For thousands of years people have lived in and traveled around New Castle because of the Delaware River. New Castle is located within the homeland of the Lenni Lenape people which has the Delaware River at its center. Since the Delaware teemed with wildlife, and provided an efficient means of transportation, Europeans were attracted to this area in the 17th century to establish colonies for harvesting resources, establishing settlements and engaging in trade.

As European settlement spread, travel became necessary to maintain trade and relations. Travel in the 17th century was difficult, slow and often dangerous – even over short distances. Improvements in travel infrastructure, including roads and bridges, took time, as did improvements in modes of transportation and the establishment of businesses, like inns, which served travelers.

With New Castle’s central, accessible location between the East Coast’s major urban areas, including New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington D.C., it naturally developed as a hub of transportation during the 18th and early 19th centuries. In addition, New Castle was the county seat of New Castle County and the location of the courts, both of which brought Delawareans into New Castle to handle business and personal affairs. For all these reasons, travelers often found themselves in New Castle – sometimes for a few hours, sometimes for a few days. So, what was it like to travel in and around New Castle two hundred or more years ago?

“ThePerfectionofTravelling” EarlyAmericanTravel 1651-1851

December 31, 1839.

The modern fashion in all things is “to go ahead,” push on, keep moving, and the faster the better—never mind comfort or security or pleasure. Dash away, and annihilate space by springing at a single jump, as it were, from town to town, whether you have pressing business or not.

“How do you mean to travel?” asks Neighbor John. “By railroad, to be sure, which is the only way of travelling now; and if one could stop when one wanted, and if one were not locked up in a box with fifty or sixty tobacco-chewers; and the engine and fire did not burn holes in one's clothes; and the springs and hinges didn't make such a racket; and the smell of the smoke, of the oil and of the chimney did not poison one; and if one could see the country, and were not in danger of being blown sky high or knocked off the rails,—it would be the perfection of travelling.”

After all, the old-fashioned way of five or six miles an hour, with one’s own horses and carriage, with liberty to dine decently in a decent inn and be master of one's movements, with the delight of seeing the country and getting along rationally, is the mode to which I cling, and which will be adopted again by the generations of after times.

Samuel Breck, 1839

As you may imagine, the travel experience for New Castle residents and visitors, as well as all travelers in colonial America and the early United States, was dramatically different than what we experience in the United States today.

Today, we enjoy a massive, interconnected travel system of roads and highways, rail systems, airlines, cruise ships, hotels and restaurants. We have access to public transportation like buses and commuter rail service. We can get door to door service easily by calling a cab or requesting an Uber. We think nothing of getting in our own car and driving ourselves to a destination several hundred miles away for a weekend pleasure trip or planning all the details of an international vacation in advance without ever leaving our living room. We have paved biking and walking trails that permit easy movement when traveling under our own power. When traveling, we expect to easily change from one mode of transportation to another with as little inconvenience to ourselves as possible. We expect that we will have many choices of excellent accommodations, access to properly prepared food that meets any dietary requirements or preferences we have, and excellent customer service from businesses that we patronize. We expect that we will be treated fairly and equitably by service providers, and that we will be able to travel safely as we move around the country and the world.

None of these expectations or experiences were realistic two hundred years ago, and three hundred years ago most were downright impossible.

“ThePerfectionofTravelling” EarlyAmericanTravel 1651-1851

WhyTravel?

People in colonial America and the early United State traveled for many reasons, most of which are the same reasons that we travel today:

For Pleasure

People took trips to see new places, learn new things, and to remove themselves from their day-to-day concerns. Though pleasure travel was not common in the 18th century, after 1820 it quickly became a favorite activity especially among affluent people.

For Business

People traveled to their county seat to conduct legal business when courts were in session. Some operated itinerant businesses like portrait painters, dancing masters, tutors, peddler, tinkers or other skilled trades people.

To Maintain Relations

People traveled to visit friends and relatives that lived in other communities. Particularly among the upper classes, families from different colonies or states often intermarried to increase wealth and maintain or increase power in political and social circles.

To Improve Health

Physicians in the 19th century began prescribing trips to take advantage of a change in climate, a change in scenery or to make use of mineral springs. New York and New England spas and springs became popular destinations for people searching for relief of various ailments. Brandywine Springs, with its hotel and resort near Marshallton, Delaware was a favorite destination for Philadelphians in the early 19th century. The waters of the Chalybeate spring located there were believed to have medicinal and restorative powers.

To Immigrate or Migrate

People looked to new lands to take advantage of new economic opportunity, escape religious persecution, or start a new life.

Due to Forced Immigration

Examples of forced immigration included the slave trade and transportation. Almost 400,000 Africans were forcibly shipped to North America as part of the slave trade. People convicted of capital crimes in the British Isles were offered the option of “transportation” which entailed having their death sentence commuted in exchange for serving a 7-to-14-year period as an indentured servant in America.

Due to War

The struggle for the future of North America often erupted in military violence and war. Soldiers in militias and armies and sailors in navies traveled extensively. As a result, women too traveled as great distances as camp followers to a traveling army. People of all types sometimes sought to escape to safety when their home was threatened.

Mrs. Biddle and her daughters are now with us. They came here last Thursday on their way to Philadelphia. Mrs. Biddle’s health is in a very bad state and finding the inefficiency of medicinal prescriptions she wishes to try a change of air.

Letter to G. Read Senior in New York from Mary Read in New Castle, June 7, 1789

Letter to Bedford Read in Carlisle, PA from Mary Read in New Castle, June 9, 1814

My health requires change of air. I believe I shall visit Carlisle and the York Springs.

The threatening aspect of war and our exposure on the sea, the Atlantic Coast to its ravages, has induced Mrs. Read to come to a determination of our removing her residence in March next into the interior of the country and she has given preference to Carlisle. I feel anxious to have provided for her genteel and agreeable lodgings. Isabella, Mary and a servant boy will be the persons whom she will have with her. May I presume to solicit you to inquire if such lodgings could be procured in March next and at what rate; a mineral spring in the neighborhood of Carlisle is with Mrs. Read a considerable inducement to fixing on that place.

Letter to James Hamilton in Carlisle, PA from G. Read Jr., November 8, 1814

December 31, 1839.

The modern fashion in all things is “to go ahead,” push on, keep moving, and the faster the better

never mind comfort or security or pleasure. Dash away, and annihilate space by springing at a single jump, as it were, from town to town, whether you have pressing business or not.

“How do you mean to travel?” asks Neighbor John. “By railroad, to be sure, which is the only way of travelling now; and if one could stop when one wanted, and if one were not locked up in a box with fifty or sixty tobacco-chewers; and the engine and fire did not burn holes in one's clothes; and the springs and hinges didn't make such a racket; and the smell of the smoke, of the oil and of the chimney did not poison one; and if one could see the country, and were not in danger of being blown sky high or knocked off the rails,—it would be the perfection of travelling.”

After all, the old-fashioned way of five or six miles an hour, with one’s own horses and carriage, with liberty to dine decently in a decent inn and be master of one's movements, with the delight of seeing the country and getting along rationally, is the mode to which I cling, and which will be adopted again by the generations of after times.

Samuel Breck,

—

1839

TravelInEarlyAmerica

When Europeans first arrived in North America roads did not exist Travel was slow, laborious, and often dangerous. Most people walked from place to place using existing paths or making their own. Water travel was easier, especially

over longer distances, with canoes and rafts being commonly employed for crossing or traveling along rivers.

Local travel, from outlying farms to nearby towns, was relatively easy and might be done on a weekly basis For people living in areas that were very rural, or on the frontier, these trips may only occur monthly – or even less frequently Up to the 19th century, many rural Americans did not think much about a 3-6 mile walk for shopping, socializing or to attend religious services.

By the 18th century, the abundance of horses made travel easier with people with riding the horse itself or as a passenger in a horse-drawn vehicle. Between 1790 and 1840 the number of horses in America grew faster than the population, until there was one horse for every 4-5 people Distribution of horses varied with families in urban areas typically owning no horses while rural Americans owned at least one

Road conditions varied greatly with little directional guidance available from road signs or maps. Travelers relied on advice from people who had traveled the area previously, and frequently on the advice and guidance of strangers that they met on their journey – with varying levels of success.

Travel by land had several drawbacks – sparsely available accommodations whether at a tavern or a welcoming farmstead may require camping along a trail, a lack of adequate bridges or ferries often left travelers fording rivers and streams on their own, and roads and pathways that were unfamiliar to anyone but residents of the local area often meant wandering through unfamiliar territory for hours, if not days.

By the 19th century, people in America traveled with much more frequency that their contemporaries in Europe In 1828, a Boston newspaper writer commented that in America “the whole population is in motion, whereas, in old countries, there are millions who have never been beyond the sound of the parish bell.”

…Mons. Moll, who had to go to one of his plantations lying on the road leading to Kasparus's house [Bohemia Manor, Maryland], requested us to accompany him…We accordingly started, Mr. Moll riding on horseback and we following him on foot, carrying our travelling sacks, but sometimes exchanging with him, and thus also riding a part of the way. This plantation of his is situated about fifteen miles from the Sandhook [ New Castle]. It was about ten o'clock in the morning when we took leave of our friends and left. We passed through a tolerably good country, but the soil was a little sandy, and it was three o'clock in the afternoon when we reached the plantation. The dwellings were very badly appointed, especially for such a man as Mons. Moll. There was no place to retire to, nor a chair to sit on, or a bed to sleep on. After we had supped, Mr. Moll, who would be civil, wished us to lie upon a bed that was there, and he would lie upon a bench, which we declined; and as this continued some length of time I lay down on a heap of maize, and he and my comrade afterwards did the same. This was very uncomfortable and chilly, but it had to go so.

Jasper Danckaerts, 1679

30

th, Thursday [October].

It was about noon when we were set across the creek in a canoe. We proceeded thence a small distance over land to a place where the fortress of Christine had stood…We went into a house here belonging to some Swedes, with whom Ephraim had some business. We were then taken over Christine Creek in a canoe, and landed at the spot where Stuyvesant threw up his battery to attack the fort… Ephraim obtained a horse…and rode on towards Santhoek, now Newcastle, and we followed him on foot, his servant leading the way.

Jasper Danckaerts, 1679

24 th, Friday [October].

19 th, Tuesday.

Coming to the large creek, which is properly called Christina Kill, we found Mr. Moll had not correctly calculated the tide, for he supposed it would be low water or thereabouts, whereas the water was so high that it was not advisable to ride through it with horses, and we would have to wait until the water had fallen sufficiently for that purpose. While we were waiting, and it began to get towards evening, an Indian came on the opposite side of the creek, who knew Mr. Moll, and lived near there at that time, and had perhaps heard us speak. He said that we should have to wait there too long; but if we would ride a little lower down, he had a canoe in which he would carry us over, and we might swim the horses across. We rode there at once, and found him and his canoe. We unsaddled the horses, and he swam them over one by one, being in the canoe and holding them by the bridle. When we were over, we quickly saddled them and rode them as fast as they could run, so that they might not be cold and benumbed…We reached Newcastle happily about eight o'clock in the evening, much rejoiced, and thanking Mr. Moll.

Jasper Danckaerts, 1679

[Leaving Bohemia Manor in Maryland] I took horses and guide and went to New Castle, that night, 'tis accounted 30 miles, I met with Mr. Williams the Collector deliver'd him his Letter, and discours'd him about the trade Betwixt the head of the Bey and that Town for tobacco, he told me there had been formerly much tobacco brought over to that Town, but now not so much, he had lately seised some tobacco that had been brought, but by others I perceived It is frequently carried over to that Town

July 14.

Cuthbert Potter, 1690

Monday, April 11th, 1774. Fine pleasant weather. In the afternoon saw Bardsey Island on the Welsh Coast and Carmarthen Bay. Yesterday it blew fresh and I was very sick, but to-day I am something better. Sleeping in a Hammock is very agreeable, though very different from a bed on shore.

Thursday, April 14th, 1774. Find I am much deceived—very sick all day.

Friday, April 15th, 1774. A fair wind and pleasant. Drank a Quart of sea water which operated both ways very plentifully and did me great service.

Cresswell, 1774

[Sailing

from England to North America]

Nicholas

Roads

The availability and quality of roads and bridges in the colonial and early national periods varied widely. Transportation along the eastern seaboard in colonial America initially followed trails that were established by indigenous people. Eventually these trails were widened to accommodate wagons and stagecoaches. The first post road, which connected Boston and New York, was originally known as the Pequot Trail. The road would eventually be extended further south, ultimately reaching all the way to Charleston, South Carolina –over 1,300 miles This road was called “The King’s Highway” after Charles II of England who ordered its construction

Most early road surfaces were simply dirt. Many were naturally rocky and uneven, and others, including the King’s Highway, were blocked by stumps leftover from clearing the road or became filled with ruts made by carriages pulled along wet or muddy road surfaces. A fallen tree or flooded area could render a road impassable for extended periods of time.

Toll roads, or turnpikes, became popular in the 1730s Shares in turnpike companies were sold to finance their construction, and the quality of the road was good. They promoted improvements in road surfaces including the use of gravel, stone, wooden planks and eventually macadam.

The Great Wagon Road evolved into the primary road permitting the settlement of the American South. Starting in the port city of Philadelphia, in 1754, it first connected the city with Lancaster and York, PA From there the road was lengthened, turned southwest, eventually reaching all the way to Georgia by 1775 The first major effort to build west through the Appalachians occurs in 1775 when Daniel Boone is given the task of constructing the Wilderness Road that led from Virginia to Kentucky. The Wilderness Road connected to the Great Wagon Road expanding the ability of people to move into the interior of the continent.

The roads in this state [Maryland] are worse than in any one in the Union; indeed so very bad are they, that on going from Elkton to the Susquehannah ferry, the driver frequently had to call to the passengers in the stage, to lean out of the carriage first at one side, then at the other, to prevent it from oversetting in the deep ruts with which the road abounds: “Now, gentlemen, to the right;” upon which the passengers all stretched their bodies half-way out of the carriage to balance it on that side: “Now, gentlemen, to the left,” and so on. This was found absolutely necessary at least a dozen times in half the number of miles.

Isaac Weld, 1795-1797

We arrived here safely Sunday afternoon. Tho our journey was much retarded by the badness of the roads occasioned by the late rains – in hopes of a change of weather we remained this day in Lancaster and if it is more favorable tomorrow we proceed to Harrisburgh.

Letter to G. Read Jr. in New Castle from Mary Read in Lancaster, PA, September 26, 1792

Roads

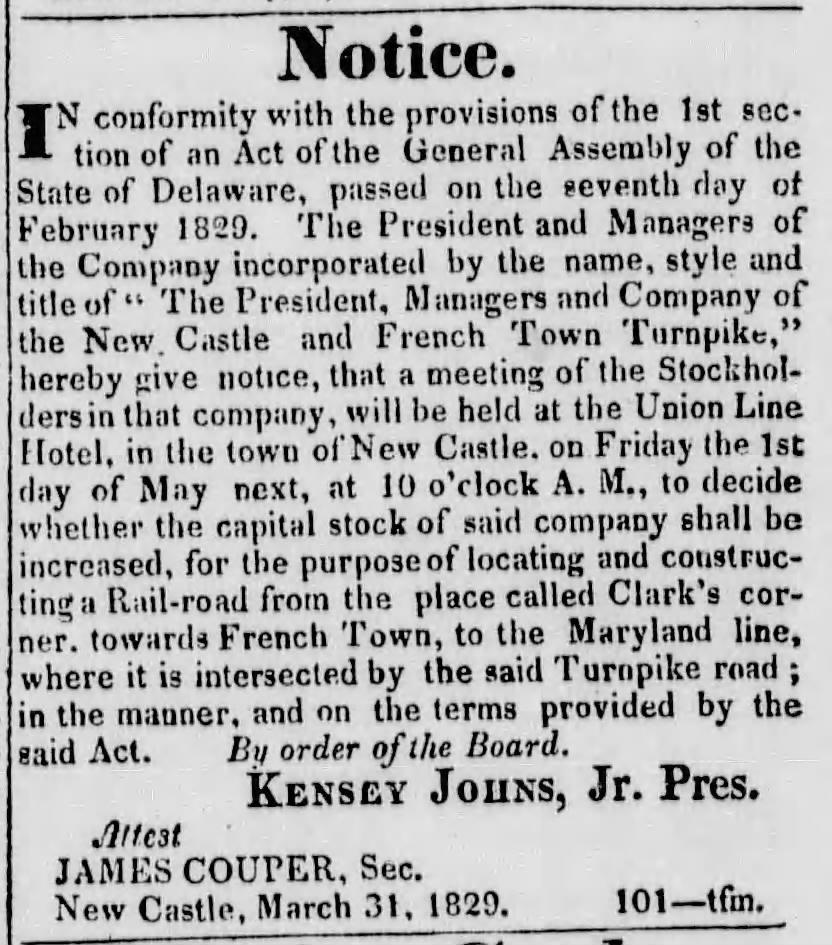

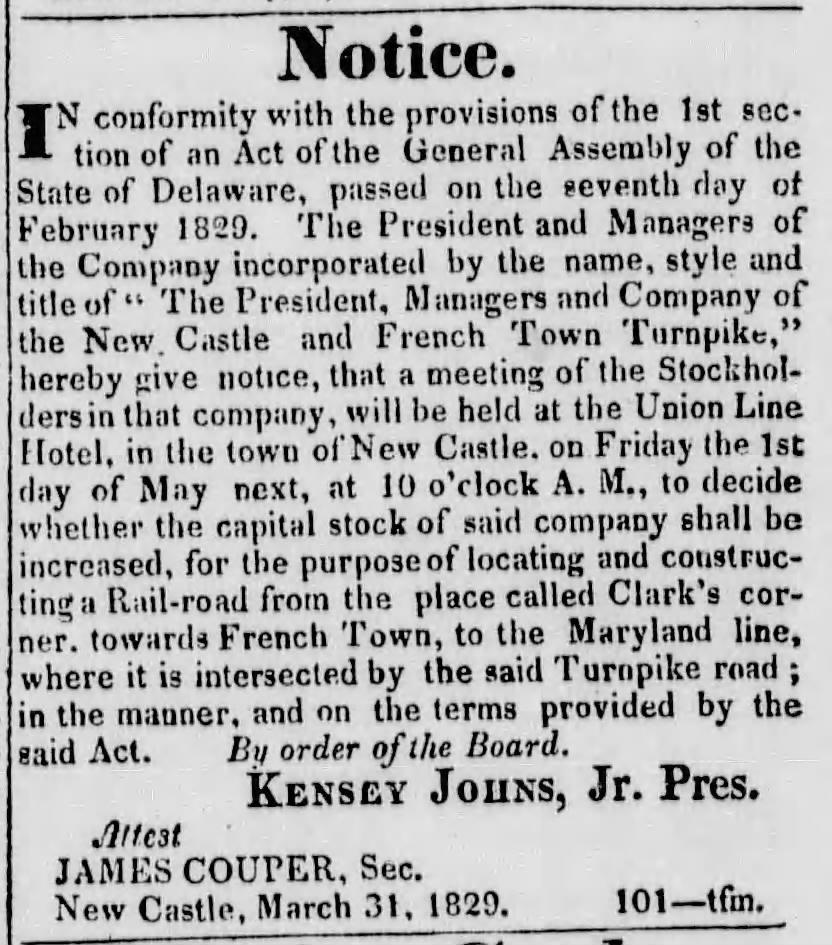

Between 1790 and 1840, Americans built thousands of miles of new roads and improved existing ones. Priority for maintenance was given to roads in areas where population, commerce and traffic was high enough to warrant the enormous investment in labor. Consequently, roads in the northeast tended to be better than roads south of Baltimore and west of the Appalachians. The number of turnpikes grew quickly after 1800 in order to pay for the needed roadways The New Castle and Frenchtown Turnpike Company was chartered in 1809 and had a turnpike between the towns fully open by 1816 This turnpike was a response to the expected future impact of the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal (C&D Canal). Canal construction began in 1804 but proceeded in fits and starts.

