10

North Shore surfers dream of autumn gales

MAP FEATURE:

Get Spooked 13

Fall fun with a side of shivers

Bowhunting 101 18

What Sank the Fitz? 26

New theory makes waves

Hike into History 12

The Bird Dog Diaries 9

Ready, Set, Snow! 19

Outdoor Gift Guide 22

Hasta La Vista, Manitoba 20

The Accidental Gardener 23

Book Reviews 24

Calendar & Events 7

Campfire

Stories 27

Canadian Trails 20

Classifieds 25

Miss Guided 17

North Notes 5 Northern Sky 17 Product Reviews 25 Strange Tales 26 Through My Lens 16 Waterfalls 15

At this time of year, one thing is certain. Winter is coming. Before it arrives, get outside and have some fall fun. Hunters, hikers, paddlers and other outdoor lovers try to squeeze as much outdoor quality time from October and November as possible. They know it won’t be long before cold and snow brings autumn to an end.

You can celebrate autumn in many ways. Gregory P. Isaacson gives us an inside look into the Lake Superior surfing scene, where the gales of November are relished for the waves they produce. For mariners, the same winds can be deadly, as Elle Andra-Warner recounts her story about how the Edmund

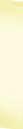

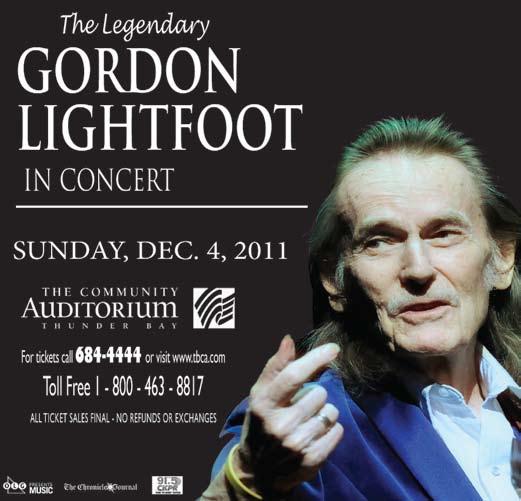

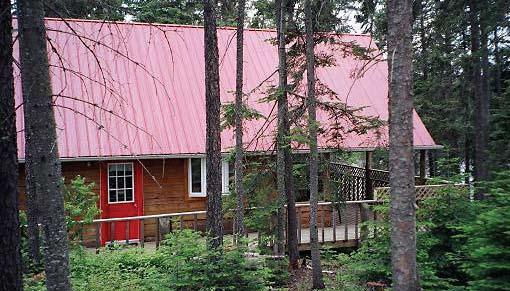

About our cover:

Surfers brave wind and snow for North Shore waves.

| ANNA MARTINEAU-MERRITT

Fitzgerald went down. If tales of sunken ships make you shiver, be sure to read the story about spooky things to do in the Northern Wilds. To keep the spooks away, don’t miss Joan Farnam’s garlic-growing wisdom. Kate Watson leads us on some hikes to hidden history.

Dog lovers won’t want to miss Kevin Bovee’s recount of a summer spent training his yellow Lab puppy. And moose fans will enjoy Iron Mike Hillman’s historic tale of a moose-drawn sleigh. Mike Furtman introduces us to Bert, the bear who sleeps on his deck. Gord Ellis takes us duck hunting. If you just can’t wait for winter, be sure to check out our holiday gift guide.

New in this issue is Miss Guided, a column by our resident adventurer and Managing Editor, Shelby Gonzalez, who will show you how to find fun adventures in the Northern Wilds. Also, we announce with regrets that sales representative Calie Vannet is leaving Northern Wilds to take a new position in the southwestern United States. We wish her the best in her new adventure.

—Shawn Perich and Amber Pratt

Maybe it’s something in the water. This summer, two separate parties of Minnesota 20-somethings completed canoe expeditions to Hudson Bay.

The “Hudson Bay Bound” expedition comprised Natalie Warren and Ann Raiho—and, along the way, a puppy named Myhan (after the Cree word for wolf). The two women met at YMCA Camp Menogyn. Sponsored by Stone Harbor Wilderness Supply in Grand Marais, they paddled from Minneapolis to Hudson Bay, a journey of 2,250 miles that included urban waterways and wild Arctic rivers that wound through polar bear territory. They are the first women to retrace the journey chronicled in the famous book Canoeing with the Cree. See www.hudsonbaybound.com for more information.

The “Voyageur’s Hudson Bay Expedition” comprised four young men—Adam Maxwell, Andrew Spaeth, Mike Swenson and Will Tanner—and was inspired by a longing for adventure and the 50th anniversary of Voyageurs Canoe Outfitters at the end of the Gunfl Trail. They traveled from Grand Portage to York Factory on the banks of Hudson Bay, a 77-day journey encompassing the Winnipeg, Bloodvein and Gods Rivers. See www.voyageurhudsonbayexpedition. com for more information.

What do you think it is?

On Sept. 4, Marco Manzo III went for a swim in Lake Saganaga and encountered a flotilla of dime-sized translucent globules trailing tiny tentacles. He scooped two of the mystery creatures into a jar and brought them to the Minnesota DNR and the Ontario MNR, where they were identified as freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi) Brian Larsen of the Cook County News-Herald broke the story.

Manzo and his sister, Alesha, found the jellyfish on both the U.S. and Canadian sides of the lake. Never fear, swimmers—these tiny creatures aren’t equipped to sting people.

Last year, a fisheries biologist spotted a fleet of thousands of jellyfish in Namakan Lake in Voyageurs National Park. Jellyfish were also spotted in Crab Lake and Banadad Lake in the BWCA and Long Lake near Cotton. Unusually hot summers may be responsible for freshwater jellyfish “blooms.”

Here, kitty, kitty, kitty. When a Hovland man set out a trail camera during the week of Aug. 29, he was hoping to catch snapshots of bears. Instead, one shot captured the hind end of a slinking critter with a long, upward-arced tail—a likely characteristic of a cougar.

The image comes on the heels of other cougar sightings in the area. Someone saw a long-tailed big cat slink across the road. Someone else spotted tracks. Another heard hair-raising screams in the forest.

Cougar sightings are not unusual in the Northern Wilds, but are rarely verified by officials.

Share your strange sightings! Email editor@northernwilds.com

In August, the Minnesota DNR released a draft moose management plan for public comment. Directed by the State Legislature to create a

moose management plan in 2008 in response to the collapse of the northwest Minnesota herd and troubling decline in the northeast population, the DNR first convened a citizen’s committee to come up with management recommendations and then spent over two years writing the plan. During this time, the DNR’s moose population estimate for the northeast tumbled about 30 percent. The plan sets parameters for eventually closing the state hunting season, supports continued moose research and, within the

Clough Island, a 358-acre wildlife hotspot in the St. Louis River estuary was recently transferred from The Nature Conservancy to the Wisconsin DNR for outdoor recreation

northeast moose range, recommends maintaining the pre-fawn deer population at less than 10 per square mile as well as banning recreational deer feeding. It is no secret Minnesota’s moose are in trouble. In the northwest, where several thousand moose existed in the 1980s, the population is now estimated at less than 100 animals. In the northeast, the population is now estimated at less than 5,000 moose and everyone with historical perspective for the region going back to the 1990s or earlier believes the herd has undergone a significant and ongoing decline. However, after a decade of research by the DNR, tribes and academics, no one has pinpointed the problem.

and conservation efforts. A recovering lake sturgeon population swims in the waters around the island. The transfer will ensure the island’s permanent protection.

