Teaching, Affirming, and Recognizing

Trans and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework 1st Edition

Sj Miller

(Eds.)

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/teaching-affirming-and-recognizing-trans-and-gendercreative-youth-a-queer-literacy-framework-1st-edition-sj-miller-eds/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Biota Grow 2C gather 2C cook Loucas

https://textbookfull.com/product/biota-grow-2c-gather-2c-cookloucas/

The Remedy Queer and Trans Voices on Health and Health Care 1st Edition Zena Sharman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-remedy-queer-and-transvoices-on-health-and-health-care-1st-edition-zena-sharman/

Becoming a Malaysian Trans Man: Gender, Society, Body and Faith Joseph N. Goh

https://textbookfull.com/product/becoming-a-malaysian-trans-mangender-society-body-and-faith-joseph-n-goh/

Gender and Queer Perspectives on Brexit Moira Dustin

https://textbookfull.com/product/gender-and-queer-perspectiveson-brexit-moira-dustin/

Lesbian

Gay Bisexual Trans Intersex and Queer Psychology An Introduction 2nd Edition Sonja J. Ellis

https://textbookfull.com/product/lesbian-gay-bisexual-transintersex-and-queer-psychology-an-introduction-2nd-edition-sonjaj-ellis/

Making Space for Queer-Identifying Religious Youth 1st Edition Yvette Taylor (Auth.)

https://textbookfull.com/product/making-space-for-queeridentifying-religious-youth-1st-edition-yvette-taylor-auth/

Teaching Information Literacy in Higher Education. Effective Teaching and Active Learning Mariann Lokse

https://textbookfull.com/product/teaching-information-literacyin-higher-education-effective-teaching-and-active-learningmariann-lokse/

Psychometric Framework for Modeling Parental Involvement and Reading Literacy 1st Edition Annemiek Punter

https://textbookfull.com/product/psychometric-framework-formodeling-parental-involvement-and-reading-literacy-1st-editionannemiek-punter/

Working with High-Risk Youth : A Relationship-Based Practice Framework 2nd Edition Smyth

https://textbookfull.com/product/working-with-high-risk-youth-arelationship-based-practice-framework-2nd-edition-smyth/

TEACHING, AFFIRMING, AND RECOGNIZING TRANS AND GENDER

CREATIVE YOUTH

A Queer Literacy Framework

sj Miller

Queer Studies and Education

Series Editors

William F. Pinar

Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy

University of British Columbia Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Nelson M. Rodriguez

Women’s & Gender Studies

The College of New Jersey Ewing, New Jersey, USA

Reta Ugena Whitlock

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia, USA

LGBTQ social, cultural, and political issues have become a defining feature of twenty-first century life, transforming on a global scale any number of institutions, including the institution of education. Situated within the context of these major transformations, this series is home to the most compelling, innovative, and timely scholarship emerging at the intersection of queer studies and education. Across a broad range of educational topics and locations, books in this series incorporate lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex categories, as well as scholarship in queer theory arising out of the postmodern turn in sexuality studies. The series is wideranging in terms of disciplinary/theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches, and will include and illuminate much needed intersectional scholarship. Always bold in outlook, the series also welcomes projects that challenge any number of normalizing tendencies within academic scholarship from works that move beyond established frameworks of knowledge production within LGBTQ educational research to works that expand the range of what is institutionally defined within the field of education as relevant queer studies scholarship.

More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14522

sj Miller Editor

Teaching, Affi rming, and Recognizing Trans* and Gender

Creative Youth

A Queer Literacy Framework

Editor sj Miller

School

of Education–Curriculum and Instruction

University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, Colorado, USA

Queer Studies and Education

ISBN 978-1-137-56765-9

DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-56766-6

ISBN 978-1-137-56766-6 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016942090

© The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

Printed on acid-free paper

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature

The registered company is Nature America Inc. New York

The world changes in direct proportion to the number of people willing to be honest about their lives.

Armistead Maupin

This work is dedicated to all trans*, queer, and gender creative youth whose lives have been lost in the war of misrecognition and misunderstanding. May your deaths not be in vain. May we draw hope from your darkest moments. May this work offer some attempt to heal your friends and families who lost you far too soon. We are here. We hear you. And, we are so, so sorry.

A Note On The Book’s Title

The asterisk has been removed from “trans*” on the cover to avoid errors in older electronic search systems.

F OREWORD

The relationship between realness and representation has been central to education for millennia. When Socrates discusses the divided line, he is critical of the act of representation for replacing the real with a pale copy. While we may not agree with his analysis, he does indicate to us the power of representation and the potential for reinscriptions to upset seemingly solid conceptions of what is real and by so doing to push us into new ways of thinking about truth, presence, and learning. Prof. sj Miller’s wonderful edited collection pushes us to see the complex relationship between trans* people and other aspects of gendered and sexuality-related identity, authenticity, representation, recognition, and contestation. In a sense, this collection works a complex divided line of its own; it destabilizes gender identity and insists on the stabilization of justice by engaging the possibilities within literacy education. Reading (really, Socrates was right on this) is an interpretive task that shatters certainty but one also embedded in understandings that precede it. The circulation of meanings, in the best pedagogical and political contexts, opens possibilities for understandings, communities, and subjectivities. In its finest practice then, literacy is a transactional event, inviting students into meaning making and showing them that their intellect, lives, and bodies matter. Miller calls on us here to ensure we recognize trans* students and ensure their place in this energetic and challenging sort of learning community.

The authors in this collection aim to help us to think about how trans* innovations to teaching and learning can enhance student criticality and encourage equitable education. Encouraging students to understand the multiplicity of interpretations and experiences in their midst provides

them not only with contexts for intellectual growth, but it also invites them into a world characterized in and through diverse perspectives and experiences. But schools may also be experienced as contexts that perpetually stress the right way to be, think, and act. In this sort of constrained institutional environment, perhaps too intent on accountability more than on students flourishing, the play of gender, the reversals of readings, and other resistant actions become suppressed by restrictive pedagogies, narrow curricula, and inequitable practices.

Queer and trans* theories have helped show us generative refusal of stability both in the context of meaning and subjectivity. This book shows how pedagogies based in those refusals can counter institutional omissions and welcome trans* students into schools, as well as encourage trans* allies to create equitable lessons and classrooms. Many educators are of course troubled by the exclusions written into school policy and practice. We can cite multiple examples of exclusions from the perpetual underserving of lower-income communities of color to more specific instances. We can cite the connections among exclusions; the outlawing of ethnic studies in Arizona; the fake prom in Mississippi held for queer kids and students with disabilities; and, the initial refusal of the principal of Sakia Gunn, who was African American and gender-nonconforming, to allow a moment of silence to mark her murder. Schools, all too often, are contexts for damaging refusals: refusal to recognize language and cultural diversity, refusal to mitigate divisive disciplinary policies, refusal to recognize gender identity diversity, and, the refusal to be inclusive of embodied and intellectual diversities. The added damage of these refusals of schools to sufficiently care for trans* and gender-nonconforming students may be seen in the disproportionate rates of bias and violence they experience, including especially the violence experienced by trans women of color. While schools will not solve everything, they are nonetheless institutions that can reflect the better hope for futures without violence through becoming more inclusive and welcoming places of and for difference.

This collection encourages educators to become more finely attuned to the play of meaning in texts and to the necessity for respect for the vast diversity of student identities. It encourages us to understand as well that trans* students are adept critical readers of social and embodied possibility, able to think at young ages about who they are and want to be. And one hopes that with more books like this groundbreaking collection, educators will be increasingly able to help young people negotiate what seems to be, sometimes, hopefully, a more welcoming society. Young trans

people are coming out earlier and more often. Our task is to ensure that they are met with care and recognition of their complex work with and through genders, and to ensure they have access to educational contexts that encourage their flourishing, their creativity, and their potential to continue to help us all to think, read, and live gender better.

Cris

Mayo University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to thank the contributors of this work for their care and compassion about creating classrooms that refuse to leave anyone out. I want to thank the inimitable Cris Mayo for being a silent strength and heartbeat that I knew I could always count on. We hardly know each other but I know we are kindred spirits. Thank you to Nicole Sieben, Sue Hopewell, Les Burns, Bettina Love, Cris Mayo, Nelson Graff, Kerryn Dixon, Meghan Barnes, and Stephanie Shelton for feedback on early drafts. I want to thank my chosen family Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Bettina Love, Darrell Hucks, Kerryn Dixon, Shirley Steinberg, Eelco Bultenhuis, Maryann Shaening, Mike Wenk, Penny Pence, Betsy Noll, Don Zancanella, Sue Hopewell, Diane and Todd Smith, Tara Star Johnson, Les Burns, Cynthia Tyson, Deb Bieler, Nicole Sieben, and Briann Shear, for their constant show of care and love and for never giving up on me. Each, in their own way, have encouraged me to keep writing and pushing boundaries, and to give voice to those in need of voice through the academy. Thank you for your unconditional love over the years and for supporting me to finally find home in my body. Together, through the relationship between families and teachers, trans and gender creative youth are the hope for our future by embodying the change that can shift the genderscape of society.

