Thought A Reader Second Edition Steven G Medema Warren J

Samuels

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/the-history-of-economic-thought-a-reader-second-edit ion-steven-g-medema-warren-j-samuels/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Age of Fragmentation A History of Contemporary Economic Thought 1st Edition Alessandro Roncaglia

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-age-of-fragmentation-ahistory-of-contemporary-economic-thought-1st-edition-alessandroroncaglia/

A History of Colombian Economic Thought : The Economic Ideas that Built Modern Colombia 1st Edition Andrés Álvarez

https://textbookfull.com/product/a-history-of-colombian-economicthought-the-economic-ideas-that-built-modern-colombia-1stedition-andres-alvarez/

The Cambridge History of Modern European Thought The Twentieth Century Peter E Gordon Warren Breckman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-cambridge-history-of-moderneuropean-thought-the-twentieth-century-peter-e-gordon-warrenbreckman/

The Cambridge History Of Modern European Thought The Nineteenth Century Peter E Gordon Warren Breckman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-cambridge-history-of-moderneuropean-thought-the-nineteenth-century-peter-e-gordon-warrenbreckman/

A History of Economic Thought in France : The Long Nineteenth Century 1st Edition Gilbert Faccarello

https://textbookfull.com/product/a-history-of-economic-thoughtin-france-the-long-nineteenth-century-1st-edition-gilbertfaccarello/

History of Economic Thought 3rd Edition E.K. Hunt And Mark

https://textbookfull.com/product/history-of-economic-thought-3rdedition-e-k-hunt-and-mark/

The Peking Gazette A Reader in Nineteenth Century Chinese History Lane J Harris

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-peking-gazette-a-reader-innineteenth-century-chinese-history-lane-j-harris/

New Ideas from Dead Economists The Introduction to Modern Economic Thought 4th Edition Todd G. Buchholz

https://textbookfull.com/product/new-ideas-from-dead-economiststhe-introduction-to-modern-economic-thought-4th-edition-todd-gbuchholz/

Militarization A Reader Roberto J. González

https://textbookfull.com/product/militarization-a-reader-robertoj-gonzalez/

The History of Economic Thought

From the ancients to the moderns, questions of economic theory and policy have been an important part of intellectual and public debate, engaging the attention of some of history’s greatest minds. This book brings together readings from more than two thousand years of writing on economic subjects. Through these selections, the reader can see first-hand how the great minds of the past grappled with some of the central social and economic issues of their times and, in the process, enhanced our understanding of how economic systems function.

This collection of readings covers the major themes that have preoccupied economic thinkers throughout the ages, including price determination and the underpinnings of the market system, monetary theory and policy, international trade and finance, income distribution, and the appropriate role for government within the economic system. These ideas unfold, develop, and change course over time at the hands of scholars such as Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas, John Locke, François Quesnay, David Hume, Adam Smith, Thomas Robert Malthus, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, William Stanley Jevons, Alfred Marshall, Irving Fisher, Thorstein Veblen, John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, and Paul Samuelson. Each reading has been selected with a view to both enlightening the reader as to the major contributions of the author in question and to giving the reader a broad view of the development of economic thought and analysis over time.

This book will be useful for students, scholars, and lay people with an interest in the history of economic thought and the history of ideas generally.

Steven G. Medema is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colorado, Denver. He is the author of The Hesitant Hound: Taming Self-Interest in the History of Economic Ideas and also Editor of Historians of Economics and Economic Thought and Economics Broadly Considered—both published by Routledge.

Warren J. Samuels was Professor Emeritus of Economics at Michigan State University, USA. He was the author of a host of classic books on the history of economic thought including The Classical Theory of Economic Policy, Pareto on Policy, and Erasing the Invisible Hand. He died in August 2011.

This page intentionally left blank

The History of Economic Thought

A Reader

Second edition

Edited by Steven G. Medema and Warren J. Samuels

First edition published 2003

Second edition published 2013 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 collation and editorial material, Steven G. Medema and Warren J. Samuels; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of the editors to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-0-415-56867-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-415-56868-5 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-203-56847-7 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman by Sunrise Setting Ltd, Paignton, UK

For Alex and Christopher, and for Michelle, in the hope that they, too, will come to love the world of ideas

This page intentionally left blank

6

Nichomachean Ethics (350 BC) 16

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

Summa Theologica (1267–1273) 21

Thomas Mun (1571–1641)

England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade (1664) 37

William Petty (1623–1687)

A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions (1662) 53

John Locke (1632–1704)

Of Civil Government (1690) 66

Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money (1691) 70

Richard Cantillon (1680?–1734)

Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General (1755) 88

François Quesnay (1694–1774)

Tableau Économique (1758) 108

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727–1781)

Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1770) 116

Bernard Mandeville (1670–1733)

The Grumbling Hive: Or, Knaves Turn’d Honest (1705) 132

David Hume (1711–1776)

Political Discourses (1752): “Of Money” 148

“Of Interest” 153

“Of the Balance of Trade” 159

Adam Smith (1723–1790)

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) 171

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832)

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789) 200

A Manual of Political Economy (1795) 203

Anarchical Fallacies (1795) 205

Principles of the Civil Code (1802) 209

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834)

An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) 213

Henry Thornton (1760–1815)

An Enquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain (1802) 228

David Ricardo (1772–1823)

The High Price of Bullion (1810) 244

Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832)

A Treatise on Political Economy (1803) 256

David Ricardo (1772–1823)

On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) 268

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834)

Principles of Political Economy (1820) 304

James Mill (1773–1836)

Elements of Political Economy (1821) 325

Nassau W. Senior (1790–1864)

An Outline of the Science of Political Economy (1836) 332

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

Principles of Political Economy (1848) 351

PART III

Karl Marx (1818–1883)

A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) 394

Das Kapital (1867) 397

IV

Jevons (1835–1882)

The Theory of Political Economy (1871) 434

Carl Menger (1840–1921)

Principles of Economics (1871) 465

Léon Walras (1834–1910)

Elements of Pure Economics (1874) 485 Francis Ysidro Edgeworth (1845–1926)

Mathematical Psychics (1881) 502 Alfred Marshall (1842–1924)

Principles of Economics (1890) 529

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914)

The Positive Theory of Capital (1888) 550

V

(1851–1926)

“The Influence of the Rate of Interest on Prices” (1907) 585

Irving Fisher (1867–1947)

The Purchasing Power of Money and Its Determination and Relation to Credit Interest and Crises (1911) 592

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946)

“The End of Laissez-Faire” (1926) 622

“The General Theory of Employment” (1937) 626

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) 634

Thorstein B. Veblen (1857–1929)

The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) 645

John R. Commons (1862–1945)

“Institutional Economics” (1931) 683

Milton Friedman (1912–2006)

“The Methodology of Positive Economics” (1953) 695

Paul A. Samuelson (1915–2009)

“The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure” (1954) 714

“Diagrammatic Exposition of a Theory of Public Expenditure” (1955) 718

A.W. Phillips (1914–1975)

“The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957” (1958) 730

Milton Friedman (1912–2006)

“The Role of Monetary Policy” (1968) 747

Preface

Nearly a decade has passed since the publication of the first edition of this Reader, a period that has witnessed the most significant economic downturn since the Great Depression. Some of the responsibility for this recession has been laid at the feet of the economics profession, justifiably or not, and one of the byproducts of this criticism and, in some instances, selfexamination, has been a renewed interest in the history of economic ideas.

