Economics is, without a doubt, one of the oldest and most interesting subjects in human history It has shaped and formed civilisations, and is the foundation for human collaboration, trade and progress. It has been present since the time of ancient civilisations like Rome and Egypt, and has moulded society into what it is today.

By its nature, Economics is relevant to a whole host of other subjects, and is useful in topics like industrialisation, climate change, political agenda and scientific developments. No matter what subject you take or profession you work in, knowledge of economics can be helpful.

Economics can be defined as the study of how a society organises its money trade and industry, and how a limited amount of resources can be allocated within societies unlimited demand for resources

The study of Economics emphasises the importance of economic issues in a modern society and seeks to encourage an understanding of the world in which we live today and the economic forces that shape all our lives. Economics is an excellent subject for developing personal transferable skills such as the skills of analysis, application and evaluation. It is intellectually robust and of contemporary relevance. In this newsletter the Year 12 A Level Economics Students have demonstrated the breadth of topics that are influenced by Economics and why it is such an important and vital subject to study today.

Equality and Allocation in EconomicsEben A (2)

Investment, Utility and the Luka TradeDanis B (3)

The Financial Sector: The Engine of the UK Economy - Kobi A (5)

Why Interest Rates Still Control the Markets - Henry L (6)

Did the UK do enough to recover from the UK Financial Crisis - Harry T (7)

Lasting Legacy of the Financial Crisis on The UK - Mr. Hughes (8)

Impacts of the Farming Tax - Jack B (10)

Why is there Poverty: Joanna C (11)

Labour Shortages: Why are there Labour Shortages in major sectors - Ed P.C (12)

The Swedish Economy - Oscar L (13)

Impacts of International Sanctions on Rhodesia - Matt B (15)

Consequences of Two Palaces Conflict in Eastern Wu - Zhan T (16)

"ECONOMICS IS EXTREMELY USEFUL AS A FORM OF EMPLOYMENT FOR ECONOMISTS."

JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH

The Housing Crisis: Why are Homes so expensive - Jessica F (18)

Is the UK’s housing market broken?Rehan M (19)

Opportunity Cost of Everyday DecisionsFrancesca H (20)

Irrational Behaviour - Aliya W (21)

The Cost of Learning: How VAT is reshaping Education - Louis S (22)

Should University be Free? The Economics behind Student Debt - Aastha G (23)

Econometric Model Looking into the peer effect in education - Mr. Jones (24)

Newsletter Edited by: Eben A, Louis S, Joanna C, Samuel A

Thank

"THE CURIOUS TASK OF ECONOMICS IS TO DEMONSTRATE TO MEN HOW LITTLE THEY REALLY KNOW ABOUT WHAT THEY IMAGINE THEY CAN DESIGN."

F.A. HAYEK

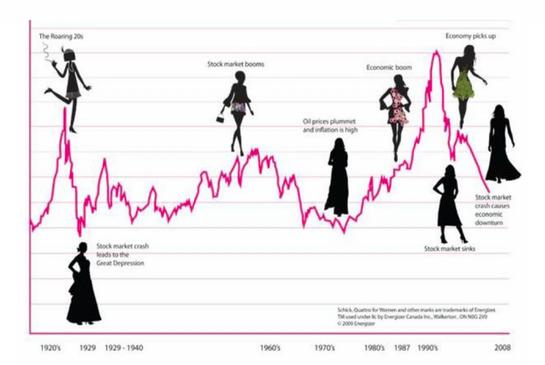

The Rise & Fall of Skirt Lengths: Can Fashion really predict the economy?Valentina Z (28)

Economics of War: Growth, Innovation and Hidden Costs - Yulia B (29)

Should Organ Donation come with a Price Tag - Louise A (32)

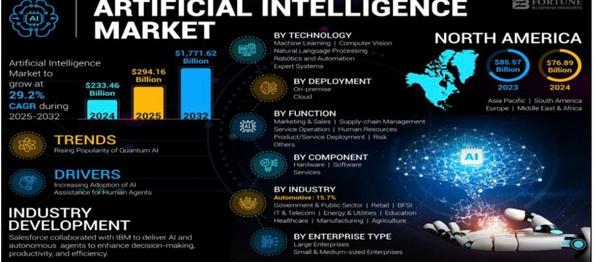

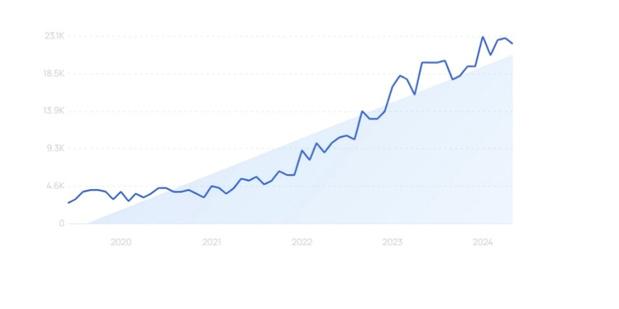

How Artificial Intelligence is changing the Economy - Alice R (35)

AI with Memory, Helpful or harmful?Samuel A (36)

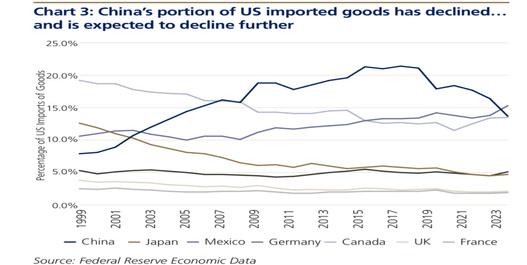

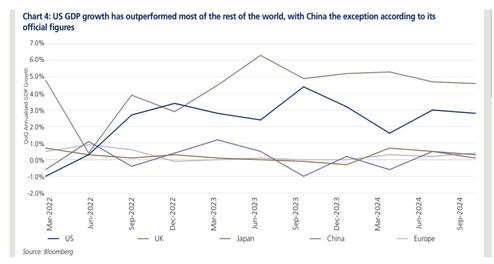

Understanding Trumps Tariffs: Motives, Impacts and Legacy - Jing L (37)

Impacts of Trumps Tariffs and Immigration

Policy - Oliver L (38)

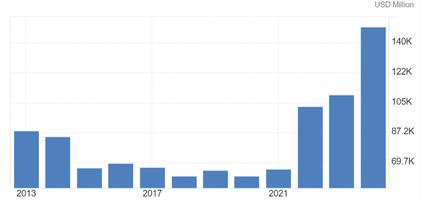

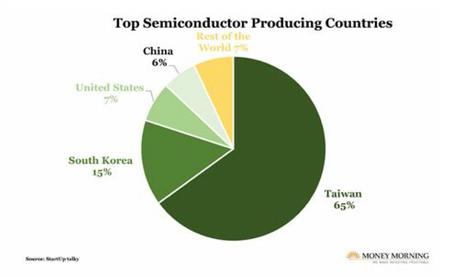

TSMC and the Importance of Semiconductor Production - Riley A (39)

The Rising Global Influence of BRICSGeorge S (40)

Newspaper Edited by: Eben A, Louis S, Joanna C, Samuel A

Thank you to all those who submitted articles for this newsletter

Equality and Allocation in Economics - Eben A (2)

Investment, Utility and the Luka Trade - Danis B (3)

The Financial Sector: The Engine of the UK EconomyKobi A (5)

Why Interest Rates Still Control the Markets - Henry L (6)

Did the UK do enough to recover from the UK Financial Crisis - Harry T (7)

Lasting Legacy of the Financial Crisis on The UK - Mr. Hughes (8)

Impacts of the Farming Tax - Jack B (10)

Why is there Poverty: Joanna C (11)

Labour Shortages: Why are there Labour Shortages in major sectors - Ed P.C (12)

The Swedish Economy - Oscar L (13)

Impacts of International Sanctions on Rhodesia - Matt B (15)

Consequences of Two Palaces Conflict in Eastern WuZhan T (16)

BY EBEN A.

If I told you that the top 1% of earners were wealthier than up to 95% of the world’s population, would you believe me? According to research done by OXFAM, an international charity organisation, this is in fact true.

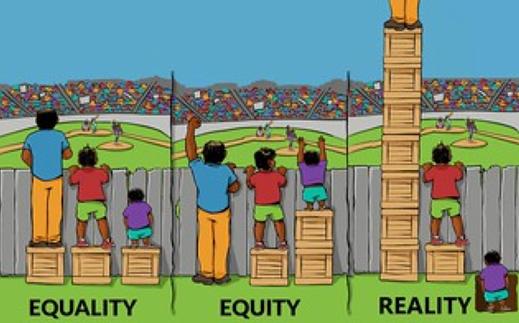

Take a second to look at the image above. This image is a visual metaphor for society: being able to see the game represents thriving in society, the better view you have, the more prosperous you are. In this analogy, height represents a person’s opportunity and how capable they are, with the shortest people being those in poverty and without basic necessities, whilst the tallest are the rich, born into affluence with a wealth of opportunities and connections at their predisposal. As you can see on the right of the image: the reality, as previously discussed, is that the richest few people utilise their advantage to take a largely disproportionate amount of wealth compared to the majority of the population.