The original version of this book was revised.

An erratum to this book can be found at DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-56766-6_17

1 Introduction: The Role of Recognition 1 sj Miller

2 Why a Queer Literacy Framework Matters: Models for Sustaining (A)Gender Self-Determination and Justice in Today’s Schooling Practices 25 sj Miller

3 Teaching Our Teachers: Trans* and Gender Education in Teacher Preparation and Professional Development 47 Cathy A.R. Brant

4 Kindergartners Studying Trans* Issues Through I Am Jazz 63 Ashley Lauren Sullivan

5 Beyond This or That: Challenging the Limits of Binary Language in Elementary Education Through Poetry, Word Art, and Creative Bookmaking 81 benjamin lee hicks

6 The Teacher as a Text: Un-centering Normative Gender Identities in the Secondary English Language Arts Classroom 107

Kate E. Kedley

7 The T* in LGBT*: Disrupting Gender Normative School Culture Through Young Adult Literature 121

Katherine Mason Cramer and Jill Adams

8 Risks and Resiliency: Trans* Students in the Rural South 143

Stephanie Anne Shelton and Aryah O’Tiss S. Lester

9 Introducing (A)gender into Foreign/Second Language Education 163

Paul Chamness Miller and Hidehiro Endo

10 Exploring Gender Through Ash in the Secondary English Classroom 185

Paula Greathouse

11 Transitional Memoirs: Reading Using a Queer Cultural Capital Model 199

Summer Melody Pennell

12 Trans* Young Adult Literature for Secondary English Classrooms: Authors Speak Out 231

Judith A. Hayn, Karina R. Clemmons, and Heather A. Olvey

13 Puncturing the Silence: Teaching The Laramie Project in the Secondary English Classroom 249

Toby Emert

Michael Wenk

Kathryn Cloonan

L IST OF F IGURES

Picture 2.1 A classroom that supports the development of (a)gender self-determination 31

Fig. 2.1 A queer literacy framework promoting (a)gender and self-determination and justice (Modified but originally printed as Miller (2015). Copyright 2015 by the National Council of Teachers of English. Reprinted with permission) 36

Fig. 2.2 Examples of pathways for Principle 1 37

Picture 2.2 Example of Principle 5

38

Fig. 2.3 Examples of pathways for Principle 5 39

Fig. 2.4 Examples of Principle 6 41

Picture 2.3 Example of Principle 5 42

Fig. 3.1 Critical questions when analyzing gender norms over the years 58

Fig. 3.2 Critical questions for analysis of children’s clothing and toys 58

Chart 4.1 Character splash for I Am Jazz (sample layout)

Chart 4.2 Character chart for I Am Jazz

69

71

Chart 4.3 Character splash for I Am Jazz (sample of what you would expect to have completed at this point in the lesson) 73

Chart 4.4 Character splash for I Am Jazz (sample of what you would expect to have completed at this point in the lesson)

Chart 4.5 Character splash for I Am Jazz (sample of what you would expect to have completed at this point in the lesson)

77

78

Fig. 5.1 Documenting key words from student descriptions of “most-me” objects (Photo credit: Grace Yogaretnam) 91

Fig. 5.2 The collaborative poem in process of my grade three/four class (2015) 94

Fig. 5.3 One page of the template containing all the words that were generated in part one of this lesson 96

Fig. 5.4 Sebastian (grade four) choosing the words that he will use to compose his self-identity poem (Photo credit: Grace Yogaretnam)

Fig. 5.5 Jade’s completed self-identity poem booklet: interior view (grade three)

Fig. 5.6 Instructions for folding an eight-page mini-book out of one piece of 11″ × 17″ paper (Graphic: benjamin lee hicks)

Fig. 5.7 Ji-Hoo’s word-art version of “BRIGHT ENERGY” integrated into the first page of her identity-poem minibook (grade three)

97

98

99

100

Fig. 5.8 Sebastian’s mini-book with the line “there are Lego masters, artists and builders in my class,” enhanced by a fold-out section of word art that itself becomes a structure (grade four) 101

Fig. 9.1 Sample of Michael’s Diary: acceptance

Fig. 9.2 Sample of Michael’s Diary: what makes him happy?

Fig. 9.3 Sample of Michael’s Diary: conflict

Fig. 9.4 Sample of Death by Bullying: adults can help

Fig. 9.5 Sample of Death by Bullying: nothing can help

Fig. 9.6 Sample of Death by Bullying: blaming the victim

Fig. 10.1 Graphic organizer: Cinderella across time periods and cultures

Chart 11.1 Queer cultural capital definitions and examples

Chart 11.2 Student reading handout for memoirs

Fig. 16.1 Co-beneficiaries of this research

L IST OF T ABLES

Table 1.1 Axioms for a trans* pedagogy 9

Table 9.1 Overview of the lesson 174

Table 10.1 Common definitions (Miller 2016, ix–xxii) 192

Table 11.1 Forms of cultural capital from Yosso and Pennell 206

Table 11.2 Anticipation guide

Table 11.3 Queer cultural capital in trans memoirs

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: The Role of Recognition

sj Miller

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

-W.E.B. Du Bois (1903)

I do not want to explain myself to others over and over again. I just want to be seen.

-sj

At one year of age, Blue is a curious and precocious pre-toddler, feeling her way through the world, putting everything in sight in her mouth, and grabbing spoons and using the family dog as a drum. Blue runs around a lot. In fact, Blue runs around so much, her family predicts Blue will become a phenomenal runner or some type of athlete. It is the early 1970s so Blue’s parents dress her in gaudy suede jumpers with bling, pink socks, and clogs. Sort of a mismatch to the identity Blue has begun to exhibit.

At two, Blue’s affinity for running has accelerated. Now, Blue runs after the dog, the neighbor, the birds, and right out of the door, into the yard,

sj Miller ()

University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, USA

© The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016

sj Miller (ed.), Teaching, Affirming, and Recognizing Trans and Gender Creative Youth, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-56766-6_1

1

and even the street. Blue’s mom supports these adventurous pursuits, but Blue’s dad does not think it’s appropriate for his daughter to behave this way, and even asserts, “I don’t want my daughter to be a tomboy.” Blue is just being Blue.

From ages three to five, Blue looks like a boy. Her hair fro’d, her now tube socks hiked up to her knees, her cutoffs pretty hideous even for the 1970s, and her appearance, masculine. Blue likes to watch her father pee standing up, and when alone, tries to emulate the behavior, but with limited success, and lots of splatter on the floor. Blue likes to watch her father shaving, and when alone, smears toothpaste on her face and traces it off with strokes of her toothbrush. She is far more successful with this task than the attempts at urinating. Blue likes to ride her Huffy BMX bike around the neighborhood and bring food home to her mom and sister when her dad is late home from work. Blue steps into a caregiving role, quite naturally, because it is just what feels right.

Blue loves playing football topless in the streets like the other boys do, and seems to be living life in a way that just seems right and normal. Then one day Blue runs into the house screaming, “I want to be a boy!” Blue’s parents do not understand these words, but actually maybe they do. In response, Blue’s dad begins to gender Blue by reminding her of her gender in passive-aggressive ways. For special events, he wrestles Blue into dresses and heels, only for Blue to then throw her body into dog shit and roll around in it. Then Blue’s dad beats Blue and dresses her up again. Helpless and in tears, Blue’s mom, watched passively as her only recourse. To different degrees, this family battle would play out for the next forty years.

At the age of five, Blue enters school. Blue has mostly boys as friends and enacts behavior typical of other boys. Blue plays sports during recess, sits with the boys at lunch, tries to pee in the boy’s restroom, and only wants to be in classroom groups with other boys. The only gender marker to reveal that Blue is a girl is her clothing and the colors, those that typically demarcate girls’ identities. Blue doesn’t understand when the class is separated into groups based on gender and why she is put into the groups with other girls. After all, Blue feels like a boy, thinks she is a boy, and is treated like a boy by other boys in school.

