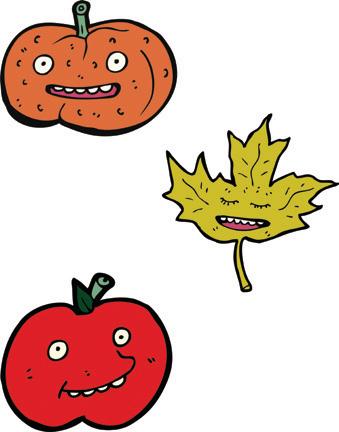

FALL 2023

The year of the girl

In 2023, every night is girls’ night. | pg. 26

Scripts of change

Northwestern students and faculty aim to decolonize classical theater, opera and ballet works. | pg. 40

The year of the girl

In 2023, every night is girls’ night. | pg. 26

Scripts of change

Northwestern students and faculty aim to decolonize classical theater, opera and ballet works. | pg. 40

Northwestern’s marching band builds community and connections. | pg. 51

What is your presidential campaign slogan?

PRINT MANAGING EDITOR Jenna Anderson

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Julianna Zitron

EDITORS-AT-LARGE Jimmy He, Mia Walvoord

SENIOR FEATURES EDITORS Emma Chiu, Noah Coyle, Christine Mao, Caroline Neal

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITORS

Courtney Kim, Shae Lake

SENIOR DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Audrey Hettleman, Katie Keil, Maya Krainc, Ava Mandoli

ASSISTANT DANCE FLOOR EDITORS

Sarah Lonser, Mitra Nourbakhsh

SENIOR PREGAME EDITORS Hannah Cole, Sarah Lin, Anavi Prakash

ASSISTANT PREGAME EDITOR Indra Dalaisaikhan

SENIOR HANGOVER EDITORS

Julia Lucas, Natalia Zadeh

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Iliana Garner

ASSISTANT CREATIVE DIRECTOR Grace Chang

DESIGNERS & ILLUSTRATORS Michelle Sheen, Jackson Spenner, Allison Kim, Allen Zhang, Sammi Li, Laura Horne, Michelle Hwang, Valerie Chu, Elisa Taylor, Abigail Lev, Olivia Abeyta, Jessica Chen

PHOTOGRAPHERS Taylor Hancock, Lavanya Subramanian, Ashley Xue, Valerie Chu, Elisa Taylor, Alessandra Esquivel

Sophia Vlahakis, Lindsey Byman, Olivia Abeyta, Cammi Tirico, Ashley Wong, Jerry Wu

COVER DESIGN BY ILIANA GARNER

COVER PHOTO BY VALERIE CHU AND ASHLEY XUE

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kim Jao

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Christine Mao

MANAGING EDITORS Astry Rodriguez, Conner Dejecacion

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITORS

Olivia Abeyta, Arden Anderson, Jaharia Knowles

DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION EDITORS

Sammi Li, Astry Rodriguez

NEWS EDITOR Joanna Hou

POLITICS EDITOR Gideon Pardo

ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR Kelly Rappaport

LIFE & STYLE EDITOR Chloe Que

SPORTS EDITOR AJ Anderson

ASSISTANT EDITOR Maggie Rose Baron

INTERACTIVES EDITOR Manu Deva

FEATURES EDITORS Sara Xu, Ava Hoeschler

OPINION EDITOR Mya Copeland

ASSISTANT EDITOR Hannah Zhou

CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Amaya Mikolic-Berrios

AUDIO & VIDEO EDITOR Sammi Li

PHOTO EDITOR Lianna Amoruso

GRAPHICS EDITOR Iliana Garner

INSTAGRAM EDITORS Sara Xu, Kim Jao

TIKTOK EDITOR Lianna Amoruso

TWITTER EDITOR Jade Thomas

PUBLISHERS Julianne Sun and Stephanie Kontopanos

AD SALES TEAM Grace Chang and Janice Seong

MARKETING TEAM Sam Stevens

WEBMASTER Ziye Wang

When the football scandal broke this summer, I was shocked, saddened and embarrassed. A er reading The Daily’s admirable reporting, I knew NBN had to nd a way to cover the issue in our fall edition and capture the melancholic feelings of the student body. Our answer is the uno cial theme of this magazine: Varsity Blues.

You’ll notice cool tones dominate this issue. The pops of warm colors at the beginning of the magazine gradually fade out until all color disappears in the black-and-white cover of our photo story, “Banding together,” a feature on the Northwestern University Marching Band. We highlight this o en overlooked group and ask how it feels to be cheering for a team that experienced such a dark episode. The band’s thoughts on who they truly root for may surprise you.

We also take a look at the football team’s history in a Dance Floor story, “Purple reign.” Using Northwestern archives, the piece shows just how many times the team has bounced back in their 141 seasons. You’ll read about the many moments when the student body rallied around the team, especially at their low points.

And we found plenty of other things to celebrate this fall. In our Pregame section, we upli Mariachi Northwestern, still on a high from their performance at this summer’s Lollapalooza. Our Dance Floor section documents an increase in campus- and city-wide access to Narcan, the lifesaving medication for opioid overdoses. And have fun lling out the games page in the Hangover section!

Warm colors nally return to the magazine in that nal section, a re ection of Northwestern’s continued e orts to heal from the negativity surrounding the football scandal. For me, this sta of editors, designers and writers was a source of solace and community this fall. I couldn’t be more grateful for their talent and dedication to NBN. My hope, dear readers, is you’ll nish reading this magazine with the feeling that, even in our darkest moments, we can turn to one another and nd something to cheer for.

Sincerely,

Jenna Anderson

Pho-nomenal!

Resonating roots

After (office) hours with Professor Tan

Grow ‘Cats!

Backstage bosses

5, 6, 7, 8!

Writing (and rewriting) history

The road to education equity

Gray area

The year of the girl

Purple reign

Over the counter and onto campus

The fitness journey

Scripts of change

Blending cultures, forging identities

Banding together

Spill the broth

Op-ed: What am I to do without my campus celebrities?

Serving (the Evanston people) 101

Hometown how-tos

Kids menu

7 8 10 11 12

Phonominal!

Resonating roots

After (office) hours with Professor Tan

Grow ‘Cats!

Backstage bosses

We tried the Big Bowl Special Beef Pho at Joy Yee. It’s pho-king delicious.

WRITTEN BY SARAH LIN // DESIGNED BY ALLISON KIM // PHOTOS BY ASHLEY XUE

Sometimes, all you want is a comforting bowl of soup. Rich, tangy, savory, meaty and fragrant, Joy Yee’s Big Bowl Special Beef Pho is sure to satisfy your cravings. But be warned: It lives up to its name

This fall, four NBN sta members traveled to Joy Yee with big hopes and even bigger appetites. Our goal? To nd the bottom of the bowl.

Priced at $29.95, the pho is a symphony of ingredients, including beef broth, rice

extends to America, where food outlets like the Michelin Guide have released rankings of the best pho in the U.S.

Joy Yee’s large serving is also re ective of Vietnam’s culture of sharing food. Meals are o en served family style as opposed to individual portions. According to the Hanoi Times, even the country’s choice utensil of chopsticks signi es “community solidarity” as they are used to “pick food up and give to others.”

As we chowed down, we observed a couple of things: Hannah found the soup especially “comforting,” Indra noted the “slight sweetness” of the beef broth and Ashley welcomed the bean sprouts’ crunchy contrast to the so noodles and meat. We all agreed the pho tasted

nish all the noodles, meat and vegetables but were unable to consume all of the broth. This may have been because the broth was incredibly rich, so we struggled to polish it without the other ingredients avor.

We measured our progress through the smaller bowls we scooped the Big Bowl Pho into. Ashley devoured two and a half, Hannah demolished three, I slurped up three and a half and Indra wolfed down four whole bowls (our MVP!) for a total of 12 small bowls.

As the days grow colder, Joy Yee’s Big Bowl Pho is not only a great way to warm up but also a chance to share food and conversation with friends. Reminiscent of a Vietnamese-style family meal, the “challenge” of nishing the pho, soup and all, is guaranteed fun.

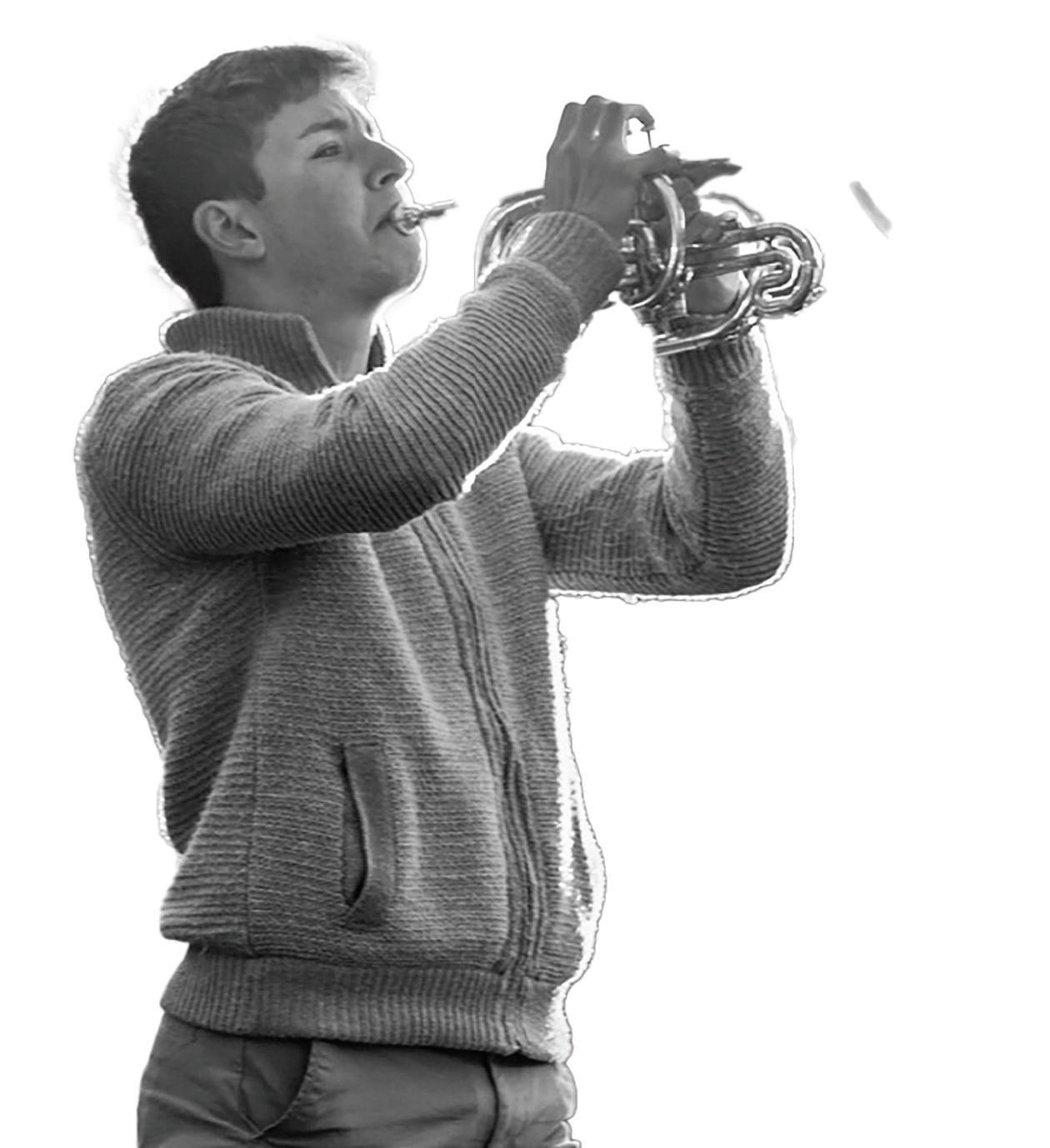

was more comfortable to place a cultural element on. I wanted to nd some form of cultural singing on campus, and because [Mariachi Northwestern] met all the criteria, I joined it,” Schuch says. “It is also a way to reclaim your heritage. It feels most real when I put on the traje.”

