Handbook of Parenting Volume 4 Social Conditions and Applied Parenting

Third Edition Marc

H. Bornstein

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parenting-volume-4-social-conditions-an d-applied-parenting-third-edition-marc-h-bornstein/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Handbook of Parenting Volume I Children and Parenting Third Edition Marc H. Bornstein (Editor)

https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parenting-volume-ichildren-and-parenting-third-edition-marc-h-bornstein-editor/

Handbook of Parenting Volume 5 The Practice of Parenting Third Edition Marc H. Bornstein (Editor)

https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parentingvolume-5-the-practice-of-parenting-third-edition-marc-hbornstein-editor/

Handbook of Parenting Volume 2 Biology and Ecology of Parenting Third Edition Marc H. Bornstein (Editor)

https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parentingvolume-2-biology-and-ecology-of-parenting-third-edition-marc-hbornstein-editor/

Handbook of Parenting Volume 3 Being and Becoming a Parent Third Edition Marc H. Bornstein (Editor)

https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parentingvolume-3-being-and-becoming-a-parent-third-edition-marc-hbornstein-editor/

Advances in Psychology and Law Volume 4 Brian H.

Bornstein

https://textbookfull.com/product/advances-in-psychology-and-lawvolume-4-brian-h-bornstein/

Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan Matthew R. Sanders

https://textbookfull.com/product/handbook-of-parenting-and-childdevelopment-across-the-lifespan-matthew-r-sanders/

Parenting

and Children s Resilience in Military Families 1st Edition Abigail H. Gewirtz

https://textbookfull.com/product/parenting-and-children-sresilience-in-military-families-1st-edition-abigail-h-gewirtz/

Advances

in Psychology and Law Volume 2 1st Edition

Brian H. Bornstein

https://textbookfull.com/product/advances-in-psychology-and-lawvolume-2-1st-edition-brian-h-bornstein/

Weird Parenting Wins Bathtub Dining Family Screams and Other Hacks from the Parenting Trenches Hillary Frank

https://textbookfull.com/product/weird-parenting-wins-bathtubdining-family-screams-and-other-hacks-from-the-parentingtrenches-hillary-frank/

HANDBOOK OF PARENTING

This highly anticipated third edition of the Handbook of Parenting brings together an array of field-leading experts who have worked in different ways toward understanding the many diverse aspects of parenting. Contributors to the Handbook look to the most recent research and thinking to shed light on topics every parent, professional, and policymaker wonders about. Parenting is a perennially “hot” topic. After all, everyone who has ever lived has been parented, and the vast majority of people become parents themselves. No wonder bookstores house shelves of “how-to” parenting books, and magazine racks in pharmacies and airports overflow with periodicals that feature parenting advice. However, almost none of these is evidence-based. The Handbook of Parenting is. Period. Each chapter has been written to be read and absorbed in a single sitting, and includes historical considerations of the topic, a discussion of central issues and theory, a review of classical and modern research, and forecasts of future directions of theory and research. Together, the five volumes in the Handbook cover Children and Parenting, the Biology and Ecology of Parenting, Being and Becoming a Parent, Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, and the Practice of Parenting.

Volume 4, Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, describes socially defined groups of parents and social conditions that promote variation in parenting. The chapters in Part I, on Social and Cultural Conditions of Parenting, start with a relational developmental systems perspective on parenting and move to considerations of ethnic and minority parenting among Latino and Latin Americans, African Americans, Asians and Asian Americans, Indigenous parents, and immigrant parents. The section concludes with considerations of disabilities, employment, and poverty on parenting. Parents are ordinarily the most consistent and caring people in children’s lives. However, parenting does not always go right or well. Information, education, and support programs can remedy potential ills. The chapters in Part II, on Applied Issues in Parenting, begin with how parenting is measured and follow with examinations of maternal deprivation, attachment, and acceptance/ rejection in parenting. Serious challenges to parenting—some common, such as stress and depression, and some less common, such as substance abuse, psychopathology, maltreatment, and incarceration—are addressed as are parenting interventions intended to redress these trials.

Marc H. Bornstein holds a BA from Columbia College, MS and PhD degrees from Yale University, and honorary doctorates from the University of Padua and University of Trento. Bornstein is President of the Society for Research in Child Development and has held faculty positions at Princeton University and New York University as well as academic appointments in Munich, London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Bamenda, Seoul, Trento, Santiago, Bristol, and Oxford. Bornstein is author of several children’s books, videos, and puzzles in The Child’s World and Baby Explorer series, Editor Emeritus of Child Development and founding Editor of Parenting: Science and Practice, and consultant for governments, foundations, universities, publishers, scientific journals, the media, and UNICEF. He has published widely in experimental, methodological, comparative, developmental, and cultural science as well as neuroscience, pediatrics, and aesthetics.

HANDBOOK OF PARENTING

Volume 4: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting

Third Edition

Edited by Marc H. Bornstein

Third edition published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Taylor & Francis

The right of Marc H. Bornstein to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyr ight, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

First edition published by Laurence Erlbaum Associates 1995

Second edition published by Taylor & Francis 2002

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book

ISBN: 978-1-138-22873-3 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-22874-0 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-39899-5 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo by Apex CoVantage, LLC

For Marian and Harold Sackrowitz

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

Previous editions of the Handbook of Parenting have been called the “who’s who of the what’s what.”

This third edition of the Handbook appears at a time that is momentous in the history of parenting. The family generally, and parenting specifically, are today in a greater state of flux, question, and redefinition than perhaps ever before. We are witnessing the emergence of striking permutations on the theme of parenting: blended families, lesbian and gay parents, teen versus fifties first-time moms and dads, genetic versus social parents. One cannot but be awed on the biological front by technology that now renders postmenopausal women capable of childbearing and with the possibility of parents designing their babies. Similarly, on the sociological front, single parenthood is a modern-day fact of life, adult child dependency is on the rise, and even in the face of rising institutional demands to take increasing responsibility for their offspring, parents are ever less certain of their roles and responsibilities. The Handbook of Parenting is concerned with all these facets of parenting . and more.

Most people become parents, and everyone who ever lived has had parents, still parenting remains a mystifying subject. Who is ultimately responsible for parenting? Does parenting come naturally, or must parenting be learned? How do parents conceive of parenting? Of childhood? What does it mean to parent a preterm baby, twins, or a child on the autistic spectrum? To be an older parent, or one who is divorced, disabled, or drug abusing? What do theories (psychoanalysis, personality theory, attachment, and behavior genetics, for example) contribute to our understanding of parenting? What are the goals parents have for themselves? For their children? What functions do parents’ cognitions serve? What are the aims of parents’ practices? What accounts for parents believing or behaving in similar ways? Why do so many attitudes and actions of parents differ so? How do children influence their parents? How do personality, knowledge, and worldview affect parenting? How do social class, culture, environment, and history shape parenthood? How can parents effectively relate to childcare, schools, and their children’s pediatricians?

