Join us on this 3-day exploration conference aimed at connecting First Nations, Métis, Inuit and university communities to create meaningful change in support of Indigenous education and implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action. Participants will explore critical issues related to education for First Nations, Métis and Inuit students and Indigenizing educational institutions in response to the TRC Calls to Action through these sub-themes:

• The Power of Storytelling: Crafting Compelling Narratives

• Language and Culture: Elders and Cultural Practitioners in The Workplace

• Cultural Diversity: Celebrating Differences and Building Bridges

• Shaping The Future: Trends and Insights in Implementing Truth and Reconciliation

eyou Istchee saw some Chibougamau residents claim to be a Metis nation. They claimed tax exempt status and the right to hunt, fish, trap and gather any time they wanted. Fortunately that went nowhere but in Ontario a group claiming Metis heritage got a government grant to purchase land. This even though there has never been any traditional Metis communities in the past. This angered Ontario First Nations.

Now seven First Nations are up in arms because of an alarming claim by the “Kawartha Lakes First Nation” of being an indigenous nation that was left out of the treaties. With only 20 members they are trying to lay claim to around 15,000 square kilometers. That claim overlaps the seven First Nations traditional territory and those chiefs are saying this is just another of people falsely claiming indigenous identity.

Self-proclaimed hereditary Chief William Denby claims to be in passion of documentary proof going back to 1780 proving his people had been “on this land for over 30,000 years. No documents have even shown proof of his own indigenous descent. Also archeologists believe First Nations came to Canada between 12-21,000 years ago.

Alderville First Nation Chief Tayner Simpson replied to one of the almost daily emails from Denby asking for evidence of his claim. Seen as a expert, he said that he had never heard of Denby’s group before. The next thing he knew was that Denby was claiming that the Alderville First Nation had transferred all authority of the region over to him. A claim Simpson denies.

All seven chiefs have issued a statement that said Denby and his group

were illegitimately asserting right, had no Indigenous connection to the region and that they would take “any necessary legal actin to protect our citizens, rights and interests.”

Denby has claimed Mohawk and Ojibwe ancestry and to be a descendent of the “Kawartha Tribe.” It turns out that the name Kawsrtha was created as part of a tourism campaign in the late 1800’s. Denby sent an email to a number of local city councillors that led to his arrest. It read, “We do not want to start to kill, poion, bury every one of you or your families if you do not stop destroying our farmland. We know where you all live. Nobody wants to go this far but we will. This is your final warning. You have no idea of how well organized we are and how much firepower we have in storage.” The case is ongoing.

Some researchers see this as farright strategy of claiming Indigenous identity to obtain lands and rights that could threaten legitimate First Nations. A noted Indigenous expert and University of Ottawa professor Veldon Coburn said, “we’re seeing cases where legitimate Indigenous peoples are having to defend their title.”

Chief Simpson perhaps put it best when he said, “In many ways, the federal government is no different from Bill Denby. They masquerade that they have ownership over all these lands. They use the same playbook to try to gain right and access to the territory. And they work to discredit the people who have been here for thousands of years.”

It looks like there is more trouble ahead for those of us in our home and Native land.

In

many ways, the federal government

is no diferent from Bill Denby. They masquerade that they have ownership over all these lands

