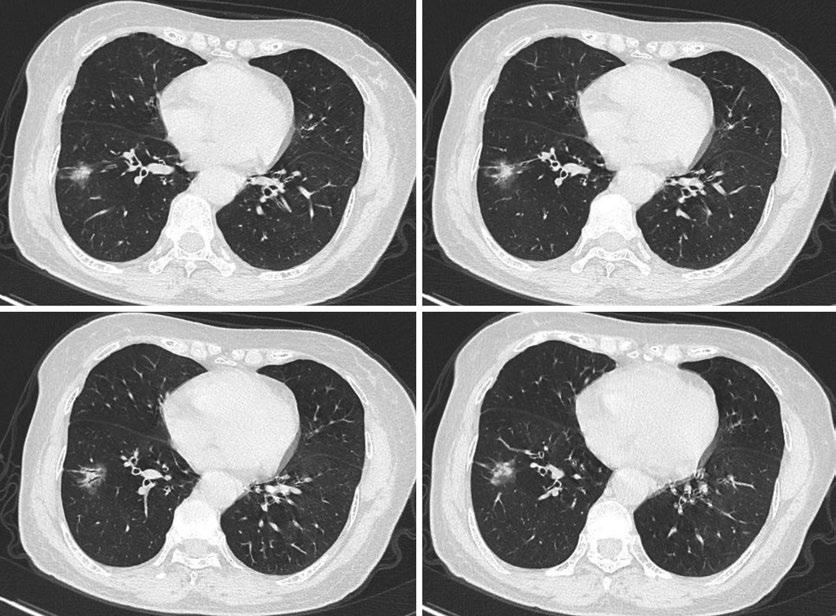

Case Analysis

3.1 Case 1

A 46-year-old woman found a lung lesion for 4 days on physical examination.

Chest CT: A quasi-circular pure ground-glass nodule in the right upper lung lobe, with a diameter of approximately 5.0 mm (Fig. 1).

[Diagnosis] Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a 5.0 mm well-defned round nodule with pure ground-glass opacity in the apical segment of the upper right lung lobe. The pulmonary vessel penetrates the ground-glass opacity lesion without any vascular compromise. On the resection specimen, the lesion size was measured as 5 × 3 × 3 mm, and the lesion was diagnosed as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia.

[Analysis] Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH), frst described in the 1999 WHO classifcation, is pathologically defned as a small (usually less than 5 mm in diameter), limited, mild-to-moderate atypical proliferation of type II alveolar epithelial cells and/or Clara cells in the alveolar wall or the respiratory bronchiolar wall. AAH is mostly discovered incidentally in the surgically resected lung tissue due to other problems, especially primary lung cancer. The incidence of AAH ranges from 9.3% to 21.4% of cases resected from primary lung cancer, whereas

the incidence of AAH in patients with benign or metastatic disease has been reported to be approximately 4.4% to 9.6%. Chapman et al. [11] reported that AAH was found more frequently in the lungs of adenocarcinoma (23.2%) compared with large cell undifferentiated carcinoma (12.5%) or squamous cell carcinoma (3.3%). Women with adenocarcinoma were more likely to have AAH (30.2%) than men with adenocarcinoma (18.8%). Due to the widespread use of CT in clinical practice and the large-scale screening of early lung cancer, the number of AAH lesions detected by radiology have been increasing.

AAH has been described as a focal nodular ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesion on CT. Ground-glass nodule (GGN) lesion is defned as hazy increased attenuation of the lung, but with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins. Almost all AAH appear to be pure GGN(pGGN) without any solid content. The pathological basis of pGGN is alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, the increase in the number of cells in the alveoli, thickening of the alveolar septum, and fuid accumulation in the bronchiole terminals. The interface between AAH and normal lung parenchyma is clear, and the edges are smooth. No blood vessel convergence or pleural retraction was detected. AAH has predominance for the upper lobes and can be either solitary or multifocal and does not change on the follow-up CT.

AAH is recognized as a preinvasive lesion of lung adenocarcinoma, which can be safely just

Fig. 1 Chest CT

followed by CT rather than surgical biopsy or resection. According to the tumor doubling time, a two- or three-year follow-up will be safe enough to confrm whether the lesion is AAH.

3.2 Case 2

A 43-year-old woman found a lung lesion on physical examination.

Chest CT: A pure GGO nodule of 15 mm in diameter in the right lower lung lobe (Fig. 2).

[Diagnosis] Adenocarcinoma in situ.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a pure GGO nodule in the right lower lung lobe with clear boundary, regular shape. On the wedge resection specimen, the lesion was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma in situ (Fig. 3).

[Analysis] According to the 2015 WHO classifcation of lung adenocarcinoma, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) were defned as preinvasive lung adenocarcinoma lesions. In the 2021 WHO classifcation of lung tumors, they were categorized as precursor glandular lesions.

AIS was defined as a small ( ≤ 3 cm), localized adenocarcinoma with a pure lepidic growth that lacked stromal, vascular, alveolar space, or pleural invasion. Patterns of invasive adenocarcinoma (such as acinar, papillary, micropapillary, solid, colloid, enteric, fetal or invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma) and spread through air spaces are absent. If a tumor larger than 3 cm has been completely sampled histologically and shows no invasion, the tumor should be classified as “lepidic adenocarcinoma, suspect AIS.”

Fig. 2 Chest CT

Fig. 3 Photomicrograph shows the lepidic growth pattern along alveolar septa with no identifed focus of invasion

AIS is subdivided into non-mucinous and mucinous variants. Most AIS are non-mucinous, which consists of type II pneumocytes and/or Clara cells. The rare cases of mucinous AIS consist of tall columnar cells and abundant cytoplasmic mucin. Nuclear atypia is absent or inconspicuous in both non-mucinous and mucinous AIS. Septal widening with sclerosis is common in AIS, particularly the non-mucinous variant. Most AIS patients are non-smokers and women. Mucinous AIS was signifcantly correlated with younger age, a TTF-1-negative cell lineage, and a wild-type EGFR. Both AAH and AIS demonstrate a replacing growth pattern along the alveolar lining, with no alveolar wall destruction, which makes it very challenging to make a clear-cut distinction between the two

entities. Generally, AAH exhibits no attendant stromal thickening. In AIS, cell atypia may be more pronounced than in AAH.

On CT, the typical appearance of nonmucinous AIS is pure ground-glass nodule (pGGN) but sometimes as a part solid or occasionally a solid nodule. Mucinous AIS can appear as a solid nodule or consolidation (Fig. 4). The solid component represents fbrosis rather than invasion. AIS can be either single or multiple (Fig. 5).

It is often diffcult to differentiate AAH from AIS. AAH usually has more air spaces and fewer cellular components than AIS, so that the density of AIS is slightly higher than that of AAH. AIS can also be distinguished from AAH on the basis of the mean CT attenuation. The

Fig. 4 A 73-year-old man with mucinous AIS. (a) CT scan shows a partly solid nodule in the right lower lobe. (b) Mucinous AIS consists of purely lepidic growth of

tumor cells and intra-alveolar mucin. Neither stromal nor vascular invasion is seen

Fig. 5 A 47-year-old woman with AIS in the bilateral lungs

S. Zhang

mean CT attenuation of AAH is approximately 700 HU, which was signifcantly smaller than approximately 600HU for AIS. Kitami et al.

[12] found that GGNs with a maximum diameter of ≤10 mm and CT value of ≤−600 HU are nearly always preinvasive lesions. The vacuole sign, a gassy, lucent shadow with a diameter of<5 mm, can also aid in the differentiation between AAH and AIS.

3.3 Case 3

A 51-year-old woman found a lung lesion on physical examination.

Chest CT: A GGO nodule in the right upper lung lobe (Fig. 6).

[Diagnosis] Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a GGO nodule in the upper lobe of right lung with bubble lucency and intact vessel distorted, supporting the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Patient underwent right upper lobectomy, the diameter of the lesion was approximately 7 mm, and the lesion was diagnosed as minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (Fig. 7).

[Analysis] MIA is a small (≤3 cm), solitary adenocarcinoma with a predominantly lepidic growth, showing ≤5 mm invasion along its greatest dimension, and lacking lymphatic, vascular, alveolar space, or pleural invasion. The invasive component to be measured includes any histo-

logic subtype other than a lepidic pattern (such as acinar, papillary, micropapillary, solid, colloid, fetal, or invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma) or is defned as tumor cells infltrating a myofbroblastic stroma. The cell type mostly nonmucinous (type II pneumocytes or Clara cells), but rarely may be mucinous (tall columnar cells with basal nuclei and abundant cytoplasmic mucin, sometimes resembling goblet cells) [7]. When there are multiple independent tumors, AIS and MIA should only be diagnosed if the lesions are considered to be synchronous primaries rather than intrapulmonary metastases. If a tumor larger than 3 cm has been completely sampled histologically and shows less than or equal to 0.5 cm of invasion, the tumor should be classifed as “lepidic adenocarcinoma, suspect MIA.”

