Table of Contents

1 3 5 7 14 18 21 50 54 69

Executive Leadership

Editor Letter

NCCO10 Conference Information

Choral Scholarship and the Beloved Community: A Content Analysis of Published Journal Articles

Patrick Freer

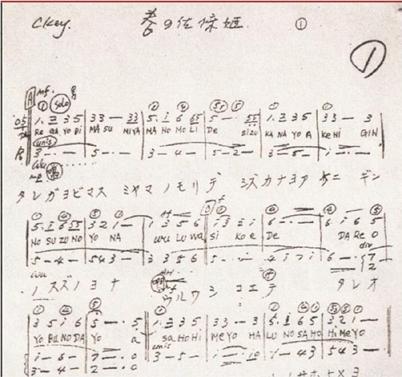

Compositions of Choral Coloniality: The Goddess of Spring by Uyongu Yatauyungana

Hung Wen

Choral Reviews

Nathan Reiff, editor

Contributors: Aaron Peisner

Environmental Activism through Choral Music: John Luther Adams’s Canticles of the Holy Wind

Kirsten Hedegaard

Recording Reviews

Morgan Luttig, editor

Contributors: Tatiana Taylor, Riikka Pietiläinen Caffrey, Corey Sullivan

Considering Matthew Shepard Through the Five Stages of Grief

Nicholas Sienkiewicz

Book Reviews

Andrew Crow, editor

Contributors: Katie Gardiner, Christopher G. McGinley, Dan Wessler

NCCO Executive Leadership

KELLORI DOWER PRESIDENT

Kellori Dower is the Dean of Fine and Performing Arts at Santa Ana College in Santa Ana, California. She was the director of two award-winning high school choral music programs prior to serving as Director of Choral Activities at the collegiate level. Past appointments have also included High School administrator and District Arts Administrator positions. She was the 2016 recipient of the Outstanding Music Educator Award for the California Music Educators Association. She is an active choral composer, adjudicator and clinician. Dr. Dower’s work and research regarding culture and music lead to the creation of collegiate courses in Rap and Hip Hop, Gospel Music and African American folk compositions.

KATHERINE FITZGIBBON PRESIDENT-ELECT

Katherine FitzGibbon is Professor of Music and Director of Choral Activities at Lewis & Clark College, where she conducts two of the three choirs, teaches courses in conducting and music history, and oversees the voice and choral areas. Dr. FitzGibbon founded Resonance Ensemble in 2009, a professional choral ensemble presenting powerful programs that promote meaningful social change. Dr. FitzGibbon has also served on the faculty of the summertime Berkshire Choral International festival and conducted choirs at Harvard, Boston, Cornell, and Clark Universities, and at the University of Michigan. She was a previous member of NCCO’s National Board and Mission and Vision in Governance Committee.

ELIZABETH SWANSON VICE PRESIDENT

Elizabeth Swanson is the Associate Director of Choral Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she is the conductor of the University Choir and CU Treble Chorus, teaches courses in conducting, and serves on master’s and doctoral committees. Dr. Swanson is an active guest conductor, clinician, and adjudicator throughout the United States with events planned in Arkansas, Colorado, Hawaii, Minnesota, and New York City this year. She is currently serving in her second term as NCCO’s Vice President on the Executive Board; additionally, she is honored to have served as the chair of NCCO’s inaugural Mission & Vision in Governance Committee. Her degrees are from Northwestern University (D. Mus. Conducting), Ithaca College (MM Conducting), and St. Olaf College (BME).

MICHAEL M C GAGHIE TREASURER

Michael McGaghie serves as Associate Professor of Music and Director of Choral Activities at Macalester College, where he conducts the college’s two choirs and teaches courses in conducting, musicianship, and Passion settings from Bach to the present. He also directs the Isthmus Vocal Ensemble and the Harvard Glee Club Young Alumni Chorus. His recognitions from ACDA include an invitation to conduct the Macalester Concert Choir at the 2016 North Central division conference, an ICEP fellowship to China, and the Julius Herford Prize. Prior to his elected term as Treasurer, Dr. McGaghie served on NCCO’s National Board and as an inaugural member of the Mission and Vision in Governance Committee.

MARIE BUCOY-CALAVAN SECRETARY

Marie Bucoy-Calavan has been Director of Choral Studies at The University of Akron since 2014, where she conducts Chamber Choir, Concert Choir, and teaches undergraduate– and graduate-level conducting and choral literature. She serves as secretary on Chorus America’s Board of Directors and as coordinator and chair for University Repertoire and Resources, Ohio Choral Directors Association. Bucoy-Calavan finished her BA and MM at California State University, Fullerton, and completed her DMA in Choral Conducting at the University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music.

JACE SAPLAN DIRECTOR OF AFFINITY GROUPS

Associate Professor Jace Kaholokula Saplan (they/he) serves as Director of Choral Activities and Associate Professor of Music Learning and Teaching and choral conducting at Arizona State University where they oversee the graduate program in choral conducting, conduct the ASU Concert Choir, and teach courses in choral literature and pedagogy that weave decolonial and critical theories with communal vocal practice. Recently, Saplan was named as the third artistic director of the Choral Arts Society of Washington (Choral Arts DC). As a Kanaka Maoli advocate, artist, and culture bearer, Saplan is also the artistic director of Nā Wai Chamber Choir, a vocal ensemble based in Hawaiʻi dedicated to the preservation, propagation, and innovation of Hawaiian choral music.

ANGELICA DUNSAVAGE CHIEF EDITOR OF PUBLICATIONS

Dr. Angelica Dunsavage (she/they) serves as Assistant Professor of Music and Director of Choirs at Tennessee State University, where she conducts the TSU University Choir and the Meistersingers and teaches courses in conducting and music education. Prior to her appointment at TSU, Angelica taught music education and choral/vocal classes at Washington State University. She received her DMA in Choral Conducting and Music Education from University of Arizona, her MM in Choral Conducting from Bowling Green State University, and her BS in Music Education from Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Being the Change We Seek

Angelica Dunsavage

Iam honored to write this, my first letter as Chief Editor of Publications for The Choral Scholar and American Choral Review . First, I would like to thank Mark Nabholz, previous editor, for his guidance as well as the current NCCO Executive Board for entrusting this publication to myself and the editorial board. I would also like to introduce new members and positions to our editorial board:

• Jace Saplan has shifted their role as previous Associate Editor for Recording Reviews to a new column dedicated to Affinity Group and ADEI-based work. This new column premieres in this edition.

• Morgan Luttig has joined the board as Associate Editor for Recording Reviews

• Nathan Reiff has joined the board as Associate Editor for Score Reviews

• Michael Porter is taking on the work of our newly combined publication as Associate Editor for the Research Memorandum Series. This addition to The Choral Scholar will be published annually to include dissertation and thesis abstracts from recent masters and doctoral students.

• To aid authors in developing topics and writing style, the editorial board has invited a team of Editorial Mentors. These mentors are available upon request to provide feedback and direction for completed articles, or ideas in progress. Our three Editorial Mentors are Hilary Apfelstadt, Edward Maclary, and Magen Solomon.

Merriam Webster defines scholarship as “the character, qualities, activities, or attainments of a scholar.” Why then, does the practice of scholarship so often get reduced to a word count, formatting style, topic, or publication type? With this reflection comes the acknowledgement that the choral field has a history of preference to certain scholarship, and scholars, at the exclusion of others. The Choral Scholar, with the support of the Mission, Vision, and Governance committee, is committed to opening the door to scholarly expression in a way that is equitable, diverse, and responsive to the needs of 21st-century choral scholars. In this framework, we are excited to announce the following changes to our submission guidelines present on our website, https://nccousa.org/publications/the-choral-scholar-americanchoral-review:

• Peer-reviewed articles will remain a feature of this publication. Authors who wish to submit completed articles for peer

“Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” —Barack Obama

announce the following changes to our submission guidelines present on our website, https://nccousa.org/publications/the-choral-scholar-americanchoral-review:

review are encouraged to do so but will have the option for additional feedback from an Editorial Mentor if requested.

