I Heard Her Call My

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/i-heard-her-call-my-name-a-memoir-of-transition-1stedition-lucy-sante/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Know My Name: A Memoir Chanel Miller

https://textbookfull.com/product/know-my-name-a-memoir-chanelmiller/

Last of Her Name 1st Edition Jessica Khoury

https://textbookfull.com/product/last-of-her-name-1st-editionjessica-khoury/

Call Me American A Memoir Abdi Nor Iftin

https://textbookfull.com/product/call-me-american-a-memoir-abdinor-iftin/

My dead parents a memoir First Edition Yurchyshyn

https://textbookfull.com/product/my-dead-parents-a-memoir-firstedition-yurchyshyn/

My dad Yogi a memoir of family and baseball Barrett

https://textbookfull.com/product/my-dad-yogi-a-memoir-of-familyand-baseball-barrett/

Be Not Afraid of My Body A Lyrical Memoir 1st Edition

Darius Stewart

https://textbookfull.com/product/be-not-afraid-of-my-body-alyrical-memoir-1st-edition-darius-stewart/

Funded How I Leveraged My Passion to Live a Fulfilling Life and How You Can Too Lucy Gent Foma

https://textbookfull.com/product/funded-how-i-leveraged-mypassion-to-live-a-fulfilling-life-and-how-you-can-too-lucy-gentfoma/

My Beautiful Monsters 03.0 - The Call of Monsters 1st Edition J.B. Trepagnier

https://textbookfull.com/product/my-beautiful-monsters-03-0-thecall-of-monsters-1st-edition-j-b-trepagnier/

I Will Be Complete A Memoir First Edition Gold

https://textbookfull.com/product/i-will-be-complete-a-memoirfirst-edition-gold/

ALSO BY LUCY SANTE

NineteenReservoirs

MaybethePeopleWouldBetheTimes

TheOtherParis

FolkPhotography

NovelsinThreeLines

KillAllYourDarlings

TheFactoryofFacts

Evidence

LowLife

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2024 by Lucy Sante Penguin Random House supports copyright.Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture.Thankyou for buying an authorized edition of this bookand for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission.You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Sante, Lucy, author.

Title: Iheard her call my name : a memoir of transition / Lucy Sante.

Description: NewYork: Penguin Press, 2024.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023019672 (print) | LCCN 2023019673 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593493762 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593493779 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sante, Lucy.| Transgender people—Biography.

Classification: LCC HQ77.8.S353 A3 2024 (print) | LCC HQ77.8.S353 (ebook) | DDC 306.76/80092 [B]—dc23/eng/20230830

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023019672

LC ebookrecord available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023019673

Cover design: Lucy Sante

Cover image: “Maquillage” by Deborah Turbeville / MUUS Collection

DesignedbyAlexisFarabaugh, adaptedforebookbyCoraWigen pid prh 6.2 146139107 c0 r0

CONTENTS

Cover

AlsobyLucySante

TitlePage

Copyright Epigraph

I HeardHer CallMy Name

Acknowledgments AbouttheAuthor

Beware ofallenterprises that require new clothes,andnot rather a new wearer ofclothes.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, WALDEN

Between February 28 and March 1, 2021, I sent the following text as an email attachmenttoaroundthirtypeopleIconsideredmyclosest,mostconsistent,day-todayfriends.WhileIsenttheemailsoutindividually,thesubjectlinewasusuallythe same:“Abombshell”Ismirkedattheunintentionalpunandwonderedwhetheranyoneelse would.Itwassimplytitled“Lucy.”

ThedamburstonFebruary16,whenIuploadedFaceApp,foralaugh.Ihad triedtheapplicationafewyearsearlier,butsomethinghadgonewrongandit had returned a badly botched image. But I had a new phone, and I was curious The gender-swappingfeature was the whole point for me, andthe firstpictureIpassedthroughitwastheoneIhadtriedbefore,takenforthat occasion.Thistimeitgavemeafull-faceportraitofaHudsonValleywoman inmidlife: strong, healthy, clean-living. She also hadlovely flowingchestnut hairandaverysubtlemakeupjob.Andherfacewasmine.Noquestionabout it—nose, mouth, eyes, brow, chin, barring a hint of enhancement here or there.Shewasme.WhenIsawherIfeltsomethingliquefyinthecoreofmy body Itrembledfrommyshoulderstomycrotch IguessedthatIhadatlast metmyreckoning.

VerysoonIwasfeedingeveryportraitandsnapshotandID-cardpictureI possessedofmyselfintothemagicgenderportal ThefirstarchivalpictureI tried, contemporaneous with my first memory of staring into a mirror and arrangingmyhairandexpressiontolooklikeagirl,wasananxious,awkward studioportraitofatween,allcowlicksandbabyfat Thetransformedresult

wasarevelation:ahappylittlegirl Apartfromherlongblackhair,verylittle hadbeendone to transformLuc into Lucy; the biggest difference was how much more relaxed she looked. And so it generally went—I was having a muchbettertimeasagirlinthatparallellife Ipassedeveryerathroughthe machine,experiencingoneshockofrecognitionafteranother:That’sexactly who I wouldhave been The appsometimes returnedblandly misjudgedor grotesquelydistortedimages,but more oftenthannot it weirdlyseemedto guesswhatmyhairstyleandfashionchoiceswouldhavebeeninthoseyears. Thelessalteredtheresultingimageswere,thedeepertheyplungedadagger intomyheart. Thatcouldhavebeenme!Fiftyyearswereunderwater,and I’dnevergetthemback Myhigh-schoolgraduationportrait,ahaughtynearprofile, hair waving off the brow and into a curl, became an impossibly delicate almond-eyed fawn (age 17 was indeed the summit of my beauty, whichisprobablywhymymale incubusimmediatelygrewa beard). Tenor twelve years later (there are regrettably few photos of me inmy 20s; I’ve always beencamera-shy),I ama Lower East Side postpunk radicallesbian anarcha-feminist with a Dutch-boy bob and a pout. Here I am at a Sports IllustratedjunketinArizona,age33,lookingdemureinawhitesweaterover aredpolka-dotdress,talkingtoaboy.

There are many reasons why I repressed my lifelong desire to be a woman Itwas,firstofall,impossible Myparentswouldhavecalledapriest and had me committed to some monastery, lettredecachet–style. And the culturewasfarfromprepared,ofcourse IknewaboutChristineJorgensen whenIwasfairlyyoung,butsheseemedtobeanisolatedcase.Mostlywhat youcameacrosswereaggressivelyvilejokesfromVegascomediansandthe occasional titillating tabloid story. Nobody felt threatened by transgender people; on the contrary, they were viewed as hilarious sideshow acts literally and otherwise, as in Weegee’s photographs I kept searching for images or stories of girls like me, without much luck. I would swoon over picturesfromFinocchio’sor Club 82 I mightfindinpassing,buttheir stars mostly seemed to be gay men who changed back into male drag after the show. Over the years I consumed an impressive amount of material on transgender matters, fromclinical studies to personal accounts (where are you,circa-1984issueofActuel—orwasitTheFace?—thatnearlybrokemy mind?),tonew-journalisticexposéstoporn Notmuchoftheporn,though;it grossedmeout.IresearchedthesubjectasdeeplyasIdidanyofmybooks, butmynotesallhadtobekeptinmyhead.

Iimmediatelydisposedofallmaterials,becauseIwasterrifiedofbeing seen. When with some regret I threw away a pseudo-scientific piece of exploitationcalledTheTransvestites,Imadesuretoburyitinthecenterof the trashbag. Untilbrowsersmade anonymoussearchingpossible,I wiped thesearchmemoryonmycomputereveryday Why,youmayask,didIfeelit necessarytogotosuchlengths?TheshortansweristhatI’mmildlyparanoid aboutwritingsonpaper(orscreen)becausemymotherregularlyraidedmy room,readinganythinginmyhandwritingandvettingallprintedmatter for anythingthat might evenremotelyallude to sex. I extendedthat cautionto my friends, most of whomwouldsurely have beensympathetic, because of thenotionIlongpossessedthatwomenwouldbedisgustedandrepelledby mytransgenderidentity.WheredidIgetthatone?ItmaybebecauseuntilI

wasinmylateteensIdidn’tknowmanywomen,asanonlychildofisolated immigrants, andalthoughI hadone early romantic interest, I didn’t have a female frienduntil I was seventeen. It may also very well have come from proto-TERF sentiments I picked up fromfeminist tracts Needless to say, I wasawfulatsex.Ididnotknowhowtoactlikeamaninbed.Iwantedtosee myself as a womaninthe act of love, but I also hadto repress the desire, whilesimultaneouslytryingearnestlytopleasemypartner(becauseIalmost never sleptwithanyoneIdidn’tloveatleastatfirst). Mostofthetime,the mass of contradictions prevented me from any but the most mechanical sexualfulfillment,andnecessarilyimpededmycompanion’spleasureaswell.

Iwasnotatallattractedtomen,andIspentenoughtimeingayenvirons inthe’70stobesureofthat.AtpubertyandafterwardIwasuncertainhow to construct a masculine identity I hated sports and dick jokes and beerchugging and the way men talked about women; my idea of hell was an evening with a bunch of guys. Over the years, from force of necessity, I created a male persona that was saturnine, cerebral, a bit remote, a bit owlish, possibly “quirky,” coming very close to asexual despite my best intentions DuringthosesameyearsIthoughtaboutmytransidentityevery singleday,sometimesalldaylong. Ihadarangeofmasturbationscenarios: cast as a girl in the school play, then persuaded to go out on the town in costume; hired as an assistant by a wealthy society woman who amuses herselfbydressingmeupasagirl;newroommateassignedtomeincollege hasbeendressingasagirlforyearsandhasafullwardrobe Yes,theywere transvestite fantasies,but that waswhat seemedavailable. Just the idea of wearingwomen’sclothesmademedizzy,andIcancountthenumberoftimes Idressedup(furtively,alone)onthefingersofonehand.Ilookedlovely,butI felt as thoughthe entire worldwas lookingonincontempt or repulsionor direjudgment ButthenIcouldn’tjustwishmyselfintomagicallybecominga girl,couldI?AndwhenItrulyprobedmydesiretohavebreastsandavagina Iwassuffusedwithanexistentialterror

