41 minute read

The Field of Ecomusicology

The topic of environmental activism in the arts is a fairly new one, and the subgenre of environmentalism and choral music is an even less researched area. However, the emerging field of ecomusicology, defined as “the study of musical and sonic issues, both textual and performative, as they relate to ecology and the natural environment,” 2 is paving the way for growing research and resources in this area. Although a relatively new term, ecomusicology follows in the lineage of ecocriticism, although as Aaron Allen and other contemporaries might argue, ecomusicology is a more fluid field of study, one that resists a strict set of parameters.

Despite origins in literary and music studies, ecomusicology is more than just artistic inquiry. Ecomusicology is part of the movement to champion a more connected place for humanistic and post-humanistic scholarship, as the environmental humanities are doing. A bigger and more ideal goal is the fusion of disciplines—not just the collaboration or mutual citation, but the amalgamation of scientific, artistic, and humanistic disciplines…3

Advertisement

2 Aaron Allen, “Ecomusicology,” Oxford Music Online (July 25, 2013) https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy2.library.illinois. edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/ omo-9781561592630-e-1002240765?rskey=bULVY5. Note that there is disagreement among scholars about the term ecomusicology as it relates to the field of ethnomusicology. Mark Pedelty’s recent article addresses some of these concerns and makes a case for further development of this emerging genre of scholarship. See Mark Pedelty’s “Moving forward with Ecomusicology,” which is included in a collection of revised essays from the 2018 SEM Conference. Other articles include contributions from Timothy Cooley, Aaron S. Allen, Ruth Hellier, Mark Pedelty, Denise Von Glahn, Jeff Todd Titon, and Jennifer C. Post. “Call and Response: SEM President’s Roundtable 2018, ‘Humanities’ Responses to the Anthropocene’,” Ethnomusicology 64, no. 2 (2020): 301, accessed March 10, 2021, https://doi-org. proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.5406/ethnomusicology.64.2.0301.

3 Aaron Allen, “Introduction” in Current Directions in Ecomusicology, 4.

It is also important to note that western music has had a long romance with nature. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons , Haydn’s The Seasons and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral” are just a few examples of composers looking to depict nature in their music. In the twentieth century, composers like Messiaen continued his exploration of nature through the imitation of birdsong in pieces like Reveil des oiseaux and Le merle noir. Further twentieth-century nature explorations can be found in the use of field recordings and sitespecific pieces, as well as the important work by Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, La Monte Young, and John Cage, all of whom challenged the boundaries of music and listening.

In his 2011 article “Ecomusicology: Ecocritcism and Musicology,” Allen poses the question, “Is the environmental crisis relevant to music- and more importantly, is musicology relevant to solving it?” 4 Whether musicology is a part of the solution is yet to be seen; on the other hand, music performance may be a different question. Can the act of making music be a persuasive tool in effecting social change? A growing body of composers and performers in the choral field are engaging with repertoire that is poised to address this important question.5

4 Aaron Allen, “Ecomusicology: Ecocritcism and Musicology,” Journal of the American Musicological Society (Summer 2011): 392. 5 A cursory examination of America’s folk music history is instructive, as it provides context for the relationship between music and protest. As climate change became a growing reality during the twentieth-century, folk musicians such as Pete Seeger added environmental songs to a growing list of repertoire that addressed social issues, including civil rights, workers’ rights, and the Vietnam war. In the mid-1960s Seeger’s crusade to clean up the Hudson river through concerts and fundraisers set an example of how music might be used as a tool to support environmental activism. See Fred Brandfon’s “The History Boy: Innocence and History in the Life and Music of Pete Seeger,” The American Poetry Review 43, no. 5 (2014): 43–46, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/24593774.

Singing and Activism

While an in-depth study of the sociology of choral singing is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to at least acknowledge the concept of collective singing as an empowering force, specifically related to the performance of “activist” works. The power of music to unify groups of people has been of interest to sociologists since the early nineteenth-century.6 As the field of sociology has developed, the exploration of music’s role in society has remained a persistent area of interest, especially as it pertains to meaning and identity. From Theodor Adorno’s early scholarship on the sociology of music to the more recent research of feminist musicologist Susan McClary, the unrelenting mysteries surrounding music’s power have continued to captivate scholars and thinkers for centuries.

The power of music…resides in its ability to shape the ways we experience our bodies, emotions, subjectivities, desires, and social relations. And to study such effects demands that we recognize the ideological basis of music’s operationsits cultural constructedness. Even the urge to explain on the basis of idealist abstraction or to insist on an unbridgeable gap between music and the outside world stands in need of explanation, an explanation that would require a complex social history stretching back more than twenty-five centuries to Pythagoras.7

This immense history of music’s role in society is best digested in small doses through the study of specific phenomena, for instance, the way music can support social resistance by affecting identity and behavior. One way this concept is manifested in singing is through “the way in which music vibrations penetrate the body, permeating it, even as the individual body contributes to the collective sound that envelops it.”8 William Roy describes a similar function in his book Reds, Whites, and Blues.

6 Shepherd and Devine, “Introduction” in Routledge Reader on Sociology of Music, 2–5. This introduction provides a concise history of how sociologists have studied music’s role in society. From August Comte who believed music is “the social of all arts,” to Herbert Spencer, Georg Simmel, and Max Weber, nineteenthcentury sociologists grappled with questions of music’s power, meaning, and significance.

7 Susan McClary, “Music as Social Meaning,” in The Routledge Reader, 82.

The social impact of music happens not only through a common understanding of it of the discourse around it but also through the experience of simultaneity. The mutual synchronizing of sonic and bodily experiences creates a bond that is precommunicative and perhaps deeper than shared conscious meaning. This can happen through the interaction of composers and performers, performers and performers, performers and listeners, and listeners and listeners. The more involved a person is in doing music, whether in composing, performing, or listening, the tighter the bond is.9

While music can have a significant impact on an audience, the participatory element is an important consideration. With the recent trend in choral music to program socially conscious repertoire, 10 it should be acknowledged that the impact is as profound (if not more) on the singers, as it is on the audience. This synergy and symbiosis is significant when considering the works of composers such as John Luther Adams, whose peaceful protest is played out with music and the earth as allies, quietly and covertly changing both the performer and listener.

