natural lands

meadows + fire = life

meadows + fire = life.

Controlled burning to save eastern prairies. measuring Monarchs. The latest on eastern Monarch populations. best-laid plans. How donors—including those who include Natural Lands in their estate plans—support everything we do.

natural lands number 167 • fall/winter 2025

editor and writer Kit Werner art director Kristen Bower senior graphic designer Brittni Hribar contributors Oliver Bass, Celine Butler, Gary Gimbert, Darin Groff, Ann Hausmann, Ann Hutchinson, Kelly Herrenkohl, Zane Miller, Fateen Stafford, Nick Upmeyer

Natural Lands 1031 Palmers Mill Road, Media, PA 19063 t 610-353-5587 | f 610-353-0517 info@natlands.org | natlands.org

The official registration and financial information of Natural Lands may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling toll free, within Pennsylvania, 1-800-732-0999. Registration does not imply endorsement. Information filed with the Attorney General concerning this charitable solicitation and the percentage of contributions received by the charity during the last reporting period that were dedicated to the charitable purpose may be obtained from the Attorney General of the State of New Jersey by calling 973-504-6215 and is available on the internet at www.state.nj.us/lps/ ca/charfrm.htm. Registration with the Attorney General does not imply endorsement.

facebook.com/NatLands instagram.com/natural.lands linkedin.com/company/natural-lands #naturallands

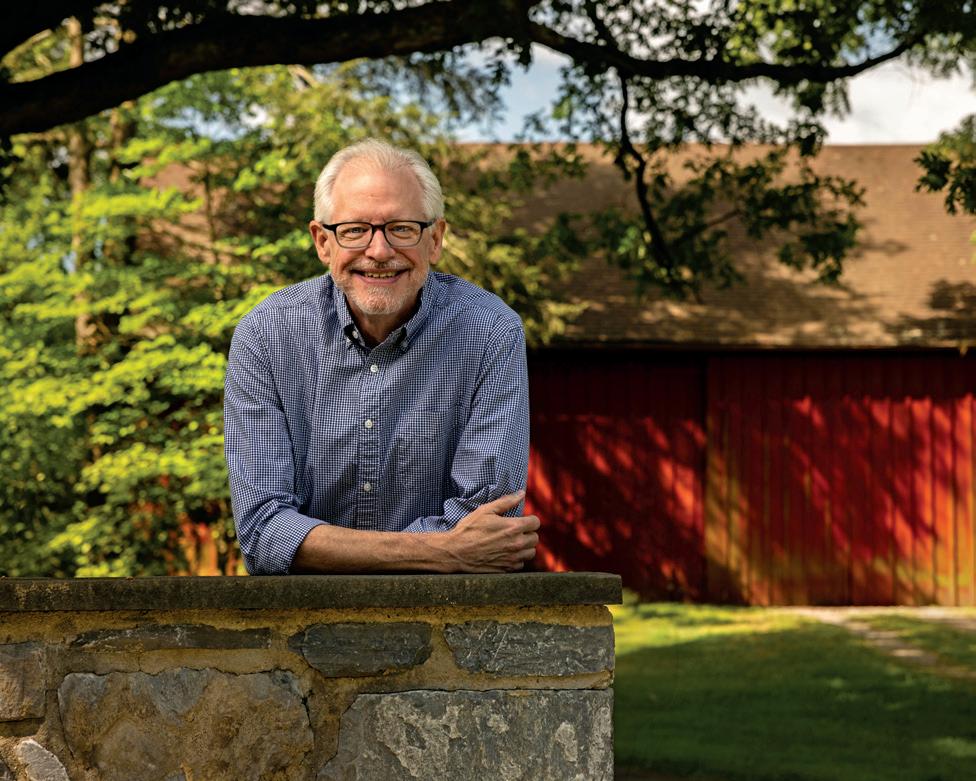

from the president

It’s been nearly 30 years since I stumbled upon an opening for a membership and communications role at Natural Lands. At the time, I knew nothing about the work of land trusts, but, having grown up as what today would be called a “feral child” spending countless hours in nature, the idea of open space conservation resonated.

I fell in love with both the mission and organization in short order. There are many reasons for that, including the people, the broad benefits of the work for humans and nature, and the permanence of the outcomes.

In hindsight, though, what spoke to me most is that saving open space, caring for nature, and connecting people to the outdoors and each other are inherently optimistic and hopeful endeavors.

The organization that is now Natural Lands was founded in 1953 to save what became the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge near the Philadelphia airport. The bold volunteers who undertook that effort faced daunting odds, yet they persevered and prevailed.

