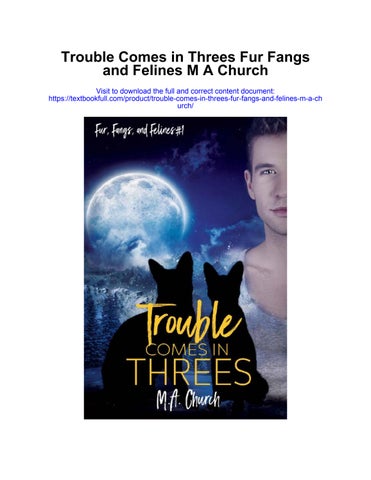

TroubleComesinThrees

Fur,Fangs,andFelines:BookOne

A snowstorm in the South—on New Year’s Eve—is a perfect recipe for a catastrophe. After two soul-crushing bad breaks, Kirk’s waiting for disaster number three to strike when, naturally, two stray cats arrive on his doorstep during the storm and decide to make themselves at home. Tenderhearted Kirk lets them stay even though there’s something decidedly odd about his overly friendly felines. Out of the punishing weather and full of tuna, Dolf and Tal are happy to be snug in Kirk’s house. But then their human goes outside for firewood and suffers a nasty fall that leaves him unconscious. Now the two cats have no choice but to reveal themselves.

Kirk wakes up to find the two kitties are actually Dolf and Tal. They’re cat shifters—and his destined mates. Being part of a feline threesome is enough for Kirk to grapple with, but soon he learns they come from a clowder that doesn’t believe humans and shifters should mix. Kirk knew those two cats would be trouble. Little does he know the real trouble lies ahead.

Acknowledgements

Alicia Nordwell, Julie Lynn Hayes, and Tali Spencer—You ladies rock. Thanks for all the well wishes and support this past year.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Trouble Comes in Threes 2nd Edition, 2019 © M.A. Church

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser or reviewer only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author, except where permitted by law.

Cover artist: Morningstar Ashley

Second Edition, Previously Published

This book has been previously published. The cover may have changed, but the title, author, and story content have not changed from the first version originally published in 2014. If you have that version in your library, please do not purchase again.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Backlist

Author Bio

To my fans who’ve stuck with me these past few years. You’re the reason I keep going.

Chapter One Dolf

“I DESPISE this place, I want you to know that,” Dolf grumbled, barely suppressing a hiss as he drove down yet another aisle hunting for a parking spot. “I must have lost my mind to even attempt to shop after Black Friday. And who was the idiot who laid out these parking lots? They’re not big enough to park a hybrid car in, much less a king cab dually truck. But then, parking this thing inside a city block takes an act of Congress.”

Tal poked Dolf in the ribs. “Stop picking on my truck.”

“Truck, ha. This thing ought to have its own zip code.” Dolf grunted in annoyance when some kid zipped into the spot he’d been eyeing. “Damn kid got my spot.”

“You have truck envy.”

“My ass.”

“And I do envy your ass, even as long as we’ve been mated.” Tal winked. “By the way, quit bitching about that kid. You see, we’re not even on the right side.” Tal pointed to the far side of the parking lot. “What we’re going to buy is on that side of the store. I don’t see the point in parking over here, then having to walk a mile to get over there. Unless, of course, you just want to.”

“You want to drive?”

“No point now. We’re here.”

Dolf checked his watch. “I bet by the time we get out of here, it’ll be five o’clock. For someone who absolutely hates driving in rush-hour traffic, you might want to rethink that last comment.”

Tal pouted, lower lip pooched out and eyes sad.

“Oh no, don’t even start with the sad, puppy dog eyes. I mean, really. Puppydogeyes?”

“You’re so mean.”

“No, sweetheart, mean would be making you ride home with your dick out and unable to touch it while I talk dirty to you.”

Tal shifted in the seat. “If memory serves, you diddo that the last time we were here. Thank goodness it was dark and you have tinted windows.”

A pleasant smile crossed Dolf’s face as he revisited the memory of his mate sprawled out in the seat. “Yup, that was a ride home worth remembering. You were begging by the time we got in the drive.” His voice had a little purr as he spoke.

“As I said: mean.”

“Hey, gotta get my kicks somehow when you drag me here.”

Dolf blew out a deep breath as he slowly made his way to the other side of the huge discount hardware store. “When we’re done, you want to grab an early dinner?” Dolf scanned the parking lot. “Gods, isn’t there something closer to the front of the store? Did I mention I hate this place?”

“At least once every five minutes, and yes, dinner sounds good. I heard Sam had his grand opening at Arches a few nights ago.”

“What a name. I love it.”

“Isn’t it? I helped finish a few things right before he opened. He took some flak about the name from some of the… well, employees who are—”

“I know what you mean.” Werecats usually lived separately from human society, but still ran businesses that hired humans. Even though they didn’t like to do that. Then Dolf scowled. “Wait, he was having trouble?”

“It was just all in good fun. He just shrugged, said he liked cats, and that’s what cats do—they arch. Want to stop by his new restaurant?”

“Yes, we’ll eat there,” Dolf said. “I hear they have great steaks. Might even have to have a beer or three after this little adventure.”

“I really don’t get why you hate coming here so much.”

“Because every time I step foot in this place, I end up spending hours here. Half the time I’m hunting someone down for assistance. I walk in, and every employee in a five-mile radius disappears.”

“I never have a problem finding someone to help.”

Well, of course Tal didn’t have any problems. Just look at that long, wavy, white-blond hair, those bright blue eyes, and that long, lean, golden, sun-kissed body. Add in the sweet, innocent look and ready smile—and people fell all over themselves to help his sexy mate.

Dolf glanced in the rearview mirror. He had the same bright blue eyes, but his jet-black hair curled loosely at the nape of his neck. Unlike Tal, most cat shifters had dark hair. Smooth, deepbronzed skin stretched over finely honed muscles. A layer of thick, dark stubble covered his jaw and framed his lips. He was the dark to Tal’s light. And as far as sweet? As head beta of his clowder and the next Alpha, there wasn’t a sweet bone in his body.

“Ah-ah!” Dolf whipped the truck into a parking spot, cackling loudly. “Right in front of the store too. How often does that happen?”

“I swear, is this like a competition—you against the parking lot gods?”

“I’m not that bad.” Dolf shut the truck off.

“Right.” Tal rolled his eyes as he climbed out.

Dolf walked around the front of the truck, waiting for Tal. “Okay, so maybe I am.”

“You are.” Tal eagerly rubbed his hands together as they walked into the store. “Man, I love this place. Okay, you said you wanted to get your dad some sort of tool for his birthday, right? Hand tools are over there.”

Dolf watched Tal stride across the store, following behind. He certainly was no follower, but in here, Tal ruled. Plus, it gave him a chance to admire that fine ass of Tal’s, which could only improve his mood.

“Ta-da. Hand tools!” Tal gestured to shelf upon shelf of tools in all different sizes and lengths. “What did you have in mind?”

“Have in mind?” Dolf stared at the shelves, his sudden good mood gone. “Are you kidding me? There’s like… millions of things here. What does half this stuff do? How many different types of hammers does a guy need to just drive in a nail?”

“It amazes me how the handyman gene skipped you. I thought this stuff was ingrained into the male DNA. You hate hardware stores, hate tools—you don’t have a clue what most of them do or even care. I just don’t get it.”

Dolf lowered his voice. “You questioning my manhood? Huh. I’ll remember that tonight when you’re screaming to come.”

Tal hunched his shoulders and his nose twitched. He discreetly sniffed the air. “Aw, goddess, I can smell your desire. Don’t do that, Dolf. Don’t make me walk around here hard.”

Dolf snickered, really wishing he could drag his mate off to a dark corner. The sweet scent of Tal’s arousal floated to him, making him need. “Then behave.”

“Deal.”

“So, help me out here.” Dolf scratched his head. “What do I get the Alph… ah, I mean the man who has everything?” Dolf wanted to smack himself in the head. He rarely slipped and said that word when not around others of his kind. From a very young age, they learned to be cautious around humans.