The terms AIS and MIA are not suitable for diagnosis of small biopsies or cytology speci-

Fig. 6 Chest CT

Fig. 7 The tumor shows a predominately lepidic growth pattern

mens. If there is a non-invasive pattern in a small biopsy, it should be referred to as a lepidic growth pattern. Similarly, if a cytology specimen exhibits AIS characteristics, the tumor should be diagnosed as an adenocarcinoma, possibly with a comment that this may represent, at least in part, AIS.

The imaging presentations of MIA can be pure GGO (Fig. 8) or part-solid nodule (Fig. 9) or even a solid nodule. Lee et al. [13] retrospectively investigated 55 pulmonary nodules in 52 patients pathologically confrmed as MIA, 53.8% were pure GGNs, 42.3% were part-solid GGNs, and

3.8% were solid nodules. Xiang et al. [14] suggested that the threshold of mean CT value for distinguishing between MIA and preinvasive lesions was 520 HU.

Pulmonary GGNs may histopathologically represent a variety of disorders such as lung adenocarcinoma, eosinophilic lung disease, pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorder, or organizing pneumonia/fbrosis. Henschke et al. [15] classifed GGNs as solid, part-solid, or non-solid (pure GGO). They also reported that 63% of part-solid and 18% of non-solid nodules were malignant. Based on the presence of solid components in the

Fig. 8 A 50-year-old man with MIA showing GGO increase in size. (a) GGO in the left upper lobe, measuring 6 mm in diameter at detection. (b) Growth by 3 mm was confrmed after 9 months

Fig. 9 A 57-year-old man with predominantly ground-glass with small central solid elements in the right lower lung lobe

S. Zhang

nodules, GGNs are divided into two types: mixed GGO and pure GGO. AAH, AIS, MIA, and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC) can be manifested as pure GGO or mixed GGO in CT imaging. AAH, AIS, and MIA grow along the walls of respiratory bronchioles and alveoli, most of them are pure GGO. If there is signifcant local fbroblast proliferation, local accumulation of tumor cells or collapse of alveolar walls, AAH, AIS, and MIA are usually manifested as mixed GGO. Kakinuma et al. [16] investigated that 7294 participants underwent screening for lung cancer with CT imaging, and identifed 439 solitary pure GGNs 5 mm or smaller. Of the 439 pure GGNs, 394 were stable and 45 (10.3%) grew. Of the 45 pure GGNs that grew, 0.9% (four of 439) developed into adenocarcinomas (two minimally invasive and two invasive). In the four adenocarcinomas, the mean period between baseline CT screening and the appearance of solid components was 3.6 years. Their conclusion was that solitary pure GGNs of 5 mm or smaller detected by using CT screening should be rescanned 3.5 years later to search for development of a solid component. Yankelevitz et al. [17] investigated 57,496 participants underwent baseline and subsequent annual repeat CT screenings, and identifed 2392 (4.2%) non-solid nodules, and pathologic pursuit led to the diagnosis of 73 cases of adenocarcinoma. A new non-solid nodule was identifed in 485 (0.7%) of 64,677 annual repeat screenings, and 11 had a diagnosis of stage I adenocarcinoma; none were in nodules 15 mm or larger in diameter. Median time to treatment was 19 months. A solid component had developed in 22 cases prior to treatment (median transition time from non-solid to part-solid, 25 months). The lung cancer-survival rate was 100% with median follow-up since diagnosis of 78 month. They concluded that non-solid nodules of any size can be safely followed with CT at 12-month intervals to assess transition to part-solid. Surgery was 100% curative in all cases, regardless of the time to treatment. Ichinose et al. [18] examined 191 GGO lesions, including 114 pure GGO and 77 mixed lesions.160 patients underwent surgical resection. Among 114 pure GGO lesions, 14 (12%) were diagnosed as invasive lung cancer

and 16 (14%) as MIA. Pure GGO lesions should be carefully monitored by periodic chest CT, and resection is recommended when they exhibit pleural indentation on HRCT or positivity on PET.

Approximately 10%–25% of pure GGNs increases in size or grow the solid component, while others remain unchanged for years. The Fleischner Society 2017 guidelines suggest that pure GGNs smaller than 6 mm in diameter do not require routine follow-up. For pure GGNs 6 mm or larger, follow-up scanning is recommended at 6–12 months and then every 2 years thereafter until 5 years. To date, numerous reports have shown that pure GGNs that are 6 mm or larger may be followed safely for 5 years, with an average of 3–4 years typically required to establish growth or, less commonly, to diagnose a developing invasive carcinoma. For solitary part-solid nodules smaller than 6 mm, no routine follow-up is recommended. In practice, discrete solid components cannot be reliably defned in such small nodules, and they should be treated similar to the way in which pure groundglass lesions of equivalent size are treated. For solitary part-solid nodules 6 mm or larger with a solid component less than 6 mm in diameter, follow-up is recommended at 3–6 months and then annually for a minimum of 5 years. Although part-solid nodules have a high likelihood of malignancy, nodules with a solid component smaller than 6 mm typically represent either AIS or MIA rather than invasive adenocarcinoma. For solitary part-solid nodules with a solid component 6 mm or larger, a short-term follow-up CT scan at 3–6 months should be considered to evaluate for persistence of the nodule. Abundant evidence has confrmed that the larger the solid component, the greater the risk of invasiveness and metastases. A solid component larger than 5 mm correlates with a substantial likelihood of local invasion [19].

Guidelines for the management of GGNs that have been stable for 5 years have not been determined. Lee et al. [20] conducted an observational study to investigate the natural course of GGNs that has had been stabilized for 5 years by low-dose CT. A total of 208 GGNs were

detected in 160 participants. During a follow-up of 136 months, GGN growth was found in 27 (13.0%) GGNs. In approximately 95% of GGNs, the initial size was less than 6 mm, with 3.2 mm of growth over 8.5 years. Three out of 27 GGNs underwent biopsy and showed adenocarcinoma. In 8 of 27 cases, GGN growth preceded the development of a new solid component. In a multivariate analysis, bubble lucency, a history of cancer other than lung cancer, and development of a new solid component were important risk factors for GGN growth. They concluded that GGNs should not be ignored, even if it is smaller than 6 mm and stable for 5 years, especially when a new solid component appears during follow-up.

Wedge resection or segmentectomy is usually surgical method performed for AIS and MIA to maximize the preservation of functional lung parenchyma. After complete resection, the 5-year disease-free survival reaches 100% or nearly 100%. Since there is no regional lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis in AIS and MIA, it is no need for lymph node dissection during surgery.

Hu et al. [21] performed the analyses of multiregion whole-exome sequencing of 116 resected lung nodules including AAH (n = 22), AIS (n = 27), MIA (n = 54), and synchronous adenocarcinoma (ADC) (n = 13). They observed progressive genomic evolution at the single nucleotide level and demarcated evolution at the chromosomal level and supported the early lung carcinogenesis model from AAH to AIS, MIA, and ADC.

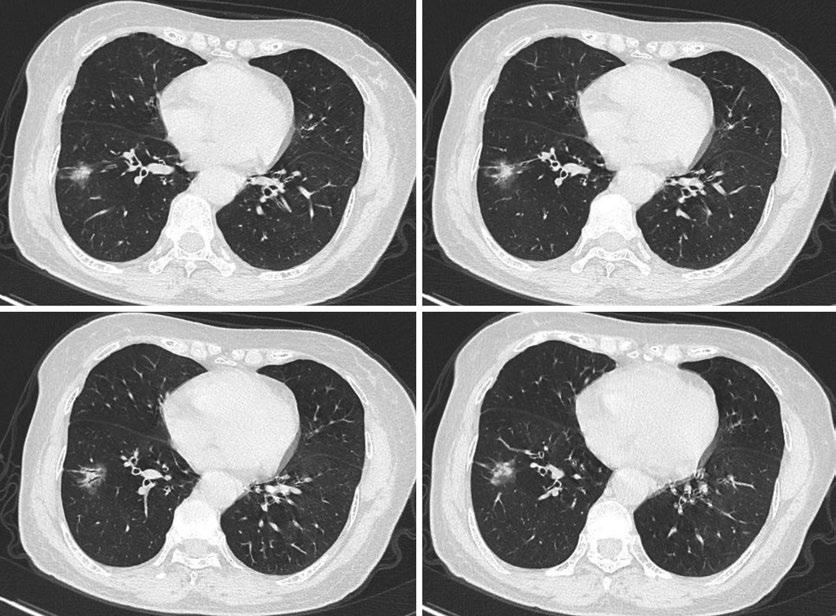

3.4 Case 4

A 65-year-old woman found a lung lesion for 2 months on physical examination.

Chest CT: A nodule in the right lower lung lobe (Fig. 10).

