KIMBRA SWAIN

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Kimbra Swain

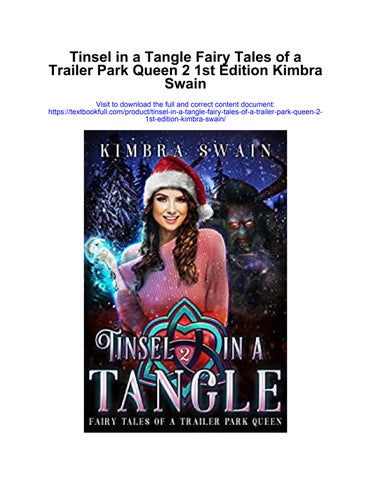

Tinsel in a Tangle: Fairy Tales of a Trailer Park Queen, Book 2 ©2017, Kimbra Swain / Crimson Sun Press, LLC kimbraswain@gmail.com

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This book contains material protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from the author / publisher.

Cover art by Hampton Lamoureux @ TS95 Studios https://www.ts95studios.com

Formatting by Serendipity Formats: https://serendipityformats.wixsite.com/formats

Editing by Carol Tietsworth: https://www.facebook.com/Editing-by-Carol-Tietsworth328303247526664/

CONTENTS

1. December 12th

2. December 13th

3. December 14th

4. December 15th

5. December 16th

6. December 17th

7. December 18th

8. December 19th

9. December 20th

10. December 21st

11. December 22nd

12. December 23rd

13. Christmas Eve

14. Christmas Day Acknowledgments About the Author

DECEMBER 12TH

CONTORTING MY HEAD SIDEWAYS, I HOPED TO INSTRUCT MY DEAR BARD ON the shortcomings of his current task. “Levi, it’s crooked.”

“No, it isn’t,” he complained.

“Yes, it is, honey,” Kady said, sitting beside me.

“It’s not fair that there are two of you now to gang up on me,” he whined.

“You have no holiday spirit,” I said giggling at him. “Dublin, the whole tree is crooked, not just the star.”

Christmas back in the Otherworld was celebrated as Yule around the winter solstice. The longest day of the year. It symbolized the darkness giving into the light. I never really liked the celebration, plus I’d spent my entire life in the human realm avoiding the darkness. Especially that darkness within myself. The celebration always reminded me that no matter what the orbit of the sun, the darkness inside of me continued to fester. However, the human celebrations of Christmas involved lots of lights, decorations, and family. The celebration also switched dates over the years as humans tinkered with the calendar. I never had much family until recently, but I loved decorating a Christmas tree, stringing lights and baking cookies. In fact, Christmas was why I learned to cook.

When I moved into my first trailer park, an older woman by the name of Sharolyn brought me into her family as one of her own. She loaned me her recipes teaching me all the shortcuts and secrets to

really good food. I’d spent ages in the human realm, and what little contact I had with humans was generally sexual. Until Miss Sharolyn. Christmas reminded me of her and the family I didn’t have.

But, I finally had a family. A misfit one of sorts, but they were mine. I watched Levi trying to set the tree straight and the cold recesses of my heart melted into the warmth of actually belonging somewhere. Home. Family. Christmas.

“I don’t know why we are putting a star on it, because it’s supposed to be an angel,” he continued to moan.

“The last thing an angel needs is a piece of evergreen up his butt,” I laughed. Kady laughed too, but Nestor Gwinn, the bar owner and my grandfather, huffed behind us. “What’s wrong, Nestor?”

“Grace, have you ever met an angel?” he asked.

“No, but I hear they act like they have something stuck up their butt!” I laughed.

“Honey, if you ever meet one, please run. Heaven’s sake, don’t speak to him. He’s liable to throw the gates of hell open and push you through,” Nestor warned. I turned to see if he was joking, but behind his smirk, I saw a twinge of fear. If he’d met an angel, I’d like to hear that story.

“I’ve met an angel. She’s sitting next to you,” Levi said ogling Kady. Kadence Rayburn was the preacher’s daughter. They met at church a couple of months ago. They hit it off so well, I could hardly stand to stay with them in the trailer. If the trailer was rocking… I would sleep on Nestor’s couch. He lived in a small apartment above the bar.

Kady was a healthy girl with curves in all the right places. Her brown doe eyes drew my bard’s attentions from the moment he met her. For now, she made him happy. The day she stopped, I would end her.

“Aw,” she cooed. She blew him a kiss, and he caught it. Young, stupid love.

I rolled my eyes. “Gag a maggot,” I teased.

“Where’s Dylan?” Kady asked.

“I am not Dylan’s keeper,” I replied.

“She knows exactly where he is at all times. He reports in regularly,” Levi responded.

“At this very moment, I do not know where he is, Levi Rearden. How dare you call me a liar?” I said. “Honey, the tree is straight now. Leave it alone.”

“Okay, cool. Now I can hang these lights,” he said, dipping into the box of decorations that Nestor gave us to put up around the bar. I'd already hung green and red tinsel around the edges. It was tangled up when I took it out of the box. About an hour later, I had it sorted.

“I’ll help,” Kady said, leaving me alone at the bar. The Hot Tin Roof Bar was the only watering hole in Shady Grove, Alabama. My grandfather ran it. Nestor Gwinn was a kelpie.

A kelpie, an equine water fairy that lures passersby in order to trap them into their aquatic abode, was kind of fitting for the barkeep. However, he had no plans on drowning his patrons. It’s hard to get repeat sales when the customer is deceased.

Levi Rearden was a changeling, the first bard born into the known world in over a hundred years. I was his patron, Grace Ann Bryant, Trailer Park Queen. Actually, my official title was Queen of the Exiles, but I lived in a double wide, proudly sported a large tattoo on my right arm, and liked my shorts very short. However, it was December, so I wore tight chocolate leggings with a burgundy tunic. Tall brown boots and a plaid scarf at my neck. Kady picked the outfit out. She said I looked cute.

Shady Grove’s population was riddled with exiled fairies. Since I became their Queen a few months ago, the town had grown exponentially. Many exiled fairies got the word that a Queen had emerged to protect them. When I agreed to this role, I didn’t realize the trouble I was getting myself into, but here I was.

I turned my back on the love birds. They made me sick with all their touchy-feely crap. Nestor shook his head at me. The bar was mostly empty. One patron sat at the end of the bar with beady eyes munching on the free peanuts. He had an empty bottle of cheap beer.

“May I have another cup?” I asked. Nestor made magical coffee. It not only warmed your body, but it soothed your soul. It seemed my soul needed a lot of soothing lately.

“Sure,” he said refilling my cup. “So, where isDylan?”

“He drove into Tuscaloosa to get some paperwork for this fool idea of becoming a private investigator,” I said.

“Grace, the guy is not a sheriff anymore. Why is it a fool idea?” Nestor asked.

“Because, what’s he gonna do? Stake out cow pastures for tippers?” I asked.

Nestor laughed. “I’m sure he will find plenty of cases with the influx of fairies we’ve had lately,” he replied. He was right. Things were getting hectic around here.

“I suppose,” I grumbled. Levi had passed his bah humbug to me.

“You really don’t want him to do it? What’s he supposed to do, Grace? Follow you around everywhere?” Nestor said.

“No, I’m still mad at him,” I replied.

“You’ve got to get over that,” he chided. I wasn’t really mad at Dylan Riggs who had managed to get himself shot trying to save me. He died actually, but unbeknownst to me, he was a phoenix rising from the ashes. He lied to me about a lot of things before and after he died. His death rocked me in a way I never imagined possible. We had a long friendship, a torrid one-night stand, and several months of bickering. Then he died, forcing me to realize how important was to me. I just wasn't ready, after hundreds of years to commit to someone.

As a fairy, my hormones and inclination for sexual connection erupt far more than the normal human. It made it hard for me to tell the difference between lust and love. However, when Dylan died, it ripped me to pieces. When he returned, I was madder than hell. We still spent time together, but we played a game where he would ask for a reprieve of my anger in small increments of time.

“I’m afraid that if he gets involved with police work that he might die again,” I admitted quietly to Nestor. Long before I realized Nestor was my grandfather, he was my bartender. He listened to my problems, supplied my alcohol, and gave sound advice. I hadn't

drunk very much since Dylan returned. Nestor’s supernatural coffee was enough to soothe my apprehensions.

“Fortunately for him he can rise from the dead,” Nestor pointed out.

