’t change the potion. I would be the dead one. Not him. I really didn’t have any other choice. Once I’d worked up the courage, I tiptoed into the room and approached the worktable.

It was laid out like it belonged to a madman. Potion vials sat in the middle, a mortar and pestle filled with some kind of dark power, and there were so many decanters of blood.

Amongst all this was a pile of papers and books, so I began to dig through looking for the one that would give me the recipe for the potion he used.

“Let me know if he’s coming,” I shouted back to the bird as I flipped through the papers. They seemed to be records of all the girls as if by keeping them here locked behind a door, he was holding the record of their deaths from their families.

I didn’t know what I would do with them. Still, I felt like I needed to document these girls whose lives were taken by this monstrous man. So I tucked away a couple of the papers in my house robe and continued looking. After a while, I found a list of ingredients, one of them being that of phoenix blood.

“I think I found it.” I shouted over my shoulder as I read over the ingredients and then looked over what he had on the table. Gathering what I needed, I began to mix the potion.

“Three teaspoons of youthful blood…” I grimaced as I counted the measurements and poured them into the vial. “One scoop of dried valerian root…” Focused on my task, time passed quicker than I realized, and the phoenix let out a squawk.

“It’s almost morning time.” I looked down at the concoction as I put a stopper in it, shaking it up and then surveying it again. Based on the other vials he had sitting here, they all seemed to be the same in appearance. I doubt he would notice the difference. Setting the new potion down, I took the old vials and began pouring them out on the floor. Then, carefully, I refilled them all with the new one.

“Alright, I think I’ve done it.” I said, nervously glancing at the potion one more time. I had no way of testing it, I just had to be sure that it would work.

I rearranged everything to how it looked before I arrived and then left the room, locking it up as I turned back to the bird.

“C’mon, we need to get back to our cages.” He stretched himself out and lifted into the air, flying past my head and toward the stairs. I grabbed my slippers, pulling them on to hide my bloodied feet before following him quickly.

C H A P T E R F O U R

Iwas shaking at breakfast. Lamont still hadn’t appeared, and Bluebeard hadn’t noticed my blood-covered feet. My nerves were on edge, just waiting for the other shoe to drop when I should’ve been grateful for small graces.

“Invitations went out this morning for the party.” I looked up in surprise. My heart sped up. This was good. He wouldn’t have sent them if he knew what happened last night. I smiled, trying to remain calm.

“That’s good,” I said as I cut into my eggs and forked another mouthful in. I needed to remain calm. If I got too worked up over all of this, he might catch on that I was up to something.

“Are you excited?”

“For?” I said, looking up at him again, and he arched an eyebrow.

“The party?”

“Oh, right, yes. Very.” I nodded my head and smiled, “I think I’m going to spend today getting everything ready.”

“Yes, I have the caterers coming in to prepare. And I believe the decorators should come as well. You can handle all that, can’t you?” I nodded my head when a loud knock echoed through the usually quiet house.

“Well, that’s timely.” Bluebeard lifted his napkin and wiped his mouth, waiting for Lamont to get the door. But Lamont wasn’t going

to. Because either he was dead, or he hadn’t woken up yet. Either way, it was bad, and Bluebeard would find out soon what happened.

Whoever was at the door knocked again, and this time, Bluebeard frowned, “Where is Lamont? Why hasn’t he answered the door yet?” Perturbed, he rose from his chair and made his way to the front entrance. My already racing heart quickened the rate at which it was trying to escape my chest as I rose too, following a safe distance behind my captor to see who was at the door.

The door swung open magically, and as I came around the corner, I stopped in surprise when I saw who it was.

“Cinderella?”

“Yes?” Bluebeard and I spoke at the same time. He turned to look at me over his shoulder, frowned slightly, and then looked back at the young girl in the doorway.

“I believe you hired me to help with a party? You know my stepmother, Madonna Tremaine?”

“Oh, yes. Come in.” He stepped back and let Cinderella in, who looked at me with a frown. Of course, we didn’t actually know each other. But Erik had shown me her photo once. And we were stopped in the hallway together by her stepsisters. I hoped she recognized me too.

“The kitchen is this way. Serina, my love, I’m sorry, but we must cut our morning short. Duty calls.”

“Of course,” I nodded, curtseying slightly before watching out of the corner of my eye as he guided Cinderella toward the kitchen where he would find the body of Lamont, either breathing or dead.

I hurried toward the aviary, the phoenix would know what happened next, and I needed to prepare.

