IGNORE VIOLENCE AND YOU’LL SEE THE EFFECTS FOR GENERATIONS. TO STOP THE VIOLENCE, WE MUST FACE IT. AND TALK ABOUT IT.

QUEBEC.CA/INDIGENOUS-RESOURCES-VIOLENCE

Indigenous Partners:

In partnership with:

IGNORE VIOLENCE AND YOU’LL SEE THE EFFECTS FOR GENERATIONS. TO STOP THE VIOLENCE, WE MUST FACE IT. AND TALK ABOUT IT.

QUEBEC.CA/INDIGENOUS-RESOURCES-VIOLENCE

Indigenous Partners:

In partnership with:

Most people would be leery of finding helpful New Yorkers. It is often seen as a place of grumpy insular residents where everyone is out for themselves and at another person’s expense. A recent trip to the Big Apple dispelled this stereotype. No hotel for the three visitors as an old friend I hadn’t seen in over 29 years opened her doors to us to enjoy the city. A friendly move by a long-time resident.

Parking the car for four days in the same spot on the street saw no vandalism or missing vehicle. Nothing like Montreal where some Cree have seen their vehicles stolen from hotel parking lots where you would expect they would be safe from thieves. Plus, there was nary a parking ticket gracing the windshield. An unexpected New York moment.

Traffic in this bustling metropolis was the reason why we left the car parked and used public transit. Being newcomers, we didn’t have any idea of the many sight-seeing options and which subway lines to use. But there were police at most stops as a result of 9/11 (and yes, we visited the memorial for the Twin Towers), so we asked them. With smiles they helped us find our way around the city more than once and gave us advice and ideas to ensure our journeys were trouble-free and enjoyable.

In Montreal, I have told my sons to ask the local or metro police only as a last resort because of their First Nations heritage. Experiencing the difference was definitely a New York moment.

Even while riding the New York subway and talking about where we wanted to go, a New Yorker would speak up

and assist us. Not something you would expect in Montreal even though this city claims to be a tourist-friendly destination.

While visiting museums and local sites we took a taxi or two and never once got taken on an expensive scenic route. The drivers were honest, friendly and talkative… at least the ones we had.

In one bookstore, not finding everything I was looking for, the clerk told me where I might be able to get them – at a competitor’s place. Not something you might experience elsewhere. Just another New York moment.

While taking in the sites we came across the bronze statue of a bull on Wall Street. Two helpful women from London

told us that some helpful New Yorkers said that rubbing the nether regions of the bull was supposed to bring you good luck financially. That’s why the picture of me doing so is shown here. I’ll let you know if it worked depending on how lucky I am. Definitely, a New York moment.

There were certainly more New York moments, but it brings home a fact we should all realize – stereotypes are not always true. We should all try to ensure that New York moments are a part of our lives whether we experience them, or we create them for other people, both strangers and friends.

P.O. Box 151, Chisasibi, QC. J0M 1E0 www.nationnews.ca EDITORIAL: will@nationnews.ca news@nationnews.ca ADS: Danielle Valade: ads@nationnews.ca; Donna Malthouse: donna@beesum.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS: $60 plus taxes, US: $90, Abroad: $110, Payable to beesum communications, all rights reserved, publication mail #40015005, issn #1206-2642 The Nation is a member of: The James Bay Cree Communications Society, Circle Of Aboriginal Controlled Publishers, Magazines Canada Quebec Community Newspaper Assn. Canadian Newspapers Assn. Les Hebdos Sélect Du Québec. Funded [in part] by the Government of Canada. | www.nationnews.ca | facebook.com/NATIONnewsmagazine | Twitter: @creenation_news

Where has all the eelgrass gone? That’s the question scientists and land users are trying to answer, along with its huge impact on geese and other wildlife along coastal Eeyou Istchee.

Land users first noticed the decline of eelgrass and waterfowl in the late 1980s, which rapidly accelerated in the early 2000s. Eelgrass is associated with geese distribution, and it’s believed that as eelgrass quantity and quality declines, so do geese and other waterfowl populations.

In 2014, researchers from Niskamoon Corporation, the four coastal Cree communities, Hydro-Québec and universities across the country initiated the Coastal Habitat Comprehensive Research Program. Their aim was to understand how geese use James Bay, study the abundance of the four geese populations, and how eelgrass beds and other habitats influence geese distribution.

They tracked geese with GPS instruments to determine individual habitats. They sampled more than 100 stations along the coast between 2016 and 2020, looking for chemical elements, dissolved organic matter, and phytoplankton. Researchers were also looking to measure water temperature, salinity, light penetration and water currents.

The team undertook aerial surveys in 2018 to count geese found along coastal traplines and looked at banding of geese

“recoveries” between 1960 to 2020 to determine when and where geese populations have been found.

By 2019, the team began eelgrass surveys at 76 sites in 13 trapline, collecting samples and using satellite imagery. Consultations with trapline users to confirm research results were cancelled because of the pandemic.

In 2020, as outside researchers were unable to enter Eeyou Istchee, an allCree team conducted site visits, including scuba diving to deploy and recover equipment and underwater samples.

The final report from this first phase will be released in April, focusing on causes of the eelgrass and waterfowl decline. The second phase will identify measures that could improve the James Bay ecosystem.

In February, Niskamoon Special Projects Manager Ernie Rabbitskin spoke to the Nation when he attended the Society of Canadian Aquatic Sciences’ meeting in Montreal.

“When the eelgrass started declining, [land users] noticed geese were starting to disappear and shifted migration more inland,” Rabbitskin said. “They weren’t stopping at eelgrass beds because there were almost none; they were flying over. Hunters started being unable to feed their families.”

A high degree of eelgrass decline was reported around the Chisasibi area,

which Rabbitskin thinks may be related to discharges from Hydro-Québec’s La Grande complex, which was completed in the late 1980s. Eelgrass needs saltwater to grow and the increase of freshwater discharge from the project likely changed its habitat. Rabbitskin said that climate change is also a factor.

In total, about 50 researchers, as well as numerous Cree land users, Elders and youth took part in studies that assessed traditional ecological knowledge during visits to hunting camps, interviews and participatory mapping.

Rabbitskin said the project received solid support from communities that first reported the problem.

“They wanted this research to happen,” he emphasized. “It was the land users who were the priority. The communities listened and from there the research started. There wouldn’t be research without that knowledge.”

Rabbitskin began as a field coordinator, working with researchers, land users and tallymen. This involved going out on boats, skidoos and helicopters to inaccessible areas.

Now that the final report is nearly finished, it will be up to communities and leadership to determine the next course of action. “I’m very grateful to everybody, especially the Cree land users,” Rabbitskin added. “We couldn’t have done it without them.”

Kenneth Weistche was five or six when he was removed from Waskaganish and sent to Bishop Horden Hall residential school in Moose Factory. Eventually he was transferred to the Fort George Catholic residential school and later the St. Philip’s School at Fort George.