The following pages contain some of the great literature in this history. The task of putting together a Reader such as this is like confronting an endless smorgasbord of delights when on a highly restrictive diet—so many good things to sample and so little room to actually indulge. It should be obvious that reading the selections contained herein is no substitute for reading the original works in their entirety. However, we hope that the reader will find our selections sufficient to provide a useful overview of some of the major themes in the history of economic thought as they were developed in the hands of the giants in the field.

No “Reader” can pretend to be comprehensive in its coverage. The scholars chosen for inclusion, and the passages excerpted from their works, will no doubt please some greatly and disappoint others. For the latter, we apologize. In putting together this Reader, we have relied on a broad survey of course reading lists in the field, conversations with various colleagues, and our own instincts and intuition regarding topics usually covered in history of economic thought courses. We have tried both to present the central ideas of each epoch within economic thought and to avoid overlap across writers. In doing so, we have also paid attention to the fact that certain of these classic works (e.g., Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations) are readily available in inexpensive paperback editions should the reader wish to examine them further. Thus, the length of the excepts from, for example, Smith and Keynes reprinted here are perhaps rather more brief than what their stature in the history of economic ideas would suggest. We have also endeavored to provide sufficient introductory material1 for each part and each entry to provide a bit of background and plenty of suggestions for additional reading.

The second edition of this Reader has benefited from the helpful comments on the first edition made by a variety of professors who have utilized the book and by several reviewers engaged by the publisher. This edition largely replicates the coverage of the first edition, but it adds a new part on “Post-World War II Economics” that attempts to provide some insight into how the profession changed during the 1950s and 1960s and updates the suggestions for further reading to reflect important developments in various literatures. The addition of

1 We would like to acknowledge the fact that we have drawn heavily on Mark Blaug’s Great Economists Before Keynes for the biographical information contained in these introductory materials.

material on the post-World War II period poses a special challenge, given the explosion of literature during this time and the vast expansion of the tools and frameworks utilized by economists, as well as the domain of economic analysis. We have tried to be sensitive to the fact that the majority of the audience for this book consists of undergraduate students and so have selected a set of seminal works that minimize the use of mathematics.

We realize full well that there are many ways of doing history, and many ways of teaching the history of economic thought. We have tried to be sensitive to this in the preparation of this volume, and we are hopeful that all readers/students/scholars with interest in the history of economic ideas will find useful things to take from this volume.

While we anticipate that the primary market for this book will be students in history of economic thought courses, some of you may be reading this book simply because you have an interest in the history of ideas—economic or otherwise. For those who are new to the history of economic thought and wish to supplement your reading with secondary analysis, we refer you to Roger Backhouse’s The Ordinary Business of Life (The Penguin History of Economics in the UK), Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers, or the excellent textbooks in the field by Mark Blaug, Robert Ekelund and Robert Hébert, Harry Landreth and David Colander, Henry Spiegel, Alessandro Roncaglia, and Ingrid Rima—each of which to some extent embodies its own perspective on the history of the field. If you would like to “sit a course of lectures” in the field from your easy chair, you may consult Lionel Robbins’s A History of Economic Thought: The LSE Lectures. The website for Duke University’s Center for the History of Political Economy (http://hope.econ.duke.edu/) can put the reader in touch with a wealth of additional resources related to the study of the history of economics.

My wonderful co-editor, mentor, and friend, Warren J. Samuels, passed away while this book was in the revision process. He was a giant in the field of the history of economics, and as much for his dedication to the development of the field and his encouragement of the work of young scholars as for his own voluminous scholarly contributions. While his presence among us is sorely missed, this volume is testament to the insights and pleasures that accompany his passion—the study of the history of economic ideas.

S.G.M.

Acknowledgments

We are once again indebted to the excellent staff at Routledge—and particularly Rob Langham, Simon Holt, and Emily Senior—for their efforts in seeing this revision through to completion. We would also like to thank all those who gave us advice along the way, including Roger Backhouse, Bill Barber, and several anonymous reviewers, as well as Matt Powers, who provided invaluable research assistance, and Rodney Spencer and Brian Duncan for technical assistance. Finally, we would like to thank the various publishers who have graciously allowed us to reprint the works included in this volume.

The authors and publishers would like to thank the following for granting permission to reproduce material in this work.

The National Portrait Gallery, London for permission to reproduce images of Sir William Petty, John Locke, Jeremy Bentham, Henry Thornton, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, Alfred Marshall, and John Maynard Keynes.

Corbis for permission to reproduce images of Aristotle and Plato, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Thorstein B. Veblen.

Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library for permission to reproduce the image of Irving Fisher.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders for their permission to reprint material in this book. The publishers would be grateful to hear from any copyright holder who is not here acknowledged and will undertake to rectify any errors or omissions in future editions of this book.

Thank you to MIT Press for permission to reproduce Paul A. Samuelson’s articles ‘The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36:4 (November, 1954), pp. 387–389 and ‘Diagrammatic Exposition of a Pure Theory of Public Expenditure’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Nov., 1955), pp. 350–356.

Thank you to John Wiley & Sons for permission to reproduce A.W.H. Phillips’ article ‘The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957’, Economica, New Series, 25 (Nov., 1958): 283–99.

Thank you to the American Economic Association for permission to reproduce Milton Friedman’s article ‘The Role of Monetary Policy’, American Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Mar., 1968), pp. 1–17.

Thank you to the University of Chicago Press for permission to reproduce Milton Friedman’s article (The Methodology of Positive Economics in Essays in Positive Economics 1953).

This page intentionally left blank

Part I

Pre-Classical Thought

Introduction

It is a widely held, and probably substantially correct, view that the emergence and development of modern economic thought was correlative with the emergence of a commercial, eventually industrial, capitalist market economy. It is this economic system, especially as it arose in Western Europe in the eighteenth century, that economics attempts to describe, interpret, and explain, as well as to justify. This economic thought was both positive and normative, that is, it combined efforts to objectively describe and explain with those to justify and/or to prescribe (such as policy). As a positive, scientific discipline, it combined two modes of thought: (1) empirical observation, dependent upon some more or less implicit theoretical or interpretive schema, and (2) logical analysis of the relationships between variables, dependent upon some more or less conscious generalization of interpreted observations.

Prior to this time, speaking generally, there were markets and market relationships but not market economies as the latter came to be understood after roughly the eighteenth century. While modern economic theory did not exist, thinkers of various types did speculate about a set of more or less clearly identified “economic” topics, such as trade, value, money, production, and so on. These speculations are found in documents emanating from the ancient civilizations, such as Sumeria, Babylonia, Assyria, Egypt, Persia, Israel, and the Hittite empire. Some of these documents are literary or historical; others are legal; still others arose out of business and family matters; and others involved speculation about current and/or perennial events and problems. It is clear that economic activity, especially that having to do with trade, both local and between distant lands, was engaged in by households and specialized enterprises, and gave rise to various forms of economic “analysis.”