[Diagnosis] Invasive adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a mixed GGO nodule in the lower lobe of

S. Zhang

right lung with lobulation, spiculation, air bronchogram, well-defned but coarse interface and pleural indentation, favoring the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Patient underwent right lower lobectomy, the lesion was approximately 3 × 2 × 1 cm, diagnosed as invasive adenocarcinoma (80% acinar type, and 20% lepidic type).

[Analysis] In the 2021 WHO classifcation, in addition to the rare variants, invasive adenocarcinoma is divided as non-mucinous and mucinous types. Invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinomas are the commonest subtype of lung cancer, consisting of malignant epithelial tumors with morphological or immunohistochemical evidence of glandular differentiation and not fulflling criteria for any other type of adenocarcinoma, including lepidic, acinar, papillary, micropapillary, and solid growth patterns. Under the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ ERS and 2015 WHO guidelines, invasive adenocarcinomas are classifed according to the predominant subtype after evaluation of the tumor using comprehensive histologic subtyping to make a semiquantitative estimate of all of the different histologic patterns present in 5% increments. It is very useful to determine the predominant subtype when a tumor has two patterns with relatively similar percentages and allows reporting small amounts of components that may be prognostically important such as micropapillary or solid patterns. It also helps to distinguish multiple synchronous primary lung adenocarcinomas from a dominant tumor with pulmonary metastases.

Invasive adenocarcinoma is usually visualized as solid nodule, corresponding with the >5 mm of overt invasion seen on histopathology, but may also be part-solid nodule or occasionally GGN. Accepted predictors of malignancy include upper lobe location, size, and the presence of spiculation. For part-solid nodules, suspicious morphologic features include lobulated margins, air bronchograms, pleural tags, vascular convergence sign, and bubble-like lucencies (pseudocavitation), but none has been reliably shown to discriminate between benign and malignant nodules for these features. Spiculation (also called sunburst or corona radiata sign) is caused by

interlobular septal thickening, fbrosis caused by obstruction of pulmonary vessels or lymphatic channels flled with tumor cells. A nodule with a spiculation is much more likely to be malignant than one with a smooth, well-defned margin. Lobulation is defned when portion of lesion’s surface shows wavy or scalloped confguration. Lobulation in a nodule is attributed to different or uneven growth rates and is highly correlated with malignant tumors. Air bronchogram is defned when air-flled bronchus is present inside nodule, which strongly suggests invasive adenocarcinoma over MIA. Pleural tag is defned as one or more linear strands heading toward pleura. They correlate with thickening of the interlobular septa of the lung and can be caused by edema, tumor extension, infammation, or fbrosis. Vascular convergence sign is described as vessels converging to a nodule without adjoining or contacting the edge of the nodule and is mainly seen in peripheral subsolid lesions. Bubble-like lucencies are areas of low attenuation due to small pat-

ent air-containing bronchi in the nodule. In subsolid nodules, bubble-like lucencies are slightly more common in invasive adenocarcinomas than in preinvasive lesions and are uncommon in non-neoplastic nodules.

Most studies have shown that lepidic adenocarcinomas are low grade; acinar and papillary tumors are intermediate grade; solid and micropapillary tumors are high grade. Patients with stage I lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma have an excellent prognosis; most of those tumors that recur have some high-risk factors, such as close margin in limited resection and the presence of micropapillary components or vascular and/or pleural infltration. The solid and micropapillary subtypes are associated with poor prognosis, but their responsiveness to adjuvant chemotherapy has improved compared with acinar or papillary predominant tumors in surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma patients, based on disease-free survival and specifc disease-free survival.

Fig. 10 Chest CT

The grading system for lung adenocarcinoma has not been established. The IASLC pathology panel analyzed a multi-institutional study involving multiple cohorts of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinomas. A cohort of 284 stage I pulmonary adenocarcinomas was used as a training set to identify histologic features related to patient outcomes [22]. The best model was composed of a combination of predominant plus high-grade histologic pattern with a cutoff of 20% for the latter. The model consists of the following: grade 1, lepidic predominant tumor; grade 2, acinar or papillary predominant tumor, both with no or less than 20% of high-grade patterns; and grade 3, any tumor with 20% or more of high-grade patterns (solid, micropapillary, cribriform, and complex gland) [22]. The grading system is practical and prognostic for invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma (IPA). Based on the grading system, Hou et al. [23] retrospectively analyzed 926 Chinese patients with completely resected stage I IPAs and classifed them into three groups (grade 1, n = 119; grade 2, n = 431; grade 3, n = 376). In the multivariable analysis, the proposed grading system was independently associated with recurrence and death. Among patients with stage IB IPA (N = 490), the proposed grading system identifed patients who could beneft from adjuvant chemotherapy but who were undergraded by the adenocarcinoma classifcation. The novel grading system not only demonstrated prognostic signifcance in stage I IPA but also provided clinical value for guiding therapeutic decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy.

3.5 Case 5

A 35-year-old woman found a lung lesion for 10 days on physical examination.

Chest CT: A nodule in the left upper lung lobe (Fig. 11).

[Diagnosis] Lepidic adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a mixed GGO nodule in the upper lobe of left lung with well-defined interface. Patient underwent left upper lobectomy, the lesion

S. Zhang

was approximately 1.4 × 1.2 × 1.0 cm, and the final diagnosis was lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma.

[Analysis] According to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classifcation, the lepidic predominant pattern consists of three subtypes: AIS, MIA, and nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma. Lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma (LPA), a non-mucinous entity, is defned as a predominant lepidic growth but with at least one focus of invasion measuring >5 mm. Any lepidic predominant tumors with lymphatic, vascular, pleural invasion, or tumor necrosis were diagnosed as lepidic predominant invasive tumors rather than AIS or MIA, regardless of the degree of invasion.

On CT, LPA can be shown as a part-solid nodule with variable proportions of ground-glass and solid components. Ko et al. [24] investigation showed that the mean solid to ground-glass component volume ratio for LPA was 14.5%, signifcantly higher than 8.2% in AIS/MIA. Lee et al. [25] retrospectively investigated the differentiating CT features between LPA and preinvasive lesions appearing as GGNs in 253 patients. They found that LPA is more likely to demonstrate a lobulated border and pleural retraction than the preinvasive lesions. In pure GGNs, preinvasive lesions were signifcantly smaller and more frequently non-lobulated than IPAs. The optimal cutoff size for preinvasive lesions was <10 mm. In part-solid GGNs, preinvasive lesions can be accurately differentiated from IPAs by the smaller lesion size, smaller solid proportion, nonspiculated margin, and non-lobulated border.

Several studies have demonstrated that the prognosis of LPA was more favorable. Yoshizawa et al. [26] reported a fve-year survival rate of 90%. In 2014, Kadota et al. [27] retrospectively studied 1038 patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Tumors were classifed according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classifcation: 2 were AIS, 34 MIA, and 103 LPA. Patients with LPA had an overall fve-year recurrence rate of 8% compared with 19% in those with non-lepidic predominant tumors. The risk of recurrence varied based on the proportion of lepidic subtype present. Patients with >50% lepidic pattern tumors experienced no

11 Chest CT

recurrences (n = 84), those with >10% to 50% lepidic pattern tumors had an intermediate risk for recurrence (n = 344; 12%), and those with ≤10% lepidic pattern tumors had the highest risk (n = 610; 22%). Most patients with LPA who experienced a recurrence had potential risk factors, including sublobar resection with close margins (≤0.5 cm; n = 2), 20% to 30% micropapillary component (n = 2), and lymphatic or vascular invasion (n = 2).

Cox et al. [28] studied the association of extent of lung resection, pathologic nodal evaluation, and survival for patients with clinical stage I lepidic adenocarcinoma. Of the 1991 patients, 447 underwent sublobar resection and 1544 underwent lobectomy. Among patients who underwent lobectomy, 6% (n = 92) were upstaged because of positive nodal disease, with a median of seven lymph nodes sampled. In a multivariable analysis of a subset of patients, lobectomy was no longer independently associated with improved survival when compared with sublobar resection including lymph node sampling. They concluded that surgeons treating stage I lung adenocarcinoma patients with lepidic features should cautiously utilize sublobar resection rather than lobectomy, and they must always perform adequate pathologic lymph node evaluation including lymph node sampling.

Maurizi et al. [29] evaluated the role of a systematic lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing surgery for clinical stage I lung LPA. Only patients (n = 98) undergoing lobectomy or sublobar resection associated with systematic hilarmediastinal nodal dissection were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Resection was lobectomy in 77.6% (76/98) and sublobar in 22.4% (n = 22).

All the resections were complete (R0). Histology was LPA in 85 cases and MIA in 13 cases. At pathologic examination, N0 was confrmed in 78 patients (79.6%), while N1 in 12 (12.2%) and N2 in 8 (8.2%). At a median follow-up of 45.5 months, 26.5% of patients relapsed. The 5-year disease-free survival was 98.6% for stage I, 75% for stage II, and 45% for stage III. A complete nodal dissection can reveal occult nodal metastases in LPA patients and can improve the accuracy of pathologic staging. N1/N2 disease is a negative prognostic factor for this histology. A systematic lymph node dissection should be considered even in this setting.