“Really? How did you miss the clue your dad dropped Sunday while we were having dinner with them? Didn’t you hear him talking about redoing the tile in the kitchen?”

“I did, but I had no idea what he was talking about.” Dolf trusted Tal when it came to tools. After all, that was his business.

“He all but spelled it out for you. You tuned him out when he started talking tools and renovations, didn’t you?” Tal shook his head. “What would you do without me? He wants a tile saw. If you want to spend a little extra money, we can get him one with a stand. But it’s going to cost you.”

Dolf massaged his neck. If Tal said it was going to cost, then it was really going to cost. “How much money?”

“For a good one? Upward of a thousand and over.”

“I didn’t want to spend quite that much.” Dolf scowled at the tools.

“No problem. There are some with stands that are less. Or without stands too. Is that what you want to get him?”

“Yeah, yeah, he’ll use that, won’t he? Especially since he likes the do-it-yourself projects.”

“He also knows he can call me if he needs help.”

“It certainly helps that his son-in-law owns his own construction business.” Dolf thought about it, then made up his mind. “Let’s get that. Uh, where are they?”

“I’ll show you. Come on.” Tal walked beside Dolf. “While we’re here, you want to get a new commode kit for your mom’s master bath? She’s been on your dad to fix that.”

“I know.” Dolf cut his eyes at an older man who was staring at Tal. He narrowed his eyes, a warning to the human. The other man looked away. Tal, Dolf noticed, didn’t catch the byplay. He never did. “I guess we can get that since we’re here. That’ll save Dad a trip into town.”

“The saws are on another aisle. Let’s get that picked out, and then we can get the commode kit.”

Dolf picked out the saw he wanted, then followed Tal to another aisle. His mate pointed out the different kinds, but Tal’s words had rapidly faded into a meaningless buzz. There, on the air currents in the store, was the sweetest scent. It was light and flowery, reminding him of honeysuckle. He breathed deeply, taking the scent into himself. His cock hardened immediately and his head spun. A yowl threatened to escape.

That scent… that scentwas seductive and alluring. It spoke to him, whispering things that made him need. His cat paced frantically in his mind, tail slashing madly. The need to pounce, to sink his canines in and drink that sweet, life-giving blood of his…. His gums tingled and saliva flooded his mouth.

He swallowed, then swallowed again as his head pounded, his heart rate spiking as one thought screamed through his mind: Mate! Anothermate!Where was that scent coming from? Or who? And by the goddess, why? He already had a mate. What was their goddess thinking, giving him another? But he couldn’t ignore the reaction. It had been the same when he met Tal.

A quick glance down the aisle showed a fairly tall, fortysomething human male who had a few strands of white in his short brown hair. He was muttering at commode kits. Dolf wanted to roll his eyes. Commode kits? Really? The same thing they were looking for? Their goddess must be having a high old time with this.

“Fuck,” he whispered softly. He rarely cussed, except when aroused. Nothing sent his mate whimpering faster than Dolf describing in frank detail how he planned to fuck Tal. He loved hearing Tal’s voice begging… and speaking of that, only then did he notice Tal had stopped talking. Not only had Tal stopped talking, but now he was growling. It was low, but it was a growl, a sound no human would make.

“Tal,” Dolf whispered. “Look at me, mate.”

Tal’s fists clenched, spasms shaking his arms. “That scent….”

“I know. Look at me. You’re growling, and you can’t do that here. Talise!” Dolf’s voice dropped as he snapped out Tal’s full name, power and command flowing from him. His mate was close to losing control right there in a hardware warehouse. “Stop. Now.”

Tal shuddered hard but stopped growling, his muscles relaxing. “What, what…. Dolfoon?” Tal resorted to using Dolf’s full name. He was still shaking. “Help me. I-I… that scent. How can I be smelling aa mate scent? I’m already mated… to-to you! Are you scenting it too?”

“Yes.” Dolf spoke very quietly, too quietly for the human to hear. In his mind, his cat paced and demanded he claim what was theirs. First things first: he had to make sure Tal was in control. Dolf grabbed Tal by the arm and quickly walked the both of them out of the aisle, away from the human whose scent was driving both of them crazy. “I need you to breathe. In. And out. Yes, yes, good. There you go, Tal. Breathe with me. In… and out. Better?”

“Yes… yes.”

“You have control?”

Tal shuddered one last time. “Yes, I do.”

“Good. That was too close.”

Tal’s mouth fell open, the horror of what he had nearly done reflecting in his face. “Oh my… I almost… and here, of all places! I’m so sorry, Dolf.”

“It’s okay. I talked you down. Can you stay in control so we can go back to that aisle?”

“I can. I’m steady now.” Tal followed Dolf. “It’s just…. That scent surprised me. The last time I smelled something like that was —”

“When we met, yes, I know.” Dolf stopped at the mouth of the aisle. The human was still there. “That human is our mate, Tal.”

Thanks to advanced technology, the shifter community had figured out humans who had a recessive gene could be mates. That gene mutated during the blood transfer between humans and shifters, allowing humans to develop a few shifter abilities, such as rapid healing and lifespan expansion. This way, the human mate lived as long as the shifters.

“What is our goddess thinking?” Tal discreetly glanced at the male. “A threesome? I know that’s uncommon—”

“Uncommon, but not unheard of. There are other instances of this. Forget the stuff we picked out for now,” Dolf said. “We need to stay close to him, see what he drives—get a license plate number and follow him home. We need to know where he lives. The more starting information we have, the easier it’ll be to do searches on him.”

They kept an eye on the human as he checked out. Careful not to draw attention, they followed him to an old beat-up truck. After a couple of tries, the human got the truck started, and they followed him home.

Dolf drove on by as the truck they were following turned onto a gravel driveway. “Try to see if there’s a name on the mailbox. It’s interesting—he’s quite a distance from town. Must like the country.”

“He’s really far off the road too.” Tal watched the other truck for as long as he could. “Last name is Wells.” Tal turned to look at Dolf. “Okay, now what?”

“Now, we go talk to our Alpha.” Dolf turned around. “There are going to be questions about us a taking a third, and a human one at that. We’re going to need permission, and that takes time.”

Tal bit his bottom lip. “Yeah.”

“Let’s go back and get the stuff we didn’t get for my dad, then go eat. It’s going to be a long night.”

“Another mate for us, Dolf. I never dreamed—”

“Neither did I. But no matter, he’s ours, and we will claim him.”

Chapter Two Dolf

THAT EVENING, he and Tal returned to their clowder. They’d made a quick pass through the discount hardware store to retrieve the items from earlier, then eaten an even quicker dinner. Dolf wanted this situation with their mate taken care of as fast as possible. While Tal wrapped the present, Dolf called his dad. It was still early in the evening, early enough his Alpha could call an impromptu meeting if needed.

Dolf finished the call and wandered into the bedroom, where Tal was putting the finishing touches on the gift. “Dad’s on his way over. Better hide that.”

“Gotcha.” Tal followed Dolf to the den. “So, did you tell him?” “Yes.”

“What did he say?”

“He questioned what we smelled, then tried to spin it as something other than a mate scent.”

Tal collapsed on the couch. “Dolf, there’s no misunderstanding that scent or how shifters react to it. I know what I smelled. It almost caused me to lose control in the middle of a store. Not just any scent does that.”

“Not sure we should tell him that.”

“He won’t be happy to hear it, true, but that should show him how the scent affected me. Besides, you talked me down. I didn’t shift.” Tal waved all that aside. “That doesn’t matter, anyway. Fated mates are chosen. He can’t argue with our goddess.”

“Doesn’t mean he won’t attempt to.”

“Are you saying your dad is hardheaded? Because, hello… pot, meet kettle. He says the same about you.”

“I’m sure he does.”

The conversation lapsed, both of them lost in thought. After several minutes, Tal glanced at Dolf. “We’re in for a battle, aren’t we? All because the guy is human.”