These are many of the questions addressed in this third edition of the Handbook of Parenting for this is an evidenced-based volume set on how to parent as much as it is one on what being a parent is all about

Put succinctly, parents create people. They are entrusted with preparing their offspring for the physical, psychosocial, and economic conditions in which their children eventually will fare and hopefully will flourish. Amidst the many influences on each next generation, parents are the “final common pathway” to children’s development and stature, adjustment and success. Human social inquiry—antedating even Athenian interest in Spartan childrearing practices—has always, as a matter of course, included reports of parenting. Freud opined that childrearing is one of three “impossible

professions”—the other two being governing nations and psychoanalysis. One encounters as many views as the number of people one asks about the relative merits of being an at-home or a working mother, about what mix of daycare, family care, or parent care is best for a child, about whether good parenting reflects intuition or experience.

The Handbook of Parenting concerns itself with different types of parents—mothers and fathers, single, adolescent, and adoptive parents; with basic characteristics of parenting knowledge, beliefs, and expectations about parenting—as well as the practice of parenting; with forces that shape parenting—employment, social class, culture, environment, and history; with problems faced by parents—handicap, mar ital difficulties, drug addiction; and with practical concerns of parenting— how to promote children’s health, foster social adjustment and cognitive competence, and interact with educational, legal, and religious institutions. Contributors to the Handbook of Parenting have worked in different ways toward understanding all these diverse aspects of parenting, and all look to the most recent research and thinking in the field to shed light on many topics every parent, professional, and policymaker wonders about.

Parenthood is a job whose primary object of attention and action is the child. But parenting also has consequences for parents. Parenthood is giving and responsibility, and parenting has its own intrinsic pleasures, privileges, and profits as well as frustrations, fears, and failures. Parenthood can enhance psychological development, self-confidence, and sense of well-being, and parenthood also affords opportunities to confront new challenges and to test and display diverse competencies. Parents can derive considerable and continuing pleasure in their relationships and activities with their children. But parenting is also fraught with small and large stresses and disappointments. The transition to parenthood is daunting, and the onrush of new stages of parenthood is relentless. In the final analysis, however, parents receive a great deal “in kind” for the hard work of parenting—they can be recipients of unconditional love, they can gain skills, and they can even pretend to immortality. This third edition of the Handbook of Parenting reveals the many positives that accompany parenting and offers resolutions for its many challenges.

The Handbook of Parenting encompasses the broad themes of who are parents, whom parents parent, the scope of parenting and its many effects, the determinants of parenting, and the nature, structure, and meaning of parenthood for parents. The third edition of the Handbook of Parenting is divided into five volumes, each with two parts:

CHILDREN

AND PARENTING is Volume 1 of the Handbook. Parenthood is, perhaps first and foremost, a functional status in the life cycle: Parents issue as well as protect, nurture, and teach their progeny even if human development is too subtle and dynamic to admit that parental caregiving alone determines the developmental course and outcome of ontogeny. Volume 1 of the Handbook of Parenting begins with chapters concerned with how children influence parenting. Notable are their more obvious characteristics, like child age or developmental stage; but more subtle ones, like child gender, physical state, temperament, mental ability, and other individual differences factors, are also instrumental. The chapters in Part I, on Parenting Across the Lifespan, discuss the unique rewards and special demands of parenting children of different ages and stages—infants, toddlers, youngsters in middle childhood, and adolescents— as well as the modern notion of parent-child relationships in emerging adulthood and adulthood and old age. The chapters in Part II, on Parenting Children of Varying Status, discuss common issues associated with parenting children of different genders and temperaments as well as unique situations of parenting adopted and foster children and children with a variety of special needs, such as those with extreme talent, born preterm, who are socially withdrawn or aggressive, or who fall on the autistic spectrum, manifest intellectual disabilities, or suffer a chronic health condition.

BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY OF PARENTING is Volume 2 of the Handbook. For parenting to be understood as a whole, biological and ecological determinants of parenting need to be brought into the picture. Volume 2 of the Handbook relates parenting to its biological roots and sets parenting in its ecological framework. Some aspects of parenting are influenced by the organic make-up of human beings, and the chapters in Part I, on the Biology of Parenting, examine the evolution of parenting, the psychobiological determinants of parenting in nonhumans, and primate parenting and then the genetic, prenatal, neuroendocrinological, and neurobiological bases of human parenting. A deep understanding of what it means to parent also depends on the ecologies in which parenting takes place. Beyond the nuclear family, parents are embedded in, influence, and are themselves affected by larger social systems. The chapters in Part II, on the Ecology of Parenting, examine the ancient and modern histories of parenting as well as epidemiology, neighborhoods, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, culture, and environment to provide an overarching relational developmental contextual systems perspective on parenting.

BEING AND BECOMING A PARENT is Volume 3 of the Handbook. A large cast of character s is responsible for parenting, each has her or his own customs and agenda, and the psychological characteristics and social interests of those individuals are revealing of what parenting is. Chapters in Part I, on The Parent, show just how rich and multifaceted is the constellation of children’s caregivers. Considered first are family systems and then successively mothers and fathers, coparenting and gatekeeping between parents, adolescent parenting, grandparenting, and single parenthood, divorced and remarried parenting, lesbian and gay parents, and finally sibling caregivers and nonparental caregiving. Parenting also draws on transient and enduring physical, personality, and intellectual characteristics of the individual. The chapters in Part II, on Becoming and Being a Parent, consider the intergenerational transmission of parenting, parenting and contemporary reproductive technologies, the transition to parenthood, and stages of parental development, and then chapters turn to parents’ well-being, emotions, self-efficacy, cognitions, attributions, as well as socialization, personality in parenting, and psychoanalytic theory. These features of parents serve many functions: They generate and shape parental practices, mediate the effectiveness of parenting, and help to organize parenting.

SOCIAL CONDITIONS AND APPLIED PARENTING is Volume 4 of the Handbook. Parenting is not uniform across communities, groups, or cultures; rather parenting is subject to wide variation. Volume 4 of the Handbook describes socially defined groups of parents and social conditions that promote variation in parenting. The chapters in Part I, on Social and Cultural Conditions of Parenting, start with a relational developmental systems perspective on parenting and move to considerations of ethnic and minority parenting among Latino and Latin Americans, African Americans, Asians and Asian Americans, Indigenous parents, and immigrant parents. The section concludes with the roles of employment and of poverty on parenting. Parents are ordinarily the most consistent and caring people in children’s lives. However, parenting does not always go right or well. Information, education, and support programs can remedy potential ills. The chapters in Part II, on Applied Issues in Parenting, begin with how parenting is measured and follow with examinations of maternal deprivation, attachment, and acceptance/rejection in parenting. Serious challenges to parenting—some common, such as stress, depression, and disability, and some less common, such as substance abuse, psychopathology, maltreatment, and incarceration—are addressed, as are parenting interventions intended to redress these trials.

THE PRACTICE OF PARENTING is Volume 5 of the Handbook. Parents meet the biological, physical, and health requirements of children. Parents interact with children socially.