3.6 Case 6

A 38-year-old man found a lung lesion for 2 months on physical examination. Chest CT: A nodule in the right lower lung lobe (Fig. 12).

[Diagnosis] Acinar adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows an irregular nodule in the lower lobe of right lung with a prominent retraction of the adjacent fssure, favoring the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Lobectomy proved the malignant nature, showing an acinar adenocarcinoma.

[Analysis] Histopathologically, acinarpredominant adenocarcinoma consists mainly of glands, which are round to oval shaped with a central luminal space surrounded by tumor cells.

Fig.

S. Zhang

The neoplastic cells and glandular spaces may contain mucin. It may be diffcult to distinguish AIS with collapse from the acinar pattern. Invasive acinar adenocarcinoma is considered when the alveolar architecture is lost and/or myofbroblastic stroma is present. Acinar-predominant adenocarcinoma is probably the most prevalent subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, accounting for 30%–40% of all invasive adenocarcinoma cases in some series. Duhig et al. [30] investigated 145 stage I adenocarcinoma cases. They found that the acinar pattern was the most common predominant architecture (44.4%), followed by papillary (22.8%) and solid (25.5%). There is no pure acinar pattern, but pure lepidic, papillary, and solid patterns were recorded. Warth et al. [31] evaluated 674 resected pulmonary adenocarcinoma cases. 248 cases (36.8%) were solid, followed by 207 (30.6%) acinar, 101 (15%) papillary, 55(8.2%) micropapillary, 35 (5.2%) lepidic, and 28 (4.2%) cribriform predominant.

Cribriform growth pattern is regarded as a variant of acinar adenocarcinoma and was frst reported in lung cancer in 1978. The term cribriform is derived from the Latin cribrum (for “sieve”), which is defned by invasive back-toback fused tumor glands with poorly formed glandular spaces lacking intervening stroma or invasive tumor nests of tumors cells that produce glandular lumina without solid components [30, 31]. Compared with common acinar pattern (tubular glands), cribriform growth pattern is associated with more aggressive histopathological structures, higher risk of recurrence, and

shorter postoperative survival. These features are similar to solid or micropapillary adenocarcinoma. Cribriform growth pattern has been considered as a new pathologic subtype of lung adenocarcinoma.

3.7

Case 7

A 52-year-old man found a lung lesion on physical examination.

Chest CT: A lesion in the right middle lung lobe (Fig. 13).

[Diagnosis] Papillary adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a 3.5 × 2 cm solid mass in the middle lobe of right lung with lobulated margins (red arrow) and internal vascular thickening (white arrow). Lobectomy revealed papillary predominant adenocarcinoma.

[Analysis] The Fleischner Society glossary of terms defnes a lesion <3 cm in size as a nodule, whereas a lesion larger than 3 cm is referred to as a mass. Papillary predominant adenocarcinoma consists of a growth of glandular cells along central fbrovascular cores. The peak incidence of papillary adenocarcinoma patients ranges from 50 to 60 years old with a proneness to the female. The histological subtype in adenocarcinoma signifcantly correlated with the prognosis. Dong et al. [32] showed the 5-year survival rate of pap-

Fig. 12 Chest CT

illary predominant adenocarcinoma was 61.50% based on analyzing 226 Chinese papillary predominant adenocarcinoma patients. Sakurai et al. [33] retrospectively analyzed 2004 papillary adenocarcinoma patients, and the 5-year overall survival rate was 72.9%. Zhang et al. [34] retrospectively analyzed 3391 patients with primary pulmonary papillary predominant adenocarcinoma. Older age, larger lesions, lymph node invasion, distant metastases, and poor pathological differentiation are correlative with poor prognosis. Surgical intervention is benefcial for obtaining favorable prognosis. Chemotherapy or radiotherapy has no signifcant effects on patient survival.

The mean doubling time of tumors theoretically refects the exponential growth of tumor cells and aids in predicting the likelihood of malignancy in pulmonary lesions. Henschke et al. [35] demonstrated that the volume dou-

bling time (VDT) of lung cancer varies according to the lung cancer subtypes and CT features. Adenocarcinoma was the most frequent cell type (50%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (19%), small cell carcinoma (19%), and cancers of other cell types (12%). The distribution of VDT by cell type was as follows: small cell carcinomas (median, 43 days), large cell/ neuroendocrine carcinomas (median, 82 days), squamous cell carcinomas (median, 88 days), adenocarcinomas presenting with solid nodules (median, 140 days), and adenocarcinomas manifesting as subsolid nodules (median, 251 days). Park et al. [36] investigated differences in VDT between the predominant histologic subtypes of primary lung adenocarcinomas and to assess the correlation between VDT and prognosis. Among 268 patients, there were 30 lepidic, 87 acinar, 109 papillary, and 42 solid or micropapillarypredominant subtypes. The median VDT was

Fig. 13 Chest CT

529 days for lung adenocarcinomas and 229 days for solid or micropapillary subtypes. Solid lesions (VDT, 248 days) had shorter VDTs than subsolid lesions (part-solid lesions, 665 days; non-solid lesions, 648 days). VDT (<400 days) was an independent risk factor for poor disease-free survival (DFS) and higher TNM stage.

3.8

Case 8

A 60-year-old woman found a lung lesion on physical examination.

Chest CT: An irregular lesion in the right upper lung lobe (Fig. 14).

[Diagnosis] Micropapillary adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 14 Chest CT

S. Zhang

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a lesion of 2.5 cm in diameter in the upper lobe of right lung with irregular shape, lobulated margins, bubble-like lucencies, pleural tags, and internal vascular distortion. She underwent right upper lobectomy. Specimens of cancer tissues showed adenocarcinoma with acinar (70%), invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (20%), and micropapillary (10%) components, with visceral pleural invasion and peribronchial lymph node metastases (2/2).

[Analysis] Micropapillary-predominant adenocarcinoma has a unique growth pattern consisting of tumor cells growing in papillary tufts that lack fbrovascular cores, and is associated with a higher degree of aggressiveness. Micropapillary pattern (MPP) was frst reported by McDivitt et al. [37] in breast carcinoma in 1982, and since then MPP has been reported in several other organs, including the urinary bladder and ovary. MPP was frst reported in lung adenocarcinoma by Silver and Askin in 1997 [38]. They stated that 74% of papillary adenocarcinomas showed the MPP. Amin et al. [39] later studied 35 cases of primary lung adenocarcinoma with a micropapillary component. They found that MPP was not associated with any particular histologic subtype of lung adenocarcinoma. 33 of 35 patients (94%) developed metastases, primarily in the lymph nodes (26) and lung (17). Most metastases had a prominent micropapillary component, irrespective of the extent of the micropapillary carcinoma component in the primary lung tumor. They emphasized the importance of recognition of this histologic pattern, as those patients may have a higher risk of recurrence and thus require a close follow-up. Some studies further confrmed that smokers, lymphovascular invasion, visceral pleural invasion, and the presence of lymph node and intrapulmonary metastases are more frequently observed in MPP histologic subtype.

Micropapillary-predominant adenocarcinoma has been reported to have a poor prognosis with a tendency toward recurrence and metastasis. Tsubokawa et al. [40] retrospectively examined 347 consecutive patients with clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma who underwent complete resection. Patients with a higher ratio of MPP

or papillary predominant subtypes have worse survival. Nitadori et al. [41] reported that the micropapillary histological subtype is a risk factor for recurrence after sublobar resection. Most recurrences (63.4%) were locoregional; micropapillary component of 5% or greater was statistically signifcantly associated with increased risk of local recurrence when the surgical margin was less than 1 cm. Sublobar resection may be insuffcient for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma with micropapillary components because of the associated higher incidence of locoregional recurrence. Yoshida et al. [42] found that adenocarcinoma with a micropapillary component was more frequent in solid nodules (17.8%) than in either ground-glass nodules (1.5%) or part-solid nodules (5.3%) on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). In multivariate analysis, the HRCT fnding was the only preoperative factor associated with a micropapillary component. Dai et al. [43] investigated the relationship between lymph node micrometastasis and histologic patterns of adenocarcinoma. Micropapillary component had been proven to be an independent predictor of increased frequency of micrometastasis. In micropapillary-positive patients, the presence of micrometastasis was correlated with a higher risk of locoregional recurrence rather than distant recurrence. Watanabe et al. [44] investigated the impact of MPP on the timing of postoperative recurrence using hazard curves. They found that patients with MPP retained a high risk of early postoperative recurrence, and risk of recurrence persisted over the long term. Even after complete resection in stage I lung adenocarcinoma patients, micropapillary component is still correlated with a poor prognosis.

As partial lung resection is associated with a poor prognosis in adenocarcinoma with micropapillary component, lobectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended.