While the abuses suffered in those experiences were recognized by previous government and church settlements related to residential schools and day schools, Weistche’s later time spent in boarding homes in RouynNoranda, Timmins and Val-d’Or were excluded – until now.

Weistche ended up becoming something of a social worker in recent years, working for wellness programs and helping community members fill out applications for residential school claims and working as a translator for them in Cree.

“I started with just my community. By the time I was done, I knew people from all nine Cree communities,” he said. The federal government hired him to assist with the process and help with translation in about 100 cases. That experience only infuriated him more. “When we went through the process, the federal lawyers and federal government didn’t want to pay everyone,” he shared. “There were ways they could avoid payment to certain people. That got me really mad.”

During this process, Weistche saw government lawyers claim that if children were sexually abused just outside of school grounds, then the federal government wasn’t responsible. “So, who is liable? The children didn’t go there by themselves. The government forced them to go but said they’re not responsible. That got me really angry and that’s why we filed” a class-action lawsuit.

The lawsuit began in 2017 when Weistche approached David Schulze, a Montreal lawyer with the firm Dionne Schulze. “We started talking and recognized some of these things that were happening – how the feds were not responsive to certain cases I just described – lots

For online orders, we accept EMT for payment or we can process credit card or visa debit over the phone.

also accept PO’s from entities and companies. If you need a quote, please send us a message at

of sexual abuse cases, lots of physical abuse cases,” he added.

After filing the suit, Weistche discovered that another group of plaintiffs, led by Reginald Percival, Nisga’a, had already filed a lawsuit. The cases ended up being combined, with Percival listed as the representative plaintiff and Weistche listed as representative plaintiff for the Quebec sub-group.

The federal government operated the Boarding Home Program for Indian Students from the 1950s through the 1980s, where an estimated 40,000 students were placed into boarding homes across Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia.

On January 3, Minister of CrownIndigenous Relations Marc Miller, Percival and Weistche announced an agreement in principle. The lawsuit covers students placed in boarding homes overseen by the federal government between September 1, 1951, to June 30, 1992.

“I was taken from my family and community in 1968 when I was 13 years old. The impact on me, and on other kids like me, was devastating. I have spent decades since then, working to heal, to help others, and to explain to the broader community what happened. It has been a long journey, but I am gratified by the steps we are now taking, as a country, to acknowledge past wrongs and to move forward together,” Percival said in a statement.

“This agreement-in-principle is a milestone for thousands of Indigenous

Peoples who suffered abuse while residing in a boarding home placement overseen by the federal government between 1951 and 1992. Canada will continue to work with the plaintiffs towards a final settlement agreement and approval of the Federal Court in 2023,” Miller stated.

The settlement would include compensation of $10,000 for everyone who attended boarding homes, and between $10,000 and $200,000 for those who suffered sexual or physical abuse. An additional $50 million would go towards healing and commemoration measures.

“I encourage all Cree children to make a claim,” Weistche added, saying that the compensation would also include episodes of racism and verbal abuse. “There was lots of racism in these towns. We faced a lot of physical abuse, lots of sexual abuse. Not only the girls, but it includes the boys… I also had sexual abuse happen to me.

“I went in at five years old. I didn’t understand what was going on. All I knew is I was in a residential school and went to school every day. When you get to 11, 12, 13, 14, you start to understand what’s going on. You start realizing what racism is, you see lots of racism, see lots of physical abuses, because you’re Native in a non-Native town. I got out when I was 18. It was 12 years in the system of Indian Affairs. It was living hell.”

In another incident, Weistche said he saw his own cousin, George Weistche, drown after getting a cramp in Lake Miranda. “He was about 14 or 15 and was sent home in a box, a coffin, by the

federal government. I don’t know if the government ever apologized, but he still has brothers and sisters in the community today.”

Weistche said he learned to blame himself. After he got out, he married and had three children with a woman who was also an alcoholic. He ended up in a treatment centre to stop doing drugs and alcohol.

“It was really good. But halfway through the program, the psychologist who was living there and working with us, pulled me and my wife aside and said you’re doing really well, but there’s a problem: you both are raising your children with the only childhood you know, in residential schools,” Weistche recounted.

“We were raising our own children as if they were in residential school. That really hurt. It still hurts today.”

Now, Weistche hopes that negotiations can wrap up and be implemented by this upcoming fall. “Finally, we can sign the agreement and have healing for everyone. A lot of Cree people are carrying that pain and sorrow.”

After that, claimants will have three years to file for compensation. Weistche then hopes to hire a social worker in Eeyou Istchee.

“There’s still lots of work we have to do for ourselves and our communities. There’s lots of anger. We need healing programs, healing centres where people can go and let go of the pain and anger. Let’s do something, let’s make life good for our children.”

Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay is recruiting workers to provide health and social services to the Cree communities of James Bay.

LIVE AN UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCE BENEFIT FROM ATTRACTIVE PAY BONUSES

FANTASTIC ADVANTAGES AND BENEFITS

TRAVEL AND MEET THE CREE PEOPLE

MANY EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES

MANY LOCATIONS AVAILABLE

Find out about our job offers: creehealth.org/careers/ job-opportunities

The potential defect covers more than 60,000 snowmobiles in Canada, specifically the SKS, RMK, INDY, Rush, Switchback, Titan and Voyageur lines, with different models ranging from 2013 to 2023. Owners can check their model on the Polaris website, and then follow up with their local dealer for repairs. Polaris said owners would be notified by mail.

Chisasibi Chief Daisy House congratulated the organizers, support team, communications team and air medic associated with the First Nations Expedition after the expedition passed through her community February 21-23 and finished their journey on March 4.

“You made it safely to your final destination this evening. It is quite an amazing feat to have traveled over 4,500km in 18 days sometimes in –48-degree weather to bring awareness to three major causes that affect many of our Indigenous Nations,” House said on Facebook.

“It is even more special Mr. Carol Dubé, the late Joyce Echequan’s partner, was able to join and complete the amazing challenge. An angel was definitely watching over him

and his new family throughout this once in a lifetime journey,” she added.

House gave special recognition to the Cree participants in the expedition, including Keith Bearskin, Robbie

Tapiatic and John E. Sam from Chisasibi, Paul-John Murdoch of Wemindji, and Harry Sharl of Ouje-Bougoumou. This was the second year that the organizers held the event, which was focused on advancing the cause of reconciliation and raising awareness of missing children, missing and murdered women and girls, and the tragic case of Joyce Echaquan.

If you need to start your snowmobile, you must make sure the fuel tank is full and, if it is not, then you need to add fresh gasoline to fill the tank.