As Blue goes through her primary and secondary schooling years, gender was not on the radar in her teachers’ classrooms. Music, dating, film, and athletics are the only aspects of her life, outside of her family, that gives Blue sources to understand her gender confusion. Blue is drawn to musicians for unconscious reasons. For Blue, the artists and bands she

is most drawn to, like Morrissey (the Smiths), Adam Ant, David Byrne, Tracy Chapman, Boy George, Depeche Mode, the Talking Heads, Kate Bush, Pet Shop Boys, Erasure, Trio, Oingo Boingo, New Order, Yaz, and David Bowie seem to express challenges to the gender binary through both looks and lyrics. Blue’s favorite musician is Robert Smith, lead singer of The Cure. Smith dresses in black, has disheveled hair, wears lipstick, and occasionally even dresses. Smith’s lyrics are poetic, dark, and forlorn but they bring meaning, order, and respite to Blue. Blue listens to everything produced by The Cure until it drowns out the negative thoughts about Blue’s internal gender struggle. The Cure is the cure.

Throughout high school, Blue dates males. Blue doesn’t understand her feelings but is drawn to boys, as if she herself is one. She has many close female friends and is attracted to some of them, but not from the identity of female; she is drawn to them as if she is male. So she continues to live her life, dates males, acquires friends along a continuum of genders and with queered identities—gay, lesbian, bisexual, and straight. All of this just feels normal to Blue. The unconscious urges to be with males, as a male, remain unremitting but she does not know how to talk about them. None of her teachers address gender or sexual identity in her classes. She reads no texts, sees no examples of herself or others that could possibly help her understand who she is. Even with friends and teachers she adored, she is lost at school.

Blue turns to film for reasons similar to music. Films assuage a curiosity that gives visual recognition to different identities in the world. Without the language to support the unconscious emotionality Blue feels, films such as The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, I’ve Heard the Mermaid Singing, and all films by Ivory Merchant Productions become running stills that shape and inform who Blue is becoming. Many of the characters in the films, and the actors who illuminate them, give calm to the raging storm brewing inside Blue.

Soccer and swimming, two stabilizing factors for Blue’s identity development throughout secondary school, provide critical spaces and opportunities to release pain and confusion. Again, without the language to know what Blue feels inside, these sports calm the inner rage. Blue is a better-than-average swimmer and often places in the top five at meets in both freestyle and butterfly sprints. Blue’s natural talent as a runner is channeled into soccer, and Blue is a star. As a forward, Blue breaks district and state records, leads her team to compete at the state level, and becomes the first female All-American in her state. Six top academic and

Division 1 schools offer her scholarships. She chooses Cal-Berkeley. With memories of her family, music, friends, teachers, school, and film, Blue leaves for college—it is 1988. The future is unknown, and it would take Blue until age forty, twenty-two years later, to come to terms with her gender confusion….

RECOGNITION

The struggle for recognition is at the core of human identity. With social positioning as the presumed or “normative” condition, those whose gender identities fall outside of the binary tend to be misrecognized and misunderstood and suffer from what I call a recognition gap, much as I did in my childhood and adolescence, when I was Blue. Misrecognition subverts the possibility to be made credible, legible, or to be read and/or truly understood. When one is misrecognized, it is altogether difficult to hold a positive self-image, knowing that others may hold a different or negative image (Harris-Perry 2011). When the presumed normative condition is challenged though, a corollary emerges; this suggests that at the base of the human condition, people are in search of positive recognition, to be seen as “normal,” because it validates their humanity.

Looking back into my youth, there was no common language for society to help people understand gender confusion, or if there was it was not brought into my life. This leaves me little room to wonder why a core group of my peers in high school and even in college—many who felt similar to me—have only come to identify themselves as trans*1 or gender creative2 later in their lives. As language and understanding around trans* and gender creative identities have become part of the social fabric of society, youth have had more access to recent changes in health care and therapeutic services that have supported them in their processes of becoming and coming to terms with their true selves. These opportunities for visibility have galvanized a movement fortifying validation and generating opportunities for both personal and social recognition. Now, we see more trans* and gender creative people portrayed positively in the media. With individuals such as Laverne Cox, Janet Mock, Chaz Bono, Aydian Dowling, Scott Turner Schofield, Ian Harvey, and Caitlyn Jenner, and TV shows such as Transparent, Becoming Us, Orange Is the New Black, The Fosters, and I am Jazz, just to name a few, we see a growing media presence. With an estimated 700,000 trans* people now living in the USA,

there is even the “Out Trans 100,” an annual award given to individuals who demonstrate courage through their efforts to promote visibility in their professions and communities. But, where teacher education still falls short is in how to support pre-K-12 teachers about how to integrate and normalize instruction that affirms and recognizes trans* and gender creative youth. These identities are nearly invisible in curriculum and in the Common Core Standards. That is why this book was written, as an attempt to bring trans* and gender creative recognition and legibility into schools. In this collection, authors model exciting and innovative approaches for teaching, affirming, and recognizing trans* and gender creative youth across pre-K-12th grades.

To understand the role of recognition in school, this work draws inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois who, in The Souls of Black Folk, wrote about the struggle for Black recognition and validation in USA. In this book, Du Bois (1903) describes a double consciousness, that sense of simultaneously holding up two images of the self, the internal and the external, while always trying to compose and reconcile one’s identity. He concerns himself with how the disintegration of the two generates internal strife and confusion about a positive sense of self-worth, just as I shared in my story. Similar to what Du Bois names as a source for internal strife, youth who live outside of the gender binary and challenge traditionally entrenched forms of gender expression, such as trans* and gender creative youth, experience a double consciousness. As they strive and yearn to be positively recognized by peers, teachers, and family members, they experience macroaggressions, because of their systemic reinforcement, and are forced to placate others by representing themselves in incomplete or false ways that they believe will be seen as socially acceptable in order to survive a school day. Such false fronts or defensive strategies are emotionally and cognitively exhausting and difficult (Miller et al. 2013), otherwise known as emotional labor (Hochschild 1983; Nadal et al. 2010; Nordmarken 2012); trans* and gender creative youth are thereby positioned by the school system to sustain a learned or detached tolerance to buffer the self against the countless microaggressions experienced throughout a typical school day. In fact while research from Gay, Lesbian & Straight Educators Network (GLSEN) (2008, 2010, 2014) reveals that at the secondary level trans* youth experience nearly the highest rates of bullying in schools, even more startling, painful, and of grave concern is that trans* youth of color, when combined with a queer sexual orientation, experience the highest rates of school violence.

When school climates support and privilege the normalization of heterosexist, cisgender, Eurocentric, unidimensional (i.e., non-intersectional), or gender normative beliefs—even unconsciously—it forces students who fall outside of those dominant identifiers to focus on simple survival rather than on success and fulfillment in school (Miller 2012; Miller and Gilligan 2014). When school is neither safe nor affirming, or lacks a pedagogy of recognition, it leaves little to the imagination why trans* and gender creative youth are suffering. As potential remedy to disrupt this double consciousness and an erasure of such youth, a trans* pedagogy emerges from these urgent realities and demands for immediate social, educational, and personal change and transformation. Such legitimacies of the human spirit, when affirmed by and through a trans* pedagogy, invite trans* and gender creative youth to see their intra, inter, and social value mirrored, and to experience (a)gender3 self-determination and justice. My hope for the millennial generation of trans* and gender creative youth is that they can start living the lives they were meant to have from an early age, be affirmed and recognized for who they are, and not wait a lifetime to find themselves. Educating teachers (and parents) and school personnel across grade levels is an intervention and potential remedy. For schooling to truly integrate and embed gender justice into curriculum, it is important to understand the history of gender injustice that led us to the present day. When Edmund Burke spoke the words “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it,” little did he know the importance of how their potential prophecy would manifest for specific populations of humanity.