Parents stimulate children to engage and understand the environment and to enter the world of learning. Parents provision, organize, and arrange their children’s home and local environments and the media to which children are exposed. Parents also manage child development vis-à-vis childcare, school, the circles of medicine and law, as well as other social institutions through their active citizenship. Volume 5 of the Handbook addresses the nuts-and-bolts of parenting as well as the promotion of positive parenting practices. The chapters in Part I, on Practical Parenting, review the ethics of parenting, parenting and the development of children’s self-regulation, discipline, prosocial and moral development, and resilience as well as children’s language, play, cognitive, and academic achievement and children’s peer relationships. Many caregiving principles and practices have direct effects on children. Parents indirectly influence children as well, for example, through relations they have with their local or larger communities. The chapters in Part II, on Parents and Social Institutions, explore parents and their children’s childcare, activities, media, schools, and health care and examine relations between parenthood and the law, public policy, and religion and spirituality.

Each chapter in the third edition of the Handbook of Parenting addresses a different but central topic in parenting; each is rooted in current thinking and theory as well as classical and modern research on a topic; each is written to be read and absorbed in a single sitting. Each chapter in this new Handbook adheres to a standard organization, including an introduction to the chapter as a whole, followed by historical considerations of the topic, a discussion of central issues and theory, a review of classical and modern research, forecasts of future directions of theory and research, and a set of evidence-based conclusions. Of course, each chapter considers contr ibutors’ own convictions and findings, but contributions to this third edition of the Handbook of Parenting attempt to present all major points of view and central lines of inquiry and interpret them broadly. The Handbook of Parenting is intended to be both comprehensive and state-of-the-art. To assert that parenting is complex is to understate the obvious. As the expanded scope of this third edition of the Handbook of Parenting also amply attests, parenting is naturally and intensely interdisciplinary.

The Handbook of Parenting is concerned principally with the nature and scope of parenting per se and secondarily with child outcomes of parenting. Beyond an impressive range of information, readers will find passim typologies of parenting (e.g., authoritar ian-autocratic, indulgent-permissive, indifferent-uninvolved, authoritative-reciprocal), theories of parenting (e.g., ecolog ical, psychoanalytic, behavior genetic, ethological, behavioral, sociobiological), conditions of parenting (e.g., gender, culture, content), recurrent themes in parenting studies (e.g., attachment, transaction, systems), and even aphorisms (e.g., “A child should have strict discipline in order to develop a fine, strong character,” “The child is father to the man”).

Each chapter in the Handbook of Parenting lays out the meanings and implications of a contribution and a perspective on parenting. Once upon a time, parenting was a seemingly simple thing: Mothers mothered. Fathers fathered. Today, parenting has many motives, many meanings, and many manifestations. Contemporary parenting is viewed as immensely time consuming and effortful. The perfect mother or father or family is a figment of false cultural memory. Modern society recognizes “subdivisions” of the call: genetic mother, gestational mother, biological mother, birth mother, social mother. For some, the individual sacrifices that mark parenting arise for the sole and selfish purpose of passing one’s genes on to succeeding generations. For others, a second child may be conceived to save the life of a first child. A multitude of f actors influences the unrelenting advance of events and decisions that surround parenting—biopsychosocial, dyadic, contextual, historical. Recognizing this complexity is important to informing people’s thinking about parenting, especially informationhungry parents themselves. This third edition of the Handbook of Parenting explores all these motives, meanings, and manifestations of parenting.

Each day, more than three-quarters of a million adults around the world experience the rewards and challenges, as well as the joys and heartaches, of becoming parents. The human race succeeds because of parenting. From the start, parenting is a “24/7” job. Parenting formally begins before pregnancy and can continue throughout the life-span: Practically speaking for most, once a parent, always a parent. Parenting is a subject about which people hold strong opinions and about which too little solid information or considered reflection exists. Parenting has never come with a Handbook until now

Marc H. Bornstein

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Marc H. Bornstein holds a BA from Columbia College, MS and PhD degrees from Yale University, and honorar y doctorates from the University of Padua and University of Trento. Bornstein was a J. S. Guggenheim Foundation Fellow, and he received a Research Career Development Award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. He also received the C. S. Ford Cross-Cultural Research Award from the Human Relations Area Files, the B. R. McCandless Young Scientist Award and the G. Stanley Hall Award from the American Psychological Association, a United States PHS Superior Service Award and an Award of Merit from the National Institutes of Health, two Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowships, four Awards for Excellence from the American Mensa Education & Research Foundation, the Arnold Gesell Prize from the Theodor Hellbrügge Foundation, the Distinguished Scientist Award from the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, and both the Distinguished International Contributions to Child Development Award and the Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Child Development Award from the Society for Research in Child Development. Bornstein is President of the Society for Research in Child Development and a past member of the SRCD Governing Council and Executive Committee of the International Congress of Infancy Studies.

Bornstein has held faculty positions at Princeton University and New York University as well as academic appointments as Visiting Scientist at the Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie in Munich; Visiting Fellow at University College London; Professeur Invité at the Laboratoire de Psychologie Expérimentale in the Université René Descartes in Paris; Child Clinical Fellow at the Institute for Behavior Therapy in New York; Visiting Professor at the University of Tokyo; Professeur Invité at the Laboratoire de Psychologie du Développement et de l’Éducation de l’Enfant in the Sorbonne in Paris; Visiting Fellow of the British Psychological Society; Visiting Scientist at the Human Development Resource Centre in Bamenda, Cameroon; Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Psychology in Seoul National University in Seoul, South Korea; Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Cognitive Science in the University of Trento, Italy; Profesor Visitante at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago, Chile; Institute for Advanced Studies Benjamin Meaker Visiting Professor, University of Bristol; Jacobs Foundation Scholar-in-Residence, Marbach, Germany; Honorary Fellow, Department of Psychiatry, Oxford University; Adjunct Academic Member of the Council of the Department of Cognitive Sciences, University of Trento, Italy; and International Research Fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

Bornstein is coauthor of The Architecture of the Child Mind: g, Fs, and the Hierarchical Model of Intelligence, Gender in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, Development in Infancy (5 editions), Development: Infancy through Adolescence, Lifespan Development, Genitorialità: Fattori Biologici E Culturali Dell’essere Genitori, and Perceiving Similarity and Comprehending Metaphor. He is general editor of The Crosscurrents in Contemporary Psychology Series, including Psychological Development from Infancy, Comparative Methods in Psychology, Psychology and Its Allied Disciplines (Vols. I–III), Sensitive Periods in Development, Interaction in Human Development, Cultural Approaches to Parenting, Child Development and Behavioral Pediatrics, and Well-Being: Positive Development Across the Life Course, and general editor of the Monographs in Parenting series, including his own Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development and Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships. He edited Maternal Responsiveness: Characteristics and Consequences, the Handbook of Parenting (Vols. I–V, 3 editions), and the Handbook of Cultural Developmental Science (Parts 1 and 2), and is Editor-in-Chief of the SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development He also coedited Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook (7 editions), Stability and Continuity in Mental Development, Contemporary Constructions of the Child, Early Child Development in the French Tradition, The Role of Play in the Development of Thought, Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships, Immigrant Families in Contemporary Society, The Developing Infant Mind: Origins of the Social Brain, and Ecological Settings and Processes in Developmental Systems (Volume 4 of the Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science). He is author of several children’s books, videos, and puzzles in The Child’s World and Baby Explorer series. Bornstein is Editor Emeritus of Child Development and founding Editor of Parenting: Science and Practice. He has administered both federal and foundation grants, sits on the editorial boards of several professional journals, is a member of scholarly societies in a variety of disciplines, and consults for governments, foundations, universities, publishers, scientific journals, the media, and UNICEF. He has published widely in experimental, methodological, comparative, developmental, and cultural science as well as neuroscience, pediatrics, and aesthetics. Bornstein was named to the Top 20 Authors for Productivity in Developmental Science by the American Educational Research Association.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Tangeria R. Adams is a clinical psychology PhD student at the University of Rochester. She obtained her BS in Psychology from Brooklyn College. Tangeria is a recipient of the Provost’s Transition to PhD Fellowship from the University of Rochester. Her research interests include depression in underserved populations, the implementation of culturally appropriate interventions, and transactional processes between maternal depression and child characteristics.