“Yes, but is there a limit on that kind of thing? Is there a way to kill him where he won’t come back?” I shuddered at my own statement. Sitting my cup down, I wrung my hands trying to calm the shaking. The mere thought of it terrified me.

Nestor laid a warm hand over mine and stared at me. “Grace, we only get one life. Granted most of us have lived longer than we ever imagined, but you have to make the most of the time you have. Don’t let your fear of losing him keep you apart. Most of this town knows exactly how you feel about each other, even if you won’t admit it.

“Hmph,” I grunted and turned back to the young couple hanging lights. “Looks good, guys!”

The lights added a twinkle to the normally darkened bar. Nestor’s bar wasn’t exactly a dive, but it certainly wasn’t like the fancy ones I’d seen in photographs. I loved magazines, especially tabloids. I loved spending time at the bar. Finally, I was able to return after I spent so much time away from it after Dylan and I hooked up the first time.

As if on cue, the bar door swung open, and Mr. Sandy Hair came in from the cold. His brilliant blue eyes flashed when they met my eyes. When his smile stretched across his face, I was undone. He never looked at Levi or Kady when they greeted him. Striding forward to the bar next to me, he tapped on it lightly as Nestor poured him a warm cup of coffee. He dumped two spoons of sugar into it and took a sip.

“It’s cold enough to freeze the tits off a frog,” he exclaimed. Levi and Kady laughed.

“Frogs don’t have tits,” I said, not looking at him.

“I beg your pardon, my Queen,” he said, insisting on referring to me in that infernal way. “But I do remember a biology class long, long ago where we dissected a frog, and it most certainly had tits.”

“You were never in a biology class,” I proclaimed, finally looking up at him.

Leaning over to whisper in my ear, he said, “Five seconds.”

“You can’t do anything meaningful in five seconds,” I replied.

“Please,” he begged. I melted.

“Five seconds,” I said, starting to count silently in my head. He wrapped his arm around my waist, and I could feel the radiating warmth of his body.

“Beautiful Grace,” he muttered. Pressing his lips to my cheek, he pulled away the moment I reached five in my head.

Chills ran down my spine, and I gulped. Five seconds was plenty to make the fairy whore inside of me turn cartwheels.

“Meaningful?” he asked.

“I suppose,” I replied suppressing the desire to make out with him in front of everyone. He sat down on the stool next to me and watched Levi hanging lights around the room.

“The tree looks good,” he said.

“Yes, once Levi finally got it straight. But I agree that it does look mighty fine,” I declared. Levi grinned at my admission that he’d done a good job. Kady rubbed his shoulder drawing his attention away from Dylan and me.

“You get your paperwork done?” I asked.

“I just picked it up. I’ll work on completing it after the holidays,” he said.

The bar door swung open again, and the new sheriff, Troy Maynard walked in, bringing a wave of cold with him.

“Lord have mercy. Shut that door, Troy. You are letting the heat out,” I proclaimed.

“Grace! I’ve been looking for you,” he said exasperated. I looked down at my phone, but I hadn’t missed a call. He noticed and continued, “I didn’t call. I figured you’d be here. Oh, hey Dylan.”

“Troy,” Dylan acknowledged him. Dylan used to be the sheriff until his involvement with me got him suspended, and like the romantic moron that he was, he quit his job for me. I adored him for it, but of course, I refused to admit it. Either way, he knew. I hoped.

“I need you to come down to holding. We’ve got a guy down there whom we dragged out of Deacon Giles’ field. He’s demanding to see the Queen, and raising hell. Will you please come talk to him?” he begged.

“She can’t just show up for every misguided fairy,” Dylan protested. Laying my hand over his, I squeezed.

“What was he doing in the field?” I asked.

“Terrorizing the livestock,” Troy replied.

“You mean he was, um, doing it with them?” I asked. My mind wallowed in the gutter. Fairy.

“No! Not that. He was chasing the sheep, making the goats faint and tipping the cows,” he sighed.

“Sounds rather fun to me,” I giggled as Dylan poked me in the side. “Come on, let’s go talk to a fool.”

Leaving Levi and Kady to finish decorating, Dylan drove me down to the sheriff’s department. “I’m sorry if I interfered,” he said.

“You’re right, I’ve gotten myself into one hell of a mess, but I’m good at that, aren’t I?” I asked trying to prevent him from feeling guilty for caring about me.

“You most certainly are, but this queen thing has gotten out of hand. Every time you turn around some forlorn fairy is begging for your protection,” he said. “You can’t possibly protect them all.”

“Just accepting who I am provides a measure of protection. I’ve virtually claimed the exotic town of Shady Grove as my kingdom, and my palace is a double wide,” I smirked.

“You make light of it, but I know you got more than you bargained for when you accepted all of this. I’m sorry if I pushed you into it,” he said.

“I did get more than I anticipated, but Dylan, I don’t blame you, so stop being so dammed forlorn. It’s the holidays. Let’s celebrate and have fun,” I suggested.

He squeezed my hand as we pulled into the lot outside the sheriff’s department. “As you wish, my Queen.”

“Quit fucking calling me that,” I protested. He finally laughed.

“Vulgar mouth,” he said turning to me.

“One minute,” I offered as he stared at me.

“I didn’t ask for a minute,” he protested.

“I read your mind,” I smiled.

“You did not,” he replied.

“Fine. My bad,” I said grabbing the door handle.

“Um, no,” he said pulling me to him and covering my mouth with his. I lost count around twenty-two. But approximately a minute later, he rested his forehead on mine, “Do you know how hard it is to count while doing that?”

“Actually, it’s easy. You were two seconds short,” I replied.

“Damn you, Grace,” he grumbled, getting out of the car. I climbed out before he could open the door for me, watching him scowl. He took my hand as we entered his former place of employment.

We walked past receiving through a set of double swinging doors to the entrance to the holding cells. It wasn’t so long ago that I inhabited one of the cells after being accused of murder. Thankfully, those charges were dropped.

Bellows assaulted our ears as we entered the cell room. “I’m not talking to nobody, but the queen. You bring her here to me. I demand it. It’s my right,” he screamed, filling the room with his screeching.

Stopping in my tracks, Dylan almost ran over me, but he froze as we both laid eyes on the bellower. He stood around five and half foot tall with gangly arms and bulging eyes. His hands hung too long past his waist. His long boney fingers twitched as he protested. However, beyond this strange appearance, he teetered on a long, wooden peg leg.

“You’ve got to be fucking kidding me,” I mumbled. Dylan suppressed a laugh behind me as I elbowed him. “Enough of that racket. I’m here. What the hell do you want?”

He leveled his beady eyes on me and grumped, “You ain’t no queen. You look like trailer trash.”

Dylan snorted behind me, and I whipped around on him. He held his hands up in surrender as my eyes flashed turquoise. Shaking my head to release the anger, I looked at him again, conveying my contrition the best I could without speaking. “It’s okay. Do your thing,” he urged. He knew tapping into the fairy queen made me jumpy.

Turning back to the old man who continued to demand to see the queen, I pulled power stored in my tattoo, and my glamour dropped revealing the Ice Queen within me. “Silence!” I demanded. I’ll admit that since I’d embraced my new calling, I felt like I could control Gloriana, my true fairy name. I was the daughter of the King of the Unseelie Fairies in the Otherworld, Oberon. My mother, one of his many concubines, was the first to ever provide him with a female heir. I’d subsequently gotten into enough trouble to get banished from his realm, and we had only recently reconnected. He seemed to have finally accepted my decision to live amongst humans, but only once I decided to lead the other exiles here.

My sparkling silver gown stretched to the floor shimmering under the cool fluorescent glow of the holding cell. The room turned colder as frost formed on the bars between the gangly fairy and myself.

“My Queen,” he said, trying to bow, but his peg leg slid on the concrete. He found himself before me on his knees.

Suppressing an immature laugh, I asked, “Why have you called me here?”

“Forgive me, but these human lawmen do not understand our ways. I hoped you would intercede for me in allowing me to leave this jail. I meant no harm to the creatures. I love animals. See,” he said screwing his peg leg off to show me intricate carvings of various animals all around it. “I’m working on this new one here. It’s a wild hog, a razorback.” He beamed proudly at his craftsmanship, but once his eyes turned to my cold, blank stare, he gulped.

I stood transfixed by the utter ridiculousness of the situation. I put my hand up politely refusing to hold his wooden leg. “Why were you torturing Mr. Giles’ livestock?” I asked, standing over him.