The first federally funded highway was the National Road which connected the Potomac River at Cumberland, Maryland with Vandalia, Illinois. It was constructed between 1811 and 1837 when funding was depleted. The expansion of stage and wagon travel, coupled with these new roads, permitted the movement of settlers, livestock and goods westward Crowned roads were designed to facilitate the draining of water to the sides of the road Even with all these improvements, critics wrote that American roads were still “inferior to those of any other civilized country.” This was probably due to the condition of local, country roads which were still narrow, strewn with rocks, stumps and other obstacles and often rutted and muddy.

Improved roads increased the amount of commercial traffic Freight wagons driven by teamsters were frequent sights on roads, with some wagons traveling great distances Another common sight was larges herds of livestock – cattle, sheep and pigs – being taken to market by drovers who were usually aided by their herding dogs.

Road travel did not cease in the winter. In fact, it was often easier to travel in a sleigh or sled over snow covered roads than to drive a wagon over rutted or rocky surfaces. Winter also had the advantage of occurring after harvest, so people engaged in farming had more time available for travel

On my return, I rode in a stage-sleigh from Philadelphia to New-York, slipping over the snow at the rate of eight or tea miles an hour. I had never, previous to the present journey, travelled in this manner, and thought it preferable, even to English post-chaises, for ease and expedition. I resumed my travels eastward from New-York on horseback to the Harlem river; the island appeared barren, rocky, and broken. The road which ran parallel to the Sound was unpleasant and without interest.

Elkanah Watson, 1785

Bagnell Geo Mifflin John Lacy P. Newbury and my Self went in two Slays to Germin Town being 6 miles to dinner and returned in the Even.g in 40 Minutes this kind of traveling is only whilst the Snow continues upon the Ground, as they have no wheels but only Stands upon two pieces of wood that Lyes flat on the Ground like a North of England Sled, the fore part turning up with a bent to Slyde over Stones or any little rising and are Shod with Smooth Plates of Iron to prevent their wearing Away too fast. The Sides of this Machine are boarded up about 18 Inches high & the Ends Much higher with one seat forward and the other behind, each holds two persons compleat as a Coach the 2 horses are Harnessd in the same manner as for a Wheel carriage abating for the goodness, and a pole from the forepart lyes between the horses as in a Charrot, the driver Stands right up in the forepart of the Slay and goes at a prodigeous Speed, All Ranks of people Covet this kind of Traveling or divertion for whilst the Snow lyes upon the ground…to go to the Neighbouring villages there to Eat, drink & return in the Eveng & Some later enough at Night

Birkett, 1751

12 [January]

James

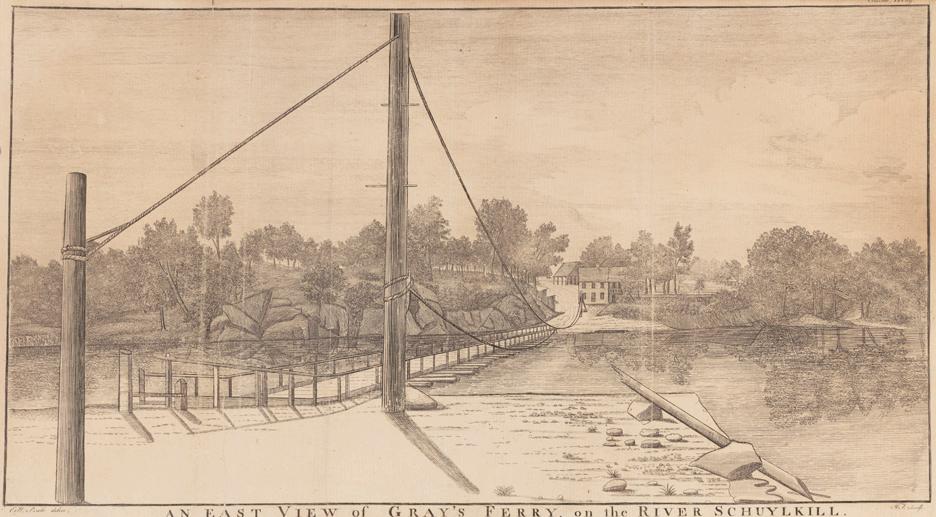

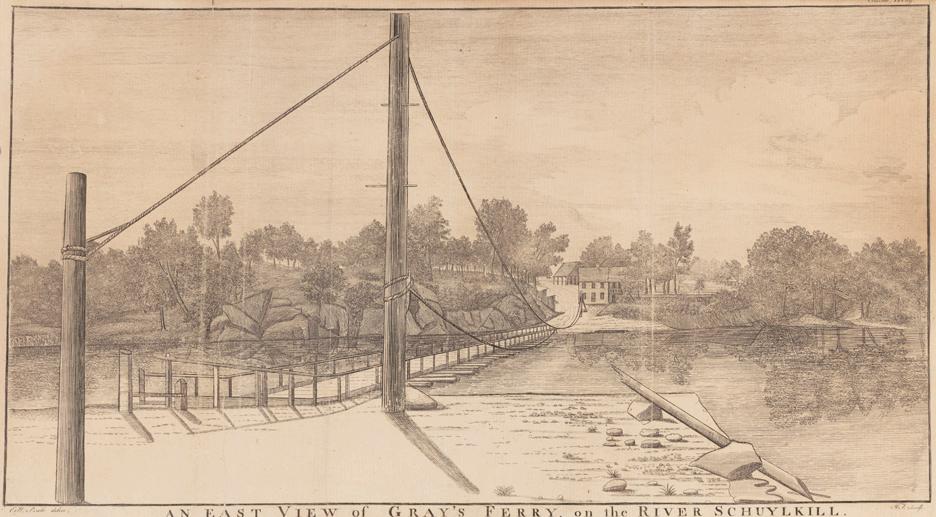

Bridges&Ferries

Bridges were made of wood or stone, and their construction and condition varied widely. Bridges could be very simple and primitive – almost temporary, while others were more permanent. Some bridges were completely stationary, while others that floated on the surface of water would move during crossing. Some bridges were narrow and meant for foot or horse traffic only, while others were wide enough for a carriage or stagecoach to cross. Eventually, in the 19th century with improvements in engineering, materials and construction bridges were made wider, longer and stronger in order to carry more traffic, including trains

In 18th century America bridges were all open to the air. In 1697, William Penn initiated the construction of a bridge on the Kings’ Highway that linked Philadelphia with cities to the north. Today, it is known as the Frankford Avenue Bridge, and is the oldest surviving roadway bridge in the country. The first documented covered bridge in America was a wooden bridge in Philadelphia, constructed in 1805 Hundreds more covered bridges were constructed over the next couple of decades and more than 10,000 existed by the end of the century

Contrary to popular belief, bridges were not covered to protect travelers from the weather. They were covered to protect the bridge itself from the elements, thereby reducing maintenance and repairs and extending the useful life of the bridge. In northern areas, snow would be shoveled onto the road surfaces of covered bridges to permit sleighs and sleds to travel on them without being impeded by a dry surface

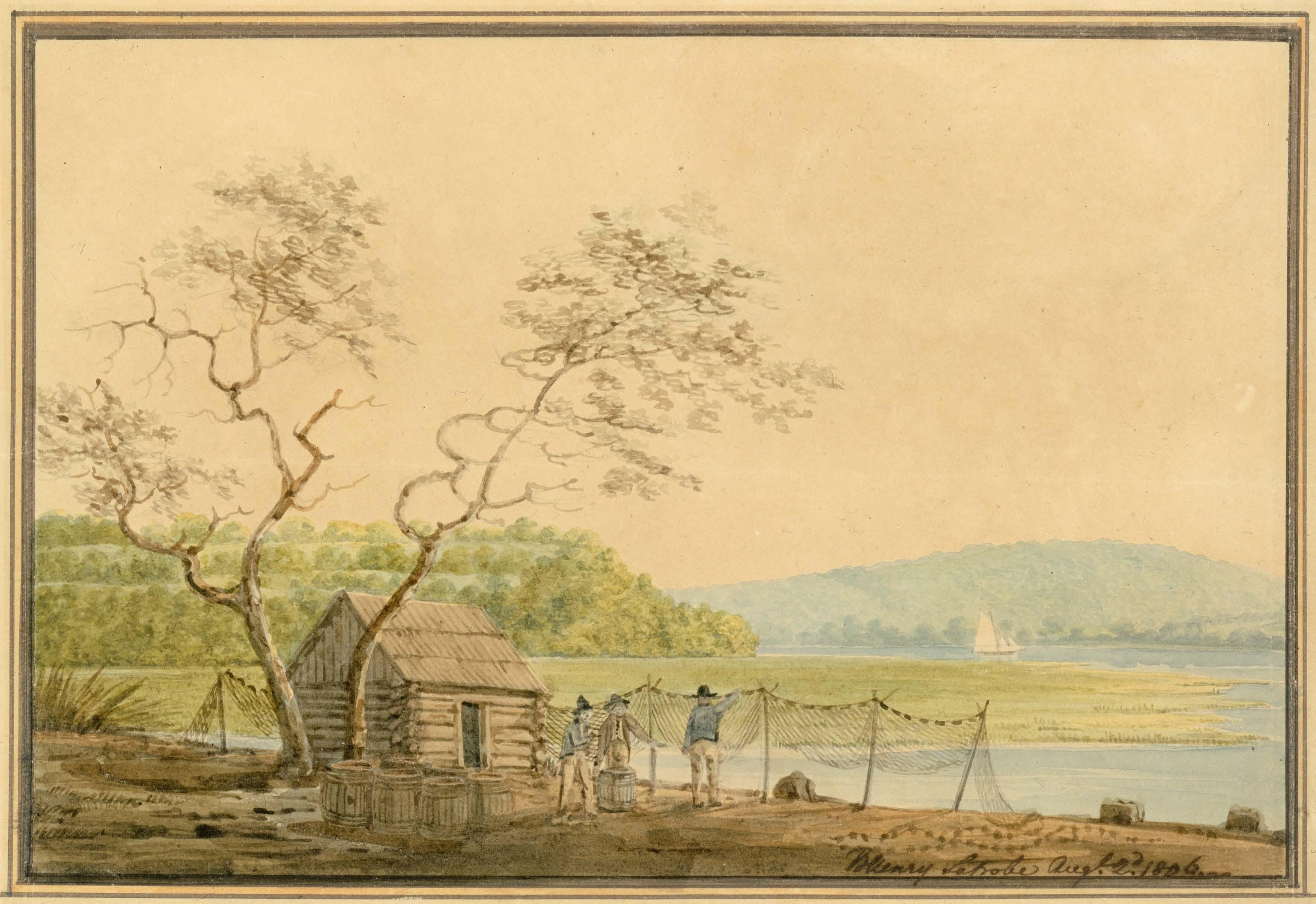

Especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, bridges were not always available to cross lakes, rivers and streams. In some cases, there may be a ferry nearby that could take a traveler, animals, and coach to the other side. In 1669, Swedish settlers in Delaware established the first ferry over the Christina River, just north of Newport. Another ferry crossing was established over the Brandywine in 1689. Wilmington developed between these two crossings in the 18th century

Bridges&Ferries

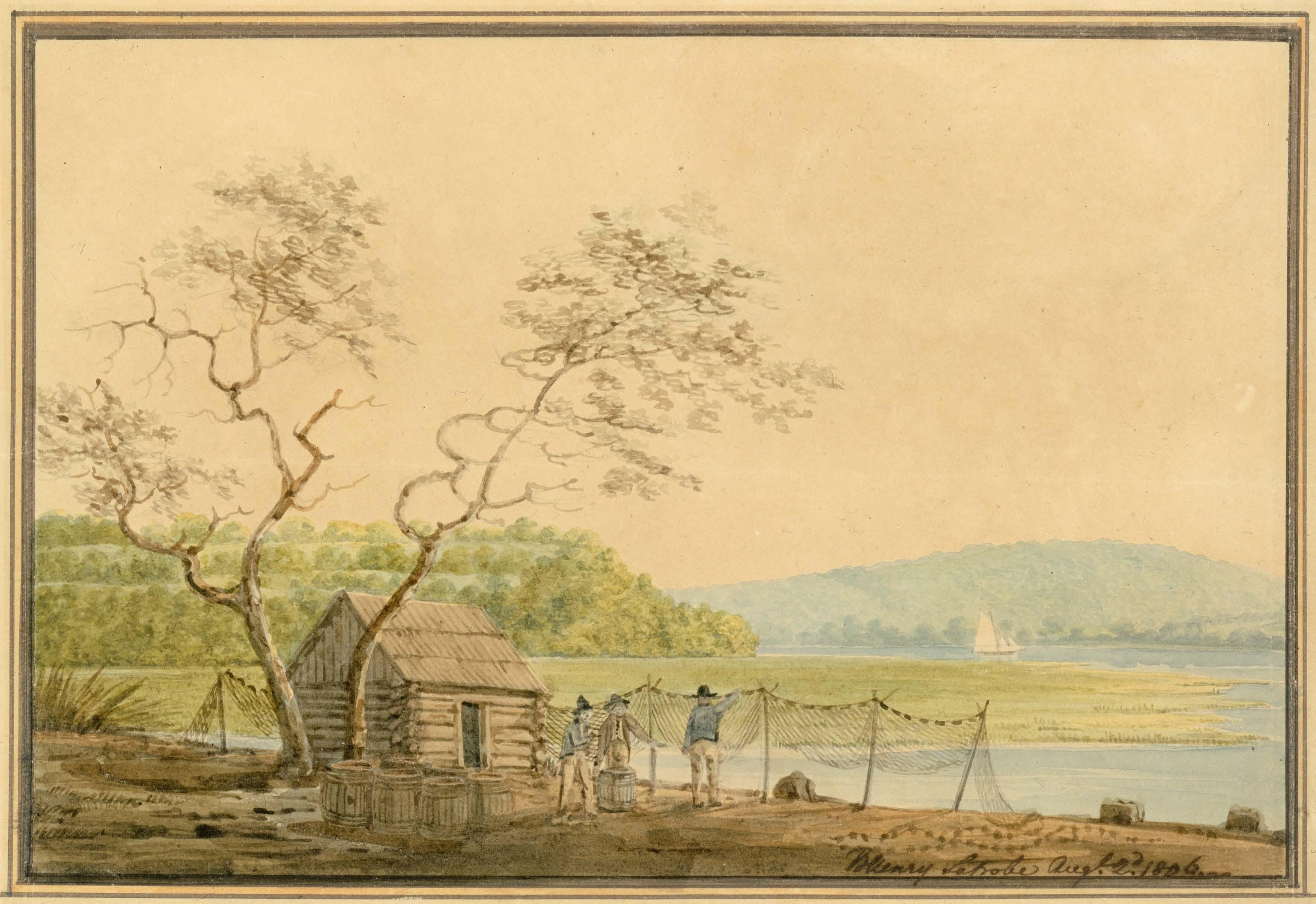

Early ferry boats were generally rectangular in shape, often very long, and designed with a shallow draft. They resembled rafts in that they typically did not have any covering for their passengers. Ferry boats were propelled by poling, rowing, sailing or by means of a line stretched between opposite banks. Poling was the most common and often the most dependable. If a river was too deep, rowing was a better option. For wide crossings, sailing was a good choice.

Ferry landings were literally just that – a landing spot on the riverbank Rarely was there a wharf nearby Often the only structure was a shed or barn for storage of supplies or animals needed to operate the ferry using a line, block and tackle. Ferries were privately operated, though toll rates were regulated by governing authorities. Some entrepreneurial ferry owners, like John Chads of Chadd’s Ford, operated a tavern to serve his ferry customers.

In New Castle, the Ferry House tavern and ferry service was operated at the corner of Harmony Street and The Strand as early as 1780 It was operated by Reynier and Elizabeth Penton Their ferry crossed the Delaware River to move passengers and goods between New Castle and New Jersey The tavern’s surviving ledger book records huge amount of firewood being brought to New Castle from New Jersey via this ferry in the early 19th century.

In the absence of a bridge or ferry service, a traveler may choose to “ford” a stream or river on their own by finding a shallow area without a strong current that permitted them to wade across without being swept downstream Fording places, like Chadd’s Ford in Pennsylvania, became well-known and businesses or even towns were often established nearby A person traveling on foot may find a local resident with a canoe to take them across for a fee – or possibly borrow a canoe or boat they find nearby. A traveler on horseback may need to swim their horse across the river if it is too deep to walk across. In all cases, fording a stream resulted in wet clothes and supplies. Travelers needed to be careful to keep important items, like firearms and gunpowder, dry when fording a river or stream.

I left Philadelphia on the 13th of January, 1785, in a stage, and crossed the Schuylkill over a floating bridge of three hundred feet in length, jointed with large hinges, by which it was elevated and depressed in the action of the tide. This bridge was constructed by the British in '78. Our road run parallel to the Delaware. We found the country pleasantly occupied by spacious farms, with excellent enclosures, and orchards, and adorned by villages and country seats.

Elkanah Watson, 1785

The toad to Baltimore is over the lowest of three floating bridges, which have been thrown across the river Schuylkill, in the neighbourhood of Philadelphia. The floating bridges are formed of large trees, which are placed in the water transversely, and chained together; beams are then laid lengthways upon these, and the whole boarded over, to render the way convenient for passengers. On each side there is a railing. When very heavy carriages go across these bridges, they sink a few inches below the surface of the water; but the passage is by no means dangerous. They are kept in an even direction across the river, by means of chains and anchors in different parts, and are also strongly secured on both shores.

Isaac Weld, 1795-1797

We got up at 4 o’clock, but had never really slept. It had been very cold and the wind was blowing the smoke from the fire into our tents. Almost everyone had either the sniffles, a toothache, aching joints or something. At 10 o’clock we reached the Susquehanna. After making it about half-way across the river we had to turn back. The wind blew so strongly that the waves were lapping onto the raft. The ferry people were afraid because the boat was so full – 22 people and 9 horses were riding on it. After a couple of hours we risked crossing again. After much anxiety and work we finally made it.

Salome Meurer, 1766

Oct 7

We crossed that ferry at twelve o'clock, and saw Wilmington about a mile to the left hand. It is about the largeness of Annapolis, but seemingly more compactly built; the houses all brick. We rid seven miles farther to one Foord's [Chadds Ford], passing over a toll bridge in bad repair, at a place called Brandywine. At Foord's we dined and baited our horses. There one Usher, a clergyman, joined our company, a man seemingly of good natural parts and civil behaviour, but not overlearned for the cloth. While dinner was getting ready a certain Philadelphian merchant called on Mr. Howard and with him we had a dish of swearing and loud talking.

Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744

Cristin Ferry—Wilmington—Brandywine

The Country from this Town to the great and Noble City of Philadelphia, is extremely pleasant, well Inhabited, fruitful, and full of Orchards,—you Cross Christines, a ferry over a River running into Delawar, which is deep, and safe riding in all weathers to Chester, from that to Skuylkill ferry, between which river and Delawar the City stands—the Country is Charming, the Ferry boats are the most convenient, and best served of any I ever Saw, you may drive in your Carriage and Six without getting out or Unharnessing one Horse, which is a great saving of time to Travellers.

Lord Adam Gordon, 1764-1765

We requested to be taken over the [Sassafras] river, as there is a ferry here, which they did, and it cost us each an English shilling. We then travelled along the river until we came to a small creek, which runs very shallow over the strand into the river. Here we had to take off our shoes and stockings in order to cross over, although it was piercing cold. We continued some distance further, along the river, to the Great Bay, when we came to another creek and called out to be taken across, which was done.

Jasper Danckaerts, 1679

5 th, Tuesday [November].