Another reason for my repression was my sense that if I changed my gender it would obliterate every other thing I wanted to do in my life. I wanted to be a significant writer, and I did not want to be stuffed into a category, any category. At first, writing seemed to be a pursuit where one couldhone a persona withwords while evadinginspectioninthe flesh, but marketingchangedthat,brutally,beginninginthe’80s;Icouldnolongerhide there, and if I were transgender that fact would be the only thing anyone knewaboutme.Overtheyears,transgenderpeoplebecamegraduallymore visibleinthemedia,andthecoveragebecamealittlebitlesssnide.Ilivedin New York City, so I saw transgender people often: the doo-wopgroupthat livedaswomenintheWhitehallHotelon100thStreet,thetwoverypolished partygirlsintigerprintsIsawoneearlymorninginthesubway Afewyears later I passed through the same circles as Greer Lankton and Teri Toye, althoughIwastooscaredtoevertalktothem;theyseemedlikemythological creatures come to earth For that matter I was close for a while to Nan Goldin, who would have been certain to understand my story, but I never breathedaword Iwouldhearrumorsthatthisorthatperson“dressedup,” andIwouldbeforeverillateaseintheirpresenceasaresult—fromenvy,of course. My office in the late eighties and early nineties was a block from

TompkinsSquarePark,butIneversomuchaspeekedinatWigstock(Icould hear it), and half a block from the Pyramid Club, but I never went there, either,except maybe to see some band. Inthose daysthe club hada black menu board on the sidewalk outside that read “Drink and be Mary” I trembledeverytime Ipassedit. I’doccasionallysee skitsonthe UHFporn channel by persons calling themselves “chicks with dicks,” and know they were somewhere in my neighborhood, maybe very close by. In the late ninetiesIwasinvitedtothedinnerafterNan’sWhitneyopening,andseated atmytablewasthegloriousJoeyGabriel;I’mnotsureIspokeawordduring thewholecourseoftheevening.

I was terrified, that is, of finding myself confronted by what I am confronting now. Somehow now the dam has burst, the scales have fallen away,thefoghaslifted Thevariouslistsabovegivebutasmallideaofthe vast scope of my investment in my transgender identity. I absorbed every factoid, every anecdote, every historical speculation, every scabrous rumor pertainingtothematterofboyschangingintogirls Icontinuallyconjuredup, reveled in, and suppressed images of myself as a woman. It was the consuming furnace at the center of my life And yet, until these past few weeks, my repression kept me from seeing the phenomenon as a coherent whole. I wanted with every particle of my being to be a woman, and that thought was pasted to my windshield, and yet I looked through it, having trainedmyselftodoso.NowthatthefloodgateshaveopenedIamconsumed bythethoughtinanewway Ihavespokenfranklytomytherapistaboutit, makingherthefirsthumanbeing(afternineortenpreviousshrinks)tohear thosethingsfrommylips.Thatgivesthemattertheforceofreality.WhenI uploadedmyfirstpicturetoFaceAppIfeltliquidandmeltinginthecoreofmy body.NowIfeelacolumnoffire.

Thatshouldnot,however,implyasteelyresolve NowthatIhaveopened Pandora’sbox,Icannotcloseitagain,buthavenoideawhattodowiththe spectersithasletloose Theideaoftransitioningisendlesslyseductiveand endlesslyterrifying.Itakeatleastoneselfieeverydayandtransformit,and itfeelsasthoughthepicturesarebecomingevermoreplausible.Yes,that’s clearly my face, every bit of it—my features are fortunately disposed, and eventhecontoursofmyfacearenotexcessivelylarge.Withabitofmakeup, a course of estrogen, and a really nice wig I could look exactly like that, maybe. Butwillthe factthatIcan’tgrowmyownhair make me feellike a fakeforever?Itdoesn’ttakemuchtomakemefeelfake—themuchimproved social climate of the present, the very thing that has made this recent epiphany at all possible, also makes me think that others will see me as merelyfollowingatrend,maybetostayrelevant AndIamsoontoturn67 What if I look like a grotesque? Or merely pathetic? While I know that my friends and the people I know in publishing and the arts would be sympathetic, and that my main employer is exceptionally trans-friendly, I worry about private reactions. I myself have not always been kind when someoneinpubliclifeorontheperipheryofmysocialorbithastransitioned in ways I thought less than successful or less than dignified. I’m worried about having the talk with my son, although like many members of his generationhehastransgenderfriendsandisveryopentothesubject.Most ofallIworryabouttellingmypartner,withwhomI’vesharedanaffectionate

relationship that has slowly become more companionate over the past fourteenyears. Idon’tdoubther sympathy,butcanalsoimagineher asking what her role might be, as if to say that I am living out a love affair with myself Andwouldshefeelcomfortablewithmywearingfeminineclothesand accessorieswhileshewearsmostlyT-shirtsandjeans?

It’s a vast decision, with the power to affect every aspect of my life WouldIinadvertentlydestroyimportantthingsinmylifeasaconsequence?I think about transitioningincessantly,look at sites for wigs andmakeupand clothingasifIwere actuallyshoppingandnotsimplystockingthe larder of my imagination. If it weren’t for COVID-19 I would contrive some way of payingavisittoatransformationsalon,butthoseplacesareallclosednow I keep wanting to be forced to transition by some circumstance, maybe my therapisttellingmethatitiscrucialformysanity AnywayI’mstartinghere, bywritingitdown—somethingI’veneverdonebefore—andbysendingittoa veryfew people whomI trust andwho I think willunderstand. Myname is LucyMarieSante,onlyoneletteraddedtomydeadname

26February2021

Thatwaswrittenfromwithinawhirlwind.IamastonishedaneweverytimeIconsiderthe chronology. The firstFaceAppmanifestationoccurredFebruary16. Tendayslater I came outtomytherapist,Dr.G.,whodidn’tblink,butmerelysaidshethoughttransitioningmade senseandwasagoodidea Thefollowingevening,afterI’dwrittentheletter,Icameoutto mypartner,Mimi,whichwasthesinglemostdifficultthingofthemall,andthedayafterthat I came out to my son, Raphael The fortification of secrets I’d spent nearly sixty years buildingandreinforcinghadcrumbledtodustinalittleoveraweek.Theletteritselfwasso conclusivethatitwouldserveasthetemplatefortheformalpubliccoming-outpiecethatI’d write inOctober and see published inVanityFairthe following February By feeding the snapshotsofmylifeintothemawofthephoto-alteringsoftware,Imanagedtoforceopena door inmysubconscious,one festoonedwithpadlocksandwaxsealsandwarningsignsin nineteenlanguages.Thatwasnotareversibleaction.Openingitreleasedafloodofmatter —knowledge, speculation, dreams that had been confined so long it had fermented and become hallucinogenic. I never had to face the usual question confronting people who transitionearlierinlife:AmIreallytrans?Thatquestionhadbeendecidedformedecades earlier,asmuchasIfoughtagainstacknowledgingit

Thereactionwasimmediate:emails,phonecalls,texts.Everyonewasnice,althoughthere wasarange.Therewas“unexpectedbutnotsurprising”and“surprisedbutnotsurprised” and“shockingbut not”at one end,andat the other were a few people who reactedasif they’dbeenhitbyatrainwhiletheywerelookingtheotherway.Thosetendedmainlytobe guys who over the course ofmanyyears’friendshiphadcome to think ofme as a sort of mirrororalterego,soreevaluatingmemeanthavingtoreevaluatethemselves.Everybody onthe“notsurprised”endwasfemale,aswerethethreepersonswhowrotetosaytheyhad happytearsintheireyesastheyreadmyletter.Whensendingthelettertooneclosefriend of nearly fifty years, who is gay, I reminded him that he had once compared gender transition to “a kind of suicide” In his response he admitted he “took the condition as somehowathreattogaydom,butthatwaswhenIknewnothing,andImeannothing,about

trans Dragandcross-dressingweretreatedasextensionsofgay,andtheyarenotatallthe samething.”

I feltasthoughI neededtosendthe letter toatleastone transperson,andthere was none inmy circle,so I sent it to a trans womanonthe West Coast I knew at one or two removes.Herlifewastoobusytoallowhertofinishreadingtheletter,butafteracursory examinationofthefirstpageshewrote:“MyonlynotesofaristhatIwouldn’tmentionyour crotchinconnectionwitharealizationaboutyourgenderidentity,becauseanymentionof genitalia or crotches instantly brings upall sorts of bizarre paranoiddelusions that trans womenarejusttransitioningaspartofsomekindofsexualfetish.”Butthiswasmerelya privateletteraddressedtoasmallgroup,Ithoughtofwritingback,butdidn’t.Ichangedthe word to that Victorian euphemism, “belly” Another West Coast friend, a psychologist specializingintranschildrenandadolescents,wrote,“Iamawareofthecomplicationsofa cis personcommenting ona trans person’s appearance, and comments about beauty and whatitmeanstobefemininearelandmines,soI’mhopingthisisokaytosay...”Ihadno ideatherewerecomplicationstomerelytellingafriendtheylooknice.

Iwaspreparedforsomekindofpushback,softlyandjudiciouslyexpressed,ofcourse,but it never really came, thenor later. The closest thingI got was anunimpeachably sincere letterfromaveryseriousfriend:“Iam concernedaboutthesuddennessofthisinsight Andwhilethatdoesn’tinvalidateitstruth,asafriend,Iwouldaskthatbeforeyoumakeany irrevocablemedicaldecisionsyougivethisabitoftimetoseehowitfeels.”Iwonderedifhe thoughtthatonedayI’dhoponthesteamertoCasablancaandreappearsixmonthslateras the Louisiana Firecracker. But most responses were yay, go for it, you do you. The men oftenfeltitnecessarytocongratulatemeonmycourage,asifthatwereevenanoperative term.AsthemonthswentbyandIcameouttoconcentricringsoffriendsandacquaintances my correspondence grew mightily. I heard from people who had heard indirectly: former students, onetime colleagues, long-ago editors, people who’d had me read in their series once,peoplefromdeepinmypastwhopreservedacertain1973partyintheirmemoryasif it were a pear ineau-de-vie Newcategoriesofresponse were added Myfavoriteswere the“secretsharer”notes,fromcismenwhohadfeltatwinge,ormorethanatwinge,and hadhiddenitawayforreasonssimilartominebutweredeterminedtokeepondoingso,yet stillfeltalittlewistful.