“An angel was definitely watching over him and his new family throughout this once in a lifetime journey”

Carol Dubé

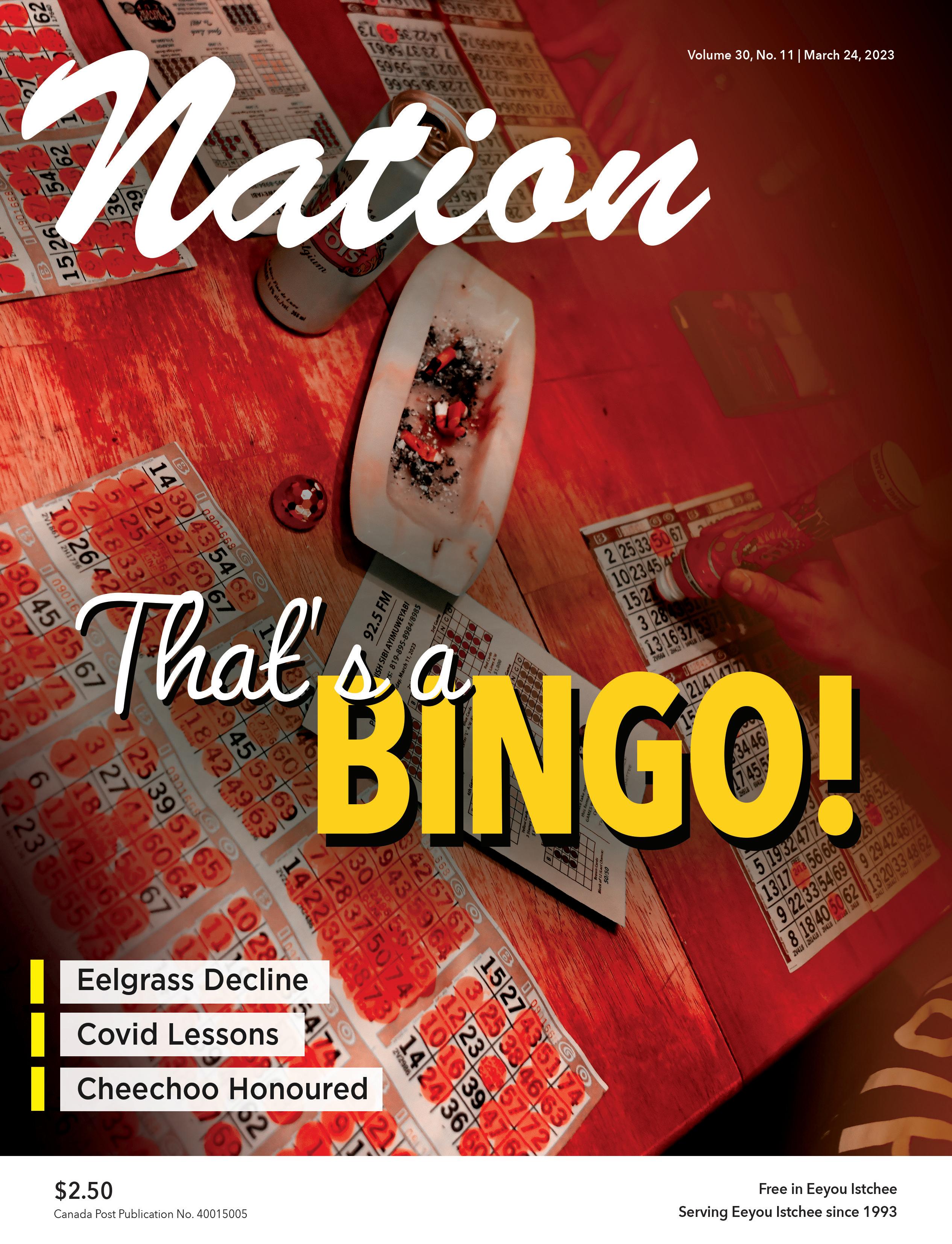

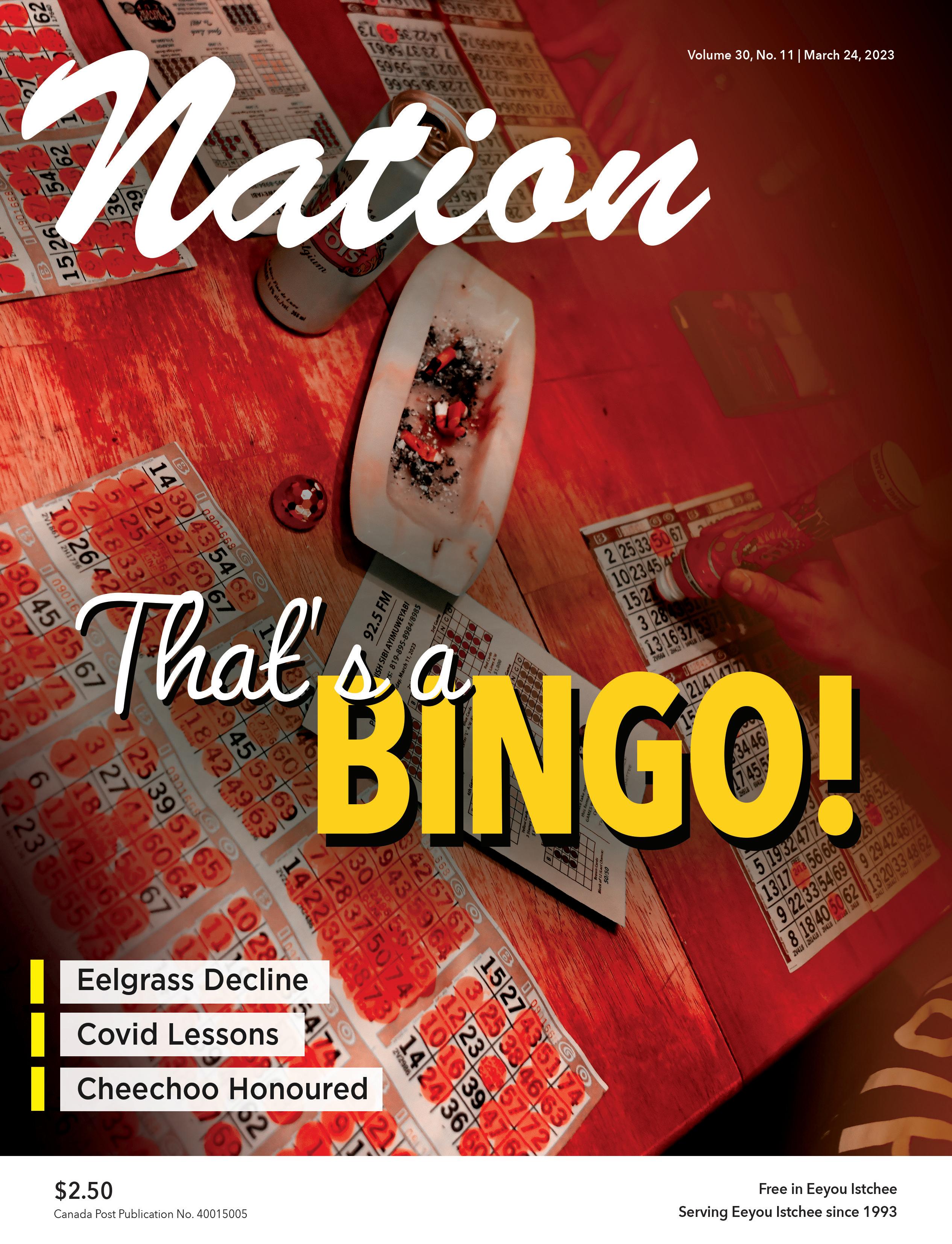

The cultural force of bingo is stronger than ever

Bingo has been a Cree tradition since the 1950s, completing its conquest of Eeyou Istchee only 30-odd years after its invention in the US, where churches and charity groups would play for low stakes.