“Oh yes.”

Tal bit his bottom lip. “Oh boy.”

Dolf stared out the window. For once, he dreaded seeing his dad. “Yes, oh boy.”

If a human had a mating scent, it identified them as carrying the recessive gene. While a shifter could mate with a human who didn’t have the gene, that human wouldn’t receive shifter abilities. They would only live an average human lifespan. Of course, most shifters weren’t interested in having a human mate.

There was a knock at the back door. Tal answered it, and soon Dolf heard the quiet, easy greeting between the two men. His Alpha and his mate—the two most important men in his life. Soon, there would be another. A human.

Tal led their Alpha to the den. Alpha Armonty appeared to be a middle-aged human male with short black hair touched with white highlights around the temples. His bright blue eyes were sharp and didn’t miss much. Laugh lines edged his mouth and eyes. Standing a couple of inches over six feet, his body carried ropey muscle on a lean frame. Power radiated off the Alpha, a feeling that blanketed the room, proclaiming who was the boss. Most had the urge to roll over and show their belly. That’s how Tal explained it.

Dolf, on the other hand, gritted his teeth. “Dad? Can you dial it back a little? My hair’s standing on end.”

“Sure, Dolf. Didn’t mean to overwhelm you in your own home. I’m just a little concerned with what you told me on the phone.”

Dolf hugged his dad, then motioned to a chair. “Have a seat.

Do you want anything to drink?”

“No, thanks.”

Dolf nodded, sitting down on the couch next to Tal. “Well, then, let’s get to it.” Dolf explained, in graphic detail, what had happened at the hardware store, including both his and Tal’s reactions. Dolf ended by saying they’d followed the human home. They had a last name and an address.

Several minutes passed as the Alpha stared off into space. Finally, he grunted. “From your reactions, there’s no doubt what you smelled was a mate scent. I suppose you want to claim this human?”

“Of course we do. Do you really have to ask us that?” Dolf answered.

“Tal? I need to hear your thoughts on this too. It involves not only Dolf, but you.”

“Of course, Monty.” Tal had permission to address Alpha Armonty by his nickname, Monty, when it was just family. “I want the human. I can’t—won’t—walk away from him. The goddess gave him to us for a reason. We just don’t know what the reason is. Turning away from him would be… it would be…. Dolf?” Tal reached for Dolf.

“Easy, sweetheart.”

Tal stared at his Alpha. “I need him. Weneed him.”

Dolf held Tal’s hand, but his gaze was on his dad. “Yes, we need him. I won’t walk away from my mate either.”

Monty held Dolf’s gaze. Finally, he sighed. “What a mess.”

Dolf raised an eyebrow, irked. “Finding a mate is a… mess? Really? I thought it was a gift to be cherished.”

“Don’t start, Dolf. A fated mate is indeed a gift.” The Alpha rubbed his hands over his face. “We all know that. But this…. Do you have any idea what you’re setting up here? He’s human, Dolf.”

“Tal and I are aware.”

“Watch the tone, son,” Monty growled. “Then you’re also aware that taking a human as a mate is problematic.”

“I know humans aren’t liked by shifters. They’re the biggest threat to our society, and with good reason. I understand that. Some humans tend to act before they think.”

Monty snorted. “Tend to act before they think? Oh, I believe they know exactly what they’re doing when they commit their atrocities. Dolf, look what humans have done to each other through the centuries. Human are narrow-minded, destructive creatures who can’t be trusted. If they can harm each other to such an extent, what do you think they’d do to us?”

“Not all humans are like that. You know as well as I do you can’t tar and feather a race based on the actions of a few.”

“A few? The entire race is more like it.”

“That’s crap and you know it. Goddess help me, I swear shifters are just as speciesist as the humans. There are good humans out there… just like there are narrow-minded, destructive paranormals. Do you realize how you sound? You talk about what humans would do to us, but have you listened to yourself? We’re talking about a mate, Dad.”

“True, but the mate is a human. We have much more to lose if we’re exposed. It’s a risk, Dolf. A huge risk you’re asking this clowder to take over one human.”

“Wait, what are you saying?” Tal jumped up. “Are you saying you won’t give us permission to claim the human? But, but… please! You can’t do that.”

“I can’t?” Power rolled across the room, and Tal whimpered, dropping back down in his seat.

Dolf flowed to his feet, releasing his own power. Energy sizzled, crackling on the air currents as it crashed together. Tal whimpered again. “He wasn’t challenging you, Dad. He misspoke. Tal doesn’t have what it takes to challenge you, and you know that. ButIdo.”

Monty also stood. “Are you challenging me? When you know you’re the next Alpha? I fully intend to hand over the reins when the time is right for me to step down, so why challenge me?”

“I’m not. What I said was Tal doesn’t have what it takes to challenge you, but I do. I didn’t say I was. I don’t think either of us wants to see how that would go down, so stop with the power display. You’re going to force Tal into a shift, and if you do, I won’t be happy.”

Abruptly, the power in the room disappeared. Tal gasped, breath wheezing. “Oh, thank the goddess Bast. Monty, I swear, I didn’t mean that how it sounded. Please, we need to… we need to keep calm. Please. No one wants to see the two of you fight for position.”

“Dolf, can’t you see? Already there’s discord, and the human isn’t even here.”

“The human didn’t cause this, but yes, it’s related to him. Dad, he’s our mate, plain and simple. Maybe it’s time to deal with the prejudice we have against all humans.” Dolf crossed his arms over his chest. Time to make a point. “If you don’t give permission to claim him, then I’ll go rogue and do it anyway.”

Monty’s mouth dropped open. “Are you serious? Go rogue? Leave your clowder and your family? Give up your birthright? Live as an outcast?”

Tal wiped the sweat off his forehead. “He wouldn’t lose everything. He’d still have me. I will also go rogue.”

“You both would give up everything for this human?”

“Yes, Dad. We would. He’s our mate. Why can’t you see the significance of that? Our goddess wouldn’t have given us this human if he was a threat. You knowour goddess wouldn’t jeopardize us that way.”

“I see.”

Dolf held his breath. He knew giving his Alpha such an ultimatum was dangerous, but he needed his dad to see just how serious this was to Tal and him. This was the first battle they would face in claiming the human. If they couldn’t win this… then they would indeed have to go rogue. The human was theirs, dammit, and they would claim him.

“I love you, Dolf, and I love Tal like a son too. You know you don’t have to claim the human. We don’t have to claim the mates Bast gives us.”

“No, we don’t. But we’ve scented him, and ignoring Bast’s choice for us isn’t wise. Even if we didn’t mate with the human, Tal and I would live the rest of our lives knowing we were missing a part of ourselves. And Dad, so would our human—only he’d have no idea why he felt so alone, so empty. We all would suffer. I won’t do that to any of us. I simply won’t.”

Time crawled as the silent war between Dolf and his dad raged. Finally, Monty’s shoulders slumped. “So be it, Dolf. I will stand beside you and Tal.”

“Thank you, Dad. I… thanks.”

Monty nodded his head. “This isn’t going to be easy, you know.”

“I know. But other paranormals have claimed humans. It has happened before. They made it work, and so can we.”

Monty nodded his head. “Well, then, we better take the next step. You have my permission to claim the human. Now, we need to get the betas on board, then deal with the elders.”

THREE DAYS passed before they managed to get the other four betas Aidric, Brier, Remi, and Heller together. Dolf, as the heir apparent, bore the title of head beta. The doorbell rang, signaling the betas and their Alpha had arrived.

“Tal? Can you get that?”

“Sure.”

After everyone sat at the kitchen table, Dolf launched into explaining the reason for the meeting, but as soon as he mentioned another mate, a mate who was human, things spiraled out of control.

“A human? Did you say this mate is human?” Aidric swallowed. “Fuck, Dolf.”

“Yes, I said human,” Dolf answered.

“You can’t be serious.” Shocked, Brier stared at Dolf across the table. “Dolf, man, there must be a mistake.”