Schuch grew up watching folklórico dances to mariachi music with her paternal grandma. Her maternal grandma had always wanted to be a mariachi performer, so when her family came to see her perform at the spring rehearsal, she was overcome with emotion.

“I almost cried on stage when I saw my grandparents and my mom because I know they never had the opportunity to [perform mariachi],” she says. “They were just so happy I did it for them, and it was the rst time they got to see me.”

The band meets every week for a onehour rehearsal session. They also have optional jam sessions throughout the week. The band spends these get-togethers going through their repertoire, learning new music and revisiting old music.

The group’s e orts culminated in August with a performance at Lollapalooza, an annual four-day music festival in Chicago. Latin pop singer Lesly Reynaga invited the

“Mariachi music is about fighting to be heard.”

band to perform during her set.

“When they invite us to things like big academic conferences or when we get invited to Lollapalooza, it puts mariachi music in the limelight and [highlights] the beauty of Mexican culture,” Reyna says.

Before performances, the ensemble will sometimes guide the audience through song lyrics or release an erupting wave of laughter or yell, known as the grito, to gauge the crowd’s attention. The band always looks forward to the reactions they get from the audience.

“We want the audience to dance along. We want the audience to be involved in the music,” says Weinberg secondyear Sebastian Gomez, the band’s trumpet player.

Even now, Lizet Alba, a Class of 2016 alumna who resides in the Chicago suburbs, is reminded of her heritage and ties to the Northwestern community whenever she hears the band perform. She has seen nearly a dozen performances.

“When I hear Mariachi Northwestern play, it is a great connection to where my parents are from, the country I consider home,” she says. “Mariachi is representative of Mexican culture but different narratives come to fruition with each song.”

As Mariachi Northwestern continues to build its musical repertoire and increase its number of performances, it aims to reach new audiences and bring Latine culture to life.

“I’m Mexican, and I grew up with mariachi music. It’s important to me to hear that music be put into places of prestige,” Reyna said. “It’s also exciting for me to see the things that I grew up with being appreciated by Mexicans and also non-Mexicans.”

In essence, the lasting impact Mariachi Northwestern has had on campus comes down to its members. From putting on week-in and week-out gigs to spending hours in rehearsal, the band fully embodies the values and narratives commemorated by timeless mariachi.

“It’s music that comes from the heart. The most ful lling thing I enjoy while I am playing [mariachi music] is that I can see the audience smiling,” Gomez says.

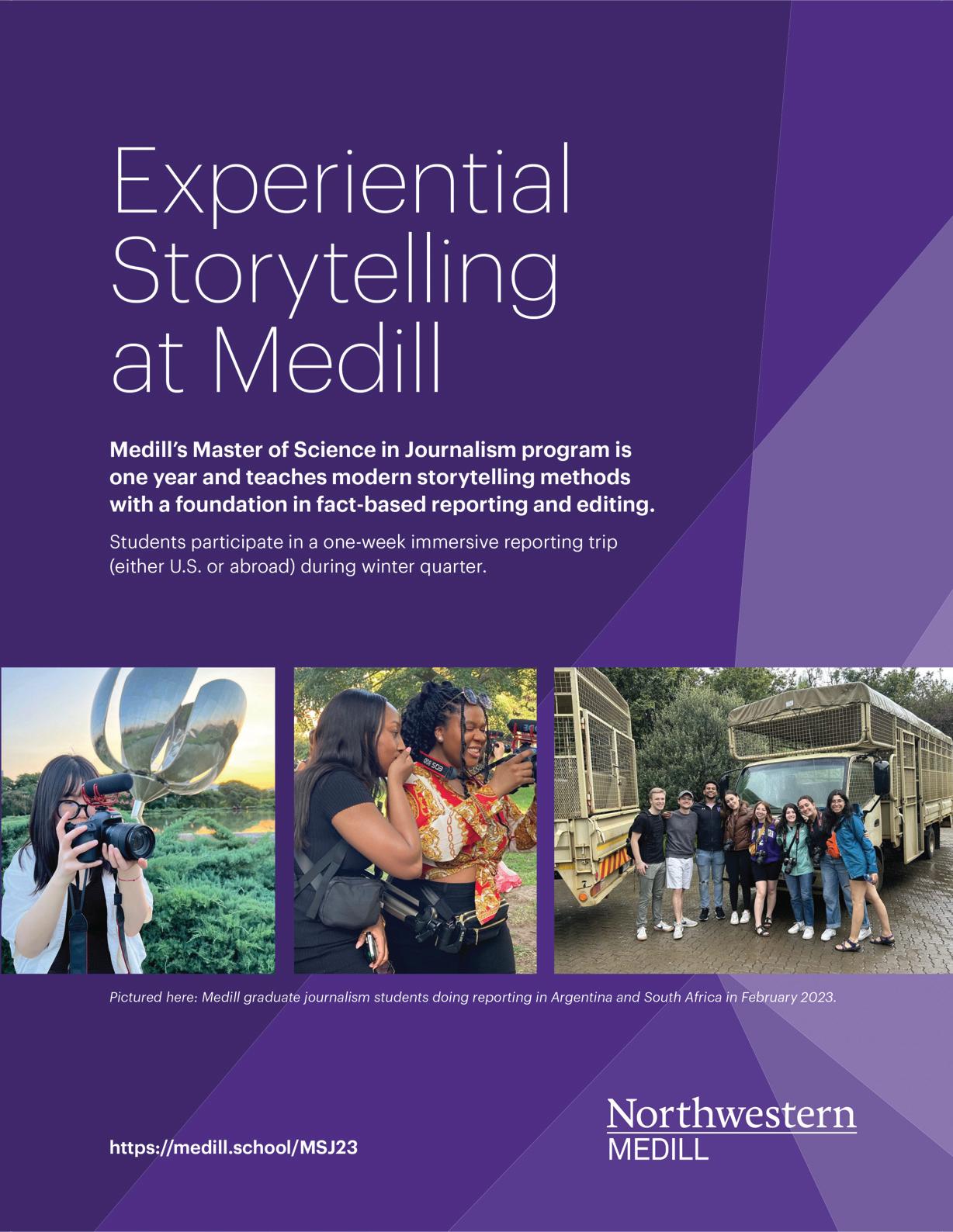

A conversation with the inaugural George R.R. Martin Chair in Storytelling, one of Medill’s newest professors.

WRITTEN BY ASHLEY WONG // DESIGNED BY SAMMI LI

PHOTO BY TAYLOR HANCOCK

n April 2023, Northwestern University awarded journalism professor Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan (Medill ’97) the inaugural George R.R. Martin Chair in Storytelling at Medill.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

NBN: Congratulations on your new professorship! Can you tell us about what your role as George R.R. Martin Chair entails?

Tan: I will be mainly creating the George R.R. Martin Summer Intensive Writing Workshop that will help mid-career journalists transition into writing ction, lm, TV or plays.

The idea is that journalists out there are already such good storytellers in the world of journalism. A lot of them probably have good ideas that can be amazing books, TV shows and screenplays. We want to help them transition into ction writing.

NBN: There seems to be quite an intersection between journalism and creative writing. How does your background in both ction writing and journalism in uence your storytelling?

Tan: I keep the two very separate when it comes to journalism because journalism has to be real; it can’t be ction. But when it comes to ction, I feel like my most compelling work actually comes out of non ction or journalism.

NBN: How has your transition been, from being a professional writer to now becoming a professor?

Tan: I’m still learning! While I wrote professionally, I always wondered how I was going to teach something I learned very instinctively. I’ve never really learned the cra of ction — I took one creative writing class in my life, at Northwestern — but my whole career I’ve pretty much been: Let’s just gure out how to do it, and then I’ll do it.

A lot of it has still been guring it out and really learning from the students as much as I hope they’re learning from me. Medill is the place where I felt like I grew up both as a writer and as a person. The idea of having a role in helping nurture the great minds of the future is very exciting to me.

NBN: Just like myself, you were an international student from Singapore trying to carve out your career in America. What kind of advice would you give to fellow international students trying to make it in the media profession in a new place?

Tan: Pitch as many stories as you can. Write as much as you can. An editor told me once, the more you write, the more you will write. Good clips and good ideas will get you everywhere in the world. Put yourself out there.

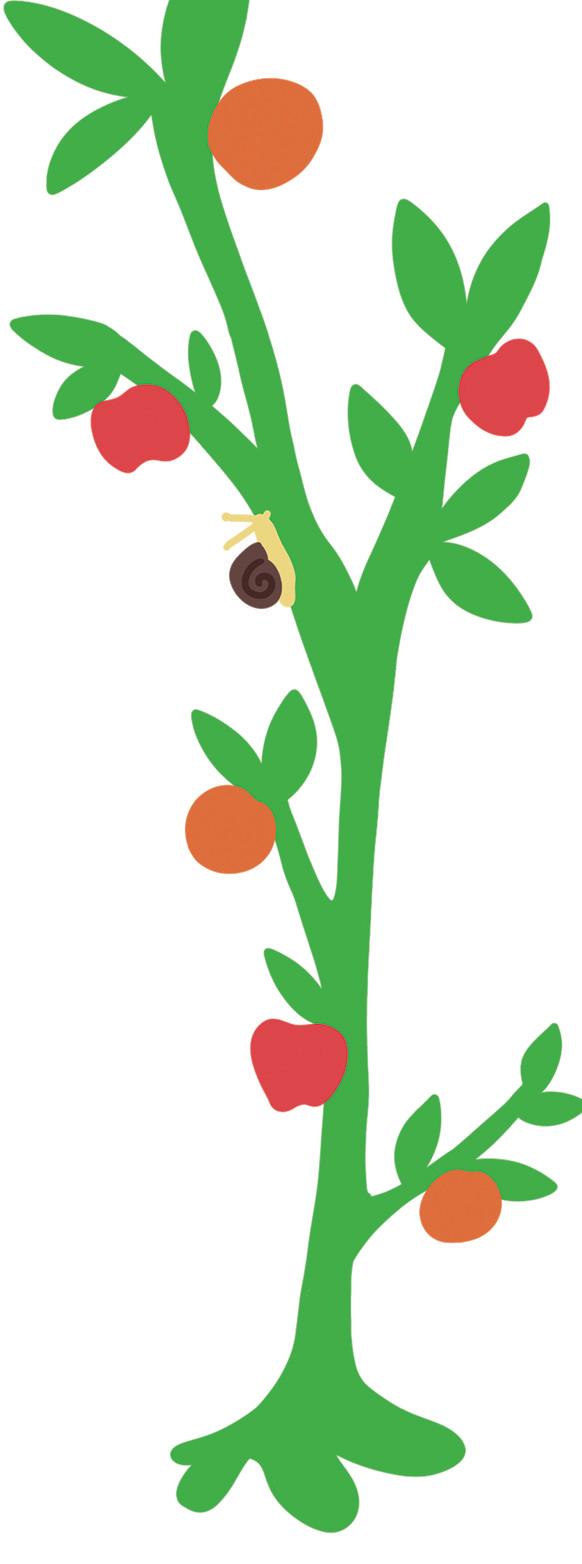

South Area’s “Garden of Eatin’” provides fresh produce for Northwestern students facing food insecurity.