Today, Natural Lands’ remarkable staff and volunteers—empowered by a passionate community of supporters and partners like you—tackle every project with similar determination and optimism.

Every acre we protect, each tree we plant, every moment in nature we facilitate via our preserves and programs, and each community partnership we pursue is the result of a firm belief that we can and will succeed.

Over the more than 70 years since our organization was created, there have been periods of great challenge; moments when conditions in the world might reasonably have caused us to curb our ambition. But that’s not how we’re wired. It’s not how conservationists see the world.

A member of our conservation staff has a sign at her desk that reads, “Proceed as if success is inevitable.” Exactly.

OLIVER BASS, PRESIDENT

into the (Delco) woods.

The 213-acre site now known as Delco Woods was, until recently, the largest unprotected forest in Delaware County. Once slated to become houses and retail spaces, the property was the subject of debate for several years, with grassroots groups advocating for its conservation. In 2021, Delaware County purchased the land to become a green and sustainable public park.

Natural Lands worked in partnership with Toole Recreation Planning and Johnson, Mirmiran & Thompson to develop a master plan for Delco Woods, a years-long process that was finalized this past summer.

“We really wanted the community to shape Delco Woods so that the park represents

what county residents want it to be,” said Ann Hutchinson, FAICP, Natural Lands’ senior advisor for planning. “Robust community outreach generated more than 25,000 interactions with the project, including an open house, dozens of resident interviews, public meetings, focus group sessions, and online surveys. We heard a clear desire for a unique, welcoming space that would preserve the forest ecology, improve upon the existing trails, and provide spaces to gather for diverse recreational opportunities.”

At a public meeting in April, Delaware County Council introduced the master plan, which serves as a blueprint for the park’s creation. The plan preserves 90 percent of the existing forest, features several miles of trails and boardwalks, and includes a gathering space anchored by a tree canopy walk and pavilion on 40 acres of already-disturbed ground.

The phased plan begins with implementation of a woodland trail loop and a tree safety study. Delaware County has already applied for grants to find the more than $1 million cost of this initial phase.

“Delco Woods is a once-in-a-generation investment in open space and our community’s future,” said Delaware County Councilmember Elaine Paul Schaefer. “While this master plan is a long-term vision, we’re excited to begin with projects like the Woodland Loop Trail, giving residents an early opportunity to explore and enjoy this remarkable forest while we continue building a park that will serve Delaware County for generations.” n

Members of the Delco Woods Master Plan advisory committee

fresh start for Ash Park.

Nature is found in wide-open spaces but also in yards, common spaces, and public parks. In some of the region’s more densely populated communities, improving these nature footholds has widespread community impact.

Natural Lands has worked with the City of Coatesville for over a decade as a partner in the City’s effort to revitalize its parks. This past summer, the community reached a new milestone when construction got underway to bring a fresh start to Ash Park. At 9.3 acres, the park is the City’s largest and has a long history as a community hub.

The park’s master plan, which Natural Lands helped develop beginning in 2019, relied on extensive resident input and will serve as a blueprint for the park’s phased revitalization.

“The project will provide a cooling splashpad as an affordable replacement for a long-defunct swimming pool, expand the number of basketball

courts, and include engaging nature elements,” said Nick Upmeyer, landscape architect with Natural Lands. “There are pavilions for gathering with friends and family—one includes a misting station for hot summer temperatures. Native shrubs and perennials in the planting design for four rain gardens in the park will help address stormwater issues.”

“Since its founding nearly 100 years ago, Ash Park has served as the community’s most visited park for residents and visitors to congregate,” said Linda Lavender Norris, Coatesville City Council president. “It’s taken wonderful collaboration efforts to bring this impactful project to life. This transformation will serve to bolster the joy Ash Park brings to families and especially our City’s youth for years to come.”

Ash Park’s grand reopening is expected in spring of 2026. For more information, please visit natlands.org/ashpark. n

This project received funding from the PA Department of Conservation of Natural Resources, Community Project Funding from U.S. Representative Chrissy Houlahan and U.S. Senator Bob Casey, and Keystone Communities funding from State Senator Carolyn Comitta. During initial planning phases, MCDC (Movement Community Development Corporation) began fundraising efforts for the Ash Park water feature, with the help of Senator Casey and State Representative Dan Williams. The project was also funded in part by the Chester County Preservation Partnership.

meadows +

f ire = life

Say the word “prairie,” and most of us picture the vast plains of the Midwest. In contrast, the northeastern U.S. is the land of would-be woods, where every farm field and meadow quickly reverts to forest without intervention. Yet early accounts of this region—“Penn’s Woods,” as colonists called it— reveal a far more nuanced picture of Pennsylvania’s native ecology. One that included thriving eastern prairies that evolved with fire.

