1 The face is a politics

The face is a politics.

Face value

(Deleuze and Guattari)1

“All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my closeup” Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) famously declares in the concluding moments of William Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), but not everyone in the early days of cinema could claim as much.2 Lillian Gish notes that when D. W. Griffith first moved the camera closer to an actor, the better to capture his facial expression, studio executives responded with outrage: “We pay for the whole actor Mr. Griffith. We want to see all of him.” Noël Burch recounts an anecdote, again from the early days of the cinema, of a woman who responded to a close-up as if it were a moment in a slasher film: “All those severed hands and heads!” Michael Chanan tells the story, also of a woman, who poked her fingers at the image of a girl’s face, “convinced that the whole thing was an impossible illusion, and that there were holes in the screen for the eyes of a real girl standing behind it.”3 Examples could be multiplied almost indefinitely, any or all of which may be apocryphal. But then the idiot observer of the early days of cinema – a paradigmatically female observer – is arguably less an empirical actuality than an ideological convenience. We pride ourselves on our thoroughly demystified relation to the no-longer silver screen. What better way to dramatize that demystification than to juxtapose it against the comic naiveté of our cinematic precursors?

It may be, however, that all this is academic: even if the trauma occasioned by the close-up were real, it was remarkably short-lived. Ingmar Bergman celebrates “the possibility of drawing near the human face” as the “primary originality and distinctive quality of the cinema”; Hitchcock argues that everything in cinema “begins with the actor’s face”; and Jean Epstein terms the close-up “the soul of cinema.” Contemporary film theory is equally enamored of the face. Noa Steimatsky credits film with salvaging the human face; Michael Taussig construes the cinematic face as “the figure of figuration”; Therese Davis considers “the face on film” as a paradigmatic

2 The face is a politics

“model of the image”: Hans Belting terms the face “the body’s witness to the primeval sense of the image”; and again, examples could be multiplied almost indefinitely.4 In one sense, the naive response to “all those severed hands and heads” is the thoroughly sensible response. All movies are de facto slasher movies, and all cinematic bodies are subject to the indignity of decapitation and dismemberment. As the magician is to the painter, Walter Benjamin argues, so the surgeon is to the cameraman, and film and surgical pathology share between them a vocabulary of “cuts,” “sutures,” and the like:

Magician and surgeon compare to painter and cameraman. The painter maintains in his work a natural distance from reality, the cameraman penetrates deeply into its web. There is a tremendous difference between the pictures they obtain. That of the painter is a total one, that of the cameraman consists of multiple fragments which are assembled under a new law. Thus, for contemporary man the representation of reality by the film is incomparably more significant than that of the painter, since it offers, precisely because of the thoroughgoing penetration of reality with mechanical equipment, an aspect of reality which is free of all equipment.5

If the surgeon/cameraman “cuts” – film “inevitably proceeds by severing things,” in Stanley Cavell’s formulation6 – the surgeon/editor “sutures,” and the multiple fragments are (re)assembled under the “new law” of continuity or “invisible” editing. The cinematic “picture” thus seems both “deep” and “total,” a “thoroughgoing penetration” of a fully reconstituted reality. (Early close-ups tended to replicate the angle of long-shots, the better to minimize any tension between part and whole.) Benjamin is right: there is in fact a “tremendous difference” between the pictures obtained by the painter and the cameraman. Yet even an art that maintains “a natural distance from reality” seeks to register the secret singularity within, and both painting and film promote an ethos of the face as “deep text.”7 We may no longer prod the screen in search of the “real” girl hidden behind it, but our distance from the comic naiveté of our cinematic precursors is not as great as commonly supposed. The “poking” continues apace, albeit at a higher level of symbolic abstraction: our “penetration” is hermeneutic, psychosexual. (The “penetration” of the “Bocca della Verità” in William Wyler’s Roman Holiday [1953], which promises the revelation of a hitherto occluded “verità,” renders literal the hermeneutic passion that structures our relation to the screen.) For Bergman, the ability “to draw near” the human face is “the primary originality and distinctive quality of the cinema”; for Jacques Aumont, the desire to figure oneself as face is simply primal:

All representation is really inaugurated by the desire of man to figure himself as face [du désire de l’homme de figure soi-même comme un

The face is a politics 3

visage] … It is not possible to represent without representing the face of man.8

Film may be particularly well equipped, as Madonna puts it, to give “good face,” but its “primary originality” is not original to it. Small wonder, then, that the close-up as trauma rapidly became the close-up as a synecdoche for film itself.9

Regina Jones argues that decapitation is “always already” a symbolic act: “There is nothing natural about decapitation. The deliberate separation of head from body is exclusively cultural … the first sign of the symbolic process that marks our species as distinctly human or at least humanoid.” (Decapitation is apparently no easy matter – primates are physiologically illequipped to engage in it – and skulls are of little practical value in the worka-day world of humanoid hunting, gathering, and the like. The severing of head from body remains, however, an immensely resonant symbolic act.)10 The cinema is sometimes condemned (or, increasingly, celebrated) for the “infantile” or “primitive” nature of the experiences it affords:

Among the “infantile” themes of the early cinema … the frequency of the occurrence of that of the “fragmented” body can, of course, sociohistorically speaking, be attributed to the influence of popular spectacle. The villain of melodrama or Grand Guignol, like the circus conjurer, cut women in half.11

Burch argues that the early fascination with the fragmented body “disappeared as soon as a dissecting editing appeared,” yet it was precisely the invention of a dissecting editing that effectively transformed all movies into slasher movies.12 An “infantile” cinema cuts women in half; a “mature” cinema produces faces through a process of ontological decapitation. As Susan Sontag argues:

All the debunking of the Cartesian separation of mind and body by modern philosophy has not altered by one iota this culture’s conviction of the separation of face and body, which influences every aspect of manners, fashion, sexual appreciation, esthetic sensibility – virtually all our notions of appropriateness. This separation is a main point of one of European culture’s principal iconographical traditions, the depiction of Christian martyrdom, with its astonishing schism between what is inscribed on the face and what is happening to the body … Our very notion of the person, of dignity, depends on the separation of face from body, on the possibility that the face may be exempt, or exempt itself, from what is happening to the body.13

“Our very notion of the person, of dignity” depends on literal decapitation reenacted at a higher level of symbolic abstraction, the metaphoric

4 The face is a politics

separation of the face (as opposed to head, of which more presently) from the body. Sontag associates the “astonishing schism” with the traditional iconography of Christian martyrdom; Deleuze and Guattari attribute the “invention” of the face directly to Christ:

The face is not a universal. It is not even that of the white man; it is White Man himself, with his broad white cheeks and the black hole of his eyes. The face is Christ. The face is the typical European … Not a universal, but facies totius universi. Jesus Christ superstar: he invented the facilialization of the entire body and spread it everywhere (the Passion of Joan of Arc, in close-up). Thus the face is by nature an entirely specific idea, which did not preclude its acquiring and exercising the most general of functions.14

Literal decapitation, the severing of head from body, initiates the symbolic process that marks us as distinctly human. The poetics of the face are inextricably bound to the politics of speciesism, and speciesism, in turn, is inextricably bound to racism: to be marked as distinctly human is to be marked (or, better, non-marked) as distinctly white. Richard Dyer notes that a star’s face can never be white enough, an entirely racist idea that is hard-wired, as it were, into the technology of film itself. (Prior to the introduction of panchromatic film stock, white actors required relatively heavy makeup in order to “pass” as white. Early blue-sensitive or orthochromatic film tended to render pale skin tones dark or black.)15 Ontological decapitation, the separation of face from body, ups the symbolic ante. A decapitated head is still a head; ontological decapitation produces faces. The latter comes to exercise the most general of functions, but it remains an “entirely specific idea,” a historically and ideologically contingent construction.

A head is not, then, a face:

The face is produced only when the head ceases to be part of the body, when it ceases to be coded by the body, when it ceases to have a multidimensional, polyvocal corporeal code – when the body, head included, has been decoded and has to be overcoded by something we shall call the Face.

Certain modalities of power require the production of faces; others do not.16 Ours does. Foucault enjoins us to think power without the King, without a Face, but even a faceless power produces faces in those it constrains.17 Norma Desmond insists that “there just aren’t any faces like that [like hers] anymore,” which is true enough. Where the fabulous face once was – a Garbo or a Swanson or a Dietrich – the “ordinary face of American cinema” came to be.18 The regime of faciality promotes intelligibility, not awe; it is invested in a hermeneutics of the gaze, not an erotics. And if it fetishizes the ordinary, it is because normalization is its goal.