“You think I don’t know a mating scent when I smell it? I know what I scented.” Dolf spoke in slow, measured sentences. “I knew it when I smelled Tal, and I knew it when I smelled the human.”

“They’ve imprinted on this person,” Aidric said.

Brier glanced at Aidric. “True, but imprinting isn’t the same as mating.”

“If you’re hinting at us walking away from the human, don’t bother. The human is ours,” Dolf stated, drumming his fingers on the table.

“But… a human. Of all the species on the planet, you want to mate with a human. Unbelievable.” Brier didn’t bother to hide his distaste.

“You already have one mate, and now you get to have another? How the hell do you manage it?” Remi leaned back in his chair, a grin playing on his lips. “Tal, how do you feel about this?”

“Considering the human is my mate too, I’m perfectly fine with it,” Tal said.

Remi, still smiling, leaned over and fist bumped Tal.

“You would risk us for a fucking human?” Heller snarled.

“Tread carefully, Heller,” Alpha Armonty said. “You can voice your opinion, but do it respectfully.”

“But, Alpha, a human? You gave permission for this? Why would you do that?”

“Because, Heller, I know what it means to find your mate. You don’t, not yet. One day, goddess willing, you will,” Alpha Armonty replied.

“As long as it’s not a human.” Heller sniffed.

“I don’t even have one mate yet, and you already have two. I’m so jealous.” Remi shook his head. “You lucky dog.”

“You call having a human hanging around your neck lucky?” Heller sneered. “You know what they say, right? The only good human is a—”

Dolf lunged at Heller. Chairs flew backward as Aidric and Brier jumped up and grabbed Dolf. Remi grabbed Heller, ready to whisk the beta out of the room if needed.

“Is that a threat, Heller?” Dolf yelled. “Did you just threaten my mate? Because if you did, I’ll rip your fucking tongue out and feed it to you.”

“Shit, Dolf.” Tal shuddered.

“Hell’s bells! Dolf, calm down. An Alpha must keep his control even when he wants to knock a few heads together. Dammit, everyone sit their ass down.” Alpha Monty slammed his fist on the table. “Now!” There was a rush of asses hitting chair seats. “I am truly disappointed. I expect better than this from the bunch of you. We will talk about this calmly, is that understood? Calmly!” Alpha Armonty yelled.

The meeting lasted several hours and involved Tal using his calming influence more than once. In the end, three of the four betas backed him and Tal. Heller was the only one venomously against letting a human join their clowder.

Finally the meeting was over, and everyone had left. Tal shut the front door and turned to Dolf. “Thank the goddess that’s over.”

“Oh, I have a feeling it’s just beginning.” Dolf rolled his head, popping his neck. “How can we say we prize our mates, but in the same breath, be so derogatory toward humans? It boggles the mind.”

Exhausted, Tal sighed. “Shifters who have human mates don’t feel that way. It’s those of us who don’t have human mates, who don’t really know any humans.… It’s those shifters who haven’t let go of the old ways and moved on.”

Dolf turned to Tal, gently kissing his mate. “Thank you, sweetheart. As usual, you were the voice of reason.”

“Your dad is right, though. If you’re going to be the Alpha, you do need to learn to control that temper.”

“Oh, my dad is right, huh? My dad? The male who yelled at the top of his voice during the meeting with the betas? That even-tempered male?”

Tal snorted. “You two are so much alike.”

“I know, and you’re right. I do need to learn to stay calm. Good thing the old man is just three hundred years old. I have plenty of time to learn from him.”

“There is that.”

Now the elders were the only ones left. The elders were older males of their clowder with experience, who were too old to fight now. The clowder greatly respected an elder’s opinion, and the Alpha often called on them for advice, as did the betas.

Two weeks later, the Alpha called a meeting with the elders. So much time had passed due to one elder visiting a sick relative out of state. The elders were resistant but finally agreed to accept the human. It had helped that their computer hacker hadn’t found anything worrisome on their mate, whose name was Kirk Wells. Finally, a message was sent to their central territory leader.

Tal stood beside Dolf, holding his hand, a smile plastered on his face as he waved good-bye. “We did it, Dolf. The human is ours.”

“He’s ours. Our mate. Now, let’s go claim him.”

Chapter Three Kirk

“HAPPY NEW Year’s Eve!”

“Oh, bite me,” I mumbled, flashing the Walmart greeter my best death glare.

At six three and two hundred, I had a damn impressive glare. If one more person dared to speak that phrase to me, I was going to string them up by their toenails. Yeah, happy fucking New Year’s Eve. Now kiss my ass.

The forecast predicted snow, thus the mad trip to the store and resulting battle for milk and toilet paper. Why those two items were required to survive a snowstorm was beyond me. I hurried outside, my head down against the ripping cold, my pitiful bag of groceries clutched to my chest. I jumped in the truck and hurried home.

After an ungodly slow drive home, thanks to the snow, I was juggling groceries while opening the back door. Damn snow was coming down harder since I’d left the store. By morning, it was going to be a winter wonderland of nut-grinding insanity. The forecast said we were due to get a foot, at least. Just what we needed. Folks in the South couldn’t drive on sunny days. Throw snow in the mix, and you had accidents just looking for a place to happen. I was very glad I’d decided not to work tomorrow.

“Okay, so, groceries bought. Check. Next on the list—adding wood to the fire.”

I’d banked the fire, now I needed to add more wood. Which entailed getting said wood from outside. Where the snow was. Shit. Taking a deep breath, I braved the outdoors again. Seeing the evil whiteness sticking to everything, I decided to carry several loads inside. After the second trip, I just left the door open. And hey, the floodlight out back decided to work suddenly. What luck. Now I could actually seewhat I picked up.

After the fourth trip, I had enough wood to last the night. I stomped the snow off my boots, intending to head inside, when a streak of black raced past me, making a beeline to the open back door.

“What the hell?” I glanced in the kitchen.

“Meow!” On the table sat one of the biggest black cats I’d ever seen, giving me the eye.

“Oh, fuck me, you have got to be kidding. I don’t think so, pal.” I didn’t have anything against cats. It was just… I was barely taking care of myself, so how was I supposed to take care of a cat?

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

mistake in the formation of a diagnosis. There are, nevertheless, some pathological conditions, such as hemorrhages in the medulla oblongata or thrombosis and embolism of the arteries supplying the latter with blood, which may give rise to the same or very similar phenomena, and thus render a correct diagnosis difficult. In such cases it must be remembered that the cause of true labio-glossolaryngeal paralysis, depending upon degeneration and atrophy of the nervous nuclei along the floor of the fourth ventricle, is very gradual, while the symptoms produced by the causes before mentioned generally make their appearance in a more acute and sudden manner. The latter also, if not remaining stationary for some time, have rather a tendency to improvement, wanting, therefore, the progressive character of the former.

Tumors at the base of the brain also, by pressing upon the roots of the cerebral nerves or upon the medulla oblongata itself, may produce similar symptoms, which, on account of their comparatively slow and gradual development, may prove more difficult to distinguish from those characterizing genuine, progressive labioglosso-laryngeal paralysis. Errors of diagnosis, however, may here be avoided by taking into consideration the special symptoms which generally accompany the presence of tumors of the brain, such as vertigo, headache, vomiting or even hemiplegia, and local paralysis. The sensory nerves also may become affected by the pressure of the tumor upon them. Thus, pressure upon the trifacial nerve may give rise to neuralgic pains, feelings of tingling and numbness, or even anæsthesia; while pressure upon the optic nerves or their tracts, or upon the olfactory and lingual nerves, will be followed by derangements of vision, smell, and taste. The symptoms produced by the pressure of a tumor at the base of the brain, moreover, are not strictly progressive, but may for some time appear, and disappear again before becoming permanent.

Facial diplegia, in which the expression of the face somewhat resembles that of a patient affected with labio-glosso-laryngeal paralysis, is distinguished from the latter disease by the paralysis

affecting both divisions of the facial nerve, while the tongue remains free and deglutition is undisturbed.