How does this happen? This level of inequality mainly exists due to centralisation of power both globally and in markets. For example, on an international scale, European colonialism profited by using the natural resources of their colonies to fuel their own growth whilst investing disproportionate amounts in return. As a result, Europe is now, overall, significantly richer than the parts of Africa or Asia it colonised. Similarly, in a more market-based example, successful and wealthy businessmen like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk employ thousands of workers in their corporations. Even though most workers in these companies likely work just as hard as their superiors. The owners and those working higher up take a disproportionate amount of the profits due to being in charge of the company. Earning more money allows people like Musk and Bezos to expand their businesses, buy lots of houses and supercars, and invest in the economy; this ends up making them much wealthier and creating great inequality.

On top of this, sometimes the most vulnerable in society can be exploited, and actually have their wealth taken away from them in

order to expand the wealth of the richest. Two good examples of such practices are slavery and child labour, where both groups are worked harder than most, but are paid little in return due to being a more vulnerable group in society.

Is Equality the Answer? – The simplest solution to this might, at a glance, seem to be ensuring all people share resources and wealth equally, to promote fairness. This is the sort of system advocated for by Karl Marx, an economist who suggested all labour should be state run to ensure resources are fairly and equally allocated between workers. However, there are some issues with this line of thinking; firstly, say you were a medicinal scientist who had spent years qualifying for a degree and hours learning biochemistry and maths; and you were told you’d be earning the same amount as a cashier who has done next to no training compared to you. Would you still want to be a doctor? One of the issues of equality through sharing of assets and wealth is that the incentive of acquiring wealth and luxury via skilled jobs is removed. As a result of this, it leads to a lower skilled, less productive workforce. Such a workforce is therefore less motivated to enter into, and work effectively in high skill jobs. Another issue with state issued wealth and assets it that it creates a similar problem that Marx tries to avoid by getting rid of wealth accolated by those who are powerful within markets. It creates a state which has complete control over who gets what, and inevitably this results in government corruption which hordes wealth and thus doesn’t solve the problem.

What is Equity, could it work? – Equity is when resources are allocated based on the requirements of those who need them; where the most vulnerable and those with less opportunity are given more resources to bring them on par with wider society. Additionally, the wealthiest give up resources to those who need them so that all can receive what they need. One example of equity are rich countries donating to poorer ones to help them grow to improve their living standards and reduce inequality. Another is charities donating to those in need in society, allowing them to access helpful resources they otherwise wouldn’t receive without aid. The biggest issue with equity is that to ensure the poorest in society get what they need, the richest in society will inevitably have to give up wealth and assets. Therefore, equity it isn’t achievable without the richest endorsing the idea, which is difficult when the idea involves them losing large amounts of wealth. Equity also shares some of the same issues equality has, where incentives to work aren’t as great since equity requires donations from the most well off highly skilled workers.

In Summary – Trying to find the best way to solve the global imbalance in wealth is not easy and possibly explains why the world continues to be such an unequal place.

BY DANIS B.

On the morning of February 2nd 2025, it was nearly impossible to avoid the biggest news in sports: the Dallas Mavericks of the National Basketball Association had just traded Luka Dončić for the Los Angeles Lakers' Anthony Davis. The Lakers have overwhelmingly been deemed the winners of the trade, having won the generational 25-year old talent and 5-time NBA all-star from Slovenia. Described as 'one of the most astounding moves in NBA history', many still theorize about the true nature of the deal, with conclusions ranging from plausible to conspiratorial. However, we can perhaps better understand the reasoning behind the trade using expected utility theory, a tool in microeconomics.

Expected utility theory concerns the subjective gain of consuming or obtaining a good with an uncertain outcome. Unlike, say, buying a Tshirt, where the consumer knows prior to checkout more or less exactly what deal they are getting, when e.g. buying assets like stocks, shareholders cannot know for sure if they will go up or down in value. Simplification is standard fare for ease of economic analysis. Let's simplify and say that you, the manager of a major basketball franchise, have a player who currently averages 28.6 points per game (PPG), and you could trade them for someone with the odds of 1/3 of averaging 31 PPG in your team, and a chance of 2/3 of averaging 16 PPG in your team. On average, from such a newcomer you could expect an average per-game score of 1/3 x 31 + 2/3 x 16, which works out to 21 points per game—not bad by any means, but still lower than the 'guaranteed' statistics of your current star player. When only looking at the expected value of the two players' statistics, you might then decide to keep your current roster.

However, let's consider the utility you get from each scenario. In economics, utility is simply the subjective satisfaction a consumer gets from obtaining or consuming something. Many people gain utility from watching NBA All-Star games, but they may enjoy Ultimate Frisbee to a lesser degree, so that sport may, by comparison, give them less utility. What contributes to the utility you would get from a player with a certain average PPG may include the likelihood of securing brand deals for your team, the salary that player may be entitled to, likelihood of that player leading your team to the finals and getting your team higher publicity, etc. It is worth noting that, in this model, you would actually be in the position of a firm, which aims to maximise profits, however the utility analogy can easily carry over to e.g. expectations of higher profit margins.

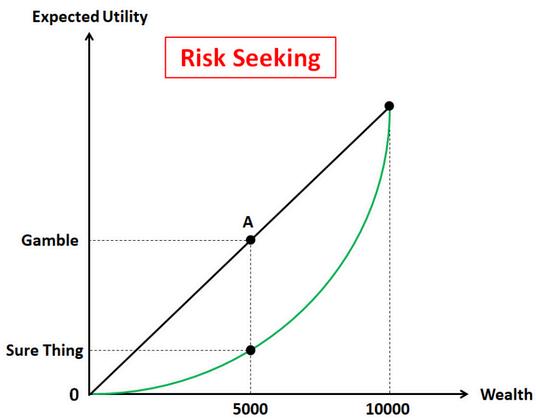

In the highly competitive world of basketball, it may be the case that each additional unit increase in a player's statistics increases your 'utility' gained from having that player by an even greater amount. In economics terms, your marginal utility may be increasing.

Let's assume you get 100 utility points from a player a 28 6 PPG average, 400 utility points from a player having an average of 31 PPG (usually near the very top of NBA performance), and 70 utility points from a player averaging 16 PPG Using the same odds as before, the newcomers expected utility, on average, would be 1/3 x 400 + 2/3 x 70 utility points, which equals 180 utility points; that's higher than keeping your current 28.6 point scorer, so to maximise your expected utility (or really, profits in the firm's case), you may opt for the riskier deal

In this example, there were only two possible outcomes for the newcomer's statistics, but in real life, they could possibly take any value, each with some non-zero probability It is possible to determine what the 'rational' choice would be in any kind of lottery situation, using a concept called a utility function Economists assume everyone has such a function; any consumer knows how much utility they would get from obtaining or consuming X units of a good It turns out that the shape of the function determines whether a consumer is more prone to safer or riskier decisions. If their utility function is hillshaped (they experience diminishing marginal utility), then they would be said to be risk-averse, or less likely to buy assets whose expected average value in the future is lower than the price one would currently have to pay for them On the other hand, a U-shaped utility function (increasing marginal utility) means a consumer or investor is risk-loving

This theory, while potentially a reasonable way of modelling the motivation behind athlete trades, is mostly used for explaining decision-making in private investment into financial assets, taking out health insurance, or gambling

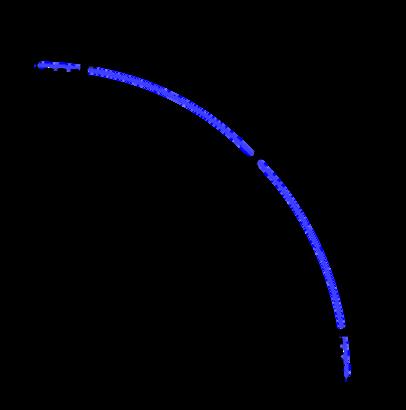

EXPECTED UTILITY GRAPH FOR A RISK-LOVING INVESTOR THE CURVED LINE REPRESENTS THE UTILITY GAINED FROM HAVING X UNITS OF WEALTH WITH CERTAINTY, WHEREAS THE STRAIGHT LINE REPRESENTS THE UTILITY FROM HAVING AN EXPECTED AMOUNT OF X UNITS IN A LOTTERY SCENARIO.

It is possible that the Mavericks' utility function is valleyshaped, meaning they are more willing to make risky trades The team has also reportedly had concerns over Dončić's conditioning, as well as his eligibility for a super-max contract extension (an additional percentage of the cap salary paid only to the league's highest performers Dončić was making $43,031,940 in 2024). However, it's worth remembering Davis' status as one of the best defensive players in the league 'I believe that getting an All-Defensive centre and an All-NBA player with a defensive mindset gives us a better chance We’re built to win now and in the future ' said Nico Harrison, president of basketball operations for the Mavericks. Maybe the opportunity cost of keeping Dončić into his late career, given his recent injuries, dietary struggles, and high salary entitlement, was greater for Dallas than the opportunity cost of gaining a strong defensive player in Davis, despite his 32 years of age (although carritics note that the latter has also had a history of injuries, and that NBA players typically reach their athletic zenith in their late 20s, meaning Dončić could likely provide more utility in the future)

The decision has seemingly been backfiring on the Mavericks' end, with Davis and star teammate Kyrie Irving both going through injuries, and the franchise failing to qualify for the playoffs (the Lakers have also recently entered the offseason following a 96-103 loss to the Minnesota Timberwolves).