9 Roy, Reds, Whites, and Blues, 16.

10 This growing trend can be observed in concert programming at conferences and in professional journals such as ACDA’s Choral Journal. In addition to recent issues that directly address diversity issues with regard to race and gender, several recent issues have also been devoted to choral music’s role in social advocacy movements. Issues of the Choral Journal can be reviewed here: https://acda.org/category/choral-journal/.

John Luther Adams: Background

Born in Meridian, Mississippi in 1953, John Luther Adams has devoted his life to the preservation and celebration of the natural world. Adams moved around frequently as a child but spent the majority of his childhood in Georgia. As a teenager, he was exposed to the music of Frank Zappa, Edgard Varèse, John Coltrane, and John Cage, early experiences that opened up new sound worlds for the young and impressionable Adams.11 Eventually, Adams was admitted to the newly established California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts), where he studied composition with James Tenney, whose teaching and music had a lasting effect on Adams.12 After just two years of study, Adams applied for early graduation and in 1973, he was one of the first students to earn their degree from Cal Arts.

Following graduation, Adams moved back to Georgia where he spent many hours outdoors taking walks in the forest and listening to birdsong. It is during this time he began to transcribe the sounds of the birdsong on his daily walks. Through ongoing work with the Audubon Society and Sierra Club, Adams developed a growing interest in conservation work. After a brief stay in Idaho, he eventually found his way to Alaska, where he began work with the Wilderness Society. Within a few years Adams had assumed the role of Executive Director with the Fairbanks Environmental Center.13

While in Fairbanks, Adams worked tirelessly on behalf of the Center, beginning with an expansion of the organization and a name change to Northern Alaska Environmental Center. With a mission dedicated to “preserving complete ecosystems and to creating a sustainable, postpetroleum society in Alaska,” Adams was at the helm of this newly expanded organization. With the support of biologists and geologists, the Environmental Center fought industry and regulations to protect Alaska’s pristine landscape and wildlife from degradation. In addition to battling the Reagan Administration’s plans for drilling, mining, and logging, the Center also fought against destructive state land sales, wildlife endangerment, and most impressively, the Alaska Power authority’s plan to build the world’s two largest dams.

Following a dark and difficult winter in 1989, Adams quit his job at the Center and committed his work to full-time composing. 14 Adams turned his energies to composing, leaving the environmental “day job” behind, but certainly not leaving the environment behind, “with the belief that, ultimately, music can do more than politics to change the world.”15 Over the past four decades he has explored ways to integrate his composition with the natural world, producing concepts such as sonic geography and ecological listening as techniques to reinforce this relationship.16 into a luxurious and mysterious landscape, where time is seemingly inaccessible.18 This marriage of intellectual operations and seductive swaths of sound is a signature of Adams’s music and remains a through-line in his “style.”

14 Adams shares the story of seeking advice from his mentor Lou Harrison. After being offered a half-time position at the Center, Adams called Lou for advice. Never one for beating around the bush, Lou answered, “There are no half-time jobs, John Luther. Only half-time salaries,” 91.

11 John Luther Adams, Silences So Deep, 8-12.

12 Adams mentions Tenney’s influence in a number of interviews and writings. In his interview with Gayle Young (“Sonic Geography of the Arctic” http://johnlutheradams.net/sonicgeography-of-the-arctic-interview/) he specifically mentions Tenney’s music in which “a single large sonority, an apparently simple sounding image, slowly reveals an entire world of richness and complexity.” Although he is referring to his Strange and Sacred Noise in this statement, this model of sound is inherent in a number of Adam’s works.

13 Ibid., 18–22.

15 John Luther Adams, “In search of an ecology of music,” website, last accessed November 10, 2020, http:// johnlutheradams.net/.

16 Sabine Feisst, “Music as Place, Places as Music: The Sonic Geography of John Luther Adams” in The Farthest Place, 23–47. “Sonic geography” is a concept that explores “music as place,” a sense that music can evoke and enhance the experiential perception of place through music. Adams has also used the term “ecological listening” in several interviews and articles, in most cases referring to the interface of nature and musical performance in his outdoor works, but also as a more general concept for hearing and communing with nature in his works.

One of his first large-scale projects in the early nineties was Earth and the Great Weather: A Sonic Geography of the Arctic (1993). This large-scale work seems to serve as a transitional work in Adams’s output but also finds relationship to his choral repertoire through its geographic narrative and use of voices. Utilizing percussion, strings, electronics, twelve solo voices, and four speaking voices, Earth and the Great Weather is a dramatic work based on a series of “Arctic Litanies—found poems composed from indigenous names for places, plants, birds, and the seasons.”17 Other pieces from the early nineties include Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing (1991–95) for chamber orchestra, Dream in White on White for strings (1992), and Time of Drumming for orchestra (1995).

These works were followed by Strange and Sacred Noises for percussion quartet (1991–97), Qilyuan for bass drums and electronics (1998), and In the White Silence (1998), a seventy-five-minute work for strings, celeste, harp, and two vibraphones. When Adams set out to compose this last work, he intended it to be “the biggest, most beautiful thing” he’d ever done, as well as a memorial to his mother. Ironically, there is no silence in this piece; however, the churning of the strings and mystical sound of the vibraphone creates an atmosphere of silent, crisp landscape, simultaneously meditative and active.

His chamber music encompasses a wide range of instrumentation, with a focus on music for percussion ensemble, string quartet, or a combination of percussion and strings together. A number of works from the nineties also include harp: Five Yup’ik Dances (1991–94), Five Athabascan Dances (1992/96), Make Prayers to the Raven (1996/98), and In a Treeless Place, Only Snow (1999).19 Between 2000-2010 Adams explored varied instrumentation, from solo piano works such as Nunataks (2007) to more complex textures in pieces like The Light Within (2007) for alto flute, bass clarinet, vibraphone/crotales, piano, violin, cello, and electronic sounds. Since 2011, many of his chamber pieces have been written for string quartet.

