A Short History of the French Revolution

EIGHTH EDITION

Jeremy D. Popkin

Designed cover image: The National Convention monument by François-Léon Siccard (1921), The Panthéon, Paris. Lana Rastro / Alamy Stoke Photo 2K06JBP.

Eighth edition published 2024 by Routledge 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158 and by Routledge 4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

RoutledgeisanimprintoftheTaylor&FrancisGroup,aninforma business

© 2024 Jeremy D. Popkin

The right of Jeremy D. Popkin to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademarknotice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

First edition published by Prentice Hall 1995 Seventh edition published by Routledge 2020

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names: Popkin, Jeremy D., 1948- author.

Title: A short history of the French Revolution / Jeremy D. Popkin.

Description: Eighth edition. | New York : Routledge, 2024. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2023024756 (print) | LCCN 2023024757 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781032497372 (hardback) | ISBN 9781032532417 (paperback) | ISBN 9781003412120 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: France—History—Revolution, 1789–1799. | France— History—Consulate and First Empire, 1799–1815. | Revolutions— History—19th century.

Classification: LCC DC148 .P67 2024 (print) | LCC DC148 (ebook) |

DDC 940.2/7—dc23/eng/20230719

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023024756

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023024757

ISBN: 978-1-032-49737-2 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-032-53241-7 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-41212-0 (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003412120

Typeset in Berling by codeMantra

Contents

Images

Figures

Documents

Preface to the Eighth Edition

JEREMY D. POPKIN

Acknowledgments

1. The Origins of the French Revolution

The Problems of the Monarchy

The Failure of Reform

Social Structure and Social Crisis

The Third Estate

The Lower Classes

New Ideas and New Ways of Living

The Growth of Public Opinion

Critical Thinking Questions

2. The Collapse of the Absolute Monarchy, 1787–1789

The Prerevolution

The Assembly of Notables

From Failed Reforms to Revolutionary Crisis

The Summoning of the Estates General

The Parliamentary Revolution

The Storming of the Bastille

Critical Thinking Questions

3. The Revolutionary Rupture, 1789–1790

The Experience of Revolution

The “Abolition of Feudalism” and the Declaration of Rights

The Constitutional Debates

The October Days

Defining Rights and Redrawing Boundaries

The Expropriation of Church Lands and the Assignats

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy

The Revolution and Europe

Critical Thinking Questions

4. The Defeat of the Liberal Revolution, 1790–1792

The New Political Culture

The King’s Flight and the Crisis of 1791

The Last Months of the National Assembly

The Legislative Assembly

Revolt in Saint-Domingue and Unrest at Home

The Move toward War

The Impact of War

The Overthrow of the Monarchy

Emergency Measures and Revolutionary Government

The Failure of the Liberal Revolution

Critical Thinking Questions

5. The Convention and the Radical Republic, 1792–1794

The Trial of the King

Mounting Tensions

The Victory of the Montagnards

Radicalism and Terror

The Dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety

Revolutionary Culture

The Radical Revolution and the Social Order

The Great Terror and Thermidor

The Revolution Victorious

Thermidor

Critical Thinking Questions

6. The Return to Order, 1794–1799

The “Bourgeois Republic” and the Search for Order

The Thermidorian Reaction

The Defeat of the Sans-Culottes

Counterrevolution and the Constitution of 1795

The Directory

The Directory, Europe, and the Colonies

The “Politics of the Balance”

The “Second Directory”

The Fall of the Directory

Critical Thinking Questions

7. The Napoleonic Consulate, 1799–1804

The Consul and the Consulate

Napoleon’s Career

The Institutions of the Consulate

Napoleon’s Consolidation of Power

The Peace of Amiens and the Concordat

Elements of Opposition

Critical Thinking Questions

8. The Napoleonic Empire, 1804–1815

The Resumption of War

From Ulm to Tilsit

The Continental System

The Empire at Home

The Social Bases of the Empire

Culture under the Empire

The Decline of the Empire

The Invasion of Russia

The Hundred Days

Critical Thinking Questions

9. The Revolutionary Heritage

The Postrevolutionary Settlement

State and Nation

The Revolution’s Impact in the World

The French Revolution as History

The Jacobin Historical Synthesis

The Revisionist Critique

Postrevisionist Studies of the Revolution

Critical Thinking Questions

Appendix Chronology of Principal Events during the French Revolution

Prerevolutionary Crisis (January 1, 1787–May 5, 1789)

The Liberal Revolution (May 5, 1789–August 10, 1792)

The Radical Revolution (August 10, 1792–July 27, 1794)

The Thermidorian and Directory Periods (July 27, 1794–November 9, 1799)

The Napoleonic Period (November 9, 1799–June 18, 1815)

Suggestions for Further Reading

Journals and Reference Works

Specialized Titles: Select Bibliography

Index

Lessons for a King

The future Louis XVI was born in 1754, under the reign of his grandfather, Louis XV (1709–1774). In 1765, Louis XVI’s father died, making him the “dauphin” or immediate heir to the throne. Realizing that the young boy might at any time have to assume the responsibilities of kingship, his tutor had him write out a long summary of the principles underlying France’s absolute monarchy.