SometimeintheearlyweeksofmytransitionIbeganhearingsnatchesofasonginmyhead, a songI hadwrittenthe words to Or rather,a prose poemI wrote in1978,whenI was twenty-four, that a couple of years later was set to music by Phil Kline and eventually recordedbythe Del-Byzanteens,abandthatalsoincludedJimJarmusch,PhilippeBordaz, andJamieNares,allfriendsofmine.Thepoemwascalled“EasyTouch,”althoughforsome reasonIchangedthetitleforthesongversionto“GirlsImagination.”IhadseenontheUK chartsalistingforaloversrockgirl-groupcoveroftheTemptations’“JustMyImagination,” whichwastitled“GirlsImagination.”Thegroupwascalled15-16-17,aftertheirages.Iwas charmedbythetitle’smissingapostrophe,whichmadeitinterestinglyambiguous:itcould representtheimaginationofoneormoregirls,orrefertothewaytheimaginationissetoff by girls, or indeed equate the propositions “girls” and “imagination” My friends’ song, a trancelike westernraga after the manner ofthe Kinks’“See My Friends,” appearedona twelve-inchsingleandtheonealbumbytheDel-Byzanteens,andonthesoundtrackofafilm byWimWenders,TheStateofThings

I rarely thought about it anymore When songs driftedintomyinternalairspacefornogoodreason Ihadn’theardthematthesupermarketorthemovies or on my iPod—I always wondered why they would choose that moment to climb into my head. In this casethewordscamebacktomeasiftheyhadbeen writtenbysomeoneelse,andIturnedthemoverasI mentallyreplayedthem.

There was a remarkable slow movement she did with her hands, circling halves of what wouldhavebeenher face,asiftryingtomold oneoutofectoplasm.Theruinedgirlylookshe wore was completely the effect of the thin creamplasticmaskthatsatover.Pullingaway,arobewouldleaveimprintson newlygraftedskin,sostrangetobesomeonelifelikebuttooearly.Firstmovies becamelongerandlonger,andthenmovieslovedherback

Itwasthebeginningofanewdreamwhichwasreallife,orthemanifestationof anoldoneatitscusp Sheimaginedtheytookherinawhitecartoaroomina clubandthetouchwasgiventoher.Theotherwomenlookedbackather,but theyweresistersunderthemink.Shethrewofftheredcapeandsang:

There’snousewalkinginjustashirt

Whenbaby’sgotonheranimalfeet, Andthere’snopointtoalotofbusiness

Whenwhatyoumeanisnobodyhome

Thentheypulledonthecordsattachedtoherlegsandshebecamebiggerand bigger.Thenbluishfingernailsonsoft,stickypianokeys.

Iwasstunned Thewholethingwasabouttransitioning!Howhadthatpassedmyinternal censor? At the time I thought I was weavinga vague reverie basedontwo movies, Eyes WithoutaFacebyGeorgesFranjuandTheBigHeatbyFritzLang;the“thincreamplastic mask”comesfromthefirstand“sistersunderthemink”fromthesecond.Bothfilmsfeature the disfigurement of the female protagonist. I’ve always been frankly in awe of my subconscious,whichpullsoffthedamnedestthingswhenleastexpected IfIwereina12stepprogramitwouldbemyhigherpower.HereithadsmuggledinawholescenarioIhad rarelymanagedtoexploreevenintheprivacyofmyownimagination,asterrifiedasIwasof theimplications. Ishiveredatthewords“sostrangetobesomeonelifelikebuttooearly,” whichperfectly describedthe state I foundmyself inthen, andsometimes still do. It was nothing less than a founding myth, a sort of robing of the bride, an alchemical transformationfrommaletofemale,sealedbytherecognitionandapprovalofotherwomen. Andisthatactuallyaclitorisinthelastsentence?

Mysubconsciouswasattunedtomybeingandmydesiresinawaythatmyconsciousmind couldn’tafford The sophisticationofmyrepressive mechanismcanbe gaugedbythe fact thatIwasabletowritethosewords,showthemtomyfriends,hearthemsettomusic,hear

themsunglive dozens oftimes andonrecordintwo formats, print themina chapbook I madeofmyearlypoetryin2009—andnotoncetumbletotheir realsubject,whichseems unmistakabletomenow. Forthatmatter,lookattherefrainoftheothersongIwrotefor theDel-Byzanteens,thetitletrackoftheiralbumLiestoLiveBy:“IfIonlyhaveonelife,let meliveitasalie.”NotethatithijacksaubiquitousClairolcommercialfromthe1970s:“IfI onlyhaveonelife,letmeliveitasablonde”Theconflictisspelledoutsoexplicitlyyou’d thinkIwouldhavenoticed.

WhoamI?is a question I’ve been trying to resolve for the better part of my life, even withoutreferencetomattersofgender Theputativeanswerisbothspecificandelusive I’m a writer before I’m anything else. I’m European and American, poised midway between thosepolesinbothattitudeandcitizenshipstatus I’maWalloon,prettymuch100percent, athoroughbredspecimenofoneoftheworld’smoreoverlookedethnicgroups,overlooked inpartbecausetheyseldomseemtostrayfromhome (Over thecourseoffiftyyearsI’ve metnomorethanthreeintheUnitedStates.)I’manonlychild,withfewsurvivingrelatives. I’ma father ofone. I’manex-boyfriendandanex-husbandtwice. I’ma retiredprofessor (verypart-timeatthat) I’mavisualartistinseasonswhenthevisual-artsmoonishighin the sky. I’m a homeowner. I’m a registered Democrat, but my political leanings range somewhatleftofthat—althougheverythingissuchamessnowthatInolongerbothertrying tospecifyexactlywhere.I’mnotamemberofanyclubororganization,exceptahundredmemberonlinechatgroupIjoinedatitsstartin2007.

I’m down to about five feet, ten inches; I’m into the shrinking years I try to keep my weight as near to 150 pounds as I can manage. I don’t know my blood type, which is shockingatmyage I’vehadsurgicalinterventionsonmyspine(sciatica)andmyleftknee, but everything in my body seems in working order, knock on wood. My only recurrent problemiskidneystones,whichI’vehadsinceIwasfifteenandwhichlieinwaittosurprise me at inopportune moments, such as publication day of a big book, with the promo tour startingthenextday.Ihavepatriciantoes,canrollmytongueandcockoneeyebrow;can’t whistle for shit,though I ambald I’mpartiallycolorblind I’mafraidofheights I love to walkandswim,buthavenevervoluntarilypursuedsports.Ismokedcigarettes(mostlyrollups,mostlyGauloisestobacco)forthirtyyears,andquitbecauseofasmallpersistentcough thatmydoctorlaughinglyassuredmewashayfever,whenIfinallyconsultedheraftertwo years of it. I nevertheless continue to consume nicotine ona daily basis, initially via gum (yuck) and then e-cigarettes that look enough like filter tips that waitresses on Parisian terracescomerunningwithlighters. I’vealsoconsumedcannabisdailyfor morethanfifty years I barelydrink I alternate periodsofdecentsleepandperiodsofinsomnia,whichI medicate. Ieatprettymucheverything,althoughtherewasnorefrigerator or fastfoodin myfirstsixyears,soIdon’tgoforconvenience.Idomyowncooking.

I’mold-schoolinagreatmanyways. Iidentifyasabohemian,andIshouldmaybehave put that at the top if it weren’t that there are vanishingly few actual bohemians walking aroundtoday,andbynowIambourgeoisdespitemybestefforts IneverforgetthatIcome from the working class; class has interfered with more than one of my intimate relationships Ihavenoreligiousor spiritualbeliefs,perhapsbecauseIwasbroughtupin strictandevenfanaticalCatholicobservance.I’maromantic.I’mbasicallyascofflaw,and have no patience with literal-mindedness. I have no academic degrees. I’m profoundly nostalgic for the analog era, but even more my nostalgia is for the time before Ronald ReaganandMargaretThatcher usheredinthepresentsociopathicmoralculture,devoted

to the destruction of community and the devaluation of human beings, which grew allpervasivewiththecomingofthedigitalera.I’murban,concrete,disabused.Irelyonhumor tokeepme sane. I love allkindsofmusic,butsometimesI like silence evenmore. (I am, afterall,awriter)

IwasbornonMay25,1954,inVerviers,Belgium,theonlychildofLucienMathieuAmélie SanteandDeniseLambertineAlberteMarieGhislaineNandrin Myfatherwastheonlyson ofolderparents,anheirtoalocaltraditionofworking-classself-education,alaborerwho hadsteppeduptoamanagerialroleatanironfoundry,aworkerwhofeltpulledinvarious aspirational directions—the theater above all—but had determined to settle down and provideforafamily,amatteraboutwhichhenursedreservationshekeptlockedinatriplewalledemotionalsafe Mymother wasthe onlydaughter oftenantfarmerswholosttheir leaseatthestartoftheworldwideDepressionandwereforcedtomovetothecityandtake factoryjobs Shewasanchoredbyherpiety,whichwasoverwhelmingandatthesametime verysimple,againstaseaoftorments.

Iwasbornanonlychild.Thatis,mymotherwaswarned,aftermysafebirth,nottotryit again She had suffered several miscarriages and, a year and a month before me, a stillbirth. Myparentseachhadone sibling—ofthe opposite sex,symmetrically—neither of whomhadchildren, so I hadno first cousins. I hadno cousins at all onmy father’s side, because my grandfather was the youngest and came to procreation much later than his brothers,so that myfather’sfirst cousinswere thirtyyearsolder; theydidn’t mingle. My mother’scousins,whoconstitutedmostofhersociallife,hadstayedinthecountry,andout there they produced children at calendar intervals. I had so many first cousins once removedIcouldn’tkeepthemstraightormanagetogetclosetoany.Myconceptoffamily was, besides my parents, primarily a matter of the older generation: my three surviving grandparents—allofthemdeadbeforeIturnednine—andmyrobust,good-humored,briskly intelligent,deeplykind,pie-bakingTanteFonsine,wholivedlongenoughthatIvisitedheron myEurailPasswhenIwastwenty,surelytheonlytimeIevervoluntarilyinstigatedafamily visit

Because of my mother’s parents and their vast families, my early childhood featured holiday meals and group outings and Sunday afternoon coffee-and-cakes that were populatedbyalargeandshiftingcastofcharacters,someofwhomIonlysightedonceor twice IvividlyremembermeetingmycousinMyriam,TanteFonsine’sgranddaughter,born inKinshasawhenitwasstillcalledLéopoldville,apparentlythefirstprettygirlIhadever seen Weplayedtogetherwithmyvastfamilyofstuffedanimals Hereyesflashedandher smilefilledtheroom. Imayonlyhavemetherthatonetime,althoughIregularlysneaked looksather photographfor years. Butallthe familyhubbub,the excitingwhirlofholiday activity, the time spent with my adoring grandmother, the door-to-door visits because nobody hada telephone—allofthat went away inFebruary 1959,whenI was four anda half