There are still other affections of the cerebro-spinal axis, such as paralysis of the insane, disseminated sclerosis, etc., which in their course present some or perhaps all of the symptoms characterizing labio-glosso-laryngeal paralysis; these may be distinguished from the latter disease by taking their own special symptoms into consideration.

TREATMENT.—Although almost all cases of progressive labio-glossolaryngeal paralysis terminate fatally, some cases have been reported by several observers in which a temporary improvement in the symptoms of the disease, or even a total cure, had been obtained by treatment. Of course such favorable results can only be obtained in the initial or earlier stages of the disease. Thus, Kussmaul recommends in the initial stage, when pains in the head and neck are present, wet cupping of the nape of the neck in strong persons, also the use of the shower-bath, while nitrate of silver may be given internally. The application of galvanism in an alternate direction he also recommends—first, through the neck, and later on through the whole spinal column—and at the same time currents in an alternating direction from the neck and hypoglossus nerve to the tongue. Dowse reported a case of bulbar paralysis which he cured by the application of the constant current upon the paralyzed parts, subcutaneous injections of atropine and strychnine, with the internal administration of cod-liver oil, quinine, and phosphorus. He attaches great importance to the careful feeding of the patient through a tube passed through the nose, and to the strict application of the galvanic current; for excessive salivation he recommends atropine. Erb recommends to regulate the diet and the habits of life of the patient in such a manner as to avoid every irritation of the nervous system; furthermore, to generally stimulate the nutrition in order to produce a tonic effect upon the nervous system. For this purpose he principally relies upon a cautious hydropathic treatment, to be continued for a long time and with great regularity. The greatest importance, however, he attaches to electricity, considering the best method of

galvanism as follows: “Galvanize with stabile application transversely through the mastoid processes and longitudinally through the skull, the so-called galvanism of the cervical sympathetic (anode on the nuchus, and cathode at the angle of the lower jaw), and then induce movements of deglutition (twelve to twenty at each sitting); besides this, apply, according to circumstances, direct galvanic or faradic currents to the tongue, lips, and palate.” The electric treatment must be continued for some time, with from four to seven sittings a week.

Of the medicines taken internally, Erb recommends nitrate of silver, iodide of potassium, iodide of iron, chloride of gold and sodium, ergotin, belladonna, and preparation of iron and quinine.

DISEASES OF THE PERIPHERAL NERVES.

BY FRANCIS T. MILES, M.D.

The nervous system of the higher animals is the apparatus by which stimuli coming from the external world or originating in the interior of their own bodies are perceived (its sensitive functions), or cause muscular contraction (its motor functions), or, lastly, cause molecular changes in tissues (its trophic functions).

Besides this power which the nervous system possesses of receiving impressions originating outside of itself and actively replying to them, it appears also to possess the power of originating within itself changes the result of which are sensations, movements, and trophic alterations. In other words, it can act automatically.

The apparatus for the performance of these various functions consists of the end-organs, the nervous centres, and the nerves.

The end-organs are peripheral mechanisms for the reception of impressions. The structure and mode of action of some of them, as the eye and the ear, are pretty well understood, while others, as those connected with the sense of touch, temperature, etc., are but imperfectly known. It is probable that there are also peripheral mechanisms which facilitate the delivery of the impulses coming from the nerve-centres to the organs, tissues, muscles, glands, etc.

The nervous centres are made up of nerve-cells variously connected with each other. They are immediately concerned in receiving impressions conveyed to them by the nerves and transforming them into sensations, or transmitting them to other organs, causing reflex actions, or in originating sensations and impulses.

The nerves are organs which, connected at one extremity with the end-organs and at the other with the nervous centres, convey peripheral impressions to the centres, and impulses and influences from the centres to the various organs of the body.

As it is with diseases of the peripheral nerves that we are now concerned, let us begin by looking more closely into their structure and functions.

The nerves appear to the naked eye as white strands of variable size, which a close inspection shows to be made up of threads or fibrils (best seen when the cut end of a nerve is examined) bound together by fine connective tissue and scantily supplied with bloodvessels. A microscopic examination shows that each of the fibrils visible to the naked eye is made up of a great number of fibres.

These are the medullated nerve-fibres, and they extend unbroken between the nerve-centres, with the cells of which they are connected, to the various organs and tissues, with which they also enter into organic union.

If we examine the structure of a medullated nerve-fibre, we find it to consist of a central thread called the central axis or axis-cylinder, in which close microscopic investigation shows a longitudinal striation, indicating that it is made up of fibrillæ. Surrounding the central axis like a sheath is the white substance of Schwann, composed of an oleo-albuminous substance, myeline, to which the nerves owe their white appearance. According to some observers, the white substance of Schwann is pervaded by a meshwork of fibres. Surrounding the white substance of Schwann is the sheath of Schwann, a structureless membrane having at intervals upon its inner surface nuclei, around which is a small amount of protoplasm.

At intervals along the course of the nerve-fibres are seen constrictions which involve the sheath and white substance of Schwann, but which do not affect the central axis, which passes unbroken the points of constriction. These are the nodes of Ranvier. Each space on the fibre beneath the nodes of Ranvier contains one of the nuclei of the sheath of Schwann, and probably, together with the white substance of Schwann, represents a cellular element. Diseased conditions sometimes respect the limits of these cellular elements.

The central axis is the true conducting part of the nerve-fibre, and it is probable that each of the fibrillæ of which it is composed has a separate peripheral termination and possesses the power of isolated conduction. The white substance of Schwann and the sheath of Schwann protect the central axis and seem to be connected with its nutrition.

The fibres in a nerve are bound together by loose connective tissue, the endoneurium, into the primitive bundles, which are again united by the perineurium, a membrane of laminated connective tissue, into more definite funiculi seen by the naked eye, the secondary bundles.

The secondary bundles are tied together by connective tissue, in which are found fat-cells and in which run the fine blood-vessels supplying the nerves. This connective tissue has been named the epineurium, and its condensed outer layers constitute the sheath of the nerve. It is important to observe that the connective tissue of the nerves is permeated by lymphatics which penetrate to the nervefibres, so that these are brought in contact with, and as it were, bathed in, the lymph.

Each nerve-fibre runs an isolated course from end to end, without anastomosing with other fibres, and near its peripheral termination it usually divides into two or more branches.

The fibres of the peripheral nerves depend for their integrity and nutrition upon their connection with central organs. The large multipolar cells of the anterior horns of gray matter of the spinal cord preside over the nutrition of the motor fibres; the ganglia on the posterior roots of the spinal nerves over the nutrition of the sensitive fibres.

If a nerve be severed from its connection with these centres of nutrition, it in a short while undergoes degenerative changes which result in complete destruction of its fibres.

The nerve-fibres when in a state of functional activity conduct impressions along their length to the end-organs or to the nervecentres with which they are in connection. This property of the fibres we call their conductivity. Each fibre conducts impressions in an isolated manner, not communicating them to other fibres with which it may be in contact. The rapidity of this conduction in human nervefibres is estimated at 33.9 meters (about 38 yds.) per second. This rate may be diminished by cold or by the anelectrotonic condition which is induced in the nerve by the passage through it of an electric current.

The nerve-fibres are irritable; that is, the application to them of stimuli excites their functional activity, and the impression made by the stimulus is transmitted to their extremities.1

1 The nerve-fibres in man do not appear to attain their full irritability until the fifth or tenth month after birth (Soltman).

The natural or physiological stimuli of the nerves act upon their extremities. Either they act through the peripheral mechanisms, giving rise to impressions which are conducted centripetally to the cells of the nerve-centres and there cause sensations or reflex actions, or they act upon the nerve-centres, giving rise to impulses which are conducted centrifugally and cause the various phenomena of contraction of muscles, inhibition of contraction, secretion, etc. Besides the physiological, there are other stimuli which excite the functional activity of nerve-fibres when applied at any point along their course.