The future king wrote that it was his duty to protect his realm and his subjects, and that, in order to do this, “kings have received from God himself the greatest and the most absolute power that He has ever given any man over other men.” He was to use his power for the good of his subjects, but, in order to do so, his government needed “to have an absolute and irresistible force, always capable to enforce obedience.” In France, especially, “it is an essential characteristic of the French monarchy that every kind of power resides in the king’s hands alone, and that no body or individual can claim independence from his authority.”

The precepts young Louis was taught sometimes used language that would also be employed by the revolutionaries. He was told that his subjects had God-given rights to “life, honor, liberty, and the property of the goods that each individual possesses,” and that the laws he would decree should reflect “a general will, touching all of his subjects at the same time,” an echo of a famous phrase from the Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 book, the SocialContract.

Whereas the revolutionaries would interpret the idea of rights and the notion of the general will as limits on the power of the king, however, Louis was warned that “from the weakness of kings are born the factions, the civil wars, the eruptions that shake and ruin the state.” Among the dangers he was particularly warned against was the influence of women: “Women interfere in everything in France; they involve themselves in every kind of business, they are behind all intrigues.”

Source: Louis XVI, Réflexionssur mes entretiens avec M. leduc deVauguyon (Paris: J.P. Aillaud, 1851). Translation by Jeremy D. Popkin.

The kingdom that the future Louis XVI was going to inherit had grown through a long series of conquests and acquisitions that transformed it from a medieval principality centered around the capital city of Paris into the largest and most populous state in Europe, with around 28 million inhabitants in 1789; about 1 million more people, mostly enslaved Black people, lived in France’s overseas colonies. The kings of the Bourbon dynasty, the ancestors of Louis XVI, ruler at the time of the Revolution, had all engaged in warfare to enlarge their realm. They had built up a kingdom that extended from the lowlands of Flanders in the north to the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean Sea in the south, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Rhine River and the Alps in the east, and that included colonies in Canada, the Caribbean, and the Indian subcontinent. To do so, they had built up a costly military machine. Under Louis XIV, king from 1643 to 1715, the French army had grown to 400,000 men, the largest force Europe had ever seen, which made other rulers fear that France aimed to dominate the entire continent. Louis XV and Louis XVI were less aggressive, but they nonetheless felt a responsibility to keep France strong and to protect its interests and its reputation abroad.