Yvonne Bohr is a clinical psychologist, Associate Professor of Psychology, and the former Director of the LaMarsh Centre for Child and Youth Research in the Faculty of Health at York University in Toronto. Bohr received her PhD at the University of Toronto. She has written on culture and parenting and co-authored articles relating to Indigenous parenting. She currently directs a participatory community mental health research program with Inuit youth in the territory of Nunavut.

Marc H. Bornstein is President of the Society for Research in Child Development. He holds a BA from Columbia College, MS and PhD deg rees from Yale University, and honorary doctorates from the University of Padua and University of Trento. He has held faculty positions at Princeton University and New York University as well as visiting academic appointments in Munich, London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Bamenda (Cameroon), Seoul, Trento, Santiago (Chile), Bristol, Oxford, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (London). He is Editor Emeritus of Child Development and founding Editor of Parenting: Science and Practice. He has administered both Federal and Foundation grants, sits on the editorial boards of several professional journals, is a member of scholarly societies in a variety of disciplines, and consults for governments, foundations, universities, publishers, the media, and UNICEF. Bornstein has published widely in experimental, methodological, comparative, developmental, and cultural science as well as neuroscience, pediatrics, and aesthetics.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn is Virginia and Leonard Marx Professor of Child Development at Columbia University’s Teachers College and College of Physicians and Surgeons. She is also Director of the National Center of Children and Families. Brooks-Gunn was educated at Connecticut College, Harvard University, and University of Pennsylvania. A developmental psychologist, she has written books on gender roles, the acquisition of self, adolescents in later life, family poverty, and neighborhood contexts. Brooks-Gunn is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Education.

Laurie Chassin is Regents Professor of Psychology at Arizona State University. Chassin was educated at Brown University and Columbia University Teachers College. She is an associate editor of Journal of Abnormal Psychology and a field editor of Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. She is a past associate editor of Nicotine and Tobacco Research and Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Her research focuses on longitudinal studies of the life course and intergenerational transmission of substance use disorders.

Shayna S. Coburn is Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences and licensed psychologist at Children’s National Health System. Coburn earned her PhD at Arizona State University. Her areas of interest include coping, resilience, and interpersonal communication in families experiencing stressors such as chronic illness.

Linda R. Cote is Professor of Psychology at Marymount University. Cote was educated at the Catholic University of America and Clark University and is affiliated with the Child and Family Research Section of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Her research interests center on parenting and infant development in immigrant families. She is co-editor of Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships

Keith A. Crnic is Foundation Professor of Psychology at Arizona State University, where he was past chair. Crnic was educated at the University of Southern California and the University of Washington in Seattle. He previously held academic positions in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington and in the Department of Psychology at Pennsylvania State University, where he also served as department head and as director of the Child Study Center. His scholarly efforts have focused on high risk contexts and stress in families of young children and parent-child relationships.

E. Mark Cummings is the William J. Shaw Family Professor of Psychology at the University of Notre Dame and co-founder of the William J. Shaw Center for Children and Families. Cummings was educated at Johns Hopkins University and UCLA. His research focuses on relations between family processes and children’s normal development and risk for the development of psychopathology. He has been associate editor of Child Development. Cummings is lead author of Children and Marital Conflict, Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process, Marital Conflict and Children, and Political Violence, Armed Conflict and Youth Adjustment

Danielle Dallaire is Associate Professor of the Department of Psychology at the College of William & Mary. She holds a PhD in Developmental Psychology from Temple University. She researches the effects of parental incarceration on young children’s social and emotional development.

Cindy DeCoste is Research Associate and the Project Director for the Moms ‘n’ Kids Program in the Yale University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry. DeCoste was educated at Southern Connecticut State University and Saint Francis Xavier University in Canada. She has been involved with the development, implementation, and evaluation of attachment-based and psychoeducational parenting interventions for mothers receiving substance use and mental health services.

Hailey E. Dias is Research Coordinator with the Moms ‘n’ Kids Program in the Yale University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and the APT Foundation of Greater New Haven. Dias was educated at Quinnipiac University, where her research focused on evidence-based practice and empirically supported treatments in clinical psychology.

Theodore Dix is Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. He received his PhD from Northwestern University and has held prior faculty appointments at SUNY–Stony Brook and Duke University. He is a fellow of both the American Psychological Association and the Association for Psychological Science.

Greg J. Duncan is Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Irvine. Duncan received his PhD in Economics and has worked at the University of Michigan and Northwestern University. Duncan’s work has focused on the effects of increasing income inequality on schools and children’s life chances. Duncan was president of the Society for Research in Child Development, is an member of the National Academy of Sciences, and received SRCD’s Award for Distinguished Contributions to Public Policy and Practice in Child Development.

Linda C. Halgunseth is Associate Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Connecticut. She was educated at the University of Texas at Austin and University of Missouri. She has been research associate in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at Pennsylvania State University, Research Coordinator at the National Association for the Education of Young Children, and Director for Youth and Family Programs at Centro Latino de Salúd, Educación, y Cultura. Halgunseth serves as chair of the Latino Caucus of the Society for Research in Child Development. Her research focuses on parenting and children’s development in Latino and African American families.

Wen-Jui Han is Professor in the Silver School of Social Work at New York University. Han holds a BA in Sociology from National Taiwan University, an MSW from UCLA and MS from Columbia University, and a PhD in Social Work from Columbia University. Her research interests are in the area of childcare, parental employment, child and adolescent academic and health well-being, immigrants, and public policies. Han co-founded the NYU-ECNU Institute for Social Development at NYU Shanghai.

Cecily R. Hardaway is Assistant Professor of African American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. She holds a BS in Human Development and Family Studies from Pennsylvania State University and a PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Hardaway’s program of research centers on understanding how socioeconomic status influences child development and family processes.

Gwen K. Healey is Executive and Scientific Director of the Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre in Iqaluit, Nunavut, and Assistant Professor of Human Sciences at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine. Healey was educated at Queen’s University, University of Calgary, and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. Healey’s interests center on Inuit health, family perspectives, and ways knowing, and she is an instructor and lead evaluator for the Inunnguiniq Childrearing Program in Nunavut, Canada. Healey co-founded the Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre.

Nina Philipsen Hetzner is Social Science Research Analyst with Business Strategy Consultants working within the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation at the Administration for Children and Families in Health and Human Services. Philipsen Hetzner holds a BA in Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin, an MS in Child Development from Purdue University, and a PhD in Developmental Psychology from Columbia University. Her research focuses on early care and education, primarily the Head Start and Early Head Start programs. She was a Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, a research consultant with the New York City Department of

Education on the development of the First Step NYC Leadership Institute, and a graduate fellow at the National Center for Children and Families.