Mechanical stimuli, blows, concussions, pressure, traction, etc., excite the nerves, causing sensations when applied to sensitive nerves, or contraction of muscles when applied to motor nerves. When mechanical stimuli are pushed farther, the irritability of the nerves may be destroyed. The gradual application of mechanical stimuli may destroy the irritability of nerve-fibres without any exhibition of excitation, as in paralysis from pressure. In nervestretching it is probable that many of the results depend upon the mechanical stimulation of the nerve-fibres by the traction. With a certain amount of force used the irritability of the nerve may be increased; carried farther, both the irritability and the conductivity may be diminished, and finally destroyed. As the centripetal fibres are soonest affected in the stretching, we can see how this proceeding is most beneficial in neuralgias, where a potent factor, if not the cause of the disease, is an abnormal excitability of the nervefibres. It is to be observed, nevertheless, that in cases of continued pressure upon mixed nerves the motor fibres are the first to suffer loss of their conductivity.

Sudden alterations of temperature act as stimuli to nerves. Heat increases their irritability, but its prolonged application diminishes it. Cold in general diminishes the nervous irritability, and may be carried to the point of completely destroying it temporarily.2

2 But at a certain age in freezing the ulnar nerve Mitchell found its irritability notably increased.

Many substances of widely-different chemical constitution, as acids, alkalies, salts, alcohol, chloroform, strychnine, etc., act as stimuli when applied directly to the nerves, apparently by causing in them rapid molecular changes. Also may be enumerated as chemical stimuli to the nerves substances found naturally in the body, as bile, bile salts, urea. The rapid withdrawal of water from nerve-tissue first increases, and then diminishes, its irritability. The imbibition of water decreases nervous irritability

An electric current of less duration than the 0.0015 of a second does not stimulate the nerve-fibres. It would appear that more time is required for the electric current to excite in nerve-tissue the state of electrotonus which is necessary to the exhibition of its functional activity. The electric current stimulates a nerve most powerfully at the moments of entrance into and exit from the nerve, and the more abruptly this takes place the greater the stimulation. Thus the weak interrupted currents of the faradic or induced electricity owe their powerfully stimulating effects to the abruptness of their generation and entrance into and exit from the nerves. At the moment of the entrance of the electric current into the nerve—that is, upon closing the circuit—the stimulating effect is at the negative pole or cathode; when the current is broken—i.e. leaves the nerve—the stimulating effect is at the positive pole or anode. A current of electricity very gradually introduced into or withdrawn from a nerve does not stimulate it. But if while a current is passing through a nerve its density or strength be increased or diminished with some degree of rapidity, the nerve is stimulated, and the degree of stimulation is in proportion to the suddenness and amount of change in the density or strength of the current. Although with moderate currents the stimulation of the nerve takes place only upon their entrance and exit, or upon variations of their density, nevertheless, with a very strong current the stimulation continues during the passage of the current through the nerve. This is shown by the pain elicited in

sensitive nerves, and the tetanic contraction of the muscles to which motor nerves are distributed.

An important factor in electrical stimulation is the direction of the current through the nerve. A current passed through a nerve at right angles with its length does not stimulate it. Currents passing through a nerve stimulate in proportion to the obliquity of their direction, the most stimulating being those passing along the length of the nerve. Motor nerves are more readily stimulated by the electric current the nearer it is applied to their central connection. Experiments on the lower animals would seem to indicate that the motor fibres in a nerve-trunk do not all show the same degree of irritability when stimulated by the electric current.

The irritability of the nerve-fibres may be modified or destroyed in various ways. Separation of nerves from their nutritive centres causes at first an increase of their irritability, which is succeeded by a diminution and total loss, these effects taking place more rapidly in the portions nearer the nerve-centres. It is important to observe that an increase of irritability preceding its diminution is generally observed in connection with the impaired nutrition of nerves, and is the first phase of their exhaustion.

Prolonged and excessive activity or disuse of nerves causes diminution of their irritability, which may go to the extent that neither rest in the one case nor stimulation in the other can restore it. If a galvanic current is passed through a nerve in its length, the irritability of the fibres is increased in the region of catelectrotonus—viz. in the part near the cathode—and diminished in the region of anelectrotonus—viz. in the part near the anode. Certain substances, as veratria, first increase and then destroy the irritability of the nerves; others, as woorara, rapidly destroy it.

The fibres of the peripheral nerves are divided into two classes: first, those which conduct impressions or stimuli to the nerve-centres, the afferent or centripetal fibres; and, secondly, those which conduct impulses from the centres to peripheral organs, the efferent or centrifugal fibres. Belonging to the first class are (1) sensitive fibres,

whose stimulation sets up changes in the nerve-centres which give rise to a sensation; (2) excito-motor fibres, whose stimulation sets up in the nerve-centres changes by which impulses are sent along certain of the centrifugal fibres to peripheral end-organs, causing muscular contraction, secretion, etc. Belonging to the second class are (1) motor fibres, through which impulses are sent from the nervecentres to muscles, causing their contraction; (2) secretory fibres, through which impulses from nerve-centres stimulate glands to secretion; (3) trophic fibres, through which are conveyed influences from the centres, affecting the nutritive changes in the tissues; (4) inhibitory fibres, through which central influences diminish or arrest muscular contraction or glandular activity. No microscopic or other examination reveals any distinction between these various fibres.

Every nerve-fibre has the power of conducting both centripetally and centrifugally, but the organs with which they are connected at their extremities permit the exhibition of their conductivity only in one direction. Thus, if a nerve-fibre in connection with a muscle at one end and a motor nerve-cell at the other be stimulated, although the stimulus is conducted to both ends of the fibre, the effect of the stimulus can only be exhibited at the end in connection with the muscle, causing the muscle to contract. Or if a fibre in connection with a peripheral organ of touch be stimulated, we can only recognize the effects of such stimulation by changes in the nervecells at its central end which give rise to a sensation.

When we consider the extensive distribution and exposed position of the peripheral nerves, their liability to mechanical injury and to the vicissitudes of heat and cold, we cannot but anticipate that they will be the frequent seat of lesions and morbid disturbances. It may be that not a few of their diseased conditions have escaped observation from a too exclusive looking to the central nervous system as the starting-point of morbid nervous symptoms. This occurs the more readily as many of the symptoms of disease of the peripheral nerves, as paralysis of muscles, anæsthesia, hyperæsthesia, etc., may equally result from morbid conditions of the brain or spinal cord, and not unfrequently the peripheral and central systems are conjointly

affected in a way which leaves it doubtful in which the disease began or whether both systems were simultaneously affected.

The elucidation of such cases involves some of the most difficult problems in diagnosis, and requires not only a thorough acquaintance with the normal functions of the peripheral nerves, but also the knowledge of how those functions are modified and distorted in disease.

The symptoms arising from injuries and diseases of the peripheral nerves are referable to a loss, exaggeration, or perversion of their functions, and we often see several of these results combined in a single disease or as the result of an injury.

The fibres may lose their conductivity or have it impaired, causing feebleness or loss of motion (paralysis), or diminution or loss of sensation (anæsthesia). Or there may be induced a condition of over-excitability, giving rise to spasm of muscles and sensations of pain upon the slightest excitation, not only from external agents, but from the subtler stimulation of molecular changes within themselves (hyperæsthesia). Or diseased conditions may induce a state of irritation of the nerve-fibres, which shows itself in apparently spontaneous muscular contraction or in sensations abnormal in their character, and not corresponding to those ordinarily elicited by the particular excitation applied, as formication or tingling from simple contact, etc. (paræsthesiæ), or in morbid alterations of nutrition in the tissues to which the fibres are distributed (trophic changes).

