TABLE OF CONTENTS

A NineStar Press Publication

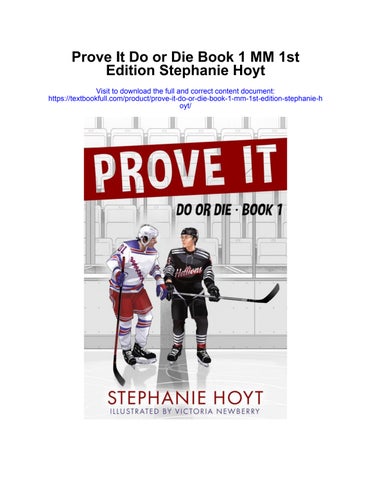

Prove It

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Connect with NineStar Press

www.ninestarpress.com

ISBN: 978-1-64890-722-7

© 2024 Stephanie Hoyt

Cover Design © 2024 Jaycee DeLorenzo

Cover Art © 2024 Victoria Newberry

Published in February 2024 by NineStar Press, New Mexico, USA.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form, whether by printing, photocopying, scanning or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact NineStar Press at Contact@ninestarpress.com.

Also available in Print, ISBN: 978-1-64890-723-4

CONTENT WARNING:

This book contains sexually explicit content, which may only be suitable for mature readers. Depictions of homophobic attitudes.

Do or Die, Book One

StephanieHoyt

Oh, mama don’t you cry, USA hockey is do or die.

Chapter One

THERE’S A NOISE to Noah’s left. He expects to see his dad, annoyed and ready to tell Noah every way he should’ve done better, how he’s never going to make it in the NHL if he keeps hiding from all his problems instead of facing them head on. He’s gearing up for another blow to this lackluster eighteenth birthday when he glances over at Alex Valencia walking down the row toward him. For a fleeting second, Noah’s relieved he doesn’t have to face his father yet. Then Alex takes the seat next to him and the image of hats flying to the ice after Alex scored the game winner for the United States flashes through his mind and irritation floods through him.

“Come to gloat about your buzzer beater?”

“Does that sound like something I’d do, Anderson?”

Noah drags his attention away from the Zamboni smoothing over the ice to find Alex smiling at him. Which isn’t unexpected—Alex has the opposite of a resting bitch face—but this smile is different from any Noah’s ever received. This one doesn’t match the earnest incandescence Noah has never understood, but now expects from Alex.

Noah’s shocked by how much he hates it. Even more so when he admits, “No, I suppose not.”

He wouldn’t say he’s an expert on Alex’s smiles—they barely know each other—but he’s seen enough to recognize the transformation. A second ago, it was subdued, a little tight, but now he’s grinning, loose and broad enough to dimple his cheeks. This one’s real and Noah has an inexplicable, yet familiar, desire to press

his thumb to Alex’s tan skin and measure the depth of his left dimple always a little more pronounced than the right. Noah’s stomach twists and his heartbeat ratchets up—he can’t afford to still have these thoughts.

Hockey is already a parasitic environment, but being attracted to the one guy he can’t escape is another level of hell entirely. No one, from his dad to the reporters covering their international matchups, can shut up about how Alex would be the clear first overall if Noah wasn’t in his draft class and if anyone could upset the predictions, Alex’s strength and size might give him the edge to do it.

Which…fine. Whatever. Noah can’t fix his height, but he can get stronger and if he has to measure himself against Alex, who truly is phenomenal, to know he’s trying hard enough, then so be it. And maybe, if Alex weren’t gorgeous—with his perfect smile, perfect cheekbones, perfect jaw, perfectly silky-smooth hair—Noah wouldn’t hate it so much. But Alex is stunning, and every time someone mentions his name, everything Noah wants but can never have flashes before his eyes.

Which, for the record, isn’t Alex.

Noah might not know Alex, but after years of crossing paths, he’s pretty confident he’s too much for all of Noah’s anxieties to handle in large doses. Alex is loud and vibrant and always moving. His personality draws people in and keeps them, and he seems to thrive off it. Alex is everything Noah isn’t and nothing he wants to be around.

Noah wants the freedom to fall in love, to live without the pressure to blend in—constantly worried someone can tell he isn’t straight. Noah doesn’t want Alex, but Noah looks at him and his chest aches for what could be if he liked girls, if he didn’t care what people thought of him, if hockey wasn’t such a toxic environment. He looks at Alex and he wants.

Not for the first time, Noah hopes they get drafted to different conferences. He’s not naïve. He knows their first matchup in the NHL will be a big deal regardless of where it happens, but only playing twice a year should mitigate the fuss. If Noah’s lucky, their so-called rivalry will fade into the nonexistent thing Noah wishes it already was.

“Why’re you here then?” Noah asks. “Wanted to say happy birthday.”

Noah’s pulse skyrockets and his stomach swoops under Alex’s unwavering attention. He sounds so genuine, but Noah narrows his eyes. “How do you know it’s my birthday?” Alex averts his gaze and Noah nearly laughs. “Was someone gloating about my birthday loss?”

“It might’ve come up.”

Noah snorts. “And what you found me out of the kindness of your heart?”

“Who said I was looking for you? Maybe we both wanted some quiet and when I saw you sulking, I thought, ‘Must suck to lose on your birthday—lemme go cheer him up.’”

Noah arches an eyebrow. “There’s no way you don’t thrive in post-win chaos.”

Alex tilts his head to the side, mouth slanting in a tiny grin. “You’ve got me there.”

Noah purses his lips. He doesn’t understand why Alex keeps seeking him out. The first time, it was understandable. Enough scouts had hyped up the two of them facing off in the u-17 Challenge that Alex doubling back in the hotel lobby the night before their game wasn’t unexpected. Despite years of hearing how good he is, Alex saying he looked forward to playing Noah becausehe was so talented still threw him off. He’s never taken praise well, but Noah couldn’t even stumble through a thanks for Alex’s earnestness.

Noah was embarrassing and rude and, despite Alex finding him after every tournament to tell Noah how well he played, he never adapted. Alex’s attention gets under Noah’s skin, their interactions leaving him restless and unbalanced, unsure of how to act.