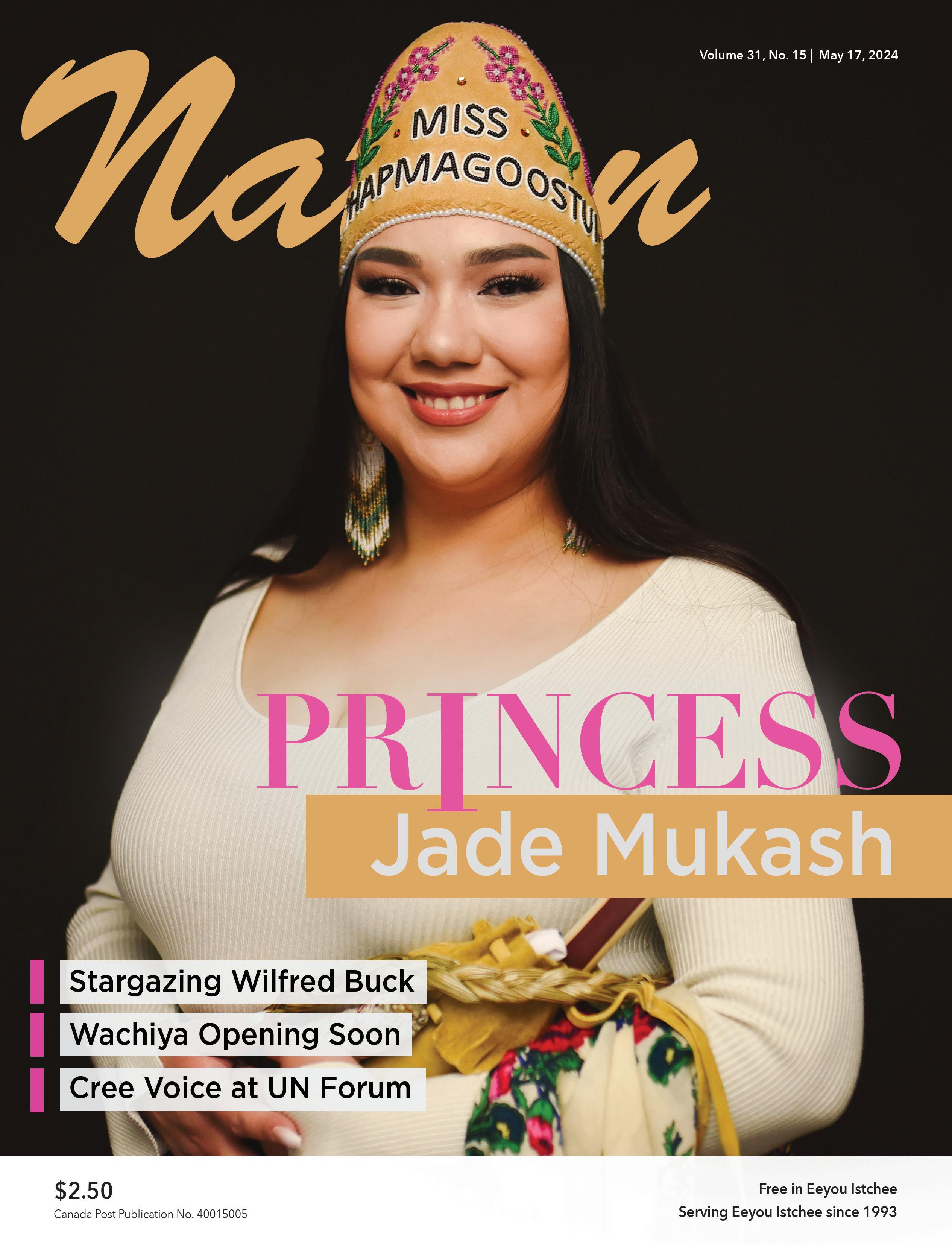

Nation is published every two weeks by Beesum Communications

BOARD L. Stewart, W. Nicholls, M. Siberok, Mr. N. Diamond, E. Webb EDITOR IN CHIEF Will Nicholls DIRECTOR OF FINANCES Linda Ludwick EDITORS Lyle Stewart, Martin Siberok PRODUCTION COORDINATOR AND MANAGING EDITOR Randy Mayer, Patrick Quinn CONTRIBUTING WRITERS M. Labrecque-Saganash, S. Orr, P. Quinn, J. Janke, A. Niambar DESIGN Matthew Dessner SALES AND ADVERTISING Danielle Valade, Donna Malthouse THANKS TO: Air Creebec CONTACT US: The Nation News, 918-4200 St. Laurent, Montreal, QC., H2W 2R2 EDITORIAL & ADS: Tel.: 514-272-3077, Fax: 514-278-9914 HEAD OFFICE: P.O. Box 151, Chisasibi, QC. J0M 1E0 www.nationnews.ca EDITORIAL: will@nationnews.ca news@nationnews.ca ADS: Danielle Valade: ads@nationnews.ca; Donna Malthouse: donna@beesum.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS: $60 plus taxes, US: $90, Abroad: $110, Payable to beesum communications, all rights reserved, publication mail #40015005, issn #1206-2642 The Nation is a member of: The James Bay Cree Communications Society, Circle Of Aboriginal Controlled Publishers, Magazines Canada Quebec Community Newspaper Assn. Canadian Newspapers Assn. Les Hebdos Sélect Du Québec. Funded [in part] by the Government of Canada. | www.nationnews.ca | facebook.com/NATIONnewsmagazine | Twitter: @creenation_news

reparations are underway for the grand opening of the Wachiya store in June on St. Paul Street in Old Montreal. It’s a significant accomplishment years in the making for the Cree Native Arts and Crafts Association.

“It’s definitely an exciting opportunity for CNACA,” said executive director Dale Cooper. “We want to make the Cree Nation proud, to make them look towards Wachiya as a source of achievement.”

The first Cree-owned marketplace for traditional arts and crafts opened in Vald’Or in the 1980s, becoming a showcase of Cree culture and regional artisans. When that Wachiya store closed in the early 1990s, there was always the hope it would return.

Before being elected Chief of OujeBougoumou last year, former CNACA executive director Gaston Cooper worked towards this reopening as he oversaw the development of local arts committees in each community. On March 31, 2023, the launch of wachiya.com was greeted with a buyer frenzy on featured items.

Dale Cooper said this online store has performed so well that CNACA struggled to maintain its inventory. With so many items, staff must individually ensure quality control, take product photos and add them to the inventory list. Certain artwork is challenging to categorize and will be easier to highlight at the physical store.

“We haven’t included a bowl with embroidery made by Paula Menarick yet on our website because we’re trying to figure out how to price it,” explained Cooper. “What you see on the online store only represents about 15% of our total inventory. We haven’t put our special items yet.”

In recent years, CNACA purchased over $200,000 in inventory from close to 900 Cree artisans who generally connect with Wachiya through their local arts committees. Product manager Jason Otter oversees quality control while ensuring artisans are paid a fair price.

“We educate them,” exlained Otter. “There are some ladies who lose money for the price they sell their items – I calculated a lady selling bags for $60 was only making 98 cents an hour. I created a template for them based on how much material you use, how much it costs and to make sure you’re making a profit out of what you’re doing.”

With Elders commonly offering prices from the 1990s, Otter also considers inflation, hours of labour, and the years of experience to produce such quality of work. Artisans appreciate this honesty as they’re paid immediately. Like CNACA, Wachiya operates as a non-profit organization, usually marking up products about 30% to cover costs.

Local arts committees play a valuable role in the growing Cree artisan ecosystem, providing workshops and other community programming while helping to source new Wachiya products and streamline deliveries.

CNACA worked with Air Creebec to become the official carrier of Wachiya products, with artisans delivering their products to designated centres before they’re flown to Chibougamau. The biggest online sellers are moose-hide products, tamarack decoys, slippers and jewellery. Waskaganish artist Edwin Jolly’s miniature canoes, snowshoes and paddles are also popular. The website is constantly updated with new products, accompanied by photographs and the artists’ names.

“We want to encourage a social economy in Eeyou Istchee, building up some of our suppliers to become independent,” said Cooper. “They can look to Wachiya as a steady source of income and opportunity, to be highlighted as an artist. We want to promote their story and biography along with photos of their work.”

As the Wachiya store opens on one of Montreal’s oldest streets in a busy tourist area, it aims to distinguish itself from nearby stores offering fake Indigenous goods often mass produced in China.

Products will come with a certificate of authenticity.

“Wachiya is at the forefront of offering authentic products made by our Cree artists and represent our culture passed down from generation to generation,” Cooper said. “There needs to be time put into educating people from around the world about Indigenous cultures. They’ll know our artists have been working on these skills for numerous years.”

The Cree method of producing moosehide uses all the meat and fur of the animal; for example, crafting bones into utensils. Nothing is wasted.

While the trend of non-Indigenous people wearing headdresses at festivals is hopefully a thing of the past, Cooper anticipates non-Indigenous customers asking questions like whether it’s okay they wear Cree earrings. As they hire a store manager, assistant store manager and a salesclerk, the goal is to spread awareness about the difference between appreciation and appropriation.