3.9 Case 9

A 51-year-old man found a lung lesion on physical examination.

Chest CT: An oral nodule in the right lower lung lobe (Fig. 15).

[Diagnosis] Lung adenocarcinoma.

[Diagnosis Basis] The transverse CT scan shows a regular nodule in the lower lobe of right lung with smooth cavity. He underwent right lower lobectomy. The lesion was approximately 2.5 × 1.8 × 1.5 cm, diagnosed as invasive adenocarcinoma with micropapillary (50%), solid (40%), and acinar (10%) components, with necrosis, spread through air spaces, and lymph node metastases.

[Analysis] Tumor invasion in lung adenocarcinoma is defned as infltration of stroma, blood vessels, or pleura. According to the 2015 WHO classifcation, tumor spread through air spaces (STAS) is defned as micropapillary clusters, solid nests, and/or single cancer cells spreading within air spaces beyond the edge of the main tumor. STAS was established as a new invasive pattern of adenocarcinoma. This concept is based on the fact that normal lung anatomy contains air

spaces surrounded by the capillary network in the alveolar interstitium. The existence of mechanical forces, ranging from the inherent high fow velocities to the physics of breathing, to mechanical palpation of the surgeon during surgery, can certainly lend themselves to detach tumor clusters. These are usually identifed within tumors, but are not identifed as STAS until the tumor clusters appear outside the tumor periphery.

Prior to the defnition of STAS, Shiono et al. [45, 46] in 2005 indicated aerogenous spreads with foating cancer cell clusters (ASFC) in cases with pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer, and ASFC is unfavorable prognostic features. In 2013, Onzato et al. [47] proposed the concept of tumor islands, which was defned as a detached collection of tumor cells within alveolar spaces separated from the main tumor mass by a distance of at least a few alveoli. Tumor islands may be another pattern of tumor infltration into the lung parenchyma. Lung adenocarcinomas with tumor islands were more likely to occur in smok-

Fig. 15 Chest CT

S. Zhang

ers, exhibiting higher nuclear grade and a solid or micropapillary growth pattern, and harboring KRAS mutations. Tumor islands were signifcantly associated with a worse recurrence-free survival. Tumor islands seem to be a visual description of tumor cell clusters around the main tumor through STAS. If STAS is a dynamic process of tumor cell proliferation, then tumor islands can be regarded as an intuitive manifestation of tumor cells through STAS.

Some studies applied divergent defnitions of STAS and/or related morphological features. In 2015, Kadota et al. [48] frst suggested the possibility of STAS being a new pattern of invasion and defned it as the spread of tumor cells (as micropapillary structures, solid nests, or single cells) within air spaces beyond the edge of the primary tumor. They reviewed 411 resected small (less than or equal to 2 cm) stage I lung adenocarcinomas. STAS was observed in 155 cases (38%), and tumor cells were observed over 1 cm away from the edge of the tumor. STAS is usually found in the frst alveolar layers close to the tumor but occasionally can be found more than 50 alveolar spaces away from the main tumor. They reported that lymphovascular invasion and high-grade morphologic pattern in main tumors were more frequently identifed in STAS-positive tumors than in STAS-negative tumors and the presence of STAS is a signifcant risk factor of recurrence in small lung adenocarcinomas treated with limited resection. Warth et al. in 2015 [49] defned STAS as a detachment of small solid cell nests (at least 5 tumor cells) <3 alveolae away from the main tumor mass as limited STAS and tumor cell nests>3 alveolae away from the main tumor mass as extensive STAS. In the series of 569 resected pulmonary adenocarcinomas, limited (21.6%) or extensive (29%) STAS was present in roughly half of all adenocarcinomas. Tumors with STAS were much more prevalent in male sex, lymph node and distant metastasis, tumor stage, and high-grade histological patterns, and showed lower rates of EGFR but higher rates of BRAF mutations. The presence of STAS was associated with signifcantly reduced recurrencefree survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) at any stage. In 2016, Morimoto et al. [50] proposed

the concept of free tumor clusters (FTCs). They defned it to be a group of more than 3 small clusters containing <20 nonintegrated micropapillary tumor cells that were spreading within air spaces, >3 mm apart from the main tumor. The FTC does not contain solid nests or single cells. Coexistence of FTCs resulted in a further negative impact on postoperative prognosis among micropapillary component positive adenocarcinomas. In 2017, Uruga et al. [51] assessed semi-quantitatively small (≤2 cm) stage I lung adenocarcinomas surgically resected in the most prominent area as no STAS, low STAS (1–4 single cells or clusters of STAS), or high STAS (≥5 single cells or clusters of STAS). They found that one-third of resected small adenocarcinomas had high STAS, which was predictive of worse recurrence-free survival. Dai et al. [52] defned STAS as tumor cells observed within air spaces in the surrounding lung parenchyma beyond the edge of the main tumor. STAS was classifed into three morphologic subtypes: single cells, micropapillary clusters, and solid nests. STAS could be considered as a factor in a staging system to predict prognosis more precisely, especially in lung adenocarcinomas larger than 2–3 cm. In 2018, Shiono et al. [53] assessed the prognostic impact of STAS in 329 patients with a sublobar resection for stage IA lung cancer versus 185 patients with a lobectomy. STAS is a prognostic factor of poor outcomes for sublobar resection in patients with lung cancer. Terada et al. [54] in 2019 showed that STAS invasion pattern was a signifcant risk factor for recurrence even in stage III (N2) adenocarcinoma.

STAS as an independent pathologic entity rather than an artifact caused by spreading through a knife surface is still controversial. Artifacts originate from loose tissue fragments in the lung. The concept of spread through a knife surface (STAKS) was frst introduced by Thunnissen et al. [55], who pointed out that tumor cells could spread into alveolar spaces iatrogenically by the knife during pathological resection. Blaauwgeers et al. [56] prospectively investigated tumor clusters in tissue blocks. The frst cut was made with a clean knife; the second cut was made in a parallel plane to the frst. They

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

reciprocal embassy complained of frontier quarrels, as is always the case in such circumstances. In 1512 Vasili informed Sigismund that it had come to his ears that the voyevods of Vilna and Trotski had seized Helen and held her captive—which does not appear at all improbable when the unruliness of the Lithuanian lords is borne in mind—Sigismund denied the fact. That Helen officially received various rights, for instance that of a tribute or tax from the town of Bielsk, also does not prove that her position was a very advantageous one, for this was worth nothing more than other official favours In 1513 Helen died and the metropolitan of Kiev was sent for to officiate at her funeral; thus this victim of political calculations left the scene. Helen herself, as far as can be judged from her correspondence with her father and brother, was possessed of considerable tact and energy.

At last a reason for beginning war presented itself; it became known at Moscow that the incursions made by the Crimeans on the Russian frontier territories in 1512 were the result of a secret treaty that had been concluded between Sigismund and Mengli Girai, by which the king had promised to pay the khan a yearly sum of 15,000 ducats to attack his enemies. Having sent Sigismund a declaration of war, Vasili began his warlike preparations. The time was well chosen. In 1511 Albrecht of Brandenburg had been chosen as Prussian grand master, and although he was a nephew of the Polish king he refused to acknowledge himself as his vassal, which he was obliged to do by the Treaty of Thorn; the emperor and the estates of the empire declared themselves for the grand master Advised by Glinski, Vasili had entered into relations with the emperor as early as 1508, but the treaty between them was only concluded in 1514.

Without waiting for the termination of these negotiations, the grand prince assembled an army and in December, 1512, took the field. He marched against Smolensk and having besieged it unsuccessfully, returned in March, 1513. His second expedition, from June until November of the same year, was also unsuccessful, but in the third (June, 1514), Smolensk was at last captured. Vasili made a triumphal entry into the town, being received with an address of

[1514-1518 � � ]

welcome by the bishop of Smolensk. He confirmed the rights that had been given to its inhabitants by the Lithuanian government; those in the Lithuanian service who did not desire to remain under him he sent back to Lithuania, and he appointed Prince V. V. Shuiski, governor of Smolensk. After the submission of Smolensk the prince of Mstislavl also submitted to the grand prince. Sigismund himself hastened to the deliverance of Smolensk. Glinski, probably dissatisfied because Smolensk had not been given to him, entered into secret intercourse with him. Learning of this treachery Vasili ordered Glinski to be brought in fetters to Moscow and sent a voyevod against the king; the king himself remained at Borissov and sent Constantine Ostrozhski to meet the Moscow troops.

