THE AESTHETICS OF DISAPPEARANCE

Paul Virilio

Introduction by Jonathan Crary

Translated by Philip Beitchman

Jonathan Crary

Introduction to Aesthetics of Disappearance

Nearly three decades have passed since the publication of Esthetique de fa disparition in 1980. The immediate context in which it was written was the late 1970s, now to all of us like a foreign country. This was the bipolar world of the Cold War; globalization (though very much occurring at the time) was not on everyone's mind; most people still used typewriters, not yet word processors; even the VCR had not yet become a pervasive consumer item; the Internet was years away from widespread implantation; and the late 20th-century catastrophes ofthe Balkans, Rwanda, the Persian Gulfand elsewhere were hardly foreseeable from within the 1970s balance of terror management system.

So how now, in the early 21st century, does this remarkable Paul Virilio text resonate? Perhaps at the least, its rereading can help correct some ofthe wrongheaded characterizations

of his work that have accumulated In these intervening years. This text in particular makes plain what has been obvious to any careful reader of Virilio all along: he never was or is a critic/historian of media or a philosopher of technology in the way these labels might apply to figures as disparate as Ellul, McLuhan, Kittler or Stiegler. Of course his work has been uniquely valuable to anyone interested in these areas but Virilio's guiding preoccupations lie elsewhere. To use quasi-Kantian terms, it is more accurate to see his work as a relentless examination ofthe conditions which make experience possible. Bur it is hard to imagine a more sweeping abandonment of the universalizing presumptions of Kant's critique than the arguments of The Aesthetics of Disappearance (the irony of the title is notable in this respect). For Kant, the essential role of time was to coherently unite all the elements of knowledge by establishing a relation between thought and perception. That is, time was the necessary condition of any particular experience we have; time is what makes perception possible and intelligible. Virilio's project is to uncover the role of time in the multiple and abyssal de-linkages of perception and its possible objects. But he is hardly interested in developing a new philosophical account of time, in the footsteps of Bergson, Husserl, Heidegger or others. His stance is more Nietzschean in his articulation of time as irreducibly plural, discontinuous, non-homogenous, and reversible. As they were for Foucault in the 1970s, questions oftime for Virilio are ofinterest primarily as the consequences ofa given field

of forces and effects. Thus both Foucault and Virilio were aligned, at least for a time, in their related concern with how individual and collective experience is shaped territorially by strategic relations ofpower.

It should be stressed that Virilio is hardly proposing that prior to the industrial revolution, humans had some more "natural" relation to temporality. At the heart of Aesthetics ofDisappearance is the insistence that experience as duration has always been constituted as de-synchronized and fractured. This is the importance of his thematic of "picnolepsy," his de-pathologizing of the epileptic "petit mal." Perhaps he could have chosen another, equally effective illustration to make his point, for he is writing not from the standpoint of medical physiology but from that of the phenomenology of perception, even if his project diverges from most of the work done within the framework of the latter (including by Merleau-Ponty). Virilio's "phenomenology " (for which he would substitute the term "logistics") discovers perception to be made of breaks, absences, dislocations as well as by the capacity to produce patchworks of various contingent worlds.

Historically, there have been a wide range of ways in which societies have responded to the vagaries and inconsistencies of perception, for example, the many pre-modern privilegings ofstates oftrance, possession, or daydream and the ways these states were creatively integrated into collective life. But Virilio implies that wherever forms of logical or rational thought have dominated, especially in the West,

the vacancies and absences in perception are assimilated and de-singularized into a homogenized and potentially controllable texture ofevents.The goal ofreason, he says, is "to redistribute methodically the occasional eliminations of picnoloepsy...to deny to particular absences any active value."

Thus Virilio is demonstrating that an individual is never organically situated in some a priori river of time but rather that history has always been a matter of shifting arrangements and techniques through which provisional systems of time are produced.The problem ofspeed, for example, with which Virilio's thought is popularly identified, is hardly something specific to recent modernity. Every historical epoch, whether the Roman empire or the Napoleonic, is understandable in terms ofspeeds, forms ofmotion and stasis, and their possibilities ofmodification.The last 150 years are different only in the rate ofchange and the intensified accumulation of overlapping technologies and networks. Surely this much broader historical vision of speed and territory was part of what appealed to Deleuze and Guattari in their use of Virilio's ideas in Mille Plateaux (also published in 1980). At the same time, the Aesthetics of Disappearance affirms that speeds are produced not just by what are commonly thought of as technologies, but by vectors and itineraries of many kinds.

One of the decisive elements of the present text (and of course in much ofVirilio's writing) is cinema and the cinematic. In these pages, cinema is important as one of the

most pervasive ways in which the absences in human perceptions are both supplemented and redeployed by an external production of speed, displacement and luminosity. Virilio certainly does not underestimate the consequential significance of the invention of the cinematograph in the 1890s but his sense of the cinematic is far more expansive and suggestive than most perspectives on film history. Components ofa cinematic machine have been in use over many centuries: forms of projection, moving images, immobile voyages, and visionary illuminations. No doubt the extraordinary fascination on the part ofartists and film makers with Joan ofArc in the first half of the 20th century was a dim recognition ofa kindred picnoleptic in the 15th century who watched her own "home movies" as a girl in the countryside. But the various cinemas of the long pre-cinematic are in no sense anticipating their teleological assembly and unification at the hands of the Lumiere brothers. As is clear from the our 21st century vantage point, the cinematograph was itself only a temporary aggregate of parts that have been discarded or subsequently recombined into other proliferating "vision machines."

As Virilio wrote in the late 1970s, psychoanalytic film theory was exploring the similarities between the movie spectator and the sleeper/dreamer. But unlike Metz and others, Virilio saw the cinematic as part of a much wider breakdown ofthe boundaries between sleeping and waking, between the real and dreaming. Like Deleuze, Virilio understood cinema as part of a crisis of belief, in which we no

longer believe in the world. This loss of faith is inseparable from an on-going incapacitation and neutralization of vision. Over the last century vision has increasingly been denied any hierarchy ofobjects within which the important could be distinguished from the trivial, as figure might be isolated from ground. Without these distinctions vision becomes a derelict and uninflected mode of reception and inertia, incapable of seeing. Along with its motorized speeds, cinema and an array of other luminous screens announce the installation ofpermanent daythat by now has become part of the 24/7 globalized present we all inhabit. Virilio in the late 1970s was already specifying the broad inscription of human life into a homogenous global time without pauses or rest, a milieu of continuous functioning, ofcountless operations that are effectively ceaseless. 24/7 is a time that no longer passes, beyond dock time, beyond any measure oflived human duration.

This is why Virilio's epiphanic account of Howard Hughes remains so compelling. Hughes stands as a personification of the overlapping effects of speed (his obsession with flight) and light (his control ofthe movie industry) but also in his later life as bleakevidence ofthe unintended consequences of these new configurations. Hughes' atemporal isolation as he watched and rewatched screenings of Ice Station Zebra prefigures all the forms of timelessness and non-stop digital management of our own micro-programmed and atopic lives. In Virilio's words, "the internment of bodies is no longer in the cinematic cell oftravel but in a cell outside

of time, which would be an electronic terminal where we'd leave it up to the instruments to organize our most intimate vital rhythms, without ever changing position ourselves, the authority ofelectronic automatism reducing our will to zero." Intru(luC'ti(XI ! 15

The world as we see it is passing.