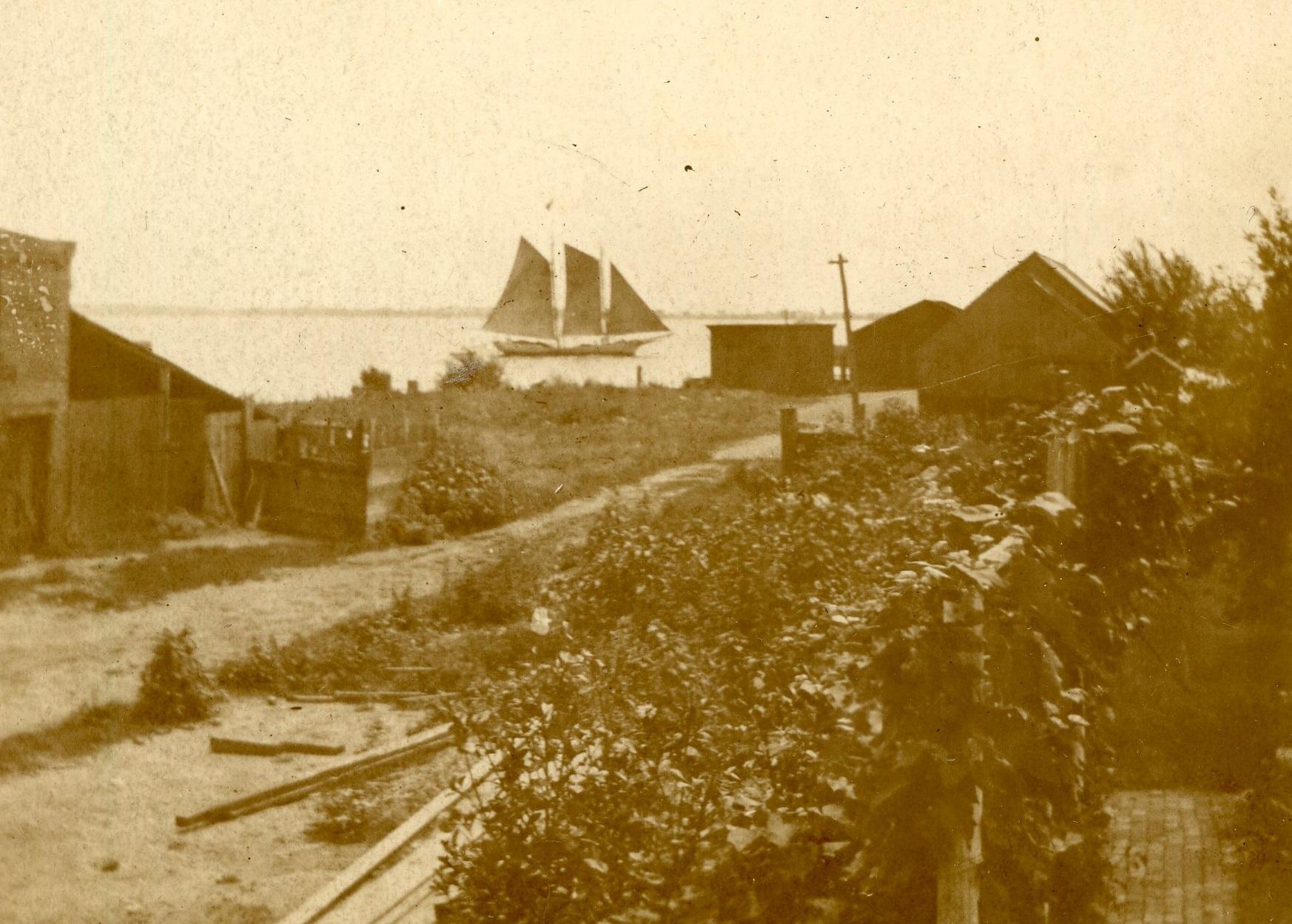

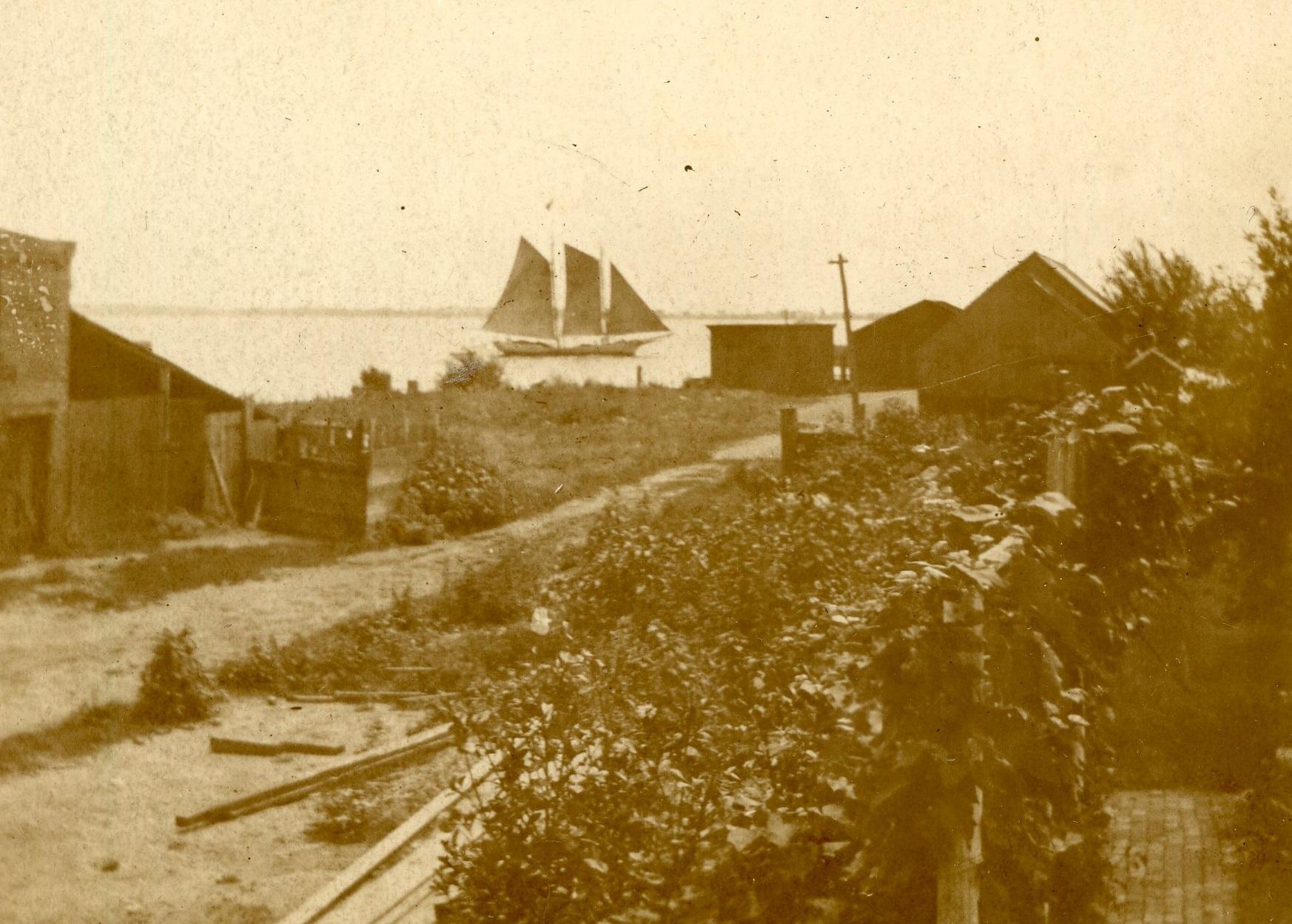

NewCastle&Transportation

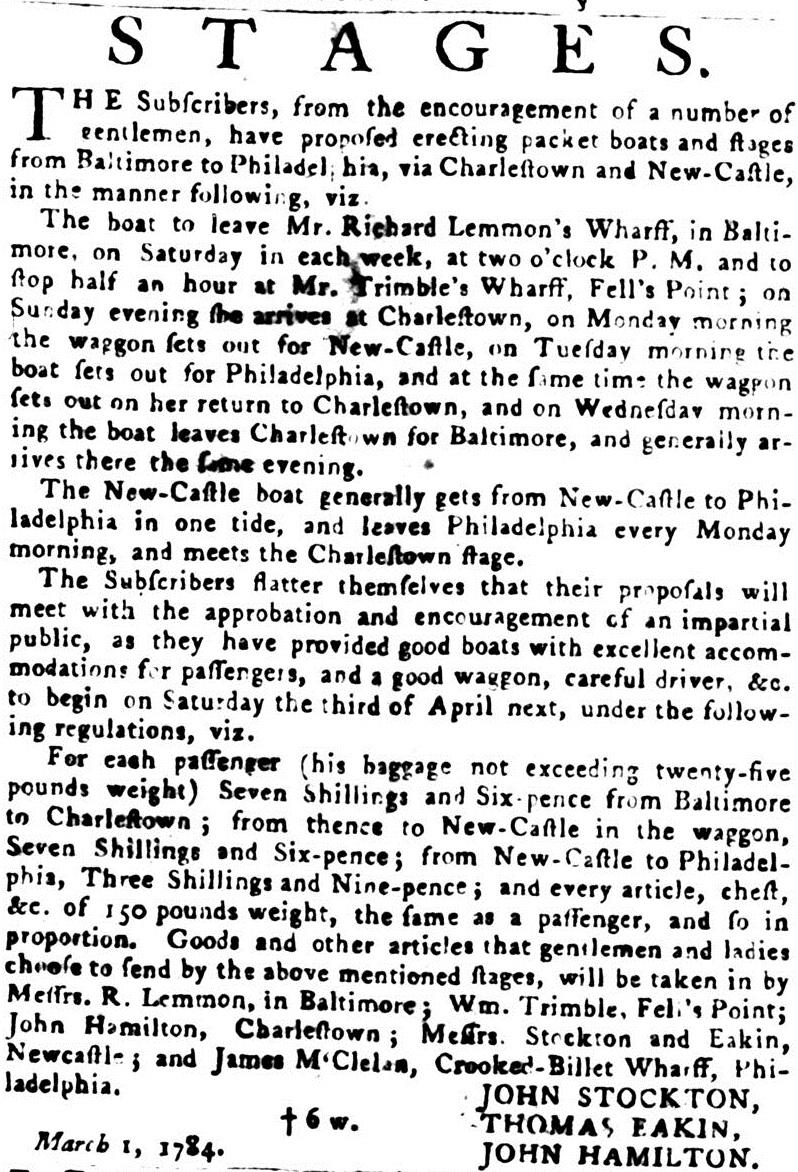

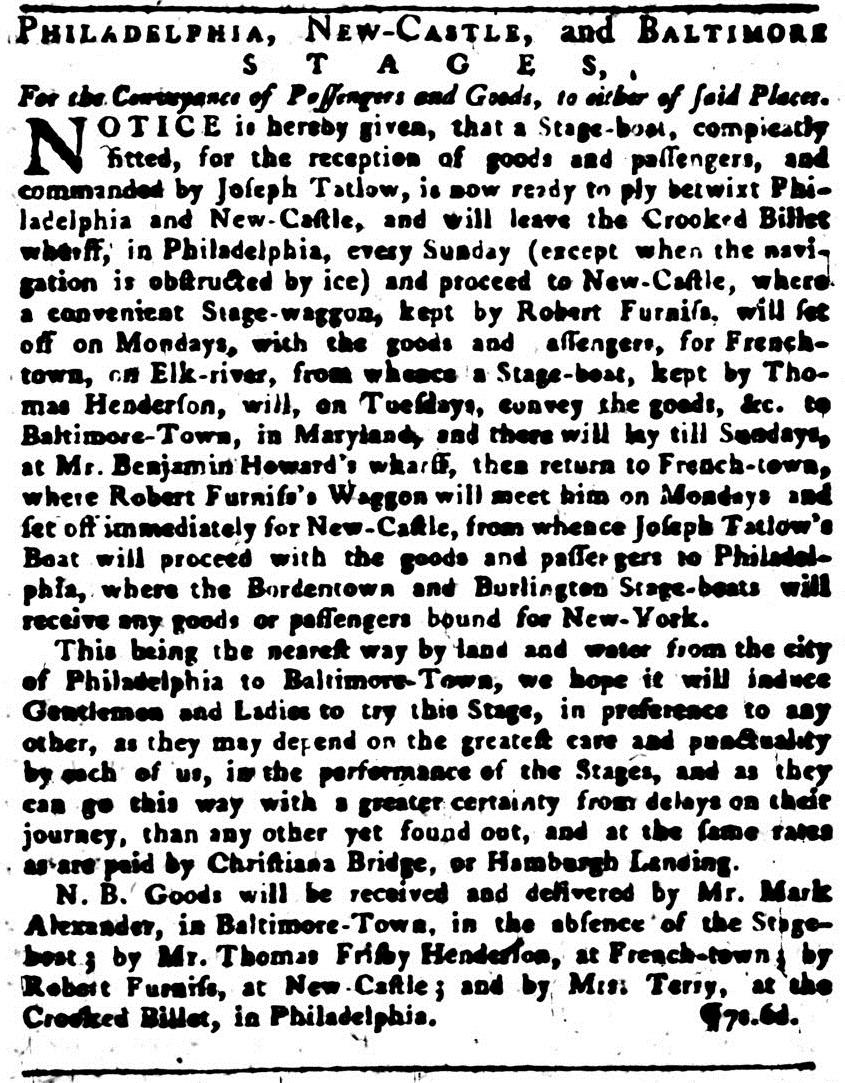

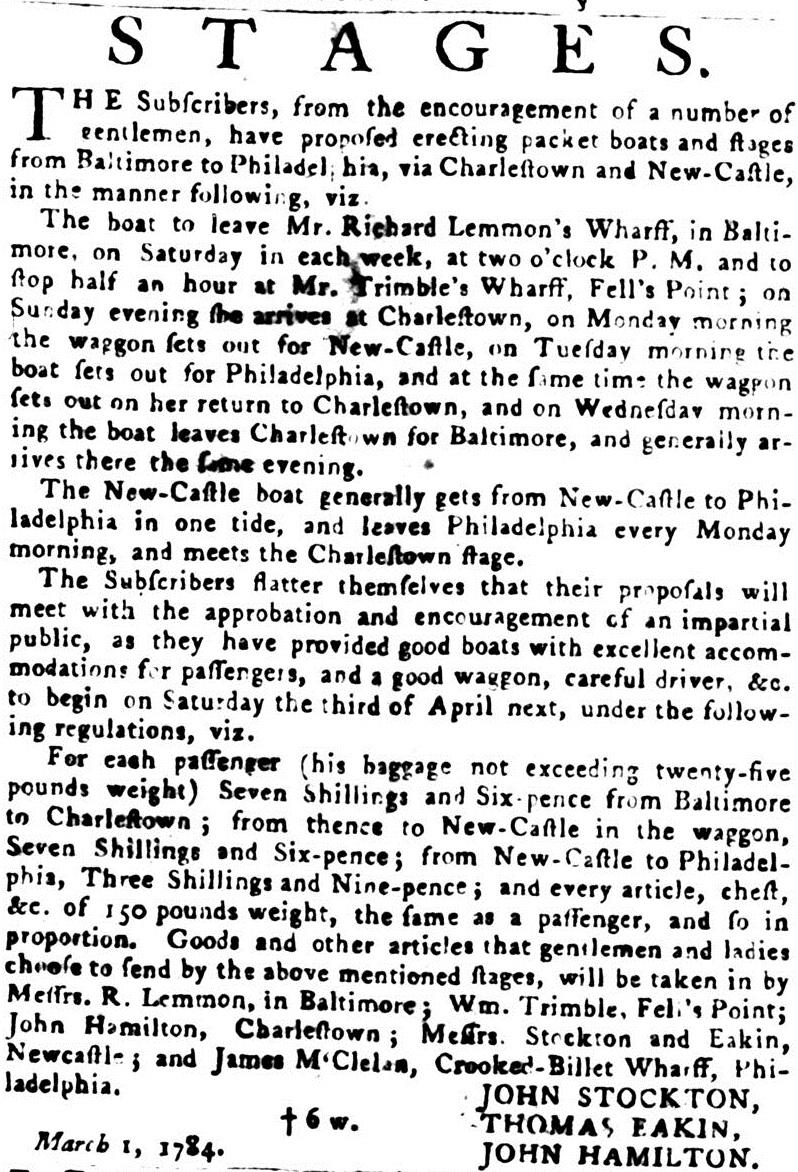

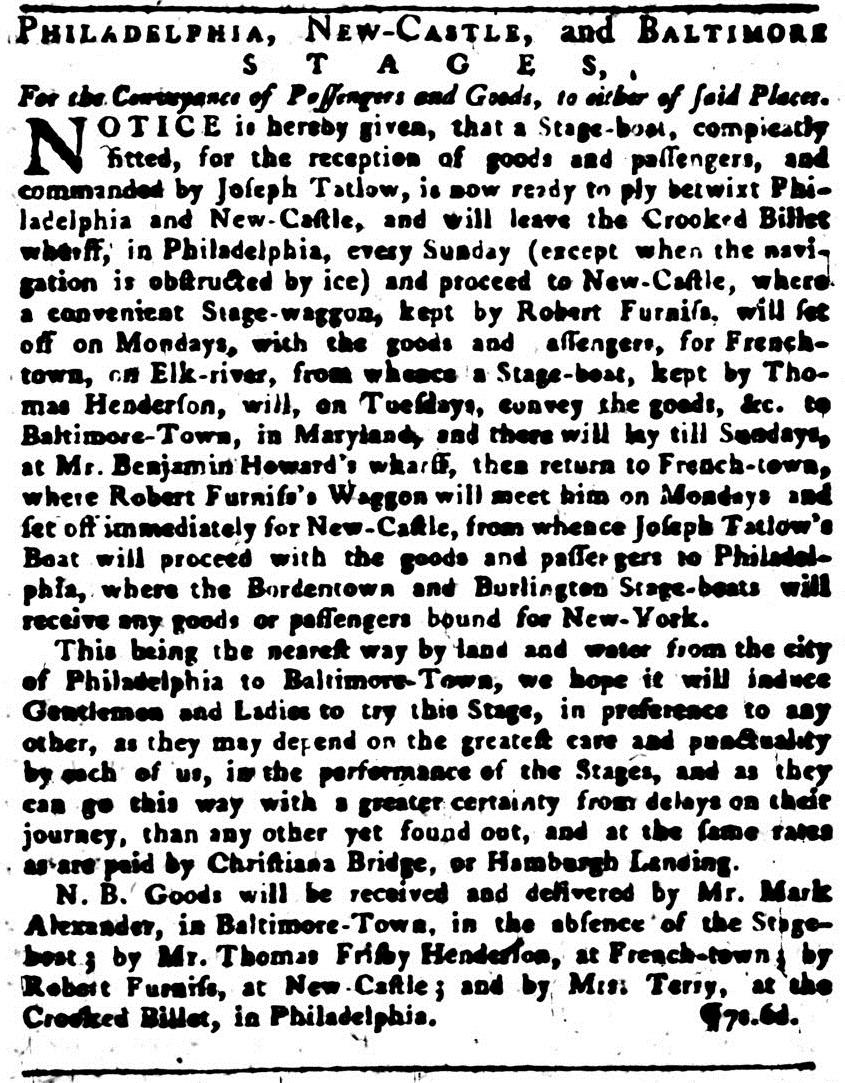

The 18th century saw New Castle rise in importance as a hub in the NorthSouth transportation network in the Mid-Atlantic. For travelers journeying between New York or Philadelphia in the north to Baltimore or Washington D.C. in the south, New Castle was often a stop on their journey. Typically, a traveler would sail from Philadelphia, down the Delaware River to New Castle, where they would ride in a carriage, wagon or later a stagecoach for 17 miles to Frenchtown, Maryland (near present-day Elkton) In Frenchtown, they again boarded a boat to sail to Baltimore They could continue to travel further south by land from there The arduous trip took more than 24 hours to complete

In 1775, New Castle entrepreneur Joseph Tatlow established a line of stagecoaches that traveled between New Castle and Frenchtown at regular intervals. He also established regular packet service between New Castle and Philadelphia. This brought many more travelers into New Castle, giving rise to an increase in the number of taverns in the port town. With Tatlow’s stage service, ships bound for Philadelphia would stop at New Castle to unload any cargo that was destined to cross the Delmarva Peninsula

In 1808, the Union Line Transportation Company was formed to provide stage and packet service to and from New Castle. New Castilians Thomas and John Janvier were investors in the company. During the next three decades the Union Line would help bring important improvements including turnpikes, steamboats, and railroads to the peninsula. In 1811, the New Castle Turnpike Company, with John Janvier as a director and Thomas Janvier as treasurer, completed a turnpike from New Castle to Clark’s Corner, a distance of three miles Three years later the New Castle and Frenchtown Turnpike Company completed a fifteen-mile road from Clark’s Corner to Frenchtown. The company opened the Union Line Hotel on The Strand in 1815. By 1823, a stagecoach bound for Philadelphia left the hotel every day except Sunday at 9:00 a.m.