WRITTEN

DESIGNED

BY

BY

CAMMI TIRICO AND SARAH LIN

ILIANA GARNER AND JULIE PARK

Nestled within the heart of South Campus, four planter boxes feed Northwestern University’s foodinsecure students. The 6 by 4 foot woodenframed garden beds over ow with tomatoes on 3-foot vines, purple owers and an abundance of other fresh produce.

Every Thursday, a group of students, community members and volunteers harvest the beds and bring the produce to Purple Pantry, a free food pantry located in 1835 Hinman. The weekly harvest depends on the season and conditions, but in the rst week of October, the garden yielded 15 bags of fresh tomatoes, kale, swiss chard, cucumbers, herbs, sweet peppers and hot peppers.

“International students don’t qualify for [federal] nancial aid, which means they can’t qualify for SNAP and EBT or food stamps,” SESP fourth-year Lily Ng says. “So that means they rely heavily on the food pantry. Having hot peppers, something they use within their cuisines, has been really nice for them.”

According to the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, one in three college students in the U.S. face some form of food insecurity. The idea for the garden grew from a desire to connect the Evanston and Northwestern communities and to make fresh fruits and vegetables more accessible on Northwestern’s campus, Ng explains.

A group of students, including Ng, spent the 2022-23 school year planning the South Area community garden for their Civic Engagement Certi cate capstone project. The greatest challenge they faced was nding a location to host the garden, Ng says.

A er receiving multiple rejections from Northwestern administration, Ng says she

contacted Reverend Julie Windsor Mitchell from the University Christian Ministry (UCM) and Professor Ava Thompson Greenwell, the faculty-in-residence for the South Area. In collaboration with Evanston Grows, an organization dedicated to reducing food insecurity in Evanston through locally-grown produce, UCM provided a plot of land for the garden. In late May 2023, Evanston Grows, Ng and over 30 volunteers o garden and planted their

The South Area community garden is not the rst project UCM has worked on to help eradicate food insecurity. In 2015, UCM worked alongside other campus ministries to found and run Purple Pantry until 2022, when Northwestern Dining assumed control of the food pantry.

“We really are trying very hard to put what I call ‘feet to faith’ — actually live our faith and live out our commitment to ecojustice,” Mitchell says.

The group will plant garlic this winter, and the rest of the garden will be “put to bed” until spring. In the season-closing event, South Area students revealed the garden’s o cial name: the Garden of Eatin’. When the garden reopens in the spring, those involved say they are looking forward to seeing what the new season will bring.

“I discovered how being close to the soil and out in the sun are all important things,” Greenwell says. “To actually be able to get out and see something that starts as almost nothing, a seed, and see it become something. The wonders of life are still simple, yet complex.”

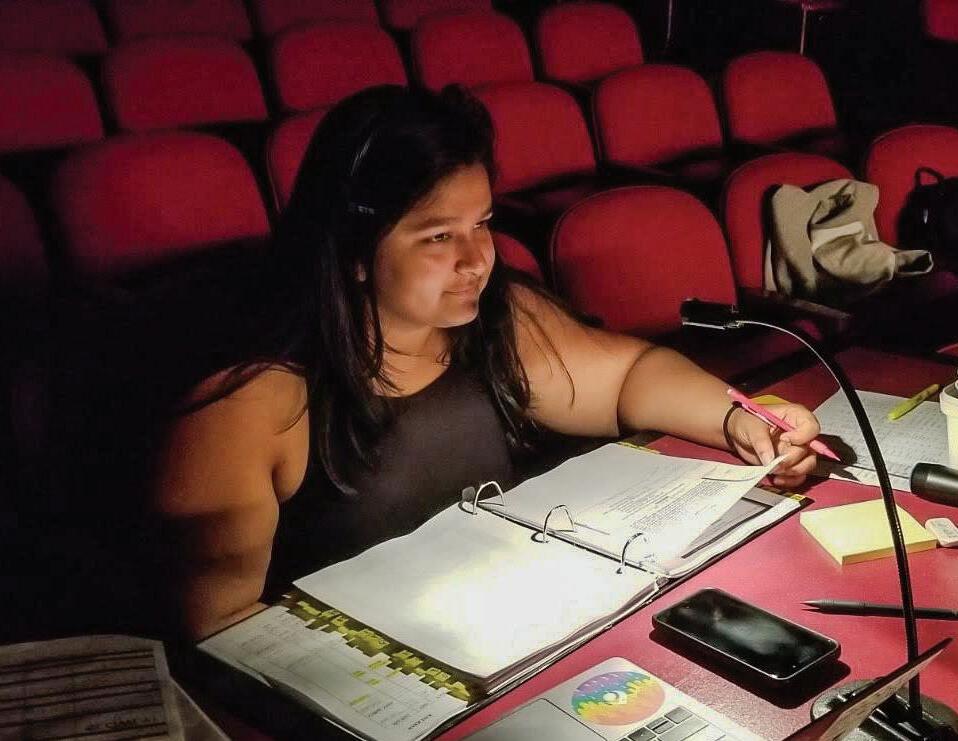

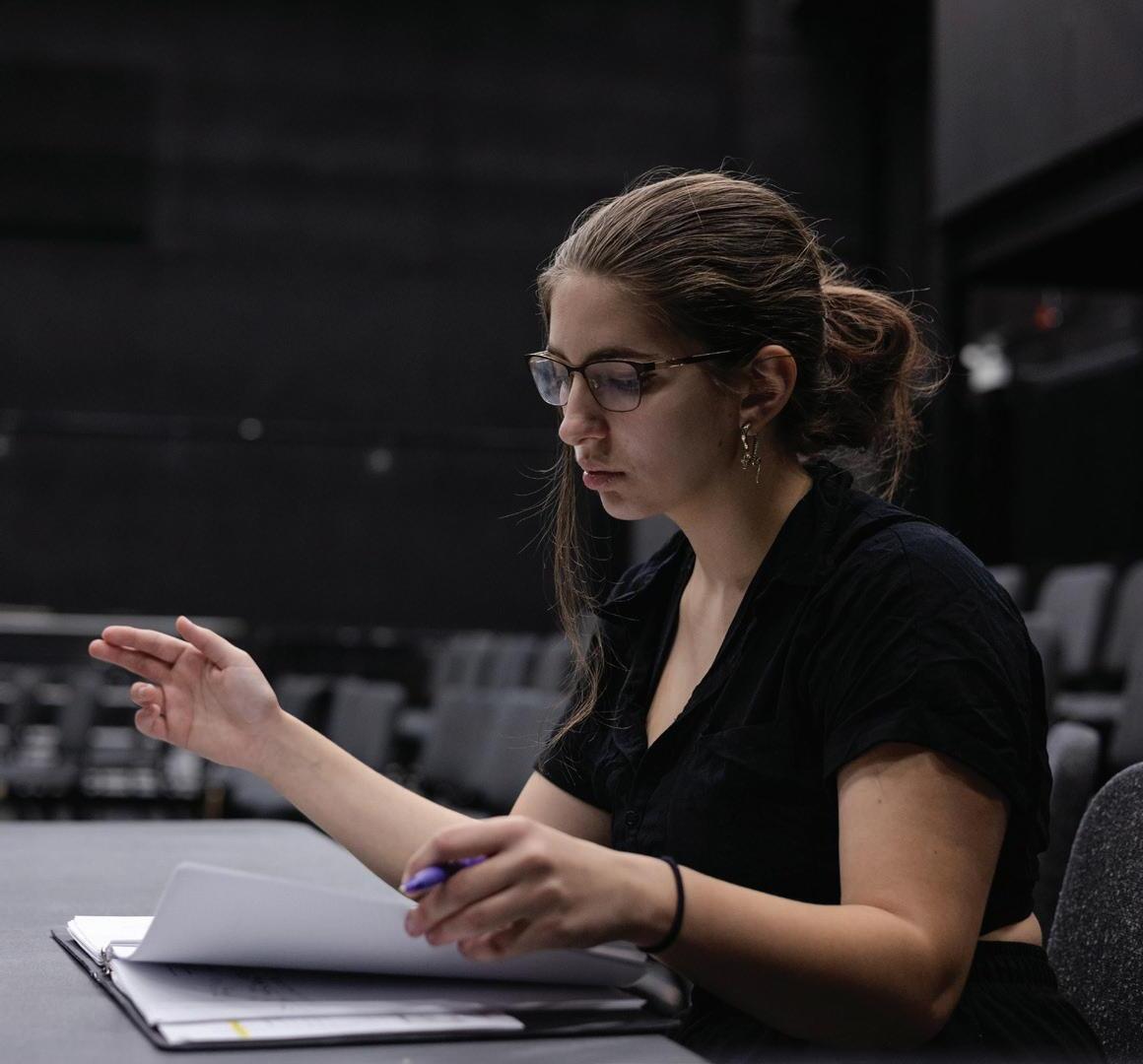

Come behind the scenes with three Northwestern stage managers.

WRITTEN BY ANAVI PRAKASH

DESIGNED BY ABIGAIL LEV

PHOTOS BY ALESSANDRA ESQUIVEL

With one hand holding her blue Stanley cup and the other ready to give directions, Communication third-year Anushka Agarwala makes her rounds through Shanley Pavilion while simultaneously directing mic check. Occasionally, the theatre major is heard yelling about water bottles being le on the stage.

Then, when everyone is in their places, it’s showtime.

All her preparatory work comes to the forefront now. It’s time for Agarwala to stage manage a production of Once On This Island, a musical loosely based on a

Caribbean-set retelling of The Little Mermaid called My Love, My Love or The Peasant Girl by Rosa Guy. In her role as stage manager, Agarwala has spent hours coordinating the cues she will give her team during the show, ensuring it runs smoothly.