If we could recognize the causes of all these varied symptoms and discover the histological changes invariably connected with them, it would enable us to separate and classify the diseases of the peripheral nerves, and give us a sound basis for accurate observation and rational therapeutics. But, although the progress of investigation is continually toward the discovery of an anatomical lesion for every functional aberration, we are still so far from a complete pathological anatomy of the peripheral nerves that of many of their diseases we know nothing but their clinical history. We are therefore compelled in treating of the diseases of the peripheral

nerves to hold still to their classification into anatomical and functional, as being most useful and convenient, remembering, however, that the two classes merge into each other, so that a rigid line cannot be drawn between them, and that such a classification can only be considered as provisional, and for the purpose of more clearly presenting symptoms which we group together, not as entities, but as pictures of diseased conditions which may thus be more readily observed and studied.

It is well to begin the study of the diseases of the peripheral nerves by a consideration of nerve-injuries, because in such cases we are enabled to connect the symptoms which present themselves with known anatomical alterations, and thus obtain important data for the elucidation of those cases of disease in which, although their symptomatology is similar, their pathological anatomy is imperfectly or not at all known.

Injuries of the Peripheral Nerves.

If the continuity of the fibres of a mixed nerve be destroyed at some point in its course by cutting, bruising, pressure, traction, the application of cold, the invasion of neighboring disease, etc., there will be an immediate loss of the functions dependent on the nerve in the parts to which it is distributed. The muscles which are supplied by its motor fibres are paralyzed; they no longer respond by contraction to the impulse of the will. No reflex movements can be excited in them either from the skin or the tendons. They lose their tonicity, which they derive from the spinal cord, and are relaxed, soft, and flabby. As the interrupted sensory fibres can no longer convey impressions to the brain, we might naturally look for an anæsthesia, a paralysis of sensation, in the parts to which they are distributed, as complete as is the loss of function in the muscles. Such, however, is not the fact. Long ago cases were observed in which, although sensitive nerves were divided, the region of their distribution retained more or less sensation, or seemed to recover it so quickly that an

explanation was sought in a supposed rapid reunion of the cut fibres. Recent investigations, moreover, show that in a large number of cases where there is complete interruption of continuity in a mixed nerve the region to which its sensitive fibres are distributed retains, or rapidly regains, a certain amount of sensation, and that absolute anæsthesia is confined to a comparatively small area, while around this area there is a zone in which the sensations of pain, touch, and heat are retained, though in a degree far below the normal condition; in short, that there is not an accurate correspondence between the area of anæsthesia consequent upon cutting a sensitive nerve and the recognized anatomical distribution of its fibres. We find the explanation of this partly in the abnormal distribution of nerves, but principally in the fact of the frequent anastomoses of sensitive nerves, especially toward their peripheral distribution, thus securing for the parts to which the cut nerve is distributed a limited supply of sensitive fibres from neighboring nerves which have joined the trunk below the point of section. This seems proved not only by direct anatomical investigation, but also from the fact that the peripheral portion of the divided nerve may be sensitive upon pressure, and that the microscope shows normal fibres in it after a time has elapsed sufficiently long to allow all the divided fibres to degenerate, in accordance with the Wallerian law. Some of the sensation apparently retained in parts the sensitive nerve of which has been divided may be due to the excitation of the nerves in the adjacent uninjured parts, caused by the vibration or jar propagated to them by the mechanical means used to test sensation, as tapping, rubbing, stroking, etc.3 It is to be observed that this retained sensation after the division of nerves exists in different degrees in different regions of the body; thus it is greatest in the hands, least in the face.

3 Létiévant, Traité des Sections nerveuses

As the vaso-motor and trophic nerve-fibres run in the trunks of the cerebro-spinal nerves, destructive lesions of these trunks cut off the influence of the centres with which those fibres are connected, and hence they are followed by changes in the circulation, calorification, and nutrition of the parts to which they are distributed. Thus, the loss

of the vaso-motor influence is at first shown in the dilation of the vessels and the unvarying warmth and4 congestion of the part.5 This gives way in time to coldness, due to sluggish circulation and diminished nutritive activity. Marked trophic changes occur in the paralyzed muscles. They atrophy, their fibres becoming smaller and losing the striations, while the interstitial areolar tissues proliferates, and finally contracts cicatricially. The skin is sometimes affected in its nutrition, becoming rough and scaly. Other trophic changes of the skin resembling those produced by irritation of a nerve are very rarely seen, and they may probably be referred to irritation of fibres with which the part is supplied from neighboring trunks.

4 A remarkable exception is seen, however, in the effect of gradual pressure experimentally applied to nerve-trunks until there is complete interruption of sensation and motion, in which case the temperature invariably falls.

5 In a case of gunshot wound that came under the writer's care in 1862, the leg and foot, which were paralyzed from lesion of the popliteal nerve, remained warm and natural in color during repeated malarial chills, which caused coldness and pallor of the rest of the body.

Anatomical Changes in the Divided Nerve and Muscles.—The

peripheral portion of a divided nerve separated from its nutritive centres degenerates and loses its characteristic appearance, looking to the naked eye like a grayish cord, and being shrunken to onefourth of its natural size. The changes which take place in the degeneration of the nerve-fibres, and which proceed from the point of lesion toward the periphery, are, first, an alteration of the white substance of Schwann, which breaks into fragments, these melting into drops of myeline, and finally becoming reduced to a granular mass. The central axis at a later period likewise breaks up, and is lost in the granular contents of the sheath of Schwann. Meanwhile, absorption of the débris of the fibres goes on, until, finally, there remains but the empty and collapsed sheath of Schwann with its nuclei, the whole presenting a fibrous appearance. When this has taken place the degenerated motor nerve-fibres can no longer be excited, and no stimulation applied to them can cause the muscles to

contract. At the same time, the muscles atrophy and undergo degenerative changes in their tissue. The fibres become smaller and their transverse striæ indistinct, with the appearance of fatty degeneration, and finally there is proliferation of the interstitial cellular tissue. They do not, however, lose their contractility, and upon a mechanical stimulus being applied directly to them they contract in a degree that is even exaggerated, but with a slowness that is abnormal. If, now, we apply the stimulus of electricity to the muscles themselves, we encounter phenomena of the greatest interest and importance. The application of the faradic current, however strong, elicits no contraction; there is loss of faradic excitability. But if the galvanic current be applied the muscles contract, and that, too, in reply to a current too weak to excite healthy muscles to action; there is increased galvanic excitability. The kind of contraction thus induced is peculiar, differing from that ordinarily seen in muscles. Instead of its being short, and immediately followed by relaxation, as when we make or break the galvanic current in healthy muscles, it is sluggish, long-drawn out, and almost peristaltic in appearance. This is characteristic of degenerated muscles, and is the degenerative reaction. But there is also a change in the manner in which the degenerated muscles reply to the two poles of the galvanic current. Instead of the strongest contraction being elicited, as in the normal condition, by the application of the negative pole to the muscle (C. C. C., cathode closing contraction), an equally strong or stronger is obtained by the application of the positive pole (A. C. C., anode closing contraction), while the contraction normally caused on opening the circuit by removal of the positive pole (A. O. C., anode opening contraction) becomes weaker and weaker, until it is at last exceeded by the contraction upon opening the current by the removal of the negative pole (C. O. C., cathode opening contractions). In short, the formula for the reply of the healthy muscles to galvanic excitation is reversed; there is a qualitative galvanic change in the paralyzed and degenerated muscles.

If no regeneration of the nerve takes place, the reaction of the muscles to the galvanic current is finally lost, and they exhibit those

rigid contractions which probably result from a sclerotic condition of the intramuscular areolar tissue.

After complete destruction of the fibres of a nerve at some point of its course, even when a considerable length of it is involved, and after the consequent degeneration of the peripheral portion has taken place, we have, with lapse of time, restoration of its function, consequent upon its regeneration and the re-establishment of its continuity. The histological changes by which the degenerated fibres are restored and the divided ends reunited have not been made out with such certainty as to preclude difference of opinion as to the details. But the process in general seems to be a proliferation of the nuclei in the sheath of Schwann, with increase of the protoplasm which surrounds them, filling the sheath of Schwann with the material from which the new fibre originates. In this mass within the sheath is formed first the central axis of the new fibre, which is later surrounded by the white substance of Schwann. With the regeneration of the nerve-fibres the functions of the nerve return, but in the order of sensation first, and afterward the power of transmitting the volitional impulse to the muscles. Even after regeneration has so far advanced that the muscles may be made to contract by an exercise of the will, the newly-formed fibres fail to respond to other stimuli; thus, the faradic current applied to the nerve does not cause the muscles to contract; the stimulation is not transmitted along the imperfectly restored fibres.