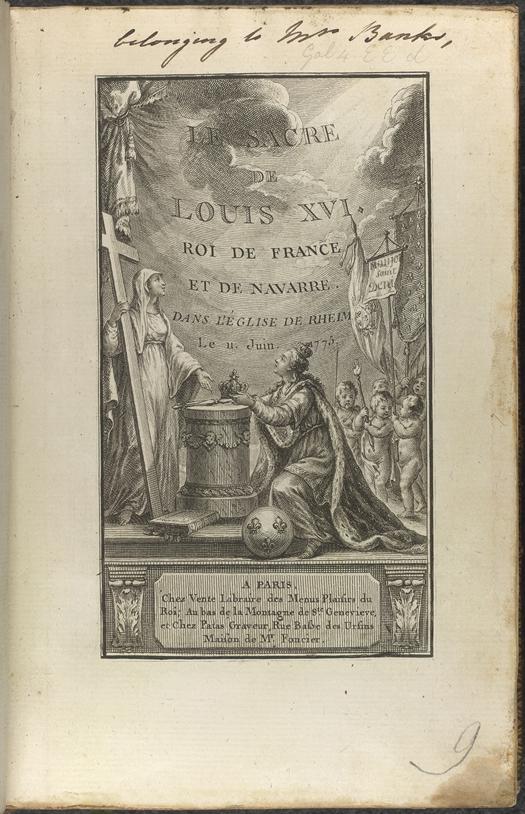

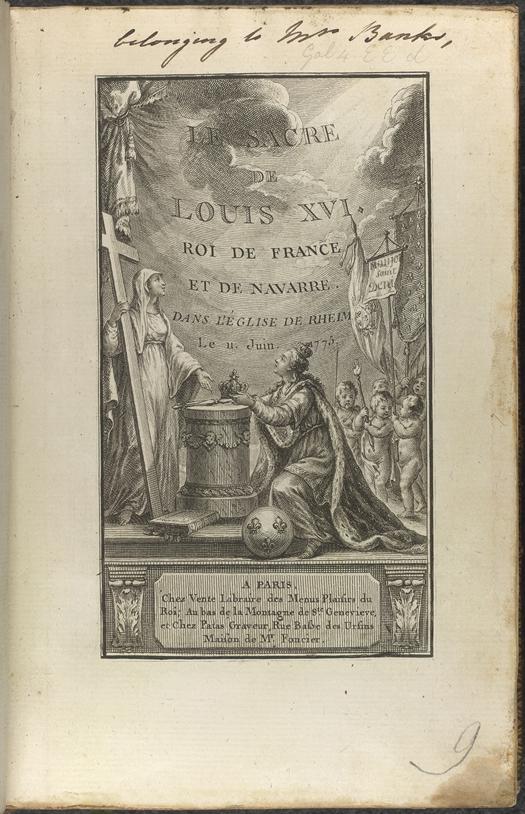

Image 1.1 Coronation of Louis XVI

Traditional symbols dominate this illustration of Louis XVI’s coronation in 1775. The king takes his crown from a saint holding a cross, indicating the divine origins of his powers, while angels behind him carry banners and emblems associated with the French monarchy since the Middle Ages. This engraving gives no hint of the challenges to the Church and established institutions that were to lead to the French Revolution a few years later.

Source: Louis XVI/British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images.

Some of the problems that led to the French Revolution stemmed from costly efforts to maintain France’s position relative to the other European states and especially from its rivalry with the British. Britain, a naval power with a fast-growing economy, was able to concentrate on building up its colonial empire, while France also had to contend with rivals on the continent, particularly Austria and Prussia. The country’s poor performance in the eighteenth century’s most extensive conflict, the Seven Years War (1756–1763), raised fears that the French monarchy was failing to cope with these challenges. While Prussian king Frederic the Great, a brilliant commander, inflicted humiliating defeats on French armies in Europe, the British used their control of the seas to capture French colonial possessions in India and North America. Two years before Louis XV’s death in 1774, France stood by helplessly as Prussia, Austria, and Russia annexed provinces belonging to Poland, one of its traditional allies.

Early in Louis XVI’s reign, France rebounded from these foreign policy defeats by aiding Britain’s North American colonies in their war for independence. French troops and the French fleet significantly aided the Americans, and France hosted the peace conference at which Britain conceded the colonies’ independence in 1783. However, this success cost France a great deal of money and brought none of the tangible rewards in the form of new territories that usually marked a victory. Fear of adding even more debt kept

France from aiding its Dutch allies when Prussia intervened in the Netherlands in 1787. French public opinion blamed the monarchy for allowing a smaller power to humiliate it.

In addition to maintaining his power and glory, the French king was expected to see to the welfare of his subjects. The king maintained the country’s main roads. His courts provided justice for his subjects. In times of crop failure, royal officials in the provinces were expected to organize relief. Through its system of royal academies, the government subsidized writers, artists, scientists, doctors, and even veterinarians; starting in the 1760s, the king funded training for midwives, in an effort to reduce rates of maternal and infant mortality. The most visible royal expense, the upkeep of the court at the palace of Versailles, accounted for only a small percentage of the monarchy’s spending, but it was a symbol of extravagance that made it difficult to win support for reforms meant to enable the monarchy to meet its other obligations.

To carry out all these responsibilities, the royal government had developed an extensive administrative network. Louis XIV, the most strong-willed and efficient of the Bourbon kings, established a system of intendants, appointed royal officials stationed in each of the country’s provinces and responsible for carrying out royal orders. Subordinate officials extended the intendants’ reach to smaller towns. France’s system of administration was considerably more centralized than that of most other European states; in theory, royal power could be exerted everywhere in the kingdom.

In practice, however, this centralized administration faced many obstacles. Each province, each region, each town had its own special laws and institutions, which the intendant could not simply ignore. From the humblest peasant to the haughtiest noble, the king’s subjects were imbued with the notion that they had rights and privileges that they were entitled to defend. This legalistic outlook was reinforced by the conduct of the royal appeals courts, the 13 parlements, whose judges, all members of the nobility, claimed the right to review all royal laws and edicts to ensure that they were in conformity with the traditional laws of the realm.

Although the parlements were royal courts, the king’s influence over the judges was limited because, along with many other officials, they literally owned their positions. These posts were desirable because offices conferred social prestige and, in many cases, granted their holders noble status. They could be passed down to heirs regardless of their qualifications or sold for a profit. The sale of government posts brought in revenue for the government, but it reduced the efficiency of the administration. Venal officeholders were often more interested in promoting their own interests and those of the institutions they belonged to than in following orders from Versailles.

