NORTH BY WINTER 2023 northwestern SHARING

When the Oregon claims that the university

When the Oregon claims that the university

the odds

Northwestern students bet big as sports gambling gains traction on college campuses. | pg. 21

An in-depth look into the role of the university president. | pg. 39

After Northwestern’s first Pow Wow last spring, NAISA leaders are thinking bigger. | pg. 34

What new Wildcard perk would you create?

Operational credit card that swipes out of NU’s endowment

The ability to remove one straight man from your discussion section each week

PRINT MANAGING EDITOR Jimmy He

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Mia Walvoord

EDITOR-AT-LARGE Brendan Le

SENIOR FEATURES EDITORS Naomi Birenbaum, Sela Breen, Emma Chiu, Yiming Fu, Maddy Rubin

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITORS Jenna Anderson, Sam Bull, Chloe Rappaport

SENIOR DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Eva Lariño, Brooklyn Moore, Tessa Paul, Iris Swarthout

ASSISTANT DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Alyce Brown, Noah Coyle

SENIOR PREGAME EDITORS Lauren Cohn, Sari Dashefsky, Samantha Stevens

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Ali Bianco

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Coop Daley

MANAGING EDITOR Kim Jao

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITORS Hope Cartwright, Astry Rodriguez

DIVERSITY, EQUITY & INCLUSION EDITORS

Rafaela Jinich, Sammi Li, Ashley Sanchez

NEWS EDITOR Arden Anderson

POLITICS EDITOR Elliot Oppenheim

ASSISTANT EDITOR Rafaela Jinich

Guaranteed NU Men’s Basketball tickets for every game

ASSISTANT PREGAME EDITORS Katie Keil, Olivia Kharrazi

SENIOR HANGOVER EDITORS Julia Lucas, Julianna Zitron

ASSISTANT HANGOVER EDITORS Bennie Goldfarb, Natalia Zadeh

Get-out-of-jail-free (Wild)card

meal

ENTERTAINMENT EDITORS Conner Dejacacion, Jaharia Knowles

ASSISTANT EDITOR Kelly Rappaport

LIFE + STYLE EDITOR Ashley Sanchez

SPORTS EDITORS AJ Anderson, Miles French

INTERACTIVES EDITOR Annie Xia

FEATURES EDITOR Ryan Morton

ASSISTANT EDITORS Darya Tadlaoui, Sara Xu

OPINION EDITOR Christine Mao

CREATIVE DIRECTORS Hope Cartwright, Emma Estberg

PHOTO DIRECTOR Eloise Apple

DESIGNERS Pat Chutijirawong, Iliana Garner, Abigail Lev, Esther Lim, Michelle Sheen, Raven Williams, Allie Yi, Allen Zhang

Free mold test strips

CREATIVE FREELANCE

WRITERS Jackson Baker, Ali Bianco, Hannah Cole, Coop Daley, Audrey Hettleman, Sam Lebeck, Charlotte Varnes

PHOTOGRAPHER Tyler Keim

COVER DESIGN BY HOPE CARTWRIGHT & EMMA ESTBERG

PHOTO OF MICHAEL SCHILL COURTESY OF OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

PHOTO OF MONEY LISCENSED UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS

PHOTO OF KELLOGG BUILDING LISCENSED UNDER UNSPLASH

PHOTO OF PROTEST SIGN BY ADAM EBERHARDT/EMERALD

PHOTO OF UNIVERSITY HALL LISCENSED UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS

PHOTO OF NORTHWESTERN SIGN BY HOPE CARTWRIGHT

THE NEW YORK TIMES LOGO LISCENSED UNDER WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Amaya Mikolič-Berrios

ASSISTANT EDITOR Mika Ellison

MULTIMEDIA EDITOR Jade Thomas

GRAPHICS EDITOR Olivia Abeyta

ASSISTANT EDITOR Iliana Garner

INSTAGRAM EDITOR Sela Breen

TWITTER EDITOR Nozizwe Msipa

TIKTOK EDITORS Lianna Amoruso, Stephanie Kontopanos

PUBLISHER Julianne Sun

EVENTS MANAGER Ellisya Lindsey

FUNDRAISING Lele Sukman Demello

MARKETING Sam Stevens

AD SALES Nicole Feldman

The future belongs to those who understand the art and science of marketing communications.

And that’s what you will learn at Medill IMC. You’ll create innovative marketing communications strategies and engage consumers in the digital age by working collaboratively with global companies, faculty and your peers. Our program will teach you the IMC “way of thinking” that focuses on understanding consumers and balances qualitative and quantitative data to build strong brands. Medill IMC will help set you apart from others in the industry and prepare you for the future. Take a Closer Look

www.medill.northwestern.edu

During one of the rst Sundays of Winter Quarter, I found myself having brunch with Mia, the magazine’s assistant managing editor. We bounced pitches o each other over wa es in my living room as I contemplated what it meant to lead a magazine. Throughout the next eight weeks, my de nition of leadership has expanded and evolved, threading itself through narratives cra ed by our reporters.

In our Pregame section, you’ll hear from three female DJs who are trailblazing Northwestern’s male-dominated mixing scene. Our Dance Floor section documents Northwestern swim and dive coach Katie Robinson’s commitment to excellence and explores the Associated Student Government’s critical role in elevating student voices.

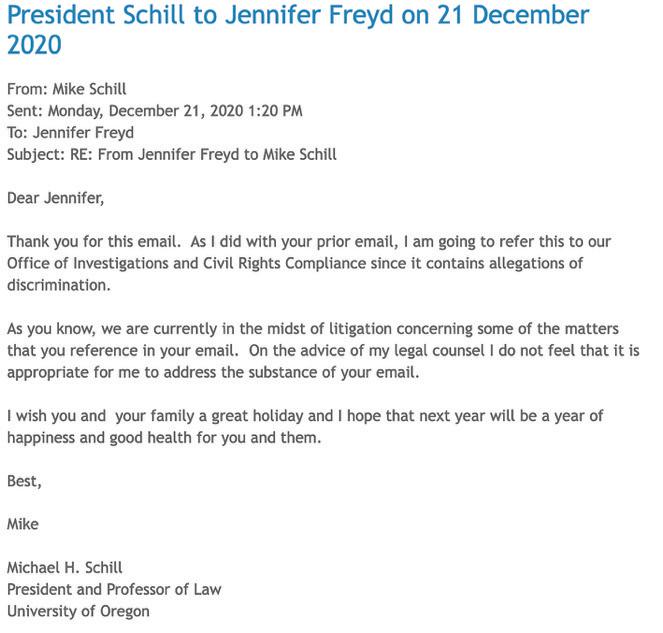

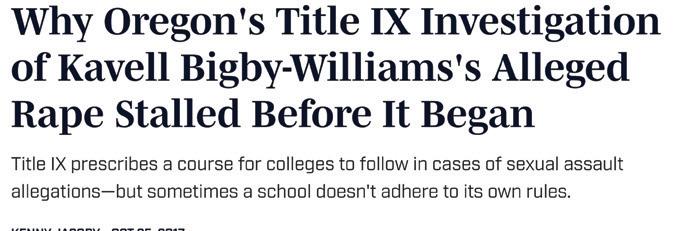

Our Features section spotlights two Indigenous students who are ambitiously determined to organize Northwestern’s biggest Pow Wow yet. Meanwhile, our cover story, “Sharing governance,” delves deep into the pivotal role of the university president,

examining President Michael Schill’s past tenure at the University of Oregon and his vision for Northwestern’s future.

I’ve watched our team come together week a er week, braving the Chicago snow and wind to attend our evening meetings in the McCormick Foundation Center. I’ve watched them grow and motivate each other to be their absolute best. For me, leadership has been about creating an environment that fosters growth, learning and empowerment.

All of this had led to the magazine you now hold in your hands. It’s an issue I couldn’t be more proud of producing and could never have done without the support of editors, designers and writers. I hope this issue of NBN provides you with the same valuable insights and inspiration that it has given me.