Europeanindustrywasthennearthebeginningofacrisisthatwouldspanthefollowing twoorthreedecades Firstcoalwasintrouble,thensteel,thenglass,paper,chemicals;the rangeofindustriesaffectedincludedthewooltradethathaddominatedmyhometownsince thestartoftheindustrialrevolution.Whenmyfather’splaceofemploymentwasshuttered hefacedthesamedilemmaasmostotheradultmalesofhistimeandplace,mostofwhom sawjusttwooptions:togoonthedole,possiblyformanyyears,ortorelocatetotheCongo, which for most of a century had been—scruples aside—a place where working-class Belgianscouldbecomemanagementandliveinvillas,withservants.Thatdidnotappealto my father at all, whether or not he could sense the imminent end of colonial rule, which finallyoccurredin1961,andhehadtoomuchpridetocollectunemployment

But his childhood friend Lucy Dosquet had married an American GI after the war and movedwithhimtohisnativeNewJersey Andthenin1953herbrotherPol,mydad’sbest friend, had followed with his wife; they were among the very last immigrants to be processed at Ellis Island. Pol got a job at the Summit, New Jersey, plant of the Swiss pharmaceuticalfirmCiba,areallygoodjob,heboasted,andclaimedhecouldgetmyfather onejustasgood.So,aftermanylongcolumnsoffiguresinmydad’stinyscriptonthebacks ofenvelopes,myparentspackeduptheirpossessionsandmovedmymother’sparentsinto ourhouse.Wesetoffinstyle:byairplane,quiteexpensiveinthosedays,elevenandahalf hoursfromBrusselstoNewYorkwitharefuelingstopinMontreal

Butthepromiseturnedouttobeachimera. Pol’sjobwasnottheexecutivepositionhe hadclaimed,butconsistedoffeedingandcleaningupaftertheexperimentallabanimals(for Easter thatyear Ireceivedaflockofbabychicks,whichwere thenwhiskedawayagain), andhe couldn’t get a place for my dad. The only work my father couldfindwas mowing lawnsatanothernearbyplantfor$137anhour TheDosquetsandmyparentsfought—the feudwastoendureforfortyyears,whilethetwocoupleslivedinadjacenttownsandsilently observed one another at the supermarket—and we moved out of their apartment. Every nightmyfathersweatedoverhiscalculations.

So in October we headed back to Belgium. We took a Belgian freighter bound for Rotterdam—the rock-bottomcheapest way to travel inthose days—andafter stowingour baggage decided to tour New York City, since we hadn’t seen it yet and might not have anotherchance.ItwasHalloween,aholidaythenunknowntoEuropeans.InNewYorkCity in 1959, it meant wild hordes of children in bedsheets and witches’ hats running unchaperonedthroughthestreets.Iwasagog;Ihadseenutopia.Ihadalsoseenthelurid signagethatspilledforthfromtheForty-secondStreetmoviehousesinthosepre-porndays, despitemymother—whosawsmuteverywhereshelooked—keepingmychininherhandand pointing it out toward the curb Times Square sleaze, too, then became an emblem of freedomforme,evenifIhadnoideawhatitwasabout.ThuswasbornthelegendofNew YorkCityinmymind. Longbefore I wouldhave beenable to articulate anyofit,the city awakened in me the very earliest notions I had of autonomy and independence and adventure.Forthefirsttime,thejaildoorwasbrieflyleftajar.

Back in Belgium my father managed to land a decent job, but evidently the tensions betweenhimandmymother’sparents,nowourtenants,becametoohardtobear—Ihave no memories at all from those ten months. By August we were back in the States, by October back inSummit. The patternofyo-yoingnever quite ceased. Althoughmyfather, whohadfewlivingties,wasperfectlycontenttostayintheUS,mymother never lostthe desperate wish to go back to Belgium In 1962 she and I went back because my grandmotherwasdying,andthefollowingyearbecausemygrandfatherwasindirestraits. Bothvisitsranfor months—mysecondandthirdgradeswere splitbetweenAmericanand Belgianschools—asmymothertriedandfailedtomakeacaseformovingbackpermanently. IendedupfeelingasifIhadimmigratedtothe UnitedStatesfour times. Finallyin1988, aftermyfatherretired,theypulledupstakesandcausedaprefabhousetobeerectedon landnexttomymother’scousinNelly,intheruralvillageofSaint-Hubert,wheremyfather hadnothingtolookatandnothingtodo TwoyearslatertheywerebackinNewJersey,ina

house a block away from where they’d lived before, where my father chiefly looked at footballandgolfonTV.

Whenmy father retired, my parents hadaskedfor my advice inchoosingamongthree options:stayinNewJersey,gobacktoBelgium,ormovetoFlorida IadvisedBelgium,since Ihadspentmorethantwenty-fiveyearslisteningtomymother’spining.Evensomymother, asshe later toldme,suspectedthat part ofmymotive wasto be ridofthem—she wasn’t wrong—so she punished me by throwing away all my belongings that remained in their house,andthoseweremostofthetangibleremnantsofmychildhoodandadolescence.That

typified the dynamic between my mother and me: the passive aggression, the bottled-up rage,theabilitytogetundereachother’sskin.Ithadn’talwaysbeenthatway,ofcourse.I wasthemiraclechild,andappropriatelycherished.

Lessthantwoweeksaftersendingoutthe“Lucy”letter,Iwroteasecondlettertothesame crowd.

It’sbeenahellofamonth Well,it’sbeenjustshyofamonthsincethefull loadofgender dysphoria,whichI’dsecuredinthedeepestsubcellarsofmy psyche since childhood, suddenly burst full-force uponme. It was profound, earthshaking,vivid Youmaynotthinkofmeasimpulsive,inpartbecauseI seldomshow muchofmyselfto others,but I amthat,andso I immediately went allthe way Comingout to allofyouwasmycrossingofthe Rubicon

Airing my secret was liberating, and also irreversible. I thrilled at the prospectofdanglingmyselfoverwhatmightbeanabyss.

And then I went farther. I bought wigs (four in total), breast forms, lingerie,clothing,andmakeup. I lost nearlytenpounds. I shavedoff all my bodyhair Imoisturizedreligiously Ipracticedfemalebodylanguage Itook voicelessonsonline. Ijoinedatleastsixtransgenderforumsorchatrooms, and earnestly contributed Nearly every day the mail would bring another shipmentofclothes—mostlycheappolyesterthingsbecauseIwasnavigating betweenmytastesandwhatwouldactuallylookgoodonmeatmygreatage, andIdidn’tknowwhatwouldtakeandwhatwouldn’t Thisallpeakedwhen, wearing my deliciously thick and wavy Brazilian human-hair wig and my ankle-lengthlong-sleevedblackvelvetdress,Imadeanappointmentwithan endocrinologist.

ButIwon’tkeepthatappointment.Ihadbeenstiflingmydoubts,insisting tomyselfthatI’dneverbeenascertainofanythingasofmydesiretobecome awoman.Butthatveryinsistencewasacluetothefragilityofmyimpulse.I went to bed last night with the doubts getting louder and more difficult to ignore, and when I woke up this morning the fever had broken. It’s over. Maybenotforalltimebutfornow I’vepackedawayallmygearandstowed it,perhapsappropriately,inthecloset.

Itwastoomuch,toofast,andfartooabsolute.Iwasn’tready,andImay neverbe Theprocessviolatedmyinnatesenseofthedialectic,orperhapsI justmeanmyfundamentallydualpersonality—notthatIbelieveinastrology, butIamafterallaGemini Mostimportantly,Icouldnotignoretheeffectthis washavingonMimi,whomIlovemorethanI’veeverlovedanyone.Shewas agoodsportandarealhelp,butmyprojecthadshiftedthingsbetweenus, andnotonlydidIfearlosingher,IfoundthatIcouldn’tsquareLucy’sdrive foreuphoriawiththedeepbondbetweenus,whichhassurvivedanynumber ofcrisesoverthepastfourteenyears

Andso,whatnow?I’mtoooldandtoobaldtobegender-fluid;alsogiven myageI’minstinctively—perhapswrongly—dualistic Ihavelittledoubtthat my impulse will reawaken, perhaps at intervals. I’m not throwing anything away.Imaycross-dressnowandthen,maybeevenaroundotherpeople.Lucy lives on inside me and always will Maybe someday I’ll even keep an

appointmentwithanendocrinologist Ireallydon’tknowwhatmypsychehas instoreforme.Butthat’sthewayI’vealwaysbeen.Forexample,Icouldn’t write—anything—ifIknewinadvancewhatwasactuallygoingtohappenon thepage Imovethroughlifeguidedmainlybychanceandabeliefinnegative capability.It’snotthesteadiestormostbankableprocedure,butIcan’thelp that

ThefirstmanifestationofdeepdoubtthispastmonthcamewhenIstarted makingalistofthegreatwomen—whomI’veknownoridolizedfromafaror afterdeath—whosecompanyIwasexcitedtojoin.Idonotdeservetobein thatnumber,Ithought,everytimeIaddedanametothelist.Afterall,Ihave benefited from male privilege for almost 67 years I have never been overlookedorshuntedasidebecauseofmygender.Myauthorityismale,as is my voice, literally and on the page And although I’m well aware that genderandsexaretwodifferentthings,Ican’thelpbutthinkthatI’venever faced breast or uterine cancer or vaginal infections or for that matter menopause I’m certainly not making an argument against transgender transitioning. I’ve readandheardliterally hundreds of oftendeeply moving personalaccountsbypeoplewhofoundtheirrealselvesbyevolvingfromone gender to another. But I’mnot certainI qualify. I’mtoo thorny andvarious andcontradictoryandweird,andalso,Ican’thelpbutthink:Idon’tdeserve it

SoI’mstickingwithLucfornow.It’sfarfromaperfectsolution,butit’s livable,perhapsespeciallyinthe lightofmyhavingcome outtoyoualland themanythingsI’velearnedinthecourseofthisfeverishmonth.Imaynotbe gender-fluidinthe youthsense,butI feelemotionallyexpanded. One ofthe things I was most looking forward to from my anticipated course of antiandrogensandestrogensupplementswashowmymindandheartwouldshift. Iwantedtheemotionalrangeofawoman Imayneverexperiencethat,but maybeIcanfindsomesemblanceofitwithinmydeepestself.Iwillbeindaily conversationwithLucy

12March2021

The note was hooey, or largely so; it was a product of fear and grief. No doubt I was perfectlysincereabouteverythingIwrotewhenIwroteit,butitssemi-intentionaltaskwas toassistinadesperateflailingattempttoholdontomyfourteen-yearrelationship.