In some Native communities down south, many of those casinos with gaudy neon lights that are visible for miles around began long ago as humble bingo halls. For instance, the Seminole gambling palaces in Florida started off as tiny bingo trailers. Today, they are one of the wealthiest tribes in the world – they purchased the Hard Rock Café restaurant-bar-slash-museum empire in the early 1990s for $1 billion.

To this day, at many casinos in Oklahoma, hidden away from view usually, will be a tiny hall reserved for bingo. Now, however, they are quiet and almost empty save for a few elderly ladies squinting at their bingo cards.

Bingo in Rupert House started sometime in the 1950s at the now long-gone J.S.C. Watt Memorial Hall at the end of town. Mrs. Maude Watt’s bingo games offered baked goods and merchandise as prizes.

One evening Roderick W. won a pair of bloomers and waved them around to everyone’s laughter. On another game night an elderly man coughed too hard and blew the paper markers off his soon-to-be-winning card. Several young boys tried to help him replace the markers but abandoned him when the game continued.

According to George, who claims to have been an infrequent player, things were not always on the up and up at Mrs. Watt’s games. The same group of women always seemed to be the one who would shout BINGO! He called bingo once and Mrs. Watt checked his

winning card only to declare it invalid. Sure enough, one of Watt’s ladies had the winning card after several more numbers were called.

It’s not that easy to cheat at bingo, as we will see later in our story. Suffice it to say that bingo nights back then were small, fun, communal affairs until radio appeared.

I spent quite a bit of time in Whapmagoostui-Kuujuaraapik several years ago. There was a bingo game almost every single night. It was not a case of bingomania as I believed it to be.

There are two radio stations in town and the Cree and Inuit would take turns broadcasting their games. I would call a friend to chat and after a few seconds I would hear his wife in the background ordering him to stay off the line. I imagine many players had both radio stations on speed dial before the age of cellular phones.

The bingo prizes in Great Whale can be quite grand. One can win several thousand dollars, a speedy snowmobile, an ATV, even a shiny new car!

Bingo can be an expensive affair in an isolated community like Whapmagoostui. The boxes and boxes of cards must be flown in by air cargo after all. Still, on cold winter nights, people bundle up and head to the radio station, cash in hand, dreaming of hitting the jackpot.

Gambling has always been big in the Cree world. So much so that a Creenglish word – jackheejanuu – was coined for at least three games where money was involved, those being the checkers, poker and craps that were constantly played down by the river in Rupert House. It seemed almost every-

one had a deck of cards or a pair of dice in their pockets when we were young.

Then there was the coin toss, which combined skill and chance. A short stick was stuck into the ground and made smooth and flat. The object was to land coins as close to the stick as possible. Whoever’s coin landed the closest would gather the coins. Depending on whether “shaking” or “taking” was called, they would take the ones that landed heads up, or cup the coins, shake them down and take the one he called would land heads or tails up. There was no way to cheat at this game. It was all in the wrist.

Which brings us, finally, to a recent incident at a radio station close to you. There was yet another bingo game one night with a meagre pot of $3,000. A gentleman called the station claiming to have the winning number. The card was verified, and he was awarded the cash.

Not long after, someone noticed the 3 on the number 23 had been not too cleverly altered to read 8. The jig was up.

Angry bingo players took to social media to rant and rave. Some blamed the radio station, others called for the culprit’s head. The police were soon involved. Rumours flew back and forth. Accusations of fraud were heard. Fisticuffs were reported.

In the end, the money was returned unspent, and no charges were laid. But there was to be no happy ending. As of now, all bingo games have been suspended until further notice.

On cold winter nights, people bundle up and head to the radio station, cash in hand, dreaming of hitting the jackpot.

Montreal’s Belgo Building is always a big draw during Nuit Blanche festivities each February, when the city’s cultural centres open their doors all night for mostly free attractions. The Belgo’s art galleries were buzzing about Lido Pimienta’s hourly performances at her exhibition of textiles, drawings and soft sculptures.

Better known for her trailblazing global beats since winning Canada’s prestigious Polaris Prize in 2017, the Colombian-born artist has long maintained a visual-art practice that she disseminates at shows and online. In The Fabric. The Anger. The River., Pimienta honours her Afro-Colombian and Indigenous Wayuu ancestry with

vibrantly coloured, traditional textiles, often adorned with soft-featured faces.

Stepping forward to unleash her powerful voice, flamboyant in a dress of black bows, Pimienta wove together layered artistic threads with full assurance. Embodying the subversive spirit of her 2020 album, Miss Colombia, it was a celebration of feminine beauty on her own terms.

“Decentralizing whiteness is important, decentralizing settler colonialism,” said Pimienta. “I’d like to focus on the real beauty of culture and how absolutely sublime it is to be Caribbean. It’s a big part of my next record – I’m so excited to continue this journey that doesn’t follow a trend.”

While it was easy to idealize Colombia since moving to Ontario in

2005 at age 19, her Grammy-nominated recent album was inspired by soul searching after seeing the racist vitriol following the 2015 Miss Universe pageant, when host Steve Harvey infamously first awarded the crown to Miss Colombia instead of the actual winner, Miss Philippines.

Reflecting on the anti-Blackness she experienced growing up and her country’s obsession with exclusionary beauty standards, Pimiento explored her complicated relationship with her motherland. On alt-cumbia standout “Nada”, featuring Bomba Estereo singer Li Saumet, who joined her at Nuit Blanche and similarly has Canadian children, she confronts intergenerational motherhood trauma and pressures to get married young.

“I live here now but I’m actively working towards my return,” Pimiento told the Nation. “It’s difficult when the territory you belong to is under constant attack and it’s not safe for your kids. At least it’s easier to disconnect from capitalism in Colombia because you can grow your own food all year round.”

During visits to Wayuu desert communities, her children learn valuable life lessons while meeting their cousins who don’t have access to water. Pimiento addresses privilege and colonialism in her surrealistic Lido TV, which debuted last fall on CBC Gem.

“Lido TV is a bejewelled version of myself but still very true to my immediate reality,” said Pimienta. “I’ve learned in Canada to detach yourself, but these issues are a part of me. A lot of people choose to ignore it or blame the immigrant. I think that’s hilarious, and we have to put it on the screen.”

Lido TV funnels her art-school past and penchant for provocation into bizarre skits and conversations with cute sunflower puppets, using humour and self-deprecation to avoid patronizing her audience. In one game show skit skewering Canadian political correctness and hypocrisy, the “best land acknowledgement” winner must give back her luxury cottage to First Nations.