Some 400 years ago, English explorers of the North American continent were met with awesome expanses of grasslands. With no word for this habitat type, they adopted the French term for meadow: prairie.

Contrary to the common belief that the northeastern U.S. was once entirely forested, historical accounts depict tall meadows and broad savannahs tended with fire by Indigenous communities. Regional placenames are another clue. Southwest Philadelphia’s Kingsessing is derived from the Lenape word for “place where there is a meadow.” The Wyoming Valley region around WilkesBarre takes its name from a corruption of the Indigenous word for “great meadows.”

Eastern prairies have long disappeared throughout their range in the face of farming and development. The removal of native people and their millennia-old relationships with the land—particularly, their seasonal controlled burns that held back trees and regenerated the grasslands—have further ensured the decline of these unique meadow ecologies.

On Natural Lands’ nature preserves, however, prairies are making a big comeback.

“Over the past decades, we’ve converted almost 1,000 acres of former farm fields to native grassland meadows,”

said Gary Gimbert, vice president of stewardship.

“In 2025 alone, we installed meadows at ChesLen and Diabase Farm Preserves with a focus on pollinators, birds, and other wildlife that rely on this type of habitat for food, nesting, and—in the case of raptors—hunting sites.”

Grasslands are of particular importance to several species of native songbirds—including Bobolink, Eastern Meadowlark, and Grasshopper Sparrow—that build their nests on the ground, tucked between clumps of meadow grasses. With more and more land lost to development each year, grassland birds are struggling, having lost a third of their numbers in the last half-century.

Meadows are also home to a vast array of nectar-rich wildflowers that support our native pollinators: bees, butterflies, moths, wasps, beetles, and flies.

“Over the years, we’ve learned a lot about how to create thriving meadows,” said Gary. “We can’t just plant grass and wildflower seeds and walk away. Meadows take regular maintenance, or they’ll be filled with invasives and eventually become forests.”

One important technique Natural Lands uses to keep its meadows healthy is fire. For 25 years, prescribed burns have been part of the organization’s comprehensive approach to land stewardship. (continued on page 8)

Binky

benefits of prescribed fire.

• Helps control the encroachment of woody plants and the growth of invasive species

• Helps remove the buildup of dried plant material, which reduces the risk of wildfires

• Improves the release of nutrients from dead plant material so that they can be recycled through the ecosystem

• Warms the soil in early spring by allowing more sunlight to reach the ash-darkened ground, increasing microbial activity, further helping to release nutrients from dead plant matter

• Improves and increases food and cover for wildlife, as new growth flushes after fires and attracts grazing animals

• Improves plant diversity

Burning keeps woody plants and invasives at bay, and Binky Lee’s meadow thrives in July.

top to bottom: Ralph Hall, Bill Moses, Jill Sabre

Fame flower

Bobolink is a grassland nesting species that relies on meadow habitat.

Over the years, we’ve learned a lot about how to create thriving meadows. We can’t just plant grass and wildflower seeds and walk away. Meadows take regular maintenance, or they’ll be filled with invasives and eventually become forests. ”

Many meadow species have evolved not only to withstand but also benefit from periodic burning. Two native grasses, big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), respond to fire by sprouting substantially more growth and setting more seeds. Fire stimulates the underground rhizomes of Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum).

The secret to these and other native grasses’ survival of fire is their deep roots; three quarters of the plant is underground. The visible plants are merely the photosynthetic leaves gathering sunlight. These deep roots make meadow plants valuable carbon sinks. Unlike forests, they don’t release that carbon when burned because most of the plant material is under ground.

“The results speak for themselves,” said Darin Groff, director of land stewardship and burn boss for Natural Lands’ prescribed fire crew. “We walk away from a burn with the plants charred black. But very quickly after, you can see life—meadow grasses sending up new shoots, seedlings sprouting, hawks circling overhead.”

Added Darin, “Controlled burns aren’t a short-term fix. Meadow management takes ongoing effort from our land stewardship team.”

Fortunately for the birds, bees, butterflies, and blooms, Natural Lands is in the business of forever and will keep tending the remaining eastern prairies in our care. n

TURF GRASS

training & testing before ignition.

by Fateen Stafford, 21st Century Conservation Fellow

On an early morning in April, a crew dressed in yellow and green wildland fire gear starts prepping its equipment. The drip torches are refueled, the backpack pumps are checked for any leakage, and the hand tools are sharpened. All these items are loaded onto the back of trucks and all-terrain vehicles that have been specially outfitted with water tanks, pumps, and a few hundred feet of hose.