• Peer-reviewed articles will remain a feature of this publication. Authors who wish to submit completed articles for peer review are encouraged to do so but will have the option for additional feedback from an Editorial Mentor if requested.

• Submissions are now open for article ideas and works in progress. We would like to hear from a growing number of authors, particularly those who may have been uninspired to submit an article, and commit to guiding groundbreaking ideas into publication.

• Submissions are now open for article ideas and works in progress. We would like to hear from a growing number of authors, particularly those who may have been uninspired to submit an article, and commit to guiding groundbreaking ideas into publication.

• The Choral Scholar will be expanding to include new methods of scholarship, including interviews, videos, creative writing, and podcasts. If you have an idea to share, or want to get involved, please see our website or email editor@ncco-usa.org

• The Choral Scholar will be expanding to include new methods of scholarship, including interviews, videos, creative

to share, or want to get involved, please see our website or email editor@ncco-usa.org

The Choral Scholar and American Choral Review is a reflection of NCCO: it is our organization’s mission and vision put into the practice of research. As such, this edition challenges us to move forward into change. Patrick Freer’s article A Beloved Community reminds that there is much work to be done to align the choral field’s values with its research. Kirsten Hedegaard’s article Environmentalism through Choral Music highlights how choral music can be a message for social change. Nicholas Sienkiewicz combines psychology with musical analysis to unpack the emotional impact of Considering Matthew Shepard. We hope that this publication continues to expand possible and change we seek.

The Choral Scholar and American Choral Review is a reflection of NCCO: it is our organization’s mission and vision put into the practice of research. As such, this edition challenges us to move forward into change. Patrick Freer’s article A Beloved Community reminds that there is much work to be done to align the choral field’s values with its research. Kirsten Hedegaard’s article Environmentalism through Choral Music highlights how choral music can be a message for social change. Nicholas Sienkiewicz combines psychology with musical analysis to unpack the emotional impact of Considering Matthew Shepard We hope that this publication continues to expand what is possible in choral scholarship and be the change we seek.

Sincerely,

Sincerely,

Angelica Dunsavage Chief Editor of Publications Angelica Dunsavage Chief Editor of PublicationsApply to Present or Perform at NCCO10*

The National Collegiate Choral Organization announces its 10th Biennial Conference, “Coming Home,” to be hosted by Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, November 9–11, 2023.

After four years apart, this conference will provide in-person opportunities for professional development and connections with peers. We will address new challenges facing our students, our programs, and our own well-being. We will share ideas that serve many types of post-secondary institutions. We will once again enjoy live performances of wonderful repertoire! Perhaps most importantly, we will celebrate our accomplishments and the joys of our profession.

We look forward to coming back home to our NCCO community.

*Most applications due May 1, with decisions by June 15.

Calls for Participation

We warmly invite all individuals from choral and related fields to share their expertise. Each call will be adjudicated by a panel of NCCO members. Applicants must be active members of NCCO, so we encourage you to join or renew today. Our membership rates continue to be the lowest in the profession for both regular and student members.

The conference will also include a plenary panel hosted by Dr. David Morrow (Morehouse College) with arts leaders from across the Atlanta University Center consortium of HBCU institutions, as well as performances by our hosts and special guests. NCCO will announce headliners and invited choirs in the early summer.

Please consider applying for the following opportunities.

DUE MAY 1 ST

Choral Performance

Interest Sessions

Panel Participation

“Considering Collegiate Choral Excellence”

“Reframing Workloads and Professional Evaluation”

DUE JULY 1 ST

Poster Sessions

APPLICATIONS OPENING THIS SUMMER

Graduate Student Conducting Fellowship

Choral Scholarship and the Beloved Community: A Content Analysis of Published Journal Articles

Patrick FreerThe article reports findings from a study purposed toward examining if, and how, the tenets of Beloved Community have been reflected in published choral research. The 2022 National Conference of the National Collegiate Choral Association (NCCO) reflected a response to the wave of civil unrest that followed the murder of George Floyd by police officers in May 2020. Coinciding with the period COVID-19 lockdowns, the unrest highlighted other instances of brutality attributed to race, including the killing of Rashard Brooks in Atlanta. The NCCO conference was set to take place in 2021 at Atlanta’s Morehouse College, a historically black institution; it was instead held virtually in 2022.

The conference theme honored Morehouse graduate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s conception of Beloved Community, described by the King Center as:

a global vision in which all people can share in the wealth of the earth. In the Beloved Community, poverty, hunger and homelessness will not be tolerated because international standards of human decency will not allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.1

1 “The King Philosophy,” accessed October 4, 2022, https:// thekingcenter.org/about-tkc/the-king-philosophy/.

The call for NCCO conference proposals directed presenters to examine the organization’s statement of mission and values. The call included the following text referencing the principles of Beloved Community:

Our conference theme is rooted in the work we have done over the past year to unearth the stories of our choral world, identifying where we have erred and where we have room to grow. In Building Beloved Community, we agree to take on the work of care for one another, while acknowledging that we can only offer our deepest artistry and most impactful pedagogy when we feel safe to be ourselves. The NCCO9 conference planning team welcomes proposals from our membership for our presentations in all areas that amplify this message of connection and empathy.2

This study consisted of a content analysis of peer-reviewed articles appearing in the research journals, since inception, of the National

Collegiate Choral Organization (the Choral Scholar & American Choral Review) and the American Choral Directors Association (the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing) for topics and themes consistent with the values emerging as important to the profession in the current era of cultural unrest and distrust. Though ACDA’s Choral Journal also publishes scholarly articles, the two journals reviewed for this project are the associations’ designated research publications. The International Journal of Research in Choral Singing is the scientific research journal of the American Choral Directors Association.3 Founded in 2002, the journal has encouraged researchbased understandings that promote mutually informative conversation among scientific, artistic, and pedagogical orientations to choir singing. The Choral Scholar & American Choral Review, first published in 2009, is the scholarly journal of the National Collegiate Choral Organization. 4 The study purpose was to determine if, to what extent, and how the content of these journals reflected the conference themes, including Beloved Community.

Method and Procedures

The researchers were a university professor and an undergraduate research assistant affiliated with a university in downtown Atlanta. The civil protests of May and June 2020 took place in the immediate blocks around the university’s School of Music, with some of the music buildings sustaining damage during the events. The study was developed in the aftermath of the protests. The study’s author was a 56-year-old white male professor, and the undergraduate student was a 19-year-old black male who had graduated a year earlier from a local high school. Both used

3 “International Journal of Research in Choral Singing,” accessed October 4, 2022, https://acda.org/publications/internationaljournal-of-research-in-choral-singing.

4 “The Choral Scholar & American Choral Review,” accessed October 4, 2022, https://ncco-usa.org/publications/the-choralscholar-american-choral-review.

he/him/his pronouns. The student maintained a written record of his personal reflections while the study proceeded; these reflections are excerpted later in this article.

The study proceeded in three phases, in line with previously established protocols for reviews of journal content in the arts and humanities.5 Data collection and analysis followed the model of systematic review developed by Petticrew and Roberts, suggested as an appropriate review method “when it is known that there is a wide range of research on a subject but where key questions remain unanswered.”6 This review included quantitative and qualitative investigations, theoretical writings, historical texts, and commentaries. The sources varied substantially in design, methodological rigor, assessment, and analysis. For this reason, a narrative, synthetic approach 7 was selected as the presentation format for this systematic review.