“You had a good game,” Noah says, hoping he can avoid Alex complimenting him if he does it first. “Keep any of the hats?”

“Yeah, can never have too many.”

Noah turns back to the ice as his traitorous mouth twitches in a smile. “Of course.”

“Even found a Canadian one in the mix.”

Noah snorts. “Sure you did.”

“Look.”

Noah does, right in time to catch the black cap Alex was wearing moments before. Noah flips the cap over to find the Hockey Canada logo and absolutely doesn’t laugh. “So much for team loyalty.”

“We’ve learned a valuable lesson here tonight.”

Noah can’t help himself. “Oh, yeah? What’s that?”

“Hatties outrank patriotism.”

Alex’s smile is sunshine bright and if this were Julien, Noah might even smile back. But Noah refuses to let his guard down around Alex, no matter how tempting he always makes it. He and Alex aren’t friends. They never will be.

With nothing more to say, the silence stretches between them. Then Alex stands and taps Noah’s forearm. “Keep the hat.”

Noah meets Alex’s gaze. His smile is soft, guarded maybe.

He attempts his most winning smile; he’s certain it falls flat. “If we meet in the final—you’re going to lose.”

Alex walks down the row backward, grin turning sly. “Better wish for it when you blow those candles out tonight, then.”

“Don’t worry. I won’t need to.”

Alex tips his head back in a loud, honking laugh. Despite how ridiculous he sounds, Noah has to push down the warm flutter in his chest—hopefully for good this time.

Chapter Two

ALEX WOULDN’T SAY he’s superstitious, but when they go into the gold medal game against Team Canada, he’s quietly thankful he only impliedhis team would win while Anderson straight up said it.

It doesn’t matter in the end. Anderson was right.

When both goalies are hot, Alex’s lone goal in the first can only get them so far. With two minutes left in the game, the puck hits Anderson’s tape and time seems to slow. Alex’s chest constricts as Anderson’s pass connects with Thorn’s stick right in front of the net. Thorn beats Beaver by a hair’s breadth. The puck squeaks between the bar and Beaver’s glove for the go-ahead goal that leaves Team USA racing against the clock.

He doesn’t come away with another eleventh-hour goal to tie it up; Canada wins and Alex’s stomach bottoms out, heart hollow and defeated.

Beaver has tears in his eyes as they skate back to the bench. Parse still has his helmet on as he rests his head against the boards. Ben drops his hand to Parse’s neck and squeezes, but Parse doesn’t even move. Alex wants to ignore the celebration going on around him, but his eyes sting from the forlorn slump of his teammates and Alex hates that more.

He turns away right in time to see Thorn lift Anderson off his skates in a hug, their flushed faces lit up in victory. Thorn sets Anderson down and before Alex can look away, their eyes meet. Alex’s heart aches, but he still musters a smile. Anderson blinks,

excitement flickering to surprise before he nods at Alex with a timid smile that makes Alex’s stomach lurch.

Then Ben’s at his side, pulling him into a hug, and time passes in a blur—medals and anthems, subdued post-game media scrums, and a silent bus, heavy footsteps as they pile into Parse and Beaver’s room to pass whiskey between one another while they sulk.

The crushing weight of failure becomes too much with them all pressed together in one hotel room and Alex escapes to the roof, the thrum of alcohol in his blood convincing him the cold might shock the sadness away.

It doesn’t.

But Anderson startles at the opposite end of the rooftop when the door squeaks open, and that cuts through it some. Alex joins Anderson at the railing and bumps their shoulders together. “While I’d never complain about getting a moment alone with Canada’s golden boy—”

Anderson makes a dismissive sound.

“Oh, come on. Acknowledging the masses think you’re God’s gift to hockey won’t hurt my feelings.”

Noah wrinkles his nose. “You’re no hand-me-down.”

Alex grins, chest swelling. “Don’t hurt yourself there, bro.”

Anderson scowls, but that’s par for the course and Alex won’t let it deter him. He kicks the sole of Anderson’s shoe. “Seriously, shouldn’t you be off celebrating in a sea of red and white? Why’re you up here?”

Anderson narrows his eyes. “Why’re you?”

He asks Alex some version of this every time they interact, and Alex never has an adequate answer. He gets under Alex’s skin though; makes him want to work a reaction out of him, leaves him aching for a sign he isn’t taking this rivalry so damn seriously.

“Rooftop’s a pretty good place to sit with your failures after losing, don’t you think?”

Anderson rolls his eyes. “You didn’t even bring a scarf.” His gaze drops to Alex’s hands. “Or gloves. You’re not prepared for sulking.”

“Oh, this is nothing.”

Noah scoffs. “Yeah, okay. Aren’t you from—” He takes a beat, eyebrows knitting, mouth pressed in an impossibly thin line. He blows out a sharp breath. “—a non-traditional hockey market?”

He doesn’t think Noah means to be funny, but Alex cackles regardless. “I can’t believe you used ‘non-traditional hockey market’ as a geographical marker.”

“But aren’t you?”

“Texas forever, baby.”

Noah doesn’t smile, but there’s a tiny upward slant to his mouth when he looks back out over the city that keeps Alex there after the silence turns tense. He would usually leave by now, but they were so closeto gold and Alex needs a distraction. “Why are you here? You never said.”

Noah doesn’t answer, but he turns back, and despite the beanie pulled low over his ears and the scarf looped around his neck, his

cheeks are still rosy from the chill. He looks warm, soft, and entirely too upset for someone who just won gold.

“Hey, I’m the one who lost; you could at least indulge me out of sympathy.”

Anderson exhales sharply and another long moment passes where he seems to fall back on his usual play—icing Alex out until he leaves—before he grimaces and says, “Too loud. Too much t—” He pulls his bottom lip between his teeth and his shoulders jump in an aborted sort of shrug. “I don’t know. It’s a lot. I needed a minute.”

Alex doesn’t know what to make of the admission, let alone how to respond, but it doesn’t matter. He doesn’t have time to stumble through asking for a clarification before one of Anderson’s teammates bursts through the rooftop door and saves Alex from prying with a loud shout.