Foucault argues that the emergence of all the modern sciences, analyses or practices employing the root “psycho” – including the hegemony of the “psychological” in art and literature – heralds a new modality of power, and hence a new economy of the subject:

And if from the early Middle Ages to the present day the ‘adventure’ is an account of individuality, the passage from the epic to the novel, from the noble deed to the secret singularity, from long exiles to the internal search for childhood, from combats to phantasies, it is also inscribed in the formation of a disciplinary subject.19

A disciplinary society turns accounts of individuality to account; it wants to know all about Eve or Norma or My Mother. It wants to know, moreover, not only what the mouth explicitly confesses, but what the body unwittingly reveals. The flesh, inscribed or “overcoded” by something called the face, betrays the secret singularity within. In his “Preface” to Miss Julie (1888), Strindberg holds that in “a modern psychological drama … the subtlest movement of the soul must be revealed in the face.”20 But why? Are we to assume that the soul, as if in answer to an imperative intrinsic to it, simply demands proper somatic manifestation? By what logic or compulsion does the psychological come to colonize the face?

Consider the centrality of the face to Foucault’s famous description of the emergence of the nineteenth-century homosexual:

Nothing that went into his total composition was unaffected by his sexuality. It was everywhere present in him: at the root of all his actions because it was their insidious and indefinitely active principle; written immodestly on his face and body because it was a secret that always gave itself away.21

The diacritics of gender are allegedly guaranteed by the visual self-evidence of the body: either you have one or you don’t. The diacritics of race are allegedly guaranteed by the visual self-evidence of the skin: either you’re white or you’re not. But the diacritics of sexuality are seemingly more problematic: homosexuality both challenges and confirms the epistemological certainty afforded by the evidence of sight.22 “You can’t tell your partner’s HIV status by looking,” we are routinely warned, but only to be reassured that AIDS, like the homosexuality with which it is conflated, is, or will be, perfectly legible. Hence, the cover of Life magazine, September 1985: “AIDS was given a face everyone could recognize when it was announced that Rock Hudson, 59, was suffering from the disease.”23 If, then, “the subtlest movement of the soul” must be revealed in the face – the force of Strindberg’s “must” is disproportionately exerted on the sexually deviant and the socially marginal – it is in answer to an imperative that is fully ideological.

An imperative that is fully ideological, but one that finds its most insidious, because most irrefutable, manifestation in the somatic. As D. A. Miller observes:

All the deployments of the “bio-power” that characterize our modernity depend on the supposition that the most effective take on the subject is rooted in its body, insinuated within this body’s “naturally given” imperatives. Metaphorizing the body begins and ends with literalizing the meanings the body is thus made to bear.24

Christ may inaugurate the regime of faciality, but the body is not, as Christian orthodoxy would have it, the prison house of the soul. On the contrary, the soul is “the effect and instrument of a political anatomy,” “the prison of the body.”25 “Anatomy” is to be understood literally: our culture threatens us all with the face it would have us believe we deserve. (The imposition of face characteristically assumes a narrative form, and only those of us of “a certain age” have faces that are received as somatic judgments on the state of the soul.) The regime of faciality is interested in some people more than others: the madman, the delinquent, the prostitute, the racially other, the woman, the homosexual. Lauren Berlant argues that the “privilege to suppress” the material markers of identity, to subsume situated personhood into an “abstract” social body, is the paradoxical condition of racial and gender privilege:

The American subject is privileged to suppress the fact of his historical situation in the abstract “person”: but then, in return, the nation provides a kind of prophylaxis for the person, as it promises to protect his privileges and his local body in return for loyalty to the state … The implicit whiteness and maleness of the original American citizen is thus itself protected by national identity.26

If the whiteness and maleness of “the original American citizen” remain “implicit,” the Blackness and femaleness of the marginal citizen are rendered explicit. The politics of the “abstract” social body and the “abstract” machine of faciality coalesce: whiteness, maleness, and heterosexuality are utterly normative, but they best pass unmarked, unremarked. (By definition, a film with an all-white cast is not “about” race.) It is the socially marginal who characteristically bear the burden of an excessive corporeality. The so-called “right to representation” is not an unproblematic good, and the non-normative pursue it at their peril. (It will, in any case, find them.) Yet if the regime of faciality “privileges” the socially marginal, it nevertheless seeks to gather all and sundry into its imperial embrace. The condition of being “imprisoned in one’s identity, in one’s past, in one’s face,” is the norm.27

Phrenology is a case in point. The pseudo-science has been thoroughly discredited, or at least superseded, yet as Allan Sekula notes, it is as “modern” as the art form that it both presupposes and promotes:

We understand the culture of photographic portraiture only dimly if we fail to recognize the enormous prestige and popularity of a general physiognomic paradigm in the 1840s and 1850s; especially in the United States, photography served as a technological extension of the promise of phrenology.

Universal legibility was the goal:

In claiming to provide a means of distinguishing the stigmata of vice from the shining marks of virtue, physiognomy and phrenology offered an essentially hermeneutic service to a world of fleeting and often anonymous market transactions. Here was a method for quickly assessing the character of strangers in the dangerous and congested spaces of the nineteenth-century city.28

Here, I would add, was an essentially disciplinary reminder that even in the alleged anonymity of urban space one was nevertheless subject to a generalized visibility and legibility. Benjamin locates the origin of the modern detective story in the “obliteration of the individual’s traces in the big city crowd,” which the dark interiors of movie theaters would seem to replicate.29 The anonymity that film promises on the level of consumption is frequently belied, however, on the level of content or theme. In Delmer Daves’s Dark Passage (1947), the taxi driver (Tom D’Andrea) who picks up Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart) immediately recognizes his passenger’s face. Not that this should surprise. Parry is a wanted man and his photograph is posted in all the usual places. But the taxi driver is also an astute reader of the “deep text” that is the face, and what he reads is innocence:

VINCENT: A guy gets lonely driving a taxi, remember?

CABBIE: That’s right brother, lonely. And smart.

VINCENT: Smart in what way?

CABBIE: About people. Faces.

VINCENT: What about faces?

CABBIE: It’s funny. From faces I can tell what people think, what they do, sometimes even who they are.

Being “smart” about faces is a perquisite for the job. It is vitally important for a taxi driver to be able to assess the character of strangers in the dangerous and congested spaces of the modern city, and the cabbie is right. (He helps Vincent, who is in fact innocent, elude the authorities by directing him

8 The face is a politics

to a back-alley plastic surgeon.) In effect, the promise of phrenology – and its technological extension in and through photography – releases the panopticon from its moorings in architectural space and introduces the principle of a universal legibility into everyday life.

Motion pictures cannot be directly accused of the same. We see them up there on the silver screen; they do not see us down there in the darkened auditorium, and the ability to see without oneself being seen, as Freud says in a different context, is the unique privilege of the spectator. The gaze operates in one direction only:

At first glance, the cinema would seem to be remote from the undercover world of the surreptitious observation of an unknowing and unwilling victim. What is seen on the screen is so manifestly shown. But the mass of mainstream film, and the conventions within which it has consciously evolved, portray a hermetically sealed world which unwinds magically, indifferent to the presence of the audience, producing for them a sense of separation and playing on their voyeuristic phantasy. … Although the film is really being shown, is there to be seen, conditions of screening and narrative conventions give the spectator an illusion of looking in on a private world.30

“At first glance,” perhaps, but not all movies are remote from the work-aday world of “the surreptitious observation of an unknowing and unwilling victim.” Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), to cite the now paradigmatic example, foregrounds the operations of surveillance both in their explicitly photographic and implicitly cinematic manifestations. J. L. Jefferies (James Stewart), a photographer temporarily laid up with a broken leg, passes the time by casually spying on his neighbors; when he suspects a man in the apartment block opposite him of having murdered his wife, he begins sleuthing in earnest. Jefferies is clearly “the bearer of the look” or lens; we identify with him and see, at least to a significant extent, through his prosthetically enhanced eyes.31 But the subject-who-looks is also the objectthat-is-seen, and at a crucial moment in the diegesis, Jefferies falls asleep, which Hitchcock’s camera duly registers. The point here is not simply that we gain access to information about the comings and goings of the suspect neighbor (Raymond Burr) that is unavailable to Jefferies. Rather, surveillance itself is liberated from point of view or perspective, and hence from individuality and subjectivity. Jefferies attempts to involve his friend Doyle, a detective, in his investigations, but with minimal success. The amateur sleuth is more astute than his professional counterpart – Scotland Yard is no match for Sherlock Holmes – but even the extension of the police function beyond the police proper does not render surveillance universal.32 So long as Jefferies remains the bearer of the lens, the gaze is attributable to the individual subject-who-sees, which is duly registered in subjective or point-of-view shots. Only in the pan that indiscriminately catches both the