Perhaps his best-known works, Become River (2010), Become Ocean (2013), and Become Desert (2017), form a trilogy of orchestral works that are as diverse as the places they are meant to evoke. Each commissioned by major institutions (St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Seattle Symphony Orchestra, and Seattle/ New York Philharmonic respectively), these three works trace Adams’s trajectory from the West Coast’s “best-kept musical secret” to a composer of international renown.20 The second

Over the past twenty years and with growing recognition, Adams’s works have continued to explore the northern landscapes as well as other geography and ecological phenomena. For Lou Harrison (2003), which Adams considers the third installment in a trilogy that includes Clouds of Forgetting and In the White Silence , is an ode to one of Adams’s mentors. Like its companion pieces, for Lou coaxes the listener

18 See Kyle Gann’s chapter, “Time at the End of the World,” in The Farthest Place. In this essay, he explores this trilogy and uses analytical tools to unpack a few of Adams’ techniques, but also acknowledges that this music is both “rigorous in thought and sensuous in sound- but not on the same scale or in the same way.” piece in the trilogy, Become Ocean was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in music and the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Among other awards he was also named Musical America’s 2015 “Composer of the Year.” ecology, as well as an intimate journal outlining the creation of his most intricate work to date, a musical installation that registers the sounds of the earth through a complex system of math and music. Named after the installation itself, this text provides insight into the philosophical and technical process of creating a musical composition that derives its material from the earth, yet remains man-envisioned and man-made.

19 These five pieces show a progression from use of solo harp only in Five Yup’ik Dances to a more complex texture in In a Treeless Place, Only Snow for celesta, harp (or piano), 2 vibraphones, and string quartet.

20 Marc Swed, “Critic’s Notebook: Becoming John Luther Adams: The evolution of one of America’s hottest composers,” L.A. Times, May 3, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/ classical/la-ca-cm-john-luther-adams-notebook-20180503-story. html. This profile piece on Adams and these three works offers a basic verbal introduction to this important trilogy.

John Luther Adams’s writings encompass three published books, numerous articles, and interviews, as well as an occasional poem. Writing has been an important part of his creative process, with the intention “to articulate for myself my own evolving understanding of my work.”21 He is also interested in providing his listeners with an opportunity to discover “the broader context from which the music grows.”22

In his first published book, Winter Music: Composing the North, Adams shares a collection of music essays as well as journal entries and anecdotes about other aspects of his life. The net result is an inspiring portrait of how Adams synthesizes his work as a composer with his existence as a deeply caring human, someone interested in preserving the beauty and magnificence of the natural world. Each entry in this collection offers a glimpse at the experiences and ruminations that inspire Adams to write his music. In the second chapter “Resonance of Space” he writes at length about the relationship of people to place, a concept that remains central to his compositional priorities.

Adams’s second book The Place Where You Go to Listen: In Search of an Ecology of Music , is both an exploration of the concept of musical xxi. 22 Ibid., xxi.

The Place resonates with nature. But this nature is filtered through my ears. For the listener I hope this music sounds and feels natural, as though it comes directly from the earth and the sky. Yet the decisions about timbres, tunings, harmonies, and melodic curves, the dynamics, rhythms, counterpoint, and musical textures were mine. Despite my desire to remove myself and invite the listener to occupy the central position, The Place is still a musical composition. Although I tried to minimize the evidence of my hand, I remain the composer.23

Although the above quote refers specifically to The Place, it might just as well apply to Adams’s approach to composition in general: to empower the listener to encounter nature through the sensuous experience of sound.

Adams’s most recent book, Silences So Deep was released in 2020 and serves as an autobiographical account of his several decades in Alaska. Through his authentic and gentle style, Adams manages to share basic details about his life as a musician and environmental activist in Alaska, while simultaneously evoking a sense of poetry and nature throughout the book. Because Adams’s life is so integrated with his composing, every page seems to offer new insight into his music. In an especially helpful appendix titled “Sources,” he catalogs his major inspirations and influences, including books, composers, musical genres, and even specific birds.24

John Luther Adams: Choral Repertoire

Ultimately, the background of Adams has led him down a path that integrates a love and concern for the environment with the desire to communicate ideas through music. The choral works of Adams illustrate this concept through imaginative soundscapes that cover vast terrain. Adams has only written a few works for chorus, but each is imbued with a singularity that is enhanced by the rarity of choral works in his output. Adams’s approach to his composition is deeply affected by his commitment to the well-being of the earth.

As an artist, I see myself as a worker for a culture I will never live to inhabit, in a society that may never come to be. And I know that I’m not alone. All over the world, there are artists and scientists, teachers and activists, people in every field of labor who, in their own ways, are working with the belief that the only possible future for our human species is to discover a new way of being on this earth. Together and alone, we are doing our best to imagine and to create new cultures and new societies to come after the inevitable collapse of the global monoculture that

24 These lists are a valuable resource for understanding Adams’s music.

Writers: Henry David Thoreau, John Haines, Barry Lopez, Annie Dillard, Edward Abbey, Paul Shepard, Richard Nelson, Henry Cowell, John Cage, Lou Harrison

Birds: wood thrush, hermit thrush, canyon wren

World Music: Japan, Java, Bali, Tibet, Africa, and indigenous music of Alaska

European Composers: Ockeghem, Monteverdi, Bach, Debussy, Sibelius, Xenakis, Radigue

American Composers: Ives, Varèse, Cowell, Crawford-Seeger, Rudhyar, Partch, Cage, Harrison, Nancarrow, Feldman, Oliveros, Tenney, and other contemporaries is driving us toward oblivion. We are working as if our survival depended on it, because, very likely, it does.

Music is my way of understanding the world, of knowing where I am and how I fit in. This isn’t just an emotional, a psychological need. It’s a spiritual hunger —a search for the sacred.25

Adams’s choral works are less known, in part because there are only a few of them, but also due to their technical demands. Night Peace (1976) and Forest without Leaves (1984), both written for chorus and instruments are his two early choral works and are the most accessible of his output. After a twenty-five-year gap, Canticles of the Sky was composers for the Latvian choir Kamer, eventually being incorporated into Canticles of the Holy Wind five years later. Composed for four advanced SATB choirs, these two works are much different in scope compared to Night Peace and Forest. In the Name of the Earth finds its challenge by the sheer scope of the piece, which requires a massed choir of many singers to be assembled in an outside venue. Adams has also recently completed a new work for small vocal ensemble, A Brief Descent into Deep Time, a twenty-minute work which traces the two-billion-year geological transformation of the Grand Canyon.26 Given that the performing forces of A Brief Descent are in contrast to the massed choir of In the Name as well as the 32-voice chamber choir required of Canticles , this latest work will certainly yield yet another expression of Adams’s sensitive and specific response to his diverse mediums. (See table 1 for chronological listing of these works.)

25 John Luther Adams, “In the Name of the Earth,” website, last accessed February 10, 2021 http://johnlutheradams.net/in-thename/.