- Paul ofTarsus

The lapse occurs frequently at breakfast and the cup dropped and overturned on the table is its well-known consequence. The absence lasts a few seconds; its beginning and its end are sudden. The senses function, but are nevertheless closed to external impressions. The return being just as sudden as the departure, the arrested word and action are picked up again where they have been interrupted. Conscious time comes together again automatically, forming a continuous time without apparent breaks. For these absences, which can be quite numerous, hundreds every day most often pass completely unnoticed by others around-we'll be using the word "picnolepsy" (from the Greek, picnos: frequent).l However, for the picnoleptic, nothing really has happened, the missing time never existed.At each crisis, without realizing it, a little ofhis or her life simply escaped.

Children are the most frequent victims, and the situation ofthe young picnoleptic quickly becomes intolerable. People want to persuade him oftheexistence ofevents that he has not seen, though they effectively happened in his presence; and as

he can't be made to believe in them he's considered a half-wit and convicted of lies and dissimulation. Secretly bewildered and tormented by the demands ofthose near him, in order to find information he needs constantly to stretch the limits ofhis memory. When we place a bouquet under the eyes of the young picnoleptic and we ask him to draw it, he draws not only the bouquet but also the person who is supposed to have placed it in the vase, and even the field offlowers where it was possibly gathered. There is a tendency to patch up sequences, readjusting their contours to make equivalents out ofwhat the picnoleptic has seen and what he has not been able to see, what he remembers and what, evidently, he cannot remember and that it is necessary to invent, to recreate, in order to lend verisimilitude to his discursus.2 Later, the young picnolepticwill himself be inclined to doubt the knowledge and concordant evidence ofthose around him; everything certain will become suspect. He'll be inclined to believe (like Sextus Empiricus) that nothing really exists; that even if there is existence, it cannot be described; and that even ifit could be described, it could certainly not be communicated or explained to others.

Around 1913 Walter Benjamin noted: "We know nothing ofwoman's culture, just as we know nothing ofthe culture of the young." But the trivial parallel-woman/child-can find itselfjustified in the observation ofDoctor Richet: "Hysterical women are more feminine than other women. They have transitory and vivid feelings, mobile and brilliant imaginations and, with it all, the inability to control, through reason and judgment, these feelings and imaginations."3

Just like women, children assimilate vaguely game and disobedience. Childhood society surrounds its activities with a veritable secret strategy, tolerating with difficulty the gaze of adults, before whom they sense an inexplicable shame. The uncertainty of the game renews picnoleptic uncertainty, its character at once surprising and reprehensible. The little child who, after awaking with difficulty, is absent without knowing it every morning and involuntarily upsets his cup, is treated as awkward, reprimanded and finally punished.

I'll transcribe here, from memory, the statements made by the photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, in the course of a recent interview:

Q: You've talked to me just now of a trap for vision, something like that, is that your camera?

A: No, not at all. It's before, something I did when I was little. When I half-closed my eyes, there remained only a narrow slot through which I regarded intensely what I wanted to see. Then I turned around three times and thought, by so doing, I'd caughttrapped-what I was looking at, so as to be able to keep indefinitely not only what I had seen, but also the colors, the noises. Of course, in the long run, I realized that my invention wasn't working. It's then only that I turned to technical tools for facilitating it.

Another photographer has written that his first darkroom was his room when he was a child and his first lens was the luminous crack of his closed shutter. But the remarkable thing with the little Lartigue is that he's assimilated his own body to the camera, the room of his eye to a technical tool, the time of the exposure to turning himself around three times.

He perceives a certain pattern there, and also sees that this pattern can be restored by a certain savoir faire. The child Lartigue has thereby stayed in the same place, and is, nevertheless, absent. Owing to an acceleration of speed, he's succeeded in modifying his actual duration; he's taken it off from his lived time. To stop "registering" it was enough for him to provoke a body-acceleration, a dizziness that reduced his environment to a sort ofluminous chaos. But with each return, when he tried to resolve the image, he obtained only a clearer perception of its variations.

Child-society frequently utilizes turnings, spinning around, disequilibrium. It looks for sensations ofvertigo and disorder as sources ofpleasure.

The author of the famous comic strip Lue Bradefer uses the same method to transport his hero's vehicle through time: by spinning on itself like a top, the "Chronosphere" escapes from present appearances.

In another game, the first child places his nose against the wall, turning his back on his partners, who all stay a certain distance away on a starting line. He hits the wall three times before turning suddenly on his partners. During this short

period of time, the others should advance toward him; then, when he turns around, they assume an immobile position. Anyone caught moving by the first child is eliminated from the game. Whoever succeeds in reaching the wall without being detected by the first child has won, and replaces him. As in the scansion ofthe game ofhandball, projected always higher and faster against the earth, a wall, or toward a partner, it seems that it is less the object that is being thrown and caught with agility than its image, projected, enlarged, deformed or erased by the player turning on himself. We may think here ofthe "leap" ofMandelbrot's skein ofthread4-the numerical result (from zero to many dimensions), depending on the rapports of distance between the observed and the observing, or what separates them.

When asked how, at an advanced age, he was able to keep his youthful look, Lartigue answered simply that he knew how to give orders to his body. The disenchantment, the loss of power over himself that obliged him to have recourse to technical prostheses (photography, easel painting, rapid vehicles...) have not entirely abolished the demands on his own body that he made as a child.

But we now know that unequal aging of cellular tissues begins at a veryearly age, and the crystalline lens ofthe eye is affected precociously since breadth of accommodation declines after the age of eight until about fifty, when we become far-sighted. The nerve cells of the brain start their irreversible decline at age five. The child is already becoming a handicapped oldster; his recourse to prostheses here is really

meant to be an artificial addition destined to replace or complete failing organs.The game then becomes the basic art; the contract on the aleatory is only the formulation of an essential question on the relative perception of the moving; the pursuit ofform is only a technical pursuit oftime. The game is neither naive nor funny. Begun by all from birth, it's the very austerity ofits tools, its rules and its representations that paradoxically unleashes in the child pleasure and even passion: a few lines or signs traced ephemerally, a few characteristic numbers, some rocks or bones...

The basis of the game is the separation of the two extreme poles of the seen and the unseen, which is why its construction, the unanimity that pushes children to spontaneous acceptance of its rules, brings us back to the picnoleptic experience.

The more progress we make in the already ancient study ofthe petit mal, the more it appears to be widespread, diverse, and badly understood. In spite of lengthy polemics as to its kinship with epilepsy, with its uncertain diagnoses and with the crisis passing unperceived by those present as well as by the subject himself, it remains completely unknown by nearlyeveryone, and to the question: who is picnoleptic?we could possibly respond today: who isn't, or hasn't been?