The face is a politics 9

sleeping Jefferies and the departing Thorwald, in which neither controls the shot, does surveillance truly penetrate the entirety of the film’s limited social world. The pan thus functions as the formal analogue to the operations of a power that is “intentional” – it actively labors to see and to know – but that is not thereby “subjective.”33

Michael Chanan argues that film – unlike, say, the telegraph or telephone –was initially ill equipped to serve the purposes of intelligence gathering:

As a technology for instantaneous communication over long distances, the telegraph served the needs of the capitalist class itself for improved intelligence. As for the telephone … it joined together the appeal of a personal luxury item with a means of accelerating and increasing the flow (or rate of distribution) of local, then national, and finally international commercial traffic. Cinematography, however, was primarily a form of disconnected non-linguistic display, not very well adapted to the purposes of intelligence. Moreover, the film, like the gramophone record, is a physical object which cannot evade the physical problems of distribution by achieving instant transmission over long distances.34

Early cameras were too unwieldy and noisy to be of much use in recording illicit sexual encounters and the like, yet as Stephen Bottomore notes, any number of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century works, literary and cinematic, nevertheless focus on assignations caught and subsequently exhibited on film.35 The examples are literally fictitious, but as Foucault insists, even “fictitious relations” can produce “real subjection”:

The efficiency of power, its constraining force have, in a sense, passed over to the other side – to the side of its surface of application. He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection.36

No matter, then, that early cameras lacked the technological capabilities that were routinely ascribed to them. An economy of surveillance requires only the subject’s nagging suspicion, however irrational or paranoid it may seem, that there are (prosthetically enhanced) eyes everywhere.

Jefferies’s still camera is more or less adequate to the task of “intelligence gathering” in the conventional sense of the term. The invention of photography is inextricably bound to the history of criminology – Benjamin argues that the former is to the latter as the printing press is to literature37 – and Jefferies’s lens does prove helpful in ferreting out the guilty party. (This despite the fact that we never once see him take an actual photograph.) A photographic purchase on the world is not, however, without its limitations.

Jefferies suffers from the common delusion that still photography literally “stills” the world it seeks to register. He shatters his leg attempting to “shoot” a car that is speeding towards him (he apparently thinks the camera sufficient defense against it), and in the climactic scene of the movie, he uses the flash from his camera to “still” Thorwald’s murderous advance. But nothing is thereby “stilled,” and even the bearer of the lens is implicated in the field of visibility that he is thus powerless to command. Jefferies himself comes to realize that the gaze operates in two directions: “Of course, they can do the same thing to me – watch me like a bug under glass if they want to.” The psychosexual scrutiny to which we subject Jeffries is not, however, “the same thing.” He looks for evidence of literal violence directed against Mrs. Thorwald’s body; we engage in symbolic violence directed against his soul. Hitchcock’s camera polices internal affairs, the psychosexual makeup of the amateur sleuth who looks.

Robert Stam and Roberta Pearson view Rear Window as a case study in classical panopticism:

He [Jefferies] is the warden, as it were, in a private panopticon. Seated in his central tower, he observes the wards (“small captive shadows in the cells of the periphery”) in an imaginary prison. Michel Foucault’s description of the cells of the panopticon – “so many cages, so many small theaters, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible” – in some ways aptly describes the scene exposed to Jefferies’s glance.38

“In some ways,” but not all, and Hitchcock’s departures from Foucault’s “description of the cells of the panopticon” are as significant as the similarities. The “warden” of a panopticon typically sees without himself being seen, to return to Freud’s formulation, which is manifestly not the case with the “bug-under-glass” that is Jefferies. The “wards” of a panopticon, moreover, must know that they are seen, at least if the efficacy of power is to pass over to “the other side,” to the side of “the surface of its application.” But with the possible exception of Miss Torso, all the characters in Rear Window are oblivious, at least initially, to the operations of Jefferies’s gaze. (A state of affairs that exactly reproduces the conditions of cinematic intelligibility: although everything conspires to assure their visibility, characters on the screen are allegedly oblivious to the spectator’s gaze.) Classical panopticism presupposes a subject confined within a “closed” institution: prison, school, factory, and the like. The only fully carceral subject in Rear Window, however, is Jefferies himself (and perhaps Mrs. Thorwald), and Jefferies encourages mobility in others. He tricks Thorwald into leaving his apartment in order to provide Lisa access to it, and, with the help of his friend Doyle, he monitors the movements of Thorwald’s luggage. But if Rear Window thus departs from classical panopticism, it is only to construct an economy of surveillance adequate to the conditions of urban modernity. In

D. J. Caruso’s Disturbia, a 2007 riff on Rear Window, Kale Brecht (Shia LaBeouf), the Jimmy Stewart character, takes to spying on his neighbors after he is placed under house arrest, literally subjected to electronic monitoring. Classical panopticism favors closed, brick-and-mortar institutions; Disturbia deploys ankle bracelets and proximity sensors. But if the movie thus evinces what Deleuze terms “a generalized crisis in relation to all the environments of enclosure” – and the consequent birth of “a society of control” – the disciplinary desire to see and to know remains constant.39 Rear Window includes a Bing Crosby “love song” that is a virtual “Ode to Panopticism”:

To see you is to want you And I see you all the time

On a sidewalk, in a doorway

On a lonely stairs I climb

….

To see you is to love you

And you’re never out of sight.40

To be seen on a sidewalk or in a doorway is to be seen outside the confines of a closed institution; unlike its classical counterpart, urban panopticism allows for the illusion of anonymity and unfettered mobility. There is, however, no obliteration of the individual’s traces in the big city crowd, and the urban subject is effectively never out of sight.

In Techniques of the Observer, Jonathan Crary argues that the disembodied, interiorizing paradigm of vision promoted by the camera obscura, the privileged metaphor for sight in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was radically transformed in the nineteenth. The invention of photography dramatized the productive role played by the body in vision; physiology replaced Cartesian mental privacy as the model of subjective action and response, and vision was henceforth thinkable only in relation to the “opacity and carnal density” of the observer.41 In Rear Window, however, the cinematic lens that captures the corporeal density of the photographic observer also violates his “mental privacy.” Physiology proves, in proper psychoanalytic fashion, to be the royal road to psychology:

We must recall the question that has so often been raised, whether the symptoms of hysteria are of psychical or of somatic origin, or whether, if the former is granted, they are necessarily psychically determined. Like so many other questions to which we find investigators returning again and again without success, the question is not adequately framed. The alternatives stated in it do not cover the real essence of the matter. As far as I can see, every hysterical symptom involves the participation of both sides. It cannot occur without the presence of a certain degree of somatic compliance offered by some normal or pathological process in or in connection with one of the bodily organs.42

This is Freud, but an analogous question – is Jefferies’s injury of somatic or psychical significance? – has also been asked of Rear Window. And again, the alternatives stated do not adequately cover the matter: it is clearly both. Speeding cars can and do break bones, and Rear Window offers a perfectly plausible explanation for Jefferies’s shattered leg. The somatic does not, however, exhaust the issue, and Jefferies’s cast bears mute testimony to a wounded masculinity. The physiological is inextricably bound to the psychosexual, and vision is finally thinkable only in relation to the “always already” violated subjectivity of the embodied observer-who-is-observed.

Stella (Thelma Ritter), Jefferies’s nurse, argues that the gaze should function in two directions: “What people ought to do is get outside their own homes and look in for a change.” And Stella does in fact look in from the outside. After digging up Thorwald’s garden, she turns back to look at Jefferies in the window of his apartment. Looking in from the outside is not, however, to be confused with looking inward:

STELLA: Look, Mr. Jefferies, I’m not an educated woman, but I can tell you one thing. When a man and a woman see each other and like each other, they ought to come together – wham! – like two taxis on Broadway and not sit around analyzing each other like two specimens in a bottle.