Lacey J. Hilliard is Research Assistant Professor at the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development at Tufts University. She completed her PhD in developmental psychology at Pennsylvania State University. She is an associate editor of Applied Developmental Science

Andrea M. Hussong is Professor of Psychology and Neurosciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Director of the Center for Developmental Science. Hussong completed her training at Indiana University and Arizona State University. She is on the editorial board for Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use, and Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Her research focuses on developmental trajectories leading to health risk behavior and well-being, particularly in at-risk families.

Rosanne M. Jocson is Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Ateneo de Manila University. She received a PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of Michigan. Jocson’s research examines pathways through which contextual risk factors associated with poverty, such as neighborhood conditions, housing contexts, and community violence exposure, influence family and child development. She also studies protective factors that promote resilience in parents and children living in low-resource contexts. She is involved in a project that expands the development, implementation, and evaluation of a parenting intervention program that aims to prevent violence against children in low-income Filipino families. Her work has been published in developmental and community psychology journals, including the International Journal of Behavioral Development, American Journal of Community Psychology, Psychology of Violence, and Youth & Society.

Richard M. Lerner is the Bergstrom Chair in Applied Developmental Science and the Director of the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development at Tufts University. He has a PhD in Developmental Psychology from the City University of New York and has authored or edited 80 books. Lerner was the founding editor of the Journal of Research on Adolescence and of Applied Developmental Science. A past fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, he is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Psychological Association, and the Association for Psychological Science.

Gwynnyth Llewellyn is Professor of Family and Disability Studies, and Director of the Centre for Disability Research and Policy; Head, WHO Collaborating Centre on Health Workforce Development in Rehabilitation and Long Term Care; and Co-director, NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Disability and Health at the University of Sydney, Australia. Llewellyn was educated at the University of Sydney and the University of New England. She is past dean, Faculty of Health Sciences University of Sydney, and chair, International Association for Scientific Study of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Special Interest Research Group on Parents and Parenting with Intellectual Disabilities. She has edited the Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, and Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability. Llewellyn is senior editor of Parents With Intellectual Disabilities: Past, Present and Futures

Katherine A. Magnuson is a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor of Social Work at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She also serves as the associate director of the Institute for Research on Poverty. She completed her PhD in Human Development and Social Policy. She is a former associate editor of Developmental Psychology and Child Development.

Vonnie C. McLoyd is the Ewart A. C. Thomas Colleg iate Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor, and was previously a Professor of Psychology at Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She received a PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of Michigan. McLoyd is past president of the Society for Research on Adolescence and has been associate editor of Child Development and American Psychologist. Her research focuses on parenting and neighborhood factors as mediators linking economic stress and African American children’s socioemotional adjustment, and processes that buffer adverse effects of economic stress on parenting and children’s socioemotional adjustment. She has coedited several volumes: Economic Stress: Effects on Family Life and Child Development; Studying Minority Adolescents: Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Issues; African American Family Life: Ecological and Cultural Diversity; APA Handbook of Multicultural Psychology: Theory and Research (Vol 1) and Applications and Training (Vol 2)

Anat Moed is Assistant Professor at Bar Ilan University’s School of Education. She was educated at Ben Gurion University and the University of Texas at Austin. She studies emotion, parenting, and their role in children’s development.

Nicole M. Muir is a PhD student in Forensic Psychology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada. She is a member of the Métis Nation. Muir completed her MA in Clinical Child Psychology at Simon Fraser University. Her current research focuses on Indigenous youth involved in the justice system.

Florrie Fei-Yin Ng is Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She received her BS, MA, and PhD from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Her research interests include the influence of the sociocultural context on parents’ role in children’s motivation and achievement as well as the transmission of cultural values to children through parenting.

Douglas R. Powell is Distinguished Professor of Human Development and Family Studies at Purdue University. He received his PhD from Northwestern University and previously served on the faculties of the Merrill-Palmer Institute and Wayne State University. He has directed projects focused on the development and evaluation of parenting interventions in lower-income communities, and written several books on families and early childhood programs. He is former editor of the Early Childhood Research Quarterly, chair of the Child Development and Early Education Group of the American Educational Research Association, and consulting editor of Child Development

Diane L. Putnick is a statistician with the Child and Family Research section of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Putnick received her PhD in Developmental Psychology from the George Washington University. She studies parenting and child development across cultures. Putnick serves on the editorial board of Parenting: Science and Practice and as consulting editor/advisor for Developmental Psychology and Family Process

Ronald P. Rohner is Professor Emeritus of Human Development and Family Studies and Anthropology at the University of Connecticut, Storrs. He is director of the Ronald and Nancy Rohner Center for the Study of Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection. He is also former president and now executive director of the International Society for Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection. Rohner received his PhD from Stanford University and did his undergraduate work at the University of Oregon. He served as a Senior Scientist in the Boys Town Center for the Study of Youth Development at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. Rohner is author of The

Warmth Dimension: Foundations of Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory and They Love Me, They Love Me Not: A Worldwide Study of the Effects of Parental Acceptance and Rejection

W. Andrew Rothenberg is a PhD candidate in the Clinical Psychology and Neuroscience program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill completing his predoctoral psychology residency at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. His research focuses on how parenting and family processes affect the emergence of child psychopathology across time, culture, and generations.

Michael Rutter is Professor of Developmental Psychopathology at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London. He trained in medicine at the University of Birmingham, England. He was director of the Medical Research Council Child Psychiatry Research Unit and also the Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Research Centre in London. His research interests focus on the developmental interplay between nature and nurture and on the use of natural experiments to test causal hypotheses about genetic and environmental mediation of risk in relation to normal and abnormal psychological development. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and was president of the Society for Research in Child Development and the International Society for Research into Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. His books include Maternal Deprivation Reassessed and Developing Minds: Challenges and Continuity Across the Lifespan

Matthew J. Shepherd is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Education and Social Work, the University of Auckland. He received his PhD in Clinical Psychology from the University of Auckland and his Social Work degree from Massey University. He is a registered clinical psychologist and a registered social worker. Shepherd is a member of Ngāti Tama, a Māori tribe from Taranaki, New Zealand.

Rhiannon L. Smith is Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut, Storrs. She earned her PhD at the University of Missouri. She is a research faculty affiliate of the Ronald and Nancy Rohner Center for the Study of Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection and consulting editor for the Journal of Research on Adolescence. She studies friendships and social-emotional adjustment in childhood and adolescence. Her research interests include social perspective-taking, empathetic distress, gender, and friendship formation across differences such as cross-ethnic friendships.

Ariel Sternberg is a PhD student in the Clinical Psychology program at Arizona State University. Her research focuses on the impact of family processes and parenting as they relate to the intergenerational transmission of substance use disorders.