This is the start of a burn day at one of Natural Lands’ meadows.

But long before the first blades of grass are ignited, Natural Lands stewardship staff goes through significant training to be certified in the use of prescribed fire.

The process starts with study—about 40 hours of it to pass five courses covering equipment and terminology, the Incident Command System, and working with peers in a high-risk environment. Each year, the Natural Lands fire crew participates in this training, which culminates in a Work Capacity Test. Every participant must walk two miles in 30 minutes with a 25-pound vest on, to simulate the weight of fire-fighting gear. A Field Test requires physical demonstration of all the skills learned online.

After my training this past spring, I had the confidence to use the drip torch to light a section of meadow at ChesLen Preserve, use hand tools to scrape back the dried winter grass so that the fire would be contained when it hit the bare soil, and “mop up” at the end of the burn by spraying down smoldering areas.

So, the next time you visit a Natural Lands meadow, you’ll have a little sense of the work that goes in to keeping these habitats healthy. One fire at a time. n

opposite (illustration): Brittni

Hribar; this page

(left to right):

Jim Moffett, Jill Sabre

Every fall, Monarch butterflies across eastern North America travel thousands of miles to spend the winter in the mountaintop forests of central Mexico. They cluster by the hundreds in oyamel fir trees, waiting for early spring when they’ll begin the journey back to our region. For the past two decades, scientists in Mexico have estimated the population of Monarchs overwintering there by measuring the acres of trees occupied by the butterflies.

Monarchs. measuring

Last winter, the population of winter Monarchs in Mexico occupied about 4.4 acres, double the area of the previous year, giving hope for this beloved pollinator that has faced decades of decline. Experts believe the surge in numbers was due to favorable weather conditions during fall migration, unlike the previous couple of years when there were extended droughts and major storm events.

But, before we start to celebrate this nearly 100 percent increase, scientists believe 15 acres of roosting Monarchs is needed for the population to stabilize. While planting native milkweed species—the only plants on which adult Monarchs lay eggs and larval Monarchs feed—is critical, it’s only a part of the complex puzzle of this species’ survival.

avoid captive rearing.

One recent study, which aggregated about 2,600 community scientists’ observation of Monarch “roosts” along the fall migration route, showed that roost sizes declined from north to south along the flyway. These data show the roosts in Texas are about 80 percent smaller than they were 17 years ago. This indicates an issue during migration.

While experts don’t fully agree on the reasons for this decline, many point to a dramatic increase in captive-bred Monarchs. On the face of it, rearing Monarch caterpillars in predator-proof enclosures seems like a great way to help the species. Yet, captive breeding— which has increased apace with concern for the threatened species— can negatively impact overall species health. It can spread disease, reduce genetic diversity, and create competition for limited resources. Several studies have shown that captive-bred Monarchs have lower survival rates.

plant only native milkweed.

A little protozoan parasite, Ophryocystes elektroscirrha or OE for short, is causing big problems for these imperiled pollinators. High OE levels in adult Monarchs have been linked to lower migration success as well as reduced lifespan, mating success, and flight ability. The parasite travels with Monarchs, and, as they sip on milkweed flowers, the butterflies inadvertently deposit it on the plants’ leaves. When caterpillars hatch and feed on the tainted foliage, they ingest the OE.

When native milkweed species die back, the parasite dies along with them. However, non-native tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) remains evergreen through winter, allowing OE levels to increase year over year. Additionally, emerging research suggests that tropical milkweed may become toxic to caterpillars when the plants experience the warmer temperatures associated with climate change. As a way to help feed Monarchs, more and more people have been planting tropical milkweed. Ironically, much like captive breeding, well-meaning people are contributing to the butterfly’s challenges.

forest area occupied by Monarch butterfly colonies in Mexico

Since 1995, the largest area occupied by Monarchs was 44.95 acres, measured in 1997.

The smallest area was 2.2 acres in 2024.

Source: World Wildlife Fund

native plants for butterflies.

plant lots of natives, in addition to milkweed. Native milkweed species—which include common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), and poke milkweed (Asclepias exaltata) are essential for Monarch caterpillars. In fact, milkweed is the only species of plant the caterpillars can eat. It is also a great source of nectar for all pollinators.

But milkweed alone is not enough for adult butterflies. Planting a diversity of summer- and fall-flowering native plants ensures there are food sources throughout the adult stage of their life cycle. This not only helps Monarchs, but also beneficial native bees, wasps, and flies. Top choices include goldenrods, coreopsis, monarda, purple coneflower, Joe Pye weed, asters, phlox, and ironweed.