“This is a huge step toward achieving the goal of delisting the river as an Area of Concern on the Great Lakes,” said Julene Boe, of the St. Louis River Alliance.

Clough Island (pronounced “cluff ”) sits where the St. Louis River meets Lake Superior, between Duluth and Superior, Wis. Largely undeveloped, Clough Island is a haven for more than 200 species of birds during migration and breeding season. The estuary also harbors native critters like beaver, mink, river otter, muskrat, bear, bobcat and wolf.

The transfer marks the culmination of a years-long collaboration between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the Minnesota and Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources. Local organizations also assisted.

Each year, on the date the Edmund Fitzgerald sank in 1975, the beacon in Split Rock Lighthouse is lit in memorial of the 29 men who lost their lives. The names will be read to the tolling of the ship’s bell at 4:30 p.m. This is the only day when visitors can climb the lighthouse and see the light lit. Learn more at www. mnhs.org/splitrock.

What do you get when Harriet Brewing of Minneapolis comes to Lutsen Mountains? Mountain Mash, a weekend of events celebrating food, music, art and—of course— beer. Events to pick from include a Friday night release party for Rauchfest, Harriet Brewing’s new German-style smoked lager, and a beer pairing dinner at the Moose Mountain summit chalet. Bottoms up! More information at www.eagleridgeatlutsen. com.

The annual celebration of all things moose is back bigger and better this year. Puzzle out the clues in the Moose Medallion Hunt, collect Moose Bucks, attend readings and tours, and keep an eye out for Murray the Moose, who is always happy to pose with visitors for photos. This year’s festival marks the debut of the Moose Tracks Race, a fourblock dash in which you are encouraged to wear all your finest moose apparel. More information at www.grandmarais.com/ moosemadness.

2527

Duluth National Snocross

Snocross fanatics and casual fans alike congregate at Spirit Mountain every year to kick off the winter’s ISOC (International Series of Champions) racing series. The races and displays, including the C.J. Ramstad Memorial Cup, will showcase the talents of the top riders, while an expo will showcase the latest sleds, gear and lifestyle accouterments. More information at www.visitduluth.com/snocross.

OCT. 8 AND 15

No chills to be had at this annual zoo event, just critters, candy and fun. Go trick or treating amongst the animal exhibits. Enjoy the not-haunted hayride. Brave the Haunted Tunnel—if you dare—and look at creepy crawly creatures like reptiles and insects. Compete in the costume contest, or just enjoy your hot dogs and caramel apples while the animals savor pumpkin treats of their own. More information at www.lszoo.org.

SAT 9/24 SAT 11/5

Lake Superior Photography Exhibit Waterfront Gallery, Two Harbors www.waterfront-gallery.com

SAT 10/1

Guided Hike Caribou River Wayside to Cook Co Rd 1. 10 a.m. www.shta.org

SAT 10/1 SUN 10/2

Annual Members Show & Sale Grand Marais Art Colony 9-4 p.m. 218-387-2737

Crossing Borders Tours Artists' Studios along Highway 61, Grand Marais 1-800-388-8698 info@crossingbordersstudiotour.com

SAT 1/1 SUN 10/16

FRI 10/21 THROUGH

THE HOLIDAYS

Juried Photography Johnson Heritage Post, Grand Marais 218-387-2314

FRI 10/2110/23

Moose Madness Grand Marais www.grandmarais.com

Haunted Fort Night Fort

William Historical Park, Thunder Bay 7 p.m. www.fwhp.ca

SAT 10/22

Minnesota Furbearer Opener (North Zone) mink, muskrat, beaver, otter

SAT 10/23 SUN 10/23

Howl-o-Ween The International Wolf Center, Ely www.wolf.org

FRI 11/1820

Midwest Mountaineering Outdoor Adventure Expo Minneapolis www.outdooradventureexpo.com

SAT 11/19

Holiday Bazaar and Quilt Drawing at 2:00 pm Cross River Heritage Center, Schroeder 10:00 a.m.-2:00 p.m. 218-663-7706

Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” begins Bayfront Park, Duluth www.bentleyvilleusa.org

TUE 11/22 SUN 11/27

A North Shore Holiday Cook County www.anorthshoreholiday.com

FRI 11/25 27

FRI 10/28 10/30

Haunted Fort Night Fort

William Historical Park, Thunder Bay 7 p.m. www.fwhp.ca

AMSOIL Duluth

National Snocross Spirit Mountain, Duluth Visitduluth.com/snocross

SAT 11/26

Get Northern Wilds in your email inbox, browse it on your computer, smartphone, or view it on your tablet. Clickable links and a “zoom in” feature make the digital edition convenient and easy to read.

"Wings, Water and Wildflowers" Exhibit of the works of Nancy Seaton and Betty Hemstad. Johnson Heritage Post. 1 p.m.-4 p.m., Wednesday through Sunday. 218-387-2883 • history@boreal.

org

SUN 10/2

North Shore Health Care Golf Tournament Superior National Golf Course 218-387-9076

THU 10/0610/31

Haunted Ship Tour Duluth 218-722-5573

SAT 10/8 AND SAT 10/15

SAT 8

Annual Agate Festival Boulder Lake Enviromental Learning Center, Duluth 1 p.m. – 3:30 p.m.

THUR 10/14, 15, 21, 22, 28,29

www.northernwilds.com

Boo at the Zoo Lake Superior Zoo 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. www.lszoo.org

Haunted Cornfield Gamondale Farm, Thunder Bay www. gammondalefarm.com

FRI 10/1410/16

Mountain Mash /Harriet Brewing Lutsen Mountains www.eagleridgeatlutsen.com

SUN OCT 1622

Wolf Awareness Week International Wolf Center, Ely www.wolf.org

SAT 11/05

Minnesota firearms Deer Opener

THUR 11/10

Split Rock Lighthouse

Beacon Lighting

Split Rock Lighthouse State Park 9-6 p.m. 218-226-6372

THUR 11/1711/20

Winterers Gathering North House Folk School 218-387-9762 www.northhouse.org

Minnesota Muzzleloader Deer Opener Minnesota Trapping-bobcat, fisher and marten

THU 12/1

Pikku Joulu Finnish Pot Luck Finland SAT 12/3

Annual Fiber Guild Holiday Sale 9-2 p.m. art@boreal.org SAT 2/4SUN 2/12 Winter Tracks Family Festival. Cook County www.wintertracks.com

Story and photos by Kevin J. Bovee

Sir Walter Raleigh, our young British Lab, is staring his fi rst hunting season square in the face.

I knew from the start that Raleigh would retrieve because he would pick up just about anything and carry it around for extended periods. He demonstrated his smelling ability by digging through deep snow and matted grass to seize long-dead mice and voles. But we didn’t drive 8hours for a Lab that specialized in dead rodents. Grouse and pheasant are what we have in mind for him.