JEFFERIES: There is an intelligent way to approach marriage.

STELLA: Intelligence. Nothing has caused the human race so much trouble as intelligence. Hmm. Modern marriage.

JEFFERIES: Now, we have progressed emotionally.

STELLA: Baloney. Once it was see somebody, get excited, get married. Now it is read a lot of books; fence with a lot of four syllable words; psychoanalyze each other until you can’t tell the difference between a petting party and a civil service exam.

Stella’s contempt for excessive introspection is unabashedly pre-modern. She reminds Jefferies that the punishment for the Peeping Tomism that we now call, rather grandly, “scopophilia” was once a red-hot poker to the eyes, but Jefferies’s voyeurism is hardly of the classical kind. “Once it was see somebody, get excited”; today, it is see somebody, start psychoanalyzing, and Stella opposes any relation to the body that “excites” only a hermeneutic frenzy. Jefferies himself becomes “a specimen in a bottle” – for us if not for Lisa – and the temptation to psychoanalyze proves well-nigh irresistible. It is Hitchcock and his screenwriter who introduce the love interest between Jefferies and Lisa into the plot, and it is Jefferies’s curiously unexcited relation to women that excites the most heated psychosexual speculation. (Speculation that characteristically issues in the most familiar of psychoanalytic “insights”: the man is a latent homosexual. Here “the ordinary face” of US cinema – and was there ever a face that aspired to ordinariness more aggressively than Jimmy Stewart’s? – is sexually suspect.) It might seem, of course, that a petting party, not psychosexual speculation, should generate

The face is a politics 13

the heat. But as Foucault notes, such is the erotic impoverishment of a world that has managed to invent only one pleasure:

…pleasure in the truth of pleasure, the pleasure of knowing that truth, of discovering and exposing it, the fascination of seeing it and telling it, of captivating and capturing others by it, of confiding it in secret, of luring it out in the open – the specific pleasure of the true discourse on pleasure.43

Robert Sobieszek argues that the emerge of psychoanalysis was the death knell for “physiognomic culture”: “What followed [from and after Freud] might be labeled a ‘psychoanalytic culture,’ in which the self and the soul were imploded and impacted within the mind and its subconscious, and the physiological face was rendered moot if not mute.”44 The hermeneutic passion that informs phrenology is, however, alive and well, and the mute eloquence of the Freudian body owes more to the phrenological paradigm than it cares to acknowledge:

He that has eyes to see and ears to hear may convince himself that no mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his finger tips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore. And thus the task of making conscious the hidden recesses of the mind is one which is quite possible to accomplish.45

Benjamin explicitly associates the task with the promise of the new science of the soul, the new art of the motion picture:

The film has enriched our field of perception with methods which can be illustrated by those of Freudian theory. Fifty years ago, a slip of the tongue passed more or less unnoticed. Only exceptionally may such a slip have revealed dimensions of depth in a conversation which had seemed to be taking its course on the surface. Since The Psychopathology of Everyday Life things have changed. This book isolated and made analyzable things which had heretofore floated along unnoticed in the broad stream of perception. For the entire spectrum of optical, and now also acoustical perception, the film has brought about a similar deepening of apperception. It is only the obverse of this fact that behavior items shown in a movie can be analyzed more precisely and from more points of view than those presented on paintings or on the stage.46

Freud would have resisted the comparison – Leo Löwenthal characterized mass culture as “psychoanalysis in reverse”47 – but Benjamin’s point remains broadly compelling. The simultaneous emergence of film and psychoanalysis as defining cultural experiences is hardly an innocent historical coincidence, and the cinematic enrichment of our field of perception can in fact be illustrated through recourse to Freudian theory. Photography, the

The face is a politics

emergent art of the nineteenth century, presupposes the immense prestige of phrenology; film, the dominant art of the twentieth century, presupposes the Freudian body. (By which I mean the “confessing” body, which is everybody’s body, whatever one’s conscious relation to Freudianism happens to be. In Rear Window, Stella adopts an aggressively anti-Freudian stance, yet her reading of the world is finally no less Freudian for that.) This is not, I hasten to add, to dismiss psychoanalysis as phrenology redux. It is to insist, however, that the hermeneutic investment that informs phrenology is still very much with us. Benjamin celebrates the revolutionary potential of the new art of the motion picture. The legitimate “desire of contemporary masses to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly, which is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction,” finds its logical fulfillment in an art form the primary originality and distinctive quality of which is the ability to draw near.48 My own project is less optimistic. A disciplinary society presupposes the “deepening [and expansion] of the field of apperception,” the subjection of virtually all things, all faces, to an analytical gaze.

Mitchell Gray argues that contemporary facial recognition technology threatens “to breach a final frontier of surveillance”:

The potential of facial recognition systems – the seamless integration of linked databases of human images and the automated digital recollection of the past – will necessarily alter societal conceptions of privacy as well as the dynamics of individual and group interactions in public space. More strikingly, psychological theory linked to facial recognition technology holds the potential to breach a final frontier of surveillance, enabling attempts to read the minds of those under its gaze by analyzing the flickers of involuntary microexpressions that cross their faces and betray their emotions.49

The potential that Gray attributes to facial recognition systems is already implicit in the catalogue of faces in Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), one of the first scientific publications to be illustrated with photography. Digital databases and the like merely confirm and extend the disciplinary reach of the photographic. The “diagram of the human face is always combining differently with new techniques and technologies,” but the face remains “the dominant surface for tracking, tracing and controlling the subject.”50 Foucault emphasizes the centrality of the face to the construction of the nineteenth-century homosexual; the facial recognition technology developed by Michal Kosinski and Yilun Wang of Stanford University purports to read the perverse sexuality of those under its gaze. The question posed by Gray – “Will we recognize the facial recognition society?” – is easily answered: “the facial recognition society” is recognizable as “gaydar” literalized, high-tech outing for the twenty-first century. (According to Kosinski and Wang, gay men have narrower jaws

The face is a politics 15

and longer noses than their heterosexual counterparts; gay women have larger jaws.) By definition, the “microexpressions” of perversion are not written “immodestly” on the face – Balázs speaks of the close-up in terms of “microphysiognomics”51 – but they are no less legible for that.

The face machine

The English term “close-up” implies proximity, a change of distance or perspective in relation to a person or thing. The (non)equivalent French term, gros plan, denotes size, scale, grandeur, a transformation in the nature of the person or thing itself. Eisenstein, who registers the linguistic and national differences, seeks to release the term from the imperial hold of its English meaning. (Russian is of the party of French.) Griffith was the first to move the camera closer to an actor, and from Griffith, Eisenstein maintains, we have inherited a “narrowly representational” (mis)understanding of the close-up: “at all times [he] remains on a level of representation and objectivity … nowhere does he try through the juxtaposition of shots to shape import and image.” The proper function of the close-up is not “to show or to present,” but “to signify, to give meaning, to designate”; by introducing absolute changes into the dimensions of people and things, the close-up releases cinema from the naively or narrowly mimetic.52 Hollywood cinema is generally considered anthropomorphic:

The cinema satisfies a primordial wish for pleasurable looking, but it also goes further, developing scopophilia in its narcissistic aspect. The conventions of mainstream film focus attention on the human form. Scale, space, stories are all anthropomorphic. Here, curiosity and the wish to look intermingle with a fascination with likeness and recognition: the human face, the human body, the relationship between the human form and its surroundings, the visible presence of the person in the world.53

With the introduction of the close-up, however, the screen is deprived of its human shape and form. The miniature can appear as the gigantic, which potentially renders the human a stranger in a strange land. Eisenstein construes the close-up as an “absolute” transformation in the size or scale of the image, and only incidentally in terms of the perspective of the camera or spectator. But which is it? Proximity or positing? Is “the primary originality and distinctive quality” of cinema its ability to draw close to the human face understood as a pre- or proto-filmic entity? Or does cinema produce the faces it requires as the illusion of its own grounding?