“At Stoneleigh, we’ve observed a few nectar superstars that draw an impressive number of pollinators, including wild mint (Mentha arvensis), anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), showy goldenrod (Solidago speciosa), clustered mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), and aromatic aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium),” said Ethan Kauffman, director of Stoneleigh: a natural garden. “These plants enrich biodiversity and are incredibly beautiful—great additions to any yard, garden, or container.”

add your observations.

The International Monarch Monitoring Blitz is a call to action for anyone interested in the species’ conservation to contribute to community science conservation efforts. The information collected by thousands of volunteers each year helps researchers assess population trends. For example, gathering data on the number of both Monarch caterpillars and milkweed plants allows for the calculation of a “cat”-to-milkweed ratio. Researchers use this ratio to estimate the size of the Monarch population.

continue to support conservation.

By supporting Natural Lands with your membership, you help Monarchs and other pollinators. The land conservation and stewardship work that is core to Natural Lands’ mission ensures native species have access to flower-filled meadows, clean water, and biodiverse flyways.

Your financial contribution also underwrites engagement programs that introduce children and adults to butterflies, moths, and other insects as well as conservation concepts. By providing impactful experiences with the wonders of nature, you help cultivate future generations of caring conservationists. n

swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

aromatic aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

goldenrod (Solidago sp.)

counting winged things.

fifth (22 percent) of U.S. butterflies have disappeared since 2000. About 33 percent of species underwent “significant shrinkage” in populations.

The study, published in the journal spring, combined data from 76,000 surveys including those by community scientists. Of the 554 species included, the scientists had enough data to make conclusions about 342 species. Their results revealed 13 times more species declined than increased, with 107 species losing at least half of their populations.

For the past three decades, volunteers and staff at Mariton Wildlife Sanctuary have been counting butterflies as a way to evaluate species populations and biodiversity. The participants count an average of 17 different species per year at our Easton, PA, nature preserve.

“There are some species that were noted in years past that are now absent, but we’ve also seen new species show up,” said Zane Miller, preserve manager. “For example, last year was a huge year for Huron Sachem, a southeastern U.S. species that migrates north each year. They seem to be expanding their northerly range due to climate change. Red-banded Hairstreaks are another southern species that have started showing up more frequently in recent years.”

The Mariton community scientists have noted a steep decline in Monarch butterflies that correlates with regional observations.

“Observers counted only two Monarchs in 2015,” Zane said. “But the past couple of years have been more hopeful. This past summer, we recorded 20 of them. Maybe the attention this poster-child pollinator has received in recent years— and the increase in milkweed many folks are planting in their yards—is helping turn the tide for Monarchs.” n

saving open sp

January 1, 2025 – June 30, 2025

Natural Lands has been protecting open space since 1953. In that time, we have completed hundreds of conservation projects, each unique in its own way. Saving Open Space is the first of our three mission tenets, and we go about it in a few different ways:

we save land to keep and care for Natural Lands is unique among the region’s conservation organizations because of our large network of nature preserves. We are committed to restoring habitats and stewarding natural resources on these 23,600 acres, and to sharing these special places with everyone.

we save land to give away

Because of our expertise in buying land outright (and in securing grant money to pay for it), we help conservation-minded entities acquire open space by buying land and then “flipping” it to these partners to care for in perpetuity. Through this approach, we help add hundreds of acres to state parks, forests, and municipal open spaces every year.

we save land through conservation easements

Much of the land we protect, another 28,000 acres, is privately held by individuals who have chosen to restrict its development through a conservation easement. An easement is a legally binding agreement that permanently limits a property’s use based on landowner wishes and applies to present and future owners of the land.

ace.

BERKS COUNTY, PA

1 Stauffer Property

12 acres

Union Township

Key Partners: Bureau of State Parks; Highlands Conservation Act, administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Natural Lands purchased this wooded property and transferred it to the immediately adjacent French Creek State Park. To date, the organization has added 398 acres to the state park.

This forested land provides essential habitat to wildlife, particularly migratory songbirds like Scarlet Tanager and Wood Thrush. In fact, these birds—along with 89 other bird species and hundreds of mammals, amphibians, fish, reptiles, and invertebrates—depend on Pennsylvania’s natural areas for their survival. These creatures are considered “Pennsylvania Responsibility Species.” The Commonwealth plays a key role in sustaining their global security by hosting at least 10 percent of their North American population or encompassing at least 25 percent of their North American range.

“More than half of Pennsylvania’s breeding birds are dependent on large, intact forests,” said Jack Stefferud, senior advisor for land protection for Natural Lands. “Anytime we can add acreage to existing forests like those held by the state, it’s a victory for conservation.”