“It’s just what I do. How I have fun,” he said.

“You will not do this in my city. Do you understand? I cannot intercede if you are a menace!” I replied with force.

He cowered before me. “Yes, my Queen, please forgive me.”

“The fairies in this town live by the rule of law. I see to it that they do. In turn, I protect them. However, if they cross the line, they pray that Sheriff Maynard catches them before I do,” I informed him.

“Yes, ma’am, I understand,” he said, leaning forward and kissing my shoe.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Lamar,” he replied.

“Well, Lamar, you will spend the night here. If you simmer down, Sheriff Maynard will let you leave tomorrow. However, you must promise me that you will not torture any more livestock.” I said.

“I promise,” he muttered, sounding defeated.

“Cow tipping?” I questioned.

A large grin passed over his face. “Yep, with my peg leg. I just tap them with it, and kaboom, they flop over,” he giggled. His laugh sounded like a donkey, and he slapped his knee for good measure. “Only that last time, the cow fell the wrong way, and I got caught.”

“The cow fell onyou?” I asked.

“Yep, he pinned me good. I was hollering for help, but the good farmer left me there while the lawmen were called,” he grumped.

“Serves you right,” I said with a smile. “Cow tipping is a heinous crime.”

“Thank you, my Queen,” he replied.

I turned swiftly before I died laughing in front of him. Dylan continued to smirk behind me. My glamour popped back into place as we passed through the doors. Hurrying to the front door, I let loose as my laugh echoed through the parking lot. Dylan joined me as tears of humor formed in the corners of his eyes. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” he said.

“With my peg leg,” I replied poking at him with my finger. We continued to laugh when Troy stepped out of the building.

“Good grief,” he exclaimed. “Thank you, Grace. He would not shut up. It’s been like that for hours. The guys were about to lose their minds.”

I waved my hand at him, “No problem, Wolf.” Troy Maynard was a werewolf. One of the few who weren’t fairies in this town.

“Y’all have a good night,” he said, turning back to the warmth of the station.

“Will you take me home, Dylan?” I asked, gathering my senses.

“It will be my pleasure,” he replied.

“You aren’t staying,” I added.

“I know. You are still mad at me,” he said.

“But I’ll give you an hour,” I smiled.

“I can do a lot of things in an hour,” his face brightened. “Come on, let’s go!” He eagerly pulled me to his car, practically shoving me in the passenger seat. My laughter returned as he tore out of the parking lot, heading for my double wide.

DECEMBER 13TH

WAKING UP TO THE SMELL OF COFFEE BREWING HAS TO BE THE MOST GLORIOUS way to wake up. However, alone in a cold bed isn’t so fun. I jumped up, starting the warm water in the shower when I heard Dylan’s voice in the living room.

I threw open the door and stared at him. “Well, good morning, Sunshine,” he quipped.

“Your hour was up a long time ago!” I protested.

“Yes, it was. I went home, slept and returned this morning. Levi invited me in for coffee,” he explained, kicking Levi in the shin.

“Ow, um, yeah, coffee,” Levi said, flicking channels on the television. He took a sip of his coffee, eyeballing me over the rim of the cup. Both of them waited with bated breath for my reaction.

I huffed, turned on my heels, slamming the bedroom door. Listening intently, I heard them both suppressing laughs. The bastards.

My shower didn’t last as long as I had wished because I heard a commotion in the other room. Jumping back out of the shower, I grabbed a robe and wrapped my hair in a towel. As I entered the room, I found Levi clutching a crying Winnie in his arms.

“What’s wrong?” I exclaimed, rushing to her. Levi eyed my robe as it slipped open, and I growled at him.

“There is a man in the refrigerator,” she cried into Levi’s shoulder.

“What!” I said.

“Dylan went over there,” he nodded toward the door.

I went to the door and stared at the trailer across the street. I liked Bethany Jones, but she had issues. I loved her child, Wynonna, and did whatever I could for the angel. However, Winnie recently became more attached to Uncle Levi more than Aunt Grace, which was a blow to my ego.

Opening the door, I started out into the cold in a robe, wet hair and bare feet. Mid-December in Alabama isn’t like in Michigan or Norway. It can actually be very mild, but lately we had frigid temps. Even with the sun rising to its apex, there was a thick layer of frost on the ground.

“You are going to get sick, Grace! Your hair is wet,” Levi shouted at me through the screen door.

“I’m the fucking Ice Queen, Levi!” I shouted back at him, but admonished myself for using the ‘f’ word in front of Winnie. Ice Queen or not, it was freezing. I hurried across the street hearing muffled noises from the trailer. A scream tore through the air, and I sprinted with the bottom of my robe flinging around my legs. Hopefully, the rest of the park was asleep otherwise they probably got a good view.

I stormed into the trailer, finding Dylan on the floor wrestling with a strange looking man. A whole gallon of milk poured onto the linoleum floor as Bethany cowered in the corner. Dylan locked arms with him and forced him to the floor with his knee in the man’s back. The man howled in pain.

“Get down, mother fucker,” Dylan yelled. “Vulgar mouth,” I said as he grimaced at me.

“My Queen,” the man said, ceasing to struggle and putting his face to the floor.

“Oh, hell,” I said. Staring at the man, I realized that his features favored the idiot from the jail last night. His arms were long and gangly. Beady black eyes stared at the floor as he paid reverence to me. I shot a look at Bethany who was actually one of the few complete humans in the town. “Get him out of here, Dylan.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, hauling the fairy man up and dragging him out of the trailer.

“You okay?” I asked Bethany. She nodded silently. “Winnie is with Levi. I don’t suspect she will want to come back for a few hours. We will take the intruder down to the jail, Okay?”

She nodded again as I left the trailer with no other explanation. She looked half out of her mind. I wasn’t sure if it was from the intruder or if she’d had a long drug trip overnight.

As I crossed the road, Dylan threw the idiot into the back of my truck and tied his hands with some rope. “Get some clothes on before you get sick, Grace,” he told me.

“Just a minute,” I said. “Who the hell are you?”

“Your humble servant,” he said, bowing his head.

“Your humble ass is going to sit in the back of my truck until I come back. Got it?” I said.

“Yes, my Queen,” he responded.

Dylan gritted his teeth, staring at me in my robe. “Okay! Okay!” I said flinging my hands up in frustration.

Quickly, I threw on some jeans and a sweater. Adding warm socks and boots to my ensemble, I watched as Levi clicked the television over to cartoons as Winnie sobbed in his arms.

“You okay, Winnie?” I asked her, smoothing her brown hair down with my hand. She still wore a pair of worn princess pajamas and sparkly purple house shoes.

“Yes, Uncle Levi will protect me,” she whimpered.

“Yes, he will. Aunt Grace and Mr. Dylan are going to take the bad man down to the jail,” I said.

“Okay,” she muttered.

“Where’s Kady?” I asked.

“She had to go home last night to prepare for something for church,” he replied. “I’ll stay here with Winnie. We are going to watch cartoons and color.”

“Feed her,” I said. He nodded in response.

Grabbing Dylan’s leather jacket off the back of the couch, I walked through the screen door. Dylan waited for me in the yard. He took the soft leather jacket and shrugged it on. I had found the jacket in my closet after his death. It was a huge comfort to me. It

smelled like Dylan. Leather, peppermint and musk. He watched me staring at the jacket.

“You want it? You know I’ll give it to you,” he said softly.

“No, silly. Just memories,” I said. He grimaced and ran his fingers down my cheek. “I’ll deduct those two seconds from you next request.”

That made him smile. “In that case,” he said, stepping closer to me.

“No, let’s get this jerk wad down to the sheriff,” I pushed him away. Turning to the milk thief, I asked, “So, what’s your name?”

His eyes rose to mine, and he said, “My beautiful Queen, my name is Phil, and I will forever be your servant. You are the sun on a beautiful morning, the air on a crisp day…”

“Yeah, yeah. Clam it up,” I said, shutting him down. “Hope you don’t mind the cold, but you aren’t getting in the cab of my truck.”

“I will be satisfied to just be in your vehicle, my Queen,” he continued.

Dylan chuckled behind me. “Hush your mouth, Dylan,” I said trying not to laugh.

We climbed in the truck, and I let Dylan drive. He was still laughing.

“What the hell is going on in this town?” I asked.

“I don’t know, but it’s hilarious,” he continued.

“Drive, Mr. Riggs,” I said.