The first task was to identify the total data set of all items published in the two journals, as displayed on the respective journal websites. The total data set was determined to comprise 151 items. Sixty-four items were published in

5 Patrick K. Freer, “Challenging the Canon: LGBT Content in Arts Education Journals,” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 196 (2013): 45–63. https://doi. org/10.5406/bulcouresmusedu.196.0045; Yu-Pin Huang, Y., Melanie E. Brewster, Bonnie Moradi, Melinda B. Goodman, Marcie C. Wiseman, and Annelise Martin, “Content Analysis of Literature about LGB People of Color: 1998–2007,” The Counseling Psychologist 38, no. 3 (2010): 363-396. doi: 10.1177/0011000009335255; Julia C. Phillips, Kathleen M. Ingram, Nathan Grant Smith, and Erica J. Mindes, “Methodological and Content Review of Lesbian-, Gay-, and Bisexual-Related Articles in Counseling Journals: 1990-1999,” The Counseling Psychologist 31, no. 1 (2003), 25–62.https://doi. org/10.1177/0011000002239398

6 Mark Petticrew, and Helen Roberts, Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 21.

7 David N. Boote, and Penny Beile, “Scholars Before Researchers: On the Centrality of the Dissertation Literature Review in Research Preparation,” Educational Researcher 34, no. 6 (2005): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003; Chris Hart, Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Research Imagination, 2nd ed. (London, UK: Sage Publications, 2018).

the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing (2003–2021), including 52 articles, eight editorials, and four miscellaneous items. Eighty-seven items were published in The Choral Scholar & American Choral Review (2009–2021), 48 articles, 12 editorials, 24 sets of reviews of repertoire, recordings, and/or books, and three miscellaneous items.

The first phase of review consisted of identifying all mentions of content relevant to the study. The total data set of 151 items was screened according to procedures developed by Littell, Corcoran, and Pillai.8 The review examined for both primary and secondary themes. Primary themes were those referenced in the NCCO conference call for proposals, specifically “right-relationships,” “cultural consciousness,” “cultural resilience,” and “culturally responsive teaching/learning.”

These were named directly within the text of the call and/or within the organization’s mission and vision statements.9 The first-phase examination was of all journal content, regardless of article type or peer-reviewed status.

The focus of the second phase was a review for all content related to, but not directly using, those terms. The third phase of the review included more focused examination of all content related to the study’s secondary themes of “caring,” “connection,” “community,” and “empathy.” Analysis followed processes of reflexive thematic analysis.10

Findings and Discussion

Thirteen items (8.6%) in the total data set (N=151) were deemed to reflect elements of “Beloved Community.” All 13 were research articles. Each of the study’s four primary themes was identified within one or more of the 13 articles. These 13 articles, then, each reflected one or more of the study’s secondary themes. These results are shown in Table 1, with the abbreviations “CS” (The Choral Scholar & American Choral Review) and “IJRCS” (International Journal of Research in Choral Singing).

(Table 1 shown on next page.)

Twelve of these 13 articles were published in 2018 or later. There is little recognition or discussion of singers’ race or ethnicity in these articles. It is interesting that issues of race and ethnicity have received relatively little attention from this subset of the choral research community, while 31% of the articles reflecting Beloved Community dealt with issues of singers’ gender and/or sexuality (still only n =4, however). Might this indicate that choral researchers are more comfortable with topics of gender and sexuality than they are with topics of race and ethnicity? Or, might it indicate that choral researchers study what they find familiar, with gender and sexuality being familiar to those in research positions—or, at least more familiar than issues of race and ethnicity?

8 Julia H. Littell, Jacqueline Corcoran, and Vijayan Pillai, Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

9 “Vision & Mission,” accessed October 4, 2022, https://ncco-usa. org/about/vision-mission.

10 Virginia Braun, and Victoria Clarke, Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide (London, UK: Sage Publications, 2021); Virginia Braun, and Victoria Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101.

Within the group of articles focused on gender and sexuality, the topics were addressed exclusively within the paradigmatic theme of Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning. Where current academic conversations often concern the need for a broad cultural consciousness of gender and sexuality, the articles in this collection focused exclusively on pedagogy responsive to the genders and sexualities of students within our choirs. That

Primary

Right-Relationships Connection, Solidarity

CS/ACR Arnold, D. (2020). Serge Jaroff and his Don Cossack Choir: The refugees who took the world by storm.

IJRCS

Cultural Consciousness Empathy, Equality

MacIntosh, H. B., Tetrault, A.,Vallée, J. (2020). “Trying to sing through the tears.” Choral music and childhood trauma: Results of a pilot study.

CS/ACR Zakery, H., Jr. (2021). William Grant Still’s ...And They Lynched Him on a Tree: A performance and reception history.

IJRCS Baker, V. D. (2018). A gender analysis of composers and arrangers of middle and high school choral literature on a statemandated list.

IJRCS Cash, S. (2019). Middle and high school choral directors’ programming of world music.

Cultural Resilience Community, Integration

CS/ACR Crowe, D. R. (2021). Retention of college students and freshman-year music ensemble participation.

IJRCS Brown, T. R. (2012). Students’ registration in collegiate choral ensembles: Factors that Influence continued participation.

Culturally Responsive Teaching & Learning Caring, Inclusion

CS/ACR Saplan, J. (2018). Creating inclusivity: Transgender singers in the choral rehearsal.

IJRCS Parkinson, D. J. (2018). Diversity and inclusion within adult amateur singing groups: A literature review.

IJRCS Latimer, M. E., Jr. (2008). “Our voices enlighten, inspire, heal and empower:” A mixed methods investigation of demography, sociology, and identity acquisition in a gay men’s chorus.

IJRCS Cates, D. S. (2020). Music, community, and justice for all: Factors influencing participation in gay men’s choruses.

IJRCS Howard, K. (2020). Knowledge practices: Changing perceptions and pedagogies in choral music education.

IJRCS Killian, J. N., Wayman J. B., Antoine, P. M. (2021). Choral directors’ self-report of accommodations made for boys’ changing voices: A twenty-year replication.

may be reflection of the pedagogical work that choral conductors do daily. It may reflect the ease with which choral researchers have access to specific populations of students, requiring relatively simple approval processes from university research bureaus. Or, it may simply demonstrate the interest of choral conductors in the improvement of the craft of rehearsing and preparing singers for high level music making.

Smaller sets of articles addressed the other three themes related to Beloved Community. RightRelationships have been defined as those based on “honesty, trust, mutual respect, and love…with [re-examination] of prejudice and exclusion.”11

The two articles in this set addressed very different elements of “righting” relationships, with one article dealing with choral music’s role in the healing of relationships after trauma, and the other describing choirs as connections between different peoples.

The theme of Cultural Resilience backgrounded two articles exploring issues of transition, recruitment, and retention in choral music at the tertiary level. The theme is relevant to these articles because both studies yielded results indicating that when not required by their major, students enroll in choral ensembles due, chiefly, to the social component of group singing. This is supported by Cultural Resilience’s secondary themes of community and integration; both address the emotional and social connections afforded by a shared sense of cultural-community milieu.

empathy and equality. The term “empathy” is derived from the German “Einfühlung” (or “feeling into”),12 through with a stance where conductors are obliged to “to keep an emotional distance, avoid the presumption of total understanding, and retain a position of analytical curiosity.”13

Colleen Kirk, longtime choral conductor at Florida State University, once outlined choral conductors “must be thoroughly grounded in musicianship sensitivities and understandings, care about the singers and their concerns, be alert to cues which reveal the interests and growth of choir members, and be sensitive to time and to comfortable rehearsal and concert pacing.”

14 The studies reported in the articles comprising this subgroup examined the genders of composers and arrangers on lists of contest-required choral repertoire, how choral conductors approach the programming of world music, and the socio-political and critical response to repertoire that challenges performance norms and/or sensibilities. The secondary themes of empathy and equality linked these three articles, as each sought to heighten the profession’s awareness of how decisions of pedagogy and performance impact perceptions of our choral programs for institutions, for audiences, and, principally, for singers.

Student Reflection

This study’s undergraduate research assistant wrote a reflection paper at the conclusion of the project. He wrote as a new college music major, as a high-performing choral singer, and as a person of color (POC). This student’s words give context

The final primary theme, Cultural Consciousness, referred to a process of becoming aware (conscious) of others’ values, histories, and experiences. The related secondary themes were

11 “Covenant of Beloved Community,” accessed October 4, 2022, https://wp.buf.org/covenant-of-beloved-community/.