The Russian voyevods, Tcheliadin and Prince Michael Golitza met Ostrozhski at Orsha on the Dnieper and sustained a terrible defeat. The fidelity of the boyars of Smolensk and of the bishop himself wavered and they entered into communication with Sigismund; but the burghers informed Shuiski of this treachery, and it was only the terribly energetic measures taken by him that preserved Smolensk for Russia: he ordered all the traitors except the bishop to be hanged on the walls of the city, the presents that had been given them by the sovereign to be suspended round the neck of each one. The assault on Smolensk was unsuccessful, and the war was afterward carried on feebly, which is explained by the exhaustion of Moscow after the battle of Orsha and the probable reluctance of the Lithuanian nobility to take an active part in it. After this Sigismund instigated the Tatars against Russia, in particular those of the Crimea, where in 1515 Mengli Girai had been succeeded by Muhammed Girai, who, notwithstanding his relations with Moscow, made in 1517 an attack on Tula and was repulsed. On his side Vasili strengthened his relations with Albrecht who kept his vassal, the grand master of Livonia, in check. However while Albrecht hesitated and demanded money, Vasili required that he should begin to act. The emperor, instead of beginning the war, as had been at first supposed he would do, offered his mediation, and it was with this aim in view that in 1517 the famous baron Sigismund Herberstein came to Moscow Polish ambassadors also came; but with the news of their coming, Moscow also learned of the attack on Opochka by the Lithuanian

troops and their repulse, and when Vasili heard of its failure he allowed the ambassadors access to him. The negotiations however came to nothing. The Moscow sovereign demanded Kiev and other towns, and the Lithuanian king refused to give up Smolensk. The death of Maximilian (1519) put an end to the imperial mediation; anyhow the emperor had not wished to give any real assistance: “It is not well”—he wrote to the grand master Albrecht—“to drive out the king, and make the czar of all Russia great.”

In 1518 Albrecht again asked for money; the grand prince agreed, and at the former’s request sent a notification of his alliance with him to the French king, Francis I—the first instance of intercourse between Russia and France. In answer to a fresh embassy from Albrecht bringing information of an invitation from the pope to join an alliance against the Turks, which Albrecht would not enter into without the grand prince’s consent, an ambassador was sent to Koenigsberg from Moscow, who was received with the highest honours by the grand master. But Albrecht’s help was not very efficacious; he was soon obliged to conclude a treaty with King Sigismund by which he acknowledged himself his vassal, in return for which he obtained Prussia as an hereditary possession, laid aside his title of grand master, and assumed a new title with his new faith, that of duke of Prussia.

The war at that time was limited to incursions, and Vasili Ivanovitch had even decided to seek peace; but the envoys that came would not make any concessions, only letting negotiations drag on in the hope of some event coming to their assistance; in this manner the war was prolonged until the Lent of 1521, when negotiations were to be again renewed; however they were not opened: in Kazan reigned Sahib Girai, the brother of Muhammed Girai, and they both threatened Moscow, indeed the former advanced as far as Moscow itself (1521). The devastations of the Tatars weakened Russia for a time and the negotiations with Lithuania were renewed; although a lasting peace was not concluded, a truce was continued for five years without the exchange of prisoners, and by this truce Smolensk remained to Russia. In 1526, through the medium of the emperor’s

[1521-1523 �.�.]

envoys, negotiations for a definitive peace were again opened, but Smolensk was an obstacle, neither side consenting to give up the town which was regarded as the key to Kiev. Smolensk was treated in the same manner as the other territories annexed; the inhabitants were transferred to Moscow as had been done with the inhabitants of Pskov and Novgorod, and it was for this reason that Smolensk stood by Moscow in 1612.

WARS WITH THE TATARS

Besides the relations with Lithuania, the relations with the Tatars constituted the chief problem of the reign of Vasili Ivanovitch. At his accession his first enterprise was to send against Kazan an army, amongst the leaders of which was his brother Dmitri; the siege of Kazan (1506) was unsuccessful, nevertheless in 1507 Muhammed Amin sent a letter to the grand prince with proposals of peace. Intercourse with the Crimea originally bore the same character as in the time of Ivan; a difference was however soon observable; the Crimea had no longer anything to fear from the remnants of the Golden Horde, and the Crimeans were therefore ready to make friends with whatever state would give them most. “Intercourse between the Crimea and the states of Moscow and Lithuania”—justly remarks Soloviov—“assumed the character of a bribery of robbers.”

Such being the condition of affairs, it is not surprising that in spite of the confirmation of the treaty concluded between Ivan and Mengli Girai, the Tatars should have begun their attacks. In 1507 they were defeated at the Oka, and in consequence of this, envoys were sent demanding presents, the liberation of Abdul Letiv, former czar of Kazan and stepson of Mengli Girai, and asking for assistance against Astrakhan. Vasili Ivanovitch liberated Abdul Letiv, gave him the town of Iuriev, and by an oath of alliance obliged him to promise faithfully to serve the czar, not to have relations with his enemies, not to permit his servants to plunder on the roads or insult the churches, to live at peace with the other princes, not to wage war against Kazan without permission, and not to leave the confines of the state of Moscow. In 1515 Mengli Girai died, and his son Muhammed Girai,

who succeeded him, demanded from Vasili Ivanovitch not only the cession to the Polish king of Smolensk, at the acquisition of which without his knowledge he was much incensed, but also of those towns which had been taken by Ivan. After long delays and much trouble, many insults and, of course, presents, an oath of alliance was obtained of Muhammed Girai in 1519, but meanwhile the attacks of the Crimeans continued. The son of Muhammed Girai, the czarevitch Bogatir, laid waste the borderland of Riazan; and in 1517 the Tatars—notwithstanding the Russian offer of Koshira, bordering on the steppes, to Ahmed Girai, brother of the khan—penetrated as far as Tula, where they were repulsed.

The grand prince then proposed to the council (douma) the question whether relations with the Crimea should be maintained, and it was decided that they must be maintained in order to prevent the rupture from becoming an open one. Meanwhile in 1518 Muhammed Amin of Kazan died, and Abdul Letiv, who had previously been czar, died a month after him; at the request of the inhabitants of Kazan a czar was named from Moscow in 1519—Shig Alei, a prince of Astrakhan, and descendant of the czars of the Golden Horde. The Crimean khan was greatly dissatisfied at this choice of one whose family was at an eternal enmity with his own. Shig Alei remained in Kazan until 1521 when the inhabitants, dissatisfied with him, formed a conspiracy and invited Sahib Girai, brother of Muhammed Girai, to come and rule over them. Having established his brother on the throne of Kazan, Muhammed Girai advanced towards Moscow The grand prince, warned too late by his well-wishers at Azov, could not take the necessary measures, and left Moscow, confiding the defence of the city to the boyars and baptised Tatar prince, Peter; they entered into negotiations with the enemy and paid him a ransom. The heroic defence of Pereiaslavl in Riazan by Khabar Simski somewhat softened the mournful impression of this calamity, which was augmented by the fact that Sahib Girai had at the same time devastated the territories of NijniNovgorod and Vladimir. The khan was preparing to repeat his expedition, and the grand prince himself took the field in expectation of his coming, but he never came.

Another undertaking then occupied Muhammed Girai: in 1523 he joined the Nogaians and conquered Astrakhan. There the Nogaians quarreled with him and killed him; his place was taken by Saidat Girai, who sent the grand prince the following conditions for an alliance: To give him 60,000 altines (an ancient coin of the value of three kopecks) and to make peace with Sahib Girai; but Vasili seeing the devastation of the Crimea both by the Nogaians and the Cossacks of Dashkevitch, who had hitherto acted in concert with the Crimeans, rejected these proposals. To avenge himself on Sahib Girai, who had massacred the Russians in Kazan where blood flowed like water, Vasili himself came to the land of Kazan (1523), devastated it, and made the inhabitants prisoners; on his return he built the town of Vasilsursk. When in 1524 a great army was sent from Moscow to Kazan, Sahib Girai fled to the Crimea, and the inhabitants of Kazan proclaimed his young nephew Sava Girai as czar; the expedition from Moscow was however unsuccessful, although the people of Kazan, who had lost their artillery engineer, sued for peace.

THE GROWING POWER OF RUSSIA

Their dependence upon the grand prince was irksome to the inhabitants of Kazan; fresh disputes arose, Vasili brought on an intrigue, and Kazan soon asked for a new czar. Vasili named Shig Alei, who was at that time in Nijni, but when the people of Kazan entreated that his brother Jan Alei (Enalei), who then ruled over Kassimov, should be nominated in his stead, Vasili consented. Jan Alei was established at Kazan and Shig Alei was given Koshira, but as he did not keep the peace, and entered on negotiations with Kazan, he was exiled to Belozero. Disturbances took place in the Crimea; Saidat Girai was overthrown by Sahib, but the relations between the Crimea and Moscow remained the same; the Tatars continued to make insignificant raids and obtained presents. Nevertheless the Tatar messengers began to be less respectfully treated at Moscow: “Our messengers”—wrote Sahib Girai —“complain that thou dost not honour them as of old, and yet it is thy duty to honour them; whoever wishes to pay respect to the master,

throws a bone to his dog.” Of other diplomatic relations those with Sweden and Denmark bore the character of frontier disputes; the intercourse with the pope was entered upon through the desire of the latter to convert Russia to Catholicism and incite her to war against Turkey. The intercourse with the latter power had no particular results. It is curious to observe that at this period relations were entered into with India; the sultan Babur sent ambassadors (1533) with proposals of mutual commercial dealings.b

Each day added to the importance of Russia in Europe. Vasili exchanged ambassadors with the eastern courts and wrote to Francis I the great king of the Gauls. He numbered among his correspondents Leo X, Clement VII, Maximilian, and Charles V; Gustavus Vasa, founder of a new dynasty; Sultan Selim, conqueror of Egypt and Soliman the Magnificent. The grand mogul of the Indes, Babur, descendant of Timur, sought his friendship. The autocracy affirmed itself each day more vigorously. Vasili governed without consulting his council of boyars. “Moltchi, smerd!” (Hold, clown!) said he to one of the nobles who dared to raise an objection. This growing power manifested itself in the splendour of the court, the receptions of the ambassadors displaying a luxury hitherto unprecedented. Strangers, though not in large numbers, continued to come to Moscow, of whom the most illustrious was a monk from Mount Athos, Maxine the Greek.e

[1533 �.�.]