Sincerely,

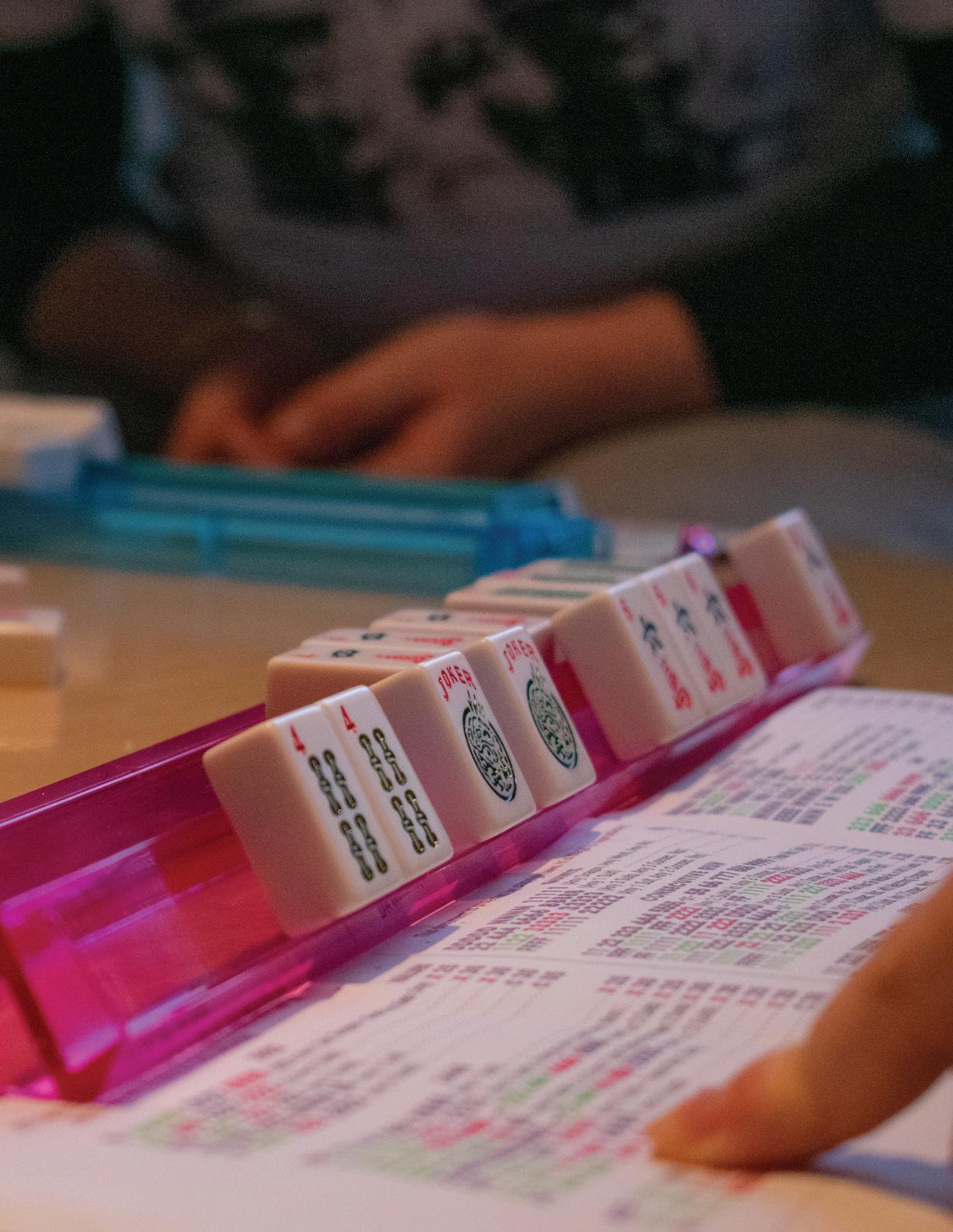

by tile, Northwestern students make their match.

WRITTEN BY NOAH COYLE // DESIGNED BY ABIGAIL LEV // PHOTO BY TYLER KEIM

IIt’s 4:30 p.m. on a Sunday, and two students are dragging tables to the middle of the basement in Northwestern Hillel, the center for Jewish life on campus. As students seat themselves eight to a table, one retrieves a canvas bag and pours out an array of red-and-green-printed tiles. Passing around a Cheez-It box, a game of mah-jongg begins.

Mah-jongg is a tile-based game of Chinese origin. A er gaining popularity in Shanghai in the late 19th century, it was introduced to the United States in the early 1920s. The game has since become a preferred pastime of Jewish American grandmothers.

SESP third-year Wendy Klunk, Hillel’s Religious & Spiritual Life Co-Chair, founded the Mah-jongg Club last fall.

A er advertising

a practice session on Hillel’s Instagram and through a newsletter last October, she drew in six curious students — one of whom was SESP rst-year and Hillel member Brooke Fein.

“The rst meeting was very exciting,” Fein says. “I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t know if people were gonna show up, but it was fun.”

From there, interest in the game grew in the Hillel community, and a group started to meet every Sunday.

While the goal of mah-jongg is to collect a matching set of tiles, the members of the club recognize another, more pressing objective of their meetings: Gossip. During the club’s two to three games every week, the participants go at a leisurely pace to chat as they play.

Another one of the Mah-jongg Club’s core tenets is inclusivity. The group is

students, regardless of skill level or if they are members of Hillel. To ensure that all who attend are able to participate in games, the club bends the rules of mahjongg to allow teamplay.

“I feel like at Northwestern, if you’re in clubs it’s either professional development or something for your resume,” Klunk says. “The Mah-jongg Club is really just for fun and for relaxing and for meeting new friends.”

At around 6:30 p.m., the nal round of mah-jongg draws to a close. The participants pack up their tiles, gather their belongings and leave to go about their evenings. Nearly all will be back next week to continue the tradition.

“The Mah-jongg Club is really just for fun and for relaxing and for meeting new friends.”

Wendy Klunk, SESP Third-Year

compares the prices of grocery store staples across Evanston.

or Northwestern students on a budget, grocery shopping can be a time-consuming tango of store-hopping while hunting for explored three popular Evanston grocery locations — D&D Finer Foods, Whole Foods and Jewelof some kitchen staples so you don’t have to. and

*Prices observed in January 2023.

SUGAR, 4 POUNDS

$2.99 $2.99 $1.99

$1.19 $1.49 $1.49

$3.99 $1.79 $1.99

$0.99 $0.79 $0.69

$1.59 $0.99 $0.99

$5.99 $1.99 $2.49

$3.29 $1.49 $0.99

$6.59 $6.39 $4.99

$8.99 $4.39 $6.49

$6.59 $4.49 $4.99

$2.99 $7.99 $4.99

$6.99 $5.99 $5.99

$3.99 $2.29 $2.99

$2.19 $4.49 $3.49

$7.99 $3.49 $7.49

$8.76 $3.79 $6.98 CHEERIOS, 1 BOX

$6.99 $5.69 $6.29 LENTILS, 1 POUND

$2.29 $3.19 $1.99 SPAGHETTI, 1 POUND RICE, 5 POUNDS TOTAL TEND CHANGE Item Count: 20 Time 07:02:46 PM THANK YOU TC# 1865 4588 0290 1963

Exploring the roles of Northwestern’s goal-oriented student sports team managers.

WRITTEN BY ELOISE APPLE // DESIGNED BY ALLIE YI

WWhen the Northwestern women’s volleyball team pulled an upset victory over Minnesota this fall, Weinberg secondyear Natalie Pizer couldn’t help but share in the excitement. As the team’s manager, Pizer spent hours doing data analytics, watching game footage and combing through statistics to strategize against their opponents. She felt as if her hard work had nally paid o

“[Fans] see the end product but not everything that goes into it,” Pizer says. “It’s nice that the coaches see how much we’ve worked because it’s not always very visible.”

Students can work as sports managers for various NCAA teams on campus, including volleyball, basketball and football.

The opportunity allows passionate students to immerse themselves in sports programs while also earning money.

When Medill second-year Massimo Cipriano isn’t in class, he spends most of his time working as the sports manager for the Northwestern Wildcats women’s basketball team.

Before practices, managers are in charge of preparing equipment, including basketball racks, towels and water. While players do drills, responsibilities range from running the scoreboards to rebounding shots. erward, the managers help clean up and head to the team meal.

to 24 hours a week. Although the time commitment makes it di cult to balance school, work and personal time, Weinberg second-year John Sprenger, the manager of the Northwestern Wildcats men’s basketball team, believes you have to be willing to make sacri ces in order to get the most out of the program.

As a Wilmette local, Sprenger grew up following Northwestern’s basketball team. For him, being a part of the organization he spent years watching has been a defining landmark of his Northwestern experience. He feels his role has grown beyond obligatory work responsibilities and provided him with fulfilling personal relationships with the players, coaches and fellow managers.

“It’s a very real-world responsibility,” Cipriano says. “Regardless of how low I am on the pyramid of basketball employees, there’s stu that I do that is very consequential and important for

Being a sports team manager requires students to build their academic schedule around practice times, with students working anywhere from 18

“At the end of the day, it’s the players playing,” Sprenger says. “But I do think that because we do so much with behind-the-scenes stu , when we do that correctly, it de nitely takes other things.”

Pizer says she’s forged strong relationships with both players and coaches on the women’s volleyball team. The coaches give her rides around campus and have written her internship recommendation letters.

At a banquet during the team’s senior night, the head coach called her up to recognize her contributions to the team in front of the whole room.

“I was like, ‘Wow, this is so cool,’” Pizer says. “He’s doing it in front of the whole team, all their parents — it was really nice that he was giving me that recognition.”

A Day in the Life of a men’s basketball manager

9 a.m. - 12 p.m.

Attend classes.

12 - 12:30 p.m.

Commute to Welsh-Ryan Arena.

12:30 - 4 p.m.

Set up practice with basketballs, pads, towels and water bottles. Help out during practice with rebounding, filling up water bottles and running the scoreboard.

4 - 5:30 p.m.

Finish practice, rebound for players after practice, clean up equipment and eat with the players and other managers.

5:30 - 6 p.m.

Commute back to campus.

6 - 11 p.m.

Arrive at dorm and do homework.

WRITTEN BY JULIANNA ZITRON // DESIGNED BY RAVEN WILLIAMS

ver 6,000 miles from Northwestern’s campus, Weinberg fourth-year Lu Poteshman arrives at Ruby Room in Tokyo, Japan, ready to take the stage as DJ Lu. Her usual audience consists of Northwestern students in the basements of o -campus houses or at A&O production events, but now, DJ Lu is eager to bring her music to an international audience.

Poteshman is not the only woman at Northwestern spinning tracks to get the party started. Back in Evanston, SESP fourth-year Haley Hooper plays a set at her friend’s party. Bienen second-year Lucy Rubinstein assumes her stage name, r00bies4ever, in Chicago’s underground music venue The Listening Room.

NBN sat down with three of Northwestern’s premier female DJs to discuss how they’re turning the tables in a traditionally male-dominated scene.

NBN: What is the origin story of your DJing career?

Lu Poteshman: I was always a musician, growing up as a classically trained violinist. But I sort of quit when I started college because it didn’t really t into my life anymore. Musically, it felt a bit restrictive. It didn’t have that freedom and individuality I wanted. So DJing was awesome because it’s all about freedom and individuality.

Haley Hooper to so many EDM and house shows when I was in high school. I became inspired by my favorite artist Rüfüs Du Sol in 2018 to get into this world of music. For my high school graduation gi to myself, I bought a DJ board o of Amazon and just started playing with the knobs and getting a feel for it. I did that for about a year. Then over COVID, I really

got serious about it and played sets in my basement every night of quarantine, just with my dog.