26 This information was disclosed via an e-mail update from John Luther Adams and confirmed by e-mail correspondence with Paul Hillier, who premiered the work in February of 2022. Further communication between the composer and author revealed that A Brief Descent into Deep Time is the basis for a new, large-scale work, Vespers of the Blessed Earth, which will be premiered by The Crossing and The Philadelphia Orchestra in Spring, 2023.

Table 1: Environmental choral works of John Luther Adams

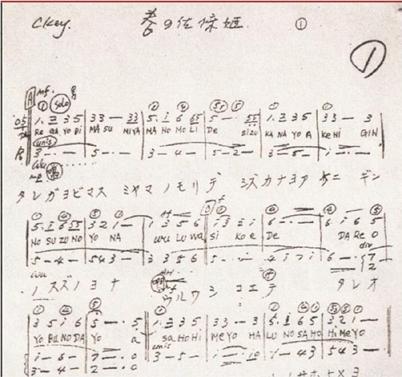

Composed just a few years after his graduation from Cal Arts, Night Peace was commissioned by the Atlanta Singers, with Joanne Falletta conducting the premiere. On the title page Adams shares insight on his motivic material: “Night Peace is based entirely on a single melodic line, which is heard only once. This melody was conceived in the luminous stillness of a moonless winter night.” This brief motive (F-sharp–A–B–A) is varied throughout the piece and can be found in melodic fragments and harmonic sonorities (see fig. 1). The score calls for percussion (timpani, marimba, vibraphone, cymbals, tam-tam, glass chimes, and sea urchin wind chimes) and harp, as well as two antiphonal choirs. There is no text for the chorus, but Adams instructs the singers to phonate without vibrato on a “round, open ‘ah’ as in father.” He also specifies that each choir should have 12–24 singers.

Forest without Leaves , which is currently in revision 27 has deep personal meaning for Adams. Written in response to a new cycle of poems by John Haines, a long-time close friend, colleague, and environmental poet, this work was a landmark in Adams’s future trajectory.

Working closely with John Haines encouraged me to think more deeply about what it meant to be an artist in the Far North, giving me the temerity to entertain artistic aspirations to match the landscapes of Alaska.28

A cantata for choir, vocal soloists, and chamber orchestra, Forest without Leaves is quite different from Night Peace. For one, it has a text, or more precisely, sixteen texts.29 It is clear that Adams developed a deep respect for setting poetry during this process, as he strove to be true to natural word accent and rhetoric.

Any composer who sets out to add tones to a text of integrity faces a formidable challenge. As language, the words are complete in and of themselves. Yet when they are spoken, they cry out for the added resonance of singing voices and instruments. The composer’s challenge, then, is to enhance that inherent music without impairing the imagery or meanings of the words. This demands a serious obligation of fidelity to words not only as sound, but as language.30

27 John Luther Adams, conversation.

28 Adams, Silences, 68.

29 The sixteen cantata movements: In the forest without leaves, What sounds can be heard in a forest without leaves, This earth written over with words, One rock on another-that makes a wall, Earth, black speech, And sometimes through the air a cone of dust, (Interlude I), Say after me, Those who write sorrow on the earth, Building with matches, This earth is written over with words, Life was not a clock, (Interlude II), How the sun came to the forest, In all the forest-chilled by its spent wealth, What will be said of you- tree of life, A coolness will come to their children, and In the forest without leaves.

30 Adams, Silences, 64.

The texts of Forest without Leaves are “unabashedly ecocentric” and culminate in a post-apocalyptic nuclear winter scene in the penultimate movement, “A coolness will come to their children.” However, the content of the final poem ends on a hopeful note: “Let earth be this windfall swept to a handful of seeds—one tree, one leaf, gives us plenty of light.”

A mixture of both tonal and atonal material, the music traverses a wide range of textures and harmonic content. His other choral works tend to use vowels or single word litanies rather than entire texts, which also sets this piece apart from the rest. Forest without Leaves is unlike any of Adams’s other choral writing and therefore holds a unique place in his output.

Premiered in 2018 at the Lincoln Center’s Out of Doors Festival, In the Name of the Earth is a deeply spiritual work designed to “draw music not only from my own imagination but also from the older, deeper music of this continent.”31 A much different piece than Forest without Leaves, In the Name calls for four choirs and a variety of sound instruments, including rubbed stones, rattles, and small bells. In his preface to the score Adams eloquently explains the concept for the piece:

The texts of the work are litanies of names—the names of mountain peaks and ranges, rivers and glaciers, forests and plains and deserts—in English and Spanish, and older indigenous names that resonate like words spoken by the earth itself.

By singing some of the beautifully resonant names that we give to mountains, deserts, rivers and oceans, I hope to draw music not only from my own imagination but also more directly from the earth itself. The title of this work is a conscious reference to Christian liturgy. But in place of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, I want to invoke the roots of my own faith—in the Earth, the Waters, and the Holy Wind.

This idea of “sonic geography” is central to Adams’s work over the last thirty years and is a pervasive philosophy that, rather than composing music only about place, it is possible to compose with a sense of music as place.32

In the Name of the Earth utilizes four SATB choruses in eight-part divisi, each representing a different compass point landscape in North America: North, South, East, West. Each of the choruses is also called upon to play the small percussion instruments and create the spoken sound effects, but according to Simon Halsey who premiered the work and Adams himself, these unsung parts can also be performed by amateurs, children, or non-musicians.33 All participants also join in singing the large canon that appears in the final section of the work (see fig. 2). The two main performances of this work to date, New York and London, have each included approximately 600 singers, and although the piece is intended to be performed outside, both of these performances took place indoors due to restrictions.

John Luther Adams: Canticles of the Holy Wind

Background

Completed in 2017, Canticles of the Holy Wind consists of fourteen movements and ruminates on three interrelated subjects: wind, sky, and birds.

I. Sky with Four Suns

II. The White Wind

III. Dream of the Hermit Thrush

IV. Sky with Four Moons

V. The Singing Tree

VI. The Blue Wind

VII. The Hour of the Doves

VIII. Sky with Nameless Colors

IX. Cadenza of the Mockingbird

X. The Yellow Wind

XI. Dream of the Canyon Wren

XII. Sky with Endless Stars

XIII. The Hour of the Owls

XIV. The Dark Wind

The liner notes to the 2017 recording do not contain program notes per se, but Adams does provide an illuminating statement on the piece, a sentiment that may very well summarize his overall work as a composer.