Most commentators agree that, despite Davis' strength on the court, the Slovenian phenom was simply too special of an opportunity for Dallas to trade away, and quite likely other factors apart from pure expectations about player statistics and profits impacted the decision

In the end, we may never find out the true motivation behind the shocking trade, and only time will tell what the future holds for both the Lakers and the Mavericks. In the modern NBA, perhaps one should expect the unexpected sooner than expect utility.

BY KOBI A.

The UK’s financial sector is often described as the backbone of the economy, and for many good reasons. From the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf to the regional banks in Manchester and Edinburgh, financial services not only support businesses and people, but also create the wider economy through trade, investment, and innovation. However, the sector does introduce an element of controversy, it’s huge influence invites questions about fairness, stability, and the future of a rapidly evolving industry.

Financial services contribute over £170 billion every year to the UK economy which makes up about 8-10% of its GDP. The sector employs over 1 million people across the country, with about half of those jobs located outside London. This shows us that finance in the UK is not just a City of London phenomenon!

The UK’s financial centre is one of the most developed and globalised. Financial institutions such as the London Stock Exchange (LSE), the Bank of England (BoE), and the Lloyd’s Insurance Market form the core of complex structures like retail banks, investment firms, insurance companies and accounting providers. As we can see, this sector plays a crucial role in providing capital to business, managing risk, and allowing day-today transactions.

For years, London was the financial bridge between Europe and the rest of the world. But since Brexit, the UK has lost some of its access to EU financial markets. Nowadays, we see that some international banks and investment firms have shifted parts of their operations to places such as Paris or Frankfurt.

One of finance’s most important jobs is to help money flow to where it’s needed the most. That could be a green energy project, a startup, building new tech, or even a government scheme to build roads or hospitals. Without that flow of capital, the economy would slow down – or stop.

But finance also carries risks. The 2008 global financial crisis started because of poor regulation and excessive risk-taking in banking. It led to a deep recession, massive government bailouts, and long-lasting effects on public services and inequality. It was a harsh reminder that when finance fails, everyone pays.

Since that crisis, the UK has worked hard to strengthen its financial systems. Institutions like the Bank of England now play a bigger role in overseeing banks and financial firms. The aim is simple: keep the system stable, protect consumers, and stop things from spinning out of control. But regulation is a tricky balance. Too little, we risk another crisis. Too much, we could stifle innovation and shrink the economy.

In recent years, finance has been evolving. There’s growing pressure for banks and investment firms to not just focus on profits, but also the environment, social impact, and ethical governance. Investors increasingly want their money to support climate-friendly or socially responsible businesses.

And with digital technology changing how we bank, invest, and manage money, the sector is becoming more accessible but also more complex. This can create exciting opportunities for new ideas, but also raises important questions about data privacy, cyber security, and fairness.

Finance isn’t just about spreadsheets and interest rates. It’s about people, choices and values. It’s the mechanism behind how we fund public services, support innovation and fight against long term challenges such as climate change.

BY HENRY L

A single decision by the central bank can cause markets to rise or fall. Even a small interest rate hike can cause large changes in investment, currency values and confidence in the economy. While some argue central banks now have more modern methods such as quantitative easing and forward guidance, changes in interest rates still have the strongest and most immediate effect on financial markets.

Interest rates are the cost of borrowing money, central banks like the Bank of England or the Federal Reserve set a base rate that affects loans, mortgages and savings.

When interest rates rise, a country’s currency will often become stronger. As higher rates attract foreign investors looking for better returns. For example, if the Bank of England raises rates and the European central bank does not, the pound will rise against the euro.

From 2021 to 2024, the Bank of England raised interest rates in an effort to reduce high inflation. Prices had been rising rapidly following the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by factors such as energy shortages and the war in Ukraine. The goal was to make borrowing more expensive, which would encourage people and businesses to spend less and help slow down the economy.

Bond prices fall when interest rates rise, as newer bonds offer better returns, so older bonds become less attractive and lose value.

As a result, bond yields (return an investor earns from a bond) go up. Investors will watch central bank announcements closely and react before or as soon as the rate change happens. Higher interest rates will usually cause share prices to fall, due to companies facing higher borrowing costs and lower consumer demand, affecting profits. Investors will use interest rates to judge the value of a company’s potential future earnings.

“Bank of England raised the base rate from 0.1% in 2021 to over 5% by 2024”

The FTSE 100 dropped by over 5 percent in 2022, with property companies hit hard. UK government bond yields rose from around 1 percent to over 4 percent, as investors wanted better returns. The pound rose to about 1.30 dollars in 2023, after falling below 1.10 in 2022. Mortgage rates more than doubled, with average two-year fixed deals going above 6 percent.

BY HARRY T.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis originated in the United States due to excessive subprime mortgage lending (high-risk loans to people with poor credit history). These were repackaged into complex financial productions and sold globally. In 2007-08, a growing number of borrowers defaulted, house prices collapsed, and banks holding these risky assets collapsed. The UK had a financialised economy, with banking contributing 9% to GDP in 2007. Major institutions such as RBS, HBOS and northern rock were heavily effected due to these bad assets.

Immediately after the crisis under the labour government, between 2008-10, the UK government spent £137bn rescuing banks. This was essential in preventing a domino collapse of the financial system and posing system risk. In 2009, quantitative easing was launched by the Bank of England. They created £375bn initially (later £895bn total by 2021) to inject money into the economy, this increased liquidity in the financial system, encouraging borrowing and investment. Base interest rates were slashed from 5.75% to 0.5% by March 2009 to reduce debt costs and increase disposable income and consumption. VAT was cut from 17.5% to 15% and a temporary increase government spending (before austerity began).

However, it could be argued that the government stopped recovery efforts too early, reducing aggregate demand when the private sector was still fragile.

In the long term, there were significant economic consequences. One of these was real wage stagnations, real wages are wages adjusted for inflation. If real wages stagnate,people purchasing power doesn’t grow even if nominal wages rise. After the crisis, real wages in the UK fell and only returned to 2008 levels around 2023. This was due to weak productivity growth which meant output per worker didn’t justify higher wages, public sector pay freezes (under austerity) and rising costs such as rent or utilities that squeezed disposable income. This led to living standards falling, household debts and rising costs without income growth, this therefore caused consumer confidence and spending to be held back in the long term.

In 2010, the national debt and fiscal deficit had grown sharply due to emergency spending and falling tax revenues. The coalition government aimed to reduce the deficit by introducing signifncant spending cuts, known as austerity. This included welfare reforms (benefit caps etc), public sector pay freezes and jobs cuts, decreased local authority funding, infrastructure spending postponed or cancelled and increased rates of tax. This was to restore market confidence and keep government borrowing costs low, preventing debt crisis’ like Greece or Italy.

Another economic consequence was the impact on public services and the welfare state, cuts from austerity affected local councils, NHS and social care, rising crime and court backlogs. This resulted in public services struggling to meet rising demand, which was further exposed during COVID-19. Lastly, along with many other consequences, there was a shift towards a more fragile economy. This was due to post crisis growth heavily relying on rising house prices, household borrowing and consumer spending all driven by lower interest rates. This model made the UK vulnerable to interest rate hikes and external pressure such as Brexit or COVID-19.

Compared to other countries such as the US and Germany who aided stronger rebound, had greater and longer lasting fiscal stimulus and heavily invested into productivity, the UK seemed to not do enough. They over relied on monetary policy and pulled back on fiscal stimulus too early. This led to growth and living standards falling behind other G7 economies through the 2010s.

BY MR. HUGHES, HEAD OF ECONOMICS

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) is widely regarded as one of the most significant economic shocks in modern history. While its effects rippled across the globe, causing recessions in most major economies, the United Kingdom found itself particularly vulnerable to its aftershocks. More than fifteen years on, the scars of the crisis continue to shape the UK’s economic landscape, from sluggish productivity growth to strained public services, persistent trade deficits and stagnating living standards.

Overexposed: The UK's Reliance on Financial Services

In the years leading up to the crisis, the UK economy had become increasingly dependent on its booming financial services sector. Dubbed "The City," London's status as a global financial hub brought considerable wealth and employment, helping to fuel the UK’s impressive GDP growth in the years leading up to the crisis. However, this overreliance also left the UK dangerously exposed to external financial shocks.

When the crisis hit, triggered by the collapse of major financial institutions in the US and a global freeze in credit markets, the consequences were severe. The so-called "credit crunch" meant banks stopped lending to each other, to businesses and to consumers. Business investment and consumer confidence fell sharply, and financial institutions across the globe had to be bailed out to avoid total collapse. The financial services sector, previously a powerful engine of UK economic growth, contracted sharply, dragging the rest of the economy down with it.