“Finally! Thor said you might be up here.”

He’s as pumped as Alex expected Anderson to be, barely even dimming when he notices Alex.

“Hey, Valencia,” Connor says. At least Alex thinks his name is Connor. It might be Cole. Definitely a C.

“Hey.” Alex moves to leave. “Congratulations on the win.”

“Thanks.” Maybe-Connor slings an arm around Anderson’s shoulders, unperturbed by the way he tenses under the weight. “Come on, man. The boys are asking for you.”

Something twists in Alex’s chest, and he wants to ask—needs to ask. Alex has never seen Anderson flinch away from a hit; has

watched him celly with his teammates, justsaw Thorn sweep him off his feet. But here, outside the rink, a casual touch has set him on edge and Alex can’t help but wonder if touching is what Noah stopped himself from saying.

Once again, Connor doesn’t give him the chance. He practically drags Anderson inside, and Alex has the inexplicable urge to fling Connor’s arm off Anderson’s stiff shoulders and snap at him for not realizing how uncomfortable he’s making his friend. But no matter his efforts, he and Anderson aren’t friends and Connor is his teammate—if one of them is misreading Anderson, it’s probably not Connor.

Alex’s fingers really are cold, but he shoves his hands in his pockets and stays put, unwilling to get stuck in the elevator with them, and tries not to dwell on what Anderson meant and why today, of all days, he gave Alex an inch.

Chapter Three

NOAH WOULD LOVE to spend the five months between World Juniors and the Combine free of Alex, but it’s impossible to avoid talking about the tournament, and with every mention of World Juniors comes a new memory of Alex—the heat of him by Noah’s side, his assessing gaze in the empty rink, the infuriating way he smiled at Noah after losing, how he seemed so genuinely curious about why Noah wasn’t off celebrating. Thankfully, winning gold earns Noah a reprieve from his dad’s unrelenting comparisons to Alex, and the reporters’ questions roll right off his shoulders when he’s not caught up in needing to be far better than Alex to impress his own dad.

Paul Anderson can only go so long without criticizing Noah though, and when they get shut out twice in a row in the second week of February, he doubles down. When he’s pushing too hard, insisting Noah’s game must be flawless since he’s so much smaller than Alex, a spiteful anger twists through Noah, and he wishes he’d go second.

Noah wants to be the best more than he wants to piss his dad off, but sometimes, it’s so hard to separate hockey from his father’s unrelenting criticism. Hockey is both the rush of calm he gets when he steps on the ice and the knots of anxiety tightening in his stomach as his dad shakes off his mom’s warning hand and moves to the other room to pick Noah’s game apart on FaceTime. Noah loves hockey, but it’s so much easier in those moments to hate the

game than it is to hate his dad and resent his mom for never successfully stopping him.

They don’t drop a game after their back-to-back shutouts; Noah finishes the regular season with his longest point streak yet, and he’s once again unable to imagine doing anything other than flying down the ice until his body won’t let him anymore.

He’s so damn happy to finish his last season in the Dub with a playoff run that getting asked about Alex for the first time in months doesn’t even ruin his mood. His face, sweaty and flushed after a win, still floods his mind when a reporter brings up Alex’s impressive start to the USHL playoffs, but Noah’s so pleased with his own performance that his smile doesn’t even drop when the reporter asks, “Are you worried about the growing speculation that this tear might be enough for some teams to take him over you in the draft?”

“It’s no secret Alex is good,” Noah starts, getting a laugh from the scrum, “but that doesn’t worry me. It motivates me.” He huffs out a laugh. “Maybe more than anything else does.”

“What do you mean?” the same reporter asks, the quirk of his eyebrow suggesting he wasn’t expecting this much honesty.

“I’d hate to feed into the rivalry or imply I’m losing sleep over being better than Alex Valencia,” Noah says, which isn’t true, but these guys don’t need details on all the sleepless nights his dad’s obsession has caused. “But honestly, he’s so talented and if I can match him, if I can be better than him, then I’m good too.” Noah swipes at the sweaty curls plastered against his forehead. “I don’t know how things will go in June; Alex could easily go first. And if he

does, I’ll need to push myself harder in the league to prove myself. But for right now, I’m focused on winning the championship and then winning the Memorial Cup. Once we’ve done that, I’ll think more about the draft.”

Giving the press a sound bite about Alex always gets back to his dad and Noah knows he shouldn’t have been so honest. But Noah was happy, muscles burning from a long game, head buzzing with post-win adrenaline, and he wasn’t thinking about his dad, or the way he’d insist Noah can’t say Alex is better and expect to be drafted first because no team wants a guy who lacks confidence.

When Alex follows him on Instagram after and DMs him a clip of Noah’s interview paired with, I’m so happy I couldhelp shape you intoCanada’s nextgoldenboy ��, Noah can no longer dwell on the sick pleasure his father must derive from being an overbearing asshole. He’s too preoccupied with how Alex will be his undoing if the focus on their alleged rivalry doesn’t fade into a distant memory once the draft is over.

Noah knows better than to put faith in luck letting him escape Alex and the way he has become a soul-crushing reminder of his dad’s criticism. The draft lottery happens, and instead of being separated by miles and miles of land, New Jersey and New York jump spots to land the first and second picks and now, no matter who goes first overall, he and Alex will always be the draft rivals taken by rival teams.

It’s a relief when Alex doesn’t DM him after the lottery. Noah’s a game away from the President’s Cup Final and he doesn’t have time

to figure out Alex’s ulterior motives here. Still, he allows himself a moment to wonder if Alex’s silence means he’s given up on whatever this whole thing was.

Luck really isn’t on his side though, and when he swipes into his hotel room at the Combine, he finds Alex splayed out in bed, scrolling through his phone.

It’s not too late, but Noah came straight to Buffalo from winning the Memorial Cup. He’s tired, a little frayed, a little nervous for the Combine, and the only word he can muster when Alex turns his sleepy, soft expression on him is, “No.”

Alex’s relaxed expression shifts infinitesimally, too fast for Noah to decipher, and then he smiles, big and bright, like he’s won something.

“Anderson!”

“Alex.”