These documents seem not to have contained anything like what we now recognize as theoretical or empirical economics. But they do indicate several important concerns, centering on the general problem of the organization and control of economic activity: problems of class and of hierarchy versus equality, problems of continuity versus change of existing arrangements, problems of reconciling interpersonal conflicts of interest, problems of the nature and place of the institution of private property in the social structure, problems of the distributions of income and taxes, and so on, all interrelated. Much of the speculation related to current issues rather than to abstract generalizations, but the latter are not absent. Early economic thought had two other characteristics: One was the mythopoeic nature of description and explanation: explication through the creation of stories involving either the gods or, eventually, God, or an anthropomorphic characterization of nature as involving spirits and transcendental forces. The other was the subordination of economic thinking to theology and organized religion and, especially, the superimposition of a system of morals

upon economic (and other forms of) activity. The former remains in the form of the concept of the “invisible hand”; the latter, in the felt need for the social control of both individual economic activity and the organization of markets. The latter also gave this analysis more of a normative cast than one finds in much of modern economics.

“Modern” philosophy in the West traces back to the Greeks during the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Mythopoetry does not disappear but, one might sense, reaches its highest levels of sophistication, and, especially, existing alongside of self-conscious and self-reflective philosophical inquiry, the latter becoming increasingly independent—though not without tension and conflict. The development of philosophy is facilitated and motivated by (1) the postulation of the existence of principles of an intellectual order in the universe (in nature and in society), (2) the growing belief in the opportunity accorded by God to study the nature of things without such activity being deemed an intrusion upon the domain of God, and inter alia (3) the development of principles of observation, logic, and epistemology.

In the eighth century BC, Hesiod wrote several works, one of which, Ode to Work (or Works and Days), identified the role of hard, honest labor in production and the studied approach to husbandry and farming, the latter couched in terms of proceeding in the manner desired by deified forces of nature, including the seasons. This work was cited three centuries later by Plato and Aristotle. One of their contemporaries was Xenophon (430–355 BC), whose Oeconomicus dealt with household management (most production was undertaken by households) and with analyses of the division of labor, money, and the responsibilities of the wealthy. Xenophon’s Revenue of Athens was a brilliant analysis of the means that could be employed by the organized city-state to increase both the prosperity of the people and the revenues of their government, an analysis combined with the injunction, once the program of measures of economic development had been worked out, to consult the oracles of Dodona and Delphi if such a program was indeed going to be advantageous.

But it is with Plato (427–347 BC), notably in his Republic and The Laws, and with Aristotle (384–322 BC), in his Politics and Nichomachean Ethics, that more elaborate and more sophisticated economic analysis takes place. Both Plato and Aristotle were concerned with (1) aspects of the relation of knowledge to social action; (2) topics of political economy, such as the nature and implications of “justice” for the organization and control of the economy, including issues of private property versus communism and/or its social control; and (3) more technical topics of economics, such as self-sufficiency versus trade, the consequences of specialization and division of labor (including their relation to trade), the desirable-necessary location of the city-state, the nature and role of exchange, the roles of money and money demand, interest on loans, the question of population, prices and price levels, and the meaning and source of “value.” Their discussions of these topics reflect the social (read: class) organization of Athens, the deep philosophical positions they held on a variety of topics, the economic development of Athens and its trading partners, and how they worked out solutions to serious, perennial problems of social order. In terms of the canon of Western economic thinking, economic analysis largely disappeared for roughly a millennium-and-a-half subsequent to the death of Aristotle, not to reappear in a significant way until the scholastic writers beginning in the thirteenth century AD.

The readings that follow in this section trace the development of economic thought from the Greeks through the late eighteenth century. Along the way, the reader will be introduced to classic writings in scholasticism, mercantilism, and physiocracy, as well as to works that mark a turn in economic thinking toward a more systematic, and some would say scientific, method of analysis. While economics, throughout this period, was primarily considered to be, and analyzed from the perspective of, larger systems of social and philosophical thought,

Part I: Introduction 3

the economic system increasingly came to be recognized as a sphere that embodied its own particular set of laws, worthy of analysis in its own right. The reader will also notice an increasing recognition over this period of the interdependent nature of economic phenomena and thus the tendency of the authors to increasingly treat the economic system as an interrelated whole as opposed to engaging in piecemeal analysis of particular aspects of economic activity.

References and Further Reading

Blaug, Mark, ed. (1991) Pre-Classical Economists, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing. Hutchison, Terence (1988) Before Adam Smith: The Emergence of Political Economy, 1662–1776, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Letwin, William (1964) The Origins of Scientific Economics, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co. Lowry, S. Todd, ed. (1987) Pre-Classical Economic Thought: From the Greeks to the Scottish Enlightenment, Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Rothbard, Murray (1995) Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Spengler, Joseph J. (1980) Origins of Economic Thought and Justice, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

ARISTOTLE (384–322 BC)

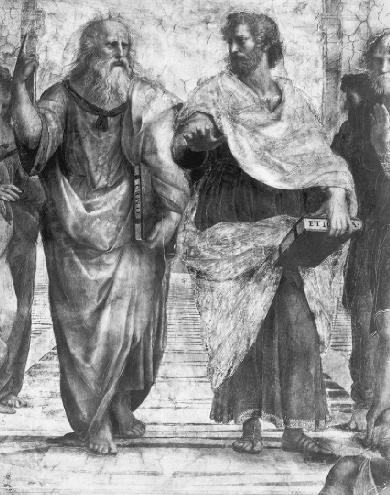

Aristotle with Plato, by courtesy of Corbis, www.corbis.com.

Aristotle was born in Stagira and spent some twenty years studying under the tutelage of Plato in Athens. After a number of years of travel and serving as tutor to the young man who would later become Alexander the Great, Aristotle returned to Athens and established his own school, the Lyceum, in 335 BC.

The works of Aristotle span virtually the entire breadth of human knowledge— logic, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, the natural sciences, rhetoric, politics, and aesthetics. While only a small fraction of his writings deal with economics, he did see matters economic as an important aspect of the social fabric and thus as necessary elements of a larger social–philosophical system of thought. Aristotle’s writings had a profound influence on Aquinas and, through Aquinas, on subsequent scholastic thinking. Indeed, Aristotle’s influence continues to be present in modern economic theory.

In the excerpts from Aristotle’s Politics and Ethics provided below, we are introduced to his theories of the natural division of labor within society, household management (œconomicus) and wealth acquisition (chrematistics), private property versus communal property, and of the exchange process. The reader may wish to take particular note of the “reciprocal needs” basis of Aristotle’s division of labor, his view that wealth acquisition is “unnatural” because it knows no natural limits, his strong defense of private property (as against his teacher, Plato), and his theory of reciprocity in exchange.

References and Further Reading

Finley, M.I. (1970) “Aristotle and Economic Analysis,” Past and Present 47 (May): 3–25. —— (1973) The Ancient Economy, Berkeley: University of California Press. —— (1987) “Aristotle,” in John Eatwell, Murray Milgate, and Peter Newman (eds.), The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Vol. 1, London: Macmillan, 112–13.

Gordon, Barry (1975) Economic Analysis Before Adam Smith: Hesiod to Lessius, New York: Barnes and Noble.

Laistner, M.L.W. (1923) Greek Economics: Introduction and Translation, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Langholm, Odd (1979) Price and Value Theory in the Aristotelian Tradition, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

—— (1983) Wealth and Money in the Aristotelian Tradition, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

—— (1984) The Aristotelian Analysis of Usury, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

Lowry, S. Todd (1969) “Aristotle’s Mathematical Analysis of Exchange,” History of Political Economy 1 (Spring): 44–66.

—— (1979) “Recent Literature on Ancient Greek Economic Thought,” Journal of Economic Literature 17: 65–86.