“We’re not just focused on providing products but also knowledge,” explained Cooper. “We want to facilitate workshops or classes. This could be beading circles or painting workshops, inviting some of our CNACA members and artists to teach or other Indigenous cultures within the area. We’ll probably have some admission fee with discounts to CNACA members.”

With an expanding Cree presence in Montreal at government offices, post-secondary student services and patients at the Espresso Hotel, CNACA hopes to develop partnerships with other entities and nurture cultural connections for urban Crees. They’re also seeking brand ambassadors to elevate their presence on social media.

“Having our flagship store here in Montreal, we obviously want to prioritize our Cree customers,” said Cooper. “Our overall goal is to promote these artists but also to retain our culture and influence the next generation. They are the keepers of our culture.”

“The social economy is a space and a practice where economics is at the service of social ends, not the other way around.”

Funding Grant for Social Economy Projects

Meals

Local

peggy.petawabano@cngov.ca

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

The Cree Development Corporation recently met with the Cree Nation Youth Council to discuss transportation infrastructure development proposed by La Grande Alliance.

Despite over 30 focus groups, 64 public meetings and hundreds of interviews with land users, there remains much skepticism to the project that former Grand Chief Abel Bosum called “an ambitious process to transform Eeyou Istchee’s infrastructure and economy” when the Memorandum of Understanding was signed with Quebec in 2020.

This approach to studying feasibility involved consultations with communities over environmental and social criteria. Community information officers and engineering firms met with thousands of Crees in the past year to spread awareness while emphasizing there’s no commitment to actually build anything.

“It was very unfortunate that there was a lot of miscommunication and misunderstanding,” said CDC President Clarke Shecapio. “It’s for Cree communities to be more proactive in the development of the territory. Like any other Cree who travels on the Billy Diamond Highway, there is a concern about the traffic and maintenance.”

The territory’s transportation infrastructure is crumbling. Although nearly $700 million has gone into BDH upgrades since 2017, some parts are already deteriorating. Projected heavier loads and increased traffic could soon make travelling the road quite dangerous.

About 1 million tons will be added annually from the three approved mines opening in the next three years. The projected fourfold increase in trucks combined with the tendency for people to drive down the middle of the road in winter could make accidents inevitable without urgent intervention.

While fixing roads may pave the way for mining development, the reality is that existing infrastructure was always built to facilitate the movement of workers and materials. La Grande Alliance intends to put the Cree Nation in the driver’s seat for the region’s sustainable development, improving

social and economic outcomes for communities.

“The question is how changes in infrastructure lead to greater development in the communities,” explained Marc Dunn, who as president of SYM Consulting has been involved in the process since the beginning. “People have a healthy skepticism, and I don’t blame them.”

The process has prioritized minimizing impacts for land users. Ideas like building a highway between coastal communities must be balanced with pragmatic concerns about costs, environmental damage and the restriction of wildlife movement.

“We tell people don’t misconstrue this participation as consent,” Dunn said. “This is a hypothetical exercise. If it were to be built, where could it go? Normally this stuff is discussed at the impact assessment phase later down the line, but we felt that would be too late.”

La Grand Alliance proposes upgrading and paving community access roads and the Route du Nord, with improved signage, safety and environmental measures, and the development of multi-purpose trails. Last summer’s fire evacuations highlighted the appeal of a proposed secondary access road for Mistissini.

A more challenging proposal would extend Road 167 over 500 km to the TransTaiga Highway, improving access to the eastern territory and significantly reducing travel time between Mistissini and Chisasibi. Crossing 15 traplines and adding 25 bridges, it would avoid protected

areas and caribou corridors as much as possible.

A proposed extension of the BDH would finally provide road access to Whapmagoostui. While the northernmost Cree community was initially identified as a potential host for a deep-sea port, economic feasibility and sedimentation from the recent landslide suggested a seasonal harbour for small vessels was a better choice.

Floating wharves would provide easy access for 20 small vessels sheltered by a breakwater. A boat ramp would be available for loading the community’s goods via dedicated barges with a causeway to connect the onshore area with local roads. The site chosen would make a deep-sea port possible.

A more controversial aspect of La Grande Alliance is the expansion of railway lines, which could be owned by the Cree Nation. The study states an average-length train could transport the material of 200 trucks, increasing road and wildlife safety while reducing air and noise pollution.

A proposed return to service of the Grevet-Chapais line, which was dismantled in the 1990s, would require new bridges and passenger stations at Chapais and south of Waswanipi. A bigger undertaking would be a railway following the BDH corridor in three phases over 30 years, which was judged to only make economic sense from Matagami to km 381.

The study’s emphasis on sustainable development contrast with the MOU’s first announcement, which promised the $4.7 billion “agreement” would “unlock” the region’s natural resources. Surprise turned to suspicion; almost 900 signed a petition launched by Cree youth criticizing the lack of consultation.

“Definitely, people thought we were building a project,” Bosum told the Nation. “It’s normal in the Cree world for people to react to what they don’t understand as soon as you talk about projects. I did expect questions to come up.”

Bosum discussed Cree-owned infrastructure during his first meeting with newly elected Premier François Legault in 2018, realizing that insufficient transportation pathways for new mining initiatives created an opportunity to serve the needs of the growing Cree population.

After first securing 30% of Eeyou Istchee for environmental protection, La Grande Alliance planned to mitigate impacts for what Bosum believes is inevitable development. Instead of waiting to react to someone else’s plan, Bosum felt long-term planning was important for potential projects that will take 10 to 15 years to launch.

“I don’t think our young people want to just wait for something to happen,” said Bosum. “Personally, I’d hate to be the one who is blamed for doing nothing or trying to avoid something. If we don’t plan, we’re not really leading our people.”

Brian Fireman’s flame has gone out. The cherished singer of Cree Rising, Fireman’s passing in a Montreal hospital April 19 has left a void in the music world, but his passion for music and community will live on.

“It is with great sadness to let our fans know of the passing of our dear brother, friend, frontman, the voice of Cree Rising,” his band members said in a statement. “We, the band mates, are very saddened and shocked of Brian’s departure and it has been difficult for our families as well. We will miss Brian’s leadership, encouragement, and uplifting words on and off the stage but most of all, his voice on stage with us.”