“He’s about to find out.” I burst through the doors and rushed into the room, looking around, trying to spot the enormous bird. I had gone a week without realizing he was here, so if he didn’t want me to find him, he knew how to hide.

“Phoenix?” I wandered further into the room, craning my neck back as far as it could go as I tried to find him. “Where are you? He’s about to find out, and I need to know what happens next. I can’t die. I have so much left to do.”

“Calm down,” the voice came from nowhere, and then suddenly, the bird swooped down, landing on the branch nearest me, and I pivoted. “If you really are The Keeper of Stories, then you’ll be able to stop your own death. You won’t become the rule, you’ll be the exception.”

“Are you sure you gave Lamont some of your blood? He wasn’t there this morning.”

“Did I say I gave him some of my blood?” The bird blinked, staring at me, and I could have sworn that he smiled cruelly. I felt cold in this humid room as I stared back at this creature, slowly realizing he had played me.

“You killed him? You killed him, and you lied to me?” I clarified. The bird shrugged and cleaned its talon on its beak.

“You promised we were getting out of here. If you’re taking down Bluebeard, it’s only fair I get my own taste of revenge.”

“This story isn’t about revenge. Your story isn’t about revenge. It’s about survival, and unnecessary deaths have nothing to do with revenge.”

If birds could roll their eyes, he did, and frankly, birds probably didn’t, but this one did. He continued to clean his talon before turning back to me in boredom. “You’re wasting time. Do you want to know the next part of the story?”

He was right, and as much as I wanted to lecture him on the expectations of the stories I was writing, I didn’t have time. I could only hope that my promise to free him would not be overshadowed by the fact I would let loose a bird that had a taste for blood.

“Yes, I need to know what happens next.”

“He finds out and tries to kill her.”

“And?”

“She convinces him to give her a quarter of an hour to prepare herself. Then she finds her sister, who was visiting. She sends her sister to the tower to look for their brothers, who should arrive soon. She continues to waste time trying to buy the brothers time to get there. Eventually, he tires of her wastefulness and tries to cut her

down with a sword. He injures her, but her brothers intervene first and kill him before he can really kill her.”

“Great,” I muttered, turning away from the bird and slumping down onto my bench. I caught my head in my hands and sat like that, trying to come up with an alternative that didn’t end with me skewered. Cinderella was here. She could play the part of the sister, but I had no one coming. No brothers. So, what did I do then? Fight Bluebeard back? I had killed a giant. Surely I could take down a man.

I didn’t have much time to come up with another solution when a bellow echoed through the house, and I turned to look at the phoenix who squawked before lifting into the sky and flying off.

“Thanks for all your help,” I shouted at him just as the doors to the aviary opened. Bluebeard stormed in like he was going to war, his neck flew from side to side as he looked for me and I just straightened up on the bench to wait. I could buy myself fifteen minutes. I needed to make those the most effective fifteen minutes of my life.

“You.” He pointed at me. “I told you not to go into that room. And now my housekeeper is dead, you have betrayed me. Well, if you want to go into that room, I will ensure you stay in it for the rest of time.” He reached me, swooping down to grab me by the elbow as he forced me to my feet, frog-marching me toward the doors.

“I’m sorry. I just needed to know what was inside.” I pleaded, trying to ease the firm grip he had on me. “I am sorry, please forgive me.” I played the role, pleading, and apologetic. I hoped that by abiding as much as I could to the rules of the story, it might tip the odds in my favor when I needed them the most.

“Well, now you know, and you will become a permanent fixture with the other nosy wives before you.”

“I know, I’m sorry. Please forgive me.”

“I cannot, my trust has been destroyed.”

“Then please, give me some time to put my things in order. Allow me to write a note to my family and ask their forgiveness for my carelessness.”

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

country and its language. The manufacturer or the merchant must take the pains to accommodate a direct import trade to the exigencies of the local market. As an example, smaller bales and shorter lengths are requisite in the piece goods. The establishment of sample warehouses at the treaty ports, and in the more important trade-centres of the interior, where bales of shirting, cotton and woollen goods, cases of farming implements, &c., could be opened and sold for cash, would appeal to the natives. This departure would avoid the increase in the prime cost of the articles necessitated by the existing system of transhipment. At present, goods come from Shanghai to Chi-fu and thence to Chemulpo. They pass then from the importer to the Chinese merchants, and from them to the Korean wholesale buyers; these resell them in greatly diminished quantities to the pedlars and agents, who retail the goods. It would also be advisable to create consular agencies in Fusan and Won-san. Official representation at present is confined to an underpaid and understaffed Legation in Seoul, and a vice-consulate in Chemulpo. Additional employés should be interchangeable, undertaking either the vice-consular duties of the ports or the secretarial services of the Legation.