Stage managers connect the creative and technical sides of a production, making sure everyone is on the same page and the cast and technical crew know their cues for the show. Agarwala calls her role “omnipresent.”

“You really are always there,” she says. “The stage manager is always there in every room, always watching, giving notes and just taking information.”

Agarwala

Communication second-year Wylde Laden and Weinberg second-year Sophia Mitton-Fry, co-stage managers of last spring’s production of The Thing About The Dream, echo this sentiment and believe stage managing is all about communication.

“Being the bridge between people is the most important part,” Laden says.

Cues for the show come together in the stage managers’ scripts, which also include information on where the actors are at all times and notes from the designers and the director. In short, it has everything they need to make the show happen.

Beyond her script, one of Agarwala’s main aspirations as stage manager is to create a collaborative and inclusive environment for the cast and crew. Over time, she has found that open communication and team building activities are key to achieving her goal.

“If the cast ever had any issues or anything, [I made] sure they knew they could communicate that with me and we would try to solve the issues immediately,” Agarwala says.

She describes her relationship with the Once On This Island cast as “close.”

“Some of the actors, they do things before I ask them to because they’ve been asked to do them so many times,” Agarwala says. “It’s more of a gelled relationship.”

With the crew, it’s a bit di erent. Most of the crew members are Agarwala’s friends outside of the theater.

“It’s a little bit tricky because you’re in a power position of authority over your friends and classmates,” she says. “But this group is really good because they all

have a level of respect for me, and they know I’m trying to move the show along.”

For most shows, the rst time the entire crew comes together is during tech week, a week full of dress rehearsals. In the midst of putting all the pieces of the show together, Laden’s utmost goal is to create a positive environment.

“I try to make the room as fun as possible during tech week because I know it’s a lot of stress a lot of the time,” she says.

She adds that tech week is her favorite part of the show process.

“Once we get to tech week, it becomes my room,” Laden says.

For Mitton-Fry, the majority of her time before tech week is spent thinking about tech week. She counts down the days until full run-throughs begin to determine what needs to get done beforehand.

Prior to tech week, a lot of what stage managers do involves keeping everyone accountable and on the same page. Laden writes “frantic” notes and creates templates she can ll out to communicate logistical and show-speci c information to her cast and crew in the most e cient way. Mitton-Fry creates a Google Drive folder to store the vast amount of information given to her.

Though this process is “crazy,” MittonFry says she loves stage managing because she gets to meet people who are equally passionate about the work they are doing.

“I like the energy of it,” she says.

Laden loves the new things she learns.

The Thing About The Dream was a unique experience for her because she had to cue off of Bollywood songs even though she didn’t know how to speak Hindi.

For Agarwala, Once On This Island is a special show for two reasons.

“The music is joyful, it’s colorful,” she says. “There are some heavy topics obviously, but overall, it’s a celebration of love and life, so I’m excited for everyone to witness that and see the love and passion all of us have put into the show.”

When the lights dim at the top of the show, Agarwala sits at an elevated table, next to the show’s lighting designer.

As soon as the opening number, “We Dance,” starts, Agarwala is dancing, mouthing the words as the cast sings them. She follows along, performing on the sidelines for the entire show.

Another reason the show is important

“The stage manager is always there in every room, always watching, giving notes and just taking”

Anushka Agarwala Communication third-year

for Agarwala is because it was one of the first Northwestern shows with a cast made up entirely of people of color.

That diversity was part of the reason why Agarwala prioritized creating an inclusive, safe environment.

“[I wanted an] atmosphere where we can express ourselves and our di erent identities and cultures in a way that is safe and collaborative,” she says.

Agarwala says this show is important because theater, including at Northwestern, has been a historically white industry.

“It’s very possible in the future, or even now, to do shows that are full POC team and cast and everything,” she says. “These stories don’t have to just be in the professional world because they have the resources and the people to do it. It’s very much within our realm on campus.”

Her faith in theater’s future at Northwestern stems from her passion for theater and stage management.

“I found my niche,” Agarwala says.

Three

The world is a muse for choreographers. Inspiration for a routine begins as an impossible party idea, music from a video game or a song’s gripping plot. In the process of cra ing and reworking sequences, teaching dancers and making edits, a moment’s vision becomes a performance. For student choreographers Alexandra Romo, Amanda De la Fuente and Mary Kate Tanselle, hours of work culminate in just a few minutes as their dancers leave it all on the stage.

WRITTEN BY LINDSEY BYMAN

DESIGNED BY LAURA

HORNE

PHOTOS BY ALESSANDRA ESQUIVEL

expensive. So Romo mixed the music and choreographed the dance herself, complete with a custom-made holographic jumpsuit and prop umbrellas.

“I was like, ‘If I have the vision already, what if I just do it?’” Romo says.

Later in high school, she would choreograph and mix music for other people’s quinceñera dances. She also choreographed and performed Latin dances at high school talent shows.

Multiple DJs and choreographers told Communication fourth-year Alexandra Romo they didn’t know how to produce the 10-minute, “Back in Time”themed performance she planned for her quinceñera — or if they did, it was too

Now, as co-head choreographer for Northwestern Latin dance group Dale Duro, Romo’s routines play on song lyrics. When Bad Bunny sang, “Let’s take a sel e,” during the group’s performance of his song “Tití Me Preguntó,” Romo and her dancers did just that. She also researches formations to choreograph “the type of dance that will get you tired.”

Romo began dancing hip-hop when she was 8 years old and later got into Latin dance. She says she tried Mexican folklórico dance when she was 13 and liked it so much she continued practicing it until she le for college.

Romo missed registration for Dale Duro her rst year at Northwestern but jumped in the following year as a choreographer, excited to nd a space that combined her Latin identity and passion for dancing.

“I’m a senior already, but at least I’m grateful,” she says. “I was part of something bigger.”

At the Latino Alumni Homecoming Tailgate, she performed an upbeat hiphop-style Latin dance with Dale Duro. Smiling at the crowd in pigtails and a purple skirt, she commanded center stage for much of the routine.

This spring, for one of her nal performances with the group, Romo is incorporating more Mexican dance styles. Her ideas have been coming together since last year a er the crowd screamed

in excitement for her dance at Dale Duro’s annual spring showcase. The dance included zapateado, a Mexican dance style named a er dancers tapping their shoes against the ground.

“Everybody loved it. And then they were like, ‘Oh my god, what is that?’” Romo says.

When Communication third-year Amanda

De la Fuente rst heard the theme from “The Last of Us,” she saw its black and gray melody woven with deep green in her head. She has synesthesia, a condition where sensory information goes through multiple brain pathways, allowing individuals to experience multiple senses at once. In De la Fuente’s case, this means she sees colors when listening to music.

‘“I’ll listen to music and I’ll be like, ‘That’s yellow,’” she says.

This year’s Fall Dance Concert, hosted by the New Movement Project, nally gave De la Fuente a chance to translate the song’s colors to movement. Her dance and musical theater choreography, which draws on contemporary, modern, jazz and ballet dance styles, is unique in its storytelling. She says her theater experience fuels this interest.

In her routine, ve dancers wearing large black dresses perform staccato motions until they individually break into uid sequences, removing their layers to reveal saturated cool tones with one person in purple, two in green and two in blue.

“Trust yourself. I trust you. And if we crash and burn, we crash and burn, and that’s OK. ”

Amanda De la Fuente Communication third-year

“Don’t let society dictate what you want to be,” De la Fuente says of the message she tried to convey through the dance.

Scrolling through her camera roll, De la Fuente says she records herself while cra ing a routine to remember the moves. She also likes to bounce ideas o others, like her friend Angel Jordan, a Medill third-year with whom she founded Eight Counts Ballet Company in 2021.

When teaching, De la Fuente encourages trial and error. This relieves anxiety when she forgets what comes next, which she says can happen because of her ADHD.

“Wanna crash and burn, try it out?” she asks her dancers at rehearsal.

Demonstrating the routine, she instructs them to keep energy in their arms “as if there’s magic coming out of [their] ngers.”

De la Fuente’s choreography career began her junior year of high school when she went on a run and ended up improvising a dance to “A Friend Like Me” from Aladdin in a parking lot. About a year later, she nished choreographing the song and played a video of herself doing it at a senior showcase.

“It was my little pride and joy,” she says.

Her favorite aspect of choreographing is the final run-through in rehearsal, when she tells the dancers to give it their all.

A er the nishing sequence, De la Fuente claps and jumps, kicking her feet behind her with a smile.

“I love telling people, ‘Trust yourself. I trust you. And if we crash and burn, we crash and burn, and that’s OK,’” she says.

For Weinberg second-year Mary Kate Tanselle, a typical Sunday begins at her organic chemistry study group and ends with rehearsal for Tonik Tap, Northwestern’s only tap dance group, where she is a member and company manager.

“It always feels like I get to use every part of my brain,” Tanselle says.

She began tap dancing at 3 years old. In high school, she o en stepped in to choreograph musical theater productions, but a Tonik Tap performance to Mac Miller’s “The Spins” last spring was her rst college experience choreographing tap.

along with a musical shi . She says she loves the lightbulb moments when she has an idea for a routine.

Tanselle typically choreographs multiple versions of a dance and takes feedback from dancers throughout the process.

“You’re never really done,” she says. “But that’s just like anything artistic, right?”

“You let each person have their own interpretation of whatever the emotion or movement you’re doing is.”

Another feature of Tanselle’s style is breaking the fourth wall, the invisible divide between performers and the audience. Last spring, she did this by having her dancers mouth along to Mac Miller’s ad-libs in “The Spins.”

“Everybody could do something di erent with the same song and the same set of dancers.”

Mary Kate Tanselle Weinberg second-year

In the routine, the dancers dressed in Rugrats-esque costumes that t tropes such as nerds and jocks. She says she initially worried if the dancers would like it, but Tonik’s supportive members were receptive to her idea.

Since she’s new to choreography, Tanselle says she takes her time. One performance lasting around three minutes could take her up to seven hours to choreograph, not including the time she spends teaching it to the dancers.

Playing the music on repeat on her way to class, she visualizes one dancer becoming an ensemble tapping in unison

She adds that she still thinks of changes she’d make to “The Spins” performance.

Tanselle is currently co-choreographing a dance to Macklemore’s “Thri Shop.” Dancers will wear di erent funny coats and sunglasses as they tap. But she has cra ed moodier numbers as well, including one to Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” for Northwestern’s Steam Heat Dance Company last year.

She says she enjoys choreographing arm movements and facial expressions to add interest to her piece.

“You get a lot of magic out of people if you give general guidelines,” she says.

She says this keeps the audience thinking about her piece when it’s over, but no two choreographers have the same approach.

“Everybody could do something di erent with the same song and the same set of dancers,” she says. “It’s what makes dance an art form.”

Cody Keenan wrote speeches for President Obama. Now, the professor is training the next generation of speechwriters.