In hindsight, had the UK had a more diversified economy, with less reliance on financial services with perhaps more of an industrial base, there is a reasonable chance that the UK’s exposure to the financial crisis would have been less severe.

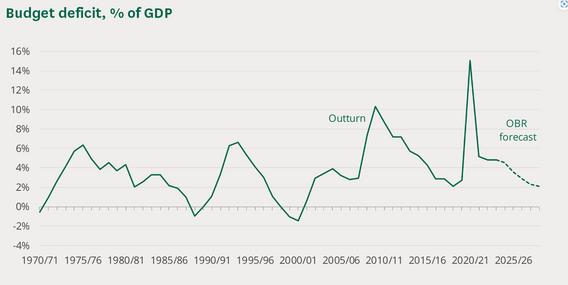

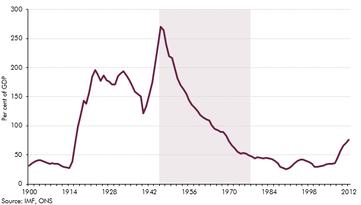

By 2010, the UK faced a daunting budget deficit, exceeding 10% of GDP (see figure 1). In response, the newly formed Conservative-led coalition government introduced a programme of fiscal austerity, aimed at restoring investor confidence, preserving the UK’s credit rating, and reducing the national debt.

Source: Commons Parliamentary Library

A crucial feature of this fiscal tightening was its composition: around 80% of the deficit reduction came from spending cuts, with only 20% from tax rises. This decision had far-reaching consequences. Cuts were made to welfare, local government budgets, and key public services. Investment in infrastructure, such as roads, rail, and schools, was scaled back. Public sector pay freezes were also introduced. In the short term, these measures did help to gradually reduce the size of the UK budget deficit, but they also, arguably, slowed economic recovery. In the long term, this austerity meant lower investment in both human capital (through education, health, and welfare) and physical capital (through infrastructure), thereby slowing growth of the productive capacity of the UK economy in the years that followed.

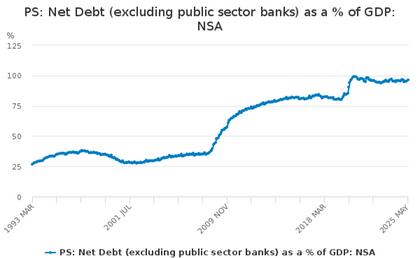

Source: ONS

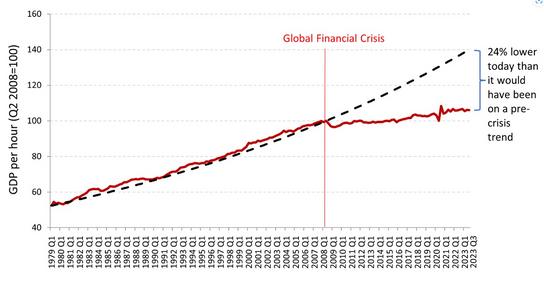

The Productivity Puzzle

One of the most damaging long-term effects of the GFC and the subsequent policy response has been the UK’s persistent productivity problems. Since 2008, productivity growth has been far slower than in previous decades, and slower than in many of the UK’s international peers. On average, growth of output per worker, or productivity growth, has fallen from about 2.5% growth per annum in the years before the crisis to 0.5% today. This weak growth of productivity post-financial crisis is one of the main reasons that UK households have seen their real incomes and living standards stagnate and is arguably one of the most significant lasting legacies of the GFC for the UK economy.

Linked with this, investment, both public and private, has remained subdued. Businesses, wary of economic uncertainty, have been reluctant to invest in new technologies or staff training, further worsening the UK’s productivity woes. Meanwhile, austerity-era cuts hampered the government’s ability to invest in infrastructure and innovation. This has eroded the UK’s trend rate of growth, its underlying capacity to expand the economy over time.

Restoring productivity to pre-crisis levels, via increased public and private sector investment, is the key to returning to higher rates of growth and improved living standards for UK citizens.

Weaker productivity growth post GFC has led to another worrying trend: declining international competitiveness. UK exports have struggled to compete on price and quality with goods and services from more productive economies. As a result, the UK continues to run a persistent trade and current account deficit, importing more than it exports year after year. This means that, even as the global economy has recovered, the UK has struggled to keep pace.

Beyond its economic consequences, the Global Financial Crisis also had a profound social and political impact in the UK. The years following the crisis were marked by weak wage growth, stagnating living standards, and growing regional inequalities. For many, the squeeze on household finances was compounded by visible cuts to public services, libraries were closed, bus routes axed, and local authorities faced severe funding shortfalls. At the same time, the government spent billions, arguably necessarily, rescuing failing banks that were widely viewed as responsible for the crisis in the first place. This fuelled a deep sense of resentment and alienation, particularly in areas already experiencing economic hardship. These feelings helped lay the foundations for the backlash that culminated in the 2016 Brexit vote. In many "Leave" voting regions, the referendum became a way to express dissatisfaction with the economic status quo, a sense of being left behind, and mistrust in political and financial institutions.

3: GDP per hour

Source: LSE

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis was more than a temporary shock; it fundamentally altered the trajectory of the UK economy. Overexposure to financial services made the UK uniquely vulnerable to a crisis in global credit markets. The austerity that followed, while politically and fiscally expedient at the time, had unintended consequences, such as undermining investment, weakening productivity growth, and damaging the UK’s long-term economic potential.

As policymakers grapple with the economic challenges of today, from regional inequalities; to the potential impacts of AI, or the challenges associated with climate transition, the legacy of the GFC remains a cautionary tale. The choices made in the aftermath of a crisis can shape a country’s fortunes for decades to come.

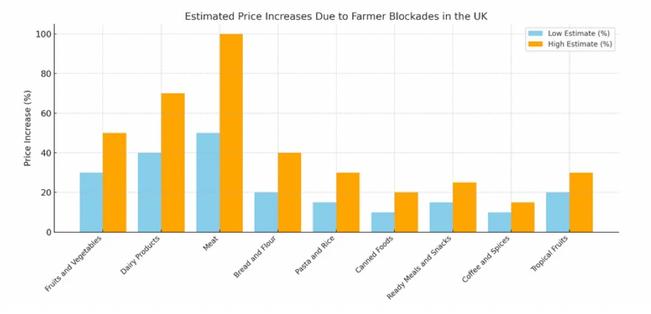

BY JACK B.

What is the Farming Inheritance tax? Inheritance tax is levied on the assets of someone who has died. In the case of farmers this is often major technology such as tractors and farmland/ livestock. Agricultural property relief is a type of tax relief which reduces the amount of tax that farmers have to pay when farmland is passed to the next generation.

What was announced in the most recent budget and how does it effect Farmers?

From April 2026 the full 100% tax relief will be restricted to the first £1 million of agricultural property. Above this amount farmers will have access to a reduced rate of 20% rather than 40% which it was before. The main problem farmers are facing is the fact that this tax after £1 million is hard to obtain. As the tax is on assets, farmers are being forced to sell valuable land and agricultural machinery to afford this. It then becomes harder for that family to make a living, often leading to creating lower living standards.

How does this affect the wider population?

If more farmland is having to be sold to pay for the tax it could create major food insecurity.

The decrease in domestic production may increase the UK’s current reliance on imported foods (46%) to meet demand. This is an issue as fluctuating currency exchange rates, especially postbrexit, and Geopolitical instability (such as the Ukraine war) are causing imported food to cost more . Therefore leading to a decrease in AD, worsening of the trade budget and overall decreasing economic growth.

Furthermore, the price of UK food could sky rocket. Due to the inheritance tax many farms are either majorly reducing production or abandoning all together. With less domestic food produced, supply shifts left and decreases. Whilst demand remains relatively stable. As a result causing prices to increase for UK-grown products as Firms aim to maximise utility through profit.

This rations many low income households out the market and therefore decreases living standards, as they can’t afford the necessities such as bread. Further creating a rift between the high and low income households. As shown by the Office of National Statistics the bottom 10% of households spend 14-15% income on food whilst the richest 10% spend 7% of income on food.

BY JOANNA C

Poverty is defined as the condition of not having enough income or resources to meet basic needs such as food, shelter, healthcare, and education. There are two types of poverty, relative poverty and absolute poverty. Relative poverty refers to a condition where household income is a certain percentage below median income. For example, the threshold for relative poverty could be set at 50% of median incomes (or 60%).

Absolute poverty refers toa condition where household income is below a necessary level to maintain basic living standards (food, shelter, housing). This condition makes it possible to compare between different countries and over time. Over 1 billion people in the world suffer from extreme poverty, while 72 out of 81 people, including children, live in some form of poverty.

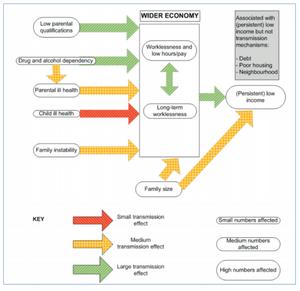

There are many different causes of why people find themselves living in poverty. From long-term unemployment to a lack of social mobility, each can play a part in the appearance of poverty in the economy.