—— (1987) The Archaeology of Economic Ideas: The Greek Classical Tradition, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Soudek, Josef (1952) “Aristotle’s Theory of Exchange: An Enquiry into the Origin of Economic Analysis,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96: 45–75.

Spengler, Joseph J. (1955) “Aristotle on Economic Imputation and Related Matters,” Southern Economic Journal 21 (April): 371–89.

—— (1980) Origins of Economic Thought and Justice, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. Worland, Stephen T. (1984) “Aristotle and the Neoclassical Tradition: The Shifting Ground of Complementarity,” History of Political Economy 16: 107–34.

Politics*

Book I

Part I

Every state is a community of some kind, and every community is established with a view to some good; for mankind always act in order to obtain that which they think good. But, if all communities aim at some good, the state or political community, which is the highest of all, and which embraces all the rest, aims at good in a greater degree than any other, and at the highest good.

Some people think that the qualifications of a statesman, king, householder, and master are the same, and that they differ, not in kind, but only in the number of their subjects. For example, the ruler over a few is called a master; over more, the manager of a household; over a still larger number, a statesman or king, as if there were no difference between a great household and a small state. The distinction which is made between the king and the statesman is as follows: When the government is personal, the ruler is a king; when, according to the rules of the political science, the citizens rule and are ruled in turn, then he is called a statesman.

But all this is a mistake; for governments differ in kind, as will be evident to any one who considers the matter according to the method which has hitherto guided us. As in other departments of science, so in politics, the compound should always be resolved into the simple elements or least parts of the whole. We must therefore look at the elements of which the state is composed, in order that we may see in what the different kinds of rule differ from one another, and whether any scientific result can be attained about each one of them.

Part II

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin, whether a state or anything else, will obtain the clearest view of them. In the first place there must be a union of those who cannot exist without each other; namely, of male and female, that the race may continue (and this is a union which is formed, not of deliberate purpose, but because, in common with other animals and with plants, mankind have a natural desire to leave behind them an image of themselves), and of natural ruler and subject, that both may be preserved. For that which can foresee by the exercise of mind is by nature intended to be lord and master, and that which can with its body give effect to such foresight is a subject, and by nature a slave; hence master and slave have the same interest. Now nature has distinguished between the

* Translated by Benjamin Jowett.

female and the slave. For she is not niggardly, like the smith who fashions the Delphian knife for many uses; she makes each thing for a single use, and every instrument is best made when intended for one and not for many uses. But among barbarians no distinction is made between women and slaves, because there is no natural ruler among them: they are a community of slaves, male and female. Wherefore the poets say,

“It is meet that Hellenes should rule over barbarians;”

as if they thought that the barbarian and the slave were by nature one. Out of these two relationships between man and woman, master and slave, the first thing to arise is the family, and Hesiod is right when he says,

“First house and wife and an ox for the plow”

for the ox is the poor man’s slave. The family is the association established by nature for the supply of men’s everyday wants, and the members of it are called by Charondas ‘companions of the cupboard,’ and by Epimenides the Cretan, ‘companions of the manger.’ But when several families are united, and the association aims at something more than the supply of daily needs, the first society to be formed is the village. And the most natural form of the village appears to be that of a colony from the family, composed of the children and grandchildren, who are said to be suckled ‘with the same milk.’ And this is the reason why Hellenic states were originally governed by kings; because the Hellenes were under royal rule before they came together, as the barbarians still are. Every family is ruled by the eldest, and therefore in the colonies of the family the kingly form of government prevailed because they were of the same blood. As Homer says:

“Each one gives law to his children and to his wives.”

For they lived dispersedly, as was the manner in ancient times. Wherefore men say that the Gods have a king, because they themselves either are or were in ancient times under the rule of a king. For they imagine, not only the forms of the Gods, but their ways of life to be like their own.

When several villages are united in a single complete community, large enough to be nearly or quite self-sufficing, the state comes into existence, originating in the bare needs of life, and continuing in existence for the sake of a good life. And therefore, if the earlier forms of society are natural, so is the state, for it is the end of them, and the nature of a thing is its end. For what each thing is when fully developed, we call its nature, whether we are speaking of a man, a horse, or a family. Besides, the final cause and end of a thing is the best, and to be self-sufficing is the end and the best. . . .

Further, the state is by nature clearly prior to the family and to the individual, since the whole is of necessity prior to the part; for example, if the whole body be destroyed, there will be no foot or hand, except in an equivocal sense, as we might speak of a stone hand; for when destroyed the hand will be no better than that. But things are defined by their working and power; and we ought not to say that they are the same when they no longer have their proper quality, but only that they have the same name. The proof that the state is a creation

of nature and prior to the individual is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole. But he who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state. A social instinct is implanted in all men by nature, and yet he who first founded the state was the greatest of benefactors. For man, when perfected, is the best of animals, but, when separated from law and justice, he is the worst of all; since armed injustice is the more dangerous, and he is equipped at birth with arms, meant to be used by intelligence and virtue, which he may use for the worst ends. Wherefore, if he have not virtue, he is the most unholy and the most savage of animals, and the most full of lust and gluttony. But justice is the bond of men in states, for the administration of justice, which is the determination of what is just, is the principle of order in political society.

Part III

Seeing then that the state is made up of households, before speaking of the state we must speak of the management of the household. The parts of household management correspond to the persons who compose the household, and a complete household consists of slaves and freemen. Now we should begin by examining everything in its fewest possible elements; and the first and fewest possible parts of a family are master and slave, husband and wife, father and children. We have therefore to consider what each of these three relations is and ought to be: I mean the relation of master and servant, the marriage relation (the conjunction of man and wife has no name of its own), and thirdly, the procreative relation (this also has no proper name). And there is another element of a household, the so-called art of getting wealth, which, according to some, is identical with household management, according to others, a principal part of it; the nature of this art will also have to be considered by us.

Let us first speak of master and slave, looking to the needs of practical life and also seeking to attain some better theory of their relation than exists at present. For some are of opinion that the rule of a master is a science, and that the management of a household, and the mastership of slaves, and the political and royal rule, as I was saying at the outset, are all the same. Others affirm that the rule of a master over slaves is contrary to nature, and that the distinction between slave and freeman exists by law only, and not by nature; and being an interference with nature is therefore unjust.

Part IV

Property is a part of the household, and the art of acquiring property is a part of the art of managing the household; for no man can live well, or indeed live at all, unless he be provided with necessaries. And as in the arts which have a definite sphere the workers must have their own proper instruments for the accomplishment of their work, so it is in the management of a household. Now instruments are of various sorts; some are living, others lifeless; in the rudder, the pilot of a ship has a lifeless, in the look-out man, a living instrument; for in the arts the servant is a kind of instrument. Thus, too, a possession is an instrument for maintaining life. And so, in the arrangement of the family, a slave is a living possession, and property a number of such instruments; and the servant is himself an instrument which takes precedence of all other instruments. For if every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daedalus, or the tripods of Hephaestus, which, says the poet,

“of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods;”

if, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves. Here, however, another distinction must be drawn; the instruments commonly so called are instruments of production, whilst a possession is an instrument of action. The shuttle, for example, is not only of use; but something else is made by it, whereas of a garment or of a bed there is only the use. Further, as production and action are different in kind, and both require instruments, the instruments which they employ must likewise differ in kind. But life is action and not production, and therefore the slave is the minister of action. Again, a possession is spoken of as a part is spoken of; for the part is not only a part of something else, but wholly belongs to it; and this is also true of a possession. The master is only the master of the slave; he does not belong to him, whereas the slave is not only the slave of his master, but wholly belongs to him. Hence we see what is the nature and office of a slave; he who is by nature not his own but another’s man, is by nature a slave; and he may be said to be another’s man who, being a human being, is also a possession. And a possession may be defined as an instrument of action, separable from the possessor.