12 “Empathy,” accessed October 4, 2022, https://plato.stanford. edu/entries/empathy/.

13 Patrick K. Freer, “The Successful Transition and Retention of Boys from Middle School to High School Choral Music,” Choral Journal 52, no. 10 (2012): 10. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/23560678.

14 See Patrick K. Freer, “The Conductor’s Voice: Working Within the Choral Art,” Choral Journal 48, no. 4 (2007): 36. https:// doi.10.2307/23557622

to both the study and to his experiences within choral music at the tertiary level. The following is excerpted from the longer essay:

I was about to enter my freshman year of college with a major in music education and a passion for choral singing. As my view of the world started to sharpen, in part due to the social unrest that occurred in Summer 2020, I started to analyze everything around me on a racial and cultural spectrum. I couldn’t help but notice the lack of diversity in my high school’s choir program. It seems that POC students are enrolling in choir in fewer and fewer numbers. As I have talked with many of my POC classmates about why they chose to leave choir, they are almost synonymous in their response: lack of inclusivity.

Inclusivity in the choral setting is not an easy task, especially when POC’s make up such a small percentage of choral directors at the high school and collegiate levels. While this can be a touchy or sensitive topic to discuss, it is most certainly one that needs to be talked about. It astonished me that there has been so little research found in the two journals we examined for this project.

I feel there are two main steps choral directors should take here. The first is to re-establish their program (classroom) as a safe space at the beginning of each new year. The second step is harder because it involves history, society, and long-standing tradition: re-consideration of repertoire. Choral music is so much more than one time period, or one group of people from the same demographic. The beautiful thing about music is that it can allow freedom of expression and develop camaraderie for people across a multitude of cultures and backgrounds.

It is imperative that the diverse world that we live in is represented through the choices in our repertoire. This is critically important for POC choral students. It goes beyond the repertoire on the concert. It acknowledges the soul of the choir.

Several of the 13 articles identified in this study bore findings relevant to this student’s comments. Among these, Parkinson offered in a note that “research into diversity and inclusion within the field of music education has tended to focus on the inclusion of individuals with special needs and there is little that considers wider aspects of inclusion.”15 Howard reported choral conductors’ perceptions of the pressure they experience in the public arenas of education and musical performance: “Choral music educators often referenced a fear of making mistakes or of causing offense as main barriers to trying new techniques, sounds, repertoire, and growing their personal understandings of the sociocultural context of the music cultures their groups perform.”16 While Crowe opened their article with a summary of studies that had examined how retention rates might be improved for POC, neither Crowe’s study nor its discussion addressed racial or cultural diversity in any manner.17 Zackery, in his advocation for performance of Still’s ...And They Lynched Him on a Tree wrote, “We find ourselves grasping the ramifications of systemic inequities and forms of ‘lynching’ on different types of ‘roadside trees,’ as the Black Lives Matter Movement and pleas for meaningful change grow louder and stronger.”18

15 Diana J. Parkinson, “Diversity and Inclusion within Adult Amateur Singing Groups: A Literature Review,” International Journal of Research in Choral Singing 6 (2018): 42.

16 Karen Howard, “Knowledge Practices: Changing Perceptions and Pedagogies in Choral Music Education,” International Journal of Research in Choral Singing 8 (2020): 13.

17 Don R. Crowe, “Retention of College Students and FreshmanYear Music Ensemble Participation,” The Choral Scholar and American Choral Review 59, no. 1 (2021): 75–82.

18 Harlan Zackery, Jr., “William Grant Still’s ...And They Lynched Him on a Tree: A Performance and Reception History,” The Choral Scholar and American Choral Review 59, no. 1 (2021): 13.

Summary and Implications

This analysis suggests that article content broadly related to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s concept of Beloved Community is not prevalent in the Choral Scholar & American Choral Review and the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing . Only 13 of 151 items published in the two journals were found to reflect themes associated with Beloved Community, though 12 of these were published in the last four years under consideration. It appears that recent choral researchers have recently begun to address related topics. Further research might examine journals of choral practice, such as Choral Journal, with a similar study design. It would be interesting to know if choral researchers influence practice, or if choral practice influences decisions of research topic and study design. Additional research might seek to identify the affiliations of study authors to understand whether related journal content is being generated at the doctoral level, or by choral conductors employed within higher education. Do working choral conductors have the contractual time and career latitude to conduct these types of studies? If not, do they need to consciously direct their doctoral students toward studies addressing issues of Right-Relationships, Cultural Consciousness, Cultural Resilience, and Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning in our profession? Choral scholars might begin by focusing their work on several of this study’s secondary themes, including connection, equality, integration, and caring.

Nel Noddings’ (1929–2022) conception of care provides an apt encapsulation of the relationship between Beloved Community and the choral work of conductors, composers, and choristers. Noddings asked, simply, “What does it mean to care and be cared for?”19 In terms of moving from theory to practice, Noddings advised that, “Our efforts must, then, be directed to the maintenance of conditions that make caring difficult.”20 Choral conductors and choral researchers might consider whether the word “maintenance” can be correctly applied to our profession, or whether we might consider instead that our efforts must, then, be directed to the transformation of conditions that make caring difficult. That is, indeed, the vision of Beloved Community.

— Patrick K. Freer

Patrick Freer is Professor of Music at Georgia State University where he conducts the Tenor-Bass Choir and directs the doctoral programs in music education. Dr. Freer has held Visiting Professorships at the Universität Mozarteum Salzburg (Austria) and at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain), and has been in residence as a guest conductor for the Bogotá Philharmonic Orchestra (Colombia). His degrees are from Westminster Choir College and Teachers College-Columbia University. Dr. Freer is Editor of the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing and former longtime editor of Music Educators Journal.

19 Nel Noddings, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education (University of California Press, 1984): 3.

20 Noddings, Caring, 5.

As the Director of Affinity Groups for NCCO and the Affinity Group Column Editor for the Choral Journal, I am excited to bring responsive and sustainable voices and approaches to embodying Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Access, and Belonging to our field that bridges theory and practice. This column will feature voices and perspectives that assist us in expanding our practice in informed and nuanced ways.

This issue we highlight contributions from our Asian/Pacific Islander Affinity Group and feature composer, culture bearer, and choral musician Hung Wen, who discusses the impact of colonization on Taiwan’s approach to choral musicking and shares with us her research of Taiwanese Tsou composer, Uyonge Yatauyungana and his work, The Goddess of Spring.

—Jace SaplanCompositions of Choral Coloniality: The Goddess of Spring by

Uyongu Yatauyungana Hung WenWhat is Taiwanese choral literature?”

I started to think about this question because choral music or choir is not a traditional music form for the Taiwanese that lived five hundred years ago. But now, we do feel familiar with the choral repertoire. The idea for choral music and choir should wait until the 15th century. After the Discovery of age, two western countries ruled parts of the west coast of Taiwan, the Spanish and the Dutch. They brought missionaries and church music into the island, so the ancestors started to know this new music genre and singing style. However, not until the early 20th century, Taiwanese starts to learn choral music by the later government force. In addition, the choir was used to educate Taiwanese from elementary to high school, and people gradually forgot or became unfamiliar with the traditional vocal music and singing style. The paper discusses the colonial construction in a choir piece composed by a Taiwanese indigenous composer by understanding Taiwan’s regime history and how it is influenced in choral works.

Taiwan is between two mainland, China and Japan. It is also adjacent to the Philippine Islands across the Bashi Channel. From a geopolitical perspective, Taiwan is located in the central area of the East Asian Island arc, which is a vital hub for Asia-Pacific trade transportation and an important military strategic location. Starts from 15th century, Taiwan has always been ruled, under control, or even colonized by outsiders. After WWII, Taiwan had been returning back from Japanese government to China (Republic of China). In 1949, the Republic of China government evacuated from mainland China and entered Taiwan after the Chinese Civil War. To fight against the Chinese Communist Party, The

Declaration of Martial Law began in the early period when the Republic of China (R.O.C.) government moved to Taiwan. During the time, the government promoted the Chinese Cultural Renaissance, causing the second fault in the inheritance of the local Taiwanese and aboriginal culture. 1 Martial law was lifted in 1987, and local awareness rose. Taiwan’s government also completed the first peaceful party rotation in 2000.