Alex nods his head, a strand of hair falling in his eyes, his smile never faltering despite the narrowing of his eyes. “Babe, you’re too glum for someone who just won the Memorial Cup.”

Noah grinds his teeth and refuses to rise to Alex’s bait, or the smug little grin he catches out of the corner of his eye. Instead, he unloads everything for his nightly routine and allows himself to put off unpacking until tomorrow.

“Are you always this quiet?” Alex asks as Noah steps out of the bathroom, steam billowing out behind him.

“I thought you’d be asleep by now,” Noah mumbles, glancing in Alex’s direction despite his better judgment.

“He speaks!”

Noah climbs into bed, pointedly not looking in Alex’s direction. “Sometimes.”

“You might not know this about me, but I’m pretty chatty—”

Noah snorts. “I hadn’t noticed.”

“Yes, well, it’s going to be a long week if you’re going the silent treatment route.”

Noah slides his gaze over. Alex is still smiling, always smiling, and Noah loses the will to ignore him. “Not having anything to say isn’t the same as giving you the silent treatment.”

“I don’t get you,” Alex says after a beat.

“There’s nothing to get.” Noah burrows into his blanket and stares at the ceiling. “Not everyone’s got a motor mouth and no filter.”

“Hey! I have a filter.”

Noah turns on his side to face Alex. “Do you?”

Alex mirrors Noah, blanket pulled up to his chin, eyes glinting in the dim light. “I haven’t even brought up being division rivals once since you got here. That’s me filtering.”

“Doesn’t really count when you just did, now does it?”

Alex smiles. “Probably not. But I had to prove a point. And I haven’t asked if you’re pissed about it, so in the grand scheme of

things, it very much counts as having a filter.”

“Sure,” Noah says, eyes dropping as he finally gets comfortable.

“Come to breakfast with me in the morning,” Alex says, startling Noah out of his half sleep.

“What?”

“Me and Husky are going to breakfast before the interviews start. You should come.”

Alex has never given Noah a reason to think he’s being anything but kind, but Noah doesn’t trust his earnestness, doesn’t believe such a bright and energetic person would ever dispense so much time on trying to be Noah’s friend when he’s quiet, contained, uptight. Even if Noah wasn’t suspicious, getting close to Alex would still be an awful idea. For the sake of Noah’s sanity, he can never be friends with the living reminder of all things Noah can’t have if he wants a long and successful career. “Thanks, but I’m pretty sure me and Thor have similar plans.”

Alex blinks slowly; his smile doesn’t dim. “Your loss.”

“SAW VALENCIA LEAVING your room,” Julien says when Noah opens the door in the morning. “You two rooming together? Or is he still trying to win you over?”

Noah follows Julien down the hall. “Both.”

“You know, if I didn’t know he was dating an absolute rocket, I might assume he’s into you.”

Noah chokes. “What?”

Julien pushes the elevator call button. “I’m totally chill with it. I’m down with whoever wants to fly their rainbow flag. But come on, you’ve never thought that might be his deal?”

Noah’s brain might be short circuiting. “Uh, no. I can honestly say that’s nevercrossed my mind.”

Julien shakes his head as he steps on the elevator. “Should’ve known better than to expect your oblivious ass to catch onto anything. But really, I don’t get him. No offense, but you’re a dick why does he even bother?”

“Wow. Who’s being a dick now?”

“It’s not being a dick if I’m stating a fact! Anyone who’s spent five minutes with you knows you’re a prickly little bitch 90 percent of the time.”

“I’m notprickly.”

Julien looks unimpressed. “I’ve known you since we were what twelve? And I’ve seen you smile twice.”

Noah shoves Julien’s shoulder and smirks when he thumps against the side wall. “Fuck off. I’ve smiled atleastfive times in your presence.”

“You’re absolutely rounding up there, bud.”

“What exactly do I have to smile about when you’re such an ass?” Noah asks, the frenetic whir of his thoughts quieting as the conversation devolves. This is easy; this is familiar.

“I will literally fight you if you don’t smile when you go number one,” Julien says, face split into a wide, open smile as they step out

of the elevator.

“Alex could easily go first.”

Julien drops his voice. “I know your dad likes to shove that shit down your throat to wind you up, make you work harder, but come on. We all know how it’s going to go: you, then him.”

“Maybe.”

“Just me and you, Noah,” Julien says, which isn’t entirely true since they’re walking through the hotel lobby at breakfast time with people scattered all around. “No need to give me the media sound bite. I won’t call you cocky for saying you’re the cream of this year’s crop.”

Noah spots JT and Max at the entrance and calls out for them before responding. “Let’s see how the Combine goes. Might even let you take a picture of me smiling if it goes the way you say. You know, for posterity’s sake.”

Julien barks out a laugh. “You’re going to regret this deal when I cross-post it on every one of my socials.”

Noah rolls his eyes, but it’s finally sinking in that Julien would be chill with a hockey player coming out and he ends up grinning even as Julien says, “Jay! Brownie! Is Noah a prickly bitch?”

JT answers without hesitation. “A straight up cactus.”

“I’d say he’s a porcupine. Soft on the downstroke, but yeah,” Max says with an apologetic smile. “Definitely prickly.”

Noah huffs, Julien smirks, and the conversation turns into a verbal highlight reel of their favorite examples of Noah being a

moody asshole until Noah flushes all the way down his neck and across his collarbones. Unlike his dad, his friends recount them as amusing anecdotes to laugh with Noah about, not flaws deserving derision. He isn’t laughing, but he’s close to it, and that’s enough to distract Noah from the unnerving possibility Alex has flirtedwith him.

NHL Combine: Valencia bests Anderson in fitness testing

The last time Alex Valencia and Noah Anderson went head-to-head,Andersoncameoutontopaftersettingup JulienThorn’sgoldengoalatthe2022IIHFWorldJunior Championship.

On Saturday, the Combine’s fitness testing served as a rematch of sorts and Valencia outscored Anderson in every category. As the near unanimous consensus for first overall, Anderson’s results likely wouldn’t have affected his chances of going to Jersey, but given his smaller stature being the one thing he doesn’t have on Valencia, the results were far closer where it matters most.