“You need a nickname for me,” he said, backing the truck out of the drive.

“Like what?”

“I’d prefer something manly,” he replied.

“Like Pumpkin?” I asked.

“No, not Pumpkin. That’s what a man calls a girl,” he said.

“Well, what do you want me to call you?” I asked.

“I don’t know. You are supposed to pick it out,” he proclaimed.

“How about, Slave?” I asked.

“Keep dreaming,” he said.

“I dream of you quite often,” I replied.

“Gunngh,” he swallowed his words. Without looking at me, I could tell his blue eyes were glittering. “Ahem! Oh, really? I hadn’t realized.”

He made me laugh. “Yeah, sure. 101 ways to torture Dylan Riggs.”

“Aw, Grace. Last night wastorture,” he said.

“What? It’s not my fault that you got lost in the kissing and time ran out. You should use your time more wisely,” I said. We hadn’t been together since that first night a long, long time ago. Three whole months. I desperately wanted him, but for some reason, I kept delaying the inevitable. He certainly had the opportunity last night, but perhaps, I wasn’t the only one timid about renewing our sexual contact.

“If you would just quit playing games and admit that you forgive me, we would both be better off,” he protested.

“Perhaps,” I said.

“Perhaps? Is that all you can say?” Suddenly we weren’t flirting anymore. As his frustration grew, I shrank back into my guarded cocoon. I gritted my teeth, searching for the right words to say, but we had reached our destination. Sitting at the wheel, he waited for me to respond. He slapped it hard with the palm of his hand and climbed out grumbling. As I slid out of my side of the truck, I felt like a piece of crap.

He untied the weird looking fellow and dragged him toward the door of the jail. A couple of deputies standing in the parking lot recognized Dylan.

“Hey, Riggs, you need some help?” one of them called out.

“No, I’ve got it,” he responded hauling the guy to the door. “I need my head examined.”

The strange man started to buck away from Dylan. “No, my Queen, please don’t execute me. These men execute wrong doers.”

“I execute wrong doers,” I spouted at him with more frustration with Dylan than for this crazed fool. “What were you doing in that house?”

“Taking milk,” he responded. “I love milk. I looked at Dylan, and he shrugged.

“You are going inside to think about what you did wrong. You can’t just go into people’s houses and steal milk!” I said.

He hung his head and said, “Yes, my Queen. But I got in trouble once before taking mother’s milk, so I switched to whole cow’s milk.”

“Mother’s milk?” I asked.

“Yes, right from the source,” he cooed.

“Holy hell,” I choked out.

Dylan escorted him into receiving and explained the situation to the desk officer. She was a plump woman with a name tag that said, C. Dawson. “Morning, Carol,” Dylan said.

“What did you drag in here, Dylan Riggs?” she exclaimed, but instead of looking at the man, she flicked her eyes to me. Bitch.

Licking her lips, she fluttered her eyelids at him. The possessive fairy inside me reared her nasty head snarling at Carol Dawson.

I looked at her through my royal fairy sight to determine if she was human or fairy. She glowed green around the edges, so I knew she was a fairy. I was still trying to tell the difference between different types of fairies, but clearly, she belonged to the woodland realm. However, I only glanced at her as my eyes were drawn to the pulsing heat of fire that rolled over Dylan’s form. It was warm and inviting.

I leaned over the counter toward Carol who rolled back in her chair. “Mine,” I growled. She nodded her head as fear filled her eyes. Generally, I made idle threats, but the one I laid on Carol with a single word came from that dark place inside of me.

“Grace?” Dylan said, as an officer took Phil from him, escorting the awkward man to the holding cells.

I shook off the anger and stared back at him. “Sorry. Zoned out,” I said.

“You okay?” he asked suddenly concerned. His frustration washed away like it never happened.

“Yeah, just weird things happening. That’s all,” I explained.

Then we heard a commotion in the holding cells. Dylan rushed to the door. As I followed him closely, the two weird men embraced each other inside the cell.

“Brother!” Lamar said to Phil.

“Brother!” Phil said, patting his brother on the back.

“What the fuck?” I muttered.

“Mouth,” Dylan said.

“Bite me,” I said.

“How long do I have to do that?” he asked. I blushed, turning away from him.

As I walked over to the cell, the officer stood stunned at the two idiots hugging and patting each other. “You are brothers?”

“Oh, my Queen! It’s so good to see you this morning,” Lamar said, without me turning into Gloriana.

“Good morning to you, as well. Did you behave last night? Is the sheriff going to let you leave this morning?” I asked.

“No, I’ve decided to stay with my brother, my Queen. I feel for certain that if you let me out, I would tip more cows,” he explained, scratching his peg leg.

I cocked my head sideways watching him scratch it. Dylan snorted right behind me, and I jumped. “Sorry,” he muttered through laughs.

“This town has gone insane,” I replied.

“It’s always been crazy. You are just now noticing,” he replied.

“Apparently,” I said taking his hand leaving the weird-o brothers behind. As we walked out the door, I cut my eyes to Carol Dawson who stared at us muttering something under her breath.

When we pulled into the drive at the trailer, Dylan sat in the truck and didn’t move. I sighed, knowing he wanted to talk about us.

“Never mind,” he said getting out of the truck.

“Wait, Dylan!” I protested. “Wait, please, say what you were going to say.”

“It’s cold out here, and you’ve already been traipsing around in bare feet. You need to get inside,” he instructed.

“No, come on, I can’t get sick,” I replied.

“Inside!” he demanded, pointing toward the door.

Entering the room, Levi was seated at the table coloring with Winnie. His face flashed with concern when he saw me. I shook my head at him, heading toward my room. “You eat, Winnie?” I asked passing her.

“Yes, ma’am. Uncle Levi made me toast and let me put strawberry jam on it,” she said.

“Yummy,” I replied.

“It was delish,” she replied.

Looking back at Dylan standing at the door, I motioned to my room. He shook his head. “No, I’m going home.”

“Please don’t,” I begged.

“Call you later,” he said, heading back out in the cold.

“What happened?” Levi asked.

Closing my eyes, I wondered if I should chase him. I heard his car rumble to life, and I headed toward the door. Slinging the door open, I paced out on to the wooden deck. He looked up from the dash and pointed back at the trailer. I could see him mouthing the words, “Get back inside!”

“No!” I said with my hands on my hips. He grimaced, pulled out, and sped away.

For the rest of the day I flipped from cussing the day I met Dylan Riggs to being on the verge of tears, thinking he wouldn't come back. I checked my phone every 5 minutes, working myself into a tizzy. For years I’d watched other women do the same thing about a certain man and scoffed at their immaturity, but here I was doing the same damn thing.

Levi played with Winnie most of the day, but before bed, she insisted that she go home. She said her mommy needed her. I winced. A six-year-old child taking care of her mother. The thought just added to my already terrible day.

“You know he will come back,” Levi said.

“One day he won't. He will give up on me,” I replied.

“No, you just need to get over whatever it is holding you back,” Levi said.

“Thank you, love guru,” I snarled.

“Truth hurts,” he said as he went into his bedroom shutting the door.

I stood at the kitchen sink, looking down the road toward town. After an hour, I stopped looking for him and went to bed.

DECEMBER 14TH

AROUND 1 A.M. MY PHONE BUZZED TO LIFE. REACHING OVER IN THE darkness, I plucked it from the nightstand. Mr. Riggs had finally decided to talk to me.

“Are you awake?” the text said.

“Yes,” I responded. Within just a moment, the phone rang. I answered it quickly, “Hello?”

“I’m sorry,” he immediately said. “I’m sorry for everything. I’d do it differently now, Grace. Please, I just…” His voice cut off.

“I’m just afraid, Dylan,” I admitted.

“Open the door,” he said.

“What?” I replied.

“I’m at the front door, and I didn’t want to knock,” he said. I jumped out of bed and ran to the front door. When I let him in, the cold air from outside rushed in. He shut the door behind him, then wrapped me in his arms. The leather jacket was cool, but his hands were warm. Tossing the jacket on the back of the couch, he guided me back to the bedroom, shutting the door behind us.

Leaning against it, he stared at me. “Afraid of what?” he asked.

“Losing you again,” I replied truthfully. “You can die, obviously. But is there a limit? Can you be extinguished?”

“Interesting choice of words,” he replied. “There is no limit, but yes, just like you, I can cease to be. However, it would take the power of a royal fairy to do it or something as strong.”

“Oh,” I said. “I would never.”