ATTEMPTS AT TRANS* ERASURE

While nearly thirty years of research about the criticality of bridging lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning issues (Quinn and Meiners 2011) to school curriculum has been well documented, education remains without a large-scale study of how schools of education are preparing preservice teachers to address and incorporate topics for the millennial generation lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, agender/ asexual, gender creative, and questioning youth (LGBTIAGCQM)4 (Miller 2015). There is, however, a growing body of pre-K-16 LGBTIAGCQ research across various geographical contexts of preservice teacher preparedness. Studies include teachers’ personal beliefs (Meyer 2007; Miller 2014; Robinson and Ferfolja 2001a, b; Schmidt et al. 2012); teaching and queering disciplinary literacy (Athanases 1996; Blackburn and

Buckley 2005; Clark and Blackburn 2009; Ryan and Hermann-Wilmarth 2013; Schmidt 2010); preparing teachers to teach queer youth of color (Blackburn and McCready 2013; Cammarota 2007; McCready 2007); program effectiveness on preparing teachers to teach LGBTQGV issues (Griffin and Ouellett 2003; Szalacha 2004); and of key relevance to this book, challenges to gender norms (Miller 2009; Martino and PallottaChiarolli 2003; Mayo 2004, 2007; Robinson 2005; Savage and Harley 2009). Absent from this list is both glaring and recognizable—supporting teachers who work with or will work with trans* and gender creative youth. While previous work has been concerned with gender normativity and has focused on trans* issues in the midst as part of LGBTQ work, this book takes supporting trans* and gender creative students as its primary and concerted function.

Historically, society has tried to erase trans* people but in this attempt at erasure, trans* identities and visibility (Namaste 2000) have actually been produced. In this production though, society writ large has experienced a grand anxiety (Miller 2015), and trans* and gender creative youth are the resultant victims of this anxiety. In schools therefore, such youth experience inurement because of this larger lack of systemic recognition and legibility. This production of invisibility of trans* and gender creative youth has generated a movement toward greater visibility, and such visibility is where this work asserts that a trans* pedagogy must be produced to sustain the personal and social legitimacy of trans* and gender creative youth as both recognizable and validated.

Such polemics usher in the urgent concern about what schools and teachers can do to not only recognize the presence of trans* and gender creative students in their classrooms, but how to sustain safe, affirming, and inclusive classrooms across myriad sociocultural and linguistic contexts. Through a queer literacy framework (QLF) (Miller 2015, 2016, forthcoming), a framework guided by ten principles and subsequent commitments about how to recognize, honor, and affirm trans* and gender creative youth, the next chapter presents how teachers can use trans* pedagogy and sustain curriculum in order to mediate safe, inclusive, and affirming classroom contexts. Drawing then from parts of the QLF, the book offers pre-K-12 teachers a select sample of strategies that cut across social, economic, cultural, and linguistic contexts to support their students about how to understand and read (a)gender through a queer lens; how to rework social and classroom norms where bodies with differential realities in classrooms are legitimated and made legible

to self and other; how to shift classroom contexts for reading (a)gender; and how to support classroom students toward personal, educational, and social legitimacy through understanding the value of (a)gender selfdetermination and justice.5

A TRANS* PEDAGOGY AND A THEORY OF TRANS*NESS

First, we begin with why a trans* pedagogy matters? We know that in schools, trans* and gender creative youth have identities that are “made” vulnerable to incurring the highest rates among their peers of bullying, harassment, truancy, dropping out, mental health issues (Kosciw et al. 2010; Miller et al. 2013), and suicidal ideation (Ybarra et al. 2014). Such deleterious realities beget a deeper and more systemic issue that unearths how underprepared teachers and schools are equipped to mediate learning that affirms and creates and then sustains classrooms of recognition and school spaces for all (Jennings 2014; Quinn and Meiners 2011) While many tropes about trans* and gender creative youth focus on their suffering, this project hopes to advance a different narrative that calls for recognition, stemming from a misrecognition. Some argue that we cannot have pedagogy without theory but in this case, I operate from the premise that youth need recognition in classrooms and schools, and from within that indeterminate context, a theory of trans*ness emerges. By creating a pedagogy for trans*ness, a pedagogy built upon and by rhizomatic (Deleuze and Guittari 1987; Miller 2014), spatiality and hybridity, and geospatial (Miller 2014; Soja 2010) theories, this work seeks to inspire a school climate that advances and graduates self-determined youth whose bodies become spatially agentive (Miller 2014), who can shift deeply entrenched binary opinions about gender through a deepening of human awareness, thus revealing that identities are multitudinous and on an everchanging path in search of love and recognition.

A trans* pedagogy first and foremost presumes axioms (see Table 1.1) that can both validate trans* and gender creative youth and support their legibility and readability in schools and form the foundation for a trans* pedagogy. For instance:

WhatDoesTrans*Mean?

The word trans* infers to cut across or go between, to go over or beyond or away from, spaces and/or identities. It is also about integrating new

ideas and concepts and new knowledges. Trans* is therefore comprised of multitudes, a moving away or a refusal to accept essentialized constructions of spaces, ideas, genders, or identities. It is within this confluence or mashup that the self can be made and remade, always in perpetual construction and deconstruction, thereby having agency to create and draw the self into identity(ies) that the individual can recognize. But self-recognition is not enough because, as Butler (2004) suggests, human value is context based, and one’s happiness and success are dependent on social legibility (p. 32). Therefore, the possibility of becoming self-determined presumes the right to make choices to self-identify in a way that authenticates one’s self-expression and self-acceptance, rejects an imposition to be externally controlled, defined, or regulated, and can unsettle knowledge to generate new possibilities of legibility.

Self-determination resides in the rhetorical quality of the “master’s” discourse (Butler 2004, p. 163). This is problematic when the “master’s” (i.e., in this case the teacher or the school) discourse lacks deep understanding about how to integrate new knowledges that affirm trans* and gender creative youth. Therefore, this theory of trans*ness suggests that for new knowledges to emerge, classrooms must be thought of and taught rhizomatically, or as a networked space where relationships intersect, are concentric, do not intersect, can be parallel, non-parallel, perpendicular, obtuse, and fragmented (Miller 2014). Arising from this plan then, trans* as a theoretical concept connects to spatiality and hybridity studies that have focused on how literacy practices position student identities (Brandt and Clinton 2002; Latour 1996; Leander and Sheehy 2004; McCarthey

Table 1.1 Axioms for a trans* pedagogy

We live in a time we never made, gender norms predate our existence;

Nongender and sexual “differences” have been around forever but norms operate to pathologize and delegitimize them;

Children’s self-determination is taken away early when gender is inscribed onto them. Their bodies/minds become unknowing participants in a roulette of gender norms;

Children have rights to their own (a)gender legibility;

Binary views on gender are potentially damaging;

Gender must be dislodged/unhinged from sexuality;

Humans have agency;

We must move away from pathologizing beliefs that police humanity;

Humans deserve positive recognition and acknowledgment for who they are;

We are all entitled to the same basic human rights; and,

Life should be livable for all.

and Moje 2002), and to other studies which have focused on how histories have spatial dimensions that are normalized with inequities hidden in bodies whereby bodies becomes contested sites that experience social injustice temporally and spatially (Miller and Norris 2007; Nespor 1997; Slattery 1992, 1995). This book offers readers insight on how teachers mediate these axioms that bodies are not reducible to language alone because language continuously emerges from bodies as individuals come to know themselves. Bodies can thereby generate and invent new knowledges or as Butler (2004) suggests, “The body gives rise to language and that language carries bodily aims, and performs bodily deeds that are not always understood by those who use language to accomplish certain conscious aims” (p. 199). Similarly, Foucault (1990) reminds us that the self constitutes itself in discourse with the assistance of another’s presence and speech. Therefore, when trans* and gender creative youth experience the simultaneity of both self and social recognition, they are less likely to experience the psychic split or double consciousness that DuBois (1903) called debilitating.

Building upon these frames, a theory of trans*ness aligns with geospatial theory mediated by a “spatial turn” (Soja 2010), or a rebalancing between social, historical, and spatial perspectives, whereby none of these domains is privileged when reading and interpreting the world (p. 3), rather, they are viewed in simultaneity. This connection between these theories therefore presumes that geographies are beholden to geohistories (Miller 2014), or the ideological practices that shape a collective history of a people and a place, revealing a society’s dominant view through acts of social justice and injustice, reinforced through policy and patterned absences of language (Massey 2005; Soja 2010). Combined, such theories inform a critical consciousness about how we read and are read by the world (Freire 1970).