The bulk of the imports and exports, which pass through the Customs, comes from China and Japan. The means of transport are controlled by Japanese; the export trade of the country is entirely in their hands. This fact alone should appeal to British shipping interests and to ship-owners. Unfortunately, many years of prosperity have brought about great changes in the spirit of our nation, and we no longer show the enterprise and initiative which formerly distinguished us. This depreciation in the forces of the nation has promoted a corresponding depression in our trade. We are no longer the pioneers of commerce; nor have we the capacity and courage of our forefathers who fostered those interests of which we are now so neglectful in every quarter of the globe. At the dawn of the twentieth century, it is amazing to find a country, with a total foreign import and export trade exceeding two millions and a half sterling for the year 1901 and two millions and three quarters sterling for the year 1902, whose shores were visited by over ten thousand steam and sailing trading-vessels in the same period, registering an aggregate tonnage

of more than two million tons, almost untouched by British merchantmen. Deplorable as this may be, statistics which Mr. McLeavy Brown has drawn up show that one steamship, chartered by Chinese and floating the British flag, entered Korean waters in 1900; that four steamers came in each of the years 1901-2, a return which reveals a steady decline upon the previous years. Since Korea was opened to trade in 1880, British shipping has visited the country in the proportion of 1377 tons to every two years. Despite appeals from our Consuls in Korea to British steamship companies improvement has been impossible; since no response was evoked by their efforts, and no service has been established. The consequence of this is that a valuable opportunity has been allowed to escape, the Japanese profiting by our indifference.

The trade of Korea is increasing gradually. A steamer, which could make periodical calls between Shanghai and Won-san, Yokohama and Vladivostock, taking cargo and passengers to the open ports of Korea, and touching at Japan upon the journey back, would return good money upon the venture. British and Chinese merchants would prefer to ship in a British vessel. The old-fashioned traditions of the British mercantile service, as to punctuality and despatch, are not carried out by the steamers of the Nippon Yusen Kaisha and the Osaka Shosen Kaisha, which call at the ports in Korea. It is almost impossible to know when the steamers of these companies will arrive or when they will leave. Little attempt is made to observe their schedule. The condition of the vessels of the latter company accredited to the Korean run is filthy Moreover, this company is careless of cargo, and quite indifferent to the comforts of its passengers. The Nippon Yusen Kaisha certainly supplies meals in foreign style, but the Osaka Shosen Kaisha provides nothing. Plying between Japan, China and Korea, this company declines to make any arrangements for foreigners in the matter of food or accommodation. One experience is enough. Unfortunately, foreigners are compelled to travel in them, as the steamers of one or other of the two companies are usually the sole means of communication between those countries and Korea. There is cargo and passenger traffic for any company that will organise a regular steam-service. The profits might be small at first, since the Japanese

prefer to endure their own steamers and to ship under their own flag; but there are signs that the flourishing condition of the trade of the country would bring ultimate success.

The establishment of a steamer-service, if only of one or two steamers, is not the sole hazard by which Japanese competition might be faced. The climate of Korea is peculiarly suited to fruitculture. If this work were taken in hand, the fruit might be tinned or exported fresh to China, where it would find a ready sale. The fertility of the soil near Won-san and the abundance of fish in the sea off that part of the coast, would make that port a suitable export centre for the creation of a fish and fruit-canning industry under foreign management. Fish and fruit industries of this description in Japan are profitable and very bad. Nevertheless, their output is widely distributed over the Far East. The initiation of these industrial ventures would require some time, for many difficulties oppress foreigners, who are anxious to put capital into Korea. In the end, a modest venture would reap sufficient success to justify the speculation, while the returns would probably permit an immediate expansion of the enterprise. There is no doubt about the fish; there is no doubt about the fruit; but whatever investment of an industrial character is made in Korea, close and high-class technical supervision is the necessary accompaniment.