“I know,” he said, leaning his forehead to mine. “I need to hear you say it.”

“Say what? What time is it?” I asked.

“Grace, I do not want to play this game,” he said sternly.

Pulling out my phone, I said, “It’s 1:37 am. You have six hours.”

“I want you to say you forgive me. I want forever,” he replied.

Stepping away from him, my heart pounded in my chest. It wasn’t thethree words, but it was pretty darn close. “You admit that this whole queen thing a mess. I don’t want you dragged down by it,” I made up an excuse.

“I do not care, Grace. You stubborn woman!” he exhaled. “You marched into a forest to save a little girl, taking on an Aswang and a werewolf. You stood up to your father, the king of the Wild Fae. How in the world are you afraid of me?”

“I’m not afraid of you,” I muttered.

“Then what are you afraid of?” he begged.

“Us,” I sighed.

“I’m not,” he replied, stepping back towards me. “Forever means I’ll wait that long if I have to.”

“Aw, why do you have to be like that?” I groaned.

“Because, sometimes dealing with stubborn women, the best thing you can do is make her feel bad,” he replied frankly.

“I should slap you,” I said. He turned around and offered his ass. “Oh, stop. I already knew you were an ass.”

He plopped down on the bed, patting the mattress beside him. “Take your shoes off,” I demanded.

“Yes, ma’am” he replied. As he finished, I laid down next to him snuggling up to his warmth. I’d never been sick before, but I had a definite chill from my excursion in the bathrobe. “Grace, you feel warm to me.”

He placed his hand on my forehead. “I think you have a temperature,” he said.

“No, I can’t get sick,” I replied.

“No, you’ve never been sick. Two different things, my dear,” he said. “Just lay here and rest. I’ll take care of you.”

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

And yet from those signs and symptoms the inference which Arthur drew was very decidedly a wrong, or rather an exaggerated, one. Honor was not in the least what is called “in love” with the man whose own passions and wild worship of his neighbour’s wife were making such desperate work within his inner man. Almost utterly reckless had those days of constant communion with her made him. He had cried havoc and let loose the dogs of contending passions within his breast; and if he had ever, when the waves of temptation were beginning to rise and swell, said unto them with an honest and true heart, “So far shalt thou go, and no farther,” that time was long since gone and over, and the submission of Cecil Vavasour’s son to the great enemy of mankind was an accomplished and a melancholy fact. But partly perhaps because the man who really feels an overpowering passion has less chance of moving the object of that passion than has the hypocrite who feigns a devotion which he is far from feeling. Honor Beacham did not, as I said before, love Arthur Vavasour. Like him she did; and greatly did she prize his devotion, his delicate compliments, his evident and irrepressible appreciation of the attractions for which her busy unsophisticated husband, the man whose affections were not for the moment, but for Time, appeared to care so strangely little. But although the eloquent blood that rose to neck and brow had not its source in the inner, and to Arthur the undiscovered, depths of her affection, although the visible palpitations of her heart could not with truth be traced to the consciousness of harbouring one unholy or forbidden thought, still Arthur’s words and sighs and glances produced upon this child of nature effects precisely analogous to those which might have been displayed had the love which he professed and felt been returned tenfold into his bosom.

“I did not mean to be unkind and cold,” she stammered. “Quiet, Nellie!” (to the mare she rode, and whose mild caracoles her own agitation was provoking). “It was all my fault for talking about going home; and, Mr. Vavasour—”

“Call me Arthur,” he broke in impetuously; “even you, who grudge me every word that is not stiff and formal, even you can see no harm in—when we are alone together—calling me by my name? Honor, I—”

She put up a warning finger, smiling as she did so after a fashion that would have turned a steadier head than Arthur Vavasour’s. She did not mean to be “coquettish;” there was no purpose in her heart to lure him into folly and madness. Honor’s were very simple, but at the same time very

cowardly, tactics—tactics, however, which have lost ere this more silly giddy women than even vanity itself. In public glad to please, and feeling, really feeling pity for the man whose passion she understood without reciprocating it, Honor would “smile, and smile, and smile,” and seem to love; whilst in private—but then, to the best of her powers, and with an ingenuity of which none but a frightened woman could have been capable, she strove, and with good success, to postpone sine die the evil hour when she would perforce be brought to book, and when the lover whose attentions she would be more loth to lose than she the least suspected would insist on the decided answer which would render further trifling impossible —in private Honor might almost have been mistaken for a prude.

“How can you want me to call you Arthur,” she said, with the bright smile that lit up her countenance like a sunbeam, “when you know it would be wrong—so wrong (and that is the best way to find out what is wrong) that you would, or I should, be always in a most dreadful fright lest I should forget myself, and say it when other people were present? O, how I do hate doing underhand things! I wish now, only it is days and days too late, that I had written everything I was about to the Paddocks. Then they might have abused me for being wilful and fond of London, and plays, and amusing things; but they could not have hated and despised me for being false.”

“But,” said Arthur with a caress in his voice, which Honor, novice though she was, was at no loss to feel and understand—“but there are so many things which pass, that one cannot say to everyone—many things which are not wrong, as you call it, but which people at a distance would not enter into, and had better therefore know nothing about. And so they have been worrying you with letters, you poor darling, have they? Wanting you to go back, and—”

“O, yes,” Honor cried, brimming over with her wrongs, her yearning for kind sympathy, and with the self-pity which ever exaggerates the misfortunes which our precious self is called upon to endure—“O, yes, and Mrs. Beacham—she is so disagreeable; you don’t know half how disagreeable she can be, orders me to come home, and threatens me with all sorts of horrid things. I am to be scolded and taught my duty, and,” blushing beautifully, “someone has told them that I have been riding in the Park with you, and—Ah, Mr. Vavasour, I feel quite frightened, and I would rather do anything in the world almost than go back again to the Paddocks!”

“Anything?” he asked, throwing as much meaning into the word as the human voice was capable of expressing; but Honor, who was far as the poles from comprehending the evil that was in his thoughts, said eagerly,

“Indeed yes! anything! I would be a governess—you know I was a governess before—I would go out to service—be a ‘Lydia,’ ” and she smiled a little bitterly, “if I could only never, never see Mrs. Beacham’s face again.”

An expression which she took for amusement, but which was in reality indicative of very unholy triumph, passed over Arthur Vavasour’s dark, handsome face.

“Don’t laugh at me,” Honor said plaintively. “You can have no idea how hard it is to live with John’s mother. Nothing I do is right, and—and,” in a lower voice, “I know she sets him against me. She has written to tell me that I must go home to-day; but my father says I am to lay our not going upon him, so here I shall stay! I know I shall be in a dreadful scrape, and that it is only a case of putting off, and—”

“But why only a case of putting off, as you call it? My darling Honor— forgive me; the words slipt out unawares—you know I would not offend you willingly; but the best as well as the worst men are liable to mistakes. Only tell me why you, so young, so beautiful, so formed for the enjoyment of everything that is bright and happy, should be condemned to pass your days in such an existence as the one you describe at the Paddocks? It has always seemed to me,” he went on, leaning towards her, and looking with eyes of eager passion into her face—“it has always seemed to me an act of the most miserable folly for people—married people—who do not suit, remaining together: both would often be equally glad to part, to go their respective ways, to live another and a more congenial life; and yet from some foolish unreasoning scruple, from fear of what the world would say, or from want of courage to take the first step, they go on through all their lives, making each other’s existence a burden, ‘when both might separately have been as happy’ as we are any of us fated to be in this ill-managed world of ours, where happiness is so rare a thing.”

Honor glanced at him with rather a puzzled look in her blue eyes. Strange as it may seem, she did not even now comprehend his meaning. That he was advising her to leave her home was too plain to be mistaken, but that there was to be sin—sin, that is to say, greater than that which she

could not but feel would be incurred by deserting her husband and her duties—never occurred to this poor foolish child of nature. But although she did not comprehend, and could not fathom, the depths of her false friend’s guilt, yet her womanly instinct led her to evade the responding to his suggestion. His last words also, and the tone of sadness in which they were spoken, riveted her attention, and, catching almost gladly at an excuse for changing the conversation, she said sympathisingly,

“What do you mean by ill-managed? Surely you can have no reason to think this world an unhappy one! If there exists one person in it who ought to be happy, it is you—you and your wife,” she added, with a little sigh which again misled her companion into a blind and senseless belief in his own power over her affections. “You have everything, it seems to me, that human beings can hope for or desire—youth and health and riches, living where you like, and always seeing and enjoying the beautiful things that money can buy; and then going abroad, seeing foreign countries, and—and —”

“And what? Tell me some more of my privileges, my delights; make me contented, if you can, with my lot. At present it seems dark enough, God knows; and if—but I am a fool, and worse, to talk to you of these things; only, if I thought that you—you, who are an angel of purity and love and peace—would sometimes think of me with pity, why, it would give me courage, Honor, would make me feel that I have still something to live for, something to bind me to an existence which I have begun to loathe!”