In a larger sense, it was caused by my inability to square my gender identity with my attractiontowomen.Thathadbeenthebiggestproblemallalong.Itcontainedanelement ofwhatIwouldlearniscalled“internalizedtransphobia.”Ihadtriedsohardforsolongto be a heterosexual man that the need to behave like one took me over like a puppeteer wheneverIfoundmyselfinthepresenceofawomanIfoundattractive.Andthatincludeda wide range of women on whom I had no sexual designs, from close friends to passing professionalacquaintances.Ineededtobeaguywiththem,somybodywouldautomatically adjust: my jaw woulddrop, lengtheningmy face; my eyes wouldhoodover; my shoulders wouldwiden;Iwouldregulatemywalk IknewhowtodothosethingsbecauseIhadstudied movies.

ButIhadahardtimewiththerestofthecharacter Imodeledmyselfonmyfriendsas bestIcould,butIwasn’tprivytotheirpillowtalk.ItisonlynowthatIcanappreciatejust howbadIwasatbeingmale,sinceIneededtokidmyselftokeepgoing.Icravedphysical

intimacy,butthe stricturesofmyupbringingpreventedme fromhavingmuchidea howto obtainit or what to do whenI got there. I was not drivenby my dick. It was ready and waiting,butdidn’tappeartoknowjustwhatitsrolewouldbe,cloudedasthatwasbyissues ofgender andromance andequality Sexwasallyearningandmystery There were times and circumstances when I fell in love every three minutes. Mostly I failed to score—to connect,Ishouldsay—withanyofmyintended,oftenbecauseIgaveupwithouteventrying, socertainwasIofrejection.

AndyetparadoxicallyIfeltattunedtowomen,relaxedintheirpresence,unburdenedby theneedtoactmalepastacertainpoint.OnereasonmycousinMyriamloomedsolargein my imaginationfor so longwas because I hardly met any girls my age before my middle teens When I finally did it was a revelation With women I could talk and move and experience emotions without feeling like I needed to hold down an artillery position. By contrast,IexperiencedallmenascompetitorsinastruggleIhadn’tsignedupfor,thegoal of which I couldn’t fathom. Almost anything could count as a misstep; the rules were byzantineandchangedconstantly.Infractionswerealwayspunished,physicallyinchildhood, byhumiliationlateron Therewasalwaysahierarchicalcompetition,fromwhichIwanted toabsentmyselfentirely.WithwomenIcouldfeelmilesawayfromthewar.Theycertainly hadtheirownantagonisticsocialstructures,butIdidn’timmediatelyseethose Thewomen Istartedbeingfriendswithinmylateteenswerewelcoming,generous,funny,withacalm appreciationofabsurdityandahealthydisregardfortheprevailingmindset.Icouldimagine myselfasone ofthem—butthe fantasywouldshatter assoonasIrealizedthatthiscould neverhappen.

Iwouldfallshortofwomen’sexpectationsjustasIhadofmen’s,butthistimeitmattered more.Thereactionwouldnotbepunishmentbutdisappointment,whichwasworse.Iwould alwaysbe anawkwardpretender,andasI learnedabout feminismmore infractionswere added: I was born without a cervix, would never menstruate, could never bear children. Women’schildbearingcapacityconstitutedalargepercentageoftheirmercantilevalue,and hencewasaprimarytargetoftheiroppression Icouldnotsufferthewaywomensuffer,soI couldnotqualify.AndfurthermoreIwasattractedtowomen,romanticallyandsexually,and that—in the sociocultural context of those years—made me a man whether or not I saw myselfasone.

BythetimeIsentoutmyfirstletterthebroadercontexthadchangedsubstantially.More people were aware that sex andgender do not necessarily correspond—that gender is in realityaverywidespectrum.EvenbeforegettingtheirreactionsIhadlittledoubtthatthe intelligent and independent women I knew would accept me But I still desired women romantically,andIcouldnotpicturemyfeelingsbeingreciprocatedbyanyone.IfeltasifI werepermanentlyexilingmyselfbeyondlove.ThemoreIrealizedmythoroughgoingfailure to play a male role in life—I had never really been a man at all—the more I sometimes wishedmytransitionweregoingintheoppositedirection.IfIcouldbecomeaman,maybeI couldsavemyrelationship IwouldfitmoreeasilyintotheworldIlivedin,whichforbetter or worse was mostly made up of heterosexual couples. I could go on being who I’d pretendedtobeforsixty-sixyears,onlynowwithallconflictsandcontradictionspainlessly resolved.TheonlyproblemwasthatIhadopenedPandora’sbox.Ididn’twanttobeaman. ButIdidn’tsendthatletter.

ForthreemonthsIwasonfire Ilookedoutataworldgonetilt Iwasundergoingviolent revolution. Every particle of my beingwas opento question, was minutely reviewed, was

loudlydebated,wasdenouncedorredeemed Iwasinawindtunnel,blastedrelentlesslyby emotions, reflections, memories, sudden insights, minor epiphanies, things I didn’t think I knew,anglesI’dneverconsidered.Mybodywasaquiveringmassofflyinginsects,eachone flutteringtoitsownrhythm,settingoffripplesthatspreadacrossmyshoulders,downmy spine fromthe brainstem,zigzaggingthroughmyarmsandlegs. I wasturnedinside out, flayedandreskinned,dissolvedandrebuilt Iwasface-to-facewiththecosmos Thewords aweand dread, previously abstractions, were suddenly alive in me. I spent days literally quaking.IfeltlikeBernini’sSaintTeresa.“Thiscracksopentheworld,”Iwroteonanindex card.

I’veneverkeptadiaryorjournal,butduringthiswhirlwindIstartedtakingnotes,justby way of touching ground every now and then I went in for proclamations: “I have finally foundmysoul.”“I’malreadypastthepointofnoreturn.”“Asawriter,IcouldimaginebutI hadn’t really lived This is what was missing” “I’m so relievedI’m doing this” And then therewastheinevitablecounterpoint:“DoIdeservethis?”BecauseIhadbeenbroughtup toregardallinstancesofgoodfortune asunmerited,butalsobecause I wasproposingto jointhe ranksofwomen,andI didn’t knowthat I couldjustifythe presumption I worried aboutintegratingthemanystrandsofmypersonalityunderthisnewheading.Iimmediately startedworryingaboutmyname,whichwas,inasense,myshopsign WouldIberiskingmy publicidentityasawriterbychangingit?(Thisseemstrivialnow,buttheworryconsumed meformonths.)

I started compiling lists: exercises, clothing and shoe sizes, clubs and organizations, premonitory clues scattered willy-nilly across the landscape of my life. I searched back acrossthedecadesandnoteddowneveryculturalitemwithtransgender implicationsthat hadcrossedmypath.JohnO’Hara’s“TheGeneral,”Faulkner’s“GoldenLand,”BorisVian’s Ellesserendentpascompte,afewepisodesinJimCarroll’sBasketballDiaries,asubplotin Pimpby Iceberg Slim. Orlando, by Virginia Woolf. Philippe d’Orléans and the Chevalier d’Éon;BambiandCoccinelle.AndréBretonallegedlysaying:“IwishthatIcouldchangemy sexthe wayI change myshirt”(rather hardtobelieve inviewofhissexualbehavior and beliefs).TheappearanceofamoviecalledIWantWhatIWant...toBeaWomanatthe Trans-Lux86thStreetmaybeaweekafterI’dseen2001:ASpaceOdysseythere;Ibelieve the tagline was“Aplainboybecomesabeautifulwoman.”(No,I didnotsee the picture. Yes,Iknowthe datesdon’tquite work,butthat’showIremember it; Imaybe conflating twomovies Inoticedthetheater’sname,familiarforever,asIwasjustnowtypingitout)

MyspottingabookcalledMissHigh-Heelsatthe MarlboroBooksfranchise acrossthe street from that theater John Rechy’s City of Night; Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. AdsinTheVillageVoicefor MichaelSalemBoutique andLee’sMardiGrasand theGildedGrape;accountsinthatpaperoftheStreetTransvestiteActionRevolutionaries (STAR)—likesciencefictiontomeatthetime.AnaccountintheNewarkEveningNewsofa runawayhusbandwhoturnedupintheticketboothofaporntheaterinFlorida,wearinga pink shift and ribbons in her hair The nowadays unreadable Algonquin wit Alexander Woollcott,whoinhisyouth“lovedtodressupandpasshimselfoffasagirl,”andsignedhis letters “Alecia” Yearbooks fromthe 1920s and’30s at my all-boys highschool, whenthe femalepartsintheatricalproductionswereallplayedbyboysindrag.Wasitpossiblethat themodelonthesleeveofRoxyMusic’sForYourPleasurewasatranssexual?(Yes,Amanda Lear)Whenisaboynotaboy?(Whenheturnsintoastore)