So-defined as a mass phenomenon, picnolepsy comes to complement in the waking order the notion of paradoxical sleep (rapid-eye-movement sleep), which corresponds to the phase of deepest dreaming. So our conscious life-which we already believe would be inconceivable without dreams-is

just as difficult to imagine without a state of paradoxical waking (rapid waking).

"Film what doesn't exist," the Anglo-Saxon special effects masters still say, which is basically inexact: what they are filming certainly does exist, in one manner or another. It's the speed at which they film that doesn't exist, and is the pure invention of the cinematographic motor. About these special effects-or "trick photography," hardly an academic phrase-Meli{�s liked to joke, "The trick, intelligently applied, today allows us to make visible the supernatural, the imaginary, even the impossible."

The great producers of the epoch recognized that by wresting cinema from the realism of "outdoor subjects" that would quickly have bored audiences, Melies had actually made it possible for film to remain realistic.s

As Melies himself remarked, "I must say, to my great regret, the cheapest tricks have the greatest impact." It's useful to remember how he went about inventing that cheap trick which, according to him, the public found so appealing:

"One day, when 1 was prosaically filming the Place de l'Opera, an obstruction of the apparatus that 1 was using produced an unexpected effect. 1 had to stop a minute to free the film and started up the machine again. During this time passersby, omnibuses, cars, had all changed places, of course. When 1 later projected the reattached film, 1 suddenly saw the Madeleine-Bastille Bus changed into a hearse, and Pilul Vll ,/25

men changed into women. The trick-by-substitution, soon called the stop trick, had been invented, and two days later I performed the first metamorphosis ofmen into women."

Technical chance had created the desynchronizing circumstances ofthe picnoleptic crisis and Meli(�s-delegating to the motor the power of breaking the methodical series of filmed instants-acted like a child, regluing sequences and so suppressing all apparent breaks in duration. Only here, the "black out" was so long that the effect ofreality was radically modified.

"Successive images representing the various positions that a living being traveling at a certain speed has occupied in space over a series ofinstants."

This definition ofchronophotography given by its inventor, the engineer Etienne Jules Marey,6 is very close also to that "game against the wall" we've just been talking of. Furthermore, if Marey wants to explore movement, making of fugacity a "spectacle" is far from his intentions.Around 1880 the debate centered on the inability of the eye to capture the body-in-motion, everyone was wondering about the veracity of chronophotography, its scientific value-the very reality it conveys insofar as it makes the "unseen" visible, that is to say, a world-without-memory and ofunstable dimensions.

Ifwe notice Marey's subject ofchoice we perceive that he leans toward the observation ofwhat seemed to him precisely the most uncontrollable thing formally: the flight of free

flying birds, or of insects, the dynamics offluids... but also the amplitude of movement and abnormal expressions in nervous maladies, epilepsy, for instance (subjects of photographic studies around 1876 at the hospital ofSalpetriere).

Later, the illusionism of Melies will no more aim to mislead us than the methodical rigor of a Claude Bernard disciple: one maintains a Cartesian discourse, "the senses mislead us," and the other invites us to recognize that "our illusions don't mislead us in always lying to us!" (La Fontaine). What science attempts to illuminate, "the nonseen ofthe lost moments," becomes with Melies the very basis of the production of appearance, of his invention, what he shows of reality is what reacts continually to the absences of the reality which has passed.

It's their "in-between state" that makes these forms visible that he qualifies as "impossible, supernatural, marvelous." But Emile Cohrs earliest moving comic strips show even more clearly to what extent we are eager to perceive malleable forms, to introduce a perpetual anamorphosis in cinematic metamorphosis.

The pursuit offorms is only a pursuit oftime, but ifthere are no stable forms, there are no forms at all. We might think that the domain of forms is similar to that of writing: If you see a deaf-mute expressing himself you notice that his mimicry, his actions are already drawings and you immediately think of the passage to writing as it is still taught in Japan, for example, with gestures performed by the professor for students to capture calligraphically. Likewise, if you're

talking about cinematic anamorphosis, you might think of its pure representation which would be the shadow projected by the staff of the sundial. The passing of time is indicated, according to the season of the year, not only by the position but also by the invisible movement ofthe form ofthe shadow ofthe staffor ofthe triangle on the surface ofthe dial (longer, shorter, wider, etc.).

Furthermore, the hands ofthe clock will always produce a modification ofthe position, as invisible for the average eye as planetary movements; however, as in cinema, the anamorphosis properly speaking disappears in the motor of the clock, until this ensemble is in turn erased by the electronic display of hours and dates on the black screen where the luminous emission substitutes entirely for the original effect ofthe shadow.

Emphasizingmotion more thanform is,first ofall, to change the roles ofday and light. Here also Marey is informative.With him light is no longer the sun's "lighting up the stable masses of assembled volumes whose shadows alone are in movement." Marey gives light instead another role; he makes it leading lady in the chrono-photographic universe: if he observes the movement of a liquid it's due to the artifice of shiny pastilles in suspension; for animal movement he uses little metallicized strips etc.

With him the effect of the real becomes that of the readiness ofa luminous emission; what is given to see is due to the phenomena of acceleration and deceleration in every respect identifiable with intensities of light. He treats light like a shadow of time.

We notice generally a spontaneous disappearance of picnoleptic crises at the end of childhood (infans, the nonspeaker). Absence ceases therefore to have a prime effect on consciousness when adult life begins (we may be reminded here ofthe importance oftheendocrinal factor in the domain ofepilepsy and also ofthe particular role ofthe pituitary and hypothalamus in sexual activity and sleep...).

Along with organic aging, this is also the loss of savoirfaire and juvenile capacities, the desynchronization effect stops being mastered and enacted, as with theyoungLartigue playing with time, or using it as a system of invention and personal protection-photosensitive subjects show great interest for the causes inducing their crises and frequently resort to absence mechanisms as a defense-reaction against unpleasant demands or trains ofthought (Pond).

The relation to dimensions changes drastically. What happens has nothing to do with metaphors ofthe "images of time" style; it is something like what Rilke's phrase meant in the most literal sense: "What happens is so far ahead ofwhat we think, of our intentions, that we can never catch up with it and never really know its true appearance." One of the most widespread problems of puberty is the adolescent's discovery ofhis own body as strange and estranged, a discovery felt as a mutilation, a reason to despair.

It's the age of"bad habits" (drugs, masturbation, alcohol), which are merely efforts at reconciliation with yourself, attenuated adaptations ofthe vanished epileptic process.This is also the age, nowadays, of the intemperate utilization of

technical prostheses of mediatization (radio, motorcycle, photo, hi-fl, etc.). The settled man seems to forget entirely the child he was and believed eternal (E.A. Poe); he's entered, in fact, as Rilke suggests, another kind of absence to the world. "The luxuriance and illusion of instant paradises, based on roads, cities, the sword,"? to which theJudeo-Christian tradition opposes a new departure toward a "desert of uncertainties" (Abraham), lost times, green paradises where only adults who have become children again may enter.

In Ecciesiastes what is the essential is lacking; with the New Testament the lack is the essential; the Beatitudes speak of a poverty of spirit that somehow could be opposed to the wealth ofmoments, to this hypothetical conscious hoarding proposed by Bachelard, to this fear "ofmini-max equilibrium by exhaustion ofthe stakes based on a knowledge (information, ifyou will), whose treasure (which is language's treasure of possible enunciations) becomes inexhaustible" (J.F. Lyotard). Images of the vigilant society, striking equal hours for everyone.