The turnpikes connecting New Castle and Frenchtown were the main route of travel across the peninsula for 15 years until the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal was finished in 1829 Unlike many turnpikes in America, the New Castle & Frenchtown Road was kept in good repair throughout its history Repairs were expensive however, and tolls were considered to be high The Union Line steamboats supplied most of the business along the turnpike, and a contract with them helped keep the turnpike economically viable.

September 27, 1809.

About ten o'clock I set off, agreeably to appointment, with my brother George in his tandem, accompanied by a groom, to Washington. We dined at Chester, which is the shire-town of the county of Delaware in Pennsylvania. In the afternoon we passed through a pretty country, offering views of the river Delaware and some marks of good farming. We crossed the Brandywine on a bridge just building, suspended on iron chains upon the principle of the one lately constructed over the Falls of Schuylkill, and traversed Wilmington without stopping…To the southward of the main street we saw a handsome drawbridge upon piles over the Christiana Creek. We supped at Newport, a small village falling to decay. It 265 once contained five taverns and seven stores, which are now reduced to two of each kind. The inhabitants hope something from a turnpike-road now progressing, to intersect the Lancaster turnpike above Downingtown.

Breck, 1809

Samuel

TravelForWomen

In the 18th century, travel for women was most often for the purpose of maintaining familial and social relationships. Young women of middle to upper classes were expected to pay visits, travel to visit friends and spend their time reading novels, styling hair, dancing and taking carriage rides.These activities exposed them to an array of potential husbands.

For longer trips, women were very unlikely to travel independently, or even with a group of other women They rarely traveled alone, and instead were escorted by a male relative Even when escorted, traveling women may still be subjected to unwanted and unwelcome attention and comments, usually from men that they encountered along their route. In 1766, Salome Meurer, a 16-year-old Moravian girl traveling from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania to North Carolina with a group of Moravian women and a male escort, recorded this incident near Leesburg, Virginia: three Irishmen came who insisted on sleeping with us They tried everything to see if we would give in One of them said that he had never seen so many beautiful ladies He thought he would have to take one of us for his wife We pretended that we could neither see nor hear them and bade the Saviour to stop up our ears and close our eyes when such people were around us. Brother Utley needed quite a while to get rid of them. Then we lay down to bed near a bubbling stream.

When traveling overnight, women stayed in the homes of social equals rather than inns, taverns or boarding houses Patronizing a tavern, unless attending a public function like a ball, could tarnish a woman’s reputation

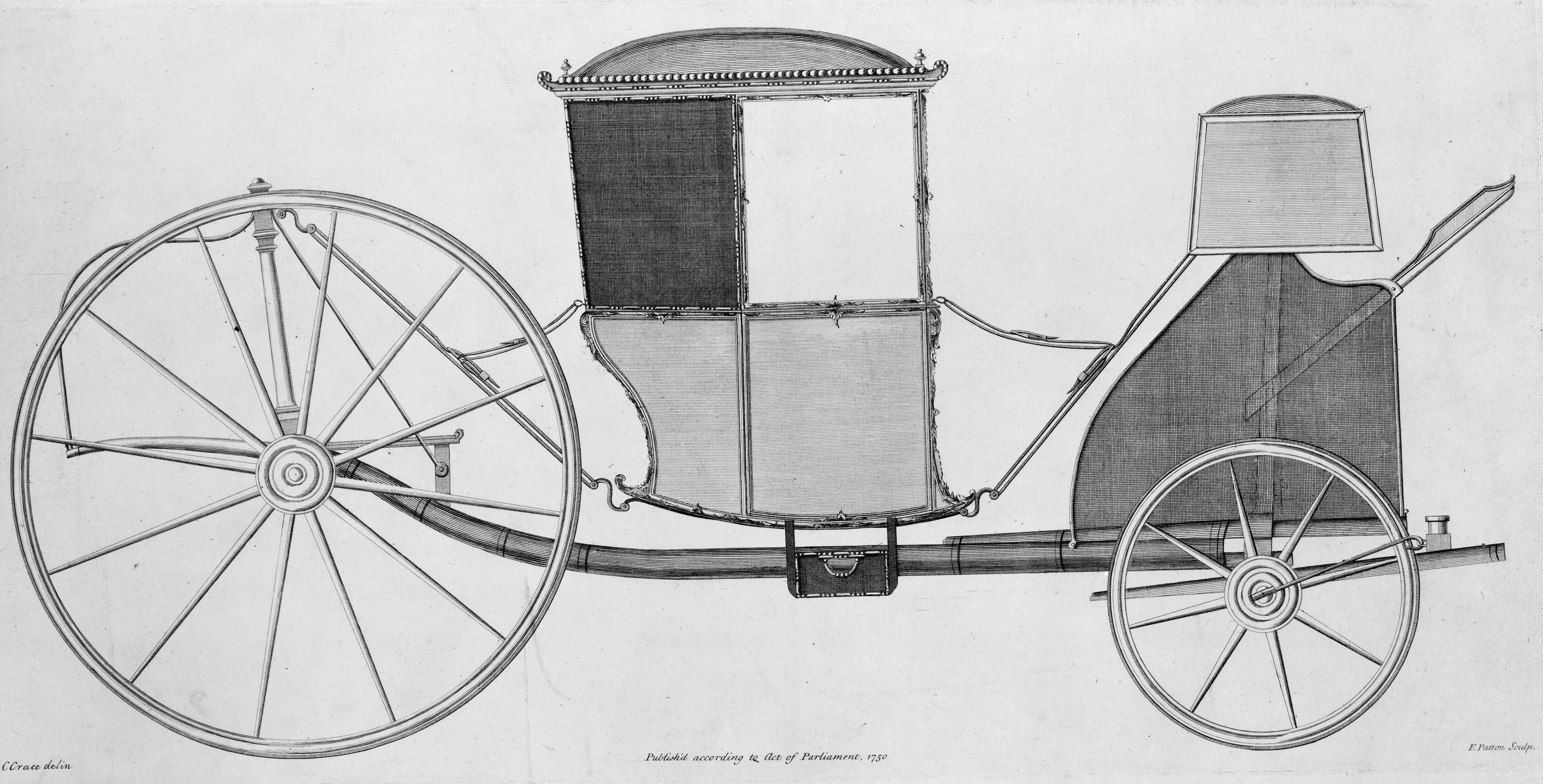

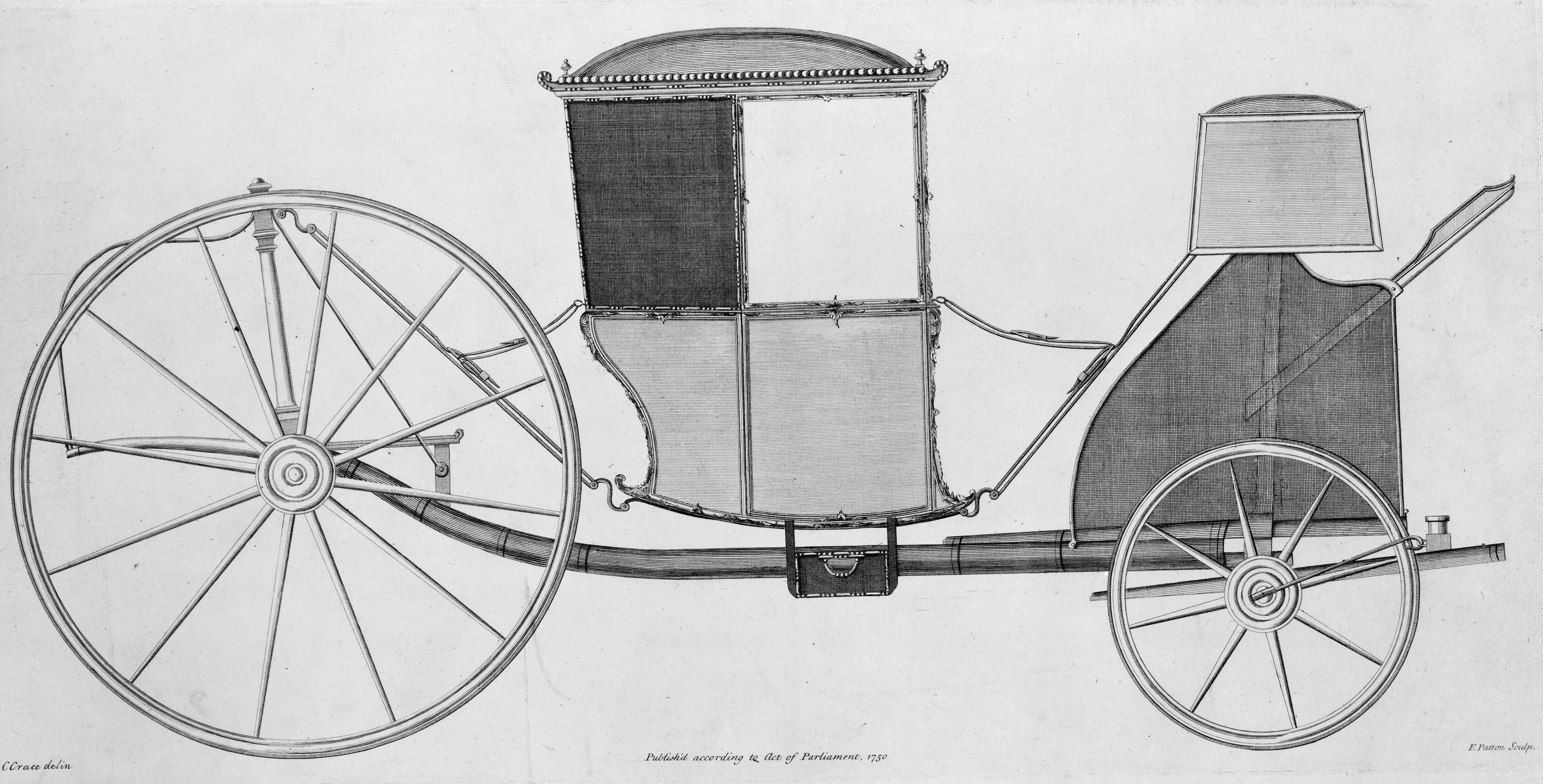

Women were not generally trained in riding horses. Because of the design of their clothing, women that were trained in riding typically rode sidesaddle, which was infinitely less stable for journeys over rough terrain. Instead of traveling on horseback, women tended to ride in a private carriage or public coach.

It was pouring rain and we were soaked. At noon Brothers Utley and Schnepf went ahead to make a fire for us to warm ourselves, for we were stiff and frozen. We received a drink of warm rum and then marched on. The rain fell on us like someone was pouring it out of a barrel. The entire trail was covered with water. At one point the water looked deep. But we didn’t think we could get any wetter than we already were so we went right through and found ourselves standing knee-deep in it. Normally, we would have all sat in the wagon.

Salome Meurer, 1766

Oct 23

Kitty was out at _______ poor little girl she had a narrow escape a few days before Mamma wrote –she and the girls were with the noble captain in the phaeton, the horses broke away from the carriage and ran off but not before they had dashed it over with all its fair and lovely contents….

Letter to William T. Read at Princeton from George Read III in New Castle, June 15, 1808

TravelForWomen

Women traveled through the first 7 months of pregnancy Travel was difficult following delivery due to nursing and would require taking the baby with them. Weaning trips were usually taken after a child turned one. The Rev. Joseph Green records in diary on April 12, 1702 that he had taken his wife to her parents, and “came home to wean John,” the couple’s 17 month-old son.

By the 19th century, American women were able to move around more freely, and travel further than their European counterparts But still, their movement was limited by custom, economic dependence and the needs to manage their households. As the 19th century progressed, the ability of women travel continued to expand. In 1822, Elizabeth Ward took an exciting 28-mile chaise ride on her own and she exhilarated at the freedom it provided her, as well as her own skill saying, “I…never so much as took the whip in my hand all the way.”

By the 1830s, as new modes of public transportation were developing, women were often seen traveling alone on stagecoaches, steamboats and eventually railways Steamboats and railroads sometimes provided separate compartments for women, but not always.

In 1847, Domingo Sarmiento wrote of how Americans treat young women saying their ways had “no parallel and which are unprecedented on this earth. The unmarried woman… is as free as a butterfly until marriage. She travels alone, wanders about the streets of the city, carries on several chaste and public love affairs under the indifferent eyes ”

I am very happy to inform my dear Mr. Read that we arrived safely at this place last evening. I think

I am already benefitted by my journey tho I have not _____ my ague but it is so very slight that I feel no weakness on the day succeeding the chill. I found the stage rather fatiguing after the roads become strong. Indeed the jolting affected me so sensibly that I arrived at Harrisburgh in the greatest dejection of spirits and determined not to proceed to Carlisle for a week. But going to a warm bed and drinking plentyfully of wine-whey, I found myself so much recovered as to be able to comply with the wishes of my affectionate parent who was unwilling to leave me behind.

Letter

to G. Read Jr. in New Castle from Mary Read in Carlisle, PA, October 24, 1792

If we should proceed to Carlisle could William be accommodated with lodging in the house with you. I flatter myself Mrs. Hamilton will house me.

Letter to Bedford Read in Carlisle, PA from Mary Read in New Castle, June 9, 1814

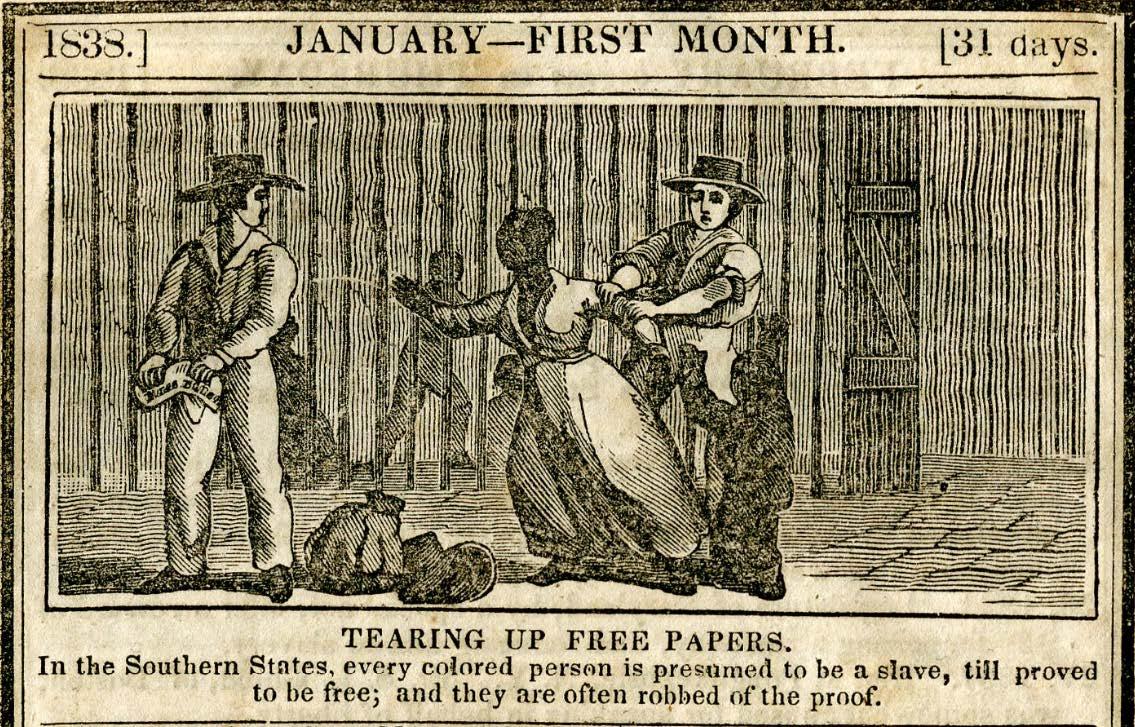

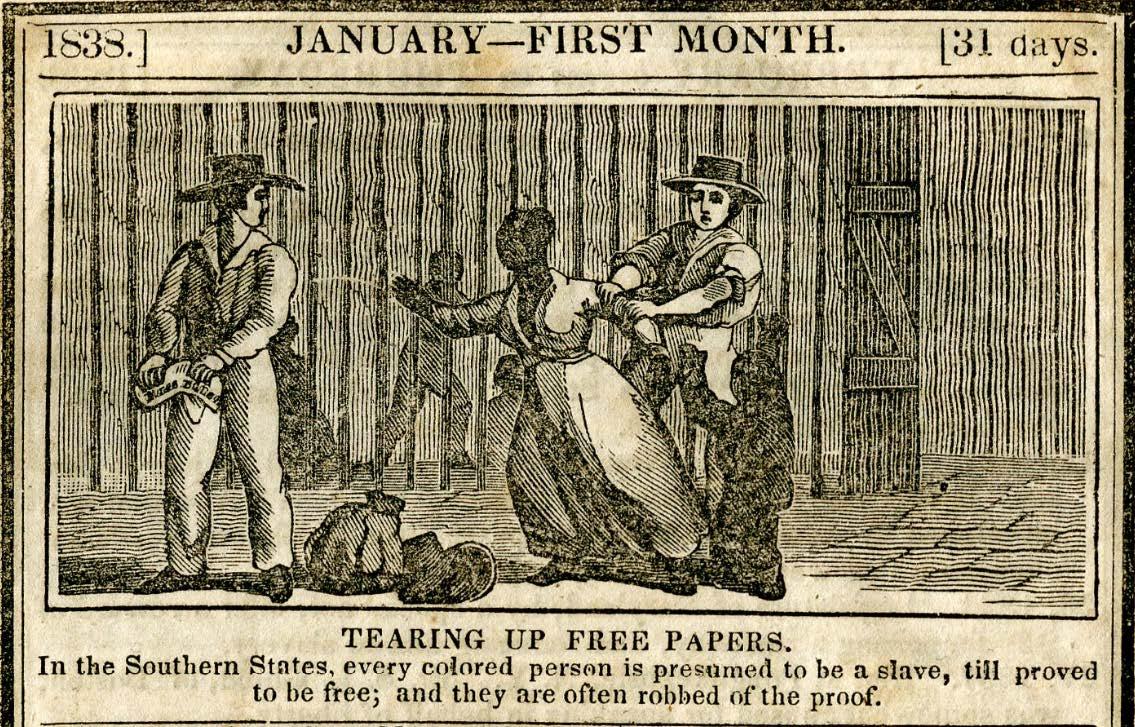

TravelForBlackPeople

In colonial America, most black individuals were enslaved Only about 5% of black people were “free.” Free blacks owned land and homes, operated businesses, fought in the War for Independence and War of 1812, and in some places voted. Even so, their lives were still circumscribed by discriminatory laws and attitudes of white society. Travel outside of their home communities could be difficult at best.

It was difficult, and often impossible, for enslaved persons to move about freely Sundays permitted enslaved persons the most freedom to move about as they traveled to visit friends, family and attend services. Some enslaved individuals could travel because of their responsibilities as drovers or teamsters. In urban areas, they were freer to travel to the town’s market, shops and houses to conduct business.