It is also a win for the thousands of visitors to this land, which will be available to the public for recreation, including hiking, bird watching, and hunting.

Said former owner Daniel Stauffer, “Over the years, I was contacted by developers who were interested in building houses or developing a camping facility on

from development, and I and everyone else can still enjoy it.”

The Stauffer property is located within the Schuylkill Highlands Conservation Landscape, an area designated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources as a priority for land and water conservation, outdoor recreation, and compatible economic development.

CARBON COUNTY, PA

2 Recica Property

72 acres

East Penn Township

Key Partners: Carbon County Open Space Grant Program, Commissioners of Carbon County, Pennsylvania; PA Game Commission; William Penn Foundation

Preservation of the 72-acre Recica property marked the first conservation project to come to fruition through Carbon County’s new Open Space Grant Program. The fund was established after an astounding 82 percent of voters supported it through a ballot referendum in 2022. Natural Lands purchased this once-vulnerable, wooded parcel using grant funds from the program and immediately transferred it to the PA Game Commission as an addition to Game Lands No. 217.

Anne Marie Gorman

• Stauffer Property

The land lies within the state-designated Kittatinny Ridge Conservation Landscape and the Audubondesignated Kittatinny Ridge Important Bird Area.

The Kittatinny Ridge, which means “endless mountain” in Lenape, is the largest forested landscape in southcentral and eastern Pennsylvania, stretching 185 miles across 360,000 acres. Tens of thousands of birds of prey—including the state-endangered Northern Goshawk—travel the ridge, using rising thermals to aid them in their long migration flights.

The upland forest of the ridge offers a year-round home to Pennsylvania’s state bird, the Ruffed Grouse, and is designated as a Global Important Bird Area

The forested habitat naturally cleans and cools the air, filters pollutants from the water, and helps control flooding during storms.

“Nearly two-thirds of the Kittatinny Ridge is privately owned by thousands of individual landowners,” said Jack Stefferud. “What’s more, the region includes nine of the top 20 fastest growing counties in the state, making it vulnerable to both residential and commercial development. Thanks to the voters, this project is just the beginning of preserving land in Carbon County.”

DELAWARE COUNTY, PA

3

Powell Property

40 acres

Borough of Chester Heights

Key Partners: Chester Heights Borough; Delco Greenways Municipal Grant Program; Land and Water Conservation Fund, a program of the National Park Service administered in partnership with the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources; PA Department of Community and Economic Development, Local Share Account; Lorraine B. Powell; The Conservation Fund; private donations in honor of Fred Wood

For several years, Natural Lands worked to negotiate and secure funding for the Borough of Chester Heights

• Recica Property

to help reduce flooding and filtering rainwater before it enters the creek. This waterway is one of the heathiest streams in Delaware County largely because much of the land along it remains undeveloped. Chester Creek empties into the Delaware River and is part of a watershed that provides drinking water to 15 million people.

By purchasing the property and preserving it as open space, the Borough will ensure the land continues to provide these valuable environmental services and offer habitat to native wildlife. It will be open to the public, providing opportunities for access and recreation.

“This acquisition marks a wonderful chapter for the Borough,” said Borough of Chester Heights Mayor Gina Ellis. “Almost five years ago, former mayor Fred Wood suggested to me that we do what we can to purchase the land rather than have it developed. The tremendous work from Natural Lands, the cooperation and patience of the landowners, and the generosity of private donors in Fred’s memory made it happen. My only regret is that Fred is no longer alive to see this project come to a successful conclusion.”

LEHIGH COUNTY, PA

4 Breinig Property

7.27 acres

Lynn Township

Key Partners: Appalachian Trail Conservancy; Constellation Energy Generation through the Schuylkill River Restoration Fund and the Delaware River Basin Commission; PA Game Commission; Dana and Linnea Warren

This forested property protects scenic views from the Appalachian Trail and is located within the statedesignated Kittatinny Ridge Conservation Landscape, a globally Important Bird Area. At least 16 species of hawks, eagles, falcons, and vultures as well as about 140 species of songbirds travel the Kittatinny Ridge during spring and fall migrations. The forested landscape provides critical resting and feeding habitat for these birds during their taxing journeys.

While only 7.27 acres in size, the parcel was an inholding of the 8,513-acre PA State Game Lands No. 217— essentially a vulnerable hole in a forested landscape. Were it to have been developed, it would have fractured the contiguous forest cover that is so essential to migrating birds.

Natural Lands purchased the property and transferred it to the PA Game Commission.