Melissa L. Sturge-Apple is Associate Professor of Psychology and Dean of Graduate Studies at the University of Rochester. Sturge-Apple completed her PhD in Developmental Psychology at the University of Notre Dame. She was as a research associate at the Mt. Hope Family Center in Rochester. Her research focuses on interparental dynamics, parenting and child development, particularly within high risk and low resource contexts. She serves as an associate editor of Development and Psychopathology and the Journal of Family Psychology

Nancy E. Suchman is Associate Professor of Psychology and Director of the Moms ‘n’ Kids Program in the Yale University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and the Yale Child Study Center. Suchman was educated at Colorado State University, Syracuse University, and Cornell University. Her research has focused on the development and evaluation of attachment-based parenting interventions for mothers involved with substance abuse, mental health, and child guidance services. Suchman is the lead author of Parenting and Substance Abuse: Developmental Approaches to Intervention.

Jennifer H. Suor is a Clinical Psychology PhD student at the University of Rochester. She obtained her BA in Psychology from Vassar College. Her work examines the interplay between parenting and child temperament in associations with child executive functions.

Sheree L. Toth is Executive Director of the Mt. Hope Family Center and Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Rochester. Toth received her PhD in Clinical Psychology from Case Western Reserve University. Her research interests are broadly focused in the field of developmental psychopathology. Toth serves as associate editor of Development and Psychopathology, consulting editor of Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, and editorial board member of Child Maltreatment and Journal of Child and Family Studies

Qian Wang is Associate Professor at the Department of Psychology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China. She was educated at Peking University, China, and then received her PhD degree in Developmental Psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Her major research interests include parenting, social and personality development, and cultural influences on parental socialization and child development. She serves on the editorial board of Journal of Youth and Adolescence and Adolescent Research Review

Kelly A. Warmuth is Assistant Professor of Psychology and Director of the Family and Development Lab at Providence College. Warmuth received her BA from the University of Michigan before receiving her MA and PhD from the University of Notre Dame. Utilizing the developmental psychopathology perspective, her research focuses on marital conflict, parent-child attachment, parenting, and child and adolescent aggression.

Donald K. Warne is Professor and Chair of the Department of Public Health at North Dakota State University. He is a member of the Oglala Lakota Tribe from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and he received his MD from Stanford University and his MPH from Harvard University. Warne serves on the National Board of Trustees for the March of Dimes and as the Senior Policy Advisor to the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board.

Sandra Woodhouse is Research Psychologist at the Social, Genetic, and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London. Woodhouse gained her degree from the University of Wales, Swansea.

PART I

Social and Cultural Conditions of Parenting

1

A RELATIONAL DEVELOPMENTAL SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE ON PARENTING

Richard M. Lerner and Lacey J. Hilliard

Introduction

Parenting is both a biological and a social process (Tobach and Schneirla, 1968). Parenting subsumes a set of behaviors involved across life in the relations among organisms, who are usually conspecifics and typically members of different generations. The social interactions involved in parenting provide resources across the generational groups and function in regard to domains of survival, reproduction, nurturance, and socialization. Especially in neotenous and paedomorphic species, such as human beings (Gould, 1977; Lerner, 1984, 2018), parenting by members of an older generation of members of a younger generation afford reproductive success; learning across an extended childhood—to fit within each generation’s current and, potentially, future ecological niche; and intergenerational connectivity and interdependency. Connectivity and interdependency can extend both generations’ capacity to function successfully in new niches.

Within the younger generation, this capacity to function in new arenas accrues as a consequence of the actualization of the high level of plasticity present at relatively early portions of the ontogenies of members of the younger group (Hebb, 1949; Lerner, 1984, 2018; Schneirla, 1957; Tobach, 1981).

The actualization of the younger generation’s potential for plasticity can maintain or enhance the quality of life of the older generation. That is, because of the connectivity maintained by the older generation, members of this group are provided with the skills and resources attained, developed, or controlled by the younger generation. At this writing, the widespread availability of personal computers, the internet, email, and other electronic means of communication (e.g., cell phones) are the latest examples of such a contribution by younger generations. Often members of the older generation learn and benefit from their children’s proficiency with these new media (Hilliard, Stacey, McClain, Batanova, and Lerner, 2018).

Thus, parenting is a complex process, involving much more than a mother or father providing food, safety, and succor to an infant or child. Parenting involves bidirectional relationships between members of two (or more) generations, can extend through the respective life spans of these groups, may engage all institutions within a culture (including educational, economic, political, and social ones), and is embedded in the history of a people (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006; Ford and Lerner, 1992). Moreover, diversity is a key substantive feature of parenting (Bornstein, 2015). Diversity arises because of the temporal variation that constitutes history and the variation of culture and of its institutions that exist in different physical and designed ecological niches. In addition, there is variation within and across generations in strategies for and behaviors designed to fit with these

M. Lerner and Lacey J. Hilliard

niches. Focus on the breadth and specificity of this variation, rather than on central tendencies, is necessary to understand parenting adequately (Bornstein, 2017; Molenaar and Nesselroade, 2015; Rose, 2016).

Parenting involves multiple levels of organization that change in and through integrated, mutually interdependent or “fused” relationships occurring over both ontogenetic and historical time (Lerner, 2018; Lerner and Lerner, 1987; Tobach and Greenberg, 1984). This understanding of parenting may be usefully embedded in theories/models derived from relational developmental systems metatheory (Overton, 2015), for example, bioecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2005; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006) or developmental contextualism (Lerner, 2004,2018). In this chapter, we use models derived from relational developmental systems metatheory to discuss the integrated and dynamic relationships involved in parenting.

Accordingly, we first present an overview of this metatheory. We explain how relational developmental systems metatheory provides design criteria for developmental theories, or models of human development, that focus on the course of specific and mutual influential relations between and individual and his/her context across the life span. As such, we point to the importance of the specificity principle (Bornstein, 2017) as a means to structure theory-predicated questions about the course of the specific individual-context relations in each person’s life course. Families are foundational contexts of each person’s life course and, as such, we turn to a discussion of how models of mutually influential individual-context relations may frame the course of the specific relations a child has with his or her parents. We provide two illustrations of such relational developmental systems theories, that is, developmental contextualism (Lerner, 1979, 2004) and Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) biological model of human development. These two models converge in a set of specific implications for research and application about mutually influential child-parent relationships. These implications correspond to Bronfenbrenner’s discussion of the roles of process, person, context, and time in human development.

A Brief Overview of Relationship Developmental Systems Metatheory

A metatheory is a theory of theories. It is a conception of how to write theories. A metatheory proscribes and prescr ibes the attributes that a developmental scientist might include in theories or models of development (Lerner, 2018; Overton, 2015). Across the past four plus decades, several scholars have provided ideas contributing to the evolution of relational developmental systems metatheory (Baltes, 1997; Baltes, Lindenberger, and Staudinger, 2006; Brandtstädter, 2006; Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006; Elder, 1998; Elder, Shanahan, and Jennings, 2015; Ford and Lerner, 1992; Nesselroade, 1988; Overton, 1973, 2015; Overton and Reese, 1981; Riegel, 1975, 1976; and, even earlier, see von Bertalanffy, 1933). However, the work of Overton (2015) has been the major scholarly force integrating and extending this line of thinking.