His band members added that Fireman “had a great vision for music with the Cree Rising band and the Cree Nation of Eeyou. Brian had so much compassion and respect to his band mates and to those who crossed his path.”

They noted that his goal to record another album is now on hold. However, “We all know that eventually we will move forward just like he encouraged us on his last message before he left,” they said. “Until we meet again and our sincere condolences to his wife, children, grandchildren and extended family.”

Tim Whiskeychan’s victory lap

The exhibition “Hommage à Jean-Paul Riopelle,” featuring the captivating works of Waskaganish artist Tim Whiskeychan, has met with resounding success, prompting La Maison autochtone de

Mont-Saint-Hilaire to extend its run until May 28. Originally slated to conclude late April, the exhibition’s exploration of northern territories in the style reminiscent of Riopelle has captivated art enthusiasts and dignitaries alike.

The winter exhibition was curated to commemorate the anniversary of Riopelle’s passing. Huguette Vachon, Riopelle’s companion, lauded Whiskeychan’s artistic prowess, expressing admiration for the exhibit’s “absolutely fabulous bestiary.” Vachon recognized Whiskeychan’s ability to evoke Riopelle’s iconic style while infusing it with his distinct Eeyou perspective.

A final celebration of Whiskeychan’s exhibit will take place at La Maison autochtone May 26, highlighted by talented cellist Kelly Cooper. There will be a performance that merges visual art and musical finesse, a fitting conclusion to a journey through the landscapes of Riopelle’s

inspiration and Whiskeychan’s innovative interpretations.

Mine rehab and airport investment

Natural Resources and Forests

Minister Maïté Blanchette Vézina recently announced Quebec’s support for initiatives in the Nord-du-Québec region. These include the ongoing reclamation of the Mine Principale mining site and a $32 million investment to renovate La Grande-Rivière Airport in Radisson.

During her press event at the Aanischaaukamikw Cree Cultural Institute in OujeBougoumou April 22, Vézina emphasized her government’s commitment to environmental improvement and regional development.

The Mine Principale restoration project aims to enhance environmental quality and diminish risks to public health and safety, she said. “The reclamation of Mine Principale

and the rehabilitation of La Grande-Rivière Airport are two announcements that local communities have long awaited,” Vézina stated.

Chibougamau Mayor Manon Cyr, Ouje-Bougoumou Chief Gaston Cooper and Alain Coulombe, CEO of the Société de développement de la BaieJames, expressed their support.

“As we mark this important milestone, we pay tribute to the Wapachee family, who played a crucial role in addressing the environmental and health concerns related to Mine Principale, located on their family trapline,” said Cooper.

“Their legacy fuels optimism for this project, which promises economic revitalization through job creation and expansion of local businesses, as well as meaningful environmental improvements and strengthened community health.”

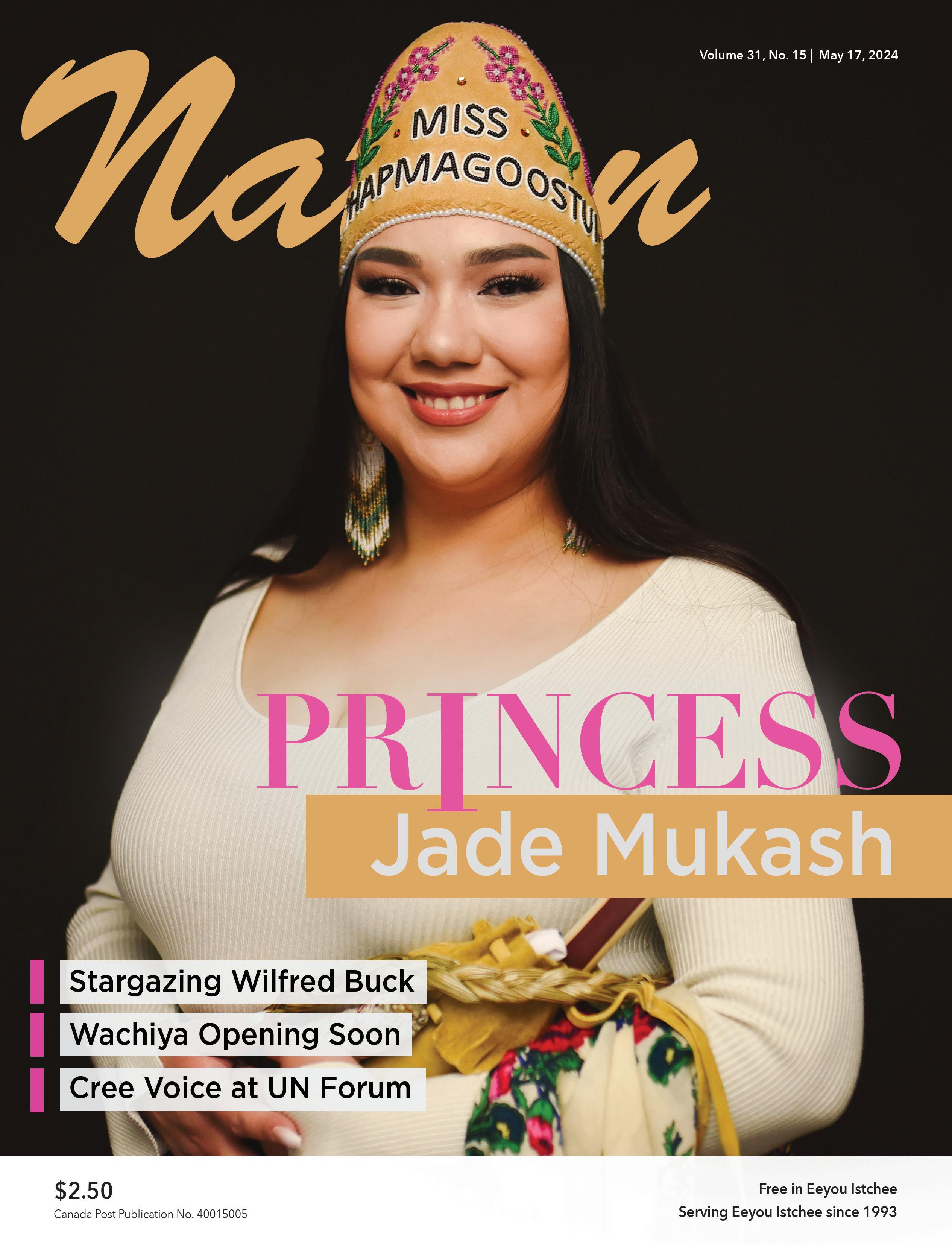

With over 10 years of experience as an artist and an advocate for Eeyou Istchee youth, Jade Mukash is passionate about using her creative and communication skills to empower and inspire others.