All you need to know about Economics

4. Economic inactivity: Related to unemployment is economic inactivity. People may be not classed as unemployed (not actively seeking work) but at the same time, they are not in employment. This could be due to long-term sickness, disability, discouragement from the labour market, forced to take early retirement, or single parents caring for their children. Inactivity means a largesource of income is government benefits. In recent years, benefits for working-age people have been index-linked – this means benefits have generally risen faster than average incomes.

1. Wage inequality: Approximately one in nine workers receive the national minimum wage in the UK. Many workers on this wage rate will receive less than 60% of median earnings. In recent years, there has been a growth in low-paid work, especially for low-skilled workers.

2. Job insecurity and part-time work: Increased labour market flexibility has led to an increase in zero hour contracts and part-time work. This can adversely affect workers' income because they have no guarantee of wages. A short number of hours can lead to individuals falling behind with debt repayments and rent, which compounds their situation.

3. Unemployment: Unemployment is the biggest cause of poverty in the UK. People are either relying on benefits or suffering from structural unemployment due to a lack of skills. 65% of the poor are not in work For someone who is unemployed long-term, returning to the competitive workforce can become even more difficult as they might find multiple problems. For example, long term unemployment can affect a person's mental health, confidence, and self-esteem. It can also lead to debt, an unhealthy diet, and poor physical health.

5. Old age:People over 65 have traditionally been more at risk of relative poverty, as pension incomes are significantly less than average incomes. However, in recent years, pension poverty has seen the sharpest fall due to a rise in the real value of the state pension. Housing costs also tend to reduce inequality for pensioners as they are more likely to own a house than the younger generation.

6. Regressive Taxes:Tax changes in the 1980s and 1990s have put a higher burden of tax on the poor. There has been a shift in taxes from progressive income tax to regressive, indirect taxes, therefore causing an increase in inequality. For example, the top marginal rate of income tax fell from 83% in 1979 to 40% in 1989. The basic rate has come down from 33% to 22%. However, the overall tax burden has remained unchanged because the government has increased VAT and indirect taxes on alcohol and petrol and extending VAT to domestic fuel. These taxes take a higher % from those on low incomes.

7. Inheritance: This allows wealth inequality to be passed on and magnified from generation to generation.

There is no simple answer to this question as poverty remains a persistent issue that has not been solved for decades. For centuries, governments, organisations and people have tried to stop the spread and cycle of poverty. Government bodies such as the United Nations have provided financial support which they hope will result in more education, healthcare and job opportunities for the next generation. In the UK, schemes like food assistance have been introduced to ensure families can at least meet their basic needs, such as food and shelter.

BY EDWARD P.C.

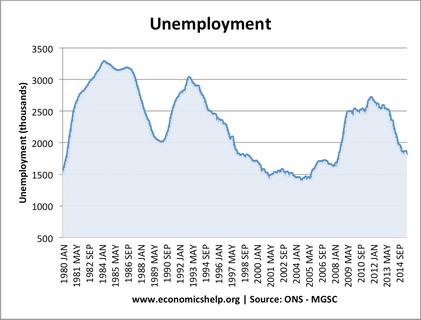

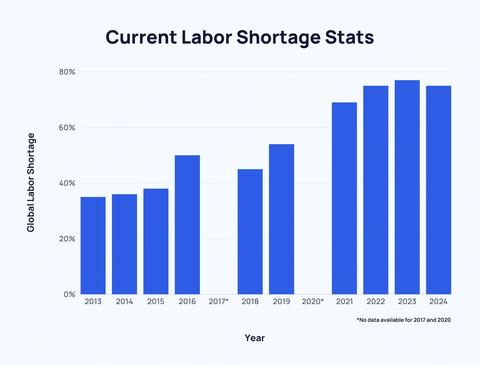

Over the last years, countries like the UK have seen growing labour shortages over key sectors like healthcare, agriculture, and construction This shortage occurs when the demand for labour exceeds the labour available. It is seen that labour shortages can have a wide variety of effects on output and long-term economic growth. This article will explore the economic effects and what reactions the UK has had to this

The key cause for labour shortage in the UK can be due to a variety of factors including both physical and social factors. One key factor when relating to the physical factors is the fact that many sectors face poor conditions, long hours and low pay relative to the work being put in For example, construction workers have physically high demanding jobs where they work long hours throughout the week and many have pay that does not accurately pay for the effort they are giving For example, some construction workers work between 40 and 44 hours a week and only get paid around £812 weekly

So, keeping in mind the physical demand needed, this can be seen as not worth it Consequently, this is why we are seeing shrinkages in these key areas where the workers are leaving their jobs due to a lack of pay Construction is one of the main ways that an economy can expand with them building new housing or new offices, all bringing new opportunities into the UK With relatively low wages, workers leave these industries causing shortages in sectors that we rely on. Not only this but childcare workers are also seen to be near to minimum wage despite the demanding nature of the job. With the heavily demanding work, and the low pay, social care workers feel obliged to leave jobs here creating shortages

Another reason for labour shortages can be seen to be from the Labour government and their post-Brexit reforms to migration policy decreasing the number of immigrants being allowed into the UK for work purposes. These migrants used to fill roles in sectors that needed filling meaning that there are huge shortages where these cannot be catered for anymore.

These shortages in key areas can have large consequences affecting more than just the labour market. These labour shortages can reduce the productive potential in the economy. If construction firms cannot hire enough groundsman and drivers then housing and groundwork projects may be delayed or cancelled due to a lack or labour. This can slow economic growth in the economy. With labour shrinkages it can also cause short run aggregate supply to fall. This is because for firms to counter the lack of labour, they may advertise for higher pay to increase the incentive for them to work for them. This can cause higher labour costs which can mean that this will cause production costs to increase, discouraging aggregate supply and reducing rates of economic growth in the economy.

Government will likely strive to fix this labour shortage by implementing different policies to fix the issue. They are obliged to do this because they want what is best for the country and to boost the potential of the economy. One way that governments could do this is with more spending on education and training. With this, the economy can both gain a more educated workforce and reduce the unfilled job vacancies in certain industries. Another policy that the government could implement in the economy is to relax immigration rules. This is because sectors can gain a boost in the labor supply allowing vacancies to be filled to alleviate labour shortages.

BY OSCAR L.

Sweden is widely known for its high living standards and having one of the highest gross national incomes per capita in the world. However, this is combated by also having some of the highest tax rates in the world. Although most of the Swedish businesses are within the private sector and operate in a competitive mixed economy, the government still plays a large role in determining how the economy operates; with around 60% of the gross domestic product going through the public sector, mainly through services like health care and education.

The Swedish economy is heavily dependent on international tradeespecially exports- which make up roughly a third of it’s GDP. This can be shown to be potentially risky, due to the fact that the economy can become quickly vulnerable to changes in global markets; which would result in Swedish exports having to change to keep up with other producers. In order to lower the risk of this, in the early 1990s, Sweden attempted to try and tie their currency -the krona- to the European currency unit, however they eventually abandoned this in 1992. Despite joining the European union in 1995, Sweden chose to not use the euro, instead it operates through the Riksbank -which is the countries national bank-, which sets the countries monetary policy and helps to maintain price stability.

A major challenge for Sweden has been maintaining competitiveness with other economies, especially due to the relatively high production costs. Consequentially, many large Swedish companies have invested more in production abroad than at home, with some now employing more people internationally than within Sweden.

Sweden's agriculture can be shown to be limited by the geography and climate, with less than 10% of the land used for farming. Most of the farmland is located in the south, where they grow crops such as wheat and barley, however some farming does occur up north, where the focus is more centred upon the farming of hay and potatoes, although this is limited due to the harsher weather conditions.

Animal farming is more important than crop production, with dairy farming being widely practised by Swedish farmers, with large pig and poultry farms existing in the south. Swedish farms are believed to be some of the most productive in the world, though there are concerns about environmental damage in which they have causes, which has led to a reduced use of fertilisers.

With a large extent of Swedish land being covered by forestland, forests are some of Sweden’s most key natural resources Approximately half the forestland is privately owned, with the rest being split between public and company ownership Throughout history, forestry was believed to be seasonal work for farmers as a result of the different seasons, but currently due to technological advancements it is used as a year-round industry; with most farms also including timberland. Swedish practices sustainable forestry, ensuring that more trees are planted than cut down During the 1990s, Sweden introduced a reform in order to help better protect the nations biodiversity, which included mapping important woodland areas

Fishing, although widely practised, is only a small part of the economy and has recently declined due to newly introduced international agreements that have limited access to the previous, traditional fishing zones in the North Sea Gothenburg is the main fishing port and seafood market, attracting vast amounts of people within the industry

Manufacturing is considered to be the backbone of Sweden’s exports, although more people work in the public sector than in private industry Forest based products such as paper and timber are important exports, which are supported by the strong transport system of roads and railways, which help people and firms to easily transport across themselves or goods around the country Over recent decades the paper and pulp industries have become based along the southern coast, contrasting to initially being located near rivers - due to the easier access arrangements- before the transport advancements.