The parlements claimed that it was their duty to resist measures that violated the traditional laws of the kingdom and the rights of the king’s subjects, such as efforts to raise taxes. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the judges started to use a new term to justify their actions: they claimed to be defending the interests of the “nation” against arbitrary authority. In practice, the parlements’ objections often amounted to a defense of privileged groups’ special interests, including those of the judges. But the parlements’ denunciations of arbitrary rule and their insistence that the “nation” had a right to participate in political decision-making spread ideas about representative government among the population. Paradoxically, the privileged noble judges of these royal courts were forerunners of a revolution that was to sweep away all special privileges.

The Failure of Reform

Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, royal ministers recognized that the French government needed more revenue if it was going to maintain its international standing and meet its domestic obligations. But the problem of raising taxes illustrated better than anything else the institutional weakness of the monarchy. In theory, the king should not have had much trouble raising more money. Unlike the king of Great Britain, France’s ruler

did not need to negotiate with a parliament before he collected and spent money. The size of the kingdom and the need for a large army to defend it from foes who, unlike those of Britain, could easily threaten its borders had limited the role of the assembly of the Estates General—France’s equivalent to the British Parliament—and finally enabled kings to stop convening it altogether after 1614. They had established their right to collect traditional taxes without going through any legislative process. But this authority came at a price: unlike the king of Britain, the French ruler lacked any regular mechanism for negotiating an increase in revenue as the kingdom’s needs grew. He could collect only those taxes that had become customary over the years and had been approved by the parlements, and many subjects were able to evade payments because of equally customary exemptions.

A cumbersome and inefficient system of tax collection was another handicap for the prerevolutionary monarchy. Different provinces and different groups of subjects all paid different taxes. Rather than employing tax collectors who worked directly for the king, the government leased out the collection of most taxes to wealthy entrepreneurs, called tax farmers, who paid the treasury a set fee in exchange for the right to collect revenue in a given region. This system provided the monarchy with a dependable flow of income, but it also gave the tax farmers the incentive to squeeze as much as they could from the population, while forwarding as little as possible to Versailles. The tax farmers were also responsible for enforcing the government’s unpopular monopoly on the sale of tobacco; their armed guards engaged in frequent confrontations with smugglers who often had the population’s support because they sold the product at lower prices. The multiplicity of taxes and taxcollection enterprises made rational management of the royal income nearly impossible.

The last decades of the monarchy witnessed repeated efforts to streamline and increase taxes and to make the French economy more productive, so that the government could extract more money from its subjects. In the 1760s, the government, urged on by a

group of economic reformers known as the Physiocrats who preached the virtues of free trade, abolished traditional restrictions on grain sales, hoping to encourage production and thereby to expand the tax base. These plans broke down when bad harvests produced shortages that led to popular protests. In 1770, Louis XV appointed a strong-minded set of ministers who made a systematic effort to overcome the obstacles that were frustrating reform. The justice minister, Maupeou, ousted the obstructionist judges of the parlements, replacing them with more pliable appointees, while the finance minister, Terray, wrote off much of the royal debt.

Maupeou’s attack on the parlements was widely denounced as a “coup” that violated the kingdom’s fundamental laws, and, when Louis XV died unexpectedly in 1774, his inexperienced successor, Louis XVI, was persuaded to dismiss the controversial ministers and abandon their policies. The new ministers he appointed made their own efforts at reform, however. In 1775 and 1776, Turgot, the controller-general or finance minister, tried to revamp the organization of France’s economy even more extensively than his predecessors in the 1760s. In 1775, Turgot’s abolition of restrictions on the grain trade sparked the “flour war,” a wave of riots against high grain prices. His effort to do away with the urban guilds, whose regulations restricted competition in the production and sale of manufactured goods, inspired resistance from guild members, objections from women who opposed the merger of guilds reserved for them with organizations dominated by men, and protests from the parlements. Turgot’s more cautious successor, Necker, tried to save money by eliminating unnecessary offices and collecting taxes more efficiently. In 1781, he caused a sensation by publishing a summary of the government’s income and expenses, giving the public an unprecedented look at the monarchy’s financial condition. At the same time, however, Necker had to borrow extensively to finance the American war, driving the monarchy further into debt.

Government reform efforts were not limited to fiscal matters. In the last decades before the Revolution, the monarchy took a number of measures that foreshadowed the more sweeping changes that

followed 1789. It asserted its power to regulate the Church by suppressing some of the many convents and monasteries inherited from the past. New ideas about human rights were reflected in the abolition of torture in judicial cases and the abolition of serfdom on the royal estates. In the late 1770s, the minister Necker introduced representative assemblies in several provinces, trying to give public opinion some voice in lawmaking and administration. The country’s Protestant minority, officially outlawed under Louis XIV, received basic civil rights in 1787, and edicts meant to limit the worst abuses of slaves in the colonies were issued in 1784 and 1785.