As the Youth Representative for the Cree Women of Eeyou Istchee Association, Mukash brings an artistic flair to the organization. “I value the opportunity to contribute to the wellbeing and development of my community and to celebrate the culture and identity of the Cree people,” says Mukash.

In 2023, Mukash was crowned Miss Whapmagoostui – a title that carries prestige and responsibility. For Mukash, it’s not just about wearing a crown. It’s to embody a legacy of resilience, cultural pride and service to community. As Miss Whapmagoostui, she says her platform revolves around living a ceremonious and traditional lifestyle – a testament to her deep connection to Cree heritage and values.

Mukash developed a strong sense of identity and purpose from an early age. “I am the third generation in my family to live this lifestyle and choose to do it in sobriety,” she explains. “I hold sobriety dear to my heart and find it has a positive impact on oneself physically, emotionally and spiritually.”

Mukash wore her community crown at the Miss Eeyou Eenou Iskwaau pageant in Eastmain last November, where she was the first runner-up.

“When I became Miss Whapmagoostui, I knew that one of my main duties was to represent everyone at the event in Eastmain and after that. I wanted to represent my community as best as I could.”

Her advocacy extends to cultural platforms and events. “I attended the Cree Nation Youth Council summit as well as the first Indigenous Women Leadership Conference,” she shares. “These are big events where I was able to speak and offer workshops about living a ceremonious lifestyle.”

The title solidified Mukash’s commitment to the Cree language and culture. “I noticed that all my fellow contestants did their speeches in Cree, and mine was the only one in English,” she recalls. “So, after being crowned, I knew it was important for me to represent our language.”

Her journey as an advocate and artist has led her to significant opportunities on national and international platforms. “I am an advocate for proper health care in our communities,” she explains. “After being a caregiver for some family members, this is a very important issue for me.”

Through her dedication to community wellness, she actively contributes to initiatives that promote cultural awareness and holistic health.

“Whapmagoostui is a fly-in community, and we have one small clinic. So, you can imagine how much work needs to be done for the healthcare system in our communities to ensure that everyone has proper access and care,” says Mukash.

After the announcement in April that she would be one of 26 contestants vying for Miss Indigenous Canada 2024 this summer, the outpouring of congratulations was impressive.

The Chisasibi Cree Women’s Association stated that they were “incredibly proud and thrilled” for her. “Jade’s courage, determination and dedication are an inspiration to us all. Her representation not only showcases the strength and resilience of the Cree communities but also opens doors for future generation to shine even brighter,” posted Shelby Bates on the organization’s behalf.

“It is such an honour to represent our beautiful people and I am very humble to represent my community. I was able to meet so many intelligent and loving young women in the Eeyou Istchee community through the 2023 pageant, but I haven’t seen them again since then. So being at these events is a big thing,” says Mukash.

“We are still in the early stages of understanding our Indigenous pageants and how they can have a positive impact on our people and our youth so I would encourage everyone to speak to the princesses in your community, learn from them and their strengths. Encourage them to continue to share the knowledge and traditions of their communities at events like these. This is a very big opportunity, and I am excited to see the other princesses at future events.”

“We are still in the early stages of understanding our Indigenous pageants and how they can have a positive impact on our people and our youth so I would encourage everyone to speak to the princesses in your community”

- Shelby Bates

First Nations Executive Education (FNEE) offers short leadership programs that have been developed specifically to meet First Nations needs.

PROGRAMS DESIGNED FOR CURRENT AND ASPIRING FIRST NATIONS LEADERS

› Elected officials and administrators

› Entrepreneurs and business CEOs

› Managers, general directors and program directors

› Women an d leadership

› Economic leaders – Grand Circle (binome registrations)

ALSO AVAILABLE CUSTOMIZED PROGRAMS

DEVELOPED IN-LINE WITH THE SPECIFIC NEEDS OF INDIGENOUS AND NON-INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS

LIMITED PLACES AVAILABLE — SUBMIT YOUR CANDIDACY

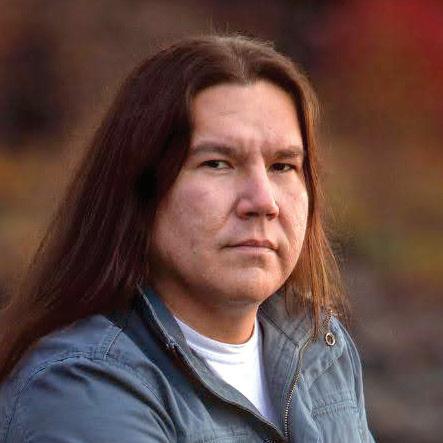

The documentary Wilfred Buck dances between the past and present, between the earthly and the celestial. It traces the journey of Cree astronomer Wilfred Buck from the Opaskwayak Cree Nation in northern Manitoba as he overcomes the demons of his youth to reclaim ancestral knowledge of the cosmos.

Created by acclaimed Anishinaabe filmmaker Lisa Jackson, the film took inspiration from Buck’s memoir, I Have Lived Four Lives. Jackson described “these crazy stories” of his younger life as “a lot of sadness and difficulty.” Nonetheless, she instantly imagined a film adaptation – snapshots of his tales from the 1970s – with rock and roll pounding in the background.

Indeed, this hybrid documentary is full of grainy re-enactments of Buck’s childhood as well as archival footage from the National Film Board. They paint a picture of an upbringing marred by loss, displacement and racism.