TEACHERS APPLYING A TRANS* PEDAGOGY: CLASSROOM AS SPACE FOR RECOGNITION

The classroom as a space, encumbered by the inheritance of myriad geohistories, is shaped by the deployment of policies that typically affirm or negate the body’s drive for true expression and recognition. When policies, or a lack thereof, are made visible through discussion or units of study, such as banning a gay–straight alliance, or states that have no promo

homo laws, or do not enumerate specific kinds of bullying, or share with students that their country lacks federal anti-bullying laws, studying these macroaggressions through schools’ codes of conduct and examining school climate through the eyes of students, teachers can begin to enact what I see as the strongest mediator of a trans* pedagogy: refusal. Refusal is a strategy that teachers can take up to support their students in developing positive identities. Through models of refusal that will be explored in subsequent chapters throughout the book, the teachers, in drawing from the axioms, disrupt binary constructions of gender and introduce new tools that support students in their critique of the world.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR WORKING THROUGH THE BOOK

Across the millennial generation of pre-K-12 in myriad school contexts, both nationally and internationally, we see a growing number of youth who eschew gender and sexual labels, who embody what seems to them to be self-determined authentic identities, and who are proleptically changing the landscape of school and society writ large by pushing back on antiquated gender norms. Faced with these realities, teachers across all grade levels and disciplines are challenged to mediate literacy learning that affirms these differential realities in their classrooms. That said, how can teachers move beyond discussions relegated to only gender and sexuality and toward an understanding of a continuum that also includes the (a)gender complexities students embody? How can teachers undo restrictively normative conceptions of sexual and gendered life, unhinging one from the other, and treat them as separate and distinct categories? Even more critical, how can we support emerging literacy professionals and inservice literacy teachers to develop and embody the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to help all students learn while simultaneously supporting them to remain open to redefinition and renegotiation when they come up against social limits?

This affirming book forges a pathway for teachers who work with or will work with trans* and gender creative youth as they address such fundamental questions and provide literacy teacher educators and subsequent researchers examples for future study through models of a flexisustainable6 curriculum design (some aligned to standards), pedagogical knowledge and applications, and assessments across pre-K-12 literacy contexts, either/or in and out of school, by highlighting affirming texts across genres, media representations, models for inclusion and differentiation,

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

our Abbey, will see that this is so; and besides these, our Abbey held other lands as well, so that when Sherborne ceased to be the caput of this fair estate, much that had once come our way ceased to come hither any more. Though the presence of the school here has in later times done much to redeem this loss, one cannot say that it has entirely done so.

T�� E������� �� S�������� S�����.

Of all the ancient institutions in Sherborne, that one which has kept its dwelling-place longest, which is to-day what it was before Wessex became one with England, is Sherborne School. The old Castle is a ruin, the Almshouse dates only from the fifteenth century, the Abbey Church became the parish church only in 1540. But the School, though it suffered pecuniary loss in 1539 by the dissolution of the monastery, suffered no breach of continuity; it was in existence when the Almshouse was founded, it educated St. Stephen Harding in the eleventh century, and we have no reason to think that its existence suffered any break from Ealdhelm’s day till then. A school with such a history may well call forth some reverence from those who love Wessex and know something of its history. Our school has roots which stretch down into the very beginnings of things Christian among the West Saxons, and there is certainly no existing school in Wessex that can rival its claim to antiquity

Sherborne School is fortunate in possessing many ancient documents illustrative of its history; among these special mention must be made of a series of accounts commencing in 1553 and continuing to the present time. Only eleven are missing. Till towards the end of the eighteenth century they are written on rolls of parchment, and are for the most part in excellent condition. Besides these there are a few early court rolls of the school manors at Bradford Bryan and Barnesby, Lytchett Matravers and Gillingham, and schedules and leases of its other lands. Among these documents, too, are records belonging to the old chantries, with the lands, of which Edward VI. endowed the school; some of these go back to the reign of Henry VII.

There is no existing minute book of the governors’ proceedings older than that which begins in 1592; but, luckily, a draft of minutes exists relating to the years 1549 and 1550, relating, that is to say, to the time of transition from the old condition of things which obtained before the dissolution of the monastery, to the new condition created by the charter granted to the school by Edward VI. The series of minute books from 1592 onward is complete.

From the school statutes much can be gathered about the character of the education given in the school. The oldest statutes of the post-Reformation epoch are lost; they were based, as we learn from the accounts, on those drawn up by Dean Colet for his school, once attached to St. Paul’s Cathedral. In 1592, however, a new set was drawn up for the School of Sherborne by its visitor, Richard Fletcher, Bishop of Bristol, who, as Dean of Peterborough some years before, had imposed on him the terrible task of attending Queen Mary Stuart on the scaffold. Great stress is laid in these statutes on the “abolishing of the Pope of Rome and all fforrein powers superiorities and authorities.” From time to time after this new statutes were made to suit the changing educational and political views. The statutes all still exist, except those made in 1650 by the Puritans; of these all trace is lost, except the bill for engrossing them, which amounted to 25s. Statutes were drawn up in 1662 by Gilbert Ironside, Bishop of Bristol, which the Governors were unwilling to accept, because by these statutes the headmaster was protected from arbitrary interference on the part of the Governors. It was not till 1679 that Bishop William Gulston succeeded in making them accept a new body of statutes, which contain almost all that Gilbert Ironside proposed, together with some additional matter. In Bishop Ironside’s draft and Bishop Gulston’s statutes, it is laid down that it is never lawful “for subjects to take up armes agt theire Soveraigne upon any pretence wtsoever.” The language used in and out of school in all official matters was Latin, and no scholar was to go about the town alone, but with “a companion one of the Schollars that may be a witness of his conversation and behaviour under penalty of correction.” The system of monitorial rule has always been in vogue in the school; in 1592 these rulers are called Impositores—a somewhat awkward term one must admit; in 1662 and 1679 they are called Prepositores; nowadays they are called Prefects In 1679 they were four in number: “One for discipline in the Schoole, to see all the Schollars demeane themselves regularly there, the Second for manners both in the Schoole and abroad any where, the Third for the Churche and Fields, the Fourth to be Ostiarius, to sitt by the doore, to give answere to strangers and to keepe the rest from running out.”

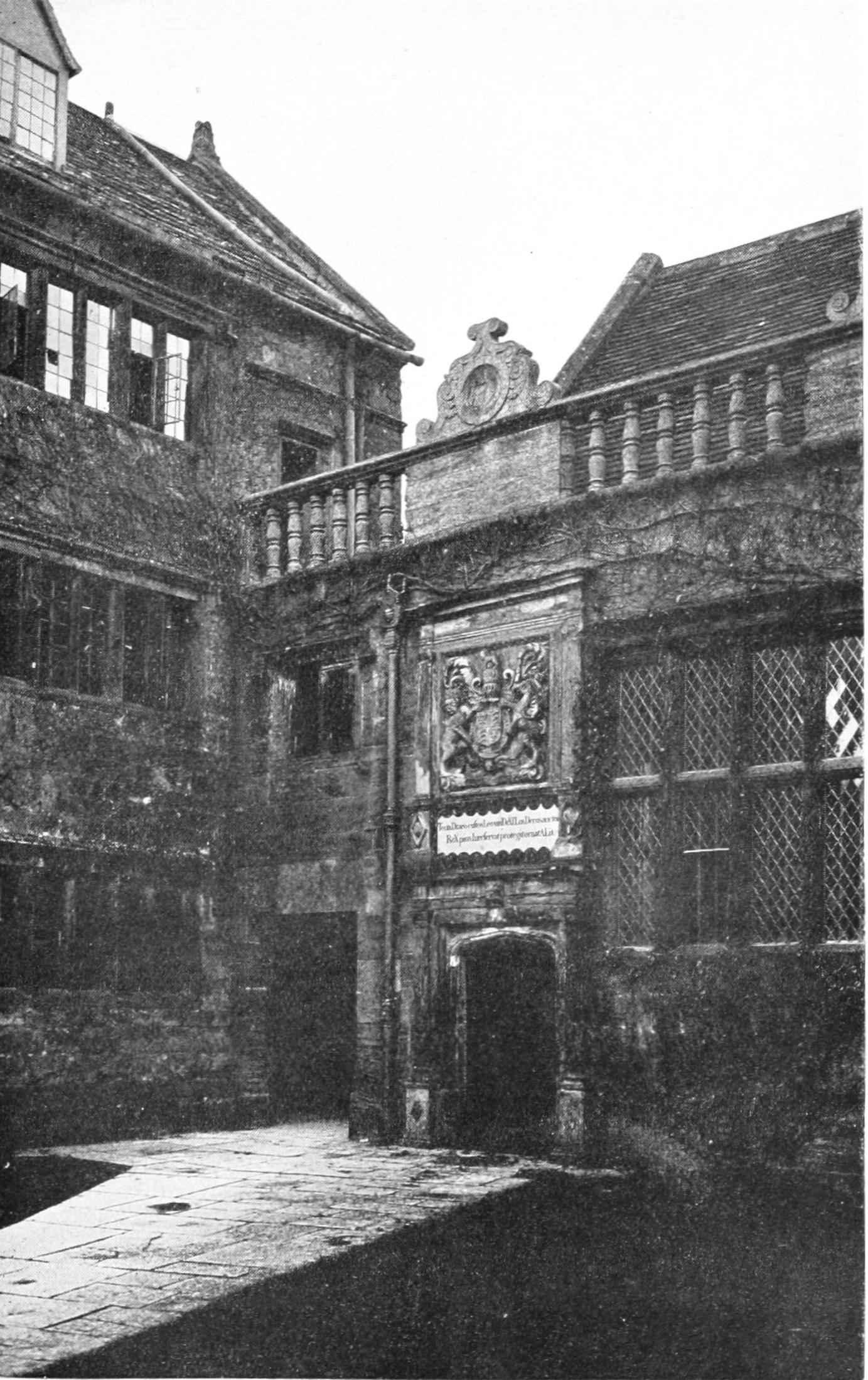

When the assizes were held at Sherborne, the judge sat in what is now the schoolhouse dining-hall—it was then the big schoolroom; and just before the assizes took place, we get from time to time an entry of the following kind in the school accounts: “for washinge of ye King, 6d.” The King referred to is the statue of Edward VI., which still adorns the room; it is of painted Purbeck marble, and is the work of a certain Godfrey Arnold; it cost £9 5s. 4d., and was set up in 1614.