Part VIII

Let us now inquire into property generally, and into the art of getting wealth, in accordance with our usual method, for a slave has been shown to be a part of property. The first question is whether the art of getting wealth is the same with the art of managing a household or a part of it, or instrumental to it; and if the last, whether in the way that the art of making shuttles is instrumental to the art of weaving, or in the way that the casting of bronze is instrumental to the art of the statuary, for they are not instrumental in the same way, but the one provides tools and the other material; and by material I mean the substratum out of which any work is made; thus wool is the material of the weaver, bronze of the statuary. Now it is easy to see that the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides. For the art which uses household stores can be no other than the art of household management. There is, however, a doubt whether the art of getting wealth is a part of household management or a distinct art. If the getter of wealth has to consider whence wealth and property can be procured, but there are many sorts of property and riches, then are husbandry, and the care and provision of food in general, parts of the wealth-getting art or distinct arts? Again, there are many sorts of food, and therefore there are many kinds of lives both of animals and men; they must all have food, and the differences in their food have made differences in their ways of life. For of beasts, some are gregarious, others are solitary; they live in the way which is best adapted to sustain them, accordingly as they are carnivorous or herbivorous or omnivorous: and their habits are determined for them by nature in such a manner that they may obtain with greater facility the food of their choice. But, as different species have different tastes, the same things are not naturally pleasant to all of them; and therefore the lives of carnivorous or herbivorous animals further differ among themselves. In the lives of men too there is a great difference. The laziest are shepherds, who lead an idle life, and get their subsistence without trouble from tame animals; their flocks having to wander from place to place in search of pasture, they are compelled to follow them, cultivating a sort of living farm. Others support themselves by hunting, which is of different kinds. Some, for example, are brigands, others, who dwell near lakes or marshes or rivers or a sea in which there are fish, are fishermen, and others live by the pursuit of birds or wild beasts. The greater number obtain a living from the cultivated fruits of the soil. Such are the modes of subsistence which prevail among those

whose industry springs up of itself, and whose food is not acquired by exchange and retail trade – there is the shepherd, the husbandman, the brigand, the fisherman, the hunter. Some gain a comfortable maintenance out of two employments, eking out the deficiencies of one of them by another: thus the life of a shepherd may be combined with that of a brigand, the life of a farmer with that of a hunter. Other modes of life are similarly combined in any way which the needs of men may require. Property, in the sense of a bare livelihood, seems to be given by nature herself to all, both when they are first born, and when they are grown up. For some animals bring forth, together with their offspring, so much food as will last until they are able to supply themselves; of this the vermiparous or oviparous animals are an instance; and the viviparous animals have up to a certain time a supply of food for their young in themselves, which is called milk. In like manner we may infer that, after the birth of animals, plants exist for their sake, and that the other animals exist for the sake of man, the tame for use and food, the wild, if not all at least the greater part of them, for food, and for the provision of clothing and various instruments. Now if nature makes nothing incomplete, and nothing in vain, the inference must be that she has made all animals for the sake of man. And so, in one point of view, the art of war is a natural art of acquisition, for the art of acquisition includes hunting, an art which we ought to practice against wild beasts, and against men who, though intended by nature to be governed, will not submit; for war of such a kind is naturally just.

Of the art of acquisition then there is one kind which by nature is a part of the management of a household, in so far as the art of household management must either find ready to hand, or itself provide, such things necessary to life, and useful for the community of the family or state, as can be stored. They are the elements of true riches; for the amount of property which is needed for a good life is not unlimited, although Solon in one of his poems says that

“No bound to riches has been fixed for man.”

But there is a boundary fixed, just as there is in the other arts; for the instruments of any art are never unlimited, either in number or size, and riches may be defined as a number of instruments to be used in a household or in a state. And so we see that there is a natural art of acquisition which is practiced by managers of households and by statesmen, and what is the reason of this.

Part IX

There is another variety of the art of acquisition which is commonly and rightly called an art of wealth-getting, and has in fact suggested the notion that riches and property have no limit. Being nearly connected with the preceding, it is often identified with it. But though they are not very different, neither are they the same. The kind already described is given by nature, the other is gained by experience and art.

Let us begin our discussion of the question with the following considerations: Of everything which we possess there are two uses: both belong to the thing as such, but not in the same manner, for one is the proper, and the other the improper or secondary use of it. For example, a shoe is used for wear, and is used for exchange; both are uses of the shoe. He who gives a shoe in exchange for money or food to him who wants one, does indeed use the shoe as a shoe, but this is not its proper or primary purpose, for a shoe is not made to be an object of barter. The same may be said of all possessions, for the art of exchange extends to all of them, and it arises at first from what is natural, from the circumstance that

some have too little, others too much. Hence we may infer that retail trade is not a natural part of the art of getting wealth; had it been so, men would have ceased to exchange when they had enough. In the first community, indeed, which is the family, this art is obviously of no use, but it begins to be useful when the society increases. For the members of the family originally had all things in common; later, when the family divided into parts, the parts shared in many things, and different parts in different things, which they had to give in exchange for what they wanted, a kind of barter which is still practiced among barbarous nations who exchange with one another the necessaries of life and nothing more; giving and receiving wine, for example, in exchange for coin, and the like. This sort of barter is not part of the wealth-getting art and is not contrary to nature, but is needed for the satisfaction of men’s natural wants. The other or more complex form of exchange grew, as might have been inferred, out of the simpler. When the inhabitants of one country became more dependent on those of another, and they imported what they needed, and exported what they had too much of, money necessarily came into use. For the various necessaries of life are not easily carried about, and hence men agreed to employ in their dealings with each other something which was intrinsically useful and easily applicable to the purposes of life, for example, iron, silver, and the like. Of this the value was at first measured simply by size and weight, but in process of time they put a stamp upon it, to save the trouble of weighing and to mark the value.

When the use of coin had once been discovered, out of the barter of necessary articles arose the other art of wealth getting, namely, retail trade; which was at first probably a simple matter, but became more complicated as soon as men learned by experience whence and by what exchanges the greatest profit might be made. Originating in the use of coin, the art of getting wealth is generally thought to be chiefly concerned with it, and to be the art which produces riches and wealth; having to consider how they may be accumulated. Indeed, riches is assumed by many to be only a quantity of coin, because the arts of getting wealth and retail trade are concerned with coin. Others maintain that coined money is a mere sham, a thing not natural, but conventional only, because, if the users substitute another commodity for it, it is worthless, and because it is not useful as a means to any of the necessities of life, and, indeed, he who is rich in coin may often be in want of necessary food. But how can that be wealth of which a man may have a great abundance and yet perish with hunger, like Midas in the fable, whose insatiable prayer turned everything that was set before him into gold?