At the Arch ofTriumph Award, a journalist wittily asked of the president: "Is betting part of leisure?" The president was careful not to answer this question that pretended to assimilate lottery techniques to this culture ofleisure proposed for more than a century to the working population as inestimable recompense for its efforts. Replying would be to admit that progress has pushed our hyper-anticipatory and predictive society toward a simple culture ofchance, a contract on the aleatory.

In new Roman circuses at Las Vegas, they bet on any and everything, in the game rooms and even in the hospitalseven on death. A nurse working at the Sunrise Hospital invented, for the amusement of the personnel, a "casino of death" where you bet on the moment the patient will die. Soon everyone started playing: doctors, nurses, cleaning ladies; from a few dollars the stakes went up to hundreds... soon there weren't enough people dying. What follows is easy enough to imagine.

The basic recreation ofchildhood, lowered to the level of trivial excitement, remains nonetheless a derivative of picnoleptic auto-induction, the dissimulation of one or several elements of a totality in relation to an adversary who is one only because of differences in perception dependent on time and appearances that escape under our very eyes, artificially creating this inexplicable exaltation where "each believes he is finding his real nature in a truth which he would be the only one to know."

Furthermore, number-games, like lotto or the lottery, with their disproportionate winnings, connote disobedience to society's laws, exemption from taxes, immediate redressment ofpoverty...s

"No power doubles or precedes the will; the will itself is this power," wrote Vladimir Jankelevitch. If you admit that picnolepsy is a phenomenon that effects the conscious duration of everyone-beyond Good and Evil, a petit mal, as it used to be called-the meditation on Time would not only be the preliminary job delegated to the metaphysician;

relieved today by a few omnipotent technocrats, anyone would now live a duration which would be his own and no one else's, by way ofwhat you could call the uncertain conformation of his intermediate times, and the picnoleptic onset would be something that could make us think ofhuman liberty, in the sense that it would be a latitude given to each man to invent his own relations to time and therefore a kind ofwill and power for minds, none ofwhich, "mysteriously, can think ofhimselfas being any lower than anyone else" (E.A. Poe).

With Bergsonian chrono-tropisms you could already imagine "different rhythms ofduration that, slower or faster, would measure the degree oftension or of relaxation of consciousness and would establish their respective places in the series of beings." Bur here the very notion of rhythm implies a certain automatism, a symmetrical return ofweak or strong terms superimposed on the experienced time of the subject. With the irregularity of the epileptic space, defined by surprise and an unpredictable variation of frequencies, it's no longer a matter of tension or attention, but of suspension pure and simple (byacceleration), disappearance andeffective reappearance of the real, departure from duration.

To Descartes' sentence: "the mind is a thing that thinks" (that is, in stable and commonly visible forms), Bergson retorted: "The mind is a thing that lasts..." The paradoxical state ofwaking would finally make them both agree: it's our duration that thinks, the first product ofconsciousness would be its own speed in its distance of time, speed would be the causal idea, the idea before the idea.9

Even if we talk about the solitude of power as an established fact, no one really thinks of questioning this autism conferred inevitably by the function of command-which means that, as Balzac has it, "all power will be secret or will not be, since all visible strength is threatened."

This reflection radically opposes the extreme caducity of the world as we perceive it to the creative force of the unseen, the power of absence to that of the dream itself.Any man that seeks power isolates himself and tends naturally to exclude himself from the dimensions of the others, all techniques meant to unleash forces are techniques of disappearance {the epileptic constitution of the great conquerors, Alexander, Caesar, Hannibal, etc., is well known}.

In his Citizen Kane, Orson Welles ignores the Freudian elements that American directors ordinarily used and designates the mysterious sled Rosebud as the apparently trivial motive for the rise to power of his hero, the key and the conclusion of the fate of this pitiless man, a little vehicle able to delight its young passenger while sliding at top speed through a snowscape.1O After this fictive biography ofWilliam Randolph Hearst calling out to Rosebud for help in his agony, there comes Howard Hughes' real destiny.The life of this billionaire seems made of two distinct parts, first a public existence, and then-from age 47 and from then on for 24 years-a hidden life.The first part of Hughes' life could pass for a programming of behavior by dream and desire: he wanted to become the richest, the greatest aviator, the most important producer in the world, and he succeeded everywhere

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

seems hardly worth while creating a special sub-region for their reception, particularly as no genus is peculiar. At the same time the fact is instructive as illustrating the close connexion of the northern districts of the two regions, a connexion which was no doubt more intimate in recent geological times than it is now.

The circumpolar genera are as follows. The list decisively sets forth the superior hardiness of the fresh-water as compared with the land genera:—

Valvata 1 sp. Bithynia 1 „ Vitrina 1 „ Hyalinia 4 „ Helix 2 „ Patula 2 „ Pupa 3 „ Cionella 1 „ Succinea 1 „ Limnaea 7 „ Planorbis 5 „ Aplecta 1 „ Physa 1 „ Anodonta 1 „ Unio 1 „ Pisidium 1 „

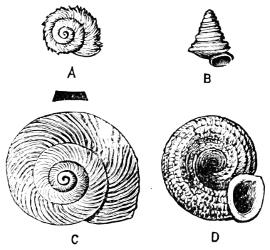

Great Britain.—There are in all about 130 species—83 land, 46 fresh-water; Limnaea involuta (mountain tarn near Killarney) appears to be the only peculiar species. There are 11 Hyalinia, 5 Arion, and 25 Helix, the latter belonging principally to the sub-genera Xerophila, Tachea, Trichia, and Fruticicola. Three Testacella are probably not indigenous, but are now so well established as to reckon in the total. Of the four Clausilia two reach Ireland and one Scotland; two do not occur north of the Forth. There are only two land operculates, one of which (Cyclostoma elegans) occurs in Ireland but not in Scotland, while the other (Acicula lineata) reaches the southern counties of Scotland. Several species, e.g. Helix pomatia, H. obvoluta, H. revelata, H. cartusiana, H. pisana, Buliminus montanus, are restricted to the more southern or western counties; Geomalacus maculosus is confined to a district in south-western Ireland.

The Pleistocene beds of East Anglia contain a number of species now extinct in these islands, whose occurrence appears to indicate a warmer climate than the present. Such are Helix ruderata, H. fruticum, H. incarnata, Clausilia pumila, Unio littoralis, Hydrobia marginata, and Corbicula fluminalis.

Scandinavian Peninsula.—From Norway 121 species in all are recorded, and 148 from Sweden. The milder climate of Norway allows many species to reach a considerably higher latitude than in Sweden, thus in Sweden Limax maximus only reaches 62°, but in Norway 66° 50´. Similarly Arion hortensis and Balea perversa only reach 63° and 61° respectively in Sweden, but in Norway are found as far north as 69° and 67° 50´. Clausilia is represented by 9 species in southern Norway; one of these is found north of the Arctic circle. There are 4 Pupa, 9 Vertigo, and 11 Hyalinia, but Helix dwindles to 14, 9 of which occur north of the Arctic circle. No land operculates are found; Cyclostoma elegans, however, occurs in Jutland and Zealand, which practically form a part of this district.