WRITTEN BY JULIANNA ZITRON // DESIGNED BY VALERIE CHU // PHOTO BY ALESSANDRA ESQUIVEL

On the 50th anniversary of the civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, then-President Barack Obama addressed the nation: “We honor those who walked so we could run. We must run so our children soar. And we will not grow weary.” Peers and renowned publications alike would hail the speech as one of Obama’s best.

Two nights before the landmark anniversary, a severe snowstorm shut down the federal government. While most government employees took the day o , then-Chief of Speechwriting Cody Keenan took the opportunity to collaborate one-on-one with the former president. The pair passed ve dra s of the speech back and forth over two days, each dra better than the one before.

“We had never ever been able to do that before because the job is just so busy. We never were able to do it again,” Keenan says.

Keenan served as a speechwriter for the Obama campaign and administration beginning in 2007. Today, he is a Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Political Science department where he teaches the art of speechwriting through his course, “Professional Linkage Seminar: Speechwriting.”

Before he wrote speeches for the nation, Keenan was a Wildcat.

He graduated in 2002 with a degree in Political Science and a minor in Hispanic Studies, now Latina and Latino Studies.

A er graduation, he realized a life in politics is not as glamorous as The West Wing. He spent months searching for jobs before landing an internship with Senator Ted Kennedy’s team. Keenan cites this as the best educational experience he’s ever had. A er his internship ended, Keenan was hired as a sta assistant and promoted three times within the team.

In 2004, Keenan attended the Democratic National Convention where he heard then-Illinois Senator Barack Obama deliver a speech for the

rst time. He was “trans xed” by Obama’s words. Keenan wrote his rst speech for Kennedy soon a er.

His rst project was a Senate oor speech. Even though such addresses are commonly given to a nearly-empty chamber, Keenan says watching Kennedy read his words was electrifying.

“It’s like if you’re Eddie Van Halen and somebody handed you your first guitar,” Keenan says. “You’re like, ‘I want more of this.’”

When Obama announced his presidential candidacy in 2007, Keenan knew he wanted to be a part of the campaign. He connected with Obama’s speechwriter, Jon Favreau, who hired him as an intern.

Two years later, Obama was in o ce and Keenan was still writing with Favreau. In December 2009, the President was supposed to go to Pennsylvania to deliver a speech on the economy that Keenan had written. That morning, Keenan ew on Marine One for the rst time, but he couldn’t enjoy his ight.

The night before, Keenan learned the President didn’t like the speech. He spent the entire plane ride frantically rewriting. Keenan recalled the terror he felt in that moment, wondering if he would lose his job.

“There’s no time for apologizing. There’s no time for training,” he says. “They can nd another speechwriter for the White House very quickly if you can’t cut it.”

Despite having to rewrite the entire speech on the y, Keenan cites this moment of panic as one of his greatest learning experiences.

Even a er two years with the President, writing a speech for someone else to deliver proved to be a challenge. He explains writing for another person requires considerable face-to-face interaction to develop a “mind meld” with the speaker, but Keenan didn’t get much face time with Obama until he was promoted to deputy director in 2011. Before that, Keenan relied on Obama’s past speeches, books and the types of edits made to his speeches.

“You’re not just writing what you think they want to say, you need to gure out why they want to say it,” Keenan says.

This lesson proved true for Keenan years later. One of President Obama’s more renowned speeches is a eulogy he gave for Reverend Clementa Pinckney. In this 2015 speech, the President sang “Amazing Grace” to the audience.

Though he had been working with the President for eight years, Keenan’s version of the speech was not read aloud that day. The President rewrote the back half of the speech. Keenan cites this as the only time he apologized for a speech not meeting the President’s standards. But he admits Obama’s edits made the speech “better” and “beautiful” as the President included reflections on grace and racial bias in America.

“He put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Brother, we’re collaborators. You gave me the scaffolding I needed to build something here. You’ll recognize your work in what I wrote. And trust me, when you’ve been thinking about this stuff for 40 years, you’ll know what you want to say, too,’” Keenan says.

Two presidential terms later, in 2023, Keenan still writes speeches as a partner at the speechwriting Favreau. He also makes a weekly plane commute to Northwestern to teach his course on the art of speechwriting.

“Let me put it this way: I live a 15-minute walk from NYU. I commute to Chicago every Monday to teach at Northwestern. I love it here,” he says.

Keenan’s dedication does not go unnoticed by his students.

Darby Hopper (Medill ’19), who was his student in 2018, re ected fondly on working with Professor Keenan.

“He continues to y to campus every week for this class just because he thinks this is so important,” she says. “That shows how he teaches the class and how he continues to be a resource for former students.”

“You’re not just writing what you think they want to say, you need to figure out why they want to say it.”

Cody Keenan Political Science Professor

A er graduating,

The class is unlike others in the Political Science department because it focuses less on political theory or rhetoric and instead is geared toward practical experience. Students leave the class with a portfolio of 10 di erent speeches, ranging from a eulogy to a State of the Union Address.

“I wouldn’t say my time in politics has passed, but I did have my time,” Keenan says. “Now I get to train a new group of speechwriters every year and send them out into the world until ultimately, ideally, all of politics is sta ed with my kids.”

Whether writing speeches for a president, a governor or a class project, a speechwriter’s work is not nished until the presenter is at the podium reading it aloud. As stressful as it may be, Keenan enjoys the challenge of writing speeches. He acknowledges no one is a perfect writer — it’s collaboration and revision that ultimately make a speech great.

“By the end, you get this piece of sheet music and you get to conduct the audience with those words,” Keenan says. “You can make people nod, you can make people cheer, you can make people cry. It’s a really extraordinary gi to be able to write for a live audience.”

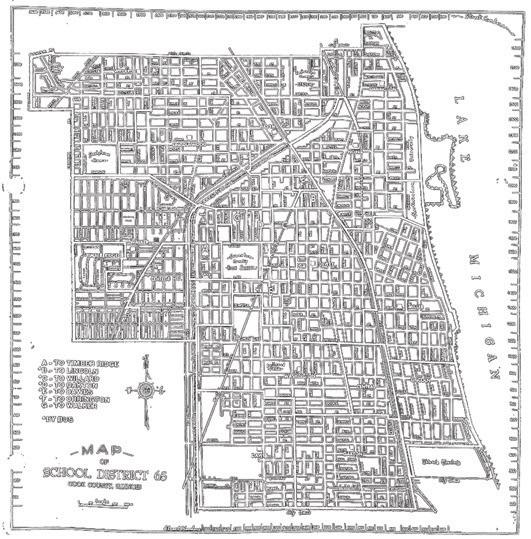

Plans for a K-8 school in Evanston’s Fifth Ward aim to address more than 50 years of education inequity.

WRITTEN BY AUDREY HETTLEMAN // DESIGNED BY ELISA TAYLOR AND AUDREY HETTLEMAN

In 1966, lifetime Evanston resident Janet Alexander Davis enrolled her son in kindergarten at Foster School, which was walking distance from their home in the Fi h Ward. Her son would be one of the last local students enrolled at Foster School before it became a magnet school and eventually closed. The next year, when racial integration went into e ect in Evanston Public Schools, Davis’s son was bused to Lincolnwood Elementary School in northern Evanston.

“It put a real damper on how much earlier we had to get up and get out of the house,” Davis says.

With the loss of the school and the dispersal of local children to schools throughout the city, the Fi h Ward’s sense of unity was shattered. But in a few years, that 50-plus-year inequity will be recti ed.

As plans currently stand, beginning in 2025, Fi h Ward students will have the chance to attend school in their own neighborhood for the rst time in over half a century. In 2022, Evanston/Skokie School District 65 (D65) approved plans to nally construct a community school on what is currently Foster Field. Proponents hope the project will decrease racial and educational inequities caused by the lack of a local school in a historically Black community.

The Fifth Ward school Davis once enrolled her son in, Foster School, opened on the corner of Dewey Ave. and Foster St. in 1905. It quickly became a pillar of the Fifth Ward community. Black students comprised 99% of its K-8 student body as a result of redlining and de facto segregation. With a school in their own neighborhood, parents could bond over their shared surroundings and kids could run home after school to play with neighbors. A community coalesced around Foster School.

“This is where relationships were formed,” Davis says.

But a re at Foster School in 1958 decimated the building, causing $500,000 in damage and forcing D65 to nd alternative temporary education sites for Foster students. At the time, many of Evanston’s schools were still segregated. Foster School students were not fully integrated into white classrooms around the city — their classes were instead taught in gymnasiums, cafeterias and community centers.

“There are aspects of the city’s race situation of which Evanstonians can’t be proud,” a 1958 Evanston Review article said.

Still, the article said, the integration of Foster School students was an example of “great and commendable progress.”

Foster School reopened within the year and students returned to their regular classrooms, but Shorefront Legacy Center Executive Director Laurice Bell says this disruption had lasting consequences.

“You have people who’ve been traumatized by the experience of a re at their school and having to leave something — and these are young kids,” Bell says. “Their teachers are being forced to leave, and they’re just having to deal with makeshi spaces that were not preparing people to be educated. And they got to see the di erence in terms of how they were treated.”

The community faced a signi cant loss when Foster School closed to local students in 1967 as part of D65’s integration initiative. In its place, D65 approved plans for a “city-wide laboratory school for testing new ideas in education,” according to a 1967 article from the Chicago Sun-Times, and renamed it the Martin Luther King Jr. Experimental Laboratory School (King

Lab School). The district aimed to attract white students to the primarily Black area as D65 integrated. The majority of Foster School students were therefore relocated to other D65 schools.

In 1979, the district moved King Lab School to Skiles Middle School in the Second Ward, e ectively closing the last form of schooling in the Fi h Ward. The closure caused controversy, as it meant busing Black children at disproportionate rates compared to their white peers. Roughly 450 Black Fi h Ward students from Foster School were bused to one of seven other Evanston schools. The rest of the local students were reassigned to schools within walking distance but outside of their immediate communities.

“When they closed Foster School, there were people that really believed integration would be a good thing for the Black community. They felt like if you have an integrated school, it’s good for your educational experience,” says Henry Wilkins, Evanston resident and STEM education advocate. “However, I don’t think it was understood what a burden was placed on the Black community to achieve integration.”

One year a er the district converted Foster School into a laboratory school, Bell began elementary school at Dewey Elementary in the Fourth Ward. While she remembers befriending Fi h Ward students who were bused to her elementary and middle schools (Dewey and Nichols, respectively), she also notes the impact coming into a community as an outsider could have had.

“Typically, what desegregation has done is put the weight of anything onto those who are being a ected the most,” Bell says. “When I think of being a child and making playdates with people who lived in another area … the accessibility to community experiences were di erent.”

That lack of community access is still present. Today, according to Wilkins, children living on the same block in Evanston’s Fi h Ward may attend as many as four di erent elementary or middle schools scattered throughout Evanston.

At the end of the day, Wilkins says one of the main reasons rebuilding a Fifth Ward school wasn’t a top priority for D65 was racism.

“There’s a lack of empathy for what the Black community had to go through,” Wilkins says.