The two royal coats of arms, which may still be seen on the south wall of the old house of the headmaster, and over the south door of the schoolhouse dining-hall, were taken down by order of a Commonwealth official in 1650; but they were carefully preserved, and were restored to their old positions at the Restoration. That on the old house dates from 1560; that on the dining-hall from 1607. They used to be bright with tinctures and metals, but since 1670 they have been “only washed over with oil or some sad colour, without any more adorning.” The chronogram on the dining-hall is unique, for it can be made to give two different dates, according to the ways in which the significant letters are taken. Mr. Hilton, our chief authority on chronograms, knows of no other which gives two dates in this fashion. The first date which our chronogram gives is 1550, the date of the granting of the charter; the second date which it gives is 1670, that of the rebuilding of the dining-hall.

Among other school buildings of ancient date we must not omit the library, partly of the thirteenth century, but certainly restored in the fifteenth; and the school chapel, with its undercroft of the twelfth century, and its upper story of the fifteenth. The undercroft is a very precious relic of the past, but the school chapel, which was once the Abbot’s Hall, has undergone changes and additions; it still keeps its fine fifteenth century timber roof. The library, on the other hand, has gone through little change. It was the Guest House of the Monastery, and has kept its timber roof of the fifteenth century. It is curious that the windows on the east side of the room are not quite opposite those on the west side, nor is the divergence uniform; the large window in the south end of the room is not in the middle of the wall, but rather towards the west side.

The modern buildings of the school harmonize well with the older work, for they are all built of the same lovely stone, and the style in which they are built, though it is in no sense an imitation of this older work, is yet in harmony with and worthy of it. One of these buildings deserves more than passing notice, viz., the new big schoolroom, completed in 1879. The whole group of buildings, with its surroundings, classrooms, museum, laboratory, drawing school, music house, Morris tube range, bath and fives courts, deserves more attention than it usually gets from visitors to Sherborne. These sojourners often forget that the north side of the exterior of the church is likely to be as interesting as the south side; if once they take the trouble to get to this north side, they will be surprised to find how much fine work, ancient and modern, is to be seen there.

Sherborne Old Castle is situated on an elevated piece of ground to the east of the town; this ground is about 300 yards long by 150 yards broad; the surface has been made level, and an oval area, 150 yards long by 105 yards broad, has been traced out, and its edges scarped to a steep slope, with a ditch about 45 feet deep. The material taken away in forming this scarp and ditch has been thrown outward, so that the counter scarp is formed of a mound more or less artificial. It was within this area, above described, that our Pageant of 1905 was given.

The remains of the Castle are as follows: parts of the curtain wall, with the gatehouse, the keep, the chapel and hall, along with other parts of the domestic buildings—all ruinous. The builder of this castle was Bishop Roger; and William of Malmesbury, who knew it well, has described the masonry in glowing terms. All that remains is of this Norman period, though it was somewhat restored and altered in the fifteenth century. The keep belongs to the class of square keeps. To judge from two windows of the chapel which still remain in a fragmentary condition, that building must have been of a very ornate character. The barrel vaulting of the basement of the keep is worth study, and a Norman pillar, still standing and supporting a quadripartite vault, is well known to students of architecture. There is also a Norman chimney with three flues in the gatehouse.

The ruinous condition of the Castle is not so much due to time as to gunpowder, for in 1645, after the Castle was taken by Fairfax, it was blown up by order of the Long Parliament, so as to be no longer tenable as a fortress. After this, while the troops of the Parliament occupied Sherborne, their barracks were the school, and their “Court of Guard” the schoolhouse dining-hall.

This is not the place to deal with the vicissitudes in the tenure of Sherborne Castle—how the Bishops of Sherborne lost and regained it. It finally passed from Bishop Henry Cotton into the hands of Queen Elizabeth in 1599. Sir Walter Ralegh had, however, been tenant of it since 1592, and when Queen Elizabeth got the feesimple of it, she gave it to Ralegh. Ralegh, however, did not care to live in it; other magnates in this part of the world were building fine modern houses, and he followed their example. Thus arose the modern Castle, known in former days as Sherborne Lodge, on the other side of the lake, the central and loftier part of which is due to Ralegh. There is no trace of any evidence that Sherborne Castle was ever besieged before the great Civil War. It was used at times in the Middle Ages as a prison; for example, in King John’s reign. King John himself stayed here in 1207 and in 1216.

After some tragic vicissitudes the Sherborne estate came to the Digbys in 1617, and since this date, with the exception of the troublous period of the great Civil War, it has remained with them.

Sherborne Castle was twice besieged during the Civil War, first in 1642, and again in 1645. The first siege was uneventful and unimportant. In 1644 Charles I. had been here after his successful campaign in the West; Prince Rupert, too, had come, and there had been great doings with reviews of men in Sherborne Park, after which followed the second battle of Newbury and the self-denying ordinance and the creation of the New Model. The second siege, that of 1645, was more important; not only was Fairfax drawn hither by it, but Cromwell, too, came as general of cavalry. Though the Parliamentary troops destroyed much of the old castle that we should like to see standing now, we must, on the whole, acquit them

of having done any great injury to the buildings of the church or school.

In 1688, King William III.—then Prince of Orange—on his advance from Exeter to London, stayed in the modern castle here; his proclamation to the English people is said to have been printed in the drawing-room at a printing-press set up on the great hearthstone, which was cracked by it.

Let us now turn to the last of our four ancient institutions, viz., the Almshouse. This institution is certainly older than the year 1437, in which year, by a license from King Henry VI. to Robert Nevile, Bishop of Sarum, to Humfrey Stafford, Kt., Margaret Goghe, John Fauntleroy, and John Baret, it was refounded in honour of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist. It is actually older than this, because some accounts of the charity exist for a few years prior to this date. Some day, no doubt, the history of the institution will be more fully worked out than it is at present. Plenty of material exists in its account rolls which could hardly fail to throw light on old Sherborne life.

According to the deed of foundation, there were, we are told, to be twenty brethren, called the Masters of SS. Johns’ House—they are now called master and brethren—together with a perpetual priest to pray for the good estate and the souls of the founders and inmates. The house was to contain twelve poor men and four poor women, who were to be governed by one of themselves, called the Prior, of their own election, and a woman of domestic ability was to buy their food and dress it, wash their clothes and make their beds, who should be called the Housewife of SS. Johns’ House. The older part of the building was finished in 1448, and here still stand, not much altered from what they were then, the chapel, ante-chapel, and dining-hall, with a long dormitory over the dining-hall; this dormitory used to open into the chapel, so that the sick and infirm might hear the service, and, so far as they could, join in it. The chapel contains an interesting triptych of the fifteenth century by a Flemish artist, name unknown. One cannot imagine a more desirable haven of rest than this for those who are fortunate enough to become its inmates.

Enough has now been told to show that among old English towns Sherborne holds a peculiarly interesting place. It still keeps much of its old-world look and ancient dignity, and its inhabitants, many of whom bear the names of the old stock who were living here in in the time of Henry VI., are a kindly race, among whom it is a pleasure and a privilege to live.

MILTON ABBEY

B� ��� R��. H������ P�����, M.A.