The fact that royal ministers undertook so many reform efforts shows that they were well aware of the problems undermining the French monarchy and of the new ways of thinking that were spreading in French society. The result demonstrated the accuracy of the celebrated nineteenth-century French historian Alexis de Tocqueville’s comment that “the most perilous moment for a bad government is one when it seeks to mend its ways.”2 To justify their reform proposals, the royal ministers themselves criticized longestablished customs and institutions, thereby undermining the legitimacy of the existing order. Those adversely affected by proposed reforms defended themselves by challenging the government’s right to arbitrarily change time-honored institutions. The problems that provoked the French Revolution were thus not simply due to an outdated and inefficient structure of government. They were also rooted in France’s complex, hierarchical social structure.

2 Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the French Revolution (New York: Doubleday, 1955), 177.

Social Structure and Social Crisis

French society before 1789 was largely structured on the principle of corporate privilege rather than individual rights. The French king’s subjects were all members of social groups—corps, or collective bodies—that claimed special rights setting them apart from others.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

F��. 30. A piece of pork heavily infected with pork measles (Cysticercus cellulosæ), natural size. (Stiles, Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

F��. 31. An isolated pork-measle bladderworm (Cysticercus cellulosæ), with extended head, greatly enlarged. (Stiles, Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

Causation. The cause of cysticercus disease in the pig may be summed up in one phrase—viz., ingestion of eggs or embryos of Tænia solium.

Young animals alone seem to contract the disease. After the age of eight to ten months they appear almost entirely proof against it.

It is very rare in animals reared in confinement, but is relatively common in those roaming at liberty; because they are much more likely to discover human excrement and the embryos of tænia. The eggs having been swallowed, the six-hooked embryos are set at liberty in the intestine, perforate the tissues, enter the vessels, and are carried by the blood into all parts of the body. Those alone develop well which reach the interstitial and intermuscular

connective tissue. The others in the viscera usually disappear. Their presence in the depths of the muscles produces slight general disturbance and signs of local irritation, due to the development of the cyst itself. At the end of a month the little vesicle is large enough to be visible to the naked eye; in forty to forty-five days it is as large as a mustard seed, and in two months as a grain of barley. Its commonest seats are the abdominal muscles, muscular portions of the diaphragm, the psoas, tongue, heart, the muscles of mastication, intercostal and cervical muscles, the adductors of the hind legs, and the pectorals.

Symptoms. The symptoms of invasion are so little marked as usually to pass undetected. Occasionally, when large quantities have been ingested, signs of enteritis may occur, but these are generally ascribed to some entirely different cause. In some cases there is difficulty in moving, and the grunt may be altered.

Certain authors declare that the thorax is depressed between the front limbs, but this symptom is of no particular value, and is also common to osseous cachexia and rachitis. Paralysis of the tongue and of the lower jaw is of greater importance. In exceptional cases, where the cysticerci are very numerous and penetrate the brain, signs of encephalitis, vertigo, and turning sickness (gid, sturdy) may be produced. These signs, however, disappear, and the cysticerci undergo atrophy. Interference with movement may give rise to suspicion when the toes of the fore and hind limbs are dragged along the ground, and thus become worn. This peculiarity is due to the presence of cysts in the muscles of the limbs, but it occurs in an almost identical form in osseous cachexia.

One symptom alone is pathognomonic, and it appears only at a very late stage—viz., the presence of cysts under the thin mucous

F��. 32.—Several portions of an adult porkmeasle tapeworm (Tænia solium), natural size.

membranes which are accessible to examination, such as those of the tongue and eye.

Visual examination then reveals beneath these mucous membranes the presence of little greyish-white, semi-transparent grains the size of

(Stiles, Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

F��. 33.—Large (a) and small (b) hooks of pork-measle tapeworm (Tænia solium). × 280. (After Leuckart.)

a grain of barley, or even larger. Unfortunately, in an animal so difficult to handle as the pig, this visual examination is decidedly troublesome, and is usually replaced by palpation. In many instances the disease does not attract attention during the patient’s life, and is only discovered on slaughter in consequence of the lesions by which it is characterised.

Diagnosis. As the characteristic lesions of cysticercus disease are to be found in the depths of the muscular and connective tissues, and as the external symptoms may be regarded as of doubtful significance, the diagnosis can only be confirmed during life by manual examination of the tongue. This examination of the tongue has been practised since the earliest times. Aristophanes even speaks of it, and in the Middle Ages it was performed under sworn guarantees. The regulations concerning the inspection of meat have finally led to the suppression of this calling.