32 Gayle Young, “Sonic Geography of the Arctic,” interview on composer’s website. http://johnlutheradams.net/sonic-geographyof-the-arctic-interview/ Young’s interview with Adams provides a brief snapshot at the evolution of his music over the past forty years. This idea is also related to the earlier discussion of how we define nature. In Adam’s concept of “sonic geography,” the music and so-called “nature” are not separate entities, but one and the same, very much in the vein of the Sami joiking, previously referenced in Tina Ramnarine’s article on this practice.

33 Simon Halsey, “In the Name of the Earth,” YouTube, accessed February 8, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=VTu_1Hi4drU and John Luther Adams interview.

Throughout my life, I’ve clung to hope for the future of our species. But amid the gathering darkness of our own making—global warming, terrorism and seemingly unending wars, widespread social and economic injustice, rampant greed and environmental destruction, resurgent racism and rising fascism— it’s increasingly difficult to maintain unmitigated faith in humanity. And I find myself reimagining hope.

I don’t look for answers in political ideology, humanistic philosophy, or religious dogma. Instead I place my faith in the land and the skies, the wind and the birds—in what we call “nature”. And I take comfort in a larger vision of the earth and the universe, and my own small place in this beautifully fleeting moment within the endlessly turbulent and sublime music of creation.34

Four of these movements had previously been composed as Canticles of the Sky and were completed in 2008, along with versions for string quartet and cello choir.35 The extended work was commissioned by the professional choir, The Crossing and the Latvian choir, Kamer, resulting in a technical tour de force, requiring four distinct SATB choirs for eight of the movements, as well as vocal soloists. At its New York premiere at the Met in 2016, critic Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim describes her sonic experience:

[A] hypnotic and ethereally beautiful invocation of wind, sky and birdsong… Adams’s “Canticles” seems to achieve a new symbiosis, folding natural sounds into mathematically ordered patterns. The resulting music combines the pristine freshness of nature with the sheltering symmetries of Gothic architecture.36

This is music that requires patience, stillness, and above all deep listening. The division of movements into sky, wind, and birds creates a varied and vivid tapestry that also carries the listener through distinct spaces and habitats, as it “hovers, soars, echoes, and chirps.”37

Structural Overview

Exploring an Adams score can be likened to a biologist unraveling the mysteries of a beautiful organism in nature: the dissection reveals new data, but it does not fully explain the totality of its existence. Alex Ross eloquently describes this phenomenon in his introduction to The Place Where You Go to Listen.

The music of Adams is simply and logically constructed, but operates on such a vast scale that we don’t experience it as simple or logical. At a given moment an Adams piece presents us with an image of eternity: an unchanging sonority, or a complex of repeating out-of-tempo ostinatos. Changes of texture and sonority come, but we cannot hear them coming nor predict their arrival. The pattern of changes makes logical sense to one who analyzes the score, and thus views the music, as it were, from a bird’seye view; but the listener, close to the music’s surface—like a hiker working her way across Adams’s beloved Alaskan landscape—must submit to the vastness, the unknowability, the richness of the textures and patterns, the accidental coincidences of large-scale process. Still, there are clues embedded in the music that mark the trajectory of that process, and the well-informed listener is like a hiker with a road map in his head, and who occasionally glimpses a landmark.38

34 John Luther Adams, Canticles of the Holy Wind liner notes, 2017.

35 Adams, interview by author, November 5, 2020.

36 Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim, review of Canticles of the Holy Wind in concert at the Met, New York Times, October 30, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/01/arts/music/reviewcanticles-of-the-holy-wind-summons-the-elements-at-the-met. html.

37 Donald Nally, program notes from Canticles of the Holy Wind, privately shared.

The four sky movements, which were composed first and finished as a complete set, share a textural uniformity that creates a backdrop for the rest of the larger work. After all, wind and birds inhabit the sky, so it is fitting that the omnipresent expanse of the sky serves as the structural setting of the piece. Canticles of the Sky has also been arranged for other instrumental configurations, including string quartet and cello ensemble, and given that these movements are sung on an “ah” vowel throughout, the translation to instruments is fitting. These four movements also generate distinct times of day: “Sky with Four Suns,” “Sky with Four Moons,” “Sky with Nameless Color,” and “Sky with Endless Stars.” The trajectory from day to night is suggested not just by the titles but also in the gently shifting colors that take place over the course of the four movements. The soaring expanse captured by each of these four movements is awe-inspiring and at times even overwhelming, not unlike the feelings that might very well overtake one during a mindful encounter in nature. and employing calculations to create giant structures in which perfection and inevitability are inseparable. 39

The math is clearly outlined in the first movement, “Sky with Four Suns,” whose structure is based on the interval of a fifth and the relationship between I and V. The symmetry of this movement is also an important structural feature, a shape that creates a natural slope over the course of the piece. The four SATB choruses share the same melodic material in a quasi-canonic structure, but the length of notes is varied between the parts, giving the texture an organic irregularity (see fig. 3). The note lengths which vary from fifteen beats to six beats and remain uniform for the voice parts within each chorus. The values are assigned as such: Chorus One, fifteen beats; Chorus Two, twelve beats; Chorus Three, nine beats; Chorus Four, six beats.

The spacious texture that Adams uses is a thoughtful balance between math and spiritual intuition, technique and inspiration working in tandem to reveal an immense force at work. On the page, these four movements look very similar: long, tied whole and half notes, spacious voicing, and deliberate attention to dynamic shape. These salient musical features interface with a distinct transcendence, a synergistic relationship that evokes great beauty. Donald Nally writes eloquently about this relationship in his program notes:

Part of that beauty comes from John’s creative process, which involves a lot of math. Of course, we know that all of nature can be described mathematically; it’s largely figuring out these infinitely complex systems that is what we call science… In Canticles, John has found a way to do that, to express the great beauty of the outdoors indoors, by employing some pretty spectacular arithmetic. You don’t hear the math, but it’s there, rooted in canonic techniques that remind us of early Renaissance music, like Josquin,