The British merchant in the Far East is the first to condemn his own Minister and to abuse his own Consul, and he is the very last to help himself. It may be, however, that the follies of the Imperial Government, the unreasoning prejudices and foolish blundering of the Foreign Office, have created this apathy. The drifting and vacuous policy of Lord Salisbury made it impossible to avert the decay of our prestige and trade which has set in throughout the Far East. Official returns establish only too completely the unhappy predicament in which trade and merchants alike are placed. There is a general decrease in the volume of the one, and there has been no sympathetic activity among those engaged in commercial interests elsewhere to set against it. The deficiency is almost without solution, so long as bounty-fed manufactures, carried in subsidised bottoms, are set against the products of an unassisted trade. Competition is

increasing, and foreign manufacturers are themselves now meeting the requirements of the markets of China. There is little prospect in the future of the restoration of our former commercial superiority. Much might be attempted, although it seems almost as if the British merchant were so bent upon his own damnation, that little could be done.

The decline of British trade cannot be attributed in any way to the late disturbances in North China, to the decline in the purchasing power of the dollar, or to the temporary rise in the market prices. Japan has become our most formidable competitor. The decrease in our trade is due entirely to the commercial development and rise of Japan, who, together with America, has successfully taken from us markets in which, prior to their appearance, British goods were supreme. The gravity of the situation in which British trade is placed cannot be lightly regarded. We still lay claim to the carrying trade of the Far East; but the figures, which support our pre-eminence in this direction are totally unreliable. If the true conditions were made manifest, it would be seen that so far from leading the shipping of the world in the Far East, Great Britain could claim but a small proportion of the freights carried. Although we may own the ships, neither our markets nor our manufactures are associated with their cargoes. It would be well if the public could grasp this feature of the China trade. Members of Parliament, ignorant of the deductions which are necessary before claiming the carrying trade of the Far East—much less of the Yang-tse and of the China coast—as an asset in our commercial prosperity, and a sign of vigour of the first magnitude, do not recognise how unsubstantial is the travesty of affluence which they so constantly applaud.

BRICK LAYING EXTRAORDINARY

During 1901, owing to the Boxer disturbance, large numbers of ships owned by natives were transferred to the British flag. The ostensible decrease in the tonnage of British vessels, which entered and cleared affected ports, was therefore less than that of other nationalities. Similarly, there was a small increase in the duties paid under the British flag during the same period, owing to the valuable character of these cargoes. Under ordinary circumstances, the comparatively small decrease in the British tonnage and the increase of more than fifty thousand taels in the payments made to the Imperial Customs at such a moment of unrest, would suggest the stability of our trading interest, and afford no mean standard by which to judge the capacity of the markets. Unfortunately, the two most important counts in the returns, tonnage and duties, are no criterion. It is necessary to inspect closely the individual values of the different articles comprising the total trade. In this way the general depreciation of our manufactures is at once apparent.

A comparison of the American, Japanese, and German returns shows which are the commercial activities that are threatening our existence as a factor in the markets of the Far East. If, in the returns, we were shown the relations between the duties paid under each

flag, and the tonnage of any particular country, besides the source and destination of its cargo, the true condition of British trade would be revealed at a glance. As it is, until a table is added to the Maritime Report, which will supply this valuable and interesting demonstration, the system of a separate examination is alone to be relied upon. By this method we find that between the years 1891 and 1901 there was a consistent falling-off in British exports to the Far East in almost every commodity in which the competition of America, Japan, and Germany was possible. Since 1895, when Japan began to assert herself in the markets of China, those articles which, pre-eminently among the commercial Powers, she can herself supply, have carried everything before them. Ten years ago the British trade in cloths, drills, shirtings, cottons, yarns, and matches had attained magnificent dimensions. In certain particulars, only, our trade was rivalled by the United States of America, whose propinquity gave to them some little advantage in the markets of the Far East. Now, however, the trade has passed altogether into the hands of the Japanese, or is so equally divided between Japan and America, Japan and Germany, that our pristine supremacy has disappeared.

CHAPTER XIII

British, American, Japanese, French, German, and Belgian interests Railways and mining fictions Tabled counterfeited Imports

With the exception of Great Britain, the example of the Japanese in Korea has stirred the Western Powers to corresponding activity Every strange face in Seoul creates a crop of rumours. Until the new-comer proves himself nothing more dangerous than a correspondent, there is quite a flutter in the Ministerial dove-cots. Speculation is rife as to his chance of securing the particular concession after which, of course, it is well known he has come from Europe, Asia, Africa, or America. The first place among the holders of concessions is very evenly divided between Japan and America. If the interests of Japan be placed apart, those of America are certainly the most prominent. Germany and Russia are busily creating opportunities for the development of their relations with the industries of the country; Italy and Belgium have secured a footing; Great Britain is alone in the indifference with which she regards the markets of Korea.