After the Chinese Civil War in 1949, a further 1.2 million people from mainland China entered Taiwan. On the other hand, Taiwanese indigenous comprise approximately 2% of the population and now mostly live in the mountainous eastern part. Although the indigenous peoples have been forced to ban traditional cultural rituals on many occasions, they still retain their language, practices, costumes, and traditional beliefs.

At present, the ethnic population of Taiwan is generally divided into Taiwanese and native Taiwanese. The former is Han, mainly from mainland China. The latter are indigenous people; currently, there are 16 ethnic groups officially recognized. Han Chinese makes up over 95% of the population, mainly are Fujian and Hakka.

Taiwan’s complex historical background and multiculturalism have profoundly influenced the development of choral music. Through the spread of Christianity and the promotion of school education, it has become a popular music genre in Taiwan. Following the government changes in Taiwan’s history and the rejection and absorption

Age of Discovery.

• West coast/plain: 1624 Dutch Formosa

1626 Spanish Formosa

1662 Kingdom of Tungning

1684–1895 under Quing Rule

• East cost/Mountain: Native Taiwanese

1900–1945

• Taiwan under Japan Rule

1949–1987

• The Great Retreat

• Declaration of Martial Law in Taiwan

1990–now

• Repealed Martial Law

• 2000 First Transition of Power

• Choral music become a familiar form and performance style.

• Applied to school (education)

• Use chorus as a medium to condense the national spirit or

• Expressing will to resist the government.

of Western culture, choral music has played a pivotal role in Taiwan’s music ecology. In addition, the chorus is often used as a medium to reflect social patterns and consciousness. The chorus has also become a standard propaganda method of cultural and political ideology through music competitions and concerts.

Uyonge Yatauyungana (July 5, 1908–April 17, 1954) was born during Japanese rule, died during the government of the Republic of China. He is known as a Taiwanese Tsou2 musician and educator. He served as a local officer and a leader of the indigenous autonomous movement in early post-war Taiwan. In 1952, during the White Terror period of martial law, he was accused of treason by the ROC government for claiming indigenous autonomy. In 2020, He was posthumously pardoned by the Transitional Justice Commission. During his college, he began to contact modern Western music theory and literary classics. He also assisted the Russian scholar N. A. Nevskij in compiling a survey of the Tsou language and folk literature of the Tefuye tribe. He later studied Japanese haiku poetry and literature, which influenced his musical appreciation and poetry style. In 1930, he returned to Dabang Primary School to teach and devoted himself to tribal education, health, agriculture, and economy. He also wrote several songs to teach students to sing. His music composition expressed caring for the Tsou and was influenced by the Japanese charm and the Tsou’s folk songs. A small part of the lyrics is written in Japanese, and most are sung in the Tsou language.

The Goddess of Spring is a two-part chorus composed by Yatauyungana in prison. The content expresses the yearning for his wife and hometown. The

2 The Tsou (Chinese:鄒) are an indigenous people of central southern Taiwan. They are one of the Austronesian language groups. Reside in Chiayi County and Nantou County numbered around 6,000, and approximately 1.19% of Taiwan’s total indigenous population, making them the seventh-largest indigenous group.

melodic line is influenced by Japanese Enka (popular songs), and the composition technique is very westernized. He configured many 3/6th intervals, which is not often seen in Tsou folk music. The melody range is not so broad that it is a lyrical piece without many emotional ups and downs. The song was banned from singing until the declaration of martial law was lifted, while his work received significant attention after 1990. Many organizations have used this piece to symbolize freedom and democracy in recent years.

Finally, I want to talk about colonial construction under the piece of the Goddess of Spring . By understanding Taiwan’s political history and composition background, I think the colonial construction of this work is complex and multilayered. First, the composer devoted his life to the revival of Tsou culture. However, under the influence of Japanese culture and Westernization, his music works hardly have the characteristics of Tsou music. Ironically, he wants to use the chorus as a medium to preserve the Tsou language and traditional music. But musical language has long been gradually influenced by the colonial culture: the melody logic is entirely Japanese tunes and accompanied with Western counterpoint. Furthermore, I think he hopes to achieve decolonization through the chorus, but eventually, the essence is to reflect the success of the Japanese colonial ultimately. Ironically, this work was regarded as a forbidden song during the Republic of China government because the style and lyrics are both reminiscent of the Japanese style. It was stigmatized (but the truth is the composer wants to express his feelings for the Tsou.) In the end, Yatauyungana was also shot for treason.

Second, high schools and adult choirs have frequently performed this piece in recent years. “De-Sinicization” has been heatedly discussed in Taiwan in the past ten years. Since 1987, DeSinicization has been a political movement to

reverse the Sinicization policies of the Chinese Nationalist Party after 1947(R.O.C.), which many proponents allege created an environment of prejudice and racism against the local Taiwanese Hokkien and indigenous Taiwanese population, as well as acknowledge the indigenous and multicultural character of the island in Taiwan. It emphasizes Taiwan’s national identity (not the same country as China, But two countries). Under this trend, the Goddess of Spring is regarded as a symbol of freedom, democracy, and a new identity and is used to fight against the stale, old, and the majority of Chinese culture. Undoubtedly, the indigenous identity has also received unprecedented attention. Based on the above explanation, I interpret the extension of colonization as the power changes between mainstream culture and minority culture. The social consciousness of the new generation wants to emphasize Taiwan’s local culture and especially aboriginal culture that is not inherited from mainland China and tries to weaken the connection of traditional Chinese culture. Therefore, the government pays more attention to local artistic works and lists many early indigenous educators and musicians as important intangible cultural heritage. However, I feel a little ironic as a Tsou and a descendent of Yatauyungana.

people, the Tsou is still an endangered culture and a community that is about to face the disappearance of language and tradition. In such an environment, The Goddess of Spring has become a representative of the new generation of Taiwanese decolonization (deSinicization). However, has the decolonization component indeed succeeded from Tsou's perspective? Or has it become another victim of political intention?

Yatauyungana has changed from treason to a national hero because of the difference in time and environment. But for the Tsou people, since the period of Japanese rule, we have never really gotten the right to decide; pessimistically, whether it is Japanese or Han (R.O.C.), it is almost impossible for us to get out of colonial rule construction. Although the evolution of the times and the rise of social consciousness have attracted more and more attention to the issue of aboriginal people, the Tsou is still an endangered culture and a community that is about to face the disappearance of language and tradition. In such an environment, The Goddess of Spring has become a representative of the new generation of Taiwanese decolonization (de- Sinicization). However, has the decolonization component indeed succeeded from Tsou’s perspective? Or has it become another victim of political intention?

The colonial history is very complicated and multi-layered, and as a result, Taiwanese identity cannot be clearly stated from one single angle. In such an environment, I think Yatauyungana's music works faithfully reflect the influence of colonial construction.

The colonial history is very complicated and multilayered, and as a result, Taiwanese identity cannot be clearly stated from one single angle. In such an environment, I think Yatauyungana’s music works faithfully reflect the influence of colonial construction. Finally, I am very appreciative of this paper, which allowed me to deeply re-learn Taiwan’s choral literature, as well as about my cultural identity.

Finally, I am very appreciative of this paper, which allowed me to deeply re-learn Taiwan's choral literature, as well as about my cultural identity.

Choral Reviews

Nathan Reiff, editorLook out for squalls

Hilary Purrington (b. 1990)

SATB div., unaccompanied (c. 4’)

Text: English: The Weekly Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)

Score available from the composer

Recording: University of North Carolina Wilmington Chamber Choir, Aaron Peisner. April 24, 2022.