“The Game Commission is pleased to partner with Natural Lands to conserve forested habitat in the Kittatinny Ridge Conservation Landscape along the Blue Mountain,” said Tim Haydt, bureau director for habitat management for the PA Game Commission. “This area of Pennsylvania is an important wildlife habitat connectivity corridor with State Game Lands comprising a large portion of protected lands. The parcel will also create additional access for State Game Lands No. 217 users via Gun Club Road.”

He added, “Natural Lands is adept at leveraging land acquisition grants to help the Game Commission purchase properties in the southeast part of Pennsylvania where prices are often out of reach. This effort is appreciated by hunters, trappers, and wildlife enthusiasts throughout the Commonwealth.” n

Breinig Property

Helm Creative Studio

best-laid plans.

On a warm day in late autumn, Natural Lands’ Events Coordinator Tianna Godsey leads a “bat bonanza” program at Mariton Wildlife Sanctuary in Easton, Northampton County. As they connect with both the outdoors and one another, participants gain knowledge of the winged wonders that live in our region and how Natural Lands’ stewardship helps them thrive.

Over in Coatesville, Chester County, Sadsbury Woods Preserve Manager Erin Smith works with volunteers to clean up the newly installed, ADAaccessible trail after a small storm. The trail provides access for people of varying abilities into this unique woodland habitat, which is home to several species of birds—such as Scarlet Tanager, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, and Ovenbird—that depend on its deep, sheltering forest for their survival.

About 60 miles away outside of Doylestown, Bucks County, Paunacussing Preserve Manager Preston Wilson sows native wildflower and grass seeds to improve the preserve’s meadows for pollinators. The deep roots of the new plants will help the preserve to act like a sponge when the rains come, absorbing and filtering water before it reaches nearby streams.

In Gilbertsville, in far west Montgomery County, Conservation Easement Steward Hannah Redmond walks and talks with a landowner as part of the annual monitoring process. These visits help ensure the agreements laid out in the property’s conservation easement are upheld.

Back at Natural Lands’ main office in Media, Delaware County, Kyle Rose, land protection program director, reviews real-estate appraisals, connects with partners, and submits a public grant proposal for a complicated conservation deal. While the project will require hundreds of hours of his and his colleagues’ time over the next year, it will ultimately lead to the perpetual protection of a high-priority landscape.

These are just a few examples from the array of daily initiatives that Natural Lands’ staff of 100+ experts in their respective fields undertake to save open space, care for nature, and connect people to the outdoors and each other in eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey.

now. forever. together.

Day in and day out, Natural Lands’ staff are guided by the heart of our mission to provide land for life and nature for all. It’s a promise we keep thanks to the generosity of thousands of supportive members and donors.

“But conservation is a long-game and we like to say we are in the business of forever,” says Natural Lands Vice President of Development Ann Hausmann. “Distributions from our endowments—made possible care of contributions from donors over seven decades, many of whom included us in their estate plans— anchor 40 percent of our operating budget each year and serve as an essential complement to the annual support we receive.”

Our Allston Jenkins Legacy Society—named for our organizational founder, who understood that taking on perpetual responsibilities requires perpetual funding— celebrates individuals who have left a conservation legacy in their estate plans. Natural Lands’ practice of sending all realized planned gifts, unless designated otherwise by the donor, to endowment guarantees their impact for future generations:

Bequests: Including a gift to Natural Lands in your will does not affect lifetime resources and can be modified at a later date if circumstances change.

Beneficiary Designations: Naming Natural Lands a beneficiary of your IRA, Donor Advised Fund, or other investment account creates lasting conservation impact.

Charitable Gift Annuities offer a steady income stream during a donor’s lifetime, after which the balance goes to work supporting Natural Lands’ mission delivery.

Real Estate Gifts can be transformed into assets that underwrite our highest priorities. n

The future is in our hands. To start a conversation, make your intentions known, or learn more about the Allston Jenkins Legacy Society, contact Kersten Appler, director of planned giving, or visit natlands.org/plannedgiving.

Willisbrook Preserve | 126 acres

welcome.

Natural Lands is proud to welcome Victoria B. Mars to our Board of Trustees, along with her love for open spaces and the power of connected landscapes. “I’ve been an outdoor person all my life,” she says. “I always prefer fresh air to being cooped up inside. Mountains, cool air, access to green space—that’s where I get my energy.”

From her earliest days as an assistant brand manager at Mars, Incorporated to her role as chairperson of the Mars Board, Victoria built a four-decades long career based on creating trusting relationships that yield mutual, impactful results. Victoria notes that the Mars Five Principals—quality, efficiency, responsibility, mutuality, and freedom—have guided how she runs her business and her life. “Being grounded in solid principles guides my decisions,” she says. “I’m especially intrigued by mutuality in land conservation—it should result in a win-win solution for the environment and for people.”