BY THE END of the week, Noah has a catalog of information he never wanted about Alex. His hair is a mess when he wakes up, but it’s good as new once he swipes his giant hand through it. He’s an expanse of smooth tan skin with a constellation of small moles across his left ribs. He thinks nature documentaries are the perfect

background noise, has a massive sweet-tooth, and the only time he doesn’t talk a mile a minute is when he first wakes up and his voice is deep and scratchy.

And the most devastating part of rooming with him is that, despite his best efforts, Noah doesn’t find Alex nearly as off-putting as he did when he got to Buffalo. Then Alex outperforms him in every single category of the fitness test on Saturday and reality crashes over him.

His dad’s voice is sharp and grating over the phone when he says, for the millionth time, “You needed to outperform him this week to secure your spot, but you couldn’t even do better in one category. Are you committed to being the best or not?”

Noah grits his teeth. “I am. I’m trying.”

“Not good enough.”

“I’m still one of the best, Dad. New Jersey’s interested. The interview went well.”

“Noah.”

His dad says his name with such scorn and Noah can’t stand hearing how short he falls anymore.

“There was an article I read about the interview process,” he says, rushed and desperate, “and how it’s basically the most important part. How the tests rarely change their interest because teams know who they want, and the interview will confirm if they’re a fit.”

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

The Project Gutenberg eBook of In the three zones

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: In the three zones

Author: Frederic Jesup Stimson

Release date: June 20, 2022 [eBook #68351]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893

Credits: D A Alexander and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by University of California libraries)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN THE THREE ZONES ***

I

������ like some time to tell how Tetherby came to his end; he, too, was a victim of materialism, as his father had been before him; but when he died, he left this story, addressed among his papers to me; and I am sure he meant that all the world (or such part of it as cares to think) should know it. He had told it, or partly told it, to us before; in fragments, in suggestions, in those midnight talks that earnest young men still have in college, or had, in 1870.

Tetherby came from that strange, cold, Maine coast, washed in its fjords and beaches by a clear, cold sea, which brings it fogs of winter but never haze of summer; where men eat little, think much, drink only water, and yet live intense lives; where the village people, in their long winters away from the world, in an age of revivals had their waves of atheism, and would transform, in those days, their pine meeting-houses into Shakspere clubs, and logically make a cult of infidelity; now, with railways, I suppose all that has ceased; they read Shakspere as little as the scriptures, and the Sunday newspaper replaces both. Such a story—such an imagination—as Tetherby’s, could not happen now—perhaps. But they take life earnestly in that remote, ardent province; they think coldly; and, when you least expect it, there comes in their lives, so hard and sharp and practical, a burst of passion.

He came to Newbridge to study law, and soon developed a strange faculty for debate. The first peculiarity was his name—which first appeared and was always spelled, C. S. J. J. Tetherby in the catalogue, despite the practice, which was to spell one’s name in full. Of course, speculation was rife as to the meaning of this portentous array of initials; and soon, after his way of talk was known, arose a popular belief that they stood for nothing less than Charles Stuart Jean Jacques. Nothing less would justify the intense leaning of his

mind, radical as it was, for all that was mystical, ideal, old. But afterwards we learned that he had been so named by his curious father, Colonel Sir John Jones, after a supposed loyalist ancestor, who had flourished in the time of the Revolution, and had gone to Maine to get away from it; Tetherby’s father being evidently under the impression that the two titles formed a component part of the ancestor’s identity.

Rousseau Tetherby, as he continued to be called, was a tall, thin, broad-shouldered fellow, of great muscular strength and yet with feeble health, given to hallucinations and morbid imaginations which he would recount to you in that deep monotone of twang that seemed only fit to sell a horse in. The boys made fun of Tetherby; he bore it with a splendid smile and a twinkle in his ice-blue eye, until one day it went too far, and then he tackled the last offender and chucked him off the boat-house float into the river. He would have rowed upon the university crew, but that his digestion gave out; strong as he was in mind and body, nothing, that went for the nutrition and fostering of life, was well with him. Such men as he are repellent to the sane, and are willed by the world to die alone.

Some one on that night, I remember, had said something derogatory about Goethe’s theory of colors. A dry subject, an abstruse subject, a useless subject—as one might think—but it roused Tetherby to sudden fury. He made a vehement defence of the great poet-philosopher against the dry, barren mathematics of the Newtonian science.

“Do you cipherers think all that is reducible to numbers? to so many beats per second, like your own dry hearts? Sound may be nothing but a quicker rattle—is it but a rattle, the music in your souls? If light is but the impact of more rapid molecules, does MAN bring nothing else, when he worships the glory of the dawn? You say, tones are a few thousand beats per second, and colors a few billion beats per second—what becomes of all the numbers left between? If colored lights count all these billions, up from red to

violet, and white light is the sum of all the colors, what can be its number but infinity? But is a white light GOD? Or would you cipherers make of God a cipher? Smoke looks yellow against the sky, and blue against the forest—but how can its number change? You, who make all to a number, as governments do to convicts in a prison! I tell you, this rage for machinery will bear Dead Sea fruit. You confound man’s highest emotions with the tickling of the gray matter in his brain; that way lies death and suicide of the soul——”

We stared; we thought he had gone crazy.

“Goethe and Dante still know more about this universe than any cipherer,” he said, more calmly. And then he told us this story; we fancied it a nightmare, or a morbid dream; but earnestly he told it, and slowly, surely, he won our hearts at least to some believing in the terror of the tale.

When he was through, we parted, with few words, thinking poor Tetherby mad. But when he died it was found among his papers, addressed to me. Materialism had conquered him, but not subdued him; “say not the struggle naught availed him” though he left but this one tract behind. It is only as a sermon that it needs preserving, though the story of poor Althea Hardy was, I believe, in all essentials true.