(credibility and character of the speaker) by proclaiming himself not to be an alarmist or a fraud: “The forecasts are not based on superstition or secrets, but what I know to be real, physical causes.” He appeals to logos (reason) by explaining those physical causes: the alignment of equinoxes of Saturn and Jupiter, which “cause great electric disturbances in our solar system.”

As the effects of climate change become increasingly dire, it is encouraging to see composers and musicians grappling with the subject in both overt and subtle ways. Hilary Purrington’s recent composition, Look out for squalls, sets text from an 1891 Wilmington, NC newspaper article describing the predictions of a “weather prophet.” Both textually and musically, Look out for squalls evokes the destructive power of hurricanes, the urgency of preparing for dangerous weather, and the sometimes illusory nature of information and expertise, without ever veering into the obvious or cliché.

The weather prophet’s words, which Purrington sets selectively, utilize the rhetorical triangle–pathos, ethos, and logos. Beginning with pathos (emotion, values), his opening words appeal to fear: “Look out for squalls beginning in May this year…destructive storms will begin to manifest themselves…and the great battle of the elements will begin in earnest.” He then appeals to ethos

Rather than passing judgment on the weather prophet’s astrological argument, Purrington decides to take his words at face value, matching each section of text with music that enhances and deepens its conviction and leaving the audience to decide what to make of this text. Her initial tempo marking, “With urgency,” along with driving rhythms, unisons that slowly reveal a minor mode, slides of major seconds to unisons, and outbursts of triads, meet the intensity of the weather prophet’s forecasts. The middle section, beginning with the text “I do not desire to create unnecessary sensation about these very great storms,” is inspired by Anglican chant, starting in unison and moving on stressed syllables to non-tonal dissonances, clusters, and triads. In the final section, where the text suddenly becomes celestial, Purrington’s tonal language shifts, becoming more triadic and arpeggiated, with frequent mystical-sounding third relationships

between the triads, becoming more and more distant from its starting point: C major, C minor, A-flat major, F major/minor, D-flat major, G-flat major. Purrington ends the piece with a reiteration of the text “Look out for squalls,” with tonalities shifting between E-flat major and minor and the sopranos sliding on sustained pitches. The final moment of the piece is a cataclysmic-sounding eight-note chord that slides to a mixed majorminor chord, with the upper voices singing E-flat minor over E-flat major in the lower voices. Ultimately, the lower voices cut out, and we are left with E-flat minor.

Performance video: https://www.youtube.com/ watch/?v=Rrc8ikURhuE

Hilary Purrington’s website: https://www.hilarypurrington.com/index.html

— Aaron PeisnerLook out for squalls is most appropriate for an advanced choir. Aside from its final moments, it has minimal divisi, mostly for sopranos and basses. Rhythmically, Purrington frequently switches between duple and triple subdivisions. Her harmonic language never lingers in one place for too long, commonly bouncing between unisons, triads, clusters, and other non-triadic formulations. As a mezzo-soprano with significant choral singing experience herself, Purrington is highly attuned to the needs of singers regarding tonal reference points and preparations of dissonances and melodic leaps, making Squalls achievable and singable.

Look out for squalls was commissioned by the University of North Carolina Wilmington Chamber Choir, and premiered on April 24, 2022. Hilary Purrington holds degrees from the Yale School of Music, the Juilliard School, and Rice University. Recently, her choral-orchestral work, Words for departure , was premiered by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra on a program with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Nathalie Stutzmann conducting.

Link to perusal score: https://issuu.com/hilarypurrington/docs/ purrington_look_out_for_squalls_perusal_score

O Guiding Night Roderick Williams (b. 1965)

SATB div., piano (c. 8:45’)

Text: English: St. John of the Cross (translated by Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez)

Score available from Oxford University Press

Recording (extended version): O Guiding Night: The Spanish Mystics. The Sixteen, Harry Christophers. CORO, COR 16090. April 26, 2011. MP3 or compact disc.

Choral musicians working in the U.S. may be unfamiliar with the impressive musical achievements of Roderick Williams, though an important part of his work applies directly to our own field. Williams, a leading British baritone, enjoys a busy career singing on top opera stages around the world, in recital halls, and in performances of works by Vaughan Williams, Britten, and Elgar, among many others. But he also exemplifies multi-dimensionality as a musician, and his compositional output—largely of choral works—continues to grow. According to his website through Groves Artists, Williams will both sing and have a choral work performed at the Coronation Service of King Charles III in May 2023.

Williams’ choral pieces vary in difficulty and voicings and include arrangements of spirituals (Children, go where I send thee), carols (Coventry Carol ), and original works. His ethereal and otherworldly setting of the Advent O antiphon O Adonai is among his more challenging pieces, particularly given the highly exposed material for sopranos, but is deeply moving.

Commissioned by the UK’s Genesis Foundation for Harry Christophers and The Sixteen, O Guiding Night sets an English translation of poetry by the 16th-century Spanish priest and mystic Juan de la Cruz (St. John of the Cross). The poem, the title of which is often translated as “The Dark Night of the Soul,” explores a transition from spiritual aloneness toward unification with the divine. The imagery of Juan’s poetry is both sacred and sensual, referencing God and the transitioning soul as a Lover and the beloved, respectively. An alternate, secular reading of the poem could imagine two human lovers being drawn to one another from afar.

to develop into the final section. Toward the end of the text, the speaker describes the moment of unification with God by saying “I abandoned and forgot myself…all things ceased; I went out from myself, leaving my cares forgotten.” Here, the piano writing seems to evaporate while the choral harmonies become especially piercing, even suggesting bitonality for a moment. The effect of returning from this nebulous harmony to C major in the final measures is a powerful musical reflection of the spiritual journey that has taken place.

O Guiding Night is through-composed and multisectional, as Williams sets different parts of the text to music of varying tempi and keys, often with piano interludes to connect. The piece begins with a striking piano introduction that suggests both the ecstatic end point of the soul’s journey and the mysterious process along the way. The choral writing to follow is hushed and rhythmic. In this section and throughout the piece, Williams makes thoughtful use of the choral ambitus: the more intimate parts of the piece feature closer harmony, and those passages that are more rapturous tend to explore wider spacing in chords and more extreme portions of the vocal range of sopranos and basses in particular.

The piece moves from C major to A major, Ab major, and back to C major. The third of these large-scale key areas includes one of the emotional and musical apexes of the work, and this material continues

O Guiding Night lies somewhere in the middle of Williams’ works with regard to level of difficulty. Most of the choral writing in the piece is homophonic, and the harmonic language is rooted in tonality with many colorful added nonchord tones. Williams’ vocal and piano writing is idiomatic, sensitive, and considerate of the needs of singers and players, but it still contains difficult passages, and tuning may be a challenge. The vocal writing is rhythmically vital and fits naturally with the word stresses of the translation, though the homophonic structure tends to expose any issues with ensemble. Finally, the dynamic and emotional ranges of all voice parts suggest a vocal approach that freely uses a variety of vocal timbres and colors.

Roderick Williams’ website (Groves Artists):

https://www.grovesartists.com/artist/roderickwilliams/

Alternate translation of “The Dark Night of the Soul” (Poetry Foundation, translated by David Lewis):

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/ poems/157984/the-dark-night-of-the-soul

— Nathan ReiffEnvironmental Activism through Choral Music: John Luther Adams’s Canticles of the Holy Wind

Kirsten Hedegaard“If we can imagine a culture and a society in which we each feel more deeply responsible for our own place in the world, then we just may be able to bring that culture and that society into being. This will largely be the work of people who will be here on this earth when I am gone. I place my faith in them.”