Strindberg’s theater aspires toward proximity:

In a modern psychological drama, where the subtlest movements of the soul must be revealed more through the face than through gesture and sound, it would probably be best to experiment with strong side lighting

The face is a politics

on a small stage, and with actors wearing no makeup, or at least a minimum of it.54

It would have been even better for Strindberg’s purposes, however, if the newly emerging medium of film had been available to him. Cinema allegedly brings all things close, thus rendering legible “those subtler motions of the face, shoulder, rib cage and pelvis” that reflect “inner states,” but which are “scarcely visible from the distant galleries and boxes of the ‘legitimate’ theater, vaudeville or burlesque.”55 Strindberg recommends little or no makeup for the stage actor, but the comparatively naked face is really a cinematic (or, more specifically, a Hollywood) ideal. British actors prepare a face to meet the faces that they meet, but the Hollywood star system requires that its most marketable commodities be immediately recognizable.56 (Not “immediately,” however, in terms of the temporal unfolding of the narrative. Hollywood cinema frequently pays homage to a star’s face by deferring visual access to it. In Frank Perry’s Mommie Dearest [1981], the belated revelation of Faye Dunaway’s face, her extraordinary transformation into Joan Crawford, functions as the ultimate “money shot.”)57 Greasepaint, the heavy makeup of theatrical fame, implicitly acknowledges the somatic agents of representation as recalcitrant, which hearkens back to the masks of classical theater, to the non-organic inscription on the head of meanings extrinsic to it; the comparatively naked faces favored by Hollywood promote the illusion that meaning emerges spontaneously from within. Yet as Hans Belting notes, the “mask upon the face and the face on the body do not ultimately stand in contradiction to each other”; both are images that appear “on a surface, whether that surface be natural skin or an imitation made from some inert material.”58 The mask is simply a demystified face. Belá Balázs thought the printing press robbed human kind of its ability to read faces: typographical culture displaces a natural expressivity with an arbitrary order of signs. But if technology robs, it also restores, and the silent screen returns the mute eloquence of the face to pre-Gutenberg standards of universal intelligibility.59 Hugo Münsterberg, the first US academic to write a monograph on film, implicitly concurs:

There is a girl in her little room, and she opens a letter and reads it. There is no need of showing us in close-up the letter page with the male handwriting and the words of love and request for her hand. We see it in her radiant visage, we read it from her fascinated arms and hands; and yet how much more can the photoartist tell us about the storm of emotions in her soul. The walls of her little room fade away. Beautiful hedges of hawthorn blossom surround her, rose bushes in wonderful glory arise and the whole ground is alive with exotic flowers.60

The sentimentality of the scenario – one would have to have a heart of stone not to laugh – is rivaled only by the inadequacy of the analysis. Granted,

The face is a politics 17

Münsterberg has a point. The poetics of heterosexual romance, here as everywhere, are fully intelligible without recourse to “the letter-page,” and universal intelligibility was a source of considerable pride for early apologists for the silent screen. Other media may depend on an arbitrary order of signifiers – or so it was argued – but film requires only the innate expressivity of the body natural. Viktor Shklovsky characterizes cinema as “conversation prior to an alphabet,” and Virginia Woolf celebrates the new medium as a language “rendered visible without the help of words.”61 Yet even if heterosexual desire does go without saying or writing, the “radiant visage” does not therefore speak for itself. Substitute, say, a dead baby for Münsterberg’s hawthorn blossom – Hitchcock, following V. I. Pudovkin, recommends the experiment – and the face reads rather differently:

You see a close-up of the Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine. This is immediately followed by a shot of a dead baby. Back to Mosjoukine again and you read compassion on his face. Then you take away the dead baby and you show a plate of soup, and now, when you go back to Mosjoukine, he looks hungry. Yet, in both cases, they used the same shot of the actor; his face was exactly the same.62

The “natural” expressivity of the face is itself an effect of the visual grammar of montage, and the purely relational interaction of face and hawthorn blossom or face and dead baby or face and soup determines what the former will seem to say. (Gregory Peck on being directed by Hitchcock: “In answer to any question about mood or expression he would simply say that I was to drain my face of all expression and he would photograph me.” And for the magnificent close-up at the end of Queen Christina [1933], Mamoulian apparently told Garbo to think of nothing at all: “I want your face to be a blank sheet of paper.”)63 The natural expressivity of the face does not, then, ground the cinematic apparatus. Rather, the apparatus – Deleuze and Guattari term it “the abstract machine of faciality” – produces the face as the illusion of its own grounding:

Concrete faces cannot be assumed to come ready-made. They are engendered by an abstract machine of faciality [visagéité], which produces them at the same time as it gives the signifier its white wall and subjectivity its black hole. Thus the black hole/white wall system is, to begin with, not a face but the abstract machine that produces faces according to the changeable combinations of its cogwheels. Do not expect the abstract machine to resemble what it produces, or will produce.64

The close-up is frequently said to be “freighted with an inherent separability” or isolation that eludes the “tactics of continuity editing that strive to make it whole again … [It] embodies the pure fact of presentation, of

18 The face is a politics

manifestation, of showing – a ‘here it is.’ ”65 What the close-up will be made to mean, however, is freighted with a pure positionality.

The close-up of the early cinema might seem an exception, and as Jean Mitry notes, the close-up, understood as proximity, is as old as the cinema itself:

“The big heads” (grosses têtes) as they were called, suddenly appearing in the midst of a uniform sequence of long-shots, had been used by Méliès in his films around 1910, and the alarm bell in The Life of an American Fireman is, without doubt, the first close-up of an object recorded on film.66

“Big heads” were not, however, close-ups in the fully cinematic sense of the term. Mitry cites a familiar example, a trial scene in which a defendant sits in the dock anxiously awaiting a verdict:

The whole proceeding would be in long-shot. Then, by means of a kind of dissolve achieved by closing and opening the iris, the camera (from exactly the same angle) “went looking for” the defendant and brought him back in closeup (an iris placed in front of the lens enclosed the image in a progressively tighter circle and opened up again on the next image becoming wider and wider). That meant that the defendant could be seen making the same gestures and playing the same scene.67

Although the iris placed in front of the lens literally isolated the face in a circle, the early close-up was not thereby freighted with an inherent separability. By exactly replicating the angle of the long-shot – as opposed, say, to filming in profile or from the back or in three-quarters – the close-up remained continuous with it. The camera “went looking” for the face in a manner that respected the integrity of what was still theatrical, rather than fully cinematic, space. André Malraux argues that the

birth of the cinema as a means of expression … can be said to date from the breakdown of the limited space [of the theater]; from the period when the scriptwriter conceived his narrative in terms of separate shots, when he began to think not of photographing a play but of recording a succession of moments.68

By Malraux’s standards, Münsterberg’s scenario is fully cinematic. The photoartist reveals the storm of emotions in the young woman’s soul by cross-cutting from face to hawthorn blossom, by conceiving of the scene in terms of separate shots. Positionality, not the self-evidence of showing or manifesting, determines what the close-up will be made to mean.

Debra Fried notes that even a close-up that we experience as a single moment within an ongoing two-shot, without the intervention of hawthorn

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

have been sufficiently described above (p. 55), and it remains only to be mentioned that the bones of the palatine arch are but rarely absent, as for instance in Murænophis; and that the symplectic does not extend to the articulary of the mandible, as in Amia and Lepidosteus, though its suspensory relation to the Meckelian cartilage is still indicated by a ligament which connects the two pieces. Of the mandibulary bones the articulary (35) is distinctly part of Meckel’s cartilage. Frequently another portion of cartilage below the articulary remains persistent, or is replaced by a separate membrane-bone, the angular

4. Membrane-bones of the alimentary portion of the visceral skeleton of the skull.—The suspensorium has one tegumentary bone attached to it, viz. the præoperculum (30); it is but rarely absent, for instance in Murænophis. The premaxillary (17) and maxillary (18) of the Teleostei appear to be also membrane-bones, although they are clearly analogous to the upper labial cartilages of the Sharks. The premaxillaries sometimes coalesce into a single piece (as in Diodon, Mormyrus), or they are firmly united with the maxillaries (as in all Gymnodonts, Serrasalmo, etc.) The relative position and connection of these two bones differs much, and is a valuable character in the discrimination of the various families. In some, the front margin of the jaw is formed by the premaxillary only, the two bones having a parallel position, as it has been described in the Perch (p. 53); in others, the premaxillary is shortened, allowing the maxillary to enter, and to complete, the margin of the upper jaw; and finally, in many no part of the maxillary is situated behind the premaxillary, but the entire bone is attached to the end of the premaxillary, forming its continuation. In the last case the maxillary may be quite abortive. The mobility of the upper jaw is greatest in those fishes in which the premaxillary alone forms its margin. The form of the premaxillary is subject to great variation: the beak of Belone, Xiphias is formed by the prolonged and coalesced premaxillaries. The maxillary consists sometimes of one piece, sometimes of two or three. The principal membrane-bone of the mandible is the dentary (34), to which is added the angular (36) and rarely a smaller one, the splenial or os operculare, which is situated at the inside of the articulary.