I was born and lived, until I came to this university, in a small town in Maine. My father was a graduate of B—— College, and had never wholly dissolved his connection with that place; probably because he was there are not unfavorably know to more acquaintances, and better people, than he elsewhere found. The town is one of those gentle-mannered, ferocious-minded, white wooden villages, common to Maine; with two churches, a brick townhall, a stucco lyceum, a narrow railway station, and a spacious burying-ground. It is divided into two classes of society: one which institutes church-sociables, church-dances, church-sleighing parties; which twice a week, and critically, listens to a long and ultra-

Protestant, almost mundane, essay-sermon; and which comes to town with, and takes social position from, pastoral letters of introduction, that are dated in other places and exhibited like marriage certificates. I have known the husbands at times get their business employments on the strength of such encyclicals (but the ventures of these were not rarely attended with financial disaster, as passports only hinder honest travellers); the other class falling rather into Shakespeare clubs, intensely free-thinking, but calling Sabbath Sunday, and pretending to the slightly higher social position of the two. This is Maine, as I knew it; it may have changed since. Both classes were in general Prohibitionists, but the latter had wine to drink at home.

In this town were many girls with pretty faces; there, under that cold, concise sky of the North, they grew up; their intellects preternaturally acute, their nervous systems strung to breaking pitch, their physical growth so backward that at twenty their figures would be flat. We were intimate with them in a mental fellowship. Not that we boys of twenty did not have our preferences, but they were preferences of mere companionship; so that the magnanimous confidence of English America was justified; and anyone of us could be alone with her he preferred from morn to midnight, if he chose, and no one be the wiser or the worse. But there was one exceptional girl in B——, Althea Hardy. Her father was a rich ship-builder; and his father, a sea-captain, had married her grandmother in Catania, island of Sicily. With Althea Hardy, I think, I was in love.

In the winter of my second year at college there came to town a certain Dr. Materialismus—a German professor, scientist, socialist— ostensibly seeking employment as a German instructor at the college; practising hypnotism, magnetism, mesmerism, and mysticism; giving lectures on Hegel, believing in Hartmann, and in the indestructibility of matter and the destructibility of the soul; and his soul was a damned one, and he cared not for the loss of it.

Not that I knew this, then; I also was fascinated by him, I suppose. There was something so bold about his intellectuality, that excited my admiration. Althea and I used to dispute about it; she said she did not like the man. In my enthusiasm, I raved to her of him;

and then, I suppose, I talked to him of her more than I should have done. Mind you, I had no thought of marriage then; nor, of course, of love. Althea was my most intimate friend—as a boy might have been. Sex differences were fused in the clear flame of the intellect. And B—— College itself was a co-educational institution.

The first time they met was at a coasting party; on a night of glittering cold, when the sky was dusty azure and the stars burned like blue fires. I had a double-runner, with Althea; and I asked the professor to come with us, as he was unused to the sport, and I feared lest he should be laughed at. I, of course, sat in front and steered the sled; then came Althea; then he; and it was his duty to steady her, his hands upon her waist.

We went down three times with no word spoken. The girls upon the other sleds would cry with exultation as they sped down the long hill; but Althea was silent. On the long walk up—it was nearly a mile —the professor and I talked; but I remember only one thing he said. Pointing to a singularly red star, he told us that two worlds were burning there, with people in them; they had lately rushed together, and, from planets, had become one burning sun. I asked him how he knew; it was all chemistry, he said. Althea said, how terrible it was to think of such a day of judgment on that quiet night; and he laughed a little, in his silent way, and said she was rather too late with her pity, for it had all happened some eighty years ago. “I don’t see that you cry for Marie Antoinette,” he said; “but that red ray you see left the star in 1789.”

We left Althea at her home, and the professor asked me down to his. He lived in a strange place; the upper floor of a warehouse, upon a business street, low down in the town, above the Kennebec. He told me that he had hired it for the power; and I remembered to have noticed there a sign “To Let—One Floor, with Power.” And sure enough, below the loud rush of the river, and the crushing noise made by the cakes of ice that passed over the falls, was a pulsing tremor in the house, more striking than a noise; and in the loft of his strange apartment rushed an endless band of leather, swift and silent. “It’s furnished by the river,” he said, “and not by steam. I thought it might be useful for some physical experiments.”

The upper floor, which the doctor had rented, consisted mainly of a long loft for manufacturing, and a square room beyond it, formerly the counting-room. We had passed through the loft first (through which ran the spinning leather band), and I had noticed a forest of glass rods along the wall, but massed together like the pipes of an organ, and opposite them a row of steel bars like levers. “A mere physical experiment,” said the doctor, as we sank into couches covered with white fur, in his inner apartment. Strangely disguised, the room in the old factory loft, hung with silk and furs, glittering with glass and gilding; there was no mirror, however, but, in front of me, one large picture. It represented a fainting anchorite, wan and yellow beneath his single sheepskin cloak, his eyes closing, the crucifix he was bearing just fallen in the desert sand; supporting him, the arms of a beautiful woman, roseate with perfect health, with laughing, red lips, and bold eyes resting on his wearied lids. I never had seen such a room; it realized what I had fancied of those sensuous, evil Trianons of the older and corrupt world. And yet I looked upon this picture; and as I looked, some tremor in the air, some evil influence in that place, dissolved all my intellect in wild desire.

“You admire the picture?” said Materialismus. “I painted it; she was my model.” I am conscious to-day that I looked at him with a jealous envy, like some hungry beast. I had never seen such a woman. He laughed silently, and going to the wall touched what I supposed to be a bell. Suddenly my feelings changed.

“Your Althea Hardy,” went on the doctor, “who is she?”

“She is not my Althea Hardy,” I replied, with an indignation that I then supposed unreasoning. “She is the daughter of a retired seacaptain, and I see her because she alone can rank me in the class. Our minds are sympathetic. And Miss Hardy has a noble soul.”

“She has a fair body,” answered he; “of that much we are sure.”

I cast a fierce look upon the man; my eye followed his to that picture on the wall; and some false shame kept me foolishly silent. I should have spoken then.... But many such fair carrion must strew the path of so lordly a vulture as this doctor was; unlucky if they

thought (as he knew better) that aught of soul they bore entangled in their flesh.

“You do not strain a morbid consciousness about a chemical reaction,” said he. “Two atoms rush together to make a world, or burn one, as we saw last night; it may be pleasure or it may be pain; conscious organs choose the former.”