MAXINE THE GREEK

In the early days of his reign, when Vasili was examining the treasures left to him by his father, he perceived a large number of Greek church books which had been partly collected by former grand princes and partly brought to Moscow by Sophia, and which now lay covered with dust in utter neglect. The young sovereign manifested the desire of having a person who would be capable of looking them over and of translating the best of them into the Slavonic language. Such a person was not to be found in Moscow, and letters were written to Constantinople. The patriarch, being desirous of pleasing

the grand prince, made search for such a philosopher in Bulgaria, in Macedonia and in Thessalonica; but the Ottoman yoke had there crushed all the remains of ancient learning and darkness and ignorance reigned in the sultan’s realms. Finally it was discovered that in the famous convent of the Annunciation on Mount Athos there were two monks, Sabba and Maxine, who were learned theologians and well versed in the Slavonic and Greek languages. The former on account of his great age was unable to undertake so long a journey, but the latter consented to the desire of the patriarch and of the grand prince.

It would indeed have been impossible to find a person better fitted for the projected work. Born in Greece, but educated in the enlightened west, Maxine had studied in Paris and Florence, had travelled much, was acquainted with various languages, and was possessed of unusual erudition, which he had acquired in the best universities and in conversation with men of enlightenment. Vasili received him with marked favour. When he saw the library, Maxine, in a transport of enthusiasm and astonishment, exclaimed: “Sire! all Greece does not now possess such treasures, neither does Italy, where Latin fanaticism has reduced to ashes many of the works of our theologians which my compatriots had saved from the Mohammedan barbarians.” The grand prince listened to him with the liveliest pleasure and confided the library to his care. The zealous Greek made a catalogue of the books which had been until then unknown to the Slavonic people. By desire of the sovereign, and with the assistance of three Muscovites, Vasili, Dmitri and Michael Medovartzov, he translated the commentary of the psalter. Approved by the Metropolitan Varlaam and all the ecclesiastical council, this important work made Maxine famous, and so endeared him to the grand prince that he could not part with him, and daily conversed with him on matters of religion. The wise Greek was not, however, dazzled by these honours, and though grateful to Vasili, he earnestly implored him to allow him to return to the quiet of his retreat at Mount Athos: “There,” said he, “will I praise your name and tell my compatriots that in the world there still exists a Christian czar, mighty and great, who, if it pleases the Most High, may yet deliver us from the tyranny of the infidel.” But Vasili only replied by fresh signs of

favour and kept him nine years in Moscow; this time was spent by Maxine in the translation of various works, in correcting errors in the ancient translations, and in composing works of piety of which more than a hundred are known to us.

Having free access to the grand prince, he sometimes interceded for the noblemen who had fallen in disgrace and regained for them the sovereign’s favour. This excited the dissatisfaction and envy of many persons, in particular of the clergy and of the worldly-minded monks of St. Joseph, who enjoyed the favour of Vasili. The humbleminded metropolitan Varlaam had cared little for earthly matters, but his successor, the proud Daniel, soon declared himself the enemy of the foreigner. It began to be asked: “Who is this man who dares to deface our sacred church books and restore to favour the disgraced boyars?” Some tried to prove that he was a heretic, others represented him to the grand prince as an ungrateful calumniator who censured the acts of the sovereign behind his back. It was at this time that Vasili was divorced from the unfortunate Solomonia, and it is said that this pious ecclesiastic did really disapprove of it; however we find amongst his works a discourse against those who repudiate their wives without lawful cause. Always disposed to take the part of the oppressed, he secretly received them in his cell and sometimes heard injurious speeches directed against the sovereign and the metropolitan. Thus the unfortunate boyar Ivan Beklemishef complained to him of the irascibility of Vasili, and said that formerly the venerable pastors of the church had restrained the sovereigns from indulging their passions and committing injustice, whereas now Moscow no longer had a metropolitan, for Daniel only bore the name and the mask of a pastor, without thinking that he ought to be the guide of consciences and the protector of the innocent; he also said that Maxine would never be allowed to leave Russia, because the grand prince and the metropolitan feared his indiscretions in other countries, where he might publish the tale of their faults and weaknesses. At last Maxine’s enemies so irritated the grand prince against him, that he ordered him to be brought to judgment and Maxine was condemned to be confined in one of the monasteries of Iver, having been found guilty of falsely interpreting the Holy Scriptures and the dogmas of the church. According to the opinion of

some contemporaries the charge was a calumny invented by Jonas, archimandrite of the Tchudov monastery, Vassian, bishop of Kolomna, and the metropolitan.f

PRIVATE LIFE OF VASILI IVANOVITCH; HIS DEATH

There is one event in the private life of Vasili Ivanovitch which has great importance on the subsequent course of history, and throws a clearer light on the relations of men and parties at this epoch. This event is his divorce and second marriage. Vasili Ivanovitch had first contracted a marriage in the year of his father’s death with Solomonia Sabourov; but they had no children and Solomonia vainly resorted to sorcery in order to have children and keep the love of her husband. The grand prince no longer loved her and decided to divorce her. He consulted his boyars, laying stress on the fact that he had no heir and that his brothers did not understand how to govern their own appanages; it is said that the boyars replied “The unfruitful fig-tree is cut down and cast out of the vineyard.” The sovereign then turned with the same question to the spiritual powers: the metropolitan Daniel gave his entire consent, but the monk Vassian, known in the world as Prince Vasili Patrikëiev, who, together with his father, had been forced to become a monk during the reign of Ivan because he belonged to the party of Helen, but who was now greatly esteemed by Vasili, was against the divorce and was therefore banished from the monastery of Simon to that of Joseph. Maxine the Greek and Prince Simon Kurbski were also against the divorce, and suffered for their opinion; and the boyar Beklemishev, who was on friendly terms with Maxine, was executed. Solomonia was made to take the veil at the convent of Suzdal and Vasili married Helen Vasilievna Glinski, the niece of Michael Glinski who had been liberated from prison (1526). From this marriage Vasili had two sons; Ivan (born 1530) and Iuri (born 1533). Vasili’s love for his second wife was so great that according to Herberstein he had his beard cut off to please her. Towards the end of 1533 Vasili fell ill and died on December 3rd, leaving as his heir his infant son Ivan.b

A FORECAST OF THE REIGN OF IVAN (IV) THE TERRIBLE

The rôle and the character of Ivan IV have been and still are very differently appreciated by Russian historians. Karamzin, who has never submitted his accounts and his documents to a sufficiently severe critic, sees in him a prince who, naturally vicious and cruel, gave, under restriction to two virtuous ministers, a few years of tranquillity to Russia; and who subsequently, abandoning himself to the fury of his passions, appalled Europe as well as the empire with what the historian designates “seven epochs of massacres.” Kostomarov re-echoes the opinions of Karamzin.

Another school, represented by Soloviev and Zabielin, has manifested a greater defiance towards the prejudiced statements of Kurbski, chief of the oligarchical party; towards Guagnini, a courtier of the king of Poland; towards Tanbe and Kruse, traitors to the sovereign who had taken them into his service. Above all, they have taken into account the times and the society in whose midst Ivan the Terrible lived. They concern themselves less with his morals as an individual than with his rôle as instrument of the historical development of Russia. Did not the French historians during long years misinterpret the enormous services rendered by Louis XI in the great work of the unification of France and of the creation of the modern state? His justification was at length achieved after a more minute examination into documents and circumstances.

At the time when Ivan succeeded his father the struggle of the central power against the forces of the past had changed character. The old Russian states, which had held so long in check the new power of Moscow; the principalities of Tver, Riazan, Suzdal, Novgorod-Seversk; the republics of Novgorod, Pskov, Viatka had lost their independence. Their possessions had served to aggrandise those of Moscow. All northern and eastern Russia was thus united under the sceptre of the grand prince. To the ceaseless struggles constantly breaking out against Tver, Riazan, Novgorod, was to succeed the great foreign strife—the holy war against Lithuania, the Tatars, the Swedes.