The metal industry – which mainly includes iron and steel- is centred in the Bergslagen region, spreading across the central parts of the country Major steelworks also operate in Oxelösund and Luleå As a result of Sweden being a mixed economy, roughly 90% of Sweden’s industrial production comes from privately owned companies. The engineering sector, especially automotive and aerospace, has the largest contribution to the countries industrial output, making up around half Car manufacturers, such as Volvo and Saab, played a huge role in expanding the variety of what the nation produced, although Saab went bankrupt in 2011; with their assets being later bought by NEVS, a company which mainly focuses on electric vehicles

Other industries include electronics in Stockholm and Västerås, plastics and small metal products in the south, as well as a growing pharmaceutical and biotech sector near research universities

Finance and Trade

Sweden's financial system is mainly based around a few large commercial banks, with the Riksbank issuing currency, however there are still several savings, and foreign banks operating in the country

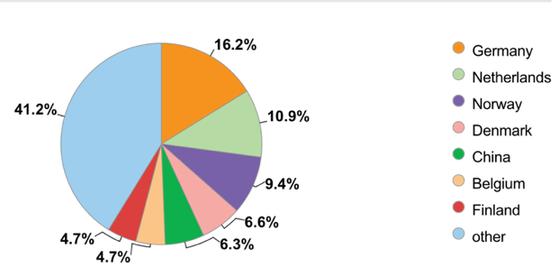

Trade is vital to Sweden, with exports making up roughly a third of its GDP. Over time the focus has shifted from raw materials like timber and steel to high-value products such as cars and electronics Key trading partners include Germany, the UK, Norway, Finland, and Denmark.

Sweden’s imports have a larger variety They can be shown to mainly import engineering goods, computers, food, chemicals, and textiles Germany is the largest source of these imports, followed by several nearby European countries. The distribution of Sweden’s imports are shown below:

BY MATTHEW B.

In 1965, the white-minority government of Southern Rhodesia, led by Ian Smith, issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain. This bold move, intended to preserve white minority rule, drew swift condemnation from the international community and led to comprehensive economic sanctions. This article explores how these sanctions affected Rhodesia's economy, focusing on trade, industrial adaptation, inflation, and long-term development consequences.

Following the UDI, the United Kingdom and later the United Nations imposed a series of economic sanctions against Rhodesia. These included trade embargoes, the freezing of financial assets, and bans on oil and arms exports. The aim was to pressure the regime into majority rule without direct military intervention.

Sanctions severely restricted Rhodesia's ability to trade with most of the international community. Key exports such as tobacco, minerals, and agricultural products lost access to major markets. In response, Rhodesia increasingly relied on trade with sympathetic or economically interdependent countries like South Africa and Portugal (through its colonies like Mozambique). However, this trade was often covert, costly, and inefficient.

One notable effect of sanctions was Rhodesia's push for industrial self-sufficiency. The government invested heavily in import substitution industrialization (ISI), attempting to produce previously imported goods domestically. While this led to some innovation and industrial growth, the isolation stifled technological advancement and access to high-quality inputs.

Sanctions also triggered monetary instability. With limited access to foreign currency reserves and financial markets, Rhodesia experienced growing inflation and challenges in maintaining a stable Rhodesian dollar. The government often resorted to printing money to cover deficits, further exacerbating inflationary pressures.

All you need to know about Economics

To circumvent sanctions, Rhodesia developed a network of front companies and smuggling operations. These illicit channels provided some economic relief but also entrenched corruption and weakened institutional transparency. The black market became a critical feature of the wartime and post-UDI economy.

While the white minority continued to enjoy a relatively high standard of living due to economic prioritisation, the African majority bore the brunt of the sanctions’ effects. Limited employment opportunities, rising prices, and poor access to services worsened inequality and fuelled resentment that contributed to the liberation struggle.

International sanctions against Rhodesia during the UDI period had profound effects on its economy. While the regime managed to adapt in some ways, the overall impact was economic stagnation, inflation, and growing inequality. The sanctions played a crucial role in weakening the Smith government’s long-term viability and underscored the challenges of economic isolation in a globalized world. Ultimately, they contributed to the fall of white minority rule and the emergence of an independent Zimbabwe in 1980.

BY ZHAN T.

In 182 A.D., the August Emperor of Eastern Wu (吴) passed away after suffering from wind-evoked headache. His eldest son, Sun Deng, was a virtuous and talented young man, Quan established him as the crown prince, which means if there’s no accident, Sun Deng will be the next emperor of Eastern Wu. However, in 241 A.D., Sun Deng was seriously ill and passed away at the age of 33. Quan was greatly affected by Sun Deng’s death; he had to establish his third son Sun He as the crown prince. But in 242 A.D., Quan’s fourth son was unsatisfied with this decision, so they had a political argument about the position of the crown prince.

Due to the special geographical position of the Eastern Wu, a big percentage of trade was reliant on water transportation. Since Sun Ba took political control around Wu Chang (the middle reaches of the Yangtze River) and Sun He’s scope of political activities mainly revolved around Jian Ye (the capital of Eastern Wu), the water transportation and trade along the Yangtze River was badly affected due to their political argument.

The efficiency and business confidence fell due to more time spent checking the goods transported and paying the tax. As a result, the cost of transportation and the time taken increased, reducing aggregate supply, causing cost-push inflation. This increaseed the price level and reduced real GDP. Also, as the traders found it difficult to trade in Wu kingdom, they turned to Shu kingdom on the west side and Wei kingdom on the north side. So, the number of business and markets in Wu fell. The enterprises lost their business confidence to invest, which led to a fall in economic growth.

Also, the conflict between Sun He and Sun Ba had formed a situation of opposition and affected the court of Wu, as many talented government officials had been demoted or killed. This kind of situation led to a great loss of labour force and brain

drain. As a result, the efficiency of government fell, which meant the government was not able to allocate resources effectively, causing market failure. At the same time, there were cases of political corruption and embezzlement, resulting in a loss of government revenue.

Another effect is that due to the political instability caused by the argument between the two princes, the government’s policies often changed, leading to economic uncertainty, so the merchants migrated to the other two kingdoms (Wei and Shu) to trade. This caused the population of Eastern Wu to decrease and the national output to fall.

In conclusion, the conflict between two palaces was a political disaster in Eastern Wu. It likely decreased the length of time of Wu as a kingdom, but due to its special position, Wu was still the last kingdom to be ruined. However, neither Sun He nor Sun Ba became the future emperor. Sun He had lost his position of crown prince and Sun Ba was killed. After this, Sun Quan, let Sun Liang (his youngest son) become the crown prince and future emperor, which led to even more chaos in the future. At end of his life, Sun Quan regretted and wanted to ask the people to bring Sun He back, but it was too late.

The Housing Crisis: Why are Homes so expensiveJessica F (18)

Is the UK’s housing market broken? - Rehan M (19)

Opportunity Cost of Everyday Decisions - Francesca H (20)

Irrational Behaviour - Aliya W (21)

The Cost of Learning: How VAT is reshaping EducationLouis S (22)

Should University be Free? The Economics behind Student Debt - Aastha G (23)

Econometric Model Looking into the peer effect in education - Mr. Jones (24)

BY JESSICA F.

In recent years, house prices have risen drastically in many parts of the world such as London, New York and San Francisco. This has meant that it has become a lot harder for younger people to enter the property ladder and even renting a property has become much more of a challenge for many people. Throughout this article, I will explore the reasoning as to why this is happening.

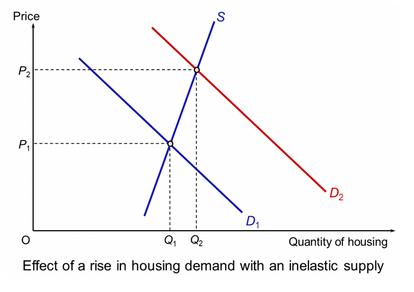

Effectively, when demand increases at a faster rate than supply, this causes prices to increase. This is because consumers bid up the price when there is not enough supply in an economy.

Factors which are affecting the demand of housing include population growth and increased immigration, as it is going to cause a higher demand for housing as more people require these resources. However, there are finite resources in an economy, and it is how these are allocated, which determines the price. Similarly, property is increasingly being used as an investment purpose, rather than just to live in. This further increases the demand for housing and causes the prices to be pushed up further. In terms of the supply side, there are clear barriers which are restricting the increase in supply such as planning restrictions and availability of land. In places like London, strict zoning laws limit how and where houses can be built, slowing the increase in supply.

This diagram shows the vast increase in price level from a shift from P1 to P2, whilst the quantity of housing increases by a smaller amount. This is because the supply of housing is relatively inelastic and so producers struggle to increase supply in the short term due to one or more factors being fixed.

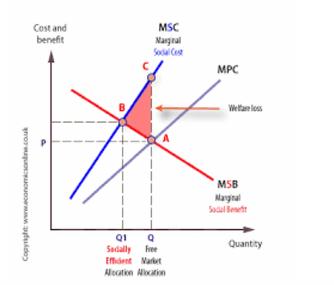

The housing market also suffers from market failure. Housing is a basic need and so when the market fails to provide this it results in the production of negative externalities such as increased homelessness, overcrowding and social inequality. Similarly, information gaps can also be a problem. This is where the producer may have more information than the consumer. This could include living conditions, or the financial risk involved, resulting in poor decision making. The increase in housing costs is also causing a larger gap to form between those who can afford housing and those who cannot. In many cities, wealth is now being concentrated among property owners whilst many renters are facing the increasing costs of living.