Honor listened to this outpouring of real or fancied sorrows like one who is not sure whether she dreams or is awake.

“Mr. Vavasour!” she exclaimed, “what can you mean? At your age, with a young wife who loves you, and with” (blushing slightly) “the hope of the dear little child that will so soon be born, it seems so wonderful to hear you talk in this way! What is it?” warming with pity as she watched the young worn face prematurely marked with lines of care—“would you like to tell me?—I am very safe. I have no one” (sadly) “to confide in; and you have just said that my sympathy would be a comfort to you.”

She laid her little ungloved hand—she had taken off her gauntlet to caress the arched neck of the pretty thoroughbred screw she rode—upon her companion’s arm as she spoke, and so fully occupied was she with her object (namely, that of inducing Arthur to trust her with his sorrows), that

she was scarcely conscious of the warmth with which he, pressing his hand upon the caressing fingers, mutely accepted the tribute of her sympathy.

“Ah, then,” she said—the slight soupçon of a brogue, as was often the case when she was eager or excited, making itself apparent—“ah, then, you will remember I am your friend, and say what it is that lies so heavy on your heart?”

For a moment he looked at her doubtingly; and then, as though the words broke from him as in his own despite, he said in a low husky tone:

“What purpose would it answer, what good would it effect either for you or me, were you to learn that I am a villain?”

CHAPTER VII.

MEA CULPA.

A �������! Arthur Vavasour—the “fine,” noble-hearted, brilliant gentleman to whom this simple-minded Honor had so looked up, and of the loss of whose friendship she had been so afraid that she had “led him on”—the silly woman knew she had—to fancy that she loved him better than she did her husband—was he in very truth a man to be avoided, shunned, and looked on with contempt? She could not, did not think it possible. He was accusing himself unjustly, working on her compassion, speaking without reflection: anything and everything she could believe possible rather than that her friend should deserve the odious epithet which had just, to her extreme surprise, smote upon her ears. Before, however, she could give words to that surprise, Arthur spoke again, and with an impetuosity which almost seemed to take away his breath poured forth his explanation of the text.

“Yes, a villain! You may well look astonished; and I expect, when you know all, that you will turn your back upon me, Honor, as all the world must; that is, if the world has to be taken into my confidence, which I still trust it will not be. There are extenuating circumstances though, as the juries say; and perhaps, if I had been better raised, I shouldn’t have turned out such an out-and-out bad ’un as I have!”

He stopped for a moment to gulp down a sigh, and then proceeded thus:

“I think I told you once before how awfully I was in debt, and that it was the burden of debt that drove me into marrying poor little Sophy Duberly— the best girl in the world; but I did not love her (more shame for me), and whose affection, poor child, is so much more of a torment than a pleasure to me. Well, enough of that: the worst is to come; and if you can tell me, after hearing it, that I am not a villain, why, I am a luckier dog, that’s all, than I think myself at present!”

Honor, feeling called upon to make some response, muttered at this crisis a few words which sounded like encouragement; but Arthur, too entirely engrossed with his mea culpa to heed this somewhat premature absolution, continued hurriedly to pour forth the history of his sin.

“You would never believe, you who are so young, so ignorant of the world’s wickedness, what the temptations are which beset a man. Pshaw! I was a boy when I began life in London, and there were no bounds to my extravagance, no limits to what you in your unstained purity would call my guilt. I sometimes think that had my poor father lived, or even if I had possessed a dear mother whose heart would have been made sore by the knowledge of my offences, I might (God knows, however; perhaps I was bad in grain) have sinned less heavily, and have been this day unburdened by the weight of shame that oppresses me both by night and day. Darling Honor!—you sweet warm-hearted child! why were there no loving eyes like yours to fill with tears, in the days gone by, for me? In those days only guilty women loved, or seemed to love; and not a single good one prayed for or advised me. And so—God forgive me!—I went on from bad to worse! For them—for those worthless creatures whose names should not be even mentioned in your hearing—I expended, weak vain idiot that I was, thousands upon thousands, which, being under age, I raised from Jews at a rate so usurious that it could scarcely be believed how they could dare to ask, or any greenhorn be such a fool and gull as to accept, the terms. And then, reckless and desperate, afraid to confide in the mother who had never shown me a mother’s tenderness, I played—I betted on the turf—I—in short, there is no madness, no insane extravagance, of which, in my recklessness and almost despair, I have not been guilty. But the worst is yet to come. You remember that I bought Rough Diamond for a large sum of your husband. I gave him a bill at six months’ date, renewable, for the amount; and John—he behaved as well as man could do, I must say that— promised that it should remain a secret that the colt was mine. Well, some little time before my marriage—that marriage being a matter to me of absolute necessity—old Duberly grew anxious and uneasy at my being so much at the Paddocks. He had an idea, poor dear old fellow, that I could only be there on account of matters connected in some way with racing. So he wrote to my mother, of all people in the world, for an explanation, and she naturally enough referred him to me. Then, Honor, came the moment of temptation. I could not—I positively could not, with my expectations, my almost certainty, and John Beacham’s too, of Rough Diamond’s powers— part with him to any man living. So—it was an atrocious thing to do; I felt it at the moment, and Heaven knows I have not changed my opinion since—I

allowed Mr. Duberly—allowed! humbug!—I told him that the horse was not mine, and, liar that I was, that I had nothing to do with the turf!”

“It was very bad,” murmured Honor; “but I suppose that if Mr. Duberly had thought the contrary, he might have refused his consent to your marriage, and then his daughter would have been wretched. Still, indeed, indeed, you had better—don’t you think so now?—have been quite open with him. If you had said—”

“Yes, yes, I know; but who ever does the right thing at the right time? And, besides, I could not be sure, as you have just said, and knowing old Duberly as I do now, that he would have allowed his daughter to be my wife if he had been told the truth. His horror of what he calls gambling is stronger than anything you can conceive. I hear him say things sometimes which convince me that he would rather have given Sophy to a beggar—a professional one, I mean—than to me; and if he had acted as I feared, what, in the name of all that is horrible, was to become of me? The tradesmen, the name of whose ‘little accounts’ is legion, only showed me mercy, the cormorants! because of the rich marriage which they believed was to come off; while the Jews, the cent-percent fellows—but what do you know of bills and renewals, of the misery of feeling that a day of reckoning is coming round—a horrible day when you must either put the gold for which those devils would sell their souls into their grasping hands, or by a dash of your pen plunge deeper and deeper into the gulf of ruin and despair? But there are other and more oppressive debts even than these, Honor—debts which I have no hopes of paying, except through one blessed chance, one interposition of Providence or fate—for I don’t suppose that Providence troubles itself much with my miserable concerns—in my behalf.”

“And that chance?” put in Honor, imagining that he waited to be questioned.

“That chance is the winning of the Derby to-morrow by Rough Diamond. I have no bets, at least nothing but trifling ones, on the race; but if the horse wins, his value will, as of course you know, rise immeasurably, and with the money I can sell him for I shall be able, for a time, to set myself tolerably straight. Your father—whose horse you have, I suppose, hitherto fancied Rough Diamond to be—has, he tells me, backed him for all that he is worth. My reason for not doing so has been that I am not up to making a book, and that the debts of honour I already groan under are

sufficiently burdensome without incurring others which I might not be able to pay.”

“How anxious you must be and unhappy!” Honor said pityingly. “But there is one thing which puzzles me, and that is, how you could keep all this a secret from your wife. Surely she would have been silent; surely she might have softened her father, and made all smooth between you.”