The relationship between V and I can be easily observed by looking at the bass 2 part in choir one, which is imitated in the other three choirs as well: D to G, C to F, B-flat to E-flat to B-flat (center point climax), F to C, G to D. Building upwards from these structural bass notes, the other voices fill out a series of four-note sonorities: D–A–E–B, G–D–A–E / C–G–D–A, F–C–G–D / B-flat–F–C–G /E-flat–Bflat–F–C, followed by the inverted tetrachords after the peak. The spaciousness of the open fifths with the overlapping sonorities, combined with the vocal climb from the opening low D in the bass to the high C6 in the soprano parts at the climax, arouses a euphoric sense of a sky filled with the most amazing sunlight. Short of viewing such a sight, this experience allows the listener to bathe in the sound of four suns in the sky.40

39 Nally, program notes.

The other three sky movements bear a strong resemblance to “Sky with Four Suns” and the compositional approach utilizes similar methods. However, the net effect is one of a very different sky- still sky, but altered by the passing hours. Where “Sky with Four Suns” begins with a rumbling low D in the basses, “Sky with Four Moons” begins on a high B5 in the soprano in Chorus Four, followed by descending fourths in the other vocal parts. The quality of the fourths are mostly perfect throughout the movement, with the exception of the G-natural in the Alto 2 part in Chorus One and Two (see fig. 4). This tri-tone relationship the C-sharp sticks out of the texture and adds a degree of mystery to the texture, perhaps a night sky more dimly lit than the “Fours Suns” sky, radiant and open with the perfect fifth sonority. Eventually, the fourths give way to fifths, leading to a muted middle section with the voices singing in their lower registers. This movement also follows a similar symmetrical pattern in that the voices retreat from the midpoint by singing through the patterns in reverse order.

While similar in style to the other sky movements, “Sky with Nameless Color” follows a slightly more complicated structure than the first and fourth movements. The first notable difference is the use of triads as opposed to open intervals. The resonance of these major chords adds additional color to the texture, although the long note values ensure that the expanse of the skyline is not lost. This movement also differs in the ways the four choirs interact. While Choirs One and Two both spin out a longer circle-offifths sequence (B-flat major, F major, C major, G major, D major, A major, E major), Chorus Three and Four only employ a G major, D major, A major, E major sequence. This movement is also striking for its luminous suspensions that occur at the peak of the movement, culminating in an E major chord in the upper voices (see fig. 5). Although this chord is never fully sounded without an extra non-chord tone lingering, the power of the arrival is impactful.

The final sky movement, “Sky with Endless Stars,” finds its unique color by use of minor triadic sonorities. This movement also begins with a high soprano note, this time on an A-flat5, the third of an f-minor chord. The harmonic progression follows the same pattern as “Sky with Nameless Color” with a circle-of-fifths pattern for the most part, (f minor–b minor–d-sharp minor–gsharp minor–c-sharp minor–f-sharp minor–b minor) with two of the choirs being relegated to a repeating pattern of g-sharp minor–c-sharp minor–f-sharp minor–b minor. The arrival at b minor is heralded by low fortissimo singing in the ATB voices, a striking moment that has a sense of inevitability (see fig. 6).

The four wind movements are titled according to colors: “The White Wind,” “The Blue Wind,” “The Yellow Wind,” and “The Dark Wind.” Constructed with a unified approach to form, these movements continue to use imitation as an important structural element, although the texture is much more varied between the SATB voices via rhythmic distinctions. Whereas the four sky movements rely on the stillness generated by long notes and slowly unfolding melodic and harmonic shape, the four wind movements are unified by the use complex rhythmic motives that suggest the fickle fluctuation of the wind. The harmonic progressions still follow a symmetrical circle-of-fifths format with D as the tonal center, with slight variations between the movements. Given the more complex rhythms found in these movements a chart of the similarities and differences will best clarify the character of each of these movements (see table 2).

The flow created by these rhythmic motives, combined with the triadic structures and tonal inflections, generates a series of four corresponding windscapes. At the same time, each of the four winds takes on a nuanced character, supported by the assigned voicing, harmonic color, range, and dynamics. These movements are especially striking in contrast to the stillness of the sky movements, one set enlivened by gusts of rhythmic energy, and the other content in placid stillness. Once all of the voices have entered the perpetual motion of the rhythmic figures couples with a gradual rise in tessitura in all voices, creating an overall arch shape to the movement (see fig. 7).

If the sky and the wind are the two leads in this landscape story, then the bird movements serve as supporting roles, adding interest, character, and depth to the larger narrative. In the preface to the work, Adams shares a personal note on his relationship to birdsong.

My life’s work began with birds. Almost forty years later, I’ve returned to bird songs as a source for my music. In the past I’ve utilized piccolos, percussion and other instruments to evoke the music of birds. Now I find myself translating the songs of birds into music for human voices, singing these strange languages that we do not speak and may never understand.

By and large, the six bird movements are written for solo voices, with the exception of “The Hour of the Owls,” which calls for all tenors and basses to sing. Also notable is that these movements ask for the singers to play percussion instruments while moving about the performance space.41

The first of the bird movements, “Dream of the Hermit Thrush” calls for a solo SSAATTBB octet and orchestra bells. The timbre of the bells with the calling back and forth between the voices sets up a playful mood, while the overlapping sustained sounds suggest a dreamy setting. The melodic figures and resulting harmony is diatonic, with a structural emphasis of a minor, G Major, and C Major. The rhythmic stratification between the voices and bells is defined by the triplet melodic figures in augmentation and diminution, with the fastest rhythm found in the bells (see fig. 8).

(Figure 8 shown on next page.)

41 In the preface of the score, Adams suggested that while the triangles in “The Singing Tree” should be played by the singers, the percussion instruments in the other movements can be played by a professional percussionist, if preferred.

“The Singing Tree” is set for four solo sopranos and four solo altos, each also playing a triangle. The jaunty motives combined with the burble of the triangle produce a pleasant respite, a welcome oasis of earthly joy amidst the awesome expanse of the sun and sky movements. The bird calls are varied, occasionally imitating one another, but also contributing new sounds to the conversation. The repetitive patterns have a minimalist quality that is transfixing.

Just as captivating, “The Hour of the Doves” is also voiced for eight treble singers, with the soprano choir grouped in motivic unity and the altos carrying accompanying harmonic support. The sound of the dove is clearly heard in the soprano motive which is distinguished by a snappy dotted rhythm in 3/8 time, further emphasized by the specific articulation markings, which give the motive further shape (see fig. 9). This dove call is imitated in the remaining three soprano voices, sometimes with exact pitches and sometimes down a half step. The intervals between the entrances are not consistent, contributing an organic sensibility to the bird calls. The altos underpin these upper dialogues by providing more sustained harmonic counterpoint, creating a mesmerizing effect.