In this method of examining the tongue, the operator commences by throwing the animal on its side, usually on the right side, and holding it in this position by placing his left knee on its neck. He then

F��. 34.—Mature sexual segments of pork-measle tapeworm (Tænia solium), showing the divided ovary on the pore side. cp, Cirrus pouch; gp, genital pore; n, nerve; ov, ovary; t, testicles; tc, transverse canal; ut, uterus; v, vagina; vc, ventral canal; vd, vas deferens; vg, vitellogene gland. × 10. (After Leuckart.)

passes a thick stick between the jaws and behind the tusks, opens the mouth obliquely, raising the upper jaw by manipulating the stick. Finally he fixes one end of this last by placing his foot upon it, and holds the other extremity by slipping it under his left arm. In this position he is able to grasp the free end of the tongue and by digital palpation to examine the tongue itself, the gums, the free portions of the frænum linguæ, etc.

F��. 35. Gravid segment of pork-measle tapeworm (Tænia solium), showing the lateral branches of the uterus enlarged. (Stiles, Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

If he discovers cysts, the diagnosis is confirmed, but failure to do so by no means disposes of the possibility of infection. Railliet declares that about one animal in four or five shows no cysts beneath the tongue, and, moreover, fraud is possible in this connection, it being quite possible to prick the little cysts with a needle so that the liquid contents escape, and examination gives no positive result. For these reasons intra-vitam examination alone is now discounted, and the chief reliance is placed on post-mortem search.

Prognosis. The prognosis is very grave, not on account of danger to the lives of the infected, but because infected meat may be offered for human consumption. Should such meat, in an insufficiently cooked condition, be eaten by man, its ingestion is followed by the development of Tænia solium. If cooking were always perfect it

would destroy the cysticerci, but the uncertainty in this respect should prevent such meat being consumed. The cysticerci are killed at a temperature of 125° to 130° Fahr.

F��. 36.—Eggs of pork-measle tapeworm (Tænia solium): a, with primitive vitelline membrane; b, without primitive vitelline membrane, but with striated embryophore. × 450. (After Leuckart.)

Lesions. The lesions are represented by cysts alone—i.e., by semitransparent bladders, each of which contains a scolex or head armed with four suckers and a double crown of hooks. The little bladders are most commonly found in the muscles, lodged in the interfascicular tissue, which they slightly irritate.

The number present varies extremely, depending on the intensity of infestation and the number of eggs swallowed. Whilst in some cases difficult to discover, in others they are so numerous that the tissues appear strewn with them.

They are commonest in the muscles of the tongue, neck, and shoulders, in the intercostal and psoas muscles, and in those of the quarter.

The viscera—viz., the liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, etc.—are less commonly infested, and in these organs the cysts degenerate very rapidly. In animals which have been infested for a long time, the cysts may even have undergone caseo-calcareous degeneration, the liquid being absorbed and the lesions presenting the appearance of little oblong firm nodules.

On cutting through masses of muscle the vesicles protrude from between the bundles. In young animals, infestation with cysticerci causes wasting and ill-health; subsequently the patients improve in appearance, later on fatten, and gain marketable condition.

Of the carcases examined in Prussian slaughter-houses between 1876–82, one in every 305 was found infested; between 1885–93, one in every 537.

Treatment. There is no curative treatment. Only preventive measures are of value. These are confined to rendering it impossible for animals to ingest eggs of the Tænia solium.

Cysticercus disease is rare in the north, centre, and east of France, and in districts where animals are reared in confinement. It is commoner where pigs are at liberty, such as Limousin, Auvergne, and Perigord. It is frequent in North Germany, where the custom of eating half-cooked meat contributes to the propagation of Tænia solium. It is also frequent it Italy.

F��. 37.—Half of hog, showing the portions most likely to become infested with pork measles. (After Ostertag.)

F��. 38. Cysticercus cellulosæ in pork. c, Cysts; v, fibrous tissue capsule which forms around the cyst.

BEEF MEASLES.

Causation. The disease of beef measles is due to the penetration into the connective and muscular tissues of embryos of the Tænia saginata, or unarmed tænia of man.

This disease, unlike that of the pig, has only been recognised within comparatively recent times, and only after Weisse’s experiments (St. Petersburg, 1841) on feeding with raw flesh was attention drawn to it, although as early as 1782 the Tænia saginata had been described by Goëze.

Measles in the ox is rarely seen in France, but is common in North and East Africa. Alix has found it in Tunis, Dupuys and Monod in Senegal, and it is common in the south of Algeria. The disease is due

simply to oxen swallowing eggs or embryos of the unarmed tænia, a fact which explains the frequency of the disease in places where the inhabitants are of nomad habits, and consequently disregard the most elementary rules of public and general hygiene.