In this chapter I propose to state briefly the exact position occupied in Korea by the manufacturing and industrial interests of foreign countries; adding a specific table, which, I hope, may attract the attention of British manufacturers to the means by which the Japanese houses contrive to meet the demands of the Korean market. The competition of the Japanese has an advantage in the propinquity of their own manufacturing centres; a co-operative movement throughout the Japanese settlements against foreign goods is another factor in their supremacy.

It may, perhaps, afford British manufacturers some small consolation to know that there are still many articles which defy the imitative faculties of the Japanese. These are, mainly, the products of the Manchester market, which have proved themselves superior

to anything which can be placed in competition against them. It has been found, for instance, impossible to imitate Manchester dyed goods, nor can Japanese competition affect the popularity of this particular line. Chinese grass-cloths have, however, cut out Victoria lawns fairly on their merits. The Chinese manufacturer, unhampered by any rise in the cost of production and transportation, produces a superior fabric, of more enduring quality, at a lower price. Moreover, in spite of the assumed superiority of American over English locomotives, on the Japanese railways in Korea the rolling stock produced by British manufacturers has maintained its position. It is pleasing to learn that some proportion of the equipment of the old line from Chemulpo to Seoul, and of the new extension to Fusan, have been procured from England. Mr. Bennett, the manager of Messrs. Holme Ringer and Company, the one British house in Korea, with whom the order from the Japanese company was placed, informed me that the steel rails and fish-plates imported would be from Cammel and Company, the wheels and axles from Vickers, and that orders for a number of corrugated iron goods sheds had been placed in Wolverhampton. The locomotives were coming from Sheffield. The Japanese company expressly stipulated that the materials should be of British make; it was only through the extreme dilatoriness of certain British firms in forwarding catalogues and estimates, that an order, covering a large consignment of iron wire, nails, and galvanised steel telegraph wire, was placed in America. This dilatoriness operates with the most fatal effect upon the success of British industries. The Emperor of Korea instructed Mr. Bennett to order forty complete telephones, switch-boards, keyboards, and instruments, all intact. Ericson’s, of Stockholm, despatched triplicate cable quotations, forwarding by express shipment triplicate catalogues and photographs, as well as cases containing models of their different styles, with samples of wet and dry cables. One of the two British firms, to whom the order had been submitted, made no reply The other, after an interval of two months, dictated a letter of inquiry as to the chemical qualities of the soil, and the character of the climatic influences to which the wires, switchboards, and instruments would be subjected!

A few years ago a demand arose for cheap needles and fishhooks. The attention of British manufacturers was drawn to the necessity of supplying a needle which could be bent to the shape of a fish-hook. A German manufacturer got wind of the confidential circular which Mr. Bennett had prepared, and forwarded a large assortment of needles and fish-hooks, the needles meeting the specified requirements. The result of this enterprise was that the German firm skimmed the cream of the market. The English needles were so stiff that they snapped at once; and it is perhaps unnecessary to add that, beyond the few packets opened for the preliminary examination, not one single order for these needles has been taken.

The position which Great Britain fills in Korea is destitute of any great commercial or political significance. Unintelligible inaction characterises British policy there—as elsewhere. Our sole concession is one of very doubtful value, relating to a gold mine at Eun-san. In the latter part of 1900 a company was formed in London, under the style of the British and Korean Corporation, to acquire the Pritchard Morgan Mining Concession from the original syndicate. In the spring of 1901 Mr. E. T. McCarthy took possession of the property on behalf of the new owners. Mr. McCarthy had had considerable experience as a mine manager. The most careful management was necessary to the success of this concern. The expenses of working were extraordinarily heavy, as, owing to the absence of fuel, coal had to be imported from Japan. A coal seam had been located upon the concession, but nothing was then known as to its suitability for steam purposes. It is impossible to consider the undertaking very seriously. All surface work was stopped during my residence in Korea, the operations for the past few months having been confined to underground development and prospecting. There was talk of the instalment of a mill. A vein of pyrrhotine, carrying copper for a width of 13 ft., was regarded with some interest, but in the absence of machinery nothing of much consequence could be done.