HE county of Dorset is one of the few counties in England that contain three great minsters in good repair and in parochial use—Sherborne, Wimborne, and Milton. And each of these minsters is of Saxon and Royal foundation. King Athelstan, the grandson of Alfred the Great, founded the Monastery and Collegiate Church of Milton for Secular Canons, in or about the year 938. In the year 964 King Edgar and Archbishop Dunstan of Canterbury converted the monastery into an abbey, with forty Benedictine monks, and chose a very able man, Cynewearde (or Kynewardus), as the first Abbot. This Cynewearde, a few years afterwards, to the loss of Milton, was made Bishop of Wells.

The original minster built by Athelstan was a noble stone building of its time, and was very rich in shrines and relics. The King gave a piece of our Saviour’s Cross, a great cross of gold and silver with precious stones, and many bones of the saints, which were placed in five gilt shrines. The bones of his mother were also brought to the church (for burial). We also know that the Saxon Minster was restored and enlarged, if not rebuilt, in Norman times. It has been reasonably conjectured that the size of the Norman Abbey was that of the choir and presbytery of the present church. Some large fragments of Norman masonry have been dug up,[23] which show that the Norman Abbey was a building of some considerable architectural pretensions; and encased in the south wall of the present choir and presbytery are the remains of two enriched Norman arches which escaped destruction in the fire of 1309. In that year the church was struck by lightning, and was almost entirely burnt to the ground. Thirteen years later, however, under Abbot Walter Archer, the present Abbey Church was commenced on the

same site, but on a much larger and grander scale; and building operations went on, from time to time, until within a short period before the Dissolution in 1539.

K��� A��������.

Founder of Milton Abbey.

(From a Painting in the Church.)

“A��������’� M�����.”

Buried in Milton Abbey.

(From a Painting in the Church.)

The following styles of architecture are represented in the main portions of the church, built of stone from Ham Hill and Tisbury:— First Decorated, the choir and presbytery of seven bays, with aisles; Second Decorated, the south transept; Third Decorated, the two western piers of the “crossing”; Perpendicular, the north transept and central tower. The Perpendicular work was undertaken by the penultimate Abbot, William de Middleton, assisted by Bishop Thomas Langton, of Salisbury and of Winchester, the Abbey of Cerne, and the families of Bingham, Coker, Latimer, Morton, and others.

At the Dissolution, the Abbey estates were granted by Henry VIII. to Sir John Tregonwell, who had helped to procure the King’s divorce from Catharine of Aragon; but the whole of the Abbey Church was

preserved for the parishioners, with the exception of the Ladye Chapel, which was pulled down, although some of its vaulting shafts can still be seen outside the east end of the church. The last of the Abbots (John Bradley, B.D.), after leaving Milton in Tregonwell’s hands, was consecrated Suffragan Bishop of St. Asaph, with the title of Bishop of Shaftesbury,[24] and the Abbey Church of Milton then passed under the sole spiritual control of Richard Hall, Vicar of Milton, and his successors.

Unfortunately, the Abbey underwent a “restoration” in 1789, when the church was despoiled of many of its fittings; and chantry chapels

and other valuable objects of interest went down under the hand of the “restorer.” But Sir Gilbert Scott, in 1865, restored the church at the expense of the late Baron Hambro, and left the Abbey in its present beautiful condition, and, as far as was possible, in its original state.

T�� T���������.

The view of the church at the beginning of this chapter will save the necessity of a description of its exterior. But the interior contains

many things which demand notice.