In some cases, when someone that was enslaved had special skills, such as carpentry or blacksmithing, they may be hired out If that required them leaving their place of enslavement, they were required to have a tag or pass giving them permission to travel by their enslaver Many people traveled with the individuals that they enslaved. Famously, George Washington traveled with his enslaved valet, William Lee, during the course of the American War for Independence.

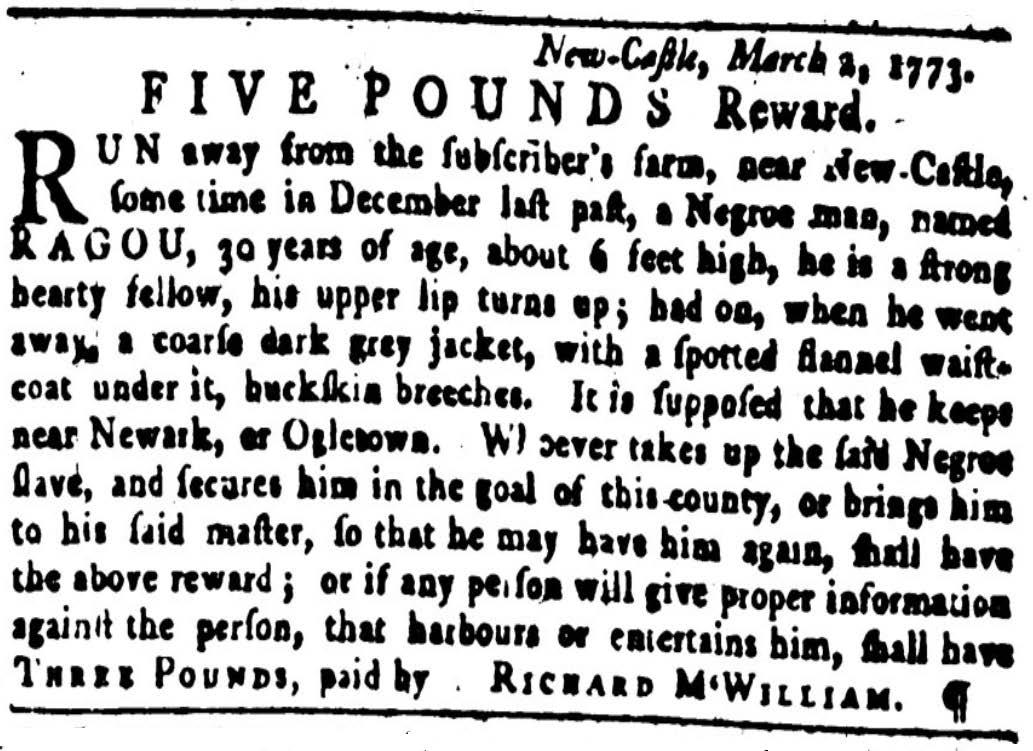

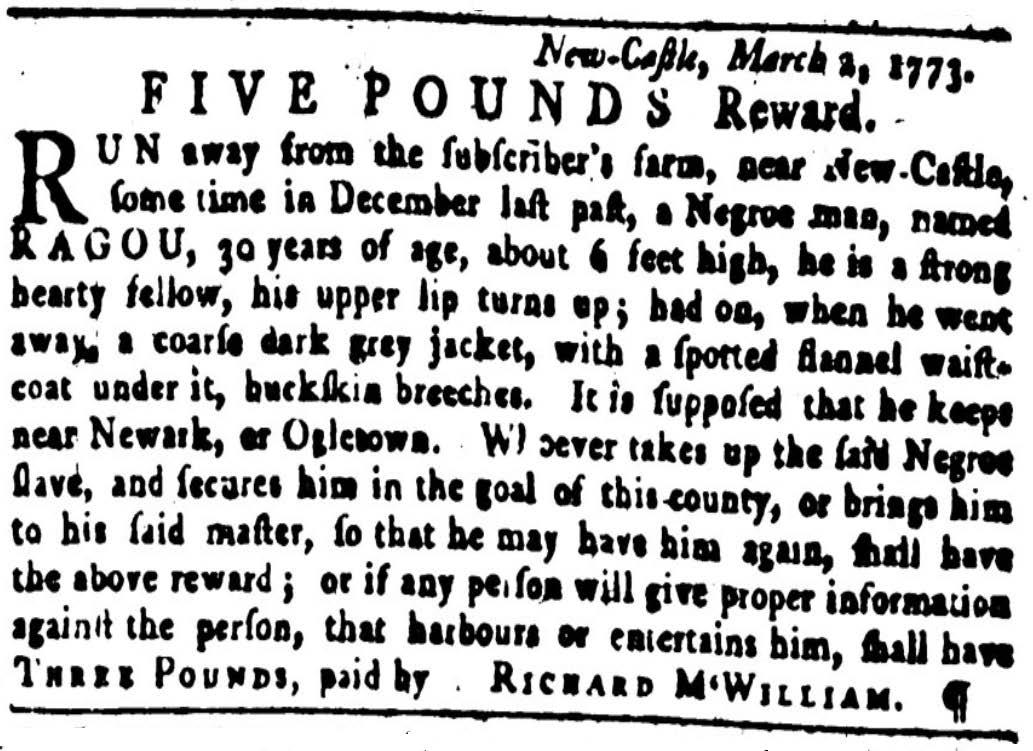

Prior to the Revolutionary War, all British colonies in North America permitted slavery, so it was very hard to escape a life of enslavement Nonetheless, many people tried to find freedom by leaving the places of their enslavement Enslavers placed “runaway ads” in newspapers such as the Pennsylvania Gazette to request help in finding and returning the person.

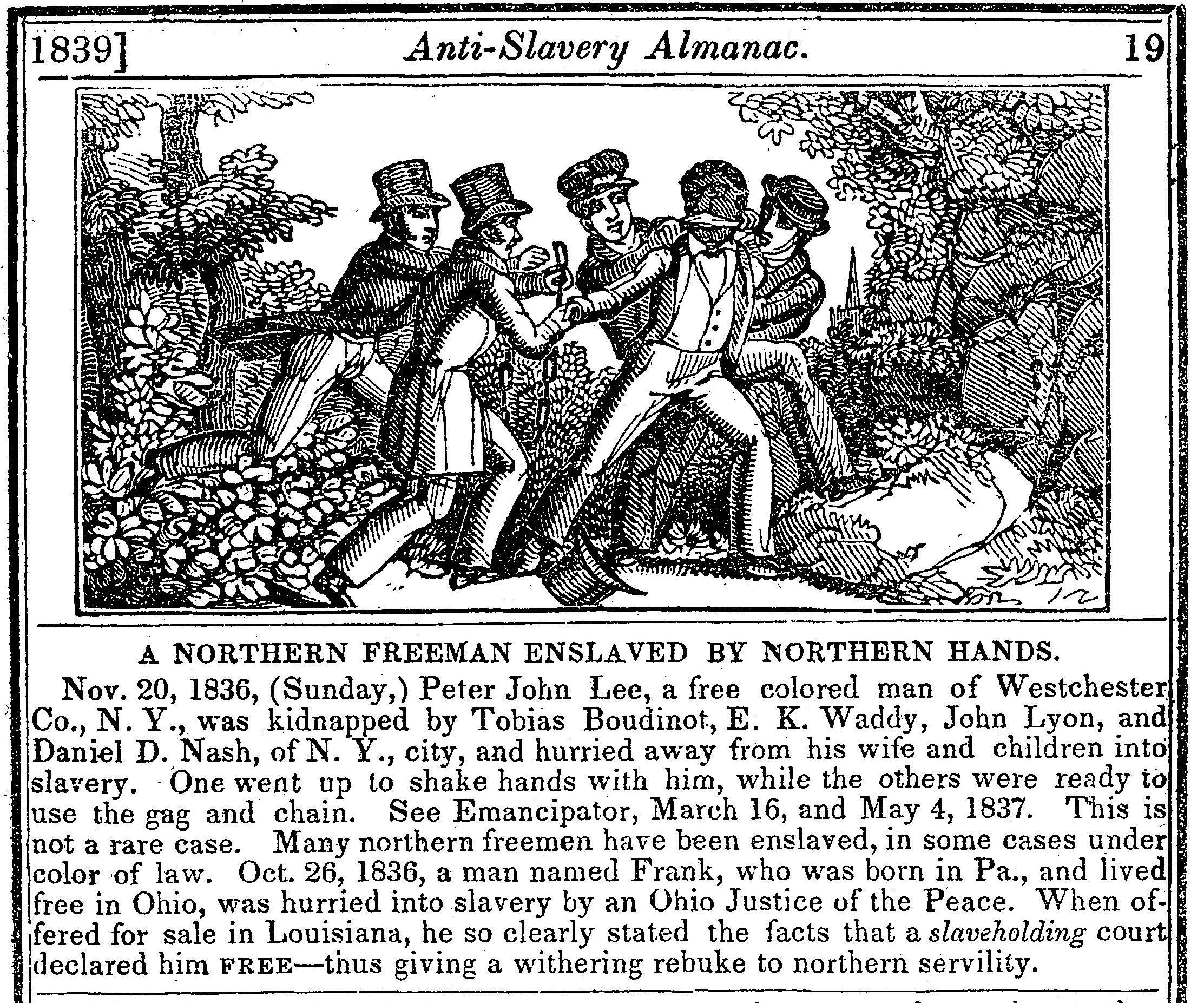

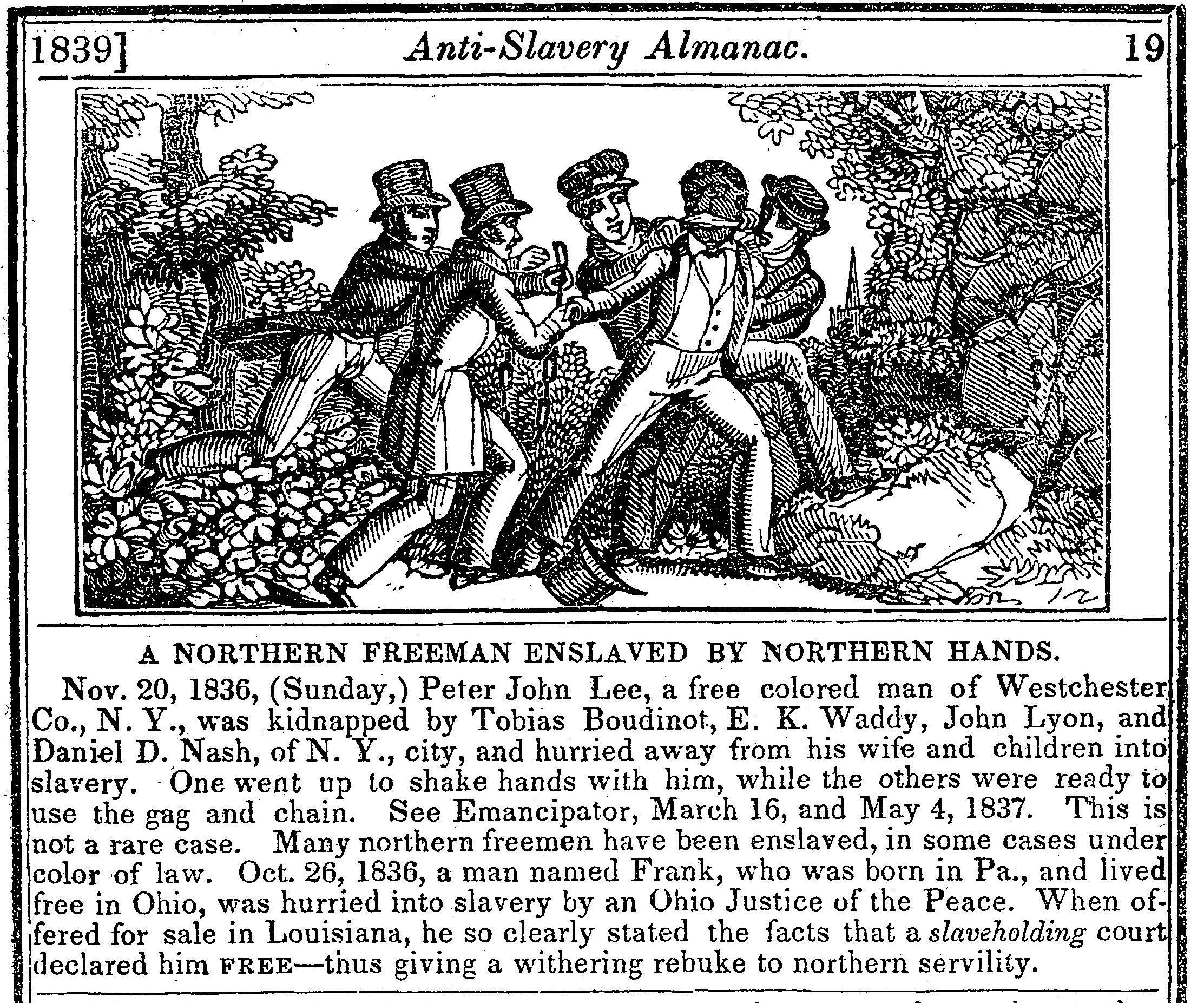

In 1806, Congress ended the international trafficking of African people into the United States. However, it did not end enslavement within the borders of the United States. This created high demand for enslaved people already in the country, especially as new territories became states. This gave rise to a domestic slave trade which involved the sale of both enslaved and free persons into enslavement in the Deep South

In the first place we took a small canoe and crossed the river till we came to a plantation owned by a man named Travis. He had a large sail boat that we desired to capture, but we did not know how we should accomplish it, as they took a great deal of pains generally to haul her up, lock her up and put the sails and oars in the barn. As it was the Sabbath day, the young folks had been sailing about the river, and instead of securing her as they usually did, they left her anchored in the stream with the sails and oars all in the boat. This was very fortunate for us…

James L. Smith, 1838

DelawareStateLaw

“If any suspicious colored person shall be taken up travelling in or through this government without having a sufficient pass signed by some Justice or proper officer of the place from whence he or she came, approved and renewed by some Justice of the Peace in the parts through which such person hath travelled, or shall not otherwise be able to give a good and satisfactory account of him or herself to the justice before whom he or she shall be brought, such person shall, by the said Justice, be committed to the gaol [jail] of the county where he or she shall be taken up and be deemed to be and dealt withal, as a runaway servant.”

Passed January 19, 1826

Prior to the Civil War, free blacks needed a pass signed by a white man to leave the State of Delaware. If they remained out of the state for more than six months, they could not return. Free blacks were not permitted to move to Delaware from other states.

TravelForBlackPeople

During this period, travel for black people, especially when far from home, could be very dangerous. Kidnapping of black people was rampant in Delaware and across the Delmarva Peninsula. They needed to be careful about the routes they traveled along, where they ate, slept and who they asked for assistance. Kidnappers cared not whether a person was free, enslaved or a freedom seeker. Once abducted, an individual was sold into bondage, often in the Deep South or even the West Indies The most notorious gang of kidnappers on the Delmarva Peninsula was led by Patty Cannon Her gang operated widely from their home base near Seaford, Delaware

Kidnapping was not just a problem in lower Delaware. In New Castle County, in 1816, fifteen-year-old Bathsheba Bungy, a free black girl “went out for chips,” and was abducted by two white men who drove her into Maryland in a carriage. Eventually they brought her back to Appoquinimink Hundred where she was released. Her abductors were caught, tried in the Court House at New Castle, and convicted by an all-white male jury Each of the kidnappers was publicly whipped and placed in the pillory with “both his ears nailed thereto ” After an hour in the pillory, they were released by cutting off the soft, lower section of each ear.

When using public transportation, free blacks were sometimes required to ride on the outside of the stagecoach or travel on the deck of a steamboat rather than in an interior compartment. In most areas in colonial America, taverns were prohibited by law from serving black people, whether free or enslaved They were also prohibited from serving servants, apprentices, and minors

Many tavern keepers ignored these laws and restrictions and provided food and drink to all of these people, sometimes setting up credit accounts in their ledgers to record their business transactions. When caught, the tavern keepers were fined.

The free Blacks in the Eastern States, are either hired servants, or they keep little shops, or they cultivate the land. You will see some of them on board of coasting vessels. They dare not venture themselves on long voyages, for fear of being transported and fold [sold] in the islands.

J. P. Brissot de Warville, 1788

Stagecoaches

Stagecoaches were the most common method of transporting Americans over long distances starting in the 18th century. At first, stagecoach lines were few and far between, but after 1790 an ever-expanding network of lines and routes began to take shape. By the mid-1820s, a traveler could make connections easily when traveling between major cities in the United States. Stage travel reached its peak by the mid-1830s, just before the emergence of the railroads.

Stages were popular because they were faster and easier than most private coaches Horses that drew stages were frequently changed out for fresh horses, and passengers could relax instead of dealing with the effort and stress of driving their own coach. Nonetheless, stage travel could be uncomfortable as the coach bounced and jostled over rutted and rocky roads. Up to ten passengers could be packed tightly together in the stage with one of the ten forced to ride outside with the driver (at no discount). In close quarters, at a time when personal cleanliness was irregular and rudimentary and tobacco and alcohol use common, passengers often had to tolerate a variety of offensive odors emanating from their fellow passengers As the coach traveled up steep inclines the passengers may be asked to get out of the coach and walk up the hill to lighten the load for the horses.

Stages were mostly open to the weather. In dry weather, travel was often dusty though the open compartment provided a view of passing scenery. In wet weather, wind easily drove rain and snow past the leather curtains and onto the passengers During winter, passengers were cold as the compartment was unheated, though they could bring a personal foot stove with them for warmth

Stagecoach travel was not without its own unique challenges and hazards. Made of wood, leather and iron, stagecoaches were relatively fragile vehicles and often suffered breakdowns on the road that needed repair immediately in order to continue travel. In some cases, the breakdown was just inconvenient. In others, however, it could be very dangerous and, on rare occasions, even fatal. Stagecoaches commonly became “upset” while traveling, and on a long journey travelers should expect to be overturned at least once or twice Upsets had a variety of causes – runaway horses, broken wheels or axles and steep inclines that caused the stage to pick up speed and lose control Even with the frequency of stages being upset, they were safer than lighter vehicles like sleighs, chaises and phaetons which had a higher incidence of overturning or having passengers fall out of the vehicle.

My father took me with him when he and Louis McClane went to meet Lafayette, when he came to Wilmington and New Castle in 1824. We started from New Castle early in the morning with a pair of bay horses attached to a dark green colored barouche with a standing top. We drove up to the Practical Farmer [a tavern], just this side of the Delaware and Pennsylvania dividing line, and stopped there to await the coming of Lafayette and the Pennsylvania delegation who escorted him to Delaware. Here we met him, with hundreds of others who were gathered there to receive him. He was greeted with cheers, and flowers were strewn in his pathway as we marched on to Wilmington.

Late in the afternoon of the same day he was escorted to New Castle….As we were passing our woods, and coming in sight of New Castle, these cannons began to boom, and continued to boom incessantly until Lafayette entered the house of George Read [II], on Water street…In the evening Lafayette attended the wedding of Charles I. duPont to Miss Dorcas Montgomery VanDyke, the daughter of U.S. Senator Nicholas Van Dyke, at her father’s house on the westerly side of Delaware and Pearl [West 3rd] streets. Lafayette was the guest of Mr. Read and spent the night with him. In the morning the Delaware delegation escorted him to the Maryland line. A delegation of Marylanders then took him to Frenchtown, and thence by steamboat to Baltimore.

Colonel Joseph H. Rogers, 1824 (as recalled in 1907)

The carriage is a kind of open waggon, hung with double curtains of leather and woolen, which you raise or let fall at pleasure: it is not well suspended. But the road was so fine, being sand and gravel, that we felt no inconvenience from that circumstance. The horses are good, and go with rapidity.

These carriages have four benches, and may contain twelve persons. The light baggage is put under the benches, and the trunks fixed on behind.