Training began with retrieving dummies in the yard and then progressed to water retrieves in local ponds or down at Lake Superior. Raleigh will retrieve dummies long after your shoulder is sore from throwing them. The next step was to add distance to the throws, which will help him in marking falls. Another person was needed for this step.

Before we could start that process, though, we decided to have Raleigh neutered. We aren’t in the business of breed-

him very quiet for five to six days, rather impossible for a seven-month-old Labrador, and to keep him out of the water for a couple more weeks. So much for his basic training.

Once healed, land and water retrieves were done twice a day. Mary and I would take turns throwing the dummies with the other person handling the dog. We are lucky that there is a large open field a quick walk from the house. Here again his enthusiasm outlasted ours.

A crucial step in the training process was getting him used to the report of a gun. I searched for an old-fashioned cap gun like we used when we were kids but to no avail. I did fi nd a plastic gun that used ring caps, which worked well.

We started shooting the cap gun when throwing dummies from about 50 yards away and gradually got closer until we could

fi re caps right over his head. Retrieving is what he concentrated on. We then switched to .22-caliber blanks that builders use to drive nails into wood or concrete.

Similar to the cap gun, we started with the blanks from farther away and got closer and closer without any fuss from Raleigh.

The last step in Raleigh’s preparation for the grouse opener is to get a frozen grouse from the freezer, thaw it out and then let him retrieve it while working with the dummies. A friend who found the grouse dead below a picture window donated the grouse to Raleigh’s training late last winter. Little did the grouse know that his life would benefit the growth and potential of a young bird dog.

I will also drag the grouse along our trails and then have Raleigh track the bird until fi nally retrieving it. It’s no dead vole, but he’ll have to make do.

By Gregory P. Isaacson

The fi rst big storm of the season, a powerful nor’easter, was howling down the long surface of western Lake Superior. Powerful waves pummeled the shoreline. I hurried to one of my favorite surf spots. Known as The Rock, it is located at the mouth of the Lester River, just off Highway 61.

Spectators in minivans and SUVs gawked as I unloaded my surfboard. Dressed in a skin-tight 6mm wetsuit that would shield me from the 38-degree water, I must have looked like a creature from some distant planet.

Even after 25 years of surfi ng the big lake, I still get stoked for the fi rst session of the season. I smiled at a bugeyed kid with his face pressed against a backseat window. Then I turned and walked down the trail to the water. Shorebreak churned around my legs as I picked my way along the slippery rocks. I timed the next wave and paddled my freshly waxed board out into the lineup, where my friends were waiting for the next set of waves.

We had been waiting for this storm for months. Like hunters and fishing enthusiasts anticipating opening day, surfers in this region sit out through the fl at summer months, waiting for

Lake Superior to awaken. When I feel the wind switch and watch the cloud patterns change in the sky, I know surf season is on.

Like salmon returning to their spawning grounds, surfers from Thunder Bay to the Twin Cities gravitate to the North Shore in the fall and winter. We huddle around bonfi res, warming up between surf sessions, telling stories and sharing the thrills of catching Superior waves.

The surfi ng season starts around

Labor Day as summer winds down and cooler autumn temperatures fi lter in from the north. This dramatic change in air temperature, along with the powerful force of wind over such a deep, cold body of water, ignites the engine of Lake Superior’s wave machine. The contrasting conditions ripen as autumn temps drop into winter.

To surf Lake Superior with success requires a keen knowledge of weather and the ability to track storms as they arrive. With a seasoned awareness of

the wind and the coastline, you can determine where the best locations are to fi nd perfect waves—that is, waves w ith smooth, clean surfaces in sheltered areas out of the prevailing winds.

The window of surf time can be small, sometimes lasting only a few hours. The fleeting, fickle nature of freshwater waves has surfers ready to brave even the harshest weather conditions.

In the early winter season, for example, north winds roar down from the Artic w ith bitter wind chills and water temperatures that drop near freezing. Winter surf sessions include such highlights as blinding snow squalls, frozen eyebrows, mustaches that drip icicles, and the occasional case of “brain freeze.”

The next set of waves loomed on the horizon. I paddled, placing myself in the perfect position at the peak. I rose to my feet in a single motion. My friends hooted in

enthusiasm as I glided down the smooth, glassy wave face, racing down the line of the cresting wall of water, feeling the longawaited rush of pure fl ight.

Watson

Early settlers and explorers left their mark on the northern landscape, often literally. Here are four hikes that will show you secret traces of the past. Ghosts not included.

Day Hill Trail, Split Rock

Lighthouse State Park

2 miles round trip

On this easy hike with great views

of Split Rock Lighthouse, you’ll fi nd an interesting surprise at the top of the rocky cliff.

There, an ambitious settler was looking to secure a million-dollar Lake Superior view—but it seems the furthest he got was building a stone fi replace and chimney.

An interpretive sign says that the fi replace’s origin is actually unknown, but some believe it was the fi rst step in the creation of Duluth businessman Frank Day’s dream home in the early 1900s.

Unfortunately for him, the stor y goes, construction stopped when his fi ancée called off the wedding.

Whatever the story, it makes an interesting landmark on Day Hill.

Graffiti,

Artist’s Point, Grand Marais 0.1 miles

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, before Highway 61 provided a land route, a ferry carried people and supplies along the North Shore. As people waited for the ferry, they passed the time by leaving their marks in the rocks.

Many visitors to Artist’s Point head straight to the lighthouse and miss these echoes of the past.

Park on Artist’s Point and take the path just past the Coast Guard Station to the break wall. Turn right and hop off the break wall onto the rock on the lake side. Watch your step. You’ll come across many signatures left more than 100 years ago.

Paulson Mine, Kekekabic Trail 3.3 miles (loop)

While the words “abandoned mining town” may call to mind images of Colorado or California, you can fi nd traces of one just over a mile down the Kekekabic Trail. In the late 1800s, a deposit of iron was discovered at this spot near Gunfl int Lake and a minin g operation called Paulson Mine was established. Small villages sprang up to service the site, including Gunfl int City, of which little remains. If you hike in, you’ll fi nd a fenced pit marked “Paulson Mine 1893,” which was a test shaft for the mine. Be careful if you venture off-trail as there are other partially fi lled pits nearby.

When it was fi rst begun, the mine seemed so promising that it served as a stop on the Port Arthur, Duluth and Western railroad that ran from Canada into Minnesota. The Centennial Trail (new in 2009) follows the railroad bed. If you do the loop, you’ll hike 3.3 miles—including part of the Kekekabic Trail—and you’ll see more evidence of the mining operation.

By Shelby Gonzalez

Ah, fall—the all-too-brief interlude between summer and winter. As the days shorten, gardens wither and Arctic w ind starts to blow, we seek comfort in warmth and fellowship. We also festoon our yards with spiderwebs and pumpkins and watch movies designed to scare the pants off us. While it may be tempting to hole up on the couch with apple cider and Night Terror VI and wait for ski season to start, don’t retreat inside just yet. Here are seven ways to get some fresh air and revel in the in-between season.

Shiver your timbers with a spookified “Shanghai Revenge” experience on the ore boat William A. Irvin in Canal Park, Duluth. Tiptoe through the tight corridors and the yawning caverns of the cargo hold, wary of the ghouls that lie in wait. This year the Irvin celebrates its 25th anniversary as a tourist attraction. Before that, this 610-foot vessel spent four decades hauling coal and iron ore throughout the Great Lakes. Use discretion if bringing kids. See www.duluthhauntedship.com for details. Farnorth frights can be had at Haunted Fort Night at Fort W illiam Historical Park in Thunder Bay, which turns into a scary place for a few nights each October. Get your tickets in advance because it sometimes sells out. Ages 10 and up. Details at www.fwhp.ca.

When the moon is bright and the air is still, camp out on the cabin porch with wool blankets and a Thermos full of cocoa. Go out at twilight to watch bats wheel and dart. See the full moon rise on Oct. 11 and Nov. 10. Then listen for owls, which are particularly active and vocal in the autumn months. Alternately, trek the Nocturnal Trail at the Lake Superior Zoo. This permanent exhibit showcases denizens of the darkness, including fruit bats, burrowing owls, and reticulated pythons. The zoo will also host a kid-friendly “Boo at the Zoo” event on Oct. 8 and 15. More information at www.lszoo.org.

Stroll through the woods and keep your eyes on the skeletal trees, looking for “witches’ brooms”—out-of-place bushy growth on otherwise-healthy trees. These features are actually the result of diseases or parasitic plants like dwarf mistletoe, to which black spruce and balsam fi r are particularly prone. Take a ride on the Big Aspen ATV Trail in Aurora or the Red Dot ATV Trail in Silver Bay. Stop for lunch and broom-spotting along the way.

Venture out to Split Rock Lighthouse State Park in Two Harors when the wind shrieks and the waves tower to enjoy the dramatic sight of waves batterin g the cliff—and, just maybe, encounter the ghost of an old lighthouse-keeper. Such a ghost is said to have been spotted there before on stormy nights. On Nov. 10, the lighthouse navigational beacon is lit in honor of the 29 men who lost their lives on the Edmund Fitzgerald. See page 26 for the full story on what sank the famous ship. More information at www.mnhs.org.

Peer into the abyss of Devil’s Kettle Falls—from a safe distance, mind you—at Judge C.R. Magney State Park near Hovland. A complete visitor’s guide to this North Shore enigma is on page 15.

Duluth www.lszoo.org

Walk amongst mossy wooden grave markers over 100 years old in Silver Islet, near Sleeping Giant Provincial Park. Silver Islet was a mining boomtown exploiting an underwater silver vein near a mounded rock feature called Skull Rock. Then, in 1883, the coal needed to keep the pumps running was delivered late. Water surged into the mine, sealing it forever. You can still spot Skull Rock from shore. The town general store was restored and is now open seasonally.

Wander the spook-infested cornfield maze at Gammondale Farm for an experience that will tax both your navigation skills and your nerves. Recommended for ages 5 and over. For kids and grown-ups who don’t relish fright, Gammondale also hosts Pumpkinfest, with activities like scarecrow-making and pumpkin catapulting. More information at www.gammondalefarm.com.

www.dnr.state.mn.us

your spooky photos to editor@northernwilds.com and you could be featured in an upcoming issue.

One mile into the forest, Devil’s Kettle Falls is waiting. Cross the footbridges over a small stream and waterfall. On the east bank the trail turns upstream and rises. If you suffer vertigo, don’t look down. And don’t get too close to the edge—it’s a long fall.

After 17 minutes, you’ll see more waterfalls as the Brule River carves through the canyon like a knife. Soon you’ll reach a T and a map. A bench offers a place to regain your composure as you take in the view of High Falls. It’s not too late to turn back. You insist? Head back onto the right leg of the T. You’ll soon encounter steps—a terrifying number of them. We counted 167 descending down to a ramp and then more. You can almost feel the Kettle pulling you closer. You hear its thunderous bellow. Pass another unmarked fl ight of metal stairs heading left, down to the river and Upper Falls. Be sure to explore this side path, if you are up for it after viewing the Kettle. If instead you run away screaming, vowing never to return, no one will blame you.

Soon the going gets rougher. A sign points the way to two different overlooks of Devil’s Kettle Falls. From the far left corner of the second overlook, hold tightly to the railing for physical and psychological support. Peer into the whirling cauldron known as the Devil’s Kettle. Though its visual power is impressive, you are only at the precipice of the mystery.

The right half of the waterfall plummets into an oval basin, running a short course through the canyon to Upper Falls. The left half plunges into a hole to… nowhere.

Despite hypotheses that the hole must lead somewhere, its outlet has ever been located. The Devil’s Kettle has swallowed all the dyes, ping pong balls, logs and other objects dropped into it. Nothing has been seen to emerge—not in this dimension.

Scientists have theorized that the water

LOCATED:

Judge C.R. Magney State Park, Hovland

HIKE DIFFICULTY: Strenuous

TRAIL QUALITY: Good to Fair

DISTANCE

ROUND TRIP: 2 miles

TRAILHEAD: All appears normal along the 14-mile stretch of Highway 61, northeast of Grand Marais to Hovland. Enjoy the solidity of the steering wheel beneath your fingers as you turn left into Judge C.R. Magney State Park near milepost 124. Breathe deeply as you drive past the ranger station and into the parking lot. Soon you’ll be leaving reality as you know it behind.

might squeeze into an underground fault or channel, yet the existence of a network of the size and length needed to accommodate half the flow of the river has been declared essentially impossible, given the geological makeup of the area. And so, the mystery remains.

My cell phone rang while I was driving near Two Harbors. It was my neighbor, Chuck.

“Mike, there’s a huge black bear sleeping on your deck,” he said. “Do you want me to call 911?”

BY MICHAEL FURTMAN

“Oh for heaven’s sake, no,” I replied. “That’s just Bert. He probably ate all my sunflower seeds and needs a place to sleep it off. I’ll be home soon.”

And indeed, it was Bert, one of the largest male black bears I’ve ever seen. I know naming wildlife smacks of anthropomorphism, but when an animal takes to dining and sleeping at your house, you really can’t help but come up with a name for it.

Bert has been hanging around my place for nearly a decade. He has a couple of scars, probably picked up in fi ghts with other bears, that allow me to recognize him. He begins to show up in July, and makes the rounds of local apple trees, bird feeders, and the occasional garbage can until it is time for him to den for the winter.

The fi rst time I saw him he was on my deck (which is up a fl ight of stairs), and I watched in awe as he bent a solid half-inch steel pole with a single paw and no effort to get at the bird feeder that hung from its top. At the time, he was already a mature, large male. When I sent the photos of him to a DNR biologist, he estimated that he weighed between 600 and 700 pounds.

That’s a big bear, even if he were a grizzly. And yet, despite his size, he’s never posed a threat to anyone, and has even allowed me to follow him (at a respectful distance) throug h the area woods and neig h-

borhood. Often, only dogs know he’s around. As soon as he sees people, he simply hunkers in a thick area until they move on.

That is the nature of black bears. They avoid confl ict at all costs.

Large adult males have a well-defi ned territory that they know intimately, and are masters at extracting its resources – they know where the best food sources are located, and when they’ll be available. This translates then into bears that go into winter in very good shape with large stores of fat. I fi nd it interesting that “my territory” is in Bert’s territory, and that he’s been exploiting it for nearly a decade. Because I live in Duluth, that also means that hundreds of other homes and thousands of people are within his domain, and yet Bert has managed to keep a low enough profi le that he’s never risen to the level of becoming a “nuisance bear” that must be dealt with by authorities.

autumn, there is no bottom to their barrel. They will eat as long as they are awake, and that is most of the time. For they know, at least biologically, that there will be plenty of time to sleep very, very soon.

Bears in such prime shape appear obese. Their bodies are caked in fat, and they ripple when they walk. Despite such weight gain, black bears remain swift and energetic, thanks to their powerful builds and body chemistry.

It’s a sad fact that the DNR does not relocate problem urban bears, but instead captures and euthanizes them. From past experience, they’ve found that no matter how far they transport these bears before release, the bears always returned to where they were captured.

Bert’s arrival late in the summer is triggered by his need to put on weight for the upcoming winter. This behavior isn’t gluttony, but an irresistible urge. At other times of the year, black bears will quit eating when satiated, but in the late summer and

This excessive eating behavior is known as “hyperphagia” and is triggered by chemical changes to the bear’s blood. During this phase, the weight gain of black bears is phenomenal. For instance, a bear’s caloric intake may increase from about 8,000 per day (your intake is about 2,000 per day) to over 20,000. To do so, it eats nearly three times as much food during its waking hours than in the previous months. A large male bear like Bert might put on 200 pounds in just two months!

Once the bear has stored enough fat to carry it through hibernation, hyperphagia ends, and the bear looks for a denning site. It is at this point Bert disappears for another nine months or so. Although not all my neighbors are as excited about his annual visits (my new neighbor from New York City thinks I’m nuts), I like that this huge, old bear shares my neighborhood. He’s at least 12 years old now, and perhaps much older. Recently, DNR bear researchers recaptured a radio-collared sow black bea r they’ve been studying that is now an incredible 37 years old.

With luck, Bert may be still roaming this neighborhood when Justin’s five-year-old son enters college. The keys to Bert's survival will depend upon two things: that he continues to maintain his non-threatening profi le, and that people remain tolerant, and don’t insist that this magnificent old bear be destroyed simply because their garbage can was tipped or their bird feeder munched on.

I’m confident Bert will do his part.

When I was 18, I spent two and a half months in New Zealand. I hiked through misty, primevallooking forests with giant ferns straight out of the Jurassic Period. Skidded down sand dunes on a skimboard. Saw kauri trees with trunks so big it would take a dozen men to circle them w ith outstretched arms. Huffed and puffed over the Tongariro Crossing between Mounts Tongariro and Ngauruhoe. (Ngauruhoe doubled for Mount Doom in the Lord of the Rings fi lms.)

By Deane Morrison UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA STARWATCH

October - November

are essential for stability, which you need when doing a shot with slow shutter speed.

BY

In those two and a half months, guess how many rolls of fi lm I used? Four.

“I want to experience the experience, not photograph it,” I would explain, with the kind of earnest insufferability only an 18-year-old can muster. “My memory is my fi lm.”

Part of the reason I wasn’t snapping photos left and right was that I was working with disposable fi lm cam-

eras, which offer exactly two options for customizing your shots: pointing and clicking.

Years later, I acquired a fancypants digital camera with optical zoom and more processing power than the entire Apollo 11 mission. But I had little idea of how to use it. So two autumns ago I ventured to Michigan with Wisconsin photographer Anna Martineau-Merritt, who shot this issue’s cover. The goal was to shoot fall colors and learn a little bit about how to use a camera.

First lesson: The sunny days that make hiking a joy are less than ideal for photo shoots. Overcast conditions are ideal for water shots. Lucky for us, the sky was gray and there was little wind.

We fueled up on gas-station coffee and set out early. Our fi rst destination was the Presque Isle River. The leaves were a riot of red, yellow and orange. We hauled tripods and cameras down to the rain-slicked riverbank. Tripods

That was the second lesson and most exciting thing I learned that day. The silky waterfall shots I have always envied and marveled at are achieved with a slow shutter speed. Such shots don’t work on sunny days because the sun glare off the water turns the image into a mass of white.

Down by the river, I fiddled with my shutter speed until—lo and behold—my camera captured a silkywater shot.

From there we went to Lake of the Clouds, which was barely visible through the rain that had sprung up. Oh well. Then we sped to Copper Falls State Park to catch the fading light. Photographers call the hour before sunset “the golden hour” for the muted glow it gives the landscape.

I was hooked. Bright colors and interesting compositions started jumping out at me all the time. I began carrying my camera in my shoulder bag. Instead of hiking fast, I meandered, camera in hand.

These days—as any of my exasperated travel companions will tell you—I might snap more shots in a day than I used to take in months. This summer I went to Manitoba (see page 20) and in five days took nearly 600 pictures. Now I just need to plan a return trip to New Zealand.

The mid-autumn sky presents several spectacles this year, and they waste no time in getting started. About two hours before dawn on Oct. 1, grab your binoculars and look to the east. You’ll see the bright star Regulus, in Leo, and above and slightly to its right the reddish beacon of Mars. On that morning, the Red Planet appears in the midst of the lovely Beehive star cluster of Cancer—a stunning sight.

Check back on the morning of Nov. 11 to see Mars in a close pairing with Regulus.

Saturn appears in the morning sky near the beginning of November and climbs higher in the east as the month goes by. Our long wait for the planet to open its glorious rings fi nally comes to an end, and on Nov. 22 Saturn gives us another treat. About 90 minutes before sunrise that day, Saturn, the star Spica in Virgo, and a crescent moon will form a graceful curve low in the southeast.

Jupiter makes a terrific apparition this fall, thanks to the giant planet coming almost as close to Earth as it ever does. The best time to see it is around Oct. 28, when Earth glides between the sun and the planet, and Jupiter will be up all night. The planet shines a brilliant yellow and follows the Great Square of Pegasus across the sky.

If you’ve missed Venus, hold tight. The planet is now climbing up through the setting sun’s afterglow and will be an “evening star” this winter.

October’s full Hunter’s Moon will be a beauty, rising the evening of Oct. 11, only three hours before true fullness. November’s full moon rises two and a half hours past fullness on Nov. 10; this moon was known to Algonquin Indians as the Beaver Moon.

1413 E. Hwy 61, Grand Marais, MN

Phone - 218-387-1771 Fax - 218-387-1934

Email - sls@boreal.org

Open Mon-Fri 7 am-5 pm, Sat 8 am-4 pm

Specialty Coffee - Whole Leaf Tea - Gourmet Soups - Bakery Goods - Homemade Sandwiches

We go to incredible lengths to select the nest individual beans for your locally owned Dunn Bros Coffee Stores. Each single-origin bean reects the unique nuances of the farm where it was grown. We take great joy in offering different varieties of coffee roasted daily in our store. We think you’ll take great joy in drinking them.

Dunn Bros Coffee 2401 London Road Duluth, MN 55812 (218) 724-8838

2 Blocks West of Blackwoods Restaurant, across from the Edgewater Hotel and Waterpark

By Shawn Perich

If you would like to take up bowhunting, now is the time to begin preparing for next year. That’s the advice from Scott Puch at Superior Lumber in Grand Marais. Puch, an avid archer and purveyor of archery equipment, says it takes time to become proficient at shooting a bow.

“You can’t buy a bow, crawl into a tree and shoot a deer,” he says. “In respect for the animal, you want to know you have the ability as an archer to make a clean kill.”

As outdoor sports go, you can get started in bowhunting at relatively little expense. You can buy a decent, bow for less than $200 and get a halfdozen carbon arrows for around $50. You can upgrade your bow and add accessories as you learn more about archery. For a total investment of less than $500, spread over a couple

of years, you can purchase everything you need to be a bowhunter.

It’s important not to start with too much bow—one with a draw weight that is difficult for you to pull back. Puch suggests starting out with a lesser draw weight and then getting a stronger bow later once you’ve learned how to shoot.

just enjoy target shooting. More than a few are kids and women.

“You want to be able to control your shot,” he says. “If you start out right, you’ll develop good habits.”

Where can you practice? Many archers have a target set up in their backyard. You can also join an archery club or an informal group of shooters. Puch says he gets together about once a week during the winter with other archers to shoot at the local high school. Some are hunters, others

Puch says an aspect of bowhuntin g he fi nds attractive is the length of the deer hunting season, which begins in September and ends after Christmas. By contrast, the deer gun season is only two weeks long.

He also likes the challenge of attempting to get close enough whitetail to kill it with an arrow. Doing so is never easy. Puch, like many bowhunters, fi nds that challenge has become the focus of his hunting.

“I never pick up a gun anymore,” he says, “because bowhunting is such a great sport.”

By Shelby Gonzalez

Ready or not, winter is on its way. W hatever your choice of outdoor recreation—whether you dream of candlelit cross-country trails, powder days on the slopes, glassy waves or wolfhaunted backcountry campsites—you can prep for the coming season by giving your equipment the once-over.

Start with your everyday outdoor apparel items: boots, jackets and parkas. Clean everything and re-apply waterproofi ng as necessary. Check for fit and wear. Does your venerable down jacket leak so many feathers you look like a cat that just ate a canary? Might be time for a replacement. Do your boots fit, with enough room for wool socks and air circulation? This is a particular consideration for fast-growing kids—last year’s duds may not do the trick this year. Also consider function. Did your feet stay warm last winter?

Maintenance for winter gear is simi-

lar across different pursuits. Here is the rundown from Beth Ambrosen, guide and “administrative goddess” at Stone Harbor Wilderness Supply in Grand Marais.

“Prepping for winter actually begins in the spring when you store your skis. You want to strip off the old wax all the way down to the bare surface and reapply a glide wax for protection over the summer. Store them properly, retaining the camber of the skis.

“In the winter season when you pull them out, you shouldn’t have to reapply the glide wax. You should just be able to buff them up using a waxing towel and apply a ski wax.

“With downhill or backcountry skis, if they have a metal edge, you might

want that sharpened. If you have any nicks or dents, you’ll want to attend to those. If you have leather boots ,you’ll want to apply a good leather preservative to keep them soft and supple. With snowboards, you’re going to be waxing and caring for them much in the same manner as skis.”

Favorite winter activity:

“Ooh, that’s hard! I’d have to say cross-country skiing. We have a lot of trails right behind our house.”

In August, I spent five days exploring the attractions of a neighboring— and quite neighborly— region. I discovered there is more to Manitoba than meets the eye.

Take the wildlife. While most of the province is prairie, Riding Mountain National Park is a patch of boreal forest reminiscent of the Northern Wilds, with elk, moose, black bears and wolves, plus a herd of bison. To the far north is Churchill, home of beluga whales and polar bears.

History abounds. West of Winnipeg, you will occasionally spot churches crowned with onion domes that look like something straight out of Istanbul. These are Ukranian Catholic churches. Some sport ornately hand-painted interiors.

I got a taste of Ukraine by baking bread in a traditional clay oven at Trembowla Cross of Freedom Historical Site and Museum near Dauphin.

Another culinary treat was an al fresco lunch at Aditis Touch Greenhouse in Onanole, featuring walleye, heirloom vegetables, and a dessert of homemade icecream.

Somewhere between Poor Michael’s Bookshop in Onanole and the famous “Stone Angel” statue in Neepawa (the lily capital of Canada), I realized I will have to come back. Hasta la vista, Manitoba. —Shelby Gonzalez

Hunting for waterfowl in Northwestern Ontario is a great pastime that gets little acknowledgement. Being so close to Manitoba and its incredible duck- and goosehunting opportunities makes the Northwest seem like an ugly stepdaughter. Yet the hunting for ducks and geese here can be spectacular.

BY GORD ELLIS

Some of my favourite outdoor experiences ever have taken place in duck blinds along Northwestern Ontario lakes and rivers. I remember one trip to the Longlac area where a few friends and I paddled down a meandering river and set up in an oxbow. The array of ducks species we saw was amazing. We threw out decoys and soon had mallards, black ducks and gadwall dropping into them. There were also green-wing teal buzzing by like tiny jet planes. The hunting was fast and varied. In a couple of hours, we’d managed a brace of birds and seen the spectrum of northern ducks.

Another time, near Ignace, a friend and I grunted a canoe into a backcoun-

try lake that was bowlshaped and loaded with wild rice. We set up on a rocky point, and tossed some mallard decoys out, as well as a couple of goldeneye and geese dekes on the edges.

As we sat and watched, huge flocks of ringnecked ducks flew circles around the lake. They looked like nothing so much as a bunch of giant bees, the flock shape shifting as they flew. We enjoyed some exciting pass shooting on these ducks, and also took a few bonus mallards. It was an incredible experience, made all the more special by the sheer remoteness of it. There were no other hunters around, and probably wouldn’t be anytime soon.

Lake Superior also offers unique waterfowl hunts. Early in the season, the river mouths and wetlands hold any number of duck species. The local birds are the focus of the early hunt, but these are soon replaced by flocks of northern mallards in October. Just before the snow fl ies, big groups of scaup arrive and raft up on Lake Superior.

These are not easy birds to hunt, but it can be done if you have the gea r and intestinal fortitude to deal with Gitchee-Gumee in November. This is not a hunt for the faint of heart.

As much as the wilderness water hunts are fun, the agricultural fields on the outskirts of Thunder Bay, Fort Frances and Dryden are much easier for most urban hunters to access. Here are found some enormous flocks of geese and a few mallards. The geese are attracted to the wide variety of grains left behind from the harvest. Although the hunting can start in early September, the really big numbers of geese that show up in October and early November.

Most field hunters use what’s called a coffi n blind. This contraption allows you to lie in the field fully covered by camoufl age. Generally a large set of goose decoys is set up in such a way that the birds will fl y into them and make fi nal approach very close to the hunters. The migrating geese are then called into the decoys by one of the hunters. When the birds are within range, you pop out of the coffin blind much like a jack-in-the-box. It’s an exciting way to hunt these large birds.

Recommended by Buck's Radio Shack, Grand Marais

Make your next outdoor adventure in the northern wilds a little safer with the SPOT Personal Tracker, a satellite GPS messenger device that is smaller, cheaper and easier to use than a satellite phone.

Buck’s Hardware Hank (A RadioShack Dealer) 18 1st Ave., Grand Marais (218) 387-9645

Recommended by Piragis Northwoods, Ely

This 'Canoe Tree Pendant' was made exclusively for us, and our paddling clients. Made by Minnesota artist Josef Reiter. This sterling silver pendant features a pair of canoers, beneath a cutout pine tree. Hung from an 18" sterling silver chain. 1 1/8"x 3/4". www.boundarywaterscatalog.com/browse.cfm/4,6242.html

Piragis Northwoods 105 N. Central Ave., Ely www.piragis.com • 1-800-223-6565

Recommended by Chaltrek, Thunder Bay

Whether in the car, at home, in the office, or on a camping trip, your companion will have a cozy place to snooze with our Mt. Bachelor Pad. In addition to keeping dogs comfortable, this easy-to-carry bed will cover furniture, car upholstery, or anyplace needing protection from dirt and dog hair.

Chaltrek 404 Balmoral Street, Thunder Bay www.chaltrek.com

Garlic—the queen of fl avorings and the bane of cold germs—is one of the fi nest things you can grow in your garden. Its beautiful green spikes give promise of greattasting dishes and sauces all summer long as it works its magic below the soil.

When the lowest three leaves of each garlic plant turn brown and crispy at the end of July or early August, it’s time to lift the bulbs from the soil and see what this year’s growing season has provided.

My garlic was incredible this year, as were the harvests from many gardens on the North Shore. Big, succulent cloves cleaved from the bulbs are full of piquant fl avor. My salad dressings and pestos have never tasted so good.

BY JOAN FARNAM

Here in the Northern Wilds, it’s best to grow hardnecked garlic. The soft-neck varieties, which you can easily craft into those spectacular garlic braids you see in Italian restaurants, do not weather our extreme temps very well. But the hard-neck varieties thrive, and there are quite a few to choose from.

Some, like Russian Red and Siberian, are streaked w ith purple on their outer coverings and store well. Another variety, Music, for example, is a porcelain garlic with white skins and large cloves. I grew a little of each this year, but must admit I can’t tell the difference in fl avor. Garlic growers claim that Music has a milder fl vor than the robust reds, but my Music is loud and noisy, and I like that.

CRUSH one large clove of garlic in a garlic press into a wooden mixing bowl.

ADD saltandfreshlygratedblackpepperand work them together against the sides of the bowl with a fork until well mixed.

MEASURE out a good quality olive oil and red wine vinegar in a 3-to-1 proportion, i.e. 3 tablespoons olive oil and 1 tablespoon vinegar, and add to the mixing bowl.

ADD 1-2teaspoonsdrymustard,ifdesired.

SWIRL together with the garlic mixture until emulsified.Extradressingcanbekeptinacovered glassjarintherefrigeratorforaweekormore.

According to the University of Minnesota Extension service, purple varieties like the Siberian store the best, but I’ve never had problems with Music. Garlic needs to be stored in a cool, dry, dark place, and is usually bundled and hung in the room for good air circulation.

I got my starting bulbs from Ann Rosenquist, a local gardener who has been selecting for the growing conditions in Grand Marais for years. That’s actually the best way to get your seed stock—fi nd out who has great luck and beautiful bulbs in your area and buy from them. Check the Minnesota Extension web site at www.extension.umn.

edu for names of commercial growers as well as lots more info about garlic. Minnesotagrown.com is also a great site to fi nd sources for garlic and other produce.

Garlic needs good, well-drained soil with lots of organic matter, a pH between 6.2 and 6.8, and plenty of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium. Prepare the beds well with compost and wellrotted manure and plant each clove about 6 inches apart, blunt end down, about two to three weeks after the fi rst killing frost. You don’t want to plant too early. The growing tips shouldn’t breach the top of the ground before winter, but you do want the garlic to establish a good root system before the ground freezes. It’s always good to mulch with straw after the ground is hard. That keeps the temps even and prevents heaving in the spring. When the weather begins warming, you can pull the straw away from the rows and leave it as ground cover for the growing season.

Garlic has medicinal properties that will help keep you healthy. If you have vampires in your neighborhood, hanging a head of garlic around your neck should ward them off. And remember, everything except breakfast cereal will probably taste better with a little garlic.

By Hank Shaw • RODALE, $25.99

Hank Shaw has a wild appetite. His award-winning blog, Hunter Angler Gardener Cook, taps into the burgeoning locavore movement, teaching people how to gather and prepare wild foods. Unlike many outdoor cooks, Shaw’s experience is nationwide, which means he covers everything from saltwater mussels to High Plains pheasants, as well as a long list of unusual creatures you won’t find in a typical fish and game cook book. There is also a section on edible wild plants. The recipes in the book are a welcome cut above average, reflecting Shaw’s culinary abilities. This book is a great addition to the library of the newly minted locavore or the grizzled outdoorsman.

—Shawn Perich

By Scott F. Wolter • ILLUSTRATED BY RICK KOLLATH

The Lake Superior agate is a gem even a child can recognize and find, which is one reason agate picking is so popular. Another reasons is because many folks are fascinated with these beautiful rocks. This is an excellent book for anyone who shares that fascination. This slim volume is a compendium of agate information, including how to identify various agates, where to look for them, a list of local lapidary shops and a gallery of famous agates. Most North Shore rock pickers will consider this book indispensable.

—Shawn Perich

Marcy Bolinger says Around a Woodsy Corner may be her fi rst and only book. She enjoyed writing it, but she didn’t realize how much work it would eventually entail.

“It took three years to write and publish,” she says.

Inspired by time spent in the woods with her grandchildren, Bolinger, who has a cabin on Tom Lake north of Hovland, wrote a book about going for an ATV ride and encountering northwoods wildlife along the way. It is colorfully illustrated by Rhonda Weitzel, her sister-in-law.

“My grandchildren have a love for the area,” Bolinger says. “Where else can you go out and see a moose?” Around a Woodsy Corner is available at North Shore gift shops.

—Shawn Perich

Mountain Hardwear Kanza 55

When I received the Mountain Hardware Kanza, I was surprised by its light weight. The size medium weighs in at just over three pounds and offers 55 liters (3,350 cu. in.) capacity, yet manages to include the adjustability and features of a heavier pack. For example, the vertical position of the waistbelt can be adjusted. The Kanza offers a litany of organizational and comfort features, including generously padded straps, back panel, waistbelt and lumbar pad; a front pocket; elastic side pockets; a zippered lid with bungee webbing on top, two isolation pockets; compression straps; ski pole/ice tool straps and stowable sleeping-pad straps. MSRP $175. More information at www.mountainhardwear.com.

–Shelby Gonzalez

Leki Cressida Aergon

SpeedLock AS

Adjusting the Leki Cressida Aergon SpeedLock AS trekking poles is a snap. You simply flip out the two blazeorange clips, extend the pole to your desired height (the range is 65-125 cm), and flip the clips back in place to lock it. Repeat with the other pole. It took about as much time as tying my shoes. Second, the poles were superlight—17.4 ounces, to be exact—and the grips fit my hands nicely. The Cressidas are part of Leki’s “Wildflower” line designed for women. They were a great help on a recent hike. The carbide tips never slipped after I planted them, even on bare rock. Hiking downhill was made easier by the poles because the soft antishock system absorbed some of the impact of each step. It was love at first hike. MSRP $139.95. More information at www.leki.com. –Shelby Gonzalez

The Triple Aught Design Valkryie Hoodie is akin to a good pair of cargo pants: durable, versatile and packed with pockets. The fleece jacket comes in both men’s and women’s styles. The jacket laughs in the face of foul weather with Polartec WindPro fleece and a DWR (durable water repellant) finish. With sharp styling and six pockets on the body and sleeves to stash your gear, the hoodie has sturdy, functional construction. MSRP $215. More information at www.tripleaughtdesign. com. –Kate

Watson

The Sport-Brella Chair is smart new version of an old standard—the fold-out sport chair. Although it is about the same size and weight as a standard chair, it has an attached swivel umbrella to shield you from the sun. The umbrella opens out to 46 inches wide and has a UPF 50+ lining for maximum sun protection. If it is windy or cloudy, you don’t have to raise the umbrella. The Spor t-Brella Chair has a built-in cup holder, bottle opener and item pouch. Folds down instantly and fits into a compact carry bag. MSRP $39.99. More information at sport-brella.com Shawn Perich

editor@northernwilds.com

$5 per line. 3 line minimum. 50 characters per line including spaces and punctuation. All classifieds must be submitted in writing via mail, fax or email. (If emailing, please call to pay by credit card) Cost of ad is per insertion. Additional Options: Bold & CAPS: per word: .50¢/ Entire Ad: $9.00. Centered: $5.00. Fax or mail advertisment to: Northern Wilds Media, Inc, PO Box 26, Grand Marais, MN 55604 Phone/Fax: 218-387-9475 Email: class@northernwilds. com. For display classified ads (with photos/logos/boxes), please contact Calie Vannet at 218-387-9475 or email calie@ northernwilds.com. Issue Deadlines: The 12th of these months: Jan, March, May, July, Sept

Almost 36 years after the Edmund Fitzgerald sank to the bottom of Lake Superior, taking its 29 crew members w ith her, mystery still surrounds just what happened on Sunday, Nov. 9, 1975 to sink the 729-foot freighter.

The U.S. Coast Guard investigation laid the blame on the crew not properly securing the hatches, but their fi ndings were met with scepticism. After the inquiry, the question remained: What sank the Edmund Fitzgerald?

of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Two internationally known Canadian divers think they may have the answer. So compelling was their case on the TV documentary series “Dive Detectives” that singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot revised some of the lyrics of his ballad, “The Wreck

For 17 years, the Fitzgerald was the “Pride of the American Flag,” setting all kinds of tonnage and shipping records. On Nov. 9, 1975, when she sailed out onto Lake Superior from Superior, Wis. with veteran mariner Capt. Ernest McSorley in command, she had already logged a total of 748 voyages and sailed over one million miles. It was her 17th winter of battling the November storms on the Great Lakes. But the storm she would experience in the coming hours would be so intense, so ferocious, that even Capt. McSorley commented it was “one of the worst seas” he had ever seen.

By 7 p.m. the next day (Nov. 10), the battered ship had a bad

list, had lost both radars and was taking heavy seas. She was about 14 miles from the safe harbour of Whitefish Bay, just a little over 90 minutes of sailing time.

At 7:10 p.m., when asked how they were making out, Capt. McSorley told the Arthur M. Anderson—which was sailing about 10 miles behind her—replied, “We are holding our own.” It was the last time anyone heard from the Fitzgerald. By 7:15 pm, the Edmund Fitzgerald and her crew of 29 had disappeared.

Last year, after leading their own research and investigation into the sinking, including simulating the actual weather and sea condi-

was then they saw a huge wave pouring green water over thei r entire vessel.

Fighting the water, the crew got the ship’s bow back up, but then, Cooper recalled, “Another wave just like the fi rst one or bigger hit us again.” The massive waves slammed the Anderson, and then raced toward the wounded Fitzgerald, travelling a mile a minute. If they continued on course, the super waves would have hit the Fitzgerald 10 minutes later. Cooper’s observations seem to support the rogue wave theor y of the Fletchers.

tions, Canadians Mike Fletcher and his son Warren concluded that a rogue wave delivered the fi nal blow to an already damaged ship. Their fi ndings support what Capt. Jessie “Bernie” Cooper of the Arthur M. Anderson experienced shortly before they lost contact with the Fitzgerald. Cooper and his First Mate had been watching their radar closely when they felt an unexpected bump. The Anderson lurched. It

So do the results of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) when a few years ago they recreated the Fitzgerald storm using 21st-century tools. NOAA concluded the storm’s worst marine conditions occurred briefl y in a small specific area of Lake Superior—and that location was “coincident with the time and location at which the ship Edmund Fitzgerald was lost.”

In other words, Lake Superior’s perfect storm window was short, but was big enough to swallow the Fitzgerald—an ailing ship in the wrong place at the wron g time.

Back in Ely's logging days the lumber companies would hire people to provide “pine beef”—mostly moose or caribou—to feed the lumberjacks. One hunter was a crooked-armed trapper named Mike Kelly.

One fall, he shot a cow moose, only to discover that she’d had two calves. Rather than shoot them, he looped ropes around their necks and marched them into town on the old logging road running east toward the Kawishiwi River. He walked up Sheridan Street to the front of the Crossman Saloon and Buffet and tied his moose to the hitching post.

IRON MIKE HILLMAN

Mike Kelly entered the saloon and asked owner Ed Crossman to pour him three fi ngers of whiskey and a schooner of cold beer. By this time, the saloon was starting to fi ll up with curious people.

Ed Crossman saw that these two moose would be a great gimmick to bring people into his business. Before the night was over, he and Mike Kelly made a deal. Ed Crossman became the owner of two moose.

He concocted a plan to offer moosedrawn cart and sleigh rides. He kept the moose at his farm on Shagawa Lake, working on getting them used to being in harness. The moose didn’t mind being harnessed, and they were as quiet as two old

horses. The problem was that they wouldn’t move.

Nothing Ed Crossman tried could make the animals take a step forward, much less pull a cart. Just as Crossman was about to give up on his investment, his wife Addie asked if she might try. He was dubious, but had no other option. Addie sat down and grabbed the reins.

She made a clicking sound out of the side of her mouth, snapped the reins, and the two moose started off as if they had been working together all their lives.

Others tried, but the only person the moose would heed was Addie Crossman. All winter, Ed Crossman’s plan of attracting business with moose sleigh rides worked well.

When the snow melted and the streets turned to mud, he gave his wife and her now-famous team some time off. In a few weeks the town would fi ll with lumberjacks flush with cash after a winter in the woods and Crossman would arranged for a photographer to offer commemorative pictures—for a fee, of course. There was gold in them thar mooses.

Then, just before they were going to make Ed Crossman rich, one of them vanished. No one knows just what happened to that moose, though there were dark ru-

mors of poaching by a jealous business rival. Without her sister, the animal stopped eating and wasted away. Many in town

felt she died of a broken heart. Once, in a world of one-horse towns, Ely could boast of being a two-moose kind of place.