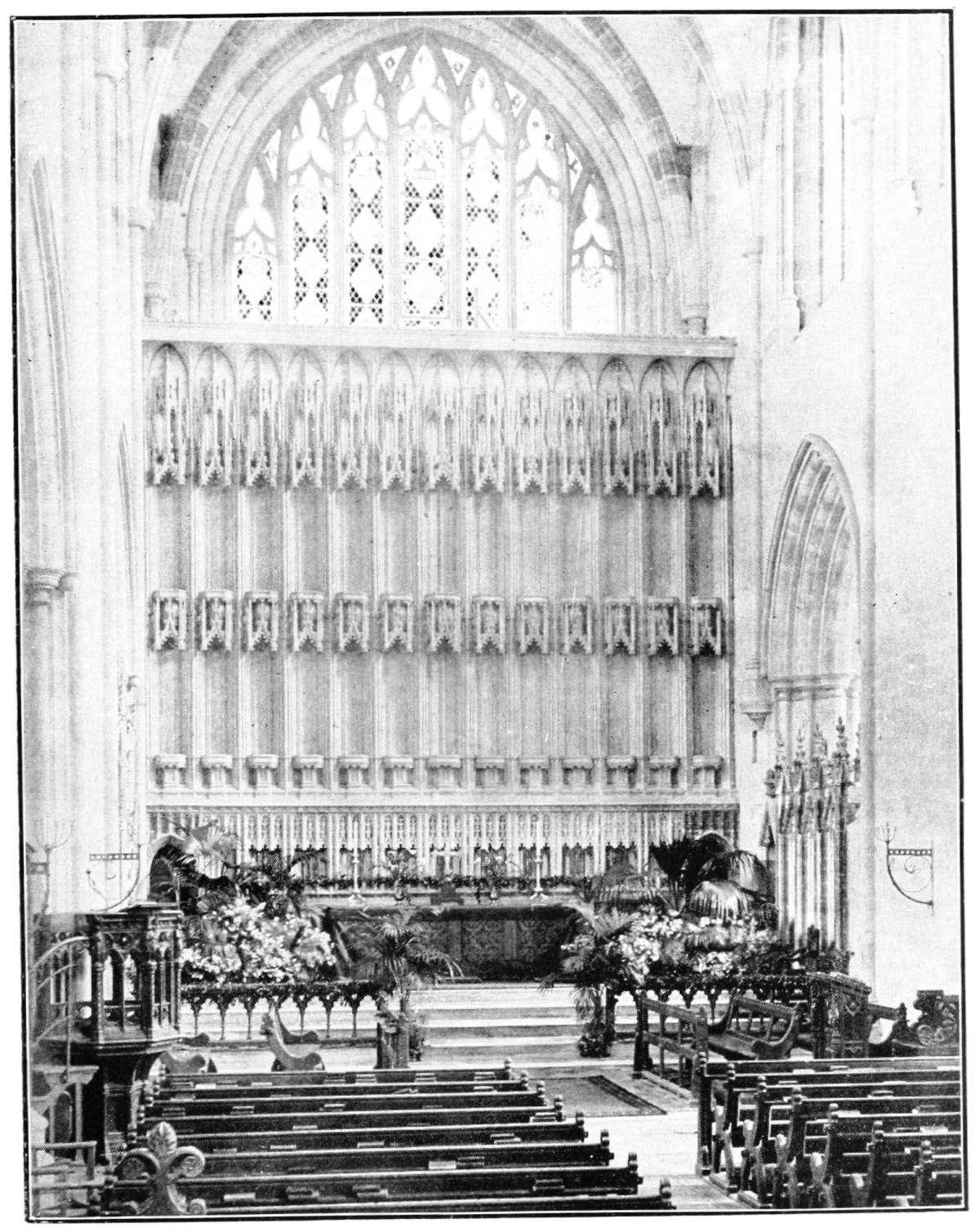

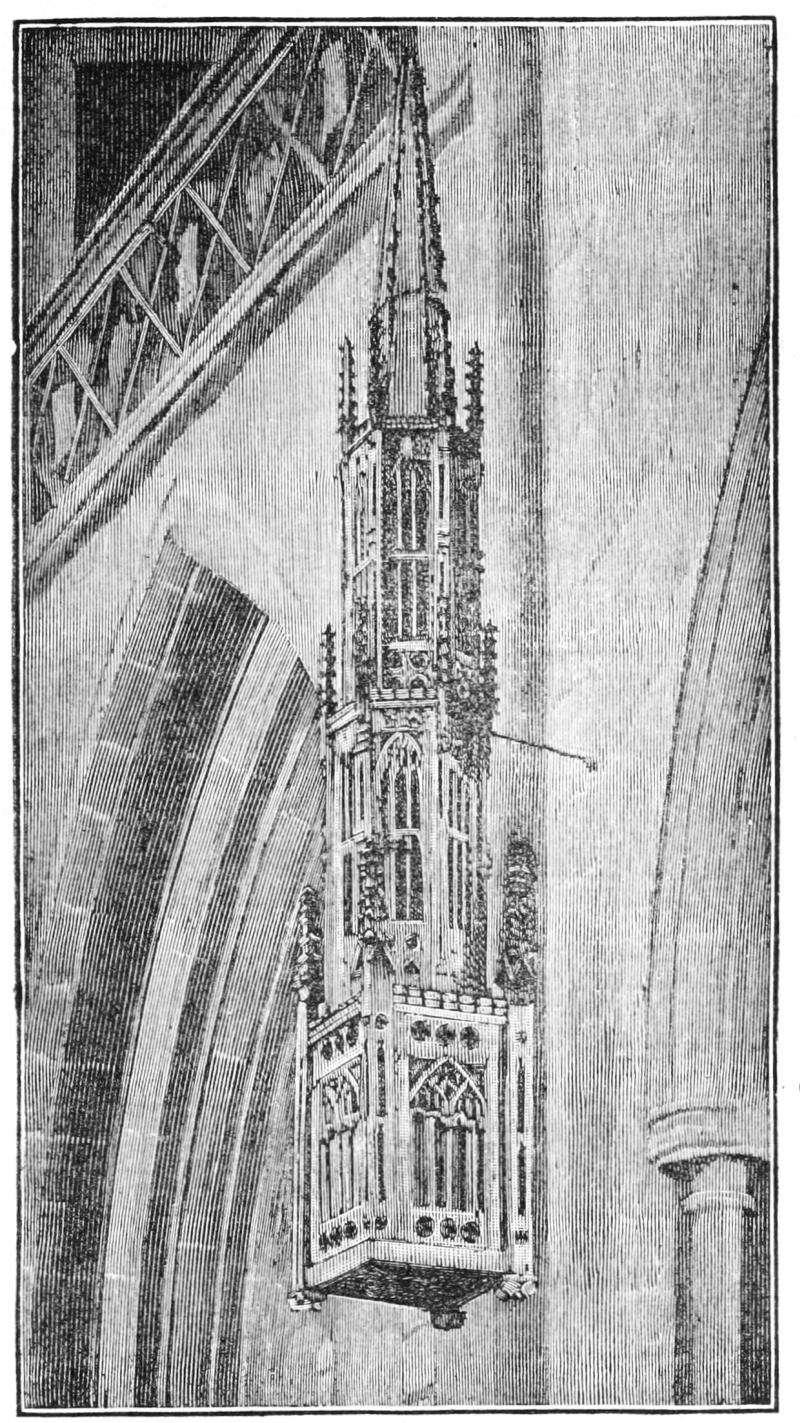

And first of all must be mentioned the “ornament,” which many antiquaries consider to be a Tabernacle for reserving the Eucharist. This very beautiful and richly carved “Sacrament-house” dates from the fifteenth century, and is made of oak in the form of a spire composed of four storeys, the lowest containing the opening through which the reserved elements may have been passed. It is not in its original position, but is now fastened to the west wall of the south transept beneath the triforium.

The great altar-screen is a very lofty, beautiful, and peculiarly rich construction, even though the two long rows of ornamental niches now lack the statues of the saints that once stood in them—saints with “very bluff countenances, painted in very bright colours and heavily gilded.” On its lower portion there is a Latin inscription, which bids prayers for the souls of William Middleton, Abbot of Milton, and Thomas Wilken, Vicar of the parish, who worthily decorated (“honorifice depinxerunt”) the screen in 1492. The three stone sedilia in the sanctuary are fine specimens. The bosses throughout the church are of very rich design.

The Abbey also contains two fifteenth century oil paintings of a crude description, one of which represents Athelstan, the founder, giving to the first head of the monastery a model of the minster (with three spires)[25] over which he was to preside. The other painting is supposed to represent Athelstan’s mother—Egwynna, “femina illustris.”[26]

The tombs of the abbots within the Abbey are most interesting. In front of the altar steps there is a Purbeck marble grave-slab of the fourteenth century, which was once inlaid with the brass figure of an abbot clad in pontificalia, with a marginal Latin inscription in Lombardic capitals:

ABBA : VALTERE : TE : FATA : CITO : RAPVERE : TE : RADINGA : DEDIT : SED : MORS : MALE : NOS : TVA : LEDIT.

This is the slab of an Abbot of Milton whose Christian name was Walter, and who was formerly a monk of Reading, probably Walter de Sydelinge, who died in 1315. In the north transept there is a thirteenth century grave-slab of another abbot. This slab is also of Purbeck marble, but the upper portion is broken off. The remaining portion shows part of an incised figure of an abbot, with pastoral staff, chasuble, stole, maniple, alb, and an imperfect marginal inscription in Norman French:

...RCI ⁝ LISET ⁝ LE ⁝ PARDVN ⁝ I ⁝ CI[27]

There are other large marble grave-slabs, without inscriptions, in the church, which are supposed to cover abbots, monks, and benefactors. On some there are the matrices of missing brasses. One, in front of the altar steps, shows the outline of a civilian in a plain gown, and his wife wearing a “butterfly” head-dress, with their five sons and four daughters, circa 1490. In St. John the Baptist’s Chapel, at the east end of the north aisle of the church, there is a small fifteenth century brass to John Artur, one of the monks of the Abbey, with a Latin inscription, which bids God have mercy on his soul. In the same chapel, a very fine coloured armorial brass over Sir John Tregonwell’s altar-tomb contains the latest tabard example on a brass in England (1565).[28]

But to mention all the ancient or modern memorials (some of wondrous beauty, such as those of Lord and Lady Milton, and Baron Hambro) would take far too much space. A marble tablet in the vestry informs the reader that John Tregonwell, Esquire, who died in the year 1680, “by his last will and testament gave all the bookes within this vestry to the use of this Abby Church for ever, as a thankfuld acknowledgement of God’s wonderfull mercy in his preservation when he fell from the top of this Church.” This incident happened when he was a child; he was absolutely uninjured, his stiff skirts having acted as a parachute.[29] The chained library of sixtysix leather-bound volumes comprises the works of the Latin and

Greek Fathers and other early Christian writers, and some standard theological works of the seventeenth century. The books have been kept at the vicarage for many years.

A���� M��������’� R����.

The abbey now contains very little painted glass.[30] There is a large “Jesse window” by the elder Pugin in the south transept, and some coloured coats of arms and devices of kings, nobles, and abbots in some of the other windows. The dwarfed east window contains the only pre-Reformation glass in the church.[31] The Abbatial Arms are emblazoned in several parts of the building. They consist of three baskets of bread, each containing three loaves. On one of the walls in the south aisle, near the vestry, there is the carved coloured rebus of Abbot William de Middleton, with the date 1514 in Arabic numerals—the 4 being represented by half an eight. It comprises the letter W with a pastoral staff, and a windmill on a large cask—in other words, a mill and a tun (Mil-ton). The old miserere seats still remain in the choir, but the carving thereon is not very elaborate, and many of them have been renewed. The inscriptions on the Communion plate (which consists of two large silver barrelshaped flagons, a bell-shaped chalice, and a large and a small paten) tell us that “John Chappell, Sitteson and Stationer of London,

1637,” and “Mary Savage, 1658,” and “Maddam Jane Tregonwell, widdow, 1675,” gave these to “Milton Abby.”

There are several other interesting things in the church, albeit not ancient—e.g., the rood-loft, the font, and the pulpit.

The rood-loft, although not entirely ancient, is composed of ancient materials. When the party-walls of St. John the Baptist’s Chapel, the chantry of Abbot William de Middleton, and other side-chapels, were destroyed or mutilated at the “restoration” in 1789, some of the materials were used to reconstruct the rood-loft. The eastern cornice, for instance, is probably a portion of Abbot Middleton’s chantry, and bears thirteen coats of arms, including those of the Abbeys of Milton, Sherborne, and Abbotsbury, and the families of Chidiock, Latimer, Lucy, Stafford of Hooke, Thomas of Woodstock, and others.

The font of the Abbey, in the south transept, is modern, but of unusual design. It is composed of two beautiful life-sized white marble female figures, representing Faith and Victory, with a baptismal shell at their feet.

Near the font is an oak case containing a fourteenth century coffin chalice and paten, and fragments of a wooden pastoral staff and sandals, discovered during the restoration of the church in 1865.[32]

The pulpit is also modern, of carved oak; but it is interesting, because it contains statues of all the patron saints connected with the Abbey and the parish, and of these there are no fewer than six, viz.: St. Sampson of Dol, St. Branwalader,[33] St. Mary the Blessed Virgin, St. Michael the warrior-archangel, St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. James the Great.

St. Catherine of Alexandria is the patron-saint of “King Athelstan’s Chapel,” which stands in the woods at the top of the hill to the east of the Abbey. And this little church has also had a history well worth the telling. When Athelstan was fighting for his throne he had to pass through the county of Dorset, and he encamped on Milton Hill, and threw up an earthwork, or made use of one already existing there,