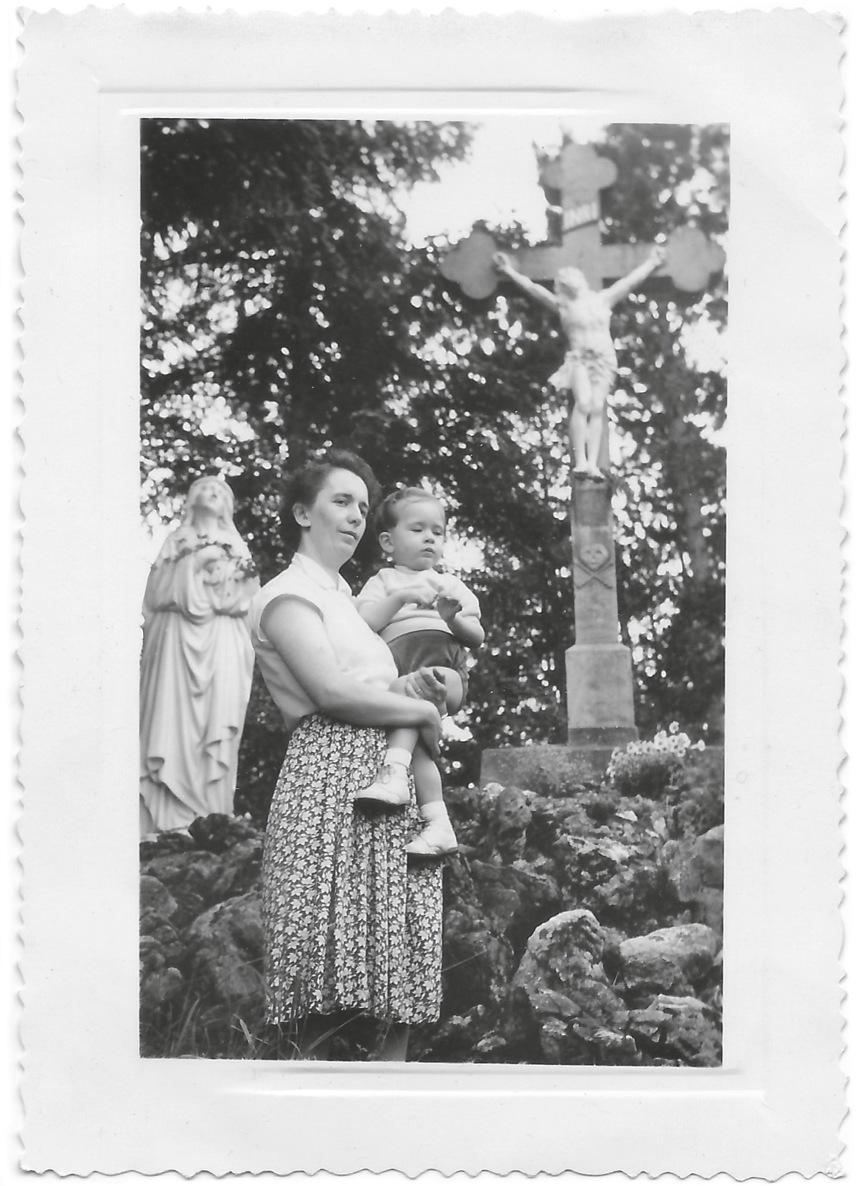

Iwasthebabywholived Idon’tknowmuchaboutmymother’sgynecologicalwoes,really Such things were not discussed in my presence. But as soon as I was old enough to understandthe adult worlda bit—aroundage eight,maybe—I became fascinatedwithmy parents’ secrets I knew they had them, but I could not figure out what they were, so I combedthroughtheirspokenwordsandtheirdresserdrawers.Parsingtheirtabletalk,at somepointIcaughtpassingreferencetowhatseemedlikemultipleinstancesofwhatIlater learnedweremiscarriages.MyparentsmarriedinFebruary1950.Theyweretwenty-eight andtwenty-six,lateinlifefortheirdemographic,butthatwastheeffectofthewarandits impoverishedaftermath. Theywouldhavestartedtryingtoprocreateimmediately,butthe firsttimemymothercarriedtofulltermwouldnotbeuntilthreeyearslater.Thecertificate reads:“Theyearnineteenhundredfifty-three,thetwenty-fifthofApril,alifelesschildofthe female sex was presented to us, taken from the womb of her mother.” Her name, not indicated on the form, was Marie-Luce My parents leased a cemetery plot, with no headstone,fortenyears.WhenIwasnotquitenineherboneswereremovedtotheossuary.

The death certificate is the only proof I have that she existed at all, but she was nonethelessalivingpresencethroughoutmychildhood Mymothercouldnotletgoofher It mayhavebeenthenthatshebegantakingnervepillsthatcameinametaltube;shewason assortedmooddrugsfortherestofherlife Therewerefrequentreferencesinhertalktola petite,sometimeswistfullyandsometimesmaybeasifshewereinthenextroom.Atother timessheseemedtothinkthatIwasher.Sheoftencalledmebyfemininediminutives:ma fifille, machérie, machoute(because chouis masculine she had to confect a feminine form).Bluewasforgirlsthereandthen,largelybecauseoftheVirginMary,butshedressed meinblueanyway,ostensiblybecauseofherdevotiontotheVirgin Itoofeltthepresence ofMarie-Luce,whosenamesI’dinheritedininvertedorder oneyear andonemonthlater, buttheformthatpresencetookshiftedaround.Sometimesshewasaphantom,sometimes shewasmyimaginaryplaymateandbedfellow,andsometimesshewasme.

Myparents’fortuneswentupanddown,upanddown.TheywereridinghighwhenIwas born, but then came a layoff or maybe a plant closure and they resigned themselves to runningaBatashoefranchiseinasteel-milltown.Whenwe’dcomehomefromwalksinthe stroller my blanket would be speckled with soot A year later things were on again, and that’s when they bought a brand-new semidetached on a corner lot. It was a new development ina village where some of my mother’s people hadbeenlivingforever, now reinventing itself as a postwar suburb For a year we even had a car, the first in the neighborhood,aMorrisMinor.Butmodernamenitieswerefew.Welackedcentralheating, hotrunningwater,arefrigerator,atelephone—andsodideveryoneelse Thewalkdownto the mezzanine toilet on a winter night was an arctic adventure, so the bedrooms were supplied with chamber pots. On visits after we’d moved to the US, when I was seven or eight,I’dcomehomefromschoolforlunchandmymotherwouldhandmeasatchel,alist, andsomemoney,andsendmeouttofetchthemakings.

I was cosseted I always had the best of everything, even when the family purse was slender.Ifmyparentscouldn’taffordsomething,mymaternalgrandmotherwouldfigureout away ShegavemeacoupledozenSteiffanimals,knittedmesweatersandscarves,knitted scarves for my Steiff animals. I have some notebooks my grandmother kept inher youth. Two of them, from her teens, are theological summations, and they are rigorous in their organization and penmanship, with cascades of indented curved brackets, like legal writ. Another, from during the first war (as it was always called), when she was in her early twenties,isacollectionofpopularsonglyrics,manyofthemalludingtoEngland;maybethis was her way of resisting the Germans. She shocked her family by naming her children DeniseandRené—Parisianmovie-starnamesatthetime—andshechangedherownname, fromtheantiquatedHonorinetothemoremodernAnne-Marie.Clearlyshecouldenvisiona worldbeyondthehardscrabbleArdennesfarmlandshecamefrom.Shewasimpatientwith mymother,perhapsevencruel,givingher a lifelonginferioritycomplex,butshe dotedon me.IimagineItakeafterher.

Her husband scared me After his wife’s death he would sit and smoke his pipe, not turningonlights whenit got dark, never readingor listeningto the radio. Sometimes his brothers would come over and they would all sit in the dark, not talking. They were old farmers,withaconceptoftheworldthatdidnotrangefarbeyondwheretheysat,although onourtripsbacktheyregularlycalleduponmetospeakEnglishforthebenefitoftheroom (I can’t imagine what kind of gibberish I might have emitted) They all terrified me, especially Achille, whose hawk nose was bent a quarter to the left. They represented somethinglikeanalienconsciousness,utterlyunfathomabletome.Mymothertoldmeflatly that her father was a coward. In May 1940, when they were fleeing Verviers on foot in

advance of the Germans, intermittently being strafed by Stukas, my grandfather would alwaysdiveintotheditchwithoutfirstassuringthesafetyofhiswifeandchildren. Onthe other hand I have a cabinet-card photo of him, circa 1912, from when he was briefly a streetcarconductorinLiège;hewearshisuniformasifhewereamajorgeneral

Once inthe USAfor good,or semi-good,I seldomgave myBelgianrelativesa thought. Loindesyeux,loinducoeur,theexpressiongoes:farfromtheeyes,farfromtheheart But thenIwastryingtobridgetwoculturesandtwolanguagestwiceaday.Atfirsttherewould be a buffer zone of about anhour betweenlanguages, whenI wouldn’t be able to speak eitherofthem.Forayearortwomymothergavemeafter-schoolFrenchlessonssothatI wouldn’t lose my grasp, for which I am forever grateful. (She was a bigot. Everything Belgian—everythingWalloon,more tothe point—wasthe world’sgreatest,andthe United Stateswasaflashy,immoral,backwardculture.)Ibeganfirstgradewithoutknowingaword ofEnglish;didn’tknowhowtoasktogotothebathroomandsoon ButIwassquarelyinthe magiclanguagewindow,andpickeditupfast.Theinstructionwasvivid—almosteveryword ofbasicEnglishisevennowaccompaniedinmymindbyitshistory: thesign,label,decal, wrapper,billboard,truckbody,junkmail,book,ornewspaperwhereIfirstencounteredit I wellremembermyfinaltriumph,whenIleapedoverthelasthurdle:thedayinfifthgrade whenIfinallymanagedtopronounce“th,”asin“three”

I was pretty much the only immigrant kid around. I remember a Hungarian family, refugeesfromthe 1956 uprising,whose sonLaszlo was as palpably foreignas I was—we bothearnedschoolyardjinglesconcerningthisfact—buttheydidn’tstickaround Mostofa decadeelapsedbeforeImetanotherimmigrantkid,aCuban.Theearly1960swas,inpoint of fact, the historical low for immigration to the United States; the postwar traffic from Europehadslowedandracistrestrictionsstillbarredmuchoftherestoftheworld.Which istosaythatIwasacuriosity,tobecautiouslypokedat.Mypracticaleducationproceeded infitsandstarts. IwasalwaysfilledwithquestionsIcouldn’taskanyone: Whatdoesthat slang word mean? Why is everybody wearing those things all of a sudden? What does anybodydoafterschool?Whatisthegoalofthatgameyou’replaying?Whydideverybody laughwhenthatboysaidthatunfunnysentence?IfI’deveraskedmyschoolmatesIwould havebeenmockedandscorned Maybethathappenedonceor twice,or maybeIwasjust anticipating.

Icertainlycouldn’taskmyparents.TheyknewlessthanIdid.Mymotherstartedtolearn someEnglishandabitofthelocalmoresafewyearslaterwhenshewentbacktowork,as alunchladyatthelocalhighschool,butsheremainedbaffledbymuchofAmericanlifeand cultureuntiltheend Myfatherwaslesstimidandmuchmoreofacosmopolite,buthehad foundthejobhewouldhold,withafewpromotionsalongtheway,forthelasttwenty-seven yearsofhisworkinglife—ataplantthatmadefluorocarboncoatingsknowninthetradeas Teflon—andthroughoutmychildhoodandadolescencethatentailedrotatingshifts.Wedidn’t alwayscoincidewhenheworkedeveningsornights.Ididn’ttrustgrown-upsatall,whether teachersorlibrariansorshopkeepersorkindlyretiredneighborswhogavemehomemade magnets andobsolete encyclopedias. I hada handful of playmates inthe neighborhood, a few schoolmates who were nice to me, but none of those friendships ran very deep FundamentallyIwasalone.