“Cadenza of the Mockingbird” is the most complicated of the bird movements. Written for four soprano voices, bells, maracas, and woodblock, this movement portrays the sassy calls of mockingbirds through the diverse motives, irregular mixed meter, varied syllabification, detailed articulation, and colorful percussion. The addition of grace notes, which accompany several of the motives, also adds to the unique call of the mockingbird. Harmonically speaking the different calls do not relate to one another, giving this movement a sense of mischievous fun through its atonal meanderings.

Picturesque in its hazy and cavernous setting, “Dream of the Canyon Wren” is scored for four sopranos and four solo altos with bells. There are two related motivic ideas that together conjure up an accurate sonic portrait of the title. The first motive is a series of descending thirds first introduced in eighth-notes, but eventually heard in a variety of rhythms, ranges, and voices. The complementary motive is often written in slower note values and consists of a descending scale of half steps that span a minor ninth. The effect is almost surreal between the overlapping parts and slowly descending figures, but the reverie is interrupted midway through when the orchestra bells enter with an unaccompanied solo based on the descending third figure (see fig. 10). The clarity of this call is conspicuous, as it distinctly outlines the call of the wren without the canyon echo. The high tessitura of the bells almost suggests that the bird is flying up above the canyon, unaffected by the resonant echo. When the choir enters again the entrances which were introduced in the first section are rearranged and loosely appear in reverse order by phrase. As the last two low alto notes die away near the end the bells enter for one last declamatory call.

Sandwiched between “Sky with Endless Stars” and “The Dark Wind,” “The Hour of the Owls” provides an eerie addition to this final night section. The four choirs return, but only using the tenors and basses for an eight-part choral texture, along with four male soloists. The choral parts sustain long chromatic lines that slowly rise up from the opening low E-sharp in the bass. At first these long, tied whole notes are in pairs making gentle tension and release, but as the other voices enter the dissonances become more prominent, resulting in a thicker and thornier texture. On top of this blanket of harmony, the four soloists enter with their owl hoots, tentative and sparse, with each voice claiming its own tonal material: bass one B–C–B; bass three G-sharp–A–G-sharp; bass two E-sharp–F-sharp–E-sharp. The bass one part is different from the other three, with a higher pitched call and faster rhythm, much more like the call of a female owl. Ultimately it is the individual hoot that dominates the final section of this movement, eventually merging with the choral parts on a unison middle C for the final six measures of singing.

Performance Considerations

In preparing and conducting Canticles of the Holy Wind , the technical challenges can be identified per movement type: sky, wind, and bird. Because the movements in these groups consist of similar compositional approaches, the musical considerations are related to one another. As a starting point, it will be helpful to recognize that performing this entire piece requires a choir with skill and stamina, most likely a professional choir or advanced collegiate chorus. Because of the sustained a cappella texture, re-pitching the chorus between movements might also be necessary. Because the four choirs are meant to be spaced apart from one another and soloists are asked to move around the space, venue selection will also need to be a consideration. Adams has suggested the selections from the larger work could be performed separately,42 so viewing the work in this way might make it more accessible to other choirs.

The sky movements are perhaps the most difficult sections of the work and require sopranos, altos, and tenors with skillful upper ranges and basses with solid low notes. “Sky with Four Suns” begins on a low D in all four bass parts, with the highest note of E-flat being reached at the climax of the piece. This two-octave-plus range coupled with the need for dynamic and vocal control is a rare find in bass singers. Likewise, the range for sopranos also poses a challenge, with the sustained high Cs and B-flats. Altos and tenors are also asked to sing at the extremes of their ranges, with altos peaking on F and tenors gliding all the way to high B-flats. Similar issues present in “Sky with Four Moons,” “Sky with Nameless Color,” and “Sky with Endless Stars,” although these three movements pose slightly less range extremes than movement one. Table four lists the ranges of these four movements, showing the trajectory from the brightness of the most extreme range in “Sky with Four Suns” to the most compact range in “Sky with Endless Stars.” (See table 4.)

In conjunction with the range issue, intonation also poses a challenge for these movements, given the long note values and extreme ranges.43 How wide to tune the many fifths and where to place the thirds is a decision that should come into consideration, especially if the singers can be trained to think harmonically about their function. Dynamic markings need to be regulated to accommodate ranges and balance between the voices, and the imitative texture between the four choirs requires further balancing.

42 Adams, interview with author.

43 During my interview with Donald Nally, he disclosed that these movements were the most difficult for these reasons and therefore challenging to record.

The four wind movements find their difficulty in the complicated rhythms that appear in each movement. Written in cut time with quarter=112, these four movements depend on the singers to feel these complex rhythms within their section and across the other choirs. This process is further complicated by the additional rhythmic intricacies of the other voice parts. The goal is to feel the irregular gusts of wind inherent in the different rhythms, but not to be consumed by the pedantic exactness of the rhythm. Ultimately, it is the gesture that emerges from the septuplet, nonuplet and decuplet that create these contrasting bursts of wind.44 The voice with the eighth-notes (refer to table 3) is especially important in establishing an aural structure, against which the other voices can place their rhythms. The conductor will serve the ensemble best by keeping the tactus and cuing major entrances, but should take care to not interfere with the organic flow of the rhythmic patterns.

With rapidly moving passages and mostly diatonic material, tuning is also an issue in these movements, although the challenge arises because of vocal agility issues, as opposed to the range issues encountered in the sky movements. Solidifying tuning between the voices will be dependent on matching vowels and locking into the diatonic patterns, as they cycle through the circle-of-fifths. Rehearsing these passages slowly and tuning against the sustained pitches will help to solidify the intervals, and rearranging the scale material to create a unified exercise for the four voice parts will be a great benefit. Each of the four movements contains specific scale degrees, and although the pitches are sung in varied patterns, hearing the melodic material in relation to the tonic will ensure that all sections are following the same tuning plan. (Table 5 lists the melodic material for all four wind movements.)

44 Donald Nally also suggests that these rhythms are best accomplished through feeling the gesture together, as opposed to an exacting calculation of the notated rhythm.

Provided soloists are well-chosen, the bird movements are less problematic overall. Coordination with the percussion and the singer movements are two new issues that arise in these movements, but the vocal parts are manageable and less complicated than the choral sections.