—John Luther AdamsDuring the past several decades, there has been a growing trend to address social concerns through music. Composers have taken on such topics as racism, LGBTQ and women’s rights, gun violence, as well as other important social issues. One of the subgenres of this socially conscious repertoire is music that focuses on environmentalism and the growing anxiety regarding climate change. Composers are engaging with this topic in a variety of ways, but few North American composers have devoted themselves so thoroughly to this cause as John Luther Adams. Although the majority of his compositions are written for instrumental ensembles, Adams has also made several significant contributions to the choral genre, including Canticles of the Holy Wind (2013), a

tour de force for four SATB choirs. By examining the work of John Luther Adams, most specifically Canticles of the Holy Wind, this paper will provide an important example of how choral music and environmentalism intersect.1

1 Throughout this paper a variety of terminology will be enlisted to identify musical works that intersect with environmentalism, in this case defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as the “concern with the preservation of the natural environment, esp. from damage caused by human influence.” This definition can have a broad interpretation, especially how this “concern” might be addressed in musical terms. In some environmental works, the composer has spelled out a specific relationship to a concept or purpose, but in other cases, the relationship between the music and its exact intention is ambiguous. Nonetheless, to establish some foundational language to classify these works, the term “environmental” will be used somewhat interchangeably with “ecological,” both words intending to describe music that intentionally highlights environmental issues or ecological relationships, either directly or indirectly.

The Field of Ecomusicology

The topic of environmental activism in the arts is a fairly new one, and the subgenre of environmentalism and choral music is an even less researched area. However, the emerging field of ecomusicology, defined as “the study of musical and sonic issues, both textual and performative, as they relate to ecology and the natural environment,” 2 is paving the way for growing research and resources in this area. Although a relatively new term, ecomusicology follows in the lineage of ecocriticism, although as Aaron Allen and other contemporaries might argue, ecomusicology is a more fluid field of study, one that resists a strict set of parameters.

Despite origins in literary and music studies, ecomusicology is more than just artistic inquiry. Ecomusicology is part of the movement to champion a more connected place for humanistic and post-humanistic scholarship, as the environmental humanities are doing. A bigger and more ideal goal is the fusion of disciplines—not just the collaboration or mutual citation, but the amalgamation of scientific, artistic, and humanistic disciplines…3

2 Aaron Allen, “Ecomusicology,” Oxford Music Online (July 25, 2013) https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy2.library.illinois. edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/ omo-9781561592630-e-1002240765?rskey=bULVY5. Note that there is disagreement among scholars about the term ecomusicology as it relates to the field of ethnomusicology. Mark Pedelty’s recent article addresses some of these concerns and makes a case for further development of this emerging genre of scholarship. See Mark Pedelty’s “Moving forward with Ecomusicology,” which is included in a collection of revised essays from the 2018 SEM Conference. Other articles include contributions from Timothy Cooley, Aaron S. Allen, Ruth Hellier, Mark Pedelty, Denise Von Glahn, Jeff Todd Titon, and Jennifer C. Post. “Call and Response: SEM President’s Roundtable 2018, ‘Humanities’ Responses to the Anthropocene’,” Ethnomusicology 64, no. 2 (2020): 301, accessed March 10, 2021, https://doi-org. proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.5406/ethnomusicology.64.2.0301.

3 Aaron Allen, “Introduction” in Current Directions in Ecomusicology, 4.

It is also important to note that western music has had a long romance with nature. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons , Haydn’s The Seasons and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral” are just a few examples of composers looking to depict nature in their music. In the twentieth century, composers like Messiaen continued his exploration of nature through the imitation of birdsong in pieces like Reveil des oiseaux and Le merle noir. Further twentieth-century nature explorations can be found in the use of field recordings and sitespecific pieces, as well as the important work by Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, La Monte Young, and John Cage, all of whom challenged the boundaries of music and listening.

In his 2011 article “Ecomusicology: Ecocritcism and Musicology,” Allen poses the question, “Is the environmental crisis relevant to music- and more importantly, is musicology relevant to solving it?” 4 Whether musicology is a part of the solution is yet to be seen; on the other hand, music performance may be a different question. Can the act of making music be a persuasive tool in effecting social change? A growing body of composers and performers in the choral field are engaging with repertoire that is poised to address this important question.5

4 Aaron Allen, “Ecomusicology: Ecocritcism and Musicology,” Journal of the American Musicological Society (Summer 2011): 392. 5 A cursory examination of America’s folk music history is instructive, as it provides context for the relationship between music and protest. As climate change became a growing reality during the twentieth-century, folk musicians such as Pete Seeger added environmental songs to a growing list of repertoire that addressed social issues, including civil rights, workers’ rights, and the Vietnam war. In the mid-1960s Seeger’s crusade to clean up the Hudson river through concerts and fundraisers set an example of how music might be used as a tool to support environmental activism. See Fred Brandfon’s “The History Boy: Innocence and History in the Life and Music of Pete Seeger,” The American Poetry Review 43, no. 5 (2014): 43–46, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/24593774.

Singing and Activism

While an in-depth study of the sociology of choral singing is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to at least acknowledge the concept of collective singing as an empowering force, specifically related to the performance of “activist” works. The power of music to unify groups of people has been of interest to sociologists since the early nineteenth-century.6 As the field of sociology has developed, the exploration of music’s role in society has remained a persistent area of interest, especially as it pertains to meaning and identity. From Theodor Adorno’s early scholarship on the sociology of music to the more recent research of feminist musicologist Susan McClary, the unrelenting mysteries surrounding music’s power have continued to captivate scholars and thinkers for centuries.

The power of music…resides in its ability to shape the ways we experience our bodies, emotions, subjectivities, desires, and social relations. And to study such effects demands that we recognize the ideological basis of music’s operationsits cultural constructedness. Even the urge to explain on the basis of idealist abstraction or to insist on an unbridgeable gap between music and the outside world stands in need of explanation, an explanation that would require a complex social history stretching back more than twenty-five centuries to Pythagoras.7

This immense history of music’s role in society is best digested in small doses through the study of specific phenomena, for instance, the way music

6 Shepherd and Devine, “Introduction” in Routledge Reader on Sociology of Music, 2–5. This introduction provides a concise history of how sociologists have studied music’s role in society. From August Comte who believed music is “the social of all arts,” to Herbert Spencer, Georg Simmel, and Max Weber, nineteenthcentury sociologists grappled with questions of music’s power, meaning, and significance.

7 Susan McClary, “Music as Social Meaning,” in The Routledge Reader, 82.

can support social resistance by affecting identity and behavior. One way this concept is manifested in singing is through “the way in which music vibrations penetrate the body, permeating it, even as the individual body contributes to the collective sound that envelops it.”8 William Roy describes a similar function in his book Reds, Whites, and Blues.

The social impact of music happens not only through a common understanding of it of the discourse around it but also through the experience of simultaneity. The mutual synchronizing of sonic and bodily experiences creates a bond that is precommunicative and perhaps deeper than shared conscious meaning. This can happen through the interaction of composers and performers, performers and performers, performers and listeners, and listeners and listeners. The more involved a person is in doing music, whether in composing, performing, or listening, the tighter the bond is.9

While music can have a significant impact on an audience, the participatory element is an important consideration. With the recent trend in choral music to program socially conscious repertoire, 10 it should be acknowledged that the impact is as profound (if not more) on the singers, as it is on the audience. This synergy and symbiosis is significant when considering the works of composers such as John Luther Adams, whose peaceful protest is played out with music and the earth as allies, quietly and covertly changing both the performer and listener.

9 Roy, Reds, Whites, and Blues, 16.

10 This growing trend can be observed in concert programming at conferences and in professional journals such as ACDA’s Choral Journal. In addition to recent issues that directly address diversity issues with regard to race and gender, several recent issues have also been devoted to choral music’s role in social advocacy movements. Issues of the Choral Journal can be reviewed here: https://acda.org/category/choral-journal/.