NBN: What does your mixing process look like?

Haley: The process of mixing is just going with whatever feels right in the moment based on how I’m feeling and how whoever I’m playing for feels. You can just operate from a sense of second nature because you know your music so well and you did your

Lucy Rubinstein: I’m the total opposite. I plan out every single transition, I plan out exactly where I’m going to start the track, exactly where I’m gonna do what kind of mixing — I do it because I get really bad stage fright. If I rely on improvisation, that really freaks me out. I’d rather plan it out and know exactly how the sets are gonna sound and feel and exactly what knobs I’m gonna twist when.

NBN: What experiences have you had navigating the DJ scene as a woman?

Lucy: Part of the reason I joined Streetbeat, the show on WNUR, is because there were no girls. I was like, “Oh, I want to freak them out. I want to be intimidating.” When I was learning to mix, it was me and like six frat guys. It’s been such a great experience to meet other people like Lu and Haley and to really show Northwestern this isn’t just another hobby that’s dominated by white men.

Lu: When I joined Streetbeat, I was invited to someone’s show to learn how to DJ. I walked in, and there’s seven white

guys just in the room. It was genuinely scary to decide to enter that space and make a space for myself in there. It’s di cult sometimes to not see other people like me re ected in the DJ community, both at Northwestern and in the world at large.

NBN: How do you support other women DJs on campus?

Haley: I was trying to nd out about other female DJs through word of mouth. Anytime I hear about a girl DJing or was interested in DJing, I follow them on Instagram.

Lu: When we’re dealing with the lack of representation that we are with female DJs and DJs of color, I think just a mere presence can be very helpful. So I hope by being a part of Streetbeat, and being on the executive board of WNUR, I can just show people that it’s possible to be in these roles and in these spaces.

NBN: What do you wish people knew about DJing?

Lucy: Through WNUR and my own personal side project, I’ve been planning events to create new spaces where people that don’t want to be at either a frat party or a club downtown, for everyone to just have fun, express themselves and enjoy music and be social.

Lu: All the time people ask me “What is DJing? What are you doing back there?” My explanation is that 50% of it is picking the music and having a music library and curating the setlist. And then 50% is just blending the two songs together and creating those seamless transitions so you can tell a story with the music.

Haley: With DJing, when I rst thought about it, I felt really pressured to play what I thought people wanted to hear. I was like, “Oh, I have to play these songs because people hear them on the radio or whatever.” And that’s not the case. DJing is an expression of you, of what you want to do.

Lucy: The best thing you can do to support a DJ is dance.

WRITTEN BY HANNAH COLE // DESIGNED BY HOPE CARTWRIGHT

“M

“Medical or recreational?” “Flower or edibles?”

“Indica or sativa?”

These are some choices you might encounter when entering an Illinois dispensary. Following recreational marijuana’s legalization in 2020, Evanston buyers can now purchase the substance from a budding business: Zen Leaf.

Located at 1804 Maple Ave. in downtown Evanston, the dispensary is across from BLICK Art Materials and the newly reopened AMC Cinema, two strong options for a post-smoke sesh.

Weinberg third-year Devyn Coar rst visited Zen Leaf when she turned 21. She searched online for a weed strain that would meet her needs and went to pick up the product in person.

Upon entering the store, employees immediately asked Coar for her ID. A er verifying her age, they gave her the items in her online order. As per Zen Leaf’s student discount, she also received 10% o the purchase.

Sometimes choosing the correct product is a joint e ort. Dispensary sta members, or budtenders, are happy to make recommendations. Nicholas Covington, manager of Zen Leaf’s Evanston location, says the sta are friendly and eager to assist rookie customers.

“If you’ve come to a budtender and you’re asking 100 million questions, that’s their job to answer,” Covington says. “So, being a rst-timer, I always tell people to be okay with not knowing [about weed] when you come in, and you’re not going to be judged for it.”

Depending on what e ects the purchaser desires, budtenders recommend di erent strains. While sativa is described as energetic and social, indica is more calming. Coar says she’s been smoking indica lately since it helps her feel relaxed.

Zen Leaf employees want all their customers to ride the high, but they also need to weed out underage purchasers. Don’t try using a fake ID at a dispensary, kids. All potential purchasers will have to pass not one, but two scans of their identi cation.

“Just because you got through the rst door, we still need to con rm we aren’t selling to an underage person,” Covington says.

There are also numerous restrictions and laws in Illinois that regulate how dispensaries sell their products, how they’re taxed and where that tax money goes.

For example, Covington says dispensaries cannot openly display cannabis. Illinois recreational marijuana taxes are also higher than most states. According to the Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois taxes 25% on products with a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) level higher than 35% and issues a 20% tax on products with a THC level under 35%.

“By legalizing it, we are trying to

In contrast, New Jersey levies a 6.625% tax for all recreational cannabis, with some varying local taxes.

According to the Chicago Tribune, Illinois’ marijuana tax money o en goes toward Chicago neighborhood development and substance abuse treatment. The Tribune also reported that Zen Leaf’s taxes fund Evanston’s $10 million reparations program, which aims to provide Black residents with funds for housing payments and repairs as a redress for racial discrimination.

Jojo Holm, Weinberg third-year destigmatize it.

“The project’s founder Robin Rue Simmons said in an interview with Evanston RoundTable that using a cannabis tax was an apt way to rectify Evanston’s over-policing of the Black community for marijuana use.

Despite the high taxes, Weinberg third-year Jojo Holm doesn’t consider the prices unfair.

“We’re in Evanston, so I think it makes sense that it’s just a little bit more expensive,” Holm says. “It felt really reasonable to me.”

Covington says he believes cannabis helps people, whether through government funding like the reparations program or in customers’ day-to-day lives. Holm believes that smoking is a more positive experience compared to drinking and can also strengthen friendships.

“The reality is, by legalizing it we are trying to destigmatize it,” Holm says. “I think that’s really great.”

A list of top spots to use your Wildcard discount.

WRITTEN BY SAM LEBECK // DESIGNED BY NAPAT CHUTIJIRAWONG

A Wildcard can do so much more than swipe students into dorms and dining halls. It opens doors to discounts at restaurants, stores and more in Evanston and Chicago — if you know where to look. More than 100 Evanston and Chicago businesses o er Wildcard discounts, from 10% o meal purchases to reduced prices at workout classes. NBN has compiled a list of Evanston and Chicago locations to take advantage of your Wildcard bene ts.

Ovo Frito Café: A favorite Evanston brunch destination, the distinctive yellow building welcomes students and o ers those who present their Wildcards 10% o their meal.

Blind Faith Cafe: Located on Dempster Street, this sustainabilityoriented Certi ed Green Restaurant o ers students 10% o their vegetarian menu. Kilwins: Known for drawing in passersby with their wide array of ice cream and fragrant fudge, Kilwins o ers students 10% o their purchases as well as a punch card to encourage returning buyers.

JR Dessert Bakery: Founded 30 years ago and run by a mother-daughter duo, JR

Dessert Bakery o ers 10% o any bakery item. From cheesecakes to brownies, every baked good is made with all-natural ingredients (available by 14-minute drive or taking the 201 bus route and transferring to the 97 bus at the Howard Street and Ridge Boulevard stop).

Evans Nail & Spa: This Noyes Street nail salon o ers $10 o non-chip manicures with the purchase of a pedicure.

CycleBar: Presenting a Wildcard can give students 33% o an indoor spin class with certi ed instructors, complete with workout metrics a er their ride.

Lock Chicago Escape Rooms: Despite having Chicago in the name, this Evanston-based escape room o ers a 15% discount on all bookings with a Wildcard. They o er unique adventures with multiple endings.

Zipcar: Students over 18 can join the car rental service for only $25 using their university email and Wildcard.

uBreakiFix: This electronics shop on Chicago Avenue o ers 10% o repairs when students show their Wildcards at dropo or pick-up.

Af nity CPR Training Center: Students must call and mention the Wildcard Advantage to receive 15% o any class, including basic rst aid and CPR.

Silver Spoon: This cozy Thai restaurant o ers 10% o for students with an ID. Located just o the Magni cent Mile, Silver Spoon is a hidden gem for those looking for authentic Thai o the beaten path ( ve-minute walk from Chicago Red Line stop).

Leonidas Cafe Chocolaterie: With locations in both Evanston and Chicago, Leonidas’ European-style cafe and chocolate shop o ers 10% o purchases for students with a Wildcard (Central Street in Evanston, two-minute walk from Chicago Red Line stop).

Art Institute of Chicago: This world-famous art museum, home to renowned paintings, sculptures and photographs, o ers free admission to students who show their undergraduate Wildcard at the ticketing counter or a $19 student ticket online ( ve-minute walk from Monroe Red Line stop).

Lyric Opera of Chicago: Lyric Opera, a preeminent nonpro t center of arts, o ers $20 student tickets to select performances (20-minute walk from Lake Red Line stop).

Kingston Mines: The largest and oldest continuously-operating blues club in Chicago, Kingston Mines o ers free entry on Thursdays to 21+ students that show their school IDs (10-minute walk from Fullerton Red Line stop).

Life Storage: With a valid Wildcard, students receive 10% o the in-store rate for storage solutions in Chicago.

312 Elements Headshot

Photography: Students can receive 50% o the Essential Headshot package, a 60-minute session including unlimited clothing changes and a complete digital download of the session.

Mattress King Chicago: With the presentation of a Wildcard, students in need of a mattress can forgo paying sales tax with their purchase.