“We’ll know exactly when to draw the line or hold back,” said Pimienta. “It’s frustrating – my family wants to visit, pays for a visa and then gets denied when Canada has 23 active

mines in Colombia. Luckily the people who helped make the show are on that same path and live multiple lives, not just because we are Indigenous or immigrants.”

In an interview with Bear Witness of the Halluci Nation (formerly A Tribe Called Red), who has been a close friend since early in her career, Pimiento suggests that children flourish with a better sense of identity and culture. Forced to grow up quickly after her mother left for Canada when Pimienta was just 14, she said her children are helping her heal from what she missed.

“When you’re a kid you don’t realize you’re not going to be a kid forever, then you yearn for those years,” Pimienta shared. “You’re waiting for the call to be with your mother, but that comes with the reality that now you’re without your motherland. I’m much more appreciative and aware now – you see how present I am in everything that I do.”

Although she’s wary of being labelled an activist and feels anti-colonial rhetoric has been appropriated by capitalism, Pimienta consistently creates art and leverages her platforms to support marginalized communities. During the pandemic, for example, her ‘Portraits for Donations’ initiative raised over $25,000 for vulnerable Colombians.

Whether it’s exploring cultural appropriation at a Barranquilla record store in Lido TV or showcasing an acoustic collaboration in the middle of Miss Colombia with legendary tradition-

al group Sexteto Tabalá of San Basilio de Palenque, the first free African town in the Americas, Pimiento is determined to honour the often-overlooked roots of her musical genre.

For season two of Lido TV, Pimiento hopes to analyze issues like social media addictions and the psychology of self-victimization. Venturing further outside her comfort zone, she’s interested in building bridges with Indigenous communities in northern Canada.

“I want to make comparisons between desert life in the Wayuu community and Arctic living,” said Pimiento. “We are a big family of cousins. I think there are similarities that I want to confirm or see if I’m totally wrong.”

While she started playing in punk and metal bands at age 11, Miss Colombia’s closing track, “Resisto y Ya” (I resist and that’s it), is a subtle form of rebellion probing expectations for brown people to be inherently political. Pimiento continues to break ground, such as becoming the first female of colour to compose an original score for the New York City Ballet Orchestra in 2021.

“Wayuu are a matriarchy, so I don’t know anything different than to be the head of my house,” said Pimienta. “I don’t know what else to do than work. It’s about breaking all those things attached to being someone like me or where I come from and being the paradigm shift. I hope my daughter grows up to be a bad ass like me.”

Two year Contract starting August 2023 and ending June 2025 with options for renewals up to two years. Serving 8 of our communities:

Chisasibi

Wemindji

Eastmain

Waskaganish

Nemaska

Mistissini

Oujé-Bougoumou

Waswanipi

Public Call for Tender is posted on www.seao.ca

Full details and bidding documents are posted on SEAO

Project#: EQ-12-003

Reference#: 1697221

Title: School Transportation Services

Deadline for submissions is March 28, 2023 at 11:00 AM

For more information please contact Christina Jolly:

418-923-2764 ext 1207

christinajolly@cscree.qc.ca

When the first cases of Covid19 were discovered in China in December 2019, it hit the radar of health officials in Eeyou Istchee, who wondered just exactly what kind of threat this new disease represented for the region.

When the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a public health emergency in January 2020, the Cree Health Board (CHB) began to prepare for infection prevention protocols. By the time the WHO declared it a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the CHB was already coordinating response groups to ensure Cree communities were prepared for the advancing pandemic.

This is the story of how that response unfolded. The Nation talked to key leaders within the health board to look back at the past three years and how the CHB, Cree Nation Government, individual Cree communities, entities and individuals all shaped a generally successful pandemic response – and what lessons were learned.

After it became apparent that Covid was spreading around the globe, the CHB determined that its communities were at high risk because of their isolated locations, limited health resources and infrastructure, overcrowded housing, and their high proportions of people with chronic health issues. There was also a need for accurate

information – how the virus was transmitted, how it could be prevented, and how to communicate this to the public.

Bella Petawabano, then-Chairperson of the CHB, remembers clearly the moment the pandemic was declared, followed shortly by Quebec’s declaration of a state of emergency. “I was in Chisasibi, we finished our board meeting and had a presentation on the pandemic by the director of public health,” she recalled.

“I called Grand Chief Abel Bosum, and I asked him what right do the Cree have within the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, and what legal capacity do we have to respond to the pandemic? What can our Cree governance do for us?” she asked.

Petawabano and Bosum did a livestream briefing for the first time to address the population, introducing ideas like social distancing, masking and hand hygiene that would become mainstays for the coming years.

“That’s the only thing we knew about how to protect people at the time,” she said. “There was no manual or protocol to follow in the event of this type of pandemic.”

During this first phase, the CNG, health board, school board, and Cree Nation Council began to meet three times a week and began to issue communiqués. Petawabano also started

doing radio broadcasts. “What was important was a good and continuous communication with the population,” she explained.

It was decided to set up strict travel measures, including community gates and coordination with public safety officers, in addition to contact tracing and testing. “We weren’t following what the province was doing,” Petawabano said. “We were doing more.”

One measure limited the number of patients sent south for medical appointments. All commercial flights were cancelled, and the CHB only used charter flights for patients and to bring in supplies, and eventually vaccines.

While Quebec eased restrictions in May 2020, the Cree communities implemented mandatory self-isolation for anyone travelling to areas at risk. The CNG also adopted a deconfinement plan, looking forward to when restrictions could be loosened as cases declined.

By December 2020, Canada approved the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and ordered deliveries the same month. Petawabano said that months of discussions with Quebec allowed Eeyou Istchee to receive the vaccines ahead of other regions, owing to its heightened vulnerabilities.

It was after November that Petawabano’s term as Chairperson

ended, and Bertie Wapachee took over the role. Looking back at the pandemic response, she said they heard feedback that more cultural values could have been integrated into their response.

“We tried to do that, but things were moving so quickly, you have to move along with the train,” she said. One of the initiatives they were happy to support was pushing people to return to the land, where they would be better protected from transmission. Some communities even offered subsidies to residents who stayed at their camps.

Petawabano is confident the CHB is now more prepared for future health emergencies. “One of the lessons learned is how we all came together: the CNG, the Cree Nation Council, all the different entities like the CHB and Cree School Board,” she said.

“We had one common goal, and that was to protect Eeyou Istchee. That’s one big lesson – that we can unite and be successful in achieving our goal.”

In February 2020, Dr. Colleen Fuller felt she was watching from the sidelines, having just been hired to replace another public health physician. “I called the public health director – I wasn’t supposed to come in for a month – saying I think I need to come earlier. She replied, how early can you come?” Fuller said with a laugh.

Her role involved leading much of the health board’s Covid response. Fuller’s background included using data methods to understand aggregate health outcomes, a focus on infectious diseases and understanding how outbreaks have been controlled.