Hence men seek after a better notion of riches and of the art of getting wealth than the mere acquisition of coin, and they are right. For natural riches and the natural art of wealth-getting are a different thing; in their true form they are part of the management of a household; whereas retail trade is the art of producing wealth, not in every way, but by exchange. And it is thought to be concerned with coin; for coin is the unit of exchange and the measure or limit of it. And there is no bound to the riches which spring from this art of wealth getting. As in the art of medicine there is no limit to the pursuit of health, and as in the other arts there is no limit to the pursuit of their several ends, for they aim at accomplishing their ends to the uttermost (but of the means there is a limit, for the end is always the limit), so, too, in this art of wealth-getting there is no limit of the end, which is riches of the spurious kind, and the acquisition of wealth. But the art of wealth-getting which consists in household management, on the other hand, has a limit; the unlimited acquisition of wealth is not its business. And, therefore, in one point of view, all riches must have a limit; nevertheless, as a matter of fact, we find the opposite to be the case; for all getters of wealth increase their hoard of coin without limit. The source of the confusion is the near connection between the two kinds of wealth-getting; in either, the instrument is the same, although the use is different,

and so they pass into one another; for each is a use of the same property, but with a difference: accumulation is the end in the one case, but there is a further end in the other. Hence some persons are led to believe that getting wealth is the object of household management, and the whole idea of their lives is that they ought either to increase their money without limit, or at any rate not to lose it. The origin of this disposition in men is that they are intent upon living only, and not upon living well; and, as their desires are unlimited they also desire that the means of gratifying them should be without limit. Those who do aim at a good life seek the means of obtaining bodily pleasures; and, since the enjoyment of these appears to depend on property, they are absorbed in getting wealth: and so there arises the second species of wealth-getting. For, as their enjoyment is in excess, they seek an art which produces the excess of enjoyment; and, if they are not able to supply their pleasures by the art of getting wealth, they try other arts, using in turn every faculty in a manner contrary to nature. The quality of courage, for example, is not intended to make wealth, but to inspire confidence; neither is this the aim of the general’s or of the physician’s art; but the one aims at victory and the other at health. Nevertheless, some men turn every quality or art into a means of getting wealth; this they conceive to be the end, and to the promotion of the end they think all things must contribute.

Thus, then, we have considered the art of wealth-getting which is unnecessary, and why men want it; and also the necessary art of wealth-getting, which we have seen to be different from the other, and to be a natural part of the art of managing a household, concerned with the provision of food, not, however, like the former kind, unlimited, but having a limit.

Part X

And we have found the answer to our original question, Whether the art of getting wealth is the business of the manager of a household and of the statesman or not their business? viz., that wealth is presupposed by them. For as political science does not make men, but takes them from nature and uses them, so too nature provides them with earth or sea or the like as a source of food. At this stage begins the duty of the manager of a household, who has to order the things which nature supplies; he may be compared to the weaver who has not to make but to use wool, and to know, too, what sort of wool is good and serviceable or bad and unserviceable. Were this otherwise, it would be difficult to see why the art of getting wealth is a part of the management of a household and the art of medicine not; for surely the members of a household must have health just as they must have life or any other necessary. The answer is that as from one point of view the master of the house and the ruler of the state have to consider about health, from another point of view not they but the physician; so in one way the art of household management, in another way the subordinate art, has to consider about wealth. But, strictly speaking, as I have already said, the means of life must be provided beforehand by nature; for the business of nature is to furnish food to that which is born, and the food of the offspring is always what remains over of that from which it is produced. Wherefore the art of getting wealth out of fruits and animals is always natural. There are two sorts of wealth-getting, as I have said; one is a part of household management, the other is retail trade: the former necessary and honorable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another. The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.

Part XI

Enough has been said about the theory of wealth-getting; we will now proceed to the practical part. The discussion of such matters is not unworthy of philosophy, but to be engaged in them practically is illiberal and irksome. The useful parts of wealth-getting are, first, the knowledge of livestock – which are most profitable, and where, and how – as, for example, what sort of horses or sheep or oxen or any other animals are most likely to give a return. A man ought to know which of these pay better than others, and which pay best in particular places, for some do better in one place and some in another. Secondly, husbandry, which may be either tillage or planting, and the keeping of bees and of fish, or fowl, or of any animals which may be useful to man. These are the divisions of the true or proper art of wealth-getting and come first. Of the other, which consists in exchange, the first and most important division is commerce (of which there are three kinds – the provision of a ship, the conveyance of goods, exposure for sale – these again differing as they are safer or more profitable), the second is usury, the third, service for hire – of this, one kind is employed in the mechanical arts, the other in unskilled and bodily labor. There is still a third sort of wealth getting intermediate between this and the first or natural mode which is partly natural, but is also concerned with exchange, viz., the industries that make their profit from the earth, and from things growing from the earth which, although they bear no fruit, are nevertheless profitable; for example, the cutting of timber and all mining. The art of mining, by which minerals are obtained, itself has many branches, for there are various kinds of things dug out of the earth. Of the several divisions of wealth-getting I now speak generally; a minute consideration of them might be useful in practice, but it would be tiresome to dwell upon them at greater length now.

Those occupations are most truly arts in which there is the least element of chance; they are the meanest in which the body is most deteriorated, the most servile in which there is the greatest use of the body, and the most illiberal in which there is the least need of excellence.

Works have been written upon these subjects by various persons; for example, by Chares the Parian, and Apollodorus the Lemnian, who have treated of Tillage and Planting, while others have treated of other branches; any one who cares for such matters may refer to their writings. It would be well also to collect the scattered stories of the ways in which individuals have succeeded in amassing a fortune; for all this is useful to persons who value the art of getting wealth. There is the anecdote of Thales the Milesian and his financial device, which involves a principle of universal application, but is attributed to him on account of his reputation for wisdom. He was reproached for his poverty, which was supposed to show that philosophy was of no use. According to the story, he knew by his skill in the stars while it was yet winter that there would be a great harvest of olives in the coming year; so, having a little money, he gave deposits for the use of all the olive-presses in Chios and Miletus, which he hired at a low price because no one bid against him. When the harvest-time came, and many were wanted all at once and of a sudden, he let them out at any rate which he pleased, and made a quantity of money. Thus he showed the world that philosophers can easily be rich if they like, but that their ambition is of another sort. He is supposed to have given a striking proof of his wisdom, but, as I was saying, his device for getting wealth is of universal application, and is nothing but the creation of a monopoly. It is an art often practiced by cities when they are want of money; they make a monopoly of provisions.

There was a man of Sicily, who, having money deposited with him, bought up all the iron from the iron mines; afterwards, when the merchants from their various markets came to buy,

he was the only seller, and without much increasing the price he gained 200 per cent. Which when Dionysius heard, he told him that he might take away his money, but that he must not remain at Syracuse, for he thought that the man had discovered a way of making money which was injurious to his own interests. He made the same discovery as Thales; they both contrived to create a monopoly for themselves. And statesmen as well ought to know these things; for a state is often as much in want of money and of such devices for obtaining it as a household, or even more so; hence some public men devote themselves entirely to finance.

Book II

Part V

Next let us consider what should be our arrangements about property: should the citizens of the perfect state have their possessions in common or not? This question may be discussed separately from the enactments about women and children. Even supposing that the women and children belong to individuals, according to the custom which is at present universal, may there not be an advantage in having and using possessions in common? Three cases are possible: (1) the soil may be appropriated, but the produce may be thrown for consumption into the common stock; and this is the practice of some nations. Or (2), the soil may be common, and may be cultivated in common, but the produce divided among individuals for their private use; this is a form of common property which is said to exist among certain barbarians. Or (3), the soil and the produce may be alike common.