In voiceover narration using snippets of Buck’s memoir, we learn how the trauma of colonization led the young Buck down a path of addiction. Eventually, by reconnecting with his Indigenous heritage, he breaks this pattern of self-destruction and becomes a guiding figure in his community. Footage of his current life as a respected Elder and educator reveal a man with ties to both the stars and the spirits.

Buck left school as a teenager, before finishing his education as an adult. He earned two degrees from the University of Manitoba and made a name for himself as an expert on both Indigenous and Western astronomy. For 25 years, he has taught students ranging from kindergarten to university level. After a childhood alienated from spiritual practices though harsh Catholic teachings, he has become a Cree ceremonial leader.

Throughout the film, Buck emphasizes the value of uncertainty in education. Referring to ceremonies as a way to surrender control, the film suggests that rituals allow people to empty the mind for new information.

Humility is required, in his worldview, to leave the door open for growth. The arrogance of certainty – of being sure there is nothing left to change, and nothing more to learn – leaves people unable to evolve. “We have to keep our minds empty for new possibilities and be aware that there’s other things out there other than what we see with our set of blinders on.”

Buck views Western science as “anything that can be measured,” but adds that there may be more to reality. He treats dreams as a land of possibilities: “Everything in our reality right now was at one point a dream. And it’s that process of following that dream and making it a reality.”

For Buck, Indigenous science “is holistic and integrated and connects with energy and is interdependent. Indigenous cultures all over the world understand that everything is connected. Everything is intertwined. Everything has repercussions. Everything has rever-

berations. Everything has ripples, and everything has responsibilities, and they’re all tied together.”

By neglecting this integrated perspective, science can be “used to create a lot of harm.” Buck treats ethics and scientific study as inextricably linked. He believes in the accountability of the impact of science – on animals, the environment and one another.

In striving to educate his community about astronomy, Buck reminds them of their ancestral links to the cosmos. He says that when you go out at night, and feel that “awe” of stars, you are reminded that “we’re connected to everything around us.” He concludes that “we’re responsible for occupying the space at this time, at this place,” and that “the way we leave it is what we leave for the people that are coming after us.”

Jackson, for her part, conceived this documentary as a dialogue between Western and Indigenous science. She credits Western science for its ability to break topics down and comprehend the minutiae of the universe. Likewise, she credits Indigenous science for exploring the big picture.

Jackson characterizes the Western approach as “science over here, and then stories and poetry over there.”

However, she adds, “To me, Indigenous storytelling is a methodology of knowledge transmission. It is a story, and the story has so much knowledge, and you can’t separate those things.”

Jackson cites the constellation of a sturgeon as a powerful metaphor for the themes in her film. She points out that sturgeons are “ancient creatures” that have been around “since the dinosaurs” and survived “all these mass extinction events.”

She goes on to say that “It’s an amazing metaphor for Indigenous people and cultural practices and knowledge.” Jackson characterizes sturgeon as being low in the water, and up in the star constellations. Ever-present, tangled up, transcending time and space.

These heady concepts lead to the most abstract and haunting visuals in Jackson’s film. For example, several scenes show extreme closeups of a glittering meteorite.

Jackson recalls seeing a still image of one and comparing it to a stained-glass window. She says that when the meteorite is sliced very thin, a phenomenon called “cross-polarized light” can occur. Brown or grey rock can suddenly take on “unbelievable colours.”

She was struck by the unexpected notion that a “plain and basic” rock can produce an “incredible rainbow.” Jackson describes the meteorite as “in some ways a scientific specimen,” while emphasizing the need to see “the beauty, and the poetry of everything it contains.”

Western logistics, Indigenous insight.

Cree

At the world’s largest annual gathering of Indigenous leaders and policymakers in New York City, the Cree Nation had a leading role in discussions about working collaboratively with state governments to advance self-determination.

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) is a high-level advisory body that has focused on raising awareness and gathering expert recommendations since 2002. Several side events examine pressing issues that help develop policies upholding Indigenous rights.

Cree justice director Donald Nicholls moderated a side event April 18 –“Paving the Way for Future Generations: Reclaiming Indigenous Rights and Collaborating with State Governments for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Relations.” Grand Chiefs from the Cree, Algonquin-Anishinabeg and Atikamekw Nations were joined by Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Ghislain Picard.

“This panel was unique because it’s representing Indigenous people in Quebec saying don’t treat us like the enemy,” Nicholls told the Nation.

“We’re here to build those relationships. It shouldn’t be adversarial. Voicing our concerns and proposing solutions is very important if we’re really going to have participation.”

Atikamekw Grand Chief Constant Awashish explained that just as he wants a strong Canada and Quebec, it’s in their best interests to have strong First Nations. While there has been slow progress toward this mutual empowerment, he said his people still don’t feel a sense of belonging.

“Our biggest enemy is the status quo,” Picard asserted. “Staying idle on key issues is helping the agendas of governments. Despite the geopolitics, our nations are creating those spaces for themselves.”

Picard referenced the Cree-Innu sharing agreement for harvesting caribou as an example of First Nations creating solutions independently of federal and provincial governments. Grand Chief Mandy Gull-Masty said the Cree Nation continues to leverage the

JBNQA for enhance the rights of Cree and neighbouring nations.

“We used this position to our advantage and continue to build on our land claim,” said Gull-Masty. “I don’t think this is the only governance system we should adhere to – my neighbouring nations across Canada are united in the position we take although we come from different histories.”

The conversation connected this advocacy with participation in decision-making that impacts Indigenous rights and lands. Still, Indigenous peoples remain largely on the periphery of key discussions.

“It’s the illusion of inclusion without us being there,” said Algonquin Grand Chief Savanna McGregor. “I see that hunger to finally be treated as equal and not a second thought. It’s important to show we’re not complacent.”

Nicholls noted that when UN members came together to design the first charter of human rights in 1948, Canada applied it to everyone except Indigenous peoples. As the Cree Nation achieved greater recognition through the legal system, in the 1980s it advocated for Indigenous rights in the Canadian constitution.

While Canada voted against the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) when it was adopted in 2007, it has since not only reversed its position but in 2021 became the first country to adopt it into domestic law.