EN BY JENNA ANDERSON // DESIGNED BY ESTHER Y ELOISEAPPLE

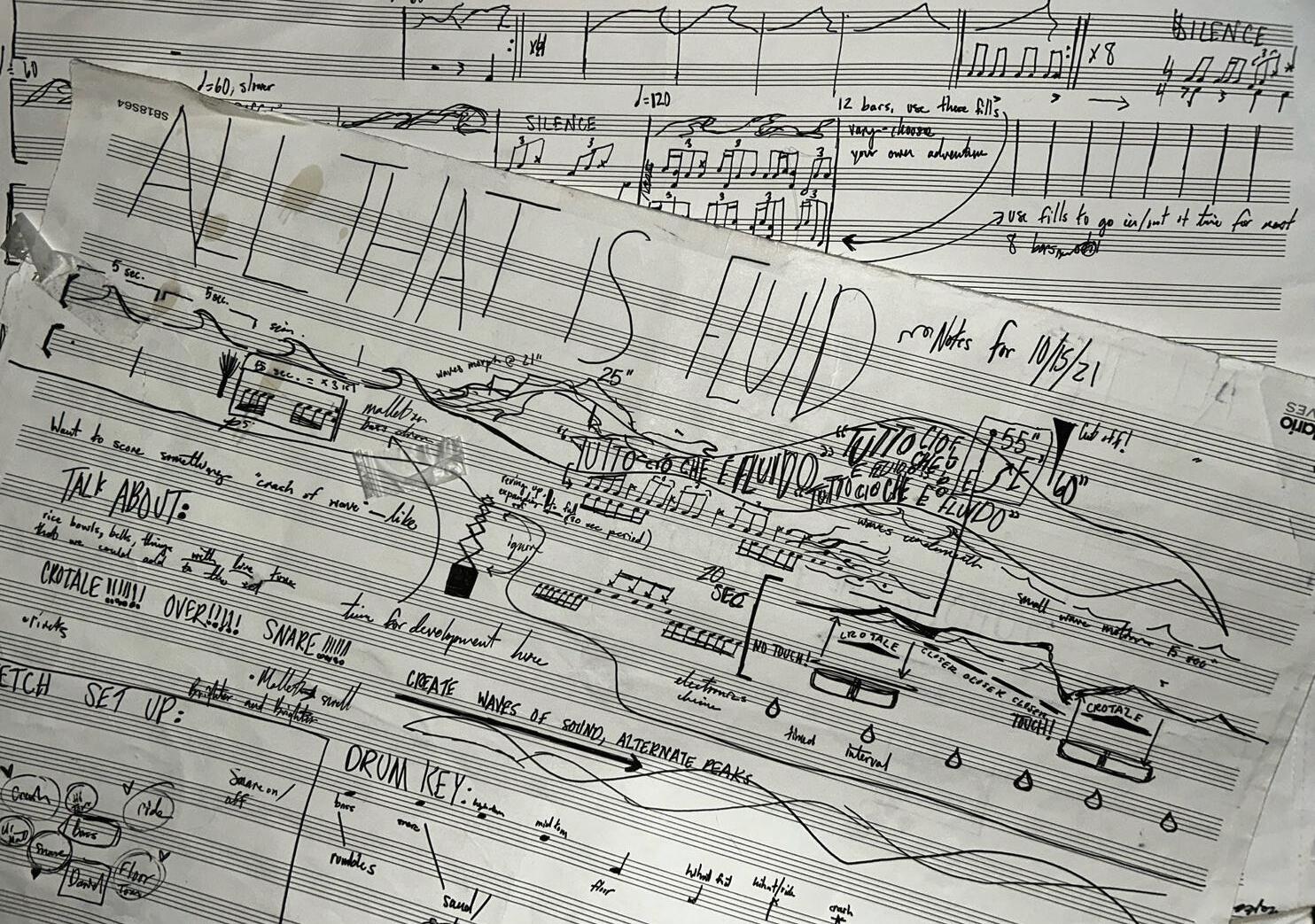

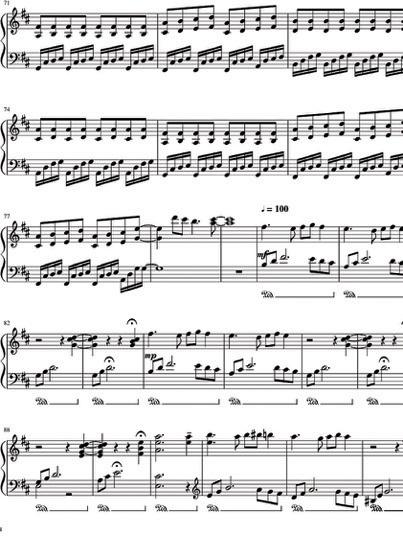

or student composers, music is more than a pregame playlist, car-ride jam or shower soundtrack. To them, music is an outlet for original artistic expression. With every bridge and chord, Mya Vandegri , Reva Sangal and Eli Gottsegen are developing their sound.

Mya Vandegri and the musicians of No Exit, a professional ensemble from Cleveland, Ohio, sat on the oor of a rehearsal room with an array of wine glasses. Drop by drop, they poured water for an hour until each glass rang with the desired musical note. The Bienen second-year was only 16 at the time, but she was already leading the rehearsal of her rst commissioned piece, “Non-Alcoholic Beverages.”

Vandegri composes modern Western classical music and describes her style as “experimental, contemporary, aesthetic.” The composition major from Wooster, Ohio, has plenty of projects in her portfolio, ranging from a solo piano piece to an orchestra arrangement. She spent the last 18 months working on her opera, “Creating Small Thunder,” which will premiere in April at the Wirtz Center for Performing Arts.

Vandegri started writing songs in elementary school. By middle school, looking for a challenge, she started composing instrumental music.

An early discovery that drew Vandegri to composing was her synesthesia. Synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon that links senses together; Vandegri says she associates sounds with colors. For instance, when she hears

hitting all the right notes.

a G major chord, she sees orange. (She told me my voice is army green and burgundy with a streak of yellow.)

“Any tonal noise has a little bit of a palette,” she says. “It’s like breathing. I forget it’s there.”

This phenomenon allows Vandegri to view sound as a “three-dimensional entity” — a noise, a color and a presence in the room. Vandegri says she uses her synesthesia to make her music “as full as it can be.”

Hans Thomalla, a German American composer and professor of music composition, has been working with Vandegri since she was a rst-year student. He admires her ambition to write her opera, which tells the story of a queer family in the rural Midwest.

“I nd it wonderful that she’s interested in such a broad concept of composition,” Thomalla says. “She’s quite aware of the world, and I nd this very impressive.”

Once Vandegri decides on the instruments and what she wants to write about, she gives herself the time and space to compose the music. But

her process isn’t linear — Vandegri explores an aspect she likes, then nds a place for it in the arrangement.

“Once I nd the destination, I build the world around it,” she says.

Vandegrift brings her finished composition to rehearsal, where she then collaborates with musicians to achieve her vision. After some rewriting and rehearsing, the piece is performance ready.

“It’s like giving birth in public,” Vandegrift says. “It might be a cute baby. It might be a bad baby. But it’s here.”

Vandegri plans on pursuing a career as a classical composer, speci cally in stage music. She says she’s grateful for the opportunity to create educational art — like her upcoming opera — in an environment that allows for mistakes and growth.

“I really don’t know what I’m doing,” Vandegrift says. “But I am here, and I have ideas. I’m trying to make the most of the opportunity of being at Northwestern and being able to write music here.”

Seated at the bench with her piano teacher, Reva Sangal placed her hands on the keys and prepared herself to perform at Carnegie Hall in New York City. At 14 years old, the Golden Key Piano Composition Competition had invited Sangal to the iconic venue to perform a piano duet she composed.

“I think I blacked out,” Sangal says.

The Communication third-year from Princeton, New Jersey, now composes contemporary musical theater songs. She is one of three writing coordinators for The Waa-Mu Show, Northwestern’s annual musical written, produced and performed entirely by students. This year’s production, a romantic comedy titled Romance en Route, will premiere in May.

Sangal says she’s always loved music. She remembers being obsessed with the Bollywood song “Barso Re” as a kid, always asking her parents to play it in the car.

“Little me had taste,” Sangal says. “That was my earliest memory of a song that I was connected to.

At 11 years old, Sangal performed in her rst musical theater production as Eulalie Mackecknie Shinn in The Music Man Jr. She says she’s been a “theater kid” ever since.

Sangal took piano lessons growing up. By high school, Sangal says she was getting bored of playing sonatas, so her piano teacher encouraged her to write music. With no formal training, Sangal started improvising on the piano and composed her first duet.

A er her sophomore year of high

school, Sangal was accepted to a twoweek summer composition intensive at the Berklee College of Music. She expanded her composing from piano to a woodwind trio and string quartet. When COVID hit, Sangal experienced a bit of a writing lull until she joined Waa-Mu as a second-year.

“Suddenly, everything opened up again,” Sangal says.

Sangal applied to Waa-Mu with her classical compositions and started writing musical theater songs for the rst time with the group. As a writing coordinator this year, Sangal leads the 25-person Writing Room, a studentorganized seminar during Winter Quarter to compose The Waa-Mu Show.

Having a large team of composers makes the massive endeavor of creating a musical possible, but Sangal says it can get complicated because everyone has their own artistic identity. Luckily, she says this year’s group has been wonderful.

“I could not feel more blessed with the amount of talented people who are on our team,” Sangal says. “They all are ready to create a musical that ts a group voice.”

Communication fourth-year and Waa-Mu co-chair Mitchell Huntley has worked with Sangal since she joined the Writing Room last year. He says she’s a fantastic collaborator and leader.

“She creates a really fun and inviting environment,” Huntley says. “You feel free to try things out — throw spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks.”

A er Waa-Mu, Sangal will begin writing a musical for her undergraduate capstone project, but she isn’t set on a career as a composer. Sangal is pursuing a minor in Legal Studies and a career in law. Nonetheless, she says music will always be part of her life and encourages anyone with a love for music to compose.