When the husbandmen are not the owners, the case will be different and easier to deal with; but when they till the ground for themselves the question of ownership will give a world of trouble. If they do not share equally enjoyments and toils, those who labor much and get little will necessarily complain of those who labor little and receive or consume much. But indeed there is always a difficulty in men living together and having all human relations in common, but especially in their having common property. The partnerships of fellow-travelers are an example to the point; for they generally fall out over everyday matters and quarrel about any trifle which turns up. So with servants: we are most able to take offense at those with whom we most frequently come into contact in daily life.

These are only some of the disadvantages which attend the community of property; the present arrangement, if improved as it might be by good customs and laws, would be far better, and would have the advantages of both systems. Property should be in a certain sense common, but, as a general rule, private; for, when everyone has a distinct interest, men will not complain of one another, and they will make more progress, because every one will be attending to his own business. And yet by reason of goodness, and in respect of use, ‘Friends,’ as the proverb says, ‘will have all things common.’ Even now there are traces of such a principle, showing that it is not impracticable, but, in well-ordered states, exists already to a certain extent and may be carried further. For, although every man has his own property, some things he will place at the disposal of his friends, while of others he shares the use with them. The Lacedaemonians, for example, use one another’s slaves, and horses, and dogs, as if they were their own; and when they lack provisions on a journey, they appropriate what they find in the fields throughout the country. It is clearly better that property should be private, but the use of it common; and the special business of the legislator is to create in men this benevolent disposition. Again, how immeasurably greater is the pleasure, when a man feels a thing to be his own; for surely the love of self is a feeling implanted by nature and not given in vain, although selfishness is rightly censured; this, however, is not the mere

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

authorities were seated round two sides of the room, and a number of the lower class squatted on the floor on the third side, while on the fourth side three chairs were placed for us. As soon as we were seated, the Governor, a tall elderly man, receiving us most cordially, addressed us with a formal speech, after the custom of the Malagasy officials to anyone who came from the capital; and as this may serve as an example of the way in which we were received in all the principal places, I will give it pretty fully; it was in the following form: —“Since you, gentlemen, have come from the capital, we ask of you, How is Queen Rànavàlona, sovereign of the land? How is Rainibaiàrivòny, Prime Minister, protector of the kingdom? How is our father, Rainingòry (the oldest officer in the army, nearly a hundred years old)? How is Rainimàharàvo, Chief Secretary of State, chief of the officers of the palace? How is Rabé (son of the preceding)? How is the kingdom of Ambòhimànga and Antanànarìvo (the ancient and modern capitals)? How are ‘the-under-the-heaven’ (the people, the subjects)? How are you, our friends? And how is your fatigue after your journey?” etc. To these inquiries I, as interpreter to the expedition, gravely replied seriatim, saying that her Majesty was well, that the Prime Minister was well, etc., etc., and then inquired how the Governor and his officers, and the people of the town and neighbourhood were. We then had more general and less formal conversation, in which I explained the objects of our visit to Antsihànaka, and our proposed route round the district.

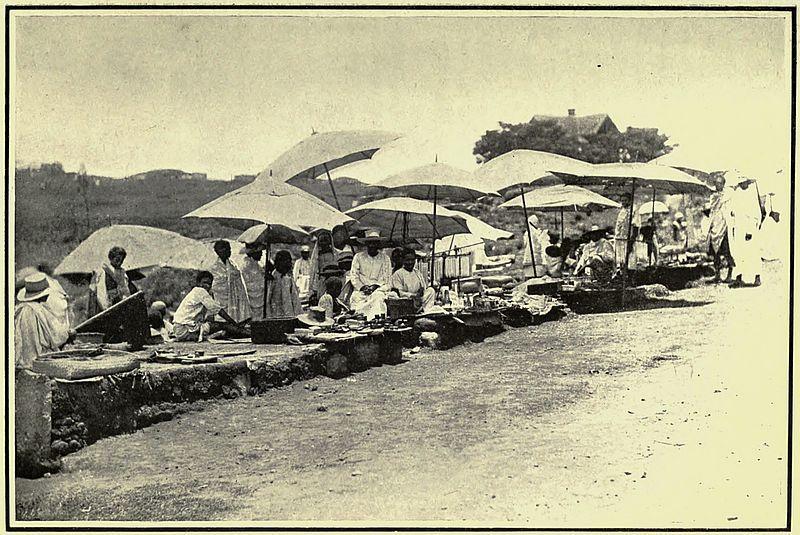

A W������ M�����

The umbrellas are to protect the vendors and goods from the sun. Beef, soap, candles, cooked rice, manioc, etc., are exposed for sale

The Governor then courteously led us by the hand back to the chapel, where he joined us in our dinner; and as soon as that was finished asked us to come outside. Here we found a quantity of provisions brought for us and our bearers; baskets of rice, geese, fowls, yams, and a large fat pig (a most unwilling offering he was, and loudly protested against the whole business). In a formal speech, as soon as silence could be obtained, the Governor offered these things to us, saying that the provisions presented were not theirs, but the Queen’s, the Prime Minister’s, etc., etc., while they only took charge of it all (a polite and loyal fiction, by the way, meaning nothing). We found a comfortable (if somewhat airy) bedroom in the spacious chapel, which formed a pleasant contrast to the confinement of our little tent of eleven feet square.

MARKET DAY

The next day, Thursday, was market day, and a number of people from the country were collected together buying and selling on an open piece of rising ground to the south of the town. The morning we devoted to inspecting the place, ascertaining the number of houses, and taking bearings, observations and photographs from a point halfa-mile to the east of the market. Our proceedings caused intense interest, as the camera, theodolite, etc., were carried past; business came to a standstill for some time, and a glance at the crowd through the field-glass showed rows of dark faces all turned in our direction, intently watching our mysterious proceedings. We afterwards walked through the market, hoping to find some articles of food or manufacture new to us; but there was not much that differed from what may be seen every day in Imèrina. In fruit I fancied I had found something new—viz. what appeared like a kind of small banana with black skin; but more minute inspection showed that the supposed fruits were small fish from the lake, smoke-dried, strung on a strong reed. Some large wooden spoons with tin ornaments on the handles reminded me of those made by the Bétsiléo. Bananas, very large and fine, seemed the most plentiful fruit; sugar-cane grows to a great size, ten to twelve feet high; and from what we saw all round Antsihànaka it appeared a most fertile district, with rich alluvial soil; were the whole marsh drained and brought under cultivation, as the marshy plain to the west and northwest of the capital has been, it would support a population many times greater than that which inhabits Imèrina. All round Ambàtondrazàka many hundred acres of the level are occupied by rice-fields, and it is the same in the neighbourhood of all the villages bordering the plain; although a large proportion of the area is still covered with marsh, reeds, rushes and papyrus. From the rising ground we could count numerous herds of fine cattle, generally from seventy to eighty in each herd, and wherever we went we found cattle in great abundance feeding on the rich pasture. Large numbers of these cattle belonged to rich people in Imèrina. One noble was said to have nearly ten thousand; others had five thousand; many people had a thousand, and the majority of the Sihànaka had at least a hundred each.