Overton (2015) explained that relational developmental systems metatheory is linked to a process-relational paradigm; compared to a Cartesian paradigm, the process-relational paradigm focuses on process (systematic changes in the developmental system), becoming (moving from potential to actuality; a developmental process as having a past, present, and future; Whitehead, 1929/1978), holism (the meanings of entities and events derive from the context in which they are embedded), relational analysis (assessment of the mutually influential relations within the developmental system), and the use of multiple perspectives and explanatory forms (employment of ideas from multiple theory-based models of change within and of the developmental system) in understanding human development. Within the process-relational paradigm, the organism is seen as inherently active, self-creating (autopoietic), self-organizing, self-regulating (agentic), nonlinear/complex, and adaptive (Overton, 2015; see too Sokol, Hammond, Kuebli, and Sweetman, 2015).

The process-relational paradigm results in relational developmental systems metatheory, which eschews split conceptions in favor of ideas that emphasize the study and integration of different levels of organization, ranging from biology and physiology to culture and history, as a means to understand life span human development (Lerner, 2006; Overton, 2015). Accordingly, the conceptual emphasis in relational developmental systems-based theories is placed on mutually influential relations between individuals and contexts, or individual context relations. This representation of the coactions between person and setting within relational developmental systems-based models is not meant to convey a person-context interaction (which is typically represented in the developmental literature as person X context). An interaction connotes that the entities involved in the relation are separate and independent (as in a statistical interaction) and that, as such, their association involves a linear combination of discrete and separate variables. Both before and after the interaction these entities (variables) are independent and unchanged by each other. The bidirectional arrow used in the relational developmental systems conception of person context relations is intended to emphasize that the coaction of individual and context involves the entire developmental system. As such, the relations among levels of the autopoietic system, and not independent linear combinatorial attributes, are the focus in such a model. Indeed, the fusion of individual and context within the developmental system means that any portion of the system is inextricably embedded with—or embodied by, in Overton’s (2013, 2015) conceptualization—all other portions of the developmental system. Embodiment refers to the way individuals behave, experience, and live in the world by their being active agents with particular kinds of bodies; the body is integratively understood as form (a biological referent), as lived experience (a psychological referent), and as an entity in active engagement with the world (a sociocultural referent).

From Metatheory to Theory

Theoretical models of development derived from relational developmental systems metatheory depict universal functions of a living, open, self-constructing (autopoietic), self-organizing, and integrated/holistic system. In these models, the process of development involves mutually influential relations within this self-organizing system and, for ontogenetic development, between individuals and their contexts. Thus, when applied to the study of the relations between children and their parents, these relations would be represented as child parent relationships.

Because history is part of the context involved in these relations, temporality, the potential for change, is involved at all levels of organization within the relational developmental system. These changes may be stochastic or systematic, and when they are systematic they reflect plasticity. In other words, plasticity is the potential for systematic change in child parent relationships across the life span. This feature of development, when seen through the lens of a relational developmental systemsbased model, becomes a key asset in (a strength of ) child parent relationships (Lerner, Lerner, Bowers, and Geldhof, 2015; Overton, 2015). The process of individual development involves specific instances across life of individual context relations and of child parent relationships more specifically. In other words, in relational developmental systems, development happens because of specific child parent relationships across time and place (Elder et al., 2015; see too Bor nstein, 2015, 2017).

No two people develop across life with the same series of time and place relations, including monozygotic (identical) twins ( Joseph, 2015; Richardson, 2017). As a consequence, human development is fundamentally idiographic (Molenaar and Nesselroade, 2015; Rose, 2016). Therefore, within models of development framed by relational developmental systems metatheory, the individuality of all humans, the diversity of human development, is of primary substantive significance. This conception of diversity has important implications for developmental methodology and for the questions asked in developmental research.

Richard M. Lerner and Lacey J. Hilliard

The standard approach to statistical analysis in the social and behavioral sciences is not focused on change but is, instead, derived from mathematical assumptions regarding the constancy of phenomena across people and, critically, time (Molenaar, 2014). These assumptions are based on the ergodic theorems. The ergodic theorems are mathematical formulations that specify that (1) all individuals within a sample may be treated as the same (this is the assumption of homogeneity) and (2) all individuals remain the same across time, that is all time points yield the same results (this is the assumption of stationarity). These ideas lead to statistical analyzes placing prime interest on the population level. Interindividual differences, rather than intraindividual change, is the source of this population information (Molenaar, 2014).

If the concept of ergodicity is applied to the study of human development, then within-person variation across time would either be ignored or treated as error variance. In addition, any sample (group) differences would be held to be invariant across time and place. However, from a relational developmental systems-based perspective, development varies across people and across contexts, and these facts violate the ideas of ergodicity. That is, developmental processes have time-varying means, variances, and/or sequential dependencies. The structure of interindividual variation at the population level is therefore not equivalent to the structure of intraindividual variation at the level of the individual (Molenaar, 2014). Simply, developmental processes are non-ergodic. As such, differences between people in developmental trajectories (i.e., in the course of within-person changes) are important foci for research and, as well, for program and policy applications aimed at enhancing development across time and place. These implications arise because the focus in relational developmental systems metatheory is on the specificity of individual context relations. This specificity results in a belief that human development is fundamentally a matter of individual development; that is, the individual character of human development points to the importance of an idiographic approach to the study of human life. This emphasis on individuality provides a rationale for a distinct approach to diversity, one that has implications for the description, explanation, and optimization of human development.

To indicate the research implications of this approach, it is important to understand the “specificity principle” (Bornstein, 2017). This principle involves researchers asking multi-part “what” questions when conducting programmatic research exploring the function, structure, and content of development of diverse individuals (children and parents) across the life span. For instance, in seeking to understand how diverse children and parents may have a specific series of child parent relationships associated with adaptive, healthy, or positive development, researchers might undertake programs of research framed by a multi-part question such as:

What specific features of positive development emerge; that are linked to what specific trajectory of child parent relationships; for children and parents of what specific sets of individual psychological, behavioral, and demographic characteristics; living in what specific types of families, schools, faith communities, neighborhoods, nations, cultures, and physical ecologies; at what specific points in ontogenetic development of both child and parent; and at what specific historical periods?

Through conducting programmatic research addressing such specificity-based questions, the particular ontogenetic sets of child parent relationships involved in the life course of specific children and parents may be identified and, as well, the specific relations associated with their respective positive development may be discovered (see Rose, 2016). When such specific child parent relationships are found, that is, when there are mutually beneficial child parent relationships, then adaptive developmental regulations are said to exist (Brandtstädter, 1998). The presence of mutually beneficial (adaptive) child parent relationships across time and place, then, is the basis of positive and healthy development (Brandtstädter, 1998). Therefore, one key outcome of such specificity principle-framed

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Under the German shells

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Under the German shells

Author: Emmanuel Bourcier

Translator: George Nelson Holt Mary Roxy Wilkins Holt

Release date: June 13, 2022 [eBook #68301]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive) *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UNDER THE GERMAN SHELLS ***

UNDER THE GERMAN SHELLS

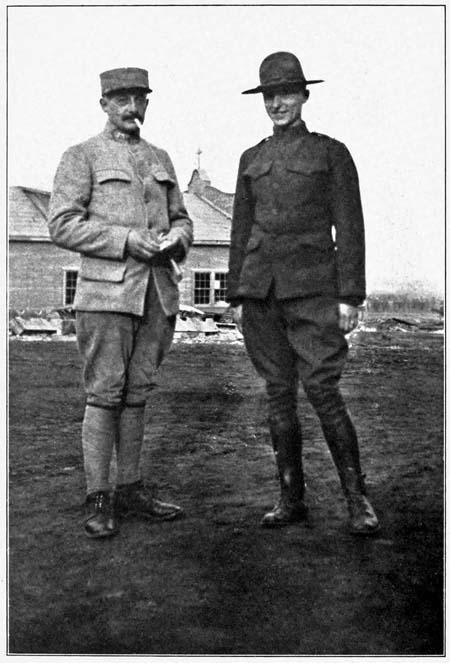

The author at Camp Grant. The American soldier is Divisional Interpreter UmbertoGagliasso.