With the addition of orchestra bells, “Dream of the Hermit Thrush” relies on the singers to adjust their tuning to the bells, keeping in mind that the overtones produced from this instrument can be misleading. Rhythmically speaking, this movement should be conducted in a four pattern, with the understanding that the bass 1 part proceeds in a broad 3/2 pattern for the entirety of the piece. The triadic sonorities can be easily balanced between the eight solo voices if singers are conscious of the root of each chord and place the fifth and third accordingly.

“The Singing Tree” has much more independence between the eight solo voices and therefore is more dependent on the character of each voice. Because there are more articulation markings to interpret, decisions regarding parity between the voices is an issue to consider, as is the timbre of the soloists. Another concern is the volume of the eight triangles and whether the singers will have difficulty hearing above the din of the triangle (see fig. 11). Movement nine, “Cadenza of the Mockingbird,” shares similar performance concerns, with the four solo sopranos communicating with a variety of bird calls, each requiring a different characterization. The bells, maracas, and woodblock thicken the texture and require rhythmic coordination with the singers, whose bird motives are intertwined with the percussion in this movement.

(Figure 11 shown on next page.)

With the imitative and sparse texture, “The Hour of the Doves” calls for eight evenly-matched voices, preferably with no vibrato and slender tone. Because the voices move in and out of unison singing and close dissonance, uniformity of sound is paramount in this movement. Likewise, “Dream of the Canyon Wren” is dependent on uniform singing that can blend and balance as the echoes resound in the canyon. In this latter movement, it is necessary to maintain the pitch in the choral sections, since the bell cadenzas repeat the same material at the same pitch level.

“The Hour of the Owls” finds its challenge in the long softly sustained notes of the choral parts, which are highly exposed in the spacious texture (see fig. 12). The singers will need to carefully plan their staggered breaths, so that the seamless carpet of sound can be maintained. The bass soloists who punctuate the texture with their rhythmic calls are given the difficult task of finding their pitches from the muted pitches of the lower voices. The solo tenor voice also needs to find its way into the texture and maintain consistency between the seven individual entrances.

The Oxford Dictionary defines activism as “the use of vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change.” 45 Can the performance of a powerful piece of music be described as “vigorous campaigning?” Does music have the potency to bring about “social change?” And, to reiterate Aaron Allen’s earlier question, “Is the environmental crisis [even] relevant to music?” If we believe in the capacity of music to stir passion and arouse the spirit, then these answers must assuredly be a resounding yes! Certainly, John Luther Adams believes music is relevant to the cause:

When performed in its entirety, Canticles of the Holy Wind is a force of nature, metaphorically and literally. The contrasts between the sky, wind, and bird movements generate a vivid and spacious tapestry of color and sound, simultaneously transcendent and grounded. The technical means by which Adams invites us into these spaces create a new perspective on nature, one that is experienced through the sensuous encounter with sound. Ultimately, Canticles of the Holy Wind offers an opportunity to hear nature through the ears, imagination, and soul of a brilliant and skilled composer.

Conclusion

The work of John Luther Adams represents an ethos at large, musicians striving to make a difference by strengthening the listener’s relationship to the earth and all that lay therein. His work represents a growing trend in the field of music to explore environmental issues through the lens of music. Adams does not discuss his music as “political” or even “activist;” however, it is evident that he intends for his music to effect positive change in the world with respect to the environment.

The central truth of ecology is that everything in this world is connected to everything else. The great challenge now facing the human species is to live by this truth. We must reintegrate our fragmented consciousness and learn to live in harmony with the larger patterns of life on earth, or we risk our own extinction.

As a composer, it is my belief that music can contribute to the awakening of our ecological understanding. By deepening our awareness of our connections to the earth, music can provide a sounding model for the renewal of human consciousness and culture. Over the years this belief has led me from music inspired by the songs of birds, to landscape painting with tones, to elemental noise and beyond, in search of an ecology of music.46

In the field of choral music, composers, conductors, and choirs are searching for ways to engage with important social concerns through meaningful repertoire choices. The expanding awareness of climate change and other environmental plights is finding creative

45 Oxford Dictionary, s.v. “activism,” accessed March 7, 2021, https://www-oed-com.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/view/Entry/195 7?redirectedFrom=activism& ways of expression through choral music, as more composers find inspiration in this increasingly urgent topic. Adams has been at the forefront of this movement, exhibiting commitment, leadership, innovation, and passion as he forges new paths for the genre. His work is not forceful, yet it holds power: the power to persuade through the union of sound and nature reimagined in musical form. musicians should consider joining this “vigorous campaign.” Through thoughtful programming, choral conductors are in the unique position of persuading both their choristers and audience that the environmental crisis is a critical concern for our time. With an increasing number of repertoire options, choosing environmental choral repertoire as a programmatic theme offers a clear opportunity to be a part of the solution. The encouraging words of Adams remind us of our potential as musicians to effect change: “If my music can inspire people to listen more deeply to this miraculous world we inhabit, then I will have done what I can as a composer to help us navigate this perilous era of our own creation.”47

46 John Luther Adams, Slate, accessed February 5, 2021, https:// slate.com/culture/2015/02/john-luther-adams-grammy-winner-forbecome-ocean-discusses-politics-and-his-composition-process.html.

It is significant to note that my own research and interest in this field is a direct result of performing some of these pieces, a true testament to the influential nature of this work. In turn, my students have benefitted from our ongoing programming in this area. Having engaged my students on numerous environmental choral projects over the past ten years, I have been able to witness a growing ethos among the students, a work ethic that includes a sense of responsibility as young artists and stewards of the earth. We hope that our message also continues to reach our audiences, providing an alternative context to contemplate the complexities of modern ecology and a sustainable future.

—Kirsten Hedegaard

The growing environmental crisis requires urgent attention, and if music can play a role in bringing further awareness to these issues, then

Kirsten Hedegaard has enjoyed a varied career as a singer and conductor. She has performed with many early music specialists and has appeared as soloist and ensemble member with groups across the country. Currently Director of Choral and Vocal Activities at Loyola University Chicago, Hedegaard frequently serves as a guest conductor, clinician, and lecturer throughout the U.S. and abroad. As a co-founder of The EcoVoice Project and Artistic Director of the New Earth Ensemble, Hedegaard is dedicated to bringing together musicians and artists to explore how the arts can support environmental education and action.

47 Adams, “I want my art to matter,” The Guardian, accessed March 5, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/music/ 2018/oct/30/john-luther-adams-composer-become-ocean.