J. P. Brissot de Warville, 1788

19th Do. [May] went with another set of Company from portsmouth to see a ship launshed on the western Branche. as we were going along, I in a single Chaire, my horse took fright at somthing and galoped of the road into a field where there was a quantity of stumps of trees one of which overturned my Chaire. the horse going as fast as his heels Could carry him, I was pitched head foremost on another stump, which Cut my head and bruised my left shouldre very much. the horse Continued until he Brok the Chair to pieces. one of the Company took me in a Chair and put me Down at my lodgings. was blooded twice that Evening, notwithstand'g the fevor took me and held me three days, but by Doctor Purssels help I was soon well.

A French Traveller in the Colonies, 1765

the

Mrs. Read got here this morning after a pleasant passage of only 17 hours from New Castle, she feels better of the journey but did not sleep well in the boat, she is now in bed after taking a hearty breakfast at dinner we shall drink your health…

To G. Read Jr. in New Castle from J. Holmes in Baltimore, September 4, 1807

Dear Sir,

The carriages made use of in Philadelphia consist of coaches, chariots, chaises, coachees, and light waggons, the greater part of which are built in Philadelphia. The equipages of a few individuals are extremely ostentatious; nor does there appear in any that neatness and elegance which might be expected amongst a set of people that are desirous of imitating the fashions of England, and that are continually getting models over from that country. The coachee is a carriage peculiar, I believe, to America; the body of it is rather longer than that of a coach, but of the same shape. In the front it is left quite open down to the bottom, and the driver sits on a bench under the roof of the carriage. There Are two seats in it for the passengers, who sit with their faces towards the horses. The roof is supported by small props, which are placed at the corners. On each side of the doors, above the pannels, it is quite open, and to guard against bad weather there are curtains, which are made to let down from the roof, and fasten to buttons placed for the purpose on the outside. There is also a leathern curtain to hang occasionally between the driver and passengers.

Isaac Weld, 1795-1797

ARevolutioninTravel

As the 18th century progressed, early road networks and travel service providers improved greatly. By the late 18th century, people were moving around the country more easily and frequently than ever before. By the 19th century, travel experienced a true revolution with improvements in the speed, reach and experience of all classes of travelers. Today, we think of Americans as living in a very mobile society that is connected largely through technology. This is nothing new The roots of American mobility and reliance on technology to stay connected to each other can be directly traced back to the transportation boom of the late 18th and early 19th centuries

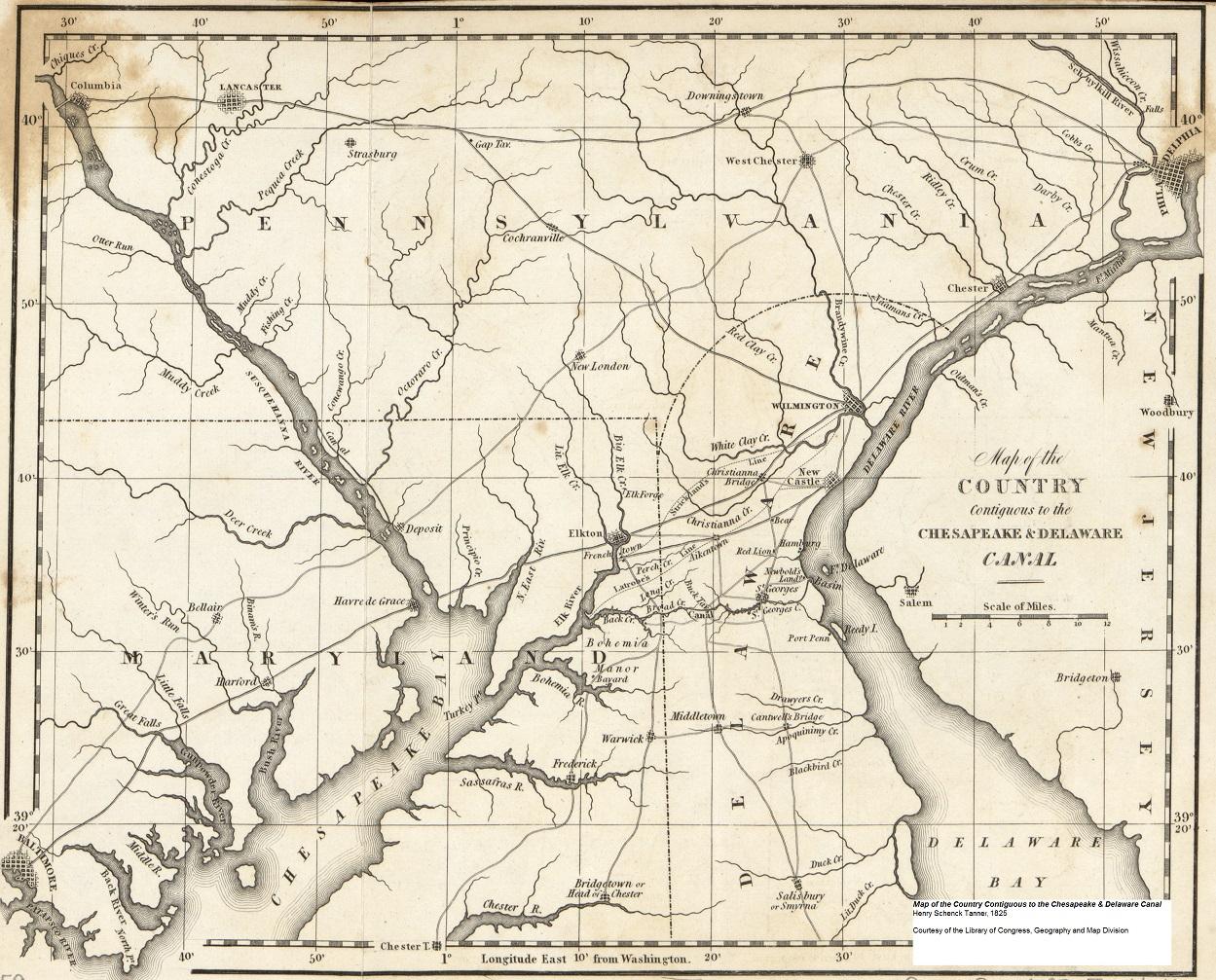

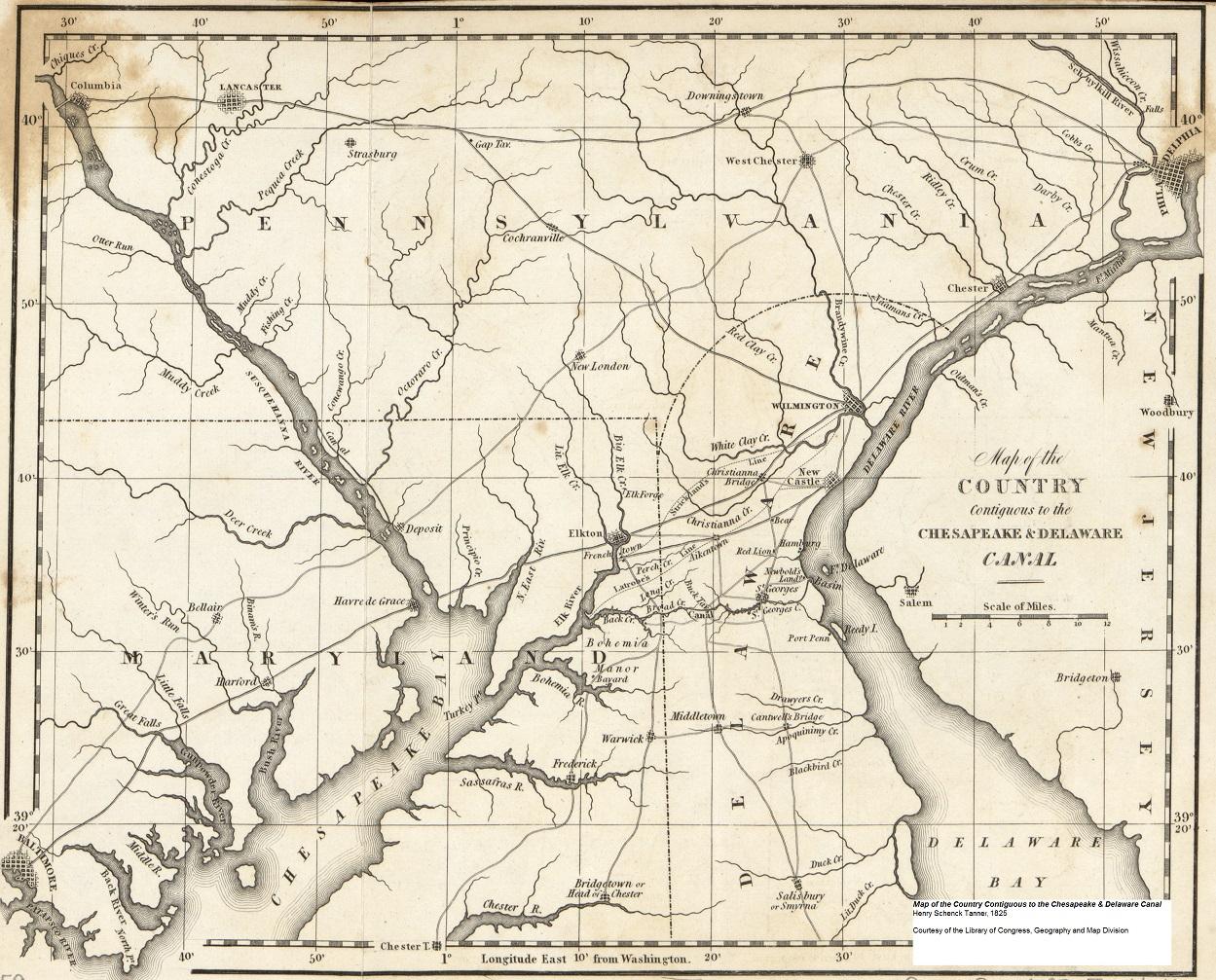

The most revolutionary changes of this time came through the development of new travel infrastructure and modes of transportation. New travel technologies included steamboats, canals and railroads. New Castle and the surrounding area enjoyed some of the earliest examples of these technologies including the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal and the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad.

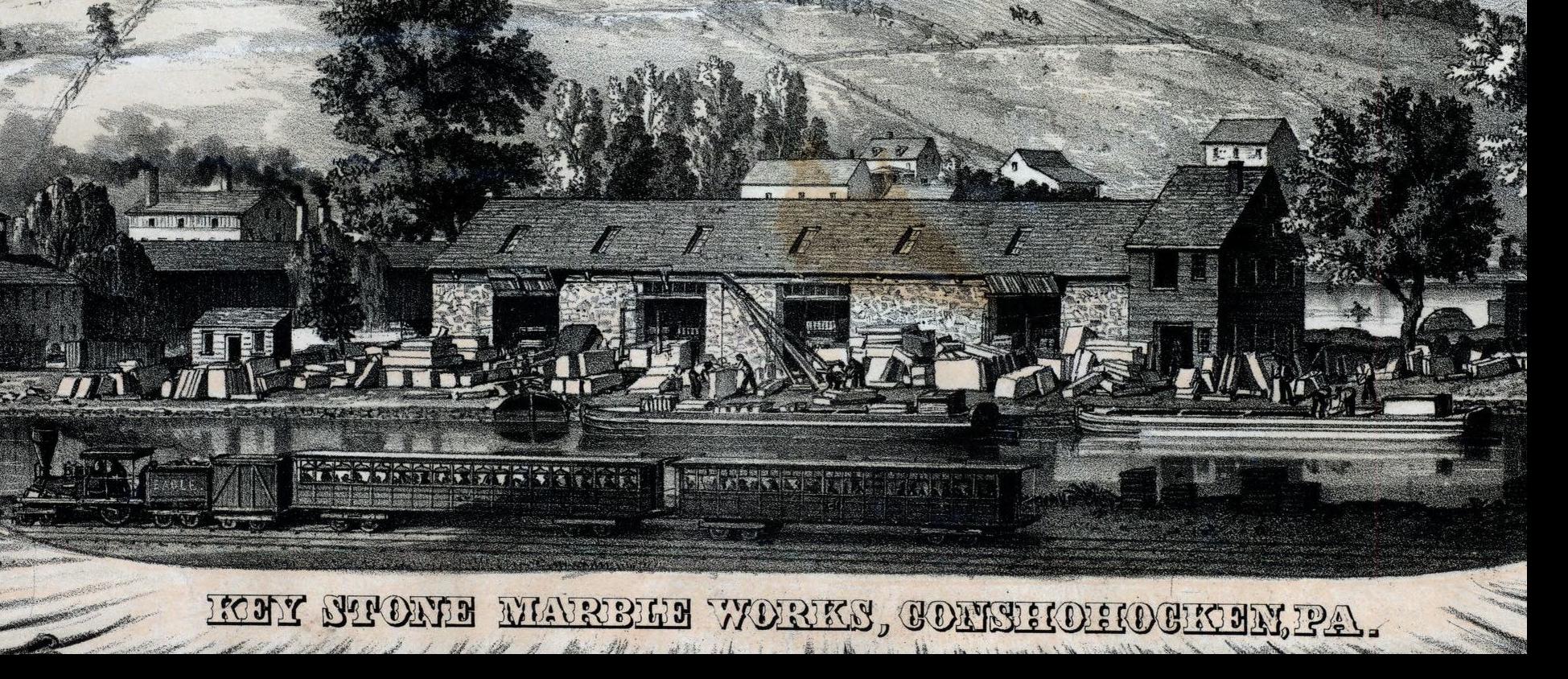

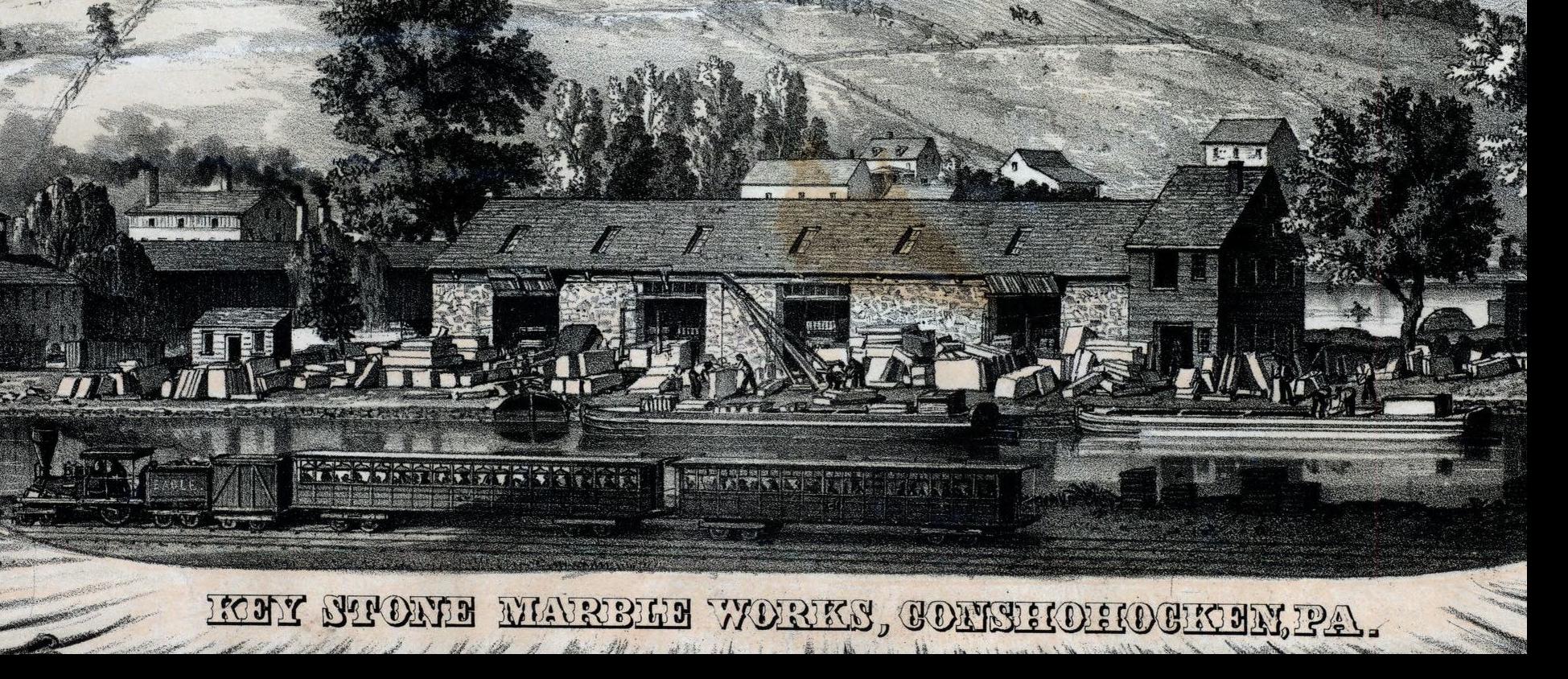

Beginning in the 1790s, a canal network began to develop in the United States The most famous of these early canals was the 350-mile Erie Canal that connected New York City with Buffalo. The Chesapeake & Delaware Canal opened in 1829. The early canals were tow-path canals where canal boats were pulled by mules that walked along the bank of the canal. The mules were aided by polemen on the boats. The canal system dramatically reduced the cost of shipping goods compared to land routes.

Laborers

this

at

marble works in Pennsylvania are shown unloading canal boats while a steam passenger train passes by.

S F Jacoby and Company Importers and Dealers in Foreign and Domestic Marble in All Their Varieties J K and M Freedley Dealers in American Marble By William H Rease, 1850 Library Company of Philadelphia

TheChesapeake&DelawareCanal

The idea of a canal crossing the Delmarva Peninsula connecting the Chesapeake Bay with the Delaware River was first developed by Johann Rising, governor of New Sweden in 1654. The idea was supported by Maryland landowner Augustine Herman of Bohemia Manor, who would have benefited from a cross-peninsular waterway. But the idea did not gain traction until the late 18th century.

By the late 1700s, the lands surround the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries were producing a great deal of agricultural products that were in demand by cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore. Because it was easier to deliver products to Baltimore, Philadelphia was losing what was becoming a regional trade war. A canal to the Delaware River would aid Philadelphia immensely. In 1786, Delaware appointed a commission to investigate the feasibility of constructing a canal, and some work ensued, including a survey of the surrounding area conducted by Benjamin Latrobe, and the attempted construction of a feeder canal from the Elk River which was abandoned in 1805.

Finally in 1819, The Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Company, with Delaware’s Chief Justice Kensey Johns of New Castle as president, was able to get the project moving by securing funding, deciding upon a route, and beginning construction. The Chesapeake & Delaware (C & D) Canal’s construction occurred during a boom in canal construction nationally. The canal era in the United States can be traced to the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825. The canal was completed in 1829 with a total length of slightly over 13.5 miles. The C & D Canal opened on October 17, 1829. When it opened the C & D Canal relied on horses or mules walking on “towpaths” alongside the canal to pull barges, schooners, and other vessels through the canal. The canal was only 10 feet deep and 66 feet wide at the waterline (36 feet wide at the channel bottom). Steam powered waterwheels operated the locks on the canal. As steam power made larger ships more common, the canal’s locks proved to be too restrictive to handle them, and traffic began to drop off. The canal lost traffic to the quickly developing railroads, including the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad which opened in 1832. The last remaining lock from the canals original configuration may be seen today in Delaware City, Delaware.

The Federal government purchased the C&D Canal in 1919, and today the canal, along with the six bridges that cross it, are maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The canal is now 450 feet wide and 35 feet deep. It is one of the busiest canals in the country with traffic estimates as high as 25,000 vessels per year.

ARevolutioninTravel

Steam power later revolutionized both water and land travel, first with the emergence of steamboats and later railroads utilizing steam engines. Steamboats reduced water travel time on long journeys from months to days or a week. Railroads cut land travel times by as much as 85 percent along some routes. These technologies moved both people and things more easily, more quickly and more economically than ever before.