“Anyone can write music,” she says. “It’s not something you need a certain brain for, or you’re born with it — I don’t believe that. I think talent is nurtured.”

During his freshman year, Communication third-year Eli Gottsegen had an assignment for Theatre 120-0, “Production in Context,” to interview a Northwestern theatre faculty member and present it in a creative way. He interviewed a costume designer while his friend, Communication third-year Sophia Talwalkar, interviewed a director.

Then they had an idea: Let’s make a song.

Instead of spending an hour on the assignment like the rest of the class, they spent 20 hours writing “Only a Few Tomorrows,” a musical theater song about a costume designer and director who were excited to collaborate but had to take (at least) two weeks o for a pandemic. They got an A.

“There is magic in that song,” Gottsegen says. “It’s really one of the most special things I’ve ever been a part of.”

Gottsegen, from Larchmont, New York, composes pop and musical theater music. As a rst-year, he wrote for The Waa-Mu Show and joined the Writing Board as a second-year. He’s still involved in theater as a performer, and he is currently comusic director of Thunk A Cappella. Next year, Gottsegen plans to write a musical for his capstone project.

For most of his life, Gottsegen only really considered himself a musician. His mom gi ed him a violin for his third birthday, and he started taking lessons at four. He also took guitar lessons and taught himself how to play piano.

Gottsegen started writing songs for his band in the fall of his senior year of high school and developed as a composer during the rst COVID lockdown.

“The spring of 2020 is when I really started being like, ‘I’m not just a singer anymore, I’m not just a musician. This is what I really love,’” he says.

When Gottsegen composes, he says the music comes naturally, but the lyrics are harder. Sometimes, Gottsegen is overcome with emotion and runs to an instrument, writing about his own experiences. Other times, especially for musical theater, he’ll draw from what he’s read and watched to write about someone else’s perspective.

“I get overwhelmed by the ‘me’ part of it. When I’m writing about someone else, it’s so much less complex,” Gottsegen

says. “Then the coolest part happens, where you look back at it a er and go, ‘Huh. Who was I really writing about?’”

Gottsegen’s former professor told him this was related to the self-referential e ect — people’s tendency to remember information better when it has been linked to the self.

“You can’t help but include the tiniest bit of your life in theirs,” Gottsegen says. “How many people have compared Alexander Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda?”

It’s no surprise Gottsegen wrote “Only a Few Tomorrows” — a song about collaboration — with a partner. Talwalkar remembers going to Gottsegen’s dorm in

Bobb-McCulloch Hall at 11 p.m., sitting at the piano, and composing until 3 a.m. A er a few of these late nights, they pulled one nal all-nighter before the assignment was due.

“We were like two fanatic songwriters,” Talwalkar says. “He’s awesome to work with. He’s a perfectionist in the best way.”

Gottsegen isn’t sure what he’ll be doing in the future, but he knows it’ll be something related to music. It could be composing or performing — whichever door opens rst, he says.

“I’m learning. I’m growing. I’m changing,” Gottsegen says. “This is a journey, and I’m not anywhere near the end.”

Northwestern’s female pilots defy gravity and stereotypes.

WRITTEN BY KATIE KEIL

OOn a brisk February night last year, I met my doppelgänger. The brownhaired woman with dark eyes looked identical to me, except 30 years older and several inches taller. Her name also happened to be Katie.

Aside from our physical appearances, Captain Katie Overdiek and I shared one other striking similarity: We’re both female pilots in a male-dominated eld.

Since the age of two, I’ve dreamt of being an airline pilot. I began ying lessons at 14 and earned my pilot’s license in 2020 at 17 years old. According to national estimates, women make up only 8.4% of pilots worldwide, making it harder for aspiring female aviators like me to nd a community in the industry.

I’ve found my main support system in Northwestern’s Aviation Club, where I use my passion for ying to form new connections. Evanston’s proximity to numerous small air elds within the greater Chicago area makes aviation training relatively accessible, but a welcoming community of women helps immeasurably with navigating the eld.

I remember spending countless evenings at the platform of my local train station as a kid, watching the planes glitter in the night sky.

While many pilots typically join the aviation industry with help from family connections, women o en don’t have this privilege due to historical barriers to entry. Instead, many like myself tend to join out of sheer curiosity about aviation.

Although my introduction to the eld occurred on the ground, other women’s rst experiences happened through exposure. Weinberg fourthyear Tyler Greene began ying through a partnership between her local high school in Aspen, Colorado, and a ight institution at the nearby air eld.

“I just fell in love with it immediately,” Greene says. “I thought it was such a

special experience to be behind the controls and have something that you do physically change the course of a plane.”

The process of earning a pilot’s license can be expensive, with costs ranging from $6,000 to more than $20,000 depending on the speci own and ight time. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations stipulate that individuals must have at least 40 hours of ying experience.

Some schools, like Purdue University, offer aviation-related majors that allow students to build flight hours while earning their bachelor’s degrees. Flight instructor Kate Thurmond, whom I frequently flew with this past summer, graduated from Purdue’s program in 2022. She emphasized its impact on her professional development.

“I feel like it gave me more of a good background when it comes to what to stand on in aviation,” Thurmond says. “It gave me a lot deeper understanding of the aviation industry as a whole.”

Northwestern o ers over 100 majors and minors but no programs to study aviation, so interested students must independently seek out opportunities.

Greene shares a similar experience, citing her interest in exploring a field she wasn’t studying academically.

As I approached the Aviation Club table at Northwestern’s Fall Quarter club fair, Weinberg third-year Elie Clark jumped up and welcomed me enthusiastically, exclaiming, “We’ve been waiting for you to come by!”

Northwestern’s Aviation Club combines social and professional aspects of aviation, with activities including airline pilot presentations, discussions on student ight training and occasional one-on-one ights with the club’s president. Clark says many of these events helped her form bonds with other students interested in aviation.

“I really wanted to have some kind of a community, and the club gave me

“I knew I wasn’t going to be doing as much [with aviation] as I was at home,” Greene says. “I wanted to have some a liation to aviation and aeronautics.”

Northwestern’s Aviation Club welcomes individuals from all training backgrounds. As the treasurer, Clark is intent on reducing nancial barriers for those who may be interested in pursuing aviation but lack the resources to do so.

She is currently working on developing a scholarship program in memory of Daniel Perelman, a Weinberg rst-year who passed away last year in an aviation accident. Additionally, the club is organizing a yearly safety seminar in Perelman’s memory to promote awareness toward accident prevention.

“We’re all pilots, so we can honor him through aviation,” Clark says. “There’s still that connection.”

The male-dominated runway

One of the many problems women who aspire to join the aviation industry face is a lack of representation. Overdiek, the pilot I encountered last February, has rarely worked alongside other women while ying for a major U.S. commercial airline.

“In 15 years of commercial aviation, I’ve only own with 10 female pilots,” she says. At her airline, 6% of pilots are women.

As the rst female instructor at her ight school in New York, Thurmond has noticed a recent uptick in interest from female-identifying students. Still, the vast majority of those enrolled are male.

“It’s de nitely one of those things where it’s still skewed male-dominated, but there’s de nitely an in ux of women who are interested in it,” Thurmond says.

According to the FAA, 14.2% of student pilots in 2020 were women. To support these female pilots, non-pro t organizations such as Women in Aviation International (WAI) provide annual scholarships to increase access to training and other resources. This February, WAI provided $889,140 in awards during the 34th Annual Women in Aviation International Conference.

Both Thurmond and Overdiek have re ected on how their experiences as

“ In 15 years of commercial aviation, I’ve only flown with

Captain Katie Overdiek

as they’ve taken on leadership roles.

Whether it’s becoming an instructor or an airline captain, women take on greater positions which allow them to expand their platforms and advocate for more representation.

According to Overdiek, gender doesn’t, and shouldn’t, play a role in piloting ability.

“I wouldn’t say being a female is any di erent,” she says. “I don’t think there’s a di erence between male and female in terms of getting the job done.”

Since arriving at Northwestern as a rst-year this past fall, I’ve found it di to continue training given the lack of a formal program. Yet, my ultimate goal of becoming an airline pilot is supported by a community of likeminded women.

While Greene admits being a woman in aviation is intimidating at times, she acknowledges the bene of a tight-knit community.

“When you have more of a small environment and personal time with your instructor, I think that changes the whole game,” Greene says.

Northwestern’s Aviation Club provides the intimate network many aviation enthusiasts, especially those pursuing careers in the industry, seek out. The club continues to incorporate

activities, from airport tours to aviation safety presentations.

As Clark prepares to take on the club presidency this year, she hopes to turn Northwestern’s Aviation Club into an educational space, both for students who are already interested in aviation and for those who have little background in the field.

“It’s such a mysti ed industry,” Clark says. “People lose their minds when I tell them I have my pilot’s license. I’d like to make it a little less abstract.”

Northwestern students bet big as sports gambling gains traction on college campuses.

// DESIGNED BY NAPAT CHUTIJIRAWONG

according to the International Center for Responsible Gambling.

“Before I cracked the code, I was losing all my little 16, 17-year-old savings,” Liam* says. “I know the ect that it can have, and I know for pretty much every person out there that gambles, or for a lot of people that struggle with it, it causes a lot of problems.”

Over the past year, Liam* has consistently placed substantial wagers on an o shore site called Bovada. In December 2022, Liam* risked approximately $75,000 across 598 individual bets. Three hundred and een of them resulted in winnings. With a win rate of 52.68% that month, he pro ted around $2,000 — an average month for him.

Not all months are quite as successful, however. The week leading up to his major win with the Broncos resulted in a setback of almost $3,000.

TTgame was in full swing, but for Weinberg second-year Liam*, the real action was not on the eld but rather in the numbers across his computer screen. He had placed a $50 bet that Tim Patrick, the Broncos’ wide receiver, would catch at least eight passes during the game.