Iceland.—Eleven species, all Scandinavian, occur. These are Arion 2, Limax 1, Helix 2 (arbustorum L. and hortensis Müll., the latter being found only on the warmer southern coast), Limnaea 1, Planorbis 1, Pisidium 4.

France.—The northern, central, and eastern districts belong to this sub-region, while the southern and western, in which an entirely new element occurs and many northern forms disappear, belong to the Mediterranean. Thus, for instance, Helix pomatia L., H. incarnata Müll., H. fruticum Müll., H. cantiana Mont., H. strigella Drap., H. rufescens Penn., H. plebeia Drap., are not found in southern France. No detailed enumeration of species is at present possible, the efforts of a large number of the leading French authorities being directed to indiscriminate species-making rather than to the careful comparison of allied forms. Perhaps the principal difference between the Mollusca of northern France and those of our own islands is the occurrence of two species of Pomatias. In the more elevated districts of eastern France (the Vosges, Jura, western Alps), a certain number of species occur which are confined to the high grounds of south central Europe. Among these are Helix holoserica Stud., H.

personata Lam., H. bidens Chem., H. depilata Drap., H. cobresiana Alt., H. alpina Faure.

The Pleistocene deposits of the valley of the Somme tell the same tale as those of eastern England, containing as they do species and even genera whose northern range is now much more limited. The Eocene fossils from the Paris beds show most remarkable relationships to genera now existing in the West Indies and Central America. Others again indicate affinities with India. Thus we find Ceres, Megalomastoma, and Tudora by the side of Leptopoma, Faunus, and Paludomus.

Germany.—The Mollusca of the plains of northern Germany are few and not striking, and exhibit little difference from those of our own islands. In the mountainous districts of the south and southeast, a number of new forms occur, amongst which are 3 species of Daudebardia, a remarkable carnivorous form, with the general appearance of a Vitrina; 24 of Clausilia, many Pupa, several Buliminus, 3 of the Campylaea group of Helix, stragglers from the Italo-Dalmatian fauna, and 1 of Zonites proper. Our familiar Helix aspersa is entirely absent from Germany There are only 4 land operculates—Pomatias 2, Acicula 1, Cyclostoma 1, all of which occur exclusively in the south. Bithynella and Vitrella, two minute forms of fresh-water operculates akin to Hydrobia, occur throughout the district.

F��. 193. A, Daudebardia brevipes Fér.: sh, shell; p.o, pulmonary orifice. (After Pfeiffer.) B, shell of D. rufa Pfr., S. Germany

Northern Russia and Siberia.—This vast tract extends from eastern Germany to the Amoor district. It is exceedingly poor in Mollusca, and is chiefly characterised by the gradual disappearance, as we proceed eastward, of European species. There are a few characteristic Siberian Mollusca, closely allied to European forms, and in the extreme east a new element is introduced in the appearance of types which indicate Chinese affinities. The whole district may be regarded as bounded to the south by a line drawn from Lemberg to Moscow, and thence to Perm; passing south of the Ural mountains, it includes the whole basins of the rivers Obi, Yenesei, and Lena, coinciding with the vast mountain ranges which terminate to the north the table-land of central Asia, at the eastern extremity of which it dips sharply southwards, so as to include the Amoor basin and Corea.

All the larger Helices are wanting, and no land operculates occur. Helix arbustorum L., H. nemoralis Müll., H. lapicida L., H. aculeata Müll., and Hyalinia nitidula Drap., do not appear to occur east of the Baltic; Arion fuscus Müll., Helix strigella Drap., Buliminus obscurus Müll., Clausilia laminata Mont., C. bidentata Bttg., C. plicatula Drap., Viviparus fasciatus Müll., and Neritina fluviatilis L., do not pass the Urals.

In the Obi district (West Siberia) a further batch of European species find their easterly limit. Among these are Helix hispida L., Bithynia tentaculata L., Vivipara vivipara L., Pisidium amnicum Müll., and Unio tumidus Retz. A few distinctly Siberian species now appear, e.g. Ancylus sibiricus Gerst., Valvata sibirica Midd., and Vitrina rugulosa Koch.

The following are among the European species which reach eastern Siberia: Hyalinia nitida Müll., Succinea oblonga Drap., Planorbis vortex L., spirorbis L., marginatus Drap., rotundatus Poir., fontanus Light., Valvata piscinalis Müll., Bithynia ventricosa Leach, and Anodonta variabilis Drap. Here first occur such characteristic species as Physa sibirica West., P. aenigma West., Helix pauper Gld., H. Stuxbergi West., H. Nordenskiöldi West., Planorbis borealis Lov., Valvata aliena West., Cyclas nitida Cless., and C. levinodis West. In the Amoor district a decided Chinese element makes its

appearance in a few hardy forms which have penetrated northward, e.g. Philomycus bilineatus Bens., and a few each of the Fruticicola (Chinese) and Acusta groups of Helix. Out of 53 species, however, enumerated from this district, as many as 33, belonging to 18 genera, occur also in Great Britain.

Lake Baikal.—The Mollusca of Lake Baikal exhibit distinct characteristics of their own, which seem to indicate the longcontinued existence of the lake in its present condition. Several entirely peculiar genera occur, which are specialised forms of Hydrobia, e.g. Baikalia, Liobaikalia, Gerstfeldtia, Dybowskia, and Maackia; Benedictia alone extends to the basin of the Amoor. Choanomphalus, another peculiar and ultra-dextral (p. 250) genus belonging to the Limnaeidae, appears to be related to the West American Carinifex.

(2) The Mediterranean Sub-region is divided into four provinces: (a) The Mediterranean province proper; (b) the Pontic; (c) the Caucasian; and (d) the Atlantidean province.

(a) The Mediterranean province proper is best considered by further subdividing it, with Fischer and others, into separate districts, each of which has certain peculiar characteristics.

(i) The Hispano-Algerian district includes the greater part of the Iberian peninsula, the Balearic Islands, and northern Africa from Morocco to Tunis. The extreme western parts of these districts, including West Morocco, Portugal, Asturias, and south-west France, under the influence of the moist climate caused by the Atlantic, show some peculiar features which, in the view of some, are sufficient to justify their separation from the rest of the Hispano-Algerian portion. Among these is a marked development of the slugs, Testacella, Arion, and Geomalacus, the latter of which occurs even in southwestern Ireland.

F�� 194 A, Parmacella Valenciensii W and B × ⅔ (After Moquin-Tandon ) A´, shell of the same, natural size

Spain.—The principal features are the development of the Macularia, Iberus, and Gonostoma groups of Helix, and the occurrence of the remarkable slug Parmacella, which is found in many other parts of the sub-region, and extends eastward as far as Afghanistan. Clausilia has but few species, mostly in the north. There are four species of land operculates, one of which is referred to a genus (Tudora) now living only in the West Indies, but which occurs in the Eocene fossils of the Paris basin. In the south there are several species of Melanopsis and Neritina.