At the beginning, this meant integrating the quickly evolving science of the virus into everyday practice. “That led to giving and putting into place a certain recommendation one week, then five days later finding new evidence needing to be integrated and adapted,” she explained.

Early recommendations came from the SARS outbreak in 2003, when hospitals enforced masking and isolation. Still, they had to train staff to properly wear masks and conduct contact-tracing investigations.

Community clinics needed infrastructure upgrades to improve ventila-

tion and implement “red” and “green” zones, with Covid cases isolated to avoid infecting those who needed other medical interventions. Telemedicine was introduced, allowing consultations by telephone and video calls.

Still, there were challenges, particularly when it came to government regulations that restricted people without specific qualifications from doing testing. “In Eeyou Istchee, it’s not the local reality that we’d have these types of professionals available. But some people who were able to train and intervene were first responders who don’t necessarily have the same credentials as in the south,” Fuller explained.

They also had to push the Quebec government to adapt their vaccine program to local realities. While the province wanted to allocate vaccines by age group, Cree health officials urged the government to allow broader vaccinations, owing to intergenerational households, and the limited resources and staff available to conduction the program.

Within Eeyou Istchee, Fuller was encouraged by how all levels of officials took the pandemic seriously. “I was very impressed with the willingness of people to come together and listen; to set aside politics – this agency does this or that – but to listen to each other and adapt and revise, to look at needs that might be unanticipated by some agencies.”

She is also confident that Eeyou Istchee is in a better place today to respond as a society – from how to do testing, to how infections spread, to hygiene measures.

Fuller encouraged people to continue getting booster vaccinations, as the virus is still circulating. “The waves aren’t peaking and chopping like they were in the past. Think of it as a river and bay being violently out of control, but it’s now just fast moving. It’s still dangerous, even if not as visible. It’s still not time to go swimming – Covid is still there,” she implored.

Jason Coonishish, Coordinator of Pre-Hospital and Emergency Measures for the CHB, remembered the first days of closely following the WHO’s recommendations, while also studying the

plans put forward by New Zealand, Australia and Quebec.

The priority at the time was to set up protocols to follow and to organize departments to ensure that essential services could continue. This also meant working with public safety officers (PSOs) to carry out enforcement of community-protection measures.

These measures ensured the CHB knew when people left and returned to the communities, and where and with whom they travelled. All this to help conduct contact tracing and enforce isolation measures. “We were in a good position because we were isolated, so we could protect points of entries,” Coonishish explained.

The officers had to resist pressure coming from political leaders to reveal information about infection status. “That’s the hard part the PSOs have –that’s their bosses – but they still maintained that confidentiality,” he added.

He said this built trust being between doctors and the PSOs, and among all frontline workers, including nurses, police and ambulance drivers. Coonishish was proud of the work by all the frontline workers. “Hats off to all of them for their sacrifices to protect our communities.”

Still, there were challenges. Coonishish said the hardest part were measures surrounding funerals, which prohibited open coffins and enforcing social distancing. “It was sad for the family – they didn’t see the body. I’m sure they’re still dealing with grief from that,” he added.

Coonishish praised the vaccine rollout. “Each clinic did very well, they were all ready for it. They had vaccinations. We also did well with the first two boosters,” he said.

One episode that stuck out was that, after vaccines arrived in Mistissini, there was an outbreak in Ouje-Bougoumou. Authorities in Mistissini gave half of their vaccines to Ouje-Bougoumou to ensure Elders and the immunocompromised could be protected.

“I’m happy with the work that was done by all the communities and all the frontlines,” Coonishish emphasized.

May 9 + 10, 2023

Edmonton Convention Centre

Edmonton, AB

Indigenous Youth Empowerment Gathering

Indigenous Youth Empowerment Gathering

May 9 + 10, 2023

May 9 + 10, 2023

Edmonton Convention Centre

Edmonton Convention Centre

Edmonton, AB

Edmonton, AB

Soaring 2023 is back in Edmonton! Taking on a hybrid format for the first time, high school students from across the country will learn about career and post-secondary education options by participating in career workshops either in person or virtually. They’ll also learn more about financial support and meet Canada’s top employers.

Soaring 2023 is back in Edmonton! Taking on a hybrid format for the first time, high school students from across the country will learn about career and post-secondary education options by participating in career workshops either in person or virtually. They’ll also learn more about financial support and meet Canada’s top employers.

Register your group and learn more at indspire.ca/soaring

Soaring 2023 is back in Edmonton! Taking on a hybrid format for the first time, high school students from across the country will learn about career and post-secondary education options by participating in career workshops either in person or virtually. They’ll also learn more about financial support and meet Canada’s top employers.

Register your group and learn more at indspire.ca/soaring

Register your group and learn more at indspire.ca/soaring

Financial Support Available

The Indspire Soaring Travel Fund supports students and their chaperones who wish to attend Soaring and who need additional support. Schools will be able to access funds up to $15,000 to help with the cost of accommodation, transportation, meals, and other expenses your group may need.

The Indspire Soaring Travel Fund supports students and their chaperones who wish to attend Soaring and who need additional support. Schools will be able to access funds up to $15,000 to help with the cost of accommodation, transportation, meals, and other expenses your group may need.

The Indspire Soaring Travel Fund supports students and their chaperones who wish to attend Soaring and who need additional support. Schools will be able to access funds up to $15,000 to help with the cost of accommodation, transportation, meals, and other expenses your group may need.

Through Indspire’s School Grants Fund, schools located in specific communities are eligible to apply for additional grants up to $5,000 to offset travel costs for students and a chaperone to attend Soaring.

Through Indspire’s School Grants Fund, schools located in specific communities are eligible to apply for additional grants up to $5,000 to offset travel costs for students and a chaperone to attend Soaring.

Through Indspire’s School Grants Fund, schools located in specific communities are eligible to apply for additional grants up to $5,000 to offset travel costs for students and a chaperone to attend Soaring.

If you are interested in accessing these funds, please reach out to communications@indspire.ca.

If you are interested in accessing these funds, please reach out to communications@indspire.ca.

If you are interested in accessing these funds, please reach out to communications@indspire.ca.

The pride of Moose Factory, Jonathan Cheechoo, was inducted into the North American Indigenous Athletics Hall of Fame (NAIAHF) in February for his impressive 16-year career in professional hockey, including seven seasons in the NHL. Cheechoo is a member of Moose Cree First Nation in Northern Ontario.

Cheechoo began playing hockey at four years old, joining the AAA Bantam league in Timmins at age 14. From there he was drafted fifth overall by the Ontario Hockey League’s Belleville Bulls in 1997, where he played for three

The San Jose Sharks made Cheechoo the 29th overall pick in the 1998 NHL Entry Draft, leaving him to level up in the OHL before being brought up to the Sharks’ American Hockey League affiliate, the Kentucky Thoroughblades in 2000.