Seven catches in and Liam* was on the edge of his seat, eager for the next play. The ball was thrown, soaring toward its target, and Patrick reached his arms out. Liam’s* heart began to race, and a smile spread across his face.

Patrick made the catch, and Liam won $800. This sense of success, the rush of adrenaline and the excitement of the win was addictive — Liam craved this feeling.

Engaging in sports betting is not uncommon for many college-aged students. Approximately 75% of college students gambled during the past year (legally or illegally), with about 18% gambling weekly or more frequently,

Gambling opportunities, previously available in only a few states, multiplied following the 2018 Supreme Court decision to legalize sports betting. The expansion of internet gambling and of sportsbooks — a place or website where a gambler can wager on various sports competitions — have intricately linked sports to gambling.

“I still was doing everything the same, but at the end of the day, I can’t control these NBA players or these NFL players,” he says. “They’re gonna play how they play, and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Liam* rst introduced to online

75% of college students gambled during 2022

(International Center for Responsible Gambling)

a behavior like gambling, their brain’s reward system, centered around the release of dopamine, undergoes a signi cant shi . Over time, the brain rewires so that the individual experiences less positive satisfaction from anything other than the addictive behavior.

“Even in the face of negative consequences, they’re prioritizing the reward that comes from the addictive behavior, more so than the consequences that come along with that particular behavior,” Nusslock says.

With sports betting’s potential for fast money and instant grati cation, it’s unsurprising that many young adults and teenagers are immersed in it. It’s not only easily accessible — all that’s needed is a phone and internet connection — but socially acceptable and widely promoted.

The sports gambling industry is dominated by four licensed sportsbooks: FanDuel, Dra Kings, BetMGM and Caesars, which spend hundreds of millions of dollars on ad campaigns and celebrity endorsements. They entice new gamblers with “risk-free” bets or bonuses for their rst wagers.

As of November 2022, at least eight universities’ athletic departments have partnered with online sports-betting companies, according to The New York Times. These partnerships allow sportsbooks to advertise directly to students on campus, at athletic events and in students’ email inboxes.

In contrast to other industries selling addictive products, such as tobacco, there are no advertising rules speci c to the

sports betting industry at a federal level. This lack of oversight and regulation is particularly concerning for college-aged students who are susceptible to addiction.

While some students like Liam* treat sports gambling as a part-time job and dedicate a signi cant amount of time to researching bets with the goal of nancial gain, others bet small amounts, seeing it as a harmless addition to the viewing experience.

Communication third-year Caleb* bets purely for entertainment’s sake, putting $10 or $20 down as a way to deepen his engagement.

Caleb* bets by setting a budget each season and tracking his wins and losses.

“My mindset is that once I put a bet down, that money is gone, and if I win it back, it’s a bonus,” Caleb “Watching the game just to watch the game is fun, but it’s not as fun as when you have a team to root for. You cheer the whole time, you get invested and you feel like you have been a fan of that team for a while just because you have the money on it.”

the “vig” or “juice,” which is a fee charged by sportsbooks for taking a bet.

To bypass age restrictions, underage bettors o en turn to illegal intermediaries, known as bookies and agents. The bookie acts as a middleman between bettors and the agent, who has direct contact with the sportsbook. The agent is responsible for accepting bets from the bettors and placing them with the sportsbook,

used to work as a bookie for many of his friends at Northwestern but stopped due to the overwhelming workload and associated risks.

is if you really trust the people you’re working with because you can’t lose,” Bodhi * says. “If the people on your book lose money that week, then you get 15% of it. And if they win, then all you’re doing is transferring money.”

“ “ They’re prioritizing the reward that comes from the addictive behavior.

Robin Nusslock, Northwestern psychology professor

A major problem in the illicit betting world is people not paying what they owe. Because these bets are not made through a registered sportsbook, the entire system operates outside the law, and there is no legal recourse for collecting debts.

Bodhi* encountered this issue with one of his bettors who had fallen behind on paying what was owed.

“I told him the truth that he was scumming me. And I was like ‘I

realize this is shitty for you, but right now, I have a guy asking me for $2,000, and it’s not coming out of my own pocket, so you’re just fucking me,’” Bodhi * says. “He just felt bad enough and he probably wanted to bet again with me in the future, so he paid.”

Weinberg third-year James* initially approached betting as a leisure activity with friends but quickly began to optimize his strategy. James* now places substantial bets of up to hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, determined to beat the odds.

“It’s life-changing,” he says. “A few of us are under the guise that while it is taxing and tiring and stressful, it’s very much worth it.”

is over-adjusted, and given this, optimally wager on that.”

For Liam*, sports betting is about nding an edge over the oddsmakers through extensive research, analysis and a little bit of luck. He advises people interested in betting to never gamble more than they can and to never expect to win bets based on previous trends.

“

James* devotes extensive time to researching and analyzing his bets, yet he says he o en grapples with whether the opportunity cost is high enough. He and his friends always come back to the conclusion that as a college student, there is no other job that provides the nancial ts of sports betting.

“I wouldn’t say I have any particular says. “I couldn’t tell you who’s gonna win any game in particular, but I can analyze the markets and tell you where I think a [point spread for a game]

“That’s how they get you every time, and that’s why so many people lose,” Liam* says. “People think they know sports better than these billion-dollar gambling companies, but they just don’t at the end of the day.”

* Names have been changed to preserve anonymity.

People think they know sports better than these billion-dollar gambling companies, but they just don’t at the end of the day.

Liam*, Weinberg second-year

“

MOORE // DESIGNED BY ABIGAIL LEV

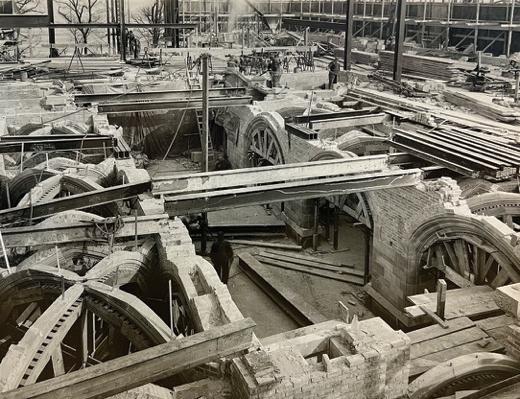

nscribed above the interior front doors of Deering Library is the phrase “aut legere scribenda, aut scribere legenda,” meaning “to read something worthy of being written” and “to write something worthy of being read.” Each day, students le in and out of Deering to ll this purpose.

Ninety years ago, Deering opened its doors to its rst patrons. A welcome replacement for the previous Lunt Library, now Lunt Hall, Deering continues to stand as a campus landmark and a key embodiment of the Northwestern experience. Students can count on a quiet reading room, a picturesque garden landscape and a rolling meadow to support their studying. In celebration of Deering’s rst 90 years of existence, NBN is taking a look back on the library’s illustrious history.

When built in 1894, Lunt was widely regarded as the nest library in the West. But by 1919, when Theodore Koch became Northwestern Librarian, Lunt appeared dilapidated. Both the University collection and the student body had outgrown the space. Initially built to hold 100,000 volumes, Lunt housed 120,000 when Koch arrived. He immediately set out to improve the outdated library system.

“Mr. Koch came to the University at a time when our library was poorly organized and rendering only a mediocre

service. He at once injected new life into the organization,” Franklyn B. Snyder, Northwestern’s president at the time, said at Koch’s funeral service in 1941. “Indeed, it may be said that he put our library on the map.”

Koch submitted annual librarian reports to the university president, each time noting the desperate need for a new space.

“Thousands of books have been boxed and stored in the basement of Fisk Hall on account of lack of shelf room in the Library,” Koch said in a 1921 report, 12 years before Deering opened. “Books are piled on the oor and on ledges.”

In 1929, Charles Deering donated $500,000, and the University immediately set the donation aside for a new library. Its location would display views of the lake on one side and of campus on the other.

The University hired famed collegiate gothic architect James Gamble Rogers to design the library. His previous works included Yale University buildings and Northwestern’s Chicago Campus. Koch chose the gothic style present today.

“No other architectural style, unless it be the Greek, has expressed more adequately the upward reaching of man’s spirit,” Koch said.

Deering opened its doors in 1933. Despite the building’s construction at the height of the Great Depression, it exudes opulence and grandeur.

Sculptor Rene Pail Chambellan completed the carvings featured in the library, like the Northwestern ‘N’ above the reading room. The edi ce is comprised of limestone and features 68 stained glass windows, each depicting mythological gures, literary references or historical scenes.

Koch served the University until his death in 1941, overseeing Deering’s construction and the transfer of volumes.

A er Koch passed, E e Keith served as the interim university librarian. During her tenure, Keith founded the Technological Library and acquired 25,000 volumes. She also oversaw the library during World War II when more students came to Northwestern to train at the Navy’s Midshipmen school.

The enrollment increase is attributed to the initiation of various military-adjacent training programs on Northwestern’s campus. As more men came to live in Evanston to study and train at Northwestern, the library struggled to serve all its patrons with

50% less staff members than before the war.

A er the training camps closed and men came home from the war, Northwestern again su ered from overcrowded buildings and struggled to provide housing to returning soldiers. Deering Meadow, out tted with metal tents, temporarily housed many veteran families.

As time went by, the university library collection grew. In July of 1950, Deering held a ceremony for the shelving of its one-millionth book — presented by Roger McCormick, who placed the rst on Deering’s shelves when he was 13 years old. By 1951, books outnumbered Deering’s shelving capacity.

“Its most urgent need is an addition to the building,” The Evanston Review wrote in 1951. “This not be an airy dream but a concrete necessity if Northwestern is to fulfill the purpose for which it has been shaped during a century’s growth and development.”