I guessthatabidingalonenessiswhatallowedme toconnectsostronglytothe veryfirst trans novel I read during my transition: IWantWhatIWant, by Geoff Brown It was publishedin1966andmayhavebeenthefirstself-consciouslyliteraryefforttorenderthe

transgenderexperience ItwasalateentryamongtheBritish“kitchen-sink”realistnovels ofthetime,withauthorslikeNellDunn,JohnBraine,AlanSillitoe.Itsauthorwasaniceman wholivedhiswhole life inthe house he wasbornin,wasmarriedtothe same womanfor decades,wrotetwonovels(theotherisfromtheperspectiveofaschizophrenic),andthen gave up writing altogether. Whatever his inner life may have been like—his widow’s commentwasthathewantedtobeanybodybutGeoffBrown—hecertainlygotalltheway inside the experience of transsexuality, renderingshades andnuances he couldnot easily haveresearched,atleastnotatthetime.

ThebooktellsthestoryofRoy,whohasknownall herlifesheisWendy.ButshelivesinHull,Yorkshire, withher father andstepmother, who runa fish-andchipsshop,andnooneincludingherhasanynotionof transgender anything She just knows she is not a homosexualor across-dresser; sheisawoman. She stealssomeclothesandgetscaught.Herfatherbeats her,andsheissenttothementalhospitalbutchecks herselfout.Backathome,liferemainstroubled,with further clothes-stealing incidents and a continuing cycle of affection alternating with brutality. Finally, when she turns twenty-one and comes into a small bequest from her dead mother, she moves to a boardinghouse, and then another in a different neighborhood, transforming herself into Wendy, buyingclothesbymail.Shegraduallybuildsalifefor herself,andhergenderchangeseemstobeallowing hertotransitsocialclassesaswell.I’llspoiltheplot foryou:shekillsherselfattheend.Thereadercould have seen this coming, perhaps before opening the book.

But that might be describedas a history tax The authorisasbeholdentotheconventionsoftheageas hisheroine. The tragichermaphrodite reallyshouldhave beena stocknineteenth-century melodramacharacter,andalmostseemsasifithadbeen Anyway,theinnerHaysCodeso manyofuscarryaroundsemiconsciouslywouldnaturallysentencesuchacreaturetodeath, thepriceofdevianceinmostplacesandtimes Wendyhashadminimalschoolingandknows onlywhat she feels. She seemsalmost preindustrial,barelyaffectedbymovie imageryor anyotherkindofobvioustemplateforherimagination.Everythingshedesiresisbasedon womenshehasseenonthestreet,orsometimeshasmadeupherself.

Ayounggirlwalkedonthe footpath. Her hair wasblack. The breeze foldedher summer dressasshe walked She walkedalongpretendingto be unconsciousof her happiness. There was something intelligent in her movements. Perhaps she wasdownonthelongvacationfromOxford Perhapsshewasaclevermodel,come homeforarestfromLondon.Thefirstwaspossible.Thesecondseemedunlikely. Shewasnottallenough.Iwastallenough.

She is undereducated, but her inner monologues are often lyrical arguments of great complexity. Not very far into its pages I began copying out entire paragraphs in my

notebook Iwasstruckbythispassage,forexample:

If I could get onto the other side, I would live happily with inhibitions in me becausetheywouldbetheinhibitionsofawoman. Iwantedtobeoneofthem. I did not want to stand apart and see them as fools I wanted to be foolish with them.Iwantedtosuffereverythingthattheysuffered.Iwantedtobelimitedand mistaken Iwantedtobepartoftheworldthatwaswronginsteadofbeingshutin with my meaningless mathematics of thoughts that were right. A woman’s body was a better place to live inthana man’s brain. Allrealstuff was womanstuff. Motheranddaughterandmotheranddaughterwereonefleshgoingbackintime tothefemalestomachcreaturesthatneedednomale.Themalewasoutside.He mightmastertheworld,buthewasnotpartoftheworld

Wendy is unsophisticated but a complicated creature, with great depths of feeling in addition to an array of blind spots The preceding passage traces a delicate tension of perspectives:Wendy’swill,herirony,theauthor’sirony.Itmusthavebeentosomedegree because the account isso exactinglyspecificabout itsheroine’sinner life,not to mention her timeandplace,thatitspoketomesodirectly For allour obviousdifferences,Icould get into Wendy’s skin. I knew her in acute ways—her aloneness, her stubbornness, her exaltedmetaphysics, her sense of destiny At times the book seemedto know what I was goingthroughat the exact moment of reading. The thoroughness of its investigationwas breathtaking, the chastenedlanguage tunedto the exact emotional pitch. “I do not know whyIamasIam,butIknowthatmydesiretobeawomanissopowerfulthatIcannever expressitinwords.Itseemstocomefromoutsideofme,forithasmuchmorestrengththan Ihave”

IdidnothaveastronggenderidentitywhenIwassmall.Idrewpicturesandplayedwithmy largefamilyofstuffedanimals,towhomIassignedfamilyroles.Ireadtheadventuresofthe boy reporter Tintin, but I also readthe purely quotidianadventures ofMartine, a sort of Everygirl,whichmusthavebeensentbyarelative. Ihaveadistinctbutvaguememory(I couldn’t tell youthe year or eventhe country) of being somewhere withmy parents and pickingsomethingup—amagazine?arecord?—withagirl’sfaceonit,andthemlaughingat me Icertainlytookitasawarningtoavoiddisplayingpicturesofgirls—tonot,say,tackup picturesofFrançoiseHardyallovermyroom,aftermypaternalauntanduncle,small-town newsagents, began sending me the French teen magazine Salutlescopains. But I didn’t really know what the laughter meant Were they laughingbecause it seemedsuspiciously feminine that I wouldbe interestedina girlona magazine? Or wasit because itseemed precociouslyheterosexual?Thatsecondonedidnotoccurtomeatthetime

But I was never pushed in any conspicuously masculine direction, either. Despite his interest in sports (he was an avid basketball player in his youth, although five feet, two inches), my father didn’t seem to care that I felt no pull in that direction, and we never engagedinthetraditionalmalebondingexperiences,noteventossingaballbackandforth. Healsonevertaughtmeanyofhisskills:carpentry,plumbing,painting,paperhanging,even shoerepair(hehadatonepointapprenticedwithacobbler),althoughthathadmoretodo withclassthanwithgender.Thewayhesawit,Iwouldgrowuptobeanimportantperson whowouldhavelaborerstodothosethingsfor him. Hewaseager thatIextricatemyself from the working class and earn my pay from the comfort of a desk chair. He had no

objections to my being a writer—he was a frustrated writer himself, who in 1948 had publishedanO.Henry–likesketchinanewspaperunderthebyline“LucSante.”

Mymothernevertaughtmeherskills,either,notevenallowinganyoneintothekitchen whenshewascooking Butthenhermotherandheraunthadbeenlegendarycooksandshe was forever made to feel like the graceless idiot daughter; her repertoire of dishes was limitedtorecipeswrittendownbyhermother Naturallyshewouldnothavewantedtobe observedinher dailyrace againstfailure. I’mcertainmymother wantedme tobe a girl. She struggled with the reality of her stillborn daughter, conflated the two of us, maybe wantedtoeffectsomekindofmagicaltransference.[*] Shefearedmen,probablywithgood reason, and would in any case have preferred someone like herself, as much as her girl cousinswerelikeher,someoneshecouldtreatwiththetendernessherownmotherdenied her.Duringourtimetogether,whenmyfatherwasatworkorwhenwewereinEuropeand hestayedbehindworking,Imightjustaswellhavebeenherdaughter Iwasquietandtimid andseriousandcute,withbigdarkbrowneyes,woreakerchiefovermyheadwhenitwas windyandalittlewoolbonnetthattiedundermychinwhenitwascold,woreaPeterPan–collar dickey with my duckling-yellow sweater, and displayed my little knees year-round betweenshortpantsandsocks.

Ican’tsaywithanykindofcertaintyjustwhentheideathatImightor shouldbeagirl firsttookhold,butprobablyitwasaroundagenineorten.Iwasanimaginativeandfearful childwhosawomenseverywhere. IfIcameacrossapulpillustrationofanotenailedtoa treesaying“Youwilldietonight,”IwascertainIwoulddiethatnight Mymother’sreligion assistedthiscompulsionpowerfully,ofcourse. Anywordor actcouldsendonetohell. My mother hadputaholy-water fontjustinsidethedoorwayofmyroom,andIknewthatifI didn’tcrossmyselfwiththewatereverytimeIcrossedthethresholdIwoulddiethatnight.I wasconstantlypleadingwithJesusnottokillme yet,justasI mightaskhimfor a record player,oravisittoanamusementpark,ortosparethelivesofmyparentsiftheywerelate gettingbackfromthe store andtherefore surelyina car crash,or topreventmymother fromkillingmewhenIgotabadreportcard Atsomepointtherecamethequestionofthe abilityofJesustoturnmeintoagirlovernight,inmysleep.Idon’trememberwhetherJesus proposedthisorifIrequesteditofhim,butthereitwas,anditwouldn’tleavemealone I trembled,frombothdesperatewishfulnessandnakedfear.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

raw recruits, with the remnants of the men who had made the disastrous autumn campaign. Forty miles off lay Frederick of Prussia, with forty thousand men, besieging Olmutz. If he succeeded in capturing this strongly fortified place the road to Vienna would be open. But it was an undertaking difficult for even the stupendous military genius of Frederick. The town was naturally protected by the numerous branches of the Morawa River, and these sluices, generally kept dammed, could easily be flooded and oppose difficult obstacles to overcome. In addition to this, all of the Prussian supplies—food, ammunition, and money—had to be transported by wagons from Neisse, a hundred and twenty miles off, while the last eighty miles from Troppau were extremely dangerous, and required a protecting force of more than ten thousand men for each of the monthly convoys of from three to four thousand four-horse wagons.

Marshal Daun was proverbial for his slowness and caution, and it was often a source of congratulation to Gavin and St. Arnaud that they were under General Loudon, who was in a state of perpetual activity. There were continual scouting parties almost to the gates of Olmutz, and constant communication with the town and garrison. Both were determined to resist, and being well provided with food and ammunition, there was no thought of surrender Frederick, who is thought to have shown less ability in sieges than in battles, had allowed his engineers to begin their first parallel too far away from the lines, and the first bombardment, terrific in point of noise, and costing vast amounts of the gunpowder so precious to the Prussians, did not the smallest harm.