In 2002, he was called up to the Sharks, where he would stay until 2009. During that time, he became a revered player, scoring a franchise record 56 goals and 93 points in the 2005-2006 season. Cheechoo would become the first Shark to win the Maurice “Rocket” Richard Trophy for the most goals in a season and the second Indigenous player in the NHL to score more than 50.

From there, Cheechoo was traded to the Senators for the 2009-2010 season, but moved between AHL teams in the following years, before jumping to the European Kontinental Hockey League in 2013. He retired in 2018, after scoring 305 points in the NHL; 737 as a profes-

“Proud of his roots and Cree heritage, he has maintained strong ties to his home community. Jonathan credits much of his success to the support of

his community and supportive, loving family. Jonathan enjoys leading hockey camps in his hometown and speaks to Indigenous youth about the importance of pursuing their dreams,” the Hall of Fame said in its profile of Cheechoo.

Mervin Cheechoo, Jonathan’s father and the current chief of Moose Cree First Nation, said he learned his son was nominated when he got a call from NAIAHF co-director Dan Ninham asking for a bio and photos.

“We were really excited, hoping he gets in, because I think he deserves it,” Mervin said. Ninham called back later to inform him his son would be inducted. While the NAIAHF originally planned for an event in February for the roughly 80 inductees, they were forced to cancel the planned ceremony because of Covid concerns.

“My wife and I have seen his commitment, dedication and focus from the time Jonathan had the dream at maybe 12 years old to play in the NHL. We’ve seen him make good decisions. We never had a curfew on Jonathan because he was so focused on doing everything he needed to make his goal. We’re so proud of him, and it’s totally well deserved,” Mervin shared.

Mervin said that his son came home from playing hockey one day when he was 12, and dropped his hockey bag on the ground, announcing he wanted to play hockey for the rest of my life.

“I remember standing there, looking at him, trying to find what I wanted to say. I said, there’s probably a million 11-, 12-, 13-year-olds all saying the same thing, but there’s only 700 NHL players,” said Mervin.

“When I asked him who is going to make it, he answered, ‘Whoever works the hardest.’”

In 1992, Jonathan wrote an essay outlining how he wanted to play for the Sharks. By 2002, he had made it to the team. “His dream vision came through,” Mervin recounted.

Mervin said it was initially difficult when Jonathan moved away. Jonathan called and asked to come home, to which Mervin agreed. However, after talking for a while, Jonathan was convinced he could stick it out.

Then after his time in San Jose, the culture shock continued, as Jonathan adapted to living and working in Croatia, Belarus and Slovakia. Mervin said he really enjoyed his time there with his wife and son.

Mervin added that it was important for Indigenous youth to have role models “because of the trauma we experienced as First Nation people. Society has told us we can’t do it because we’re First Nations, we’ve heard those messages for 500 years,” he said.

“But when children see athletes like Jonathan, they are given hope that if Jonathan can do it, they can do it.”

Anew two-day digital happening will be shining a spotlight on the rich and dynamic Cree culture. The Cree Knowledge Festival on March 25-26 will feature six engaging panels, dozens of guests, music performances and storytelling.

Animated by former CBC North radio host Christopher Herodier, the virtual festival intends to connect threads of the past and present to spread awareness about the culture. It’s the first step towards a larger annual event like the Great Northern Arts Festival in the Northwest Territories.

“That festival in Inuvik started really small but is now well known for artists and tourists,” said Robin McGinley, executive director of the Cree Outfitting and Tourism Association (COTA). “We have amazing festivals in the territory but they’re not always the same time. I wanted to have a festival that was always in the same place and date so you could sell packages around it.”

As the travel trade typically establishes prices a year or two in advance, McGinley has long pushed for more

consistency in the region’s tourism offerings. While an in-person event held the third weekend of August in OujeBougoumou might be launched next year, there was an opportunity to host this year’s virtual event before the end of the funding cycle.

With the proposed event coordinator position still vacant, COTA worked with the Cree Trappers’ Association and the Cree Native Arts and Crafts Association to plan this edition, a partnership McGinley called “the three sisters” of the JBNQA. They’re working with Agence Webdiffusion to produce the festival on an interactive platform that’s free to register.

“It’s a mix of art, storytelling, panels, and a mix of old and young,” McGinley explained. “The idea is to share different parts of the Cree reality to create better awareness for a visit when they get a taste of it. It’s designed as a festival – hopefully Crees will be proud too.”

Working with a First Nation for the first time, Webdiffusion has been involved in organizing the schedule and determining which ideas would be the

best fit for a live event. Early indications suggest a huge demand to learn more about the Cree Nation, with 4,000 people already expressing interest in the festival.

“We didn’t know what to expect and so far it’s beyond what we thought was possible,” said Agence Webdiffusion president Claudia Baillargeon. “My colleague is flabbergasted. Our estimate is 2,000 people will want to create an account and watch the festival – it’s going to be like a TV talk show.”

Herodier said he’s been dreaming about hosting this kind of Indigenousfocused television show and is happy to promote the Cree culture however he can. After a long road back from residential school trauma, Herodier is enjoying living back in Chisasibi, actively involved in his community’s communications and media development.

“I’m glad to be home,” Herodier told the Nation. “There’s a lot of positive things going on in Eeyou Istchee. I want to support my leadership – it’s not an easy job and we have to work together

to make positive changes in our community.”

In the first panel aiming to explore the past to reshape the future, Grand Chief Mandy Gull-Masty and Chisasibi Chief Daisy House will attempt to reframe general perceptions about Cree culture. The second panel with the Cree School Board’s Sarah Pash and CREECO president Derrick Neeposh will explore how Cree people are shaping the world through inspiring entrepreneurship.

Through the art of storytelling, writer Janie Pachano and her lifelong partner Roderick will share absorbing anecdotes about Chisasibi gathered over more than 40 years. Elder Eddy Pash will discuss the universal web connecting nature, communities and cultural memory while Dwayne Cox will share teachings about how each Cree was traditionally given a song to embody the unique spirit of what they love.

“As a kid, I heard our Elders speak about who we were,” Herodier shared. “When we were playing hockey aggressively, the late John Napash told us ‘You boys have to take care of each other

because you’re going to help build our community. People are going to want to take your land, but you have to work with them.’ Now I understand what he meant.”

The Cree Knowledge Festival will also zoom in on Cree art through the eyes of a dozen local artists, exploring the inspiration and process behind a diverse range of traditional creations. The final panel will take an in-depth look at Margaret Orr’s flexible approach to artistic media, which often focuses on caribou in her painting, sculpture, leather crafts, film, theatre and storytelling.

“We’ll be talking about what Eeyou Istchee is and the beauty of the Cree culture and language,” said Herodier. “We’ll probably delineate from the original plan and take it to another direction. I’ll try to focus on the artistic talents of the Cree people – it’s going to be something new.”

Singer Mariame Hasni and fiddler Jayden Ratt will feature in performances and live interviews while Cree Rising will offer an exclusive performance to close the gathering. Miss Chisasibi,

Delayna Cox, will also showcase her community’s culture with fancy shawl dancing.