After our usual employments of school examination, conversation with the pastor and others, and renewed presents of food, on Friday morning we set off on our circuit round the plain to visit as many of the congregations, and see as much of the country and the position of the Sihànaka villages, as was possible in six days, as our time was limited to that period. Proceeding first westward, and skirting the edge of the level ground, we passed for some distance through swamp, with dense thickets of hèrana and zozòro, the first being, as already seen in Imèrina, a strong sedge extensively used for roofing, and the other, a species of papyrus, employed for a variety of purposes. This latter grows here to a great size, some ten or twelve feet high, with a triangular and exceedingly tough stem, about two and a half inches each way, nearly double the size it attains in the cooler Imèrina province.

We had to cross numerous little streams by rickety bridges of plank. From the level of the rice-fields the plain stretched northward like an immense green lake; the rotundity of the earth was as clearly seen from the perfect level as it is from the surface of the sea, for the distant low hills appeared like detached islands with nothing to connect their bases. Our course lay west by north-west, cutting diagonally across several of those promontories formed by the parallel lines of hills which run down each side of the Ankay valley. Every village of the Sihànaka has near its entrance a group of two or three tall straight trunks of trees fixed in the ground, varying from thirty to fifty feet in height; the top of these has the appearance of an enormous pair of horns, for the fork of a tree is fixed to the pole, and each branch is sharpened to a fine point. Besides these, there are generally half-a-dozen lower poles, on which are fixed a number of the skulls and horns of bullocks killed at the funeral of the people of whom these poles are the memorial. One thing struck us as curious: several of the higher poles had small tin trunks, generally painted oak colour, impaled on one point of the fork; and in several instances baskets and mats were also placed on a railing of wood close to the poles supporting the bullock horns. These various articles were the property of the deceased, and put near his grave with the hope of their being of some benefit to his spirit; or perhaps from the idea, common to most of the Malagasy tribes, of there being pollution

attached to anything connected with the dead. In several cases, on the very highest point of the lofty poles, there was a small tin fixed, having a strong resemblance to those we import containing jam or preserved provisions.[17] As among many Eastern peoples, so in Madagascar, the horn is a symbol of power and protection; the native army was termed tàndroky ny fanjakàna—“horns of the kingdom.”

Some of the cattle we saw were magnificent animals, and it is not strange that the bull was used frequently in public speeches, as an emblem of strength, as it is the largest of all the animals known to the Malagasy. It frequently occurs in this sense in the formulæ and the songs connected with the circumcision ceremonial; for the observance of this native custom was a time of very great importance in the old native regime. Bullfighting was a favourite amusement with the Malagasy sovereigns; and in digging the foundations for a new gateway to the palace yard at Antanànarìvo, the remains of a bull were discovered, wrapped up in a red silk làmba, the same style of burial as that employed for rich people. This was the honour paid to a famous fighting bull belonging to Queen Rànavàlona I. It seems pretty certain that anciently the killing of an ox was regarded as a semi-religious or sacrificial observance, and only the chief of a tribe was allowed to do this, as priest of his people. Robert Drury, an English lad who, with others, was wrecked on the south-west coast of Madagascar in 1702, and remained in the country as a slave for fifteen years, gives many particulars about this custom of the southern Sàkalàva people.

An old Malagasy saying thus describes the various uses of the different portions of an ox when killed: “The ox is the chief of the animals kept by the people, and they are very beautiful in this country. Our forefathers here knew well how it should be used, and they said thus, when they invoked a blessing (at the circumcision): The ox’s horns go to the spoon-maker; its molar teeth to the mat-maker (for smoothing out the zozòro peel); its ears are for making medicine for nettle-rash; its hump for making ointment; its rump to the sovereign; its feet to the oil-maker; its spleen to the old man; its liver to the old woman; its lungs to the son-

in-law; its intestines to those who brought the ropes; its neck to him who brought the axe; its haunch to the crier; its tail to the weaver; its suet to the soap-maker; its skin to the drummer; its head to the speech-maker; its eyes to be made into beads (used in the divination), and its hoofs to the gun-maker.”

Our next morning’s ride brought us to Ambòhidèhilàhy, a large village of a hundred and twenty or a hundred and thirty houses, occupying the northern end of one of the promontories.

For the first time since we had left Ambòhimànga we had a meal in an ordinary house, and could notice the arrangement of a Sihànaka dwelling. I immediately observed that instead of there being one post at each end and at the centre of the house to support the ridge, as in the Imèrina houses, this had three at each gable, just as the Bétsimisàraka have; another confirmation, by the way, of my belief, that the Sihànaka are connected with the coast tribes, and have come up from the sea and settled on the margin of the fertile plain. Instead of the one door and window on the west side, as in the Hova houses, the Sihànaka make two doors on that side, with high thresholds, dividing it into three equal parts, and a low door on the eastern side, coming where the fixed bedstead is placed in Imèrina. Here the bedstead was at the south-east instead of the north-east corner; and the hearth, with its framework above for supporting property of various kinds, at the south-east instead of the mid-west side of the house.

After dinner we set off over level ground for Manàkambahìny, a village nearly south from us, which we could see on a low hill forming the extremity of the high ridge bounding the Mangòro valley to the west. We found that the small rivers between the parallel ranges of hills spread out into many shallow streams over a wide surface, forming a swamp with luxuriant rushes and vegetation The wild birds seemed plentiful here. In several places was a kind of snare for taking them on the wing, consisting of several stout bamboos fixed in the ground a few feet apart, with cords stretched between them, and loops of string suspended from these cords. We were only able to stay a short time at the village, and then pushed on, crossing the level ground at the southern extremity of the Antsihànaka plain and

coming at sunset to Ambòdinònoka, a good-sized village on its western edge. Here we had reached our farthest south in our journey round the province.

SIHÀNAKA MATS

We have just seen the interior of a Sihànaka house, and we ought to have noticed the fine and strong mats with which they are furnished. From the immense extent of marsh, the material for making these is very abundant, and all women can make them; so no Sihànaka buys a mat, for they think that a disgrace. Of the zozòro outer peel, or skin, the very long mats called the Queen’s are made, which are from eighteen feet to twenty-four feet long. The houses of many people here are clean and neat from the abundance of such mats. The largest kind of zozòro, called tèry, is as strong as wood, and the firm triangular stems are used for the walls of the houses.

We were off early on Saturday morning, for, as we wished to get to the second town in size, Ampàrafàravòla, for Sunday, we had a long day’s journey northward of nine or ten hours before us. We were now skirting the western edge of the great level, now and then crossing patches of swamp, and then following the windings of a small river, which we had at last to cross by canoes. The whole country appeared to abound with wild birds of different kinds—herons, black and white storks, wild geese, wild ducks, partridges and many others. The fen country of the eastern midland counties of England, before the great drainage works were carried out and the waters led off to the sea, must have been very much like this Antsihànaka plain, which is certainly a paradise for sportsmen. There are said to be no fewer than thirty-four species of aquatic birds found on the Alaotra lake and in the surrounding marshy country In the little museum at the L.M.S. College at Antanànarìvo we have, among other Malagasy birds’ eggs, a number from Antsihànaka, chiefly of water-fowl; most of these are white, showing probably that they are well protected and so have no need of imitative colouring.

WATER-BIRDS

Of these numerous ducks and geese, perhaps the whistling teal is the most common, not only in this province, but also in other marshy regions. In the western part of Imèrina the Tsirìry, as it is called, may be seen in flocks of five