Victoria has been a friend of Natural Lands since 2006 when the Virginia Cretella Mars Foundation— named in honor of her mother— began supporting Natural Lands’ conservation work. Grants from the foundation provided essential gap funding on land protection projects where public funding covered most—but not all—of the expenses. “Investment from the Virginia Cretella Mars Foundation has enabled us to leverage significant public funding for nearly two decades, protecting more than 4,000 acres in Chester and Delaware Counties,” says Oliver Bass, president of Natural Lands. “We’ve been fortunate to have Victoria’s inquisitive and forward-thinking perspective inform our President’s Council since 2021. She will be an exceptionally valuable addition to our Board of Trustees.”

For Victoria, conservation isn’t only about preserving scenic views; it’s about ensuring that nature remains whole, resilient, and interconnected. “A connected landscape benefits everyone,” she says, “and collaboration among conservation organizations is key to achieving that goal.” A former board

member of EcoHealth Alliance in New York and the Center for Large Landscape Conservation based in Bozeman, Montana, Victoria looks forward to bringing lessons learned there closer to home.

“We are thrilled to welcome Victoria as a trustee,” says Susan Mucciarone, Natural Lands’ board chairperson. “With her principled approach, collaborative mindset, and substantive understanding of the value of connected landscapes, Victoria is poised to help shape the future of conservation in our region. We look forward to the vision, energy, and informed perspective she brings to our work.”

Outside of board meetings, you’re likely to find Victoria enjoying time with her family at one of Natural Lands nature preserves, which she began exploring in earnest during Covid. “I’m a firm believer that a board member should experience the work first-hand, not just through reading reports or looking at numbers. The more land we can conserve—especially here in the highly developed East Coast—the more we’ll be able to say we really had an impact.” n

board of trustees

Susan P. Mucciarone

chairperson

Jane G. Pepper

vice chairperson

Beth Albright

Barbara B. Aronson

Lloyd H. Brown

Rayenne A. Chen

Jason Duckworth

Regina A. Hairston

Gail Harrity

Peter O. Hausmann

Jeffrey Idler

Paulina L. Jerez

Ann T. Loftus, Esq.

Victoria B. Mars

Stephan K. Pahides

Robert K. Stetson

Andrew I. VandenBrul

William Y. Webb

chairperson emeritus

Peter O. Hausmann

emeritus trustees

Henry E. Crouter

John A. Terrill, II

William G. Warden, IV

Theodore V. Wood, Jr.

president’s council

Franny and Franny Abbott

Scott Albright

Jim Averill

Timothy B. Barnard and Meredyth D. Patterson

Joanna Jane Bartholomew

Jessie and Richard Benjamin

Laura and Bob Berry

Paul S. Black

Meg Maffitt

Christy Martin

Amy McKenna

Leah and Jason Morganroth

J. Kenneth Nimblett

James L. Rosenthal

Missy Shaffer

Steve Shreiner

Julia H. M. Solmssen

NextGen council

Jason Morganroth

Leah Morganroth co-chairs

James Burnett

Ryan Butcher

Jarrodd Davis

Tanya Dapkey

Eduardo Dueñas

Jake Faber

Riley Hennessy

Julie Kleaver

Elissa Klinger

Marion Leary

Jonathan Long

Bob McCaughern

Hunter McCorkel

Ryan Snyder

Latiaynna Tabb

Jennifer Trumbore mission land for life. preserving and nurturing nature’s wonders and resilience. nature for all. creating opportunities for joy, discovery, belonging, and connection in nature for everyone in our region.

Clarke and Barbara Blynn

Maggie Brokaw

Raj Chopra

Eleanor Davis

Phoebe A. Driscoll

Charlotte Friedman

Debra Wolf Goldstein

Lin and Ralph Hall

Catherine “Kate” Harper

David N. Hunter, Sr., AICP

Steven and Ann Hutton

C. Scott Kulicke

Joyce I. Levy, Ph.D.

Robin and John Spurlino

Karen Thompson

Jim B. Ward

Lee and Bill Warden

Penelope P. Watkins

Ardythe Williams

Susan P. Wilmerding

Theodore V. Wood, Jr.

Minturn T. Wright, III

Sherley Young

Eliza and Peter Zimmerman

Matt Feidler

Alicia Hamilton

Lindsey Levine

Stroud Preserve | 571 acres

Bryn Coed Preserve | Chester Springs, PA | 612 acres

Photo by Bill Moses