In 1967, Northwestern received a donation totaling $4.1 million, given by the Engleheart family. With this donation, Northwestern hired Walter Netsch and the rm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Architectural designs and expansion plans began. University Library, also known as Main Library, would be built with an underground attachment to Deering.

“The three towers of the new Main Library, opened in 1970, emphasized the antiquity of Deering’s design while also usurping its status as a state-of-theart library; this newcomer was the library that would see us into the electronic age,” Janet Olson says in her book Deering Library: An Illustrated History.

Main was an architectural gem at the time of its construction. The brutalist style had become popular during the mid-20th century, and its strikingly modern design garnered praise. John

McGowan, then the university librarian, described Main as “a distinguished building of rare architectural merit.”

“The new library had as much vision, theory and passion behind its planning as had gone into Deering, with a result totally di erent — re ecting the aesthetic of the times, advances in technology and new interpretations of the purpose of a library,” Olson writes, highlighting the juxtaposition of styles between Main and Deering libraries.

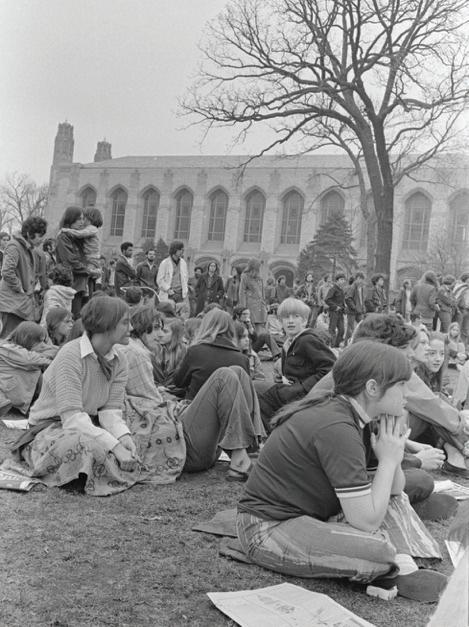

Even with Main’s construction and development, Deering was far from forgotten. Just months a er Main’s opening ceremony, anti-Vietnam War protestors used Deering as their backdrop. A er the tragic Kent State University shootings, anti-war students at Northwestern organized massive demonstrations on Deering Meadow.

During May of 1970, students held mock funerals on Deering Meadow and heard from various speakers, including Eva Je erson Paterson, a Northwestern student and famous activist. Almost 4,000 people attended daily protests at the site. O en an event locale or common meeting place, the area housed anti-Iraq

War protests in 2003 and a mental health awareness exhibit in 2015.

More o en, however, Deering and Deering Meadow host student celebrations, homecoming pep rallies and club pick-up games. You can nd dogs frolicking outside on the lawn and students hunched over computers inside, cramming for exams.

Every fall, new students “march through the arch” and nd their way to a ceremony on Deering Meadow, marking the beginning of their Northwestern career. Every spring, the Northwestern convocation takes place at the same spot.

The ceremony has hosted notable gures like the late Supreme Court Justice and feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1998, former President Barack Obama in 2006 and alumnus and comedian Stephen Colbert in 2011. Students sit with family and friends, waiting for their hard-earned moment of walking across the stage and receiving their Northwestern diplomas.

Deering is where students have gathered to shape their Northwestern experience — in the past, present and future.

WRITTEN BY CHARLOTTE VARNES // DESIGNED BY ALLIE YI // PHOTOS BY ELOISE APPLE

fateful phone call in June 2020 kickstarted one of the best days of Katie Robinson’s life.

Robinson, previously the associate head coach of swimming and diving at Northwestern, had recently interviewed for the head coaching position. A er one of the job’s early interview rounds, she cried, feeling certain she wouldn’t be hired.

When Robinson received the call from then-Athletics Director Jim Phillips in June 2020, she cried again. But this

my mantra: I don’t want to do this alone. I want so badly to do this with others and surround myself on this journey.”

Robinson is one of just two women coaching a combined men’s and women’s swimming program in the Power Five conferences, which includes the Atlantic Coast Conference, Big Ten, Big 12, Paci c-12 and the SEC. She is also one of just six female head coaches among all women’s and men’s swimming programs in the Power Five. Robinson is part of a

recognized the impact her coaches had on her both in and out of the pool.

“Some of the lessons they taught through swimming have stuck with me to this day,” Robinson says. “I just wanted to make a positive impact on other people.”

Robinson recalls a day when she was struggling at practice and felt embarrassed a er getting out of the pool. Her coach, Jill Sterkel, pulled her aside and told her, “‘Anybody can swim fast on the days it feels easy. It’s what you do when it’s hard.

“Katie, to me, was somebody who would embrace hard work and have fun with it,” Brackin says. “She could be making jokes or talking to her teammates or engaging while she was doing something challenging. I loved that about her.”

Robinson graduated from UT Austin as an 11-time All-American and was a Big 12 nominee for NCAA Female Athlete of the Year. She went on to serve as an assistant coach at the University of the

day and feels it’s normalized in the swimming world. It’s something Robinson experiences even among her swimmers at Northwestern.

“If I say something and my assistant coach, who’s a male, says the same thing, it’s received better sometimes from him versus me,” Robinson says. “[Gender bias] is something I think about a lot. It’s something I do my best to counteract.”

head coach at Northwestern, Robinson continues to lead the program to new heights. As of February, the women’s program ranks 20th nationally, according to the College Swimming and Diving Coaches

Championship in 2021.

For Robinson, these opportunities have been years in the making. She says she’s had a strong work ethic since she was young.

“I’ve always been somebody who [says], ‘Tell me what I can’t do and I’ll prove you wrong,’” Robinson says. “I’ve always had that chip on my shoulder.”

Robinson’s work ethic stands out to her swimmers as well. Public policy and administration graduate student Miriam Guevara says Robinson’s constant desire to learn, whether getting to know her swimmers better or improving as a coach, is inspiring and sets her apart.

balance being competitive, being erce and aggressive, [with being] light-hearted and joyful,” Guevara says.

Weinberg fourth-year and swimmer Ethan Churilla was part of Robinson’s primary coaching group during his freshman year. He says meets have led to some of the most memorable moments with Robinson.

Some Northwestern students opt for housing further from campus for cheaper prices.

WRITTEN BY IRIS SWARTHOUT // DESIGNED BY HOPE CARTWRIGHT

RRogers Park’s bustling energy is immediately discernible a er getting o at the CTA Jarvis stop. A coin laundry service sits beside a pet salon, and across the road rests a quaint cafe with a street-beat ambiance provided by the melodies of Earl Sweatshirt.

Charmer’s Cafe is one of Weinberg fourth-year Myckynzie Schroeder’s favorite places to study and grab a bite to eat. The spot, one of the many restaurants she enjoys in the area, is a ve-minute walk from her apartment on West Fargo Avenue. Rogers Park’s cheaper prices and later hours present a stark contrast to the early-to-bed eateries Northwestern students are accustomed to in Evanston.

“In the summer, [Rogers Park] had a lot of cool little arts festivals and salsa nights in the street,” Schroeder says, petting her cat Suki in the living room of her 13thoor apartment. “In the winter, it’s harder to nd that kind of stu , but there’s kind of always something going on nearby.”

Schroeder and her roommate Weinberg fourth-year Bintou Sonko’s

two-bedroom apartment costs $1,550 per month. Compared to Evanston’s prices, it’s not only a steal, but also better quality.

“I pay less for my apartment here, and it’s probably one-and-a-half times the size of our old place and it has so many more amenities,” Sonko says. “In my old place, the floors were really creaky. You couldn’t really get maintenance when you needed it.”

Neighborhoods close to Chicago’s downtown area are appealing to younger crowds looking for a bustling nightlife, a larger variety of cuisines and, like Sonko and Schroeder, cheaper rent. Though housing in Evanston is convenient for the more campuscentralized undergraduate student body, its rising prices push some students elsewhere.

Uptown, for instance, is within walking distance of Argyle’s Asian eateries and Andersonville’s main street. Driskill graduate student Ari Halle attends Northwestern’s Chicago campus and lives in an Uptown studio

apartment with their partner. They each pay around $500 a month for split rent and utilities.

Because they don’t own a car, Halle says the commute to campus is 45 minutes, including the walk to and from the Red Line and the ride itself. However, between their home and campus, they say there are plenty of restaurants and entertainment venues.

“It’s really easy for me to take the train two stops down and there’s a whole new group of restaurants because I’m in a completely different neighborhood,” they say. “I feel like I’ve definitely had to branch out and eat out at different restaurants a lot more.”

McCormick fourth-year Alex Cindric’s Lakeview East apartment is even closer to downtown Chicago than Schroeder’s. She pays around $800 a month for her room, a solid $100 cheaper than the Evanston rent prices she came across while looking for housing.

Cindric’s roommate, Segal master’s student Lindsay Lipschultz, says the

apartment’s accessibility to the CTA made the move appealing.

“In Evanston, it always felt like a major drag to go to a nice restaurant or a concert,” Lipschultz says. “Now, it’s like a 20-minute ride on the bus.”

Despite students’ positive experiences with lower rent prices closer to the city, others, like Evanston landlord Jeanne Laseman, have seen housing rates rise across Chicago.

Laseman currently lives in and leases out rooms in a house on the corner of Golf Road and McCormick Boulevard in Evanston, about a 10-minute drive, 13-minute bike ride or 45-minute walk from campus. She charges around $650 per month for a room, which includes utilities and laundry.

But Laseman says students haven’t been as keen to take her o er as she expected.

“I nd that kind of interesting, that dynamic, because I’m cheaper,” she says. “It’s just not the location that they want in Evanston.”

Laseman’s rent is an anomaly in a city where the average cost is around $900. Just a few years ago, Evanston’s high prices stood out like a sore thumb. But gentri cation, a process where lower-income residents are displaced to areas farther away from the city due to highpriced buy-outs, has made many places along the northern stretch of the CTA Red Line similarly expensive.