My distaste for the man was such that I hurried away, and went to sleep with a strange sadness, in the mood in which, as I suppose, believers pray; but that I was none. Dr. Materialismus had had a plum-colored velvet smoking-jacket on, with a red fez (he was a sort of beau), and I dreamed of it all night, and of the rushing leather band, and of the grinding of the ice in the river. Something made me keep my visit secret from Althea; an evil something, as I think it now.

The following day we had a lecture on light. It was one in a course in physics, or natural philosophy, as it was called in B—— College; just as they called Scotch psychology “Mental Philosophy,” with capital letters; it was an archaic little place, and it was the first course that the German doctor had prevailed upon the college government to assign to him. The students sat at desks, ranged around the lecture platform, the floor of the hall being a concentric inclined plane; and Althea Hardy’s desk was next to mine. Materialismus began with a brief sketch of the theory of sound; how it consisted in vibrations of the air, the coarsest medium of space, but could not dwell in ether; and how slow beats—blows of a hammer, for instance—had no more complex intellectual effect, but were mere consecutive noises; how the human organism ceased to detect these consecutive noises at about eight per second, until they reappeared at sixteen per second, the lowest tone which can be heard; and how, at something like thirty-two thousand per second these vibrations ceased to be heard, and were supposed unintelligible to humanity, being neither sound nor light—despite their rapid movement, dark and silent. But was all this energy wasted to mankind? Adverting one moment to the molecular, or rather mathematical, theory—first propounded by Democritus, reestablished by Leibnitz, and never since denied—that the universe, both of mind and matter, body and soul, was made merely by

innumerable, infinitesimal points of motion, endlessly gyrating among themselves—mere points, devoid of materiality, devoid also of soul, but each a centre of a certain force, which scientists entitle gravitation, philosophers deem will, and poets name love—he went on to Light. Light is a subtler emotion (he remarked here that he used the word emotion advisedly, as all emotions alike were, in substance, the subjective result of merely material motion). Light is a subtler emotion, dwelling in ether, but still nothing but a regular continuity of motion or molecular impact; to speak more plainly, successive beats or vibrations reappear intelligible to humanity as light, at something like 483,000,000,000 beats per second in the red ray. More exactly still, they appear first as heat; then as red, orange, yellow, all the colors of the spectrum, until they disappear again, through the violet ray, at something like 727,000,000,000 beats per second in the so-called chemical rays. “After that,” he closed, “they are supposed unknown. The higher vibrations are supposed unintelligible to man, just as he fancies there is no more subtle medium than his (already hypothetical) ether. It is possible,” said Materialismus, speaking in italics and looking at Althea, “that these higher, almost infinitely rapid vibrations may be what are called the higher emotions or passions—like religion, love and hate—dwelling in a still more subtle, but yet material, medium, that poets and churches have picturesquely termed heart, conscience, soul.” As he said this I too looked at Althea. I saw her bosom heaving; her lips were parted, and a faint rose was in her face. How womanly she was growing!

From that time I felt a certain fierceness against this German doctor. He had a way of patronizing me, of treating me as a man might treat some promising school-boy, while his manner to Althea was that of an equal—or a man of the world’s to a favored lady. It was customary for the professors in B—— College to give little entertainments to their classes once in the winter; these usually took the form of tea-parties; but when it came to the doctor’s turn, he gave a sleighing party to the neighboring city of A——, where we had an elaborate banquet at the principal hotel, with champagne to drink; and returned driving down the frozen river, the ice of which Dr. Mismus (for so we called him for short) had had tested for the

occasion. The probable expense of this entertainment was discussed in the little town for many weeks after, and was by some estimated as high as two hundred dollars. The professor had hired, besides the large boat-sleigh, many single sleighs, in one of which he had returned, leading the way, and driving with Althea Hardy. It was then I determined to speak to her about her growing intimacy with this man.

I had to wait many weeks for an opportunity. Our winter sports at B—— used to end with a grand evening skating party on the Kennebec. Bonfires were built on the river, the safe mile or two above the falls was roped in with lines of Chinese lanterns, and a supper of hot oysters and coffee was provided at the big central fire. It was the fixed law of the place that the companion invited by any boy was to remain indisputably his for the evening. No second man would ever venture to join himself to a couple who were skating together on that night. I had asked Althea many weeks ahead to skate with me, and she had consented. The Doctor Materialismus knew this.

I, too, saw him nearly every day He seemed to be fond of my company; of playing chess with me, or discussing metaphysics. Sometimes Althea was present at these arguments, in which I always took the idealistic side. But the little college had only armed me with Bain and Locke and Mill; and it may be imagined what a poor defence I could make with these against the German doctor, with his volumes of metaphysical realism and his knowledge of what Spinoza, Kant, Schopenhauer, and other defenders of us from the flesh could say on my side. Nevertheless, I sometimes appeared to have my victories. Althea was judge; and one day I well remember, when we were discussing the localization of emotion or of volition in the brain:

“Prove to me, if you may, even that every thought and hope and feeling of mankind is accompanied always by the same change in the same part of the cerebral tissue!” cried I. “Yet that physical change is not the soul-passion, but the effect of it upon the body; the mere trace in the brain of its passage, like the furrow of a ship upon the sea.” And I looked at Althea, who smiled upon me.

“But if,” said the doctor, “by the physical movement I produce the psychical passion? by the change of the brain-atoms cause the act of will? by a mere bit of glass-and-iron mechanism set first in motion, I make the prayer, or thought, or love, follow, in plain succession, to the machine’s movement, on every soul that comes within its sphere —will you then say that the metaphor of ship and wake is a good one, when it is the wake that precedes the ship?”

“No,” said I, smiling.

“Then come to my house to-night,” said the doctor; “unless,” he added with a sneer, “you are afraid to take such risks before your skating party.” And then I saw Althea’s lips grow bloodless, and my heart swelled within me.

“I will come,” I muttered, without a smile.

“When?” said the professor “Now.”