UNDER THE GERMAN SHELLS

BY EMMANUEL BOURCIER

MEMBER OF THE FRENCH MILITARY COMMISSION TO AMERICA TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY

GEORGE NELSON HOLT AND

MARY R. HOLT WITH PORTRAITS NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS 1918

C��������, 1918, �� CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published May, 1918

PREFACE

L��� is a curious thing. In time of war Life is itself the extraordinary and Death seems the only ordinary thing possible for men.

In time of war man is but a straw thrown into the wide ocean. If the tossing waves do not engulf him he can do no more than float on the surface. God alone knows his destiny.

This book, Under the German Shells, is another instance of war’s uncertainties. Sent by my government to America to join the new American army as instructor, I wrote the greater part of the book on the steamer which brought me. The reader will, perhaps, read it when I am dead; for another steamer is about to carry me back to France, where I shall again be “under the German shells,” before the book will see the light.

This is the second work which I have written during the war. The first, Gens du Front, appeared in France while I was in America. I wrote it in the trenches. The second will appear in America when I shall be in France. The father will not be present at the birth of either of his two children. “C’est la Guerre.”

My only wish is that the work may be of use. I trust it may, for every word is sincere and true. That it may render the greatest service, I wish to give you, my reader, a share in my effort: a part of the money which you pay for the book will be turned over to the French Red Cross Society, to care for the wounded and assist the widows whom misfortune has overtaken while I have been writing. Thus you will lighten the burden of those whom the scourge has stricken.

I hope that you will find in the work some instruction—you who are resolutely preparing to defend Justice and Right and to avenge the insults of the infamous Boche.

I have no other wishes than these for my work, and that victory may be with our united arms.

C��� G����, December 16, 1917.

ILLUSTRATIONS

The author at Camp Grant

Emmanuel Bourcier at the front in the sector of Rheims in 1915

Frontispiece

Facing page 118

Under the German Shells I

THE MOBILIZATION

ONLY those who were actors in the great drama of the mobilization of July, 1914, in France, can at this time appreciate clearly all its phases. No picture, however skilful the hand which traces it, can give in full its tragic grandeur and its impassioned beauty.

Every man who lived through this momentous hour of history regarded its development from a point of view peculiar to himself. According to his situation and environment he experienced sensations which no other could entirely share. Later there will exist as many accounts, verbal or written, of this unique event as there were witnesses. From all these recitals will grow up first the tradition, then the legend. And so our children will learn a story of which we, to-day, are able to grasp but little. This will be a narrative embodying the historic reality, as the Iliad, blending verity and fable, brings down to us the glowing chronicle of the Trojan War. Nevertheless, one distinct thing will dominate the ensemble of these diverse accounts; that is, that the war originated from a German provocation, for no one of Germany’s adversaries thought of war before the ultimatum to Serbia burst like a frightful thunderclap.

At this period there existed in Europe, and perhaps more in France than elsewhere, a vague feeling that a serious crisis was approaching. A sense of uneasiness permeated the national activities and weighed heavily on mind and heart. As the gathering storm charges the air with electricity and gives a feeling of oppression, so the war, before breaking forth, alarmed men and created a sensation of fear, vague, yet terrifying.

To tell the truth, it had been felt for a long time, even in the lowest strata of the French people, that Germany was desirous of provoking war. The Moroccan affair and the incidents in Alsace, especially that of Saverne, made clear to men of every political complexion the danger hanging over the heads of all. No one, however, was willing to believe what proved to be the reality. Each, as far as possible, minimized the menace, refused to accept its verity, and trusted that some happy chance would, at the last moment, discover a solution.

For myself, I must admit this was the case. Although my profession was one that called me to gather on all subjects points of information which escaped the ordinary observer, in common with the rest I allowed my optimism to conceal the danger, and tried always to convince myself that my new-found happiness need fear no attack. I had “pitched my tent.” At least, I believed I had. After having circled the globe, known three continents and breathed under the skies of twenty lands, my wanderlust was satiated and I tried to assure myself that my life henceforth was fixed; that nothing should again oblige me to resume the march or turn my face to adventure.

Alas! human calculations are of little weight before the imperious breath of destiny.

I closed my eyes, as did all my countrymen; but to shut out the storm was impossible. Mingled in all the currents of public events I felt the menacing tempest and, helpless, I regarded the mounting thunderclouds. All showed the dark path of the future and the resistless menace of 1914.

I see again the Paris of that day: that fevered Paris, swayed by a thousand passions, where the mob foresaw the storm, where clamors sprang up from every quarter of the terrible whirlpool of opinions, where clashed so many interests and individuals. Ah! that Paris of July, 1914, that Paris, tumultuous, breathless, seeing the truth but not acknowledging it; excited by a notorious trial[A] and alarmed by the assassination of Sarajevo; only half reassured by the absence of the President of the republic, then travelling in Russia; that Paris on which fell, blow after blow, so many rumors sensational and conflicting.

In the street the tension of life was at the breaking-point. In the home it was scarcely less. Events followed each other with astonishing rapidity. First came the ultimatum to Serbia. On that day I went to meet a friend at the office of the newspaper edited by Clemenceau, and I recall the clairvoyant words of the great statesman: “It means war within a month.”

Words truly prophetic, but to which at that moment I did not attach the importance they merited.

War! War in our century! It was unbelievable. It seemed impossible. It was the general opinion that again, as in so many crises, things would be arranged. One knew that in so many strained situations diplomacy and the government had found a solution. Could it be that this time civilization would fail?

However, as the days rolled on the anxiety became keener One still clung to the hope of a final solution, but one began little by little to fear the worst. In the Chamber of Deputies the nervousness increased, and in the corridors the groups discussed only the ominous portent of the hour. In the newspapers the note of reassurance alternated with the tone of pessimism. The tempest mounted.

At night, when the dinner-hour came, I returned to my young wife. I found her calm as yet, and smiling, but she insistently demanded the assurance that I would accompany her to the seaside at the beginning of the vacation. She had never before asked it with such insistence. She knew that, in spite of my desire, it was impossible for me to be absent so long a time, and other years she had resigned herself to leaving with her baby some weeks before I should lay aside my work. Generally I joined her only a fortnight before her return to Paris. This time a presentiment tortured her far more than she would admit. She made me repeat a score of times my promise to rejoin her at the earliest possible moment. In spite of my vows she could not make up her mind to go, and postponed from day to day our separation. At last I had almost to compel her to leave; to conduct her to the train with a display of gentle authority. She was

warned by an instinct stronger than all my assurances. I did not see her again until thirteen months later.