Another concern, Anglo-Chinese in its formation, is the Oriental Cigarette and Tobacco Company, Limited. The capital of this venture

is registered from Hong-Kong. Since May 1902, the company has been engaged at Chemulpo in the manufacture, from Richmond and Korean tobacco, of cigarettes of three kinds. At the present time it possesses machinery capable of a daily output of one million cigarettes. In the days of its infancy, the company was reduced to a somewhat precarious existence—the early weeks of its career producing no returns whatsoever. Now, however, a brighter period has dawned, and an ultimate prosperity is not uncertain. Cash transactions, in the sales of the cigarettes manufactured by the company, began in July 1902, realising by the end of February 1903, £1515 sterling; to this must be added credit sales of £896 sterling— making a grand total for the first few months of its existence of £2411 sterling. A large staff of native workers is permanently employed.

Aside from this company and the mining corporation, British industrial activity is confined almost exclusively to the agency which Mr. Bennett so ably controls in Chemulpo, of which a branch is now established in the capital, and the Station Hotel which Mr. Emberley conducts at Seoul. Mr. Jordan, the British Minister in Korea, did request in June 1903, a concession for a gold mine five miles square in Hwang-hai Province. Apart from this, the apathy of the British merchant cannot be regarded as singular when business houses in London direct catalogues, intended for delivery at Chemulpo, to the British Vice-Consul, Korea, Africa. Nor, by the way, is Korea a part of China. Mr. Emberley has established a comfortable and very prosperous hotel in the capital, while at Chemulpo Mr. Bennett has opened out whatever British trade exists in Korea. British interests are safe enough in his hands, and if merchants will act in cooperation with him, it might still be possible to create good business, in spite of the competition and imitation of the Japanese. In this respect British traders are not unreasonably expected to observe the custom, prevailing among all Chinese merchants, of giving Korean firms an extended credit. Foreign banks in the Far East charge seven or eight per cent., per annum, and the native banks ten to fourteen per cent., which represents a very considerable advance upon home rates. In the opinion of Mr Bennett, who is, without doubt, one of the most astute business men in the Far East, no little improvement would be shown in the Customs return of British

imports, if the manufacturers at home would ship goods to Korea on consignment to firms, whose standing and bank guarantees were above suspicion, charging thereon only home rates of interest. An American company, engaged extensively in business with Korea, never draws against shipments, by that means deriving considerable advantage over its competitors. I commend this suggestion to the attention of the British shipper, particularly as trade in Korea is largely dependent upon the rice crop. In the train of a bad harvest comes a reduction of prices. Importers, then, who have ordered stocks beforehand, find themselves placed in a quandary Their stocks are left upon their hands—it may be for a year, or even longer —and they are confronted with the necessity of meeting the excessive rates of interest current in the Far East. If the manufacturer could meet the merchant by allowing a rate of interest, similar to that prevailing at home, to be charged, the importer of British goods would be less disinclined to indent ahead. Under existing circumstances the merchant must take the risk of ordering in the spring for autumn delivery, and vice-versâ; on the other hand, China and Japan, being within a few days’ distance of Korea, the importer prefers to await the fulfilment of the rice crop, when, as occasion requires, he can cable to Shanghai, Osaka, or elsewhere for whatever may be desired.

Attached to the English Colony in Korea, which numbers one hundred and forty-one, there is the usual complement of clergy and nursing sisters, under the supervision of Bishop Corfe, the chief of the English Mission in Seoul. Miss Cooke, a distinguished lady doctor and a kind friend to the British Colony, is settled in Seoul. A number of Englishmen are employed in the Korean Customs; their services contributing so much to the splendid institution which Mr. McLeavy Brown has created, that one and all are above criticism. Mr. McLeavy Brown would be the first to acknowledge how much the willing assistance of his staff has contributed to his success.

The importance of the American trade in Korea is undeniable. It is composite in its character, carefully considered, protected by the influence of the Minister, supported by the energies of the American missionaries, and controlled by two firms, whose knowledge of the

wants of Korea is just forty-eight hours ahead of the realisation of that want by the Korean. This is, I take it, just as things should be. The signs of American activity, in the capital alone, are evident upon every side. The Seoul Electric Car Company, the Seoul Electric Light Company, and the Seoul (Fresh Spring) Water Company have been created by American enterprise, backed up by the “liveness” and ’cuteness of the two concessionaires, whom I have just mentioned, and pushed along by little diplomatic attentions upon the part of the American Minister. The Seoul-Chemulpo Railway Concession was also secured by an American, Mr Morse, the agent of the American Trading Company, and subsequently sold to the Japanese company in whom the rights of the concession are now vested. The charter of the National Bank of Korea has also been awarded to these Americans, and it is now in process of creation. The only mine in Korea which pays is owned by an American syndicate; and, by the way, Dr. Allen, the American Minister, possesses an intelligible comprehension of the Korean tongue.