The States of Northern Africa have a thoroughly Mediterranean fauna, whose facies on the whole shows rather more affinity to Spain than to Sicily The Helices of Morocco and Algeria belong to the same groups as those of southern Spain. Many are of a dead white colour, the better to resist the scorching effect of the sun. Ferussacia is abundant, Geomalacus and Parmacella are represented by a single species each, and there is one Clausilia. According to Kobelt, [366] the original land connexion between southern Spain and Morocco must have been much more extensive than is usually assumed, and probably reached at least to the meridian of Oran and Cartagena. The Mollusca of Oran and Cartagena are, according to him, much more closely related than those of Oran and Tangier, or those of Cartagena and Gibraltar, but at Cartagena some species, which are characteristic of the Mediterranean coasts from Syria westward, disappear, are absent from the rest of Spain and from Morocco, but reappear on the south-western coasts of France.

These species may possibly have pushed along that arm of the sea which, when the Straits of Gibraltar were closed as far as the latitude of Oran and Cartagena, united in comparatively recent times the Bay of Biscay with the Gulf of Lions.

The following genera, which do not occur in Spain, have probably spread into northern Africa as far as Algeria, via Sicily and Tunis, namely, Glandina (1 sp.), Daudebardia (1 sp.), Pomatias (2 sp.). Tunis shows strong traces of Sicilian influence, and Kobelt found a colony of snails, of Sicilian affinities, as far west as Tetuan.

The Sahara.—The Algerian Sahara contains, in many places, a sub-fossil Molluscan fauna which appears to show that the district has, in quite recent times, undergone a gradual desiccation. The species are mainly fresh-water, including Melania, Melanopsis, and Corbicula, with here and there valves of Cardium edule, and indicate, on the whole, an affinity with recent Egyptian, rather than North African species. It is probable that a vast series of étangs, or brackish-water lakes, once stretched along this region, and were ultimately connected with the sea somewhere between Tunis and Egypt.

F��. 195. Characteristic shells of S. France: A, Helix (Macularia) niciensis Fér ; B, Leucochroa candidissima Drap

(ii) Southern France.—The southern portion of France bordering on the Mediterranean contains many species, especially of Helix, which do not occur in the centre and north. Amongst these are—

Leucochroa candidissima Drap

Hyalinia olivetorum Gmel

Zonites algirus L

Helix rangiana Desh

„ serpentina Fér

„ niciensis Fér

„ splendida Drap.

„ vermiculata Müll.

„ melanostoma Drap.

„ aperta Born.

„ ciliata Ven.

„ explanata Müll.

„ apicina Lam.

„ cespitum Drap.

„ Terverii Mich.

„ pyramidata Drap.

„ trochoides Poir

Ferussacia folliculus Gron

Rumina decollata L

Pupa megacheilos C and J

Several species of fresh-water Hydrobia (Bithynella) occur. The district, on the whole, unites certain characteristics derived from northern Italy with those of eastern Spain.

(iii) The Italo-Dalmatian district includes Italy and the neighbouring islands (Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Malta), and the regions at the head and north-eastern shores of the Adriatic (Carinthia, Carniola, Croatia, and Dalmatia), the line which separates these latter districts from the fauna of southern Austria, Bosnia, and Servia being very difficult to define.

F�� 196 Helix (Pomatia) aperta L , S France, showing epiphragm

F�� 197 Helix (Campylaea) zonata Stud , Piedmont

F�� 198 Helix (Iberus) strigata Müll , Florence

Italy, with the neighbouring islands, has a rich molluscan fauna. In the sub-Alpine districts of northern Italy the prominent Helix groups are Campylaea, Pomatia, and Anchistoma, which in the south are generally replaced by Iberus, which here attains its maximum

development. Large Hyalinia are abundant in the north, and Pomatias and Clausilia are frequent all along the Apennines. Sicily has about 250 species, half of which are peculiar. Helices of the Iberus type abound, but Campylaea is reduced to two species. Many peculiar forms of Clausilia occur, especially a latticed type of great beauty. Ferussacia and Pupa are well represented, and there are one each of Glandina and Daudebardia.

Dalmatia and the adjacent districts are chiefly remarkable for the rich development of Clausilia, which here attains its maximum (nearly 100 species). The Campylaea section of Helix is represented by its handsomest forms, many of which are studded with short hairs. Here too is the headquarters of Zonites proper, which stretches westward as far as Provence, and eastward to Asia Minor; and also of the single European Glandina, which has a similar eastward range, but spreads westward through Italy and Sicily to Algeria, not occurring in southern France. The land operculates are chiefly represented by Pomatias, and among the fresh-water operculates are a Melania and a Lithoglyphus, the latter having probably spread from the basin of the Danube.

F�� 199 A, Clausilia crassicosta Ben , Sicily; B, Clausilia macarana Zieg , Dalmatia; B´, clausilium of same

(iv) The Egypto-Syrian district extends along the south-eastern shores of the Mediterranean from Tripoli to North Syria, and

eastward to the Euphrates valley Lower Egypt alone belongs to this portion, the fauna of Upper Egypt being of an entirely tropical character, and belonging to the Ethiopian Region.

Lower Egypt.—The Mollusca of Lower Egypt stand in the unique position of belonging, half to the Palaearctic, and half to the Ethiopian Region. The land Mollusca are of a distinctly Mediterranean type, while the fresh-water, directly connected as they are by the great highway of the Nile with regions much farther south, contain a large admixture of thoroughly tropical genera (Ampullaria, Lanistes, Melania, Cleopatra, Corbicula, Cyrena, Iridina, Spatha, Mutela). The Helices, which are not numerous, are rather a mixture of circum-Mediterranean species than of a specially distinctive character. H. desertorum, however, belonging to the group Eremophila, is characteristic. There is a single Parmacella, but the physical features of the country are unfavourable to the occurrence of such genera as Clausilia, Pupa, Hyalinia, and the land operculates.

Syria.—The Mollusca, especially in the more mountainous regions of the north, are much more varied and numerous than those of Egypt. Clausilia is again fairly plentiful, and the Helicidae are represented by some striking forms of the sections Levantina, Pomatia, and Nummulina. Leucochroa has several curious types with a constricted aperture, and the Agnatha are represented by Libania, a peculiar form of Daudebardia. A prominent feature is the occurrence of a number of large white Buliminus of the Petraeus section (Fig. 200). Land operculates appear to be absent, but Melanopsis and Neritina are abundant. The Dead Sea contains no Mollusca, but Lake Tiberias has a rich fauna, including the abovementioned genera, with a Corbicula and several Unio.

F��. 200. A, Buliminus (Petraeus) labrosus Oliv., Beyrout; B, Buliminus (Chondrula) septemdentatus

Roth , Palestine

Upper Mesopotamia appears to possess a mixture of Syrian and Caucasian forms, including a Parmacella. Lower Mesopotamia has an exceedingly poor land fauna, but is comparatively rich in freshwater species, the growing eastern character of which is shown by the occurrence of several Corbicula and Pseudodon, and of a Neritina of a distinctly Indian type.