So, what are the government doing about this? Firstly, many governments have implemented rent controls. This limits the amount of rent landlords can charge. This aims to keep housing costs affordable to ensure that less people are rationed out of the market. However, implementing this policy may also reduce the landlords desire to rent, hence decreasing the supply of housing further. In addition, the government can also put in place subsidies which can help low-income families afford rent. However, each of these solutions comes with trade-offs. For example, while subsidies can help people in the short term, they may increase demand and push up prices unless supply is also increased.

The housing crisis is a complex problem caused by imbalances in supply and demand, worsened by market failures and inadequate policy responses. Solving it will require a combination of approaches—encouraging more homebuilding, reforming planning regulations, and ensuring that housing markets work for everyone, not just investors and high earners.

BY REHAN M.

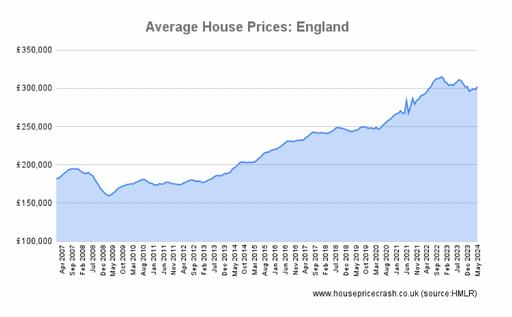

For many people in the UK, especially young adults, buying a home feels impossible. Prices have increased massively in recent decades, exceeding wages. Rents are high, social housing is scarce, and even finding a decent flat can be a struggle. But behind the personal frustration is a much bigger economic issue.

The UK has not built enough homes to match its growing population. Planning rules, land costs, and slow construction all mean a limited supply. At the same time, demand stays high from buyers, landlords, and investors. The result? Prices keep rising.

At its core, the problem is simple: there are not enough homes for the number of people who need them. For decades, the UK has failed to build enough new housing, especially in the places where demand is highest for example, London, the Southeast, and growing regional cities like Bristol and Manchester. At the same time, more people want to live alone, or in smaller households. The result is rising demand, with very limited supply. That combination always leads to higher prices.

It’s not that the UK doesn’t have space — it’s that planning laws, local opposition, and construction costs make it slow and difficult to build. Even when houses do get built, they’re often too expensive or aimed at wealthy buyers rather than those on average incomes.

When housing costs rise faster than wages as they have been for years the effects are felt across the whole economy. People spend more of their income on rent or mortgages, leaving less for essential goods and services to spend on. Renters face more insecurity, while young adults delay moving out or starting families. Employers struggle to hire in expensive areas, and rising demand for housing support adds pressure on public finances. In short, the housing crisis doesn’t just affect individuals it holds back economic growth and social stability.

Fixing the housing crisis isn’t simple, but this issue can be fixed with a few approaches. One of the biggest priorities is building more homes — not just luxury flats, but affordable and social housing that people on average incomes can actually afford. That means changing the planning system to speed up development, especially in high-demand areas. At the same time, the government could do more to support first-time buyers, whether through fairer mortgage options or shared ownership schemes. Some also argue that the tax system should be changed, making it less attractive to own second or empty homes, which currently reduces housing availability without meeting real need. Finally, investing more evenly across the country in jobs, transport, and infrastructure could ease pressure on the most overcrowded cities by encouraging people to live and work elsewhere.

BY FRANCESCA H.

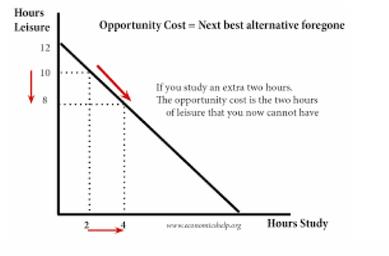

Opportunity cost is defined as the value of the next best alternative foregone. Opportunity cost is used in scenarios where the economic agent e.g consumer or producer has to make a decision regarding the allocation of resources, or the consumption of one product over another.

For example, in the school environment, you as students are faced with the opportunity cost when last minute revising for end of year exams. If you have two hard exams on one day and the night before you haven’t revised for either biology or chemistry you are faced with a decision where an opportunity cost will be involved. By allocating all of your time to revising biology the opportunity cost is doing well in your chemistry exam.

Now, lets take this one step further. You are hungry whilst slaving away at your desk and really fancy a pizza. Do you make one yourself or order one from dominoes. A rational consumer always acts in a way which maximises their utility and this can be understood as maximising the happiness gained from the consumption of a product. Of course you choose the dominoes pizza. The opportunity cost is the money spent on the pizza, this money could’ve been spent on chemistry tuition fees.

Intelligent people make decisions based on opportunity costs.

Charlie Munger

Markets are lethal, if only because of ignoring externalities, the impacts of their transactions on the environment.

Noam Chomsky

Not only during an economic transaction is there an opportunity cost, there is also spill over effects onto third parties which are known as externalities.

The negative externality in consumption of fast food and dominoes pizza is a series of health issues which may lead to seeking help from the NHS and therefore clogging up by the health service and potentially rendering the NHS less operable. Additionally, other members of society will have less access to the NHS and this may lead to a decrease in health and then living standards.

BY ALIYA W.

Economics, as a social science, often needs to be deduced by imitating human behavior. However, in real life, not everyone is rational. We are often influenced by the outside world, personal preferences, and are often misjudged and make irrational behaviors subconsciously.

For example: Choose one of the two tables from the images below:

Typically, people will often choose the one on the right.

However, they are the same.

The subjective feeling of the naked eye makes us blindly confident, and the limited time also limits our accuracy. We cannot use a ruler to accurately measure and make judgments. Just like when you are waiting in line to check out at a supermarket and choosing chewing gum at the counter, the urging of the customer behind you prevents you from choosing the most cost-effective chewing gum. After you have bought this brand of chewing gum, if its taste is not so bad that it is unacceptable, you will most likely choose the same brand of chewing gum next time you check out due to habit, even if it may not be the best tasting or most cost-effective one. At this point, you have embarked on the path of irrational behaviour.

Irrational behaviors are constantly happening in our lives, such as choosing delicious, puff pastry food over healthier fruits, or choosing procrastination over completing homework on time. This irrational behavior will not only interfere with personal efficiency and health, but collective irrationality may also have a wider impact. For example, the proliferation of plastic products will lead to environmental pollution, the increased demand for tobacco and alcohol will lead to frequent drunken incidents, and the medical system will be overloaded.

In order to regulate this phenomenon and increase market efficiency, economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein proposed

the concept of choice design in their book Nudge, which aims to guide people to make better decisions without depriving them of their freedom.

This concept needs to have three elements: low cost (no coercion or monetary inducement) no prohibition of any options (free choice is left to be directed in a more favorable direction (e.g. health, finances, happiness).

For example, the government can stipulate that the area where cigarettes are sold in supermarkets should not be in conspicuous places. This can reduce the potential users of smoking, such as minors driven by curiosity. Similarly, it can also stipulate that vegetables and fruits should be placed in the most conspicuous areas to attract people to buy healthy food and reduce the workload of public hospitals.

The concept of nudge has actually been used in daily life. For example, the British pension system requires active opt-out rather than active opt-in. After the implementation of this proposal, the participation rate jumped from about 61% to more than 90%. It led the people to increase long-term savings, provided stable long-term funds for the capital market, enhanced personal retirement security, and reduced the pressure on social security in the future.

In addition to mild interventions such as nudge, there is also direct government intervention, such as bans and restrictions, such as prohibiting smoking in indoor public places, restricting tobacco advertising, forcing eggplant boxes to print warning pictures, or forcing food labels to indicate ingredients, allergens, and nutrition tables; prohibiting the use of trans fats. Consumers can more easily assess the risks of products and reduce irrational choices caused by the outside world. Examples of direct government intervention include raising taxes and providing subsidies to affect the production cost of the product, stimulating businesses to increase or reduce the number of such products, and changing market development trends.

It is reasonable for humans to have irrational behavior. However, in order to ensure the effectiveness of the market and society, economists and governments need to constantly intervene in people's choices to maximise their benefits.

What we need to do is to realise the shortcomings of judgment and make changes to cater to policies and stick to good goals.

BY LOUIS S

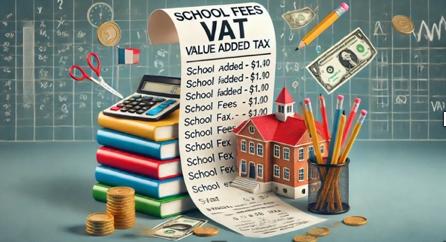

In the 2024 autumn budget, the UK government announced the implementation of VAT on private schools of 20%. The UK government claims ‘The revenue raised by this measure will be used to fund the 94% of children who attend state schools’ (uk government website).