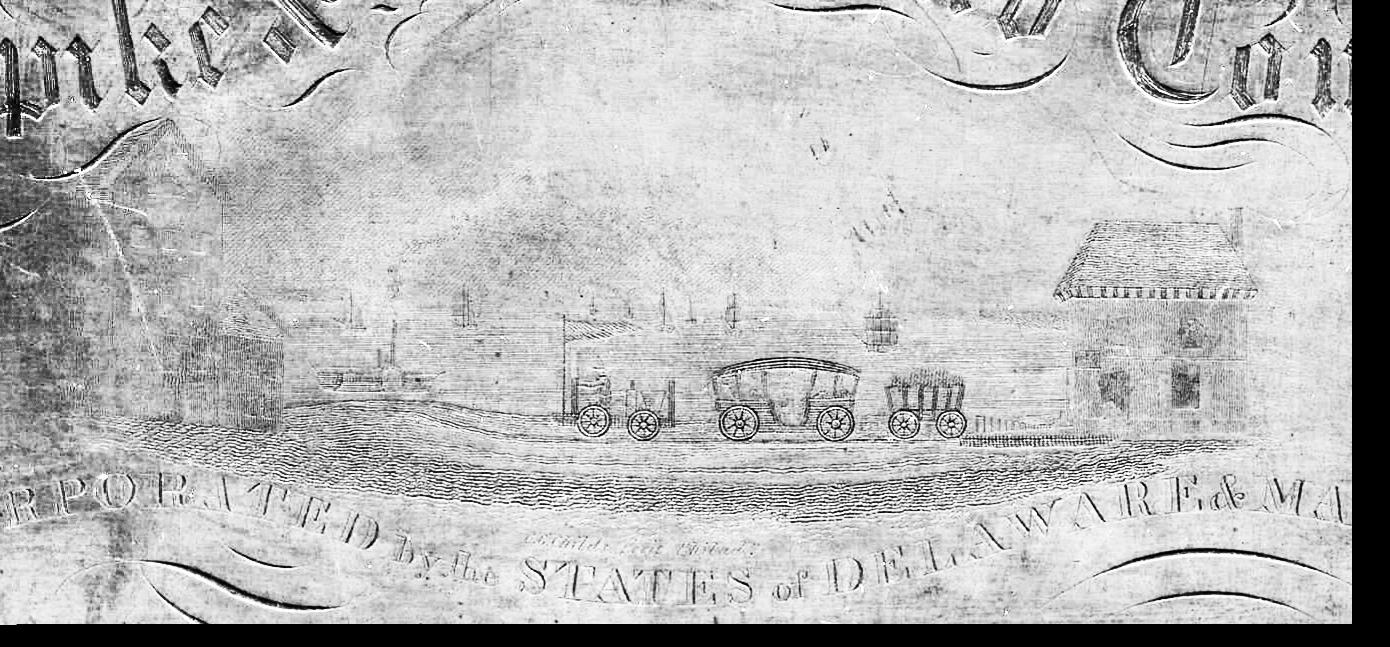

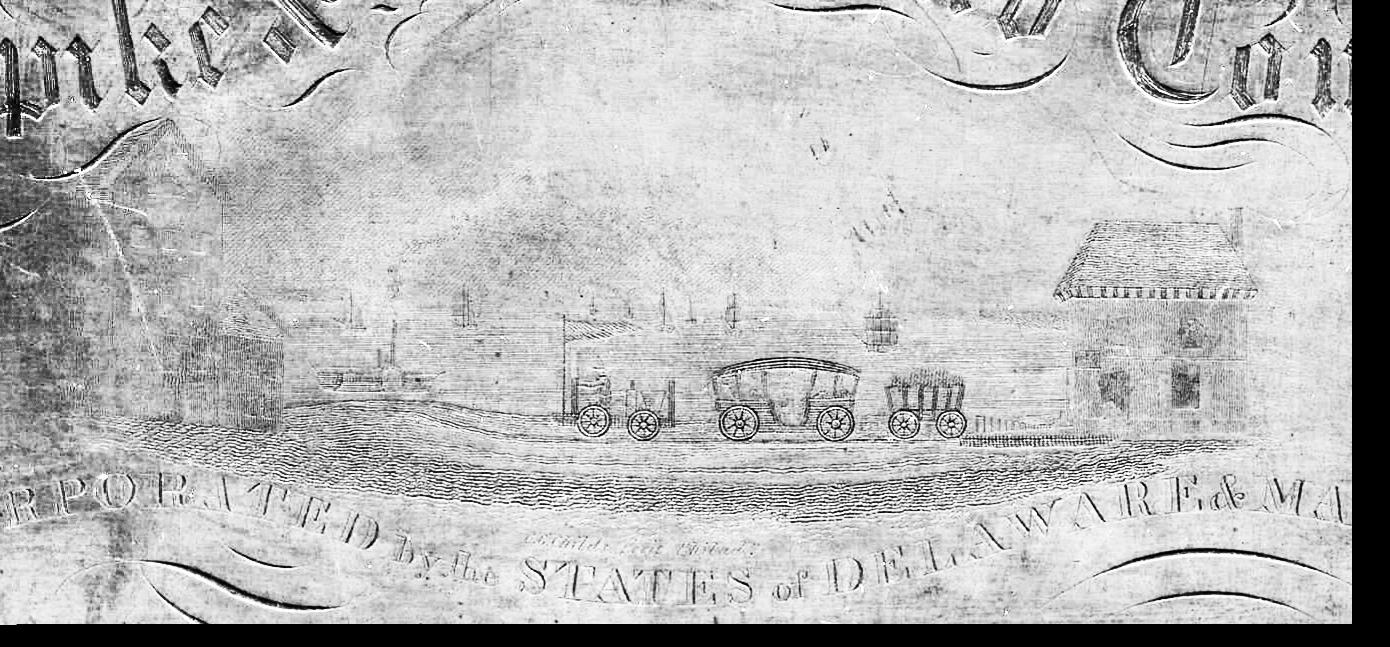

America’s first working steam locomotive was built by John Stevens of New Jersey in 1825 The B&O Railroad broke ground July 4, 1828 Cars were initially pulled along the railroad tracks by horses, but the horses were quickly replaced by steam engines. The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad evolved from the earlier New Castle & Frenchtown Turnpike Company which opened in 1815. The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad opened for operations in 1831.

Less dramatic, but perhaps more important, were the extension of road networks and the increased availability of wheeled vehicles to the general populace As a result, the populace began relocating around the country As a largely agrarian society this movement was usually from one rural community to another, but sometimes families moved from a rural to an urban area. Even within cities people changes residences with surprising frequency.

As large road systems continued to expand and develop, more and more people began to move west to take advantage of new opportunities in a new land Groups of families often traveled together, sleeping beneath their wagons along roads without formal accommodations and cooking in the open air Accidents occurred on occasion with an overturned wagon or stagecoach not only causing injury, but also the destruction of much-needed household goods like crockery and furniture.

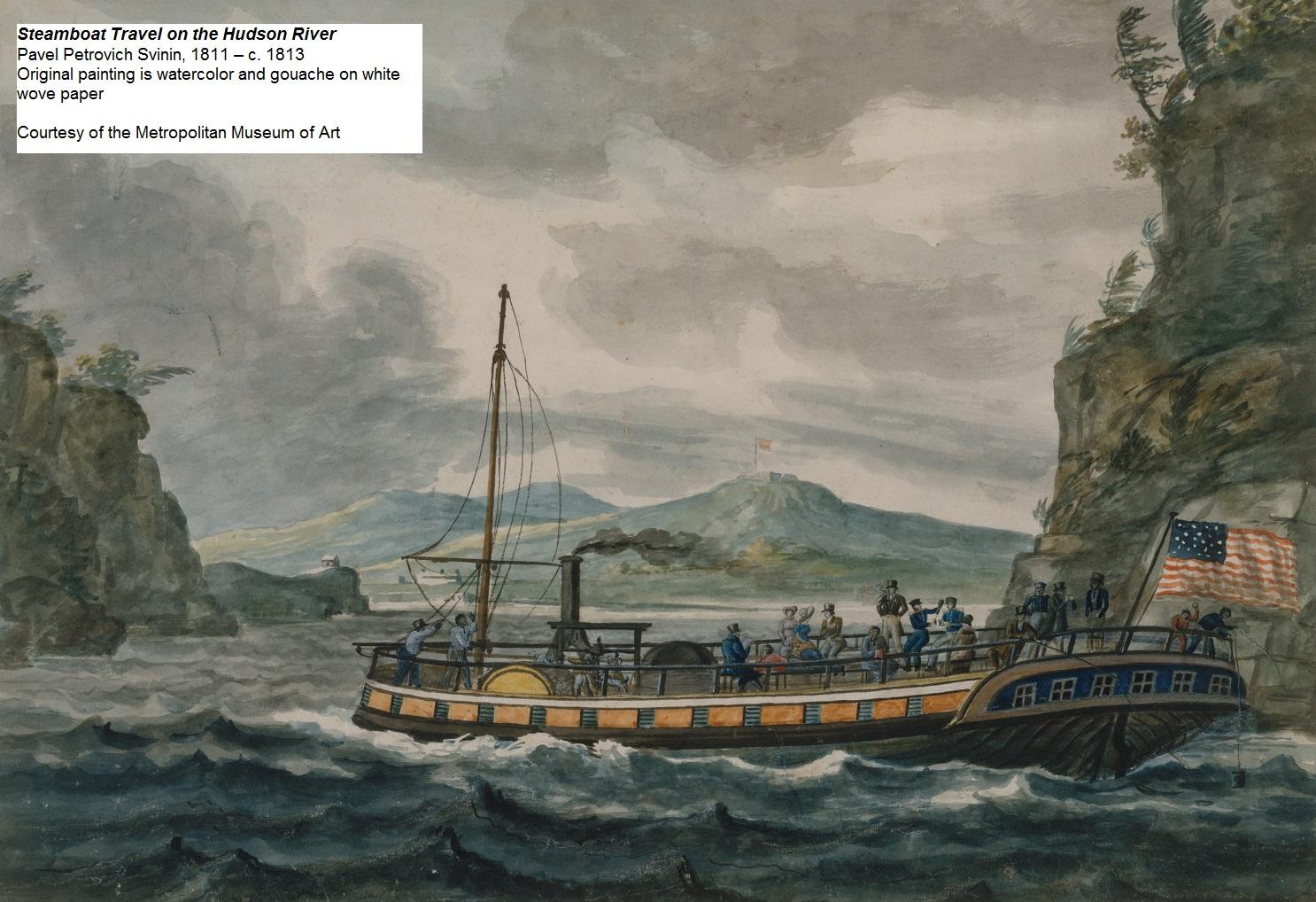

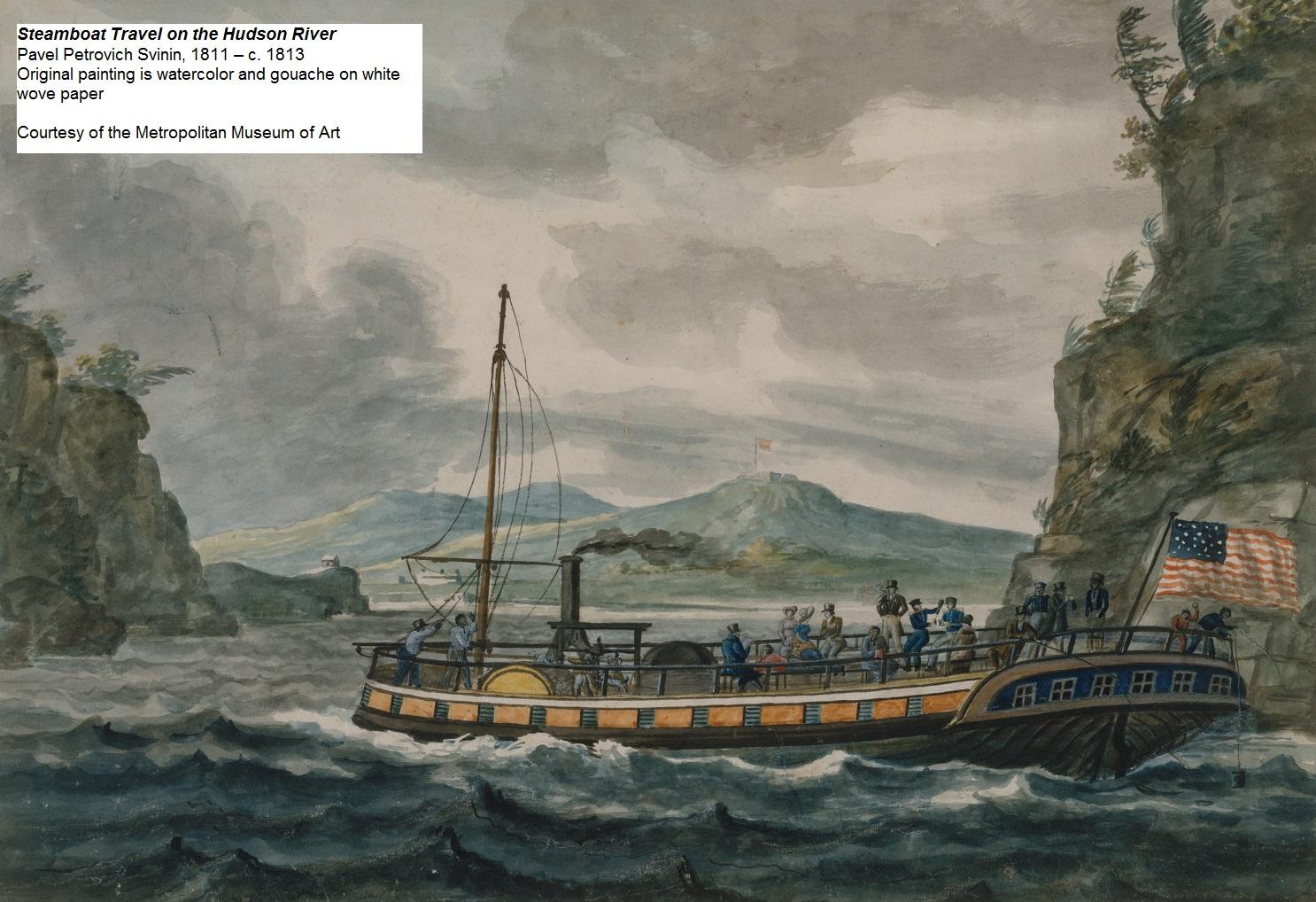

Steamboats

Water travel was always important in early America, but relied on either human, animal, or wind power for propulsion. That changed in the late 18th century with the invention of the steamboat. The first man to build a steamboat in the United States was John Fitch. In 1787, he successfully launched his 45-foot steamboat on the Delaware River ushering in a new era of travel. For much of the next century steamboats became the preferred method of travel on the nation’s rivers, canals, and coastal waterways

Steamboats operated by a steam engine that turned a paddlewheel which propelled the vessel through the water. If the paddlewheel was located on the side of the hull, the steamboat was referred to as a “sidewheeler;” if located on the back it was referred to as a “sternwheeler.”

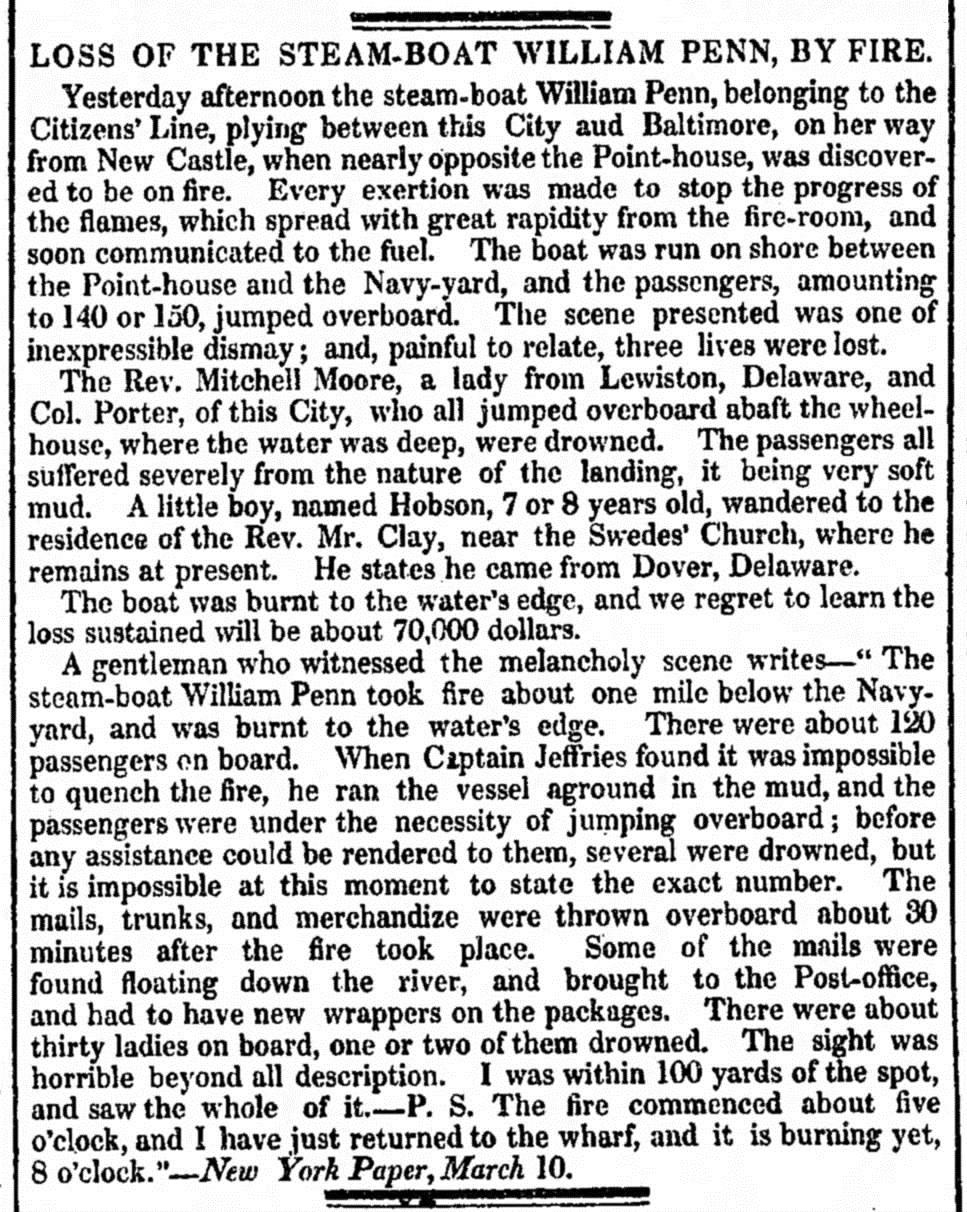

Steamboat travel could be risky. Boilers that created the steam necessary for power could fail and potentially explode. Explosions were a relatively common occurrence particularly on Western steamboats which used high pressure engines Other hazards included inclement weather, the risk of fire caused by hot fireboxes, sparks and cinders as well as potential damage caused by debris floating in the water.