There have been several previous initiatives for a Fi h Ward school since Foster School’s closing. In 2012, D65 proposed a referendum that would have provided funding for a new K-5 school in the Fi h Ward, along with improvements to existing schools. The referendum failed, with almost 55% of Evanston voters deciding against it. Wilkins says this was due to various residents’ concerns over taxes and the resulting lack of diversity in their own schools. In the Fi h Ward, though, 76% of voters were for the referendum, and rates were similarly high in other wards primarily composed of people of color.

On March 14, 2022, the D65 school board approved a new Student Assignment Plan, which included plans for returning a neighborhood school to the Fi h Ward. This plan speci ed the school would be a three-story, K-8 school with a 900-student capacity and a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design

District 65 approves plans for a school in the Fi h Ward. Two plans emerge as frontrunners: a K-8 school with room for magnet programs, or a K-5 neighborhood school.

The rst site concepts for the Fi h Ward school are presented to the community for feedback. A Dec. 6 community meeting brought over 150 community members to FleetwoodJourdain Community Center, eager to share feedback.

Planning logistics, including zoning and design submittals, begin. The City of Evanston and D65 continue to seek community input on the school’s development.

A D65 nancial assessment reveals the project is projected to be $25 million over budget. D65 board members convene a special board meeting during which they consider alternate plans for the school.

Construction is expected to begin on the new school site. Given the October budget revelations, this is subject to change as plans uctuate.

(LEED) Gold certi cation, a building sustainability measure. There was also a proposal to include space for the Dr. Bessie Rhodes School of Global Studies, a K-8 bilingual magnet program.

Community input has played a large role in determining what the school should look like. One example is the “Amplifying Black Voices on Education Equity in Evanston” initiative from education nonpro t STEM School Evanston. Completed in 2022, the project surveyed over 400 Black Evanstonians to gather their input on Evanston education and Fi h Ward school plans.

Wilkins, who founded the nonpro t, says the survey revealed that Black Evanstonians considered STEM the “number one subject area to focus on,” with African Centered Curriculum being the next most popular subject area. He says he sees the school as a form of repair but thinks it should go further than that.

“Give the community STEM at school. That’s the interest,” Wilkins says. “You replaced the physical building, but the community has asked for something more.”

Evanston’s history greatly informs current discussions around a Fi h Ward school. The Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization that records, studies and preserves the history of Black residents on the North Shore, has helped provide that context.

in this project and says D65 has, at times, failed to solicit it. She points to the school’s proposed location, Foster Field, as one example of the district’s lack of consideration. In an area already densely packed with businesses, residences and churches, Davis says, developing a three-story building could negatively impact the surrounding community.

“It’s not a perfect plan at all,” Davis says. “Nothing may be, but it has brought up some really uncomfortable situations for some of the people that live there and businesses that have been there.”

In addition to location concerns, a recent budget issue has upset those invested in the project. At an Oct. 16 special meeting, D65 interim Superintendent Angel Turner announced the proposed Fi h Ward school plan was 60% over its original $40 million budget.

There’s a lack of empathy for what the Black community had to go through. “ ”

- Henry Wilkins STEM education advocate

Bell, the center’s executive director, sees the current developments as a good step forward. However, she says, it doesn’t erase the impact of closing Foster School all those years ago.

“We robbed people of a certain type of education by closing that school. The community, in many ways, changed a great deal, and it’s not coming back,” Bell says. “Having a school will be an important step for the community. I just know that it’s a different community than what was previously considered.”

Now in her 80s, Davis co-chairs Environmental Justice Evanston (EJE). She and other members of EJE have attended D65 meetings, published op-eds and lent their environmental equity expertise to the district as they discussed building plans.

Davis emphasizes the importance of community input

Board members say this drastic increase in price was due to a combination of issues: namely, design changes, sustainability e orts, in ation and an overestimation of savings from not busing Fi h Ward students to other schools.

“I am just outraged,” Davis says. “Especially when there were people meeting with [D65] and suggesting certain things and talking about funding at the same time.”

In an e ort to bring down costs, the board modi ed plans at that meeting. Now, the new Fi h Ward school may be a twooor, K-5 school with a 600-student capacity and a LEED Silver certi cation — although that is subject to change.

“There’s some people that don’t feel like it was ever going to work,” Davis says. “So now that all this has hit the fan, I’m hearing a lot of negative feelings in the community.”

While the exact specifications of the new Fifth Ward School remain uncertain, Bell says she still believes in the importance of community schools. She stresses the significance of listening to community voices every step of the way to ensure the school accurately reflects the wishes of those in its immediate vicinity.

“Schools don’t just provide teaching of arithmetic or reading or history,” Bell says. “It’s a community space. It’s a safe space.”

Not quite international and not quite domestic, students from U.S. territories navigate uncertain classification on campus.

WRITTEN BY OLIVIA ABEYTA // DESIGNED BY JESSICA CHEN

As new Wildcats, Medill rst-year Ariel Paul and Communication third-year Gabriella Burgos were welcomed in two di erent ways. Both are students from a U.S. territory, but one was labeled as a domestic student and the other was placed in International Student Orientation (ISO).

U.S. territories hold a gray area quality — both legally and socially — when it comes to their perception within the U.S. and how their residents see themselves. Some students say they feel stuck in limbo, being not quite international or domestic. Their experiences re ect the larger issue of how the United States categorizes its island territories as part of itself and vice versa.

Today, there are ve inhabited islands that are U.S. territories: Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands. The combined population of these islands is more than 3.6 million people. Residents of these territories are not allowed to vote for president, and their delegates in the House of Representatives do not have voting rights.

language overall, metropolitan residents commonly speak Spanglish, a mix of Spanish and English.

When Burgos arrived in Evanston, she recalled feeling anxious to order food or talk to a doctor in English, as she didn’t speak it o en outside of her conversations with school friends in San Juan. Suddenly having every conversation in English was an adjustment, she says.

“I know the words but it sounds a little awkward when I say it,” Burgos says. “Am I being too formal? How do people say this? Those little things ran through my head a lot when I got here.”

On Burgos’ rst day of ISO, she started talking to another student and wasn’t aware that she had initiated the conversation in Spanish. Burgos’ “initial reaction” to start speaking in Spanish was another thing she had to change. Paying attention to how other people spoke helped her pick up some subtleties in language, Burgos says.

“I did nd it useful meeting other students from other Caribbean and Latin American countries,” Burgos says. “They would ask me, ‘Oh, you’re an international student?’ And I would be like, ‘No … not really. Maybe culturally?’ I still don’t know how to answer that question.”

Burgos, who is from Puerto Rico’s capital San Juan, says the part of the city she’s from is “very Americanized.” While Spanish is the dominant

Burgos says she relates to the experiences of students from Latin American and Caribbean countries more than U.S.-born students with Latine/Hispanic heritage, citing the di erences between growing up Latine in the U.S. and living most of your life in another country.

Overall, Burgos says ISO was a good experience where she made friendships she still has to this day. She says those

connections, especially with students from Latin America, were the most valuable thing ISO gave her in adjusting to life at Northwestern.

However, not all students from U.S. territories have the same orientation experience. Paul was born and raised on the island of St. Thomas of the U.S. Virgin Islands, but went through domestic students’ orientation instead of ISO. On their o cial documents, Paul identi ed as a domestic student.

Hilary Hurd Anyaso, Northwestern’s director of media relations, stated in an email that “anyone who wants to join social events for international orientation is able to.” However, anyone who does not have an F-1 or J-1 visa is not contacted by the O ce of International Student and Scholar Services. It is not required for students from U.S. territories to undergo ISO.

“There is a lot of confusion on what counts as international, and you don’t really know what your options are because of that,” Paul says.

For Paul, leaving St. Thomas’s closeknit community was a big change of pace.

“We have a lot of customs where we say good morning wherever we go to whoever [and have] a lot of respect in the community,” Paul says. “Everybody knows everybody.”

Culture shock varies from student to student, depending on which territory they are from. Something Paul had to gure out was what their communication style was going to be. Paul o en codeswitches their dialect to assimilate to how people talk here in Evanston.

“In the Caribbean, most islands have a distinct accent and a dialect which is kind

of di erent from how people talk here. I basically put on an American accent to make it easier for people to understand me and so I can navigate better,” Paul says.

Because of the gray area they occupy, students from U.S. territories can also get lost in the shu e of administrative logistics like receiving their Wildcard. Domestic students receive their Wildcard in the mail while international students pick them up at their area desk.

Paul did not get their Wildcard in the mail, so they went to their area desk in Allison Hall to ask about it. Paul says a er the desk learned they were from a U.S. territory, they assumed they wouldn’t have it. They redirected Paul to the Wildcard O ce at Norris, but the Wildcard O ce sent them back to the area desk.

For the second time, the area desk asked Paul if they were an international student. “Not technically,” Paul said, “But can you still check?” It turned out their card was there all along.

“With some aspects, like with the Wildcard, I get treated like an international student,” Paul says. “It’s a really weird liminal space of being international, but also not.”

Northwestern’s domestic students’ orientation assumes students are familiar with aspects of U.S. life such as navigating a city or setting up a bank account. But Paul suggests the University could do more to help students from U.S. territories acclimate, such as explaining how to use public transportation.

“I de nitely would have bene ted from some of the things international students get,” Paul says. “Like they got to go [on a eld trip] to Chicago and be here a little earlier.

“It’s a really weird liminal space of being international, but also not. ”

Despite bureaucratic confusion and culture shocks, Paul says their friends have played an important role in helping them acclimate to life in Evanston, such as shopping for a rain jacket and taking the CTA buses to Skokie for the rst time.

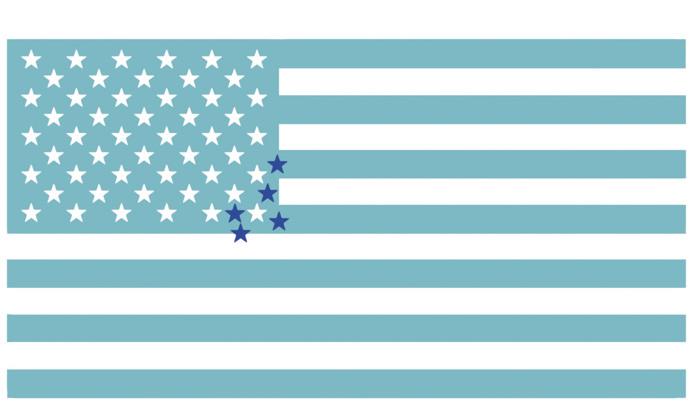

The liminal space Paul speaks of is emblematic of the e ects of the “logo map,” a term used by Northwestern history professor Daniel Immerwahr in his book How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

Immerwahr explains that the logo map is what people typically think of when they envision the United States: a country bordered by Canada and Mexico and enclosed by the Atlantic and Paci c Oceans — “From sea to shining sea,” as the song “America the Beautiful” goes.

However, that iconic shape only represented the true borders of the U.S. for three years: 1854-1857. The incorporation of inhabited and uninhabited territories expanded American borders far beyond the continental U.S.