The Supreme Court’s unanimous affirmation of Indigenous jurisdiction over child and family services in Bill C-92 this February was also the first time that UNDRIP was clearly shown to be enforceable in Canadian law. Speakers at the UN event commended Canada for developing an UNDRIP action plan but said the process hasn’t been inclusive enough.

“We want to see a national mechanism that ensures compliance without having to go to court to have resolution,” said Nicholls. “Why not make an Indigenous rights tribunal that respects and affirms Indigenous rights? We want a domestic framework that’s accessible to Indigenous peoples.”

Although UNDRIP consists of minimum standards endorsed by Canada and 146 other countries, there are concerns that parts of the domestic law differ from the declaration. First Nations leaders worry that without Indigenous input, the principles could be compromised.

British Columbia became Canada’s first jurisdiction to implement UNDRIP in 2019, creating a deputy minister position that works to ensure it’s consistent with provincial laws. While only the Northwest Territories is close to following BC’s lead, Nicholls shared that Quebec Justice Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette told him he is open to adopting it.

Last year, the UN honoured the centennial of Haudenosaunee Deskaheh Levi General’s unsuccessful attempt to speak to its predecessor, the League of Nations. While there are now three UN bodies dealing specifically with Indigenous issues, the struggle continues for high-level participation.

“The majority of comments about Canada’s human rights record were about Indigenous peoples’ rights but Indigenous peoples were not allowed to attend or make submissions,” lamented Nicholls. “The conversation changes when we’re not there.”

Gull-Masty believes Canada has much to gain by creating space for Indigenous voices to supplement positions they share. She said accepting accountability for UNDRIP could allow Canada to influence member states with less-developed Indigenous relations.

“We as Canadians have to be the example and we as First Nations have to guide Canada in being that example,” asserted Gull-Masty. “As a progressive country, Canada could add so much to their position in the international forum.”

Madison Maness, a 12-year-old from Aamjiwnaang First Nation in Sarnia, Ontario, recently had the honour of carrying the Toronto Maple Leafs’ flag before their firstround playoff game against the Boston Bruins.

Her journey from playing in First Nations hockey tournaments to representing her community on a national stage reflects the growing visibility of Indigenous athletes in mainstream sports. Madison’s mother, Stephanie, said her daughter has been playing hockey for as long as she’s been walking. She has played for her Aamjiwnaang team in a tournament in Toronto for several years. During the tournament, she was chosen to be the flag carrier in game 3 of the series.

Stephanie says that after Madison participated in the Little NHL (The Little Native Hockey League) tournament in March, the Leafs contacted tournament organizers for a player to carry the flag during the playoffs.

“They were looking for an Indigenous female hockey player, and they recommended Madison. She was a little hesitant and nervous at first, but I was like, ‘This is an opportunity that we’re not going to pass up,’” said Stephanie.

Upon arrival at the Scotiabank Arena April 24, Madison was feeling the pressure. “My heart was beating really fast when we got there and had the dress rehearsal,” said the sixth grader, who

practiced the flag-waving technique and got equipped with an earpiece that she would listen to for guidance during the big moment.

“After the rehearsal, I was fine and calm,” she said. “I thought I was going to be more nervous, but I was really excited. I never thought I would be able to do this, being a really big fan of the Leafs for years now.”

A member of the Mooretown Lady Flags U13 team, Madison’s friends back home were thrilled to see their team-

mate repping their team on national television before an NHL hockey game.

“My teammates were so supportive, and everyone was texting me good luck,” Madison said.

Her parents were the proudest of all, with her mother noting the positive impact her daughter’s opportunity has had on women’s sports in Aamjiwnaang.

“The whole community has been supportive, and everyone has been bragging about it and cheering her on,” said Stephanie. “She has two younger sis-

ters who look up to her and were excited for her. It’s great for women’s hockey and that’s been awesome to see.”

It was a big moment for the proud mom. “I’m not going to lie, when she was out there doing her thing yesterday, I was definitely crying,” she acknowledged.

Madison’s father, Jamie, said he was a bundle of nerves in the days leading up to the game.

“I couldn’t sleep the night before” he said. “I was more a wreck than she was. But she nailed it and did a good job.”

As for Madison, she hit the ice and skated smoothly while waving the flag proudly. She had a glowing smile when she gave high fives to the players who she and her parents would be watching rinkside moments later.

Madison says that having the earpiece that connected her with her dress rehearsal team off the ice was what allowed her to soak in the once-in-a-lifetime moment. “Skating out was really fun. The ice was so smooth and so big that when I first hit the ice and I had a few nerves but just kept going.”

Indigenous players in the new Professional Women’s Hockey League are also creating buzz in hockey bleachers and dressing rooms across Canada. The PWHL got underway New Year’s Day, and games have been regularly selling out in Ottawa, Toronto and Montreal. The league also has teams in Minnesota, Boston and New York. Two of these players are Victoria Bach and Jocelyne Larocque, who both play for Toronto.

“Honestly, I can’t put it into words how exciting and special this is for us,” Bach said in an interview. “Not only us but future generations. Aside from hockey, like the opportunities that this league is going to create.”

Bach is a member of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, 250 km southwest of Ottawa. Her teammate Larocque is Métis from the small Manitoba town of Ste. Anne, southeast of Winnipeg. Both have played hockey at its highest levels. Larocque won gold with Team Canada at the Sochi Olympics in 2014, and Bach won gold with Canada at the 2021 World Championships. But they’ve never been able to make a career of the sport until the creation of the PWHL.

They have the added responsibility of being ambassadors of the game for young female Indigenous hockey players. As do the other two Indigenous players in the PWHL – Jamie Lee Rattray who plays for Boston and Abby Roque who is with New York.

“The way I see it is representation matters,” Larocque said. “If there is a young Indigenous child out there who dreams of playing professional hockey, they can look to me, to Victoria Bach, to Abby Roque – all of us Indigenous players. We get to eat, sleep, play hockey. It’s everything that we’ve dreamt about, and honestly, it’s surpassed a lot of my expectations. Every day I feel grateful.”