“She might; but I could not risk it. Sophy is very delicate; and then there has been such entire confidence between her and her father, that it would have been almost impossible for her to keep anything from him. No; as I have brewed, so I must bake. I can only hope the best; and that, or the worst, will very soon be no longer matter for speculation. The devil of it is —I beg your pardon, I am always saying something inexcusable—but really the worst of it is, that the fact of my mother’s intention of fighting my grandfather’s will is no longer a mystery. Old Duberly’s fortune is, as all the world believes, very large; but at the same time he is known to be what is called a ‘character,’ and that his eccentricities take the turn of an extraordinary mixture of penuriousness and liberality has been often the subject both of comment and reproach with people who have nothing to do but to talk over the proceedings of their neighbours. In short—for I am sure you must be dreadfully tired of hearing me talk about myself—the world, my cursed creditors included, would be pretty well justified in believing that my worthy father-in-law would flatly refuse to pay a sum of something very like fourteen thousand pounds for a fellow whose extravagance and love of play were alone accountable for the debt; one, too, who has nothing —no, not even a ‘whistle’—to show of all the things that he has paid so dear for. Disgusting, is it not? And now that you have heard the story,—I warned you, remember, that it was a vile one,—what comfort have you to bestow on me? And can you, do you wonder at my calling the world—my world, that is—a miserable one? and is it surprising that, in spite of outward prosperity, of apparent riches, and what you call good gifts, I should sometimes almost wish to exchange my lot with that of the poorest of the poor, provided that the man in whose shoes I stood had never falsified his word, or lived as I have done and do, with a skeleton in the cupboard, of which another—one, too (forgive me, dear, for saying so), whom I not greatly trust—keeps, and must ever keep, the key?”

Honor paused for a moment ere she answered, and then said, in a gentle and half-hesitating way (they had turned their horses’ heads some time

before, and had nearly arrived at Honor’s temporary home), “I almost wish you had not told me this; but we are neither of us very happy, Mr. Vavasour, and must learn to pity one another. Perhaps—I don’t know much about such things—but perhaps I ought to say that you were wrong; only, I am sure of this, that, tempted as you were, I should have done no better. It must have been so very difficult—so very, very frightening! In your place I should never have had courage enough to speak the truth; and I hope—O, how I hope!—both for your sake and my father’s, that your horse may win! But am I to say,” she whispered, as with his arms clasped round her slender waist he lifted her from the saddle, “am I to say to him, to my father, that I know about Rough Diamond? I should be so sorry, from thoughtlessness, to repeat anything you might wish unsaid.”

He followed her into the narrow passage, where for a single moment they were alone, and the craving within him to hold her to his heart was almost beyond his power to conquer. Perhaps,—we owe so much sometimes to simple adventitious circumstances,—but for the chance opening of a door on the landing-place above, Honor would at last have been awakened to the danger of treating Arthur Vavasour as a friend. She was very sorry for him; but she would have been more distressed than gratified had he pressed her to his heart with all the fervour of youthful passion, and implored her to trust herself entirely to his tender guardianship. On the contrary, seeing that he simply asked if Mrs. Norcott were at home, and reminded Honor of her wish to see the famous chestnut avenue, and of the practicability of realising her wishes, pretty Mrs. John Beacham tripped upstairs before him with a lightened heart, in search of the chaperone who was ever so good-naturedly ready to contribute to her pleasures.

CHAPTER VIII.

JOHN BEACHAM MAKES A DISCOVERY.

P�����, especially imaginative ones, are apt to talk a good deal about coming shadows and presentiments of evil, becoming especially diffuse on the subject of the low spirits which they feel or fancy they have felt previous to any great and dire calamity. In my humble opinion such warnings lie entirely in the imagination, and, moreover, those who prate about this gift of second sight are apt to forget the million cases of unannounced misfortunes to be set against the isolated instances of anticipated evil. Amongst these million cases we may safely cite that of Honor Beacham on the afternoon of that famous Tuesday when, with complaisant Mrs. Norcott for her duenna, she strolled with Arthur Vavasour under the avenue of arching trees, then in their rich wealth of snowy beauty, which leads, as all the world well knows, to

“The structure of majestic frame Which from the neighbouring Hampton takes its name ”

Had Honor either been a few years older, less constitutionally light of heart, or more experienced in sorrow, she would never have been able so entirely—as was the case with this giddy young woman—to cast off the sense and memory of her woes. A reprieve after all is but a reprieve; and the consciousness that each moment, however blissful, serves only to bring us nearer to its termination, ought to and does fill the minds of the thoughtful with very sobering reflections. But, as I have just remarked, Honor’s constitutionally happy spirits buoyed her up triumphantly on the waters whose under-swell betokened a coming tempest, and throughout the two swiftly-passing hours which she spent in the beautiful park with Arthur Vavasour by her side, she, recklessly setting memory and conscience at defiance, was far happier than she deserved to be.

The “pale and penitential moon” was rising over the Hyde-Park trees as the open carriage drove into Stanwick-street, and Honor, half pale and remorseful too now that the hour was drawing near when she must think, promised, in answer to Arthur’s whispered entreaty, that no commands, no

fatigue, no dangerous second thoughts, should cause her to absent herself that night from the theatre, where she was to enjoy one of their last pleasures, he reminded her, together. She ran upstairs—a little tired, flushed, eager, beautiful. Would there be—she had thought more than once of that as they drove homewards—would there be any letter for her upon the table in the little sitting-room where what Mrs. Norcott called a “heavy tea” was set out for their delectation? Would there—she had no time to speculate upon chances; for her quick eye soon detected a business-likelooking missive directed to herself, and lying on the table in front of her accustomed seat.

With a feeling of desperation—had she delayed to strive for courage the letter would probably, for that night at least, have remained unread—she tore it open and perused the following lines, written in her husband’s bold, hard, rather trade-like writing, and signed by the name of John Beacham:

“D��� H����,—I suppose you have some excuse to make for yourself, though I can see none any more than my mother does. You seem to be going on at a fine rate, and a rate, I can tell you, that won’t suit me. I have been at the house you lodge at to tell you that I shall take you home with me to-morrow; so you had better be ready early in the day. My mother thinks you must have been very badly brought up to deceive us as you have done, and it will be the last time that I shall allow you to spend a day under your father’s roof.”

Poor Honor! Poor because, tottering, wavering between good and ill, it required but a small impetus, given either way, to decide her course. If it be true (and true indeed it is) that grievous spoken words are wont to stir up anger, still more certain is it that angry sentences written in moments of fierce resentment, and read in a spirit of rebellion and hurt pride, are apt to produce direful consequences. When Honor, with the charm of Arthur Vavasour’s incense of adulation still bewildering her brain, and with the distaste which the memory of old Mrs. Beacham’s society inspired her with strong upon her, read her husband’s terse and unstudied as well as not particularly refined epistle, the effect produced by its perusal was disastrous indeed. Dashing the passionate tears from her eyes, and with a wrench throwing off the dainty little bonnet and the airy mantle in which Arthur Vavasour had told her she was so exquisitely “got up,” she prepared herself to meet again at the New Adelphi the man whose influence over her, aided

by the unfortunate circumstances in which she was placed, had more than begun to be dangerous. On that night, her last night—but—and here Honor laid down the brush with which she was smoothing out her rich rippling tresses—but must it be indeed, she asked herself, the last night that she would be free? The last night that she might hope to pass away from the wretched thraldom, the detested daily, hourly worry of her unloved and unloving mother-in-law? Must she indeed return (and at the unspoken question her heart beat wildly, half with terror and half with the joyful flutter of anticipated freedom), must she obey the order—for order it was, and sternly, harshly given—to place herself once more in Mrs. Beacham’s power, in the home which that domineering and unkind old woman had rendered hateful to her?

To do Honor only justice, there was no glimmering, or rather, to use a more appropriate word, no overshadowing, of guilt (of guilt, that is to say, as regarded the straying of the thoughts to forbidden pleasures) in her desire —a desire that was slowly forming itself into an intention—of making a home for herself elsewhere than at the Paddocks. She had arrived, with the unreflecting rapidity of impulsive youth, at the decision that John had ceased to love, and was incapable of appreciating either her beauty or her intellect. His mother, too—and in this decision Honor was not greatly in the wrong—wished her anywhere rather than in the house where she had been accustomed to reign supreme; and this being the case, and seeing also that poor Honor could expect (for did not those two threatening letters proclaim the fact?) nothing but unkindness on her return, there remained for her only the alternative—so at least she almost brought herself to believe—of separating herself from those with whom she lived in such continued and very real unhappiness.