It may be here remarked that after regeneration has restored the functions of a divided nerve the muscles to which it is distributed may still exhibit for a time the degenerative reaction in consequence of unrepaired changes in themselves. In the end we may look for complete restoration in both nerve and muscles.

The time required for the regeneration and reunion of a divided nerve depends somewhat upon the manner in which the destruction has been caused. Thus, a nerve which has been divided by a clean cut, and where the cut ends remain in apposition or close proximity, unites much more readily than one in which bruising, tearing, or

pressure has destroyed an appreciable length of its fibres or the divided ends have been thrust apart.

In complete division of a nerve we must not look for regeneration and restoration of its functions, even in favorable circumstances, before the lapse of several months, although cases have been recorded where the process has been much more rapid.

Injuries of mixed nerves, with incomplete destruction of the fibres, give rise to many and varied symptoms, some of which are the direct result of the injury—many others of subsequent changes of an inflammatory character (neuritis) in the nerves or in the parts to which they are distributed. Pain is one of the most prominent symptoms immediately resulting from nerve-injury, although as a rule it soon subsides. There is sometimes merely numbness or tingling, or there may be no disturbance of sensation at the moment of injury Rarely is spasm of muscles an immediate effect. Generally, motion is at first very much impaired, but if the injury is not grave enough to cause a lasting paralysis, the muscles may rapidly regain their activity. In observing the effects of injuries of mixed nerves one remarkable fact strikes us: it is the very much greater liability of the motor fibres to suffer loss or impairment of function. Thus, it is common to see sensation but little or only transiently affected by injuries which cause marked paralysis of muscles. So in the progress of recovery the sensory disturbances usually disappear long before restoration of the motor function; indeed, sensation may be entirely restored while the muscular paralysis remains permanent. Direct experimental lesions of the mixed nerve-trunks of animals give the same result.6 For this immunity of the sensitive nerve-fibres no explanation can be given other than an assumed difference in their inherent endowments.

6 Luderitz, Zeitschrift für klin. Med., 1881.

According to the amount of damage the nerve has sustained will there remain after the immediate effects of the injury have passed off more or less of the symptoms already described as due to loss of conductivity in the fibres—viz. paralysis of motion, and anæsthesia.

Sometimes the impairment of conductivity in the sensitive fibres shows itself by an appreciable time required for the reception of impressions transmitted through them, giving rise to the remarkable phenomenon of delayed sensation. Degeneration of the nerve peripherally from the point of lesion, and consequently of the muscles, will likewise take place in a greater or less degree, according to the amount of the injury and the subsequent morbid changes, and give rise to the degenerative reaction which has been already described. We will not, however, always encounter the degenerative reaction in the typical form which presents itself after the complete division of nerves. Many variations from it have been observed; as, for instance, Erb's middle form of degenerative reaction, in which the nerve does not lose the power of replying to the faradic or galvanic current, but the muscles show both the loss of the faradic with increased galvanic excitability, with also the qualitative change in regard to the poles of the galvanic current. Such irregularities may be explained by the supposition of an unequal condition of degeneration in the nerve and the muscles. A rare modification has been recorded which has once come under the writer's observation, in which the muscles reply with the sluggish contraction characteristic of the degenerative reaction to the application of the faradic current.

A highly important class of symptoms arise later in injuries of nerves, due not so much to a loss as to an exaggeration or perversion of their functions: they are the result of molecular changes in the nerves, giving rise to the condition called irritation. Irritation of motor nerves shows itself in muscular spasm, or contractions of a tonic or clonic character, or in tremor If the sensitive fibres are irritated by an injury or the subsequent changes in the nerve resulting from it, we may have hyperæsthesia of the skin, in which, although the sense of touch may be blunted, the common sensation is exaggerated, it may be, to such a degree that the slightest contact with the affected part gives rise to pain or to an indescribable sensation of uneasiness almost emotional in its character—something of the nature of the sensation of the teeth being on edge. There may be hyperæsthesia of the muscles, shown by a sensitiveness upon deep pressure, in

which the skin has no part. Pain, spontaneous in its character, is a very constant result of nerve-irritation, whether caused by gross mechanical interference or by the subtler processes of inflammation in the nerve-tissue. It is generally felt in the distribution of the branches of the nerve peripheral to the point of lesion, although it is occasionally located at the seat of the injury. Neuralgias are a common result of the irritation of nerves from injuries.

Causalgia, a burning pain, differing from neuralgia, and sometimes of extreme severity, is very frequent after injuries of nerves, especially in parts where the skin has undergone certain trophic changes (glossy skin). A number of abnormal sensations (paræsthesiæ) result from the irritation of sensitive fibres, and are common after nerve injuries. Among these we may mention a sensation of heat (not the burning pain of causalgia) in the region of the distribution of the nerve, which does not coincide with the actual temperature of the part; it occurs not unfrequently after injury to a nerve-trunk, and may be of value in diagnosis.

The effect of irritative lesions of mixed nerves upon nutrition is very marked, and sometimes gives rise to grave complications and disastrous results. Any or all of the tissues of the part to which the injured nerve is distributed may be the seat of morbid nutritive changes.

In the skin we may have herpetic or eczematous eruptions or ulcerations. It may become atrophied, thin, shining, and, as it were, stretched tightly over the parts it covers, its low nutrition showing itself in the readiness with which it ulcerates from trifling injuries. This condition, called glossy skin, usually appears about the hands or feet, and is very frequently associated with causalgia. The hair may drop off, or, as has been occasionally seen, be increased in amount and coarsened, and the nails become thickened, crumpled, and distorted.

The subcutaneous cellulo-adipose tissue sometimes becomes œdematous, sometimes atrophies, and rarely has been known to become hypertrophied. The bones and joints, finally, may, under the

influence of nerve-irritation, undergo nutritive changes, terminating in various deformities.

With regard to the trophic changes, as well as to the pain and paræsthesiæ resulting from nerve-injury, we must bear in mind that they may be attributed not only to the direct irritation of trophic and sensitive fibres in the injured nerve, but also, in part, to influences reflected from abnormally excited nutritive centres in the spinal cord, and to the spread of the sensitive irritation conveyed to the brain by the injured fibres to neighboring sensitive centres, thus multiplying and exaggerating the effect, causing, as it were, sensitive echoes and reverberations. Indeed, the variety of the symptoms resulting from apparently similar nerve lesions would seem to point to the introduction of other factors in their causation than the simple injuries of the nerve-fibres themselves.

DIAGNOSIS OF NERVE INJURIES.—Although in the great majority of cases the circumstances attending nerve injuries render their diagnosis a matter of little difficulty, it is yet important to keep in mind those symptoms which distinguish them from lesions or diseases of the brain and spinal cord, inasmuch as in cases of multiple lesion, injuries to the spinal column, or where the history of the case is imperfect, it may be difficult to determine to which part of the nervous system, peripheral or central, some of the gravest resulting troubles are due. Paralysis, spasm, anæsthesia, atrophy, etc. may be of central or spinal as well as peripheral origin, and an intelligent prognosis and rational treatment alike demand that we should distinguish between them. Moreover, many diseased conditions of the peripheral nerves of whose pathology we are ignorant, and in which localizing symptoms—i.e. those indicating the exact point at which the nerve is implicated—are wanting, can only be distinguished as peripheral affections by the occurrence of symptoms which we recognize as identical with those arising from injuries of nerves, in which definite histological changes are known to occur. Indeed, cases of disease of the nervous system are not infrequent in which a careful study of their symptomatology leads to a difference of opinion in the minds of the best observers as to