Precisely because the work of the unification of Great Russia was accomplished, the resistance in the interior against the prince’s authority was to become more active. The descendants of reigning families dispossessed by force of bribery or arms, the servitors of those old royal houses, had entered the service of the masters of Moscow. His court was composed of crownless princes—the Chouiski, the Kurbski, the Vorotinski; descendants of ancient appanaged princes, proud of the blood of Rurik which coursed through their veins. Others were descended from the Lithuanian Gedimine, or from the baptised Tatar Monzas

All these princes, as well as the powerful boyars of Tver, Riazan, Novgorod, were become the boyars of the grand prince. There was for all only one court at which they could serve—that of Moscow. When Russia had been divided into sovereign states, the discontented boyars had been at liberty to change masters—to pass from the service of Tchernigov into that of Kiev, from that of Suzdal into that of Novgorod. Now, whither could they go? Outside of Moscow, there were only foreign rulers, enemies of Russia. To make use of the ancient right to change masters was to go over to the enemy—it was treason. “To change” and “to betray” were become synonymous: the Russian word izmiyanit (third person singular of “to change”) was become the word izmiyanik (“traitor”).

The Russian boyar could take refuge neither with the Germans, the Swedes, nor the Tatars; he could go only to the sovereign of Lithuania—but this was the worst possible species of change, the most pernicious form of treason. The prince of Moscow knew well that the war with Lithuania—that state which Polish in the west, by its Russian provinces, in the east exercised a dangerous attraction over subjects of Moscow—was a struggle for existence. Lithuania was not only a foreign enemy—it was a domestic enemy, with intercourse and sympathies in the very heart of the Russian state, even in the palace of the czar; her formidable hand was felt in all intrigues, in all conspiracies. The foreign war against Lithuania, the domestic war against the Russian oligarchy are but two different phases of the same war—the heaviest and most perilous of all those undertaken by the grand prince of Moscow. The dispossessed princes, the

boyars of the old independent states had given up the struggle against him on the field of battle; they continued to struggle against him in his own court.

It was no longer war between state and state; it was intestine strife —that of the oligarchy against autocratic power. Resigned to the loss of their sovereignty, the new prince-boyars of Moscow were not yet resigned to their position as mere subjects. The struggle was thus limited to a narrower field, and was therefore the more desperate. The court at Moscow was a tilt-yard, whence none could emerge without a change of masters—the Lithuanian for the Muscovite— without treason: hence the furious nature of the war of two principles under Ivan IV.e

THE MINORITY OF IVAN IV

On the death of his father, Ivan was only three years of age. Helena, his mother, a woman unfit for the toils of government, impure in her conduct, and without judgment, assumed the office of regent, which she shared with a paramour, whose elevation to such a height caused universal disgust, particularly among the princes of the blood and the nobility. The measures which had of late years been adopted towards the boyars were not forgotten by that haughty class; and now that the infirm state of the throne gave them a fair pretext for complaint, they conspired against the regent, partly with a view to remove so unpopular and degraded a person from the imperial seat, but principally that they might take advantage of the minority of the czar, and seize upon the empire for their own ends. The circumstances in which the death of Vasili left the country were favourable to these designs. The licentiousness that prevailed at court, the absence of a strict and responsible head, and the confusion that generally took the place of the order that had previously prevailed, assisted the treacherous nobles in their treasonable projects. They had long panted for revenge and restitution, and the time seemed to be ripe for the execution of their plans.

I��� ��� T������� (1530-1584)

Amongst the most prominent members of this patrician league, were the three paternal uncles of the young prince. They made no scruple of exhibiting their feelings; and they at last grew so clamorous, that the regent, on the ground that they entertained designs upon the throne, condemned them to loathsome dungeons, where they died in lingering torments. Their followers and abettors suffered by torture and the worst kinds of ignominious punishment. These examples spread such consternation amongst the rest of the conspirators, that they fled to Lithuania and the Crimea, where they endeavoured to inspire a sympathy in their misfortunes. But the regent, whose time appears to have been solely dedicated to the worst description of pleasures, being unable to preserve herself without despotism, succeeded in overcoming the enemies whom her own conduct was so mainly instrumental in creating.

The reign of lascivious folly and wanton rigour was not, however, destined to survive the wrath of the nobles. For five years, intestine jealousies and thickening plots plunged the country into anarchy; and, at last, the regent died suddenly, having, it is believed, fallen by poison administered through the agency of the revengeful boyars. The spectacle of one criminal executing summary justice upon another, is not destitute of some moral utility; and in this case it might have had its beneficial influence, were it not that the principal conspirators had no sooner taken off the regent than they violently seized upon the guardianship of the throne.

The foremost persons in this drama were the Shuiski—a family that had long been treated with suspicion by the czars, their insolent bearing having always exposed them to distrust. Prince Shuiski was appointed president of the council of the boyars, to whom the administration of affairs was confided, and although his malignant purposes were kept in check by the crowd of equally ambitious persons that surrounded him, he possessed sufficient opportunities to consummate a variety of wrongs upon the resources of the state and upon obnoxious individuals—thus revenging himself indiscriminately for the ancient injuries his race had suffered. During this iniquitous rule, which exhibited the extraordinary features of a government composed of persons with different interests, pressing forward to the same end, and making a common prey of the trust that was reposed in their hands, Russia was despoiled in every quarter. The Tatars, freed for a season from the watchful vigilance of the throne, roamed at large through the provinces, pillaging and slaying wherever they went; and this enormous guilt was crowned by the rapacious exactions and sanguinary proscriptions of the council. The young Ivan was subjected to the most brutal insults: his education was designedly neglected; he was kept in total ignorance of public affairs, that he might be rendered unqualified to assume the hereditary power; and Prince Shuiski, in the midst of these base intrigues against the future czar, was often seen to treat him in a contemptuous and degrading manner, on one occasion he stretched forth his legs, and pressed the weight of his feet on the body of the boy. Perhaps these unexampled provocations, and the privations to which he was condemned, produced the germs of a character which was afterwards developed in such terrible magnificence, the fiend that lived in the heart of Ivan might not have been born with him; it was probably generated by the cruelties and wrongs that were practised on his youth.

In vain the Belski, moderate and wise, and the primate, influenced by the purest motives, remonstrated against the ruinous proceedings of the council. The voice of admonition was lost in the hideous orgies of the boyars, until a sudden invasion by the Tatars awakened them to a sense of their peril. They rallied, order was restored, and Russia was preserved. But the danger was no sooner over than the Shuiski

returned in all their former strength, seized upon Moscow in the dead of the night, penetrated to the couch of Ivan, and, dragging him out of his sleep, endeavoured to destroy his intellect by filling him with sudden terror. The primate, whose mild representations had displeased them, was ill-treated and deposed: and the prince Belski, who could not be prevailed upon to link his fortunes with their desperate courses, was murdered in the height of their frenzy. Even those members of their own body who, touched by some intermittent pity, ventured to expostulate, were beaten in the chamber of their deliberations, and cast out from amongst them.

Under such unpropitious auspices as these, the young Ivan, the inheritor of a consolidated empire, grew up to manhood. His disposition, naturally fierce, headstrong, and vindictive, was most insidiously cultivated into ferocity by the artful counsellors that surrounded him. His earliest amusements were the torture of wild animals, the ignoble feat of riding over old men and women, flinging stones from ambuscades upon the passers-by, and precipitating dogs and cats from the summit of his palace. Such entertainments as these, the sport of boyhood, gave unfortunately too correct a prognostic of the fatal career that lay before him. By a curious retribution, the first exercise of this terrible temper in its application to humanity fell upon the Shuiski, who certainly, of all mankind, best merited its infliction. When Ivan was in his thirteenth year, he accompanied a hunting party at which Prince Gluiski—another factious lord—and the president of the council were present. Gluiski, himself a violent and remorseless man, envied the ascendency of Shuiski, and prompted the young prince to address him in words of great heat and insult. Shuiski, astonished at the youth’s boldness, replied in anger. This was sufficient provocation. Ivan gave way to his rage, and, on a concerted signal, Shuiski was dragged out into the public streets, and worried alive by dogs in the open daylight. The wretch expiated a life of guilt by the most horrible agonies.

Thus freed from one tyranny, Ivan was destined for another, which, however, accepted him as its nominal head, urging him onward to acts of blood which were but too congenial to his taste. The Gluiski having got rid of their formidable competitor in the race of crime, now

assumed the direction of affairs. Under their administration, the prince was led to the commission of the most extravagant atrocities; and the doctrine was inculcated upon his mind, that the only way to assert authority was by manifesting the extremity of its wrath. He was taught to believe that power consisted in oppression. They applauded each fresh instance of vengeance; and initiated him into a short method of relieving himself from every person who troubled or offended him, by sacrificing the victim on the spot.

IVAN ASSUMES THE REINS OF GOVERNMENT