F��. 39. Anatomy of the Cysticercus cellulosæ (after Robin). A, Cyst; B, scolex with hooks; C, hooks; D, magnified fragment of cyst.

Furthermore, cattle in the Sahara, in Senegal and in the Indies, have a very marked habit of eating ordure, and as no attempts are made to prevent it, the risk to these animals is greatly increased.

As in the pig, the embryos which reach the stomach and intestine penetrate into the circulatory system, and are thereby distributed throughout the entire organism.

F��. 40.—Section of a beef tongue heavily infested with beef measles, natural size (Stiles, Annual Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901).

The development of the cysticercus is complete in forty days, and if swallowed by man in infected meat after this period it again gives rise to the Tænia saginata. The age of the animals seems of less importance than in the case of the pig, for Ostertag and Morot have seen cases of beef measles in animals of ten years old.

Symptoms. The symptoms are still less marked than in the pig, and in ordinary cases of infection always escape observation. Stiles, however, gives the following account of a case experimentally infected:—

F��. 41. Several portions of an adult beef-measle tapeworm (Tænia saginata) from man, showing the head on the anterior end and the gradual increase in size of the segments, natural size. (Stiles, Annual Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

“Symptoms. Four days after feeding segments of T. saginata to a healthy three-months-old calf, the patient showed a higher temperature (the normal temperature was 39·2° C.). The calf ate but little on that day, showed an accelerated pulse, swollen belly, staring coat, and upon pressure on the sides showed signs of pain. The next day the animal was more lively, ate a little, and for nine days later did not show any special symptoms except pain on pressure of the abdominal walls, and a slight fever. Nine days after the infection the temperature was 40·7° C., pulse 86, respiration 22; the calf laid down most of the time, lost its appetite almost entirely, and groaned considerably. When driven it showed a stiff gait and evident pain in the side. The fever increased gradually, and with it the feebleness and low-spiritedness of the calf, which now retained a recumbent position most of the time, being scarcely able to rise without aid, and eating only mash with ground corn. Diarrhœa commenced, the temperature fell gradually, and on the twenty-third day the animal died. The temperature had fallen to 38·2° C. During the last few days the calf was unable to rise; in fact, it could scarcely raise its head to lick the mash placed before it. Pulse was reduced by ten beats. On the last day the heart-beats were very much slower, yet firm, and could be plainly felt. Several days before death the breathing was laboured, and on the last day there was extreme dyspnœa.”

Diagnosis. In forming a diagnosis we meet with the same difficulty as in the case of the pig. It is always easy to examine the

F��. 42.—Apex, dorsal, and lateral views of the head of beef-measle tapeworm (Tænia saginata), showing a depression in the centre of the apex. × 17. (Stiles, Report U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

tongue; but when visible lesions are absent diagnosis in the case of the ox remains doubtful and problematical even more than in the pig.

In the carcase, diagnosis is much easier. The cysts are sought for, as in the pig, by making sections of muscle, those usually selected being the pterygoid, cervical, cardiac, and psoas muscles, and those of the quarters.

Prognosis.

The prognosis is grave, not indeed for the infected animals, which seem little injured by the parasite, but for human beings, who run the risk of contracting Tænia inermis by eating insufficiently-cooked meat. A temperature of 115° to 120° Fahr. destroys the cysticerci, but in roast meats the central temperature of the mass always remains below this figure.

Salting for fifteen to twenty days destroys the vitality of the parasite.

Lesions. The lesions are confined to the presence of the cyst and of two little zones of chronic inflammation immediately surrounding it. Unless heavily infested the subjects fatten just as well as others.

The vesicles are semi-transparent, ³⁄₁₆ inch to ¼ inch in length, slightly ovoid in form, and contain a tænia head with four suckers, but without hooks.

In seven to eight months the cysts undergo degeneration, the liquid is absorbed, and calcium salts are deposited throughout the mass. The lesions which remain have, in the ox, the appearance of interstitial disseminated tuberculosis.

There is no curative treatment. The infested animal recovers spontaneously with the lapse of time, for the cysticerci undergo degenerative processes, but the flesh of such animals is of little commercial value.

From a preventive standpoint we can only hope to improve matters by a gradual and progressive change in social and public hygienic conditions.

F��. 43. Sexually mature segment of beef-measle tapeworm (Tænia saginata). c.p., Cirrus pouch with cirrhus; d.c., dorsal canal; g.p., genital pore; n., lateral longitudinal nerves; ov., ovary; sg., shell gland; t., testicles; ut., median uterine stem, enlarged (in part after Leuckart); v., vagina; v.c., ventral canal, connected by transverse canal; tc., vd., vas deferens; vg., vitellogene gland.