They suggest the effect of the tax will lead to the redistribution of wealth from higher income households- ones who send their children to private schools- to lower/average income households-who send their children to state schools. In principle this would be very effective, higher income households are mostly able to afford the cost increase, and the tax revenue generated will ideally be reinvested into the state provided education system on teachers and equipment etc. Allowing 94% of young people to have a better education allowing them to access higher paying jobs and increase socio-economic mobility within the country the state will provide a better education This is the desired effect of the VAT; to reduce inequality, raise tax revenue and increase socioeconomic mobility.

However, this could have the exact opposite effect, potentially worsening equality. Some lower/average income households send their children to a private school to allow the best chance for them to be successful and achieve the best education they can, so they can work in higher paying jobs This is the demographic who are most likely to be affected by the VAT, rationing the lower income households out of the market for private education Making private education more exclusive and removing the ability for the lower income households to have the same opportunities as higher income households. Potentially worsening inequality and social-economic mobility.

The VAT aims to improve state education but risks rationing lower income households out of private education, making it more exclusive This could reduce opportunities for those seeking better education and higher-paying jobs, worsening inequality and limiting social-economic mobility. While the VAT may raise state education quality, it may also harm lower income families relying on private education for life-changing opportunities.

BY AASTHA G.

In recent years, the debate over whether university education should be free has become a prominent issue in economic and political circles. Proponents argue that free education could enhance equality and promote long-term economic growth. Opponents, however, contend that it might increase government debt and decrease efficiency.

In countries such as the UK and the US, students face high tuition fees for university education. In the UK, students can borrow up to £9,535 annually for tuition fees, in addition to maintenance loans that assist with living expenses. These loans often accumulate into substantial debts— frequently exceeding £40,000 by graduation. Although repayment begins only when a graduate earns above a specified income level, the debt can persist for many years.

From an economic standpoint, this is viewed as an investment in human capital, suggesting that education boosts a worker's productivity and earning potential. However, the escalating costs of tuition raise questions about whether the returns on this investment are consistently worthwhile, particularly when wages fail to keep pace.

Education doesn’t just benefit the individual, it also benefits society. Highly educated workers contribute more to the economy, are less likely to be unemployed, and tend to be healthier. These are positive externalities. Since the free market tends to underprovide goods with positive externalities, economists argue there’s a role for government intervention.

Making university free would cost the government billions. This money could instead be spent on healthcare, schools, or infrastructure. Economists always ask what the next best alternative is: this is the concept of opportunity cost. Critics argue that university graduates usually go on to earn more, so it’s fair that they repay some or all their education costs. Germany offers free university education, and student debt levels are very low. The government funds this through higher taxes, but university access is more equal.

A more educated workforce can lead to higher productivity and innovation. If more people can access higher education without financial stress, it could lead to greater long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) growth. Free university could reduce inequality and support long-term growth, but it also involves high costs and potential inefficiencies. The decision depends on how society balances equity, efficiency, and the best use of scarce educational resources. As student debt continues to grow, and the demand for skilled workers rises, this debate will remain at the center of economic policy for many years to come.

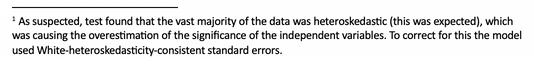

BY MR JONES, TEACHER OF ECONOMICS

When I was in Year 13, I had my very own economic problem to solve. My thrash metal band, The Phantom Lords, had been signed to a record label and did I pursue my dream of being a rock star or accept the offer I had received to attend university? The choice was not easy, but thankfully there is some overlap between the world of Smith and Keynes with that of Metallica and Megadeth. They both love a subgenre (and nouns beginning with M).

In Year 12, economic students are introduced to the two big ones, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics. Then throughout the A-level we dive into more sub-topics of the discipline, from Development Economics and Game Theory to Financial Economics and Theory of the Firm. In this article I would like to introduce two more – Theoretical Economics and Empirical Economics.

Theoretical economics focuses on developing abstract ideas and principles to explain economic behaviour, while empirical economics tests these theories using real-world data and observations that economists call ‘models’. The bridge between these two is a mathematical tool unique to economics that we call ‘econometrics’, that allows us to statistical methods to test out economic theory.

This article is going to be using Empirical Economics to form a hypothesis and then test this through real-world data. The area that I have chosen is looking into which factors influence achievement at GCSE, especially the effects of friends (peers) and family.

My initial hypothesis is that those students with more academically achieving peers and from more financially affluent backgrounds will achieve higher GCSE results.

Although I will be focusing more on the method and reasons behind choosing the variables that I have, I believe that this is a vital area to investigate as we enter the age of AI. There is a huge debate amongst educationalists about the future role of schools, and are they even needed? If we can provide that schools are not just a place to gather information but that it is also the interaction between students that is vital this may change how classrooms evolve.

Take my data, we're off to never-never land…

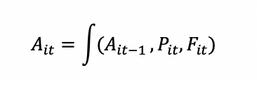

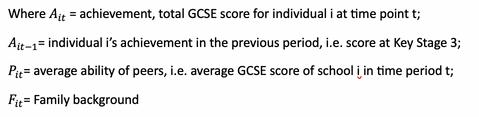

The empirical model used will be based on this liner education production function:

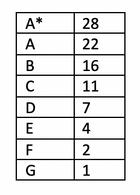

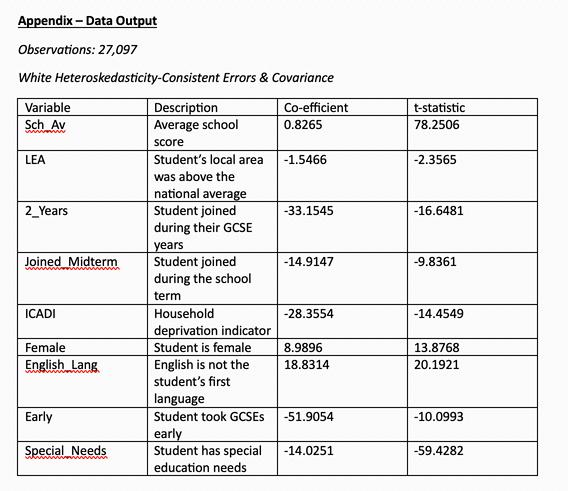

Achievement for the current period () will be measured by looking at each student’s individual cumulative GCSE score. The data set I am using pre-dates the current grading system of 1-9, so to allow the data to be mathematically analysed, each grade is assigned a number of points representative of the level of difficulty required to gain each grade, as shown below:

The difference between the grades increases progressively, to reflect the increase in the marginal level of difficulty between each grade as it takes more effort for a student to increase their grade from an A to an A* than from a G to an F. All the points are aggregated to give the student’s final score. For instance, a student with one ‘A’, five ‘B’s and four ‘C’s would have a final score of 146 (28+80+44).

In an ideal model, each student’s GCSE score would be compared against the aggregate score of their specific classmates. This would give a more precise measure of the effect that the interacting between students has on their achievements. However, most students move from class to class to the various subject combinations available throughout the curriculum. In addition, students mix with each other in the playground, sports field, bus home etc. and not just in the classroom.

All these interactions will influence the mental attitude taken towards study. For instance, if the bus ride home is spent discussing current affairs rather than watching Mr Beast videos, then the former are likely to perform batter in their exams. Hence, although it may initially seem that taking an aggregate of the students’ scores may lead to a bias in the results, it does allow us to take into account for the peer group effects outside of the classroom. However, the results are still likely to be upwardly biased because the peer variable is likely to not only capture the effect of peers but also reflect school effects such as teacher quality, class size, etc.

The model will also be considering the region that the student lives in, and whether it is a relatively successful region or not, to attain the general ability of peers outside of school. This is measured by a dummy variable that takes the percent of passes in English and Maths from the local area and comparing it against the national average. If the area fell below the national average, then the region will be considered relatively poor and given a value of zero.

Interaction with school peers is not the only factor that will determine how well a student performs at school. Possibly the most significant influence in a person’s life is their family, whom they are likely to spend the majority of time with outside of school.

Whether English is the student’s primary language will also be considered as well as if the student has any special needs.

It will also be considered whether a student has moved school over their GCSE years, as they are likely to be hindered by the experience. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the process of moving house takes a fair amount of the student’s time, an opportunity cost for studying. Second, adapting to a new school environment is quite daunting for most students. This is likely to reduce their productivity.

Finally, we shall be using a dummy variable indicating the sex of the student at birth. Traditionally, girls outperform boys at GCSEs. Economic data shows that girls are better at analytical work, while boys perform better at numeracy (although this is less apparent at all girls schools – maybe an area worth exploring another time). As GCSE exams have shortened over the years, it may be that this gap has narrowed, although this is unlikely.

Unfortunately, this mode will be omitting the variable as it introduces many statistical problems within the linear model. The main statistical issue brought about by this variable is that it introduces another time period into the data. Hence, due to unexplained/untraceable factors (such as teacher quality and student teacher ratios across the two years), it is likely to suffer from impure serial correlation, where misspecification in the variable causes an upward bias in the significance of the model.

could be entered into the model by using panel data analysis, but unfortunately, I lack the time to produce models of that complexity.