During all the time that was employed in tastefully arranging the hair whose rich luxuriance scarcely needed the foreign aid of ornament, and in donning the dress fashioned after the décolletée taste of the day, but which Mrs. Norcott—who entertained an unfortunate fancy, common to bony women, of displaying her shoulders for the public benefit—assured her was the de rigueur costume for the theatre,—during all the time that Honor was occupied in making herself ready for the evening’s dissipation, the idea of “living alone” haunted and, while it cheered, oppressed her. Of decided and fixed plans she had none; and whether she would depart on the morrow, leaving no trace to follow of her whereabouts, or whether she would delay

her purpose till a few days should have elapsed after her enforced return to Pear-tree House, were subordinate arrangements which this misguided young woman told herself that she would postpone for after consideration. For the moment, the prospect of listening to the most exciting of dramas, and of seeing (for she was easily pleased) the well-dressed audience of a popular theatre, bore their full share in causing the future, as it hung before Honor’s sight, to be confused and misty. The convenient season for thought was to be after this last of her much-prized pleasures; and when this bouquet of the ephemeral delights by which her senses had been so enthralled would be a memory and a vision of the past, the young wife told herself that the time for serious reflection should begin.

An hour later, in a box on the pit tier, listening with every pulse (for Honor was too new and fresh not to take an almost painful interest in the half-tragic and perfectly-acted play) beating responsive to newly-aroused sensations, the young wife of the Sandyshire farmer attracted a good deal more attention and admiration than she—entirely engrossed with the scene and the performance—could, vain daughter of Eve though she was, have supposed to be possible. Her dress, made of inexpensive materials, but of pure, fresh white, and unadorned, except with a bunch of pale-blue convolvulus, matching another of the same flower in the side of her small, fair head, was a triumph of unpretending simplicity. Alas, however, for the fashions of these our days! For well would it have been—before one pair of eyes, gazing on Honor’s attractions from the pit, had rested on her beauty— could some more efficient covering than the turquoise cross, suspended from her rounded throat by a black velvet ribbon, have veiled her loveliness from glance profane! Honor little knew—could she have had the faintest surmise that so it was, her dismay would have been great indeed—Honor little knew whose eyes those were that for a short ten minutes—no more— were riveted, with feelings of surprise and horror which for the moment almost made his breast a hell, upon the box in which she was seated. John Beacham—for the individual thus roused to very natural indignation was no other than that much-aggrieved husband—had learned from chattering Lydia, on his visit to Stanwick-street, that Mrs. Beacham was on that evening to betake herself to the New Adelphi with—the name went through honest John’s heart like a knife—Mr. Vavasour and Mrs. Norcott. They were gone—“them three,” Miss Lydia said—to “ ’Ampton Court” for the afternoon; but the Colonel—he was expected back before the others.

Perhaps the gentleman—the parlour-maid was totally ignorant of the visitor’s right to be interested in Mrs. John Beacham’s movements— perhaps the gentleman would wait, or it might be more convenient to him to call again when the Colonel would have come back from the races. She didn’t believe that Colonel Norcott would go to the theatre. She’d heard some talk of his going to the club; but if—

John, who had heard with dilated and angry ears the main points of these disclosures, and who was very far from desiring to come in contact with the man whom upon earth he most despised and disliked, waited to hear no more, but, striding hastily away, surrendered himself, not only to the gloomiest, but to the most bitter and revengeful thoughts. That this man— unsuspicious though he was by nature, and wonderfully ignorant of the wicked ways of a most wicked world—should at last be roused to a sense of the terrible possibility that he was being deceived and wronged was, I think, under the circumstances, only natural; and in proportion to the man’s previous security—in proportion to his entire trust, and complete deficiency of previous susceptibility regarding Honor’s possible shortcomings—was the amount of almost uncontrolable wrath that burned within his aching breast. For as he left that door, as he walked swiftly down the street, and remembered how he had loved—ay, worshipped—in his simple, inexpressive way, the lovely creature who was no longer, he feared, worthy either of his respect or tenderness, no judgment seemed too heavy, no punishment too condign for her who had so outraged his feelings and set at naught his authority. Full of these angry feelings, and boiling over with a desire to redress his wrongs, John Beacham repaired to the tavern where he was in the habit, when chance or business kept him late in London, of satisfying the cravings of hunger. Alone, at the small table on which was served to him his frugal meal of beefsteak and ale, John brooded over his misfortunes, cursing in bitterness of spirit the hour when he first saw Honor Blake’s bewildering face, and exaggerating—as the moments sped by, and his blood grew warmed with one or two unaccustomed “tumblers”—the offences of which she had been guilty.

He was roused from this unpleasant pondering by the clock that ticked above the tall mantelshelf of the coffee-room sounding forth the hour of eight. Eight o’clock, and John, who never passed a night if he could help it in London, had not yet made up his mind where to spend the hours which must intervene before his morning meeting with his wife. Enter the doors of

Colonel Norcott’s abode—save for the purpose of carrying away the headstrong, deceitful girl whom he, John’s enemy, had so meanly entrapped —the injured husband mentally vowed should be no act of his: not again would he trust his own powers of self-command by finding himself, if he knew it, face to face with the object of his hatred. From the hour, and to that effect he registered a vow—from the hour when he should regain possession of his wife, all communication of every kind whatsoever should cease between Honor and the bold bad man in whose very notice there was contamination and disgrace. From henceforward Honor, so he told himself, would find a very different, and a far less yielding, husband than the fool who had shut his eyes to what his mother’s had so plainly seen. Henceforward the young fop and spendthrift, whom for the boy’s father’s sake he had encouraged to visit at his house, should find it less easy to make an idiot of him. Henceforward—but at this point in his cogitation a sudden idea occurred to him; it was one that would in all probability have struck him long before, and would certainly have shortened the modest repast over which he had been lingering, if he had entertained—which certainly was not yet the case—any doubts and suspicions of a really grave character relative to Arthur Vavasour’s intimacy with his wife. That she had deceived him with any design more unpardonable than that of temporarily amusing herself was a thought that had not hitherto found a resting-place within the bosom of this unworld-taught husband; though that Honor had so deceived him was a blow that had fallen very heavily upon him. Thoroughly truthful in his own nature, and incapable of trickery, he had been so startled and engrossed by the discovery in Honor’s mental idiosyncrasy of directly opposite qualities, that for a while he was incapable of receiving any other and still more painful impression concerning her. To some men—especially to those unfortunately-constituted ones who see in “trifles light as air” “consummation strong” of their own jealous fantasies— it may seem strange that John Beacham should not have sooner taken the alarm, and vowed hot vengeance against the destroyer of his peace. That he had not done so was probably owing to a happy peculiarity in his constitution. He was a man too well aware of his own hasty temperament to rush without reflection into situations to which I can give no better or more expressive name than that of scenes. To quarrel with, also, or to offend the son of Cecil Vavasour would have been a source of infinite pain to the man whose respect and affection for his dead landlord would end but with his

life; his wish, therefore, that Arthur had been and was no more to Honor than the companion, in all innocence, of her girlish follies, was the father to the conjecture as well as to the belief that so it was.

Probably, had John been returning for business purposes that day to the Paddocks, the idea which did then and there occur to him, of hurrying off to the New Adelphi, in order to judge for himself—as if in such a case any man could judge justly!—of Honor’s conduct and proceedings, would never have entered his head. It was a sore temptation only to look again, sooner than he had expected, at his wife’s beautiful face; and as, in memory as well as in anticipation, he dwelt upon it, the strong man’s heart softened towards the weak child-like creature whom he had sworn to honour as well as to love, and it would have required but one smile from her lips, one pressure of her tender arms, to persuade him once again that she was perfect, and that if fault or folly there had been, the error lay in himself alone.

Perhaps in all that crowded house—amongst that forest of faces that filled the boxes and gallery to the roof—there was not one, save that honest countryman, whose attention was not fixed and absorbed that night on one of the most sensational melodramas that have ever drawn tears from weak human eyes. At another time and under other circumstances John Beacham who, strong-bodied and iron-nerved man though he was, could never keep from what he called making a fool of himself at a dismal play, would not have seen unmoved the wondrous tragic acting of one of the very best (alas, that we must speak of him in the past!) of our comic actors: but John Beacham, on the night in question, was not in the mood to listen with interest to the divinest display of eloquence that ever burst from human lips. He was there for another and less exalted purpose: there as a spy upon the actions of another—there to feast his eyes (for, as I said before, in spite of all her errors, his heart was very soft towards the one woman whom he loved) on the wife who had defied his authority, and, possibly, made him an object of ridicule.