When the life of the nomad shall have been entirely replaced by that of the highly-civilised European and private hygienic precautions have rendered it impossible for animals to obtain access to segments or eggs of the Tænia saginata, beef measles will disappear.

At present, in the countries where the disease is common, one experiences a feeling of astonishment that it is not far more frequent; for experiment has shown that a person infected with one unarmed tapeworm expels with the fæces an average of four hundred proglottides per month, each proglottis or segment of the worm

containing about 30,000 eggs, each of which is capable of developing into a tapeworm.

Beef measles is rather common in Germany, but rare in France, Switzerland, and Italy.

TRICHINIASIS TRICHINOSIS.

Trichinosis is a disease caused by the entrance into the body of the Trichina spiralis. This parasite is swallowed in the larval form, and undergoes sexual changes in the intestine, at first producing intestinal trichinosis, which represents the first phase in the development of the disease.

The trichinæ breed rapidly. The embryos penetrate into or are directly deposited in the blood-vessels, which convey them to all parts of the body, thus setting up the second phase of the disease, known as muscular trichinosis.

Trichinosis as a disease has long been recognised. Peacock in 1828 and J. Hilton in 1832 mentioned the existence of the cysts of trichinæ; Owen in 1835 gave the name of Trichina spiralis to the parasites contained in the cysts. Trichinosis being common in Germany at that time, Virchow and Leuckart undertook its investigation, but mistook other nematodes of the intestine for the Trichina spiralis. In 1847 Leydy recognised that trichinosis occurred in American pigs.

In 1860 Zenker found muscular and intestinal trichinosis on post-mortem examination of a girl who had been suspected of suffering from typhoid fever, and a carefully conducted inquiry revealed the fact that this girl had some time previously eaten a quantity of raw ham. Virchow and Leuckart returned to their

F��. 44.—Gravid segment of beef-measle tapeworm (Tænia saginata), showing lateral branches of the uterus, enlarged.

(Stiles, Annual Report

U.S.A. Bureau of Agriculture, 1901.)

investigations, and the life history of the parasite soon became definitely known.

Causation. Trichinosis is capable of attacking all mammifers without exception, from a man to a mouse; and most animals which can be made the subjects of experiment contract the disease in varying degrees.

F��. 45.—Egg of beef-measle tapeworm (Tænia saginata), with thick egg-shell (embryophore), containing the six-hooked embryo (oncosphere), enlarged. (After Leuckart.)

The intestinal form is seen in birds, but the muscles do not become infested by the embryos.

Cold-blooded animals are proof against the disease.

After the ingestion of meat containing cysts of the parasite, the processes of gastric and intestinal digestion set the larvæ at liberty. These larvæ become sexual at the end of four to five days, and the females, which are usually twice as numerous as the males, begin laying eggs from the sixth day, continuing for a month to six weeks. Each female lays approximately from 10,000 to 15,000 eggs. The

embryos perforate the intestinal walls, pass into the circulation, and are hurried into all parts of the system. This period of infestation constitutes the first phase of the disease.

Askanazy, in 1896, suggested that it was not the embryos which perforated the intestinal walls and thus reached the blood-vessels, but the fertilised female trichinæ themselves, which entered the terminal chyle vessels and laid their eggs directly within them.

This observation is of great interest, for it contradicts the view held by Leuckart and proves that treatment is useless even in the first phase.

The males are about ¹⁄₁₆ inch in length, the females ⅛ inch to ⁵⁄₃₂ inch, and are ovoviviparous.

F��. 46.—Male trichina from the intestine. (Colin.)

Symptoms. The symptoms lack precise character, even when the disease is known to be developing, and moreover they have only been carefully observed in experimental cases. As soon as the laying period begins, signs of intestinal disturbance may be observed, possibly due to embryos perforating the intestinal walls (if we accept Leuckart’s view), or, according to Askanazy, to adult females penetrating the chyle vessels and disturbing intestinal absorption.

These symptoms are only appreciable in cases of “massive” infestation. If slight, the disturbance passes unperceived. In severe cases the symptoms consist of diarrhœa, loss of appetite, grinding of the teeth, abdominal pain in the form of dull colic, and sometimes irritation of the peritoneum. The embryos carried by the circulation then escape into the tissues and, like the cysticerci, become encysted, preferably in the muscles, in the interfascicular connective tissue towards the ends of the bundles. Each (asexual) parasite plays the part of a foreign body, causing infiltration of serum and exudation of

leucocytes in its neighbourhood, and soon becoming encysted in the interior of a little ovoid space surrounded by a fibro-fatty wall. Fat granules accumulate at each end of the cyst.

F��. 47.—Free larval trichina. (Colin.)

F��. 48.—Trichinæ encysted in the muscular tissue. (Colin.)