(b) The Pontic province extends from Western Austria to the Sea of Azof, and includes Austria, Hungary, Roumania, the Balkan peninsula (so far as it does not form part of the Mediterranean subregion), the islands of the Greek Archipelago, southern Russia and the Crimea, and Asia Minor. It thus practically corresponds to the whole Danube basin, together with the lands bordering on the Black Sea, except at the extreme east, which belongs to the Caucasian sub-region. Fischer separates off Greece, Asia Minor (except the northern coast-line), and the intervening islands, with Crete and Cyprus, as constituting a portion (Hellado-Anatolic) of the Mediterranean sub-region proper. These districts, however, appear to possess scarcely sufficient individuality to warrant their separate consideration.

A prominent characteristic of the Pontic Mollusca is the great abundance of Clausilia and Buliminus. In the islands east and west

of Greece Clausilia forms a large proportion of the fauna, each island, however small, possessing its own peculiar forms. The Helices belong principally to the groups Campylaea (which is very abundant in Austro-Hungary), Pomatia (Greece and Asia Minor), and Anchistoma. Macularia is comparatively scarce, but is represented in Greece by one very large form (Codringtonii Gray). Zonites proper has its metropolis in this sub-region, and the Danube basin contains one or two species of Melania and Lithoglyphus. Buliminus is abundant throughout the sub-region, in the sub-genera Zebrina, Napaeus, Mastus, and Chondrula Several striking forms of Zebrina (Ena) are peculiar to the Crimea.

(c) The Caucasian Province.—The limits of this province can hardly be exactly defined at present. It appears, however, to include the whole line of the Caucasus range, Armenia, and North Persia.

The land Mollusca are abundant and interesting. Among the carnivorous genera are four species of Daudebardia, a Glandina, and three peculiar forms of naked slug, Pseudomilax, Trigonochlamys, and Selenochlamys. There is a single Parmacella, the same species as the Mesopotamian, and a good many forms of Limax. Vitrina and Hyalinia are well represented, and the predominant groups of Helix are Euloto, Cartusiana, Xerophila, and Fruticocampylaea, the last being peculiar. Clausilia and Pupa are rich in species, together with Buliminus of the Chondrula type. One Clausilia of the Phaedusa section, together with a Macrochlamys (Transcaspian only), a Corbicula, and a Cyclotus, show marked traces of Asiatic affinity. There is one species each of Acicula and Cyclostoma, and one of Pomatias.

The Caspian Sea, like Lakes Baikal and Tanganyika, is distinguished by the possession of several remarkable and peculiar genera. The sea itself, the waters of which are brackish, is 80 feet below the level of the Black Sea, and is no doubt a relict of what formed, in earlier times, a very much larger expanse of water. Marine deposits containing fauna now characteristic of the Caspian, have been found as far north as the Samara bend of the Volga. It is probable, therefore, that in Post-pliocene times an arm of the AraloCaspian Sea penetrated northward up the present basin of the Volga

to at least 54° N. The Kazan depression of the Volga (55° N.) also contains characteristic Caspian fossils.[367] According to Brusina, [368] the Caspian fauna, as a whole, is closely related to the Tertiary fauna of southern Europe.

Twenty-six species of univalve Mollusca, the majority being modified forms of Hydrobia, have been described from the Caspian, namely, Micromelania (6), Caspia (7), Clessinia (3), Nematurella (3), Lithoglyphus (1), Planorbis (1), Zagrabica (1), Hydrobia (2), Neritina (2). The bivalves are mostly modified forms of Cardium (Didacna, Adacna, Monodacna), which also occur in estuaries along the north of the Black Sea. A form of Cardium edule itself occurs, and numberless varieties of the same species are found in a semi-fossil condition in the dry or half dry lake-beds, which are so abundant throughout the Aral district.

(d) The Atlantidean province consists of the four groups of islands, the Madeiran group, the Canaries, the Azores, and the Cape Verdes.

The Madeiran group contains between 140 and 150 species of Mollusca which may be regarded as indigenous, the great majority of which are peculiar. Only 11 species are common to Madeira and to the Azores, and about the same number, in spite of their much greater proximity, to Madeira and the Canaries. No less than 74 species, or almost exactly one-half, belong to Helix, and 9 to Patula. A considerable number of the Helices are not only specifically but generically peculiar, the genera bearing close relationship to those occurring in the Mediterranean region. As a rule they are small in size, but often of singular beauty of ornamentation. Various forms of Pupa are exceedingly abundant (28 sp.), as is also Ferussacia (12 sp.). There are also 3 Clausilia (which genus occurs on this group alone), and 3 Vitrina (a genus which occurs on all the groups). The land operculates are represented solely by 4 Craspedopoma, which is common to all the groups except the Cape Verdes.

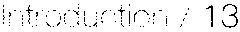

F��. 201. Characteristic land Mollusca from the Madeira group: A, Helix (Irus) laciniosa Lowe, Madeira; B, Helix (Hystricella) turricula Lowe, Porto Santo; C, Helix (Iberus) Wollastoni Lowe, Porto Santo; D, Helix (Coronaria) delphinuloides Lowe, Madeira

The Canaries have about 160 species, only about a dozen of which are not peculiar. As many as 75 of these belong to Helix (the sub-genera being very much the same as in the Madeiran group), and 11 to Patula. There is 1 species of Parmacella (which occurs in this group alone), and 6 of Vitrina, of considerable size. A remarkable slug (Plectrophorus) was described from Teneriffe by Férussac many years ago, but it has never been rediscovered, and is probably mythical, or wrongly assigned. Buliminus (Napaeus) has as many as 28 species, all but one being peculiar, and Ferussacia 7. Cyclostoma has two indigenous species, which, with one Hydrocena and one Craspedopoma, make up the operculate land fauna.

The Azores are comparatively poor in Mollusca, having only 52 species, nearly two-thirds of which are peculiar. Helix has 15 species, Patula 4, and Pupa 8. Ferussacia, so abundant in Madeira and the Canaries, is entirely absent, its place being taken by Napaeus (7 sp.), which is curiously absent from Madeira, but richly

represented in the Canaries. There are 7 Vitrina, while the land operculates consist of one each of Craspedopoma and Hydrocena. A singular slug (Plutonia), with an ancyliform internal shell, is said to occur. The group was long believed to possess no fresh-water Mollusca, but two species (one each of Pisidium and Physa) have recently been discovered.

The Cape Verdes, owing to the extreme dryness of their climate, are poor in land Mollusca. There are 11 Helix, nearly all of which belong to the group Leptaxis, which is common to Madeira and the Canaries. Ferussacia is absent, Buliminus is represented by a single species, and there are no land operculates. Ethiopian influence, however, as might be expected from the situation of the group, is seen in the occurrence of an Ennea, a Melania, and an Isidora.

It will be noticed how little countenance the molluscan fauna of these island groups gives to any theory of an Atlantis, any theory which regards the islands as the remains of a western continent now sunk beneath the ocean. Had ‘Atlantis’ ever existed, we should have expected to find a considerable proportion of the Mollusca common to all the groups, and perhaps to Europe as well, and there would apparently be no reason why a genus which occurred in one group should not occur in all. As a fact, we find the species extremely localised throughout, and genera occur and fail to occur in a particular group without any obvious reason. All the evidence tends to show that the islands are purely oceanic, and have been colonised from the western coasts of the Mediterranean, i.e. from the direction of the prevailing currents and winds.