Althea suddenly ran between us. “You will not hurt him?” she said, appealingly to him. “Remember, oh, remember what he has before him!” And here Althea burst into a passion of weeping, and I looked in wild bewilderment from her to him.

“I vill go,” said the doctor to me. “I vill leafe you to gonsole her.” He spoke in his stronger German accent, and as he went out he beckoned me to the door. His sneer was now a leer, and he said:

“I vould kiss her there, if I vere you.”

I slammed the door in his face, and when I turned back to Althea her passion of tears had not ceased, and her beautiful bright hair lay in masses over the poor, shabby desk. I did kiss her, on her soft face where the tears were. I did not dare to kiss her lips, though I think I could have done it before I had known this doctor. She checked her tears at once.

“Now I must go to the doctor’s,” I said. “Don’t be afraid; he can do me or my soul no harm; and remember to-morrow night.” I saw Althea’s lips blanch again at this; but she looked at me with dry eyes, and I left her.

The winter evening was already dark, and as I went down the streets toward the river I heard the crushing of the ice over the falls. The old street where the doctor lived was quite deserted. Trade had been there in the old days, but now was nothing. Yet in the silence, coming along, I heard the whirr of steam, or, at least, the clanking of machinery and whirling wheels.

I toiled up the crazy staircase. The doctor was already in his room—in the same purple velvet he had worn before. On his study table was a smoking supper.

“I hope,” he said, “you have not supped on the way?”

“I have not,” I said. Our supper at our college table consisted of tea and cold meat and pie. The doctor’s was of oysters, sweetbreads, and wine. After it he gave me an imported cigar, and I sat in his reclining-chair and listened to him. I remember that this chair reminded me, as I sat there, of a dentist’s chair; and I goodnaturedly wondered what operations he might perform on me—I helpless, passive with his tobacco and his wine.

“Now I am ready,” said he. And he opened the door that led from his study into the old warehouse-room, and I saw him touch one of the steel levers opposite the rows of glass rods. “You see,” he said, “my mechanism is a simple one. With all these rods of different lengths, and the almost infinite speed of revolution that I am able to gif them with the power that comes from the river applied through a chain of belted wheels, is a rosined leather tongue, like that of a music-box or the bow of a violin, touching each one; and so I get any number of beats per second that I will.” (He always said will, this man, and never wish.)

“Now, listen,” he whispered; and I saw him bend down another lever in the laboratory, and there came a grand bass note—a tone I have heard since only in 32-foot organ pipes. “Now, you see, it is Sound.” And he placed his hand, as he spoke, upon a small crank or governor; and, as he turned it slowly, note by note the sound grew higher. In the other room I could see one immense wheel, revolving in an endless leather band, with the power that was furnished by the

Kennebec, and as each sound rose clear, I saw the wheel turn faster.

Note by note the tones increased in pitch, clear and elemental. I listened, recumbent. There was a marvellous fascination in the strong production of those simple tones.

“You see I hafe no overtones,” I heard the doctor say. “All is simple, because it is mechanism. It is the exact reproduction of the requisite mathematical number. I hafe many hundreds of rods of glass, and then the leather band can go so fast as I will, and the tongue acts upon them like the bow upon the violin.”

I listened, I was still at peace; all this I could understand, though the notes came strangely clear. Undoubtedly, to get a definite finite number of beats per second was a mere question of mathematics. Empirically, we have always done it, with tuning-forks, organ-pipes, bells.

He was in the middle of the scale already; faster whirled that distant wheel, and the intense tone struck C in alt. I felt a yearning for some harmony; that terrible, simple, single tone was so elemental, so savage; it racked my nerves and strained them to unison, like the rosined bow drawn close against the violin-string itself. It grew intensely shrill; fearfully, piercingly shrill; shrill to the rending-point of the tympanum; and then came silence.

I looked. In the dusk of the adjoining warehouse the huge wheel was whirling more rapidly than ever.

The German professor gazed into my eyes, his own were bright with triumph, on his lips a curl of cynicism. “Now,” he said, “you will have what you call emotions. But, first, I must bind you close.”

I shrugged my shoulders amiably, smiling with what at the time I thought contempt, while he deftly took a soft white rope and bound me many times to his chair. But the rope was very strong, and I now saw that the frame-work of the chair was of iron. And even while he bound me, I started as if from a sleep, and became conscious of the dull whirring caused by the powerful machinery that abode within the house, and suddenly a great rage came over me.

I, fool, and this man! I swelled and strained at the soft white ropes that bound me, but in vain.... By God, I could have killed him then and there!... And he looked at me and grinned, twisting his face to fit his crooked soul. I strained at the ropes, and I think one of them slipped a bit, for his face blanched; and then I saw him go into the other room and press the last lever back a little, and it seemed to me the wheel revolved more slowly.

Then, in a moment, all was peace again, and it was as if I heard a low, sweet sound, only that there was no sound, but something like what you might dream the music of the spheres to be. He came to my chair again and unbound me.

My momentary passion had vanished. “Light your cigar,” he said, “it has gone out.” I did so. I had a strange, restful feeling, as of being at one with the world, a sense of peace, between the peace of death and that of sleep.

“This,” he said, “is the pulse of the world; and it is Sleep. You remember, in the Nibelung-saga, when Erda, the Earth spirit, is invoked, unwillingly she appears, and then she says, Lass mich schlafen—let me sleep on—to Wotan, king of the gods? Some of the old myths are true enough, though not the Christian ones, most always.... This pulse of the earth seems to you dead silence, yet the beats are pulsing thousands a second faster than the highest sound.... For emotions are subtler things than sound, as you sentimental ones would say; you poets that talk of ‘heart’ and ‘soul.’ We men of science say it this way: That those bodily organs that answer to your myth of a soul are but more widely framed, more nicely textured, so as to respond to the impact of a greater number of movements in the second.”

While he was speaking he had gone into the other room, and was bending the lever down once more; I flew at his throat. But even before I reached him my motive changed; seizing a Spanish knife that was on the table, I sought to plunge it in my breast. But, with a quick stroke of the elbow, as if he had been prepared for the attempt, he dashed the knife from my hand to the floor, and I sank in despair back into his arm-chair.