5. Cartilage-bones of the respiratory portion of the visceral skeleton of the skull.—With few exceptions all the ossifications of the hyoid and branchial arches, as described above (p. 58), belong to this group.

6. Membrane-bones of the respiratory portion of the visceral skeleton of the skull.—They are the following: the opercular pieces, viz. operculum (28), sub-operculum (32), and interoperculum (33). The last of these is the least constant; it may be entirely absent, and represented by a ligament extending from the mandible to the hyoid. The urohyal (42) which separates the musculi sternohyoidei, and serves for an increased surface of their insertion; and finally the branchiostegals (43), which vary greatly in number, but are always fixed to the cerato- and epi-hyals.

7. Dermal bones of the skull.—To this category are referred some bones which are ossifications of, and belong to, the cutis. They are the turbinals (20), the suborbitals (19), and the supratemporals. They vary much with regard to the degree in which they are developed, and are rarely entirely absent. Nearly always they are wholly or partly transformed into tubes or hollows, in which the muciferous canals with their numerous nerves are lodged. Those in the temporal and scapulary regions are not always developed; on the other hand, the series of those ossicles may be continued on to the trunk, accompanying the lateral line. In many fishes those of the infraorbital ring are much dilated, protecting the entire space between the orbit and the rim of the præoperculum; in others, especially those which have the angle of the præoperculum armed with a powerful spine, the infraorbital ring emits a process towards the spine, which thus serves as a stay or support of this weapon (Scorpænidæ, Cottidæ).

The pectoral arch of the Teleosteous fishes exhibits but a remnant of a primordial cartilage, which is replaced by two ossifications,[10] the coracoid (51) and scapula (52); they offer posteriorly attachment to two series of short rods, of which the proximal are nearly always ossified, whilst the distal frequently remain small cartilaginous nodules hidden in the base of the pectoral rays. The bones, by which this portion is connected with the skull, are membrane-bones, viz. the clavicle (49), with the postclavicle (49

+ 50), the supraclavicle (47), and post-temporal (46). The order of their arrangement in the Perch has been described above (p. 59). However, many Teleosteous fish lack pectoral fins, and in them the pectoral arch is frequently more or less reduced or rudimentary, as in many species of Murænidæ. In others the membrane-bones are exceedingly strong, contributing to the outer protective armour of the fish, and then the clavicles are generally suturally connected in the median line. The postclavicula and the supraclavicula may be absent. Only exceptionally the shoulder-girdle is not suspended from the skull, but from the anterior portion of the spinous column (Symbranchidæ, Murænidæ, Notacanthidæ). The number of basal elements of each of the two series never exceeds five, but may be less; and the distal series is absent in Siluroids.

The pubic bones of the Teleosteous fishes undergo many modifications of form in the various families, but they are essentially of the same simple type as in the Perch.

CHAPTER V.

MYOLOGY.

In the lowest vertebrate, Branchiostoma, the whole of the muscular mass is arranged in a longitudinal band running along each side of the body; it is vertically divided into a number of flakes or segments (myocommas) by aponeurotic septa, which serve as the surfaces of insertion to the muscular fibres. But this muscular band has no connection with the notochord except in its foremost portion, where some relation has been formed to the visceral skeleton. A very thin muscular layer covers the abdomen.

Also in the Cyclostomes the greatest portion of the muscular system is without direct relation to the skeleton, and, again, it is only on the skull and visceral skeleton where distinct muscles have been differentiated for special functions.

To the development of the skeleton in the more highly organised fishes corresponds a similar development of the muscles; and the maxillary and branchial apparatus, the pectoral and ventral fins, the vertical fins, and especially the caudal, possess a separate system of muscles. But the most noteworthy is the muscle covering the sides of the trunk and tail (already noticed in Branchiostoma), which Cuvier described as the “great lateral muscle,” and which, in the higher fishes, is a compound of many smaller segments, corresponding in number with the vertebræ. Each lateral muscle is divided by a median longitudinal groove into a dorsal and ventral half; the depression in its middle is filled by an embryonal muscular substance which contains a large quantity of fat and blood-vessels, and therefore differs from ordinary muscle by its softer consistency, and by its colour which is reddish or grayish. Superficially the lateral muscle appears crossed by a number of white parallel tendinous zigzag stripes, forming generally three angles, of which the upper and lower point backwards, the middle one forwards. These are the outer edges of the aponeurotic septa between the myocommas. Each septum is attached to the middle and the apophyses of a vertebra, and, in the abdominal region, to its rib; frequently the septa receive additional support by the existence of epipleural spines. The fibres of

each myocomma run straight and nearly horizontally from one septum to the next; they are grouped so as to form semiconical masses, of which the upper and lower have their apices turned backwards, whilst the middle cone, formed by the contiguous parts of the preceding, has its apex directed forward; this fits into the interspace between the antecedent upper and lower cones, the apices of which reciprocally enter the depressions in the succeeding segment, whereby all the segments are firmly locked together (Owen).

In connection with the muscles reference has to be made to the Electric organs with which certain fishes are provided, as it is more than probable, not only from the examination of peculiar muscular organs occurring in the Rays, Mormyrus, and Gymnarchus (the function of which is still conjectural), but especially from the researches into the development of the electric organ of Torpedo, that the electric organs have been developed out of muscular substance. The fishes possessing fully developed electric organs, with the power of accumulating electric force and communicating it in the form of shocks to other animals, are the electric Rays (Torpedinidæ), the electric Sheath-fish of tropical Africa (Malapterurus), and the electric Eel of tropical America (Gymnotus). The structure and arrangement of the electric organ is very different in these fishes, and will be subsequently described in the special account of the several species.

The phenomena attending the exercise of this extraordinary faculty also closely resemble muscular action. The time and strength of the discharge are entirely under the control of the fish. The power is exhausted after some time, and it needs repose and nourishment to restore it. If the electric nerves are cut and divided from the brain the cerebral action is interrupted, and no irritant to the body has any effect to excite electric discharge; but if their ends be irritated the discharge takes place, just as a muscle is excited to contraction under similar circumstances. And, singularly enough, the application of strychnine causes simultaneously a tetanic state of the muscles and a rapid succession of involuntary electric discharges. The strength of the discharges depends entirely on the size, health, and

energy of the fish: an observation entirely agreeing with that made on the efficacy of snake-poison. Like this latter, the property of the electric force serves two ends in the economy of the animals which are endowed with it; it is essential and necessary to them for overpowering, stunning, or killing the creatures on which they feed, whilst incidentally they use it as the means of defending themselves from their enemies.

CHAPTER VI.

NEUROLOGY.

The most simple condition of the nervous central organ known in Vertebrates is found in Branchiostoma. In this fish the spinal chord tapers at both ends, an anterior cerebral swelling, or anything approaching a brain, being absent. It is band-like along its middle third, and groups of darker cells mark the origins of the fifty or sixty pairs of nerves which accompany the intermuscular septa, and divide into a dorsal and ventral branch, as in other fishes. The two anterior pairs pass to the membranous parts above the mouth, and supply with nerve filaments a ciliated depression near the extremity of the fish, which is considered to be an olfactory organ, and two pigment spots, the rudiments of eyes. An auditory organ is absent.

The spinal chord of the Cyclostomes is flattened in its whole extent, band-like, and elastic; also in Chimæra it is elastic, but flattened in its posterior portion only. In all other fishes it is cylindrical, non-ductile, and generally extending along the whole length of the spinal canal. The Plectognaths offer a singular exception in this respect that the spinal chord is much shortened, the posterior portion of the canal being occupied by a long cauda equina; this shortening of the spinal chord has become extreme in the Sun-fish (Orthagoriscus), in which it has shrunk into a short and conical appendage of the brain. Also in the Devil-fish (Lophius) a long cauda equina partly conceals the chord which terminates on the level of about the twelfth vertebra.