Ministère des Ressources naturelles et des Forêts

THE MINISTÈRE DES RESSOURCES NATURELLES ET

These aerial sprays, which last four to ve weeks, will begin between May 27 and June 4, weather permitting. A total of approximately 1,200 hectares of vulnerable forests will be treated in both public and private forests. The target area is west of Lebel-surQuévillon

The biological insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Btk) will be used in these operations to protect the needles of the affected conifers from damage caused by SBW.

The Société de protection des forêts contre les insectes et maladies (SOPFIM), mandated by the MRNF, is responsible for carrying out these aerial sprays.

It should be noted that the organic insecticide used by the SOPFIM is registered by Health Canada and has been determined to be safe for human health and the environment.

For information about SBW, contact the MRNF by email at nord-du-quebec.foret@mrnf.gouv.qc.ca or by telephone at 819-755-4838. We encourage you to favour email communications.

For information on the insecticide used and aerial spraying operations in the Nord-du-Québec region, contact the SOPFIM at 1-877-224-3381 or visit the website at www.sop m.qc.ca.

Here’s another edition of the Nation’s puzzle page. Try your hand at Sudoku or Str8ts or our Crossword, or better yet, solve all three and send us a photo!* As always, the answers from last issue are here for you to check your work. Happy hunting.

he chirping birds are a signal that spring has finally arrived in the North. The burbling sounds of the rapids have a calming effect as they soften my memories of the latest blizzard, hopefully the last until sometime in July. The rocks of old are showing themselves under the rushing waters of a small river. I wonder how long those rocks have been there... since time immemorial?

I recover from the mesmerizing spring sights and sounds as I remember that the rocks and gravel were only placed there last year. And, as every previous year, they get washed away in the annual spring flooding from the snow melt. Aarrgg!!

I guess it’s time to change tactics on how to get to the hunting spot in the shortest time possible. I turn my little CUV around and head to higher ground only to find the road to the hills is washed out too. So, it’s back to town to wait out the road repair job and do all those other chores I felt I didn’t have time for.

In the meantime, the geese fly by once in a while. It looks like the hunt is good so far, as the first flocks appear on the horizon and are within shooting range. Aaahh, the release of pressures from all the efforts to get out, either by plane, snowmobile (not recommended as the ice isn’t in as tip-top shape as it was in pre-global warming times), boat, ATV, or simply by walking. One by one, the devices die out in the glare of the sun. Earth is taking over.

Nothing like the embarrassment of being rudely awakened by the sound of guns going of

Finally, the prodigal flock arrives, placing everyone on high alert. The silence is deafening, save for the sound of flapping wings and honking geese.

The flock lands and the novice hunters get the first shot. We veterans know the excitement of the first kill and the moment it happens is visible on everyone’s face as memories are relived. The first goose kill for that lucky child, now an adult in his or her own eyes.

I remember mine, killed with a threeshot bolt-action 20 gauge with the choke set on full. Yes, a memory for everyone for generations to come.

As the sun sets, the decoys are put away, only to be set up again the following morning before the sun rises and the beautiful cycle repeats itself. Slowly, life’s daily problems slip away from the tired bones of the elderly and youthful ambitions are regenerated. To get something done that will last in the freezer for the year – or years in our memories – during waking hours.

That means getting up before the sun rises and going to bed after the sun sets. In the spring, there’s not much time between sunset and sunrise, so sleep becomes precious. Some hunters dare to take a chance and snooze during those quiet moments in the afternoon. Nothing like the embarrassment of being rudely awakened by the sound of guns going off.

Back in the day, it was the time for getting stuff done, when nothing was flying close enough to be your supper that evening. The gathering of wood, fetching of water, repairing the dam on the goose pond, all the good things that kept you busy.

Remember that back in the day there was a real world to live in, not a virtual one catered to your passions. Nope, this world comes with sunburnt skin, scuffs and scrapes, sweat and swearing, but always with the reward at the end of the day – that being sleep, blessed sleep.

Good hunting this spring! Signing off from the real world….

Two weeks ago, I landed in Cusco, Peru, which is 11,000 feet above sea level. From the airplane, I could see tiny communities nestled in the most unlikely places at the peaks of mountains, sometimes connected only by small dirt roads. Kind of like a rez way up in the sky.

Cusco was so calm it was hard to believe it had been the stage of violent state repression just months before I got there. It was so quiet that all I could hear were the dogs barking in the neighbourhood.

The uprisings in the Andes of Peru last year were largely driven by social and economic grievances, including opposition to government policies perceived as harmful to Indigenous communities and the environment, such as mining and resource extraction projects. There were also concerns about land rights, cultural preservation, and lack of consultation with Indigenous peoples on development projects.

These issues have long been sources of tension in the region. In fact, social gains in Peru usually come from the mountains densely populated by Indigenous folks, as they’re always the first to take the streets to protest.

However, the tension was still palpable in the bigger cities of the Andes. Police in tactical gear conducting sur

It was so quiet that all I could hear were the dogs barking in the neighbourhood

Indigenous Andean flag hanging outside houses and stores, which is weird for a city where Natives are so visible and colourful in their attire.

The millennium-long presence of the Quechua and Aymara in the mountains is visually striking. The archeological sites with ruins are abundant and every mountain peak bears marks of thousands of years of terrace agriculture.

What made me most emotional was to see contemporary Indigenous people literally living on the structures of their Inca ancestors and using them for their original purposes. Coming from a land too acidic and low in altitude to preserve most man-made things, I was almost envious of their proximity to their heritage.

I can imagine that the mountains feel like a warm hug from their land and that the structures they built their houses on

where in the Americas, Indigenous cultures always made things being mindful of future generations. What are we leaving for generations to come?

I felt right at home. The Andes is probably one of the safest places I’ve visited in my entire life. The Andean craftsmanship was sometimes very similar to our own and their kindness was the same that our communities are known for.

We also struggle with colonial challenges, so my trip was also a reminder of my responsibility to stand in solidarity with my Indigenous kin in other parts of the world. Andeans still fight and risk their lives regularly for their right to sumak kawsay, the “good life”, just like we strive to achieve miyupimâtisîun in Cree country. I will always feel very connected to the people I met there, and I am so proud to exist as an Indigenous person along-

June 2-4, 2024

Westn Otawa

Otawa, ON

Unceded and Unsurrendered Algonquin Anishinaabe Territory