(3) Central-Asiatic Sub-region.—The countries included in this vast sub-region are Turkestan, Songaria, Afghanistan, including the Pamirs, Western Thibet, and probably Mongolia. Kashmir belongs to the Indian fauna. At present the whole district is very imperfectly known; indeed, it is only at a few points that anything like a thorough investigation of the fauna has been made. It is therefore almost premature to pronounce any decided opinion upon the Mollusca, but all the evidence at present to hand tends to show that they belong to the Palaearctic and not to the Oriental system. This is especially the case with regard to the fresh-water Mollusca, many of which are

specifically identical with those occurring in our own islands. A slight admixture of such widely distributed types as Corbicula and Melania occurs, but it is not sufficient to disturb the general European facies of the whole. It is possible that eventually the whole district may be regarded as a sub-region combining certain characteristics of the eastern portions of the Mediterranean basin with an extension of the septentrional element, due to higher elevation and more rigorous climate. The principal features in the land Mollusca appear to be the occurrence of a number of Buliminus of the Napaeus group, a few Parmacella (Afghanistan being the limit of the genus eastward), Clausilia, Pupa, Limax, and Helix, with several stray species of Macrochlamys.

B. The Oriental or Palaeotropical Region

This region includes all Asia to the south of the boundary of the Palaearctic region, that is to say, India, with Ceylon, Burmah, Siam, and the whole of the Malay Peninsula, China proper, with Hainan and Formosa, and Japan south of Yesso. It also includes the Andamans and Nicobars, and the whole of Malaysia, with the Philippines, as far eastward as, and including Celebes with the Xulla Is., and the string of islands south of the Banda Sea up to the Ké Is. The Moluccas, in their two groups, are intermediate between the Oriental and Australasian regions.

In this vast extent of land two distinct centres of influence are prominent—the Indian and the Chinese. Each is of marked individuality, but they differ in this essential point, that while the Chinese element is decidedly restricted in area, being, in fact, more or less confined to China itself and the adjacent islands, the Indian element, on the other hand, extends far beyond continental Asia, and embraces all the Malay islands to their farthest eastward extent, until it becomes overpowered by the Papuan and Australian fauna. Upper Burmah, with Siam, forms a sort of meeting-point of the two elements, which here intermingle in such a way that no very definite line of demarcation can be drawn between them.

Thus we have—

Oriental Region 1. Indo-Malay Sub-Region (a) Indian Province

(b) Siamese Province

(c) Malay Province

(d) Philippine Province

2 Chinese Sub-Region (a) Chinese Province

(b) Japanese Province

The Indo-Malay fauna spreads eastward from its metropolis, but has practically no westward extension, or only such as may be traced on the eastern coasts of Africa and the off-lying islands. There appears to exist no other case in the world where the metropolis of a fauna is so plainly indicated, or where it lies, not near the centre, but at one of the ends of the whole area of distribution.

Comparing the two sub-regions, the Chinese is distinguished by the great predominance of Helix, while in the Indo-Malay sub-region Nanina and the related genera are in the ascendancy. In India itself there are only 6 genera of true Helicidae, poorly represented in point of numbers; in China there are at least three times this amount, most of them abundant in species. The Indo-Malay sub-region, on the other hand, is the metropolis of the Naninidae, which abound both in genera and species. In the Chinese sub-region Clausilia attains a development almost rivalling that of S.E. Europe, while in India there are scarcely a dozen species. A marked feature of the Indo-Malay sub-region is the singular group of tubed land operculates (Opisthoporus, Pterocyclus, etc.). In China the group is only represented by stragglers of Indian derivation, while the land operculate fauna, as a whole, is distinctly inferior to the Indian. Another characteristic group of the Indo-Malay region is Amphidromus, with its gaudily painted and often sinistral shell; the genus is entirely absent from China proper and Japan, where its place is taken by various small forms of the Buliminus group. Freshwater Mollusca, especially the bivalves and operculates, are far more abundant in the Chinese sub-region than in the Indo-Malay.

(1) The Indo-Malay Sub-region.—(a) The Indian Province proper includes the peninsula of Hindostan, together with Assam and Upper and Lower Burmah. To the east and extreme north-east, the boundaries of the province are ill-defined, and the fauna gradually assimilates with the Siamese on the one hand and the Chinese on

the other Roughly speaking, the line of demarcation follows the mountain ranges which separate Burmese from Chinese territory, but the debatable ground is of wide extent, and Yunnan, the first Chinese province over the border, has many species common with Upper Burmah.

The gigantic ranges of mountains which bound the sub-region to the north-west and north limit the extension of the Indian fauna in those directions in a most decisive manner. There is no quarter of the world, even in W. America, where a mountain chain has equal effect in barring back a fauna. In the north of Kashmir, where the great forests end, there is a most complete change of environment as the traveller gains the summit of the watershed; but Kashmir itself distinctly belongs to the Indian and not the Palaearctic system. The great desert to the south of the Punjab is equally effective as a barrier towards the west.

The Mollusca of India proper include a very large number of interesting and remarkable genera. India is the metropolis of the great family of the Naninidae, or snails with a caudal mucus-pore, which are here represented by no less than 14 genera and over 200 species. The genera Macrochlamys, Sitala, Kaliella, Ariophanta, Girasia, Austenia, and Durgella are at their maximum. Helix is scarcely represented, containing only about 30 inconspicuous species (leaving Ceylon out of account). Buliminus is abundant, especially in the north. The Stenogyridae are represented by Glessula, which is exceedingly abundant in India, but has only a few straggling representatives in the rest of the Oriental region. Among the Pupidae is the remarkable form Boysia, with its twisted upturned mouth, while Lithotis is a peculiar form allied to Succinea, to which group also probably belongs Camptonyx, a limpet-like form with a very small spire, peculiar to the Kattiawar peninsula. Camptoceras, an extraordinarily elongated sinistral shell, with a loosely coiled spire, is peculiar to the N.W. Provinces.

Among the fresh-water pulmonates is an Ampullarina, a genus only known elsewhere from the Fiji Is. and E. Australia. Cremnoconchus is a form of Littorina, peculiar to the W. Ghâts, which has habituated itself to a terrestrial life on moist rocks many

miles from the sea. The fresh-water operculates include the peculiar forms Mainwaringia, from the mouth of the Ganges (intermediate between Melania and Paludomus), Stomatodon, Larina, Fossarulus, Tricula, and others. The bivalves are neither numerous nor remarkable; Velorita, a genus of the Cyrenidae, is peculiar.

F��. 202. Characteristic Indian Mollusca: A, Hypselostoma tubiferum Blanf.; B, Camptoceras terebra Bens.; C, Camptonyx Theobaldi Bens.

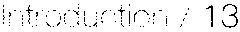

F��. 203. Streptaxis Perroteti Pfr., Nilghiri Hills: A, adult; A´, young form