The brain of fishes is relatively small; in the Burbot (Lota) it has been estimated to be 1/720th part of the weight of the entire fish, in the Pike the 1/1305th part, and in the large Sharks it is relatively still smaller. It never fills the entire cavity of the cranium; between the dura mater which adheres to the inner surface of the cranial cavity, and the arachnoidea which envelops the brain, a more or less considerable space remains, which is filled with a soft gelatinous mass generally containing a large quantity of fat. It has been observed that this space is much less in young specimens than in adult, which proves that the brain of fishes does not grow in the

same proportion as the rest of the body; and, indeed, its size is nearly the same in individuals of which one is double the bulk of the other.

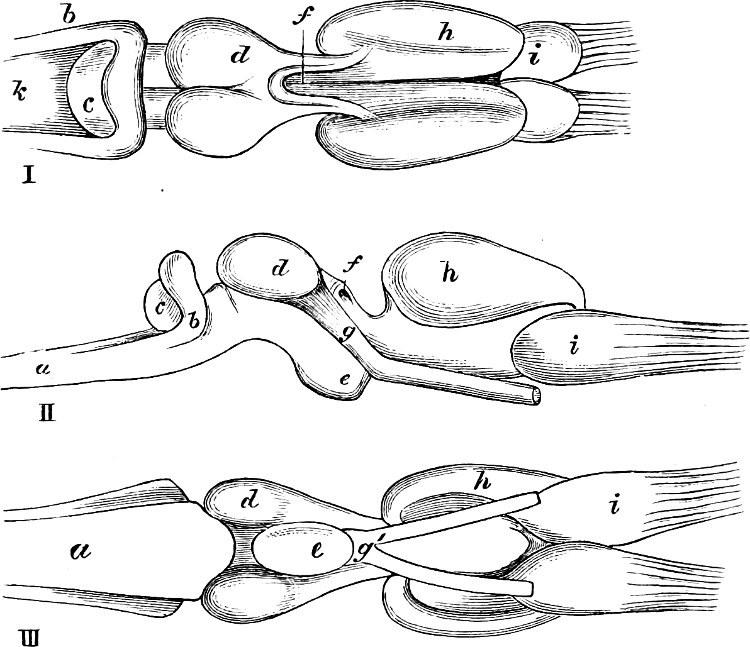

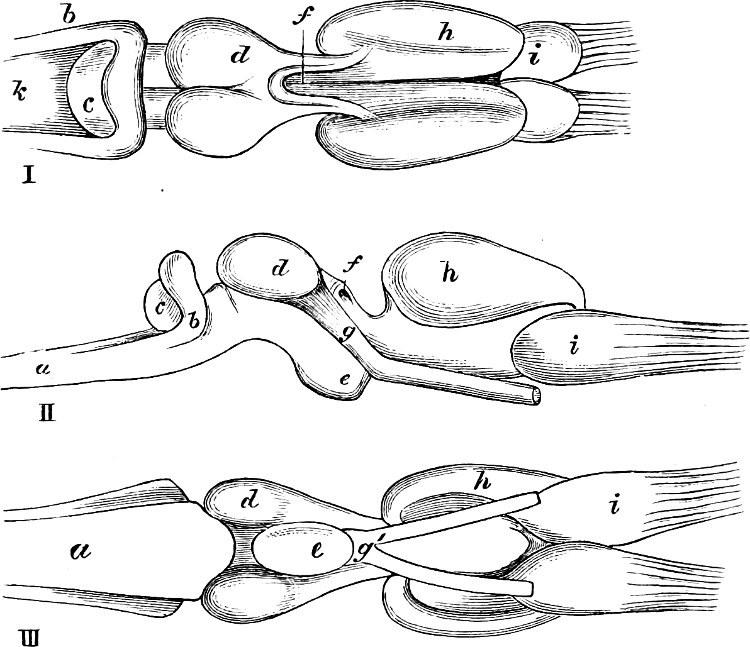

41 Brain of Perch

I. Upper aspect. II. Lower aspect. a, cerebellum; b, optic lobes; c, hemispheres; e, lobi inferiores; f, hypophysis; g, lobi posteriores; i, Olfactory lobes; n, N opticus; o, N olfactorius; p, N oculomotorius; q, N trochlearis; r, N trigeminus; s, N acusticus; t, N vagus; u, N abducens; v, Fourth ventricle

The brain of Osseous fishes (Fig. 41) viewed from above shows three protuberances, respectively termed prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and metencephalon, the two anterior of which are paired, the hindmost being single. The foremost pair are the hemispheres, which are solid in their interior, and provided with two swellings in front, the olfactory lobes. The second pair are the optic lobes, which generally are larger than the hemispheres, and succeeded by the third single portion, the cerebellum. In the fresh state the hemispheres are of a grayish colour, and often show some shallow depressions on their surface; a narrow commissure of white colour connects them with each other. The optic lobes possess a cavity (ventriculus lobioptici), at the bottom of which some protuberances of variable development represent the corpora quadrigemina of higher animals. On the lower surface of the base of the optic lobes, behind the crura cerebri, two swellings are observed, the lobi inferiores, which slightly diverge in front for the passage of the infundibulum, from which a generally large hypophysis or pituitary gland is suspended. The relative size of the cerebellum varies greatly in the different osseous fishes: in the Tunny and Silurus it is so large as nearly to cover the optic lobes; sometimes

Fig

distinct transverse grooves and a median longitudinal groove are visible. The cerebellum possesses in its interior a cavity which communicates with the anterior part of the fourth ventricle. The medulla oblongata is broader than the spinal chord, and contains the fourth ventricle, which forms the continuation of the central canal of the spinal chord. In most fishes a perfect roof is formed over the fourth ventricle by two longitudinal pads, which meet each other in the median line (lobi posteriores), and but rarely it remains open along its upper surface.

The brain of Ganoid fishes shows great similarity to that of the Teleostei; however, there is considerable diversity of the arrangement of its various portions in the different types. In the Sturgeons and Polypterus (Fig. 42) the hemispheres are more or less remote from the mesencephalon, so that in an upper view the crura cerebri, with the intermediate entrance into the third ventricle (fissura cerebri magna), may be seen. A vascular membranous sac, containing lymphatic fluid (epiphysis), takes its origin from the third ventricle, its base being expanded over the anterior interspace of the optic lobes, and the apex being fixed to the cartilaginous roof of the cranium. This structure is not peculiar to the Ganoids, but found in various stages of development in Teleosteans, marking, when present, the boundary between prosencephalon and mesencephalon. The lobi optici are essentially as in Teleosteans. The cerebellum penetrates into the ventriculus lobi optici, and extends thence into the open sinus rhomboidalis. At its upper surface it is crossed by a commissure formed by the corpora restiformia of the medulla.

Fig 42 Brain of Polypterus (After Müller )

I., Upper; II., Lateral; III., Lower aspect. a, Medulla; b, corpora restiformia; c, cerebellum; d, lobi optici; e, hypophysis; f, fissura cerebri magna; g, nervus opticus; g’ , chiasma; h, hemispheres; i, lobus olfactorius; k, sinus rhomboidalis (fourth ventricle)

As regards external configuration, the brain of Lepidosteus and Amia approach still more the Teleosteous type. The prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and metencephalon are contiguous, and the cerebellum lacks the prominent transverse commissure at its upper surface. The sinus rhomboidalis is open.

The brain of the Dipnoi shows characters reminding us of that of the Ganoids as well as the Chondropterygians, Ceratodus agreeing

with Protopterus in this respect, as in most other points of its organisation. The hemispheres form the largest part of the brain; they are coalescent, as in Sharks, but possess two lateral ventricles, the separation being externally indicated by a shallow median groove on the upper surface. The olfactory lobes take their origin from the upper anterior end of the hemispheres. Epiphysis and hypophysis well developed. The lobi optici are very small, and remote from the prosencephalon, their division into the lateral halves being indicated by a median groove only. The cerebellum is very small, overlying the front part of the sinus rhomboidalis.