“Since I have been Miss Chisasibi, the whole community has gotten to know me,” said Cox. “Young girls call me princess and want to take a picture with me. I feel welcomed and special at all the events I go to.”

While considering her next move after graduating high school last year, the 17-year-old has kept busy with work, sports and cultural activities like snowshoeing, painting and ice-fishing. Proudly sharing her love of the Cree culture and language, Cox described the transcendental feeling of last summer’s powwow when she participated in a heal dance.

“A sick person comes into the powwow grounds and the ones who have a red jingle dress dance around to heal them,” said Cox. “It’s a very beautiful thing to see. I feel I’m dancing with my ancestors.”

For more info on the Cree Knowledge Festival and to register, visit cree-festival-cri.com

- Elected officials

Chiefs/Grand Chiefs, Vice-Chiefs and board presidents: Next cohort: November 16, 2023

Councillor/Chiefs and board administrators: Next cohort: May 25, 2023

- Entrepreneurs Next cohort: August 30, 2023

- Managers Next cohort: November 29, 2023

- Women and leadership Next cohort: June 12, 2023

*Places are limited

TO FIND-OUT MORE AND SUBMIT YOUR APPLICATION GO TO: FOLLOW US

fnee.ca/programs

Here’s another edition of the Nation’s puzzle page. Try your hand at Sudoku or Str8ts or our Crossword, or better yet, solve all three and send us a photo!* As always, the answers from last issue are here for you to check your work. Happy hunting.

PREVIOUS

Previous

How to beat Str8ts –Like Sudoku, no single number can repeat in any row or column. But... rows and columns are divided by black squares into compartments. These need to be filled in with numbers that complete a ‘straight’. A straight is a set of numbers with no gaps but can be in any order, eg [4,2,3,5]. Clues in black cells remove that number as an option in that row and column, and are not part of any straight. Glance at the solution to see how ‘straights’ are formed.

To complete Sudoku, fill the board by entering numbers 1 to 9 such that each row, column and 3x3 box contains every number uniquely.

For many strategies, hints and tips, visit www.sudokuwiki.org

If you like Str8ts check out our books, iPhone/iPad Apps and much more on our store. The solutions will be published here in the next issue.

Ilooked towards the moon, watching mankind trek around the surface for the first time back in 1969, semi-live and broadcast around the world. We didn’t have television yet in our tiny town of Fort George, so looking as hard as we could, we saw the bright moon clearly in the middle of the day against a jet blue sky. It was windy here on earth and we wondered how bad the weather was on the moon, but we went on with our lives, unaware that the world was living on a precipice and entering a new era of technology.

Back then cutting edge was the small battery-operated portable record player, which came in a variety of plastic hues and made in Japan, the transistor capital of the world. Today, transistors are a nearly extinct type of electronics that are only used in very demanding and tough situations, like in talking plastic baby dolls or any battery-operated toy.

Even as the world hurtles towards what is an increasingly unlimited technocratic society and yet, it is chained to a charging port. Our world has changed so quickly and has overwhelmed our natural senses, and taken our purpose in life away, that is – being alive. Technology may seem endless and infinite, but it needs to be powered by electricity in the end, the basic need for any technological society.

This includes us. We seem to have a heads-up on this as electricity is fairly new and still somewhat cumbersome in

its delivery from the services provider. Power outages are common in the land of never-ending power source, namely the sole provider I should say.

Even though it is recent to the Far North, technology has created a vacuum of knowledge and experience in society. We take it for granted that things, such as lighting, heating and water supply, are gone in an instant when the power goes off. In some cases, information flow is interrupted, and society has a large vacuum in its knowledge base, simply because this information retention, like remembering things and using our brains, has been replaced by technology like TV, internet and blogs. So, what is the use of our brains today?

Back in the day, nothing was taken for granted. Everything had to have some actions to carry out, actions that created some blood, some sweat and some tears. It’s something else that seems to have nearly disappeared and all this work to feed our brains with knowledge has left out the experiential part. So, what happens when the power fails for longer periods, will we remember what to do?

In the Far North, sometimes it takes a few years to recover from natural disas-

ters like fires. One moment you’re enjoying your favourite show streaming via satellite, then complete darkness and cold. Thankfully, we haven’t lost our traditional skills like collecting wood and starting a fire. This is because we haven’t been too dependent on any reliable source of energy long enough to get caught in that trap.

If we like technology and its wonders to take a stronghold in our society, those who supply the power will have to deliver it without interruption for at least five years. If until then, the unlimited supply of energy still has to keep its promise and keep power on long enough to gain control. In that sense, we don’t have much to worry about as power failures are still a common man-made phenomenon.

There’s still firewood as a back-up source of heat and energy. But in the Far North, where the streets still use numbers and letters as names, there are no trees to burn in case of power failures or any sort of emergency. Whether we like it or not, we are now hooked on energy and power and what it provides. Hopefully the powers that power the world keep their promises to their captive customers.

Even as the world hurtles towards what is an increasingly unlimited technocratic society and yet, it is chained to a charging port.Tea & Bannock

Time out

M

My dad speaks fondly of the brotherhood he found playing for the residential school’s team and the Waswanipi Chiefs, and the sense of pride it brought when navigating an oppressive system aimed at shaming every part of his existence.

Hockey has a big place in our communities, and I understand why. The sport was a key component for boys to piece themselves back together as they transitioned from residential school to adulthood.

However, changing-room culture was and still is a fertile ground for trauma through bad coping mechanisms, and I do not think the sport is in its healthiest state in our communities, or anywhere really.

Stories of cover-ups by Hockey Canada of criminal behaviour and testimony from rookie players being sexually assaulted during hazing incidents have made headlines for over a year now.

In Eeyou Istchee, a large amount of money is invested in sponsorships for teams and events like tournaments. Players are put on a pedestal and become the stars of the community. When you sponsor people, I would imagine that

you expect them to perform to their full potential at events that promote good sportsmanship, health and decorum.

So why are we allowing the display of debauchery we see at some of our tournaments? As a player, you are accountable to your sponsors and should be on your best behaviour to compete and to represent your community. You can’t give your best performance if you’re hungover, under the influence and short-tempered.

Collectively, we support hockey teams so much more than other activities that youth partake in. Shouldn’t we have accountability mechanisms in place to prevent disgraceful incidents from happening at tournaments?

I do not mind people drinking or using drugs on their free time, but I do not think sports events are the right place to do that

and especially when that kind of money is involved.

I can understand why it could feel awkward or wrong for organizers to monitor adults when they’re off the ice. While organizers reflect on how to better promote healthy lifestyles in their events, communities should talk to members of their teams about work ethic when they are representing us.

I find it unfortunate that stories of hope and self-esteem told by residential school survivors are not reflected in what we see at hockey tournaments these days. It is sad to see some crazy-talented athletes waste their potential in self-destructive behaviour while we watch and say nothing. We should instill values like dignity and health back into hockey in Eeyou Istchee.