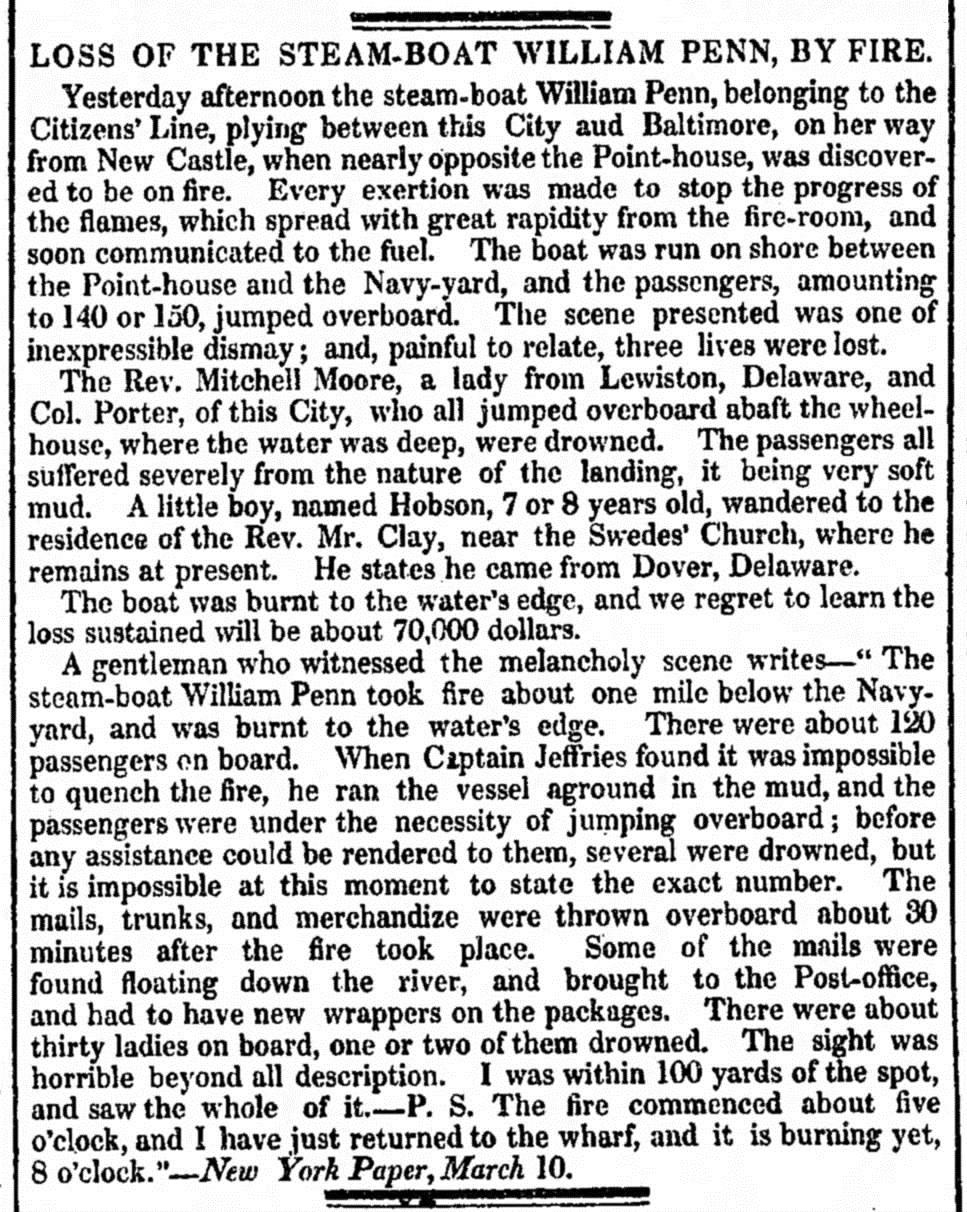

In 1834, the steamboat William Penn was travelling from New Castle to Philadelphia when it caught fire about 5 o’clock in the afternoon. The flames started in the fireroom and spread rapidly toward the ship’s supply of fuel. The ship had to be run aground about one mile south of the Navy Yard so that its approximately 150 passengers could jump overboard Several people drowned trying to escape including a woman from Lewes, Delaware

Steamboat travel was eventually supplanted by the railroads which were faster, more dependable, safer, and operated on a more regular schedule. Even so, steamboats remained in use after 1900. By the middle of the 20th century, widespread use of automobiles and trucks coupled with a well-developed road system ended the era of the steamboat for good.

on the 22d of September , 1798, went on board, and bade adieu to Philadelphia…The vessel having hauled out into the stream, we weighed with a fair wind, and shaped our course down the serpentine, but beautiful river of the Delaware. Our cabin was elegant, and the fare delicious. I observed the Doctor's eyes brighten at the first dinner we made on board, who expressed to me a hope that we might be a month on the passage, as he wished to eat out the money the captain had charged him. The first night the man at the helm fell asleep, and the tide hove the vessel into a cornfield, opposite Wilmington ; so that when we went upon deck in the morning, we found our situation quite pastoral. We floated again with the flood-tide, and at noon let go our anchor before Newcastle.

John Davis, 1798

ARevolutioninTravel

Steam power later revolutionized both water and land travel, first with the emergence of steamboats and later railroads utilizing steam engines. Steamboats reduced water travel time on long journeys from months to days or a week. Railroads cut land travel times by as much as 85 percent along some routes. These technologies moved both people and things more easily, more quickly and more economically than ever before.

America’s first working steam locomotive was built by John Stevens of New Jersey in 1825 The B&O Railroad broke ground July 4, 1828 Cars were initially pulled along the railroad tracks by horses, but the horses were quickly replaced by steam engines. The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad evolved from the earlier New Castle & Frenchtown Turnpike Company which opened in 1815. The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad opened for operations in 1831.

Less dramatic, but perhaps more important, were the extension of road networks and the increased availability of wheeled vehicles to the general populace As a result, the populace began relocating around the country As a largely agrarian society this movement was usually from one rural community to another, but sometimes families moved from a rural to an urban area. Even within cities people changes residences with surprising frequency.

As large road systems continued to expand and develop, more and more people began to move west to take advantage of new opportunities in a new land Groups of families often traveled together, sleeping beneath their wagons along roads without formal accommodations and cooking in the open air Accidents occurred on occasion with an overturned wagon or stagecoach not only causing injury, but also the destruction of much-needed household goods like crockery and furniture.

It was then two or three o'clock Wednesday morning, the 8th of May. I came to the portion of the road that had been cut through a very high hill, called the "deep cut," which was in a curve, or which formed a curve; when I had got about mid-way of this curve I heard a rumbling sound that seemed to me like thunder; it was very dark, and I was afraid that we were to have a storm; but this r umbling kept on and did not cease as thunder does, until at last my hair on my head began to rise; I thought the world was coming to the end. I flew around and asked myself, "what is it?" At last it came so near to me it seemed as if I could feel the earth shake from under me, till at last the engine came around the curve. I got sight of the fire and the smoke; said I, "it's the devil, it's the devil!" It was the first engine I had ever seen or heard of; I did not know there was anything of the kind in the world, and being in the night, made it seem a great deal worse than it was; I thought my last days had come; I shook from head to foot as the monster came rushing on towards me. The bank was very steep near where I was standing; a voice says to me, "fly up the bank;" I made a desperate effort, and by the aid of the bushes and trees which I grasped, I reached the top of the bank, where there was a fence; I rolled over the fence and fell to the ground, and the last words I remember saying were, that "the devil is about to burn me up, farewell! farewell!" After uttering these words I fainted, or as I expressed it, I lost myself.

I do not know how long I lay there, but when I had recovered, (or came to myself), the devil had gone. Oh! how my heart did throb; I thought the patrollers were after me on horseback. After I had gathered strength enough I got up and sat there thinking what to do; I first thought I would go off to the woods somewhere and hide myself till the next night, and then pursue my journey onward; but then I thought that would not do, for my enemies, who were pursuing me, would overtake and capture me. So I made up my mind that I would not lo se any more time than was necessary; hence I crawled down the bank and started on with trembling steps, expecting every moment that that monster would be coming back to look for me.

Thus between hope, and fear, and doubt, I continued on foot till at last the day dawned and the sun had just began to rise. When the sun had risen as high as the tops of the trees, the monster all at once was coming back to meet me; I said to myself, "it is no use to run, I had just as well stand and make the best of it," thinking I would make the best bargain that I could with his majesty. Onward he came, with smoke and fire flying, and as he drew near to me, I exclaimed to myself, "why! what a monster's head he has on to him." Oh!” said I, "look at his tushes, I am a goner;" I looked again, saying to myself, "look at the wagons he has tied to him." Thinks I, "they are the wagons that he carries the souls to hell with." I looked through the windows to see if I could see any black people that he was carrying, but I did not see one, nothing but white people. Then I thought it was not black people that he was after, but only the whites, and I did not care how many of them he took. He went by me, like a flash; I expected every moment that he would stop and bid me come aboard, (for I had been a great hand to abuse the old gentleman; when at home I use to preach against him), but he did not, so I thought that he was going so fast he could not stop. He was soon out of sight, and I for the first time took a long breath.

James L Smith’s description of his first encounter with a locomotive on the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad in 1838.

Railroads

In the 19th century, rail travel emerged to become a great improvement over stagecoaches and other means of land travel, and eventually, even water travel. The first commercial railroad was the Granite Railway in Quincy, Massachusetts which operated by 1826, and the first railroad for passenger and freight service in the United States was the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The B & O was chartered in 1827 and started operating in 1830. In the 1820s and 1830s, railroad construction in the U S began at a fast pace with over 3,000 miles of track laid by 1840 Once established, railroads became the most efficient and reliable means of transportation for freight and passengers over both short and long distances.

With fixed routes, railroads worked in conjunction with other transportation companies like steamboat lines and stagecoach companies to move travelers on a complete journey. As travelers changed from one mode of transportation to another, layovers were inevitable as arrival and departure times were not closely coordinated Although Britain used “Standard Time” by 1847, it was not followed in North America until 1883 as a result of railroad companies formally adopting it

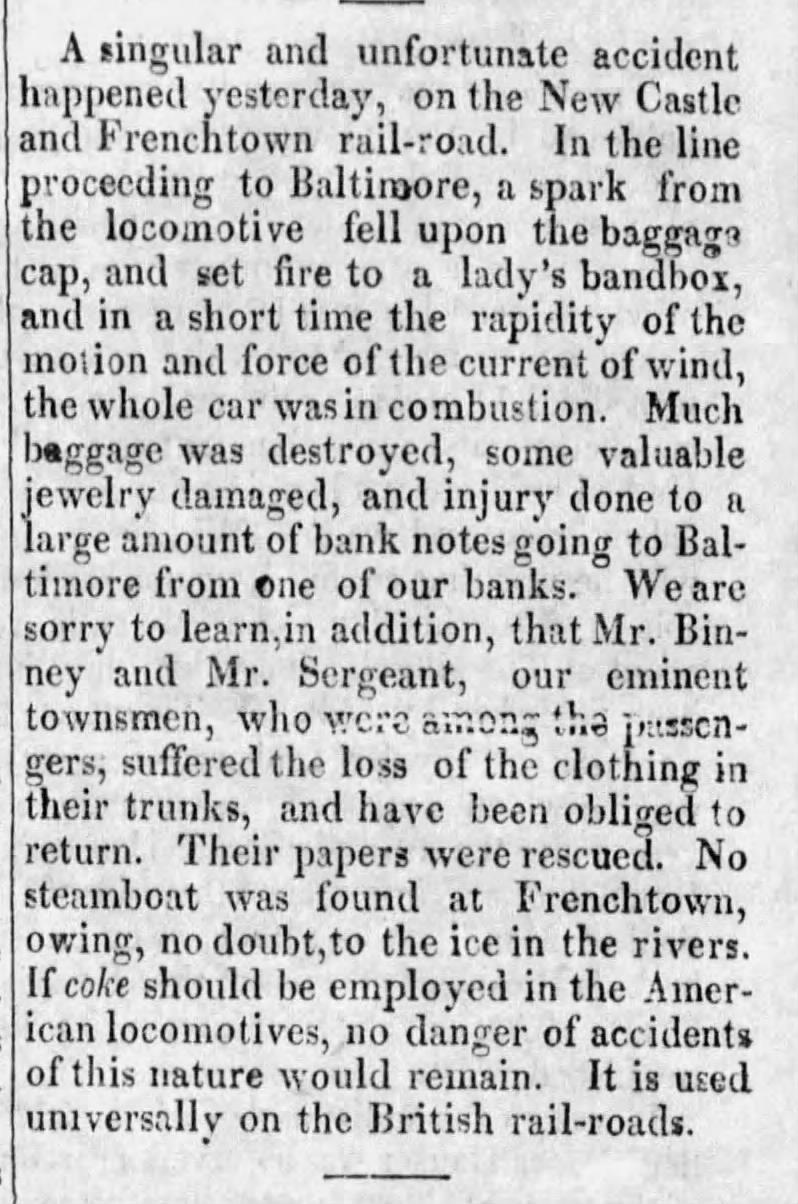

Railroad travel was certainly not without discomfort and risks. At first railroad passenger cars were built like stagecoaches with the same exposure to the elements. Traveling at faster speeds, railroads initially could be frightening to ride upon, though that certainly changed as people became accustomed to them Early locomotives burned fuel to heat their boilers Smoke, sparks, and cinders bellowed from their chimneys often directly onto passengers riding in the cars that followed At best unpleasant, and sometimes dangerous, railroads tried to address this issue with changes in chimney design.

While not likely to explode in the manner of boilers on steam engines, passengers could suffer injury due to derailment or collisions. Livestock, notably cows, wandered on to the tracks and could cause a derailment. There was also danger brought on by negligence and deferred maintenance of equipment, which was new and unfamiliar to the companies operating railroads However, travelers were generally willing to assume some risks in exchange for improvements in the speed and scale of transportation that was increasingly available to them.

TheNewCastle &FrenchtownRailroad

The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad began service in February of 1832. The line ran 16.5 miles from New Castle to Frenchtown on the Elk River in Maryland. The track ran parallel to the existing New Castle & Frenchtown Turnpike. From February through August horses were used to pull carriages along the tracks The carriages were basically modified stagecoaches built in Baltimore A single horse pulled each carriage, but the horses were changed frequently so they did not tire This allowed travel at about 10 miles per hour - a great improvement in speed and comfort over road travel. There were, however, some issues with the horses as they adjusted to the new mode of travel. There were accidents when horses fell, were overloaded, or became panicked. In most cases there were no serious injuries to passengers.

In September the first steam locomotives were successfully introduced on the railroad The first locomotive on the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad was made in England and named the “Delaware ” Upon arrival in America, it was quickly discovered that the wooden-spoked wheels that worked well under lesser stress in England did not hold up well here. Wheels were quickly replaced with iron-spoked wheels. Eventually, the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad purchased locomotives made in New Castle by the New Castle Manufacturing Company, which opened for business in 1835. The first locomotives reached operating speeds of 10 to 12 miles hour – about the same as the horses However, the locomotive could pull multiple carriages whereas the horse could only pull one The locomotive ran as fast as 30 miles per hour in tests, but that was deemed unsafe for daily trips.

In 1835, Davy Crockett took his first-ever train ride aboard the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad. He described it in his journal: Our passage down the Chesapeake Bay was very pleasant; and in a very short run we came to the place where we were to get on board of the railroad cars This was a clean new sight to me; about a dozen big stages hung on to one machine, and to start up hill After a good deal of fuss we all got seated, and moved slowly off; the engine wheezing as if she had the tizzick. By-and-by she began to take short breaths, and away we went with a blue streak after us. The whole distance is seventeen miles, and it was run in fifty-five minutes.

TheNewCastle &FrenchtownRailroad

The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad, like most early railroads in the U.S., was originally constructed with wooden stringers laid atop rectangular sleeper stones (and sometimes oak blocks). A flat iron strip was attached to the top of the wood stringer. This provided a smooth surface for the train to run on – at least initially Over time the flat iron strips could loosen and one end might pop up from the wooden stringer creating what came to be known as a “snakehead ” Snake-heads were dangerous and could derail a train or pierce the wooden floor of a passenger car as it passed over it. Another issue that arose is that the sleepers spread apart under the weight of locomotives. Eventually, the complete railroad needed to be rebuilt using iron "U" or "bridge" rail and wooden ties to maintain a consistent distance between the rails (known as “standard gauge”).

In 1837, a second parallel set of tracks was constructed to allow two trains to run simultaneously without delays caused by siding This helped improve the service of the railroad, but it could not save it from a new competitor By the end of the 1830s, the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad Company offered faster, better and more direct service than could be obtained on the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad and was taking business away from its smaller neighbor. The New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad was purchased and most of its lines eventually used by the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad Company

Detail of printing plate for stock certificates of the New Castle & Frenchtown Turnpike & Railroad Company. Collection of New Castle Historical Society.

Taverns,Inns&Hotels

In the 17th and early 18th century, it was common practice for travelers to approach private residences to ask for accommodation while traveling. Due to the expense and inconvenience this practice began to wane in the 18th century as taverns developed to provide this service.

A tavern was usually referred to as a “Public House of Entertainment” in the 18th and early 19th centuries The “entertainment” provided to both travelers and local citizens included alcoholic beverages, food, overnight accommodations, and stabling services A person did not have to be traveling very far to require the services of a tavern. Any trip more than about 10 miles likely required a stop, sometimes overnight, at a tavern.

Taverns were privately owned and operated businesses that were licensed by the colonial or state governments to sell a variety of alcoholic beverages. Although they were private businesses, the government set the rates that tavern-keepers could charge patrons for drinks, food, rooms, stabling, and fodder for animals

Throughout the 17th and most of the 18th century, water provided the easiest and quickest means of transportation in America. Land travel was slow, and at times, hazardous. Uncertain weather often forced travelers to seek shelter. Manageable distances separated one tavern from the next so that travelers could stop when necessary. Taverns were often located along busy roads, at crossroads, at ports and ferry landings

With the advent of stagecoaches late in the 18th century and eventually railroads in the 19th century, travel became cheaper, easier, and faster. More Americans began traveling, and this trend was very beneficial to businesses, like taverns, which catered to travelers’ needs. Tavern-keepers developed relationships with stagecoach, railroad and steamboat lines that helped provide regular business for the tavern.

The tavern experience, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, was dominated by men While women both worked in and owned taverns, they rarely patronized them Part of the reason for this was that women traveled infrequently. When they did it was with a trusted male companion.

The transient clientele of taverns, in port cities and towns especially, included sailors, laborers, servants, apprentices, slaves, and prostitutes.

The accommodations at the taverns, by which name they call all inns, &c. are very indifferent in Philadelphia, as indeed they are, with a very few exceptions, throughout the country. The mode of conducting them is nearly the same every where The traveller is shewn, on arrival, into a room which is common to every person in the house, and which is generally the one set apart for breakfast, dinner, and supper. All the strangers that happen to be in the house sit down to these meals promiscuously, and, excepting in the large towns, the family of the house also forms a part of the company…If a single bed-room can be procured, more ought not to be looked for; but it is not always that even this is to be had, and those who travel through the country must often submit to be crammed into rooms where there is scarcely sufficient space to walk between the beds…

Isaac Weld, 1795-1797

Tuesday, June 5th.

I took horse a little after five in the morning, and after a solitary ride thro' stony, unequal road, where the country people stared at me like sheep when I inquired of them the way, I arrived at Newcastle, upon Delaware, at nine o'clock in ye morning and baited my horses at one Curtis's [Jehu Curtis’s], at the sign of the Indian King, a good house of entertainment.

Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744

the 28th. [July] from Mr. Chews to New Castle on the Delawar. this is a prety town Consisting of about 500 Dwelling houses. it is looked upon as the next to philadelphia In the province. it is about 30 from this last, S. W., on the north side of said river. there was two Kings Fregates of[f] the town to visit the vessels going in and out therby to hinder foreign trade. from New castle to wilmington, 6 miles. crossed the fery at Christeen river. This is a small but very well situated litle town, on the side of sd. river. large ships Can Come up this river to the town.38 it is about 1 mile Dist. from the Bay, on which the town has a fine prospect, being on the side of a hill. this place is so near the City that there is but little trade Caryed on. tavern Keeping is the best business that is Caryed on in all those small towns, therfore are they well stocked with taverns. here I lay.

A French Traveller in the Colonies, 1765

Taverns,Inns&Hotels

Food in taverns was generally simple fare, often being boiled or broiled on the kitchen hearth. In rural taverns, it was common for patrons to join the tavernkeeper’s family and share their meal. In urban areas, meals were created especially for the patrons, and often included meat, seafood, fowl, cured or pickled meats, cheese, seasonal vegetables, and bread.

Food was sometimes served in communal dishes and shared amongst the customers promoting conversation and personal interaction Some taverns, especially in cities, offered both public and private dining rooms City taverns also hosted large private events and served food in courses with drinks to accompany each course.