Evanston has always been on the high end of the spectrum. According to Laseman, the tax structure of the city accounts for an increased reliance on tenant funds.

Northwestern doesn’t pay property taxes despite continually expanding on city property, Laseman says. She adds that a multitude of non-pro t organizations and churches are also exempt from property taxes, which places a heavier tax burden on the small number of retail businesses that have become integral to the city’s revenue.

Apartments for lease are also subject to Evanston’s elevated property taxes, and as a result, rent prices have increased.

Kiley Korey, who has been taking private choral lessons at Bienen, chose an apartment in Rogers Park about two years

“ago when she moved to the Chicago area. The Rogers Park area is diverse and familyfriendly, she says.

According to her, rent prices in Evanston were exceedingly high at the time. But now, Korey is thinking about moving to Evanston to get more bang for her buck — that is, a quicker commute for the same price.

“Across Chicagoland and in Evanston, because rent prices are rising so fast, they’re pretty much on par with each other,” Korey says. “It’s expensive across the board.”

Korey adds that the CTA Red Line has been “unreliable” over the past few years, and she worries about her safety where she lives in Rogers Park.

“I don’t walk outside, even in the daytime, just for safety reasons, because there have been a couple of domestic violence disputes and shootings within a two-block radius of my place,” Korey says.

Across Chicagoland and in Evanston, because rent prices are rising so fast, they’re pretty much on par with each other. It’s expensive across the board.

“

While gentri cation accounts for the rising rent prices around Chicago,

Schroeder’s sense of safety is slightly di erent. Her neighborhood, she says, mostly consists of elderly people. She notes that a few graduate students and faculty members live on her block and says the area is “pretty safe.”

For Sonko, however, Northwestern’s institutional presence in Evanston has resulted in an additional layer of police accountability that Rogers Park doesn’t have.

Sonko says as a Black woman, the high racial pro ling in the Rogers Park area has

made her feel unsafe because the police are more willing to intervene forcefully in encounters with Black people in Chicago. On her way towards the Howard Red Line station, Sonko says she has seen multiple police cars stop Black individuals for simple traffic violations.

“If something were to happen to a Black [NU] student, [EPD and NUPD] have someone to answer to,” she says. “Whereas if something happens with a Black person walking on the street, the city of Chicago doesn’t care.”

Halle, who is white and non-binary, also feels uncomfortable with the high, largely unregulated, Chicago police presence. They highlight the Chicago police’s history of targeting visibly transgender individuals for arrests, particularly under the suspicion of sex work, as a key reason for their discomfort.

Still, Halle says that their whiteness helps protect them from forceful police encounters, which is o en targeted at Black residents. In the predominately-white North Side where Halle lives, they say their race helps them blend in.

“I don’t stick out as much and that makes me feel safer,” they say.

Schroeder and Sonko’s apartment has more security than their previous Evanston build. The pair’s sophomore year apartment on Noyes Street periodically had broken locks near the entryway, making the building essentially open to the public, according to Schroeder.

“Our units have these electronic locks on them.”

For some, the quality of housing in Evanston still leaves much to be desired. Medill fourth-year Kalina Pierga lived in Evanston during her sophomore and junior years and encountered a legal issue with her lease in September 2021.

A er nding out that her house on Foster Street contained mold levels above livable limits, she contacted her landlord, but ultimately received no assistance. She and her roommates backed out of their lease and had to nd last-minute living accommodations. The lack of landlord accountability made Pierga feel wary about the conditions of Evanston student housing.

“I think landlords in Evanston are used to naive college kids just picking a place and moving in and not really looking at leases or being picky about

“

health standards,” she says. “I’m sure a lot of other students encountered these situations, and they’re not in a position to have any type of background knowledge of real estate law.”

Pierga now lives at home in Barrington, Illinois, an hour away from campus, which she says has been easier since she will be conducting her Journalism Residency in Philadelphia during Spring Quarter.

A window in Schroeder and Sonko’s Rogers Park apartment unveils a crystal clear view of the Bienen School of Music. Schroeder continues to list her apartment’s amenities: laundry on every oor, a gym in the basement and a double-doored entrance with a part-time security guard.

She walks downstairs and reveals an all-access patio and storage lockers.

In her previous and much-older Noyes Street apartment in Evanston, laundry was in the basement, and a cluster of dead cockroaches occupied a hole in the wall. She says the apartment’s ambient temperature was once in the 50s for two weeks.

I think landlords in Evanston are used to naive college kids just picking a place and moving in and not really looking at leases or being picky about health standards.

“Kalina Pierga, Medill fourth-year

“This entire building very much feels a lot more secure,” Schroeder says.

For Schroeder, the move from Evanston to Rogers Park was worth it. When asked if she knew others who considered leaving Evanston, she says many are interested, but drawbacks like distance o en leave them discouraged.

“It feels like a lot. And I’m not going to say it’s not because there are de nitely times where my car hasn’t started in the morning and I’ve been late because I couldn’t just walk to campus,” she says. “It’s not all pros, but I do think overall, it balances.”

WRITTEN BY AUDREY HETTLEMAN // DESIGNED BY EMMA ESTBERG

WWhen Associated Student Government (ASG) President and Weinberg fourth-year Jason Hegelmeyer rst joined ASG his sophomore spring, he was a senator representing For Members Only (FMO), Northwestern’s premier Black student alliance. That same year, then-Senate speaker Matthew Wiley posted a racist meme in the ASG Slack and made insensitive remarks in a later Senate meeting. A er internal discussions about racism, Wiley eventually resigned and the Senate established a permanent FMO seat.

“That whole shi in ASG ushered in a whole new era of social justice and thinking about the work we do and the students and communities that we impact,” Hegelmeyer says.

ASG has consistently lobbied for e orts to improve the student experience. The Senate, cabinet and committees work with students and administration to enact change on Northwestern’s campus while honing their leadership skills. However, representing a student body of 8,000 undergraduates comes with its challenges, whether it be creating spaces for anyone to voice their opinions or ensuring legislation leads to tangible change once it reaches the administration.

In anticipation of ASG’s presidential elections this coming Spring Quarter, NBN examines the roles and responsibilities of Northwestern student government.

A er his tenure as FMO senator, Hegelmeyer began to consider ASG presidency. His campaign process began early Winter Quarter of 2022, when he picked SESP third-year Donovan Cusick as his running mate and they began reaching out to major campus groups, such as the Black Mentorship Program

(BMP), to gather feedback about what students wanted to see in ASG leadership. By the time the actual campaign began in April, Hegelmeyer says he had a good idea of what platforms were important to students. In BMP’s case, Hegelmeyer says, the group mainly wanted to ensure Black students were supported.

Undergraduate students elect ASG’s president and vice president every spring. The president and vice president then select their cabinet, which includes the executive o cer of justice and inclusion (EOJI) and chief of sta , as well as committee chairs.

ASG’s Senate, the organization’s legislative branch, is led by Speaker and Weinberg third-year Dylan Jost, Parliamentarian SESP third-year Dalia Segal-Miller and Deputy Speaker SESP third-year Leah Ryzenman. They lead school senators, who are elected by their respective school’s student bodies, and

President

Donovan Cusick

student group senators, who apply for seats and are approved by an internal committee. Groups represented this year include Alianza, Residential College Board and Athletics, among others.

Senate leaders and members hold seats for a full year, during which they write and pass legislation. The Senate also serves as part of a system of checks and balances for the Finance Committee, which distributes funds to student organizations and acts as a mouthpiece for students in conversations with administration. Senators o en join one of ASG’s 10 committees, which range in topics such as nance, student life and sustainability and work directly with university administration on short-term and long-term projects.

Jost says the Senate’s primary responsibility is to represent students.

“We’ve really made an e ort to make sure Senators are reaching out,” Jost says. “So having them hold o ce hours, talking to people in their dorms and trying to make sure they’re staying engaged.”

Hegelmeyer recalls his presidential campaign experience being “wildly draining.” He remembers going on YikYak, an anonymous social media app, a er a debate and seeing posts accusing him of being rude and annoying by interrupting and making faces at his opponents. He says he felt he faced a double-standard as a Black candidate, experiencing disproportionate criticism for his debate demeanor. While the experience caused a lot of stress for Hegelmeyer, he says it was eye-opening in terms of seeing how Northwestern treats its marginalized students.

“In the beginning, I really did truly want to support and represent the entire student body as much as I could,” Hegelmeyer says. “But I realized there are plenty of communities that don’t like me or respect me, and that’s perfectly okay. And I don’t have to pretend like our interests are exactly aligned.”

Communication fourth-year Jo Scaletty is also working to improve the experience of marginalized students as EOJI. The role, previously called “Vice President of Justice and Inclusion”, saw frequent turnover, leading to calls for reform in 2019. Scaletty says having someone speci cally working on equity and inclusion makes it more likely marginalized voices will be heard.

“There is much more of a tendency to stay within the status quo than there is to try to progress and realign priorities and work to establish social equality,” Scaletty says. “And so having someone whose speci c role and purpose is to further the ideals of social equality is incredibly important.”

One of Scaletty’s recent initiatives was expanding Books for Cats, a Northwestern program which loans financially eligible students textbooks and lab equipment for certain introductory courses. Scaletty collaborated with the Chair of Academics Brian Whetsell, to expand the program by starting a “lending library,” which allows all students to donate and borrow course books.

One of the most in uential ways ASG impacts student life is through funding. ASG distributes about $1.8 million in funding to student groups every year, which comes from the ASG Activity Fee

in each student’s tuition. Clubs currently obtain ASG funding based on a tier system. The more years a club is at Northwestern, the higher their tier and the more funding they are eligible to receive. Cusick recognizes that this structure prevents new groups from generating community on campus.

“It kind of guarantees that older events are just grandfathered into their money and they can expect it without much question or consideration,” Cusick says.