Born in Meridian, Mississippi in 1953, John Luther Adams has devoted his life to the preservation and celebration of the natural world. Adams moved around frequently as a child but spent the majority of his childhood in Georgia. As a teenager, he was exposed to the music of Frank Zappa, Edgard Varèse, John Coltrane, and John Cage, early experiences that opened up new sound worlds for the young and impressionable Adams.11 Eventually, Adams was admitted to the newly established California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts), where he studied composition with James Tenney, whose teaching and music had a lasting effect on Adams.12 After just two years of study, Adams applied for early graduation and in 1973, he was one of the first students to earn their degree from Cal Arts.

Following graduation, Adams moved back to Georgia where he spent many hours outdoors taking walks in the forest and listening to birdsong. It is during this time he began to transcribe the sounds of the birdsong on his daily walks. Through ongoing work with the Audubon Society and Sierra Club, Adams developed a growing interest in conservation work. After a brief stay in Idaho, he eventually found his way to Alaska, where he began work with the Wilderness Society. Within a few years Adams had assumed the role of Executive Director with the Fairbanks Environmental Center.13

While in Fairbanks, Adams worked tirelessly on behalf of the Center, beginning with an expansion of the organization and a name change to Northern Alaska Environmental Center. With a mission dedicated to “preserving complete ecosystems and to creating a sustainable, postpetroleum society in Alaska,” Adams was at the helm of this newly expanded organization. With the support of biologists and geologists, the Environmental Center fought industry and regulations to protect Alaska’s pristine landscape and wildlife from degradation. In addition to battling the Reagan Administration’s plans for drilling, mining, and logging, the Center also fought against destructive state land sales, wildlife endangerment, and most impressively, the Alaska Power authority’s plan to build the world’s two largest dams.

Following a dark and difficult winter in 1989, Adams quit his job at the Center and committed his work to full-time composing. 14 Adams turned his energies to composing, leaving the environmental “day job” behind, but certainly not leaving the environment behind, “with the belief that, ultimately, music can do more than politics to change the world.”15 Over the past four decades he has explored ways to integrate his composition with the natural world, producing concepts such as sonic geography and ecological listening as techniques to reinforce this relationship.16

14 Adams shares the story of seeking advice from his mentor Lou Harrison. After being offered a half-time position at the Center, Adams called Lou for advice. Never one for beating around the bush, Lou answered, “There are no half-time jobs, John Luther. Only half-time salaries,” 91.

11 John Luther Adams, Silences So Deep, 8-12.

12 Adams mentions Tenney’s influence in a number of interviews and writings. In his interview with Gayle Young (“Sonic Geography of the Arctic” http://johnlutheradams.net/sonicgeography-of-the-arctic-interview/) he specifically mentions Tenney’s music in which “a single large sonority, an apparently simple sounding image, slowly reveals an entire world of richness and complexity.” Although he is referring to his Strange and Sacred Noise in this statement, this model of sound is inherent in a number of Adam’s works.

13 Ibid., 18–22.

15 John Luther Adams, “In search of an ecology of music,” website, last accessed November 10, 2020, http:// johnlutheradams.net/.

16 Sabine Feisst, “Music as Place, Places as Music: The Sonic Geography of John Luther Adams” in The Farthest Place, 23–47. “Sonic geography” is a concept that explores “music as place,” a sense that music can evoke and enhance the experiential perception of place through music. Adams has also used the term “ecological listening” in several interviews and articles, in most cases referring to the interface of nature and musical performance in his outdoor works, but also as a more general concept for hearing and communing with nature in his works.

One of his first large-scale projects in the early nineties was Earth and the Great Weather: A Sonic Geography of the Arctic (1993). This large-scale work seems to serve as a transitional work in Adams’s output but also finds relationship to his choral repertoire through its geographic narrative and use of voices. Utilizing percussion, strings, electronics, twelve solo voices, and four speaking voices, Earth and the Great Weather is a dramatic work based on a series of “Arctic Litanies—found poems composed from indigenous names for places, plants, birds, and the seasons.”17 Other pieces from the early nineties include Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing (1991–95) for chamber orchestra, Dream in White on White for strings (1992), and Time of Drumming for orchestra (1995).

These works were followed by Strange and Sacred Noises for percussion quartet (1991–97), Qilyuan for bass drums and electronics (1998), and In the White Silence (1998), a seventy-five-minute work for strings, celeste, harp, and two vibraphones. When Adams set out to compose this last work, he intended it to be “the biggest, most beautiful thing” he’d ever done, as well as a memorial to his mother. Ironically, there is no silence in this piece; however, the churning of the strings and mystical sound of the vibraphone creates an atmosphere of silent, crisp landscape, simultaneously meditative and active.

into a luxurious and mysterious landscape, where time is seemingly inaccessible.18 This marriage of intellectual operations and seductive swaths of sound is a signature of Adams’s music and remains a through-line in his “style.”

His chamber music encompasses a wide range of instrumentation, with a focus on music for percussion ensemble, string quartet, or a combination of percussion and strings together. A number of works from the nineties also include harp: Five Yup’ik Dances (1991–94), Five Athabascan Dances (1992/96), Make Prayers to the Raven (1996/98), and In a Treeless Place, Only Snow (1999).19 Between 2000-2010 Adams explored varied instrumentation, from solo piano works such as Nunataks (2007) to more complex textures in pieces like The Light Within (2007) for alto flute, bass clarinet, vibraphone/crotales, piano, violin, cello, and electronic sounds. Since 2011, many of his chamber pieces have been written for string quartet.

Perhaps his best-known works, Become River (2010), Become Ocean (2013), and Become Desert (2017), form a trilogy of orchestral works that are as diverse as the places they are meant to evoke. Each commissioned by major institutions (St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Seattle Symphony Orchestra, and Seattle/ New York Philharmonic respectively), these three works trace Adams’s trajectory from the West Coast’s “best-kept musical secret” to a composer of international renown.20 The second

Over the past twenty years and with growing recognition, Adams’s works have continued to explore the northern landscapes as well as other geography and ecological phenomena. For Lou Harrison (2003), which Adams considers the third installment in a trilogy that includes Clouds of Forgetting and In the White Silence , is an ode to one of Adams’s mentors. Like its companion pieces, for Lou coaxes the listener

18 See Kyle Gann’s chapter, “Time at the End of the World,” in The Farthest Place. In this essay, he explores this trilogy and uses analytical tools to unpack a few of Adams’ techniques, but also acknowledges that this music is both “rigorous in thought and sensuous in sound- but not on the same scale or in the same way.”

19 These five pieces show a progression from use of solo harp only in Five Yup’ik Dances to a more complex texture in In a Treeless Place, Only Snow for celesta, harp (or piano), 2 vibraphones, and string quartet.

20 Marc Swed, “Critic’s Notebook: Becoming John Luther Adams: The evolution of one of America’s hottest composers,” L.A. Times, May 3, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/ classical/la-ca-cm-john-luther-adams-notebook-20180503-story. html. This profile piece on Adams and these three works offers a basic verbal introduction to this important trilogy.

piece in the trilogy, Become Ocean was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in music and the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Among other awards he was also named Musical America’s 2015 “Composer of the Year.”

ecology, as well as an intimate journal outlining the creation of his most intricate work to date, a musical installation that registers the sounds of the earth through a complex system of math and music. Named after the installation itself, this text provides insight into the philosophical and technical process of creating a musical composition that derives its material from the earth, yet remains man-envisioned and man-made.

John Luther Adams’s writings encompass three published books, numerous articles, and interviews, as well as an occasional poem. Writing has been an important part of his creative process, with the intention “to articulate for myself my own evolving understanding of my work.”21 He is also interested in providing his listeners with an opportunity to discover “the broader context from which the music grows.”22

In his first published book, Winter Music: Composing the North, Adams shares a collection of music essays as well as journal entries and anecdotes about other aspects of his life. The net result is an inspiring portrait of how Adams synthesizes his work as a composer with his existence as a deeply caring human, someone interested in preserving the beauty and magnificence of the natural world. Each entry in this collection offers a glimpse at the experiences and ruminations that inspire Adams to write his music. In the second chapter “Resonance of Space” he writes at length about the relationship of people to place, a concept that remains central to his compositional priorities.