43.—Brain of Carcharias. (After Owen.)

ac, Nerv. acusticus; b, corpus restiforme; c, cerebellum; d, lobus opticus; e, hypophysis; g, nervus opticus; h, hemisphere; i, lobus olfactorius; i’, olfactory pedicle; k, nerv olfactorius; l, epiphysis; m, nerv oculo-motorius; tr, nerv trigeminus; v, nerv vagus

The brain of Chondropterygians (Fig. 43) is more developed than that of all other fishes, and distinguished by well-marked characters. These are, first, the prolongation of the olfactory lobes into more or less long pedicles, which dilate into great ganglionic masses, where they come into contact with the olfactory sacs; secondly, the space

Fig.

which generally intervenes between prosencephalon and mesencephalon, as in some Ganoids; thirdly, the large development of the metencephalon.

The hemispheres are generally large, coalescent, but with a median, longitudinal, dividing groove. Frequently their surface shows traces of gyrations, and when they are provided with lateral ventricles, tubercles representing corpora striata may be observed. The olfactory pedicles take their origin from the side of the hemispheres, and are frequently hollow, and if so, their cavity communicates with the ventricle of the hemisphere. The optic lobes are generally smaller than the hemispheres, coalescent, and provided with an upper median groove like the prosencephalon. At their base a pair of lobi inferiores are constant, with the hypophysis and sacsus vasculosus (a conglomeration of vascular loops without medullary substance) between them.

The cerebellum is very large, overlying a portion of the optic lobes and of the sinus rhomboidalis, and is frequently transversely grooved. The side-walls of the fourth ventricle, which are formed by the corpora restiformia, are singularly folded, and appear as two pads, one on each side of the cerebellum (lobi posteriores s. lobi nervi trigemini).

Fig 44 Brain of Bdellostoma (Enlarged, after Müller )

I., Upper; II., Lower aspect. Letters as in Fig. 45.

Fig 45 Brain of Petromyzon (Enlarged, after Müller )

I., Upper; II., Lower aspect.

a, Medulla oblongata; ac, nerv acusticus; b, corpus restiforme or rudimentary cerebellum; d, lobus ventriculi tertii; d’, entrance into the third ventricle; c, hypophysis; fa, nerv facialis; g, nerv opticus; h, hemisphere; hy, nerv hypoglossus (so named by Müller); i, lobus olfactorius; k, sinus rhomboidalis; l,

epiphysis; m, nerv. oculo-motorius; q, corpora quadrigemina; tr, nerv. trigeminus; tro, nerv trochlearis; v, nerv vagus

The brain of the Cyclostomes (Figs. 44, 45) represents a type different from that of other fishes, showing at its upper surface three pairs of protuberances in front of the cerebellum; they are all solid. Their homologies are not yet satisfactorily determined, parts of the Myxinoid brain having received by the same observers determinations very different from those given to the corresponding parts of the brain of the Lampreys. The foremost pair are the large olfactory tubercles, which are exceedingly large in Petromyzon. They are followed by the hemispheres, with a single body wedged in between their posterior half; in Petromyzon, at least, the vascular tissue leading to an epiphysis seems to be connected with this body. Then follows the lobus ventriculi tertii, distinctly paired in Myxinoids, less so in Petromyzon. The last pair are the corpora quadrigemina. According to this interpretation the cerebellum would be absent in Myxinoids, and represented in Petromyzon by a narrow commissure only (Fig. 45, b), stretching over the foremost part of the sinus rhomboidalis. In the Myxinoids the medulla oblongata ends in two divergent swellings, free and obtuse at their extremity, from which most of the cerebral nerves take their origin.

The Nerves which supply the organs of the head are either merely continuations or diverticula of the brain-substance, or proper nerves taking their origin from the brain, or receiving their constituent parts from the foremost part of the spinal chord. The number of these spino-cerebral nerves is always less than in the higher vertebrates, and their arrangement varies considerably.

A. Nerves which are diverticula of the brain (Figs. 41–45).

The olfactory nerves (first pair) always retain their intimate relation to the hemispheres, the ventricles of which are not rarely continued into the tubercle or even pedicle of the nerves. The different position of the olfactory tubercle has been already described as characteristic of some of the orders of fishes. In those fishes in which the tubercle is remote from the brain, the nerve which has entered the tubercle as a single stem leaves it split up into

several or numerous branches, which are distributed in the nasal organ. In the other fishes it breaks up into branchlets spread into a fan-like expansion at the point, where it enters the nasal cavity. The nerve always passes out of the skull through the ethmoid.

The optic nerves (second pair) vary in size, their strength corresponding to the size of the eye; they take their origin from the lobi optici, the development of which again is proportionate to that of the nerves. The mutual relation of the two nerves immediately after their origin is very characteristic of the sub-classes of fishes. In the Cyclostomes they have no further connection with each other, each going to the eye of its own side.[11] In the Teleostei they simply cross each other (decussate), so that the one starting from the right half of the brain goes to the left eye and vice versa. Finally, in Palæichthyes the two nerves are fused together, immediately after their origin, into a chiasma. The nerve is cylindrical for some portion of its course, but in most fishes gradually changes this form into that of a plaited band, which is capable of separation and expansion. It enters the bulbus generally behind and above its axis. The foramen through which it leaves the skull of Teleostei is generally in a membranous portion of its anterior wall, or, where ossification has taken place, in the orbitosphenoid.

B. Nerves proper taking their origin from the brain (Figs. 41–45).

The Nervus oculorum motorius (third pair) takes its origin from the Pedunculus cerebri, close behind the lobi inferiores; it escapes through the orbito-sphenoid, or the membrane replacing it, and is distributed to the musculi rectus superior, rectus internus, obliquus inferior, and rectus inferior. Its size corresponds to the development of the muscles of the eye. Consequently it is absent in the blind Amblyopsis, and the Myxinoids. In Lepidosiren the nerves supplying the muscles of the eye have no independent origin, but are part of the ophthalmic division of the Trigeminus. In Petromyzon these muscles are supplied partly from the Trigeminus, partly by a nerve representing the Oculo-motor and Trochlearis, which are fused into a common trunk.

The Nervus trochlearis (fourth pair), if present with an independent origin, is always thin, taking its origin on the upper surface of the brain from the groove between lobus opticus and cerebellum; it goes to the Musculus obliquus superior of the eye.

C. Nerves taking their origin from the Medulla oblongata (Figs. 41–45).

The Nervus abducens (sixth pair) issues on the lower surface of the brain, taking its origin from the anterior pyramids of the Medulla oblongata, and supplies the Musculus rectus externus of the eye, and the muscle of the nictitating membrane of Sharks.

The Nervus trigeminus (fifth pair) and the Nervus facialis (seventh pair) have their origins close together, and enter into intimate connection with each other. In the Chondropterygians and most Teleostei the number of their roots is four, in the Sturgeons five, and in a few Teleostei three. When there are four, the first issues immediately below the cerebellum from the side of the Medulla oblongata; it contains motory and sensory elements for the maxillary and suspensorial muscles, and belongs exclusively to the trigeminal nerve. The second root, which generally becomes free a little above the first, supplies especially the elements for the Ramus palatinus, which sometimes unites with parts of the Trigeminal, sometimes with the Facial nerve. The third root, if present, is very small, and issues immediately in front of the acustic nerve, and supplies part of the motor elements of the facial nerve. The fourth root is much stronger, sometimes double, and its elements pass again partly into the Trigeminal, partly into the Facial nerve. On the passage of these stems through the skull (through a foramen or foramina in the alisphenoid) they form a ganglionic plexus, in which the palatine ramus and the first stem of the Trigeminus generally possess discrete ganglia. The branches which issue from the plexus and belong exclusively to the Trigeminus, supply the organs and integuments of the frontal, ophthalmic, and nasal regions, and the upper and lower jaws with their soft parts. The Facial nerve supplies the muscles of the gill-cover and suspensorium, and emits a strong branch accompanying the Meckelian cartilage to the symphysis, and another for the hyoid apparatus.

The Nervus acusticus (eighth pair) is strong, and takes its origin immediately behind, and in contact with, the last root of the seventh pair.

The Nervus glossopharyngeus (ninth pair)[12] takes its origin between the roots of the eighth and tenth nerves, and issues in Teleostei from the cranial cavity by a foramen of the exoccipital. In the Cyclostomes and Lepidosiren it is part of the Nervus vagus. It is distributed in the pharyngeal and lingual regions, one branch supplying the first branchial arch. After having left the cranial cavity it swells into a ganglion, which in Teleostei is always in communication with the sympathic nerve.