“I can see why it helps to a rm something real, which is, if you’re coming from Guam you are not immigrating because Guam is a part of the United States,” Immerwahr says. “I can also see why it might be helpful to acknowledge the other thing that’s real, which is that Guam is a di erent kind of part of the United States than Wyoming is.”

How the University views and manages its students from U.S. territories re ects the perpetual question of how the U.S. views these ambiguously de ned areas. This relationship is especially complicated due to the colonial and imperial history behind how these places came to be territories.

“I don’t think this is Northwestern making imperial policy,” Immerwahr says. “I think it’s re ecting the imperial policy of the country.”

The ISO blueprint

Current ISO programming o ers a reference point for what the University could do to help ease the transition for students from U.S. territories and international students alike.

Weinberg second-year and Vice President of the International Student Association Sarah Norman tries to help students adjust to campus through her work as an international peer advisor (IPA). The IPAs work closely with the

O ce of International Student and Scholar Services to plan all of the programming for International Student Orientation, which takes place before Wildcat Welcome. But Norman says the responsibility for leading ISO activities fell primarily on IPAs.

“The IPAs took the kids to Chicago, we did all the social events, we took them downtown to AT&T when they were setting up their phone and we guided them on how to set up a bank account,” Norman says.

ISO receives less funding than Wildcat Welcome, Norman says. While there have been conversations regarding future collaborations between ISO and Wildcat Welcome, she says they have yet to become a reality.

Northwestern has regional programming with various admissions officers. Domestically, the U.S. is broken up into regions like the Midwest, Northeast and so forth. U.S. territories are included in these domestic regions, with Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands being in the South and Southwest region.

Norman is from the Philippines but says students from U.S. territories might bene t from having something like ISO’s regional networking program, which helps students nd “that sense of community away from your actual community.” International students are also organized into regions of the world — such as Oceania and Southeast Asia — for bonding activities, which are run by the IPAs and take place during orientation.

“In comparison to the other international student events, this was an event that gave students opportunities to mingle with people that have a more

similar culture. They’re from di erent countries, but they’re still from the same region,” Norman says.

She adds, even though international students may be from di erent countries, it doesn’t mean they are the only ones who have to adjust to a new life at Northwestern.

“Even if you’re from a di erent state in the U.S., it doesn’t necessarily mean you have the same experiences or you’re not going to be shocked,” Norman says.

WRITTEN BY SARAH LONSER // DESIGNED BY ALLISON KIM // PHOTOS BY LAVANYA SUBRAMANIAN

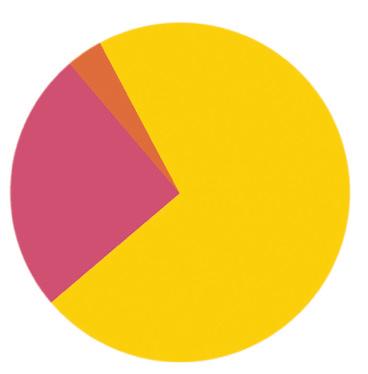

This past summer, the Barbie movie, Taylor Swi ’s Eras Tour and Beyoncé’s Renaissance Tour seemingly took over the world as extravagant, glittery ensembles dominated movie theaters and football stadiums.

“Having the freedom to not feel like we had to hide femininity and outrageous expressions of femininity is a really freeing thing,” Communication third-year Lena Moore says.

“Girlhood” may be having its moment in current media, but the signi cance extends far beyond the pop-culture sphere.

A special interest in girls, especially as consumers, has wide-ranging social and economic e ects. According to TIME magazine, there have been more than 1 billion Barbie dolls sold globally over the six decades since the doll was rst released. Forbes says the Eras tour “has the potential to generate a staggering $4.6 billion in consumer spending in the United States alone.”

debated for years, both in pop

At Northwestern specifically, School of Communication Professor Janice Radway taught a class called “Girlhood in Public Culture” from 2009 to 2022. The course investigated how girls are portrayed in media and culture — be that feminist literature or “girlzines” — and responses to that representation.

Over time, Radway has seen how social media and celebrity culture have intensi ed conversations about these topics at Northwestern and beyond.

“There was a moment where I realized these students, suddenly, are di erent,” Radway says of her students today. “They have a very di erent, much more exible and uid idea

“Northwestern students are very conscientious and canny readers who are really attentive to the dynamics of race and class and gender and sexuality,” she says.

Girlhood in the spotlight

“I could be myself and be a girl at the same time.”

about gender than my students had 10

For a more historical, but still relevant, approach to girlhood, English Professor Ilana Larkin teaches a class called “American Girlhood” which revolves around ideas of girlhood from the 19th century to the present. Larkin says conversations about girlhood in her Northwestern classes are unique because of the students. Their willingness to dive deep into complex issues, she says, makes for a thoughtprovoking and accepting space to discuss topics like girlhood.

Girlhood is having “a real cultural moment,” according to Larkin. She says this movement is partly driven by a collective desire to reclaim the past. Larkin attributes this desire to factors such as the current political climate and increasing cynicism, which have likely made people yearn for simpler, more innocent times.

Moore says she believes the surge of young women writing about their experiences in girlhood is a large part of why this moment is happening now.

“We, 21st-century girls, are being written by our contemporaries for the rst time,” Moore says.

Moore is one of those contemporaries. She cites songwriters like Swi , Lorde and Olivia Rodrigo as inspiration for a play with original music she is working on.

“Something that I thought about a lot was, ‘How can I represent my peers?’ and that’s something Olivia Rodrigo is doing,” Moore says. “She’s writing for people her age about her own experiences.”

Moore highlighted Rodrigo’s album GUTS, whose songs like “teenage dream” and “making the bed” exemplify an angsty adolescence to which many girls relate.

GUTS is one piece of media that brings girlhood to the spotlight, but girls are also sharing their experiences

through “get ready with me” vlogs, storytime videos and edits of their favorite girlhood moments set to songs from the Barbie soundtrack.

Memories of girlhood remain powerful across decades, especially for the eraslong reign of Taylor Swi . As a longtime Swi ie, Moore describes the magic of the Eras Tour, a space for embracing and celebrating feminine joy.

“A lot of people tell you you should not take pride in [being a Swift fan], or that you should maybe keep to yourself or not be as sparkly or dancy or flamboyant,” Moore says.

Now, in an era of reclaiming and rede ning girlhood, it’s time to embrace as much or as little sparkle and amboyance as you wish.

But there is more to girlhood than glitz and glam. Both Larkin and Moore note a rise in the acknowledgment and acceptance of the darker parts: the mistakes, the anger and the angst.

Some pop culture examples, The New York Times says, are rageful scenes in WandaVision, Big Little Lies and Beef The Times describes these as “striking scenes within a culture that still mostly prefers women either to carry their anger calmly and silently or to express it within a misogynistic framing.”

Women in the media are also letting themselves express the emotions they were once shamed and belittled for. Swift and Rodrigo attempt to address the scathing nature of female rage in songs “mad woman” and “all–American bitch,” respectively.

“We, as people who identify as girls or women, are feeling less and less like we need permission to tell our stories,” Moore says.

There is no “one” girlhood, but there are parts of girlhood being pushed to the forefront of culture by businesses and larger institutions, says Weinberg secondyear Inaya Hussain. She notes the capitalist uences on girlhood and how commercial brands and the media manufacture certain ideas of girlhood to young girls.

“Girlhood is o entimes, especially now, sold to us,” Hussain says. “Everything I can think about what I consider girlhood in my childhood is the big media brands. I would watch the Barbie movies, I would play with Bratz dolls, I would do all these things that t into this girlhood ‘brand.’”

This commercialization pushes forth a view on what girlhood “should” look like, which can make some young people feel le out. Medill third-year Max Sullivan says social pressure in their childhood years pushed them in the “not like other girls” direction.

“I was a contrarian, still am to a degree, and so I really embraced this, ‘No, I am smart and I don’t care about vapid, silly things,’” Sullivan says, “I found that persona made sense for me at the time. Of course, I don’t think that now.”

Prior to coming to Northwestern, Sullivan attended an all-girls school from h grade through 12th grade. During the later part of their high school years, though, they became more accepting of girlhood as a concept.

“‘Girl’ felt like a category I was inevitably falling into. It was not a choice I was making,” Sullivan says. But a er they learned to broaden their de nition of girlhood, “I could be myself and be a girl at the same time.”

Once at Northwestern, Sullivan began to regularly meet nonbinary and gender non-conforming people, which allowed for more nuanced discussions of girlhood. Even so, there are times when Sullivan feels the need to “tread lightly” in some of these discussions due to the chance for judgment, bigotry or misunderstanding from others.

The current discourse around girlhood follows a transformation of pop culture perspectives. For what feels like the rst time in mainstream media, girls are being written about candidly and openly by their peers. To fully understand girlhood at this moment, Sullivan says, we must listen to those who are currently experiencing it.

“We, as adults who have a lot of knowledge and experience to share, have to also recognize that girls do too. They

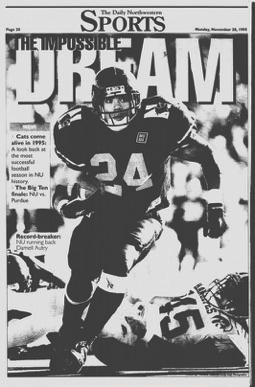

WRITTEN BY MITRA NOURBAKHSH DESIGNED BY JACKSON SPENNER PHOTOS FROM UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

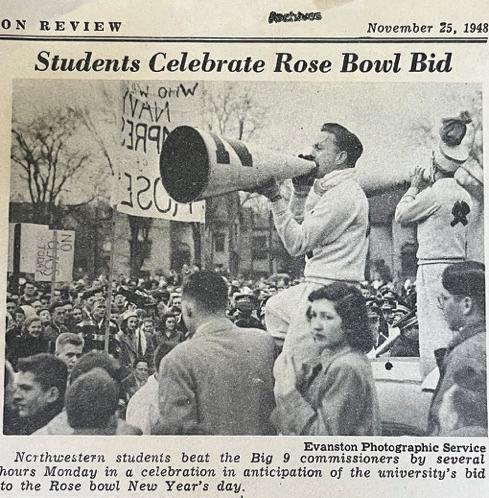

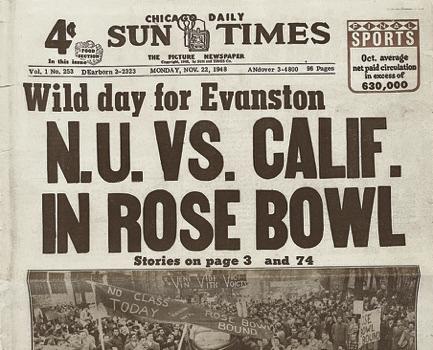

It was November of 1948, and The Daily Northwestern’s front page had the words “No School!” plastered across the top, with a huge headline reading, “ROSES!”

On Nov. 23, Northwestern students ooded the streets of Evanston in celebration of a sport that, these days, is more o en a source of frustration than delight.