The month of May opened, and although Frederick pursued the siege with vigour, Marshal Daun still lay among the hills and mountains, moving a little off from Leutomischl, but still keeping about forty miles from Olmutz. He knew, however, that all was going well for the Austrians and ill for the Prussians at Olmutz. The Pandours, light-armed Hungarian infantry, that in marching could equal the cavalry, infested the neighbourhood of the town and fortress in small parties, and even singly, while Loudon’s corps, chiefly light cavalry, but with four regiments of grenadiers, made it

dangerous to all small bodies of Prussian troops who ventured away from their lines. Loudon’s comprehensive and piercing eye did not fail to see the qualifications of all his officers, even the subalterns, whom he knew through the reports he exacted of their superiors, and he soon came to realize that in Captain St. Arnaud he had a man after his own heart. And riding one day with the colonel of St. Arnaud’s regiment, the general said:

“Is not that young Sublieutenant Hamilton, who is always with Captain St. Arnaud, a capable officer?”

“Very, sir; his activity and enterprise, as well as Captain St. Arnaud’s, were shown by their escape from Glatz. As you probably know, Hamilton is of good English and Scotch blood, but, owing to some family troubles, his youth was spent in poverty and obscurity, and he served some time in the French army as a private soldier. The Empress Queen herself gave him his commission, and the young man seems burning to distinguish himself.”

General Loudon, himself a Scotchman, was not less interested in Gavin from knowing his nationality.

May passed into June, and June waned; still Marshal Daun gave no sign of interrupting the siege of Olmutz. He had merely taken up a position a few miles nearer, where he patiently waited for the hour of action. The officers and men of Loudon’s corps were envied by the rest of the army, as they alone were actively employed.

One night, after a week of very active scouting, St. Arnaud and Gavin were sitting in their tent, when a message from General Loudon came for St. Arnaud. He at once left, and it was an hour before he returned. When he entered, his gleaming eyes and smiling face showed that he had something pleasant to tell.

“Good news! great news!” he said, sitting down on the table, where Gavin was studying a large map of the country spread out before him. “We move to-morrow. A wagon train of more than three thousand four-horse wagons, loaded with money, food, clothing, and ammunition—they say our old acquaintance, the King of Prussia, is

devilish short of ammunition—has started from Neisse. If it reaches Olmutz, it will prolong the siege certainly—Frederick thinks it will give him the victory. But if we can stop it, we can save Olmutz without a pitched battle, and thereby ruin the Prussian campaign in the beginning. It has an escort of seven thousand men, and four thousand men will be sent to meet it; that means that the Prussians must lose a whole army corps, as well as their three or four thousand wagons and twelve thousand horses.”

“And we will stop them here,” cried Gavin, excitably, pointing on the map to the pass of Domstadtl. “You know, that pass, hemmed in by mountains, and narrow and devious, a thousand men could stop ten thousand there.”

“We will make a feint at Guntersdorf, a few miles before they get to Domstadtl; but you are right; the Prussians must open that gate and shut it after them if they want to save their convoy; and the opening and shutting will be hard enough, I promise you. We move the day after to-morrow, so go to bed. You will have work to do tomorrow.”

Work, indeed, there was to do for every officer and man in Marshal Daun’s army; and the morning after they were on the march. It was a bright and beautiful June morning, and it seemed a holiday march to the fifty thousand Austrians. Marshal Daun was noted for keeping his men well fed, and the friendly disposition of the people in the province made this an easy thing to do. The Austrian armies were ever the most picturesque in Europe, owing to the splendour and variety of their uniforms and the different races represented. Rested and refreshed after the disastrous campaign of the autumn, on this day they hailed with joy the prospect of meeting their ancient enemy. With fresh twigs in their helmets, with their knapsacks well filled, the great masses of cavalry, infantry, and artillery stepped out in beautiful order, threading their way along the breezy uplands and through the green heart of the wooded hills down to the charming valleys below.

St. Arnaud and Gavin were with the vanguard. A part of their duty was to throw a reinforcement of eleven hundred men into Olmutz, and it was Marshal Daun’s design to make Frederick think that a pitched battle in front of Olmutz was designed.

All through the dewy morning they travelled briskly, and after a short rest at noon they again took up the line of march in the golden afternoon. About six o’clock they reached a little white village in the plain, which was to be the halting place for the night of Loudon’s corps.

It was an exquisite June evening, cool for the season, with a young moon trembling in the east, and a sky all green and rose and opal in the west. Myriads of flashing stars glittered in the deep blue heavens, and the passing from the golden light of day to the silver radiance of the night was ineffably lovely.

From the vast green plain and the dusky hills and valleys rose the camp-fires of fifty thousand men. Just at sunset the band of St. Arnaud’s regiment, marching out to a green field beyond the village, began to play the national hymn. Other bands, from the near-by plain and the far-away recesses of the hills and valleys, joined in, and the music, deliciously softened by the distances, floated upward, till it was lost in the evening sky.

Gavin and St. Arnaud, walking together along a little hawthornbordered lane, listened with a feeling of delight so sharp as to be almost pain. The magic beauty of the scene, the hour, and the sweet music were overpowering. St. Arnaud’s words, after a long silence, when the last echo of the music had died among the hills, were:

“And this delicious prelude is the beginning of the great concert of war, cannon, and musketry, the groans and cries of the wounded, the wild weeping of widows and orphans, the tap of the drum in the funeral march.”

“And shouts of victory, and the knowledge of having done one’s duty, and the sweet acclaims of all we love when we return,” answered Gavin.

“I am older than you, and have seen more of war,” was St. Arnaud’s reply.

Day broke next morning upon a fair and cloudless world. It continued cool for the season, and the sun was not too warm to drive away the freshness of the air. By sunrise they were on the march again, and by noon Frederick, at his great camp of Prossnitz, saw through his glass masses of Austrians appearing through the trees and taking post on the opposite heights, and turning to his aide, said:

“Those Austrians are learning to march, though!”

In the Prussian army it was thought that battle was meant, and troops were hurried forward to that side of the fortress. But Loudon, stealthily creeping up on the other side, engaging such force as was left—eleven hundred grenadiers—without firing a shot or losing a man double-quicked it into the fortress. By the afternoon the Austrians had melted out of sight, and the garrison was stronger by eleven hundred men.

In this demonstration on the other side of the fortress St. Arnaud’s command had taken part. It was well understood that the action was a mere feint to cover the grenadiers who were running into the fortress, and St. Arnaud had privately warned Gavin against leading his troop too far, knowing that a single troop may bring on a general engagement. Gavin promised faithfully to remember this, and did, until finding himself, for the first time, close to a small body of Prussian infantry, in an old apple orchard, he suddenly dashed forward, waving his sword frantically, and yelling for his men to come on. The Prussians were not to be frightened by that sort of thing, and coolly waiting, partly protected by the trees and undergrowth, received the Austrians with a volley. One trooper rolled out of his saddle; the sight maddened the rest, and the first thing St. Arnaud knew he was in the midst of a sharp skirmish. The Prussians stood their ground, and as the Austrians had no infantry at hand, it took some time to dislodge them. Nor was it done without loss on the Austrian side. At last, however, the Prussians began a backward movement, in perfect order, and without losing a man. St. Arnaud,

glad to have them go on almost any terms, was amazed and infuriated to hear Gavin shouting to his men, and to see them following him at a gallop, under the trees, toward the wall at the farther end of the orchard, where the Prussians could ask no better place to make a stand. In vain the bugler rent the air with the piercing notes of the recall. Gavin only turned, and waving his sword at St. Arnaud plunged ahead. St. Arnaud, wild with anxiety, sent an orderly after him with peremptory orders to return; but Gavin kept on. St. Arnaud, sending a number of his men around in an effort to flank the Prussians, was presently relieved to see some of Gavin’s troopers straggling back. And last of all he saw Gavin, with a man lying across the rump of his horse, making his way out of the orchard. At that moment General Loudon, with a single staff-officer, rode up.

“Captain St. Arnaud,” said he in a voice of suppressed anger, “I am amazed at what I see. If this firing is heard, it may bring the Prussians on our backs in such force that not only our grenadiers will not get into the fortress, but they may be captured. My orders were, distinctly, there should be no fighting, if possible. Here I see a part of your command following the enemy into a position where a hundred of them could hold their own against a thousand cavalry.”

St. Arnaud was in a rage with Gavin, and thinking it would be the best thing in the world for Gavin to get then and there the rebuke he deserved, replied firmly:

“It is not I, sir, who has disobeyed your orders. Lieutenant Hamilton’s impetuosity led him into this, and I have been trying to recall him for the last half hour. Here is Lieutenant Hamilton now.”

Gavin rode up. An overhanging bough had grazed his nose and made it bleed, and at the same time had given him a black and swollen eye. And another bough had caught in his coat and torn it nearly off his body. But these minor particulars were lost in the vast and expansive grin which wreathed his face. The thought that illumined his mind and emblazoned his countenance was this:

“The general is here. He must have seen what I did. What good fortune! My promotion is sure.”

But what General Loudon said was this:

“Lieutenant Hamilton, your conduct to-day is as much deserving of a court martial as any I ever saw on the field. You have not only unnecessarily endangered the lives of your men—a crime on the part of an officer—but you have come near endangering the whole success of our movement. Your place after this will be with neither the vanguard nor the rear-guard, but with the main body, where you can do as little harm by your rashness as possible.”

Gavin’s look of triumph changed to one of utter bewilderment, and then to one of mingled rage and horror. General Loudon, without another word, rode off. Gavin, half choking, cried to St. Arnaud:

“But you know what I went after? My first sergeant was shot through both legs—the fellow was in the lead—and he cried out to me to come and save him. Just then I heard the bugle, but could I leave that poor fellow there to die?”

“Certainly not; and this shall be known; but you were very rash in the beginning; so come on, and wash your face the first time you come to water.”

The rest of that day was like an unhappy dream to Gavin. They were again on the march by three o’clock, and at bivouac they had rejoined the main body.

Their camp that night was well beyond Olmutz, and led them again toward the mountains. When all the arrangements for the night were made, and their tent was pitched, St. Arnaud, who had been absent for half an hour, returned and looked in. He saw Gavin sitting on the ground in an attitude of utter dejection.

“Come,” cried St. Arnaud gayly; “you take the general too seriously; he was angry with you, and so was I, for that matter; but he knows all the facts now.”

“It is of no consequence,” replied Gavin sullenly. But when St. Arnaud urged him, he rose and joined him for a stroll about the camp. As they were walking along a little path that led along the face of a ravine, they saw, in the clear twilight of the June evening, General Loudon, quite unattended, approaching them. Gavin would have turned off, but St. Arnaud would not let him. As they stood on the side of the path, respectfully to let the general pass, he stopped and said in the rather awkward way which was usual with him: