Call For Articles

North Carolina Pharmacist (NCP) is now accepting articles for publication consideration. As a peer-reviewed publication, NCP aims to inform, educate, and inspire pharmacists— from students and residents to seasoned practitioners— as well as pharmacy technicians in all areas of practice. We welcome a wide variety of submissions, including original research, quality improvement initiatives, medication safety, case reports or case series, reviews, clinical pearls, unique business models, technology innovations, and opinion pieces. Articles authored by students, residents, and new practitioners are encouraged, and mentors and preceptors are asked to guide their mentees and students in submitting appropriate written work for publication. The Author Instructions have been updated to clarify formatting requirements, improve guidance on referencing, and streamline the submission process. Key changes include a submission disclosure statement and notices regarding the appropriate use of AI. Authors are encouraged to review the complete instructions before submitting to ensure compliance with the new policies. Don’t miss this opportunity to share your knowledge and contribute to the advancement of pharmacy in North Carolina. For details on formatting and article types, click Guidelines for Authors, and for questions, please contact Tina Thornhill, PharmD, FASCP, FNCAP, Editor, at tina.h.thornhill@gmail.com.

Official Journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists

PO Box 58

36 Court Square, SW

Graham, NC 27253

Phone: (984) 439-1646 www.ncpharmacists.org

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Tina Thornhill

LAYOUT/DESIGN

Rhonda Horner-Davis

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Anna Armstrong

Jamie Brown

Lisa Dinkins

Jean Douglas

Brock Harris

Amy Holmes

John Kessler

Angela Livingood

Bill Taylor

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Penny Shelton

PRESIDENT

Tom D’Andrea

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Leigh Foushee

PAST PRESIDENT

Bob Granko

TREASURER

Ryan Mills

SECRETARY

Macary Marciniak

Talia Carlson, Chair, SPF

Tyler Pasour, Chair, NPF

Lisa Dinkins, Chair, Community

Trent Beach, Chair, Health-System

Aparna Krishnamurthy, Chair, Chronic Care

Glenn Herrington, Chair, Ambulatory

Angela Livingood, At-Large

Elizabeth Locklear, At-Large

Leslie Barefoot, At-Large

North Carolina Pharmacist (ISSN 0528-1725) is the official journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists. An electronic version is published quarterly. The journal is provided to NCAP members through allocation of annual dues. Opinions expressed in North Carolina Pharmacist are not necessarily official positions or policies of the Association. Publication of an advertisement does not represent an endorsement. Nothing in this publication may be reproduced in any manner, either whole or in part, without specific written permission of the publisher.

North Carolina Pharmacist

CORRECTIONS AND ADVERTISING

While spring is traditionally the season we associate with fresh starts and renewal, this fall, the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists is teeming with transformation, energy, and optimism. As the leaves begin to turn, so too does a new chapter in our Association’s journey—one that honors our past while wholeheartedly embracing the future.

This year marks a significant milestone: 25 years of unification for the pharmacy profession in North Carolina. It’s a moment to reflect on how far we have come—and to recognize the tremendous achievements that are reshaping the landscape of pharmacy practice in our state. From landmark legislative victories that expand the scope and impact of our profession, to the physical relocation of our headquarters from Durham to Graham, NCAP is not just moving forward; we are stepping boldly into the future.

As we settle into our new home, we are also expanding our team with the creation of a Membership Development Coordinator position. This role is a direct investment in our members, designed to strengthen engagement, foster inclusivity, and ensure that every pharmacy professional in North Carolina feels seen, heard, and valued.

The past nine years have been dedicated to building a strong foundation, characterized by sound governance, efficient operations, highly valued re-

Penny S. Shelton, PharmD, FASCP, FNCAP

A Season of New Beginnings: NCAP’s Bold Step Forward

sources, and a clear, consistent voice for the profession. Now, as we look to the next decade, it’s time to pivot. We are shifting from building a well-oiled machine to growing NCAP into an undeniable force for pharmacy and healthcare in North Carolina

The NCAP Board of Directors has been deeply engaged in a series of future-focused discussions, asking bold questions about what lies ahead. These conversations are shaping the framework for our next strategic plan—one that will be visionary, inclusive, and responsive to the evolving needs of our members and the communities we serve.

Simultaneously, the NCAP Endowment Board is undergoing its own strategic evolution. In lockstep with the Association, it is preparing to help pave a bright future—one that ensures sustainability, innovation, and impact for the Association for generations to come.

The futurist Rosabeth Moss Kanter once said, “Innovation is the ability to see change as an opportunity—not a threat.” These words ring especially true as NCAP steps into a new era of possibility. As we embrace this season of change, we are reminded of the words of the author Gail Sheehy: “If we don’t change, we don’t grow. If we don’t grow, we aren’t really living.” Change is not just inevitable; it is essential. It is the catalyst for innovation, the spark for progress, and the heartbeat of a thriving profession.

At NCAP, we are committed to building an Association that is inclusive of all pharmacy professionals—from technicians to students, from community and health-system pharmacists to those who are educators, consultants, or other specialists in the profession. Our mission remains steadfast: to unite, serve, and advance the profession of pharmacy in North Carolina

This is more than a new chapter. It’s a new beginning. And we couldn’t be more excited to write it with you.

Always Pharmacy Proud, Penny

2530 Professional Road Suite 200 North Chesterfield, Virginia 23235

Toll Free: (866) 365-7472

www.medicationsafety.org

I feel a profound sense of hope and excitement because of the new pharmacists who have joined the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists (NCAP). Reflecting on my own journey in this profession, I cannot help but acknowledge that we are at a pivotal moment in pharmacy. Over the past few years, I often wondered if future generations would possess the necessary drive and commitment to uphold the esteemed reputation of pharmacy. However, my concerns have been put to rest.

I am genuinely impressed by the takecharge attitude of our new NCAP pharmacists. They embody the spirit of innovation and dedication that our profession so desperately needs. In many ways, Generation Z has received a bad rap. We hear the stereotypes that portray them as disengaged or disinterested. Yet as I work with this new cohort, I see industrious individuals who are not just eager to step into their roles but are also deeply involved in their communities. They want to make a difference and help others. They are building network and mentorship initiatives with an interest in growing service and increasing legislative activities. This is the essence of pharmacy.

We are more than dispensers of medication; we are healthcare advocates, educators, and trusted sources of support. As I reflect on the future of our profession, I have no doubt that phar-

Tom D’Andrea, RPh

The Future of Pharmacy is in Good Hands

macy will not only survive but thrive. The passion and commitment of our newest NCAP pharmacists assure me that we are in capable hands. Through our Association, we will continue to uphold the values of our profession and strive to be recognized as one of the most respected fields. With our new members on board, we will continue to shape the future of pharmacy and ensure that it remains a cornerstone of healthcare.

Pharmacy proud, Tom

Better Brands and Experiences

Through industry-leading partnerships, we provide you with the most exclusive, in-demand offers in travel, entertainment, retail and beyond.

www.workingadvantage.com

Expert coverage for experts like you.

Taking care of others is what you do. But even the best caregivers need looking after, too. That’s where the insurance experts at Pharmacists Mutual come in.

As a pharmacist, you hold an esteemed position in your community. People rely on you for your expert advice, unique knowledge, and experienced opinions. But by the very nature of your profession, you can become a natural target.

That’s why, with more than 110 years of experience, more pharmacists depend on Pharmacists Mutual for the added insurance protection and coverage they need to carry out their critical work.

Evaluating Anti-Hypertensive Management Amongst African American Patients through Inpatient and Outpatient Pharmacist Collaboration

Abstract

By: Dr. Lindsey Katsaros, Dr. Nathan Batchelder, Dr. Michelle Turner, and Dr. Jimmy Wyland

Background: In 2022, Cone Health identified a health equity gap in their community, revealing lower rates of hypertension control among Black and African American patients compared to other ethnicities and races. Cone Health launched an initiative in 2023 to eliminate this health equity gap in the community it serves. This initiative started with blood pressure screenings and ambulatory care pharmacist visits for hypertension management. The objective of this study was to assess the impact of collaborative hypertension management interventions led by pharmacists in the acute care setting.

Objectives: The primary objective was to compare the number of acute care visits, including hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, within 90 days in patients who were reviewed and offered a pharmacist intervention with those who were not reviewed by a pharmacist.

Methods: This was an IRB-approved and determined exempt evaluation assessing acute care pharmacist transitions of care interventions across four community hospitals and two freestanding emergency departments. This study evaluated outcomes in patients with and without a pharmacist review

and intervention.

Results: A total of 454 patients were evaluated; 30 patients were reviewed by a pharmacist, and 424 patients were not. Patients with a pharmacist review had a higher average number of acute care visits within 90 days compared to patients without a pharmacist review (2.2 vs 0.57, p=0.0036). Patients with an ambulatory care referral (n=15), compared to patients without a referral (n=15), had fewer emergency department visits within 90 days (1.1 vs 2.2) and fewer re-hospitalizations within 90 days (1.3 vs 3.1).

Conclusion: For Black and African American patients with hypertension, this study did not find any reduction in 90-day acute care visits when a pharmacist conducted a review of the patient’s hypertension management. A reduction in acute care visits was observed when patients were referred to an ambulatory care pharmacist.

Background

Nearly half of all Americans in the United States meet diagnostic criteria for uncontrolled hypertension, with Black and African Americans disproportionately having lower control rates compared to other racial and ethnic

groups (1). Most recent guidelines define hypertension as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) greater than or equal to 130 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) greater than or equal to 80 mmHg (2). Between 2017 and 2020, the AHA found that the prevalence of hypertension across the United States was 46.7%, with Black and African American males and females having the highest prevalence rates of 57.5% and 58.4% respectively (2). The AHA also reported that high blood pressure was responsible for $52.2 billion in health care costs between 2018-2019 and nearly 120,000 deaths in 2020 (2). As a result of uncontrolled hypertension, Black and African American patients experience higher rates of heart disease, stroke, and heart failure (1).

Black and African American patients experience higher rates of uncontrolled hypertension due to risk factors related to social drivers of health. Uncontrolled hypertension can be a manifestation of stress, which is worsened by the numerous social stressors that disproportionately impact Black and African Americans within the United States. Major social predictors of poor blood pressure control include race, income, education, and insurance status (3). A major cause of sub-optimal blood pressure management is due to medication non-adherence. Since hypertension is often asymptomatic,

proper education on the importance of medication therapies is vital for motivating patients to take their antihypertensive medications. A collaborative care model that includes a pharmacist in the patient care team in the outpatient setting has been proven to reduce racial and socioeconomic healthcare disparities in the outpatient setting (3).

More focus is needed on supporting patients beyond the outpatient setting. Compared to White patients, Black and African Americans are more likely to utilize the emergency department for management of chronic health conditions and are less likely to have a primary care doctor (4). As such, it is important to provide patients with resources to connect them to care beyond the emergency department for better management of their chronic disease states when possible.

Numerous studies have shown the benefit of pharmacists’ involvement in hypertension management within the ambulatory care setting. The Collaboration Among Pharmacist and Physicians to Improve Outcomes Now trial found that pharmacist involvement in outpatient clinic visits improved blood pressure management and reduced racial and socioeconomic disparities in blood pressure control (5). Within the acute care setting, studies have also shown the benefit of pharmacists providing medication education prior to hospital discharge. A 2006 study published by Schnipper and colleagues found that when pharmacists clarified medication regimens, reviewed side effects, and provided education to patients prior to hospital discharge, this resulted in a significant reduction in adverse drug events within 30 days after hospital discharge (6).

Purpose

There is still an unmet need to improve transitions of care to connect patients

with outpatient resources for better management of chronic disease states, including hypertension. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of collaborative hypertension management interventions led by pharmacists in the acute care setting. The primary objective was to determine if acute-care pharmacist interventions prior to patients’ discharge from the hospital would decrease three-month emergency department visits and hospital re-admission rates across a single health-care system.

Methods

Setting and Design

This was a multi-center retrospective, IRB-exempt, single-cohort/paired study that took place at four community hospitals and two freestanding emergency departments within a single health care system in central North Carolina. The analysis was conducted in compliance with the local Institutional Review Board and Human Subjects Research Committee. The primary objective was to compare the total number of acute care visits for any cause three months after discharge for patients who had a documented pharmacist review and were offered interventions, compared to patients without a documented pharmacist review. The pharmacist interventions that were assessed included providing bedside education on adherence, enrolling patients in Meds-to-Beds delivery of their discharge medications, and referring patients to an ambulatory care pharmacist for further blood pressure management. Pertinent secondary objectives included medication barriers identified by acute care pharmacists and the total number of patients who accepted pharmacy services.

Data Collection

Patients were enrolled in the study between April and October 2024. Patients were eligible to be included if

they were 18 years or older, Black or African American, had a new or prior diagnosis of hypertension, had Managed Medicaid insurance, and presented to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital during the enrollment period. Key exclusion criteria included end-stage renal disease, pregnancy, and patients receiving hospice or palliative care.

Eligible patients were identified via a decision support alert within the electronic medical record if they met the inclusion criteria. Once a patient was identified, the acute care pharmacist was responsible for assessing medication adherence and refill needs, educating patients utilizing a standard education sheet, and offering pharmacy services to help improve transitions of care. Pharmacists were provided with an education sheet that included six questions to ask while providing face-to-face education to patients. The pharmacy services offered included Meds-to-Beds, which delivered discharge medications to patients prior to them leaving the hospital, and referring patients to an ambulatory care pharmacist for outpatient follow-up. Pharmacists documented their interventions within the electronic medical record. This documentation was later used for data collection.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze the primary and secondary endpoints assessed in this study. The Mann-Whitney test was utilized to detect differences in the primary objective and select secondary objectives. A power calculation was not done as all patients who met the inclusion criteria during the study period were included in this analysis.

Results

The analysis of Black and African American patients with hypertension

consisted of 454 patients who had an acute care visit between April and October 2024. The pharmacist documented that they completed a thorough review of hypertension medication management for 30 (6.6%) of these patients. Pharmacists did not document a targeted review of hypertension management for 424 (93.4%) patients. Between the two groups, patients were well-matched in terms of age, gender, comorbidities, and class of blood medications utilized prior to hospitalization. The majority of patients were female (n=272, 60%) with an average age of 48 years old. All demographics are included in Table 1.

Primary Outcome

The number of acute care visits within 90 days [mean (SD)] significantly increased for patients who had a documented pharmacist review compared to patients who did not have a documented review [2.2 (3.78) vs 0.57 (1.17), p=0.0036].

Secondary Outcome

There was no significant difference in the number of emergency department visits [mean (SD)] within 90 days for patients with a documented pharmacist review compared to no documented review [1.63 (3.23) vs 0.44 (1.08), p=0.14]. There was a significant increase in the number of hospital re-admissions within 90 days [mean (SD)] in patients with a documented pharmacist review compared to no documented review [0.57 (0.90) vs 0.14 (0.41), p=0.0001].

Cohort with a Documented Pharmacist Review

Secondary outcomes for patients with a documented pharmacist review are included in Table 2. Of the 30 patients with a pharmacist review, a total of 20 patients accepted a pharmacist intervention. The most common interventions were education provided by the pharmacist (n=16, 53%) and referral sent for an ambulatory care pharmacist appointment (n=15, 50%).

Table 1.

no. (%)

Comorbidities, no. (%)

Blood pressure medications prior to hospitalization, no. (%)

ASCVD = Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ACEi = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor ; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; BP = blood pressure

Blood pressure prior to the acute visit, in the emergency department, and after the acute care visit was collected for patients with a documented pharmacist review. A graphical representation of this data is included in Figure 1. Blood pressure measurements were available prior to the acute care visit for 22 patients and after the acute care visit for 19 patients. Blood pressure was lowest prior to the acute care visits and was highest within the emergency department.

Table 2.

Interventions, no. (%)

provided by a pharmacist

discharge medications provided

(n=15). All follow-up ambulatory care visits were conducted via telephone visits. An ambulatory pharmacist attempted to contact 11 of the patients, and a total of 8 telephone appointments were completed. The pharmacist made adjustments to the patient’s blood pressure medication regimen during 3 of these appointments. The pharmacist documented interventions to improve adherence during 5 of these telephone appointments. Patients who were provided an ambulatory care referral (n=15) compared to patients who were not (n=15) had

sent for an ambulatory care pharmacist appointment

Medication barrier identified by pharmacist, no. (%)

Subgroup Analysis

Further analysis was done comparing patients who were provided an ambulatory care referral for further blood pressure management by a pharmacist (n=15) compared to patients who did not accept an ambulatory care referral

fewer emergency department visits within 90 days [mean (SD), 1.1 (2.0) vs 2.2 (4.1), p=0.223]. A similar trend was observed in the number of acute care visits within 90 days in patients with an ambulatory care referral compared to patients without an ambulatory care

referral [mean (SD), 1.3 (2.0) vs 3.1 (4.9), p=0.925].

Discussion

Acute care pharmacists reviewed and offered transitions of care interventions for Black and African American patients with hypertension at four community hospitals and two freestanding emergency departments within a single health system. The pharmacist documented a review of the patient’s blood pressure management for 30 (6.6%) of patients with an acute care visit during a 7-month review period. Pharmacists intervened on 20 (66.7%) of the patients with a documented review. Patients with a pharmacist review had a higher average number of acute care visits within 90 days compared to patients without a pharmacist review (2.2 vs 0.57 acute care visits in 90 days, p=0.0036). The reasons for hospital readmission or further emergency department visits were not collected.

More success was seen when patients were sent an ambulatory care referral to meet with a pharmacist after hospital discharge. The number of acute care visits within 90 days decreased when patients were referred to a clinical pharmacist practitioner. Pharmacists made meaningful changes to the patient’s blood pressure regimen or assisted with improving adherence, such as by sending in refills for patients, during over half of these appointments. These results further confirm the benefit of pharmacist involvement in patients’ blood pressure management within the ambulatory care setting.

Several limitations were noted within this analysis. Far fewer patients had a documented pharmacist review compared to patients without a documented pharmacist review. This was likely due to the additional workload required by pharmacists, which included time spent speaking with pa-

tients and documenting findings. This workload led to low adoption of this protocol. Additionally, many patients only presented to the emergency department, and there was less time for a pharmacist to review and intervene. For this protocol, pharmacists were also asked to document in a specific location of the electronic medical record, so patients with improper documentation could not be reviewed. A decision support alert was utilized to identify patients who met the inclusion criteria. There are many decision support alerts built within the electronic medical record, and more complex patients have more alerts. Patients with more decision support alerts may have been more likely to be reviewed, leading to selection bias, and could have contributed to the poorer outcomes seen in these patients.

Discharge medications provided via the meds-to-beds program were only available at three of the community hospitals. Discharge medication education was not provided to patients unless they were admitted to the hospital, meaning no education was provided to patients who presented to the free-standing emergency departments.

In conclusion, for Black and African American patients with hypertension,

this study did not find any reduction in acute care visits when an acute care pharmacist conducted a formal review of patients’ hypertension management. There was a reduction in emergency department visits and re-hospitalizations seen when patients were referred to follow-up with an ambulatory care pharmacist. The results from this study further support the efforts of ambulatory care pharmacists to help manage hypertension in the outpatient setting and support the idea of inpatient pharmacists sending ambulatory care referrals. Inpatient pharmacist review and interventions may help support improved transitions of care for the patient. Further efforts should be made to streamline the process of referring patients to a pharmacist for a post-discharge ambulatory care appointment.

Authors: Lindsey Katsaros, PharmD, PGY2 Cardiology Pharmacy Resident, Moses Cone Hospital Department of Pharmacy, lindsey.katsaros@conehealth.com (Corresponding), Nathan Batchelder, PharmD, BCPS, BCIDP, Pharmacy Supervisor, Moses Cone Hospital Department of Pharmacy, Michelle Turner, PharmD, BCPS, BCIDP, Manager and PGY1 Residency Program Director, Moses Cone Hospital Department of Pharmacy, and Jimmy

Figure 1.

Wyland, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist, Moses Cone Hospital Department of Pharmacy

References

1. Maraboto C, Ferdinand KC. Update on hypertension in African-Americans. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(1):33-39. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2019.12.002

2. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023 Feb 21;147(8):e93-e621. doi.org/10.1161/ CIR.0000000000001123

3. Anderegg MD, Gums TH, Uribe L, Coffey CS, James PA, Carter BL. Physician-Pharmacist Collaborative Management: Narrowing the Socioeconomic Blood Pressure Gap. Hypertension. 2016 Nov;68(5):13141320. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08043.

4. Brown LE, Burton R, Hixon B, et al. Factors influencing emergency department preference for access to healthcare. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(5):410-415. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.11.6820

5. Carter BL. Primary Care Physician-Pharmacist Collaborative Care Model: Strategies for Implementation. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(4):363-373. doi:10.1002/ phar.1732

6. Ferdinand KC, Senatore FF, Clayton-Jeter H, et al. Improving Medication Adherence in Cardiometabolic Disease: Practical and Regulatory Implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(4):437-451. doi:10.1016/j. jacc.2016.11.034

Happy American Pharmacists Month!

NCAP is proud to support APhM in collaboration with the American Pharmacists Association. Together, we celebrate the dedication and impact of pharmacy professionals across every community.

Dates to Remember:

Oct 1 – Kickoff: American Pharmacists Month #APhM2025

Oct 3 – National Student Pharmacists Day #studentpharmacistday

Oct 12 – Women Pharmacist Day #womenpharmacistday

Oct 15 – National Pharmacy Technician Day #rxtechday

Utilization and Optimization of Glucagon for Persons at Risk for Hypoglycemia: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

By: Dr. Shawn Riser Taylor, Dr. Michelle Chaplin, Dr. Evan S. Drake, and Dr. Edward T. Chiyaka

Hypoglycemia is a significant concern for individuals with diabetes, particularly those on insulin therapy. While glucagon is recommended for high-risk patients, prescribing and dispensing rates remain low. This mixed-methods study aimed to assess glucagon utilization rates and identify barriers to access.

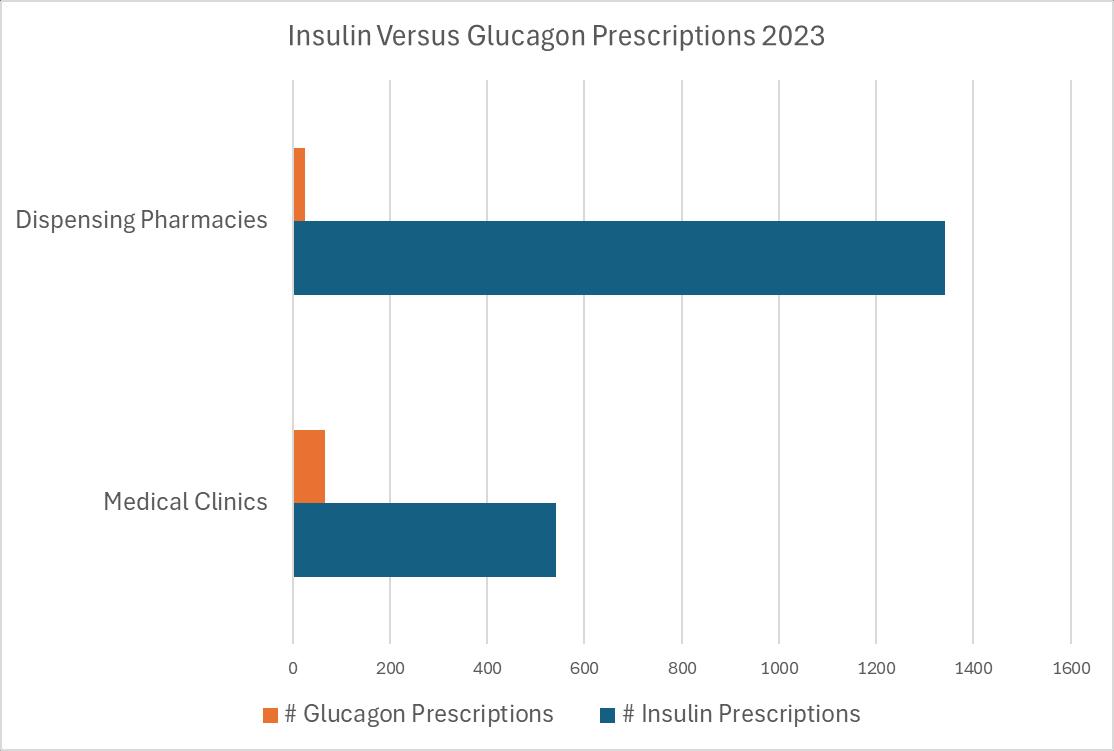

Quantitative data from medical records and pharmacy records showed that in 2023, only 66 glucagon prescriptions were transmitted in four outpatient clinics, with just 26 dispensed from surveyed pharmacies, despite high insulin prescription rates. Qualitative data from healthcare provider interviews highlighted key barriers, including cost, insurance coverage, and lack of pharmacist engagement in prescribing under the standing order. While prescribers frequently educate patients on glucagon use, dispensing pharmacists reported varied educational practices, with many citing a need for more materials and demonstration devices.

Despite the availability of newer, user-friendly glucagon formulations, uptake remains low, partly due to cost concerns and limited reimbursement for prescribing and patient education. The study underscores the need for

standardized workflows in medical and pharmacy settings to assess glucagon necessity, as well as improved insurance coverage and provider education. Addressing these barriers through policy advocacy and better education may increase glucagon accessibility and utilization, ultimately improving outcomes for patients at risk of severe hypoglycemia.

Background

Rates of hypoglycemia amongst people diagnosed with diabetes vary depending on the type of diabetes and severity of the condition, as well as medications prescribed. In the United States (U.S.), approximately 9.2% of emergency department visits attributed to an adverse drug event are insulin-related hypoglycemia and are considered Level 3 hypoglycemic events due to the requirement of assistance to treat. (1) Level 1 or Level 2 hypoglycemic events are those in which an individual can self-treat. Patient-reported data from a global study suggests that over a month, more than half of people diagnosed with diabetes, type 1 or 2, experience at least a single episode of hypoglycemia, with incidence highest amongst those with type 1 diabetes. (2)

Glucose is the recommended treat-

ment for hypoglycemia per the 2025 American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Diabetes Care. (3) For individuals at high risk of hypoglycemia, the ADA recommends that glucagon be prescribed and readily available. Risk factors for hypoglycemia include a previous episode of hypoglycemia, insulin or sulfonylurea therapy, impaired hypoglycemia awareness, end-stage kidney disease, cognitive impairment, older age, polypharmacy, low health literacy, high glycemic variability, substance use disorder, food insecurity, low-income status, and homelessness. Additionally, patients prescribed insulin should be offered education on the prevention and treatment of hypoglycemia from their healthcare provider. (3) Consequences of untreated hypoglycemia can be detrimental, including loss of consciousness, seizure, coma, and even death.

In 2021, the state of North Carolina passed House Bill 96/SL 2021 - 110, a legislative act that authorized immunizing pharmacists to dispense, deliver, or administer glucagon without the need for a prescription from a prescriber. (4) This regulatory change enabled pharmacists to offer critical treatment for severe hypoglycemia, mirroring the authorization provided for medications such as naloxone, nicotine replacement therapy, contracep-

tives, and prenatal vitamins.

Evidence suggests that despite evidence-based recommendations and expanded access through House Bill 96/SL 2021-110, rates of glucagon prescribed and/or dispensed remain low for those individuals at high risk and even those with an emergency department visit for hypoglycemia. (57) To better understand the scope of and barriers to prescribing as well as dispensing glucagon prescriptions for high-risk individuals, this mixed-methods study was developed.

Purpose

The objective of this mixed-methods study is to evaluate utilization rates of glucagon for patients at risk of hypoglycemia and identify barriers to optimal access to glucagon. The study received approval from the institution’s Research Review Board.

Methods

Quantitative data were retrieved from the medical records of the identified sites. Data included the total number of glucagon, sulfonylurea, and insulin prescriptions transmitted and dispensed from participating prescribers and pharmacies, respectively, for the calendar year 2023. Qualitative data were gathered via interviews and a Qualtrics(R) survey of participating prescribers and dispensing pharmacists. (Table 1) Participants were given a $50 Visa gift card for participation. Data included demographic information of the healthcare provider as well as their clinical practice setting and perceptions regarding hypoglycemia, glucagon prescribing, and dispensing.

Table 1: Survey Questionnaire

How long have you been licensed in your current role?

Describe the setting of your practice (ie, rural, urban)?

Describe your payer mix (Medicare, Medicaid, private, Tricare, self-pay, etc)?

What resources do you utilize to stay up to date on diabetes management (ie, guidelines, conferences, organizations)?

What strategies are employed or educational resources available to patients in your practice for hypoglycemia treatment?

How are patients educated on insulin or glucagon administration?

What criteria do you use to determine if a person should receive/be prescribed glucagon?

Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the utilization rates of glucagon among the patients you serve?

Are there any specific patient populations or conditions where you see glucagon being prescribed more in your practice/pharmacy?

Are there specific populations that present challenges when prescribing/dispensing glucagon (ie, elderly, uninsured, etc)?

Can you share any experiences where patients faced difficulties in obtaining or using glucagon, and how were these issues resolved?

What challenges, if any, do you encounter in ensuring that patients receive and understand the instructions for using glucagon?

What educational resources or support would you find beneficial in promoting the optimal use of glucagon among patients?

Specifically for dispensing pharmacists:

How many prescriptions do you fill daily?

How many staff are employed in the pharmacy and what are their roles (ie, pharmacist, pharmacy technician)?

Do you provide vaccinations without a prescriber order?

Do you provide contraception without a prescriber order?

Do you provide prenatal vitamins without a prescriber order?

Do you provide nicotine replacement without a prescriber order?

Do you provide post-exposure prophylaxis without a prescriber order?

Do you provide medication therapy management?

Specifically for prescribers:

How many patients do you see daily?

What support staff do you work with daily (ie, medical assistant, nurse, clinic pharmacist)?

Descriptive statistics were utilized to report demographic characteristics as well as quantitative and qualitative data.

Results

Eight healthcare providers in the state of North Carolina completed the quantitative and qualitative data questions via a Qualtrics® online survey and telephone interview, respectively. One additional dispensing pharmacist completed the online survey portion of the qualitative section but did not complete the telephone interview. One prescriber did not complete the online survey portion of the qualitative section but did complete the interview. Of the healthcare providers, four practice in dispensing pharmacies and four are prescribers in outpatient settings, one in endocrinology, one in family med-

icine, and two in community health centers. Additional demographics of the healthcare providers can be found in Table 2.

As it pertains to prescriptions, in the four outpatient medical clinics, a total of 541 insulin prescriptions and 66 glucagon prescriptions were transmitted to a pharmacy in 2023. (Figure 1) In the same year, amongst the four pharmacies surveyed, a total of 1341 insulin prescriptions were dispensed compared to only 26 glucagon prescriptions. Notably, there were 32 total glucagon orders received at the pharmacies, yielding an approximate 80% fill rate.

All of the interviewed prescribers reported the use of educational hand-

Table 2: Healthcare Provider Demographics

Provider Designation

Type of Practice

Sex

Respondents (n=8)

Prescriber 4 (50%)

Dispensing pharmacist 4 (50%)

Private 2 (25%)

Government 4 (50%)

Specialty 1 (13%)

Other 1 (13%)

Male 3 (37%)

Female 5 (63%)

Specialized training in diabetes Yes 3 (37%) No 5 (63%)

Location of practice

Rural 2 (25%)

Urban 2 (25%)

Suburban 4 (50%)

Payer mix Medicare 41% Medicaid 18%

26% Tricare 5%

Self-pay/uninsured 10%

Resources Used for diabetes management (select all that apply)

Specifically for pharmacists: Respondents (n=5)

Conferences 6 (75%) Guidelines 7 (88%) Organizations 5 (63%)

Mean prescriptions per day 242

Mean number of employees 2.4

Mean number of pharmacy technicians 4.7

Provide vaccinations without prescription No 2 (40%) Yes 3 (60%)

Provide contraception without prescription No 3 (60%) Yes 2 (40%)

Provide prenatal vitamins without prescription No 4 (80%) Yes 1 (20%)

Provide nicotine replacement without prescription No 4 (80%) Yes 1 (20%)

Provide post-exposure prophylaxis without prescription No 4 (80%) Yes 1 (20%)

Provide medication therapy management No 4 (80%) Yes 1 (20%)

Specifically for prescribers: Respondents (n=3)

Mean Number of patients seen daily 10.3

Support staff

outs and/or demonstration devices to provide education on hypoglycemia and glucagon administration, while the dispensing pharmacists’ responses to this question varied. Two provide verbal education, one provides handouts as needed, and one provides no education. The dispensing pharmacists identified the need for more educational materials to promote understanding and use of glucagon, as well

Medical Assistant 3 (100%)

Nurse 2 (67%)

Clinical Pharmacist 1 (33%)

as access to demonstration devices for hands-on teaching. Both prescribers and dispensing pharmacists identified cost and third-party coverage issues as the most significant difficulties they faced. Most dispensing pharmacists were unable to assess trends or barriers in glucagon dispensing due to the low numbers. One interviewee stated, ‘embarrassingly, I don’t even think about it’ regarding the question ‘what

criteria do you use to determine if a person should receive/be prescribed glucagon?’

None of the dispensing pharmacists had prescribed glucagon per the standing order. One pharmacist noted that using the standing order could potentially lead to lost reimbursement since the ready-to-use glucagon agents are expensive and frequently targeted in third-party payor audits. Mostly dispensing pharmacists rely on prescribers of insulin therapies to also prescribe glucagon. One noted cost is a barrier, as well as a preference for oral glucose tablets over injectable glucagon.

Of the prescribers, all had an identified person or team (i.e., clinical pharmacy, nursing) in the office to demonstrate use of glucagon as well as navigate cost and coverage concerns. One prescriber noted that glucagon often expires and may not be reordered in a timely fashion, while another described difficulty in using some products that require reconstitution. Three of the prescribers found that older patients and uninsured individuals present the most challenges when prescribing glucagon.

Discussion

18

Despite overwhelming evidence of the need and benefit of glucagon, results from this mixed-methods study confirm that prescribing and dispensing rates remain low for individuals at risk for hypoglycemia, specifically patients on insulin therapy. A few consistent glucagon barriers were identified. Historically, glucagon was only available as an injection requiring reconstitution and manual manipulation to draw up the dose in a syringe. This was seen as a deterrent for non-medical personnel, as they lacked comfort both in obtaining an accurate dose and delivering it during a stressful medical event. (8) However, in recent years, new ready-

to-use injectable formulations of glucagon have been released, reducing the complexity of administration, including an intranasal formulation. (9-10) Updates to the devices and delivery methods were proposed to address a barrier to accessing glucagon; however, dispensing rates do not seem to have increased as expected.

The passage of NC House Bill 96/SL 2021 - 110 in 2021 was a measure proposed to improve access to glucagon and prevent consequences of untreated hypoglycemia. (4) The data collected in this study, both from the dispensing rates and the qualitative results, reveal that allowance for dispensing pharmacists to prescribe glucagon is vastly underutilized. All healthcare providers involved in the mixed-methods study discussed cost as a limiting factor, highlighting the need to address coverage of all devices on state and national formularies to improve access. As coverage changes evolve, it is also essential that healthcare providers are educated so that outdated access information does not dictate current practice. More formulations may make this more challenging, as plans may cover specific formulations. Based on the evidence of the rate of hypoglycemia and potential consequences of inadequate treatment, advocacy for better coverage is a priority that should be addressed. If assessing the need for glucagon, coverage, and education is not currently part of the medical workflows within an office setting or in a pharmacy for patients with diabetes, this leaves glucagon prescribing up to chance instead of a standardized process. Another potential reason for the lack of uptake may be the lack of reimbursement for the work of prescribing, educating, and demonstrating. Similar to medical offices, if there is no payment model or a prompted process to evaluate the need for and coverage of glucagon, prescribing it may be lost to other activities that do result in revenue generation.

Education is necessary to help patients and caregivers understand how to use devices and the importance of adhering to prescribed medication, as opposed to alternative treatments like glucose tablets. Patients, caregivers, and providers should be educated on the differences between Level 1, 2, and 3 of hypoglycemia to ensure the treatment strategy is appropriate. (3) Respondents involved in this study agreed that access to demonstration devices and education materials significantly aids engagement in utilizing glucagon. These likely need to be more widespread and available in both medical offices and dispensing pharmacies. Though patients with diabetes are often familiar with the variety of devices required for their condition, including injections, glucagon is frequently used when the patient needs a support person to provide treatment. As such, education and device demonstration are necessary for the patient’s family members and/or caregivers. Education on the device should include appropriate instruction for monitoring expiration dates to ensure access to potent glucagon.

Increased access to life-saving medications from dispensing pharmacies has been shown to reduce death. One major study showed that municipalities with larger amounts of naloxone prescribed by pharmacists per a standing order significantly reduced opioid deaths in the given area. (11) To yield similar results with glucagon, further education for pharmacists, reimbursement for the service, and better coverage of agents are necessary. Similarly, having tools such as demonstration devices and educational handouts readily available at pharmacies may improve utilization.

There are several limitations to this study. Overall, with dispensing rates being low and utilization by all healthcare providers being limited, it is difficult to ascertain conclusive outcomes. The data available only utilized dis-

pensing rates and did not include individual patient barriers, including lack of education, lack of desire to fill, or cost of filling.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the need to increase access to glucagon for patients at risk of hypoglycemia. Education of all parties, patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers, as well as advocacy for improved coverage and reimbursement models, is warranted.

Authors: Shawn Riser Taylor, PharmD, CPP, CDCES, Professor and Chair, Department of Outpatient Practice and Social Science, Wingate University School of Pharmacy, s.taylor@wingate. edu (Corresponding author); Michelle Chaplin, PharmD, BCACP, CDCES, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs, Assistant Dean of Pharmacy, Hendersonville Campus, Professor of Pharmacy, Wingate University School of Pharmacy; Evan S. Drake, PharmD, CPP, Assistant Professor of Pharmacy, Zone Coordinator, Hendersonville, Wingate University School of Pharmacy; Edward T. Chiyaka, PhD, MSc, Assistant Professor, Health Care Administration & Research, Department of Social Sciences & Outpatient Practice, Wingate University School of Pharmacy.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals who contributed to the study.

Candice Allen, PharmD, Chantal Matheson, PharmD, Peyton Brown, PharmD, Nur Edwards, PharmD, Ruslan Garcia, MD, Catherine Hefner, FNP-C, Matt Kiger, PharmD, Lisa Meade, PharmD, Travis Smith, PharmD, Tiffany Stephens, PharmD, Tori Taylor, PharmD

References

1. Geller AI, Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, et al. National estimates of insulin-relat-

ed hypoglycemia and errors leading to emergency department visits and hospitalizations. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014 May;174(5):678-86. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.135.

2. Khunti K, Alsifri S, Aronson R, et al. Rates and predictors of hypoglycemia in 27,585 people from 24 countries with insulin-treated type 1 and type 2 diabetes: the global HAT study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016 Sep;18(9):90715. doi: 10.1111/dom.12689. Epub 2016 Jun 20.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Supplement 1):S1–S350. doi: 10.2337/dc25-S01.

4. North Carolina General Assembly. (2021). House Bill 96 / SL 2021-110: Allow Pharmacists to Admin. Injectable Drugs. Retrieved from: https://www. ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2021/H96

5. Mitchell BD, He X, Sturdy IM, Cagle AP, Settles JA. Glucagon prescription patterns in patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes with new-

ly prescribed insulin. Endocr Pract. 2016 Feb;22(2):123-35. doi: 10.4158/ EP15831.

6. Kahn PA, Lui S, McCoy R, Gabbay RA, Lipska K. Glucagon use by U.S. adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2021 May;35(5):107882. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.107882.

7. Fendrick AM, He X, Lui D, Buxbaum JD, Mitchell BD. Glucagon prescriptions for diabetes patients after emergency department visits for hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2018 Oct 2;24(10):861866. doi: 10.4158/EP-2018-0223.

8. Christiansen MP, Cummins M, Prestrelski, et al.Comparison of a readyto-use liquid glucagon injection administered by autoinjector to glucagon emergency kit for the symptomatic relief of severe hypoglycemia: two randomized crossover non-inferiority studies. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2021 Oct;9(1):e002137.

9. Baqsimi. Prescribing Information. Amphastar Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

10. Evoke. Prescribing Information. Xeris

Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

11. Xuan Z, Walley AY, Yan S, Chatterjee A, Green TG, Pollini RA. Pharmacy Naloxone Standing Order and Community Opioid Fatality Rates Over Time. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8):e2427236. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27236

Connecting Top Employers with Premier Professionals.

EMPLOYERS:

Find Your Next Great Hires

• PLACE your job in front of our highly qualified members

• SEARCH our resume database of qualified candidates

• MANAGE jobs and applicant activity right on our site

• LIMIT applicants only to those who are qualified

• FILL your jobs more quickly with great talent

PROFESSIONALS:

• POST a resume or anonymous career profile that leads employers to you

• SEARCH and apply to hundreds of new jobs on the spot by using robust filters

• SET UP efficient job alerts to deliver the latest jobs right to your inbox

• ACCESS career resources, job searching tips and tools NCAP CAREER CENTER

Pharmacist-Led Deprescribing of Inappropriately Prescribed Inhaled Corticosteroids in Veterans with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

By: Dr. Jessica Parks, Dr. Amber Jefferson, Dr. Lauren Howard, and Dr. Cassandra Warsaw

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) management consists of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). ICS use is recommended with a history of COPD hospitalizations, two or more moderate COPD exacerbations within the last two years, an eosinophil (EOS) count of 300 cells/µL or higher, or if the patient is diagnosed with concomitant asthma. ICS should be considered as a last-line option due to increased risk of oral candidiasis, hoarse voice, and pneumonia. Previous studies have demonstrated the benefits of pharmacist-led clinics in managing chronic disease states. The purpose of this quality improvement initiative was to investigate the impact of pharmacist-led deprescribing of inappropriately prescribed inhaled corticosteroids in Veterans with COPD, regardless of initial ICS-containing regimens.

Methods

Retrospective chart reviews were completed for the initiative. A total of 123 Veterans, identified using the COPD Dashboard, were included in the review. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis. Veterans were included if they were assigned to the

designated primary care clinic, had been diagnosed with COPD, and had an active ICS prescription. A total of 54 Veterans met enrollment criteria. Charts were reviewed for an appropriate indication for ICS use. Updated pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBC) were scheduled with consent. If the ICS was deemed inappropriate, the pharmacist contacted the Veteran via telephone to provide education and utilized the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines to determine appropriate therapy. Veterans were contacted via telephone to conduct a COPD management appointment, and based on patient-specific factors, the pharmacist recommended either discontinuing or continuing the ICS-containing inhaler. If an ICS was discontinued, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) or a LAMA/long-acting bronchodilator agonist (LABA) was prescribed as an alternative therapy. Interventions were documented in the electronic health record using a specified note template. Data collection occurred between July and November 2024. The Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee approved the project as a quality improvement initiative, which is exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

Results

Upon examination of the charts, it was noted that the PFT results and CBC lab work were outdated, in accordance with GOLD guidelines for COPD therapeutic management. A total of 21 Veterans obtained updated PFTs, and nine Veterans obtained updated CBC labs. A total of 54 Veterans met the enrollment criteria, and 33 were deemed appropriate for ICS deprescribing. Overall, 76% (N=25) of Veterans agreed to ICS de-escalation.

Conclusions

The data collected further supports the necessity of pharmacist-led clinics to ensure appropriate medications are prescribed and monitoring parameters are upheld. Additionally, pharmacist-led deprescribing of inappropriate ICS inhalers reduces the risk of adverse effects and enables pharmacists to identify patients requiring updated COPD monitoring.

INTRODUCTION

Although COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease, it was identified as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States in 2021, accounting for most of the deaths from chronic lower respiratory diseases, and often directly correlates with the prevalence of tobacco smoking,

which is a key environmental factor for COPD. (1,2) Pharmacists are a key player in the management of chronic disease states, similar to COPD. A recent study by Patil et al. found that pharmacist-led heart failure clinics significantly increased the proportion of patients with optimized heart failure medication regimens, reduced hospitalizations and emergency room visits relating to heart failure, and improved quality of life. (3) In a study by Khdour et al., a pharmacist-led COPD clinic resulted in improved inhaler adherence, reduced hospitalization for COPD exacerbations, and improved quality of life. (4) These studies provide evidence that pharmacists are an integral part of disease state management and identify a need for more pharmacist-led clinics to improve medication adherence, enhance patient safety, reduce health care costs, and improve access to health care.

Previously, ICS inhalers were used for patients with symptomatic COPD, regardless of exacerbation history. Recently, ICS has been recommended as a last-line option in COPD patients, except for indicated patient populations, given the increased risk for oral candidiasis, skin bruising, hoarse voice, and pneumonia. (2) ICS use is indicated in patients with a history of hospitalizations for exacerbations of COPD, two or more moderate exacerbations of COPD within the last two years, blood EOS of 300 cells/µL or higher, and if the patient is diagnosed with concomitant asthma. Overall, it is important to consider ICS as a last-line option and consider de-escalation of ICS once COPD is controlled and remains stable after two years of triple therapy. (2) A recent study conducted at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center and published by Hegland et al., identified 18% of patients with stable COPD on unnecessary triple inhaler therapy. (5)

It is important to note that COPD impacts Veterans at a higher rate than

the general population due to environmental and occupational exposure during service. It is estimated that about 25% of the Veteran population is affected by COPD. Providing evidence-based treatment regimens and deprescribing inappropriate ICS therapy for Veterans diagnosed with COPD can decrease hospital readmission rates, decrease the risk of adverse effects, and improve the Veteran’s overall quality of life. (6) The purpose of this quality improvement initiative was to investigate the impact of pharmacist-led deprescribing of inappropriately prescribed ICSs in Veterans with COPD, regardless of initial ICS-containing regimens.

METHODS

A total of 123 Veterans identified using the Veterans Affairs Academic Detailing COPD Dashboard, potentially qualified for project enrollment. Veterans were included if they were assigned to the designated primary care clinic, had been diagnosed with COPD, and had an active ICS prescription filled within the past 180 days. Charts were reviewed for an appropriate indication for ICS use, such as concomitant asthma diagnosis, COPD/asthma overlap on PFT results, history of hospitalizations for exacerbations of COPD, two or more moderate exacerbations of COPD within the last two years, and blood EOS count of 300 cells/µL or higher. PFTs were deemed outdated if the testing was greater than two years old, and CBC labs were considered outdated if the lab test was obtained more than one year prior to the time of the chart review in accordance with the GOLD guidelines. If indicated, updated PFTs and CBC were scheduled with the Veteran’s consent.

After updated labs were obtained, Veterans were contacted via telephone and provided education. After the patient interview, a treatment plan was developed based on patient-specific factors and the GOLD guidelines. The

pharmacist recommended either discontinuing or continuing the ICS-containing inhaler after assessing the test results and the patient’s medical history. If an ICS was discontinued, a LAMA or LAMA/ LABA inhaler was prescribed as an alternative therapy. Interventions were documented in the electronic health record using a specified note template. Data collection occurred between July 22, 2024, and November 30, 2024. The Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee approved the quality improvement initiative, which is exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

The primary objective of this initiative was to determine the number of pharmacist-led de-escalation recommendations of inappropriately prescribed ICS in Veterans with COPD. Secondary objectives included the number of pharmacist-led non-pharmacological COPD interventions and assessment of initial versus deprescribed COPD inhaler regimens.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize the collected data for both the primary and secondary outcomes. Time “zero” is defined as July 17, 2024, since this was when data was obtained via the COPD Dashboard.

RESULTS

A total of 54 Veterans met the enrollment criteria (Figure 1). Upon examination of the charts, it was noted that 21 Veterans required updated PFTs and nine Veterans required updated CBC lab work in accordance with GOLD guidelines for therapeutic management of COPD. Following telephone contact with the pharmacist, the identified Veterans agreed to update their testing and lab parameters as recommended by the pharmacist. A total of five Veterans were deemed inappropriate for ICS de-escalation due to updated PFT COPD/asthma overlap results,

EOS count of 300 cells/µL or higher, or omission of asthma diagnosis from the electronic health record. These patients were referred to the VA pulmonologist for further evaluation. Thus, a total of 33 Veterans were deemed appropriate for ICS deprescribing.

Of the 33 Veterans contacted for ICS deprescribing, 9% (N = 3) of Veterans were referred to a VA pulmonologist for further COPD workup. There was a total of 15% (N = 5) of Veterans who declined ICS de-escalation despite education on ICS risks provided by a pharmacist. The most common reason for denial was the Veterans’ preference for their current regimen. Overall, 76% (N = 25) of Veterans agreed to ICS de-escalation.

COPD regimens were analyzed to assess initial versus current regimens. It is important to note that formulary ICS de-escalation inhaler options were tiotropium bromide and tiotropium/ olodaterol. The most common LABA/ ICS combination prescribed was fluticasone/salmeterol, which accounted for 80% (N = 20) of Veterans who were agreeable to ICS deprescribing. COPD regimens after deprescribing were as follows: tiotropium/olodaterol, 96% (N = 24), and tiotropium bromide, 4% (N = 1).

DISCUSSION

Pharmacist-led deprescribing of inappropriately prescribed ICSs is advantageous. Most patients who were identified with an inappropriately prescribed ICS inhaler agreed to deprescribing after being contacted by a pharmacist. Pharmacists played an essential role in identifying patients involved in the chart review who required updated COPD monitoring tests. The pharmacists contacted patients via telephone to schedule them for the testing. Thus, pharmacist involvement ensures that appropriate monitoring for COPD remains up-to-date as well. As previously discussed, pharmacist-led clinics can improve medication adherence, en-

hance patient safety, reduce healthcare costs, and improve access to healthcare. This data further suggests that pharmacist-led COPD clinics can ensure appropriate medications are prescribed and COPD monitoring parameters are upheld.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this initiative is the ability to observe the direct impact of pharmacist-led therapeutic adjustments as each patient was followed up within 2-4 week intervals, as deemed clinically necessary, until stable. Due to the limited timeframe of this initiative, the primary focus of this article is on appropriate ICS de-escalation. By recommending regular follow-up beyond the duration of the initiative, the clinical pharmacist was able to establish a rapport with this patient population, many of whom would have been lost to follow-up until a significant clinical event, such as hospitalization, occurred. This further ensures the stability of the patient’s COPD symptoms despite changes in inhaler use. Additionally, the initiative highlights the pharmacist’s role in ensuring timely updates to key labs and PFTs, which further support any necessary adjustments in inhaler regimens. For example, an EOS of less than 300 cells/µL provides supporting evidence for ICS de-escalation. The majority of patients identified as candidates for ICS de-escalation also required updated monitoring parameters. The pharmacist was easily able to order the testing procedures and labs under their scope of practice. Additionally, with the scope of practice, clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) were able to adjust COPD therapies using their clinical judgment and guidelines. Lastly, the initiative benefited from collaboration with in-house pulmonologists on complex cases, and pharmacists had the opportunity to refer patients when deemed necessary.

While this initiative provided valuable insights into pharmacist-led depre-

scribing of ICS inhalers, it had several limitations. Strict exclusion criteria limited the target population available. Additionally, as this was a quality improvement initiative conducted without IRB approval, we were unable to evaluate the incidence of exacerbation, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits following medication adjustments.

In future endeavors, expanding the number of pharmacist practitioner clinics involved could enhance the patient pool. Moreover, conducting further investigation in a larger facility with more resources or expansion of the total number of CPP clinics could strengthen the findings presented in this article. Establishing a research project with IRB approval would also facilitate the exploration of human outcomes.

Conclusion

Data from this initiative demonstrates that pharmacist-led deprescribing of unnecessary ICS-containing inhalers can be incorporated into clinics, enabling pharmacists to identify patients requiring closer monitoring and updated laboratory tests, including PFTs and EOS count.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT:

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of the facilities at the Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Coastal Healthcare System, Fayetteville, NC. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, or any of its agencies.

Authors: Jessica Parks, PharmD, PGY-2 Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Resident, VA Fayetteville Coastal Health Care; Corresponding author Jessica.Parks2@ va.gov; Amber Jefferson, PharmD,

Women’s Health Clinical Pharmacist Practitioner; Lauren Howard, PharmD, BCPS, Patient Aligned Care Team Clinical Pharmacist Practitioner; Cassandra Warsaw, PharmD, Anticoagulation Clinical Pharmacist Practitioner/Academic Detailing

References

1. Liu Y, Carlson SA, Watson KB, Xu F, Greenlund KJ. Trends in the Prevalence of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years - United States, 2011-2021. MMWR 2023;72(46):1250-1256. Published 2023 Nov 17. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7246a1

2. Terry PD, Dhand R. The 2023 GOLD Report: Updated Guidelines for Inhaled Pharmacological Therapy in Patients with Stable COPD. Pulm Ther. 2023;9(3):345-357. doi:10.1007/s41030-023-00233-z.

3. Patil T, Ali S, Kaur A, et al. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Heart Failure Clinic on Optimization of Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (PHARM-HF). J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2022;15(6):1424-1435. doi:10.1007/ s12265-022-10262-9

4. Khdour MR, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, McElnay JC. Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):588-598. doi:10.1111/j.13652125.2009.03493.x

5. Hegland AJ, Bolduc J, Jones L, Kunisaki KM, Melzer AC. Pharmacist-Driven Deprescribing of Inhaled Corticosteroids in Patients with Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):730-733. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-871RL

6. Va/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline. (2021). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Figure 1. Flow of patient population evaluation for enrollment criteria

Patients identified with ICS and diagnosis of COPD (n = 123)

Patients met enrollment criteria (n = 54)

ICS deprescribing inappropriate (n = 5)

PFTs revealed asthma/COPD overlap (n = 5)

Lost to follow -up (n = 6)

Declined deprescribing of ICS (n = 5)

$2515

raised of $25,000 goal

HELP SHAPE THE NEXT 25 YEARS OF PHARMACY IN NORTH CAROLINA

HELP SHAPE THE NEXT 25 YEARS OF PHARMACY IN NORTH CAROLINA

Support NCAP’s Grassroots Advocacy Work! Support NCAP’s Grassroots Advocacy Work!

Donate Now

Thank You To Our Generous 2025 Donors! Thank You To Our Generous 2025 Donors!

Allison Fay

Anna Everhart

Brooke Masten

Dawnn Flowers

Glenn Herrington

Kaleigh Collins

Leigh Foushee

Matthew Kelm

Pamela Shelton

Shayna Cole

Thomas Henry

Arpit Bhatt

Benjamin Small

David Phillips

Elizabeth Caveness

Jeffrey Jackson

Kayla Marvin

Lindsey Kennedy

Melissa Dinkins

Ryan Mills

Stephen Dedrick

Thomas D’Andrea

Zach Krauss

Amanda Rooney

Benjamin Smith

Dustin Wilson

Elizabeth Oldham

Joseph McDowell

Leslie Barefoot

Lisa Padgett

Michelle Fritsch

Robert Rawls

Theresa Egan

William McSkimming

Expansion of a Pharmacist-Led Long-Acting Injectable Service Across a Large Health System

By: Dr. Katelyn Hernandez, Dr. Geena Eglin, and Dr. Jamie Shaver

Introduction

Long-acting injectable (LAI) medications have become viable treatment options for the management of several chronic disease states in the outpatient setting. (1,2) These medications improve patient adherence to complex regimens, yielding improved outcomes. (1) For example, in a systematic review comparing oral antipsychotics with LAI antipsychotics, the researchers found that there were fewer hospitalizations and emergency department admissions, as well as a higher likelihood of adherence within the LAI group compared to the oral antipsychotic group. (3)

Still, there can be several barriers to obtaining LAI medications. (4) An ethnographic research study conducted among patients, psychiatrists, nurses, therapists, and other clinical staff illustrated various barriers to LAI medication administration, including clinic infrastructure, appropriate/sufficient patient support, and staff education. (4) These are some key areas where pharmacists are well-positioned to bridge the gap in patient care.

Pharmacist-led LAI services offer a solution to such barriers by supporting access to medications through medication education, administration, and cost assistance. Within the Novant Health system, LAI pharmacy services

have been implemented in a primary location (Coastal Region) for several years. With the full integration into the larger system within the last year, the specialty pharmacy program had an opportunity to expand this service across all Regions to increase patient access and support attainment of treatment goals. The aim of this quality improvement project was to expand this established service into additional Regions (Triad and Charlotte) within the health system.

Methods

This was a pre-post study reviewed by the institutional review board and determined to be exempt. The purpose of this study was to expand LAI services across a large health system and to assess LAI appointment completion and prescription fulfillment following expansion.

The study included patients who were prescribed an LAI medication that Novant Health Specialty Pharmacy Services subsequently filled in the Charlotte or Triad Regions. Any Novant Health specialty pharmacists in the Charlotte or Triad Regions were eligible for LAI training. The study consisted of two major phases: training sessions for pharmacists to meet legal standards and the implementation phase, during which the LAI service infrastructure was built.

Phase I – Training Sessions: A training session was held for all specialty pharmacists interested in working within the expanded LAI service. This training session consisted of a didactic and applied learning component. Both components were necessary for completion of the LAI competency, which was built prior to the implementation of the Coastal Region LAI service. Following completion of the competency, pharmacists can independently administer LAI medications. During the didactic portion, pharmacists were educated on the regulatory requirements related to pharmacist LAI administration and the documentation process. This was conducted via an in-person presentation, with a virtual option for participants who could not be on site. The educating pharmacist presented the didactic portion, and participants had a virtual copy of the presentation as a reference. The applied learning component consisted of the pharmacists autonomously documenting the existing LAI workflow on a test patient within the electronic medical records (EMR) test environment. The pharmacists then performed both subcutaneous and intramuscular injection techniques using an injection practice pad. Previously trained LAI pharmacists evaluated each participant as they performed the injections; if performed adequately, according to internally created competency requirements,

the pharmacist was then certified as a LAI-administering pharmacist. Participants utilizing the virtual option did not complete the applied learning component on the training session date; instead, this was completed at a later date. This session confirmed the requirements set forth by the North Carolina Board of Pharmacy (NC BOP) to be deemed a LAI-certified pharmacist.

Phase II - Implementation: The implementation phase of the study was initiated following the completion of all required training sessions. Communication materials outlining the available LAI service within new Regions of the health system were created and disseminated to providers via email and the EMR. Patients were eligible if they received any LAI medication through the Novant Health Specialty Pharmacy. A monthly report through Slicer Dicer software within the EMR was created and utilized to collect data from February 1st, 2025, through April 30th, 2025. This report included the number of LAI appointments completed, the number

of LAI prescriptions, and the number of unique patients seen in each LAI pharmacist service in the Charlotte and Triad Regions.

Results

Training Session: A total of seventeen pharmacists completed the didactic training session for LAI administration certification. Of these pharmacists, fourteen completed the competency required to administer LAI medications independently. Three of the pharmacists attended virtually and were therefore unable to complete the full applied learning section of the competency. Of the fourteen pharmacists who completed the competency, eight were from the Charlotte Region and six from the Triad Region.

Implementation: The LAI service appointment completion and prescription fulfillment for the Charlotte Region during the study period can be found in Table 1. During the study period, there were zero LAI appointments in the Triad region.

Discussion

The LAI training session resulted in an increased number of LAI-trained pharmacists within the health system who meet NC BOP certification requirements. LAI service sites were newly established in two different regions across the health system. Because the training session allowed for virtual attendance, not all pharmacists were able to complete the competency. However, since the end of the study period, sixteen out of the seventeen pharmacists who attended the session have completed the required applied learning component for the competency.

Within the Charlotte Region, LAI appointment completion and prescription fulfillment increased in April, likely due to increased provider awareness through communication from specialty pharmacists and management. Additionally, a flyer outlining the new service was created and disseminated to providers to raise awareness further.

Table 1. Monthly Appointment Data for Charlotte Region

The rate of growth of appointment completion seen in the Charlotte Region during the study period is consistent with the rate of growth seen when the LAI service was first implemented in the Coastal Region. The growth of the service in the Triad Region was initially delayed due to a lack of established location and space limitations for LAI service appointments. Since the completion of the study, the Triad Region LAI service site has become fully operational, holding LAI medication administration appointments.

Overall, since the conclusion of the study, there have been thirteen appointments in the Charlotte Region and one appointment in the Triad Region. Most of the medications administered have been biologics, with a small number of cholesterol-lowering injectable medications.

There was one main limitation of this study to note. Within the Charlotte Region, the LAI service site was not centrally located to the patient population it aimed to serve, deterring them from utilizing the LAI service. Since this limitation was identified, it has been mitigated by developing another site in the Charlotte Region that is more centrally located. An area of opportunity for future implementation of new services was noted during the study period. During this study, education of providers on the new service did not begin until the LAI service site was fully implemented, which likely led to slower growth. It would be beneficial for health systems that would like to implement a similar service to provide education and awareness of the upcoming service in advance of implementation to help facilitate quicker growth.

There is limited research discussing the impact of pharmacist-led LAI services on patient outcomes. However, previous research has shown that patients feel comfortable having LAI medications administered within a

community pharmacy and found the service convenient.5 Future research will seek to evaluate clinical outcomes among patients receiving LAI medications through a pharmacist-led service versus a medical office.

This study demonstrated that implementing an LAI service is feasible, leading to the growth of pharmacy-led clinical services.

Authors: Katelyn Hernandez, PharmD; PGY-2 Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Resident, Novant Health New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Katelynn. hernandez@novanthealth.org (Corresponding); Geena Eglin, PharmD, BCACP, CSP, CPP, Novant Health New Hanover Regional Medical Center; and Jamie Shaver, PharmD, BCACP, Director, Specialty Pharmacy, Novant Health New Hanover Regional Medical Center

References

1. Krishna A, Goicochea S, Shah R, Stamper B, Harrell G, Turner A. A Comprehensive Guide to Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics for Primary Care Clinicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(4):773-783.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.220425R2

2. Wang W, Zhao S, Wu Y, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Long-Acting Injectable Agents for HIV-1: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e46767. Published 2023 Jul 27. doi:10.2196/46767

3. Lin D, Thompson-Leduc P, Ghelerter I, et al. Real-World Evidence of the Clinical and Economic Impact of Long-Acting Injectable Versus Oral Antipsychotics Among Patients with Schizophrenia in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [published correction appears in CNS Drugs. 2021 Aug;35(8):923. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00850-9.]. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(5):469-481. doi:10.1007/ s40263-021-00815-y

4. Robinson DG, Subramaniam A, Fearis PJ, et al. Focused Ethnographic Examination of Barriers to Use of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(4):337-342. doi:10.1176/appi. ps.201900236

5. Mascari LN, Gatewood SS, Kaefer TN, Nadpara P, Goode JR, Crouse E. Evaluation of patient satisfaction and perceptions of a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication administration service in a community-based pharmacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(4S):S29-S34. doi:10.1016/j. japh.2022.01.016

Updated Fall 2025 NC MPJE Study Materials Now Available

Getting ready to study for the NC MPJE? NCAP has two study options for you: the NC MPJE Study Guide and the NC MPJE Online Study Course. The updated Fall version of both options became available Oct. 1. To learn more and place your order, visit the NCAP NC MPJE webpage

Sunday Evening Webinars

The Sunday Evening Webinar Series has presented many varied topics so far this year. Our next webinar will be on Sunday, October 19th. Cheryl Viracola, PharmD, NCAP’s Director of Practice Advancement and Dr. Larry Greenblatt, State Health Director NC DHHS will present From Standing Order to Standing Ready: Pharmacists and Influenza Care in NC. Visit our webinar page to learn more and register. This event will be ACPE accredited for 1 hour of live CE for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.

Next Leadership Buzz Discussion

Join the next Leadership Buzz discussion hosted by the New Practitioner Forum. This series is open to all NCAP members who are passionate about personal and professional growth. Whether you’re a recent graduate or a seasoned practitioner, you’ll gain valuable insights, expand your knowledge, and strengthen your professional network. The next discussion is the podcast To Err is Human – Handling Mistakes as a New Practitioner on November 3rd at 6 pm. To learn more and register to attend, visit our website.

Register for Residency Showcase 2025!

Calling all residency programs and fourth year pharmacy students! Join NCAP in Winston-Salem at the Novant Health