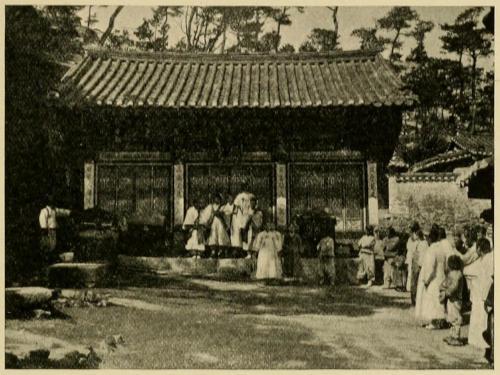

THE CONSULTING-ROOM OF MISS COOKE

There is a large American colony in Korea, totalling in all two hundred and forty. One hundred live in Seoul; sixty-live are employed upon the American Mine at Un-san; thirty-four live at Pyöng-yang. Five are in the service of the Korean Government; ten are associated with the railway; the famous two are engaged in business and the remainder comprise the staffs of the Legation and Consulate, and a medley of missionaries. American trade with Korea embraces kerosene, flour, mining machinery, railway and mining supplies, household goods and agricultural implements, clothing and provisions, drills, sheetings, cotton goods, and cotton yarn. The American mine at Un-san employs seventeen Japanese and one hundred and thirty-three Chinese, one hundred Europeans, of whom thirty-five are American, and four thousand natives, whose wages range from 8d. to 1s. 2d. daily. The private company that has acquired this concession works five separate mines with enormous success; four mills, two of forty stamps and two of twenty stamps, are of long standing. An additional mill of eighty stamps is of more recent construction. During 1901 gold to the amount of £150,000 was exported by the company, while in the year following this sum was very vastly exceeded. The area of the concession is eight hundred square miles.

The future alone can disclose whether Korea is to be absorbed by the Japanese. At present, the Japanese population in Korea exceeds twenty thousand, the actual estimate falling short of twentyfive thousand. The Japanese control the railway between Chemulpo and Seoul, as well as the important trunk line to Fusan, an undertaking now in course of construction and under the immediate supervision of the Japanese Government. The new company has since absorbed the parent line from Seoul to Chemulpo. The capital of this company is twenty-five million yen, £2,500,000, which is to be raised in annual instalments of five million yen, counting from the time when one-tenth of the first instalment of five million yen was found. As a matter of fact, the preliminary turning of the first sods took place at Fusan on September 21st, and at Yong-tong-po on August 20th, in the summer of 1901. From that moment, the Japanese Government made itself responsible for the payment of the debenture bonds, and guaranteed six per cent. upon the

company’s subscribed capital for a period of fifteen years.[1] Each share is of the value of £5, the money to be called up as required, each call being at the rate of ten shillings per share. The whole of the 400,000 shares, which was the original allotment, was at once taken up, Japanese and Koreans alone being eligible as shareholders. The estimated cost of the line is £9000 per mile. Work has been completed as far as Syu-won, a distance of twenty-six miles, over which section trains are already running. Construction is, of course, being rapidly pushed forward, and working parties are engaged at a number of places along the line of route.

The length of the Seoul-Fusan Railway will be 287 miles. It is confidently expected that the undertaking will be completed within six years. There will be some forty stations, including the terminal depôts, and it is, perhaps optimistically, estimated that the scheduled time for the journey from Fusan to Seoul will be twelve hours, which is an average of twenty-four miles an hour, including stops, the actual rate of speed being approximately some thirty miles an hour. The present working speed of the Seoul-Chemulpo railway requires a little less than two hours to make the journey between Seoul and Chemulpo, a distance of twenty-five miles, from which it will be seen that considerable improvement must take place if the distance between Seoul and Fusan is to be accomplished within twelve hours.