For the rst time in history, the school’s football team had quali ed for the Rose Bowl and would be setting o for California that weekend. Little did they know, the team would not make it to another bowl for 47 years.

While Northwestern excels in some sports, football has not always been one of them. As the Wildcats conclude their 141st season, North by Northwestern takes an archival journey down memory lane to chronicle the highs and lows of Northwestern football.

Football rst found its place on campus as a game casually played between friends. As its popularity grew throughout the 1870s, students formed

1870-1900

Northwestern’s football team and the Big Ten are born.

a team and played a few annual games against other schools.

By 1889, Northwestern students were enamored with the gridiron pastime.

“A nal football game is now the society event of the season in New York and Chicago,” said an edition of Northwestern, a campus publication at the time. “And we think we see signs showing that our faculty are beginning to recover from

1905-1907

Football is suspended at Northwestern due to safety concerns.

1921

one of glory and fame for the glorious and famous N.W.U.”

Glory came just three years later in a nail-biter of a game against the University of Michigan that set the school’s attendance record with a turnout of over one thousand fans. With lots of enthusiasm but no Midwestern league to

Northwestern hires its first full-time coach and begins recruiting players.

The Wildcats finish second in the Big Ten, Dyche Stadium is constructed. 1925-1926

play in, Northwestern became one of the founding members of the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives, which later became the Big Ten.

For all the excitement on campus, in those days, football was more violent than it is today. A Northwestern article reported that, in a game between Yale and Princeton, “nearly every man was painfully hurt, and two of the participants were crippled for life …. Blood owed as freely as at a prize-ring entertainment, and in several instances sts were used with serious consequences.”

Along with a number of other schools, Northwestern suspended its team over safety concerns. By 1907 though, the second year of suspension, more than 90% of the student body had signed a petition to reinstate the team. With new NCAA rules in place that made the game safer, football came back to the University.

Although students were excited to have a team once again, there weren’t many wins to celebrate. Northwestern football just couldn’t stop losing, and by 1921, the University had had enough. They hired a full-time head coach and, for the rst time, began recruiting more intentionally.

With these changes in place, the next 30 years were marked with success. The Wildcats nished second in the Big Ten in the 1925 season, followed by the inauguration of state-of-the-art Dyche Stadium (now Ryan Field). A decade later, the Wildcats beat No. 1 ranked University of Minnesota, and 1941 brought Northwestern three recordbreaking years with All-American Otto Graham as quarterback.

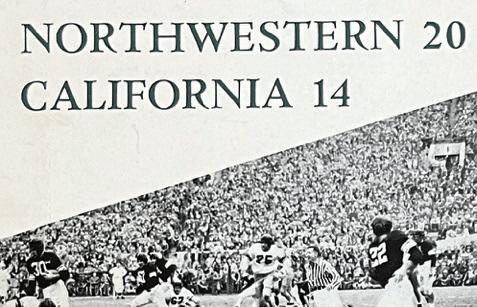

What is still remembered as one of the most remarkable moments in Northwestern football history came soon a er, on New Year’s Day in 1949.

1948-1949

Northwestern qualifies for and wins the Rose Bowl for the first time.

Celebrations began the day the team’s Rose Bowl bid was announced in 1948. According to The Daily, “the demonstrations were proof that the much-mentioned Purple Spirit was back a er its long wartime vacation.”

Chicago Sun-Times reported on a “Wild day for Evanston,” saying that “Evanston’s dignity was tossed for a heavy loss today as 8,000 Northwestern students swarmed into Fountain Square, tied tra c in knots, and took over …. They sang, cheered and cavorted. It was all spontaneous, which increased the fun.”

School was canceled for the remainder of the week, and the Wildcats traveled to the West Coast and triumphed over the University of California, Berkeley, in front of 92,000 fans.

The Wildcats record several hard-fought winning seasons. 1950-1970

The football team continued to play a number of hard-fought winning seasons in the following years, but the good times didn’t last forever.

Fumbling the ball

1973 marked the beginning of Northwestern’s slide down the rankings. In the next ve years, the team won 12 games and lost 43. In the two years a er that, the team won only a single game.

During those losing years, Northwestern football also reconciled with racism within the team.

Black athletes reported that coaches pressured Black players to return from

Northwestern’s slide down the rankings begins. 1973

The University hires Dennis Green, the first Black coach in the Big Ten. 1981

injuries before they were ready and kicked Black athletes o the team for minor o enses. The head coach at the time, Rick Venturi, also allegedly said he “wished he could get rid of the entire senior class of African American athletes,” according to a report by The Daily.

Thirty-one Black Northwestern athletes banded together to create Black Athletes United For the Light (BAUL) and came to then-Vice President of Student Affairs Jim Carleton with allegations of unequal treatment.

BAUL’s e orts were instrumental in Northwestern’s decision to re Venturi. In his place, they hired Dennis Green, the rst Black coach in the Big Ten.

“We hired what I consider to be one of the nest coaches in the country who has had many o ers from other institutions,” then-Athletic Director Doug Single said in a 1981 Daily article. “I think he’s going to be very successful.”

Green had high hopes for his rst season coaching the team, but nine months later, the headline of The Daily’s sports page read, “Not Again! Same old Wildcats Lose 42-0.”

In the article, Green was quoted saying, “For the last nine months I’ve been here, I’ve been saying pretty positive things. But how could you sit and watch that game without throwing up?”

The statistics backed up Green’s sentiment. That year, Northwestern became the Division I team with the longest losing streak in history: 29 losses in a row.

A er the team’s record-breaking loss to Michigan State, students rushed the eld, chanting “We’re the worst” in an ironic celebration. They tore the goalposts out of the ground, tossed them over the edge of the stadium, marched them down Central Street and threw them into Lake Michigan.

“Dyche Stadium south goalpost covered more ground yardage Saturday than the Wildcats,” a Daily sta reporter remarked.

The event attracted journalists from national outlets like CBS, NBC and The New York Times. Many fans and journalists attributed Northwestern’s athletic failures to the strict academic standards student athletes had to meet, but not everyone agreed.

“You don’t need to lower the standards to win,” one student pointed out. “How can we have good tennis and volleyball teams but not football teams?”

Still, the football team did not improve much, and by the mid-1980s, most students only went to the game for the “wild, booze-drenched tailgates” and to throw marshmallows at the marching band.

Although it seemed inevitable that successful years would be followed by embarrassing ones, it also became clear that no matter how much the football team lost, they would eventually make a comeback.

The team didn’t have many recordbreaking seasons over the next ve years, but by the early 2000s, Northwestern football became consistent. As a team that was notorious for its ups and downs, consistency was something to be proud of.

Pat Fitzgerald led the team to a number of victories during his almost 17-year tenure coaching the Wildcats, including back-to-back bowl wins and Big Ten West division championships in 2018 and 2020. But his legacy was marred by a hazing scandal that overtook the football team this past summer.

“IT WAS ALL WHICH INCREASED THE FUN.” CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

In this case, it took 15 years and a new head coach. Gary Barnett replaced Dennis Green, and he came to Northwestern with a mission to “take the purple to Pasadena.”

The Wildcats had not been to the Rose Bowl since 1949 and hadn’t won a Big Ten title since 1936. Under Barnett, the team did both. They shocked the football world with an upset win against Notre Dame. Then, in front of a sold out crowd at Dyche Stadium, they beat Penn State. The next game, at Purdue, clinched Northwestern’s Big Ten title.

Former football players alleged “egregious and vile and inhumane behavior,” including players being “restrained by a group of 8-10 upperclassmen dressed in various ‘Purgelike’ masks, who would then begin ‘dryhumping’ the victim in a dark locker room,” according to a Daily article.

The scandal led to Fitzgerald’s dismissal as head coach, and the University named new defensive coordinator David Braun the interim head coach.

With a program shaken by this summer’s revelations and coming o an almost winless 2022, many students had low hopes for this Wildcats football season. But the team has more wins than last year, and many are hopeful about Braun’s leadership going forward.

In any case, history has proven that no matter how bad things get, Northwestern football will bounce back.

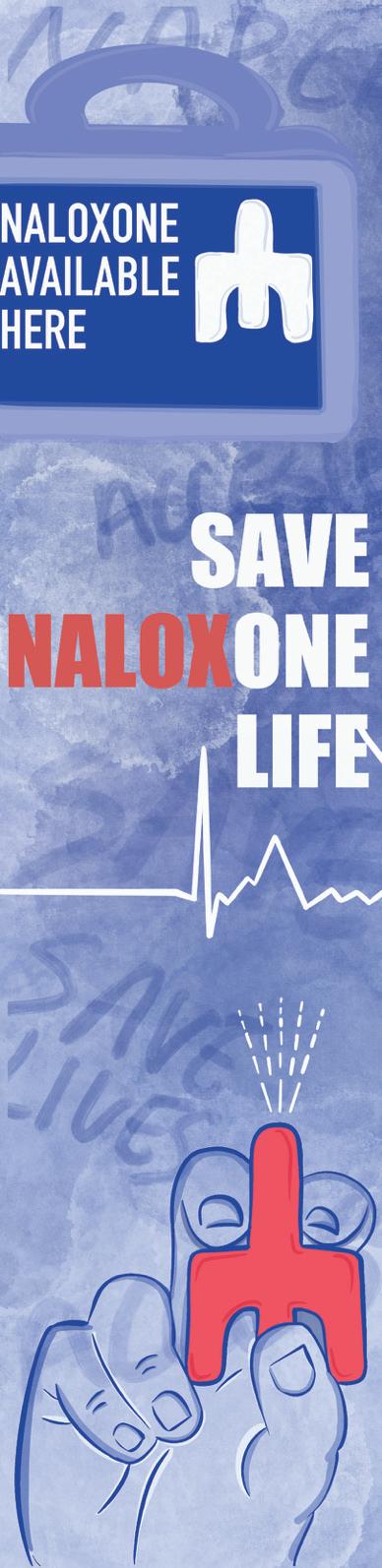

How Evanston and Northwestern are making lifesaving drug overdose treatments more accessible.

WRITTEN BY HANNAH COLE // DESIGNED BY MICHELLE HWANG

Students scatter throughout Evanston Public Library, readers browse the hundreds of titles and parents usher their children in for storytime. However, not every visitor enters the brick building for literary reasons. On the rst oor, near the circulation desk, is an emergency overdose box equipped with two doses of Naloxone nasal spray and instructions for use.

From January 2022 to July 2023, the City of Evanston reported 174 opioidrelated emergency room visits. In response, o cials installed ve overdose emergency boxes in locations across the city, including Evanston Public Library, Robert Crown Community Center, Evanston Ecology Center, Levy Senior Center and Fleetwood-Jourdain Community Center.

Northwestern University also introduced its own initiatives regarding opioid overdose prevention and Naloxone training on campus. The University o ers students the opportunity to learn how to administer Naloxone and provides two free doses upon completion. These measures are meant to protect residents and students from potentially fatal overdoses.

Naloxone, or “Narcan,” is a lifesaving medication that stops the