In the first few miles of the journey, the trunk line to Fusan will run over the metals of the Seoul-Chemulpo railway. The start will be from the station outside the south gate of the capital; the second stop will be Yong-san, and the third No-dol. At the next station, Yong-tong-po, the railway leaves the line of the Seoul-Chemulpo branch to run due south to Si-heung, where it bears slightly eastward until reaching Anyang and Syu-won, some twenty-six miles distant from Seoul. At this point the railway resumes its southerly direction and passes through Tai-hoang-kyo, O-san-tong, and Chin-eui, where it crosses the border of the Kyöng-keui Province into Chyung-chyöng Province, and reaches the town of Pyöng-tak. The line then runs near the coast, proceeding due south to Tun-po, where it will touch tide water, and, bearing due south, reaches On-yang, sixty-nine miles from Seoul. It then proceeds in a south-easterly direction to Chyön-eui,

and once again turning directly south crosses the famous Keum River and enters the important town of Kong-chyu. From Kong-chyu, which is ninety-six miles from Seoul, and by its fortunate possession of facilities for water transit, is destined to become an important distributing centre, the line follows its southward course towards Singyo, where an important branch line will be constructed towards the south-west to connect Kang-kyöng, the chief commercial centre of the province, with the main system. It is also probable that a further extension of the line from Sin-gyo towards the south-west will be projected, in order to make communication with Mokpo, the coast port through which passes the grain trade of Chyöl-la and Kyöngsyang Provinces.

The town of Sin-gyo marks one hundred and twenty-five miles from Seoul; beyond Sin-gyo, the south-westerly direction, which the line is now following, changes by an abrupt sweep to the east, where, after passing through Ryön-san, a western spur of the great mountain chain of the peninsula is crossed, and the town of Chinsan entered. Still running east to Keum-san, the valley of the southern branch of the Yang River is traversed in its upper waters, until, after following the river in a north-easterly direction for some little distance, the road takes advantage of a gap in the mountains, through which the Yang River breaks, to cross the stream and turn due east to touch Yang-san, coming to a pause one hundred and forty-one miles from Seoul in Yöng-dong. From Yöng-dong the railway moves forward north-east to Whan-gan, one hundred and fifty-three miles from Seoul, the place lying close within the mountain range but a few miles distant from the Chyu-pung Pass—to cross which will call for more than ordinary engineering skill. Leaving the pass and running slightly south of east, the railway proceeds towards the Nak-tong River, through Keum-san, crossing the stream at Waikoan, a few miles north-east of Tai-ku, a town of historical importance some two hundred miles from Seoul. The railway then follows the valley of the Nak-tong, and passes to the east of the river, through Hyön-pung, Chyang-pyöng, Ryöng-san, Syök-kyo-chyön, Ryang-san, Mun-chyön, Tong-lai, where the Nak-tong River is again met. The direction from Tai-ku is south-east all the way to Fusan, whence the line runs beside the river. At Kwi-po it strikes across to

the native town of Old Fusan, thence running round the Bay to its terminus in the port.

This railway, which provides for extensive reclamation works in the harbour of Fusan, has become already an economic factor of very great importance. More particularly is this manifest when it is remembered that the country through which the line passes is known as the granary of Korea. Developments of a substantial character must follow the completion of this undertaking, the position of Japan in Korea receiving more emphatic confirmation from this work than from anything by which her previous domination of the country has been demonstrated. It will promote the speedy development of the rich agricultural and mining resources of Southern Korea, and as these new areas become accessible by means of the railway, it is difficult to see how the influx of Japanese immigrants and settlers to the southern half of the kingdom can be avoided. Indeed, a very serious situation for the Korean Government has already arisen, since by far the greatest number of the men, engaged upon the construction of the Seoul-Fusan Railway, have signified their intention of becoming permanent settlers in the country. In the case of these new settlers, the company has granted from the land, which it controls on either side of the line, a small plot to each family for the purposes of settlement. While the man works upon the line, his family erect a house and open up the ground. Whether or no the action of the company can be justified to the extent which has already taken place, the policy has resulted in the establishment of a continuous series of Japanese settlements extending through the heart of Southern Korea from Seoul to Fusan.

From time to time the Japanese Government itself has attempted to stem the torrent of Japanese migration to Korea. But the success of the colonies already settled there has made it a delicate and a difficult task—one which, in the future, the Japanese Government may be expected to leave alone. The railway once open, the still greater stimulus which will be imparted to agriculture in the southern half of the kingdom, will appeal to many thousands of other would-be settlers. Whatever objection the Korean Government may offer to this invasion, it is quite certain that with the very heart of the

agricultural districts laid bare, Korea must be prepared to see a rapid increase in her already large Japanese population. In a great part the increase is already an accomplished fact. The influence of Japan is already supreme in Korea. It is paramount in the Palace; and it is upheld by settlements in every part of the country. In the capital itself there is a flourishing colony of four thousand adults. She has established her own police force; created her own post-office, telephone, cable and wireless telegraph system. She has opened mines—her principal mine is at Chik-san—and has introduced many social and political reforms, besides being the greatest economic factor in the trade of the kingdom.